In our final phase upon the subject of automatons in animation, we move back to the silver screen, for a survey of robots’ “upgrade” from the world of short subjects into feature films. The move wasn’t a sudden phenomenon, nor even a recent one, occurring first in the films of foreign lands. Even there, it did not directly track the growth of the medium in either low budget live-action horror or sci-fi formats from Japan, nor in shorter Manga and anime form, but remained restricted to sporadic appearances, with shorter films discussed in prior pages of these articles far exceeding protracted screenplays in number. Perhaps the world wasn’t considered quite ready to accept looming but unfeeling behemoths in larger doses. Or perhaps the problem was the tradition begun with Disney feature animation, of need to touch the heartstrings of the audience for lasting film appeal – a difficult task if your central figure, much as the Tin Woodman, is lacking an actual heart in the first place. Thus, many years would pass between rare instances where robots would take center stage in select scripts, and what appearances there were more likely cast them as unthinking warrior adversaries or as comic relief. Today’s first installment of two, however, climaxes with a well-crafted instance where a mechanical man not only maintains central prominence throughout a film, but develops heart-felt sensitivity, and becomes a real hero.

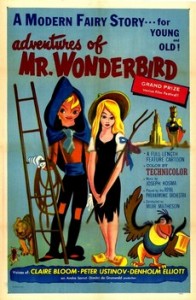

The Curious Adventures of Mr. Wonderbird (1952) is a French feature known by at least half a dozen other names, including “The Shepardess and the Chimney Sweep”. Taking only minimal inspiration from a story by Hans Christian Andersen, this convoluted tale deviates into a surreal view of a futuristic kingdom full of mechanized inventions and weaponry, ruled over by a despot king, which some have compared to the layout for a video-game scenario, while this author prefers to compare it to a non-stop nightmare. Its principal “human” characters are indeed a question mark, placing the whole story at a level where it is impossible to discern between reality and dementia, as the Shepardess and Chimney Sweep are persona-less images somehow come to life off of paintings in the King’s chambers, yet the supposed real-life King allegedly wants the Shepardess as his bride – presuming that there must be a real version of her somewhere who modeled for the painting. Yet, any real-life Shepardess or Chimney Sweep are never seen. To make things even stranger, the Shepardess is also lusted after by a painted version of the King himself, who also comes to life, and quickly disposes of the real king via a trap door leading to a fatal drop that the King himself installed to get rid of inwanted or unneeded members of his court and kingdom. The painted King takes over in place of the real King (who was nearly as bad anyway, so why the need for the substitution?), and so the entire remainder of the script is played out by doppelgangers out of a paintbrush! Sort of distances you from any feeling of relating to the characters’ plights or foibles, doesn’t it?

The Curious Adventures of Mr. Wonderbird (1952) is a French feature known by at least half a dozen other names, including “The Shepardess and the Chimney Sweep”. Taking only minimal inspiration from a story by Hans Christian Andersen, this convoluted tale deviates into a surreal view of a futuristic kingdom full of mechanized inventions and weaponry, ruled over by a despot king, which some have compared to the layout for a video-game scenario, while this author prefers to compare it to a non-stop nightmare. Its principal “human” characters are indeed a question mark, placing the whole story at a level where it is impossible to discern between reality and dementia, as the Shepardess and Chimney Sweep are persona-less images somehow come to life off of paintings in the King’s chambers, yet the supposed real-life King allegedly wants the Shepardess as his bride – presuming that there must be a real version of her somewhere who modeled for the painting. Yet, any real-life Shepardess or Chimney Sweep are never seen. To make things even stranger, the Shepardess is also lusted after by a painted version of the King himself, who also comes to life, and quickly disposes of the real king via a trap door leading to a fatal drop that the King himself installed to get rid of inwanted or unneeded members of his court and kingdom. The painted King takes over in place of the real King (who was nearly as bad anyway, so why the need for the substitution?), and so the entire remainder of the script is played out by doppelgangers out of a paintbrush! Sort of distances you from any feeling of relating to the characters’ plights or foibles, doesn’t it?

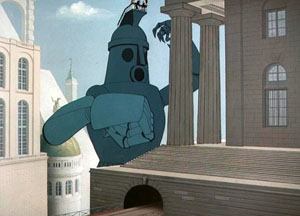

Wonderbird, an anthropomorphic talking crow, magpie, or whatever, seems to be the only real-life character remaining who matters to the rest of the picture, befriending the two escaping painted lovers for no apparent reason except hatred of the king, and rescuing them from every peril on the descent from the King’s 1,999th floor apartment to the surface below, and even below that into underground dungeons and rivers. After what seems an endless stream-of-consciousness pursuit by the painted King and his troops and police, the Shepardess is finally captured and taken by the King aboard the head of a humongous metal robot who stands almost as tall as the King’s apartment tower. he humanoid-shaped robot is modeled much in the manner of the uniform of a Roman gladiator, with a helmet-shaped head atop which rests a flat platform surrounded on three sides by small metal railings. Its limbs are manipulated from a separate control station at about neck level, where a member of the King’s guard operates various complicated motors, levers, and gears for each movement. The King himself stands atop the flat platform with the Shepardess – an amazing feat, considering they wear no seat belt or restraint, suggesting outstanding developments in gyroscopic self-leveling and vibration control. In a final assault, Wonderbird takes over the control station of the robot, and begins randomly pulling levers and turning control wheels, claiming to be mechanically inclined. The robot’s arms raise, and begin swatting at the platform where the King stands (taking no especial care to avoid blows to the Shepardess, and leaving the platform railings well bent). The King is temporarily jostled down stairs leading to the platform, while Wonderbird’s further efforts cause the robot to smash wildly at every tower and spire in the kingdom, ultimately leveling them in a shot of collapse seen at a distance of miles away. There seems to be little concern for townsfolk of the kingdom seen in previous shots, who undoubtedly are being buried in the rubble below, only a few select principal characters seeming to be accounted for as having already escaped the kingdom’s perimeters. The King somehow crawls back up the stairs, but the robot’s hand finally hits its mark, picking the King up by the back of his royal trappings, and depositing him into the palm of one robotic hand. Then, the robot reveals from nowhere an added power. A beam of light from one eye focuses on the King. Then, a powerful fan begins to blow from behind the retina opening of the robot’s eye, which simply blows the King away through the clouds and into the stratosphere. Bizarre!

Wonderbird, an anthropomorphic talking crow, magpie, or whatever, seems to be the only real-life character remaining who matters to the rest of the picture, befriending the two escaping painted lovers for no apparent reason except hatred of the king, and rescuing them from every peril on the descent from the King’s 1,999th floor apartment to the surface below, and even below that into underground dungeons and rivers. After what seems an endless stream-of-consciousness pursuit by the painted King and his troops and police, the Shepardess is finally captured and taken by the King aboard the head of a humongous metal robot who stands almost as tall as the King’s apartment tower. he humanoid-shaped robot is modeled much in the manner of the uniform of a Roman gladiator, with a helmet-shaped head atop which rests a flat platform surrounded on three sides by small metal railings. Its limbs are manipulated from a separate control station at about neck level, where a member of the King’s guard operates various complicated motors, levers, and gears for each movement. The King himself stands atop the flat platform with the Shepardess – an amazing feat, considering they wear no seat belt or restraint, suggesting outstanding developments in gyroscopic self-leveling and vibration control. In a final assault, Wonderbird takes over the control station of the robot, and begins randomly pulling levers and turning control wheels, claiming to be mechanically inclined. The robot’s arms raise, and begin swatting at the platform where the King stands (taking no especial care to avoid blows to the Shepardess, and leaving the platform railings well bent). The King is temporarily jostled down stairs leading to the platform, while Wonderbird’s further efforts cause the robot to smash wildly at every tower and spire in the kingdom, ultimately leveling them in a shot of collapse seen at a distance of miles away. There seems to be little concern for townsfolk of the kingdom seen in previous shots, who undoubtedly are being buried in the rubble below, only a few select principal characters seeming to be accounted for as having already escaped the kingdom’s perimeters. The King somehow crawls back up the stairs, but the robot’s hand finally hits its mark, picking the King up by the back of his royal trappings, and depositing him into the palm of one robotic hand. Then, the robot reveals from nowhere an added power. A beam of light from one eye focuses on the King. Then, a powerful fan begins to blow from behind the retina opening of the robot’s eye, which simply blows the King away through the clouds and into the stratosphere. Bizarre!

Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon (Toei Animation, 3/20/65) is another far-out concept that gets confusing, but is slightly more satisfying than the previous film. A Japanese import, its animation style is somewhat limited, in the manner of a high-budgeted contemporary TV project, with simplified flat character design. However, it is surely not anime, trying for a more universally appealing Western look in attempt to achieve an international audience. It was, however, a box-office failure, and the last Japanese feature to be imported to the U.S. for some time.

Gulliver’s Travels Beyond the Moon (Toei Animation, 3/20/65) is another far-out concept that gets confusing, but is slightly more satisfying than the previous film. A Japanese import, its animation style is somewhat limited, in the manner of a high-budgeted contemporary TV project, with simplified flat character design. However, it is surely not anime, trying for a more universally appealing Western look in attempt to achieve an international audience. It was, however, a box-office failure, and the last Japanese feature to be imported to the U.S. for some time.

It begins with what can only be described as a homage to Fleischer, appearing to replicate the opening shipwreck sequence of Fleischer’s “Gulliver” from 1939. In fact, we are in a theater which seems to be running a revival of the very same feature. A young boy named Ricky, homeless ad down on his luck, has sneaked into the movie without a ticket, and is thrown out into the alley forcibly by an usher. He slowly strides away down a back street, grumbling about his misfortune, and scoffing at a line of the feature in which Gulliver, adrift at sea, vowed to never give up hope. Ricky does not watch where he is going, and is almost run down by a truck while crossing a dark street. He lies momentarily motionless and prone on the adjoining sidewalk. (Yes, it’s the opportunity for the whole story to be a dream sequence.) Suddenly, he meets a talking wind-up toy soldier in a trash dumpster, and a small chubby dog with a large appetite, also talking, named Pudge. The three down-and-outers form a friendship, and take temporary refuge in an amusement park, where they are eventually pursued by a trio of security guards. They make an escape on a large skyrocket from a pyrotechnics display, crashing in a dark forest. They encounter a remote cottage within the woods, inhabited by, of all people, a now-elderly Gulliver. Gulliver has been many places in his world wanderings, but has never given up hope of exploring yet new horizons – and has set his sights upon the stars, and a distant world which he has sighted in a self-built telescope, which he calls the Star of Hope. He has spent many years constructing a rocket ship, but time and age have caught up with him, and now he is not sure he can manage the voyage on his own. Ricky and his friends volunteer as a crew, and remind him of his own motto to never give up hope. After rigorous training, the “crew” measures up to Gulliver’s needs, and are taken along for the ride.

In outer space, their rocket encounters three ships from a small planetoid adjoining the Star of Hope, which use tractor beams to force it to land. They are subjected to examination to determine what sort of “robots” they are, by a race of beings who appear to be robotic themselves. The lead ship which captured them is piloted by a gracious princess-bot, who apologizes after finding them harmless, and invites them to a royal dinner (largely inedible to humans). However, the royal court tell of what lies on the “Star of Hope”, which they more appropriately refer to as a star of evil. The planet was their former home, but their scientists developed a self-replicating race of robots to perform all their labor and leave them in a life of total leisure. The labor robots are shaped much like giant inkwells, with small glowing eye-pods that rotate around the bottle-neck that forms their heads. The robots develop intelligence, and awareness of their own might and superiority, and take over the planet, casting most of the population into space. Those who survived have collected on the planetoid, but remain under periodic aerial attack from the robot world. Such an attack comes right on cue, by a ship that at first propels itself with what appears to be a rotating steel umbrella. The umbrella folds into the shape of a missile shell, and, in what may be another Fleischer homage, dives upon the planetoid much in the manner of the Bulleteers’ car from the Superman cartoon of the same title. After destruction of many buildings, and toppling of all the royal defensive cannons, the ship makes off with two of our characters who were hiding within objects at the royal court – Pudge, and the Princess.

In outer space, their rocket encounters three ships from a small planetoid adjoining the Star of Hope, which use tractor beams to force it to land. They are subjected to examination to determine what sort of “robots” they are, by a race of beings who appear to be robotic themselves. The lead ship which captured them is piloted by a gracious princess-bot, who apologizes after finding them harmless, and invites them to a royal dinner (largely inedible to humans). However, the royal court tell of what lies on the “Star of Hope”, which they more appropriately refer to as a star of evil. The planet was their former home, but their scientists developed a self-replicating race of robots to perform all their labor and leave them in a life of total leisure. The labor robots are shaped much like giant inkwells, with small glowing eye-pods that rotate around the bottle-neck that forms their heads. The robots develop intelligence, and awareness of their own might and superiority, and take over the planet, casting most of the population into space. Those who survived have collected on the planetoid, but remain under periodic aerial attack from the robot world. Such an attack comes right on cue, by a ship that at first propels itself with what appears to be a rotating steel umbrella. The umbrella folds into the shape of a missile shell, and, in what may be another Fleischer homage, dives upon the planetoid much in the manner of the Bulleteers’ car from the Superman cartoon of the same title. After destruction of many buildings, and toppling of all the royal defensive cannons, the ship makes off with two of our characters who were hiding within objects at the royal court – Pudge, and the Princess.

Ricky, Gulliver, and the toy soldier vow to wage an attack on the robot star to save their friends. In provisioning their rocket for the trip, they discover that the locals have no ready supply of water, treating it as a “dangerous substance”. Gulliver whips up a condensation machine to create a supply, and believes that this “weapon” may just provide the hope for victory that they need. Upon arriving at the planet, a battle ensues as a twenty-story tall command robot orders out his fighting legions, and the planet’s factories to produce more robots. Gulliver and Ricky face off against the oncoming armada – armed with high-powered water pistols, and (produced from nowhere) an array of large inflatable water balloons of various design, filled from Gulliver’s condensation machine. Just a few drops for each robot, and they quickly short-circuit and crack to bits. The robots’ weapons further penetrate the balloons, causing water to be spread everywhere, fracturing remaining stragglers of the attacking legion. Only the master robot seems impervious to attack. But Ricky notices one of the smaller robots gunning at him from a balcony on the command robot’s side. He quickly knocks off the gunner with his water pistol, then swings on a rope to the balcony, penetrating the command robot’s interior. The large robot is in fact piloted by smaller navigation robots within, who are easily destroyed with the water jets. This leaves the command robot flailing about aimlessly at anything around him, and, though he nearly topples several structures on our heroes, the robot ultimately trips over the debris, crashing to the ground and fracturing like the others. All is still, and finally the Princess is found, hiding in a musical artifact stolen from the palace during the earlier battle. Then things get strange and unexplained, as Ricky does something risky – ribbing a few drops of water on the Princess’s metallic skin. The skin peels away, revealing a human girl within. Gulliver and Ricky announce that they somehow deduced that the planetoid’s population were really humans whom their scientists had defensively shielded in robotic form. (If that is so, then how did they survive all this time without human food or water???) These are details we’re not supposed to worry about, as, after all, the whole thing is a dream, as Ricky awakens from his sleep on the sidewalk. He finds a real toy soldier in the dumpster, and a real dog matching Pudge except for the talking, and walks back with his new companions to wherever he came from, now carrying Gulliver’s motto of never giving up hope.

Ricky, Gulliver, and the toy soldier vow to wage an attack on the robot star to save their friends. In provisioning their rocket for the trip, they discover that the locals have no ready supply of water, treating it as a “dangerous substance”. Gulliver whips up a condensation machine to create a supply, and believes that this “weapon” may just provide the hope for victory that they need. Upon arriving at the planet, a battle ensues as a twenty-story tall command robot orders out his fighting legions, and the planet’s factories to produce more robots. Gulliver and Ricky face off against the oncoming armada – armed with high-powered water pistols, and (produced from nowhere) an array of large inflatable water balloons of various design, filled from Gulliver’s condensation machine. Just a few drops for each robot, and they quickly short-circuit and crack to bits. The robots’ weapons further penetrate the balloons, causing water to be spread everywhere, fracturing remaining stragglers of the attacking legion. Only the master robot seems impervious to attack. But Ricky notices one of the smaller robots gunning at him from a balcony on the command robot’s side. He quickly knocks off the gunner with his water pistol, then swings on a rope to the balcony, penetrating the command robot’s interior. The large robot is in fact piloted by smaller navigation robots within, who are easily destroyed with the water jets. This leaves the command robot flailing about aimlessly at anything around him, and, though he nearly topples several structures on our heroes, the robot ultimately trips over the debris, crashing to the ground and fracturing like the others. All is still, and finally the Princess is found, hiding in a musical artifact stolen from the palace during the earlier battle. Then things get strange and unexplained, as Ricky does something risky – ribbing a few drops of water on the Princess’s metallic skin. The skin peels away, revealing a human girl within. Gulliver and Ricky announce that they somehow deduced that the planetoid’s population were really humans whom their scientists had defensively shielded in robotic form. (If that is so, then how did they survive all this time without human food or water???) These are details we’re not supposed to worry about, as, after all, the whole thing is a dream, as Ricky awakens from his sleep on the sidewalk. He finds a real toy soldier in the dumpster, and a real dog matching Pudge except for the talking, and walks back with his new companions to wherever he came from, now carrying Gulliver’s motto of never giving up hope.

The Great Mouse Detective (Disney, 7/2/86) appears to be the first Disney animated feature to deal in a form of early robotics. Produced on a lower budget than most Disney features, and just before the Renaissance that began with The Little Mermaid, it nevertheless turned a profit. It opens in the toy shoppe of an inventor mouse named Flaversham (voiced by Alan Young), who is presenting his daughter with a graceful mechanized wind-up dancing mouse ballerina as a gift. Suddenly, a break-in and violent confrontation takes place, as a peg-legged bat kidnaps and makes off with the girl’s father, disappearing into the night. She encounters in her search for father a Dr. Dawson, a moustached portly mouse of kindly demeanor, who escorts her to the one mouse who may be capable of solving the crime – Basil of Baker Street. It is quickly obvious that we are entering a mouse parody of the famous Sherlock Holmes stories – made even more clearly evident as we discover Basil’s home is in the basement of the actual abode of Sherlock Holmes himself (with Basil Rathbone briefly providing the voice of Sherlock, for old times sake). The trail leads to Basil’s arch-nemesis, Professor Ratigan (voiced by Vincent Price), who has had the toymaker nabbed to utilize his skills in robotics for nefarious purposes. The Mouse Queen’s Royal Jubilee is impending, and Ratigan sees opportunity for a rise in power and stature, if he can only arrange for the Queen to disappear, and a “puppet ruler” to take her place. Using bellows, hydraulics, and a ton of gears and mainsprings, it is Flaversham’s task as forced laborer to construct a life-size animatronic duplicate of the Queen, to make a presentation of Ratigan to the royal court at the Jubilee, announcing her appointment of Ratigan as Royal Consort. A funny sequence shows the robot prototype, jittering and shaking in attempting to balance a cup of tea, then sabotaged by Flaversham to toss sugar, tea, and lemon upon itself and whirl in endless circles, leaving tea stains of Ratigan’s lapel. Nevertheless, Flaverham is forced to complete the project when his daughter is kidnapped too. The plan nearly works, until Basil and Dawson, fresh from escaping a half-dozen death traps rigged to trigger simultaneously, barge in behind the velvet curtains, take over the voice-synthesizer mechanism that controls the Queen’s speech, and change the Queen robot’s tune to a string of accusations against Ratigan of committing the lowest of crimes. Basil further manipulates the robot’s mechanical controls, causing the robot to pick up Ratigan bodily and give him a wrestler’s spin over her head, then explode to reveal her metal skeleton, bulging fake eyeballs and still-speaking dentures, naming Ratigan in Latin as the true species he is – a Rat! The robot’s work is done, though it takes Basil and a wild sky chase leading to a crash and pursuit inside and out of Big Ben to cause Ratigan’s ultimate downfall.

The Great Mouse Detective (Disney, 7/2/86) appears to be the first Disney animated feature to deal in a form of early robotics. Produced on a lower budget than most Disney features, and just before the Renaissance that began with The Little Mermaid, it nevertheless turned a profit. It opens in the toy shoppe of an inventor mouse named Flaversham (voiced by Alan Young), who is presenting his daughter with a graceful mechanized wind-up dancing mouse ballerina as a gift. Suddenly, a break-in and violent confrontation takes place, as a peg-legged bat kidnaps and makes off with the girl’s father, disappearing into the night. She encounters in her search for father a Dr. Dawson, a moustached portly mouse of kindly demeanor, who escorts her to the one mouse who may be capable of solving the crime – Basil of Baker Street. It is quickly obvious that we are entering a mouse parody of the famous Sherlock Holmes stories – made even more clearly evident as we discover Basil’s home is in the basement of the actual abode of Sherlock Holmes himself (with Basil Rathbone briefly providing the voice of Sherlock, for old times sake). The trail leads to Basil’s arch-nemesis, Professor Ratigan (voiced by Vincent Price), who has had the toymaker nabbed to utilize his skills in robotics for nefarious purposes. The Mouse Queen’s Royal Jubilee is impending, and Ratigan sees opportunity for a rise in power and stature, if he can only arrange for the Queen to disappear, and a “puppet ruler” to take her place. Using bellows, hydraulics, and a ton of gears and mainsprings, it is Flaversham’s task as forced laborer to construct a life-size animatronic duplicate of the Queen, to make a presentation of Ratigan to the royal court at the Jubilee, announcing her appointment of Ratigan as Royal Consort. A funny sequence shows the robot prototype, jittering and shaking in attempting to balance a cup of tea, then sabotaged by Flaversham to toss sugar, tea, and lemon upon itself and whirl in endless circles, leaving tea stains of Ratigan’s lapel. Nevertheless, Flaverham is forced to complete the project when his daughter is kidnapped too. The plan nearly works, until Basil and Dawson, fresh from escaping a half-dozen death traps rigged to trigger simultaneously, barge in behind the velvet curtains, take over the voice-synthesizer mechanism that controls the Queen’s speech, and change the Queen robot’s tune to a string of accusations against Ratigan of committing the lowest of crimes. Basil further manipulates the robot’s mechanical controls, causing the robot to pick up Ratigan bodily and give him a wrestler’s spin over her head, then explode to reveal her metal skeleton, bulging fake eyeballs and still-speaking dentures, naming Ratigan in Latin as the true species he is – a Rat! The robot’s work is done, though it takes Basil and a wild sky chase leading to a crash and pursuit inside and out of Big Ben to cause Ratigan’s ultimate downfall.

While An American Tail (Don Bluth/Universal/Amblin, 11/21/86) was box-office boffo, during a period where quality animation was almost a Disney monopoly, it was, to my tastes, the first sign of the chink in the armor in Don Bluth’s storytelling style. After close to 80 minutes of build-up, it seemed as though Bluth didn’t have a clue as to how to wrap up his story, so opted for a “quick fix” that was too pat, too unnatural, and too unexplained to plausibly flow from what came before it. His naive, juvenile hero Fievel, who has spent most of the picture just trying to figure America out and learn to cope with it, suddenly is the only one at a public mouse rally to come up with a suggestion for ridding their community of cats. Bluth can’t even put it in words, having Fievel communicate the “idea” without a single word of dialogue, by whispering into the ear of the speaker on the podium. “We have a plan”, announces the speaker. All of a sudden, mice are raiding a pier storage warehouse for every sort of available material and contraption. No planning meeting. No discussion of feasibility. No identification of who determined where the component parts could be acquired, or even what they would be. (Fievel in fact seems to have never been anywhere near the warehouse before to even know.) Suddenly, a character with the personality of a five-year old seems to have developed into a mechanical genius, for the mice amazingly build what amounts to a giant mouse robot, with balloons for body segments, jaws that seem to have been excised from a prehistoric skeleton in storage, and a wheeled trolley for its base, loaded with fireworks for ammunition, Christened the “secret weapon.” How could Fievel possibly have come up with such a concept? This “Hail Mary to the rescue” type formula would seem to recur in other Bluth productions, proving that Bluth could develop an initial scenario, but rarely knew how to effectively wrap it up. Had we known more of his earlier work at the time, we might have noted earlier instances of this pattern developing, such as in the sudden ending of the television special “Banjo the Woodpile Cat”, or even his early work on Disney’s “The Small One”, relying for a ready-made sudden ending upon the most obvious “Hail Mary” of all.) I was not impressed with the flashy facade of his fireworks finale, and was left with a feeling of “What? That was it?” Few others at the time seemed to see it that way. Given time, the public eventually caught on in his later films, leading to the gradual demise and final failure of the studio.

While An American Tail (Don Bluth/Universal/Amblin, 11/21/86) was box-office boffo, during a period where quality animation was almost a Disney monopoly, it was, to my tastes, the first sign of the chink in the armor in Don Bluth’s storytelling style. After close to 80 minutes of build-up, it seemed as though Bluth didn’t have a clue as to how to wrap up his story, so opted for a “quick fix” that was too pat, too unnatural, and too unexplained to plausibly flow from what came before it. His naive, juvenile hero Fievel, who has spent most of the picture just trying to figure America out and learn to cope with it, suddenly is the only one at a public mouse rally to come up with a suggestion for ridding their community of cats. Bluth can’t even put it in words, having Fievel communicate the “idea” without a single word of dialogue, by whispering into the ear of the speaker on the podium. “We have a plan”, announces the speaker. All of a sudden, mice are raiding a pier storage warehouse for every sort of available material and contraption. No planning meeting. No discussion of feasibility. No identification of who determined where the component parts could be acquired, or even what they would be. (Fievel in fact seems to have never been anywhere near the warehouse before to even know.) Suddenly, a character with the personality of a five-year old seems to have developed into a mechanical genius, for the mice amazingly build what amounts to a giant mouse robot, with balloons for body segments, jaws that seem to have been excised from a prehistoric skeleton in storage, and a wheeled trolley for its base, loaded with fireworks for ammunition, Christened the “secret weapon.” How could Fievel possibly have come up with such a concept? This “Hail Mary to the rescue” type formula would seem to recur in other Bluth productions, proving that Bluth could develop an initial scenario, but rarely knew how to effectively wrap it up. Had we known more of his earlier work at the time, we might have noted earlier instances of this pattern developing, such as in the sudden ending of the television special “Banjo the Woodpile Cat”, or even his early work on Disney’s “The Small One”, relying for a ready-made sudden ending upon the most obvious “Hail Mary” of all.) I was not impressed with the flashy facade of his fireworks finale, and was left with a feeling of “What? That was it?” Few others at the time seemed to see it that way. Given time, the public eventually caught on in his later films, leading to the gradual demise and final failure of the studio.

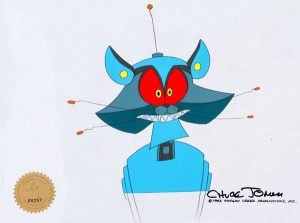

Stay Tuned (Warner, 8/14/92) is primarily a live-action parody of old movies and television, starring John Ritter and Pam Dawber. It is presented with a horror twist, as Ritter is sold a satellite dish system bringing in 666 channels of exclusive broadcasting, not realizing the salesman is an emissary of the devil, and that the dish is a device for sucking in souls. Captives of the system have to escape a gauntlet of changing channels, in a broadcast network known as “Hellivision”, each program fraught with death perils. If they survive 24 hours. They are freed – if not, they lose their soul to the devil. The highlight of the film is an animated segment directed by Chuck Jones, entitled “Robocat”, in which Ritter and Dawber are transformed into animated mice. The home’s owners have just acquired the latest in pest-control devices – a robotic cat, realistically structured and jointed but constructed of shining steel instead of fur, with glowing red eyes, and a seemingly limitless arsenal of destructive weapons. The aroma of a tray full of donuts attracts Ritter to the kitchen table. The cat appears, flinging open a doorway, and a megaphone emerges from its throat, announcing “Warning! Warning! You are trespassing in a human habitation. The penalty is death.” Ritter’s mouse face falls entirely at this pronouncement of doom. He slides down the donut pile and off the table onto the floor, using a donut tightened around his waist. He is momentarily pinned to the floor by its weight, as the cat produces a revolver out of its back, and begins shooting away. “My doctor was right”, says Ritter, “Donuts will be the death of me.” Popping loose from the donut just in time, he and Dawber climb to a kitchen counter and hide inside a toaster. The cat’s paw enters the frame, pushing the toaster’s handle down, to turn the device red hot. It pops Ritter and Dawber into the air, slightly charcoaled, while the cat waits below with open jaws. The mice fall into the cat’s mouth, but their heat soon turns the cat’s head as fiery-red as the toaster. The cat spits them out, into another room, then follows. He at first can spot no sign of the mice, but finds them hiding behind the painted images of the old farm couple in a wall-mounted duplication of the famous “American Gothic”. The cat levels a flame thrower at the painting and opens fire. Not only the mice react in shock-take, but the farm couple as well, as the flames shoot over their heads, burning the painted farmhouse down. The mice make a retreat to the bathroom, where the cat sees two mice-head silhouettes visible just over the edge of the bathtub. The heads are fakes, constructed of bath balls stuck together with toothpicks, and the cat fires a ray-gun blast at the bathtub, partially blowing away the edge of the tub. The cat curiously peers in for what is left of his victims, but Ritter and Dawber sneak up behind him, armed with an aerosol can and a lit match.

Stay Tuned (Warner, 8/14/92) is primarily a live-action parody of old movies and television, starring John Ritter and Pam Dawber. It is presented with a horror twist, as Ritter is sold a satellite dish system bringing in 666 channels of exclusive broadcasting, not realizing the salesman is an emissary of the devil, and that the dish is a device for sucking in souls. Captives of the system have to escape a gauntlet of changing channels, in a broadcast network known as “Hellivision”, each program fraught with death perils. If they survive 24 hours. They are freed – if not, they lose their soul to the devil. The highlight of the film is an animated segment directed by Chuck Jones, entitled “Robocat”, in which Ritter and Dawber are transformed into animated mice. The home’s owners have just acquired the latest in pest-control devices – a robotic cat, realistically structured and jointed but constructed of shining steel instead of fur, with glowing red eyes, and a seemingly limitless arsenal of destructive weapons. The aroma of a tray full of donuts attracts Ritter to the kitchen table. The cat appears, flinging open a doorway, and a megaphone emerges from its throat, announcing “Warning! Warning! You are trespassing in a human habitation. The penalty is death.” Ritter’s mouse face falls entirely at this pronouncement of doom. He slides down the donut pile and off the table onto the floor, using a donut tightened around his waist. He is momentarily pinned to the floor by its weight, as the cat produces a revolver out of its back, and begins shooting away. “My doctor was right”, says Ritter, “Donuts will be the death of me.” Popping loose from the donut just in time, he and Dawber climb to a kitchen counter and hide inside a toaster. The cat’s paw enters the frame, pushing the toaster’s handle down, to turn the device red hot. It pops Ritter and Dawber into the air, slightly charcoaled, while the cat waits below with open jaws. The mice fall into the cat’s mouth, but their heat soon turns the cat’s head as fiery-red as the toaster. The cat spits them out, into another room, then follows. He at first can spot no sign of the mice, but finds them hiding behind the painted images of the old farm couple in a wall-mounted duplication of the famous “American Gothic”. The cat levels a flame thrower at the painting and opens fire. Not only the mice react in shock-take, but the farm couple as well, as the flames shoot over their heads, burning the painted farmhouse down. The mice make a retreat to the bathroom, where the cat sees two mice-head silhouettes visible just over the edge of the bathtub. The heads are fakes, constructed of bath balls stuck together with toothpicks, and the cat fires a ray-gun blast at the bathtub, partially blowing away the edge of the tub. The cat curiously peers in for what is left of his victims, but Ritter and Dawber sneak up behind him, armed with an aerosol can and a lit match.

They light the spray into a flame thrower of their own, roasting the cat’s rear, and causing him to leap into what water is left in the tub. Then, Ritter and Dawber push from a counter a plugged-in hair dryer into the tub (Dawber pausing to caution the kids in the audience not to try this at home). The cat momentarily sizzles in the electrical short circuit, then half-falls out of the tub, its eyes popping out on springs, and parts askew everywhere. A readout on the robot’s back lights, reading “Activate 2nd Life”. With that, a magnet on a pivoting pole emerges from the robot’s back, pulling all the strewn loose parts together, until the cat is reassembled good as new. Ritter and Dawber have by now taken refuge in a doll house, where they are challenged at the front door to surrender by the robot, multiple weapons drawn against them. In an idea borrowed from Jones’ original Warner cartoon, “Mouse Warming”, the mice make an escape between the cat’s legs, driving in a mouse-sized toy car. Dawber spots a mousehole with TV static visible within – the portal for an exit to another channel. She yells for Ritter to turn, but Ritter steers erratically in his haste, tossing Dawber through the portal, nut missing the opening himself. The cat is quick to produce in one paw a steel plug in precisely mousehole shape, which he rivets into the wall with a small rivet gun to plug the opening. Ritter comments this is one clever pussy, but also observes that he’s seen enough cartoons that he should know how an animated character would deal with such a situation. Of course! Post an urgent order by mail to the Acme Company. A doorbell ring announces a special delivery which the cat answers, revealing – a robotic bulldog. Now it is the cat’s turn to have his face fall, as the entire house is seen from the outside, first whirling, then stopping with most of its shingles, windows and panels in a state of disarray, then exploding entirely. All that is left are a few sticks of furniture, and a few baseboards. Among them is the baseboard with the mousehole – with the riveted plug still appearing entirely intact. Ritter emerges alive from under one of the items of furniture, and tugs and strains at the metal plug to no avail, it appearing to be holding firm. He moans that now he’ll never get out of here – until the plug, for no apparent reason, drops loose like a drawbridge onto his back, opening the portal. Ritter happily pops up and back to normal, revving up for a quick exit, but nor before saying to the audience, “Th-th-th-That’s all, folks!”

They light the spray into a flame thrower of their own, roasting the cat’s rear, and causing him to leap into what water is left in the tub. Then, Ritter and Dawber push from a counter a plugged-in hair dryer into the tub (Dawber pausing to caution the kids in the audience not to try this at home). The cat momentarily sizzles in the electrical short circuit, then half-falls out of the tub, its eyes popping out on springs, and parts askew everywhere. A readout on the robot’s back lights, reading “Activate 2nd Life”. With that, a magnet on a pivoting pole emerges from the robot’s back, pulling all the strewn loose parts together, until the cat is reassembled good as new. Ritter and Dawber have by now taken refuge in a doll house, where they are challenged at the front door to surrender by the robot, multiple weapons drawn against them. In an idea borrowed from Jones’ original Warner cartoon, “Mouse Warming”, the mice make an escape between the cat’s legs, driving in a mouse-sized toy car. Dawber spots a mousehole with TV static visible within – the portal for an exit to another channel. She yells for Ritter to turn, but Ritter steers erratically in his haste, tossing Dawber through the portal, nut missing the opening himself. The cat is quick to produce in one paw a steel plug in precisely mousehole shape, which he rivets into the wall with a small rivet gun to plug the opening. Ritter comments this is one clever pussy, but also observes that he’s seen enough cartoons that he should know how an animated character would deal with such a situation. Of course! Post an urgent order by mail to the Acme Company. A doorbell ring announces a special delivery which the cat answers, revealing – a robotic bulldog. Now it is the cat’s turn to have his face fall, as the entire house is seen from the outside, first whirling, then stopping with most of its shingles, windows and panels in a state of disarray, then exploding entirely. All that is left are a few sticks of furniture, and a few baseboards. Among them is the baseboard with the mousehole – with the riveted plug still appearing entirely intact. Ritter emerges alive from under one of the items of furniture, and tugs and strains at the metal plug to no avail, it appearing to be holding firm. He moans that now he’ll never get out of here – until the plug, for no apparent reason, drops loose like a drawbridge onto his back, opening the portal. Ritter happily pops up and back to normal, revving up for a quick exit, but nor before saying to the audience, “Th-th-th-That’s all, folks!”

Santa vs. the Snowman (O Entertainment, 12/12/97 (TV), 11/1/02 (IMAX)) began life as a television special, then grew to an IMAX event in 3-D. This CGI oddity centers on a mute snowman, lonely and cold at the North Pole, who stumbles upon Santa’s cottage and workshop, but is rebuffed when he attempts to make off with an irresistable toy flute. The Snowman escapes an elf security force, but ponders why Santa should get all the love, with none left over for him. He develops “Project Blizzard” – a battle plan for takeover of the holiday by force, with himself to be the new Santa. An army is hatched through use of a book entitled, “Minions Made Easy”, dropping ice cubes into snowbanks, which hatch into eager young duplicates of himself. Robotic technology is employed, as the snowman personally leads a squad of vehicles cleverly resembling the Star Wars “walkers” from the planet Hoth, their command centers and turrets built of icy igloos with cannon noses. They all show up at the perimeter of Santa’s compound, with the ultimatum message “Give me Christmas”. Santa and his elves are likewise militarily equipped for such an emergency, and Santa (delightfully underplayed in an excellent read by Jonathan Winters) responds to the message that all the snowman will get is coal and switches, and an entry on the naughty list. Santa orders the elves to “scramble the reindeer”, who take off with jet propulsion from their hooves in vertical ascent like Harrier jets. The reindeer bravely zig and zag around and between the walkers, while an elf depolys a special bazooka which fires an ice pick into one of the igloos, then taps itself in with a built-in hammer, splitting the igloo into shards. Clever sight gags abound, as the elves release freshly-baed gingerbread men, whose embrace melts the snow minions – until they discover their foes can be eaten. Casualties arise, with hypothermia and bad cases of sniffles, and Santa decides to settle things by calling out his own robotic assault vehicle – a giant nutcracker soldier, propelled by tank treads. “Santa’s comin’ to town”, the jolly old elf proclaims. The snowan counters with a Yeti, but Santa says “Let’s heat things up a little”, turning on heat jets from the nutcracker’s chest. The Yeti is reduced to a size barely taller than an elf’s toes, and runs off whimpering like a wounded dog. The snowman’s last remaining command walker is surrounded by the elves, and the snowman emerges in apparent surrender. However, as Santa emerges from the nutcracker to discuss terms, the snowman whistles. It’s an ambush, as the snowman has another thousand minions in reserve to surround Santa and the elves. All Santa can do is respond with the unexpected expletive, “Oy!”

Santa vs. the Snowman (O Entertainment, 12/12/97 (TV), 11/1/02 (IMAX)) began life as a television special, then grew to an IMAX event in 3-D. This CGI oddity centers on a mute snowman, lonely and cold at the North Pole, who stumbles upon Santa’s cottage and workshop, but is rebuffed when he attempts to make off with an irresistable toy flute. The Snowman escapes an elf security force, but ponders why Santa should get all the love, with none left over for him. He develops “Project Blizzard” – a battle plan for takeover of the holiday by force, with himself to be the new Santa. An army is hatched through use of a book entitled, “Minions Made Easy”, dropping ice cubes into snowbanks, which hatch into eager young duplicates of himself. Robotic technology is employed, as the snowman personally leads a squad of vehicles cleverly resembling the Star Wars “walkers” from the planet Hoth, their command centers and turrets built of icy igloos with cannon noses. They all show up at the perimeter of Santa’s compound, with the ultimatum message “Give me Christmas”. Santa and his elves are likewise militarily equipped for such an emergency, and Santa (delightfully underplayed in an excellent read by Jonathan Winters) responds to the message that all the snowman will get is coal and switches, and an entry on the naughty list. Santa orders the elves to “scramble the reindeer”, who take off with jet propulsion from their hooves in vertical ascent like Harrier jets. The reindeer bravely zig and zag around and between the walkers, while an elf depolys a special bazooka which fires an ice pick into one of the igloos, then taps itself in with a built-in hammer, splitting the igloo into shards. Clever sight gags abound, as the elves release freshly-baed gingerbread men, whose embrace melts the snow minions – until they discover their foes can be eaten. Casualties arise, with hypothermia and bad cases of sniffles, and Santa decides to settle things by calling out his own robotic assault vehicle – a giant nutcracker soldier, propelled by tank treads. “Santa’s comin’ to town”, the jolly old elf proclaims. The snowan counters with a Yeti, but Santa says “Let’s heat things up a little”, turning on heat jets from the nutcracker’s chest. The Yeti is reduced to a size barely taller than an elf’s toes, and runs off whimpering like a wounded dog. The snowman’s last remaining command walker is surrounded by the elves, and the snowman emerges in apparent surrender. However, as Santa emerges from the nutcracker to discuss terms, the snowman whistles. It’s an ambush, as the snowman has another thousand minions in reserve to surround Santa and the elves. All Santa can do is respond with the unexpected expletive, “Oy!”

Santa and the elves are imprisoned in an ice jail, as Santa remarks to himself “The Easter Bunny will never let me hear the end of this.” The snowman takes off in a sleigh pulled by eight of his minions, wearing a Santa hat, to become loved by children everywhere. But his brand of toys don’t make the grade, crumbling and melting because they are made of ice. Worse yet, gis team of minions melts on top of the first roof from the heat of the fireplace in the house below. Santa has meanwhile been rescued by a remaining undercover elf armed with a heat lamp, and shows up to save the situation with one of his own toys for the child. The snowman realizes there can be only one Santa, and surrenders. Santa is surprisingly forgiving, and not only offers the snowman a lift home, but presents him with the flute, which had been intended as his Christmas present in the first place, cautioning him next time to wait until Christmas. The two become friends, and all ends in holiday happiness.

The Iron Giant (Warner, 7/31/99, Brad Bird, dir.) was released during a time when, if a picture didn’t say Disney or Pixar, it didn’t make money (it returned only 31 million of its 50 million budget). Yet Warner poured its heart and soul into it, and over the years, it has become a cult favorite. Set in the cold-war era of the 1950’s, it does a marvelous job of encapsulating a simpler yet complicated time when threat of foreign invasion and nuclear weapons abounded in the imaginations and consciousness of the public mind, and when national campaigns like “Duck and Cover” (directly lampooned in the film) were thought to be a means of keeping the populace from living in ever-present panic. Amidst this atmosphere, a young boy (Hogarth) investigates rumors of a strange object falling from space, coupled with the disappearance of his TV antenna in mid broadcast. (Metal munching moon mice?) In a wooded area, at an unmanned electrical substation, he encounters a 100-foot tall metal robot with glowing eye-cells, a dome-shaped head, and a broad-chested humanoid-style skeletal frame. It passes right over him, headed for the substation, and begins devouring its metal power poles. When it reaches for the generator coils as dessert, it receives a tremendous electrical shock, and roars in pain, becoming incapacitated and tangled in power wires. Hogarth runs for his life, but when he realizes the robot’s plight, races back, and pulls a switch to turn the generator off. The robot briefly appears unconscious, but its eyes glow to life again. Hogarth flees, but encounters more lights – the headlights of his mother’s car, out looking for him. Mom won’t believe his wild story, thinking its his overactive imagination and love of science fiction comics and scary movies.

The Iron Giant (Warner, 7/31/99, Brad Bird, dir.) was released during a time when, if a picture didn’t say Disney or Pixar, it didn’t make money (it returned only 31 million of its 50 million budget). Yet Warner poured its heart and soul into it, and over the years, it has become a cult favorite. Set in the cold-war era of the 1950’s, it does a marvelous job of encapsulating a simpler yet complicated time when threat of foreign invasion and nuclear weapons abounded in the imaginations and consciousness of the public mind, and when national campaigns like “Duck and Cover” (directly lampooned in the film) were thought to be a means of keeping the populace from living in ever-present panic. Amidst this atmosphere, a young boy (Hogarth) investigates rumors of a strange object falling from space, coupled with the disappearance of his TV antenna in mid broadcast. (Metal munching moon mice?) In a wooded area, at an unmanned electrical substation, he encounters a 100-foot tall metal robot with glowing eye-cells, a dome-shaped head, and a broad-chested humanoid-style skeletal frame. It passes right over him, headed for the substation, and begins devouring its metal power poles. When it reaches for the generator coils as dessert, it receives a tremendous electrical shock, and roars in pain, becoming incapacitated and tangled in power wires. Hogarth runs for his life, but when he realizes the robot’s plight, races back, and pulls a switch to turn the generator off. The robot briefly appears unconscious, but its eyes glow to life again. Hogarth flees, but encounters more lights – the headlights of his mother’s car, out looking for him. Mom won’t believe his wild story, thinking its his overactive imagination and love of science fiction comics and scary movies.

But other reports are being received by Washington – of a boat colliding with the fallen object in the sea, a tractor with a bite out of it, and now the wrecked power generator. A special agent from an undisclosed agency is sent out, who at first scoffs at the reports as the kind of bunk he’s always sent out to investigate – until he returns to his car, to find a large bite taken out of one side. Then, the whole car disappears. The only artifact of any other witnesses to the events is a b-b gun located at the power generator site, with Hogarth’s name etched on the stock. The agent takes note of this. The next day, Hogarth returns to the woods, armed with a camera, and a large sheet of metal to use as bait for the robot. He waits and waits, falling asleep. When he awakens, the robot is standing directly behind him. Panicking, Hogarth forgets the camera and runs again. The robot follows. Hogarth runs into a tree branch in his way, knocking himself down into a semi-seated position. The robot catches up, but does not attack. Instead, it lowers itself with a plop into a seated position similar to Hogarth’s. When Hogarth moves, the robot matches him. Hogarth realizes the robot doesn’t want to hurt him, but is imitating him. The robot drops in front of him the on-off switch from the generator, and Hogarth realizes the robot is aware he saved its “life”. He attempts to communicate with the iron man, who he notices has a dent on the side of its domed head. The robot is unresponsive about his falling from the sky, not seeming to remember anything, as if an amnesia victim from the bump. So his point of origin remains a mystery. However, Hogarth is able to teach the robot a few words identifying objects, and realizes the robot can learn and be trained. Hogarth believes he’s the luckiest kid in America to have a robot of his own – a discovery bigger than…even television! But what to do with him? He can’t get the robot to understand not to follow him home, though he repeats “I go. You stay. No following.” The curious robot crosses over some train tracks, and thinks they’ll make a good snack, uprooting a section of the rails. A signal indicates a train is approaching, and Hogarth begs the robot to put back the rails.

But other reports are being received by Washington – of a boat colliding with the fallen object in the sea, a tractor with a bite out of it, and now the wrecked power generator. A special agent from an undisclosed agency is sent out, who at first scoffs at the reports as the kind of bunk he’s always sent out to investigate – until he returns to his car, to find a large bite taken out of one side. Then, the whole car disappears. The only artifact of any other witnesses to the events is a b-b gun located at the power generator site, with Hogarth’s name etched on the stock. The agent takes note of this. The next day, Hogarth returns to the woods, armed with a camera, and a large sheet of metal to use as bait for the robot. He waits and waits, falling asleep. When he awakens, the robot is standing directly behind him. Panicking, Hogarth forgets the camera and runs again. The robot follows. Hogarth runs into a tree branch in his way, knocking himself down into a semi-seated position. The robot catches up, but does not attack. Instead, it lowers itself with a plop into a seated position similar to Hogarth’s. When Hogarth moves, the robot matches him. Hogarth realizes the robot doesn’t want to hurt him, but is imitating him. The robot drops in front of him the on-off switch from the generator, and Hogarth realizes the robot is aware he saved its “life”. He attempts to communicate with the iron man, who he notices has a dent on the side of its domed head. The robot is unresponsive about his falling from the sky, not seeming to remember anything, as if an amnesia victim from the bump. So his point of origin remains a mystery. However, Hogarth is able to teach the robot a few words identifying objects, and realizes the robot can learn and be trained. Hogarth believes he’s the luckiest kid in America to have a robot of his own – a discovery bigger than…even television! But what to do with him? He can’t get the robot to understand not to follow him home, though he repeats “I go. You stay. No following.” The curious robot crosses over some train tracks, and thinks they’ll make a good snack, uprooting a section of the rails. A signal indicates a train is approaching, and Hogarth begs the robot to put back the rails.

The robot obliges, but is too much of a perfectionist to let well enough alone, and is still on the tracks straightening the alignment when the train hits. The impact does more damage to the robot than the train, scattering several of his major components as well as his main frame into the forest mist. But a beeping signal from an antenna on the robot’s head causes his components to slowly creep their way back to him, and reassemble themselves. Hogarth eventually gets the robot tucked into an old barn for the night, though a comic incident develops at the dinner table when the robot’s last loose component (one hand) creeps its way into the kitchen in search of its owner, and has to be re-routed out the window before being detected. And who should show up in the confusion but the government agent, looking for a phone to report in on the train accident. Hogarth’s actions seem suspicious – and the agent’s interest further peaks when he learns the boy’s name. The agent rents a room in the family house, bent on watching the boy’s every move until he cracks about the mystery metal-eater. Hogarth manages to ditch the agent the next day by buying him an ice cream soda, which he liberally tops with a broken-up chocolate bar (actually, a chocolate laxative). Wondering where he will supply metal for the robot’s appetite, he turns to a local junkyard, run by an acquaintance who is developing a crush on Hogarth’s widowed mother. They are discovered, but after the owner’s initial protests, Hogarth manages to explain enough to find the robot a temporary home. He reads the robot bedtime stories from comic books, including stories of Superman. The robot thinks he looks more like an evil robot Atomo in another comic, but Hogarth emphasizes that you can be whatever you want to be, and that he and Superman both have things in common, falling from the sky and at first confused. He further emphasizes Superman’s creed, to always use his powers for good, not evil. Another touching moment comes

The robot obliges, but is too much of a perfectionist to let well enough alone, and is still on the tracks straightening the alignment when the train hits. The impact does more damage to the robot than the train, scattering several of his major components as well as his main frame into the forest mist. But a beeping signal from an antenna on the robot’s head causes his components to slowly creep their way back to him, and reassemble themselves. Hogarth eventually gets the robot tucked into an old barn for the night, though a comic incident develops at the dinner table when the robot’s last loose component (one hand) creeps its way into the kitchen in search of its owner, and has to be re-routed out the window before being detected. And who should show up in the confusion but the government agent, looking for a phone to report in on the train accident. Hogarth’s actions seem suspicious – and the agent’s interest further peaks when he learns the boy’s name. The agent rents a room in the family house, bent on watching the boy’s every move until he cracks about the mystery metal-eater. Hogarth manages to ditch the agent the next day by buying him an ice cream soda, which he liberally tops with a broken-up chocolate bar (actually, a chocolate laxative). Wondering where he will supply metal for the robot’s appetite, he turns to a local junkyard, run by an acquaintance who is developing a crush on Hogarth’s widowed mother. They are discovered, but after the owner’s initial protests, Hogarth manages to explain enough to find the robot a temporary home. He reads the robot bedtime stories from comic books, including stories of Superman. The robot thinks he looks more like an evil robot Atomo in another comic, but Hogarth emphasizes that you can be whatever you want to be, and that he and Superman both have things in common, falling from the sky and at first confused. He further emphasizes Superman’s creed, to always use his powers for good, not evil. Another touching moment comes

To Be Continued: A final wrap-up of later features, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

“How could Fievel possibly have come up with such a concept?” Well, because earlier in the picture Fievel heard Papa tell stories about the Giant Mouse of Minsk, who protected them from cats in the old country. (This is analogous to the Golem of Prague, a figure in Jewish folklore made out of living clay or mud who likewise defended the Jewish people against pogroms.) So when the mice need protection against the cats, it’s natural that Fievel would think of the Giant Mouse. It wouldn’t require any advanced technical training. The device itself isn’t terribly sophisticated, only big and scary — less of a robot and more of a parade float. Amateurs build those all the time. I don’t especially wish to defend Don Bluth’s storytelling ability, because I think your criticism of that is right on the mark. But I think the denouement works in “An American Tail”.

I never saw “Stay Tuned”, because I’ve had a policy of avoiding movies that star sitcom actors ever since I suffered through “Rabbit Test”, “First Family”, and a host of similar bombs in the late ’70s and early ’80s. Unfortunately this meant that I missed out on most of the early work of Robin Williams and Tom Hanks, and I also missed out on Chuck Jones’s wonderful animated segment in this film. I love it that the postage stamp on Roy’s letter to the Acme company is adorned with a likeness of Jones!

I well remember seeing “The Iron Giant” with my friends in 1999. We thought any Warner Bros. cartoon about a giant robot could only be an Animaniacs-style parody of Ultraman or Gigantor, and so we all settled in to laugh at something silly and ridiculous. Boy, were we surprised. None of us expected anything so smart, sophisticated, and emotional — and funny, too, like the episodes of M*A*S*H* featuring the cold warrior Col. Flagg. One of my friends said afterwards that “I totally forgot I was watching a cartoon,” and he meant it as high praise. A lot of people deserve praise for “The Iron Giant”, director Brad Bird above all, but I especially want to single out sitcom actress Jennifer Aniston for her performance as Hogarth’s mother, a more mature and nuanced role than she had ever tackled before. Aniston had a few other roles in animation around this time — I remember she was in Disney’s Hercules TV series — but that was it. Too bad. She might be making $6000 a day as a cartoon voice actress today if she had kept at it.

I hope you’ll backtrack a bit to “Robot Carnival” next week before we finally say “Bye, robots!”

I’ve seen literally none of these. Stay Tuned sounds funny.

Controversy? “Iron Giant” was too hyperactively animated for me to forget I was watching a cartoon, not just the scene where the kid gets his first taste of coffee.

I was lucky enough to have read in a magazine about the Chuck Jones segment of “Stay Tuned” before it came out.

Another anthology film. “Heavy Metal,” probably doesn’t need a full rundown: there’s a Robbie the Robot cameo on the streets of future NYC, Captain Sternn accompanied by an eyeball with (gloved!) hands that is more obviously steam-powered in the comic, and a segment showing aliens had a not-incredibly lifelike android debunking UFO reports and a more robotic one looking for “close encounters.”

The Iron Giant was such a surprise. Great to see it covered so thoughtfully here. Just a gem.

I would recommend EVERYONE who loves genre movies to get Stay Tuned on Bluray. I originally got it just to have a DVD copy of the animated segment (the highest quality at the time), but was pleasantly surprised to find the rest of the film as good. Yes, sure, it’s not ANIMATED, but the different “worlds” the characters travel to are very impressive sets (for a mid-budget feature) and the writing does a good job at being entertaining. As I said, Stay Tuned is a genre movie. Meaning, once you know the premise, you know what you’re getting. Married couple gets trapped in TV World and must escape in 24 hours or stay trapped forever. That’s the plot, and you either like the idea or not.