This week, we continue in our survey of the 1950’s, beginning with an Academy Award winner and more ventures into stylistic limited animation. With the exception of Terrytoons, nearly all films this week, even where retaining full animation of star characters, delve into the impressionistic on their backgrund work, making them distinctively recognizable as products of their era. Yet, entertainment levels remain of reasonable to high quality, demonstrating that theatrical animation had not yet entirely caved under budgetary restraints and the increasing competition of television cutting into studio revenues.

Toot, Whistle Plunk and Boom (Disney, 11/10/53 – Charles Nichols/Ward Kimball, dir.) – The sequel to the previous “Adventures in Music” installment, Melody, discussed last week. While likely conceived as a 3-D project like its predecessor, the fad had waned when production began, while a new screen attraction was taking its place – so Disney shifted gears, and adapted the new film to his first use of the widescreen Cinemascope format instead There is the possibility that this conversion took place after work on a 3-D version began, as the film currently exists in two separately-shot editions, in a widescreen and standard screen format, with backgrounds and animation photographed in highly different juxtaposition to one another when comparison is made between the two prints. The standard-screen version is thus not a mere “pan and scan” reprocessing of the widescreen edition, but an entirely different photographic negative. We may therefore be witnessing in the standard edition the completed left or right eye version of one reel our of two of a 3-D cartoon. The film also marked a first, as reputedly the first short distributed under Disney’s own Buena Vista distributing company, though there would continue to be other shorts issued for a time that retained the RKO triangle logo.

Toot, Whistle Plunk and Boom (Disney, 11/10/53 – Charles Nichols/Ward Kimball, dir.) – The sequel to the previous “Adventures in Music” installment, Melody, discussed last week. While likely conceived as a 3-D project like its predecessor, the fad had waned when production began, while a new screen attraction was taking its place – so Disney shifted gears, and adapted the new film to his first use of the widescreen Cinemascope format instead There is the possibility that this conversion took place after work on a 3-D version began, as the film currently exists in two separately-shot editions, in a widescreen and standard screen format, with backgrounds and animation photographed in highly different juxtaposition to one another when comparison is made between the two prints. The standard-screen version is thus not a mere “pan and scan” reprocessing of the widescreen edition, but an entirely different photographic negative. We may therefore be witnessing in the standard edition the completed left or right eye version of one reel our of two of a 3-D cartoon. The film also marked a first, as reputedly the first short distributed under Disney’s own Buena Vista distributing company, though there would continue to be other shorts issued for a time that retained the RKO triangle logo.

Professor Owl is nearly late for class, speedily fastening on his wardrobe and drinking his morning coffee as he hastens to the schoolhouse. All the usual kids from the preceding episode are in attendance, including Bertie Birdbrain, still sitting in the dunce’s corner. Today’s subject, however, is new – the study of musical instruments. These divide into four categories, as the cartoon’s title tune illustrates – the horns (Toot), the woodwinds/reeds (Whistle), the strings (Plunk), and percussion (Boom). Proceeding to a rolling chart, the professor attempts to present the development of these families from the dawn of history. Cranking backwards past figures of various eras, the professor accidentally passes an image of four cavemen, briefly moving backwards to piture of an ape (supporting Darwinism), Apologetically, the professor quickly cranks the chart forward again to the cavemen, and begins from there.

The brass and horns are first demonstrated by a caveman’s blowing into an old cow horn, producing a single squawking note. Cranking the chart forward, ancient Egypt shows the rejection of the caveman’s simple note by a clunk over the head delivered by the pharaoh, and the substitution of a brass horn that sets th hieroglyphics jitterbugging. Action moves ahead to a Roman chariot driver, transporting a mile-long, low note horn supported by a chain of three horse-drawn chariots. The vehicle crashes into a Roman column, and the horn is hopelessly bent – but amazingly preserves its original note and tone. The chariot driver begins wildly experimenting with bending the hord barrel every which way, including designs that resemble a maze, and one that spells out his name, “George”, but continues to get the same musical results. Thus, the curved horn was invented, and various modern day models, including French horns and hunting horns, are depicted. Finally, the professor demonstrates how horns of different lengths can produce only certain notes, but cut off the extra lengths used by the different horns and fasten them all on one instrument by valves, and you can play a complete scale – as in the modern-day trunpet. The professor transitions to the next portion of the lectire in a funny manner, by letting the illustration of a modern trumpeter playing a triple-tongue cadenza roll up to the ceiling like a windowshade, his last note rising to an artificially-speeded high, and a litter pile of random valves and horn buttons falling from the ceiling onto the classroom floor.

The brass and horns are first demonstrated by a caveman’s blowing into an old cow horn, producing a single squawking note. Cranking the chart forward, ancient Egypt shows the rejection of the caveman’s simple note by a clunk over the head delivered by the pharaoh, and the substitution of a brass horn that sets th hieroglyphics jitterbugging. Action moves ahead to a Roman chariot driver, transporting a mile-long, low note horn supported by a chain of three horse-drawn chariots. The vehicle crashes into a Roman column, and the horn is hopelessly bent – but amazingly preserves its original note and tone. The chariot driver begins wildly experimenting with bending the hord barrel every which way, including designs that resemble a maze, and one that spells out his name, “George”, but continues to get the same musical results. Thus, the curved horn was invented, and various modern day models, including French horns and hunting horns, are depicted. Finally, the professor demonstrates how horns of different lengths can produce only certain notes, but cut off the extra lengths used by the different horns and fasten them all on one instrument by valves, and you can play a complete scale – as in the modern-day trunpet. The professor transitions to the next portion of the lectire in a funny manner, by letting the illustration of a modern trumpeter playing a triple-tongue cadenza roll up to the ceiling like a windowshade, his last note rising to an artificially-speeded high, and a litter pile of random valves and horn buttons falling from the ceiling onto the classroom floor.

The reeds are illustrated with the second caveman, serenading his girlfriend with whistles through an actual reed. The girl is largely unimpressed, until the caveman starts drilling multiple holes into the side of the reed, plugging and unplugging the holes with his fingers to get more notes. Now she is entrhalled – but our caveman still doesn’t get the girl, as another caveman just conks her on the head with a club and drags her off to his cave. But music goes on. The caveman still has a problem with so many holes, having to use both his hands and feet to plug them while playing. Without identifying a particular source, the professor states that “some genius” found a way to beat this poblem in a manner neat, with push buttons to activate multiple hole covers while playing, illustrated by the classical clarinet and a bebop saxophone player.

The string originates with the plunking of the bowstring on a bow and arrow by caveman three. From this rapidly develops the attachment of more strings and a resonator, leading to development of harps, and then the guitar family. Using two musicians for illustration, the professor shows us that the instruments can be played either by plucking at the strings, or by use of a bow. Various refinements, including the piano, are illustrated, all with one comedy commonality – every instrument depicted has at least one string break in mid performance, often with comic consequence to the instrument’s owner (such as flipping the powdered wig off a musician playing a classical minuet, revealing his bald head).

The Boom is demonstrated by the fourth caveman, a rotund fellow who can not only beat on objects with his club, but also pound on his own round belly to achieve a bass drum effect. From this develops bells, drums, cymbals, xylophones, oriental and latin rhythm instruments (shown with some politically incorrect imagery), and all other manner of items slapped or hit with sticks or mallets.

The film wraps up with a combination of all the musical families. A Salvation Army band marches by, incongruously followed by a float carrying our four cavemen and their original instruments. A montage of more performances is climaxed by a finale at a concert hall, that again gives every impression of having been animated for 3-D, as the camera tracks in past an audience, through the lobby doors, past an usher, and into the huge hall, where each of the four orchestra families is depicted by musicians that seem to be at differing distaces from the camera, with one of the four cavemen sitting in in center stage. The scene finally returns to the schoolroom, where the 3-D effects continue, as a group of flag waving students rise alongside the conducting professor’s podium, and rows of students four levels deep fill the screen for a final chorus. (That would have looked impressive in 3-D.) The last shot also demonstrates dimensionality, as Bertue Birdbrain strikes a single note on a triangle, and from the vibrations, again seemingly at different levels of depth from the camera, materialize the letters on the words, “The End”. A masterpiece, both on educational and entertainment levels, earning a deserved Oscar. (Attention Disney executives: How much would it cost to reanimate or reprocess this film and “Pigs is Pigs” to complete them in proper 3-D? Don’t you think it might be worth it as an added attraction?)

How Now Boing Boing (UPA/Columbia, 9/9/54 – Robert Cannon, dir., T. Hee/Robert Cannon, story) – A creative and ingenious follow-up to Dr. Seuss’s Gerald Mc Boing Boing, discussed earlier in this series. As previously established in the original, Gerald, a unique child who cannot speak words but communicates entirely in sound effects, is not permitted to attend traditional public school, due to the disruptive effect of his noises upon the class and teacher. Mr. and Mrs, McCloy, now undoubtedly the financial beneficiaries of Gerald’s successful career as a radio star providing all the sound effects for the broadcasts, can now afford to seek private professional assistance to attempt to solve Gerald’s condition and educational problems. Thus, they seek out Professor Joyce, teacher of voice. The door to his office boasts of his abilities: “Lithping cured – also st-st-st-stuttering cu-cu-cu-fixed.” The McCloys introduce themselves and explain Gerald’s problem. Professor Joyce has a reputation of success to uphold, having even been able to accomplish teaching Francis the talking mule how to speak (an unusual direct reference to Universal studio’s successful film franchise, the predecessor to television’s “Mr Ed, the Talking Horse”). In fact, an animated Francis is sitting in his classroom at the moment, giving firsthand demonstration of his speech skills. The Professor states that if he can teach Francis, getting Gerald to speak will be like rolling off a log. (Of course, were this so, we wouldn’t have a cartoon.)

How Now Boing Boing (UPA/Columbia, 9/9/54 – Robert Cannon, dir., T. Hee/Robert Cannon, story) – A creative and ingenious follow-up to Dr. Seuss’s Gerald Mc Boing Boing, discussed earlier in this series. As previously established in the original, Gerald, a unique child who cannot speak words but communicates entirely in sound effects, is not permitted to attend traditional public school, due to the disruptive effect of his noises upon the class and teacher. Mr. and Mrs, McCloy, now undoubtedly the financial beneficiaries of Gerald’s successful career as a radio star providing all the sound effects for the broadcasts, can now afford to seek private professional assistance to attempt to solve Gerald’s condition and educational problems. Thus, they seek out Professor Joyce, teacher of voice. The door to his office boasts of his abilities: “Lithping cured – also st-st-st-stuttering cu-cu-cu-fixed.” The McCloys introduce themselves and explain Gerald’s problem. Professor Joyce has a reputation of success to uphold, having even been able to accomplish teaching Francis the talking mule how to speak (an unusual direct reference to Universal studio’s successful film franchise, the predecessor to television’s “Mr Ed, the Talking Horse”). In fact, an animated Francis is sitting in his classroom at the moment, giving firsthand demonstration of his speech skills. The Professor states that if he can teach Francis, getting Gerald to speak will be like rolling off a log. (Of course, were this so, we wouldn’t have a cartoon.)

The professor first encourages Gerald to join his class in saying, “How now, brown cow”, asking him to let his vocal abilities rise up from deep within him. All he gets for a result is a “Boing Boing” loud enough to cause him to leap into his own wastebasket. He proposes private coaching, and for weeks has Gerald copy the movements of his lips, in mouthing the words “How now, brown cow” without actually sating them aloud. The day arrives when he asks Gerald to add his vocal chords to the drill, but watch his inflection. Gerald again mouths the words perfectly, but the sounds that come out are those of a claxon horn, a crashing clatter of unknown objects, a ship’s bell, and a tinny-sounding gong. The professor’s reputation hangs by a thread. He puzzles and puzzles over what to do, unil an idea comes to him – induce Gerald into loquacity by means of shock. Inviting a trio of illuminaries from the speech therapy world to witness the experiment, the Professor proposes that he shall bring fortb from Gerald the innate instinct to say the word, “Ouch.” Distracting Gerald to look at a sentence written on the blackboard, he asks the boy to seat himself in a chair, but first places on the seat the sharpest of tacks. Gerald sits where indicated, and hops out of the seat, rubbing his rear end in pain. However, he does not say “ouch” – instead, he emit the sounds of a tire puncturing and flopping on the road into a rubbery flat. The Professor is publically humiliated by the speech experts, who pound on his head until he is reduced several feet in height, as the narrator notes that the Professor never felt so small.

The McCloys pack their baggage and wait at a train depot for their return ride home, resigned to the fact that Gerald will never be able to communicate. However, Gerald feels badly that he was responsible for the Professor’s fall from prominence, and decides to do something he has bever done before – cheer up the Professor with a friendly phone call. Back in his private office, Professor Joyce is mixing together the ingredients of an unlabelled bottle with a fresh egg for flavor, into a larger bottle marked for poison with skull and crossbones, and is about to sip the mixture with a straw, when the telephone rings. We do not hear precisely what the professor hears – but it is something different enough from the usual “boings” that the professor is given a vital clue to the cause of Gerald’s condition. Casting aside his poioned “instand breakfast”, the professor races enthusiastically to the train station, catching the McCloys before they can board the train, and dragging the family back into town. The professor is convinced that the reason Gerald can make no human sound is that his larynx is in upside down. He believes he has a solution for this problem, and takes the family inside the central offices of the telephone company. There, he leads them to a room nearly filled by a complicated device designed for scrambling and reassembling signals transmitted in overseas phone calls. He places a round trip call, phoning an international operator in Paris, then asking her to ring their own location in the United States. The call hops the ocean twice, and Gerald picks up his own ringing phone on the other side of the room, answering the call with a “Boing Boing”. The Professor and the McCloys listen on the other end of the line, and all smile. The scene changes to the McCloys bidding the professor goodbye at the train station and heading home, while the speech experts arrive to apologize to the professor, and accept him as “one of us” (the professor’s head fits neatly between their own in a vertical stack, so that now the four experts walk in unison like a totem pole). Why is everyone happy? Because now at the McCloy home, telephones are set up next to each family member’s chair, and another double ocean-hopping call is placed between phones to Gerald’s line. Thanks to the descrambling device, the proud parents are now able to hear the boings of Gerald clearly translated into the words, “How now, brown cow?” (Don’t quit your day job, Gerald. It’s going to take a radio star’s salary to pay for those astronomical phone bills to come.)

By Word of Mouse (Warner (Sylvester), 10/7/54 – Friz Freleng, dir.) – One of three shorts produced in conjunction with the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation as soft-sell lessons in economics – much in the same manner as John Sutherland’s “Inside Cackle Corners” for MGM. The story-within-a-story plot begins with a mock-mittel European mouse named Hans recounting the details of his trip to America to his fellow villagers in the land of Knockwuest-on-Der-Rye. Disembarking from a ship by way of a canopied hawser rope serving as a gangplank, Hans is greeted by an American relative, Willie. After exchange of a Barvarian cheese from home, Hans is struck by the sight of autos and trucks passing on a busy highway. “You oughta see it in the rush hour”, comments Willie, and shows him the sights from a freeway overpass – so amazing, that Hans almost falls off the bridge. “All of dese new automobubbles”, ponders Hans, who, despite learning that some are a “few years old”, is still dumbfounded to find that most are owned by working men. Willie takes Hans to his home – a mousehole entrance to Stacy’s Department Store. They pass through a window display of bikini bathing suits (prompting a wolf whistle from Hans, then ride an elevator past various floors, crowded with endless flows of shoppers. An elevator operator matter-of-factly announces the items available on each floor, including “Clippers, nippers, bedroom slippers, socks, clocks, bagels and lox”. “Vat iss dis?”, inquires Hans. Willie states they are examples of mass production and mass consumption. But when Hans demands a further explanation, Willie is at a complete loss for words. However, he knows a friend who is better suited to provide the answers. Phineas J. Whoopee, perhaps? No, but someone just as competent – a mouse professor of economics as Putnell University (Old P.U.).

By Word of Mouse (Warner (Sylvester), 10/7/54 – Friz Freleng, dir.) – One of three shorts produced in conjunction with the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation as soft-sell lessons in economics – much in the same manner as John Sutherland’s “Inside Cackle Corners” for MGM. The story-within-a-story plot begins with a mock-mittel European mouse named Hans recounting the details of his trip to America to his fellow villagers in the land of Knockwuest-on-Der-Rye. Disembarking from a ship by way of a canopied hawser rope serving as a gangplank, Hans is greeted by an American relative, Willie. After exchange of a Barvarian cheese from home, Hans is struck by the sight of autos and trucks passing on a busy highway. “You oughta see it in the rush hour”, comments Willie, and shows him the sights from a freeway overpass – so amazing, that Hans almost falls off the bridge. “All of dese new automobubbles”, ponders Hans, who, despite learning that some are a “few years old”, is still dumbfounded to find that most are owned by working men. Willie takes Hans to his home – a mousehole entrance to Stacy’s Department Store. They pass through a window display of bikini bathing suits (prompting a wolf whistle from Hans, then ride an elevator past various floors, crowded with endless flows of shoppers. An elevator operator matter-of-factly announces the items available on each floor, including “Clippers, nippers, bedroom slippers, socks, clocks, bagels and lox”. “Vat iss dis?”, inquires Hans. Willie states they are examples of mass production and mass consumption. But when Hans demands a further explanation, Willie is at a complete loss for words. However, he knows a friend who is better suited to provide the answers. Phineas J. Whoopee, perhaps? No, but someone just as competent – a mouse professor of economics as Putnell University (Old P.U.).

The second half of the film is largely a lecture on capitalism and competition to cut prices and costs to sell more goods. It takes a while for ideas to sink in, as Hans sarcastically comments that the first he has been “straightened out – just like a pretzel!” While Hans’ instruction begins in a formal classroom, the venue keeps changing, thanks to the periodic intrusions of Sylvester, in search of a breakfast. Seeing the cat’s face peering down at him over an open textbook, the professor slams the covers of the book shut, flattening Sylvester’s face into a book mark. The lecture moves to a writing desk drawer, inside which the professor provides illumination for the new “classoom” by means of a cigarette lighter. Sylvester pulls open the desk drawer, but bends his head too close to the lighter, igniting one of his whiskers. Sylvester runs into the hall, and dumps an emergency bucket of water over his head (needlessly preceding it by following the formality of a sign reading “In case of fire, break glass”). Now the lecture moves to a filing cabinet, where the mice are easily discovered by Sylvester through alphabetically looking up the file labeled “mice”. A quick mallet blow by the professor dispatches the cat once again, and the lecture is completed on a paper boat inside a water cooler. Sylvester begins swallowing cup after cip of water to get at the mice, who finally pop out the water spout into Sylvester’s cup. “Class dismissed,” says the professor. “We are faced with the problem of mouse consumption!” As the mice scurry out of the building, Sylvester is slow to follow, his belly completely water-logged, so that he sloshes weightily with every step. As Hans and Willie head for the docks, the professor puts Sylvester out of the chase by flipping open a manhole cover in the street, causing Sylvester to crash into it, and fall into the sewer. Our story flashback returns to the present, where Hans asks his villagers if they now understand mass consumption and mass production. A middle-aged female mouse replies, “Understand mass production? I’m a victim of it!”, as the camera reveals a room full of her complaining, whining offspring.

The second half of the film is largely a lecture on capitalism and competition to cut prices and costs to sell more goods. It takes a while for ideas to sink in, as Hans sarcastically comments that the first he has been “straightened out – just like a pretzel!” While Hans’ instruction begins in a formal classroom, the venue keeps changing, thanks to the periodic intrusions of Sylvester, in search of a breakfast. Seeing the cat’s face peering down at him over an open textbook, the professor slams the covers of the book shut, flattening Sylvester’s face into a book mark. The lecture moves to a writing desk drawer, inside which the professor provides illumination for the new “classoom” by means of a cigarette lighter. Sylvester pulls open the desk drawer, but bends his head too close to the lighter, igniting one of his whiskers. Sylvester runs into the hall, and dumps an emergency bucket of water over his head (needlessly preceding it by following the formality of a sign reading “In case of fire, break glass”). Now the lecture moves to a filing cabinet, where the mice are easily discovered by Sylvester through alphabetically looking up the file labeled “mice”. A quick mallet blow by the professor dispatches the cat once again, and the lecture is completed on a paper boat inside a water cooler. Sylvester begins swallowing cup after cip of water to get at the mice, who finally pop out the water spout into Sylvester’s cup. “Class dismissed,” says the professor. “We are faced with the problem of mouse consumption!” As the mice scurry out of the building, Sylvester is slow to follow, his belly completely water-logged, so that he sloshes weightily with every step. As Hans and Willie head for the docks, the professor puts Sylvester out of the chase by flipping open a manhole cover in the street, causing Sylvester to crash into it, and fall into the sewer. Our story flashback returns to the present, where Hans asks his villagers if they now understand mass consumption and mass production. A middle-aged female mouse replies, “Understand mass production? I’m a victim of it!”, as the camera reveals a room full of her complaining, whining offspring.

The First Flying Fish (Terrytoons/Fox, Aesop’s Fables, 2/1/55 – Connie Rasinski, dir) – According to the singing narration of the Satisfiers chorus, there was a time that any fish could choose his own career and destiny, by training to be any species of fish he wanted – from minnow to shark. Of course, this meant going to school. None of the students seem to have any trouble at all in deciding their respective vocations, except for one small fish naed Phillip, who just can’t make up his mind. He doesn’t want to be a shark, as he has no taste for natives. A sardine’s life is not appealing, as he dislikes crowds and tin cans. A goldfish is out, as he doesn’t want to be on the menu for some cat. (A cutaway visualization presents a clever scene, as a cat dunks his head straight into a goldfish bowl, then comes up wearing the bowl like a helmet, and smiles at the camera, displaying the skeleton of the fish inside his mouth instead of pearly white teeth.) So what does Phillip want to be? He tells teacher he’d like to fly and soar above the waves, like a seagull. “A flyig fish?” “There’s no such creature in the sea”, observe his classmates. Phillip is brancded a misfit by the other fish, and chased out of the class up to the surface. “You’re no fisn.” “You’re for the birds.” “G’wan, take the air.” “Go lay an egg”, they taunt. Phillip is left upon a rocky coastline, while his classmates laugh and return to their watery education.

The First Flying Fish (Terrytoons/Fox, Aesop’s Fables, 2/1/55 – Connie Rasinski, dir) – According to the singing narration of the Satisfiers chorus, there was a time that any fish could choose his own career and destiny, by training to be any species of fish he wanted – from minnow to shark. Of course, this meant going to school. None of the students seem to have any trouble at all in deciding their respective vocations, except for one small fish naed Phillip, who just can’t make up his mind. He doesn’t want to be a shark, as he has no taste for natives. A sardine’s life is not appealing, as he dislikes crowds and tin cans. A goldfish is out, as he doesn’t want to be on the menu for some cat. (A cutaway visualization presents a clever scene, as a cat dunks his head straight into a goldfish bowl, then comes up wearing the bowl like a helmet, and smiles at the camera, displaying the skeleton of the fish inside his mouth instead of pearly white teeth.) So what does Phillip want to be? He tells teacher he’d like to fly and soar above the waves, like a seagull. “A flyig fish?” “There’s no such creature in the sea”, observe his classmates. Phillip is brancded a misfit by the other fish, and chased out of the class up to the surface. “You’re no fisn.” “You’re for the birds.” “G’wan, take the air.” “Go lay an egg”, they taunt. Phillip is left upon a rocky coastline, while his classmates laugh and return to their watery education.

But Phillip is determined. He practices and practices to build up flapping strength, taking short hops off the rocks, often failing and falling into the water. He hitches rides by clinging to the tail feathers of passing birds, then tries to soar. One such attempt has him kicked off by the bird’s foot, falling to land stuck in the blowhole of a whale. But eventually. Phillip solos, confusing two passing storks so much that they collide with one another, producing lumps on their heads and angry squawks of complaint. However, Phillip can’t make friends. In a scene directly copied from Disney’s “The Flying Mouse”, Phillip tries to mongle with birds in a tree, who all take leave of him, except for one small fledgling too young to know better, until his mother drags him away. Phillip finds himself rejected by the birds, and ignored by the fish when he attempts to return underwater. Sadly, he vows to give up his dream, and never take to the air again.

Enter our villain – a fishing pelican, complete with fisherman’s hat and net. The chorus begins to quote he old rhyme, “A funny fird is the pelican – his beak can hold more than his belly can”, but the pelican has heard this bit once too often, and stares straight at the camera with a frown of disapproval just as the chorus reaches “His beak can hold more than his…” The chorus stops, clears its throats, and talk sings the word “stomach” instead. The bird nods in approval, and continues on his way. Swooping at the water with his net, the bird begins scooping up entire communities of underwater life, ravenously swallowing the net’s contents following each catch. Phillip’s school is directly in the line of fire. Phillip, returned to class and wearing a dunce cap, is the only one fortunate enough to duck out of range of the net, while the teacher and all of Plillip’s classmates are caught in the trap. As Phillip hears the teacher’s screams, he forgets his vow never to fly again, and rises to apply his unique skills to the task of making a rescue. Animation of the battle sequence is provided by Jim Tyer in his typical off-model, action packed style. Phillip first soars into the pelican, knocking the net from his grasp before he can swallow its contents. The bird is utterly confused as he attempts to follow the actions of the fish with his faze, as Phillip flies circles around his head, leaving the bird’s neck twisted in a spiral. Phillip applies several punches to the bird’s rubbery beak, causing him to fall dazed into the water. But the pelican has friends, and two squadrons of fellow birds dive out of the clouds in single file at opposite 45 degree anfles, their paths converging on Phillip’s location. Phillip rises a few feet in the air, causing the first pelican’s bite to miss. But the lead pelican of the second squadron does not come up empty-billed – accidenally swallowing the leader of squadron 1. Then, he is in turn swallowed by the second pelican of squadron 1, who is swallowed by the second pelican of squadron 2 – and so on, and so on, until the two flocks are all confined within the bill of the last pelican in line. Their combined weight is too much to permit flying, and they all splash down and sink into the sea. Phillip now returns to the original fisher bird, prying open his bill, to allow the swallowed fish to escape from the bird’s stomach. He gives the pelican a swift kick for a sendoff, flipping the bird’s torso into his own bill. The final scenes are some time later, with the grateful fish community having constructed for Phillip a flight school, accrediting him as instructor by presentation of a medal in the shape of a pair of golden wings. The film ends with Phillip leading his first class of new flying fish in formaton flying, as he winks to the camera for the fade out.

Enter our villain – a fishing pelican, complete with fisherman’s hat and net. The chorus begins to quote he old rhyme, “A funny fird is the pelican – his beak can hold more than his belly can”, but the pelican has heard this bit once too often, and stares straight at the camera with a frown of disapproval just as the chorus reaches “His beak can hold more than his…” The chorus stops, clears its throats, and talk sings the word “stomach” instead. The bird nods in approval, and continues on his way. Swooping at the water with his net, the bird begins scooping up entire communities of underwater life, ravenously swallowing the net’s contents following each catch. Phillip’s school is directly in the line of fire. Phillip, returned to class and wearing a dunce cap, is the only one fortunate enough to duck out of range of the net, while the teacher and all of Plillip’s classmates are caught in the trap. As Phillip hears the teacher’s screams, he forgets his vow never to fly again, and rises to apply his unique skills to the task of making a rescue. Animation of the battle sequence is provided by Jim Tyer in his typical off-model, action packed style. Phillip first soars into the pelican, knocking the net from his grasp before he can swallow its contents. The bird is utterly confused as he attempts to follow the actions of the fish with his faze, as Phillip flies circles around his head, leaving the bird’s neck twisted in a spiral. Phillip applies several punches to the bird’s rubbery beak, causing him to fall dazed into the water. But the pelican has friends, and two squadrons of fellow birds dive out of the clouds in single file at opposite 45 degree anfles, their paths converging on Phillip’s location. Phillip rises a few feet in the air, causing the first pelican’s bite to miss. But the lead pelican of the second squadron does not come up empty-billed – accidenally swallowing the leader of squadron 1. Then, he is in turn swallowed by the second pelican of squadron 1, who is swallowed by the second pelican of squadron 2 – and so on, and so on, until the two flocks are all confined within the bill of the last pelican in line. Their combined weight is too much to permit flying, and they all splash down and sink into the sea. Phillip now returns to the original fisher bird, prying open his bill, to allow the swallowed fish to escape from the bird’s stomach. He gives the pelican a swift kick for a sendoff, flipping the bird’s torso into his own bill. The final scenes are some time later, with the grateful fish community having constructed for Phillip a flight school, accrediting him as instructor by presentation of a medal in the shape of a pair of golden wings. The film ends with Phillip leading his first class of new flying fish in formaton flying, as he winks to the camera for the fade out.

The Eggs and Trixie (Art Clokey, Gumby, 8/17/56) – Brief mention of this episode, previously reviewed in my “Happy Henfruit” series some time ago, should be included here. While of school age, Gumby has rarely appeared in an actual classroom, excepting this episode, in which he basically follows in the footsteps of Ralph Phillips, daydreaming during a class on natural history, and envisioning himself in an adventure to save the eggs of a mother triceratops during prehistoric times (giving Clokey his chance to present his own clay take upon “The Lost World”). Gumby’s teacher is not fashioned in the clay mold of Gumby’s mother and father, but is a more realistic human-type figure – probably a model intended for use in the companion “Davey and Goliath” series (which I never personally followed, although doubtless it presented more opportunities for appearances at school). In his dream, Gumby meets a sole child triceratops named Trixie, who longs for the companionship of siblings. Only problem is that Mom is always off foraging for food, and is absolutely careless about minding her eggs, so that they always get destroted by one disaster or another. Gumby attempts to stand guard over the latest nest, but faces every challenge from thieving brontosauruses to animal stampede to erupting volcano. Through perserverance and luck, Gumby manages to save two eggs, and, before anything else can happen, takes them and Trixie to his home in the present, quick hatching the eggs by using a toy stove as an incubator. He awakens to find the teacher calling upon him to identify the dinosaur drawn on the blackboard. “Trixie”, he blurts out, then corrects himself. “I mean, triceratops.”

Pest Pupil (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon (Baby Huey), 1/25/57 – Dave Tendlar, dir) – The time has come at last for giant duckling Huey to attend school. But is any school ready to meet Huey’s “special needs”? Huey gets off on the wrong foot from the moment go. While the other ducklings place apples on the teacher’s desk, Huey declares, “I brought ya a big fat apple”, and plops down a giant pumpkin, smashing the real apples into applesauce on the teacher’s face. He joins two ducklings on the see saw, straddling the center fulcrum to bounce them both off, then whacks the teacher in the face with the crossboard as he dismounts. Huey becomes the first student ever to be expelled from Kindergarten, with a P.S. from the teacher – “He is a dope!” But Mama Duck remains ever hopeful, teling Huey not to worry, as she will hire for him a private tutor.

Pest Pupil (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon (Baby Huey), 1/25/57 – Dave Tendlar, dir) – The time has come at last for giant duckling Huey to attend school. But is any school ready to meet Huey’s “special needs”? Huey gets off on the wrong foot from the moment go. While the other ducklings place apples on the teacher’s desk, Huey declares, “I brought ya a big fat apple”, and plops down a giant pumpkin, smashing the real apples into applesauce on the teacher’s face. He joins two ducklings on the see saw, straddling the center fulcrum to bounce them both off, then whacks the teacher in the face with the crossboard as he dismounts. Huey becomes the first student ever to be expelled from Kindergarten, with a P.S. from the teacher – “He is a dope!” But Mama Duck remains ever hopeful, teling Huey not to worry, as she will hire for him a private tutor.

A Germanic professor duck accepts the new charge, promising that he will make a boy genius out of this raw material. (I wish I could see the bill he is charging to make good on that promise.) The professor announces that arithmetic is the first thing they will tackle. All that registers in Huey’s head is the last word – so he rummages in his toy box and comes up with a football helmet. As the professor reads the numbers off a blackboard, Huey assumes he’s calling a play like a quarterback, assumes the pose of a one-man offensive line, and charges as the last umber is called, yelling “Tackle!” He lands on the professor with such weight, they both crash through a wall, and the professor becomes lodged in the piping of the bathroom sink. Huey extricates hum with a plunger, and asks “Do I get promoted now?” The professor slaps Huey across the face, calling him a “dumkoff”.

Lesson 2 is in music, with a piano piece for beginners entitled “Fireman”. When told to play Fireman on the piano, Huey misinterprets again, leaping atop the instrument, wearing a toy firemam’s helmet, and rolling himself and the professor out the door and into the street. As Huey yells “Clang Clang” and “Toot Toot”, the piano rolls down a hill, and into some construction equipment at the foot of the road, including a lit kerosene lantern. Huey bounces off, but the lantern lands inside the upright piano where the professor is riding, and sets the instrument on fire. Huey now gets to play fireman for real, by uprooting a fire hydrant, ripping the top off, and blasting the piano chamber with water. When the fire dies out, Huey looks for the professor, by opening wooden doors on the piano front, where a player piano roll is spooled. A rush of water spurts out from the holes of the roll, followed by unrolling of the flattened professor between the rollers, while the piano plays “Ach Du Lieber Augustin”.

Third lesson is chemistry. The professor pours two volatile-looking chemicals into respective glass vials. Huey thinks the fizzing mixtures are soda pop. The professor prepares to combine the chemicals, stating,“We will now test it”. Huey, who is having as much trouble grasping reality as Mr. Magoo, again misinterprets the command, responding, “Sure, I’ll taste it.” He swallows both vials simultaneously, and the reaction takes place internally – as he begins to emit fireballs from his throat like cannon fire, each exploding like a firework over and around the professor. The professor runs for his life down the street, while Huey pursues, asking him to mix another soda. One fireball finally hits the proffessor’s rear, and he leaps off a pier into the ocean, briefly floating as his tail cools off. But there is no rest for the professor, as a menacing shark slips up begind him. The panicked professor dog paddles, screaming for someone to help. No one around but Huey, so Huey helps in his own unique way. Grabbing an anchor off the pier, he throws it with superhuman strength at the shark, just as the professor is being swallowed. The anchor goes down too, and Huey tugs at the rope to which the anchor is tied. The shark resists stibbornly, with his tail wrapped around a pier piling, but Huey’s mighty pull not only retrieves the anchor, but the entire internal skeleyon of the shark, which is brought up on the pier. The skeletal jaws open, and there is the professor, still in one piece. “Now do I get promoted?”, Huey asks again. Actually, yes. The final shot is back in the Duck’s living room, where Huey stands in a cap and gown (the gown ill fitting, so it ids held together in the front with the safety pin of Heut’s diaper. “For being smart enough to save my life, I give to you this diploma”, announces the professor. “I’m so pround”, boasts a tearful Mama. But she and the professor may have second thoughts, as they react in amazement to what Huey is doing. He is tearing vigorously at the corners of the diploma, then unfolds it – to reveal a set of paper dolls in his own image. “Hey ma”, asks Huey, “Where do we hang my diploma?”

Third lesson is chemistry. The professor pours two volatile-looking chemicals into respective glass vials. Huey thinks the fizzing mixtures are soda pop. The professor prepares to combine the chemicals, stating,“We will now test it”. Huey, who is having as much trouble grasping reality as Mr. Magoo, again misinterprets the command, responding, “Sure, I’ll taste it.” He swallows both vials simultaneously, and the reaction takes place internally – as he begins to emit fireballs from his throat like cannon fire, each exploding like a firework over and around the professor. The professor runs for his life down the street, while Huey pursues, asking him to mix another soda. One fireball finally hits the proffessor’s rear, and he leaps off a pier into the ocean, briefly floating as his tail cools off. But there is no rest for the professor, as a menacing shark slips up begind him. The panicked professor dog paddles, screaming for someone to help. No one around but Huey, so Huey helps in his own unique way. Grabbing an anchor off the pier, he throws it with superhuman strength at the shark, just as the professor is being swallowed. The anchor goes down too, and Huey tugs at the rope to which the anchor is tied. The shark resists stibbornly, with his tail wrapped around a pier piling, but Huey’s mighty pull not only retrieves the anchor, but the entire internal skeleyon of the shark, which is brought up on the pier. The skeletal jaws open, and there is the professor, still in one piece. “Now do I get promoted?”, Huey asks again. Actually, yes. The final shot is back in the Duck’s living room, where Huey stands in a cap and gown (the gown ill fitting, so it ids held together in the front with the safety pin of Heut’s diaper. “For being smart enough to save my life, I give to you this diploma”, announces the professor. “I’m so pround”, boasts a tearful Mama. But she and the professor may have second thoughts, as they react in amazement to what Huey is doing. He is tearing vigorously at the corners of the diploma, then unfolds it – to reveal a set of paper dolls in his own image. “Hey ma”, asks Huey, “Where do we hang my diploma?”

Fishing Tackler (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon (Little Audrey), 3/29/57 – I. Sparber, dir.) – A simple plot we’ve seen twice before, told in poky pacing. Audrey and her dog Pal begin the day at a fishing hole, where Audrey comments this is more fun than going to school. A truant officer skulks in the bushes. Audrey flips her pole back to make a cast, and catches the officer by the trousers on her hook. Audrey and Pal run for it, as the officer picks up the pole, casts, and hooks Aufrey by the skirt. A tug of war ensues, as Pal grabs onto the line with his teeth and resists the officer’s reeling in, while Audrey frees herself from the hook and ties off the line to the handle of a lawn mower. On her signal, Pal lets go the line, and the officer is mowed dowm losing the backside of his suit. Sequence two finds Audrey at another fishing site, her back to a fence of wooden slats. Ome slat is loose at the bottom, and the officer pivots it from the top to scoop up Audrey and depisit her in a sack. Pal retaliates by pivoting the board again, using the top of the slat to bop the officer on the head. Audrey runs, still covered by the sack, into a doghouse. The officer reaches inside and grabs the sack, seemingly still full. But Audrey has made a switch, and the bag is now full of mean bulldog, who chases the officer off.

Fishing Tackler (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon (Little Audrey), 3/29/57 – I. Sparber, dir.) – A simple plot we’ve seen twice before, told in poky pacing. Audrey and her dog Pal begin the day at a fishing hole, where Audrey comments this is more fun than going to school. A truant officer skulks in the bushes. Audrey flips her pole back to make a cast, and catches the officer by the trousers on her hook. Audrey and Pal run for it, as the officer picks up the pole, casts, and hooks Aufrey by the skirt. A tug of war ensues, as Pal grabs onto the line with his teeth and resists the officer’s reeling in, while Audrey frees herself from the hook and ties off the line to the handle of a lawn mower. On her signal, Pal lets go the line, and the officer is mowed dowm losing the backside of his suit. Sequence two finds Audrey at another fishing site, her back to a fence of wooden slats. Ome slat is loose at the bottom, and the officer pivots it from the top to scoop up Audrey and depisit her in a sack. Pal retaliates by pivoting the board again, using the top of the slat to bop the officer on the head. Audrey runs, still covered by the sack, into a doghouse. The officer reaches inside and grabs the sack, seemingly still full. But Audrey has made a switch, and the bag is now full of mean bulldog, who chases the officer off.

To keep the officer from sneaking up on them again, Audrey shifts her fishing to a rowboat on the lake. But the determined officer swims up to the boat from underwater, and climbs in at the bow, manning the oars to row the craft away to school. As Audrey, in the stern, spies him, she pulls some surprisingly fast carpentry work. The officer suddenly finds himself rowing half a craft, consiting only of the sides and seat of the boat with no stern or bottom, and sinks into the lake, while Audrey and Pal, riding the floating half, tow themselves back to shore by hooking Audrey’s line to a tree on the bank and reeling in. More chasing takes place into a long pipe at a construction yard. The officer picks up the pipe and rotates it end down to shake Audrey out, but she is already standing on the top end, using the elevation to climb hand over hind on wires from a telephone pole. The officer is quickly up the pole, making a grab for her. She dives onto a storefront awning, and while she bounces off safely, the officer gets caught in the canvas, and Audrey winds the awning shut to trap him. The canvas rips from his weight, and the officer plops onto the pavement, seemingly unconscious. Pal and Audrey head back to investigate, concerned that they might have really hurt him. But the officer is playing possum, and finally makes his capture. He marches Audrey back to the school under her protest, then sees the inevitable – a sign on the door, indicating closure for a holiday. Rather than shrinking away as Donald Duck did in “Truant Officer Donald”, the officer spends the rest of the day making amends, in a diving helmet at the bottom of the lake, where he grabs any passing fish and hooks it onto Audrey’s line, giving her the record catch of any child’s dreams. Pleasant, but highly derivative entertainment.

To keep the officer from sneaking up on them again, Audrey shifts her fishing to a rowboat on the lake. But the determined officer swims up to the boat from underwater, and climbs in at the bow, manning the oars to row the craft away to school. As Audrey, in the stern, spies him, she pulls some surprisingly fast carpentry work. The officer suddenly finds himself rowing half a craft, consiting only of the sides and seat of the boat with no stern or bottom, and sinks into the lake, while Audrey and Pal, riding the floating half, tow themselves back to shore by hooking Audrey’s line to a tree on the bank and reeling in. More chasing takes place into a long pipe at a construction yard. The officer picks up the pipe and rotates it end down to shake Audrey out, but she is already standing on the top end, using the elevation to climb hand over hind on wires from a telephone pole. The officer is quickly up the pole, making a grab for her. She dives onto a storefront awning, and while she bounces off safely, the officer gets caught in the canvas, and Audrey winds the awning shut to trap him. The canvas rips from his weight, and the officer plops onto the pavement, seemingly unconscious. Pal and Audrey head back to investigate, concerned that they might have really hurt him. But the officer is playing possum, and finally makes his capture. He marches Audrey back to the school under her protest, then sees the inevitable – a sign on the door, indicating closure for a holiday. Rather than shrinking away as Donald Duck did in “Truant Officer Donald”, the officer spends the rest of the day making amends, in a diving helmet at the bottom of the lake, where he grabs any passing fish and hooks it onto Audrey’s line, giving her the record catch of any child’s dreams. Pleasant, but highly derivative entertainment.

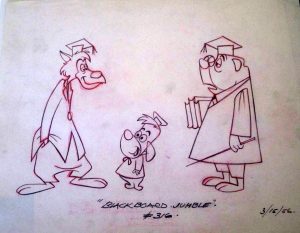

Blackboard Jumble (MGM, Droopy, 10/4/57 – Michael Lah, dir.) – It is uncertain (perhaps merely unknown to me) what the exact conditions were of any training or interconnection between the paths of Tex Avery and Michael Lah at MGM during Avery’s tenure. Certainly Lah would have been well aware of Avery’s output and style, while he himself was working on projects for the same studio, most notably on the Barney Bear series, several installments of which show definite sharpening of timing in the Avery fashion. What is uncertain is whether Lah ever worked directly with Avery or studied in his style under his tutelage. At least a few cartoons (notably, “Deputy Droopy” and “Cellbound”) display a joint director credit between Avery and Lah – but it is unclear if this is merely recognition of Lah finishing up an uncompleted Avery project after his departure, or if Avery actually took Lah under his wing to teach him the ropes before leaving the ship. Whatever the circumstances, it quickly became evident that Lah was the fast learner and understudy in the wings to pick up the reins on the Avery properties – particularly of the still profitable Droopy series, which would need a new captain at the helm. Only one prior Droopy had ever been directed by anyone other than Avery (“Caballero Droopy”, directed by Dick Lundy), and not only were Lundy’s services no longer available at the time of Avery’s exit, but his effort seemed rather weak, such that Lundy was not the man for the job. Thus, Lah had a clear field for succession to the throne, and his efforts were no doubt appreciated by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, who had risen to the level of producers, while still themselves burdened with the task of keeping up the Tom and Jerry quota. Having never touched the Droopy character themselves, Bill and Joe were probably happy to receive all the help they could get from Lah to allow MGM’s second series of shorts to continue.

Blackboard Jumble (MGM, Droopy, 10/4/57 – Michael Lah, dir.) – It is uncertain (perhaps merely unknown to me) what the exact conditions were of any training or interconnection between the paths of Tex Avery and Michael Lah at MGM during Avery’s tenure. Certainly Lah would have been well aware of Avery’s output and style, while he himself was working on projects for the same studio, most notably on the Barney Bear series, several installments of which show definite sharpening of timing in the Avery fashion. What is uncertain is whether Lah ever worked directly with Avery or studied in his style under his tutelage. At least a few cartoons (notably, “Deputy Droopy” and “Cellbound”) display a joint director credit between Avery and Lah – but it is unclear if this is merely recognition of Lah finishing up an uncompleted Avery project after his departure, or if Avery actually took Lah under his wing to teach him the ropes before leaving the ship. Whatever the circumstances, it quickly became evident that Lah was the fast learner and understudy in the wings to pick up the reins on the Avery properties – particularly of the still profitable Droopy series, which would need a new captain at the helm. Only one prior Droopy had ever been directed by anyone other than Avery (“Caballero Droopy”, directed by Dick Lundy), and not only were Lundy’s services no longer available at the time of Avery’s exit, but his effort seemed rather weak, such that Lundy was not the man for the job. Thus, Lah had a clear field for succession to the throne, and his efforts were no doubt appreciated by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, who had risen to the level of producers, while still themselves burdened with the task of keeping up the Tom and Jerry quota. Having never touched the Droopy character themselves, Bill and Joe were probably happy to receive all the help they could get from Lah to allow MGM’s second series of shorts to continue.

The film’s title plays upon the success of the movie version of “Blackboard Jungle”, mentioned last week, though taking a more comic approach to the subject of out of control children than did Mighty Mouse. Lah reaches back to revive a character Avery used twice – an unnamed wolf (Weren’t most of Avery’s wolves never Christened?) with a definite Southern-fried accent and laid-back demeanor, relying upon the strong voice work of Daws Butler. Daws would carry this memorable voice to other studios as well, duplicating it for Smedly the St. Bernard in the Chilly Willy series for Walter Lantz, and for Huckleberry Hound when Hanna and Barbera later moved into television. The wolf first appeared as a dog catcher in Three Little Pups (1953), then reappeared with slight modification in Billy Boy (1954). It is the model from “Three Little Pups” that Lah centers upon – actually retracing a handful of shots from the production for reuse in this film in widescreen Cinemascope. No longer a public dog catcher, the wolf is nevertheless still civic-minded when he encounters a professor having a major nervous breakdown, making an escape from the school that is driving him crazy while simultaneously suffering from fits. The wolf asks the professor what’s the matter. “Modern education’s what’s the matter. Those kids are driving me crazy. Anybody that wants this teaching job would have to be an idiot.” The professor pauses, getting a good look at who he is talking to, and dawn breaks that this scraggly wolf perfectly meets the job requirement he has just described. The professor abruptly thrists his textbooks and pointer into the wolf’s hands, slaps his mortarboard upon the wolf’s head, and disappears screaming over the hill. The wolf observes that “Nobody has no patience no more”, and tells is that “There ain’t nothin” wrong with modern education”, nor with the kids. However, a camera view through the window of the schoolhouse shows us a trio of identical Droopy dogs, based on the model sheet of “Three Little Pups”, having a battle royal inside the classroom. The wolf enters the room in his usual slow-mannered walk, enduring ia well-timed onslaught of flying books, rubber darts, paper airplanes, lunches, and various bric-a-brac before reaching the teacher’s desk. “Cease fire, men”, the wolf calmly states. The dogs pause, not knowing what to make of the stranger. But when the wolf announces he will be their new teacher, the dogs smile among themselves, realizing he’s fair game.

The film’s title plays upon the success of the movie version of “Blackboard Jungle”, mentioned last week, though taking a more comic approach to the subject of out of control children than did Mighty Mouse. Lah reaches back to revive a character Avery used twice – an unnamed wolf (Weren’t most of Avery’s wolves never Christened?) with a definite Southern-fried accent and laid-back demeanor, relying upon the strong voice work of Daws Butler. Daws would carry this memorable voice to other studios as well, duplicating it for Smedly the St. Bernard in the Chilly Willy series for Walter Lantz, and for Huckleberry Hound when Hanna and Barbera later moved into television. The wolf first appeared as a dog catcher in Three Little Pups (1953), then reappeared with slight modification in Billy Boy (1954). It is the model from “Three Little Pups” that Lah centers upon – actually retracing a handful of shots from the production for reuse in this film in widescreen Cinemascope. No longer a public dog catcher, the wolf is nevertheless still civic-minded when he encounters a professor having a major nervous breakdown, making an escape from the school that is driving him crazy while simultaneously suffering from fits. The wolf asks the professor what’s the matter. “Modern education’s what’s the matter. Those kids are driving me crazy. Anybody that wants this teaching job would have to be an idiot.” The professor pauses, getting a good look at who he is talking to, and dawn breaks that this scraggly wolf perfectly meets the job requirement he has just described. The professor abruptly thrists his textbooks and pointer into the wolf’s hands, slaps his mortarboard upon the wolf’s head, and disappears screaming over the hill. The wolf observes that “Nobody has no patience no more”, and tells is that “There ain’t nothin” wrong with modern education”, nor with the kids. However, a camera view through the window of the schoolhouse shows us a trio of identical Droopy dogs, based on the model sheet of “Three Little Pups”, having a battle royal inside the classroom. The wolf enters the room in his usual slow-mannered walk, enduring ia well-timed onslaught of flying books, rubber darts, paper airplanes, lunches, and various bric-a-brac before reaching the teacher’s desk. “Cease fire, men”, the wolf calmly states. The dogs pause, not knowing what to make of the stranger. But when the wolf announces he will be their new teacher, the dogs smile among themselves, realizing he’s fair game.

“First thing we’re gonna learn around here is some manners”, declares the wolf. The kids respond by offering him a chair to sit on. The wolf is touched by this act of kindness, untul he spots a rope tied to the chair, by which the dogs untend to pull the seat out from under him. “Outthink ‘em”, Save ‘em from themselves”, says the wolf, grabbing the chair with both hands, and slowly lowering himself to settle down. Who’s outthinking who, as the dogs change tactics altogether, and place a firecracker upon the seat before the wolf can sit down. The blast repositions the wolf’s hips well above his elbows. Next, the wolf examines the recommended curriculum. He tosses away textbooks on reading, writing, and “‘rithmetic”, then finds one to his liking. “Finger paintin’, man!” The happy pups wheel out a blank canvas, and the wolf hands them cans of red and blue paint. “Now paint me somethin’ patriotic, like, uh….the Confederate flag!” The pups produce a perfect replica, minus one detail. “Uh oh. You forgot the stars”, observes the wolf. The pups provide an easy solution, hitting the wolf over the head with a club, which produces just enough stars from his head to complete the image. “There’s a cotton pickin’ Yankee in this crowd”, the wolf declares. The kids move on to a “Natural Aptitude Table”, basically one of those “place the square peg in the square hole” affairs. The wolf approves. “Let ‘em do what comes natural.” Suddenly, he feels a tug on his leg, as one pup drives his foot into a pre-shaped hole with a hammer. The other pips join in, and the wolf slowly disappears from view, until the camera shifts to show him tied in knots through the holes of the table. “Yoi can’t get more natural than that, man”, he comments dryly.

“First thing we’re gonna learn around here is some manners”, declares the wolf. The kids respond by offering him a chair to sit on. The wolf is touched by this act of kindness, untul he spots a rope tied to the chair, by which the dogs untend to pull the seat out from under him. “Outthink ‘em”, Save ‘em from themselves”, says the wolf, grabbing the chair with both hands, and slowly lowering himself to settle down. Who’s outthinking who, as the dogs change tactics altogether, and place a firecracker upon the seat before the wolf can sit down. The blast repositions the wolf’s hips well above his elbows. Next, the wolf examines the recommended curriculum. He tosses away textbooks on reading, writing, and “‘rithmetic”, then finds one to his liking. “Finger paintin’, man!” The happy pups wheel out a blank canvas, and the wolf hands them cans of red and blue paint. “Now paint me somethin’ patriotic, like, uh….the Confederate flag!” The pups produce a perfect replica, minus one detail. “Uh oh. You forgot the stars”, observes the wolf. The pups provide an easy solution, hitting the wolf over the head with a club, which produces just enough stars from his head to complete the image. “There’s a cotton pickin’ Yankee in this crowd”, the wolf declares. The kids move on to a “Natural Aptitude Table”, basically one of those “place the square peg in the square hole” affairs. The wolf approves. “Let ‘em do what comes natural.” Suddenly, he feels a tug on his leg, as one pup drives his foot into a pre-shaped hole with a hammer. The other pips join in, and the wolf slowly disappears from view, until the camera shifts to show him tied in knots through the holes of the table. “Yoi can’t get more natural than that, man”, he comments dryly.

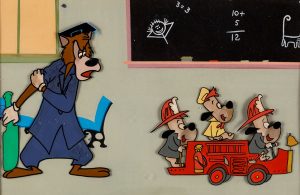

Somehow freed from the table, the wold returns to his desk, only to find his seat replaced by a bear trap. He calmly walks over to a wall rack of convenient paddle boards. “If modern education don’t work, you gotta apply a little ol’ fashioned education.” He picks up one of the pups and prepares to perform a paddling. But another pup beats him to the punch, lighting a match between the wolf’s toes for a quick hotfoot. As the wolf leaps about in pain, the two free pups roll in on a toy fire engine. Instead of extinguishing the blaze, they raise an extension ladder to the wolf’s arm, and rescue their captive comrade, leaving the wolf on fire. The three pups retreat to a utility closet, and lock themselves in. The remainder of the film closely parallels the setup from “Three Little Pups”, with the wolf attempting to get the pups out or himself in. One new gag has him roll in a huge cannon from a human cannonball act, and prepare to launch himself into the closet. One pup opens the door and reaches out to re-aim the cannon straight up, blasting the wolf through the ceiling, and headfirst into the school bell in the building’s tower. After repeated failures, the blasted, blackened wolf addresses the audience. “Y’know, bein’ a schoolteacher takes patience. :Lots and lots of patience. And lemme tell ya’ somethin’ right now…” The scene cuts to the same exterior shot where we met the previous professor, now with the wolf exiting the schoolhouse screaming and in fits, pausing only long enough to complete his sentence: “…Man, I ain’t got any more!”

Somehow freed from the table, the wold returns to his desk, only to find his seat replaced by a bear trap. He calmly walks over to a wall rack of convenient paddle boards. “If modern education don’t work, you gotta apply a little ol’ fashioned education.” He picks up one of the pups and prepares to perform a paddling. But another pup beats him to the punch, lighting a match between the wolf’s toes for a quick hotfoot. As the wolf leaps about in pain, the two free pups roll in on a toy fire engine. Instead of extinguishing the blaze, they raise an extension ladder to the wolf’s arm, and rescue their captive comrade, leaving the wolf on fire. The three pups retreat to a utility closet, and lock themselves in. The remainder of the film closely parallels the setup from “Three Little Pups”, with the wolf attempting to get the pups out or himself in. One new gag has him roll in a huge cannon from a human cannonball act, and prepare to launch himself into the closet. One pup opens the door and reaches out to re-aim the cannon straight up, blasting the wolf through the ceiling, and headfirst into the school bell in the building’s tower. After repeated failures, the blasted, blackened wolf addresses the audience. “Y’know, bein’ a schoolteacher takes patience. :Lots and lots of patience. And lemme tell ya’ somethin’ right now…” The scene cuts to the same exterior shot where we met the previous professor, now with the wolf exiting the schoolhouse screaming and in fits, pausing only long enough to complete his sentence: “…Man, I ain’t got any more!”

umping ahead slightly in chronology to allow for discussion together of Audtrey’s last outings (we’ll backpedal a bit next week), we close with Dawg Gawn (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon (Little Audrey) 12/12/58) – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Audrey returns for her final theatrical appearance, with a bit more action than the previous effort above. However, the action is becoming more impinged upon by the studio’s budgetary constraints, resulting in a short-lived transitional style that, while still continuing to draw the characters well posed and on model, sacrifices smoothness of movement by the removal of a good deal of inbetweening, making motion look hesitant and stilted in many cycles and sequences. At least it wasn’t the Irv Spector influenced style that was to follow – it might be difficult to imagine how Audrey would have appeared in a flat UPA style, possibly explaining why this would be the last episode Paramount could afford.

umping ahead slightly in chronology to allow for discussion together of Audtrey’s last outings (we’ll backpedal a bit next week), we close with Dawg Gawn (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon (Little Audrey) 12/12/58) – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Audrey returns for her final theatrical appearance, with a bit more action than the previous effort above. However, the action is becoming more impinged upon by the studio’s budgetary constraints, resulting in a short-lived transitional style that, while still continuing to draw the characters well posed and on model, sacrifices smoothness of movement by the removal of a good deal of inbetweening, making motion look hesitant and stilted in many cycles and sequences. At least it wasn’t the Irv Spector influenced style that was to follow – it might be difficult to imagine how Audrey would have appeared in a flat UPA style, possibly explaining why this would be the last episode Paramount could afford.

Audrey prepares for a typical day of school. But her dog Pal is determined to accompany her this morning, defying the rules that dogs aren’t allowed in school. Audrey orders him to stay home despite his offering to carry her books – but the minute Audrey is out the door, Pal is following through a pet door. Every time Audrey points him toward home, Pal resumes the chase as soon as Audrey starts for the classroom. Audrey begins to employ tactics to elude her pooch, first using her books and strap to hook a limb of a tree overhanging a fence, then pulling herself up with the strap to hop over the fence before Pal can follow her down the block. She watches Pal pass through a fence knothole, and thinks she’s given him the slip, until she hears a familiar bark behind her. There is Pal, emerged from a tunnel he has dug under the fence. Next, Audrey ducks in a barrel, allowing Pal to pass. But she has trouble climbing out, and the barrel tips sideways, rolling Audrey down a hill to a service station. She encounters a large tire tied by a rope to one of the gas pumps, which swings like a pendulum upon impact, then swings back again to knock the barrel for a loop, over Pal’s head and into a tree. Audrey is revived amidst the barrel slats by slurps on her face from Pal, and it’s back to square one again. Audrey prodces a secret weapon – a rubber ball in her pocket, and tosses it in one direction for Pal to chase, while she runs the other way. Her pitching arm, however, is big league, as the bouncing ball makes a direct hit upon the windshield of a dog catcher’s wagon, smashing a hole in it. With his attention aroused, the catcher is quick to spy stray Pal retrieving the toy, and catches up with Pal just in front of the schoolgouse, so that Audrey witnesses the capture of Pal in his net. Now the plot begins to resemble Little Lulu’s “Man’s Pest Friend”, as Audrey brings her own brand of sabotage into play.

As the dog catcher opes the back doors of his already crowded wagon to toss in his new catch, Audrey snags the mesh of his net with a nail in the end of a long pole, and rips out the netting, allowing Pal to escape. The catcher obtains another net, plus a fishing pole. As Audrey and Pal hide behind the fence, the catcher lowers a line over the fencing, snagging Pal by the collar with his hook. Pal is transferred to the second net, and the catcher again heads for his truck. Audrey darts ahead behind the fence, finding a loose pivoting board. She brings the loose end of the board up as the catcher passes, flipping the handle of the net out of his hands. Pal runs for his life, the net still over him and handle dragging on the ground. The catcher leaps to seize the handle, but Audrey is one step ahead of him again, opening another gap in the fencing and taking a swipe at the handle with a sharp axe, severing the handle in two. Pal again runs, while the catcher is left with only a portion of the handle. Audrey catches up to Pal, and the two of them hide inside the walls of the city park. The catcher enters a moment later, but cannot find the mutt. All he sees is Audrey, sitting on a park bench, with a baby carriage close beside. The catcher pushes back the canopy of the carriage to look in, but Audrey cautions him, “Shh, you’ll wake the baby.” Seeing only the top of a baby bonnet, the catcher apologizes and tiptoes away. But a telltale yip is heard from behind him. As he turns to look, Audrey tries to cover by imitating the yips as if she were playfully uttering them herself. But the catcher remains suspicious, and a moment later, the meows of a cat are heard. Pal, who was in the baby bonnet all the time, pops his head out of the carriage to look. A small cat appears to be yowling at him from around a bush. A different camera angle reveals the catcher behind the bush on all fours, providing the yowls vocally, as the cat is really a hand puppet (an idea lifted from Disney’s Donald’s Dog Laundry (1940)). Pal falls for the trap, and is caught again. It’s back to the wagon for him, and this time the catcher succeeds in tossing Pal in and locking the door. But Audrey has one final trick up her sleeve, and firmly ties the doors of the wagon to a fire hydrant with a strong rope. As the catcher hits the accelerator and starts off, the cab and chassis of the wagon proceed forward, but the walls of the rear wagon are torn away and left behind, allowing all the dogs, including Pal, to escape. The catcher remains unaware of the loss of his cargo, and continues down the road a happy man. The final scene takes place in the school classroom, where a teacher is busy at the blackboard with her back turned to the room, while the sounds of shuffling and movement tell us that someone is arriving to occupy the classroom seats. Without looking, the teacher reflexively calls out, “Good morning, class.” The sole voice of Audrey answers, “Good Morning, teacher.” After a brief pause, we learn why no other voices are heard – instead, the classroom is filled with the sound of barks and yipping. The teacher turns to react in shock at the unexpected sight of Audrey, the only child in the class, surrounded by a full room of desks occupied by all of the dogs from the dog catcher’s wagon, for the fade out. A pleasant sign off for the series, and an example that Audrey, when not resorting to the dream world, could on rare occasions capably fill the shoes of Little Lulu after all.

As the dog catcher opes the back doors of his already crowded wagon to toss in his new catch, Audrey snags the mesh of his net with a nail in the end of a long pole, and rips out the netting, allowing Pal to escape. The catcher obtains another net, plus a fishing pole. As Audrey and Pal hide behind the fence, the catcher lowers a line over the fencing, snagging Pal by the collar with his hook. Pal is transferred to the second net, and the catcher again heads for his truck. Audrey darts ahead behind the fence, finding a loose pivoting board. She brings the loose end of the board up as the catcher passes, flipping the handle of the net out of his hands. Pal runs for his life, the net still over him and handle dragging on the ground. The catcher leaps to seize the handle, but Audrey is one step ahead of him again, opening another gap in the fencing and taking a swipe at the handle with a sharp axe, severing the handle in two. Pal again runs, while the catcher is left with only a portion of the handle. Audrey catches up to Pal, and the two of them hide inside the walls of the city park. The catcher enters a moment later, but cannot find the mutt. All he sees is Audrey, sitting on a park bench, with a baby carriage close beside. The catcher pushes back the canopy of the carriage to look in, but Audrey cautions him, “Shh, you’ll wake the baby.” Seeing only the top of a baby bonnet, the catcher apologizes and tiptoes away. But a telltale yip is heard from behind him. As he turns to look, Audrey tries to cover by imitating the yips as if she were playfully uttering them herself. But the catcher remains suspicious, and a moment later, the meows of a cat are heard. Pal, who was in the baby bonnet all the time, pops his head out of the carriage to look. A small cat appears to be yowling at him from around a bush. A different camera angle reveals the catcher behind the bush on all fours, providing the yowls vocally, as the cat is really a hand puppet (an idea lifted from Disney’s Donald’s Dog Laundry (1940)). Pal falls for the trap, and is caught again. It’s back to the wagon for him, and this time the catcher succeeds in tossing Pal in and locking the door. But Audrey has one final trick up her sleeve, and firmly ties the doors of the wagon to a fire hydrant with a strong rope. As the catcher hits the accelerator and starts off, the cab and chassis of the wagon proceed forward, but the walls of the rear wagon are torn away and left behind, allowing all the dogs, including Pal, to escape. The catcher remains unaware of the loss of his cargo, and continues down the road a happy man. The final scene takes place in the school classroom, where a teacher is busy at the blackboard with her back turned to the room, while the sounds of shuffling and movement tell us that someone is arriving to occupy the classroom seats. Without looking, the teacher reflexively calls out, “Good morning, class.” The sole voice of Audrey answers, “Good Morning, teacher.” After a brief pause, we learn why no other voices are heard – instead, the classroom is filled with the sound of barks and yipping. The teacher turns to react in shock at the unexpected sight of Audrey, the only child in the class, surrounded by a full room of desks occupied by all of the dogs from the dog catcher’s wagon, for the fade out. A pleasant sign off for the series, and an example that Audrey, when not resorting to the dream world, could on rare occasions capably fill the shoes of Little Lulu after all.

Next Week: School stories remain big. It’s the pictures that get small.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

While Francis, the Talking Mule predates Mr. Ed onscreen, it was Mr. Ed who first appeared in print. The first Mr. Ed story ran in Liberty magazine in September, 1937, and was written by Walter Brooks, creator of Freddy the Pig. Francis made his debut in a novel of the same name by David Stern III in 1946.

I find very little of educational value in “Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom”. Its account of the origins of musical instruments is entirely conjectural, and the cartoon has very little to say about how these instruments actually work. But I don’t think it would have been improved by making it more didactic. It’s true that the gut strings of the past went out of tune quickly and broke frequently, unlike their modern tungsten-silver alloy counterparts, which last longer and also have a superior tone. Thus strings have improved in quality over the years by making them out of costlier materials and charging a lot more money for them. This flies in the face of the economic theories of mass production and mass consumption propounded in “By Word of Mouse”, but there it is.

Nice to hear “Betty Co-Ed” in “Pest Pupil” and “Small Fry” in “Fishing Tackler”, those songs having been used by the Fleischer studio in cartoons made a quarter century earlier.

I guess most of Avery’s wolves are indeed nameless, although in “Northwest Hounded Police”, Droopy repeatedly addresses his adversary as “Joe”.