Some extended-length works today. Our shortest is a double-length Gumby episode from the early days of the series. Our longest is a three-chapter Manga from Japan. In-between, we have several half-hour and hour-long stories, including many well-remembered prime time specials. All continue to provide stormy moments consistent with our subject topic. So put on your snowshoes and climbing spikes, as we embark upon this long, long trail.

Rain Spirits (Gumby, 10/5/56 – Art Clokey, dir.) – a Gumby installment played mostly straight, largely dependent upon atmospheric miniature sets and colorful character designs for its visual appeal. Gumby and Pokey begin the day in their toyland home, playing in a miniature swimming pool complete with diving board. Gumby makes a flying somersault, but “dives too deep”, performing his usual feat of traveling through solid objects and overshooting the pool bottom, coming up outside the pool from under the ground. He tries a dive again, intending to flatten out more, but to Pokey’s surprise, as Gumby comes down, there are two splashes. In the pool with them, they find a small Indian boy, who is lost and has fallen out of a volume on the bookshelf. “I must have taken wrong canyon”, he explains. He further explains that he was on his way to find the home of the Kochina rain spirits, as his homeland is in the grip of a drought, its crops drying up, and his people on the verge of starvation. Gumby is eager to help the boy locate his book (“I couldn’t read title” the boy confesses), but Pokey follows reluctantly, much wishing he could simply continue to enjoy the pool water. The boys survey the book shelf for a likely volume, and Pokey experiences his only moment of pleasure, as his head disappears into the spine of a book about a candy store, and he briefly eats his fill. Gumby locates the right volume, on Hopi Indians. “That my home”, says the boy. They enter inside the walls of a narrow canton within, and are soon scaling a steep cliff face, to a cave entrance high above identified by a small sign reading “Rain Spirits”. Inside, the cave floor and ceiling are dotted by stalactites and stalagmites, one of which Pokey samples, thinking it is an ice cream cone. Hearing rushing water at the other end of a thin narrow passageway, the boys squeeze through, Gumby and Pokey emerging as flat as pancakes, and rolling up like windowshades to regain their normal dimensions. A huge waterfall of an underground river is observed, and the sounds of native chanting tell them that the spirits cannot be far. They encounter the spirits (depicted with faces resembling totem masks), dancing a ceremonial dance in a deeper cave on a level below them. Pokey and the Indian boy are afraid, but Pokey accidentally reveals their presence by knocking down a stalactite. The spirits look up, but without surprise. “We know you have come for help.” Hearing the boy’s request for rain for his people, the spirits test his worthiness with one simple inquiry: “Are you obedient to your father and mother?” (Just think – send one disobedient child as your emissary, and an entire population starves!). The spirits promise rain, in return for the boy’s promise to leave the first ear of corn for their messenger. Then, the spirits suddenly disappear. Pokey leads the way out – as fast as possible.

Rain Spirits (Gumby, 10/5/56 – Art Clokey, dir.) – a Gumby installment played mostly straight, largely dependent upon atmospheric miniature sets and colorful character designs for its visual appeal. Gumby and Pokey begin the day in their toyland home, playing in a miniature swimming pool complete with diving board. Gumby makes a flying somersault, but “dives too deep”, performing his usual feat of traveling through solid objects and overshooting the pool bottom, coming up outside the pool from under the ground. He tries a dive again, intending to flatten out more, but to Pokey’s surprise, as Gumby comes down, there are two splashes. In the pool with them, they find a small Indian boy, who is lost and has fallen out of a volume on the bookshelf. “I must have taken wrong canyon”, he explains. He further explains that he was on his way to find the home of the Kochina rain spirits, as his homeland is in the grip of a drought, its crops drying up, and his people on the verge of starvation. Gumby is eager to help the boy locate his book (“I couldn’t read title” the boy confesses), but Pokey follows reluctantly, much wishing he could simply continue to enjoy the pool water. The boys survey the book shelf for a likely volume, and Pokey experiences his only moment of pleasure, as his head disappears into the spine of a book about a candy store, and he briefly eats his fill. Gumby locates the right volume, on Hopi Indians. “That my home”, says the boy. They enter inside the walls of a narrow canton within, and are soon scaling a steep cliff face, to a cave entrance high above identified by a small sign reading “Rain Spirits”. Inside, the cave floor and ceiling are dotted by stalactites and stalagmites, one of which Pokey samples, thinking it is an ice cream cone. Hearing rushing water at the other end of a thin narrow passageway, the boys squeeze through, Gumby and Pokey emerging as flat as pancakes, and rolling up like windowshades to regain their normal dimensions. A huge waterfall of an underground river is observed, and the sounds of native chanting tell them that the spirits cannot be far. They encounter the spirits (depicted with faces resembling totem masks), dancing a ceremonial dance in a deeper cave on a level below them. Pokey and the Indian boy are afraid, but Pokey accidentally reveals their presence by knocking down a stalactite. The spirits look up, but without surprise. “We know you have come for help.” Hearing the boy’s request for rain for his people, the spirits test his worthiness with one simple inquiry: “Are you obedient to your father and mother?” (Just think – send one disobedient child as your emissary, and an entire population starves!). The spirits promise rain, in return for the boy’s promise to leave the first ear of corn for their messenger. Then, the spirits suddenly disappear. Pokey leads the way out – as fast as possible.

The boys visit the Indian boy’s home in the Southwestern desert. Impatient Pokey sees no sign of rain clouds, and casts doubt upon the spirits’ promise. A small goat (the boy’s pet), immediately comes along and butts Pokey from the rear, into a wall – then speaks in a bleating voice, informing the boy that he was sent by the Kochinas to punish the horse for doubting them. The sky suddenly darkens, and Pokey thinks the impact with the wall is making him see things, as the heads of the spirits, now 100 times life size, parade across the blackened sky in dance. A cloud quickly forms as they pass, and a steady rain provides life-saving moisture to the Indian land. A corn-goddess Kochina also appears, imparting blessings to the withered corn stalks, quadrupling them in size to full bloom in a matter of seconds. “Now my people not starve”, says the boy. Not forgetting his own promise, the boy places the first ear of corn upon the top of the highest nearby mountain peak. Out of the cloud appears a thunderbird, who swoops down to retrieve the corn, flies back into the cloud, and disappears. Their job done, the boy offers Gumby and Pokey the hospitality of his own now-filled swimming hole, set among the rocks of another nearby canyon. Pokey as usual lags behind, stating he prefers their own pool – but is butted into the water by the boy’s goat. This deed does not go unpunished, as a whipper Kochina appears, to mete out a spanking to the goat for his rude behavior. The goat, however, has the last laugh, as the animated end titles depict the goat again butting Pokey off a ledge, causing Pokey’s body to fragment in mid-air into orange letters reading “The End.”

The boys visit the Indian boy’s home in the Southwestern desert. Impatient Pokey sees no sign of rain clouds, and casts doubt upon the spirits’ promise. A small goat (the boy’s pet), immediately comes along and butts Pokey from the rear, into a wall – then speaks in a bleating voice, informing the boy that he was sent by the Kochinas to punish the horse for doubting them. The sky suddenly darkens, and Pokey thinks the impact with the wall is making him see things, as the heads of the spirits, now 100 times life size, parade across the blackened sky in dance. A cloud quickly forms as they pass, and a steady rain provides life-saving moisture to the Indian land. A corn-goddess Kochina also appears, imparting blessings to the withered corn stalks, quadrupling them in size to full bloom in a matter of seconds. “Now my people not starve”, says the boy. Not forgetting his own promise, the boy places the first ear of corn upon the top of the highest nearby mountain peak. Out of the cloud appears a thunderbird, who swoops down to retrieve the corn, flies back into the cloud, and disappears. Their job done, the boy offers Gumby and Pokey the hospitality of his own now-filled swimming hole, set among the rocks of another nearby canyon. Pokey as usual lags behind, stating he prefers their own pool – but is butted into the water by the boy’s goat. This deed does not go unpunished, as a whipper Kochina appears, to mete out a spanking to the goat for his rude behavior. The goat, however, has the last laugh, as the animated end titles depict the goat again butting Pokey off a ledge, causing Pokey’s body to fragment in mid-air into orange letters reading “The End.”

The Manga-driven animation projects produced by or in conjunction with Osamu Tezuka and Tatsuo Yoshida were the first anime to earn my attention and a degree of respect as a youth, and remain some of the only anime I have attempted to study and follow to a reasonable extent to date. While early TV projects were sometimes inadvertently laughable for poor dubbing, run-on translations set to mouths that seemed to never stop opening and closing in the same poses, and English language voice-over “talent” with a penchant for overacting, the background work was often amazingly detailed, special effects at least dramatically passable, and plot lines thoughtful and complex. Tezuka, for one, unlike many other storytellers who followed, also seemed to have a knack of avoiding stories that depended too much upon elements of ethnic folklore too unfamiliar to be comfortably accepted by an international audience, and instead favored storylines with more basic emotional and universal appeal. Tezuka further acknowledged the influence that Western animation had had upon his character styling (particularly in the use of large, Betty Boop-style eyes), and seemed to have a knack for designs that were charming and visually appealing to Western audiences, rather than ugly or downright irritating, as many subsequent anime creations have become. I was a little late to pick up on his earliest black-and white productions, but probably viewed at one time virtually all episodes of his best-remembered color production, Kimba the White Lion, and Yoshida’s Speed Racer.

The Manga-driven animation projects produced by or in conjunction with Osamu Tezuka and Tatsuo Yoshida were the first anime to earn my attention and a degree of respect as a youth, and remain some of the only anime I have attempted to study and follow to a reasonable extent to date. While early TV projects were sometimes inadvertently laughable for poor dubbing, run-on translations set to mouths that seemed to never stop opening and closing in the same poses, and English language voice-over “talent” with a penchant for overacting, the background work was often amazingly detailed, special effects at least dramatically passable, and plot lines thoughtful and complex. Tezuka, for one, unlike many other storytellers who followed, also seemed to have a knack of avoiding stories that depended too much upon elements of ethnic folklore too unfamiliar to be comfortably accepted by an international audience, and instead favored storylines with more basic emotional and universal appeal. Tezuka further acknowledged the influence that Western animation had had upon his character styling (particularly in the use of large, Betty Boop-style eyes), and seemed to have a knack for designs that were charming and visually appealing to Western audiences, rather than ugly or downright irritating, as many subsequent anime creations have become. I was a little late to pick up on his earliest black-and white productions, but probably viewed at one time virtually all episodes of his best-remembered color production, Kimba the White Lion, and Yoshida’s Speed Racer.

I have no specific recollections of weather-related incidents in episodes of Astro Boy or The Wonder 3, nor, surprisingly, have I been able to locate much in the original run of Kimba, the White Lion. (Anyone with information on any such episodes, if any, is invited to contribute). A revival series, The New Adventures of Kimba, the White Lion (1989-90), attempted to fill the void, with an episode bearing the English Title “Flash Flood” (originally titled “Companions”). While perhaps not as complexly plotted as some episodes of the original series, it is somewhat insightful. An unusually heavy rainy season has “made the river angry”, causing it to overflow its banks and send a muddy sea of tidal-like waves across the savannah. Kimba and his pals have spotted it from afar from a hilly vantage point, and set upon the task of leading the jungle animals to higher ground. A sector of the population is directed by an old wise rhino (who seems to have taken the place in this series of the sage Dan’l Baboon) to the high cliffside ledges of an ancient temple, while another section of the population is directed to other high land by crossing the speedy river currents at a shallow crossing point. Kimba is sent to the rear of the parade to look after the welfare of stragglers. He meets a young gazelle who is scared and rather helpless on her own, who has lost track of her mother. She needs all the prodding possible from Kimba and a larger hoofer (a water buffalo?) to muster up enough courage for the river crossing. But Kimba encounters another animal in even greater need of his help. A stranger to the savannah – a domestic cow – has been swept from her farm upstream, and is having difficulty staying afloat. Kimba dives into the water, eventually effecting a rescue and steering her to safety. The bovine is at first quite shaken at the sight of a lion at such close range, but Kimba convinces her that if his intent had been to make an attack, she’d have been pounced upon long before this. Kimba insists that the important thing now is that everyone get to safer ground. But the cow can’t follow at the speed Kimba wants to lead – as she is nearly at the time of delivering her first calf. To make matters more complicated, a native farmer, the owner of the cow, has caught up with them, and, though afraid of the lion, fires a pot-shot at him from a distance. Kimba temporarily scares the hunter away, then prods the cow and the lost gazelle into the only shelter within close range that might withstand the forces of the flood – the wreckage of the fuselage of a twin-engine airplane long ago crashed into the jungle. They all brace themselves as the crest of the forward wave of the flood crashes over the plane, blotting out the light from its portholes. The flood waters rush by on all sides, sweeping across the jungle foliage – but the plane holds firm, and everyone remains dry though shaken.

I have no specific recollections of weather-related incidents in episodes of Astro Boy or The Wonder 3, nor, surprisingly, have I been able to locate much in the original run of Kimba, the White Lion. (Anyone with information on any such episodes, if any, is invited to contribute). A revival series, The New Adventures of Kimba, the White Lion (1989-90), attempted to fill the void, with an episode bearing the English Title “Flash Flood” (originally titled “Companions”). While perhaps not as complexly plotted as some episodes of the original series, it is somewhat insightful. An unusually heavy rainy season has “made the river angry”, causing it to overflow its banks and send a muddy sea of tidal-like waves across the savannah. Kimba and his pals have spotted it from afar from a hilly vantage point, and set upon the task of leading the jungle animals to higher ground. A sector of the population is directed by an old wise rhino (who seems to have taken the place in this series of the sage Dan’l Baboon) to the high cliffside ledges of an ancient temple, while another section of the population is directed to other high land by crossing the speedy river currents at a shallow crossing point. Kimba is sent to the rear of the parade to look after the welfare of stragglers. He meets a young gazelle who is scared and rather helpless on her own, who has lost track of her mother. She needs all the prodding possible from Kimba and a larger hoofer (a water buffalo?) to muster up enough courage for the river crossing. But Kimba encounters another animal in even greater need of his help. A stranger to the savannah – a domestic cow – has been swept from her farm upstream, and is having difficulty staying afloat. Kimba dives into the water, eventually effecting a rescue and steering her to safety. The bovine is at first quite shaken at the sight of a lion at such close range, but Kimba convinces her that if his intent had been to make an attack, she’d have been pounced upon long before this. Kimba insists that the important thing now is that everyone get to safer ground. But the cow can’t follow at the speed Kimba wants to lead – as she is nearly at the time of delivering her first calf. To make matters more complicated, a native farmer, the owner of the cow, has caught up with them, and, though afraid of the lion, fires a pot-shot at him from a distance. Kimba temporarily scares the hunter away, then prods the cow and the lost gazelle into the only shelter within close range that might withstand the forces of the flood – the wreckage of the fuselage of a twin-engine airplane long ago crashed into the jungle. They all brace themselves as the crest of the forward wave of the flood crashes over the plane, blotting out the light from its portholes. The flood waters rush by on all sides, sweeping across the jungle foliage – but the plane holds firm, and everyone remains dry though shaken.

In the morning, as the flood waters subside, the gazelle requests that Kimba keep his word and help her find her mother. But the cow does not want to press on. She reminds Kimba that she is a domestic animal, not born in the wild, and feels at home on the farm. Kimba informs her that he himself was born in the confines of a ship, yet has adapted to the life of the jungle, and its opportunity for freedom for all animals. He appeals to the cow’s sensibilities, first telling her that the humans will offer her no continued home once she no longer can work. The cow, however, states that will not happen, as they need her for her milk. Kimba then asks her to think of the future life of her calf – which need not be within the confines of fences if she remains in the wild. Kimba requests she at least think it over, and allow him to provide her with a guided tour of his lands. The cow sees both positive and negatives sides of jungle life – having a dangerous encounter with a crocodile at a watering hole, yet seeing lush vegetation to graze upon throughout Kimba’s pride lands. The hoofed animal who previously helped Kimba with the gazelle rebuffs the cow over grazing rights, placing another hash mark on the negative side of the cow’s ledger (despite Kimba’s chastising of the territorial attitude of his friend, warning that if the animals don’t learn to get along, none of them will be happy). But the cow also sees another clearing where zebra and other hoofed animals graze freely, and watches a small animal romp freely at play, envisioning the animal as her own calf. Finally, the time comes for the calf’s real-life arrival. The cow has no idea what to do, having expected to rely on the farmer’s assistance, but Kimba tries to bolster her confidence that animals in the wild routinely handle such things on their own. As the cow falls on her side to begin the delivery, there is a commotion in the bushes. The farmer has caught up with them again, leveling his rifle for another shot at Kimba. Only Kimba’s hoofed friend, who has had second thoughts about her selfishness with the grazing rights, saves Kimba by intervening to spoil the farmer’s shot. Kimba leaps into the fray, wresting the rifle from the farmer’s hands with his mouth, then tossing the firearm into the bushes, standing between the gun and the farmer to keep his adversary at bay. The calf arrives, and the farmer forgets about reclaiming the firearm, rushing over to gently lift the newcomer into his arms, pronouncing it healthy and congratulating the mother. When she is strong enough to stand, the cow thanks Kimba for his help, and for her day’s glimpse into what a life of freedom is like – but declares that her proper place is back on the farm, in the care of the farmer (who will continue to seek her out), where she feels at home. The gazelle also departs in the company of others of her kind, who have seen her mother alive and well. Kimba learns the important lesson that what may be right for some is not necessarily right for all, and returns to his own jungle home with a broader mindset than before.

In the morning, as the flood waters subside, the gazelle requests that Kimba keep his word and help her find her mother. But the cow does not want to press on. She reminds Kimba that she is a domestic animal, not born in the wild, and feels at home on the farm. Kimba informs her that he himself was born in the confines of a ship, yet has adapted to the life of the jungle, and its opportunity for freedom for all animals. He appeals to the cow’s sensibilities, first telling her that the humans will offer her no continued home once she no longer can work. The cow, however, states that will not happen, as they need her for her milk. Kimba then asks her to think of the future life of her calf – which need not be within the confines of fences if she remains in the wild. Kimba requests she at least think it over, and allow him to provide her with a guided tour of his lands. The cow sees both positive and negatives sides of jungle life – having a dangerous encounter with a crocodile at a watering hole, yet seeing lush vegetation to graze upon throughout Kimba’s pride lands. The hoofed animal who previously helped Kimba with the gazelle rebuffs the cow over grazing rights, placing another hash mark on the negative side of the cow’s ledger (despite Kimba’s chastising of the territorial attitude of his friend, warning that if the animals don’t learn to get along, none of them will be happy). But the cow also sees another clearing where zebra and other hoofed animals graze freely, and watches a small animal romp freely at play, envisioning the animal as her own calf. Finally, the time comes for the calf’s real-life arrival. The cow has no idea what to do, having expected to rely on the farmer’s assistance, but Kimba tries to bolster her confidence that animals in the wild routinely handle such things on their own. As the cow falls on her side to begin the delivery, there is a commotion in the bushes. The farmer has caught up with them again, leveling his rifle for another shot at Kimba. Only Kimba’s hoofed friend, who has had second thoughts about her selfishness with the grazing rights, saves Kimba by intervening to spoil the farmer’s shot. Kimba leaps into the fray, wresting the rifle from the farmer’s hands with his mouth, then tossing the firearm into the bushes, standing between the gun and the farmer to keep his adversary at bay. The calf arrives, and the farmer forgets about reclaiming the firearm, rushing over to gently lift the newcomer into his arms, pronouncing it healthy and congratulating the mother. When she is strong enough to stand, the cow thanks Kimba for his help, and for her day’s glimpse into what a life of freedom is like – but declares that her proper place is back on the farm, in the care of the farmer (who will continue to seek her out), where she feels at home. The gazelle also departs in the company of others of her kind, who have seen her mother alive and well. Kimba learns the important lesson that what may be right for some is not necessarily right for all, and returns to his own jungle home with a broader mindset than before.

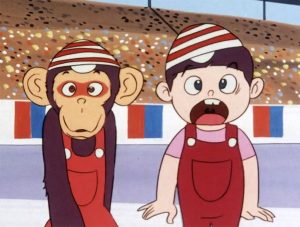

Speed Racer drove in many a climate and weather condition. One of his most memorable – and improbable – of such instances was in: The Most Dangerous Race (5/28 – 6/11/67), a rare three-part story, one of the longest in the series. Speed enters a treacherous Alpine race through hazardous mountain country. His competitors include a team of daredevil drivers known as the Car Acrobatic Team, and the ever-mysterious Racer X (Speed’s older brother Rex, severed from the family in a disagreement with Pops racer over a reckless entry into a race where Rex was clearly outclassed, wrecking Pops’ best car). Speed, Rex, and several of the Acrobatic Team are among a select dozen racers who make it as far as Yawning Chasm Pass, where a raging rainstorm has caused them all to come to a screeching halt. A series of landslides has taken out at least four large sections of the road ahead, leaving stretches of open gorge between them and any hope of continuing the race. The most boisterous of the Acrobatic Team, Snake Oiler, points out that it will be increasingly dangerous for each racer who attempts to hop the gorges, as the rain-soaked soil will likely result in further collapses of roadway as each car impacts the remaining surfaces. He thus calls forward the bravest remaining racers (six, including himself, three others of his team, Speed, and Racer X), and they draw from a set of matchsticks marked with notches to see which drivers will attempt to cross in what order. The Acrobatic team obtain positions one through four, with Snake number four. Racer X obtains number 5, position, and Speed is left “dead last”. Three of the Acrobatic Team meet quick and tragic ends, either failing to gain traction upon their landing points and sliding backwards into the canyon, or in the case of jumper three crashing nose first into a cliff face. As predicted, more rock is jarred loose by every attempt, making the chasms wider. Snake continues to boastfully insist he will make it through for the glory of the team, and indeed does successfully make three of the jumps – but his fate is uncertain, as he seems to overshoot jump number 4. Only Racer X manages to make all the jumps with an almost graceful skill – but again knocking more rock loose in the process. Before making his jump, he cautions Speed against making the attempt, stating it will be no disgrace if he wisely chooses to stay behind. Yet Racer X’s own statement of determination continues to resonate in Speed’s ears as he watches Racer X depart: “As a professional racer, I’ve got to meet the challenge.” Speed will not give up either, and eyes a small doll given to him by Spritel as a good luck charm, hanging from the Mach 5’s rear view mirror – thinking to himself that he will need all the good luck it can give. Speed takes the leap, using the Mach 5’s special hydraulic launchers to propel him upwards from each cliff ledge toward the next rocky landing, and even the projecting mini-wings from below each side door to give each jump added lift. He makes two of the jumps, but a hard landing upon the third rocky ledge dislodges soil under the car’s rear wheels. All traction is lost, and the Mach 5 slides backwards, plunging into the rocky gorge.

Speed Racer drove in many a climate and weather condition. One of his most memorable – and improbable – of such instances was in: The Most Dangerous Race (5/28 – 6/11/67), a rare three-part story, one of the longest in the series. Speed enters a treacherous Alpine race through hazardous mountain country. His competitors include a team of daredevil drivers known as the Car Acrobatic Team, and the ever-mysterious Racer X (Speed’s older brother Rex, severed from the family in a disagreement with Pops racer over a reckless entry into a race where Rex was clearly outclassed, wrecking Pops’ best car). Speed, Rex, and several of the Acrobatic Team are among a select dozen racers who make it as far as Yawning Chasm Pass, where a raging rainstorm has caused them all to come to a screeching halt. A series of landslides has taken out at least four large sections of the road ahead, leaving stretches of open gorge between them and any hope of continuing the race. The most boisterous of the Acrobatic Team, Snake Oiler, points out that it will be increasingly dangerous for each racer who attempts to hop the gorges, as the rain-soaked soil will likely result in further collapses of roadway as each car impacts the remaining surfaces. He thus calls forward the bravest remaining racers (six, including himself, three others of his team, Speed, and Racer X), and they draw from a set of matchsticks marked with notches to see which drivers will attempt to cross in what order. The Acrobatic team obtain positions one through four, with Snake number four. Racer X obtains number 5, position, and Speed is left “dead last”. Three of the Acrobatic Team meet quick and tragic ends, either failing to gain traction upon their landing points and sliding backwards into the canyon, or in the case of jumper three crashing nose first into a cliff face. As predicted, more rock is jarred loose by every attempt, making the chasms wider. Snake continues to boastfully insist he will make it through for the glory of the team, and indeed does successfully make three of the jumps – but his fate is uncertain, as he seems to overshoot jump number 4. Only Racer X manages to make all the jumps with an almost graceful skill – but again knocking more rock loose in the process. Before making his jump, he cautions Speed against making the attempt, stating it will be no disgrace if he wisely chooses to stay behind. Yet Racer X’s own statement of determination continues to resonate in Speed’s ears as he watches Racer X depart: “As a professional racer, I’ve got to meet the challenge.” Speed will not give up either, and eyes a small doll given to him by Spritel as a good luck charm, hanging from the Mach 5’s rear view mirror – thinking to himself that he will need all the good luck it can give. Speed takes the leap, using the Mach 5’s special hydraulic launchers to propel him upwards from each cliff ledge toward the next rocky landing, and even the projecting mini-wings from below each side door to give each jump added lift. He makes two of the jumps, but a hard landing upon the third rocky ledge dislodges soil under the car’s rear wheels. All traction is lost, and the Mach 5 slides backwards, plunging into the rocky gorge.

A still image on the canyon floor below shows a long trail of skidding car tracks in the dirt, disappearing from view over a small rise – and lying sprawled on the ground a short distance from where the tracks disappear, Spritel’s good luck charm. Soon we glimpse a larger figure, also sprawled in the dirt, but stirring. It is Speed, somehow miraculously having survived the fall and a spill from the driver’s seat. (So much for his buckled seat belt.) What is even more unbelievable is that the Mach 5 is also there – not dented, or on fire, or even upside down – but looking virtually untouched! What miracle alloy has Pops Racer constructed this wonder car of? For that matter, what is Speed constructed of?? To make things even more improbable, though we don’t fully know quite how bad a fall he took over ridge four, Snake is there, too – also with a car that seems virtually untouched. This could only happen in a Manga. Speed himself is the only one who seems worse for wear. Though unbruised on the surface, Speed has suffered a concussion, and cannot bear light upon his eyes, rendering him effectively blind to his surroundings. He feels his way around aimlessly, searching for something familiar. He finds and clutches the good luck doll, but struggles to find the Mach 5, though it is close nearby. Snake observes his condition, and assumes he is out of the race for good. Offering no assistance, he roars off in his own car, Speed hearing his departure. But there is another in the canyon. Racer X has doubled back after successfully negotiating the downhill course, attempting to determine the condition of his brother. He witnesses Speed finally find the Mach 5, and thank his good luck that she feels like she is in one piece. Speed successfully starts the engine by mere feel, but quickly realizes, how is he to drive the road if he can’t see? But he hears another engine loudly rev up ahead of him – the unmistakable sound of Racer X’s car. Determined to go on, Speed sets foot on the gas pedal, and aims the wheel in the direction of the engine sound. Racer X, fully aware of Speed’s following, drives at a fast but easy-to-follow pace, allowing Speed to play ear-tag behind him – a task still quire treacherous, as Speed makes frequent slight miscalculations, sideswiping rocky faces along the roadway, and coming dangerously close to drop-off ledges along the outer edge of the roadway. Still, Speed hangs on – until he reaches a spot where his rear wheels get stuck in a wet soft-shoulder. Speed finds the one feature of the Mach 5 which will not work is its traction-tread super tires, which will not activate tread extensions to get him out of the predicament. How can Racer X help, without looking suspicious, or giving away his family concern for Speed? One way presents itself, as Racer X sees a cliff face straight ahead. Instead of following the road, Racer X deliberately aims for the cliff – and crashes his car straight into it. Speed hears the crash, and jumps out of his own car to offer assistance to Racer X. Racer X has skillfully disabled his own car, but left himself unhurt. Knowing that Speed will be unable to see Racer X’s true condition, Rex fakes some groans of pain as Speed approaches his sounds, and claims that his legs have been broken. Speed lifts Rex’s weight upon his shoulder, and with Rex directing the way, carries Rex back to the Mach 5. Rex directs Speed’s shifting to extricate the Mach 5 from its mired position – then suggests the only way they can possibly hope to overtake Snake and win the race. Racer X will act as Speed’s eyes, directing his driving, while Speed will provide Racer X’s “legs” by accepting him as passenger. The idea works, and within a few hours, they have caught up to the last checkpoint on the course, with Snake only a short distance ahead.

A still image on the canyon floor below shows a long trail of skidding car tracks in the dirt, disappearing from view over a small rise – and lying sprawled on the ground a short distance from where the tracks disappear, Spritel’s good luck charm. Soon we glimpse a larger figure, also sprawled in the dirt, but stirring. It is Speed, somehow miraculously having survived the fall and a spill from the driver’s seat. (So much for his buckled seat belt.) What is even more unbelievable is that the Mach 5 is also there – not dented, or on fire, or even upside down – but looking virtually untouched! What miracle alloy has Pops Racer constructed this wonder car of? For that matter, what is Speed constructed of?? To make things even more improbable, though we don’t fully know quite how bad a fall he took over ridge four, Snake is there, too – also with a car that seems virtually untouched. This could only happen in a Manga. Speed himself is the only one who seems worse for wear. Though unbruised on the surface, Speed has suffered a concussion, and cannot bear light upon his eyes, rendering him effectively blind to his surroundings. He feels his way around aimlessly, searching for something familiar. He finds and clutches the good luck doll, but struggles to find the Mach 5, though it is close nearby. Snake observes his condition, and assumes he is out of the race for good. Offering no assistance, he roars off in his own car, Speed hearing his departure. But there is another in the canyon. Racer X has doubled back after successfully negotiating the downhill course, attempting to determine the condition of his brother. He witnesses Speed finally find the Mach 5, and thank his good luck that she feels like she is in one piece. Speed successfully starts the engine by mere feel, but quickly realizes, how is he to drive the road if he can’t see? But he hears another engine loudly rev up ahead of him – the unmistakable sound of Racer X’s car. Determined to go on, Speed sets foot on the gas pedal, and aims the wheel in the direction of the engine sound. Racer X, fully aware of Speed’s following, drives at a fast but easy-to-follow pace, allowing Speed to play ear-tag behind him – a task still quire treacherous, as Speed makes frequent slight miscalculations, sideswiping rocky faces along the roadway, and coming dangerously close to drop-off ledges along the outer edge of the roadway. Still, Speed hangs on – until he reaches a spot where his rear wheels get stuck in a wet soft-shoulder. Speed finds the one feature of the Mach 5 which will not work is its traction-tread super tires, which will not activate tread extensions to get him out of the predicament. How can Racer X help, without looking suspicious, or giving away his family concern for Speed? One way presents itself, as Racer X sees a cliff face straight ahead. Instead of following the road, Racer X deliberately aims for the cliff – and crashes his car straight into it. Speed hears the crash, and jumps out of his own car to offer assistance to Racer X. Racer X has skillfully disabled his own car, but left himself unhurt. Knowing that Speed will be unable to see Racer X’s true condition, Rex fakes some groans of pain as Speed approaches his sounds, and claims that his legs have been broken. Speed lifts Rex’s weight upon his shoulder, and with Rex directing the way, carries Rex back to the Mach 5. Rex directs Speed’s shifting to extricate the Mach 5 from its mired position – then suggests the only way they can possibly hope to overtake Snake and win the race. Racer X will act as Speed’s eyes, directing his driving, while Speed will provide Racer X’s “legs” by accepting him as passenger. The idea works, and within a few hours, they have caught up to the last checkpoint on the course, with Snake only a short distance ahead.

Snake’s car was also not entirely unscathed from the canyon fall. Unnoticed by Snake, it has begun leaking oil badly, leaving a trail on the road behind him. Racer X sees it, but tells Speed if he really wants to win, he should ignore it, and concentrate on trying to pass Snake. But Speed realizes that, with the speed of Snake’s engine, such a condition is likely to result in a fire and possible explosion. Speed thus vows that the right thing to do is try to warm Snake. Though not Racer X’s first choice of alternatives, he respects his brother’s values of a life over a victory, and directs Speed until he is running a parallel course alongside Snake’s car. Speed calls out to Snake about the oil hazard. Snake refuses to believe him, thinking it is a trick to distract him from the impending finish line – and continues gunning the engine at full capacity. Though the finish line is in sight, Snake never makes it, as the rear half of his car bursts into flame. A crash into the wall puts a stop to all chances of Snake’s victory, and Speed, though saddened at Snake’s refusal to heed his warning, crosses the finish line, accepting blindly the huge trophy awarded him. He seeks Racer X, feeling that the trophy should be shared with him – but is informed that the Mach 5 is empty. He realizes that Racer X’s legs were okay all along – and is left with the mystery of why Racer X helped him. From the other end of the stadium, Racer X watches Speed from the shadows, as Speed is led to the infirmary for aid for his eyes, and Racer X reflects that more people should be like Speed, and how proud he is to have Speed for a little brother.

Snake’s car was also not entirely unscathed from the canyon fall. Unnoticed by Snake, it has begun leaking oil badly, leaving a trail on the road behind him. Racer X sees it, but tells Speed if he really wants to win, he should ignore it, and concentrate on trying to pass Snake. But Speed realizes that, with the speed of Snake’s engine, such a condition is likely to result in a fire and possible explosion. Speed thus vows that the right thing to do is try to warm Snake. Though not Racer X’s first choice of alternatives, he respects his brother’s values of a life over a victory, and directs Speed until he is running a parallel course alongside Snake’s car. Speed calls out to Snake about the oil hazard. Snake refuses to believe him, thinking it is a trick to distract him from the impending finish line – and continues gunning the engine at full capacity. Though the finish line is in sight, Snake never makes it, as the rear half of his car bursts into flame. A crash into the wall puts a stop to all chances of Snake’s victory, and Speed, though saddened at Snake’s refusal to heed his warning, crosses the finish line, accepting blindly the huge trophy awarded him. He seeks Racer X, feeling that the trophy should be shared with him – but is informed that the Mach 5 is empty. He realizes that Racer X’s legs were okay all along – and is left with the mystery of why Racer X helped him. From the other end of the stadium, Racer X watches Speed from the shadows, as Speed is led to the infirmary for aid for his eyes, and Racer X reflects that more people should be like Speed, and how proud he is to have Speed for a little brother.

Rankin-Bass had its share of prime-time specials dealing with cold weather. While snow flurries seemed to appear in some form in most of their productions, we’ll concentrate on three classics for the holiday season where weather became a central theme of the story line.

Rankin-Bass had its share of prime-time specials dealing with cold weather. While snow flurries seemed to appear in some form in most of their productions, we’ll concentrate on three classics for the holiday season where weather became a central theme of the story line.

Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (The General Electric Fantasy Hour, 12/6/64 – Larry Roemer, dir.) is of course the one that really put the studio on the map. Throwing away most of the book upon which the Max Fleischer short previously reviewed in this series was based, writer Romeo Muller came up with a new one-hour scenario for a special in stop-motion, filled with new and engaging characters to pad out the original slim storyline, tug a little deeper at the heartstrings, provide a bit of a moral lesson, and spotlight a wonderful new score of songs written by Johnny Marks (the composer of the Gene Autry musical hit, which by this time had long become a mainstay of the holiday season and a well-known million seller). Of Marks’ new compositions, it can truly be said, not a bad apple in the carload – including at least one other song which has gone on to have a life of its own: “Have a Holly, Jolly Christmas.” Folk singer/actor Burl Ives would provide the special with the read of a lifetime as narrator Sam the Snowman, probably his best remembered role (only closely approached by his lesser-known Disney appearances in “Summer Magic” and “So Dear To My Heart”). While the remainder of the voice cast were not household names, everyone pitched in with spirited and meaningful character reads, breathing life into such varied characters as Hermie, the runaway elf who dreams of an unheard-of elf career as a dentist. Yukon Cornelius, an arctic prospector fixated upon making the biggest silver or gold strike this side of Hudson Bay, but who ends up perfectly satisfied with a find of a rare peppermint mine. A myriad of living playthings who are rejected by the world for their differences from the norm (similar to Rudolph’s nose problem), and reside together upon the Island of Misfit Toys. And even a ferocious yet eventually lovable Yeti or Abominable Snowman (nicknamed “Bumble” by Cornelius). All these characters’ fates intertwine to provide Rudolph with a life lesson in dealing with the criticisms of the unapproving world, learning to face your troubles, and eventually make the most out of your differences when they can prove to be hidden talents.

The character clashes even spark moments of bravery, as Rudolph, and especially Hermie and Yukon, effect a rescue of Rudolph’s family and girl from the clutches of the Bumble. The whole thing is frameworked, however, by record-braking weather. Headlines scream, “Cold Wave in 12th Day”. “We’re FrOzen”, and “Foul Weather May Postpone Christmas.” The storm is just swinging into full fury when Rudolph and the principal cast return to Christmas Town and tell the story of their long adventures and lessons. Santa, who had approved Rudolph’s exclusion from the reindeer games, has pangs of conscience and realization that he and the other “normal” folk have been a little hard on the misfits, and that even he can be wrong (an original story touch which had probably never up to this point been explored in any tale about Santa Claus). As Rudolph is accepted back into reindeer society, an elf advises Santa of the latest weather reports. No let-up of the storm in sight. For the first time, Santa faces the grim duty of advising everyone that Christmas must be cancelled, as “Everything’s grounded.” He bemoans the fate of the poor kids who’ve been so good this year, but errs in favor of the safety of his team, stating that he can’t chance it. As he enters the great hall of Santa’s castle to make the landmark announcement, Rudolph is standing close by, and the glare from his nose causes Santa’s eyes to contract and wince from the brightness. Returning to the original storyline, Santa hits upon the idea of ideas. “The way I see it now, that nose will cut through the murkiest storm they can dish up.” The famous question from the song, “Won’t you guide my sleigh tonight?” is asked, and Rudolph responds, “It will be an honor, sir.” As the song tells for the story finale, Rudolph goes “down in history”, saving the holiday, and continuing to do so year after year.

The character clashes even spark moments of bravery, as Rudolph, and especially Hermie and Yukon, effect a rescue of Rudolph’s family and girl from the clutches of the Bumble. The whole thing is frameworked, however, by record-braking weather. Headlines scream, “Cold Wave in 12th Day”. “We’re FrOzen”, and “Foul Weather May Postpone Christmas.” The storm is just swinging into full fury when Rudolph and the principal cast return to Christmas Town and tell the story of their long adventures and lessons. Santa, who had approved Rudolph’s exclusion from the reindeer games, has pangs of conscience and realization that he and the other “normal” folk have been a little hard on the misfits, and that even he can be wrong (an original story touch which had probably never up to this point been explored in any tale about Santa Claus). As Rudolph is accepted back into reindeer society, an elf advises Santa of the latest weather reports. No let-up of the storm in sight. For the first time, Santa faces the grim duty of advising everyone that Christmas must be cancelled, as “Everything’s grounded.” He bemoans the fate of the poor kids who’ve been so good this year, but errs in favor of the safety of his team, stating that he can’t chance it. As he enters the great hall of Santa’s castle to make the landmark announcement, Rudolph is standing close by, and the glare from his nose causes Santa’s eyes to contract and wince from the brightness. Returning to the original storyline, Santa hits upon the idea of ideas. “The way I see it now, that nose will cut through the murkiest storm they can dish up.” The famous question from the song, “Won’t you guide my sleigh tonight?” is asked, and Rudolph responds, “It will be an honor, sir.” As the song tells for the story finale, Rudolph goes “down in history”, saving the holiday, and continuing to do so year after year.

The film discussed above having become an instant hit, and continuing to this day as an annual holiday tradition, Rankin-Bass looked around within the next few years for another Christmas novelty song to adapt to film. Two more projects would develop from the search – one in stop-motion with which we will not deal here, Santa Claus Is Comin’ To Town, and one as a traditional 2-D animated film at a half-hour length – Frosty the Snowman (12/7/69). “Frosty” shows several earmarks of being thrown together in a comparative hurry. First, 2-D animation was nor Rankin-Bass’s strong point. Their art work (with nuts and bolts animation farmed out overseas at Mushi Productions) always had a certain hesitating, stiff appearance to it, and facial expressions were often awkward and rough. (I could never separate it from a series of cheap commercials the studio appears to have concurrently produced for the American Dental Council, and sometimes felt in the early viewings of the special as if I was watching an extended-length commercial on how to brush your teeth.) Editing work was also rough, with jerky splices between shots. Camera work too was rather amateurish, with some scenes where you could easily see the shadow of cels cast upon the painted backgrounds as if not pressed flat enough on the camera mount. Directing was also second-rate (Rankin and Bass now taking the credit), with awkward long pauses between some dialogue lines, and odd voice-mixing in group shots of the children who build Frosty. Yet, despite all these flaws, the studio scored again, with its second biggest and second longest-running hit. On the positive side of the ledger were a seasoned voice cast (veteran comedy actor Billy DeWolfe as Professor Hinkle the Magician, current well-known comedian/variety show personality Jackie Vernon as Frosty, Paul Frees as Santa and as other incidental characters, and legend Jimmy Durante (who had himself scored a good-selling version of the title song many years before) as narrator. These actors, together with a sensitive read for a new juvenile character named Karen, provide the spark of the half-hour and keep the script moving past its duller moments and hesitations. A surprise Disney-style tug at the heartstrings by way of a near-death scene gives the story a memorable wind-up, serving to elevate the special beyond other forgotten tales of living snowmen such as those produced by Terrytoons in the 1940’s, and a clever non-violent dispatch of the villain also provides a landmark moment that allows the film to stick in the memory. Proof positive that a writer’s pen and a microphone can be the saving grace for even a semi-poor production, much as Chuck Jones had observed in labelling many inexpensive yet successful early TV projects “illustrated radio”.

The film discussed above having become an instant hit, and continuing to this day as an annual holiday tradition, Rankin-Bass looked around within the next few years for another Christmas novelty song to adapt to film. Two more projects would develop from the search – one in stop-motion with which we will not deal here, Santa Claus Is Comin’ To Town, and one as a traditional 2-D animated film at a half-hour length – Frosty the Snowman (12/7/69). “Frosty” shows several earmarks of being thrown together in a comparative hurry. First, 2-D animation was nor Rankin-Bass’s strong point. Their art work (with nuts and bolts animation farmed out overseas at Mushi Productions) always had a certain hesitating, stiff appearance to it, and facial expressions were often awkward and rough. (I could never separate it from a series of cheap commercials the studio appears to have concurrently produced for the American Dental Council, and sometimes felt in the early viewings of the special as if I was watching an extended-length commercial on how to brush your teeth.) Editing work was also rough, with jerky splices between shots. Camera work too was rather amateurish, with some scenes where you could easily see the shadow of cels cast upon the painted backgrounds as if not pressed flat enough on the camera mount. Directing was also second-rate (Rankin and Bass now taking the credit), with awkward long pauses between some dialogue lines, and odd voice-mixing in group shots of the children who build Frosty. Yet, despite all these flaws, the studio scored again, with its second biggest and second longest-running hit. On the positive side of the ledger were a seasoned voice cast (veteran comedy actor Billy DeWolfe as Professor Hinkle the Magician, current well-known comedian/variety show personality Jackie Vernon as Frosty, Paul Frees as Santa and as other incidental characters, and legend Jimmy Durante (who had himself scored a good-selling version of the title song many years before) as narrator. These actors, together with a sensitive read for a new juvenile character named Karen, provide the spark of the half-hour and keep the script moving past its duller moments and hesitations. A surprise Disney-style tug at the heartstrings by way of a near-death scene gives the story a memorable wind-up, serving to elevate the special beyond other forgotten tales of living snowmen such as those produced by Terrytoons in the 1940’s, and a clever non-violent dispatch of the villain also provides a landmark moment that allows the film to stick in the memory. Proof positive that a writer’s pen and a microphone can be the saving grace for even a semi-poor production, much as Chuck Jones had observed in labelling many inexpensive yet successful early TV projects “illustrated radio”.

The first snow of the season falls upon a small country town, on the day before Christmas – a magical “Christmas snow” which always gives the feeling to young and old alike that something wonderful is about to happen. At the schoolhouse, a party is in progress to celebrate the last day of school before the winter holidays. The teacher has hired Professor Hinkle (just about the worst magician in the world) and his rabbit-in-a-hat Hocus Pocus to entertain. Hinkle’s lame card stunts and egg-in-the-hat truck fail to capture the interest of the students, and when the bell sounds the end of the school day, the students stampede out the door in the middle of Hinkle’s act. Hinkle’s pride takes a blow at the thought of being abandoned over some mere “frozen water”. He is angrier still when his hat is blown off his head, sailing to a clearing where the children are building a snowman whom they have named Frosty, and lands on the snowman’s brow. Sparkles light up around the snowman’s form, and his coal eyes develop moving pupils, as he begins to move and speak, declaring his own “Happy Birthday”. The wind catches the hat again, blowing it off the snowman and to a spot where Hinkle retrieves it. The snowman reverts instantly back to rigid, immobile form. Hinkle has seen the event, as has his rabbit – but Hinkle clings tight to the hat, and begins attempting to convince the children that they can’t believe what they have just seen. When they are grown up, they will realize the childishness of the idea – snowmen can’t come to life. At the same time, he conspiratorially whispers to Hocus Pocus that the hat must somehow have real magic now, and if he plays his cards right, it will make him a millionaire magician. Hinkle turns to leave, stuffing Hocus deep inside the hat, and placing them on his own head. But Hocus doesn’t feel right about what Hinkle is doing, and hops off of the magician’s head, carrying the hat back to Frosty. Frosty again says “Happy Birthday”, then realizes he just talked. “What’s the joke?” he asks the kids, disbelieving himself that he can be “all living”. But he tests his powers, juggling, sweeping, and even trying to count up to ten (making it only up to five before he gets stuck). Now convinced himself of the hat’s magic, Frosty remarks, “What a neat thing to happen to a nice guy like me.”

Still from the animated television Christmas special, “Frosty The Snowman,” depicting Karen riding on Frosty’s back, 1969. (Photo by CBS/Getty Images)

The train travels for many hours into the frozen woods in the dead of night. A refrigerated box car is a fine way to travel, for a snowman, or a furry rabbit. But for Karen – – aah-choo!! Frosty realizes she can’t take the cold much longer, and chances it to get her outside, jumping out of the car with Karen in his arms, and Hocus following. Hinkle is caught by surprise by this move, and his jump is not so graceful, leaving him sprawled alongside the tracks. Hocus acts as animal translator to a forest community of critters, who assist him in building a campfire for Karen to keep warm. The animals are waiting for Santa’s arrival, and Frosty believes Santa is the only one who can get him to the North Pole before he melts, and Karen home before she freezes. Hocus waits with the other animals to alert Santa. But Hinkle catches up, cruelly blowing out Karen’s campfire, and demanding the hat back, or else. “Or else, what?” asks Frosty. “Don’t bother me with details”, replies Hinkle. Frosty and Karen make a fast escape downslope – made of snow himself, Frosty is the fastest bellyflopper in the world.

The train travels for many hours into the frozen woods in the dead of night. A refrigerated box car is a fine way to travel, for a snowman, or a furry rabbit. But for Karen – – aah-choo!! Frosty realizes she can’t take the cold much longer, and chances it to get her outside, jumping out of the car with Karen in his arms, and Hocus following. Hinkle is caught by surprise by this move, and his jump is not so graceful, leaving him sprawled alongside the tracks. Hocus acts as animal translator to a forest community of critters, who assist him in building a campfire for Karen to keep warm. The animals are waiting for Santa’s arrival, and Frosty believes Santa is the only one who can get him to the North Pole before he melts, and Karen home before she freezes. Hocus waits with the other animals to alert Santa. But Hinkle catches up, cruelly blowing out Karen’s campfire, and demanding the hat back, or else. “Or else, what?” asks Frosty. “Don’t bother me with details”, replies Hinkle. Frosty and Karen make a fast escape downslope – made of snow himself, Frosty is the fastest bellyflopper in the world.

Frosty and Karen discover a greenhouse for Christmas poinsettias. He gently carries Karen inside to warm up, realizing that he mustn’t stay long inside himself, or he’ll “really make a splash in the world.” But his stay is much longer than planned, as a winded Hinkle again catches up, and locks the greenhouse door from the outside, trapping Frosty in. The clatter of sleigh bells proclaims the arrival of Santa and Hocus above. Hinkle hides as Santa approaches the greenhouse door. A terrible sight meets Santa’s eyes. Karen is bitterly weeping, over a large puddle in which rests the hat, a button, and several lumps of coal. Poor Frosty has melted away. But Santa pats Karen reassuringly, stating “Frosty’s not gone for good.” He explains that Christmas snow, while it may disappear at times to take the forms of spring and summer rain, will turn to Christmas snow all over again when hit by a good December breeze. There is still plenty of that right outside the greenhouse door, and one blast transforms the puddle and its contents back into snowman shape again – all except the hat, which Hocus attempts to put upon Frosty himself. Not so fast, as Hinkle reveals himself from the shadows, and demands the hat be returned to him. Santa cautions him, and Hinkle responds “Just what are you going to do about it?” “If you so much as lay a finger on the brim, I’ll never bring you another Christmas present as long as you live.” Hinkle nearly goes into shock. “No more trick balls…magic cards…?” “No more anything”, calmly responds Santa in wonderful underplay. Hinkle gives a little kick at the dirt in frustration, gently complaining that evil magicians have to make a living, too. Santa directs Hinkle to go home and write, “I am very sorry for what I did to Frosty” a hundred zillion times – then maybe, just maybe, he’ll find something in his stocking tomorrow morning. “A-a new hat, maybe?’ asks Hinkle with some renewed hope. He departs in a hurry. “Sorry to lose and run, but I’ve got to get busy writing. Busy, busy, busy!” The hat is restored to Frosty, and Karen is returned home in Santa’s sleigh. She says goodbye to Frosty as he rides with Santa on the return to the North Pole, but Frosty reappears in town with every new Christmas snow for a big parade – in which even Hinkle marches, proudly wearing his new chapeau.

Frosty and Karen discover a greenhouse for Christmas poinsettias. He gently carries Karen inside to warm up, realizing that he mustn’t stay long inside himself, or he’ll “really make a splash in the world.” But his stay is much longer than planned, as a winded Hinkle again catches up, and locks the greenhouse door from the outside, trapping Frosty in. The clatter of sleigh bells proclaims the arrival of Santa and Hocus above. Hinkle hides as Santa approaches the greenhouse door. A terrible sight meets Santa’s eyes. Karen is bitterly weeping, over a large puddle in which rests the hat, a button, and several lumps of coal. Poor Frosty has melted away. But Santa pats Karen reassuringly, stating “Frosty’s not gone for good.” He explains that Christmas snow, while it may disappear at times to take the forms of spring and summer rain, will turn to Christmas snow all over again when hit by a good December breeze. There is still plenty of that right outside the greenhouse door, and one blast transforms the puddle and its contents back into snowman shape again – all except the hat, which Hocus attempts to put upon Frosty himself. Not so fast, as Hinkle reveals himself from the shadows, and demands the hat be returned to him. Santa cautions him, and Hinkle responds “Just what are you going to do about it?” “If you so much as lay a finger on the brim, I’ll never bring you another Christmas present as long as you live.” Hinkle nearly goes into shock. “No more trick balls…magic cards…?” “No more anything”, calmly responds Santa in wonderful underplay. Hinkle gives a little kick at the dirt in frustration, gently complaining that evil magicians have to make a living, too. Santa directs Hinkle to go home and write, “I am very sorry for what I did to Frosty” a hundred zillion times – then maybe, just maybe, he’ll find something in his stocking tomorrow morning. “A-a new hat, maybe?’ asks Hinkle with some renewed hope. He departs in a hurry. “Sorry to lose and run, but I’ve got to get busy writing. Busy, busy, busy!” The hat is restored to Frosty, and Karen is returned home in Santa’s sleigh. She says goodbye to Frosty as he rides with Santa on the return to the North Pole, but Frosty reappears in town with every new Christmas snow for a big parade – in which even Hinkle marches, proudly wearing his new chapeau.

A more uneven effort was the stop-motion special, The Year Without a Santa Claus (12/10/74). Based on a children’s book, it tells a convoluted tale of Santa’s wearying of the annual labor of readying for the big day of toy delivery on Christmas eve, and for once wishing he could get some rest. It is sort of a sequel to “Santa Claus Is Comin’ To Town”, with Mickey Rooney reprising his role as Santa, now elderly and fully matured. Shirley Booth takes over the voice of the advanced-in-years Mrs. Claus, formerly known as Jessica. The principal problem with the script is a total inconsistency between the first half hour and the second, in which Mrs. Claus and Santa’s lead elves appear to undergo a complete reversal in goals, first trying to plot to save Christmas whether Santa shows up or not, then abruptly shifting to wanting to see the world acknowledge Santa’s holiday. We are quite confused as the second half commences, as one of Santa’s smallest reindeer is taken into custody by a dog catcher in Southtown, mistaken as a mutt. Santa’s elves can’t convince the local law authority that the captive is a reindeer, or that they are elves, unless they present some proof – like performing some elf magic, to make it snow in the South. Of course, this is not actually within the elves’ power, and, in order to make this unusual request come true, Mrs. Claus and the elves are pressed into a bureaucratic nightmare with the forces of nature, quite similar in style to Raggedy Ann’s troubles attempting to obtain wintertime sunshine in “Suddenly It’s Spring”. Mrs. Claus first visits Snow Miser, an icicle-laden blue giant who sits on a throne of ice in a castle of snow, typically in control of the Northern climes. He is brother to a shorter giant – a fiery imp who looks like he could be a distant relation to the devil’s minions, named Heat Miser, who controls sunny days from another castle stronghold in the heart of a volcano. Each has a great sense for making a strong impression in public relations – greeting their guests with a toe-tapping song and dance (straw hat included) with alternate lyrics, “They Call Me Snow Miser/Heat Miser”. The number virtually stops the show, and is the best-remembered part of the special. Snow Miser is more than happy to offer his snow, considering Santa a sort of good will ambassador for his kind of weather. However, he can’t get his cold down South unless Heat Miser lets up on the heat, which normally turns anything Snow Miser sends down there into useless fog or rain. At Heat Miser’s palace, the imp is aghast at the suggestion of “Snow in the South???”, and also not too partial to Santa in general, whom he thinks should stop providing free advertising for his brother, and instead wear a bathing suit once in a while. Heat Miser suggests a deal – trade a day of snow in the South for a day of heat in some Northern territory – like the North Pole. Calling up his brother on the “Hot Line”, Heat Miser proposes his terms. The two brothers exchange a lively sibling-rivalry war of words, hurling weather puns and insults at each other, and ending the call by trying to shoot energy zaps at one another (which merely cancel each other out in the middle). Mrs. Claus has had enough, and can see she’s getting nowhere. She leaves with the elves, through with fooling around, and “goes right to the top” – Mother Nature. Mother is played up in direct parody of a series of commercials then going around for Chiffon Margarine, in which graceful Mother Nature is given a sample of the product, mistaking it for butter, then reacts with thunderbolts when she finds it is margarine, with the catch phrase “It’s not nice to fool Mother Nature.” True to form, Mother summons both of the troublesome Miser Brothers into her presence, and lays down the law to them with a few well-placed thunderbolts close to their rears, getting them to compromise to provide the needed snow in the South, the boys only having the courage to politely respond, “Yes, Mother dear.”

A more uneven effort was the stop-motion special, The Year Without a Santa Claus (12/10/74). Based on a children’s book, it tells a convoluted tale of Santa’s wearying of the annual labor of readying for the big day of toy delivery on Christmas eve, and for once wishing he could get some rest. It is sort of a sequel to “Santa Claus Is Comin’ To Town”, with Mickey Rooney reprising his role as Santa, now elderly and fully matured. Shirley Booth takes over the voice of the advanced-in-years Mrs. Claus, formerly known as Jessica. The principal problem with the script is a total inconsistency between the first half hour and the second, in which Mrs. Claus and Santa’s lead elves appear to undergo a complete reversal in goals, first trying to plot to save Christmas whether Santa shows up or not, then abruptly shifting to wanting to see the world acknowledge Santa’s holiday. We are quite confused as the second half commences, as one of Santa’s smallest reindeer is taken into custody by a dog catcher in Southtown, mistaken as a mutt. Santa’s elves can’t convince the local law authority that the captive is a reindeer, or that they are elves, unless they present some proof – like performing some elf magic, to make it snow in the South. Of course, this is not actually within the elves’ power, and, in order to make this unusual request come true, Mrs. Claus and the elves are pressed into a bureaucratic nightmare with the forces of nature, quite similar in style to Raggedy Ann’s troubles attempting to obtain wintertime sunshine in “Suddenly It’s Spring”. Mrs. Claus first visits Snow Miser, an icicle-laden blue giant who sits on a throne of ice in a castle of snow, typically in control of the Northern climes. He is brother to a shorter giant – a fiery imp who looks like he could be a distant relation to the devil’s minions, named Heat Miser, who controls sunny days from another castle stronghold in the heart of a volcano. Each has a great sense for making a strong impression in public relations – greeting their guests with a toe-tapping song and dance (straw hat included) with alternate lyrics, “They Call Me Snow Miser/Heat Miser”. The number virtually stops the show, and is the best-remembered part of the special. Snow Miser is more than happy to offer his snow, considering Santa a sort of good will ambassador for his kind of weather. However, he can’t get his cold down South unless Heat Miser lets up on the heat, which normally turns anything Snow Miser sends down there into useless fog or rain. At Heat Miser’s palace, the imp is aghast at the suggestion of “Snow in the South???”, and also not too partial to Santa in general, whom he thinks should stop providing free advertising for his brother, and instead wear a bathing suit once in a while. Heat Miser suggests a deal – trade a day of snow in the South for a day of heat in some Northern territory – like the North Pole. Calling up his brother on the “Hot Line”, Heat Miser proposes his terms. The two brothers exchange a lively sibling-rivalry war of words, hurling weather puns and insults at each other, and ending the call by trying to shoot energy zaps at one another (which merely cancel each other out in the middle). Mrs. Claus has had enough, and can see she’s getting nowhere. She leaves with the elves, through with fooling around, and “goes right to the top” – Mother Nature. Mother is played up in direct parody of a series of commercials then going around for Chiffon Margarine, in which graceful Mother Nature is given a sample of the product, mistaking it for butter, then reacts with thunderbolts when she finds it is margarine, with the catch phrase “It’s not nice to fool Mother Nature.” True to form, Mother summons both of the troublesome Miser Brothers into her presence, and lays down the law to them with a few well-placed thunderbolts close to their rears, getting them to compromise to provide the needed snow in the South, the boys only having the courage to politely respond, “Yes, Mother dear.”

While we’re on the subject of specials, the Peanuts series produced for its second prime-time outing Charlie Brown’s All Stars! (Lee Mendelson/Bill Melendez Productions, 6/8/66 – Bill Melendez, dir.), providing a vehicle for the compilation of many of Charles Schulz’s ideas fot Charlie and the gang on the baseball diamond. After several typical mishaps, and a season-opening loss of 123 to nothing, the members of the team finally decide they’ve had it with baseball and Charlie’s flawless losing record, and abandon Charlie’s team, pursuing other summertime activities. “I refuse to play left field for a sinking ship”, shouts Lucy. But opportunity presents itself when a local hardware store proprietor sees possibilities in promoting Charlie’s team with real uniforms into a genuine league. Charlie breaks the news to his former teammates, who are lured back into regrouping at the promise of the uniforms. But a call from the hardware store puts the kibosh on the plans, when Charlie is informed that the league does not allow girls or dogs as players. Remaining faithful to his friends and dog, Charlie refuses to oust these members from his team, and respectfully declines the sponsorship offer. Linus is the only one who is let in on the disastrous turn of events, and predicts that Lucy will blow sky high when she hears the news. In a last effort to keep the team together, Charlie decides not to break the word to the others until after today’s game, hoping that if the inspired team can win one game, it’ll be enough to take their minds off those stupid uniforms. “I don’t know, Charlie Brown”, reflects Linus. “Perhaps you should just leave town.”

While we’re on the subject of specials, the Peanuts series produced for its second prime-time outing Charlie Brown’s All Stars! (Lee Mendelson/Bill Melendez Productions, 6/8/66 – Bill Melendez, dir.), providing a vehicle for the compilation of many of Charles Schulz’s ideas fot Charlie and the gang on the baseball diamond. After several typical mishaps, and a season-opening loss of 123 to nothing, the members of the team finally decide they’ve had it with baseball and Charlie’s flawless losing record, and abandon Charlie’s team, pursuing other summertime activities. “I refuse to play left field for a sinking ship”, shouts Lucy. But opportunity presents itself when a local hardware store proprietor sees possibilities in promoting Charlie’s team with real uniforms into a genuine league. Charlie breaks the news to his former teammates, who are lured back into regrouping at the promise of the uniforms. But a call from the hardware store puts the kibosh on the plans, when Charlie is informed that the league does not allow girls or dogs as players. Remaining faithful to his friends and dog, Charlie refuses to oust these members from his team, and respectfully declines the sponsorship offer. Linus is the only one who is let in on the disastrous turn of events, and predicts that Lucy will blow sky high when she hears the news. In a last effort to keep the team together, Charlie decides not to break the word to the others until after today’s game, hoping that if the inspired team can win one game, it’ll be enough to take their minds off those stupid uniforms. “I don’t know, Charlie Brown”, reflects Linus. “Perhaps you should just leave town.”

The game goes amazingly well, and is low-scoring, with Snoopy bringing the team within one run of tying the score in the bottom of the ninth by stealing home. With two out, the batter is – Charlie. To his own amazement, he gets a hit – then foolishly tries to repeat Snoopy’s feat of stealing all the bases. He slides…and is called out, resting 30 feet from home plate. Lucy screams that if it wasn’t for those uniforms, they’d walk out right now. “There aren’t going to be any uniforms”, Charlie confesses, admitting he gave them up, but not stating why, feeling there is no hope of keeping the team together anyway. The usual screams, and the team abandons Charlie where he rests on the third base line. Linus follows the girls and Snoopy, who mutually exchange insults about Charlie and how he could do such a thing as give their uniforms away. Linus decides to speak up, informing them he did it so their feelings wouldn’t be hurt at being unable to join a real league. The girls and Snoopy feel awful, until they decide to do something nice for Charlie Brown – make a special manager’s uniform, just for him. Linus is skeptical that such an idea can be carried out, pointing out that the girls haven’t got any material. “Oh, yes we have”, says Lucy, snatching away Linus’s security blanket. By the next morning, Linus’ blanket has been transformed into a saggy, oversized blue outfit with letters sewn thereon reading “Our Manager”.

The game goes amazingly well, and is low-scoring, with Snoopy bringing the team within one run of tying the score in the bottom of the ninth by stealing home. With two out, the batter is – Charlie. To his own amazement, he gets a hit – then foolishly tries to repeat Snoopy’s feat of stealing all the bases. He slides…and is called out, resting 30 feet from home plate. Lucy screams that if it wasn’t for those uniforms, they’d walk out right now. “There aren’t going to be any uniforms”, Charlie confesses, admitting he gave them up, but not stating why, feeling there is no hope of keeping the team together anyway. The usual screams, and the team abandons Charlie where he rests on the third base line. Linus follows the girls and Snoopy, who mutually exchange insults about Charlie and how he could do such a thing as give their uniforms away. Linus decides to speak up, informing them he did it so their feelings wouldn’t be hurt at being unable to join a real league. The girls and Snoopy feel awful, until they decide to do something nice for Charlie Brown – make a special manager’s uniform, just for him. Linus is skeptical that such an idea can be carried out, pointing out that the girls haven’t got any material. “Oh, yes we have”, says Lucy, snatching away Linus’s security blanket. By the next morning, Linus’ blanket has been transformed into a saggy, oversized blue outfit with letters sewn thereon reading “Our Manager”.

However ill-fitting it may be, Charlie Brown thinks it’s beautiful. He inspires the team with a pep talk that, with their new found spirit, tomorrow’s game will be different. It is different, all right, as Lucy and Linus look out their window, at the heaviest downpour of rain they’ve seen in a long, long time. “Only a real blockhead would be out in a rain like this”, says Lucy. This prompts Linus’s curiosity, and he wades out to the baseball diamond in a raincoat, to find good ol’ Charlie Brown, in his full uniform, wondering how everyone else could have forgotten that they had a game today. As Snoopy sails by, skimming along the puddles on a surfboard, Linus just eyes Charlie Brown with an unusually forlorn interest, about which Charlie inquires. “They made your uniform out of my blanket!”, Linus wails. Charlie reflects on this, then quietly offers Linus one of the uniform’s overhanging sleeves to hold onto. Linus begins sucking his own thumb, and the two just stand there for the rest of the afternoon in the deluge.

Next time: A first plunge into the Disney Afternoon.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.