The school bell is ringing. Hope you didn’t sleep through the alarm again. Wipe that haze out of your eyes, grab your books, and skedaddle to class, as today’s lecture covers a good cross-section of studios, and some education for several animated superstars in their prime years of the 1930’s, so you won’t want to miss it. Forget this “dog ate my homework” stuff, and stay alert.

The school bell is ringing. Hope you didn’t sleep through the alarm again. Wipe that haze out of your eyes, grab your books, and skedaddle to class, as today’s lecture covers a good cross-section of studios, and some education for several animated superstars in their prime years of the 1930’s, so you won’t want to miss it. Forget this “dog ate my homework” stuff, and stay alert.

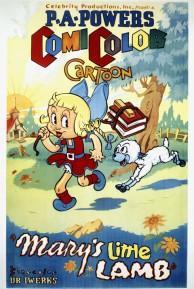

Mary’s Little Lamb (Ub Iwerks, ComiColor (2 strip Cinecolor) – 5/1/35, Ub Iwerks, dir.) – We start off on one of the weakest legs of today’s curriculum, being among the lesser efforts from the ComiColor series. It has a feeling of “been there, done that”, as it looks altogether too familiar – in essence amounting to a color reworking of Flip the Frog’s School Days, with all the spicy pre-code gags excised to satisfy the censors. Some animation is in fact directly lifted from the previous cartoon, just colored in to suit the occasion. Iwerks’ “The Old Crone” makes a crossover appearance to the color series to serve again as the schoolmarm. And very little is added to the script to provide new plot. Attempting to framework this product in the guise of a fairytale cartoon does not help things any, as it further waters down the overall impact of the film. to appeal only to the youngest members of the junior audience in a case of “over-Disneyfication”. It eventually made the home movie market through Catle Films, and, while I generally collect Iwerks’ titles pressed in genuine Cinecolor stock from this period, I have intentionally not gone out of my way to acquire a print of this production.

As the story opens, Mary is dancing and skipping along, singing of how happy she is that school is almost through. It is unknown who animates her, as her face resembles several past Iwerks’ females, with possible influence from the Grim Natwick Betty Boop style. But the animation is far from up to Natwick’s normal skill, as Mary appears to have no volume or weight, and despite her topheavy body design, tiptoes or shuffles along on her tiny feet as if there is no contact between them and the ground, making it seem entirely implausible to the eye that they are the source of Mary’s propulsion. Behind her appears the inevitable following lamb, whose dance moves are only slightly better in weight distribution than Mary’s. She shoos the lamb to no avail. Shots of the crowded schoolyard, and teacher ringing the morning bell, are direct lifts from “School Days”, as is teacher’s leading of the class in the usual “Good Morning To You”. Mary is redrawn in Flip’s place to crawl under the desks of the same students as in the prior cartoon to slip into her seat slightly late – although she does not come up in the bloomers of the kid behind her, as in the pre-code days. Teacher announces that in light of this being the last day of school, they will have a little entertainment. Mary, instead of Flip, takes her place on the piano stool, using a standard upright piano instead of a pump organ. She virtually disappears from the cartoon at this point.

As the story opens, Mary is dancing and skipping along, singing of how happy she is that school is almost through. It is unknown who animates her, as her face resembles several past Iwerks’ females, with possible influence from the Grim Natwick Betty Boop style. But the animation is far from up to Natwick’s normal skill, as Mary appears to have no volume or weight, and despite her topheavy body design, tiptoes or shuffles along on her tiny feet as if there is no contact between them and the ground, making it seem entirely implausible to the eye that they are the source of Mary’s propulsion. Behind her appears the inevitable following lamb, whose dance moves are only slightly better in weight distribution than Mary’s. She shoos the lamb to no avail. Shots of the crowded schoolyard, and teacher ringing the morning bell, are direct lifts from “School Days”, as is teacher’s leading of the class in the usual “Good Morning To You”. Mary is redrawn in Flip’s place to crawl under the desks of the same students as in the prior cartoon to slip into her seat slightly late – although she does not come up in the bloomers of the kid behind her, as in the pre-code days. Teacher announces that in light of this being the last day of school, they will have a little entertainment. Mary, instead of Flip, takes her place on the piano stool, using a standard upright piano instead of a pump organ. She virtually disappears from the cartoon at this point.

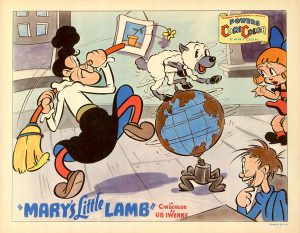

As teacher introduces each performer, the lamb creeps in from the wings, attempting to perform before the class, only to get the boot from teacher. First student performer is introduced as a soprano, but sings bass, copying the gag of the singing black kid from “School Days” of singing so low, he breaks a hole through the floorboards. Next is “little Percy” – the only sequence that somehow got past the censors of questionable note, as Percy performs a decidedly effeminate and overly long dance, prompting the students to comment “Whoooooo” at his gayness. Then teacher, referring to the class as “you lucky people”, decides to perform her own dance. The lamb periodically reappears to hog the stage from her, performing a very unenergetic shimmy, until teacher grabs a broom to give chase around the classroom. The lamb jumps into teacher’s desk drawer, and when teacher sticks her head inside, opens another drawer above her, briefly trapping the teacher between them and allowing the lamb to whack teacher in the rear end. After running but getting nowhere atop a globe, the lamb hides inside a pot bellied stove. Teacher reaches in and retrieves the lamb, covered in black soot. She takes him over her knee and administers a spanking, both figures disappearing in a cloud of black soot. When the dust clears, the lamb is white again, but teacher is covered in black from head to toe, smiling “sheepishly” at the camera for the iris out.

As teacher introduces each performer, the lamb creeps in from the wings, attempting to perform before the class, only to get the boot from teacher. First student performer is introduced as a soprano, but sings bass, copying the gag of the singing black kid from “School Days” of singing so low, he breaks a hole through the floorboards. Next is “little Percy” – the only sequence that somehow got past the censors of questionable note, as Percy performs a decidedly effeminate and overly long dance, prompting the students to comment “Whoooooo” at his gayness. Then teacher, referring to the class as “you lucky people”, decides to perform her own dance. The lamb periodically reappears to hog the stage from her, performing a very unenergetic shimmy, until teacher grabs a broom to give chase around the classroom. The lamb jumps into teacher’s desk drawer, and when teacher sticks her head inside, opens another drawer above her, briefly trapping the teacher between them and allowing the lamb to whack teacher in the rear end. After running but getting nowhere atop a globe, the lamb hides inside a pot bellied stove. Teacher reaches in and retrieves the lamb, covered in black soot. She takes him over her knee and administers a spanking, both figures disappearing in a cloud of black soot. When the dust clears, the lamb is white again, but teacher is covered in black from head to toe, smiling “sheepishly” at the camera for the iris out.

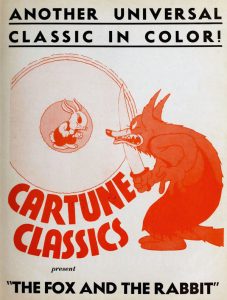

Fox and the Rabbit (Lantz/Universal, Cartune Classics (2 strip Technicolor) – 9/23/35, Walter Lantz, dir.) is a milestone in Universal animation. While Oswald Rabbit had been made rounder and cuter in design to make animator’s lives simpler during the Lantz development of the character, he had retained several of the features of Disney’s original design, including solid black ears like Mickey’s, and black head and body almost proportionate to the similar development of the Mouse over the years. For this production, something was envisioned to make the rabbit completely distinguishable from the Oswald model. So instead of black, the rabbit becomes all white! The design could be said to still owe a great deal to Disney, but from a later era, as it is close in resemblance to the models used in Disney’s 1934 Easter short, “Funny Little Bunnies”. Lantz’s new rabbit thus has a feeling of plushness and furriness that Oswald never displayed, and is substantially more realistic in appearance, although featuring round circles in cheek detail, giving a certain cartoony feel to the facial features. It is unknown whether this film was initially intended to influence and premiere a new design for Oswald, or merely to present a miscellaneous rabbit, as Oswald’s name is nowhere mentioned in the film’s titles or content (while two preceding efforts to thrust Oswald into the color market, “Toyland Premiere” and “Springtime Serenade”, had specifically named the rabbit in either the title card or in dialogue within the cartoon). Nevertheless, audience reaction to the design must have been considered positive by the studio, because within a matter of a few episodes, Oswald appears in “Case of the Lost Sheep” in the same new design, which would be retained for the series until 1938.

Fox and the Rabbit (Lantz/Universal, Cartune Classics (2 strip Technicolor) – 9/23/35, Walter Lantz, dir.) is a milestone in Universal animation. While Oswald Rabbit had been made rounder and cuter in design to make animator’s lives simpler during the Lantz development of the character, he had retained several of the features of Disney’s original design, including solid black ears like Mickey’s, and black head and body almost proportionate to the similar development of the Mouse over the years. For this production, something was envisioned to make the rabbit completely distinguishable from the Oswald model. So instead of black, the rabbit becomes all white! The design could be said to still owe a great deal to Disney, but from a later era, as it is close in resemblance to the models used in Disney’s 1934 Easter short, “Funny Little Bunnies”. Lantz’s new rabbit thus has a feeling of plushness and furriness that Oswald never displayed, and is substantially more realistic in appearance, although featuring round circles in cheek detail, giving a certain cartoony feel to the facial features. It is unknown whether this film was initially intended to influence and premiere a new design for Oswald, or merely to present a miscellaneous rabbit, as Oswald’s name is nowhere mentioned in the film’s titles or content (while two preceding efforts to thrust Oswald into the color market, “Toyland Premiere” and “Springtime Serenade”, had specifically named the rabbit in either the title card or in dialogue within the cartoon). Nevertheless, audience reaction to the design must have been considered positive by the studio, because within a matter of a few episodes, Oswald appears in “Case of the Lost Sheep” in the same new design, which would be retained for the series until 1938.

This is the only installment in the Cartune Classics series currently known to exist in one surviving print with full credits, including “Carl Laemmle presents” above the title. Original credits were set up on a storybook motif, with three-dimensional pages flipped to begin the tale (reissue versions only preserve this for the closing card). The bell rings in the tower of the little red school house. The rabbit (we’ll call him Oswald even if the studio didn’t as yet) is getting his ears washed by his Mother in preparation for the day’s lessons. She tells him “Don’t be late. Don’t play hookey.” With a kiss goodbye, Oswald is off. However, halfway to the school is a vacant lot, surrounded by a fence with several pickets missing in the middle. This is the hangout for a local fox, who uses the lot to conduct his dirty work. As Oswald approaches, the fox attaches an old windowshade to the top crossbeam of the fence, over the area of the missing pickets. On the inside of the windowshade, he has painted a scemic of a carrot patch, containing several rows deep of carrots ripe for picking. He also hangs out a sign on the fence near the windowshade, reading “Delicious Carrot Patch – Keep Out”. The premise of this ruse is, to say the least, strange. It might be convincing if viewed from a distance, but one would expect the benefits of beta-carotene to have given a rabbit sufficiently strong eyesight to allow for depth perception – and detection of a lack of it in the false backdrop. Nevertheless, Oswald stops in his tracks upon spying the tempting image of a field of orange treats, and walks right up to the backdrop, still entirely unaware it is not a field of choice vegetables before him! As he bends to try to pick one when no one is looking, the only thing that stops him is memory of his mother’s words to not be late or play hookey. Obeying her instruction, Oswald hurries along to school, as the hand of the fox reaches out from behind the backdrop, but can only grasp thin air, leaving the fox to snap his fingers as if to say “Almost had him.”

This is the only installment in the Cartune Classics series currently known to exist in one surviving print with full credits, including “Carl Laemmle presents” above the title. Original credits were set up on a storybook motif, with three-dimensional pages flipped to begin the tale (reissue versions only preserve this for the closing card). The bell rings in the tower of the little red school house. The rabbit (we’ll call him Oswald even if the studio didn’t as yet) is getting his ears washed by his Mother in preparation for the day’s lessons. She tells him “Don’t be late. Don’t play hookey.” With a kiss goodbye, Oswald is off. However, halfway to the school is a vacant lot, surrounded by a fence with several pickets missing in the middle. This is the hangout for a local fox, who uses the lot to conduct his dirty work. As Oswald approaches, the fox attaches an old windowshade to the top crossbeam of the fence, over the area of the missing pickets. On the inside of the windowshade, he has painted a scemic of a carrot patch, containing several rows deep of carrots ripe for picking. He also hangs out a sign on the fence near the windowshade, reading “Delicious Carrot Patch – Keep Out”. The premise of this ruse is, to say the least, strange. It might be convincing if viewed from a distance, but one would expect the benefits of beta-carotene to have given a rabbit sufficiently strong eyesight to allow for depth perception – and detection of a lack of it in the false backdrop. Nevertheless, Oswald stops in his tracks upon spying the tempting image of a field of orange treats, and walks right up to the backdrop, still entirely unaware it is not a field of choice vegetables before him! As he bends to try to pick one when no one is looking, the only thing that stops him is memory of his mother’s words to not be late or play hookey. Obeying her instruction, Oswald hurries along to school, as the hand of the fox reaches out from behind the backdrop, but can only grasp thin air, leaving the fox to snap his fingers as if to say “Almost had him.”

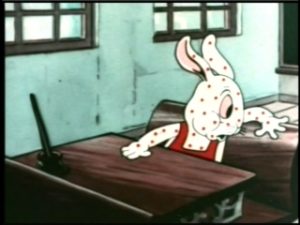

In school, Oswald is only able to sing a half-hearted “We’re glad to see you” in the good morning song. He daydreams at his desk of the carrots he left behind. He stares at the teacher, and suddenly sees an odd sight – a hallucination of the professor trasforned into a giant carrot working a the blackboard. Wiping his eyes, Oswald sees another odd vision at closer range – a carrot in his inkwell. About to take a bite of it, Oswald snaps back to reality, the carrot in his hand transforming into its actual form as a fountain pen. Frustrated, Oswald tosses the pen back into the inkwell, which splatters a spray of red ink at him, spreading fine dots across his face and hands. Looking at the results, Oswald gets a sudden inspiration providing the perfect solution to get out of school – measles! To place the film into proper historical perspective, it should be noted that measles was sort of the COVID of its day, much more feared than in the modern world, and considered highly transmissible enough to be a pretty-near guarantee of an order of quarantine by the local health department. When Oswald begins to boast to the student next to him, “I’ve got the measles”, she shrieks in fear and vanishes quickly. Other students react in the same way. Reissue prints of this film present a mystery, as about 20 seconds of footage has the sound fade away entirely, then gradually fade back in. Action on screen depicts the professor grabbing a long pole, hooking Oswald with it by the suspender strap, and depositing him out the window onto the ground, then stating something to Oswald before slamming the window. Before a complete print turned up, I had thought they were covering over some dated reference to the more severe opinion of measles at the time – perhaps the professor accusing Oswald of trying to kill them all. But the original issue print has the professor saying nothing more than “Go home. Go to bed. Scram!” This does not sound like a case for censorship. It may thus be speculated that the cut was not for content, but possibly necessitated by a large break or deterioration in the soundtrack negative, which could only be covered by inserting a silence. This theory may not be far-fetched, as the reissue picture element next shows another telltale sign of wear and tear, in a scene where Oswald activates a watering hose to wash the red ink spots off. All current prints show two jagged breaks across the picture, briefly upsetting the alignment of the red and bluegreen color negatives for a few frames following the glue-togethers of the breaks. Such very-visible film splits are unfortunately not uncommon among 1930’s Lantz negatives, with many films exhibiting same in several places in both early TV distribution prints and in Castle Films home movie releases of the 1940’s and ‘50’s (a nasty one, for example, appears in the middle of the closing shot of Oswald’s last black and white, “Happy Scouts”, a few years later. Universal has never digitally repaired these artifacts, and it seems high time some massive restoration work was in order.

In school, Oswald is only able to sing a half-hearted “We’re glad to see you” in the good morning song. He daydreams at his desk of the carrots he left behind. He stares at the teacher, and suddenly sees an odd sight – a hallucination of the professor trasforned into a giant carrot working a the blackboard. Wiping his eyes, Oswald sees another odd vision at closer range – a carrot in his inkwell. About to take a bite of it, Oswald snaps back to reality, the carrot in his hand transforming into its actual form as a fountain pen. Frustrated, Oswald tosses the pen back into the inkwell, which splatters a spray of red ink at him, spreading fine dots across his face and hands. Looking at the results, Oswald gets a sudden inspiration providing the perfect solution to get out of school – measles! To place the film into proper historical perspective, it should be noted that measles was sort of the COVID of its day, much more feared than in the modern world, and considered highly transmissible enough to be a pretty-near guarantee of an order of quarantine by the local health department. When Oswald begins to boast to the student next to him, “I’ve got the measles”, she shrieks in fear and vanishes quickly. Other students react in the same way. Reissue prints of this film present a mystery, as about 20 seconds of footage has the sound fade away entirely, then gradually fade back in. Action on screen depicts the professor grabbing a long pole, hooking Oswald with it by the suspender strap, and depositing him out the window onto the ground, then stating something to Oswald before slamming the window. Before a complete print turned up, I had thought they were covering over some dated reference to the more severe opinion of measles at the time – perhaps the professor accusing Oswald of trying to kill them all. But the original issue print has the professor saying nothing more than “Go home. Go to bed. Scram!” This does not sound like a case for censorship. It may thus be speculated that the cut was not for content, but possibly necessitated by a large break or deterioration in the soundtrack negative, which could only be covered by inserting a silence. This theory may not be far-fetched, as the reissue picture element next shows another telltale sign of wear and tear, in a scene where Oswald activates a watering hose to wash the red ink spots off. All current prints show two jagged breaks across the picture, briefly upsetting the alignment of the red and bluegreen color negatives for a few frames following the glue-togethers of the breaks. Such very-visible film splits are unfortunately not uncommon among 1930’s Lantz negatives, with many films exhibiting same in several places in both early TV distribution prints and in Castle Films home movie releases of the 1940’s and ‘50’s (a nasty one, for example, appears in the middle of the closing shot of Oswald’s last black and white, “Happy Scouts”, a few years later. Universal has never digitally repaired these artifacts, and it seems high time some massive restoration work was in order.

Finally free to do as he pleases, Oswald returns to the vacant lot, where the fox again pulls down the false backdrop. Blind as a bat, Oswald walks right up to the backdrop and reaches for a carrot. Only his hand making physical contact with the curtain finally wisens him up that something isn’t right. The blind snaps upward, and the fox’s menacing form is revealed. A bit of back and forth chasing, and Oswald is caught, and carried off by his ears to the fox’s lair. In a tumbledown shack the fox calls hime, Oswald watches in fright as the fox sharpens a large knife razor-fine. Plucking a hair out of Oswald’s pelt, the fox tests the blade, by slicing the hair into about eight separate strands. He then lunges for Oswald, who jumps and ducks in alternating moves to avoid contact with the blade. Oswald leaps off the counter and makes a dash across the room, while the fox takes aim and tosses the knife. Oswald stays one leap ahead of the flying blade, which cuts effortlessly thorough a goldfish bowl (and the goldfish), a wooden table, and a lit kerosene lamp – parting the flame in two. Oswald scrambles into the kitchen sink, as the knife lodges into the wall only an inch above his head. Oswald lifts a strainer from the sink drain, and uses the drain as a new rabbit hole. The fox is too late to grab Oswald’s disappearing tail, but sees the bulge of Oswald inside the pipes, about to descend below the flooring. The fox grabs a length of pipe like it was made of flexible hose, and begings yanking the metal tubing from the wall, to keep Oswald from progressing out of the room. A shot of the shack’s bathroom reveals all the sink and bathtub plumbing being dragged into the walls as if also made of soft pliable materials. Before long, a coil of pipe pried from the walls rests at the fox’s feet, as a final tug severs the last section of pipe from a connecting fixture, revealing Oswald. Ozzie runs for a kitchen cupboard, and hides within. The fox tugs at the cupboard doors, unhinging one, and staggers backward, his rear end landing in the open door of the oven, for a hotfoot to the posterior.

Finally free to do as he pleases, Oswald returns to the vacant lot, where the fox again pulls down the false backdrop. Blind as a bat, Oswald walks right up to the backdrop and reaches for a carrot. Only his hand making physical contact with the curtain finally wisens him up that something isn’t right. The blind snaps upward, and the fox’s menacing form is revealed. A bit of back and forth chasing, and Oswald is caught, and carried off by his ears to the fox’s lair. In a tumbledown shack the fox calls hime, Oswald watches in fright as the fox sharpens a large knife razor-fine. Plucking a hair out of Oswald’s pelt, the fox tests the blade, by slicing the hair into about eight separate strands. He then lunges for Oswald, who jumps and ducks in alternating moves to avoid contact with the blade. Oswald leaps off the counter and makes a dash across the room, while the fox takes aim and tosses the knife. Oswald stays one leap ahead of the flying blade, which cuts effortlessly thorough a goldfish bowl (and the goldfish), a wooden table, and a lit kerosene lamp – parting the flame in two. Oswald scrambles into the kitchen sink, as the knife lodges into the wall only an inch above his head. Oswald lifts a strainer from the sink drain, and uses the drain as a new rabbit hole. The fox is too late to grab Oswald’s disappearing tail, but sees the bulge of Oswald inside the pipes, about to descend below the flooring. The fox grabs a length of pipe like it was made of flexible hose, and begings yanking the metal tubing from the wall, to keep Oswald from progressing out of the room. A shot of the shack’s bathroom reveals all the sink and bathtub plumbing being dragged into the walls as if also made of soft pliable materials. Before long, a coil of pipe pried from the walls rests at the fox’s feet, as a final tug severs the last section of pipe from a connecting fixture, revealing Oswald. Ozzie runs for a kitchen cupboard, and hides within. The fox tugs at the cupboard doors, unhinging one, and staggers backward, his rear end landing in the open door of the oven, for a hotfoot to the posterior.

While the fox tries to put out the smoke clouds, Oswald looks around for some idea of what to do next. He spots a bottle of bright red ketchup. Whapping the bottom of the bottle, he gets the stuff to splatter, producing again the same red spots as in his masquerade at the school. The fox returns, and reaches into the cupboard to get a hold of Oswald by the ears again – then reacts in shock as he sees what he is holding. “Measles!”. he shouts, and exits in a zoom that leaves his silhouette hole in the door. Were Oswald of average intelligence, he could have used this opportunity to race home. But he’s having too much fun with his game, and pursues the fox instead, tauntung him with repeated calls of “I’ve got the measles” while the frantic fox tries to get anyplace Oswald isn’t. The fox races across a pond on stepping stones, and Oswald follows. But the center stone is not a stone at all, but the rising back of a turtle shell. Still loving to scare anybody, Oswald shows the turtle, “Measles! Measles!” The turtle shakes his shell, tossing Oswald off his back into the water. Oswald climbs out on the opposite bank, shaking kimself and forming a puddle of water around him. He fails to observe that the puddle is littered with little red dots – which are no longer on Oswald’s face. The fox looks out from behind a tree, and instantly notices that something is different about Oswald’s complexion. He stands his ground with a smile of confidence, while Oswald puzzles over why he is no longer scared – until he looks down at the spots around his feet. The chasing roles are reversed back to normal, with Oswald the pursued. Ozzie runs through a hollow log, the fox right behind him, and they run in circles in and out of the log, until Oswald finally yells a loud call for “Mama!” Mother emerges from home, sizes up the danger, and grabs her rolling pin. At the log, as Oswald passes her through one end, she brings down her rolling pin squarely on the fox’s head as it emerges. The fox pops out the log’s other end, where Oswald hooks the fox’s suspenders to a small outgrowth of the log. Then, he and Ma team up against the fox, Oswald lifting and pulling the fox backward, to use his suspenders as a slingshot launcher through the log, while Mama waits to apply more knocks from her rolling pin each time the fox’s head emerges on her side. Eventually, a shot from Oswald overextends its range, launching the fox over Mama’s head, to land squarely on top of a farmer’s hive of honeybees. The fox makes a painful exit as the bees sting at and devour the fur off his tail. Oswald and Mama sit laughing at the fox’s distress – until Mama remembers, why isn’t Oswald in school? She lifts the young rabbit over her knee, lowers his trousers, and applies some good old fashioned discipline, leaving a bright red handprint visible from repeated spanking across Oswald’s rear end. A song narrator comments that those that pretend, always get it in the end, for the closing moral, as the storybook also closes.

While the fox tries to put out the smoke clouds, Oswald looks around for some idea of what to do next. He spots a bottle of bright red ketchup. Whapping the bottom of the bottle, he gets the stuff to splatter, producing again the same red spots as in his masquerade at the school. The fox returns, and reaches into the cupboard to get a hold of Oswald by the ears again – then reacts in shock as he sees what he is holding. “Measles!”. he shouts, and exits in a zoom that leaves his silhouette hole in the door. Were Oswald of average intelligence, he could have used this opportunity to race home. But he’s having too much fun with his game, and pursues the fox instead, tauntung him with repeated calls of “I’ve got the measles” while the frantic fox tries to get anyplace Oswald isn’t. The fox races across a pond on stepping stones, and Oswald follows. But the center stone is not a stone at all, but the rising back of a turtle shell. Still loving to scare anybody, Oswald shows the turtle, “Measles! Measles!” The turtle shakes his shell, tossing Oswald off his back into the water. Oswald climbs out on the opposite bank, shaking kimself and forming a puddle of water around him. He fails to observe that the puddle is littered with little red dots – which are no longer on Oswald’s face. The fox looks out from behind a tree, and instantly notices that something is different about Oswald’s complexion. He stands his ground with a smile of confidence, while Oswald puzzles over why he is no longer scared – until he looks down at the spots around his feet. The chasing roles are reversed back to normal, with Oswald the pursued. Ozzie runs through a hollow log, the fox right behind him, and they run in circles in and out of the log, until Oswald finally yells a loud call for “Mama!” Mother emerges from home, sizes up the danger, and grabs her rolling pin. At the log, as Oswald passes her through one end, she brings down her rolling pin squarely on the fox’s head as it emerges. The fox pops out the log’s other end, where Oswald hooks the fox’s suspenders to a small outgrowth of the log. Then, he and Ma team up against the fox, Oswald lifting and pulling the fox backward, to use his suspenders as a slingshot launcher through the log, while Mama waits to apply more knocks from her rolling pin each time the fox’s head emerges on her side. Eventually, a shot from Oswald overextends its range, launching the fox over Mama’s head, to land squarely on top of a farmer’s hive of honeybees. The fox makes a painful exit as the bees sting at and devour the fur off his tail. Oswald and Mama sit laughing at the fox’s distress – until Mama remembers, why isn’t Oswald in school? She lifts the young rabbit over her knee, lowers his trousers, and applies some good old fashioned discipline, leaving a bright red handprint visible from repeated spanking across Oswald’s rear end. A song narrator comments that those that pretend, always get it in the end, for the closing moral, as the storybook also closes.

.

Educated Fish (Fleischer/Paramount, Color Classics, 10/29/37 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Myron Waldman/Hicks Lokey, anim.) – It would take the Fleischers awhie to master the animation of water. One might argue they never quite got the hang of it, though they made daring attempts to depict it during the storm sequences of Gulliver’s Travels – as they were never able to come close to the realism Disney would present only a year later in Pinocchio and Fantasia. The opening shot of this cartoon is thus a bit embarrassing, using overly-bright shades of blue and repeating wave patterns that look absolutely artificial. At least they are as competent as any other studio once the camera dips below the waterline, at depicting rippling effects over backgrounds to project the image of life underwater. There, we visit what may be animation’s first underwater classroom – the A.B. Sea School for Fish. In the schoolyard, several fish dance a maypole dance, holding onto the tentacles of an octopus. A teacher (who would become known in a later sequel to this film as Miss Pickerel) rings a hand bell for class to commence. Most notable among the entering students is a sardine can which propels itself onto the porch, unwinds its lid, and reveals six young students with their schoolbooks inside, to greet the teacher. “Oh, how cute,” she comments, but has a very different reaction when she sees a small orange fish, one Tommy Cod, who wears a shirt with horizontal stripe and a derby reminding one of the studio’s later use of Spooky – obviously a fish who wants to be a “little tough guy”. Tommy resists the prompting of the school bell, sticks out his tongue at teacher, and kicks his schoolbooks into the open shell of a clam, who clamps shut upon the books and licks his “lips” at their flavor. Tommy turns to depart, but Miss Pickerel grabs a net on a pole and snags the little one before he can escape, then hurls him inside the school (a building constructed of an old sunken ale barrel). Teacher swims up to her desk, and announces that she will read a story, “The Tale of a Fish” by A. Fin. The reading never happens, as Tommy disrupts the class by sprinkling pepper upon the nose of a sawfish, causing his to saw his desk in two with the resulting sneeze. In one of the film’s more clever gags, teacher experiences one moment of peace, as another student presents her with an apple. Teacher thanks the student gratefully, then reaches a fin into a small hole in the apple, producing a worm. Tossing the apple away over her shoulder, she eats the worm instead! Teacher then changes to a more essential lesson: how to avoid playing “hookey” with the human race. In a sing-song resembling the repeating verses of “Schnitzelbank”, teacher points to a pull-down chart depicting a fishing pole, reel that winds, line so strong, worm that squirms, hook so sharp, and frying pan. Tommy has better things to do than pay attention to the lesson, such as playing a self-constructed pinball machine he has built inside his desk, complete with three small clamshells to catch the marbles fired as points are scored, and then hooking a slingshot to his tail to take pot-shots at his classmates and the teacher, finally knocking Miss Pickerel into the chart and rolling her up inide it like a windowshade. Teacher frees herself, and calls Tommy to the front of the class, asking hum to identify all of the objects on the chart. Tommy, having failed to listen, has no idea. Teacher locks Tommy in a utility room with a textbook, and says he’ll stay there until he learns the lesson. As soon as the door is closed, Tommy drops the textbook, and looks around for an easy method of escape – an open window, which he merely swims up to, and is free. “No more pencils, no more books”, Tommy sings in the age-old rhyme, as he skips happily down the road.

Educated Fish (Fleischer/Paramount, Color Classics, 10/29/37 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Myron Waldman/Hicks Lokey, anim.) – It would take the Fleischers awhie to master the animation of water. One might argue they never quite got the hang of it, though they made daring attempts to depict it during the storm sequences of Gulliver’s Travels – as they were never able to come close to the realism Disney would present only a year later in Pinocchio and Fantasia. The opening shot of this cartoon is thus a bit embarrassing, using overly-bright shades of blue and repeating wave patterns that look absolutely artificial. At least they are as competent as any other studio once the camera dips below the waterline, at depicting rippling effects over backgrounds to project the image of life underwater. There, we visit what may be animation’s first underwater classroom – the A.B. Sea School for Fish. In the schoolyard, several fish dance a maypole dance, holding onto the tentacles of an octopus. A teacher (who would become known in a later sequel to this film as Miss Pickerel) rings a hand bell for class to commence. Most notable among the entering students is a sardine can which propels itself onto the porch, unwinds its lid, and reveals six young students with their schoolbooks inside, to greet the teacher. “Oh, how cute,” she comments, but has a very different reaction when she sees a small orange fish, one Tommy Cod, who wears a shirt with horizontal stripe and a derby reminding one of the studio’s later use of Spooky – obviously a fish who wants to be a “little tough guy”. Tommy resists the prompting of the school bell, sticks out his tongue at teacher, and kicks his schoolbooks into the open shell of a clam, who clamps shut upon the books and licks his “lips” at their flavor. Tommy turns to depart, but Miss Pickerel grabs a net on a pole and snags the little one before he can escape, then hurls him inside the school (a building constructed of an old sunken ale barrel). Teacher swims up to her desk, and announces that she will read a story, “The Tale of a Fish” by A. Fin. The reading never happens, as Tommy disrupts the class by sprinkling pepper upon the nose of a sawfish, causing his to saw his desk in two with the resulting sneeze. In one of the film’s more clever gags, teacher experiences one moment of peace, as another student presents her with an apple. Teacher thanks the student gratefully, then reaches a fin into a small hole in the apple, producing a worm. Tossing the apple away over her shoulder, she eats the worm instead! Teacher then changes to a more essential lesson: how to avoid playing “hookey” with the human race. In a sing-song resembling the repeating verses of “Schnitzelbank”, teacher points to a pull-down chart depicting a fishing pole, reel that winds, line so strong, worm that squirms, hook so sharp, and frying pan. Tommy has better things to do than pay attention to the lesson, such as playing a self-constructed pinball machine he has built inside his desk, complete with three small clamshells to catch the marbles fired as points are scored, and then hooking a slingshot to his tail to take pot-shots at his classmates and the teacher, finally knocking Miss Pickerel into the chart and rolling her up inide it like a windowshade. Teacher frees herself, and calls Tommy to the front of the class, asking hum to identify all of the objects on the chart. Tommy, having failed to listen, has no idea. Teacher locks Tommy in a utility room with a textbook, and says he’ll stay there until he learns the lesson. As soon as the door is closed, Tommy drops the textbook, and looks around for an easy method of escape – an open window, which he merely swims up to, and is free. “No more pencils, no more books”, Tommy sings in the age-old rhyme, as he skips happily down the road.

Up ahead of him descends into the watery depths a line and a hook, upon which sits a female worm. In under-the-breath muttering, closely resembling the moans of Mae West, she spots Tommy coming her way, and pulls out a small stick of lipstick to make herself more attractive before he arrives. Coaxing Tommy over, she asks if he’d like to play a little hookey. Tommy almost blushes in shy embarrassment, not noticing that the worm has more serious intentions in mind, as she pulls out a small blackjack and bops Tommy on the head. Hooking Tommy’s shirt to the fishhook, the worm tugs at the line, and yells, “Take it away!” Amidst a jazzy and manic Sammy Timberg underscore, Tommy is whisked upwards by the line. Coming to, he puts up a desperate struggle, tugging with all his might, then running with the line, while the clever fisherman “plays” with him to let him tire himself out. Tommy struggles to reach and hang onto the edge of a clamshell, using one fin to mop perspiration off his brow (a subtle gag, as how can perspiration build up underwater?). The line is tugged harder by the fisherman, opening the clam, who is asleep in a nightshirt in a small bed inside. The clam is awakened, and does not appreciate the intrusion into his privacy, pulling out a club and smacking Tommy’s “hands”. Rising again from the pull of the reel, Tommy darts in another direction, and grabs hold of an octopus’s tentacle. “Oww-w-w-w!”, yells the octopus as the line drags Tommy backwards, the creature’s voice sounding something like the shouts of Ed Wynn. Tommy is forced to let go. As he rises even faster toward the surface, he barely dodges three lunges by a shark to make him a “fast food” lunch. The line is pulled into a rowboat above, and a fat fisherman detaches the hook from Tommy’s shitt. Tommy flips around on the boat deck, staying one flop ahead of the fisher’s grabby hands, then slips his way up the fisherman’s trouser leg. The man is struck with an involuntary case of giggles at Tommy’s flipping, and unable to get a grip on the little guy. Tommy escapes out the man’s shirt and back into the water, biting at the man’s finger as he tries to reach into the water after Tommy. Tommy swims so fast for the ocean bottom, his head and bony backbone briefly separate from the rest of his body, and he has to slow slightly to let the rest of himself catch up. Transforming into a torpedo, he rockets back into the school closet, and out the door into the classroom. Now fully versed in the danger from firsthand experience, Tommy is able to recite the lesson perfectly at mile-a-minite speed, adding “I’ll be a good little boy and never do it again! Honest!” Nominated for an Academy Award.

Up ahead of him descends into the watery depths a line and a hook, upon which sits a female worm. In under-the-breath muttering, closely resembling the moans of Mae West, she spots Tommy coming her way, and pulls out a small stick of lipstick to make herself more attractive before he arrives. Coaxing Tommy over, she asks if he’d like to play a little hookey. Tommy almost blushes in shy embarrassment, not noticing that the worm has more serious intentions in mind, as she pulls out a small blackjack and bops Tommy on the head. Hooking Tommy’s shirt to the fishhook, the worm tugs at the line, and yells, “Take it away!” Amidst a jazzy and manic Sammy Timberg underscore, Tommy is whisked upwards by the line. Coming to, he puts up a desperate struggle, tugging with all his might, then running with the line, while the clever fisherman “plays” with him to let him tire himself out. Tommy struggles to reach and hang onto the edge of a clamshell, using one fin to mop perspiration off his brow (a subtle gag, as how can perspiration build up underwater?). The line is tugged harder by the fisherman, opening the clam, who is asleep in a nightshirt in a small bed inside. The clam is awakened, and does not appreciate the intrusion into his privacy, pulling out a club and smacking Tommy’s “hands”. Rising again from the pull of the reel, Tommy darts in another direction, and grabs hold of an octopus’s tentacle. “Oww-w-w-w!”, yells the octopus as the line drags Tommy backwards, the creature’s voice sounding something like the shouts of Ed Wynn. Tommy is forced to let go. As he rises even faster toward the surface, he barely dodges three lunges by a shark to make him a “fast food” lunch. The line is pulled into a rowboat above, and a fat fisherman detaches the hook from Tommy’s shitt. Tommy flips around on the boat deck, staying one flop ahead of the fisher’s grabby hands, then slips his way up the fisherman’s trouser leg. The man is struck with an involuntary case of giggles at Tommy’s flipping, and unable to get a grip on the little guy. Tommy escapes out the man’s shirt and back into the water, biting at the man’s finger as he tries to reach into the water after Tommy. Tommy swims so fast for the ocean bottom, his head and bony backbone briefly separate from the rest of his body, and he has to slow slightly to let the rest of himself catch up. Transforming into a torpedo, he rockets back into the school closet, and out the door into the classroom. Now fully versed in the danger from firsthand experience, Tommy is able to recite the lesson perfectly at mile-a-minite speed, adding “I’ll be a good little boy and never do it again! Honest!” Nominated for an Academy Award.

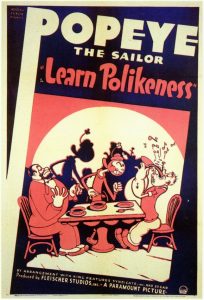

Learn Polikeness (Fleischer/Paramount Popeye, 2/18/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., David Tendlar/Nicholas Tafuri, anim.) – And now some schooling for the adults. Bluto has attempted to clean up his act, opening a new line of business – Prof. Bluteau’s School of Etiquette (with the motto, “For a little dough, you can be well bred.” In a swank penthouse campus atop the “Fine Manor Apartments”, we find that it isn’t necessary to put on airs when nobody’s looking – thus, we get a secret glimpse at the real Bluto in his private office – dressed in an undershirt, his feet up on the desk clad only in stockings with holes in the toes, awkwardly chomping and gulping down a banana while reading a book entitled “Cops and Robbers”. Passing by below arrive the inevitable cash customers: Olive, dragging Popeye in to become a refined gentleman. Hearing the doorbell, Bluto is quick to revert to professional form, and with a few quick moves, has outfitted himself in tuxedo, fancy shoes and vest. “Entree”, he greets them at the door. “I already ‘et”, retorts Popeye, misunderstanding the professor’s lingo. “I want this to become a gentleman”, Olive tells Bluto. Bluto pulls out a monacle and closely observes Popeye. “Not so good…I wonder if that thing is human”, he mutters. Bluto’s firsr move is to throw Popeye’s pipe away into a nearby planter, where a daisy withers from the smell of its smoke. “Hey, what’s the idea? Do ya wanna spoil the flavor?”, complains Popeye. Bluto next demonstrates the proper way to greet a lady, making a low bow, taking Olive’s hand and kissing it. “Merci Bouquet”, responds Olive. Popeye shows his own idea of how to greet a lady – unceremoniously running up to her, shaking her hand vigorously, and complimenting her with “Well shiver me timbers! Yon’re the trimmest little craft I ever seen.” With disdain, Bluto escorts Olive away, and demonstrates how to escort her, arm in arm, up a flight of stairs. “She was always able to walk up herself before”, mumbles Popeye. Bluto directs Popeye to escort her back down. Popeye does so by seating Olive on the staircase railing, pushing her into a rapid downhill slide, then catching her on the other end. “Voulex voulez voo, and I do mean you”, says Popeye in a bow. Bluto’s third lesson demonstrates how to put on, then remove, a lady’s wrap. Seeing the garment go on and off so quickly, Popeye asks why’d he put it on her in the first place. Bluto asks Popeye to do it. Popeye tosses the coat into the air, then tickles Olive under the arms, causing her to raise her limbs high above her head, just in time to receive the falling coat. However, removing the wrap isn’t so easy, as Popeye yanks it down instead of up, flipping Olive’s feet out from under her in a backwards pratfall. Olive is disgusted, and Bluto grabs a book of etiquette, tosses it in Poeye’s face, and tells him, “Read this, and come back in ten years!”. Popeye crashes into the opposite wall, dislodging a painting from the wall. Its frame falls off, and the canvas wraps itself around Poeye’s head in the shape of a dunce cap.

Learn Polikeness (Fleischer/Paramount Popeye, 2/18/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., David Tendlar/Nicholas Tafuri, anim.) – And now some schooling for the adults. Bluto has attempted to clean up his act, opening a new line of business – Prof. Bluteau’s School of Etiquette (with the motto, “For a little dough, you can be well bred.” In a swank penthouse campus atop the “Fine Manor Apartments”, we find that it isn’t necessary to put on airs when nobody’s looking – thus, we get a secret glimpse at the real Bluto in his private office – dressed in an undershirt, his feet up on the desk clad only in stockings with holes in the toes, awkwardly chomping and gulping down a banana while reading a book entitled “Cops and Robbers”. Passing by below arrive the inevitable cash customers: Olive, dragging Popeye in to become a refined gentleman. Hearing the doorbell, Bluto is quick to revert to professional form, and with a few quick moves, has outfitted himself in tuxedo, fancy shoes and vest. “Entree”, he greets them at the door. “I already ‘et”, retorts Popeye, misunderstanding the professor’s lingo. “I want this to become a gentleman”, Olive tells Bluto. Bluto pulls out a monacle and closely observes Popeye. “Not so good…I wonder if that thing is human”, he mutters. Bluto’s firsr move is to throw Popeye’s pipe away into a nearby planter, where a daisy withers from the smell of its smoke. “Hey, what’s the idea? Do ya wanna spoil the flavor?”, complains Popeye. Bluto next demonstrates the proper way to greet a lady, making a low bow, taking Olive’s hand and kissing it. “Merci Bouquet”, responds Olive. Popeye shows his own idea of how to greet a lady – unceremoniously running up to her, shaking her hand vigorously, and complimenting her with “Well shiver me timbers! Yon’re the trimmest little craft I ever seen.” With disdain, Bluto escorts Olive away, and demonstrates how to escort her, arm in arm, up a flight of stairs. “She was always able to walk up herself before”, mumbles Popeye. Bluto directs Popeye to escort her back down. Popeye does so by seating Olive on the staircase railing, pushing her into a rapid downhill slide, then catching her on the other end. “Voulex voulez voo, and I do mean you”, says Popeye in a bow. Bluto’s third lesson demonstrates how to put on, then remove, a lady’s wrap. Seeing the garment go on and off so quickly, Popeye asks why’d he put it on her in the first place. Bluto asks Popeye to do it. Popeye tosses the coat into the air, then tickles Olive under the arms, causing her to raise her limbs high above her head, just in time to receive the falling coat. However, removing the wrap isn’t so easy, as Popeye yanks it down instead of up, flipping Olive’s feet out from under her in a backwards pratfall. Olive is disgusted, and Bluto grabs a book of etiquette, tosses it in Poeye’s face, and tells him, “Read this, and come back in ten years!”. Popeye crashes into the opposite wall, dislodging a painting from the wall. Its frame falls off, and the canvas wraps itself around Poeye’s head in the shape of a dunce cap.

Bluto’s old instincts now kick in, and, believing the field clear, he goes on the make for Olive, trying to steal kisses, then holding her in a stranglehold when she will not comply. Popeye returns, complaining, “Hey, that ain’t eticute!” Bluto politely excuses himself, to take Popeye into the next room, where he gives Popeye a final lesson – “Two’s company, and three’s a crowd”, socking him into a wall and wedging him to it with a piano. Popeye retracts his head into his shirt collar like a turtle, producing the old-standby spinach can, which not only frees him, but briefly transforms him into an outfit of top hat, tuxedo and tails. “And he thinks he’s a gentleman”, Popeye boasts. Returning to the room where Bluto is still strangling Olive, Popeye invites Bluto back to the other office, politely opening and closing the door for the bully. As the door closes, all hell breaks loose behind the wall , which vibrates vigorously from the commotion behind it, plaster chips falling everywhere. Bluto suddenly crashes through the wall, his outfit torn and in disarray. Popeye emerges, socking him into another wall, while politely saying, “Oh, pardon me”. He bows to Olive, while delivering a rear kick to Bluto’s face with his foot. “Two’s company, and you’re a crowd”, he tells Bluto, delivering more blows, while, one by one, he places a coat on Bluto, then his hat, scarf, and walking cane, then says he’s sorry to see Bluto going, as he socks Bluto off the tower. Bluto falls to street level, bouncing off the apartment building’s awning, and through the plate glass window of a shop on the other side of the street. There, in his battered outfit, he hangs in the store window between two mannequins, beneath a sign that says, “Suits for Hire. Fool your friends. Look Like a Gentleman. $1.00 down.” Back in the penthouse, Olive plants kisses on Popeye, as he falls back upon his old catchphrase, “I yam what I yam and that’s all wot I yam.”

Bluto’s old instincts now kick in, and, believing the field clear, he goes on the make for Olive, trying to steal kisses, then holding her in a stranglehold when she will not comply. Popeye returns, complaining, “Hey, that ain’t eticute!” Bluto politely excuses himself, to take Popeye into the next room, where he gives Popeye a final lesson – “Two’s company, and three’s a crowd”, socking him into a wall and wedging him to it with a piano. Popeye retracts his head into his shirt collar like a turtle, producing the old-standby spinach can, which not only frees him, but briefly transforms him into an outfit of top hat, tuxedo and tails. “And he thinks he’s a gentleman”, Popeye boasts. Returning to the room where Bluto is still strangling Olive, Popeye invites Bluto back to the other office, politely opening and closing the door for the bully. As the door closes, all hell breaks loose behind the wall , which vibrates vigorously from the commotion behind it, plaster chips falling everywhere. Bluto suddenly crashes through the wall, his outfit torn and in disarray. Popeye emerges, socking him into another wall, while politely saying, “Oh, pardon me”. He bows to Olive, while delivering a rear kick to Bluto’s face with his foot. “Two’s company, and you’re a crowd”, he tells Bluto, delivering more blows, while, one by one, he places a coat on Bluto, then his hat, scarf, and walking cane, then says he’s sorry to see Bluto going, as he socks Bluto off the tower. Bluto falls to street level, bouncing off the apartment building’s awning, and through the plate glass window of a shop on the other side of the street. There, in his battered outfit, he hangs in the store window between two mannequins, beneath a sign that says, “Suits for Hire. Fool your friends. Look Like a Gentleman. $1.00 down.” Back in the penthouse, Olive plants kisses on Popeye, as he falls back upon his old catchphrase, “I yam what I yam and that’s all wot I yam.”

Pencil animation from “The Foolish Bunny”

The Foolish Bunny (Mintz.Columbia, Color Rhapsody, 3/26/38, Art Davis, dir.) – An odd, moralistic cartoon, about a rabbit who refused to grow up – and never did. Amidst a classroom of eager young bunnies learning their ABC’s sleeps a full grown rabbit four times bihher than any of them, wearing spectacles, with a walking cane alongside his desk, and with a beard on his chin four feet long. His name is, inappropriately, Pee Wee, and he is the laughing stock of the class as teacher rouses him from his sleep with her yardstick, and he is utterly unable to recite his ABC’s. Teacher asks the students not to laugh at him, but to look at him as a life example of what not to become – a very old man, who still has to go to school, because he never took the time to learn his lessons. The scene flashes back to a typical day in Pee Wee’s youth, when he thought himself the brash, tough, cock-o’-the walk, utterly bored with school, where he insists he “don’t learn nothin’” anyway, and never has any fun. To liven things up for the day, he sneaks into class under his shirt a frog, vatious birds, a snapping turtle, and a full beehive. Pee Wee breaks in the schoolhouse door upon the last notes of the “Good Morning” song, performing a sort of Jolson bow and adding the lime, “Good Evening, Friends.” His lines are punctuated by streams of bees buzzing musically through the button flaps of his shirt. The frog in his pocket tries to hold onto the door frame of the school, but when pried loose snaps back toward Pee Wee, dislodging the bee hive, which lands om the professor’s head. Predictable chaos ensues as the bees swarm for several minutes, then the turtle and birds also get loose. One of the best visual shots has the swarm of bees convert in shape to the silhouette of a skulking man, to sneak up upon the professor. The professor never succeeds in restoring order, and Pee Wee just laughs at the carrying on – but is seen in time-lapse form aging into an old man while still laughing, the laughter dying away as he grows weaker and more feeble. And we return to the present, where again he is asleep at his desk, and another rap from the teacher’s yardstick proves once again that he’ll never learn, as he sputters out random letters in no particular order for the iris out.

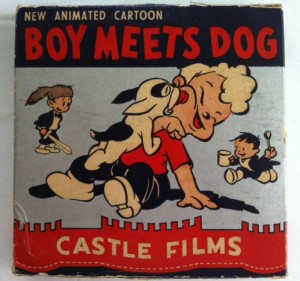

Boy Meets Dog (attributed by IMDB to 3/10/38 – Walter Lantz, dir.), was, as noted in a previous installment of this series, Walter Lantz’s attempt to do something in animated form with the Gene Byrnes comic, “Reg’lar Fellers”, an “Our Gang-ish” aggregation of kids and their various misadventures. It was a project doomed before it started, as it was a not-so-soft sell commercial film for Ipana Toothpaste, who, from some dispute or creative difference, seems to have pulled its backing from the film. The body of the episode has been discussed in the context of my “Courtroom Drama” series earlier this year, dealing with a trial of one of the boys’ father before a fairytale court in Pixieland, for cruelty to a puppy the boy has brought home in hopes of keeping as a pet. For purposes of this article, our only concern is an early sequence set in a country schoolhouse, serving as part of the “hard sell” of the episode. A purported lesson on hygiene is conducted by teacher in rhyme. “Chest out. Stomach in.” is the first order of the day. “A little brushing here and there is beneficial to the hair.” Then comes the strange pitch – a dental recommendation which I have never heard the ADA approve or utilize since – “With your fingers, not your thumbs, practice to massage your gums. First above and then beneath, takes good care of all your teeth.” How long, if at all, was this practice actually recommended? In one sense, it may suggest an intent to increase blood circulation. In actuality, if applied too hard, it probably caused kids to weaken the root structure in their jaws. Yet this alleged recommendation is woven throughout the cartoon, including at the trial, where the prosecutor accuses Dad, “He hires lawyers who are bums, and won’t even massage his gums.” In the shot removed from Castle Films home movie prints, Dad, upon awakening from the dream trial, sees a billboard outside for Ipana, encouraging gum massage with it for stronger gums. Now you not only have to rub with your fingers, but with toothpaste inside? How squishy! Plus, what was the amount of risk to a young child that the finger manipulation might force the toothpaste down his or her throat? The whole thing sounds pretty lame, and perhaps it’s best that the general public never saw this strange film in wide release after all.

Boy Meets Dog (attributed by IMDB to 3/10/38 – Walter Lantz, dir.), was, as noted in a previous installment of this series, Walter Lantz’s attempt to do something in animated form with the Gene Byrnes comic, “Reg’lar Fellers”, an “Our Gang-ish” aggregation of kids and their various misadventures. It was a project doomed before it started, as it was a not-so-soft sell commercial film for Ipana Toothpaste, who, from some dispute or creative difference, seems to have pulled its backing from the film. The body of the episode has been discussed in the context of my “Courtroom Drama” series earlier this year, dealing with a trial of one of the boys’ father before a fairytale court in Pixieland, for cruelty to a puppy the boy has brought home in hopes of keeping as a pet. For purposes of this article, our only concern is an early sequence set in a country schoolhouse, serving as part of the “hard sell” of the episode. A purported lesson on hygiene is conducted by teacher in rhyme. “Chest out. Stomach in.” is the first order of the day. “A little brushing here and there is beneficial to the hair.” Then comes the strange pitch – a dental recommendation which I have never heard the ADA approve or utilize since – “With your fingers, not your thumbs, practice to massage your gums. First above and then beneath, takes good care of all your teeth.” How long, if at all, was this practice actually recommended? In one sense, it may suggest an intent to increase blood circulation. In actuality, if applied too hard, it probably caused kids to weaken the root structure in their jaws. Yet this alleged recommendation is woven throughout the cartoon, including at the trial, where the prosecutor accuses Dad, “He hires lawyers who are bums, and won’t even massage his gums.” In the shot removed from Castle Films home movie prints, Dad, upon awakening from the dream trial, sees a billboard outside for Ipana, encouraging gum massage with it for stronger gums. Now you not only have to rub with your fingers, but with toothpaste inside? How squishy! Plus, what was the amount of risk to a young child that the finger manipulation might force the toothpaste down his or her throat? The whole thing sounds pretty lame, and perhaps it’s best that the general public never saw this strange film in wide release after all.

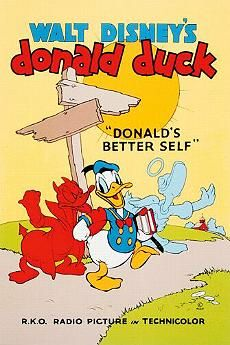

Donald’s Better Self (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 3/10/38 – Jack King, dir., Carl Barks, story), provides rare insight into the squawking duck’s youth as a schoolboy, and to the battle of good versus evil that goes on inside him. Oddly, Donald is not drawn any differently than we usually see him, his youth only suggested by the situations and by the decor in his bedroom (featuring posters for “Wild Duck’s Rodeo”, and a boxer known as “Kid Decoy”).

This was before the first animated appearance of Huey, Louie, and Dewey, so perhaps the concept of a model for a young duckling had not yet hit the animators and director, not to mention writer Carl Barks. The film begins on a typical morning, with Donald sound asleep in his bed. The alarm clock rings, but Donald tries to avoid it by rolling over the other way. As he rolls, a part of him stays behind – the transparent form of the “angel” Donald who lives inside him (a side of him that we don’t often see), complete with wings, halo, and heavenly robe). Angel, as we’ll call him, opens his eyes wide awake for a new day, throws back the bedcovers, and rises to shut off the alarm clock. “Wake up, Donald”, he says to the duck in a low, polite voice. “Wide awake”, he says, becoming more insistent as Donald does not stir. Then Angel resorts to giving the bed a shaking. “All right, all right”, mutters the sleepy dick, stretching and trying to get the fog out of his eyes. Managing only to sit up halfway, the duck falls back on the bed, turning in the opposite direction, revealing a version of himself with horns and dressed in a red devil suit. (Now here’s a guy we’ve seen often!) “Don’t be a sap”, he tells the duck, “let’s go back to sleep/” “Okay”, says Donald, quite easy to convince, and their heads hit the pillow again. “DONALD!” shouts the good one, shaking the duck up so that he jumps, landing hard and collapsing the bed, while Devil sneaks out the window, saying he’ll see him later. “You’ll be late for school”, says Angel. Muttering to himself, Donald struggles out of his nightshirt, with several items beyond his age bracket tumbling out from underneath, including a pair of dice, deck of cards, and a jackknife! (We knew Donald had a bad side, but this equipment seems to make him a candidate for juvenile delinquent.) It doesn’t take Donald long to get ready for the day, as he has slept with his sailor shirt on underneath, and waddling over to a wash basin and pitcher, we find he keeps no water for such unwanted task, but instead inside the pitcher is his sailor hat, which he “pours” onto his head to complete his ensemble. Angel hands Donald his strap full of schoolbooks, and takes the lead to escort Donald to school.

Angel marches down the counry road ahead of the duck, who kicks the dirt and complains to himself at having to do this all the time. He passes an RFD mailbox, which suddenly starts to raise and lower its red flag with the sound effects of a telegraph message. Donald is fascinated by the odd sight, and lingers behind as Angel continues on his way. Out from the box pops Devil, who points at Angel disappearing off in the distance oblivious to Donald’s absence, to indicate that the pest is gone. Producing two fishing poles from inside the box, Devil suggests, “C’mon, let’s go fishing.” Donald is again eagerly and easily swayed, taking one of the poles. “Last one down to the brook is a softie”, says Devil, and they are away. They are next seen lounging on the bank, their lines in the water, with Devil swapping spicy stories with Donald, who reacts with laughter, and the comment, “Hot stuff.” (No, Donald, that character would be owned by Harvey comics.) As Donald lays back against a log, the Devil makes his next move, producing from under his cape a corn-cob pipe. “How about a smoke, partner?”, he says temptingly, placing the pipe into Donald’s surprised bill. Unfamiliar with the equipment, Donald takes a smell of the contents inside, and examines it carefully. “Ya aren’t afraid, are ya?”, challenges the devil. “Me? Who’s afraid?”, answers Donald, hesitantly accepting the dare. Donald strikes a match he is offered on his tail – then realizes his tail is on fire in a small cloud of smoke. He smothers it in the dirt while Devil laughs himself silly. Sheepishly, Donald finally gets the pipe lit, and takes little sucks at it that produce embarrassing hooting noises. “Gimme that”, says the Devil, demonstrating how to smoke like a man and put hair on his chest (on a duck?) He inhales a big drag, blows a large cloud of smoke into Donald’s face, inhales about half of it back as second-hand smoke, then shoots the smoke out of his nostrils, with one last bit ejected as a spit. He challenges Donald to try again. Donald barely inhales, producing one small smoke puff and the spit. “You smoke like me grandmother”, the Devil taunts. “Take a real drag.” Donald finally sucks hard and long – but the smoke visibly disappears as a lump down his throat, as Donald accidentally swallows it. Devil slaps Donald on the back, telling him he’s doing fine, but Doald’s complexion, turning green, tells otherwise. The Devil keeps coaxing him to try more, but Donald’s hands tremble to even get the pipe back in his mouth. Finally, Donald is ready to collapse, and reaches out for a tree to lean on, but hallucinates that the tree dodges, then moves away from him entirely, leaving the duck to fall on the ground. “Why did I do it?”, moans the helpless duck.

Angel marches down the counry road ahead of the duck, who kicks the dirt and complains to himself at having to do this all the time. He passes an RFD mailbox, which suddenly starts to raise and lower its red flag with the sound effects of a telegraph message. Donald is fascinated by the odd sight, and lingers behind as Angel continues on his way. Out from the box pops Devil, who points at Angel disappearing off in the distance oblivious to Donald’s absence, to indicate that the pest is gone. Producing two fishing poles from inside the box, Devil suggests, “C’mon, let’s go fishing.” Donald is again eagerly and easily swayed, taking one of the poles. “Last one down to the brook is a softie”, says Devil, and they are away. They are next seen lounging on the bank, their lines in the water, with Devil swapping spicy stories with Donald, who reacts with laughter, and the comment, “Hot stuff.” (No, Donald, that character would be owned by Harvey comics.) As Donald lays back against a log, the Devil makes his next move, producing from under his cape a corn-cob pipe. “How about a smoke, partner?”, he says temptingly, placing the pipe into Donald’s surprised bill. Unfamiliar with the equipment, Donald takes a smell of the contents inside, and examines it carefully. “Ya aren’t afraid, are ya?”, challenges the devil. “Me? Who’s afraid?”, answers Donald, hesitantly accepting the dare. Donald strikes a match he is offered on his tail – then realizes his tail is on fire in a small cloud of smoke. He smothers it in the dirt while Devil laughs himself silly. Sheepishly, Donald finally gets the pipe lit, and takes little sucks at it that produce embarrassing hooting noises. “Gimme that”, says the Devil, demonstrating how to smoke like a man and put hair on his chest (on a duck?) He inhales a big drag, blows a large cloud of smoke into Donald’s face, inhales about half of it back as second-hand smoke, then shoots the smoke out of his nostrils, with one last bit ejected as a spit. He challenges Donald to try again. Donald barely inhales, producing one small smoke puff and the spit. “You smoke like me grandmother”, the Devil taunts. “Take a real drag.” Donald finally sucks hard and long – but the smoke visibly disappears as a lump down his throat, as Donald accidentally swallows it. Devil slaps Donald on the back, telling him he’s doing fine, but Doald’s complexion, turning green, tells otherwise. The Devil keeps coaxing him to try more, but Donald’s hands tremble to even get the pipe back in his mouth. Finally, Donald is ready to collapse, and reaches out for a tree to lean on, but hallucinates that the tree dodges, then moves away from him entirely, leaving the duck to fall on the ground. “Why did I do it?”, moans the helpless duck.

“Donald?” calls a distant voice, as we see a halo hovering over a stone wall, its owner soon appearing from behind it, as Angel returns in search of his absentee charge. He finds Devil doubled up in laughter at the prone Donald, satisfied that there’ll be no school for him today. “You! This is all your fault”, says Angel. “Don’t hoy me. Don’t hit me,” pleads cowardly Devil. “Have no fear. I do not intend to fight”, says prudish Angel. “Oh, so ya don’t fight”, says Devil, regaining his confidence, and rolling up his sleeves. “Look”, says Devil, pointing to Angel’s ankles, “Your petticoat’s showin’” Angel is faked into looking down, while Devil delivers an upper cut to Angel’s bill. “Now, now, can’t we talk this over?” says Angel. But Devil is far from in a talkative mood, as he steps on Angel’s foot, pulls Angel’s halo down around his arms, pulls up the hem of Angel’s robes to wrap him up like a ball, then boots him into the creek. Angel gets free of the upturned robe, finding his halo limp and soggy in the water. Wringing it out and replacing it upon his head, Angel announces, “That is the last straw”, and activates his angel wings for a quick takeoff, pond water emptying out of his shorts as he goes. Devil watches with trepidation, as Angel soars high, then comes down with both fists extended, rapidly rotating in circles from the elbows, so that Devil is caught as if between two wheels loaded with punch, then squeezed out at the top, landing in the dirt with a black eye and outfit battered. Angel soars even higher for another charge, and rapidly descends in a power dive. “I give up. I give ip”, shouts Devil. But too late, as Angel strikes a mighty blow, burrowing devil deep into the ground, the soil around him collapsing to fill in the hole, burying him in a mound of dirt with a funeral lily on top. “Whoopee! Hooray!”, shouts the revived Donald at Angel’s victory. But Angel only gives Donald an angry glare, then a glance downward at Donald’s stack of neglected school books Knowing there is now no easy path to avoid his responsibility, Donald picks up the books with embarrassment, then pats the Angel on the back, addressing him as “My pal.” Not to be fooled twice, Angel claps out the rhythm of the previous march, but stands his ground, instructing, “You first, Donald.” Donald is thus made to trot his way to school, with Angel close behing him – so close, that Angel disappears back into Donald’s body. But as the pathway to the schoolhouse appears on their right, Angel turns, but Donald keeps walking straight, right down the country road. Angel catches up to the tricky duck, and delivers him a good swift kick. “Uh oh”, says Donald, caught in the act, and performs a U-turn back to the path to school. Amgel follows again and disappears into Donald, but this time not completely, as Angel’s wings and halo remain visible upon the duck as he finally makes his way to class.

“Donald?” calls a distant voice, as we see a halo hovering over a stone wall, its owner soon appearing from behind it, as Angel returns in search of his absentee charge. He finds Devil doubled up in laughter at the prone Donald, satisfied that there’ll be no school for him today. “You! This is all your fault”, says Angel. “Don’t hoy me. Don’t hit me,” pleads cowardly Devil. “Have no fear. I do not intend to fight”, says prudish Angel. “Oh, so ya don’t fight”, says Devil, regaining his confidence, and rolling up his sleeves. “Look”, says Devil, pointing to Angel’s ankles, “Your petticoat’s showin’” Angel is faked into looking down, while Devil delivers an upper cut to Angel’s bill. “Now, now, can’t we talk this over?” says Angel. But Devil is far from in a talkative mood, as he steps on Angel’s foot, pulls Angel’s halo down around his arms, pulls up the hem of Angel’s robes to wrap him up like a ball, then boots him into the creek. Angel gets free of the upturned robe, finding his halo limp and soggy in the water. Wringing it out and replacing it upon his head, Angel announces, “That is the last straw”, and activates his angel wings for a quick takeoff, pond water emptying out of his shorts as he goes. Devil watches with trepidation, as Angel soars high, then comes down with both fists extended, rapidly rotating in circles from the elbows, so that Devil is caught as if between two wheels loaded with punch, then squeezed out at the top, landing in the dirt with a black eye and outfit battered. Angel soars even higher for another charge, and rapidly descends in a power dive. “I give up. I give ip”, shouts Devil. But too late, as Angel strikes a mighty blow, burrowing devil deep into the ground, the soil around him collapsing to fill in the hole, burying him in a mound of dirt with a funeral lily on top. “Whoopee! Hooray!”, shouts the revived Donald at Angel’s victory. But Angel only gives Donald an angry glare, then a glance downward at Donald’s stack of neglected school books Knowing there is now no easy path to avoid his responsibility, Donald picks up the books with embarrassment, then pats the Angel on the back, addressing him as “My pal.” Not to be fooled twice, Angel claps out the rhythm of the previous march, but stands his ground, instructing, “You first, Donald.” Donald is thus made to trot his way to school, with Angel close behing him – so close, that Angel disappears back into Donald’s body. But as the pathway to the schoolhouse appears on their right, Angel turns, but Donald keeps walking straight, right down the country road. Angel catches up to the tricky duck, and delivers him a good swift kick. “Uh oh”, says Donald, caught in the act, and performs a U-turn back to the path to school. Amgel follows again and disappears into Donald, but this time not completely, as Angel’s wings and halo remain visible upon the duck as he finally makes his way to class.

For a lively finish to today’s lesson, we have The Swing School (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 5/27/38 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Thomas Johnson, Frank Endres, dir,) – Betty runs a music school for animals, appropriately surrounded by a fence shaped like a music staff, with various notes for pickets and G clefs on the gates. Her students are all young animals, who sit at desks that convert with a flip to miniature pianos and organs. Late to class again is pup Pudgy, who tries to make up for it by offering a single flower to Betty – out of a bouquet actually intended for a cute female pup in the desk next to his. Betty begins the lesson with a little song at her own keyboard, instructing the students to continue the tune by taking individual choruses. All manner of species join in, including a giraffe who, having no voice, can’t even sing along, but merely rhythmically breathes the “la las” in a nearly silent whisper. Then comes Pudgy’s turn. While his keyboard work isn’t bad, Pudgy’s voice is entirely off key, and all he can muster is mournful howls in the most unmusical manner. “That will never do”, insists Betty, who, trying to maintain her patience, gives Pudgy several chances to redeem himself. But despite the additional attempts, Pudgy shows no improvement, and is the laughing stock of the class, shrinking in size in his seat from his mortification Betty pills at her hair, and tries to count to ten to control her temper, then orders Pudgy to sit in the corner, wearing the “Dope” cap. Betty resumes the lesson without all that “noise”, but the girl puppy takes pity on lonely Pudgy, and creeps up to him in the corner. “Poor Pudgy”, she commiserates, then plants a couple of kisses on Pudgy’s cheeks. Pudgy is rejuvenated by the kisses, and is suddenly full of life and pep. In what may be his only vocal appearance, Pudgy leaps down from the stool, removes the cap, and begins strutting his stuff around the stage, singing a vivacious scat refrain. The students are taken aback – but more taken with the rhythm, and quickly join in. Predicting a line which would later be used by Popeye in “Gym Jam” for Famous, Betty tells the class, “Don’t! Stop!”, but is intoxicated by the rhythm too, and changes it to “Don’t stop!”, joining in with a swaying dance. Pudgy’s performance provides a finale production number as the strutting pup gives his all, impressing his girlfriend, but even more Boop, who pulls out an ink stamper, and stamps across Pudgy’s tummy four stars, for the final iris out.