By late 1935 and 1936, color was beginning to rule when it came to cartoons emphasizing spectacle and special effects. Little wonder then that all but one of the offerings for this week’s survey of weather-related cartoons appear in color. Budgets were beginning to get quite high, as the major studios competed vigorously to see who could present the splashiest and most detailed renderings of stormy situations. Disney continued to be in the forefront – in fact, as usual, gleaning the Oscar for one subject production we’ll visit below. However, during this period, others really gave them a run for their money, producing some of the most expensive and lavish episodes of their film career to compete on the same turf level as the Mickey Mouse masters.

Principal in this competition was MGM, currently issuing the products of Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising. The MGM executives were no longer content with the biggest studio in Hollywood churning out distribution of the work of Iwerks, who seemed not able to progress his productions beyond a level that now seemed far removed from the class and visual sophistication of a Disney production. (Iwerks would in fact show considerable later improvement in his work-for-hire projects for Columbia, but likely did not generate the confidence level with the MGM execs to obtain the needed increase in budgets for better artwork and 3-strip color that he ultimately found at Columbia.) So, for a time, they let Harman and Ising virtually get away with murder – permitting the spending of exorbitant amounts to retrain their artists, perfect special effects, retool to all color production, and come up with elaborate and detailed settings for fantasies and adventures, often up to or exceeding 10 minutes in length. While some character designs retained traces of the quirks of the artists’ earlier styles, other films became quite stunning in their beauty and detail – and literally looked like they could have been produced at Disney. MGM would quickly pass the quality levels of Disney’s former-closest competitor, Max Fleischer, leaving most of Fleischer’s productions far behind in the dust. By 1940, MGM would make such a mark on quality as to finally break the years of Disney’s exclusivity in receipt of the Oscar for best animated short subject. Meanwhile, on a much more restricted budget, an ex-Disney veteran, Burt Gillett, was also trying his best to match his former employer’s style, likewise moving into all-color production at Van Buren, with a staff of retrained artists tutored in the Disney manner (though perhaps more closely resembling Disney’s visuals from a few seasons back, rather than his most current productions), and development of special effects permitting spectacle on the screen as backdrop for somewhat more simple character animation, in Gillett’s “Rainbow Parade” series. It was, in short, a good vintage period for animation in general, with a rich array of quality animation available to the local Bijou to keep the public satisfied – and maybe a tad spoiled from exceedingly high expectations for their entertainment.

Principal in this competition was MGM, currently issuing the products of Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising. The MGM executives were no longer content with the biggest studio in Hollywood churning out distribution of the work of Iwerks, who seemed not able to progress his productions beyond a level that now seemed far removed from the class and visual sophistication of a Disney production. (Iwerks would in fact show considerable later improvement in his work-for-hire projects for Columbia, but likely did not generate the confidence level with the MGM execs to obtain the needed increase in budgets for better artwork and 3-strip color that he ultimately found at Columbia.) So, for a time, they let Harman and Ising virtually get away with murder – permitting the spending of exorbitant amounts to retrain their artists, perfect special effects, retool to all color production, and come up with elaborate and detailed settings for fantasies and adventures, often up to or exceeding 10 minutes in length. While some character designs retained traces of the quirks of the artists’ earlier styles, other films became quite stunning in their beauty and detail – and literally looked like they could have been produced at Disney. MGM would quickly pass the quality levels of Disney’s former-closest competitor, Max Fleischer, leaving most of Fleischer’s productions far behind in the dust. By 1940, MGM would make such a mark on quality as to finally break the years of Disney’s exclusivity in receipt of the Oscar for best animated short subject. Meanwhile, on a much more restricted budget, an ex-Disney veteran, Burt Gillett, was also trying his best to match his former employer’s style, likewise moving into all-color production at Van Buren, with a staff of retrained artists tutored in the Disney manner (though perhaps more closely resembling Disney’s visuals from a few seasons back, rather than his most current productions), and development of special effects permitting spectacle on the screen as backdrop for somewhat more simple character animation, in Gillett’s “Rainbow Parade” series. It was, in short, a good vintage period for animation in general, with a rich array of quality animation available to the local Bijou to keep the public satisfied – and maybe a tad spoiled from exceedingly high expectations for their entertainment.

Summertime (Ub Iwerks, Comicolor, 6/15/35) – An unusual throwback to Iwerks’ Silly Symphony days, much in the vein of the “seasons” quartet of titles begun by Iwerks for Disney, and set to classical music. It is odd that it was not titled to refer to Spring, as it really deals with the transition from Winter, skipping an entire season in its title. Another odd aspect is that, even though Iwerks continued to have his original musical director Carl Stalling on staff, who even receives screen credit for the score, Carl’s only real role appears to be in selection of items from the classics for the score, and playing of a few meager piano notes as segue. While small orchestras had been satisfactory for Iwerks in the Disney days, someone either wanted this film to sound like a full concert for a change, or Iwerks was simply cutting budgetary corners in not holding a musical session – so no music is performed by the studio orchestra, but is instead supplied from needle-drops with audible surface noise, likely from the vaults of Victor records. Any guidance from our readers as to the actual orchestras and recording dates of items in the score will be greatly appreciated.

Summertime (Ub Iwerks, Comicolor, 6/15/35) – An unusual throwback to Iwerks’ Silly Symphony days, much in the vein of the “seasons” quartet of titles begun by Iwerks for Disney, and set to classical music. It is odd that it was not titled to refer to Spring, as it really deals with the transition from Winter, skipping an entire season in its title. Another odd aspect is that, even though Iwerks continued to have his original musical director Carl Stalling on staff, who even receives screen credit for the score, Carl’s only real role appears to be in selection of items from the classics for the score, and playing of a few meager piano notes as segue. While small orchestras had been satisfactory for Iwerks in the Disney days, someone either wanted this film to sound like a full concert for a change, or Iwerks was simply cutting budgetary corners in not holding a musical session – so no music is performed by the studio orchestra, but is instead supplied from needle-drops with audible surface noise, likely from the vaults of Victor records. Any guidance from our readers as to the actual orchestras and recording dates of items in the score will be greatly appreciated.

Old Man Winter makes a reappearance, still apparently roaming the woods after the mischief he caused in “Jack Frost”. But he has overstayed his welcome. The sun, himself forced to wear a coating of icicles upon his head like a hat, is fed up with merely peeking through dense clouds, and strains with all his might to get his internal burners going, turning deep red to generate a heat ray toward the ground. He catches Old Man Winter on the seat of his pants with the beam, and increases the intensity, frightening the freezing fiend off over a hill. Sunny then concentrates his efforts upon melting the snow, including a fully-built snowman that dissolves away, to reveal underneath the slumbering figure of the spirit Pan, who awakens upon a rock concealed below him. Pan raises his flute, and begins playing the melodies of Spring, awakening flowers from the ground to perform a typical dance as in the Disney days, and also awakening other animals, such as turtles who play tic-tac-toe on the chest segments of one of the larger turtles on the clan. One scene that is definitely non-Disney, which surprisingly got by the censors, continues the studio’s liking for innuendo and “blue” humor, by “artistically” transforming the silhouettes of three trees into a trio of dancing barenaked ladies, either from reference footage or rotoscope. A team of husky male centaurs also stages a polo game, their horse-halves serving as their own steeds to conduct the sport. (One of the centaurs is a caricature of Will Rogers, who was an avid fan of the game, and whose personal polo field still stands today at Will Rogers State Park, and would serve as the model for the stadium in the following year’s Mickey’s Polo Team for Disney).

A letter is delivered by a rabbit postman to Mr. Groundhog that Spring is here. The groundhog dances merrily outside in celebration, but a surprise is waiting for him. Old Man Winter has not in fact disappeared, but is hiding behind a rock. Working a little magic, he extends and transforms his own shadow, until it stretches to connect with the feet of the groundhog. He further transforms its shape, allowing it to grow into the form of a fierce rodent that looks more rat than groundhog. The groundhog is of course frightened out of his wits, and retreats headlong into his home. With that taken care of, Winter is quick to cover the territory with a full coating of snow again. Blowing up a stiff breeze to drive the snow, Winter blows away a tree, revealing to the elements a totem pole of animals hidden inside. Birds in other trees are forced into immediate migration again, their new nests of eggs also sprouting wings through their shells to follow their parents. Pan isn’t going to take this lying down, and converts the notes of his flute into a trumpet call to arms. The centaurs serve as his army. With animals astride their backs to feed them ammunition in the form of snowballs, they gallop along, using their polo mallets to sock snowballs at Winter. Winter shows little regard for this attempt to use his own element against him, and casts a blizzard against the centaur troops, which gradually slows them with frost, then stops them in place, frozen in their tracks. Pan retreats to an old hollow tree, but spots another force of nature which can be put to use. The tree is inhabited by a nest of fireflies (designed as if carrying small red lightbulbs in their tails). Pan whispers to one of them his plan, and the bug nods in agreement. At a signal, the flies soar out of the tree and into the sky in a swarm. At a further command, each fly increases the voltage in their respective bulbs until they burst, the glass shattering and replaced by a small open flame. Now, they dive-bomb Old Man Winter, strafing over his back and between his legs. Winter moans in agony at the intense doses of heat, ad within a few passes is melted entirely away into a puddle, from which sprouts on the spot a funeral lily. The film ends with Pan playing music in celebration, as the centaurs dance around him in a circle for the iris out.

A letter is delivered by a rabbit postman to Mr. Groundhog that Spring is here. The groundhog dances merrily outside in celebration, but a surprise is waiting for him. Old Man Winter has not in fact disappeared, but is hiding behind a rock. Working a little magic, he extends and transforms his own shadow, until it stretches to connect with the feet of the groundhog. He further transforms its shape, allowing it to grow into the form of a fierce rodent that looks more rat than groundhog. The groundhog is of course frightened out of his wits, and retreats headlong into his home. With that taken care of, Winter is quick to cover the territory with a full coating of snow again. Blowing up a stiff breeze to drive the snow, Winter blows away a tree, revealing to the elements a totem pole of animals hidden inside. Birds in other trees are forced into immediate migration again, their new nests of eggs also sprouting wings through their shells to follow their parents. Pan isn’t going to take this lying down, and converts the notes of his flute into a trumpet call to arms. The centaurs serve as his army. With animals astride their backs to feed them ammunition in the form of snowballs, they gallop along, using their polo mallets to sock snowballs at Winter. Winter shows little regard for this attempt to use his own element against him, and casts a blizzard against the centaur troops, which gradually slows them with frost, then stops them in place, frozen in their tracks. Pan retreats to an old hollow tree, but spots another force of nature which can be put to use. The tree is inhabited by a nest of fireflies (designed as if carrying small red lightbulbs in their tails). Pan whispers to one of them his plan, and the bug nods in agreement. At a signal, the flies soar out of the tree and into the sky in a swarm. At a further command, each fly increases the voltage in their respective bulbs until they burst, the glass shattering and replaced by a small open flame. Now, they dive-bomb Old Man Winter, strafing over his back and between his legs. Winter moans in agony at the intense doses of heat, ad within a few passes is melted entirely away into a puddle, from which sprouts on the spot a funeral lily. The film ends with Pan playing music in celebration, as the centaurs dance around him in a circle for the iris out.

Three Orphan Kittens (Disney/United Artists, Silly Symphony, 10/26/35 – David Hand, dir.) – A Disney Oscar winner, especially effective for any audience member who knows anything about the ways and reactions of cats. This adorable cartoon captures the moves and nuances of cat behavior nearly to a T, which, along with its additional realism in depicting elaborate panning three-dimensional backgrounds, no doubt ensured its academy victory. On a cold and snowy evening, a mysterious sedan pulls up to a fence behind a home’s backyard, and tosses over the fence an unwanted sack – containing three adorable kittens, who are left abandoned. They huddle together to keep warm, but the drifting snow nearly covers the one of them most upwind. They look around for some refuge, until one of them spits a cellar window left unlatched, its hinges swaying in the cold breeze. There is just enough room between the lower frame of the window and the snow level for the kittens to slip inside. A detailed rendering of a warm central furnace in the cellar provides hope of comfort, and the cats slip upstairs, taking a peek through a doorway with door slightly ajar. The house is being attended to by a black domestic (the probable origin of Mammy Two Shoes, seen only from the waist down and with striped stockings), who is just setting the finishing touch on a dinner table – a freshly baked pie. When she leaves the room, the kittens investigate the table. They experience encounters with a fly on the pie, a nearly-empty milk bottle (which they keep getting stuck in in one way or another), and a pepper shaker than induces them to sneeze. They move to a little girl’s playroom for some misadventures with a mama doll and a feather pillow, then follow a stray feather into the living room, and up upon the keys of a player piano. The highlight of the film occurs when one of the kittens activates a music roll of “Kitten on the Keys”, resulting in a bumpy ride for all three of them on and around the keyboard. Escaping the device when the roll runs out, the kittens upset several objects with a crash, finally drawing Mammy’s attention. She catches them, and opens the front door, intent upon throwing them back outside into the snow. But a little girl appears from the playroom, and is thrilled at the sight of the kittens, asking if she can keep them. Mammy apparently has no authority to say no to the child, and surrenders the kittens, with a moan of “Land sakes.” The three “living dolls” become just that – the new “babies” for the girl to attend to in her doll carriage. The kittens can do without the baby bonnets, but cannot deny that the bottles of milk are worth the trouble.

Three Orphan Kittens (Disney/United Artists, Silly Symphony, 10/26/35 – David Hand, dir.) – A Disney Oscar winner, especially effective for any audience member who knows anything about the ways and reactions of cats. This adorable cartoon captures the moves and nuances of cat behavior nearly to a T, which, along with its additional realism in depicting elaborate panning three-dimensional backgrounds, no doubt ensured its academy victory. On a cold and snowy evening, a mysterious sedan pulls up to a fence behind a home’s backyard, and tosses over the fence an unwanted sack – containing three adorable kittens, who are left abandoned. They huddle together to keep warm, but the drifting snow nearly covers the one of them most upwind. They look around for some refuge, until one of them spits a cellar window left unlatched, its hinges swaying in the cold breeze. There is just enough room between the lower frame of the window and the snow level for the kittens to slip inside. A detailed rendering of a warm central furnace in the cellar provides hope of comfort, and the cats slip upstairs, taking a peek through a doorway with door slightly ajar. The house is being attended to by a black domestic (the probable origin of Mammy Two Shoes, seen only from the waist down and with striped stockings), who is just setting the finishing touch on a dinner table – a freshly baked pie. When she leaves the room, the kittens investigate the table. They experience encounters with a fly on the pie, a nearly-empty milk bottle (which they keep getting stuck in in one way or another), and a pepper shaker than induces them to sneeze. They move to a little girl’s playroom for some misadventures with a mama doll and a feather pillow, then follow a stray feather into the living room, and up upon the keys of a player piano. The highlight of the film occurs when one of the kittens activates a music roll of “Kitten on the Keys”, resulting in a bumpy ride for all three of them on and around the keyboard. Escaping the device when the roll runs out, the kittens upset several objects with a crash, finally drawing Mammy’s attention. She catches them, and opens the front door, intent upon throwing them back outside into the snow. But a little girl appears from the playroom, and is thrilled at the sight of the kittens, asking if she can keep them. Mammy apparently has no authority to say no to the child, and surrenders the kittens, with a moan of “Land sakes.” The three “living dolls” become just that – the new “babies” for the girl to attend to in her doll carriage. The kittens can do without the baby bonnets, but cannot deny that the bottles of milk are worth the trouble.

Bottles (Harman-Ising/MGM, Happy Harmonies, 1/11/36 – Hugh Harman, dir.) – Thunder and lightning provide appropriate atmospherics for this odd tale, in one of the longest MGM one-reelers ever produced. It is at the same time both an innovative horror film, and yet a throwback to Harman and Ising’s Warner days of midnight visits to shops where all the articles on sale come to life. An old-time apothecary is closed for the night, the building only lit by flickering gaslights on the street outside, and the periodic flashes of a prevailing thunderstorm. Rain beats down upon the windows as seen from inside the darkened sales area of the shop, as the camera travels to a small source of light in the back room. The proprietor of the shop, an elderly, white whiskered, roly-poly man, is laboring over mixing his last vat of chemical concoctions for the day – a fluid which he pours into a dark bottle bearing a painted design of crossed bones. He then caps the bottle with a combination eye-dropper and stopper, the cap of which is shaped like a skeleton head, to complete the universal emblem of a skull and crossbones – indicating poison. His work completed, the weary old man nods, and falls fast asleep, his head resting face down upon the desk. On cue as he falls asleep (also cuing us that we are about to enter a dream sequence), the poison bottle comes to life, cackling a sinister laugh, and boasting “Death walks tonight!”.

Bottles (Harman-Ising/MGM, Happy Harmonies, 1/11/36 – Hugh Harman, dir.) – Thunder and lightning provide appropriate atmospherics for this odd tale, in one of the longest MGM one-reelers ever produced. It is at the same time both an innovative horror film, and yet a throwback to Harman and Ising’s Warner days of midnight visits to shops where all the articles on sale come to life. An old-time apothecary is closed for the night, the building only lit by flickering gaslights on the street outside, and the periodic flashes of a prevailing thunderstorm. Rain beats down upon the windows as seen from inside the darkened sales area of the shop, as the camera travels to a small source of light in the back room. The proprietor of the shop, an elderly, white whiskered, roly-poly man, is laboring over mixing his last vat of chemical concoctions for the day – a fluid which he pours into a dark bottle bearing a painted design of crossed bones. He then caps the bottle with a combination eye-dropper and stopper, the cap of which is shaped like a skeleton head, to complete the universal emblem of a skull and crossbones – indicating poison. His work completed, the weary old man nods, and falls fast asleep, his head resting face down upon the desk. On cue as he falls asleep (also cuing us that we are about to enter a dream sequence), the poison bottle comes to life, cackling a sinister laugh, and boasting “Death walks tonight!”.

Developing arms and legs, the bottle pulls out its own stopper-eyedropper, and holds the top of the eyedropper over the head of the old man. With a squeeze, a few drops of the bottle’s contents are deposited upon the old man’s neck. No, he does not die, but the effect is nevertheless startling, as he is quickly shrunk to only about three inches high. The nan awakens, and hears the maniacal laughter of the skull bottle above him, looking up to see the skull-face repeat its ominous warning “Death walks tonight!” The man scrambles down from his chair and retreats from the room, entering the darkened front showroom of the shop. From the shelves, he hears an odd and persistent wailing. Above are three baby bottles – each with faces, and wearing a diaper. They sing an aggravating song about not feeling clean or tidy, because no one will change their didy. The old man climbs through the various levels of drawers of a sales counter to the upper shelves, and, rather than perform a diaper change (which would have seemed the more obvious solution to the problem), hr attempts to stage various forms of entertainment to stop the babies’ persistent crying. He begins by attempting to play an atomizer like a bagpipe, with the babies’ wails providing the drone notes. Now the bottles on the shelves get into the act, first a bottle of Scotch (as a singing Scotsman) and his wife, a “little brown jug” of rum. For several minutes, puns abound (for example, a dog -shaped bottle containing “smelling salts”, a disappearing bottle of vanishing cream, a shivering bottle of cold cream, and a father-and-son team of bottles playing on the names of two well-known products which continue to this day – Absorbine and Absorbine Jr. (misspelled “Asorbine” in the film). Interesting character designs are further achieved from a pair of singing rubber gloves, and a basso hot water bottle (who can’t hit the low note in his song, which is instead provided as a gargle from a bottle of “Listrine”).

Developing arms and legs, the bottle pulls out its own stopper-eyedropper, and holds the top of the eyedropper over the head of the old man. With a squeeze, a few drops of the bottle’s contents are deposited upon the old man’s neck. No, he does not die, but the effect is nevertheless startling, as he is quickly shrunk to only about three inches high. The nan awakens, and hears the maniacal laughter of the skull bottle above him, looking up to see the skull-face repeat its ominous warning “Death walks tonight!” The man scrambles down from his chair and retreats from the room, entering the darkened front showroom of the shop. From the shelves, he hears an odd and persistent wailing. Above are three baby bottles – each with faces, and wearing a diaper. They sing an aggravating song about not feeling clean or tidy, because no one will change their didy. The old man climbs through the various levels of drawers of a sales counter to the upper shelves, and, rather than perform a diaper change (which would have seemed the more obvious solution to the problem), hr attempts to stage various forms of entertainment to stop the babies’ persistent crying. He begins by attempting to play an atomizer like a bagpipe, with the babies’ wails providing the drone notes. Now the bottles on the shelves get into the act, first a bottle of Scotch (as a singing Scotsman) and his wife, a “little brown jug” of rum. For several minutes, puns abound (for example, a dog -shaped bottle containing “smelling salts”, a disappearing bottle of vanishing cream, a shivering bottle of cold cream, and a father-and-son team of bottles playing on the names of two well-known products which continue to this day – Absorbine and Absorbine Jr. (misspelled “Asorbine” in the film). Interesting character designs are further achieved from a pair of singing rubber gloves, and a basso hot water bottle (who can’t hit the low note in his song, which is instead provided as a gargle from a bottle of “Listrine”).

Back in the other room, the poison bottle now tinkers with the pharmacist’s laboratory equipment, concocting various mixtures through complicated glass tubing and vials atop heated Bunsen burners. He is cheered in his efforts by a bottle of Witch Hazel (appropriately shaped as a witch), who sinisterly cackles to the audience “Can you take it?” The witch offers a further assist, casting a spell from her fingers that uncorks three bottles, releasing the ghostly “spirits of ammonia”. The three spirits enter the showroom, break up the party within, and deliver a knockout punch from their vapors to the old man, rendering him unconscious. They float him back to the poison bottle’s mysterious brew, and drop him into an open vat at one end. Amidst a row of test tubes holding steaming brews in all colors of the rainbow, the old man is sucked into the distilling tubes and mechanisms of his own chemical set. He travels a maze-like path through the tubes and devices (a setup which would be recreated again in a later studio production, “The Bookworm Turns”), and finally splashes down into a large, bubbling receiving vat. Into this vat the poison bottle has deposited an unexpected device – a pair of scissors, with a ribbon tied to one handle. The scissor floats within the bubbling fluid, driven by its currents to open and close blades at random. The ribbon wraps around the old man’s limbs, restraining his movement. The poison bottle shrieks with laughter as the scissor blades snip closer and closer to sealing the old man’s doom, but the sound of a loud thunderclap shakes and dissolves the picture back to reality, as the old man, back in his chair at full size, awakens out of his fitful dream. He clears his eyes, and realizes the screaming skull is nothing but the poison bottle, and laughs to himself, “Well, bless my soul”, for the iris out.

Back in the other room, the poison bottle now tinkers with the pharmacist’s laboratory equipment, concocting various mixtures through complicated glass tubing and vials atop heated Bunsen burners. He is cheered in his efforts by a bottle of Witch Hazel (appropriately shaped as a witch), who sinisterly cackles to the audience “Can you take it?” The witch offers a further assist, casting a spell from her fingers that uncorks three bottles, releasing the ghostly “spirits of ammonia”. The three spirits enter the showroom, break up the party within, and deliver a knockout punch from their vapors to the old man, rendering him unconscious. They float him back to the poison bottle’s mysterious brew, and drop him into an open vat at one end. Amidst a row of test tubes holding steaming brews in all colors of the rainbow, the old man is sucked into the distilling tubes and mechanisms of his own chemical set. He travels a maze-like path through the tubes and devices (a setup which would be recreated again in a later studio production, “The Bookworm Turns”), and finally splashes down into a large, bubbling receiving vat. Into this vat the poison bottle has deposited an unexpected device – a pair of scissors, with a ribbon tied to one handle. The scissor floats within the bubbling fluid, driven by its currents to open and close blades at random. The ribbon wraps around the old man’s limbs, restraining his movement. The poison bottle shrieks with laughter as the scissor blades snip closer and closer to sealing the old man’s doom, but the sound of a loud thunderclap shakes and dissolves the picture back to reality, as the old man, back in his chair at full size, awakens out of his fitful dream. He clears his eyes, and realizes the screaming skull is nothing but the poison bottle, and laughs to himself, “Well, bless my soul”, for the iris out.

Off to China (Terrytoons/Educational, 3/20/36) barely qualifies for this trail. It is the only black-and-white this week, and the only cartoon showing virtually no improvement from previous seasons. Not that this was not being noticed by Educational’s executives, who were finding themselves being quickly outclassed in the cartoon business. They would within the season give Terry orders to improve the product, or else – an edict that would not achieve startling results, but would gradually lead to development of a few new characters, slightly more fluid animation, longer running times, and some tenuous experimentation in color. In the meanwhile, this excuse for another of Terry’s many aviator cartoons again has an animal crew on an ocean hop, crossing the Pacific instead of the Atlantic for a change. Only the briefest of storm gags are included, and fairly lame ones at that. First, a direct steal from Disney’s The Mail Pilot, with a cat pressing a button on his goggles to activate windshield wipers in the rain. Then, the plane averts a rain cloud by shifting its course at right angles, flying straight up along the edge of the downpour, horizontal over the top of the cloud, then vertical down the other side of the storm front until it reaches its desired elevation. This maneuver is strictly for toony effect, as it obviously would have been aerodynamically more efficient to simply chart an arc course over the cloud rather than take on those impossible straight-line climbs and dives. Over Hawaii, the plane drops a heavy load of mail, its impact briefly submerging and almost sinking the island. The plane finally arrives at the docks in China, and accomplishes its mission – to deliver American dirty linen to the Chinese laundries. Current prints of the film end abruptly in a cut by CBS, leaving question as to whether gags felt racially insensitive were included within the laundries, and another leg of the journey originally documented for the return voyage.

The Old House (Harman-Ising, MGM, Happy Harmonies. 5/2/36 – Hugh Harman, dir.) – A completely redesigned Bosko, Honey, and Bruno (the former two depicted as realistic black children of about six or seven years) star in this atmospheric episode that even begins with a signboard swinging in the breeze of a thunderstorm outside the residence in question. The cartoon proper begins with Bosko telling spook tales to Bruno in his own backyard, giving Bruno the sound advice that the goblins will get ‘ya if you don’t watch out. From behind a tree pops Honey, shouting out “Boo”. Both Bosko and Bruno react in terror, racing in a dead heat to cower inside the relative safety of Bruno’s doghouse. Honey doubles up in laughter, calling Bosko a scaredy cat. She notes that she travels to her grandma’s all the time, right past an old house that is referred to as haunted, and has never been bothered by a spook. Bosko asks what would happen if she met a ghost, and Honey declares he’d be the one who got scared the most, breaking into a song poking fun at the two cowards, “There Ain’t No Spooks Nowhere:” Honey proceeds on her appointed rounds to Grandma’s – but dark clouds gather, and a strong storm breaks out, just as she is passing in front of the haunted house. The gate has fallen off long ago, and what is left of the picket fence sways violently in the breeze, as Honey begins to get soaked in the rain. No other option but to climb upon the porch of the old place. The creaking of boards, snapping of shutters, and moaning of hinges of a front door left unlatched, all begin to give Honey the impression that perhaps it may not be the easiest thing to practice what she preaches. She begins to cautiously creep toward the stairs, looking for an exit from the place, but the wind drives her back, and through the open front door, which then blows shit to add an eerier ambience. All manner of haunted house props make her more leery, including rolling window shades, an organ keyboard that blows dust clouds, and flying bats. She finally stops singing her song, and screams in terror, racing back to the front door. The handle pops off inside, and the door will not budge. Her screams are heard down the road by Bosko and Bruno. Bosko forgets to unlatch Bruno, leaving him chained to his doghouse.

The Old House (Harman-Ising, MGM, Happy Harmonies. 5/2/36 – Hugh Harman, dir.) – A completely redesigned Bosko, Honey, and Bruno (the former two depicted as realistic black children of about six or seven years) star in this atmospheric episode that even begins with a signboard swinging in the breeze of a thunderstorm outside the residence in question. The cartoon proper begins with Bosko telling spook tales to Bruno in his own backyard, giving Bruno the sound advice that the goblins will get ‘ya if you don’t watch out. From behind a tree pops Honey, shouting out “Boo”. Both Bosko and Bruno react in terror, racing in a dead heat to cower inside the relative safety of Bruno’s doghouse. Honey doubles up in laughter, calling Bosko a scaredy cat. She notes that she travels to her grandma’s all the time, right past an old house that is referred to as haunted, and has never been bothered by a spook. Bosko asks what would happen if she met a ghost, and Honey declares he’d be the one who got scared the most, breaking into a song poking fun at the two cowards, “There Ain’t No Spooks Nowhere:” Honey proceeds on her appointed rounds to Grandma’s – but dark clouds gather, and a strong storm breaks out, just as she is passing in front of the haunted house. The gate has fallen off long ago, and what is left of the picket fence sways violently in the breeze, as Honey begins to get soaked in the rain. No other option but to climb upon the porch of the old place. The creaking of boards, snapping of shutters, and moaning of hinges of a front door left unlatched, all begin to give Honey the impression that perhaps it may not be the easiest thing to practice what she preaches. She begins to cautiously creep toward the stairs, looking for an exit from the place, but the wind drives her back, and through the open front door, which then blows shit to add an eerier ambience. All manner of haunted house props make her more leery, including rolling window shades, an organ keyboard that blows dust clouds, and flying bats. She finally stops singing her song, and screams in terror, racing back to the front door. The handle pops off inside, and the door will not budge. Her screams are heard down the road by Bosko and Bruno. Bosko forgets to unlatch Bruno, leaving him chained to his doghouse.

Bosko, however, shifts his running into high gear, and attempts to charge up the front steps into the house. A loose floorboard on the porch smacks him right in the face, shooting him back down to ground level. He turns on the speed again, looking for a back way in. Spotting a slanted cellar door with an open rear window above it, Bosko clambers over the doorway to get in the window – but has the door collapse under his feet, throwing him into the cellar. As he strikes a match to see where he is, his pants catch upon the loose end of a broken mainspring of an old wind-up Victrola gramophone, and as he walks forward, spooky sounds emit from a phonograph needle placed upon a record atop the broken turntable. Bosko also panics, and from there on, all proverbial hell breaks loose (as well as Bruno’s chain, allowing him to get Into the act). Combine Bosko tangled in a sheet, Honey under a dressmaker’s model with a moose head stuck on top, and Bruno running afoul of a physician’s skeleton, and everybody spends the next five minutes frightening the wits out of each other. Bruno adds a radio under his skeletal guise to provide effective screams, causing Bosko to take a shot at him with an old shotgun, the recoil of which blasts Bosko and Honey outdoors. Bruno’s costume is also blasted away, leaving only the radio to announce “And that’s the end of today’s spook story”, as the sun breaks through the clouds overhead for the fade out.

Bold King Cole (Van Buren/RKO, Rainbow Parade (Felix the Cat), 5/29/36 – Burt Gillett, dir.) – Felix the cat sits in a tree on a pleasant spring day, playing a mandolin and singing a cheery song, “Nature and Me”. The mood changes quickly, as a sudden storm erupts. A bolt of lightning hits Felix’s tree, causing it to rise up on its roots like a human struck in the rear. The old gag of lightning sawing a cloud in half is repeated to start the downpour. Another bolt whirls around the tree trunk in a circle, then pauses to saw off the limb Felix is sitting on. Felix now takes a bolt in his own rear, and begins running. Yet another bolt darts under Felix’s belly, leaving him riding the lightning like a wild stallion. Felix and the bolt crash through the hollow limb of a tree. From both ends of the limb, matching pairs of eyes peer out. One is Felix, but the other is from the eyes of a frightened owl, who flies away. More lightning jolts Felix out of the limb, then stabs at him repeatedly, one appearing directly in his path with point jabbed into the ground, causing Felix to scale its jagged edges like the moving steps of an escalator running in the wrong direction. Felix is finally struck in the tail by a bolt, resulting in an unusual phenomenon – Felix’s head lights up like a light bulb, the image of a coiled filament visible inside his skull. Having no idea what to do, Felix runs for help and shelter to the only building nearby – a large castle, located atop a spooky hill, while the storm continues to rage.

Bold King Cole (Van Buren/RKO, Rainbow Parade (Felix the Cat), 5/29/36 – Burt Gillett, dir.) – Felix the cat sits in a tree on a pleasant spring day, playing a mandolin and singing a cheery song, “Nature and Me”. The mood changes quickly, as a sudden storm erupts. A bolt of lightning hits Felix’s tree, causing it to rise up on its roots like a human struck in the rear. The old gag of lightning sawing a cloud in half is repeated to start the downpour. Another bolt whirls around the tree trunk in a circle, then pauses to saw off the limb Felix is sitting on. Felix now takes a bolt in his own rear, and begins running. Yet another bolt darts under Felix’s belly, leaving him riding the lightning like a wild stallion. Felix and the bolt crash through the hollow limb of a tree. From both ends of the limb, matching pairs of eyes peer out. One is Felix, but the other is from the eyes of a frightened owl, who flies away. More lightning jolts Felix out of the limb, then stabs at him repeatedly, one appearing directly in his path with point jabbed into the ground, causing Felix to scale its jagged edges like the moving steps of an escalator running in the wrong direction. Felix is finally struck in the tail by a bolt, resulting in an unusual phenomenon – Felix’s head lights up like a light bulb, the image of a coiled filament visible inside his skull. Having no idea what to do, Felix runs for help and shelter to the only building nearby – a large castle, located atop a spooky hill, while the storm continues to rage.

Inside the palace, a merry monarch rules – Old King Cole. However, while he is in good spirits, his subjects are not. Cole is involved in his favorite habit – bragging, about mythical exploits of bravery and strength that probably never happened. “Was I afraid? Not Old King Cole!”, he boasts – a phrase his subjects never hear the end of. Frantic pounding at the door is heard, as Felix attempts to gain entry from outside. (Even the lightning assists, also knocking on the door alongside him.) The unexpected sound, and the spooky night, lead Cole’s subjects to dive in fear under the palace rug. “Methinks my loyal subjects are not as brave as their brave king”, observes Cole, and he majestically rises from his throne to answer the door himself. That is, until he reaches a corner out of the view of his subjects, and ducks behind it, cowering in fear of the sounds from without. “W-Who’s there?”. he stammers. Felix’s helpless-sounding voice reassures him, and he opens the door, allowing Felix to be blown in by the wind. The cat bounces around, with his head still lit brightly. Oddly, Cole has the solution to Felix’s predicament, and takes hold of Felix’s nose, twisting it one notch. Felix’s light-bulb head flicks off as if someone threw a switch. The two become friends and introduce themselves – leaving Cole an opening to begin his bragging again of not being afraid of anything – even lightning. From the walls of the palace, the visions of others who have heard this bragging too often appear from the frames of palace paintings – the spirits of past rulers and royal family members of the kingdom. “Methinks yon royal braggart is unusually windy today”, one spirit says to another. As Cole continues, one of the spirit voices shouts to him, “Get off the air”. Felix reacts in fright at the thought of ghosts, but Cole insists he doesn’t believe in them. “Neither do we”, responds the ghostly voice. The spirits, having had enough, emerge from their frames, and decide to give Cole “the works”. To a tune of “You talk too much”, they seize Cole, and dispose of Felix by trapping him inside a suit of armor. They march Cole to a dungeon, where they have rigged up a torture device to take “the wind out of him”. Cole is strapped to a table, while an inverted funnel connected to a hose is placed over his mouth. The other end of the hose is attached to a valved air tank, presently empty. From above, a mechanical device is lowered over Cole’s belly, and two heavy weights begin to systematically pound upon him, until his rotund belly is flattened to look like a deflated balloon. The gas from within is collected in the tank, and the valve closed. “Now, we’ll give you a dose of your own medicine”, says one of the ghosts. The valve is opened slowly, leaking gas into Cole’s face. Cole is no longer the man he was, and nervously shakes, wringing his hands together in jittery reaction at what is about to come. His voice is heard from the gas in the tank, uttering the most dreaded words: “Was I afraid? Not Old King Cole!” “STOP”, shouts the deflated Cole, after hearing a few sentences. “Take it away! I’ll never do it again!”

Inside the palace, a merry monarch rules – Old King Cole. However, while he is in good spirits, his subjects are not. Cole is involved in his favorite habit – bragging, about mythical exploits of bravery and strength that probably never happened. “Was I afraid? Not Old King Cole!”, he boasts – a phrase his subjects never hear the end of. Frantic pounding at the door is heard, as Felix attempts to gain entry from outside. (Even the lightning assists, also knocking on the door alongside him.) The unexpected sound, and the spooky night, lead Cole’s subjects to dive in fear under the palace rug. “Methinks my loyal subjects are not as brave as their brave king”, observes Cole, and he majestically rises from his throne to answer the door himself. That is, until he reaches a corner out of the view of his subjects, and ducks behind it, cowering in fear of the sounds from without. “W-Who’s there?”. he stammers. Felix’s helpless-sounding voice reassures him, and he opens the door, allowing Felix to be blown in by the wind. The cat bounces around, with his head still lit brightly. Oddly, Cole has the solution to Felix’s predicament, and takes hold of Felix’s nose, twisting it one notch. Felix’s light-bulb head flicks off as if someone threw a switch. The two become friends and introduce themselves – leaving Cole an opening to begin his bragging again of not being afraid of anything – even lightning. From the walls of the palace, the visions of others who have heard this bragging too often appear from the frames of palace paintings – the spirits of past rulers and royal family members of the kingdom. “Methinks yon royal braggart is unusually windy today”, one spirit says to another. As Cole continues, one of the spirit voices shouts to him, “Get off the air”. Felix reacts in fright at the thought of ghosts, but Cole insists he doesn’t believe in them. “Neither do we”, responds the ghostly voice. The spirits, having had enough, emerge from their frames, and decide to give Cole “the works”. To a tune of “You talk too much”, they seize Cole, and dispose of Felix by trapping him inside a suit of armor. They march Cole to a dungeon, where they have rigged up a torture device to take “the wind out of him”. Cole is strapped to a table, while an inverted funnel connected to a hose is placed over his mouth. The other end of the hose is attached to a valved air tank, presently empty. From above, a mechanical device is lowered over Cole’s belly, and two heavy weights begin to systematically pound upon him, until his rotund belly is flattened to look like a deflated balloon. The gas from within is collected in the tank, and the valve closed. “Now, we’ll give you a dose of your own medicine”, says one of the ghosts. The valve is opened slowly, leaking gas into Cole’s face. Cole is no longer the man he was, and nervously shakes, wringing his hands together in jittery reaction at what is about to come. His voice is heard from the gas in the tank, uttering the most dreaded words: “Was I afraid? Not Old King Cole!” “STOP”, shouts the deflated Cole, after hearing a few sentences. “Take it away! I’ll never do it again!”

Back at the palace entrance, Felix is struggling inside the armor suit, as one ghost who has stayed behind as a guard claps out a rhythm as if Felix is performing a square dance. The armor suddenly topples, and Felix is freed. The ghost pursues him, catching up to Felix in close proximity to an open palace window. Suddenly, a bolt of lightning strikes through the window, hitting the ghost, and causing him to disappear completely. Observing this phenomenon, Felix gets an idea. He carries the top half of the suit of armor over to the window, and sticks out one metal arm through the window as a lightning rod. As the lightning is drawn to it, Felix opens a trap door to the dungeons below, and aims the other arm of the armor through the door like the barrel of a rifle. The device works to perfection, as lightning is drawn and channeled through the armor into the dungeon. The ghosts are picked off one by one, some from places of hiding (including one who hides inside a piano, causing the lightning to tap out a tune on the piano keys until the curious ghost opens the lid – then zap him). “We win”, shouts Felix, as the last ghost is obliterated. Cole slips out of his bonds, but hasn’t really learned any lesson at all. Instead, he merely inhales the remaining contents of the gas tank, and becomes his own boasting inflated self again. He crowns Felix a prince for his bravery, both of them declaring they’re not afraid of anything. Cole toys with Felix, turning his nose to re-light the electric bulb within him. Felix pulls a surprise, pushing a jewel in the center of Cole’s belt buckle like a button, lighting up Cole’s head in similar fashion. They laugh to each other at the mutual joke, for the iris out.

Back at the palace entrance, Felix is struggling inside the armor suit, as one ghost who has stayed behind as a guard claps out a rhythm as if Felix is performing a square dance. The armor suddenly topples, and Felix is freed. The ghost pursues him, catching up to Felix in close proximity to an open palace window. Suddenly, a bolt of lightning strikes through the window, hitting the ghost, and causing him to disappear completely. Observing this phenomenon, Felix gets an idea. He carries the top half of the suit of armor over to the window, and sticks out one metal arm through the window as a lightning rod. As the lightning is drawn to it, Felix opens a trap door to the dungeons below, and aims the other arm of the armor through the door like the barrel of a rifle. The device works to perfection, as lightning is drawn and channeled through the armor into the dungeon. The ghosts are picked off one by one, some from places of hiding (including one who hides inside a piano, causing the lightning to tap out a tune on the piano keys until the curious ghost opens the lid – then zap him). “We win”, shouts Felix, as the last ghost is obliterated. Cole slips out of his bonds, but hasn’t really learned any lesson at all. Instead, he merely inhales the remaining contents of the gas tank, and becomes his own boasting inflated self again. He crowns Felix a prince for his bravery, both of them declaring they’re not afraid of anything. Cole toys with Felix, turning his nose to re-light the electric bulb within him. Felix pulls a surprise, pushing a jewel in the center of Cole’s belt buckle like a button, lighting up Cole’s head in similar fashion. They laugh to each other at the mutual joke, for the iris out.

To Spring (Harman-Ising, Happy Harmonies, 6/20/36 – William Hanna, dir.) – The impressive and innovative directorial debut of William Hanna, in an epic episode that literally utilizes about every shade of paint that the MGM color mixers could conceive. After many years of seeing and studying this film, it is amazing that, with its massive artistic complexity, only one shot seems flawed in its execution – a perspective cycle shot of underground ore cars transporting rainbow-colored rocks, in which the painters get confused as to the color of the rucks in the top third of the pile, which change from cel to cel. Other than that, quality checking appears to have been top-notch, presenting the most lavish and expensive explanation ever for the change of the seasons.

To Spring (Harman-Ising, Happy Harmonies, 6/20/36 – William Hanna, dir.) – The impressive and innovative directorial debut of William Hanna, in an epic episode that literally utilizes about every shade of paint that the MGM color mixers could conceive. After many years of seeing and studying this film, it is amazing that, with its massive artistic complexity, only one shot seems flawed in its execution – a perspective cycle shot of underground ore cars transporting rainbow-colored rocks, in which the painters get confused as to the color of the rucks in the top third of the pile, which change from cel to cel. Other than that, quality checking appears to have been top-notch, presenting the most lavish and expensive explanation ever for the change of the seasons.

As the world of nature, depicted in exquisite and realistic detail, almost as if a tone poem, begins the first signs of thaw and flowing of streams after a cold winter, the drippings from a deposit of thawing snow form a trickle of water that penetrates deep into the ground and into the caverns of the earth, where we see them slowly but systematically propelling the gears and hands of a water clock, its dial not marked for hours, but for seasons. Its chimes awaken an elderly, short-bearded gnome from a long winter’s snooze. He wipes his eyes, deals with one foot that is still asleep, then reacts with a start at the reading on the clock. “Jeepers creepers! Jumping gee! Time for Spring!” He races around a maze of underground caverns, awakening other younger gnomes throughout the tunnels, then hammering out a “Bong” on a large triangular gong to ensure that everyone is awake. In rhyme, he issues orders from a high ledge to his legion of gnomes below, including to stoke the furnaces, gather colors, and watch the charts. One shot is animated in dramatic facial shadowing, giving the gnome an air or eerie realism, as he is seen in extreme closeup, shouting “Time for Spring, I say!

As the world of nature, depicted in exquisite and realistic detail, almost as if a tone poem, begins the first signs of thaw and flowing of streams after a cold winter, the drippings from a deposit of thawing snow form a trickle of water that penetrates deep into the ground and into the caverns of the earth, where we see them slowly but systematically propelling the gears and hands of a water clock, its dial not marked for hours, but for seasons. Its chimes awaken an elderly, short-bearded gnome from a long winter’s snooze. He wipes his eyes, deals with one foot that is still asleep, then reacts with a start at the reading on the clock. “Jeepers creepers! Jumping gee! Time for Spring!” He races around a maze of underground caverns, awakening other younger gnomes throughout the tunnels, then hammering out a “Bong” on a large triangular gong to ensure that everyone is awake. In rhyme, he issues orders from a high ledge to his legion of gnomes below, including to stoke the furnaces, gather colors, and watch the charts. One shot is animated in dramatic facial shadowing, giving the gnome an air or eerie realism, as he is seen in extreme closeup, shouting “Time for Spring, I say!

In incredible detail, we receive a visual tour of what amounts to an underground foundry, where the juices of spring are produced via volcanic boilers, endless caverns of rainbow-colored stalactites/stalagmites, and a maze of test tubes (borrowed from “Bottles”), waterfalls, and glass feeder tubes to the surface, through which molten colors carved from the stalagmites are brewed in huge boiling pots like a steel mill, then pumped to the surface to feed the flowers and plants at the pull of a large wooden switch-handle. The effects of the tour are pure spectacle, and among the most complex scenes ever created for an animated short (or for that matter, many an animated feature). The old gnome presides over all this orchestrated beehive of activity, to a memorable musical score, never noticing that one gnome is absent – a burly fellow, who seems unable to get his feet through his pantlegs in rising from bed.

But there is a flaw in the master plan. Old Man Winter, in the form of a huffing, puffing cloud with a basso voice and a braggadocio attitude, hasn’t decided its time to leave yet, and laughs at the gnomes for starting spring before he’s gone. He blows with all his might, chilling the just-budding flowers and trees, and forcing their growth to retreat into their stems and roots. The spring essences being pumped to the plants are suddenly forced backwards through the tubing system. They sprout like geysers in the caverns below, plugging up the progress of the waterfalls, and begin flooding the caverns. A rainbow of fluids begins to surround the old gnome’s feet, and the master lever is snapped backwards into off position. “STOP!” shouts the old gnome to his crew. All is halted, long enough to hear Old Man Winter above boasting that he’s not ready to go. “Blast that blowin’ buzzard back! Time for Spring, I say!”, shouts the old gnome. The rest of the gnomes begin their hammering, boiling, and pumping with a will, trying to force the spring juices to the surface in spite of the winter winds. The old gnome struggles to push the control lever into on-position, but it repeatedly snaps back against his efforts. The competing forces of the pumps and wind have nowhere to vent, and the flood of Technicolor rises below the gnome’s feet, until he can no longer maintain his footing, and begins being swept backwards by the current, holding on to a stalagmite stub in an effort not to be swept away. Back deep within the caverns, the burly gnome is still fussing with his pant leg, but somehow notices the commotion and chaos going on below. Pant leg or no pant leg, he sees the call of duty, and wraps the loose length of trousers over his shoulder, climbing down the ladder into the workrooms. He catches up with the old gnome, and wades out to him, rescuing him from his rocky refuge. With the younger gnome’s support, the old gnome is pushed forward, back to the master control. With concerted effort, both gnomes tug with might and main at the switch, and finally succeed in forcing it into open position. The color juices in the tubes bubble and spurt, and reverse direction, again proceeding upwards into the plant stems. In spite of the cold winds, buds begin to bloom. Old Man Winter has exerted himself to the limit, and stops blowing, admitting despite a self-effacing laugh that he is out of snow, and will have to go. But he continues to challenge that he’ll be back when it is his time, and then vanishes from view. The underground pipe system now performs as designed, and the tubes steam in every color melodically. Without any further shots of the gnomes, we receive a tableau of realistic shots of spring blooms, birds returning, and finally the gentle falling of flower petals into a brook, the rippling of the water as they fall framing the gentle fade out of the film. A naturalistic masterpiece.

But there is a flaw in the master plan. Old Man Winter, in the form of a huffing, puffing cloud with a basso voice and a braggadocio attitude, hasn’t decided its time to leave yet, and laughs at the gnomes for starting spring before he’s gone. He blows with all his might, chilling the just-budding flowers and trees, and forcing their growth to retreat into their stems and roots. The spring essences being pumped to the plants are suddenly forced backwards through the tubing system. They sprout like geysers in the caverns below, plugging up the progress of the waterfalls, and begin flooding the caverns. A rainbow of fluids begins to surround the old gnome’s feet, and the master lever is snapped backwards into off position. “STOP!” shouts the old gnome to his crew. All is halted, long enough to hear Old Man Winter above boasting that he’s not ready to go. “Blast that blowin’ buzzard back! Time for Spring, I say!”, shouts the old gnome. The rest of the gnomes begin their hammering, boiling, and pumping with a will, trying to force the spring juices to the surface in spite of the winter winds. The old gnome struggles to push the control lever into on-position, but it repeatedly snaps back against his efforts. The competing forces of the pumps and wind have nowhere to vent, and the flood of Technicolor rises below the gnome’s feet, until he can no longer maintain his footing, and begins being swept backwards by the current, holding on to a stalagmite stub in an effort not to be swept away. Back deep within the caverns, the burly gnome is still fussing with his pant leg, but somehow notices the commotion and chaos going on below. Pant leg or no pant leg, he sees the call of duty, and wraps the loose length of trousers over his shoulder, climbing down the ladder into the workrooms. He catches up with the old gnome, and wades out to him, rescuing him from his rocky refuge. With the younger gnome’s support, the old gnome is pushed forward, back to the master control. With concerted effort, both gnomes tug with might and main at the switch, and finally succeed in forcing it into open position. The color juices in the tubes bubble and spurt, and reverse direction, again proceeding upwards into the plant stems. In spite of the cold winds, buds begin to bloom. Old Man Winter has exerted himself to the limit, and stops blowing, admitting despite a self-effacing laugh that he is out of snow, and will have to go. But he continues to challenge that he’ll be back when it is his time, and then vanishes from view. The underground pipe system now performs as designed, and the tubes steam in every color melodically. Without any further shots of the gnomes, we receive a tableau of realistic shots of spring blooms, birds returning, and finally the gentle falling of flower petals into a brook, the rippling of the water as they fall framing the gentle fade out of the film. A naturalistic masterpiece.

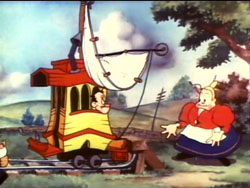

Trolley Ahoy (Van Buren/RKO, Rainbow Parade (Toonerville Folks), 7/3/36 – Tom Palmer, dir. (Earlier sources credit Burt Gillett – original title recreations possibly in dispute)) – One of three shorts produced in the final days of Van Buren based upon Fontaine Fox’s famous “Toonerville” comic strip. Three characters comprise its cast – the Skipper (a bewhiskered Farmer Al Falfa look-alike, who is engineer and conductor of the Toonerville Trolley, a diminutive antiquated trolley that always seems to hold more passengers than its outside dimensions would lead one to believe possible), his wife Katrinka (a Swedish-accented, rotund amazon of a woman with super-strength and never-ending good nature), and Mr. Bang (a hot-tempered bundle of fury, always complaining about the world, who seems to be the trolley’s one steady passenger, for lack of other available public transportation).

Trolley Ahoy (Van Buren/RKO, Rainbow Parade (Toonerville Folks), 7/3/36 – Tom Palmer, dir. (Earlier sources credit Burt Gillett – original title recreations possibly in dispute)) – One of three shorts produced in the final days of Van Buren based upon Fontaine Fox’s famous “Toonerville” comic strip. Three characters comprise its cast – the Skipper (a bewhiskered Farmer Al Falfa look-alike, who is engineer and conductor of the Toonerville Trolley, a diminutive antiquated trolley that always seems to hold more passengers than its outside dimensions would lead one to believe possible), his wife Katrinka (a Swedish-accented, rotund amazon of a woman with super-strength and never-ending good nature), and Mr. Bang (a hot-tempered bundle of fury, always complaining about the world, who seems to be the trolley’s one steady passenger, for lack of other available public transportation).

This morning finds Bang in the usual mood – ranting and raving as to getting out the door of his home late, and knocking down the roof of his porch onto himself from slamming the front door too hard. He makes it to the trolley station just on time, but no trolley. Furious, he kicks at one of the track rails, which compress against each other along the track like a spring, then recoil back into original position, stubbing Bang in the toe. Bang follows the tracks back to their source, finding the trolley at the head of the tracks, but without the Skipper. The Skipper is still in his house, enjoying a pancake breakfast. Bang reaches in the window of the kitchen, pounding on the Skipper’s table in frustration at the old-timer not being at his post in the trolley. The table-pounding launches three pancakes off the plate, and speared upon Bang’s upraised finger. “Hold it, Mr. Bang”, says the Skipper, pouring syrup and butter upon the pancakes and Mr. Bang’s finger, then gobbling the breakfast in one slurp off of Mr. Bang’s digit. Bang is humiliated, and threatens to sue, but the calm Skipper tells him to hold his horses, stating he’ll still get Bang to his train connection on time. Bang shouts that the trolley hasn’t been on time in years, and the Skipper bets him it will be today – for a bet of $10.

Bang enters the trolley, and the Skipper turns the crank to power it up, while Katrinka endlessly waves goodbye from the window. However, nothing happens. “The power’s off”, reacts the Skipper in surprise. He runs to a phone on a local telephone pole, and rings up the power station. He is told his power will stay off – until he pays his power bill. The Skipper complains that he is one of their oldest customers, but receives reply that they don’t care how old he is – he still has to pay. “Why you ding-busted profiteer. This is costing me ten dollars!”, shouts the Skipper, but the power station hangs up. “Katrinka, do something!”, shouts the Skipper. Katrinka runs outside to a clothesline, responding “Katrinka fix”. She yanks the poles of the clothesline from the ground, taking along a large white sheet fastened to the rope by clothespins. She then jabs the poles into the roof of the trolley, one vertically, one horizontally – producing a jib sail from the sheet to power the trolley by wind. With a tremendous exhale, Katrinka blows the trolley at a good speed down the track. The Skipper improvises a lyric to “Sailing, Sailing”, manipulating the lower clothes pole like a spanker gaff to catch the wind. All seems to be going well, until the trolley approaches the crest of a small hill. Instead of descending down the other side, its sail carries the trolley into the air. While the car eventually returns to the tracks, its driver and passenger suffer a bumpy ride, barely hanging on from the rear, then bounced around to the point where the Skipper is ejected ahead of the car, taking repeated blows from it in the rear end like swift kicks.

Bang enters the trolley, and the Skipper turns the crank to power it up, while Katrinka endlessly waves goodbye from the window. However, nothing happens. “The power’s off”, reacts the Skipper in surprise. He runs to a phone on a local telephone pole, and rings up the power station. He is told his power will stay off – until he pays his power bill. The Skipper complains that he is one of their oldest customers, but receives reply that they don’t care how old he is – he still has to pay. “Why you ding-busted profiteer. This is costing me ten dollars!”, shouts the Skipper, but the power station hangs up. “Katrinka, do something!”, shouts the Skipper. Katrinka runs outside to a clothesline, responding “Katrinka fix”. She yanks the poles of the clothesline from the ground, taking along a large white sheet fastened to the rope by clothespins. She then jabs the poles into the roof of the trolley, one vertically, one horizontally – producing a jib sail from the sheet to power the trolley by wind. With a tremendous exhale, Katrinka blows the trolley at a good speed down the track. The Skipper improvises a lyric to “Sailing, Sailing”, manipulating the lower clothes pole like a spanker gaff to catch the wind. All seems to be going well, until the trolley approaches the crest of a small hill. Instead of descending down the other side, its sail carries the trolley into the air. While the car eventually returns to the tracks, its driver and passenger suffer a bumpy ride, barely hanging on from the rear, then bounced around to the point where the Skipper is ejected ahead of the car, taking repeated blows from it in the rear end like swift kicks.

Back at the Skipper’s home, a new development occurs. A cyclone, looking suspiciously like the one from Mickey’s “The Band Concert” seen last week, touches down in the Skipper’s back yard. Katrinka chases after it with a broom, only to have its bristles pulled off by the whirling wind. “Oh, you make me so full of mad”, reacts Katrinka. The funnel commences gobbling things up, developing an appetite for railroad track – and begins to follow the route of the trolley, swallowing every rail and crossbeam as it goes. “I tell Skipper on you”, threatens Katrinka, running after it down the empty track bed. Far ahead, the trolley is finally stabilizing in its run, as the cyclone approaches at double-speed from behind it. Mr. Bang’s shout of warning comes too late, and the trolley is swept up inside the funnel, while Katrinka still follows at a distance behind. A precarious ride follows for the Skipper and Bang, as the trolley averts near collisions with other objects swept up in the cyclone – including traveling through the door of a entire barn caught in the whirlwind, and being pelted with eggs and chicken feathers from within. The trolley emerges from the top of the cyclone, and is ejected. It falls, landing atop the engine of the very train Mr. Bang was trying to catch. However, riding atop a locomotive boiler is not exactly conducive to one’s health, as the belching smoke from the engine nearly suffocates Bang and the Skipper. “Stop the train”, yells the Skipper to the engineer. The engineer attempts to let off steam, but only blows it through the floorboards of the trolley, straight into Mr. Bang’s pants. “Look out! Here comes a tunnel”, cries the Skipper, as a low tunnel collides with the trolley, sending it into a cartwheel spin atop the cars of the train, with Mr. Bang in the lead trying to outrace it across the roofs. He runs out of running room before reaching the end of the train, and dives through the roof of the caboose, while the trolley flies off the caboose roof, landing in a tree. Bang is rescued by a conductor, who discovers him with his feet through the floor of the caboose, running for his life to keep up with the track speeding below. The Skipper shouts from the trolley’s perch for Bang to come back, insisting that Bang made his train, so the Skipper won the bet. Katrinka finally catches up, and again assures the Skipper that she will “fix” the situation. She grabs hold of the railroad tracks at the mouth of the tunnel, and starts hauling, dragging the track backwards through the tunnel – until her impossible feat succeeds in dragging the train back through the tunnel as well. She holds the train motionless by the caboose rail, until Bang emerges and pays off his $10 wager. “Well, it was worth it. First time the trolley was on time”, he grumbles. Katrinka releases the train, and the Skipper splits the profits with her 50-50 for the iris out.

Back at the Skipper’s home, a new development occurs. A cyclone, looking suspiciously like the one from Mickey’s “The Band Concert” seen last week, touches down in the Skipper’s back yard. Katrinka chases after it with a broom, only to have its bristles pulled off by the whirling wind. “Oh, you make me so full of mad”, reacts Katrinka. The funnel commences gobbling things up, developing an appetite for railroad track – and begins to follow the route of the trolley, swallowing every rail and crossbeam as it goes. “I tell Skipper on you”, threatens Katrinka, running after it down the empty track bed. Far ahead, the trolley is finally stabilizing in its run, as the cyclone approaches at double-speed from behind it. Mr. Bang’s shout of warning comes too late, and the trolley is swept up inside the funnel, while Katrinka still follows at a distance behind. A precarious ride follows for the Skipper and Bang, as the trolley averts near collisions with other objects swept up in the cyclone – including traveling through the door of a entire barn caught in the whirlwind, and being pelted with eggs and chicken feathers from within. The trolley emerges from the top of the cyclone, and is ejected. It falls, landing atop the engine of the very train Mr. Bang was trying to catch. However, riding atop a locomotive boiler is not exactly conducive to one’s health, as the belching smoke from the engine nearly suffocates Bang and the Skipper. “Stop the train”, yells the Skipper to the engineer. The engineer attempts to let off steam, but only blows it through the floorboards of the trolley, straight into Mr. Bang’s pants. “Look out! Here comes a tunnel”, cries the Skipper, as a low tunnel collides with the trolley, sending it into a cartwheel spin atop the cars of the train, with Mr. Bang in the lead trying to outrace it across the roofs. He runs out of running room before reaching the end of the train, and dives through the roof of the caboose, while the trolley flies off the caboose roof, landing in a tree. Bang is rescued by a conductor, who discovers him with his feet through the floor of the caboose, running for his life to keep up with the track speeding below. The Skipper shouts from the trolley’s perch for Bang to come back, insisting that Bang made his train, so the Skipper won the bet. Katrinka finally catches up, and again assures the Skipper that she will “fix” the situation. She grabs hold of the railroad tracks at the mouth of the tunnel, and starts hauling, dragging the track backwards through the tunnel – until her impossible feat succeeds in dragging the train back through the tunnel as well. She holds the train motionless by the caboose rail, until Bang emerges and pays off his $10 wager. “Well, it was worth it. First time the trolley was on time”, he grumbles. Katrinka releases the train, and the Skipper splits the profits with her 50-50 for the iris out.

More tricks from ‘36, and pennies from heaven in ‘37, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

I am left speechless! This is perhaps the best group of cartoons to be posted here in this thread. Those who know me will understand my memory of “ the old House“; my only regret is that I never saw this on the big screen in full color! Someday, some fine day, maybe we will see this fully restored and be able to really take a decent look at the deep rich detail and play on the dark and light of this cartoon. it shares bits of score with “bottles“, the previous cartoon. However, I am sure that the look of the cartoon is as interesting as “ the old House“. what is even more interesting is the fact that at least three of these cartoons were seen by me on local television in grainy black-and-white. I also remember bits and pieces of the TOONERVILLE TROLLY and FELIX THE CAT cartoons, and regarding the latter, I wondered about his voice in this cartoon and who did it. Either way, this is an impressive group of storm sequence cartoons! And thank you, of course, as always for posting so much detail that I am sure I missed upon originally seeing these.

All of the “Animation Trails” posts have been rewarding and worth reading, but today’s column — and impressive array of diverse cartoons — really hit the spot. Thanks!

MGM’s early Technicolor masterpieces are breathtaking. “To Spring” was a staple of public domain video collections, often transferred from prints whose quality failed to do it justice, so it’s easy to take the cartoon for granted. But what a thrill it must have been to see on the big screen. Depression-era audiences seeing it at the movies for the first time must have gasped audibly at every change of scene and then applauded when it was over.

It’s interesting that in “Bottles”, the brand names of products made by American companies were altered (if only slightly), while those from other countries, like Bacardi, were left unchanged. There really was a Golliwogg perfume, sold in bottles exactly like the ones in the cartoon, and spelled with two Gs. But it was made by a French company.

I’m actually partial to “Off to China”, but I have to admit that it suffers in comparison to the rest of this week’s offerings.

The “Bottles” short was on Toon In With Me a few times. So glad that program is on MeTV.

I wonder what kind of budgets were involved in these selections? I know that MGM seemed to be oblivous when it came to spending money, and Terry was just the opposite. Any clue as to the amounts involved?

Since one else so far has quoted the immortal lyric, I will:

We don’t feel like singing hidee [as in Cab Calloway’s “Hidee-ho!”]

No one here will change our didey

That’s the reason why

All we do is cry

Waah-waah-waah-waah waah-waah-waah waah-waah-waah-waah waah-waah-waah, etc.

“Bottles” is a great cartoon, one of my all-time favorites, even though it rather frightened me as a child.

Speaking of music, the best piece in “Summertime” is the honky-tonk bit as the mail bunny skips along to deliver the news to Mister Ground Hog.

Here’s what Walt Disney thought of “To Spring”: “They got colors everywhere and it looks cheap. There is nothing subtle about it at all. It looks poster-like.” He’d probably have insisted on better-looking gnomes, and made it clearer exactly what they’re doing, which is hard to tell on first viewing. The outdoor scenes look like the opening credits of “Gone With the Wind” without the plantation (and the credits).