An unusually high number of contributions from Paramount mark this week’s offerings, with episodes spread across various of their series of theatrical shorts. Also included are a pair of memorable Warner Brothers classics, and a visit from the Disney studio featuring Minnie, Figaro, and starring pooch Pluto. While there is less spectacle on screen than in many prior surveys along our present trail, storms and changes of seasons continue to provide central plot points to support a variety of storylines – including a few which make an early appearance in time for appropriate viewing during the Halloween season.

Once again I have inadvertently left behind a George Pal Puppetoon, which I discuss here out of chronological sequence – Jasper In a Jam (Paramount, 10/18/46 – Duke Goldstone, dir.). By this late stage in the game, some changes were being made to the Jasper series. Perhaps running out of ideas for new con games to be pulled off by the Scarecrow, or perhaps from contractual unavailability of his voice (Rex Ingram), no appearance is made by the character in the last few installments of the series. Additionally, episodes such as this one would appear which were not personally directed by George Pal. Was George handing off his chores to others with eyes toward development of feature films? Hard to tell. However, his absence from nuts and bolts production may have been felt in some episodes such as this one, which seems to suffer from some difficulty in coming up with ideas sufficient to fill its allotted running time, several scenes having a feeling of being overly long, poky paced, and/or as included just for filler. The short is essentially a three-song music video, spotlighting performances by Charlie Barnet’s orchestra and Peggy Lee, with its running time pre-ordained by the length of the musical works. Plotline is thus of secondary importance, and the need for footage to match the music contributes to the “fill-time” feel of some of its animation. Several such “celebrity” vehicles were produced around this time, including “Rhapsody in Wood” (featuring Woody Herman) and “Date With Duke” (with Duke Ellington). While memorable for the performances of their stars, these films are not truly among the most creative or energetic works of their creator. Such is also the case here, though in the then-current climate of popularity of swing band music, these projects, if not masterpieces, were at least worth a try.

Once again I have inadvertently left behind a George Pal Puppetoon, which I discuss here out of chronological sequence – Jasper In a Jam (Paramount, 10/18/46 – Duke Goldstone, dir.). By this late stage in the game, some changes were being made to the Jasper series. Perhaps running out of ideas for new con games to be pulled off by the Scarecrow, or perhaps from contractual unavailability of his voice (Rex Ingram), no appearance is made by the character in the last few installments of the series. Additionally, episodes such as this one would appear which were not personally directed by George Pal. Was George handing off his chores to others with eyes toward development of feature films? Hard to tell. However, his absence from nuts and bolts production may have been felt in some episodes such as this one, which seems to suffer from some difficulty in coming up with ideas sufficient to fill its allotted running time, several scenes having a feeling of being overly long, poky paced, and/or as included just for filler. The short is essentially a three-song music video, spotlighting performances by Charlie Barnet’s orchestra and Peggy Lee, with its running time pre-ordained by the length of the musical works. Plotline is thus of secondary importance, and the need for footage to match the music contributes to the “fill-time” feel of some of its animation. Several such “celebrity” vehicles were produced around this time, including “Rhapsody in Wood” (featuring Woody Herman) and “Date With Duke” (with Duke Ellington). While memorable for the performances of their stars, these films are not truly among the most creative or energetic works of their creator. Such is also the case here, though in the then-current climate of popularity of swing band music, these projects, if not masterpieces, were at least worth a try.

Jasper, this time finding himself in the unexpected setting of an urban ghetto rather than in his mammy’s shack on the farm, follows the lead of other characters we have discussed in these articles, ducking into a most convenient doorway to get out of the rain. He bides his time watching electric commuter trains pass on an elevated railway above street level, his eyes transforming into reflections of the frames of train windows rapidly passing before his view. Suddenly, he leans back, to find the door of the darkened shop behind him is unlocked, creaking open. Jasper cautiously enters, finding himself in an old pawn shop, full of clocks, musical instruments, and assorted second-hand junk. As he approaches the sales counter in the center of the store, he suddenly reacts in terror, as he spies the drooping hand of an elderly man lifelessly hanging over the edge of the counter. Not in a mood to inquire further or have a closer look, Jasper runs for the door – but it has blown shut and somehow become locked. No amount of rattling will budge it. A clock begins to strike the hour, and Jasper counts the number of cuckoos it emits – which mysteriously reach 13! As he looks back at the contents of the shop, a transformation takes place, as the figurehead on a carved harp phase-dissolves to awaken to life. The puppetry for the harp (the best in the film) is simply a budget-saving excise to reuse puppet components already created for another film. She is the Lena Horne-style magic harp who had previously appeared in the Oscar-nominated “Jasper and the Beanstalk”. (Peggy Lee, who had appeared in the first film anonymously to provide the harp’s voice, returns again for such purpose, this time receiving her screen credit.) She sings a verse and a partial chorus of “Old Man Mose”, explaining her belief that Mose, the proprietor of the shop, is dead. As she reverts back to motionless wood, Jasper, now doubly-spooked at the confirmation of his suspicions about the lifeless form at the sales counter, shakes the front door twice as hard, but still cannot get it to yield. Now, the instruments of the shop take over, particularly a clarinet which slinks along with a flexible shaft like a snake, and begins a game of hide and seek with Jasper among the instruments and up stairways and shelves. Jasper somehow winds up with a trumpet, and begins a series of “call and response” riffs in answer to the licorice stick – allowing a showcase for a popular Charlie Barnet instrumental of the day, “Pompton Turnpike”. (An interesting sidelight is that the issued Victor recording was somewhat unique for its abrupt ending, sounding like it cut off the melody mid-line, referred to by some disc jockeys as “failing to drop the other shoe”. Yet, in this film performance, we hear, for perhaps the only time, a full resoluition of the melody line, and a final resounding coda note by the orchestra – proving that an ending had been written. So why the truncated version on the Victor record? It may have simply been for technical reasons – the full arrangement may have overrun its allowable running time to fit on disc. But the performance was so good that someone salvaged the date by clipping the melody short. Whatever the case, it was a recipe for success, as it proved to be one of Barnet’s biggest-selling sides.)

Jasper, this time finding himself in the unexpected setting of an urban ghetto rather than in his mammy’s shack on the farm, follows the lead of other characters we have discussed in these articles, ducking into a most convenient doorway to get out of the rain. He bides his time watching electric commuter trains pass on an elevated railway above street level, his eyes transforming into reflections of the frames of train windows rapidly passing before his view. Suddenly, he leans back, to find the door of the darkened shop behind him is unlocked, creaking open. Jasper cautiously enters, finding himself in an old pawn shop, full of clocks, musical instruments, and assorted second-hand junk. As he approaches the sales counter in the center of the store, he suddenly reacts in terror, as he spies the drooping hand of an elderly man lifelessly hanging over the edge of the counter. Not in a mood to inquire further or have a closer look, Jasper runs for the door – but it has blown shut and somehow become locked. No amount of rattling will budge it. A clock begins to strike the hour, and Jasper counts the number of cuckoos it emits – which mysteriously reach 13! As he looks back at the contents of the shop, a transformation takes place, as the figurehead on a carved harp phase-dissolves to awaken to life. The puppetry for the harp (the best in the film) is simply a budget-saving excise to reuse puppet components already created for another film. She is the Lena Horne-style magic harp who had previously appeared in the Oscar-nominated “Jasper and the Beanstalk”. (Peggy Lee, who had appeared in the first film anonymously to provide the harp’s voice, returns again for such purpose, this time receiving her screen credit.) She sings a verse and a partial chorus of “Old Man Mose”, explaining her belief that Mose, the proprietor of the shop, is dead. As she reverts back to motionless wood, Jasper, now doubly-spooked at the confirmation of his suspicions about the lifeless form at the sales counter, shakes the front door twice as hard, but still cannot get it to yield. Now, the instruments of the shop take over, particularly a clarinet which slinks along with a flexible shaft like a snake, and begins a game of hide and seek with Jasper among the instruments and up stairways and shelves. Jasper somehow winds up with a trumpet, and begins a series of “call and response” riffs in answer to the licorice stick – allowing a showcase for a popular Charlie Barnet instrumental of the day, “Pompton Turnpike”. (An interesting sidelight is that the issued Victor recording was somewhat unique for its abrupt ending, sounding like it cut off the melody mid-line, referred to by some disc jockeys as “failing to drop the other shoe”. Yet, in this film performance, we hear, for perhaps the only time, a full resoluition of the melody line, and a final resounding coda note by the orchestra – proving that an ending had been written. So why the truncated version on the Victor record? It may have simply been for technical reasons – the full arrangement may have overrun its allowable running time to fit on disc. But the performance was so good that someone salvaged the date by clipping the melody short. Whatever the case, it was a recipe for success, as it proved to be one of Barnet’s biggest-selling sides.)

All the jamming of Jasper with the other instruments, however, awakens a sleeping wooden cigar-store Indian, who goes on the warpath. As the instruments scurry away, a totem pole seizes Jasper with several pairs of hands. The wooden chief begins a war dance, while a face at the top of the totem pole plays saxophone (amazingly without hands to press any pad buttons on the sax to change notes). The tune played is Barnet’s first major record hit, “Cherokee”. The length of the number, however, bogs the ending of the film down, as the chief seems to take forever to begin lobbing tomahawks at Jasper, each one narrowly missing its small boy target. The whole thing is suddenly brought to a close by a policeman rattling the front door, aroused to investigate the source of the noise inside the shop. The chief gathers up his tomahawks and beats it, and all other instruments return to their original shelves and positions. The totem pole releases Jasper, and as the policeman gets the shop door open with a pass key, Jasper darts out past him in a blur, so fast he is unrecognizable to the cop, and away cleanly without the chance for an arrest or pursuit. The policeman calls inside to see if Mose is all right. Mose, it turns out, is not dead at all, but had merely dozed off to sleep, from lack of anything happening. He assures the officer it is just a quiet night, and nods off to sleep again.

All the jamming of Jasper with the other instruments, however, awakens a sleeping wooden cigar-store Indian, who goes on the warpath. As the instruments scurry away, a totem pole seizes Jasper with several pairs of hands. The wooden chief begins a war dance, while a face at the top of the totem pole plays saxophone (amazingly without hands to press any pad buttons on the sax to change notes). The tune played is Barnet’s first major record hit, “Cherokee”. The length of the number, however, bogs the ending of the film down, as the chief seems to take forever to begin lobbing tomahawks at Jasper, each one narrowly missing its small boy target. The whole thing is suddenly brought to a close by a policeman rattling the front door, aroused to investigate the source of the noise inside the shop. The chief gathers up his tomahawks and beats it, and all other instruments return to their original shelves and positions. The totem pole releases Jasper, and as the policeman gets the shop door open with a pass key, Jasper darts out past him in a blur, so fast he is unrecognizable to the cop, and away cleanly without the chance for an arrest or pursuit. The policeman calls inside to see if Mose is all right. Mose, it turns out, is not dead at all, but had merely dozed off to sleep, from lack of anything happening. He assures the officer it is just a quiet night, and nods off to sleep again.

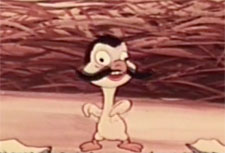

Snow Place Like Home (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 9/3/48 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Popeye and Olive spend a peaceful summer day off the shore of Miami, aboard a small rowboat bearing the name “Susie Q”. They are well provisioned for a day of sea and sunshine, each wearing bathing suits, with Olive eating multiple ice cream cones in a beach chair, Popeye reeling in fish after fish with a line casually tied to one toe, and a transistor radio plating the strains of “June in January”. The broadcast shifts to a weather bulletin for Miami and vicinity, forecasting “a slight blow”. What they get is a full-sized tornado. It picks the ship right up out of the water, and transports it clear across the continent, to the North Pole. There, it deposits the dizzily-spinning sailor and his girl, with the radio landing atop the pole itself, the song still continuing – except with the radio singer having developed a violent cold in his nose and a case of sneezes. Olive is partially submerged in a hole in the ice at the pole’s base, and shudders as she claims she is freezing. Popeye revives, and discovers Olive wasn’t exaggerating, as he extracts her from the water, encased in a block of ice. “What lovely ice you have”, he quips. Toting the frozen Olive on his back, Popeye spots a passing penguin (as usual, at the wrong pole), whose chest somehow operates as a neon sandwich-sign advertisement board, flashing an advertisement for Pierre’s Trading Post – furs bought and sold. Popeye follows the bird to the post, consisting of a department store-sized igloo with a colorful neon sign resembling the aurora borealis. Pierre, a moustached French-Canadian doubling today for Bluto, is engaged in a trading session with an Eskimo, paying him for furs with an ice cream cone and a fan. Popeye enters, requesting two furs and a sleigh. But Pierre’s attention zooms right past him, to a gaze at the frozen Olive. The fire in Pierre’s eyes is so intense, it instantly melts away the ice block, freeing the grateful Olive. Pierre is suddenly all attention to the frail female, supplying her with a shapely fur coat. Popeye reminds him that he needs a coat too. Anxious to get rid of the unwanted boyfriend, Pierre escorts Popeye to the “men’s department” – a cave behind the trading post, with a sign at the entrance reading “Cold Storage”. Pierre enters the cave, then returns, wrapping around Popeye’s neck the arms of what appears to be a full polar bear skin. “Nothing like a bear skin to cover your bare skin”, remarks Popeye. One little problem – the bear is still occupying his own skin, and, fully alive, puts the squeeze on the sailor. They disappear in a fight cloud into the cave, but a moment later, Popeye emerges, wearing the white fur, now cusom tailored to his dimensions – followed by the bear, who has been left without his coat and dressed only in Popeye’s bathing trunks, and stands shivering in the cold.

Snow Place Like Home (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 9/3/48 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Popeye and Olive spend a peaceful summer day off the shore of Miami, aboard a small rowboat bearing the name “Susie Q”. They are well provisioned for a day of sea and sunshine, each wearing bathing suits, with Olive eating multiple ice cream cones in a beach chair, Popeye reeling in fish after fish with a line casually tied to one toe, and a transistor radio plating the strains of “June in January”. The broadcast shifts to a weather bulletin for Miami and vicinity, forecasting “a slight blow”. What they get is a full-sized tornado. It picks the ship right up out of the water, and transports it clear across the continent, to the North Pole. There, it deposits the dizzily-spinning sailor and his girl, with the radio landing atop the pole itself, the song still continuing – except with the radio singer having developed a violent cold in his nose and a case of sneezes. Olive is partially submerged in a hole in the ice at the pole’s base, and shudders as she claims she is freezing. Popeye revives, and discovers Olive wasn’t exaggerating, as he extracts her from the water, encased in a block of ice. “What lovely ice you have”, he quips. Toting the frozen Olive on his back, Popeye spots a passing penguin (as usual, at the wrong pole), whose chest somehow operates as a neon sandwich-sign advertisement board, flashing an advertisement for Pierre’s Trading Post – furs bought and sold. Popeye follows the bird to the post, consisting of a department store-sized igloo with a colorful neon sign resembling the aurora borealis. Pierre, a moustached French-Canadian doubling today for Bluto, is engaged in a trading session with an Eskimo, paying him for furs with an ice cream cone and a fan. Popeye enters, requesting two furs and a sleigh. But Pierre’s attention zooms right past him, to a gaze at the frozen Olive. The fire in Pierre’s eyes is so intense, it instantly melts away the ice block, freeing the grateful Olive. Pierre is suddenly all attention to the frail female, supplying her with a shapely fur coat. Popeye reminds him that he needs a coat too. Anxious to get rid of the unwanted boyfriend, Pierre escorts Popeye to the “men’s department” – a cave behind the trading post, with a sign at the entrance reading “Cold Storage”. Pierre enters the cave, then returns, wrapping around Popeye’s neck the arms of what appears to be a full polar bear skin. “Nothing like a bear skin to cover your bare skin”, remarks Popeye. One little problem – the bear is still occupying his own skin, and, fully alive, puts the squeeze on the sailor. They disappear in a fight cloud into the cave, but a moment later, Popeye emerges, wearing the white fur, now cusom tailored to his dimensions – followed by the bear, who has been left without his coat and dressed only in Popeye’s bathing trunks, and stands shivering in the cold.

Inside the post, Olive freshens up with a make-up kit, while Pierre also makes himself presentable by trimming stubble off his chin with a metal file. Popeye surprises him with his appearance in the new fur coat, and asks for his sleigh. Pierre gives Popeye a sock, straight into a barrel of black grease, and out through the back wall of the store. Popeye emerges from the barrel, a black, slippery mess – and is quickly mistaken by a female seal to be a possible boyfriend. Popeye beats a retreat back to the post, with the seal in pursuit. Pierre is still engaged in flirtation with Olive, blowing heart-shaped bubbles with bubble gum, but Popeye arrives to intervene. The seal follows close behind, and provides a needed interference by balancing Pierre upon her nose. Popeye takes the opportunity for a quick shower inside a barrel to remove the grease, them positions the handles of several shovels around the rim of the barrel, signaling the seal to toss Pierre in. Pierre lands in the barrel, flipping the handles of the shovels so as to cause the shovel blades to beat him in the head from four sides. “Okay, you win”, says Pierre, pointing Popeye to what he claims is the best sleigh in the store. The conveyance seems to be folded into the wall like a Murphy bed, and as Popeye pulls downwards to lower the bladed base of the device, an unexpected set of metal teeth clamp down atop him like a king-sized mousetrap, trapping his head in a gap between them. A sign previously hidden on the wall where the device had stood now reveals it to be a “Super Bear Trap”. Not content with just imprisoning the sailor, Pierre ties a rope to the trap, the other end of which is fastened to a harpoon in a harpoon gun. He fires a shot through the store’s front door, the harpoon dragging the bear trap into the sky – and right into the mouth of a whale in the bay. “What a whale of a spot I’m in”, mutters Popeye. While Olive attempts to hide from Pierre inside the stovepipe of a pot-bellied stove, Popeye conveniently finds his spinach can, having somehow popped out of an unseen pocket and floating in the water inside the whale’s gullet. A little pipe suction, and Popeye gets his dose for the day, his muscle displaying a cutaway view of someone igniting dynamite with a plunger. Popeye skyrockets back to the post, making short work of Pierre, who is socked into the cold storage cave. Another struggle is heard inside, and after a moment, the polar bear emerges, wearing Pierre’s outfit, while Pierre follows, now wearing Popeye’s bathing suit, and turning blue in the cold. The film ends with Popeye and Olive in a sleigh ride back to their own kind of climate, pulled by the seal and the penguin, with the penguin’s advertising sign changed to read, “Miami or Bust.”

Inside the post, Olive freshens up with a make-up kit, while Pierre also makes himself presentable by trimming stubble off his chin with a metal file. Popeye surprises him with his appearance in the new fur coat, and asks for his sleigh. Pierre gives Popeye a sock, straight into a barrel of black grease, and out through the back wall of the store. Popeye emerges from the barrel, a black, slippery mess – and is quickly mistaken by a female seal to be a possible boyfriend. Popeye beats a retreat back to the post, with the seal in pursuit. Pierre is still engaged in flirtation with Olive, blowing heart-shaped bubbles with bubble gum, but Popeye arrives to intervene. The seal follows close behind, and provides a needed interference by balancing Pierre upon her nose. Popeye takes the opportunity for a quick shower inside a barrel to remove the grease, them positions the handles of several shovels around the rim of the barrel, signaling the seal to toss Pierre in. Pierre lands in the barrel, flipping the handles of the shovels so as to cause the shovel blades to beat him in the head from four sides. “Okay, you win”, says Pierre, pointing Popeye to what he claims is the best sleigh in the store. The conveyance seems to be folded into the wall like a Murphy bed, and as Popeye pulls downwards to lower the bladed base of the device, an unexpected set of metal teeth clamp down atop him like a king-sized mousetrap, trapping his head in a gap between them. A sign previously hidden on the wall where the device had stood now reveals it to be a “Super Bear Trap”. Not content with just imprisoning the sailor, Pierre ties a rope to the trap, the other end of which is fastened to a harpoon in a harpoon gun. He fires a shot through the store’s front door, the harpoon dragging the bear trap into the sky – and right into the mouth of a whale in the bay. “What a whale of a spot I’m in”, mutters Popeye. While Olive attempts to hide from Pierre inside the stovepipe of a pot-bellied stove, Popeye conveniently finds his spinach can, having somehow popped out of an unseen pocket and floating in the water inside the whale’s gullet. A little pipe suction, and Popeye gets his dose for the day, his muscle displaying a cutaway view of someone igniting dynamite with a plunger. Popeye skyrockets back to the post, making short work of Pierre, who is socked into the cold storage cave. Another struggle is heard inside, and after a moment, the polar bear emerges, wearing Pierre’s outfit, while Pierre follows, now wearing Popeye’s bathing suit, and turning blue in the cold. The film ends with Popeye and Olive in a sleigh ride back to their own kind of climate, pulled by the seal and the penguin, with the penguin’s advertising sign changed to read, “Miami or Bust.”

Hector’s Hectic Life (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon, 9/19/48 – Bill Tytla, dir.) – Nearly a straight steal of storyline from Rudolf Ising’s Chips Off the Old Block from MGM, merely changing its central characters from cats to dogs. There is an immediate problem with continuity between the title of this episode and its content – while the title refers to “Hector”, the dog in the film is repeatedly referred to by his owner as “Princie”. One can only guess the latter name suggested no catchy title, and the name for the cartoon was thought of at the last minute, without time to re-record or correct for the character references in the film itself. For now, we’ll call him Hector – a careless pooch with one spotted eye and ears of two different colors, who is in Dutch with his Scandanavian-speaking owner, a woman who is upset with his tendency to mess up the house. She shows him the snow piled high as far as the eye can see out the window, and warns him that any more messing up the place, and out in the snow he will go. Hector can see himself in the cold, begging for handouts with a tin cup. However, his owner leaves him a ray of hope, stating that if he is a good dog, maybe he will receive a nice present from Santa Claus. As she leaves the room, there is a knock outside the front door. Hector envisions the arrival of the jolly fat man, and whatever mystery package he may be bearing for Hector. Peeking out a doggie door, Hector finds a large picnic basket on the snowy doorstep. Taking it in from the falling snow, Hector grabs a bib and eating utensils, and prepares to dig in on what he presumes is a doggie feast inside the basket. To his dismay, the contents begin to bark at him. When he investigates, he finds three puppies – all with the same circle over one eye and two-color ears as himself. Parenthood has slapped him in the face.

Hector’s Hectic Life (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon, 9/19/48 – Bill Tytla, dir.) – Nearly a straight steal of storyline from Rudolf Ising’s Chips Off the Old Block from MGM, merely changing its central characters from cats to dogs. There is an immediate problem with continuity between the title of this episode and its content – while the title refers to “Hector”, the dog in the film is repeatedly referred to by his owner as “Princie”. One can only guess the latter name suggested no catchy title, and the name for the cartoon was thought of at the last minute, without time to re-record or correct for the character references in the film itself. For now, we’ll call him Hector – a careless pooch with one spotted eye and ears of two different colors, who is in Dutch with his Scandanavian-speaking owner, a woman who is upset with his tendency to mess up the house. She shows him the snow piled high as far as the eye can see out the window, and warns him that any more messing up the place, and out in the snow he will go. Hector can see himself in the cold, begging for handouts with a tin cup. However, his owner leaves him a ray of hope, stating that if he is a good dog, maybe he will receive a nice present from Santa Claus. As she leaves the room, there is a knock outside the front door. Hector envisions the arrival of the jolly fat man, and whatever mystery package he may be bearing for Hector. Peeking out a doggie door, Hector finds a large picnic basket on the snowy doorstep. Taking it in from the falling snow, Hector grabs a bib and eating utensils, and prepares to dig in on what he presumes is a doggie feast inside the basket. To his dismay, the contents begin to bark at him. When he investigates, he finds three puppies – all with the same circle over one eye and two-color ears as himself. Parenthood has slapped him in the face.

No sooner out of the basket than the pups start wreaking havoc, knocking over items, upsetting goldfish bowls, etc. All Hector can see is a one-way ticket out into the snow if he doesn’t do something about it quick. Several sequences are highly similar to the MGM source stated above, with the pups parading behind pop in mimic to his walk, and Hector trying to conceal them from his owner’s view in various rooms or objects. There is even a sequence that looks like it cross-pollenated out of Disney’s “Lend a Paw”, with Hector’s angel and devil consciences battling among themselves to determine whether the pups should be reascued from having been tossed out into the snow by Hector. But the pups actually don’t need saving, as they are already back and in the branches of the Christmas tree. Despite Hector’s efforts to repair their damage to the greenery and ornaments, a sneeze by the pups brings the whole tree crashing down. The owner is about to throw Hector out, but the pups rise from the debris to act in their father’s defense. Discovering the truth, the owner forgives all, and places each of the pups into respective stockings on the mantel, as surprises for the children who will be visiting the house in the morning. Everyone is happy – appropriate for a Merry Christmas.

No sooner out of the basket than the pups start wreaking havoc, knocking over items, upsetting goldfish bowls, etc. All Hector can see is a one-way ticket out into the snow if he doesn’t do something about it quick. Several sequences are highly similar to the MGM source stated above, with the pups parading behind pop in mimic to his walk, and Hector trying to conceal them from his owner’s view in various rooms or objects. There is even a sequence that looks like it cross-pollenated out of Disney’s “Lend a Paw”, with Hector’s angel and devil consciences battling among themselves to determine whether the pups should be reascued from having been tossed out into the snow by Hector. But the pups actually don’t need saving, as they are already back and in the branches of the Christmas tree. Despite Hector’s efforts to repair their damage to the greenery and ornaments, a sneeze by the pups brings the whole tree crashing down. The owner is about to throw Hector out, but the pups rise from the debris to act in their father’s defense. Discovering the truth, the owner forgives all, and places each of the pups into respective stockings on the mantel, as surprises for the children who will be visiting the house in the morning. Everyone is happy – appropriate for a Merry Christmas.

Riff Raffy Daffy (Warner, Porky Pig and Daffy Duck, 11/27/48 – Arthur Davis, dir.) – The coldest night in 64 years finds Daffy Duck (who has again forgotten to migrate) attempting to sleep in a public park. Though sleeping in a park might be a natural phenomenon for most birds, officer Porky Pig handles Daffy like a vagrant, repeatedly threatening Daffy to move along or be run in on charges. Daffy remarks that all he needs now is for it to start snowing – which it does, on cue, covering the park and Daffy in a blanket of snow. “I hadda open my big beak”, complains the duck to the audience. The answer to his dilemma, however, presents itself in a nearby department store window, where all the furnishings for a cozy living room are on display. The resourceful dick, without visual explanation, is next seen having already broken into and entered the store, kicking back in the comfort of a plush easy chair before a fireplace in the store window. Officer Porky passes on patrol, and spots the darnfool duck living his new life of ease. Porky begins shouting at the duck through the window. But the glass is so thick, we cannot hear the shouting from Daffy’s point of view inside. Daffy shouts back, but cannot be heard on Porky’s side. The two exchange silent epithets at each other until Daffy produces a glass cutter, slicing a hinged trap door into the glass. He emerges from the window briefly to exchange hostile, unintelligible shouts with Porky, then returns through the window, slamming the trap door, then pulling down a large window curtain to block Porky’s view, on which is written the word, “SCRAM!”

Riff Raffy Daffy (Warner, Porky Pig and Daffy Duck, 11/27/48 – Arthur Davis, dir.) – The coldest night in 64 years finds Daffy Duck (who has again forgotten to migrate) attempting to sleep in a public park. Though sleeping in a park might be a natural phenomenon for most birds, officer Porky Pig handles Daffy like a vagrant, repeatedly threatening Daffy to move along or be run in on charges. Daffy remarks that all he needs now is for it to start snowing – which it does, on cue, covering the park and Daffy in a blanket of snow. “I hadda open my big beak”, complains the duck to the audience. The answer to his dilemma, however, presents itself in a nearby department store window, where all the furnishings for a cozy living room are on display. The resourceful dick, without visual explanation, is next seen having already broken into and entered the store, kicking back in the comfort of a plush easy chair before a fireplace in the store window. Officer Porky passes on patrol, and spots the darnfool duck living his new life of ease. Porky begins shouting at the duck through the window. But the glass is so thick, we cannot hear the shouting from Daffy’s point of view inside. Daffy shouts back, but cannot be heard on Porky’s side. The two exchange silent epithets at each other until Daffy produces a glass cutter, slicing a hinged trap door into the glass. He emerges from the window briefly to exchange hostile, unintelligible shouts with Porky, then returns through the window, slamming the trap door, then pulling down a large window curtain to block Porky’s view, on which is written the word, “SCRAM!”

Porky appears inside the store, having entered with a skeleton key (shaped like a skull and crossbones). The inevitable chase ensues, with several clever gag sequences. While being carried inside a sack, Daffy grabs some fireworks from a store display, lighting the fuse to a large skyrocket inside the sack. Then Daffy slips out of the sack just as Porky reaches the door of an elevator. Appearing wearing the hat of an elevator operator, Daffy opens the door and ushers Porky inside – into an empty elevator shaft. He instructs Porky (who is walking on air in defiance of gravity) to face the front of the car, then shouts “Going up.” The rocket ignites, blasting Porky up the shaft and through the roof of the building in a blaze of sparks. A few moments later, Porky passes like a flaming meteor in reverse direction, crashing into the basement below. In the sporting goods department, Daffy takes time out from the chase to appear behind the sales counter, to give Porky a sales pitch about purchasing a shotgun, well-suited for duck hunting. Porky forks over a handful of cash, and Daffy supplies him with the rifle. With little regard for the danger he has just put himself into, Daffy dodges shotgun shells, as he happily counts up his cash on the run. “The things some ducks will do for money”, he declares. Finally, Daffy is cornered by Porky, and faces the open mouth of a lit cannon. He concedes defeat, and prepares to leave the store, but leads along behind him a pair of his “children”, whom he sadly informs that they are being thrown out into the street again. The “children” are in fact wind-up duck decoys with turning keys in their heads, which Daffy has obtained in the sporting goods department. Gullible Porky becomes tearful, and entirely forgiving, realizing the situation is different with the concern for the little ones. He relents, allowing Daffy and the ducklings to stay in the department store window as long as they like. As Porky leaves the store, Daffy waves to him from the window, while the wind-up ducks continue to clink-clank their way around the floor inside. Porky sympathetically smiles a half smile at the happy domestic picture, then trudges along on his beat, making the observation, “I k-know how it is when you have a family.” Without rational explanation, the camera pans down to Porky’s feet, to reveal following behind him a trio of wind-up pig decoys! Someone’s gotta have a little talk with Porky on the facts of life.

Porky appears inside the store, having entered with a skeleton key (shaped like a skull and crossbones). The inevitable chase ensues, with several clever gag sequences. While being carried inside a sack, Daffy grabs some fireworks from a store display, lighting the fuse to a large skyrocket inside the sack. Then Daffy slips out of the sack just as Porky reaches the door of an elevator. Appearing wearing the hat of an elevator operator, Daffy opens the door and ushers Porky inside – into an empty elevator shaft. He instructs Porky (who is walking on air in defiance of gravity) to face the front of the car, then shouts “Going up.” The rocket ignites, blasting Porky up the shaft and through the roof of the building in a blaze of sparks. A few moments later, Porky passes like a flaming meteor in reverse direction, crashing into the basement below. In the sporting goods department, Daffy takes time out from the chase to appear behind the sales counter, to give Porky a sales pitch about purchasing a shotgun, well-suited for duck hunting. Porky forks over a handful of cash, and Daffy supplies him with the rifle. With little regard for the danger he has just put himself into, Daffy dodges shotgun shells, as he happily counts up his cash on the run. “The things some ducks will do for money”, he declares. Finally, Daffy is cornered by Porky, and faces the open mouth of a lit cannon. He concedes defeat, and prepares to leave the store, but leads along behind him a pair of his “children”, whom he sadly informs that they are being thrown out into the street again. The “children” are in fact wind-up duck decoys with turning keys in their heads, which Daffy has obtained in the sporting goods department. Gullible Porky becomes tearful, and entirely forgiving, realizing the situation is different with the concern for the little ones. He relents, allowing Daffy and the ducklings to stay in the department store window as long as they like. As Porky leaves the store, Daffy waves to him from the window, while the wind-up ducks continue to clink-clank their way around the floor inside. Porky sympathetically smiles a half smile at the happy domestic picture, then trudges along on his beat, making the observation, “I k-know how it is when you have a family.” Without rational explanation, the camera pans down to Porky’s feet, to reveal following behind him a trio of wind-up pig decoys! Someone’s gotta have a little talk with Porky on the facts of life.

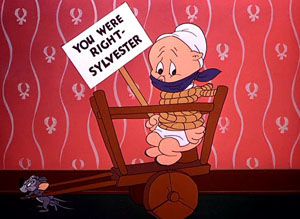

Scaredy Cat (Warner, Porky Pig, 12/19/48 – Charles M. (Chick) Jones, dir.) – The first of a trio of “fright night” episodes produced by Jones, pairing Porky with a nervous, speechless version of Sylvester. On a typically spooky night of rain and flashing thunder, the key is turned to the lock of a foreboding-looking estate. Two shadows extend across the floor of the entrance hallway, as the camera reveals a raincoated Porky Pig, followed by a tremulous, shuddering Sylvester. “Welcome to our new home”, says Porky, in a naive, cheerful tone. He informs the cat that they were very lucky to get this place, as it was the only one the realtor had. Sylvester is paying him little attention, glancing around the interior with trepidation. Then, the cat leaps with fright at the passing of a bat through the room, and jumps for safety inside Porky’s coat. Porky chastises the cat for his cowardice, and orders him to go into the kitchen to sleep, while Porky climbs the stairs for a well-needed rest in his own bedroom. Just as Porky begins to climb, Sylvester, unseen by Porky, changes direction from his path to the kitchen, and closely shadows Porky’s every step on tiptoe behind him. He follows so closely that Porky puts on his nightshirt and nightcap right over himself and the cat together, then settles down in bed with the cat still with him in the garments. “Goodnight, Sylvester”, says Porky, as he adjusts the cat’s face like a pillow under his head. “SYLVESTER!”, shouts Porky, as he finally becomes aware what is going on. The cat is tossed down the stairs, and told to get into the kitchen where he belongs. Landing in an umbrella rack at the foot of the stairs, Sylvester peers out from under an umbrella, to discover that there really is something to be afraid of within this house’s walls. A candlelight procession passes before him in the darkness. Two mice (dead ringers for Hubie and Bertie) carry the candles ahead of a third, who tows a small wooden wagon, carrying a cat all tied up. Behind the cart walks a fourth mouse, his face hooded in black, and carrying a headsman’s axe! Sylvester’s heart leaps into his throat, and he zooms back up the stairs and into Porky’s nightshirt again. When Porky demands an explanation, Sylvester duplicates in pantomime the spectacle he has just seen, adding the touch of placing a large vase over his head as he bends over, then mimicking the chop of an axe at neck line with his paw, causing the vase to fall like the head of the cat under the axe. “What ridiculous histrionom-y–m-mee–What ridiculous acting!”, stutters Porky. Sylvester is so distraught when Porky orders him downstairs again, that he proceeds to a desk drawer, pulls out a revolver, and points it at his own head to commit suicide. Porky wrestles the gun away from him, emptying it, and relents to let the “big baby” spend the night upstairs.

Scaredy Cat (Warner, Porky Pig, 12/19/48 – Charles M. (Chick) Jones, dir.) – The first of a trio of “fright night” episodes produced by Jones, pairing Porky with a nervous, speechless version of Sylvester. On a typically spooky night of rain and flashing thunder, the key is turned to the lock of a foreboding-looking estate. Two shadows extend across the floor of the entrance hallway, as the camera reveals a raincoated Porky Pig, followed by a tremulous, shuddering Sylvester. “Welcome to our new home”, says Porky, in a naive, cheerful tone. He informs the cat that they were very lucky to get this place, as it was the only one the realtor had. Sylvester is paying him little attention, glancing around the interior with trepidation. Then, the cat leaps with fright at the passing of a bat through the room, and jumps for safety inside Porky’s coat. Porky chastises the cat for his cowardice, and orders him to go into the kitchen to sleep, while Porky climbs the stairs for a well-needed rest in his own bedroom. Just as Porky begins to climb, Sylvester, unseen by Porky, changes direction from his path to the kitchen, and closely shadows Porky’s every step on tiptoe behind him. He follows so closely that Porky puts on his nightshirt and nightcap right over himself and the cat together, then settles down in bed with the cat still with him in the garments. “Goodnight, Sylvester”, says Porky, as he adjusts the cat’s face like a pillow under his head. “SYLVESTER!”, shouts Porky, as he finally becomes aware what is going on. The cat is tossed down the stairs, and told to get into the kitchen where he belongs. Landing in an umbrella rack at the foot of the stairs, Sylvester peers out from under an umbrella, to discover that there really is something to be afraid of within this house’s walls. A candlelight procession passes before him in the darkness. Two mice (dead ringers for Hubie and Bertie) carry the candles ahead of a third, who tows a small wooden wagon, carrying a cat all tied up. Behind the cart walks a fourth mouse, his face hooded in black, and carrying a headsman’s axe! Sylvester’s heart leaps into his throat, and he zooms back up the stairs and into Porky’s nightshirt again. When Porky demands an explanation, Sylvester duplicates in pantomime the spectacle he has just seen, adding the touch of placing a large vase over his head as he bends over, then mimicking the chop of an axe at neck line with his paw, causing the vase to fall like the head of the cat under the axe. “What ridiculous histrionom-y–m-mee–What ridiculous acting!”, stutters Porky. Sylvester is so distraught when Porky orders him downstairs again, that he proceeds to a desk drawer, pulls out a revolver, and points it at his own head to commit suicide. Porky wrestles the gun away from him, emptying it, and relents to let the “big baby” spend the night upstairs.

As Porky and Sylvester settle down under the bedcovers, the bed begins to move. The four homicidal mice are back, pushing the bed on rolling casters toward an open balcony window. They continue to push until the bed falls over the side of the house. Only a flagpole below saves them by breaking their fall. As the bed balances precariously atop the pole, Porky asks Sylvester to do something about the draft and close the window. Unaware where he is, Sylvester hops out of bed, defying gravity by walking on air, and walks over to a birdhouse on a nearby tree, shutting a miniature window in its wall. Meanwhile, the removal of his weight on the flagpole has caused the pole to catapult the bed back up into the bedroom, so that when Sylvester returns to the spot where he started, he is reclining on nothing, and falls helplessly to the ground below.

As Porky and Sylvester settle down under the bedcovers, the bed begins to move. The four homicidal mice are back, pushing the bed on rolling casters toward an open balcony window. They continue to push until the bed falls over the side of the house. Only a flagpole below saves them by breaking their fall. As the bed balances precariously atop the pole, Porky asks Sylvester to do something about the draft and close the window. Unaware where he is, Sylvester hops out of bed, defying gravity by walking on air, and walks over to a birdhouse on a nearby tree, shutting a miniature window in its wall. Meanwhile, the removal of his weight on the flagpole has caused the pole to catapult the bed back up into the bedroom, so that when Sylvester returns to the spot where he started, he is reclining on nothing, and falls helplessly to the ground below.

Sylvester reappears in Porky’s bedroom, with a large lump on his head. His eyes wide as he spots a panel opening above Porky’s bed, where the headsman mouse is pushing out a heavy anvil. Sylvester dashes to catch the anvil, mere inches above Porky’s noggin. Porky awakens, and seeing what Sylvester is holding above him, asks, “And w-what were you going to do with that anvil?” Porky disciplines the cat by dropping the anvil on Sylvester’s head, then drags him back down the stairs. As they descend, Sylvester spots the headsman mouse at the top of one of the staircase railings, positioning a bowling ball to roll down the banister, timed to intersect with Porky’s head as he reaches the foot of the stairs. Sylvester heroically takes the bullet, knocking Porky out of the way as he himself gets conked by the ball. Porky finds Sylvester lying on the floor, and believes the cat is merely working on his sympathies. Porky bends to pick Sylvester up, as the headsman mouse fires a gunshot that barely misses Porky. Unphased by the sound of the shot, Porky calmly remarks to the audience, “M-m-mice.” Placing unconscious Sylvester in a basket in the kitchen to sleep, Porky fails to notice various knives, daggers, and axes flying through the air in further efforts to do him in, and a spring-loaded axe that pops out of a trap door in the floor. An elevator panel causes Sylvester’s basket to descend into the basement, and as the clock ticks off a few hours, the basket slowly rises, to reveal Sylvester, so scared he has turned white. Semi-petrified and walking in the manner of a zombie, Sylvester returns to Porkys room, frightening the pig momentarily as if he has seen a ghost. When Sylvester is recognized, Porky demands he take off the makeup, and again drags him downstairs. Refusing to repeat what he has been through, the cat clings doggedly to a banister railing, until Porky states that he will go into the kitchen by himself, “just to prove what a yellow dog of a cowardly cat you really are.” He disappears inside the kitchen door, and there is a prolonged silence. Sylvester cautiously peers in, and views a repeat of the candlelight procession – but now Porky rides in the wagon, bound and gagged, in place of the cat. Porky holds up a sign in one tied hand, reading “You were right, Sylvester”.

Sylvester reappears in Porky’s bedroom, with a large lump on his head. His eyes wide as he spots a panel opening above Porky’s bed, where the headsman mouse is pushing out a heavy anvil. Sylvester dashes to catch the anvil, mere inches above Porky’s noggin. Porky awakens, and seeing what Sylvester is holding above him, asks, “And w-what were you going to do with that anvil?” Porky disciplines the cat by dropping the anvil on Sylvester’s head, then drags him back down the stairs. As they descend, Sylvester spots the headsman mouse at the top of one of the staircase railings, positioning a bowling ball to roll down the banister, timed to intersect with Porky’s head as he reaches the foot of the stairs. Sylvester heroically takes the bullet, knocking Porky out of the way as he himself gets conked by the ball. Porky finds Sylvester lying on the floor, and believes the cat is merely working on his sympathies. Porky bends to pick Sylvester up, as the headsman mouse fires a gunshot that barely misses Porky. Unphased by the sound of the shot, Porky calmly remarks to the audience, “M-m-mice.” Placing unconscious Sylvester in a basket in the kitchen to sleep, Porky fails to notice various knives, daggers, and axes flying through the air in further efforts to do him in, and a spring-loaded axe that pops out of a trap door in the floor. An elevator panel causes Sylvester’s basket to descend into the basement, and as the clock ticks off a few hours, the basket slowly rises, to reveal Sylvester, so scared he has turned white. Semi-petrified and walking in the manner of a zombie, Sylvester returns to Porkys room, frightening the pig momentarily as if he has seen a ghost. When Sylvester is recognized, Porky demands he take off the makeup, and again drags him downstairs. Refusing to repeat what he has been through, the cat clings doggedly to a banister railing, until Porky states that he will go into the kitchen by himself, “just to prove what a yellow dog of a cowardly cat you really are.” He disappears inside the kitchen door, and there is a prolonged silence. Sylvester cautiously peers in, and views a repeat of the candlelight procession – but now Porky rides in the wagon, bound and gagged, in place of the cat. Porky holds up a sign in one tied hand, reading “You were right, Sylvester”.

Sylvester darts out of the house, running a country mile up the road. He pauses to catch his breath, seated on the limb of a tree. In a puff of smoke appears, to Sylvester’s surprise, a small angel-conscience duplicate of himself, together with a signboard on an easel, and a pointer stick. The angel points to the signboard, on which appears the word “Coward.” Sylvester reacts sheepishly. An illustrated drawing appears, captioned “Remember?”, showing Porky feeding Sylvester when he was a kitten. A second illustration depicts the relative sizes of a cat and mouse. Sylvester begins to catch on, developing a sterner, more courageous look on his face. The signboard changes to “Now get in there and fight – fight – FIGHT!’ Sylvester’s chest swells like that of an ape-man, filled with fierce determination to save his master. He grabs as a weapon a limb off a tree – then thinks better of it, substituting instead as his weapon the whole tree trunk, which he uproots from the ground. The angel cat waves the checkered flag of an auto race to start him on his rescue mission. In a long shot, Sylvester zooms back to the house – then, the whole building erupts and bounces from the internal battle royale. Clamoring back toward the camera and past the angel emerges a stampede of frightened mice, who disappear up the road, never to return. Back at the house, a released Porky thanks Sylvester for saving his life – then reacts in horror as he spots the headsman mouse appearing from a cuckoo clock above Sylvester, carrying a large mallet. Porky tries to shout a warning, but Sylvester gets soundly bopped. Then, the mouse removes his headsman mask, revealing a face that is the rodent-equivalent of Fox Studios’ comic mock-news commentator Lew Lehr, who utters a paraphrase of Lehr’s catchphrase, “Pussy cats is the cwaziest people.”

Sylvester darts out of the house, running a country mile up the road. He pauses to catch his breath, seated on the limb of a tree. In a puff of smoke appears, to Sylvester’s surprise, a small angel-conscience duplicate of himself, together with a signboard on an easel, and a pointer stick. The angel points to the signboard, on which appears the word “Coward.” Sylvester reacts sheepishly. An illustrated drawing appears, captioned “Remember?”, showing Porky feeding Sylvester when he was a kitten. A second illustration depicts the relative sizes of a cat and mouse. Sylvester begins to catch on, developing a sterner, more courageous look on his face. The signboard changes to “Now get in there and fight – fight – FIGHT!’ Sylvester’s chest swells like that of an ape-man, filled with fierce determination to save his master. He grabs as a weapon a limb off a tree – then thinks better of it, substituting instead as his weapon the whole tree trunk, which he uproots from the ground. The angel cat waves the checkered flag of an auto race to start him on his rescue mission. In a long shot, Sylvester zooms back to the house – then, the whole building erupts and bounces from the internal battle royale. Clamoring back toward the camera and past the angel emerges a stampede of frightened mice, who disappear up the road, never to return. Back at the house, a released Porky thanks Sylvester for saving his life – then reacts in horror as he spots the headsman mouse appearing from a cuckoo clock above Sylvester, carrying a large mallet. Porky tries to shout a warning, but Sylvester gets soundly bopped. Then, the mouse removes his headsman mask, revealing a face that is the rodent-equivalent of Fox Studios’ comic mock-news commentator Lew Lehr, who utters a paraphrase of Lehr’s catchphrase, “Pussy cats is the cwaziest people.”

The Funshine State (Paramount/Famous, Screen Song, 1/7/49 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Another typical spot gag travelogue parody, shifting attention from the sunny spot of one coast to another. The Famous boys were of course much better acquainted with Florida than with California, given their stay there for several years at Max Fleischer’s southern studio. They bring up the subjects of Ponce De Leon and the Fountain of Youth – depicted as a soda fountain run by the local Indians), alligator wrestling (repeating the tummy-rubbing to put the wrestler to sleep gag from “Little Swee’Pea” and “Pitchin’ Woo at the Zoo”), and the singing bird tower (which acts as the prompter to the audience to follow the bouncing ball). Two weather gags appear – a narrator shows us a view of happy beachgoers, informing us that Florida is the only state in the union that has never seen snow – or has it, as snowflakes begin to fall upon the beach. The cause, however, is purely artificial – someone bent on lousing up the state’s reputation, flying over the beach in a plane named the “Spirit of California”, is feeding large ice blocks into a shredder to grind out fake snow flurries upon the tourist trade. The closing gag shows us palm trees gently waving goodbye with their fronds bobbing in the wind – then suddenly all three trees are snapped off at the roots by a wild hurricane, which picks up everything in sight into its whirlwind-force gusts, The last thing seen is a portion of the brick structure of the Miami Weather Bureau, with a silhouette visible through its frosted glass door of someone broadcasting a weather report. The door and the brickwork are blown away, revealing the weatherman with his desk and microphone completing his report, while the wind continues to obliterate all furniture and flooring from the room, and reduce the weatherman to his underwear and a bald head under his wig. The final words he utters: “This afternoon, there will be a moderate Southeasterly breeze…”

The Funshine State (Paramount/Famous, Screen Song, 1/7/49 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Another typical spot gag travelogue parody, shifting attention from the sunny spot of one coast to another. The Famous boys were of course much better acquainted with Florida than with California, given their stay there for several years at Max Fleischer’s southern studio. They bring up the subjects of Ponce De Leon and the Fountain of Youth – depicted as a soda fountain run by the local Indians), alligator wrestling (repeating the tummy-rubbing to put the wrestler to sleep gag from “Little Swee’Pea” and “Pitchin’ Woo at the Zoo”), and the singing bird tower (which acts as the prompter to the audience to follow the bouncing ball). Two weather gags appear – a narrator shows us a view of happy beachgoers, informing us that Florida is the only state in the union that has never seen snow – or has it, as snowflakes begin to fall upon the beach. The cause, however, is purely artificial – someone bent on lousing up the state’s reputation, flying over the beach in a plane named the “Spirit of California”, is feeding large ice blocks into a shredder to grind out fake snow flurries upon the tourist trade. The closing gag shows us palm trees gently waving goodbye with their fronds bobbing in the wind – then suddenly all three trees are snapped off at the roots by a wild hurricane, which picks up everything in sight into its whirlwind-force gusts, The last thing seen is a portion of the brick structure of the Miami Weather Bureau, with a silhouette visible through its frosted glass door of someone broadcasting a weather report. The door and the brickwork are blown away, revealing the weatherman with his desk and microphone completing his report, while the wind continues to obliterate all furniture and flooring from the room, and reduce the weatherman to his underwear and a bald head under his wig. The final words he utters: “This afternoon, there will be a moderate Southeasterly breeze…”

Honorable mention goes to Pluto’s Sweater (Disney, RKO, Pluto, 4/29/49 – Charles Nichols, dir.), though it contains no actual on-screen weather action. Conscientious Minnie Mouse is knitting a small purple woolen garment, with four sleeves, to keep someone warm during the winter cold. Pluto laughs to Figaro, envisioning how awful and ill-fitting the garment will look on Minnie (is this the origin of the holiday tradition of the ugly sweater?), but Figaro cockily advises Pluto in pantomime that the sweater is intended for him. Figaro takes great delight in flushing out Pluto from his hiding place, when the dog attempts to make himself scarce rather than making a fashion statement. Take it from a former pet owner – dogs do not often take well to the idea of acquiring a human wardrobe. Pluto is no exception, as Minnie engages in a wrestling match with the canine to get him into the garment, while Figaro doubles up in laughter. As a finishing touch, Figaro twangs Pluto’s tail with one claw, pulling it out through a special small hole Minnie has included at the rear of the garment. Pluto passes a mirror, and is mortified by his appearance – then becomes even more self-conscious when Minnie suggests he go outside. The suggestion turns to an insistence, as Pluto struggles to hide under the furniture again, and gets repeatedly thrown out of his doggie door onto the front porch. As Pluto feared, along cones Butch and several other neighborhood dogs – and Pluto is instantly the laughing stock of the block. Pluto slinks behind the shrubbery, then waits his chance until no one is looking to creep across the street to an open park area, in search pf a place where he can address his intolerable garment and attempt to remove it. To a canine mind, this is not an easy task. Pluto ties himself in woolen knots as he struggles to free his limbs from the sweater’s cuffs. After several exercises in contortion, Pluto somehow manages to get his four limbs free, but with the body of the sweater still surrounding his waistline. Thinking it’s at least an improvement, Pluto trots forward, hoping the garment will no longer be an interference. But the arms of the sweater flap out and fall to the ground, doubling Pluto’s every step into a march of eight legs, with the sound effect of the drilling footsteps of a platoon. Pluto wrestles with the wool again, and finds the wool prone to stretching, resulting in the hound becoming completely enveloped again inside the overflowing garment, much resembling a gift-wrapped bundle. Spotting a small twig rooted in the ground, Pluto tries a desperation move, wrapping one of the sweater’s arms around the twig, then pulling with all his might in the opposite direction, over a patch of snow-covered ground. The loop around the twig gives way, ad Pluto is snapped in the rear, causing him to tumble into a deep water puddle amid the snowbanks. He emerges from the puddle completely hidden within the garment, which has also taken on water inside, inflating its dimensions so that its shape resembles a spouting purple whale. Water on wool can only result in more trouble – and the garment begins to shrink drastically, tightening and tightening upon Pluto, until it encases and covers only his head, his ears filling two of the sleeves. Pluto repositions the miniaturized neck hole with his ears to serve as a peephole for his eyes, rendering the sweater a sort of ski mask, then heads back to Minnie’s house. Minnie is spending the afternoon reading – a pulp fiction mystery entitled “The Hooded Monster”. Pluto’s masked face appears over the arm of her easy chair – and sends the mouse into a scream of terror, frightening her up upon the opposite armrest. As Pluto utters a muffled whimper, she finally realizes that it is only the dog – but that sweater! She pries the shrunken garment off Pluto’s face, then bursts out crying, using the tiny garment as a handkerchief to catch her own tears, as she bemoans that it is ruined, after all her hard work. Pluto feels sad for Minnie, but notices Figaro across the room, still giving Pluto the horselaugh. Eyeing Figaro’s size, Pluto gets an idea, and points Minnie’s attention to the cat by gestures with his ears. Minnie catches on, and begins to smile, sniffing back her tears as she advances toward Figaro. The camera holds on Pluto, as we hear the offscreen sounds of cat howls and another wrestling match. It is now Pluto’s turn to have the last laugh, as the camera reveals Figaro, tightly encased in the miniature sweater, who hisses and yowls his fiercest yowl of displeasure at the camera, for the iris out.

Honorable mention goes to Pluto’s Sweater (Disney, RKO, Pluto, 4/29/49 – Charles Nichols, dir.), though it contains no actual on-screen weather action. Conscientious Minnie Mouse is knitting a small purple woolen garment, with four sleeves, to keep someone warm during the winter cold. Pluto laughs to Figaro, envisioning how awful and ill-fitting the garment will look on Minnie (is this the origin of the holiday tradition of the ugly sweater?), but Figaro cockily advises Pluto in pantomime that the sweater is intended for him. Figaro takes great delight in flushing out Pluto from his hiding place, when the dog attempts to make himself scarce rather than making a fashion statement. Take it from a former pet owner – dogs do not often take well to the idea of acquiring a human wardrobe. Pluto is no exception, as Minnie engages in a wrestling match with the canine to get him into the garment, while Figaro doubles up in laughter. As a finishing touch, Figaro twangs Pluto’s tail with one claw, pulling it out through a special small hole Minnie has included at the rear of the garment. Pluto passes a mirror, and is mortified by his appearance – then becomes even more self-conscious when Minnie suggests he go outside. The suggestion turns to an insistence, as Pluto struggles to hide under the furniture again, and gets repeatedly thrown out of his doggie door onto the front porch. As Pluto feared, along cones Butch and several other neighborhood dogs – and Pluto is instantly the laughing stock of the block. Pluto slinks behind the shrubbery, then waits his chance until no one is looking to creep across the street to an open park area, in search pf a place where he can address his intolerable garment and attempt to remove it. To a canine mind, this is not an easy task. Pluto ties himself in woolen knots as he struggles to free his limbs from the sweater’s cuffs. After several exercises in contortion, Pluto somehow manages to get his four limbs free, but with the body of the sweater still surrounding his waistline. Thinking it’s at least an improvement, Pluto trots forward, hoping the garment will no longer be an interference. But the arms of the sweater flap out and fall to the ground, doubling Pluto’s every step into a march of eight legs, with the sound effect of the drilling footsteps of a platoon. Pluto wrestles with the wool again, and finds the wool prone to stretching, resulting in the hound becoming completely enveloped again inside the overflowing garment, much resembling a gift-wrapped bundle. Spotting a small twig rooted in the ground, Pluto tries a desperation move, wrapping one of the sweater’s arms around the twig, then pulling with all his might in the opposite direction, over a patch of snow-covered ground. The loop around the twig gives way, ad Pluto is snapped in the rear, causing him to tumble into a deep water puddle amid the snowbanks. He emerges from the puddle completely hidden within the garment, which has also taken on water inside, inflating its dimensions so that its shape resembles a spouting purple whale. Water on wool can only result in more trouble – and the garment begins to shrink drastically, tightening and tightening upon Pluto, until it encases and covers only his head, his ears filling two of the sleeves. Pluto repositions the miniaturized neck hole with his ears to serve as a peephole for his eyes, rendering the sweater a sort of ski mask, then heads back to Minnie’s house. Minnie is spending the afternoon reading – a pulp fiction mystery entitled “The Hooded Monster”. Pluto’s masked face appears over the arm of her easy chair – and sends the mouse into a scream of terror, frightening her up upon the opposite armrest. As Pluto utters a muffled whimper, she finally realizes that it is only the dog – but that sweater! She pries the shrunken garment off Pluto’s face, then bursts out crying, using the tiny garment as a handkerchief to catch her own tears, as she bemoans that it is ruined, after all her hard work. Pluto feels sad for Minnie, but notices Figaro across the room, still giving Pluto the horselaugh. Eyeing Figaro’s size, Pluto gets an idea, and points Minnie’s attention to the cat by gestures with his ears. Minnie catches on, and begins to smile, sniffing back her tears as she advances toward Figaro. The camera holds on Pluto, as we hear the offscreen sounds of cat howls and another wrestling match. It is now Pluto’s turn to have the last laugh, as the camera reveals Figaro, tightly encased in the miniature sweater, who hisses and yowls his fiercest yowl of displeasure at the camera, for the iris out.

Spring Song (Paramount/Famous, Screen Song, 6/24/49 – I Sparber, dir.) – The usual kind of thing we’ve seen before in Ub Iwerks’ “Summertime” and Oswald Rabbit’s “Springtime Serenade” – the routine when winter thaws out and spring begins. Here, above a snow-covered landscape with a prominent snowman in the middle, the sum slumbers in a cloudy bed high above the earth. Having had little reason to see the land for months, the sun is not even a golden yellow, but is depicted in a color of pale blue, like a light bulb that has been turned off. An alarm wristwatch on a concealed arm rings, its dial depicting only seasons, with the single hand pointing to springtime. The sun seems to wake up grumpy, and rolls over in bed as if about to go back to sleep. Instead, old Sol has merely been showing us its “dark side”, and as it turns, a golden half with a cheery smile reveals itself to view. The snowman below is quickly melted, and out of its remaining top hat leaps the satyr Pan, ushering in Spring with his panflute tune. A tree’s limbs open like an umbrella and sprout a thick canopy of leaves above. A turtle emerges from the thawing waters of an icy stream, removing winter hat, scarf, sweaters from inside his shell, and throwing out a pot-bellied stove he has kept inside his shell all winter, replacing the ensemble with a sporty sun hat. Other animals travel to a fur storage facility, trading in their natural fur coats for lightweight leisure outfits of human clothing. A hibernating bear is awakened by a Rube Goldberg contraption powered by the first rays of sunshine through a magnifying glass, leading at the end of the chain reaction of objects to a wheel with feathers attached thereon, turning to tickle the bear’s feet. Claiming Spring is wonderful, the bear rises, washes his face, goes through a brisk morning routine, then merely jumps back in bed again for more snoring (a gag that can be traced back to Fleischer’s early Talkartoon, “Radio Riot”). A finale sequence has angle worms alerted by a floral air-raid waning system of the return of birds back North. A buzzard-like bird chases one of the worms (both characters appeared again in the 1950’s Noveltoon, “The Oily Bird”) into his hole. The bird dives at him so forcefully, his long beak disappears entirely into the hole. By the time the bird extricates himself, the worm has ensured that he will cause no more trouble, by sealing his beak closed with a large padlock.

Spring Song (Paramount/Famous, Screen Song, 6/24/49 – I Sparber, dir.) – The usual kind of thing we’ve seen before in Ub Iwerks’ “Summertime” and Oswald Rabbit’s “Springtime Serenade” – the routine when winter thaws out and spring begins. Here, above a snow-covered landscape with a prominent snowman in the middle, the sum slumbers in a cloudy bed high above the earth. Having had little reason to see the land for months, the sun is not even a golden yellow, but is depicted in a color of pale blue, like a light bulb that has been turned off. An alarm wristwatch on a concealed arm rings, its dial depicting only seasons, with the single hand pointing to springtime. The sun seems to wake up grumpy, and rolls over in bed as if about to go back to sleep. Instead, old Sol has merely been showing us its “dark side”, and as it turns, a golden half with a cheery smile reveals itself to view. The snowman below is quickly melted, and out of its remaining top hat leaps the satyr Pan, ushering in Spring with his panflute tune. A tree’s limbs open like an umbrella and sprout a thick canopy of leaves above. A turtle emerges from the thawing waters of an icy stream, removing winter hat, scarf, sweaters from inside his shell, and throwing out a pot-bellied stove he has kept inside his shell all winter, replacing the ensemble with a sporty sun hat. Other animals travel to a fur storage facility, trading in their natural fur coats for lightweight leisure outfits of human clothing. A hibernating bear is awakened by a Rube Goldberg contraption powered by the first rays of sunshine through a magnifying glass, leading at the end of the chain reaction of objects to a wheel with feathers attached thereon, turning to tickle the bear’s feet. Claiming Spring is wonderful, the bear rises, washes his face, goes through a brisk morning routine, then merely jumps back in bed again for more snoring (a gag that can be traced back to Fleischer’s early Talkartoon, “Radio Riot”). A finale sequence has angle worms alerted by a floral air-raid waning system of the return of birds back North. A buzzard-like bird chases one of the worms (both characters appeared again in the 1950’s Noveltoon, “The Oily Bird”) into his hole. The bird dives at him so forcefully, his long beak disappears entirely into the hole. By the time the bird extricates himself, the worm has ensured that he will cause no more trouble, by sealing his beak closed with a large padlock.

The barometer stays shifty, into 1950, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Chuck Jones didn’t make many Sylvester cartoons, but I think the cat showed a lot more personality under Jones’s direction than he ever did with Freleng or McKimson.

There’s a Season 2 episode of “Lost in Space” called “The Astral Traveler”, in which Will Robinson enters a trans-dimensional portal and finds himself in a haunted castle in Scotland. At one point Will sees a ghostly procession consisting of two guards, a condemned prisoner, and a hooded executioner. That scene always reminds me of the mice in “Scaredy Cat”.

“Hector’s Hectic Life” raises the question: who is the mother of Hector’s pups? If they were the result of a dalliance with a female, then he shouldn’t be bothered by his owner’s threats to put him outside; he would surely welcome the prospect of another liaison, cold weather notwithstanding. On the other hand (paw), maybe the female came to Hector’s house, entering through the doggy door as some sort of outcall service. That, at least, would explain how she knew where he lived. But in that case Hector would have had some experience in hiding unfamiliar dogs from his owner and therefore been more adept at doing so. Come to think of it, why do the kittens in “Chips off the Old Block” all have cauliflower ears like their father? Is that hereditary? Ow, my head hurts….

It only just now occurred to me that “Snow Place Like Home” is a (probably unintended) subliminal comment on the studio itself, at one time based in Miami but then yanked back up north by a tornado called Paramount.

But I’ve always wondered how much “Riff Raffy Daffy” influenced “Evening Primrose,” a bizarre 1966 TV musical (songs by Stephen Sondheim) about a poet who decides to withdraw from the world by taking up residence in a department store, only to find a secret society already living there.

Your comparison of “Riff Raffy Daffy” to “Evening Primrose” is quite perceptive. But in reality, the influence of one production upon the other was likely in the opposite direction. “Primrose”, in a non-musical form, premiered as a radio drama on CBS’s anthology series, “Escape” on 11/5/47 – approximately one year before the cartoon! So it was Daffy who must have been trying to join that secret society.

Mighty Mouse displays his vulnerability to poison sprays again in another Halloween cartoon, “The Witch’s Cat” (Terrytoons, 15/9/48 — Mannie Davis, dir.). As the mice are celebrating the holiday, a witch arrives via broomstick to gather them up and feed them to her dim-witted cat. Mighty Mouse speeds to the rescue, but the witch spritzes him with a poison brew that knocks him unconscious. He floats away in a delirium while the witch and her cat trap the mice inside a giant Jack-o’-lantern. But when our hero passes beneath a rain cloud, the falling rain revives him, and off he goes to save the day. It’s only a brief scene of precipitation, but at least it’s germane to the plot this time.

Such a shame that Art Davis’ tenure as a director was so short. In my opinion, his Daffy cartoons were the best outside of Clampett’s.