World War II was coming to an end – ushering in an era of perceived prosperity (except for those countries bombed out or conquered) and an end to wartime rationing. Americans probably considered themselves as living high off the hog – and no doubt many started to look like one in the process. Is it any wonder that during the next half-decade, the concentration of the American cartoon appears to have turned decidedly away from efforts to reduce, and instead produced another cluster of films displaying bloated bellies and endless appetites? Only nearing the end of the decade does the fitness craze begin to reappear, some flabby few probably beginning to realize the error of their ways, and paying the price for a celebratory few years of over-indulgence.

It’s hard to single out an instance for consideration of one of Hollywood’s champion eaters, the ever-ravenous Woody Woodpecker. So many of his films revolve around simple to elaborate schemes to plunder someone else’s pantry. That overeating became a recurring theme and occupational hazard of the series. Yet, Woody was one of those rare birds who maintained a top-flight metabolism, and never seemed to gain a pound. Perhaps all that running from Wally Walrus, Mrs. Meany and the like was all the workout Woody needed to stay in shape. At any rate, at least one representative sample of his dirty work should be included in this series. In view of its appropriate title, I choose Chew Chew Baby (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 2/5/45 – James Culhane, dir.)

Woody is a resident of the “3-Square Boarding House”- but not destined to be for long, if the proprietor, Wally Walrus, has anything to say about it. “All you do is eat and eat, but you never pay a dollar”, Wally is heard to complain, while pursuing his feathered prey through the halls of the premises. Woody receives the boot-end of Wally’s flipper, landing in a trash can outside the abode. Wally warns him never to come back, and adds as if it were the nastiest swear word he can muster (at least in front of the censors), “You moocher!” Woody grumbles at the nerve of throwing a guy out on an empty stomach, and picks up a stray page of a tossed-away newspaper, in search of a new residence. In the process, he stumbles upon am unexpected advertisement, placed by none other than Wally himself. “Lonesome Bachelor wishes to meet refined lady – object matrimony. Can offer fine home and lots of good wholesome food. Phone wally Walrus, Asthma-4343.” Any guesses what’s running through Woody’s mind? A phone call later, he is introducing himself in an effeminate voice as “Clementine”. “Young lady, are you refined?”, asks Wally. “Refined? I’m 110 octane!” replies Woody. Wally is so bowled over, he drops the phone into his pot of boiling soup.

Woody is a resident of the “3-Square Boarding House”- but not destined to be for long, if the proprietor, Wally Walrus, has anything to say about it. “All you do is eat and eat, but you never pay a dollar”, Wally is heard to complain, while pursuing his feathered prey through the halls of the premises. Woody receives the boot-end of Wally’s flipper, landing in a trash can outside the abode. Wally warns him never to come back, and adds as if it were the nastiest swear word he can muster (at least in front of the censors), “You moocher!” Woody grumbles at the nerve of throwing a guy out on an empty stomach, and picks up a stray page of a tossed-away newspaper, in search of a new residence. In the process, he stumbles upon am unexpected advertisement, placed by none other than Wally himself. “Lonesome Bachelor wishes to meet refined lady – object matrimony. Can offer fine home and lots of good wholesome food. Phone wally Walrus, Asthma-4343.” Any guesses what’s running through Woody’s mind? A phone call later, he is introducing himself in an effeminate voice as “Clementine”. “Young lady, are you refined?”, asks Wally. “Refined? I’m 110 octane!” replies Woody. Wally is so bowled over, he drops the phone into his pot of boiling soup.

A meeting is arranged. Wally spruces up in his best dinner jacket, and liberally spritzes himself with cologne – even spraying his intended’s name like skywriting in the perfume fumes. Of course, he has to mend his ways a little – by ripping down a wall-load of pin-up photos. Most importantly, he wheels out a large cart of home-cooked delectables for the evening repast. Woody arrives, in drag, complete with high heels, nylons, and a blonde wig. As they exchange first glances, Wally envisions marching her down the aisle. Woody, on the other hand, sees Waally in his mind’s eye as a tub of lard. While Wally skyrockets around the room in excitement, Woody begins to chow down in ernest, polishing off sandwich after sandwich, and devouring an entire ham by merely rotating it in his beek until it is trimmed down to the bone. Walls seats himself on the sofa next to him, and reaches for Woody’s hand to give an affectionate kiss. Woody never misses a beat in eating, offering to Wally a gloved hand, attached to a mile of fake blue hose, which droops onto the floor as Wally continues to kiss up the fake “arm”. Woody calls him a naughty boy, and some playful pushing knocks the walrus across the room – only making the sap more lovesick. Wally hops back on the sofa – but his weight bounces Woody into the air, flipping his wig. Woody falls back to earth, bouncing Wally skyward. Woody swiftly plants a fork in the sofa cushions, tines upward. YEOW! Just for fun, before Wally can plummet again, Woody plants a traffic signal in the living room, making Wally “Stop” and “Go” in mid-fall.

A meeting is arranged. Wally spruces up in his best dinner jacket, and liberally spritzes himself with cologne – even spraying his intended’s name like skywriting in the perfume fumes. Of course, he has to mend his ways a little – by ripping down a wall-load of pin-up photos. Most importantly, he wheels out a large cart of home-cooked delectables for the evening repast. Woody arrives, in drag, complete with high heels, nylons, and a blonde wig. As they exchange first glances, Wally envisions marching her down the aisle. Woody, on the other hand, sees Waally in his mind’s eye as a tub of lard. While Wally skyrockets around the room in excitement, Woody begins to chow down in ernest, polishing off sandwich after sandwich, and devouring an entire ham by merely rotating it in his beek until it is trimmed down to the bone. Walls seats himself on the sofa next to him, and reaches for Woody’s hand to give an affectionate kiss. Woody never misses a beat in eating, offering to Wally a gloved hand, attached to a mile of fake blue hose, which droops onto the floor as Wally continues to kiss up the fake “arm”. Woody calls him a naughty boy, and some playful pushing knocks the walrus across the room – only making the sap more lovesick. Wally hops back on the sofa – but his weight bounces Woody into the air, flipping his wig. Woody falls back to earth, bouncing Wally skyward. Woody swiftly plants a fork in the sofa cushions, tines upward. YEOW! Just for fun, before Wally can plummet again, Woody plants a traffic signal in the living room, making Wally “Stop” and “Go” in mid-fall.

But the jig is up. Woody begis devouring every morsel of food he can find as fast as he can, through a series of spot gags including dancing Wally into a crash into his grand piano, intercepting Wally’s punch with an ice-box door, pecking to splinters a club wielded by the walrus, then hitting him in the face with one of his own pies, avoiding having a hole cut out in the floor around him by substituting in his place a heavy safe, and kicking backwards a huge firecracker left by the walrus under his tail, then closing a fire door on Wally to make him take the full force of the explosion. Woody reenters the pantry through a hole blasted in the fire door, then emerges carrying the leading handles of a long stretcher. In the middle of the stretcher are all of Wally’s remaining foodstuffs piled high – with Woody himself riding along as a passenger (?) – then, to make matters more confusing, Woody emerges again, also carrying the rear handles of the stretcher! As a closing thought, he finally gets to explain his never-ending appetite: “I do the work of three woodpeckers around here. That’s why I eat so much!”

Apple Andy (Lantz/Universal, Andy Panda, 4/9/46 – Dick Lundy, dir.), presents an interesting apple mash-up of ideas from two previous screen successes from rival studios, into a fun dose of spiked cider. The films in question providing inspiration were Donald’s Better Self (1938) from Disney, and Pigs is Pigs (1937) from Warner (discussed previously in thus series). In a mini-morality play, Andy Panda wanders along a country road, encountering the apple orchard of Jonathan Winesap (with the interesting company motto, “Annapolis a day is the navy way.”) A notable musical talent appears anonymously in this film – vocalist Del Porter, formerly of the country-style quartet of singers and instrumentalists known as “The Foursome” (who introduced on Broadway the Gershwin standard, “Bidin’ My Time” from “Girl Crazy”), and by the time of this production was well-settled into a regular association with Spike Jones and his City Slickers. Due to the presence of Porter in the studio, Andy Panda develops an unusual proficiency in plating the ocarina or “Sweet Potato” for a catchy tune in the opening shots. Said instrument was Del’s personal specialty, played during his Foursome days in four-part harmony by each member of the group, so the solo is obviously provided by him. As Andy spies the trees full of apples, he looks longingly at them from behind a separating wire fence. In a puff of smoke, a devil version of himself (voiced by recognizable Lantz villain Lionel Stander) appeas, coaxing Andy to hop over the fence and grab some. Just as quickly, an angel-robed, haloed Panda floats in, advising Andy against the folly of such a thought. “Aw, button your lip”, says the devil panda, litterally doing so to the angel. “Well, why not?”, says Andy, convinced by the devil’s spiel and finally getting a word in edgewise. He tries to hop over, but gets his feet caught uin the wire, falling on his face on the other side of the fence, with the petals of two flowers from the ground pressed into his eye sockets. The angel further pleads with Andy that this is the first step to his downfall, but the devil gives angel-Andy a hotfoot, sending him rocketing skyward. It seems as though devil-Andy has the upper hand, but there is a new fly in the ointment. “Hey, these appleas are green”, observes Andy. “Lemme see that”, says the devil, taking and concealing from Andy the green apple he is handed. Producing from nowhere a spray can full of red food color (or is it paint?), the devil spray-coats the green apple to turn it bright red. “You’re wrong, pal. Dese apples are poifect!”. responds the devil, handing back the tainted fruit to Andy. Andy happily chomps down on the bait. The devil proceeds to spray-paint more and more of the tree’s holdings, while gluttony sets in upon the greedy Andy, who devours the unripe fruit left and right. A massive pile of applecores builds at the base of the tree – until the effects of the not-yet-fit to consume crop take their toll. Andy himself turns green, wobbles groggily atop the tree limb, and falls to the ground in a heap, while the devil scornfully laughs in victory.

Apple Andy (Lantz/Universal, Andy Panda, 4/9/46 – Dick Lundy, dir.), presents an interesting apple mash-up of ideas from two previous screen successes from rival studios, into a fun dose of spiked cider. The films in question providing inspiration were Donald’s Better Self (1938) from Disney, and Pigs is Pigs (1937) from Warner (discussed previously in thus series). In a mini-morality play, Andy Panda wanders along a country road, encountering the apple orchard of Jonathan Winesap (with the interesting company motto, “Annapolis a day is the navy way.”) A notable musical talent appears anonymously in this film – vocalist Del Porter, formerly of the country-style quartet of singers and instrumentalists known as “The Foursome” (who introduced on Broadway the Gershwin standard, “Bidin’ My Time” from “Girl Crazy”), and by the time of this production was well-settled into a regular association with Spike Jones and his City Slickers. Due to the presence of Porter in the studio, Andy Panda develops an unusual proficiency in plating the ocarina or “Sweet Potato” for a catchy tune in the opening shots. Said instrument was Del’s personal specialty, played during his Foursome days in four-part harmony by each member of the group, so the solo is obviously provided by him. As Andy spies the trees full of apples, he looks longingly at them from behind a separating wire fence. In a puff of smoke, a devil version of himself (voiced by recognizable Lantz villain Lionel Stander) appeas, coaxing Andy to hop over the fence and grab some. Just as quickly, an angel-robed, haloed Panda floats in, advising Andy against the folly of such a thought. “Aw, button your lip”, says the devil panda, litterally doing so to the angel. “Well, why not?”, says Andy, convinced by the devil’s spiel and finally getting a word in edgewise. He tries to hop over, but gets his feet caught uin the wire, falling on his face on the other side of the fence, with the petals of two flowers from the ground pressed into his eye sockets. The angel further pleads with Andy that this is the first step to his downfall, but the devil gives angel-Andy a hotfoot, sending him rocketing skyward. It seems as though devil-Andy has the upper hand, but there is a new fly in the ointment. “Hey, these appleas are green”, observes Andy. “Lemme see that”, says the devil, taking and concealing from Andy the green apple he is handed. Producing from nowhere a spray can full of red food color (or is it paint?), the devil spray-coats the green apple to turn it bright red. “You’re wrong, pal. Dese apples are poifect!”. responds the devil, handing back the tainted fruit to Andy. Andy happily chomps down on the bait. The devil proceeds to spray-paint more and more of the tree’s holdings, while gluttony sets in upon the greedy Andy, who devours the unripe fruit left and right. A massive pile of applecores builds at the base of the tree – until the effects of the not-yet-fit to consume crop take their toll. Andy himself turns green, wobbles groggily atop the tree limb, and falls to the ground in a heap, while the devil scornfully laughs in victory.

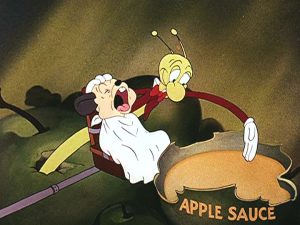

Andy begins to hallucinate from the apples’ effects. The cores fallen around him form a circle, sprout hands and feet, and begin to dance like little elves to more ocarina music. From behind another tree come a chorus line of high-stepping apples wearing skirts, intriduced by a vaudeville-style stage sign reading “Apple Core-us Girls”. A large apple in the tree develops a face and (with the assist of Porter) begins to sing an original ditty, “Up Jumped the Devil (in the White Nightgown)”, bouncing on Andy’s aching stomach. The situation becomes even more dream-like, as a transparent Andy “soul” is lured by the devil from Andy’s carcass with the bait of an apple on a stick, the devil then opening a hole in the ground for Andy’s soul to fall into. Andy’s soul falls in slow motion into the bowels of the earth, landing in a mechanical chair that is for all intents and purposes a twin to Friz Freleng’s torture chair from Pigs is Pigs. Clamps bind Andy to the chair, and the devil pulls a series of levers to activate the diabolical mechanisms just as the mad scientist did in Freleng’s epic. A first device places an apple on a rotating spit through the core, then the chair forces Andy’s large front teeth into it as it rotates, producing the same force-feeding effct as Freleng’s rotating pie dispenser. In another corner, a non-mechanical creature gives assistance to the devil – a giant worm out of an equally giant apple, who forces Andy’s head back, fills his mouth with handfuls of applesauce, then wipes up the mess on Andy’s face with a napkin (ensuring thorough cleanliness by pushing the napkin through one of Andy’s ears and out the other). An evil tree root with a face on the trunk above uses a ladle to scoop up spoons of apple cider, and pours them all over Andy’s face, leaving his gasping and sputtering for air. This is our cue to return to reality, as the dousing of Andy’s face is really angel-Ansy poring water upon him to revive him. The Devil is still laughing hysterically, but the Angel decides the time has arrived for aggressive action. With the Devil’s mouth open, the Angel shoves about a half-dozen green apples into the Devil’s mouth, then zippers his lips shut upon them. The Angel then tweaks the Devil’s nose, slaps his face around, delivers a series of boxing blows, and a final upper-cut that send the Devil skyward, his horns embedding in the bottom of a tree limb above, from which he hangs helplessly, as his eyes weakly open to reveal applecores in the places his irises should be. Andy and the Angel, now in step with one another, dance away in perfect synchronization with each other and with the closing strains of the featured original tune, which provides the final moral: “Don’t listen to the devil. He ain’t on the level.”

Andy begins to hallucinate from the apples’ effects. The cores fallen around him form a circle, sprout hands and feet, and begin to dance like little elves to more ocarina music. From behind another tree come a chorus line of high-stepping apples wearing skirts, intriduced by a vaudeville-style stage sign reading “Apple Core-us Girls”. A large apple in the tree develops a face and (with the assist of Porter) begins to sing an original ditty, “Up Jumped the Devil (in the White Nightgown)”, bouncing on Andy’s aching stomach. The situation becomes even more dream-like, as a transparent Andy “soul” is lured by the devil from Andy’s carcass with the bait of an apple on a stick, the devil then opening a hole in the ground for Andy’s soul to fall into. Andy’s soul falls in slow motion into the bowels of the earth, landing in a mechanical chair that is for all intents and purposes a twin to Friz Freleng’s torture chair from Pigs is Pigs. Clamps bind Andy to the chair, and the devil pulls a series of levers to activate the diabolical mechanisms just as the mad scientist did in Freleng’s epic. A first device places an apple on a rotating spit through the core, then the chair forces Andy’s large front teeth into it as it rotates, producing the same force-feeding effct as Freleng’s rotating pie dispenser. In another corner, a non-mechanical creature gives assistance to the devil – a giant worm out of an equally giant apple, who forces Andy’s head back, fills his mouth with handfuls of applesauce, then wipes up the mess on Andy’s face with a napkin (ensuring thorough cleanliness by pushing the napkin through one of Andy’s ears and out the other). An evil tree root with a face on the trunk above uses a ladle to scoop up spoons of apple cider, and pours them all over Andy’s face, leaving his gasping and sputtering for air. This is our cue to return to reality, as the dousing of Andy’s face is really angel-Ansy poring water upon him to revive him. The Devil is still laughing hysterically, but the Angel decides the time has arrived for aggressive action. With the Devil’s mouth open, the Angel shoves about a half-dozen green apples into the Devil’s mouth, then zippers his lips shut upon them. The Angel then tweaks the Devil’s nose, slaps his face around, delivers a series of boxing blows, and a final upper-cut that send the Devil skyward, his horns embedding in the bottom of a tree limb above, from which he hangs helplessly, as his eyes weakly open to reveal applecores in the places his irises should be. Andy and the Angel, now in step with one another, dance away in perfect synchronization with each other and with the closing strains of the featured original tune, which provides the final moral: “Don’t listen to the devil. He ain’t on the level.”

Cockatoos for Two (February, 1947 – Bob Wickersham/Robert Clampett (uncredited), dir.) – Produced during the Katz-Binder last gasps of the Columbia Screen Gems studio, IMDB indicates that the former Warner executives sought the services of now-exiled and between-gigs wildman Bob Clampett to work on this project. Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine what, if anything, of the final work is Clampett’s brainchild (with the possible exception of one Bugs Bunny-style kiss), as he left almost as fast as he came during mid-production. Nevertheless, some elements of this film have a definite Warner feel – not the least of them being the featured celebrity impersonation of Peter Lorre as a primary character, much in the same way the Termite Terrace boys under Robert McKimson had featured a similar cameo in Daffy Duck’s “Birth of a Notion” – with identical voicing by Stan Freberg. The film could almost be called a war between gluttons, each with a different culinary goal. Lorre plays a mad millionaire of eccentric tastes, who can’t stand to look another filet mignon or dish of caviar in the face, but craves a “new taste sensation”. The answer to his prayer is dropped on his doorstep with the evening mail, as an equally-rich friend (Hermosa Redondo) gifts him his rare $57,000 pet cockatoo, with instructions to “keep him warm and feed well.” Lorre envisions the bird “warming” in a roasting pan, and himself with knife and fork about to “feed well”. Meanwhile, roaming the streets and going door to door is a “homeless homing pigeon”, who also happens to have a large appetite. He asks to be put up for the night, but only receives a swift kick from Lorre’s shoe. “I’ll find a home if it takes the rest of this cartoon”, the pigeon vows. A delivery man passes with a gilded cage, about to make delivery of the cockatoo. Seeing a tag on the cage with the “keep warm, feed well” instructions, the pigeon hatches a scheme. Sneaking into the cage under its cloth cover, he assaults the occupant, tying the cockatoo up and booting him out of the cage onto the pavement – but not before plucking a few key plumage feathers from him to use as a disguise.

Cockatoos for Two (February, 1947 – Bob Wickersham/Robert Clampett (uncredited), dir.) – Produced during the Katz-Binder last gasps of the Columbia Screen Gems studio, IMDB indicates that the former Warner executives sought the services of now-exiled and between-gigs wildman Bob Clampett to work on this project. Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine what, if anything, of the final work is Clampett’s brainchild (with the possible exception of one Bugs Bunny-style kiss), as he left almost as fast as he came during mid-production. Nevertheless, some elements of this film have a definite Warner feel – not the least of them being the featured celebrity impersonation of Peter Lorre as a primary character, much in the same way the Termite Terrace boys under Robert McKimson had featured a similar cameo in Daffy Duck’s “Birth of a Notion” – with identical voicing by Stan Freberg. The film could almost be called a war between gluttons, each with a different culinary goal. Lorre plays a mad millionaire of eccentric tastes, who can’t stand to look another filet mignon or dish of caviar in the face, but craves a “new taste sensation”. The answer to his prayer is dropped on his doorstep with the evening mail, as an equally-rich friend (Hermosa Redondo) gifts him his rare $57,000 pet cockatoo, with instructions to “keep him warm and feed well.” Lorre envisions the bird “warming” in a roasting pan, and himself with knife and fork about to “feed well”. Meanwhile, roaming the streets and going door to door is a “homeless homing pigeon”, who also happens to have a large appetite. He asks to be put up for the night, but only receives a swift kick from Lorre’s shoe. “I’ll find a home if it takes the rest of this cartoon”, the pigeon vows. A delivery man passes with a gilded cage, about to make delivery of the cockatoo. Seeing a tag on the cage with the “keep warm, feed well” instructions, the pigeon hatches a scheme. Sneaking into the cage under its cloth cover, he assaults the occupant, tying the cockatoo up and booting him out of the cage onto the pavement – but not before plucking a few key plumage feathers from him to use as a disguise.

The cage is delivered to an eager Lorre. “Welcome. Saludos Amigos!” says Lorre. “Saludos a Meatball, yourself”, replies the pigeon. After giving Lorre a “$57,000 handshake”, the pigeon pulls out knife, form, and bib, demanding to know “When do we eat?” He emphasizes his immediate need for grub by tugging backwards on his own skin, making his chest appear to be skin and bones. A disappointed and worried Lorre admits that the bird does need fattening up – to which the bird asides to the audience, “This guy’s a pushover.” While the bird continues with sob story that without food he will simply waste away. Lorre determines that his charge mustn’t lose “one precious ounce”. A banquet table is soon set with the finest food money can buy, including turkey, roast, watermelon, corn, cakes, gelatin, wine, and assorted other delicacies. Putting on a bathing cap, the pigeon swan dives from a tall chair for a swim through the gelatin, then unhinges his jaw and scoops up in one swoop everything on the table. With a burp, he notes, “Well that was pretty good for an appetizer, but when do we eat?” He has hardly noticed that his build has changed to that of a spherical roly-poly. Walking past a mirror and seeing his reflection, he talks to the image in the mistaken belief it is another bird. “Hiya, Butterball! You live here, too?” Then he realizes, “Good gravy, it’s me! What happened to my girlish figure?” Lorre suggests a sure cure – a Turkish bath – which of course turns out to be in the roasting pan, complete with carrot garnishment, in an oven equipped with “atomic heat”. Lorre almost gets cold feet, claiming it’s “too horrible”, but reverts back to form, almost doing the pigeon in, until the real cockatoo returns, represented by a barrister bird, who claims the pigeon is an imposter. The pigeon gladly confesses to be rid of the place, telling the cockatoo, “You’re going to love it here”, as he painfully reinserts one of the cockatoo’s tail feathers into the rare bird’s rear end. As he is leaving, the pigeon wonders just how he might have tasted had Lorre’s plan succeeded, and attempts to take a bite of his own wing. He is left spitting out the horrible flavor, then closes by telling the audience, “It’d have served him right.”

King Size Canary (MGM, 12/6/47 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Avery’s surreal masterpiece, taking a one-joke note on fattening a character up, and simply letting it grow to the most outrageous of proportions. The problem arises when a hungry cat invades a pantry in search of his evening meal, only to find the cupboards nearly as bare as the kitchen of Old Mother Hubbard (including an ice box with sign “For Rent” as a furnished room, and a sardine can empty except for a sign reading “Kilroy was here”). One lone can remains – of Cat Food. The cat punctures it open, pouring out a live mouse. But the mouse fast-talks his way out of the siuation, claiming he has already “seen this cartoon before”, and that before the picture is over, “I save your life.” As to what to do to appease the cat’s immediate hunger, the mouse suggests eating the “great big, fat, juicy canary” in the next room. The cat reaches into a covered cage, only to find the world’s most scrawny stick of a bird, who weakly sighs, “Well, I’ve been sick.” Even facing starvation, the cat won’t stoop so low as to munch on this tired specimen, and pushes the bird away. Taking one last look over the contents of the kitcken, the cat discovers a bottle of “Jumbo Gro” plant food, depicting before and after pictures of a wilted daisy transformed into a giant sunflower. A “Brainstorm” erupts in a flashing cloud over the cat’s head, as the label transforms to pictures of the sickly bird mutated into a large healthy avian. The cat grabs the bird and force feeds him a swig of the elixir. The bird begins to grow almost immediately, as the cat carries him back to the dinner table – but fails to note that the bird contimues to grow, exponentially, while being carried. By the time the cat has removed the feathers from one drumstick, the bird towers above the cat, almost to the ceiling. Shocked at the size of his “victim”, the cat sheepishly replaces the feathers he has plucked, and makes a run for freedom. The bird is puzzled, until he looks down at his own frame and notices the massive change. Now realizing he has the upper hand, the bird pounces on the cat, twisting his leg as if in a wrestling hold. But nearby is the shelf the cat left the bottle on (through it seems the camera has been moving about in many other directions, so that the bottle should have been far, far away). The cat takes a drink himself – and soon is filling the room. As the bird retreats through the wall, the cat follows, tossing the bottle out the window where it will presumably do no more harm. No such luck, as it lands in the mouth of a bulldog outside.

King Size Canary (MGM, 12/6/47 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Avery’s surreal masterpiece, taking a one-joke note on fattening a character up, and simply letting it grow to the most outrageous of proportions. The problem arises when a hungry cat invades a pantry in search of his evening meal, only to find the cupboards nearly as bare as the kitchen of Old Mother Hubbard (including an ice box with sign “For Rent” as a furnished room, and a sardine can empty except for a sign reading “Kilroy was here”). One lone can remains – of Cat Food. The cat punctures it open, pouring out a live mouse. But the mouse fast-talks his way out of the siuation, claiming he has already “seen this cartoon before”, and that before the picture is over, “I save your life.” As to what to do to appease the cat’s immediate hunger, the mouse suggests eating the “great big, fat, juicy canary” in the next room. The cat reaches into a covered cage, only to find the world’s most scrawny stick of a bird, who weakly sighs, “Well, I’ve been sick.” Even facing starvation, the cat won’t stoop so low as to munch on this tired specimen, and pushes the bird away. Taking one last look over the contents of the kitcken, the cat discovers a bottle of “Jumbo Gro” plant food, depicting before and after pictures of a wilted daisy transformed into a giant sunflower. A “Brainstorm” erupts in a flashing cloud over the cat’s head, as the label transforms to pictures of the sickly bird mutated into a large healthy avian. The cat grabs the bird and force feeds him a swig of the elixir. The bird begins to grow almost immediately, as the cat carries him back to the dinner table – but fails to note that the bird contimues to grow, exponentially, while being carried. By the time the cat has removed the feathers from one drumstick, the bird towers above the cat, almost to the ceiling. Shocked at the size of his “victim”, the cat sheepishly replaces the feathers he has plucked, and makes a run for freedom. The bird is puzzled, until he looks down at his own frame and notices the massive change. Now realizing he has the upper hand, the bird pounces on the cat, twisting his leg as if in a wrestling hold. But nearby is the shelf the cat left the bottle on (through it seems the camera has been moving about in many other directions, so that the bottle should have been far, far away). The cat takes a drink himself – and soon is filling the room. As the bird retreats through the wall, the cat follows, tossing the bottle out the window where it will presumably do no more harm. No such luck, as it lands in the mouth of a bulldog outside.

After being chased around the city, the bird passes the house again, and stops cold, suddenly taking on an air of confidence. The cat puzzles at this, until the bulldog rounds the corner of the house, now twice the cat’s size. Now the cat is the pursued prey, while the bulldog frops the bottle down the house’s chimney. It rolls out of the fireplace over to a mousehole, where the mouse seen earlier is reading a copy of “The Lost Squeakend”. Of course, the mouse takes a guzzle. Before we know it, the pursued cat is stopping cold in the middle of the chase, pointing with confidence to draw the bulldog’s attention around the corner of a skyscraper – where the mouse waits, now five times larger than any of them. “The dog exits in panic, as the mouse reminds the cat. “I yold ya I’d save your life. And here’s the little bottle that did the whole trick.” So big he walks in a rotund waddle, the mouse bids the cat so long. “But hey”, calls the cat after him, “I’m still hungry!” However, this problem is easily remedied, as the cat envisions, written on the mouse’s huge rear end, the word “FOOD”. Another dose from the bottle, and the cat is following behind at skyscraper height, carrying a huge knife and fork. An epic chase follows, with the characters dwarfing the scenery of Boulder Dam, the Grand Canyon, and the Rocky Mountains. Taking notable size liberties in one shot, the seemingly smaller duo pause as the mouse hides in a tunnel in a mountainside, while the cat reaches in. The mouse sneaks out the tunnel’s rear entrance and grabs away the bottle the cat left on the ground. One swallow, and the mouse has the upper hand, bashing the cat repeatedly over the head. The cat’s arm elastically stretches to snatch back the bottle, and the cat grows into the clouds. The mouse does the same, and the two vie back and forth for title of top man on the totem pole – until the sound effect of a sputtering engine signals that the bottle’s supply is being exhausted – with the characters in a tie for height advantage. The action comes to a stop, as the mouse addresses the audience. “Ladies and gentlemen, we’re going to have to end this picture. We just ran out of the stuff. Good Night.” The mouse drops the empty bottle – but it appears to take several seconds before we hear the distant tinkle of glass. It is no wonder. The camera pulls back, to reveal the cat and mouse, waving a fond farewell to the camera, with only a small blue dot supporting their weight amidst the vastness of space. That small dot – the planet Earth!

After being chased around the city, the bird passes the house again, and stops cold, suddenly taking on an air of confidence. The cat puzzles at this, until the bulldog rounds the corner of the house, now twice the cat’s size. Now the cat is the pursued prey, while the bulldog frops the bottle down the house’s chimney. It rolls out of the fireplace over to a mousehole, where the mouse seen earlier is reading a copy of “The Lost Squeakend”. Of course, the mouse takes a guzzle. Before we know it, the pursued cat is stopping cold in the middle of the chase, pointing with confidence to draw the bulldog’s attention around the corner of a skyscraper – where the mouse waits, now five times larger than any of them. “The dog exits in panic, as the mouse reminds the cat. “I yold ya I’d save your life. And here’s the little bottle that did the whole trick.” So big he walks in a rotund waddle, the mouse bids the cat so long. “But hey”, calls the cat after him, “I’m still hungry!” However, this problem is easily remedied, as the cat envisions, written on the mouse’s huge rear end, the word “FOOD”. Another dose from the bottle, and the cat is following behind at skyscraper height, carrying a huge knife and fork. An epic chase follows, with the characters dwarfing the scenery of Boulder Dam, the Grand Canyon, and the Rocky Mountains. Taking notable size liberties in one shot, the seemingly smaller duo pause as the mouse hides in a tunnel in a mountainside, while the cat reaches in. The mouse sneaks out the tunnel’s rear entrance and grabs away the bottle the cat left on the ground. One swallow, and the mouse has the upper hand, bashing the cat repeatedly over the head. The cat’s arm elastically stretches to snatch back the bottle, and the cat grows into the clouds. The mouse does the same, and the two vie back and forth for title of top man on the totem pole – until the sound effect of a sputtering engine signals that the bottle’s supply is being exhausted – with the characters in a tie for height advantage. The action comes to a stop, as the mouse addresses the audience. “Ladies and gentlemen, we’re going to have to end this picture. We just ran out of the stuff. Good Night.” The mouse drops the empty bottle – but it appears to take several seconds before we hear the distant tinkle of glass. It is no wonder. The camera pulls back, to reveal the cat and mouse, waving a fond farewell to the camera, with only a small blue dot supporting their weight amidst the vastness of space. That small dot – the planet Earth!

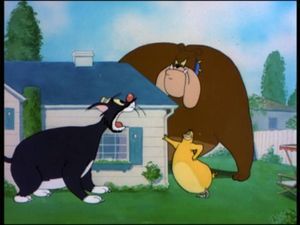

Hop, Look and Listen (Warner, Sylvester amd Hippity Hopper, 4/17/48 – Robert McKimson, dir.). It’s taken a long time for one of these episodes to arrive along one of our trails. This, being the first and possibly the best of the series, logically appears the most deserving. Unless we ever do a trail about kangaroos, or mistaken identity, it would be difficult to place the rest, as they are all about the same. Anyway, for the first time Sylvester meets the “:giant mouse”, freshly escaped from his mother’s cage in the zoo. Sylvester himself is engaged in the unusual pastime of hunting for mice with full fishing gear, casting a line into a mousehole, baited with cheese from his rod and reel. But the catches are below the legal limit, as measured by Sylvester’s ruler. Sylvester notes that when they are too small, it “takes a mess of ‘em to fill the skillet”, and they “just fry down to a gob of grease”. Fishing gets more interesting when Hippity invades the home’s basement, finding a way to get inside the wall and grab Sylvester’s line. Sylvester tugs with all his might, and pulls Hippity clear through the wall, leaving a silhouette where the mousehole had been. His eyes at first ignoring the obvious, Sylvester measires the catch with his ruler, between bounces. Then dawn breaks. “A king-size mouse! A muscle-bound mastodon!” Sylvester runs screaming into the yard, but is intercepted by the family pet bulldog. The dog is disgusted at Sylvester’s fear, regardless of the alleged size of the rodent, and tells Sylvester, “Ain’t ya’ got no professional pride?” He throws Sylvester back inside, with instructions to get that mouse “or I’ll beat ‘ya to a pulp.” A variety of encounters ensue between cat and kangaroo, always ending with Sylvester pummeled, and the dog tossing him right back inside into the fray. Sylvester observes that he never though just being a pussy cat could get so complicated. Finally, after being tossed out of the wall himself (leaving a new Sylvester-shaped hole), Sylvester determines something is wrong with this picture. “I must be slippin’. Out of condition. Sloppy. I gotta exercise. Strengthen my sinews.”

Hop, Look and Listen (Warner, Sylvester amd Hippity Hopper, 4/17/48 – Robert McKimson, dir.). It’s taken a long time for one of these episodes to arrive along one of our trails. This, being the first and possibly the best of the series, logically appears the most deserving. Unless we ever do a trail about kangaroos, or mistaken identity, it would be difficult to place the rest, as they are all about the same. Anyway, for the first time Sylvester meets the “:giant mouse”, freshly escaped from his mother’s cage in the zoo. Sylvester himself is engaged in the unusual pastime of hunting for mice with full fishing gear, casting a line into a mousehole, baited with cheese from his rod and reel. But the catches are below the legal limit, as measured by Sylvester’s ruler. Sylvester notes that when they are too small, it “takes a mess of ‘em to fill the skillet”, and they “just fry down to a gob of grease”. Fishing gets more interesting when Hippity invades the home’s basement, finding a way to get inside the wall and grab Sylvester’s line. Sylvester tugs with all his might, and pulls Hippity clear through the wall, leaving a silhouette where the mousehole had been. His eyes at first ignoring the obvious, Sylvester measires the catch with his ruler, between bounces. Then dawn breaks. “A king-size mouse! A muscle-bound mastodon!” Sylvester runs screaming into the yard, but is intercepted by the family pet bulldog. The dog is disgusted at Sylvester’s fear, regardless of the alleged size of the rodent, and tells Sylvester, “Ain’t ya’ got no professional pride?” He throws Sylvester back inside, with instructions to get that mouse “or I’ll beat ‘ya to a pulp.” A variety of encounters ensue between cat and kangaroo, always ending with Sylvester pummeled, and the dog tossing him right back inside into the fray. Sylvester observes that he never though just being a pussy cat could get so complicated. Finally, after being tossed out of the wall himself (leaving a new Sylvester-shaped hole), Sylvester determines something is wrong with this picture. “I must be slippin’. Out of condition. Sloppy. I gotta exercise. Strengthen my sinews.”

Set to a lively score of Carl Stalling football rally-type music, a creative montage follows, all set against backgrounds of various single primary colors, with Sylvester vigorously engaging in rope skipping, dumbbell lifting, treadmill running, rowing in a rowing machine, and punching both a small round punching bag and a cylindrical full-body sized one with his gloves, then slapping his gloves together in satisfaction tht he is ready for the main event. The lush residential backgrounds suddenly return as Sylvester squares off against the foe. Sylvester comes out swinging, while Hippity merely bobs up and down, avoiding the blows. Sylvester carefully gauges the distance for a knockout punch, and rears back to deliver the killer blow. Hippity chooses this moment to advance, rearing up on his tail, and smashing Sylvester with the full force of both feet. Sylvester sails through a closed window into the yard – and just as suddenly sails back inside through another closed window, from the unseen force of the bulldog’s blow. Hippity catches Sylvester on his feet, and twirls the helpless cat like a black whirlwind, finally launching him outside again. To Hippity’s surprise, Mama appeas in the living room, claiming (in what I believe is her only speaking role in the entire series) that she’s been looking all over for him, and instructs Hippity to re-enter her pouch with the command, “Wipe your feet and come in the house.” Back in the yard, Sylvester is nearly unconscious against the wall of the bulldog’s doghouse. The revolted dog decides there’s only one way to teach this hopeless excuse for a feline a lesson – show him how it’s done. The dog marches into the house, intent on pulverizing the mouse himself – but instead reverts into total shock, imitating Bert Lahr’s “Nyumg, Nyung, Nyung!”, as he views the even more intimidating visage of Mama, with a second head protruding from the pouch. The dog hastens back to the yard, packs a grip, folds up his doghouse into a second suitcase, and drags Sylvester along for a quick exit. Comparing notes with Sylvester a few moments later, the dog concludes they’re both pixilated. “When ya’ sees mice that big, with two heads, it’s time to get on the ‘water wagon’.” The camera puulls back to reveal that they have taken the phrase literally, as they make their exit riding on the rear of an actual street-cleaning Water Wagon, for the iris out.

Set to a lively score of Carl Stalling football rally-type music, a creative montage follows, all set against backgrounds of various single primary colors, with Sylvester vigorously engaging in rope skipping, dumbbell lifting, treadmill running, rowing in a rowing machine, and punching both a small round punching bag and a cylindrical full-body sized one with his gloves, then slapping his gloves together in satisfaction tht he is ready for the main event. The lush residential backgrounds suddenly return as Sylvester squares off against the foe. Sylvester comes out swinging, while Hippity merely bobs up and down, avoiding the blows. Sylvester carefully gauges the distance for a knockout punch, and rears back to deliver the killer blow. Hippity chooses this moment to advance, rearing up on his tail, and smashing Sylvester with the full force of both feet. Sylvester sails through a closed window into the yard – and just as suddenly sails back inside through another closed window, from the unseen force of the bulldog’s blow. Hippity catches Sylvester on his feet, and twirls the helpless cat like a black whirlwind, finally launching him outside again. To Hippity’s surprise, Mama appeas in the living room, claiming (in what I believe is her only speaking role in the entire series) that she’s been looking all over for him, and instructs Hippity to re-enter her pouch with the command, “Wipe your feet and come in the house.” Back in the yard, Sylvester is nearly unconscious against the wall of the bulldog’s doghouse. The revolted dog decides there’s only one way to teach this hopeless excuse for a feline a lesson – show him how it’s done. The dog marches into the house, intent on pulverizing the mouse himself – but instead reverts into total shock, imitating Bert Lahr’s “Nyumg, Nyung, Nyung!”, as he views the even more intimidating visage of Mama, with a second head protruding from the pouch. The dog hastens back to the yard, packs a grip, folds up his doghouse into a second suitcase, and drags Sylvester along for a quick exit. Comparing notes with Sylvester a few moments later, the dog concludes they’re both pixilated. “When ya’ sees mice that big, with two heads, it’s time to get on the ‘water wagon’.” The camera puulls back to reveal that they have taken the phrase literally, as they make their exit riding on the rear of an actual street-cleaning Water Wagon, for the iris out.

Butterscotch and Soda (Paramount/Famous, Little Audrey, 7/6/48, Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Undeniably the finest Little Audrey cartoon ever made. This film officially launched her in a “star” series, though not her first appearance on screen. It has been compared by many to the Ray Milland feature, “The Lost Weekend”, dealing cleverly with the subject of addiction – not to alcohol or drugs, but to candy! Inheriting the political;y incorrect domestic, Mandy, from the Little Lulu series, the film opens with Mandy arriving home from a run for groceries, only to discover that Audrey hasn’t touched a thing on her plate from lunch. The reason is apparent to the audience – Aufrey’s appetite is otherwise occupied in another room, with a bag of candy and an “eeny meeny miney mo” game to determine which pieces get devoured first. When Mandy walks in on her little game, Audrey grabs a pencil, drawing a face on the white sack holding the candy, to disguise it as a doll of Casper! Mandy isn’t fooled, and orders her to finish everything on her lunch plate. Audrey begins to empty the plate – through sleight of hand using two forks, one in the right hand placing candy in her mouth from a hidden bag under the table, and one in her left hand passing the wholesome food to her dog, who waits with salt and pepper shaker for the tasty morsels. Mandy putters in the kitchen, unable to understand how a child can eat candy “48 hours a day”, then catches sight of Audrey’s trick. Audrey receives a shock when she discovers that the next forkfull of food from her left hand is not clamped onto by the jaws of her dog, but those of Mandy! No amount of explanation is going to get her out of this jam.

Butterscotch and Soda (Paramount/Famous, Little Audrey, 7/6/48, Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – Undeniably the finest Little Audrey cartoon ever made. This film officially launched her in a “star” series, though not her first appearance on screen. It has been compared by many to the Ray Milland feature, “The Lost Weekend”, dealing cleverly with the subject of addiction – not to alcohol or drugs, but to candy! Inheriting the political;y incorrect domestic, Mandy, from the Little Lulu series, the film opens with Mandy arriving home from a run for groceries, only to discover that Audrey hasn’t touched a thing on her plate from lunch. The reason is apparent to the audience – Aufrey’s appetite is otherwise occupied in another room, with a bag of candy and an “eeny meeny miney mo” game to determine which pieces get devoured first. When Mandy walks in on her little game, Audrey grabs a pencil, drawing a face on the white sack holding the candy, to disguise it as a doll of Casper! Mandy isn’t fooled, and orders her to finish everything on her lunch plate. Audrey begins to empty the plate – through sleight of hand using two forks, one in the right hand placing candy in her mouth from a hidden bag under the table, and one in her left hand passing the wholesome food to her dog, who waits with salt and pepper shaker for the tasty morsels. Mandy putters in the kitchen, unable to understand how a child can eat candy “48 hours a day”, then catches sight of Audrey’s trick. Audrey receives a shock when she discovers that the next forkfull of food from her left hand is not clamped onto by the jaws of her dog, but those of Mandy! No amount of explanation is going to get her out of this jam.

Mandy marches Audrey up to her room, ordering her to stay there until she learns to lay off the candy. But temptation remains, as Mandy spies a rope tied to the radiator and dangling out the window. Outside, a string of candy bags is suspended, each one labelled for a different time – “Saturday”, and then (in clever tie-in to a Bing Crosby song hit from the feature production “Dixie”), “Sunday”. “Monday” “and Always”. Mandy confiscates all the hidden swag, and, to complete the tie-in to Ray Milland, states Audrey will spend the “whole weekend” in confinement, if necessary. Audrey pouts, but her mind quickly turns from her disappointment to her cravings. She assures herself that somewhere in the room, there is a remaining secret stash. She runs through the room, turning upside down and inside out the contents of drawers, shelves, picture frames, chairs, tables, bedsheets, bedding, and pillowcase, discovering nothing. As she begins to pant from exhaustion and anxiety, she suddenly notices the shadow of a bag hidden inside the glass globe of her ceiling lamp. Piling furniture sky high to reach the lighting fixture, Audrey anxiously retrieves the sack, and tears it open. In another possible character cameo, a look-alike to Herman the mouse is found inside, casually chewing the last piece from the bag. Audrey is defeated – but not in spirit, as her mind begins to play cruel tricks on her. She spies an umbrella in a corner – and mistakes it for a candy cane. Seizing it, she ravenously bites down, only to find herself with a mouth full of fabric. Next, she spies what she believes is a chocolate bird in the manner of an Easter candy. In reality, it is a live canary in a cage, who flies in a panic as Audrey’s anxious hands clutch for it. The bird curves in flight, and Audrey’s eyes lapse into dementia, as the image transforms into the random visage of a swooping bat. In a magnificently executed scene (which I first saw in striking 35mm nitrate from an original archive release print, and which it still feels will live forever in my nightmares), an ear-piercing scream is heard from a horrified Audrey, with grotesque circular mouth wide open, whose image is seen skrinking and pulling away from the camera as the room, now depicted as impressionistic rectangles of garish primary colors, swirls into an erratic and violent spin, entirely engulfing the camera. (For my money, this would be the most compelling piece or surrealism Famous Studios ever created – only topped by its predecessor Fleischer Studios, “Swing You Sinners”.) Out of this chaos of color, a large red sphere materializes against a background of blue, pulling backwards into the background painting, where a dawning sky reveals it to be a huge cherry atop a pink mountain made of ice cream. Audrey has lost her mind entirely, and entered the fantasy world of Candyland, much in the manner of John Foster’s candy moon, or segments of the studio’s own earlier work, Max Fleischer’s “Somewhere in Dreamland.”

Mandy marches Audrey up to her room, ordering her to stay there until she learns to lay off the candy. But temptation remains, as Mandy spies a rope tied to the radiator and dangling out the window. Outside, a string of candy bags is suspended, each one labelled for a different time – “Saturday”, and then (in clever tie-in to a Bing Crosby song hit from the feature production “Dixie”), “Sunday”. “Monday” “and Always”. Mandy confiscates all the hidden swag, and, to complete the tie-in to Ray Milland, states Audrey will spend the “whole weekend” in confinement, if necessary. Audrey pouts, but her mind quickly turns from her disappointment to her cravings. She assures herself that somewhere in the room, there is a remaining secret stash. She runs through the room, turning upside down and inside out the contents of drawers, shelves, picture frames, chairs, tables, bedsheets, bedding, and pillowcase, discovering nothing. As she begins to pant from exhaustion and anxiety, she suddenly notices the shadow of a bag hidden inside the glass globe of her ceiling lamp. Piling furniture sky high to reach the lighting fixture, Audrey anxiously retrieves the sack, and tears it open. In another possible character cameo, a look-alike to Herman the mouse is found inside, casually chewing the last piece from the bag. Audrey is defeated – but not in spirit, as her mind begins to play cruel tricks on her. She spies an umbrella in a corner – and mistakes it for a candy cane. Seizing it, she ravenously bites down, only to find herself with a mouth full of fabric. Next, she spies what she believes is a chocolate bird in the manner of an Easter candy. In reality, it is a live canary in a cage, who flies in a panic as Audrey’s anxious hands clutch for it. The bird curves in flight, and Audrey’s eyes lapse into dementia, as the image transforms into the random visage of a swooping bat. In a magnificently executed scene (which I first saw in striking 35mm nitrate from an original archive release print, and which it still feels will live forever in my nightmares), an ear-piercing scream is heard from a horrified Audrey, with grotesque circular mouth wide open, whose image is seen skrinking and pulling away from the camera as the room, now depicted as impressionistic rectangles of garish primary colors, swirls into an erratic and violent spin, entirely engulfing the camera. (For my money, this would be the most compelling piece or surrealism Famous Studios ever created – only topped by its predecessor Fleischer Studios, “Swing You Sinners”.) Out of this chaos of color, a large red sphere materializes against a background of blue, pulling backwards into the background painting, where a dawning sky reveals it to be a huge cherry atop a pink mountain made of ice cream. Audrey has lost her mind entirely, and entered the fantasy world of Candyland, much in the manner of John Foster’s candy moon, or segments of the studio’s own earlier work, Max Fleischer’s “Somewhere in Dreamland.”

Audrey finds herself sitting upon a chcolate road – and wastes no time in tearing up pavement squares to wolf down as an appetizer. Her attention is caught by a nearby field, where lollipops grow like weeds. Audrey finds a large sack and starts reaping a harvest. With a half-filled bag, she walks along, alternating licks upon red, yellow, and green lollipops in her other hand, with the sound effects of a changing traffic signal each time she changes flavor. More sweet stuff for her sack is acquired by the panful, from a simmering kettle of “Boston Baked Jelly Beans”. She continues down the road, her sack now dragging on the ground behind her, as she passes a billboard cleverly lampooning a famous Camel cigarette ad slogan which seemed to continue for decades – “I’d walk a mile for a Caramel.” A final load for her goodie bag is acquired from a dump truck unloading a cargo of licorice. But, as with Foster’s cats, this overeating eventually takes its toll. Aufrey’s progress slows to a crawl, as her face turns a sickly green, then alternates in a series of red and white peppermint stripes. Hallucinations set in again, as her huge sack transforms into a sort of burlap ghost monster, who begins to sing a minor key taunt to Audrey, “You’ve Got the Tummy Ache Blues.” The song is picked up by a quintet of giant licorice drops (somewhat politically incorrect in suggesting black singers) who float through the air in pursuit of a retreating Audrey. A “Candy Bar” offering a happy hour special of the title drink, “Butterscotch and Soda”, further develops a face and chimes into the tune. Four giant peppermint stick “convicts” working on a rock-candy pile, raise their sledge hammers and join in pursuit, chasing Audrey onto a still-hot fresh fudge road. Audrey’s feet become trapped in the fudge, as a giant stream-powered “Candy Roll” advances forward to flatten her. In another wonderfully-formatted shot of guaranteed nightmare fodder, we receive a point-of-view camera glimpse of being compressed by the giant steamroller wheel, and the scene goes black. It is unclear whether Audrey awakens in an afterlife, or has merely been pushed by the roll through Candyland’s outer candy shell into its hidden inner core – but somewhere in the lower nether-regions of this universe, a hoarde of various candies administers upon Audrey the final punishment, much in the manner of the torture chairs from “Pigs Is Pigs” and “Apple Andy”. A bound Audrey has her mouth forced open, while a seemingly endless stream of more candy shoots inside from a humongous sack. The camera closes in on the candy flow for another grotesque image – then mercifully dissolves us back to the real world, where the flow of candy is replaced by the flow of water from a wet handkerchief held over Audrey’s forehead, Mandy has discovered Audrey unconscious on her bed, and is relieved to find out, “You is alive.” To make amends for the ordeal, Mandy offers Audrey a box of “all the candy you want.” But Audrey has had all the sweets she can stand, at least for the time being, and retracts from the box, speeding away into the kitchen. There, at the table, Mandy discovers Audrey, but in a reversal of positions from before. Now, her dog sits at the table, eating her candy with one fork, while Audrey waits on her knees where the dog had once been, awaiting the forkfulls of real food from the dog’s left paw with anxious shakers of salt and pepper.

Audrey finds herself sitting upon a chcolate road – and wastes no time in tearing up pavement squares to wolf down as an appetizer. Her attention is caught by a nearby field, where lollipops grow like weeds. Audrey finds a large sack and starts reaping a harvest. With a half-filled bag, she walks along, alternating licks upon red, yellow, and green lollipops in her other hand, with the sound effects of a changing traffic signal each time she changes flavor. More sweet stuff for her sack is acquired by the panful, from a simmering kettle of “Boston Baked Jelly Beans”. She continues down the road, her sack now dragging on the ground behind her, as she passes a billboard cleverly lampooning a famous Camel cigarette ad slogan which seemed to continue for decades – “I’d walk a mile for a Caramel.” A final load for her goodie bag is acquired from a dump truck unloading a cargo of licorice. But, as with Foster’s cats, this overeating eventually takes its toll. Aufrey’s progress slows to a crawl, as her face turns a sickly green, then alternates in a series of red and white peppermint stripes. Hallucinations set in again, as her huge sack transforms into a sort of burlap ghost monster, who begins to sing a minor key taunt to Audrey, “You’ve Got the Tummy Ache Blues.” The song is picked up by a quintet of giant licorice drops (somewhat politically incorrect in suggesting black singers) who float through the air in pursuit of a retreating Audrey. A “Candy Bar” offering a happy hour special of the title drink, “Butterscotch and Soda”, further develops a face and chimes into the tune. Four giant peppermint stick “convicts” working on a rock-candy pile, raise their sledge hammers and join in pursuit, chasing Audrey onto a still-hot fresh fudge road. Audrey’s feet become trapped in the fudge, as a giant stream-powered “Candy Roll” advances forward to flatten her. In another wonderfully-formatted shot of guaranteed nightmare fodder, we receive a point-of-view camera glimpse of being compressed by the giant steamroller wheel, and the scene goes black. It is unclear whether Audrey awakens in an afterlife, or has merely been pushed by the roll through Candyland’s outer candy shell into its hidden inner core – but somewhere in the lower nether-regions of this universe, a hoarde of various candies administers upon Audrey the final punishment, much in the manner of the torture chairs from “Pigs Is Pigs” and “Apple Andy”. A bound Audrey has her mouth forced open, while a seemingly endless stream of more candy shoots inside from a humongous sack. The camera closes in on the candy flow for another grotesque image – then mercifully dissolves us back to the real world, where the flow of candy is replaced by the flow of water from a wet handkerchief held over Audrey’s forehead, Mandy has discovered Audrey unconscious on her bed, and is relieved to find out, “You is alive.” To make amends for the ordeal, Mandy offers Audrey a box of “all the candy you want.” But Audrey has had all the sweets she can stand, at least for the time being, and retracts from the box, speeding away into the kitchen. There, at the table, Mandy discovers Audrey, but in a reversal of positions from before. Now, her dog sits at the table, eating her candy with one fork, while Audrey waits on her knees where the dog had once been, awaiting the forkfulls of real food from the dog’s left paw with anxious shakers of salt and pepper.

The Cuckoo (1948 – David Hand, dir.), one of the earliest of the “Animaland” shorts produced by Hand’s newly-established studio in England in association with J. Arthur Rank distribution, has been extensively reviewed in my previous article on egg cartoons, “Happy Henfruit (Part 6)” on this site. Its title star is the bird you love to hate – a pot-bellied lummox with an appetite rivaling Gus Goose, who invades a sparrow family by way of the true fact of nature of cuckoos never building their own nest, but substituting their eggs into the nests of others. The birds’ actual offspring is rapidly eaten out of house and home, with his unexpected “brother” hogging all the grub. The little sparrow experiences nightmares about it, in a dream sequence which is easily on a parallel with Dumbo’s celebrated “Pink Elephants on Parade” segment – a production number entitled, “The Cuckoo’s Not So Cuckoo After All”. The dream begins with three large ice cream sundaes appearing (in bright colors set against a black background, with the sparrow appearing in muted shades of grey, allowing for striking color contrast/highlights). The sparrow lifts a spoon in attempt to take a scoop, only to have each sundae transform into a singing version of his “brother”, taunting him with lyrics like, “You’re the one who’s crazy. It takes brains to be so lazy.” The cuckoo trio dance in a circle, hoarding piles of Tecnicolor goodies under their wings. The little sparrow follows with a tray, catching a full plate of goodies that fall out from the bigger birds’ grip, but as he turns to make a getaway, various windows opens from nowhere in the background, and the cuckoos snatch the contents of the tray away. A pink flood of ice cream envelops the scene, and the three cuckoos come sailing along atop it in a small ship, dressed in sailor suits. One of them raises a spyglass, and sights a small island, topped with a large basket of fruit filled to overflowing like a cornucopia. The three cuckoos dive into the basket, harnessing it to a bubble to sail away through the air like a balloon. Somehow, Junior sparrow is left trapped inside the bubble, rolling around helplessly, until the bubble pops, and Junior falls, to be left dangling from the crescent moon, as he awakes to a new but dismal dawn. Even in real life, the cuckoo’s gluttony continues, as the paunchy bird inadvertently rescues the sparrow from the stewpot of a weasel – only because he is after the soup broth in the pot. While the sparrow ultimately in turn saves the cuckoo’s neck from the clutches of the weasel, the cuckoo shows no gratitude whatsoever, returning to feast on the stewpot’s contents and leaving his brother to face the weasel alone. The sparrow finally outwits the weasel by setting the villain’s tail afire with a hot coal, then tells his ungrateful “brother” off before leaving. Cuckoo almost shows some remorse, but instinctively returns to the pot, swallowing the whole kettle, contents and all – then getting stuck in the door of the cave entrance, as the words “The End” appear on his rear for the fade out.

The Cuckoo (1948 – David Hand, dir.), one of the earliest of the “Animaland” shorts produced by Hand’s newly-established studio in England in association with J. Arthur Rank distribution, has been extensively reviewed in my previous article on egg cartoons, “Happy Henfruit (Part 6)” on this site. Its title star is the bird you love to hate – a pot-bellied lummox with an appetite rivaling Gus Goose, who invades a sparrow family by way of the true fact of nature of cuckoos never building their own nest, but substituting their eggs into the nests of others. The birds’ actual offspring is rapidly eaten out of house and home, with his unexpected “brother” hogging all the grub. The little sparrow experiences nightmares about it, in a dream sequence which is easily on a parallel with Dumbo’s celebrated “Pink Elephants on Parade” segment – a production number entitled, “The Cuckoo’s Not So Cuckoo After All”. The dream begins with three large ice cream sundaes appearing (in bright colors set against a black background, with the sparrow appearing in muted shades of grey, allowing for striking color contrast/highlights). The sparrow lifts a spoon in attempt to take a scoop, only to have each sundae transform into a singing version of his “brother”, taunting him with lyrics like, “You’re the one who’s crazy. It takes brains to be so lazy.” The cuckoo trio dance in a circle, hoarding piles of Tecnicolor goodies under their wings. The little sparrow follows with a tray, catching a full plate of goodies that fall out from the bigger birds’ grip, but as he turns to make a getaway, various windows opens from nowhere in the background, and the cuckoos snatch the contents of the tray away. A pink flood of ice cream envelops the scene, and the three cuckoos come sailing along atop it in a small ship, dressed in sailor suits. One of them raises a spyglass, and sights a small island, topped with a large basket of fruit filled to overflowing like a cornucopia. The three cuckoos dive into the basket, harnessing it to a bubble to sail away through the air like a balloon. Somehow, Junior sparrow is left trapped inside the bubble, rolling around helplessly, until the bubble pops, and Junior falls, to be left dangling from the crescent moon, as he awakes to a new but dismal dawn. Even in real life, the cuckoo’s gluttony continues, as the paunchy bird inadvertently rescues the sparrow from the stewpot of a weasel – only because he is after the soup broth in the pot. While the sparrow ultimately in turn saves the cuckoo’s neck from the clutches of the weasel, the cuckoo shows no gratitude whatsoever, returning to feast on the stewpot’s contents and leaving his brother to face the weasel alone. The sparrow finally outwits the weasel by setting the villain’s tail afire with a hot coal, then tells his ungrateful “brother” off before leaving. Cuckoo almost shows some remorse, but instinctively returns to the pot, swallowing the whole kettle, contents and all – then getting stuck in the door of the cave entrance, as the words “The End” appear on his rear for the fade out.

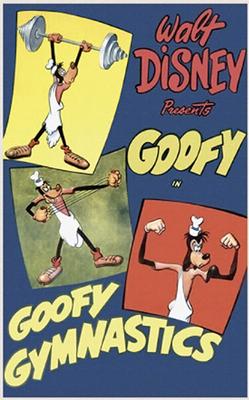

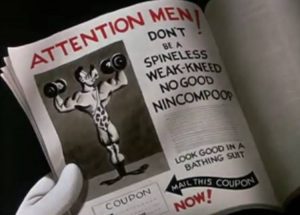

Goofy Gymnastics (Disney,/RKO. Goofy, 9/23/49 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – Just before the conversion of Goofy into George Geef, everyman, this little gem provided the Goof with one of his last roles faithful to his original character concept. A sort of return to the sports reel series, the Goof is not presented as overweight (that would come later), but as the tired scrawny weakling in desperate need of building-up. Arriving home from the days’ toil exhausted, Goof, through blurry eyes, finds a magazine ad in a publication called “Vimm”, reading “Don’t be a spineless, weak-kneed, no good nincompoop.” An omniscient announcer tells him to “Be a man”, and hurry to fill in a coupon to obtain a complete body-building course. That doesn’t take long – no sooner has Goofy placed the coupon and an envelope in the mail box, than a motor inside is activated to open a hatchway door from the base of the mailbox, dropping out the heavy package anticipated. Upon arriving home, Goofy rapidly sets up equipment found inside the box, transforming his living room into an instant gymnasium. Goofy replaces his work suit with a pair of leopard-spotted leotards. (Notably, his wardrobe in this film is in transition. While in the opening scenes he wears a fedora and business suit of the type to become commonplace in his “everyman” cartoons, his leotard outfit is topped by the traditional “Goofy” hat he had worn since his debut in 1931.) The nerve center of this home program is a phonograph record with instructions. (The long-play record was generally introduced by Columbia for public consumption circa 1949 – however, Goofy’s record appears to spin at a rate faster than 33 1/3 rpm. The maximum playing time for even a 12″ 78 with fine grooving was generally only about five minutes a side, so, assuming the events of the cartoon take place without a break, the record appears to continue for the absolute maximum playing time possible. Does this seem a bit too convenient, like a writer’s wishful thinking?) Goof nearly loses the record from the start in an awkward stumble – but the disc flies neatly onto the turntable, simultaneously jostling the motor into play position, and the tone arm into proper position at the start of the recording.

Goofy Gymnastics (Disney,/RKO. Goofy, 9/23/49 – Jack Kinney, dir.) – Just before the conversion of Goofy into George Geef, everyman, this little gem provided the Goof with one of his last roles faithful to his original character concept. A sort of return to the sports reel series, the Goof is not presented as overweight (that would come later), but as the tired scrawny weakling in desperate need of building-up. Arriving home from the days’ toil exhausted, Goof, through blurry eyes, finds a magazine ad in a publication called “Vimm”, reading “Don’t be a spineless, weak-kneed, no good nincompoop.” An omniscient announcer tells him to “Be a man”, and hurry to fill in a coupon to obtain a complete body-building course. That doesn’t take long – no sooner has Goofy placed the coupon and an envelope in the mail box, than a motor inside is activated to open a hatchway door from the base of the mailbox, dropping out the heavy package anticipated. Upon arriving home, Goofy rapidly sets up equipment found inside the box, transforming his living room into an instant gymnasium. Goofy replaces his work suit with a pair of leopard-spotted leotards. (Notably, his wardrobe in this film is in transition. While in the opening scenes he wears a fedora and business suit of the type to become commonplace in his “everyman” cartoons, his leotard outfit is topped by the traditional “Goofy” hat he had worn since his debut in 1931.) The nerve center of this home program is a phonograph record with instructions. (The long-play record was generally introduced by Columbia for public consumption circa 1949 – however, Goofy’s record appears to spin at a rate faster than 33 1/3 rpm. The maximum playing time for even a 12″ 78 with fine grooving was generally only about five minutes a side, so, assuming the events of the cartoon take place without a break, the record appears to continue for the absolute maximum playing time possible. Does this seem a bit too convenient, like a writer’s wishful thinking?) Goof nearly loses the record from the start in an awkward stumble – but the disc flies neatly onto the turntable, simultaneously jostling the motor into play position, and the tone arm into proper position at the start of the recording.

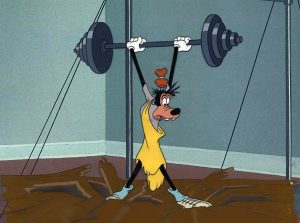

First exercise on the program is the barbells.

First exercise on the program is the barbells.

Goofy follows all the warm up postures recommended, though merely bending down almost pops out a disc in his spine. With his knees flexed, Goofy is commanded to “lift”. His feet rise, but not his arms, which stay planted to the floor with the barbells. Goofy tries to lift again, but attains no leverage, as he is standing on the bar of the barbells itself rather than the floor. In an interesting move lessening the line mileage for all involved in the production, Goofy strains in place, his muscles flexing to such an extent, he pops all the spots off his leopard-skin leotard. Next, the retainers holding the wheel-shaped weights to the bar come loose, allowing the weights to press at a slant, lowering the bar and jamming Goofy’s fingers between the bar and the floor. After prying his digits loose, Goofy lifts the individual weights back onto the bar, dropping one on his foot. He attempts to lift the barbell over his back, and is bowled over by the weight and pinned to the ground from behind. A twirl leads to an attempt to lift the weights with both arms and feet – only leading to the weight retainers again coming loose, with the weights converging in mid-bar to pin all of Goofy’s limbs inbetween. Goofy rocks on his back to get loose, only managing to wind up atop the wheels with all limbs still pinned, rolling as if riding a unicycle. This wheeled wonder rolls up a ramp and down the other side, flipping Goofy over the top on the descent, so that at last he comes to a standing position with the barbell above his head as intended. However, there is still a fly in the ointment – a literal fly, who lands on the weights. His every tread is a matter of breaking point for the floorboards below Goofy’s feet. And the Goof suddenly plunges through a hole in the floor, crashing off-camera through several stories of apartments below, to the screams of the neighbors, and the verbal reaction of voice veteran Billy Bletcher for a single line of dialogue: “Get him outta here!” As the sounds of destruction finally die away, the Goof reappears at his own front door, falling on his face from exhaustion, while the recorded announcer concludes, “Now that wasn’t so bad, was it?”

The record asks Goofy to “compare yourself with the chart”, a wall-mounted life-size illustration of an Adonis, exhibiting the desired perfect dimensions. The Goof’s chest and arms look like beanpoles as compared against this muscle-bound framework, yet Goofy strives to flex his muscles to see if anything matches. The one minuscule bulge he can muster keeps shifting from one arm to the other, then finally appears in its greatest prominence protruding from his nose. Then, the whole chart rolls Goody up in it like a windowshade, as the record comments that “We are beginning to fit.”

The record asks Goofy to “compare yourself with the chart”, a wall-mounted life-size illustration of an Adonis, exhibiting the desired perfect dimensions. The Goof’s chest and arms look like beanpoles as compared against this muscle-bound framework, yet Goofy strives to flex his muscles to see if anything matches. The one minuscule bulge he can muster keeps shifting from one arm to the other, then finally appears in its greatest prominence protruding from his nose. Then, the whole chart rolls Goody up in it like a windowshade, as the record comments that “We are beginning to fit.”

Second exercise is chin-ups, upon a bar cross-mounted above Goofy’s head. The Goof’s first effort to raise himself to the bar is misalligned, only lifting his head to smash against the bar. He finally figures out how to bring his chin over the top, and in a close-up shot appears to be successfully performing the maneuver. Unfortunately, as the camera pulls back, we discover that it is the bar, not the Goof, which is slipping up and down from improper installation, and the Goof’s feet never leave the ground. The loosened bar finally falls on Goofy’s head, producing a lump. Goofy presses the lump back into his head, and it surprisingly travels from his head to his arm for a “quick muscular development”, as narrated from the recording.