Perhaps late 1934 and early ‘35 would have classified in the almanacs as an El Niño season – as, in the animated world, heavy rain and snow appear to dominate. We’ll measure the prevailing winds that blow our toons into impossible situations in this article installment, watching them triumph over the elements or be merely left hung out to dry.

Shiver Me Timbers (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 7/27/34 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/William Sturm, anim.) – A classic Popeye, putting the sailor in a classic nautical setting – that of an abandoned ghost ship. (Oddly, Popeye would end his theatrical career on the same note, with the 1957 short, “Spooky Swabs”.) The mariner and his crew of Olive and Wimpy, in their random travels that often set up early episodes of the series, happen upon a beached hulk of a square-rigger, its masts tattered and its hull weather-beaten with holes. Not that the ship doesn’t give them fair warning of danger. Someone has taken the effort to post a sign on its bow reading “Ghost Ship – Beware”, which then transforms its letters into a neon “Keep Off”. But an inviting rope ladder which falls over the side is more than Popeye can resist, and he determines to “investigate” the situation. We know trouble awaits, as the rope ladder disappears rung by rung behind Wimpy as he climbs it. Then, the whole ship rocks, and, under its own mysterious power, it breaks loose from the sand and launches into the sea. Our heroes and heroine deal with various mysterious goings-on, including temptation of Wimpy with a galley full of ghost hamburgers, which return to the tray through the cheeks of Wimpy as soon as they are eaten (very low in calories), loose floorboards that play a xylophone tune everywhere that Popeye walks on deck, and Olive falling into a barrel of flour with a pail of water added for good measure, to emerge a sticky white mess and be mistaken for a ghost. As Popeye beats the tar out of the “spirit”, only to reveal a battered Olive under the paste, he reassures his crew that there “ain’t no such thing as ghosts”. “Oh, yeah?”, responds a quartet of pirate ghosts that emerge from nowhere, tackling our heroes and placing them in various forms of torture or peril.

Shiver Me Timbers (Fleischer/Paramount, Popeye, 7/27/34 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Willard Bowsky/William Sturm, anim.) – A classic Popeye, putting the sailor in a classic nautical setting – that of an abandoned ghost ship. (Oddly, Popeye would end his theatrical career on the same note, with the 1957 short, “Spooky Swabs”.) The mariner and his crew of Olive and Wimpy, in their random travels that often set up early episodes of the series, happen upon a beached hulk of a square-rigger, its masts tattered and its hull weather-beaten with holes. Not that the ship doesn’t give them fair warning of danger. Someone has taken the effort to post a sign on its bow reading “Ghost Ship – Beware”, which then transforms its letters into a neon “Keep Off”. But an inviting rope ladder which falls over the side is more than Popeye can resist, and he determines to “investigate” the situation. We know trouble awaits, as the rope ladder disappears rung by rung behind Wimpy as he climbs it. Then, the whole ship rocks, and, under its own mysterious power, it breaks loose from the sand and launches into the sea. Our heroes and heroine deal with various mysterious goings-on, including temptation of Wimpy with a galley full of ghost hamburgers, which return to the tray through the cheeks of Wimpy as soon as they are eaten (very low in calories), loose floorboards that play a xylophone tune everywhere that Popeye walks on deck, and Olive falling into a barrel of flour with a pail of water added for good measure, to emerge a sticky white mess and be mistaken for a ghost. As Popeye beats the tar out of the “spirit”, only to reveal a battered Olive under the paste, he reassures his crew that there “ain’t no such thing as ghosts”. “Oh, yeah?”, responds a quartet of pirate ghosts that emerge from nowhere, tackling our heroes and placing them in various forms of torture or peril.

Olive is tied to a mast, with her bare feet revealed for a tickle torture from two black cats licking her toes. Wimpy is chained to another mast, with a table of roast turkey that dodges to remain just out of his reach. Popeye is suspended in the upper rigging, being swung back and forth to clunk his head and spine against the fore and main masts, then a floating sword cuts the rope above him, crashing him through the decl. In a cabin below, several ghosts attack him with various objects, but Popeye can’t fight back, as his blows merely go through their ectoplasm. He hits on a solution by luring them into a cold-storage meat locker (amazing it still has sufficient ice inside after the length of time the ship has probably been wrecked), then locks the spooks in to become ice cubes. Emerging on the main deck, Popeye encounters the “skeleton crew” cavorting about, one of whom assaults him with a ball of flame from the ship’s boiler. Now, mother nature gets into the act. The waves begin to kick up, rocking the ship fiercely, and lightning bolts strike to transform into the shape of a huge axe, chopping down the mizzen mast, which falls only inches behind Popeye’s back. Even our steadfast sailor goes into a case of the shudders, which can only be cured by a heathy dose of spinach. Once his power kicks in, nothing can stop him. He socks various skeletons, transforming them into rolling pairs of dice, and ivory pool balls that roll into various holes in the deck. Lightning strikes Popeye, and a storm cloud appears before him to do battle, while from behind him, the waves begin to sock Popeye from over the railing, and a hideous laughing face forms within the crest of a wave to jeer at him. Popeye socks away the cloud, then lands a blow directly on the wave’s jaw. The wave trembles, and begins to shrink. A view of the entire ocean reveals all of its watery crests performing the same trembling shrivel, and the water’s surface flattens out entirely as the skies also clear, settling into a placid scene of clear seas illuminated by moonlight. Popeye assumes a position at the battered but functional ship’s wheel, along with Olive and Wimpy who are somehow freed without on-screen rescue by Popeye, and the three head for home with Popeye in command, to the usual musical ride-out of Popeye’s theme.

Olive is tied to a mast, with her bare feet revealed for a tickle torture from two black cats licking her toes. Wimpy is chained to another mast, with a table of roast turkey that dodges to remain just out of his reach. Popeye is suspended in the upper rigging, being swung back and forth to clunk his head and spine against the fore and main masts, then a floating sword cuts the rope above him, crashing him through the decl. In a cabin below, several ghosts attack him with various objects, but Popeye can’t fight back, as his blows merely go through their ectoplasm. He hits on a solution by luring them into a cold-storage meat locker (amazing it still has sufficient ice inside after the length of time the ship has probably been wrecked), then locks the spooks in to become ice cubes. Emerging on the main deck, Popeye encounters the “skeleton crew” cavorting about, one of whom assaults him with a ball of flame from the ship’s boiler. Now, mother nature gets into the act. The waves begin to kick up, rocking the ship fiercely, and lightning bolts strike to transform into the shape of a huge axe, chopping down the mizzen mast, which falls only inches behind Popeye’s back. Even our steadfast sailor goes into a case of the shudders, which can only be cured by a heathy dose of spinach. Once his power kicks in, nothing can stop him. He socks various skeletons, transforming them into rolling pairs of dice, and ivory pool balls that roll into various holes in the deck. Lightning strikes Popeye, and a storm cloud appears before him to do battle, while from behind him, the waves begin to sock Popeye from over the railing, and a hideous laughing face forms within the crest of a wave to jeer at him. Popeye socks away the cloud, then lands a blow directly on the wave’s jaw. The wave trembles, and begins to shrink. A view of the entire ocean reveals all of its watery crests performing the same trembling shrivel, and the water’s surface flattens out entirely as the skies also clear, settling into a placid scene of clear seas illuminated by moonlight. Popeye assumes a position at the battered but functional ship’s wheel, along with Olive and Wimpy who are somehow freed without on-screen rescue by Popeye, and the three head for home with Popeye in command, to the usual musical ride-out of Popeye’s theme.

The Discontented Canary (Harman-Ising/MGM, A Metro Color Cartoon, 9/1/34 – Rudolf Ising, dir.) – Harman and Ising’s debut film for MGM, and their first in color. The negatives have seen considerable deterioration over the years, exhibiting some signs of frame flash even as early as original 16mm TV prints and Pictoreels home movie editions. The original credits, which were considerably off in processing even in early prints, must have been impressive, as, despite being limited to only Technicolor 2-strip stock, they appear to have cross-dissolved the titling into 5 different color schemes. (Current prints show only two, without even the frames for the cross-dissolve.) Storyline is simple and presented in traditional 1930’s fashion. A caged canary sees birds out the window, and dreams of a life of freedom. He takes advantage of his owner’s careless leaving of the cage door unlatched, and flies out for adventures in the outside world. However, he finds shelter at a premium, with bird houses filled to capacity, and endures the pursuit of a hungry cat and the dangers of a lightning storm, causing him to ultimately return gladly to his cage, and sing the praises of “Home Sweet Home.” Animation is a cut above the director’s previous efforts for Warner Brothers, though still attempting to find its own way, some elements of animation (such as the cat) bearing resemblances to earlier models such as used in “It’s Got Me Again”, and human animation of the old lady who owns the bird being highly rigid and lacking in either fluidity or realism.

The Discontented Canary (Harman-Ising/MGM, A Metro Color Cartoon, 9/1/34 – Rudolf Ising, dir.) – Harman and Ising’s debut film for MGM, and their first in color. The negatives have seen considerable deterioration over the years, exhibiting some signs of frame flash even as early as original 16mm TV prints and Pictoreels home movie editions. The original credits, which were considerably off in processing even in early prints, must have been impressive, as, despite being limited to only Technicolor 2-strip stock, they appear to have cross-dissolved the titling into 5 different color schemes. (Current prints show only two, without even the frames for the cross-dissolve.) Storyline is simple and presented in traditional 1930’s fashion. A caged canary sees birds out the window, and dreams of a life of freedom. He takes advantage of his owner’s careless leaving of the cage door unlatched, and flies out for adventures in the outside world. However, he finds shelter at a premium, with bird houses filled to capacity, and endures the pursuit of a hungry cat and the dangers of a lightning storm, causing him to ultimately return gladly to his cage, and sing the praises of “Home Sweet Home.” Animation is a cut above the director’s previous efforts for Warner Brothers, though still attempting to find its own way, some elements of animation (such as the cat) bearing resemblances to earlier models such as used in “It’s Got Me Again”, and human animation of the old lady who owns the bird being highly rigid and lacking in either fluidity or realism.

The storm sequence is the highlight, featuring some interesting shots and effects. The first sign of rising winds is strong enough to turn the canary’s feathers inside out, revealing his denuded torso and tail. A lightning bolt crashes down directly on the tip of the tree on which he is perched, traveling down the trunk to the ground and erupting in an explosion, from which the tree is revealed as a spent matchstick. The cat climbs into one somehow-empty birdhouse, and repositions himself on the end of a tree limb, supported from his tail like a pole, awaiting the bird’s entrance into his open mouth inside. The wind, however, kicks up again, preventing the bird from reaching the doorway, and forcing him backwards into the trunk of another tree. The cat gives up the disguise, and engages in a fierce pursuit, which leads into and up another hollow tree trunk, and out onto a limb overhanging the roof of a cottage. The cat pursues the bird across the roof, but brakes just in time to avoid falling over the edge as he runs out of roof, preventing himself from falling by winding his tail around a lightning rod. The cat thinks he’s lost his prey, but suddenly brightens, seeing that the bird is in another losing battle with the wind, and being blown backwards. The bird grabs onto a rotating weather vane on the next roof, and is spun around and around as he clings to it. The cat, still maintaining a tail grip on the lightning rod, makes periodic grabs for the bird from the opposite roof, more or less like the reversal of trying to catch the brass ring from a merry-go-round. Of course, we all realize a lightning rod isn’t the greatest thing to be hanging onto in a rainstorm – and a bolt of electricity flashes through the sky, lighting up the cat in glowing red neon. Apparently remaining supercharged and in shock within, the cat falls from the roof, and leaps around in pain in a scene that closely resembles the retreat of the Big Bad Wolf in “Three Little Pigs”, disappearing down a country road. The storm isn’t through yet, and now strikes the weather vane on which the canary is perched. The bird barely has time to rise off of the metal pole to avoid the jolt, while the electric energy twists and transforms the shape of the metal crossbar to spell out in cursive lettering the word, “SCRAM”. The bird does just that, for our happy ending.

The storm sequence is the highlight, featuring some interesting shots and effects. The first sign of rising winds is strong enough to turn the canary’s feathers inside out, revealing his denuded torso and tail. A lightning bolt crashes down directly on the tip of the tree on which he is perched, traveling down the trunk to the ground and erupting in an explosion, from which the tree is revealed as a spent matchstick. The cat climbs into one somehow-empty birdhouse, and repositions himself on the end of a tree limb, supported from his tail like a pole, awaiting the bird’s entrance into his open mouth inside. The wind, however, kicks up again, preventing the bird from reaching the doorway, and forcing him backwards into the trunk of another tree. The cat gives up the disguise, and engages in a fierce pursuit, which leads into and up another hollow tree trunk, and out onto a limb overhanging the roof of a cottage. The cat pursues the bird across the roof, but brakes just in time to avoid falling over the edge as he runs out of roof, preventing himself from falling by winding his tail around a lightning rod. The cat thinks he’s lost his prey, but suddenly brightens, seeing that the bird is in another losing battle with the wind, and being blown backwards. The bird grabs onto a rotating weather vane on the next roof, and is spun around and around as he clings to it. The cat, still maintaining a tail grip on the lightning rod, makes periodic grabs for the bird from the opposite roof, more or less like the reversal of trying to catch the brass ring from a merry-go-round. Of course, we all realize a lightning rod isn’t the greatest thing to be hanging onto in a rainstorm – and a bolt of electricity flashes through the sky, lighting up the cat in glowing red neon. Apparently remaining supercharged and in shock within, the cat falls from the roof, and leaps around in pain in a scene that closely resembles the retreat of the Big Bad Wolf in “Three Little Pigs”, disappearing down a country road. The storm isn’t through yet, and now strikes the weather vane on which the canary is perched. The bird barely has time to rise off of the metal pole to avoid the jolt, while the electric energy twists and transforms the shape of the metal crossbar to spell out in cursive lettering the word, “SCRAM”. The bird does just that, for our happy ending.

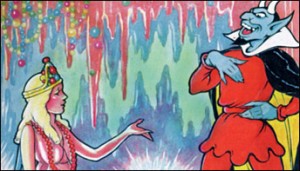

The Goddess of Spring (Disney/United Artists, Silly Symphony, 11/3/34 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.), is another of those rare early Disney one-shots that is a bit unsettling and considerably uncharacteristic for a Disney short. Loosely based on mythology, it is in essence the story of an abduction and ravishing. Satan appears from the underworld, amidst a self-generated storm of lightning strikes and harsh winds, atop an elevator platform of brimstone, to claim the lovely Goddess of Spring as his own, to be the new Queen of Hades. She resists, and is kidnapped by Satan, who carries her back to the elevator while his devil imps keep dwarfs and animals who serve the Goddess at bay. (It is notable that all dialogue of Satan and the Goddess is performed in the sing-song fashion of an operetta – a setting we usually associate with Paul Terry melodramas, making this film seem even more uncharacteristic of a Disney product.) The elevator lowers into the ground, while the imps jump into the hole, and the crack in the Earth’s surface heals itself, leaving the dwarfs no way in. They are left with only a chain of flowers that served as the goddess’s crown, and remain in a vigil around the spot where she disappeared, as action shifts to the kingdom below. Without the benefit of clergy (where would you find a member in hell?), Satan himself places a crown upon the goddess and declares her queen, in a cavernous throne room amidst the cheers of a legion of his imps. An elaborate musical spectacle, in a style only Disney could innovate, celebrates the forbidden union, in the number “Mighty Hades”.

The Goddess of Spring (Disney/United Artists, Silly Symphony, 11/3/34 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.), is another of those rare early Disney one-shots that is a bit unsettling and considerably uncharacteristic for a Disney short. Loosely based on mythology, it is in essence the story of an abduction and ravishing. Satan appears from the underworld, amidst a self-generated storm of lightning strikes and harsh winds, atop an elevator platform of brimstone, to claim the lovely Goddess of Spring as his own, to be the new Queen of Hades. She resists, and is kidnapped by Satan, who carries her back to the elevator while his devil imps keep dwarfs and animals who serve the Goddess at bay. (It is notable that all dialogue of Satan and the Goddess is performed in the sing-song fashion of an operetta – a setting we usually associate with Paul Terry melodramas, making this film seem even more uncharacteristic of a Disney product.) The elevator lowers into the ground, while the imps jump into the hole, and the crack in the Earth’s surface heals itself, leaving the dwarfs no way in. They are left with only a chain of flowers that served as the goddess’s crown, and remain in a vigil around the spot where she disappeared, as action shifts to the kingdom below. Without the benefit of clergy (where would you find a member in hell?), Satan himself places a crown upon the goddess and declares her queen, in a cavernous throne room amidst the cheers of a legion of his imps. An elaborate musical spectacle, in a style only Disney could innovate, celebrates the forbidden union, in the number “Mighty Hades”.

Back on the surface, the dwarfs shiver in icy cross-winds, and begin to be covered by a blanket of snow. The animals too suffer, a deer feeling the cold winds blowing visibly through its short fur coat, while birds, having no place warm to migrate, huddle together in the trees, becoming snow-covered lumps on the limbs above. There appears to be little for them to look to as hope, and the scene returns to the underworld. Satan is frustrated, as no matter what he does (including presenting the goddess with a humongous diamond from the bowels of the earth), he can’t get the goddess to smile, or break out of constant flow of tears. He offers to do anything if she’ll only smile, be a little bit gay. She begs to return to her world above, for if she does not, everything there will die. Satan is not a fool, and strikes a reasonably fair deal with her – return to the surface for six months each year, but swear to spend the remainder of the year below with him. To this she swears. She reappears on the elevator above – as a figure that again, uncharacteristic of Disney, does not seem like a heroine triumphant, but more as a sadder-but-wiser girl of experiences we don’t want to mention. Nevertheless, she waves her arms, and thaws out the world, setting up the cycle of seasons that the world knows today, to the reasonable happiness of the dwarfs and animals.

Back on the surface, the dwarfs shiver in icy cross-winds, and begin to be covered by a blanket of snow. The animals too suffer, a deer feeling the cold winds blowing visibly through its short fur coat, while birds, having no place warm to migrate, huddle together in the trees, becoming snow-covered lumps on the limbs above. There appears to be little for them to look to as hope, and the scene returns to the underworld. Satan is frustrated, as no matter what he does (including presenting the goddess with a humongous diamond from the bowels of the earth), he can’t get the goddess to smile, or break out of constant flow of tears. He offers to do anything if she’ll only smile, be a little bit gay. She begs to return to her world above, for if she does not, everything there will die. Satan is not a fool, and strikes a reasonably fair deal with her – return to the surface for six months each year, but swear to spend the remainder of the year below with him. To this she swears. She reappears on the elevator above – as a figure that again, uncharacteristic of Disney, does not seem like a heroine triumphant, but more as a sadder-but-wiser girl of experiences we don’t want to mention. Nevertheless, she waves her arms, and thaws out the world, setting up the cycle of seasons that the world knows today, to the reasonable happiness of the dwarfs and animals.

Despite the film’s strangeness, this fable was definitely influential upon the animation industry. It would no doubt ignite the inspiration for a competing explanation of the seasons, “To Spring”, from Harman and Ising at MGM a few seasons later. Its “Mighty Hades” number would inspire two copycat uses of color-changing flame by rival studios – a similar underworld celebration in Friz Freleng’s Sunday Go To Meeting Time for Warner Brothers, and another nearly-identical use of the technique in the setting of a tribal dance in the Columbia Color Rhapsody, Swing, Monkey, Swing.

Krazy’s Waterloo (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Krazy Kat, 11/16/34 – Ben Harrison/Manny Gould, dir.) – It is a bit uncertain in the setup of this cartoon if Krazy is merely a lunatic who fancies himself to be Napoleon, or in fact is Napoleon, as, in the opening shots, he has all the uniforms and palatial trappings of the emperor, but is seen staring at a painting on the wall, depicting a human Napoleon, while he himself is of course a cat. Nevertheless Krazy is in charge, but instead of fighting the English at Waterloo, chooses to mount one of his predecessor’s most unsuccessful military campaigns in duplicate – an invasion of Russia. This of course leads not only to a battle with the Bolsheviks, but enduring of the fierce Russian winter. As Krazy’s small regiment of animal soldiers approaches the Russian border, all Krazy can see through his binoculars is snow, covering two lumps which turn out to be a sentry station (revealed from the force of a bearded sentry’s snores within), and a sign marking the borderline, which is also revealed through a second snore. Krazy continues his march, as ice forms upon his shoulders and marching drum, and his troops and horse become buried waist-deep. The sentry sees the trails being cut through the snow by the advancing troops, and grabs a bugle to sound an alarm. His call is followed by a second bugle call from another smaller sentry hiddden in his beard, then answered by an even smaller sentry hidden in the next beard, whose notes play the Jewish strains of “Lesghinka”.

Krazy’s Waterloo (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Krazy Kat, 11/16/34 – Ben Harrison/Manny Gould, dir.) – It is a bit uncertain in the setup of this cartoon if Krazy is merely a lunatic who fancies himself to be Napoleon, or in fact is Napoleon, as, in the opening shots, he has all the uniforms and palatial trappings of the emperor, but is seen staring at a painting on the wall, depicting a human Napoleon, while he himself is of course a cat. Nevertheless Krazy is in charge, but instead of fighting the English at Waterloo, chooses to mount one of his predecessor’s most unsuccessful military campaigns in duplicate – an invasion of Russia. This of course leads not only to a battle with the Bolsheviks, but enduring of the fierce Russian winter. As Krazy’s small regiment of animal soldiers approaches the Russian border, all Krazy can see through his binoculars is snow, covering two lumps which turn out to be a sentry station (revealed from the force of a bearded sentry’s snores within), and a sign marking the borderline, which is also revealed through a second snore. Krazy continues his march, as ice forms upon his shoulders and marching drum, and his troops and horse become buried waist-deep. The sentry sees the trails being cut through the snow by the advancing troops, and grabs a bugle to sound an alarm. His call is followed by a second bugle call from another smaller sentry hiddden in his beard, then answered by an even smaller sentry hidden in the next beard, whose notes play the Jewish strains of “Lesghinka”.

In a snow-covered trenchline, three bearded Bolshevik soldiers begin systematically tossing lit cartoon-style black bombs at Krazy’s approaching troops. The bombs begin to fall around Krazy, making holes in the snow, followed by larger craters as they explode. One bomb pursues Krazy in the air. The little emperor charges in reverse, running his horse right over the heads of his own soldiers deep within the snow. Krazy’s horse collides with a tree trunk, just as the bomb explodes. Krazy thinks he’s still galloping, but finds himself in his saddle, seated upon a bobbing tree limb high above the ground, while higher still sits his horse, licking a wounded and smoldering rear-end denuded of hair from the explosion. “Bring up the artillery”, commands Krazy. He discovers his cannon blanketed in a coating of snow, shuddering with the chills, its barrel enduring a sneezing fit. Krazy produces a medicine bottle, pouring into the weapon’s barrel a pill large enough to serve as a cannonball. But the weapon’s sneeze spits the medicine out, fracturing it into useless shards. Krazy decides to turn this malady into an advantage, loading the cannon with real cannonballs, then waiting for the inevitable sneeze. The idea works, as the weapon shoots out ammunition like a Gatling gun. Another heavily-bearded soldier in the trenches laughs at the canon fire, nimbly dodging shot after shot, but finally takes a blow straight in the face, disintegrating his beard off. He angrily seizes a strip of icicles off a tree limb, and repeats a gag from Scrappy’s “The Wolf at the Door”, feedng them as ammo into the workings of a machine gun for a reverse rapid-fire attack.

Krazy ducks into trenches of his own, and neutralizes the attack by positioning a campfire under the line of icicles, melting them as they pass. He issues orders to his troops to go “Over the top”. His soldiers obey, but are hit by a new barrage from the enemy – accomplished by loading boxing gloves into cannons, resulting in a one-two knockout punch to each of Krazy’s soldiers. One member of Krazy’s staff remains – a fat general pig, who remains seated comfortably in the trench, playing mumbly-peg with his sword. Krazy orders him into the fray, but the pig protests. “I’m a general. Generals don’t fight.” Krazy engages in an instant demotion, puncturing the side of the inflated pig with a penknife, deflating him to a standard short soldier, who instantly waves a salute, and proceeds up the trench’s ladder. He gets no farther than the top rung, as he is socked back into the trench by an upper-cut from the cannoneer Bolshevik, who is now carrying another pair of black bombs to get at Krazy. A camera shot from outer space shows Krazy and the Bolshevik running around and around over the rotating globe, as the Bolshevik hurls the bombs, blasting Krazy into the sky. Krazy finally comes to rest in a small motorboat at a dock where snow is no longer observed, and is briefly joined by his Josephine (Kitty) and several of his countrymen, who bid him goodbye from the dock, as the motorboat turns to carry the little emperor off to a small island seen in the background, the boat’s rear life-preserver announcing the source of the ship – St. Heleaa Lines.

Krazy ducks into trenches of his own, and neutralizes the attack by positioning a campfire under the line of icicles, melting them as they pass. He issues orders to his troops to go “Over the top”. His soldiers obey, but are hit by a new barrage from the enemy – accomplished by loading boxing gloves into cannons, resulting in a one-two knockout punch to each of Krazy’s soldiers. One member of Krazy’s staff remains – a fat general pig, who remains seated comfortably in the trench, playing mumbly-peg with his sword. Krazy orders him into the fray, but the pig protests. “I’m a general. Generals don’t fight.” Krazy engages in an instant demotion, puncturing the side of the inflated pig with a penknife, deflating him to a standard short soldier, who instantly waves a salute, and proceeds up the trench’s ladder. He gets no farther than the top rung, as he is socked back into the trench by an upper-cut from the cannoneer Bolshevik, who is now carrying another pair of black bombs to get at Krazy. A camera shot from outer space shows Krazy and the Bolshevik running around and around over the rotating globe, as the Bolshevik hurls the bombs, blasting Krazy into the sky. Krazy finally comes to rest in a small motorboat at a dock where snow is no longer observed, and is briefly joined by his Josephine (Kitty) and several of his countrymen, who bid him goodbye from the dock, as the motorboat turns to carry the little emperor off to a small island seen in the background, the boat’s rear life-preserver announcing the source of the ship – St. Heleaa Lines.

South Pole or Bust (Terrytoons/Educational, 12/14/34) – Another pair of daring aviators (this time, a proto-Puddy pup and mouse) leave New York on a flight to the South Pole. Just short of its destination, the plane begins to encounter some rough weather. A rainstorm prompts the pilots to extend a huge umbrella out the roof hatch, only to have the handle blasted apart by a bolt of lightning. Now over Antarctica, the plane bores headfirst into the side of an iceberg – which holds within a set of high-rise apartments, with a flock of polar bears aroused and peering out windows at the strange intruders. The plane is covered in snow, and as the mouse shovels, he discovers they’ve picked up a passenger – a walrus, fast asleep in a four-post bed. The mouse slides the bed off the plane’s tail (in an interesting use of snow effects, as the snow drifts dimensionally upwards, as if the camera is passing the snowflakes at higher speed than their fall), leaving the walrus to crash through the ice surface below into cold water. (Wait a minute.

South Pole or Bust (Terrytoons/Educational, 12/14/34) – Another pair of daring aviators (this time, a proto-Puddy pup and mouse) leave New York on a flight to the South Pole. Just short of its destination, the plane begins to encounter some rough weather. A rainstorm prompts the pilots to extend a huge umbrella out the roof hatch, only to have the handle blasted apart by a bolt of lightning. Now over Antarctica, the plane bores headfirst into the side of an iceberg – which holds within a set of high-rise apartments, with a flock of polar bears aroused and peering out windows at the strange intruders. The plane is covered in snow, and as the mouse shovels, he discovers they’ve picked up a passenger – a walrus, fast asleep in a four-post bed. The mouse slides the bed off the plane’s tail (in an interesting use of snow effects, as the snow drifts dimensionally upwards, as if the camera is passing the snowflakes at higher speed than their fall), leaving the walrus to crash through the ice surface below into cold water. (Wait a minute.

Antarctica is a land continent, not a polar ice cap, so why is there water?) The infuriated walrus removes his tusks, and fastens them to his feet as skis to follow the plane. He then picks up a dog sled from a nearby igloo, with a typically mismatched team including a puppy in the middle whose feet don’t even reach the ground. Amidst the polar lights, the plane comes in for a landing to the cheers of the local wildlife. A quartet of penguins, carrying a key to the city and a sign reading ‘South Pole Rotarians”, bids formal greeting through a spokesman bird who sounds like Jimmy Durante – “Welcome to the South Pole and all dat kinda stuff!” But the crowd quickly disperses, as the walrus looms behind the two pilots. He gives chase, and the boys climb up the South Pole itself in attempt to escape the beast’s reach. The walrus tries to shake them down, and in a creative shot, a view of the earth is seen from outer space, with the whole planet trembling from the violent shaking of the walrus seen upside down at the pole below. For the first time, the plane sprouts a face, and, aroused by the shaking, takes off to the rescue. It drops a rope ladder to the boys, and the pup and mouse hang on both to the ladder and the pole, allowing the plane to tow both them and the pole away into the sky, with the walrus slipping off and left to futilely pursue on foot, to the horizon for the iris out.

Jack Frost (Ub Iwerks, ComiColor, 12/24/34) – One of Iwerks’ most enduring and appealing color cartoons. A young bear cub greets the opportunity to experience his first winter, as the elf-like spirit, Jack Frost, paints tree leaves and pumpkins in various shades of orange and brown from a painter’s palette, signaling a nip in the air and the change of the seasons. While Frost cautions the forest folk that Old Man Winter will be arriving soon, and to get their food and nuts stored away, the bear cub laughs with bravado, realizing nature has provided him with a thick fur coat, and gesturing like a sparring boxer to bring on any challenge Winter may offer. His Mom has other ideas, and hustles him inside their tree-trunk home to bed for a long Winter’s hibernation. But while Mom and Pop saw wood (literally, in a dream cloud over their beds), Junior cub decides he is too much of a man to be pushed around this way, and packs his favorite belongings in a bindle stick (taking care to exclude a toothbrush) to run away and see the world. Following Jack Frost, who happens by to paint icicle designs on the tree’s window pane, the cub slips out, and experiences some musical entertainment from some pumpkins transformed into Jack-o-lanterns by Frost’s brush, and a scat-singing scarecrow backed by singing trees, who performs a song and dance in the manner of Cab Calloway and the Mills Brothers.

Jack Frost (Ub Iwerks, ComiColor, 12/24/34) – One of Iwerks’ most enduring and appealing color cartoons. A young bear cub greets the opportunity to experience his first winter, as the elf-like spirit, Jack Frost, paints tree leaves and pumpkins in various shades of orange and brown from a painter’s palette, signaling a nip in the air and the change of the seasons. While Frost cautions the forest folk that Old Man Winter will be arriving soon, and to get their food and nuts stored away, the bear cub laughs with bravado, realizing nature has provided him with a thick fur coat, and gesturing like a sparring boxer to bring on any challenge Winter may offer. His Mom has other ideas, and hustles him inside their tree-trunk home to bed for a long Winter’s hibernation. But while Mom and Pop saw wood (literally, in a dream cloud over their beds), Junior cub decides he is too much of a man to be pushed around this way, and packs his favorite belongings in a bindle stick (taking care to exclude a toothbrush) to run away and see the world. Following Jack Frost, who happens by to paint icicle designs on the tree’s window pane, the cub slips out, and experiences some musical entertainment from some pumpkins transformed into Jack-o-lanterns by Frost’s brush, and a scat-singing scarecrow backed by singing trees, who performs a song and dance in the manner of Cab Calloway and the Mills Brothers.

Suddenly the entire mood changes, as the skies darken into deepened shades of blue, and a stiff wind (which turns the bear’s nightshirt inside out) drives waves of snow and sleet across the countryside, freezing the scarecrow in place, and covering him with a thick blanket of snow, until he resembles a reasonable facsimile of the yet-to-be Frosty the Snowman. In a spiral of wind, the figure of Old Man Winter materializes – an ice-blue, stoop-shouldered, oversized imp with long white beard and hair made of icicles, a long pointed nose and menacing grin. The sight is enough to send the formerly brave cub a-running, and Winter pursues on foot, playfully blowing up a snowball to surround the bear, rolling him into the side of a tree trunk. Looking for any refuge, the bear pounds on the door of any tree that’s handy. But occupancy rates are at capacity, and at each door, he receives a sock or a boot from those already inside. Only one door bids him entrance – its sole, lonely occupant being a skunk, who could use the company. This is too much even for a desperate bear, and the cub quickly turns down the invite, holding his nose so as not to inhale the visible aromas rising from the door. Winter catches up again, and the only place left to duck for the bear is inside a fallen log. “So you would run away from home”, growls Winter, and a few magical waves from his fingers produce a set of icy bars, covering the entrance to the log, sealing the cub inside for the season’s duration. Satisfied at his michief, Winter disappears in a whirlwind the way he came in. As the bear cries in despair, who should descend from the sky but Frost. “I told you not to leave your home”, he reminds the cub. The cub states that he is sorry, and wants nothing more than to return to his nice warm bed.

Suddenly the entire mood changes, as the skies darken into deepened shades of blue, and a stiff wind (which turns the bear’s nightshirt inside out) drives waves of snow and sleet across the countryside, freezing the scarecrow in place, and covering him with a thick blanket of snow, until he resembles a reasonable facsimile of the yet-to-be Frosty the Snowman. In a spiral of wind, the figure of Old Man Winter materializes – an ice-blue, stoop-shouldered, oversized imp with long white beard and hair made of icicles, a long pointed nose and menacing grin. The sight is enough to send the formerly brave cub a-running, and Winter pursues on foot, playfully blowing up a snowball to surround the bear, rolling him into the side of a tree trunk. Looking for any refuge, the bear pounds on the door of any tree that’s handy. But occupancy rates are at capacity, and at each door, he receives a sock or a boot from those already inside. Only one door bids him entrance – its sole, lonely occupant being a skunk, who could use the company. This is too much even for a desperate bear, and the cub quickly turns down the invite, holding his nose so as not to inhale the visible aromas rising from the door. Winter catches up again, and the only place left to duck for the bear is inside a fallen log. “So you would run away from home”, growls Winter, and a few magical waves from his fingers produce a set of icy bars, covering the entrance to the log, sealing the cub inside for the season’s duration. Satisfied at his michief, Winter disappears in a whirlwind the way he came in. As the bear cries in despair, who should descend from the sky but Frost. “I told you not to leave your home”, he reminds the cub. The cub states that he is sorry, and wants nothing more than to return to his nice warm bed.

Realizing the cub has learned a lesson, Frost lends a helping paintbrush, dabbing each of the ice bars with a few drops of his magical paint, which spiral down each of the bars, transforming them into tasty peppermint sticks. The bear eagerly licks at the bars (without even getting his tongue stuck to them), and soon has dissolved a gap between then large enough to slip through. Jack seats the cub and himself upon the artist’s palette, and shoves off, using his paintbrush like an oar. The palette soars in an arc into the air, producing a rainbow (or at least as much of one as two-strip Cinecolor will permit), then lands just outside the bear’s bedroom window, still left ajar. (Lucky there was a fire burning in the fireplace inside, or the place would be freezing by now.) Frost sets the bear comfortably in his bed, pulling the covers over him, then pulls back outside and closes the window, leaving the bear for a comfortable winter. Before leaving, Jack ends the cartoon, by paining in icicles on the window “Finis.” A memorable and charming tale, accompanied by an excellent original Carl Stalling score, easily places this as one of Iwerks’ top-tier productions.

Realizing the cub has learned a lesson, Frost lends a helping paintbrush, dabbing each of the ice bars with a few drops of his magical paint, which spiral down each of the bars, transforming them into tasty peppermint sticks. The bear eagerly licks at the bars (without even getting his tongue stuck to them), and soon has dissolved a gap between then large enough to slip through. Jack seats the cub and himself upon the artist’s palette, and shoves off, using his paintbrush like an oar. The palette soars in an arc into the air, producing a rainbow (or at least as much of one as two-strip Cinecolor will permit), then lands just outside the bear’s bedroom window, still left ajar. (Lucky there was a fire burning in the fireplace inside, or the place would be freezing by now.) Frost sets the bear comfortably in his bed, pulling the covers over him, then pulls back outside and closes the window, leaving the bear for a comfortable winter. Before leaving, Jack ends the cartoon, by paining in icicles on the window “Finis.” A memorable and charming tale, accompanied by an excellent original Carl Stalling score, easily places this as one of Iwerks’ top-tier productions.

Buddy the Detective (Warner, Looney Tunes (Buddy), 10/17/34 – Jack King, dir.) – Weather is played for mostly atmospherics here, setting the stage for a night of spooky and mysterious goings-on. A mad musician has escaped from an undisclosed asylum, and is holed-up in an old abandoned house suitable for haunting, amidst the howling winds and driving rain of a thunderstorm. He sits inside at an old piano, hammering out the bombastic theme notes of Rachmaninoff’s Prelude, Op. 3, No. 2 in C Sharp Minor. He is dissatisfied with his own results, but even more upset when the branches of a leafless tree are driven inside the window by the forceful winds, and peck out a jazzy theme on the keyboard with the bouncing of their limbs. “Bah”, he shouts, declaring that he seeks inspiration. Demonstrating Svengali-like finger-waves and hypnotic powers, he hypnotizes a frog to perform a “masterpiece” for him. The frog merely performs hops and acrobatic tumbles upon the keys, his melodies sounding incredibly juvenile. The musician aims his hypnosis at a portrait of Napoleon on the wall (two appearances for the emperor in the same season?), and commands him to play. From beneath his coat, the emperor produces a fiddle and bow, but plays too forcefully, sawing the violin in two. With no one else to turn to, the musician selects a listing at random from a phone book, and calls up Cookie, summoning her hypnotically via long distance to come to him. He is even able to manipulate Cookie’s front door from long-distance, it flying open on cue to allow Cookie to exit in a trance into the storm. Towser the dog, however, has seen the whole incident, and, grabbing up a copy of the newspaper announcing the musician’s disappearance, runs with it to the office of Detective Buddy. Buddy quickly gets the message, and dons Sherlock Holmes hat, coat, and magnifying glass to accept the case.

Buddy the Detective (Warner, Looney Tunes (Buddy), 10/17/34 – Jack King, dir.) – Weather is played for mostly atmospherics here, setting the stage for a night of spooky and mysterious goings-on. A mad musician has escaped from an undisclosed asylum, and is holed-up in an old abandoned house suitable for haunting, amidst the howling winds and driving rain of a thunderstorm. He sits inside at an old piano, hammering out the bombastic theme notes of Rachmaninoff’s Prelude, Op. 3, No. 2 in C Sharp Minor. He is dissatisfied with his own results, but even more upset when the branches of a leafless tree are driven inside the window by the forceful winds, and peck out a jazzy theme on the keyboard with the bouncing of their limbs. “Bah”, he shouts, declaring that he seeks inspiration. Demonstrating Svengali-like finger-waves and hypnotic powers, he hypnotizes a frog to perform a “masterpiece” for him. The frog merely performs hops and acrobatic tumbles upon the keys, his melodies sounding incredibly juvenile. The musician aims his hypnosis at a portrait of Napoleon on the wall (two appearances for the emperor in the same season?), and commands him to play. From beneath his coat, the emperor produces a fiddle and bow, but plays too forcefully, sawing the violin in two. With no one else to turn to, the musician selects a listing at random from a phone book, and calls up Cookie, summoning her hypnotically via long distance to come to him. He is even able to manipulate Cookie’s front door from long-distance, it flying open on cue to allow Cookie to exit in a trance into the storm. Towser the dog, however, has seen the whole incident, and, grabbing up a copy of the newspaper announcing the musician’s disappearance, runs with it to the office of Detective Buddy. Buddy quickly gets the message, and dons Sherlock Holmes hat, coat, and magnifying glass to accept the case.

By now, Cookie is seated at the villain’s piano, repeating the strains of the Rachmaninoff music under hypnotic control. The musician’s influence, however, is not strong enough to prevent her from interjecting a few bars of ragtime between the classical notes, prompting another shout of “Bah” from the musician. Buddy arrives through the storm at the front door, finding it locked. Creatively, he produces a flashlight, shining its light beam through his magnifying glass, artificially producing the effect of a blow torch with the beam of light, to cut a hole through the door. As he proceeds into the house, a spider lands upon the lens of Buddy’s flashlight. Now, wherever Buddy points the light, the spider’s silhouette appears, frightening Buddy and Towser. For no reason other than to fill allotted time, Buddy and Towser chase, then are chased themselves, by a pair of skeletons who reside at the abode. Then Buddy finally hears Cookie’s screams from a room on the second floor. He tries the door, but it remains locked, while the musician sneers at him. Buddy provides his own entrance, lifting the doorway of another room right off the wall as if it were a mirror frame, then repositioning it on the wall of the room where Cookie remains prisoner. The door opens easily, admitting Buddy through a newly-created hole in the wall behind it. Buddy engages in brief battle with the musician, finally grabbing his legs and twirling him around, tossing him at one of the walls of the room. The musician lies on his chest, momentarily unconscious, with the piano stool atop his back. Buddy spins the wheeled legs of the piano stool, which extends the height of the stool in a corkscrew spiral, until its feet reach all the way to the ceiling, pinning the musician down between stool and floor. Cookie awakens from her spell, and embraces Buddy. She then begins to play her own kind of music on the piano – more raggy jazz, which leaves the reviving villain tearing his hair out, and yelling for help in the open mouth style of Joe E. Brown, with the camera lens being lost within his throat for a black out.

By now, Cookie is seated at the villain’s piano, repeating the strains of the Rachmaninoff music under hypnotic control. The musician’s influence, however, is not strong enough to prevent her from interjecting a few bars of ragtime between the classical notes, prompting another shout of “Bah” from the musician. Buddy arrives through the storm at the front door, finding it locked. Creatively, he produces a flashlight, shining its light beam through his magnifying glass, artificially producing the effect of a blow torch with the beam of light, to cut a hole through the door. As he proceeds into the house, a spider lands upon the lens of Buddy’s flashlight. Now, wherever Buddy points the light, the spider’s silhouette appears, frightening Buddy and Towser. For no reason other than to fill allotted time, Buddy and Towser chase, then are chased themselves, by a pair of skeletons who reside at the abode. Then Buddy finally hears Cookie’s screams from a room on the second floor. He tries the door, but it remains locked, while the musician sneers at him. Buddy provides his own entrance, lifting the doorway of another room right off the wall as if it were a mirror frame, then repositioning it on the wall of the room where Cookie remains prisoner. The door opens easily, admitting Buddy through a newly-created hole in the wall behind it. Buddy engages in brief battle with the musician, finally grabbing his legs and twirling him around, tossing him at one of the walls of the room. The musician lies on his chest, momentarily unconscious, with the piano stool atop his back. Buddy spins the wheeled legs of the piano stool, which extends the height of the stool in a corkscrew spiral, until its feet reach all the way to the ceiling, pinning the musician down between stool and floor. Cookie awakens from her spell, and embraces Buddy. She then begins to play her own kind of music on the piano – more raggy jazz, which leaves the reviving villain tearing his hair out, and yelling for help in the open mouth style of Joe E. Brown, with the camera lens being lost within his throat for a black out.

Not much in the way of violent storm action in The First Snow (Terrytoons/Educational, 1/11/35). Puppies awaken to find the forest community being blanketed with gentle snow. Looking out the window of the old shoe in which they live (obviously a hand-me-down from an “old woman”), they even observe a non-migratory bird using their window sill as an ice skating rink. Mostly, the film is an excuse to show various “Aesop”-style animals cavorting in winter sports. A toboggan-run sequence does what Terry does best – retread old ideas. A perspective shot on a downhill run would see many reuses in both black and white and color, including in Eddie Donnelly Switzerland cartoons of the late 30’s and early 40’s, and as late as Connie Rasinski’s “The Clockmaker’s Dog” in 1956. A further gag with one sled after another knocking each other into a jump over a chasm dates at least as far back as a similar situation on a roller-coaster with a dead-end track in “Popcorn” (1930). A new gag has a strolling chicken experience several near misses by the sleds at the foot of the hills, then endure a direct hit, knocking all of its feathers off, as well as ejecting from it four eggs, which are also hit by the next of the sleds, cracking open the shells to hatch the chicken’s new brood. A snowman is built, and appears briefly to come to life. But no, it is not Ted Eshbaugh’s monster – merely more of the puppies hiding inside it, standing on a pair of crossed wooden poles to support them in the manner of a scarecrow framework. Ice skating follows (with one detailed shot of criss-crossing skaters in cycle, that appears to depict an entirely different cast of animals than the main cartoon, raising strong suspicion it is also a reused shot from the Aesop days. A portly female pig experiences a collision from a bathtub rigged with sails, and is knocked from the skating ice into the open river, headed for a waterfall amidst a constant flow of ice floes. The pups man a canoe, and sail out to the rescue. No particularly notable gags in the sequence, but some decently-dramatic animation of the waterfall, and of ice floes in many lines of perspective. The pig is towed back atop the skating ice, but has caught a cold, and sneezes so hard, she breaks through the ice surface into the water again, dunking most of the cast in the hole with her.

Next time: a whirlwind of excitement.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Thank you for this nice group of 1930s cartoons as we approach to color technicolor. Yes, I very much remember “the discontented canary“. I remember the lightning bolt sending the cat screaming to the ground and lighting him up like a rainbow! Of course I never saw it in color, because it was only shown on television as a grainy black and white, but it was still very memorable. The Looney Tunes entry here was very memorable for its atmosphere! I wonder what this cartoon would look fully restored, so we get a better idea of its quality.“Jack Frost“ has a wonderful score.

It’s admittedly impossible to tell from the French translation of the cartoon embedded here, but I’m sure the flashy musical number in the middle of “The Goddess of Spring” was called “Hi De Hades”, not “Mighty Hades”. This is among the few early cartoons to equate classical music with the forces of good, and jazz with those of evil. More commonly, as in “Music Land” and “Buzzy Boop at the Concert”, classical music was presented as stodgy and boring, and jazz as liberating and fun. Nowadays, of course, any character in a movie who enjoys classical music is bound to be an abusive parent at best and a serial killer at worst.

As I recall the myth, the goddess Persephone was abducted by Hades and taken by him into the underworld, and it was the mourning of her mother, the fertility goddess Demeter, that created winter. Therefore Zeus confronted Hades and demanded Persephone’s release. (Since Zeus, Demeter and Hades were all children of the Titans Rhea and Kronos, that means Persephone was Hades’s niece on both sides.) However, Hades had already given Persephone some pomegranate seeds to eat, and since she had tasted the food of the underworld she was unable to leave it permanently. That was the reason for her having to spend half of each year there in perpetuity, or at least that’s how I remember it. It’s been a long time since I had to read Hesiod’s Theogony in college.

I had never seen “Krazy’s Waterloo” before and really enjoyed it. I kept expecting to hear the musical score break into the 1812 Overture, which deals with the same subject matter as the cartoon, but it didn’t — although both Tchaikovsky and Joe De Nat incorporated some of the same Russian folk songs, as well as La Marseillaise.

I was very amused to see that the first name listed on the page from the phone directory in “Buddy the Detective” was for “CLAMPETT, R.”

That bit with the chicken in “The First Snow” was not “a new gag”; it had previously been used in “Popcorn” (1931), only with tour buses instead of sleds.

Can’t wait to read what you’ll have to say about Bill Hanna’s directorial debut. “Time for spring, I say!”

Some interesting musical cues in “Shiver Me Timbers”: As the ghost ship sets sail, we hear a few bars of the Overture to “The Flying Dutchman.” And in the scene with the skeletons, it’s “Swing You Sinners.”

Persephone is not Les Clark’s best work, but he’s one of my favorites.

“The Goddess of Spring” is an impressive achievement until you realize that a mere three years later those same artists were finishing “Snow White” and “The Old Mill,” which would make the earlier cartoon look clumsy and clunky.

“Shiver Me Timbers” is vintage Popeye, combining the best of Segar and Fleischer. Not surprisingly, the most successful Popeye cartoons are those relatively few where the sailor is actually at sea.

“Jack Frost,” like nearly all Ub Iwerks’ ComiColor cartoons, suffers from a lack of imagination and inspiration.

“Buddy the Detective” is one of two Buddy cartoons I actually kind of like (the other one is “Buddy’s Adventures”).

I haven’t seen the Krazy Kat or the TerryToon, and I don’t think I’m missing much.