The advent of the 1960’s saw little change in the concept, powers, or design of robots, who, for the most part, followed in the troth of the wheels of those who had rolled before them. However, there were some exceptions. One of our entries discussed below would be among the first to designate humanoid robots as gender-specific – coming up with designs for a robot who is definitely female (though you’d never guess it from the brawny power she packs). Another innovation was to create a robot so life-like, it can mingle with humans undetected. Notably, within two years after this idea would appear in animated form, it would be mirrored in a short-lived but memorable CBS sitcom starring Robert Cummings and Julie Newmar, entitled “My Living Doll”. In later years, a lifelike robot which others accept as if human would also become the subject of a syndicated sitcom, using a child-robot referred to as “Small Wonder”. Oddly, both these new concepts would arise from the budget-plagued Paramount studios – demonstrating that ingenuity isn’t necessarily limited in direct proportion to the limits of the pocketbook.

International Woodpecker (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 7/1/57 – Paul J. Smith, dir.), receives very brief mention for one isolated gag. In Woody’s retelling of ancient history and how historic woodpeckers shaped it, one sequence has Woody’s ancestor as a passenger aboard the Mayflower. (“Anyone for shuffleboard?”, he inquires of the crew.) Woody refers in narration to the period as one of “Wooden ships and iron men” – and the visual takes it literally, depicting a metal robot at the helm of the ship’s steering wheel.

For the sake of argument, I call brief attention to Mighty Mouse’s Outer Space Visitor (Terrytoons/Fox, November, 1959 – Dave Tendlar, dir.) and “The Mysterious Package” (12/15/60, Mannie Davis, dir.), both of which have been previously discussed in my column of a few seasons back, “Spacey Aliens”, to which the reader is directed for reference. Each features a creature who in many features resembles a robot. However, the origins of these creatures bring into question whether they can truly be classified as mechanical. Outer Space Visitor features a baby alien who is definitely a living, breathing creature, whose “Pop” is a massive monster. Although Pop appears visually to be in many if not all respects mechanical, it can only be assumed in view of his living son that he himself must be living – and so not technically a robot. The same dilemma surrounds classification of the creature in “The Mysterious Package” – which ultimately turns out to be a little man who was transformed into the appearance of a robot by a witch’s evil spell. Thus, any mechanical features could at most be attributed to an exo-skeleton, while the man inside remained naturally real. The reader can thus quibble whether either of these films belongs within this trail, and I invite any lively comment.

Silly Science (Paramount, Noveltoon, May, 1960 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) Is a spot-gag reel modeled after Tex Avery’s “Of Tomorrow” sub-series. Among its gags are some robotic household appliances, including an automatic dishwasher consisting uf mechanical gands from the wall, who vigorously scrub each plate, then smash each one into pieces for deposit in the trash can instead of stacking. A robot carpet sweeper consists of a low-slung body on wheels that rolls under furniture, then lifts it off the floor with a built-in hydraulic jack for complete cleaning underneath. When finished, it proceeds to a throw rug, lifts one end with a mechanical hand, reveals a vacuum nozzle attachment, and sets the vacuum into reverse, blowing the dirt under the rug, then tamping down the rug to a level flatness before leaving. Another sequence shows two scientists in a laboratory handling radioactive materials in a sealed chamber, by means of robotic arms manipulated by controls attached to the fingers of each scientist, as the narrator describes them as making each “carefully-planned move”. Inside the chamber, the vials of radioactive material are merely being shifted in position around a checkerboard, as one scientist jumps three bottles of the other scientist, and sweeps them from the table.

Mint Men (Terrytoons/Fox, Heckle and Jeckle, 5/1/60 – Dave Tendlar, dir.) – Framed as if a documentary, this film chronicles the “heroic” efforts of two employees of the U.S. Mint (the twin magpies), assigned the task of troubleshooting a newly-created robot guard, designed to prevent thefts at the mint, by putting it to the test against all manner of efforts to smuggle money out of the printing rooms. Aside from the dangers of the attack of the robot itself, H&J’s primary obstacle is Dimwit, another mint employee who acts as guard and activator of the robot in case of emergency – who is unaware of H&J’s secret assignment to put the robot through its paces. Dimwit mans a wall control button, which opens a closet in which the robot remains at the ready. The robot has a cylindrical body and a head shaped like a dome with three projecting antennae. Its primary weapons are a pair of arms which emerge from the body cavity wearing boxing gloves, with the ability to deliver blows by forward punches to the gut, and in two spinning modes, one by spinning its body with arms outstretched while the head remains motionless, and the other by an overhand vertical spin as if both hands were mounted on a wheel. Additionally, the robot possesses a vacuum attachment which emerges from its chest to suck up any stolen money, and an extra arm extension carrying a schoolboy ruler, to slap the wrists of any criminal offender as if he were a “bad boy” in grade school!

Mint Men (Terrytoons/Fox, Heckle and Jeckle, 5/1/60 – Dave Tendlar, dir.) – Framed as if a documentary, this film chronicles the “heroic” efforts of two employees of the U.S. Mint (the twin magpies), assigned the task of troubleshooting a newly-created robot guard, designed to prevent thefts at the mint, by putting it to the test against all manner of efforts to smuggle money out of the printing rooms. Aside from the dangers of the attack of the robot itself, H&J’s primary obstacle is Dimwit, another mint employee who acts as guard and activator of the robot in case of emergency – who is unaware of H&J’s secret assignment to put the robot through its paces. Dimwit mans a wall control button, which opens a closet in which the robot remains at the ready. The robot has a cylindrical body and a head shaped like a dome with three projecting antennae. Its primary weapons are a pair of arms which emerge from the body cavity wearing boxing gloves, with the ability to deliver blows by forward punches to the gut, and in two spinning modes, one by spinning its body with arms outstretched while the head remains motionless, and the other by an overhand vertical spin as if both hands were mounted on a wheel. Additionally, the robot possesses a vacuum attachment which emerges from its chest to suck up any stolen money, and an extra arm extension carrying a schoolboy ruler, to slap the wrists of any criminal offender as if he were a “bad boy” in grade school!

Heckle and Jeckle fully exploit the one notable directive in the robot’s programming – to beat up on whoever has possession of the money – in order to keep themselves out of harm’s way. The running gag of the picture is that every time the robot approaches, the birds fling whatever money they are in possession of into the hands of Dimwit – who thus receives the robot’s beating. As the money is ultimately returned each time to the mint, H&J do not view this programming as a flaw – even though Dimwit becomes increasingly the worse for wear as a result of the boys’ efforts. H&J assume a series of disguises to accomplish their raids. They begin as janitors, sweeping into stacks with their brooms the “messy old money” they find lying around on the mint’s conveyor belts, to “get at the root of all evil”. They appear as plumbers, clearing a non-existent clog in the sink by stuffing money through the pipe into a waiting satchel. As delivery men, they install a large floor-model fan, then give the room proper “circulation” by blowing money out the window into the waiting net of Jeckle. As ambulance men, they cart away a load of money in a stretcher as an “errand of mercy”. (A clever gag has the robot leave Dimwit wrapped up in the stretcher canvas and poles, as if encased in an Indian teepee.) As firemen (with smoke provided by Jeckle puffing a cigar), they stuff money through the fire hose. All incidents end up the same for Dimwit, to the point where he waves bye-bye to the camera before taking his last beating. The magpies receive medals of honor in a public ceremony, for risking their lives and facing danger. “Risking their lives and facing danger?” complains a black-eyed Dimwit from a window above, until he gets an idea. From the window, he tosses out a sack of money, calling out, “Here boys. Catch.” The magpies suddenly find themselves “holding the bag” and the robot is released. Finally, things are as they should be, with the robot pursuing the magpies over the farthest hills, for the fade out.

Heckle and Jeckle fully exploit the one notable directive in the robot’s programming – to beat up on whoever has possession of the money – in order to keep themselves out of harm’s way. The running gag of the picture is that every time the robot approaches, the birds fling whatever money they are in possession of into the hands of Dimwit – who thus receives the robot’s beating. As the money is ultimately returned each time to the mint, H&J do not view this programming as a flaw – even though Dimwit becomes increasingly the worse for wear as a result of the boys’ efforts. H&J assume a series of disguises to accomplish their raids. They begin as janitors, sweeping into stacks with their brooms the “messy old money” they find lying around on the mint’s conveyor belts, to “get at the root of all evil”. They appear as plumbers, clearing a non-existent clog in the sink by stuffing money through the pipe into a waiting satchel. As delivery men, they install a large floor-model fan, then give the room proper “circulation” by blowing money out the window into the waiting net of Jeckle. As ambulance men, they cart away a load of money in a stretcher as an “errand of mercy”. (A clever gag has the robot leave Dimwit wrapped up in the stretcher canvas and poles, as if encased in an Indian teepee.) As firemen (with smoke provided by Jeckle puffing a cigar), they stuff money through the fire hose. All incidents end up the same for Dimwit, to the point where he waves bye-bye to the camera before taking his last beating. The magpies receive medals of honor in a public ceremony, for risking their lives and facing danger. “Risking their lives and facing danger?” complains a black-eyed Dimwit from a window above, until he gets an idea. From the window, he tosses out a sack of money, calling out, “Here boys. Catch.” The magpies suddenly find themselves “holding the bag” and the robot is released. Finally, things are as they should be, with the robot pursuing the magpies over the farthest hills, for the fade out.

Electronica (Paramount, Modern Madcap, 7/1/60 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – It’s been observed that the Paramount animators seemed to really have it in for their wives, frequently characterizing all such females as domineering battle-axes, and plotting their fates in nefarious ways (such as in the infamous “The Plot Sickens”). This one is no exception, opening upon a pipsqueak moustached husband (Henry) slaving away washing dishes, while a wife twice his size barks orders while lounging in an easy chair, and reading a book entitled “How to Eat Like a Pig and Stay Slim”. While picking up dust in a dustpan, Henry spits a stray newspaper page, with advertisement that’s just what the doctor ordered: “Are you tired of doing household chores? Get a mechanical servant. Acme Robot Co., 100 Main Street, NY”. While his wife hollers her next order for Henry to mop the floors, Henry sneaks out, tying the mop handle to the swinging pendulum of a kitchen clock, to fool his wife into thinking the moving mop head in the doorway is being controlled by him.

Electronica (Paramount, Modern Madcap, 7/1/60 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – It’s been observed that the Paramount animators seemed to really have it in for their wives, frequently characterizing all such females as domineering battle-axes, and plotting their fates in nefarious ways (such as in the infamous “The Plot Sickens”). This one is no exception, opening upon a pipsqueak moustached husband (Henry) slaving away washing dishes, while a wife twice his size barks orders while lounging in an easy chair, and reading a book entitled “How to Eat Like a Pig and Stay Slim”. While picking up dust in a dustpan, Henry spits a stray newspaper page, with advertisement that’s just what the doctor ordered: “Are you tired of doing household chores? Get a mechanical servant. Acme Robot Co., 100 Main Street, NY”. While his wife hollers her next order for Henry to mop the floors, Henry sneaks out, tying the mop handle to the swinging pendulum of a kitchen clock, to fool his wife into thinking the moving mop head in the doorway is being controlled by him.

The Acme Co. has a wide variety of servants to choose from. Particularly of note in the line-up is a light blue robot in a maid’s outfit, with a head shaped like a cylinder on its side – a dead-ringer for the Jetsons’ Rosey the Robot, excepting having shoes instead of wheels – although Rosey would not appear on the airwaves for over another year! One may only assume the boys at H-B were watching this episode. Henry selects a robot maid twice the size of the others, recommended for heavy duty, named Electronica. These new labor-saving devices however, have a few limitations in their circuitry. They are voice activated, but only respond to one voice, which the salesman sets by taking a voice sample from Henry through a microphone. They also have to be told when to stop – or they continue to act upon their last command. Henry takes Electronica home to spring as a surprise on the wife. The missus is not quite sure what to make of her, though the robot efficiently sweeps the rug (hiding the dirt under the carpet). Henry tells the robot to serve them both coffee, which Electronica performs promptly. The phone rings, and Henry rises from the table to answer it – forgetting the need to tell the robot when to stop. By the time Henry returns, the wife is screaming, and each side of the dining table is laden with a tower of about forty cups of steaming coffee. Henry utters the stop command, and tells the wife not to worry, as the robot can clean this mess as fast as she made it. Electronica does so by wrapping up all the cups and saucers into one bundle inside the tablecloth, and hauling the load to the sink. She cleans the items efficiently, and Henry’s wife finally begins to be impressed. Henry instructs the robot to put the cups and plates into the closet after she is finished, then tells his wife that, with the housework taken care of, he’s going down to the corner for a beer. He departs, again forgetting the need to issue the stop command. On top of this, Electronica has misinterpreted the last instruction, and inserts a stack of dishes into the shaft of the dumbwaiter instead of the china closet. Henry’s wife races down a couple of flights of stairs, outrunning the force of gravity to catch the plates before they crash on the floor of the dumbwaiter shaft.

The Acme Co. has a wide variety of servants to choose from. Particularly of note in the line-up is a light blue robot in a maid’s outfit, with a head shaped like a cylinder on its side – a dead-ringer for the Jetsons’ Rosey the Robot, excepting having shoes instead of wheels – although Rosey would not appear on the airwaves for over another year! One may only assume the boys at H-B were watching this episode. Henry selects a robot maid twice the size of the others, recommended for heavy duty, named Electronica. These new labor-saving devices however, have a few limitations in their circuitry. They are voice activated, but only respond to one voice, which the salesman sets by taking a voice sample from Henry through a microphone. They also have to be told when to stop – or they continue to act upon their last command. Henry takes Electronica home to spring as a surprise on the wife. The missus is not quite sure what to make of her, though the robot efficiently sweeps the rug (hiding the dirt under the carpet). Henry tells the robot to serve them both coffee, which Electronica performs promptly. The phone rings, and Henry rises from the table to answer it – forgetting the need to tell the robot when to stop. By the time Henry returns, the wife is screaming, and each side of the dining table is laden with a tower of about forty cups of steaming coffee. Henry utters the stop command, and tells the wife not to worry, as the robot can clean this mess as fast as she made it. Electronica does so by wrapping up all the cups and saucers into one bundle inside the tablecloth, and hauling the load to the sink. She cleans the items efficiently, and Henry’s wife finally begins to be impressed. Henry instructs the robot to put the cups and plates into the closet after she is finished, then tells his wife that, with the housework taken care of, he’s going down to the corner for a beer. He departs, again forgetting the need to issue the stop command. On top of this, Electronica has misinterpreted the last instruction, and inserts a stack of dishes into the shaft of the dumbwaiter instead of the china closet. Henry’s wife races down a couple of flights of stairs, outrunning the force of gravity to catch the plates before they crash on the floor of the dumbwaiter shaft.

By the time she gets the dishes back upstairs, Electronica is in repeat mode, and dropping another stack of dishes into the shaft. This circle of action repeats a couple of times, the wife barely saving each stack in the basement. Then, as the wife reaches her floor for the third time, she crashes chest-first straight into Electronica, knocking the robot and her next load of dishes backwards, spreading broken dish fragments everywhere. Electronica’s robot eyes blink in red, with the word “Tilt” appearing within them. The robot goes haywire, and starts inventing its own chores without waiting to be ordered. It grabs a basket of dirty laundry, rolls through a wall without looking for a door, and dumps the clothes inside the TV set, turning on a program depicting ocean waves as if putting the laundry into a wash cycle. She grabs a lawn mower, and begins mowing the carpet. Henry’s wife is only one step ahead of the mower blades, and dives into a Murphy bed to hide under the covers. Electronica slams the bed into upright position to mow under it, in the process driving Mrs. Henry through the brick wall in the back of the mattress closet. “That monster has got to go!”, screams the Missus, As Electronica chooses her third self-appointed task (mopping the floors with green paint instead of water), the wife sends into the room a wind-up toy mouse (something she probably borrowed from Jerry in Push Button Kitty). Like all females, Electronica reacts in startled terror at the sight of the mouse, and rolls in a hasty retreat, colliding with who knows what in an offscreen crash, while Mrs. Henry breaks into a beaming smile. The scene dissolves to the home’s exterior, as Henry returns from his beer binge – only to find the shattered remains of Electronica piled up with the outgoing trash. He hears his name hollered in the same domineering voice as when the film began, and is ordered by his wife to clean up the devastation left in the robot’s wake. Henry is about to resume his henpecked ways, but then changes expression to an evil grin, as an idea hatches in his brain. The scene dissolves again, and, to our surprise, we view Mrs. Henry, down on hands and knees, scrubbing paint from the floor. The camera pans to Henry, now occupying the easy chain, and reading a book entitled “How To Be Happy Though Married”. He barks an order to the wife to scrub the woodwork next. The wife throws down the scrub=brush, and is about to rise in protest to Henry’s treatment of her – when a whip cracks over her back, making her resume her scrubbing position at double the tempo. The camera returns to Henry, revealing that just behind him stands an even larger male robot, controlling the whip cracking at Henry’s command, while Henry smiles happily to the audience for the fade out.

By the time she gets the dishes back upstairs, Electronica is in repeat mode, and dropping another stack of dishes into the shaft. This circle of action repeats a couple of times, the wife barely saving each stack in the basement. Then, as the wife reaches her floor for the third time, she crashes chest-first straight into Electronica, knocking the robot and her next load of dishes backwards, spreading broken dish fragments everywhere. Electronica’s robot eyes blink in red, with the word “Tilt” appearing within them. The robot goes haywire, and starts inventing its own chores without waiting to be ordered. It grabs a basket of dirty laundry, rolls through a wall without looking for a door, and dumps the clothes inside the TV set, turning on a program depicting ocean waves as if putting the laundry into a wash cycle. She grabs a lawn mower, and begins mowing the carpet. Henry’s wife is only one step ahead of the mower blades, and dives into a Murphy bed to hide under the covers. Electronica slams the bed into upright position to mow under it, in the process driving Mrs. Henry through the brick wall in the back of the mattress closet. “That monster has got to go!”, screams the Missus, As Electronica chooses her third self-appointed task (mopping the floors with green paint instead of water), the wife sends into the room a wind-up toy mouse (something she probably borrowed from Jerry in Push Button Kitty). Like all females, Electronica reacts in startled terror at the sight of the mouse, and rolls in a hasty retreat, colliding with who knows what in an offscreen crash, while Mrs. Henry breaks into a beaming smile. The scene dissolves to the home’s exterior, as Henry returns from his beer binge – only to find the shattered remains of Electronica piled up with the outgoing trash. He hears his name hollered in the same domineering voice as when the film began, and is ordered by his wife to clean up the devastation left in the robot’s wake. Henry is about to resume his henpecked ways, but then changes expression to an evil grin, as an idea hatches in his brain. The scene dissolves again, and, to our surprise, we view Mrs. Henry, down on hands and knees, scrubbing paint from the floor. The camera pans to Henry, now occupying the easy chain, and reading a book entitled “How To Be Happy Though Married”. He barks an order to the wife to scrub the woodwork next. The wife throws down the scrub=brush, and is about to rise in protest to Henry’s treatment of her – when a whip cracks over her back, making her resume her scrubbing position at double the tempo. The camera returns to Henry, revealing that just behind him stands an even larger male robot, controlling the whip cracking at Henry’s command, while Henry smiles happily to the audience for the fade out.

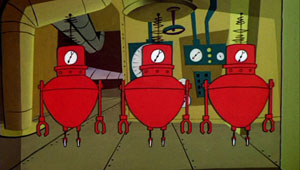

Lighter Than Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 12/17/60 – Friz Freleng, dir.), is probably the oddest excuse for a visit from Yosemite Sam ever conceived – as a space alien. Announcing himself as “Yosemite Sam of Outer Space” (why would a spaceman assume the name of an American national park??), his saucer lands in a city dump, on an expedition to bring back an Earth specimen. It’s hard to tell if this objective is to be accomplished dead or alive, as Sam seems to change tactics at will between capture schemes and efforts to destroy his quarry altogether. His target of course becomes Bugs, who resides in the junkyard, complaining of the neighborhood becoming really run down, but utilizing the numerous discarded items of machinery and technology in the junkyard to his own advantage – including a mechanized metal doorway covering the entrance to his rabbit hole. Yosemite commands a small squad of robots, and sends out as his first minion a canister-shaped robot on wheels. The metal man lifts the lid on Bugs’ hole and peers in, giving Bugs the feeling he’s being watched. To escape detection, the robot hides among trash cans. Bugs spots the newcomer, and assumes a new trash can has been added – so dumps a pail full of trash into the robot’s head. After Bugs leaves, the robot is incapacitated by coughing jags at the trash clogging his inner systems. Yosemite growls at having sent such a minion to perform his task, cursing that he’s “the dumbest robot I’ve got.” Sam calls out his “demolition squad” – a trio of larger red robots, each carrying a load of explosives. The squad clanks a metallic salute to their leader, and is off down the ramp from the ship. Bugs finally takes note of the saucer, and realizes an invasion is in progress. Bugs jumps into what looks like a ship’s deck funnel, a sign above it identifying the hole as a “shelter”. (Was Bugs expecting to have to “duck and cover”?) The demolition robots toss into the funnel their loads of explosives, then attempt to retreat to the safety of the space ship. Bugs returns to the surface via his rabbit hole, and adds one more object into the funnel – a large magnet. The three retreating robots are pulled backwards by the magnetic attraction, falling into the shelter funnel, where the explosive charges do their work to obliterate the robots instead of Bugs. A Red Cross robot, closely resembling Chuck Jones’ cleaning robot from “Dog-Gone Modern” (1939), sweeps up the squad’s debris.

Lighter Than Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 12/17/60 – Friz Freleng, dir.), is probably the oddest excuse for a visit from Yosemite Sam ever conceived – as a space alien. Announcing himself as “Yosemite Sam of Outer Space” (why would a spaceman assume the name of an American national park??), his saucer lands in a city dump, on an expedition to bring back an Earth specimen. It’s hard to tell if this objective is to be accomplished dead or alive, as Sam seems to change tactics at will between capture schemes and efforts to destroy his quarry altogether. His target of course becomes Bugs, who resides in the junkyard, complaining of the neighborhood becoming really run down, but utilizing the numerous discarded items of machinery and technology in the junkyard to his own advantage – including a mechanized metal doorway covering the entrance to his rabbit hole. Yosemite commands a small squad of robots, and sends out as his first minion a canister-shaped robot on wheels. The metal man lifts the lid on Bugs’ hole and peers in, giving Bugs the feeling he’s being watched. To escape detection, the robot hides among trash cans. Bugs spots the newcomer, and assumes a new trash can has been added – so dumps a pail full of trash into the robot’s head. After Bugs leaves, the robot is incapacitated by coughing jags at the trash clogging his inner systems. Yosemite growls at having sent such a minion to perform his task, cursing that he’s “the dumbest robot I’ve got.” Sam calls out his “demolition squad” – a trio of larger red robots, each carrying a load of explosives. The squad clanks a metallic salute to their leader, and is off down the ramp from the ship. Bugs finally takes note of the saucer, and realizes an invasion is in progress. Bugs jumps into what looks like a ship’s deck funnel, a sign above it identifying the hole as a “shelter”. (Was Bugs expecting to have to “duck and cover”?) The demolition robots toss into the funnel their loads of explosives, then attempt to retreat to the safety of the space ship. Bugs returns to the surface via his rabbit hole, and adds one more object into the funnel – a large magnet. The three retreating robots are pulled backwards by the magnetic attraction, falling into the shelter funnel, where the explosive charges do their work to obliterate the robots instead of Bugs. A Red Cross robot, closely resembling Chuck Jones’ cleaning robot from “Dog-Gone Modern” (1939), sweeps up the squad’s debris.

Yosemite calls for his “indestructible tank” – a sort of a wheeled metal cold cream jar, in which Sam rides out of the saucer, peering through a glass window with a protective sliding metal shield. Bugs, however, is at the ready with a strange sort of rolling forklift, utilizing a pair of robotic hands in its underbelly to manipulate or lift objects below the vehicle. Bugs positions his forklift directly over the tank, and matches speed with it. The robotic hands then unscrew the top of the tank like a jar lid, and drop in a stick of TNT, replacing the lid again with a twist. From inside, Sam unscrews the lid, dumping out the dynamite. The robot hands repeat the action to drop back in the dynamite stick, but this time secure the tank lid in place with the use of a rivet gun. In a gag which was a repeating favorite at Warners’, Sam desperately tries to hammer loose the rivets one by one from the inside, as time ticks down on the lit dynamite fuse. Of course, the explosion occurs a split second before the last rivet can be removed.

Yosemite calls for his “indestructible tank” – a sort of a wheeled metal cold cream jar, in which Sam rides out of the saucer, peering through a glass window with a protective sliding metal shield. Bugs, however, is at the ready with a strange sort of rolling forklift, utilizing a pair of robotic hands in its underbelly to manipulate or lift objects below the vehicle. Bugs positions his forklift directly over the tank, and matches speed with it. The robotic hands then unscrew the top of the tank like a jar lid, and drop in a stick of TNT, replacing the lid again with a twist. From inside, Sam unscrews the lid, dumping out the dynamite. The robot hands repeat the action to drop back in the dynamite stick, but this time secure the tank lid in place with the use of a rivet gun. In a gag which was a repeating favorite at Warners’, Sam desperately tries to hammer loose the rivets one by one from the inside, as time ticks down on the lit dynamite fuse. Of course, the explosion occurs a split second before the last rivet can be removed.

Sam sends another robot, cubically shaped and with a loudspeaker voice capacity, into Bugs’ hole, referring to the device as a “robot ferret”. Bugs is busy with his screwdrivers, constructing a device of his own, and commenting how handy all the war surplus stuff lying around in the junkyard is in such a situation. The “ferret” meets with a robot roughly shaped to resemble Bugs himself, also with voice capacity, who greets him with a metallic and deliberately-pronounced “What’s up, doc?” When the ferret pulls a space gun on the robot rabbit and demands he surrender, the rabbit says he will come along on one condition – that the ferret not press a red button on the rabbit’s chest. “No Earth robot is going to tell me what button I can press. I’m a-pressin”, boasts the ferret. The button triggers a jack-in-the-box style spring from the rabbit’s belly, smacking the ferret with a block of solid metal from within. Sam hauls up the ferret – reduced to loose parts hanging together by wires. Sam’s frustration has reached its peak, and Sam returns to the ship, manipulating controls within to aim a huge space cannon at Bugs’ hole. He threatens Bugs to surrender or be blasted to kingdom come. Bugs is, however, inventing again, constructing a robotic skeleton framework armed with a ticking time bomb, over which he places a rabbit costume and mask. He sends the robot out in surrender, hopping up the ramp to the ship. Sam takes off into the heavens, while Bugs returns to his rabbit hole, tuning in a milutary-style short wave radio receiver until he conveniently locates a frequency allowing him to listen in on the goings on between Sam and a commander to whom he delivers the Earth prisoner. “Step forward” orders Sam’s commander, as the ticking of the robot rabbit is heard on the receiver. “What have you got to say for yourself?”, demands the commander. All we hear is the timed explosion. The potentate replies, “Those Earth creatures, always shooting off their mouths!” Bugs giggles, then tunes his receiver set to another channel, closing with, “I wonder if ‘Amos ‘n’ Andy’ is on yet?” (The famous radio duo had in fact just left the airwaves only a short time before this cartoon premiered – indicating the delay and backlog between production dates and release dates in the studio’s films, likely diluting the effectiveness of the curtain line for its original audiences.)

Sam sends another robot, cubically shaped and with a loudspeaker voice capacity, into Bugs’ hole, referring to the device as a “robot ferret”. Bugs is busy with his screwdrivers, constructing a device of his own, and commenting how handy all the war surplus stuff lying around in the junkyard is in such a situation. The “ferret” meets with a robot roughly shaped to resemble Bugs himself, also with voice capacity, who greets him with a metallic and deliberately-pronounced “What’s up, doc?” When the ferret pulls a space gun on the robot rabbit and demands he surrender, the rabbit says he will come along on one condition – that the ferret not press a red button on the rabbit’s chest. “No Earth robot is going to tell me what button I can press. I’m a-pressin”, boasts the ferret. The button triggers a jack-in-the-box style spring from the rabbit’s belly, smacking the ferret with a block of solid metal from within. Sam hauls up the ferret – reduced to loose parts hanging together by wires. Sam’s frustration has reached its peak, and Sam returns to the ship, manipulating controls within to aim a huge space cannon at Bugs’ hole. He threatens Bugs to surrender or be blasted to kingdom come. Bugs is, however, inventing again, constructing a robotic skeleton framework armed with a ticking time bomb, over which he places a rabbit costume and mask. He sends the robot out in surrender, hopping up the ramp to the ship. Sam takes off into the heavens, while Bugs returns to his rabbit hole, tuning in a milutary-style short wave radio receiver until he conveniently locates a frequency allowing him to listen in on the goings on between Sam and a commander to whom he delivers the Earth prisoner. “Step forward” orders Sam’s commander, as the ticking of the robot rabbit is heard on the receiver. “What have you got to say for yourself?”, demands the commander. All we hear is the timed explosion. The potentate replies, “Those Earth creatures, always shooting off their mouths!” Bugs giggles, then tunes his receiver set to another channel, closing with, “I wonder if ‘Amos ‘n’ Andy’ is on yet?” (The famous radio duo had in fact just left the airwaves only a short time before this cartoon premiered – indicating the delay and backlog between production dates and release dates in the studio’s films, likely diluting the effectiveness of the curtain line for its original audiences.)

Franken-Stymied (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 7/8/61 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – Woody Woodpecker is attempting to duck from a violent lightning storm, finding himself at the door of a spooky old castle. Inside, a mad scientist (unique in design in that his mouth is constantly full of closed teeth – even when his lips open to talk) is just bringing to life his ultimate creation – a robot with cylindrical body and head, who blows periodic smoke puffs through a stack like the Tin Man in the Wizard of Oz, and whose primary power lies in the use of hinged pincer claws serving as hands. He is not merely a robot – but a mechanical chicken-plucker. The device, however, has a one-track mind, and is constantly in search of something to pluck – beginning with the hairs of the mad doctor’s moustache. The doctor realizes he must get “Frankie” a real bird to pluck in a hurry, or become clean-shaven himself. The knocks of Woody at the door are music to his ears, as Woody’s feathers will suit Frankie fine. The doctor closes about seven types of metal doors on the castle entrance – excusing his conduct as intended “to keep the rain out.” He then introduces Woody to Frankie. “Frankly speaking”, Woody offers the robot his hand in a show of friendship. Instead of a return shake, Frankie takes Woody over his knee, and begins liberally plucking feathers out of Woody’s back. A typical chase ensues through the castle, with Frankie plucking more feathers at every turn where Woody hides. Woody catches on that the device is a chicken-plucker, and sets a lure for the robot by placing a feather on the end of a long pole.

Franken-Stymied (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 7/8/61 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – Woody Woodpecker is attempting to duck from a violent lightning storm, finding himself at the door of a spooky old castle. Inside, a mad scientist (unique in design in that his mouth is constantly full of closed teeth – even when his lips open to talk) is just bringing to life his ultimate creation – a robot with cylindrical body and head, who blows periodic smoke puffs through a stack like the Tin Man in the Wizard of Oz, and whose primary power lies in the use of hinged pincer claws serving as hands. He is not merely a robot – but a mechanical chicken-plucker. The device, however, has a one-track mind, and is constantly in search of something to pluck – beginning with the hairs of the mad doctor’s moustache. The doctor realizes he must get “Frankie” a real bird to pluck in a hurry, or become clean-shaven himself. The knocks of Woody at the door are music to his ears, as Woody’s feathers will suit Frankie fine. The doctor closes about seven types of metal doors on the castle entrance – excusing his conduct as intended “to keep the rain out.” He then introduces Woody to Frankie. “Frankly speaking”, Woody offers the robot his hand in a show of friendship. Instead of a return shake, Frankie takes Woody over his knee, and begins liberally plucking feathers out of Woody’s back. A typical chase ensues through the castle, with Frankie plucking more feathers at every turn where Woody hides. Woody catches on that the device is a chicken-plucker, and sets a lure for the robot by placing a feather on the end of a long pole.

Like holding a carrot out in front of a mule, the robot is tricked into pursuing the feather to the edge of a flight of descending stairs – and tumbles down them, lying in a pile of disassembled parts at the foot of the staircase. “Well, that fractures Frankie”, quips Woody. “Frankie is indestructible”, boasts the doctor, pushing and pulling at levers on a control panel. Frankie’s parts become electrically attracted to one another, and Frankie returns to his original assembled form. On the other side of the room, Woody spots a high voltage control and wire. He tricks Frankie into plucking at the exposed wire, blasting the robot apart again with the electric shock. The doctor jostles his levers, and Franke reassembles – with some slight problems, as his parts are now rather randomly attached in places they don’t belong. Woody sends another shockwave into Frankie – and the two engage in a game of assemble and disassemble, the robot contorting into various odd restructurings of its components like a jigsaw puzzle, assuming shapes resembling a dog, a crab, and other weird combinations including its arm attached where its nose should be. Woody finally realizes, “This is getting us strictly nowhere.” He darts up a staircase while the doctor performs a final reassembly of Frankie, then drops upon the doctor from above a pot of glue. Woody follows this with a liberal rain of feathers from a pillow, coating the doctor all over in white feathers firmly stuck to his person. One excited look by Frankie, and an inviting “Click cluck cluck” from Woody to attract him, and the doctor can see he’s in for no end of trouble. Frankie puts his instinctive abilities to work upon the new white “bird”, ignoring the doctor’s protests that he is not a chicken, and the feathers fly throughout the castle. Woody emerges from the castle still in possession of most of his plumage, the rain now having subsided, and leaves performing his own mocking impression of the robot’s walk, followed by his signature laugh.

Like holding a carrot out in front of a mule, the robot is tricked into pursuing the feather to the edge of a flight of descending stairs – and tumbles down them, lying in a pile of disassembled parts at the foot of the staircase. “Well, that fractures Frankie”, quips Woody. “Frankie is indestructible”, boasts the doctor, pushing and pulling at levers on a control panel. Frankie’s parts become electrically attracted to one another, and Frankie returns to his original assembled form. On the other side of the room, Woody spots a high voltage control and wire. He tricks Frankie into plucking at the exposed wire, blasting the robot apart again with the electric shock. The doctor jostles his levers, and Franke reassembles – with some slight problems, as his parts are now rather randomly attached in places they don’t belong. Woody sends another shockwave into Frankie – and the two engage in a game of assemble and disassemble, the robot contorting into various odd restructurings of its components like a jigsaw puzzle, assuming shapes resembling a dog, a crab, and other weird combinations including its arm attached where its nose should be. Woody finally realizes, “This is getting us strictly nowhere.” He darts up a staircase while the doctor performs a final reassembly of Frankie, then drops upon the doctor from above a pot of glue. Woody follows this with a liberal rain of feathers from a pillow, coating the doctor all over in white feathers firmly stuck to his person. One excited look by Frankie, and an inviting “Click cluck cluck” from Woody to attract him, and the doctor can see he’s in for no end of trouble. Frankie puts his instinctive abilities to work upon the new white “bird”, ignoring the doctor’s protests that he is not a chicken, and the feathers fly throughout the castle. Woody emerges from the castle still in possession of most of his plumage, the rain now having subsided, and leaves performing his own mocking impression of the robot’s walk, followed by his signature laugh.

You can watch this cartoon by clicking here.

The Robot Ringer (Paramount, Modern Madcap, Nov, 1962 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – At the Robot Exhibit of the Modern Museum of Science, a potential disaster is in the making. A robot perfectly resembling a human being in a business suit has escaped from the Exhibit (by walking upside-down on the ceiling over the curator’s head). The robot (named Barnes Baisley) does not actually think, but contains voice module which allows him to repeat any words or phrases he hears. The robot is eventually traced by a ground trail of stray nuts and bolts to the advertising agency of Binny, Winny, Mello, and Plosh, where he has fallen into step behind three yes-men advertising agents, each of whom looks like an identical duplicate of himself. The agency president is holding a “think tank” session, and the robot takes a seat along with the three ad men to plan the agency’s latest campaign. Barnes makes a good impression on the boss, by repeating his inspirational slogans of “Roll up our sleeves” and “Shoulder to the Wheel”. The museum curator enters, announcing that he has traced the robot to this location. The president treats the suggestion that a robot could be among them as “Ridiculous” – and his scoffing laughter is immediately parroted by Barnes. “Okay, Pops, pick him out”, invites the president. The curator looks at the quartet of identical, motionless men in business suits, then responds, “I can’t tell. They all look like robots.” The insulted president order the curator out, but Barnes’ voice is heard before his leaving, so the curator knows he’s on the right track. The curator tries a simple test of smacking one of the businessmen on the head with a large mallet, hoping to hear a metallic clank. Instead, he produces an unconscious agent. “You goofed”, says the president. “So, I’m entitled to a mistake, no?” responds the curator.

The Robot Ringer (Paramount, Modern Madcap, Nov, 1962 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – At the Robot Exhibit of the Modern Museum of Science, a potential disaster is in the making. A robot perfectly resembling a human being in a business suit has escaped from the Exhibit (by walking upside-down on the ceiling over the curator’s head). The robot (named Barnes Baisley) does not actually think, but contains voice module which allows him to repeat any words or phrases he hears. The robot is eventually traced by a ground trail of stray nuts and bolts to the advertising agency of Binny, Winny, Mello, and Plosh, where he has fallen into step behind three yes-men advertising agents, each of whom looks like an identical duplicate of himself. The agency president is holding a “think tank” session, and the robot takes a seat along with the three ad men to plan the agency’s latest campaign. Barnes makes a good impression on the boss, by repeating his inspirational slogans of “Roll up our sleeves” and “Shoulder to the Wheel”. The museum curator enters, announcing that he has traced the robot to this location. The president treats the suggestion that a robot could be among them as “Ridiculous” – and his scoffing laughter is immediately parroted by Barnes. “Okay, Pops, pick him out”, invites the president. The curator looks at the quartet of identical, motionless men in business suits, then responds, “I can’t tell. They all look like robots.” The insulted president order the curator out, but Barnes’ voice is heard before his leaving, so the curator knows he’s on the right track. The curator tries a simple test of smacking one of the businessmen on the head with a large mallet, hoping to hear a metallic clank. Instead, he produces an unconscious agent. “You goofed”, says the president. “So, I’m entitled to a mistake, no?” responds the curator.

The president suggests a creative thinking session among the remaining three agents, with the one who can’t think to be outed as the robot. When the president tells them to think up slogans for a toothpaste campaign, the two live agents bicker over various phrases, some featuring the words “filter out” and others involving “cavities”. Barnes combines the two phrases for “Filter out cavities”, and is credited as the most creative thinker. The curator tries to further limit the field by applying the mallet test to one of the remaining two others – and knocks another live agent unconscious. While everyone else is looking at the downed agent on the floor, Barnes walks up onto the ceiling again, repeating “I’m Barnes Baisley” directly over the head of the remaining live agent. “That’s him” says the curator, turning to look at the agent instead of Barnes. A brief fight ensues, and the curator attempts to carry the agent off, until the agent finally speaks up and states his name is Dick Whittington. “I beg your pardon”, says the curator, unceremoniously dropping him onto the floor. The president meanwhile has taken Barnes under his wing, calling him “cool under fire” and impressed with how he handled the meeting, To the curator’s surprise, Barnes is set up in his own office as creative director. He continues to handle himself to the agency’s advantage, as employees spend the afternoon running choices between pairs of ideas past him, with Barnes alwats repeating what infallibly appears to be the right choice between the alternate options. The curator is left locked out, pounding on the door to have someone give him back his robot. The president seizes him up, and orders him to lay off, stating that Barnes is the best creative director they’ve ever had. “And best of all, he never goes out to lunch!”

The president suggests a creative thinking session among the remaining three agents, with the one who can’t think to be outed as the robot. When the president tells them to think up slogans for a toothpaste campaign, the two live agents bicker over various phrases, some featuring the words “filter out” and others involving “cavities”. Barnes combines the two phrases for “Filter out cavities”, and is credited as the most creative thinker. The curator tries to further limit the field by applying the mallet test to one of the remaining two others – and knocks another live agent unconscious. While everyone else is looking at the downed agent on the floor, Barnes walks up onto the ceiling again, repeating “I’m Barnes Baisley” directly over the head of the remaining live agent. “That’s him” says the curator, turning to look at the agent instead of Barnes. A brief fight ensues, and the curator attempts to carry the agent off, until the agent finally speaks up and states his name is Dick Whittington. “I beg your pardon”, says the curator, unceremoniously dropping him onto the floor. The president meanwhile has taken Barnes under his wing, calling him “cool under fire” and impressed with how he handled the meeting, To the curator’s surprise, Barnes is set up in his own office as creative director. He continues to handle himself to the agency’s advantage, as employees spend the afternoon running choices between pairs of ideas past him, with Barnes alwats repeating what infallibly appears to be the right choice between the alternate options. The curator is left locked out, pounding on the door to have someone give him back his robot. The president seizes him up, and orders him to lay off, stating that Barnes is the best creative director they’ve ever had. “And best of all, he never goes out to lunch!”

Nuts and Volts (Warner, Speedy Gonzalez, 4/25/64 – Friz Freleng, dir.) – Speedy is running Sylvester ragged around the old hacienda, leaving him so exhausted that a strong blow of air from Speedy’s lips can knock the cat backwards onto the floor. As Sylvester lies huffing and puffing, he spots a handbill someone slides under the front door. “Automation is here. Modernize your home. Let the Machine do the work.” “Why not?”, observes Sylvester, with a sinister grin.

Nuts and Volts (Warner, Speedy Gonzalez, 4/25/64 – Friz Freleng, dir.) – Speedy is running Sylvester ragged around the old hacienda, leaving him so exhausted that a strong blow of air from Speedy’s lips can knock the cat backwards onto the floor. As Sylvester lies huffing and puffing, he spots a handbill someone slides under the front door. “Automation is here. Modernize your home. Let the Machine do the work.” “Why not?”, observes Sylvester, with a sinister grin.

His first purchase is of an electric eye, which he installs on either side of Speedy’s mousehole, after which he disappears off screen. Speedy emerges, noting the beam of light across his path. “How you like thees? The pussy cat’s got brains.” Speedy crosses the line, breaking the beam. On the opposite side of the room, a panel flips open on a box labeled “Mouse Control”. Inside is Sylvester, who is launched by a spring into a flying pounce across the room. His trajectory needs work, as he smashes headfirst into the wall above Speedy. “You meesed”, Speedy observes in a taunt.

His first purchase is of an electric eye, which he installs on either side of Speedy’s mousehole, after which he disappears off screen. Speedy emerges, noting the beam of light across his path. “How you like thees? The pussy cat’s got brains.” Speedy crosses the line, breaking the beam. On the opposite side of the room, a panel flips open on a box labeled “Mouse Control”. Inside is Sylvester, who is launched by a spring into a flying pounce across the room. His trajectory needs work, as he smashes headfirst into the wall above Speedy. “You meesed”, Speedy observes in a taunt.

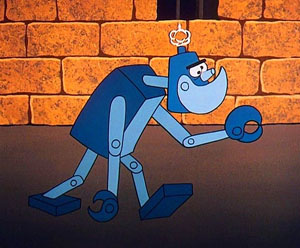

Sylvester next builds from blueprints a robot to do his dirty work. It is the same cylinder-stack robot used in Bugs Bunny’s “Robot Rabbit”, minus one light bulb in his forehead. The robot lies in wait for Speedy around a corner from his mousehole, but Speedy creeps up behind him from another hole, and gives him the trademark yell of “Yee-hah!”, sending the robot jumping to the ceiling, losing a few nuts and bolts in the collision. The robot begins to chase Speedy all over the house, while Sylvester cranks up his speed to “Super Sonic” on a master control panel. The robot keeps pace with Speedy, until Speedy darts back to his mousehole. Sylvester, viewing on a TV screen, pulls hard upon an emergency lever on the controls to apply the robot’s brakes, but too late. A crash is heard, followed by the entrance on the TV monitor of a small cylindrical robot equipped with an automobile-style tow chain. The dismantled parts of the larger robot are carted in tow back to Sylvester, who mutters, “Stupid robot.” Sylvester engages in major repairs, some parts of the robot held together with Band-Aids.

Sylvester next builds from blueprints a robot to do his dirty work. It is the same cylinder-stack robot used in Bugs Bunny’s “Robot Rabbit”, minus one light bulb in his forehead. The robot lies in wait for Speedy around a corner from his mousehole, but Speedy creeps up behind him from another hole, and gives him the trademark yell of “Yee-hah!”, sending the robot jumping to the ceiling, losing a few nuts and bolts in the collision. The robot begins to chase Speedy all over the house, while Sylvester cranks up his speed to “Super Sonic” on a master control panel. The robot keeps pace with Speedy, until Speedy darts back to his mousehole. Sylvester, viewing on a TV screen, pulls hard upon an emergency lever on the controls to apply the robot’s brakes, but too late. A crash is heard, followed by the entrance on the TV monitor of a small cylindrical robot equipped with an automobile-style tow chain. The dismantled parts of the larger robot are carted in tow back to Sylvester, who mutters, “Stupid robot.” Sylvester engages in major repairs, some parts of the robot held together with Band-Aids.

The robot is sent on another chase after the mouse, who taunts Sylvester on the monitor screen by peering directly into the lens of the TV camera and waving, “Hello, pussy cat.” Once again, the robot pursues, until Speedy brings the chase full circle back to the camera lens, waves Sylvester another hello on screen, then disappears to one side. The robot follows, heading straight for the camera, as Sylvester utters, “Oh, no.” From behind the control panel, the robot bursts through in the flesh – er, tin – demolishing the controls and Sylvester too. In rolls the towing robot again, hauling off not only the robot wreckage, but Sylvester snarled up within it.

Once more, Sylvester engages in lengthy repairs of both the robot and controls, threatening the robot that one more slip-up will result in him being thrown upon the scrap heap. This time, Sylvester uses the robot more as an appliance than as a brain under its own power. In place of one arm, Sylvester has installed the equivalent of a Roto-Rooter extendable sewer cable, on the end of which is attached a robot hand, holding a lit stick of dynamite. Sylvester operates a crank in the robot’s back, extending the device’s cable into Speedy’s mousehole. Speedy retreats deeper into the walls as the TNT approaches, then leads the cable on a merry maze in and out of the labyrinth of interior walls. Before you know it, Speedy has emerged from another hole, and is standing directly behind Sylvester, as the dynamite also approaches. “You busy, pussy cat?”. Speedy inquires. Sylvester turns around, just in time to see the robot claw with the dynamite appear about two inches in front of his face. Seeking whatever protection he can get, Sylvester opens a back hatch in the robot’s main cylinder, and leaps in, slamming the hatch behind him. Speedy reaches over to open the hatch again, allowing the robot hand to toss the dynamite inside too, then shuts the hatch door. BOOM! With Sylvester now scrunched into the top half of the robot’s body, replacing the creation’s head, we get a repeat of the same gag from “Robot Rabbit” of the base of the robot’s central cylinder falling out, briefly revealing the robot’s engine, and Sylvester pulling it back up into place with the robot’s arms, embarrassed as if caught with his pants down. In the final scene, Sylvester makes good on his threat to toss the robot into the trash, then grabs up a club, vowing to deal with Speedy in his own manner. He never gets the chance, as he is greeted at the door by a new arrival – a mechanical dog, whose large metal jaws chomp at Sylvester’s tail like a bear trap. Sitting at the control panel and watching this on the monitor is Speedy, who states to the audience, “Hey, I dig this electrical-tonics type stuff.”

Once more, Sylvester engages in lengthy repairs of both the robot and controls, threatening the robot that one more slip-up will result in him being thrown upon the scrap heap. This time, Sylvester uses the robot more as an appliance than as a brain under its own power. In place of one arm, Sylvester has installed the equivalent of a Roto-Rooter extendable sewer cable, on the end of which is attached a robot hand, holding a lit stick of dynamite. Sylvester operates a crank in the robot’s back, extending the device’s cable into Speedy’s mousehole. Speedy retreats deeper into the walls as the TNT approaches, then leads the cable on a merry maze in and out of the labyrinth of interior walls. Before you know it, Speedy has emerged from another hole, and is standing directly behind Sylvester, as the dynamite also approaches. “You busy, pussy cat?”. Speedy inquires. Sylvester turns around, just in time to see the robot claw with the dynamite appear about two inches in front of his face. Seeking whatever protection he can get, Sylvester opens a back hatch in the robot’s main cylinder, and leaps in, slamming the hatch behind him. Speedy reaches over to open the hatch again, allowing the robot hand to toss the dynamite inside too, then shuts the hatch door. BOOM! With Sylvester now scrunched into the top half of the robot’s body, replacing the creation’s head, we get a repeat of the same gag from “Robot Rabbit” of the base of the robot’s central cylinder falling out, briefly revealing the robot’s engine, and Sylvester pulling it back up into place with the robot’s arms, embarrassed as if caught with his pants down. In the final scene, Sylvester makes good on his threat to toss the robot into the trash, then grabs up a club, vowing to deal with Speedy in his own manner. He never gets the chance, as he is greeted at the door by a new arrival – a mechanical dog, whose large metal jaws chomp at Sylvester’s tail like a bear trap. Sitting at the control panel and watching this on the monitor is Speedy, who states to the audience, “Hey, I dig this electrical-tonics type stuff.”

The last clanks and clatter of theatrical shorts, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

When in doubt, include it anyway. To my eye, the adult alien in “Outer Space Visitor” doesn’t seem to display many unequivocally mechanical traits apart from the two dials on its thorax, which might just as well be some kind of alien navel. Junior is wearing a diaper, but on the other hand he might just be leaking oil. Too bad the professor didn’t take any biopsies to determine whether Junior was organic or inorganic while he was jabbering into the interpreting machine (which in “Plan 9 from Outer Space” is called a “dictorobitary”).

But the metal monster in “The Mysterious Package”, on the other hand, is definitely a robot: made of metal (as the narrator keeps telling us), containing nuts, bolts and springs, emitting an energy beam from its eye, etc. That it turns out to be an old man under a witch’s curse doesn’t make it any less of a robot; “For 100 years I’ve lived in lonely isolation as a metal monster,” he says, not “…encased inside a metal monster.” A similar situation occurs in Season 5 of Winx Club, when the three witches known as the Trix put a spell on Tecna’s phone; and when she uses an app on it to search the Magical Archive for the Sirenix Book, she turns into a robot for the better part of an episode. The other Winx eventually break the spell, but the experience of having been a robot was very traumatic for Tecna, and thereafter she becomes more demonstrative and open with her feelings.

The ad agency in “The Robot Ringer” evidently only hires Yale alumni, to judge by the prominence of the “Boola Boola” fight song in the soundtrack.

Small Wonder! “She’s fantastic! Made of plastic! Microchips here and there! She’s a Small Wonder! Brings love and laughter everywhere!” Why can I remember all the words to the theme song, when I can’t remember where I put my glasses?

“Case of the Red-Eyed Ruby” (Lantz/Universal, Inspector Wiloughby, 28/11/61 — Paul J. Smith, dir.) provides an example of a flesh-and-blood human enclosed in a robotic exoskeleton. Inspector Willoughby wants to prevent the red-eyed ruby — a precious gem mounted in the forehead of a green idol in the tomb of King Tut-Tut-Almond — from falling into the hands of international jewel thief Yeggs Benedict. The green idol comes to life to torment Yeggs, but it’s really the inspector operating it from within via a system of levers. Does this count as a robot, or is it merely a glorified puppet? As I said: when in doubt, include it anyway.

The two Warners and Franken-Stymied are pretty good. Ain’t ever seen the others, but I’ll do that eventually.

The “Beany and Cecil” episode “Invasion of Earth by Robots” (1/6/1962) revolves around, well, exactly what the title says. Although in actuality the mostly harmless alien robots only stop at Earth to have a picnic, with no ambitions of conquering the world. Even the robotic picnic ants they unleash upon the Earth are civil enough to return voluntarily to the robots’ flying saucer at the end.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qbDZBpK-0E0

“Nestasni robot” (Zagreb Film, 16/6/56 — Dusan Vukotic, dir.) has been rendered in English as “The Disobedient Robot”, “The Playful Robot”, or simply “Robot”. A cranially endowed scientist invents a robot to tidy up his laboratory while he dozes off in his ultramodern easy chair. The robot is bored by this drudgery, so it mixes up some spare parts in a cocktail shaker to produce two small robots to do its work. The little robots have other ideas, preferring to play music and otherwise screw around as the mess in the lab gets worse and worse. The scientist awakens and makes some adjustments to the robots’ antennae, turning them into lean, mean cleaning machines.

Everything about this cartoon seems to have been designed to be as modern as possible, so that it’s become as quaint and outdated as all 1950s science fiction. It’s also much less abstract than Vukotic’s later work, which as far as I’m concerned is a plus.

YOSEMITE SAM OF OUTER BOOM!!! SPACE?😂😂😂