The 60’s and early 70’s were a highly inconsistent period for theatrical cartoons. Some studios had reached the stage of last gasps, while others had already folded. A few majors continued to hang on and insist on quality, though eventually their markets would dry up too, restricting the regularity of their productions and/or leading to their demise. For most, the road to survival became TV, though some studios would fail to make the move for several years, while others (such as Walter Lantz) would never successfully make the shift, and had to give up the ghost (no, not Casper). From these days, we survey some of the last storm stories to grace the big screen – some still impressive, a few rather dreadful. Disney, of course, continued to set the bar high, and produced during this period not only some memorable feature animation, but one of their most enduring franchises, that continues in lucrative style to this day. We’ll also see some better and some worse from the productions of Walter Lantz, some new blood at Terrytoons, work by Chuck Jones and DePatie-Freleng, and a fairly impressive solo effort by a producer generally only associated with television.

Ski-Napper (Lantz/Universal, Chilly Willy, November, 1964 – Sid Marcus, dir.) – Marcus, the last creative director in the Lantz roster, presents a fast-paced and well-timed portrait of the rigors of survival in the frozen terrain of the Swiss Alps. Chilly Willy, at home in any snowy locale, has taken up residence in a self-constructed igloo. He is sound asleep in bed, with a problem – it is so cold, every exhale of his snoring is condensing into about a dozen or so ice cubes, which are piling high upon his bed. The shutters on his window have blown open, and are clattering against the wall of the igloo. As we cut back to the bed, the ice pile has doubled, and now a nearly complete coat of frost covers Chilly’s pillow and head. It is all that Chilly can do to open an eyelid under the snowy covering to locate the source of the clattering noise. He rises to close the shutters, but in merely walking back a few steps into the room, has his head freeze in a block of ice. This is not a new experience to him, as he keeps a hammer handy at the ready atop a crate he uses as a table, allowing him to effortlessly reach out from where he stands to grab the hammer and smash the ice block apart. He settles back in bed, while the winds continue to blow fiercely outside. A strong gust slides the whole igloo to stage right, neatly shifting it so that only Chilly’s bed remains in place on the frozen ground, repositioned as if it had slid out the igloo doorway. Chilly awakens in surprise at the exterior cold, and rises to push his bed back into the house – but the wind repeats the same trick, and slides the Igloo another ten feet to the right. Chilly pushes the bed back in again, but this time grabs some wood and nails, and boards up his front door, so that the bed will stay inside even if the igloo moves. He hasn’t counted on the window on the opposite side, and the next gust blows Chilly and the bed out the window. A camera dissolve, and Chilly has somehow gotten the bed back inside, and is now hammering nails into the bedposts to fasten it firmly to the frozen ground.

Ski-Napper (Lantz/Universal, Chilly Willy, November, 1964 – Sid Marcus, dir.) – Marcus, the last creative director in the Lantz roster, presents a fast-paced and well-timed portrait of the rigors of survival in the frozen terrain of the Swiss Alps. Chilly Willy, at home in any snowy locale, has taken up residence in a self-constructed igloo. He is sound asleep in bed, with a problem – it is so cold, every exhale of his snoring is condensing into about a dozen or so ice cubes, which are piling high upon his bed. The shutters on his window have blown open, and are clattering against the wall of the igloo. As we cut back to the bed, the ice pile has doubled, and now a nearly complete coat of frost covers Chilly’s pillow and head. It is all that Chilly can do to open an eyelid under the snowy covering to locate the source of the clattering noise. He rises to close the shutters, but in merely walking back a few steps into the room, has his head freeze in a block of ice. This is not a new experience to him, as he keeps a hammer handy at the ready atop a crate he uses as a table, allowing him to effortlessly reach out from where he stands to grab the hammer and smash the ice block apart. He settles back in bed, while the winds continue to blow fiercely outside. A strong gust slides the whole igloo to stage right, neatly shifting it so that only Chilly’s bed remains in place on the frozen ground, repositioned as if it had slid out the igloo doorway. Chilly awakens in surprise at the exterior cold, and rises to push his bed back into the house – but the wind repeats the same trick, and slides the Igloo another ten feet to the right. Chilly pushes the bed back in again, but this time grabs some wood and nails, and boards up his front door, so that the bed will stay inside even if the igloo moves. He hasn’t counted on the window on the opposite side, and the next gust blows Chilly and the bed out the window. A camera dissolve, and Chilly has somehow gotten the bed back inside, and is now hammering nails into the bedposts to fasten it firmly to the frozen ground.

With his eyelids dark and heavy, Chilly walks over to a rounded block of ice on a chair, twisting an unseen object in its rear like a winding key, then cracks the ice block open with his trusty hammer, revealing it is his alarm clock. He then walks over to another huge block of ice in the room, gives another whack with his hammer, and reveals inside his iron stove. Chilly reaches for a coal pail leaning against the stove to start a fire, but finds his fuel supply totally depleted. Only one thing to do if he’s ever going to get some sleep – “borrow” some more from a local ski resort. There, Smedly toils at the insistence of the Swiss-accented manager, polishing skis in anticipation of the opening of the tourist season. Right under Smedly’s nose, Chilly enters, filling his coal pail from the hotel’s own, and attempts to exit. Smedly smoothly scoops Chilly up, turns him upside down, and empties the coal from his pail back into the hotel’s own. “Sorry, son. The boss frowns on coal-nappers”, says Smedly, placing Chilly inside his coal pail, and sliding him away down a hill like a toboggan ride. A few moments later, determined Chilly returns, forgetting about the coal pile, and instead sliding out of the hotel the entire pot-bellied stove. Smedly pursues all the way back to Chilly’s igloo, then pushes the stove all the way back uphill to the hotel lobby. Having no idea what a determined penguin will do next, Smedly vows to keep his eyes wide open – but of course falls instantly asleep. All that will wake him is the hotel manager placing the desk bell in Smedly’s mouth, then pounding on Smedly’s snout to ring it. Smedly quickly resumes his ski polishing, placing each finished ski in a leaning position near a window. One by one, the finished skis disappear out the window, lifted by a small black hand. Suddenly, a loud chopping noise is heard outside, as Smedly peers out to investigate. The ski-napper is of course Chilly, who has chopped each ski into multiple pieces, piling up the board fragments into his pail, as a neat supply of firewood. “Oh, no”, responds Smedly, and despite engaging in a brisk chase for the pail, can accomplish little, as the skis are already destroyed. Smedly is caught by the boss with the splintered ski supply, including one board wedged inside his mouth, causing the boss not only to fire Smedley, but chase him around the hills, tossing the fractured boards at Smedly’s head. Smedly finally takes refuge in Chilly’s igloo, while outside, Chilly gathers up all the scattered boards, then brings them into the igloo to stoke a fire. Smedly comfortably settles in bed beside the penguin, as Chilly’s guest for the winter, following the motto, “If you can’t lick ‘em, join ‘em.”

With his eyelids dark and heavy, Chilly walks over to a rounded block of ice on a chair, twisting an unseen object in its rear like a winding key, then cracks the ice block open with his trusty hammer, revealing it is his alarm clock. He then walks over to another huge block of ice in the room, gives another whack with his hammer, and reveals inside his iron stove. Chilly reaches for a coal pail leaning against the stove to start a fire, but finds his fuel supply totally depleted. Only one thing to do if he’s ever going to get some sleep – “borrow” some more from a local ski resort. There, Smedly toils at the insistence of the Swiss-accented manager, polishing skis in anticipation of the opening of the tourist season. Right under Smedly’s nose, Chilly enters, filling his coal pail from the hotel’s own, and attempts to exit. Smedly smoothly scoops Chilly up, turns him upside down, and empties the coal from his pail back into the hotel’s own. “Sorry, son. The boss frowns on coal-nappers”, says Smedly, placing Chilly inside his coal pail, and sliding him away down a hill like a toboggan ride. A few moments later, determined Chilly returns, forgetting about the coal pile, and instead sliding out of the hotel the entire pot-bellied stove. Smedly pursues all the way back to Chilly’s igloo, then pushes the stove all the way back uphill to the hotel lobby. Having no idea what a determined penguin will do next, Smedly vows to keep his eyes wide open – but of course falls instantly asleep. All that will wake him is the hotel manager placing the desk bell in Smedly’s mouth, then pounding on Smedly’s snout to ring it. Smedly quickly resumes his ski polishing, placing each finished ski in a leaning position near a window. One by one, the finished skis disappear out the window, lifted by a small black hand. Suddenly, a loud chopping noise is heard outside, as Smedly peers out to investigate. The ski-napper is of course Chilly, who has chopped each ski into multiple pieces, piling up the board fragments into his pail, as a neat supply of firewood. “Oh, no”, responds Smedly, and despite engaging in a brisk chase for the pail, can accomplish little, as the skis are already destroyed. Smedly is caught by the boss with the splintered ski supply, including one board wedged inside his mouth, causing the boss not only to fire Smedley, but chase him around the hills, tossing the fractured boards at Smedly’s head. Smedly finally takes refuge in Chilly’s igloo, while outside, Chilly gathers up all the scattered boards, then brings them into the igloo to stoke a fire. Smedly comfortably settles in bed beside the penguin, as Chilly’s guest for the winter, following the motto, “If you can’t lick ‘em, join ‘em.”

You can try to access the cartoon HERE.

Snowbody Loves Me (SIB Tower 12, Inc./MGM, Tom and Jerry, 5/17/64 – Chuck Jones, dir.) – A frosty, windy winter night in a Tyrolian land finds a lonely Jerry shivering with cold and trapesing across a snow-covered landscape. A gust of wind catches the mouse, propelling him forward into a roll in the snow, where he quickly grows into a giant snowball, and rolls down hilly slopes toward a small village in a valley below. The snowball crashes into a stone wall, and Jerry emerges, nearly as rigid as ice and barely able to walk. He finds himself before the entrance to a Swiss cheese shop, and looks through a frosty window pane after clearing away two spots on the glass for his eyes to view through. Inside, the window display and interior of the shop are lined with cheeses of all sizes and varieties, decorated with little Swiss doll figures in traditional mountaineer garb. A third patch of exterior frost is cleared from the window, exposing a view through the glass of Jerry’s ear-to-ear smile. With what little mobility he has left, Jerry vigorously thumps at the bolted front door of the shop. Inside, in an easy chair, rests Tom before a comfortable fire, his torso completely wrapped like a cocoon within a warm blanket. Hating to leave the comfort of his chair, Tom begrudgingly answers the door, failing to notice the tiny form of Jerry entering between his legs and waddling his way over to the fire. Tom steps outside, still trying to locate whoever knocked – and the wind slams the door of the shop behind him, locking Tom out. Startled Tom drops his blanket, and instantly feels the cold. He clenches his own body with both arms and legs, wraps his tail around himself, and shuts both ears from the icy wind – but still, icicles instantly form from his whiskers. He tries to pick up the blanket, but it has frozen stiff as a board, and will not wrap around him. Tom now peers in the window, spotting Jerry by the fire. As with Jerry before, Tom’s mouth forms a spot of visibility through the window frost – but the expression is in the form of a scowl. Tom scrambles up the rain gutters and walls of the shop, onto the roof, and down the chimney – unaware that inside, Jerry is just positioning a fireplace bellows to blow upon the hearth to increase the flame from the fireplace logs. “YEOW!” With a howl, Tom disappears back up the chimney, slides down the roof onto the storm drain, dislodges the drain pipe, and crashes into a large snowdrift below.

Snowbody Loves Me (SIB Tower 12, Inc./MGM, Tom and Jerry, 5/17/64 – Chuck Jones, dir.) – A frosty, windy winter night in a Tyrolian land finds a lonely Jerry shivering with cold and trapesing across a snow-covered landscape. A gust of wind catches the mouse, propelling him forward into a roll in the snow, where he quickly grows into a giant snowball, and rolls down hilly slopes toward a small village in a valley below. The snowball crashes into a stone wall, and Jerry emerges, nearly as rigid as ice and barely able to walk. He finds himself before the entrance to a Swiss cheese shop, and looks through a frosty window pane after clearing away two spots on the glass for his eyes to view through. Inside, the window display and interior of the shop are lined with cheeses of all sizes and varieties, decorated with little Swiss doll figures in traditional mountaineer garb. A third patch of exterior frost is cleared from the window, exposing a view through the glass of Jerry’s ear-to-ear smile. With what little mobility he has left, Jerry vigorously thumps at the bolted front door of the shop. Inside, in an easy chair, rests Tom before a comfortable fire, his torso completely wrapped like a cocoon within a warm blanket. Hating to leave the comfort of his chair, Tom begrudgingly answers the door, failing to notice the tiny form of Jerry entering between his legs and waddling his way over to the fire. Tom steps outside, still trying to locate whoever knocked – and the wind slams the door of the shop behind him, locking Tom out. Startled Tom drops his blanket, and instantly feels the cold. He clenches his own body with both arms and legs, wraps his tail around himself, and shuts both ears from the icy wind – but still, icicles instantly form from his whiskers. He tries to pick up the blanket, but it has frozen stiff as a board, and will not wrap around him. Tom now peers in the window, spotting Jerry by the fire. As with Jerry before, Tom’s mouth forms a spot of visibility through the window frost – but the expression is in the form of a scowl. Tom scrambles up the rain gutters and walls of the shop, onto the roof, and down the chimney – unaware that inside, Jerry is just positioning a fireplace bellows to blow upon the hearth to increase the flame from the fireplace logs. “YEOW!” With a howl, Tom disappears back up the chimney, slides down the roof onto the storm drain, dislodges the drain pipe, and crashes into a large snowdrift below.

As Tom regroups for another assault, rigging a fishing line and hook to slip through the uppermost crack of the front door to lift the door latch from the inside, Jerry surveys the shop from a high shelf, his eyes settling on a large wheel of Swiss cheese. Jerry performs a swan dive into one of the holes, disappearing from sight. As Tom enters the front door, with everuthing now frozen except his tail (by which he propels himself over to the fire to thaw), Jerry establishes a residence inside the cheese, biting cheese chunks until they resemble the shapes of furniture, and exploring a vast inner network of tunnels and caverns within the partially-hollow cheese’s walls. Jerry begins to yodel, and the echo of his voice reverberates throughout the length and breadth of the cheese’s corridors. The sound is heard by Tom, who peers into one of the holes. Tom decides to make his own use of the fireplace bellows, placing the air-tube thereof into one of the cheese holes, then pressing on the bellows. The force of air through the cheese caverns pops Jerry out one of the top holes of the cheese, and Tom makes a grab for him. But each time Tom grans, the air from the bellows gives out, and Jerry falls back inside the cheese just inches ahead of Tom’s paws. A better solution is needed, and Tom hits on the idea. From inside the cheese, Jerry observes the holes of the cheese being plugged one by one – with corks. One cork is inserted in a hole above Jerry’s head, driving his feet into the soft cheese he is standing upon, until Jerry is stuck waist-deep in the cheese. Once all the holes but one are plugged, Tom obtains a fireplace bellows twice the size of the original one, inserts its end into the last remaining hole, then rigs an anvil suspended from a rope looped over the top of a ceiling rafter just above it. Tom cuts the rope, and the anvil falls, compressing the bellows and focing a mass of air into the cheese, until it bulges like a balloon about to pop. The air pressure proves too great for the cheese to withstand, and the cheese explodes apart. Tom finds himself in a crossfire of corks popping from the holes of the exploded cheese, one of which catches him square in the jaws, driving him back against a wall. As the last corks cease to roll along the floor, Tom more closely examines the cheese, spotting Jerry, still alive, peering out from behind the fragments of a last-remaining wall of the cheese wheel. As Jerry steps forward, he reveals, both to us and to his own surprise, that the cheese he had been waist-deep within has left a remnant around his waist – which resembles for all the world a ballet tutu. Impulsively struck by the mood, Jerry begins to perform an elaborate impromptu ballet. His dancing is so well executed, even Tom’s anger temporarily falls away, and all that Tom can do is sit to enjoy the performance. As Jerry’s dance ends, with the mouse coyly assuming a sort of “dying swan” pose, Tom rises to applaud him – but pulls a fast one, completing his applause by bringing his paws quickly together, to slap Jerry nearly flat between them, leaving the mouse stunned and senseless. With a wicked laugh, Tom picks up the helpless mouse by the tail, and hurls him outside, deep into a mound of snow.

As Tom regroups for another assault, rigging a fishing line and hook to slip through the uppermost crack of the front door to lift the door latch from the inside, Jerry surveys the shop from a high shelf, his eyes settling on a large wheel of Swiss cheese. Jerry performs a swan dive into one of the holes, disappearing from sight. As Tom enters the front door, with everuthing now frozen except his tail (by which he propels himself over to the fire to thaw), Jerry establishes a residence inside the cheese, biting cheese chunks until they resemble the shapes of furniture, and exploring a vast inner network of tunnels and caverns within the partially-hollow cheese’s walls. Jerry begins to yodel, and the echo of his voice reverberates throughout the length and breadth of the cheese’s corridors. The sound is heard by Tom, who peers into one of the holes. Tom decides to make his own use of the fireplace bellows, placing the air-tube thereof into one of the cheese holes, then pressing on the bellows. The force of air through the cheese caverns pops Jerry out one of the top holes of the cheese, and Tom makes a grab for him. But each time Tom grans, the air from the bellows gives out, and Jerry falls back inside the cheese just inches ahead of Tom’s paws. A better solution is needed, and Tom hits on the idea. From inside the cheese, Jerry observes the holes of the cheese being plugged one by one – with corks. One cork is inserted in a hole above Jerry’s head, driving his feet into the soft cheese he is standing upon, until Jerry is stuck waist-deep in the cheese. Once all the holes but one are plugged, Tom obtains a fireplace bellows twice the size of the original one, inserts its end into the last remaining hole, then rigs an anvil suspended from a rope looped over the top of a ceiling rafter just above it. Tom cuts the rope, and the anvil falls, compressing the bellows and focing a mass of air into the cheese, until it bulges like a balloon about to pop. The air pressure proves too great for the cheese to withstand, and the cheese explodes apart. Tom finds himself in a crossfire of corks popping from the holes of the exploded cheese, one of which catches him square in the jaws, driving him back against a wall. As the last corks cease to roll along the floor, Tom more closely examines the cheese, spotting Jerry, still alive, peering out from behind the fragments of a last-remaining wall of the cheese wheel. As Jerry steps forward, he reveals, both to us and to his own surprise, that the cheese he had been waist-deep within has left a remnant around his waist – which resembles for all the world a ballet tutu. Impulsively struck by the mood, Jerry begins to perform an elaborate impromptu ballet. His dancing is so well executed, even Tom’s anger temporarily falls away, and all that Tom can do is sit to enjoy the performance. As Jerry’s dance ends, with the mouse coyly assuming a sort of “dying swan” pose, Tom rises to applaud him – but pulls a fast one, completing his applause by bringing his paws quickly together, to slap Jerry nearly flat between them, leaving the mouse stunned and senseless. With a wicked laugh, Tom picks up the helpless mouse by the tail, and hurls him outside, deep into a mound of snow.

In a sequence similar to the H-B classic, “The Night Before Christmas”, Tom returns to the comfort of the fire, the easy chair, and his now-thawed blanket. But imagination and conscience get the better of him, as he hears the icy winds outside, and suddenly envisions Jerry’s transparent soul rising into the heaves as an angel. Guilt-stricken, Tom dashes outside, grabbing the rigid, blue Jerry out of the snow by the tail, and carrying him back in. Instead of merely thawing Jerry at the fire as in the H-B original, Tom bundles Jerry in a warm towel, and pours into Jerry’s mouth a teaspoon or Eulenspiegel’s Schnapps – 180 proof. Jerry warms to a toasty red, then hiccups, launching him like a rocket to a shelf above, where stand several of the Swiss dolls, which Jerry knocks over. Jerry returns to view, dressed in the full Swiss mountaineer’s outfit of one of the dolls. Tom is so happy that Jerry is okay, he accepts Jerry as jis guest, and engages in some musical entertainment with Jerry much as in the concert sequence of “Johann Mouse”, playing piano accompaniment while Jerry performs a spirited Tyrolian dance atop the piano, for the iris out.

In a sequence similar to the H-B classic, “The Night Before Christmas”, Tom returns to the comfort of the fire, the easy chair, and his now-thawed blanket. But imagination and conscience get the better of him, as he hears the icy winds outside, and suddenly envisions Jerry’s transparent soul rising into the heaves as an angel. Guilt-stricken, Tom dashes outside, grabbing the rigid, blue Jerry out of the snow by the tail, and carrying him back in. Instead of merely thawing Jerry at the fire as in the H-B original, Tom bundles Jerry in a warm towel, and pours into Jerry’s mouth a teaspoon or Eulenspiegel’s Schnapps – 180 proof. Jerry warms to a toasty red, then hiccups, launching him like a rocket to a shelf above, where stand several of the Swiss dolls, which Jerry knocks over. Jerry returns to view, dressed in the full Swiss mountaineer’s outfit of one of the dolls. Tom is so happy that Jerry is okay, he accepts Jerry as jis guest, and engages in some musical entertainment with Jerry much as in the concert sequence of “Johann Mouse”, playing piano accompaniment while Jerry performs a spirited Tyrolian dance atop the piano, for the iris out.

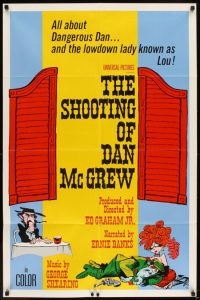

From 1965 (precise release date unknown) comes Ed Graham, Jr.’s theatrical short, The Shooting of Dan McGrew, deserving honorable mention for brief atmospheric blizzard conditions as are characteristic of the tale. This highly-stylized vision of the famous poem tells the entire tale rather straight, with authentic-sounding narration provided by Walter Brennan, and surprise voice part for the Stranger provided by Ernie Banks. Visuals are artsy and classy – a significant step up for a director only previously used to producing Saturday morning animation and cereal commercials with Linus the Lionhearted and his gang. Oddly, circulating print indicates distribution by Universal – raising the question whether Universal might have been potentially considering closing out the contract of its long-time provider Walter Lantz due to fall-off in quality of the product – or perhaps was thinking in terms of importing outside films potentially of quality to attract the attentions of the Oscar committee, much as Paramount had done with the Gene Deitch/William Snyder productions of Rembrandt Films or its contemporary Oscar win with a release from John Hubley. Whatever the case, the film is an interesting contrast to the gagged-up approaches to the story released by Warner, MGM, Paramount, and the like, and bears watching. The only comedy beat likely added by the producer is the touch that at the end, as the Stranger lays dying, the Lady known as Lou thinks nothing of picking the sack of gold from his pockets, and stuffing it down her dress for her own – leaving her as the only character enjoying a happy ending.

From 1965 (precise release date unknown) comes Ed Graham, Jr.’s theatrical short, The Shooting of Dan McGrew, deserving honorable mention for brief atmospheric blizzard conditions as are characteristic of the tale. This highly-stylized vision of the famous poem tells the entire tale rather straight, with authentic-sounding narration provided by Walter Brennan, and surprise voice part for the Stranger provided by Ernie Banks. Visuals are artsy and classy – a significant step up for a director only previously used to producing Saturday morning animation and cereal commercials with Linus the Lionhearted and his gang. Oddly, circulating print indicates distribution by Universal – raising the question whether Universal might have been potentially considering closing out the contract of its long-time provider Walter Lantz due to fall-off in quality of the product – or perhaps was thinking in terms of importing outside films potentially of quality to attract the attentions of the Oscar committee, much as Paramount had done with the Gene Deitch/William Snyder productions of Rembrandt Films or its contemporary Oscar win with a release from John Hubley. Whatever the case, the film is an interesting contrast to the gagged-up approaches to the story released by Warner, MGM, Paramount, and the like, and bears watching. The only comedy beat likely added by the producer is the touch that at the end, as the Stranger lays dying, the Lady known as Lou thinks nothing of picking the sack of gold from his pockets, and stuffing it down her dress for her own – leaving her as the only character enjoying a happy ending.

One of Disney’s most successful franchises began with Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree (2/6/66 – Wolfgang Reitherman, dir.). This first installment features no storms or unusual turns of weather, its only precipitation being a smattering of fallout of drops of mud, as Pooh seems to vie for the coveted toon title of “World’s Cheesiest Disguise”. Rolling in a large mud puddle until he is completely covered in the stuff, Pooh naturally assumes that the world will recognize him as a dead-ringer for a “little black rain cloud” – despite the fact that he is still entirely shaped like a bear. Oh, well, what can you expect from a bear of very little brain? Needless to say, the bees in the honey tree “s-u-s-p-e-c-t something”, as Pooh floats up to their treetop hive by holding onto a sky-blue balloon. Pooh manages to sneak a pawful of honey into his mouth, but fails to notice the honey is still swarming with bees, until the buzzing devils begin violently wriggling inside Pooh’s head stuffed with fluff. Pooh commences spitting out bees right and left – even mimicking the motions of shooting a machine gun while he spits – and knocks a few stray bugs out of his ears. One bee falls into the mud puddle, and gets riled, launching a sting right into the softest part of Pooh’s bottom. Pooh’s rear end swings from the balloon string like a pendulum, and ends up stuck in the hole of the hive. A build-up of bees swells the insides of the tree trunk behind Pooh, until the pent-up force explodes Pooh from the tree, also untying the string of the balloon. Pooh takes a wild ride atop the balloon through the skies, until the sphere runs out of air. Understating the obvious, Pooh remarks. “Oh, bother. I think I shall come down.” Christopher Robin breaks his fall, and the two only escape the bees by diving completely into the sticky mud, where Pooh spits out a final bee to close the sequence.

One of Disney’s most successful franchises began with Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree (2/6/66 – Wolfgang Reitherman, dir.). This first installment features no storms or unusual turns of weather, its only precipitation being a smattering of fallout of drops of mud, as Pooh seems to vie for the coveted toon title of “World’s Cheesiest Disguise”. Rolling in a large mud puddle until he is completely covered in the stuff, Pooh naturally assumes that the world will recognize him as a dead-ringer for a “little black rain cloud” – despite the fact that he is still entirely shaped like a bear. Oh, well, what can you expect from a bear of very little brain? Needless to say, the bees in the honey tree “s-u-s-p-e-c-t something”, as Pooh floats up to their treetop hive by holding onto a sky-blue balloon. Pooh manages to sneak a pawful of honey into his mouth, but fails to notice the honey is still swarming with bees, until the buzzing devils begin violently wriggling inside Pooh’s head stuffed with fluff. Pooh commences spitting out bees right and left – even mimicking the motions of shooting a machine gun while he spits – and knocks a few stray bugs out of his ears. One bee falls into the mud puddle, and gets riled, launching a sting right into the softest part of Pooh’s bottom. Pooh’s rear end swings from the balloon string like a pendulum, and ends up stuck in the hole of the hive. A build-up of bees swells the insides of the tree trunk behind Pooh, until the pent-up force explodes Pooh from the tree, also untying the string of the balloon. Pooh takes a wild ride atop the balloon through the skies, until the sphere runs out of air. Understating the obvious, Pooh remarks. “Oh, bother. I think I shall come down.” Christopher Robin breaks his fall, and the two only escape the bees by diving completely into the sticky mud, where Pooh spits out a final bee to close the sequence.

DePatie Freleng studio seems to have judiciously tried to avoid cartoons involving weather altogether, no doubt to save the budgets from costly special effects. It seems as though their only cartoon involving weather was the Pink Panther’s Pinknic (1/6/67 – Hawley Pratt, dir.), a virtual remake of Tweety and Sylvester’s “Snow Business” without substitute characters for Granny or Tweety. Instead, it concentrates on the starved, half-crazed mouse inside the snowbound cabin where Pinky is also trapped, ravenously attempting to make a seven-course dinner out of the panther. It adds a repeat of the closing eyelids POV of dozing off despite glimpses of approaching danger from “Greedy For Tweety”. A new ending has Pinky climb down a ladder into the cabin basement, and straight into a cooking pot atop a stove which the mouse has placed at the foot of the ladder. Turning on the gas, the mouse discovers he is out of matches to light the gas jet, so asks Pinky for a cigarette lighter. The flint stubbornly refuses to provide the necessary spark and flame. Pinky smells the gas, and climbs back up the ladder while the mouse is pre-occupied with the lighter. He looks out the window, to discover that spring thaw has finally arrived, and joyfully opens the front door. However, he finds himself face to face with the little big-nosed man of the series, who is the real owner of the cabin. Pinky is booted out, while the man takes over possession – just in time for the mouse to finally get the lighter to work. The cabin explodes, and the charred man and mouse first meet. Still hungry, the mouse begins chomping upon the man’s nose, sending him screaming in pain into the woods, while Pinky merely shrugs his shoulders to the audience as if to say, “Oh, well”, for the iris out.

DePatie Freleng studio seems to have judiciously tried to avoid cartoons involving weather altogether, no doubt to save the budgets from costly special effects. It seems as though their only cartoon involving weather was the Pink Panther’s Pinknic (1/6/67 – Hawley Pratt, dir.), a virtual remake of Tweety and Sylvester’s “Snow Business” without substitute characters for Granny or Tweety. Instead, it concentrates on the starved, half-crazed mouse inside the snowbound cabin where Pinky is also trapped, ravenously attempting to make a seven-course dinner out of the panther. It adds a repeat of the closing eyelids POV of dozing off despite glimpses of approaching danger from “Greedy For Tweety”. A new ending has Pinky climb down a ladder into the cabin basement, and straight into a cooking pot atop a stove which the mouse has placed at the foot of the ladder. Turning on the gas, the mouse discovers he is out of matches to light the gas jet, so asks Pinky for a cigarette lighter. The flint stubbornly refuses to provide the necessary spark and flame. Pinky smells the gas, and climbs back up the ladder while the mouse is pre-occupied with the lighter. He looks out the window, to discover that spring thaw has finally arrived, and joyfully opens the front door. However, he finds himself face to face with the little big-nosed man of the series, who is the real owner of the cabin. Pinky is booted out, while the man takes over possession – just in time for the mouse to finally get the lighter to work. The cabin explodes, and the charred man and mouse first meet. Still hungry, the mouse begins chomping upon the man’s nose, sending him screaming in pain into the woods, while Pinky merely shrugs his shoulders to the audience as if to say, “Oh, well”, for the iris out.

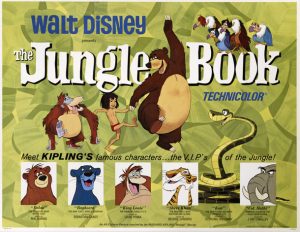

In The Jungle Book (Disney, 10/18/67), weather again sets the scene for turning the tide in a climactic battle between Mowgli and Shere Khan the tiger. Making good his threat to track down the man-cub in the jungle to see that he does not reach maturity, Khan prepares to pounce upon Mowgli, while Mowgli bravely but foolheartedly attempts to stand his ground, armed only with a stick. Only Baloo the bear prevents an early victory for Khan by literally grabbing “a tiger by the tail”, but then plays a dangerous game of trying to keep awat from the teeth on the other end. A quartet of vultures whom Mowgli has befriended (with intentional resemblance in voicings and hairdos to a certain fab four from Liverpool) grab hold of the boy and fly him to a safe distance from the tiger, but Mowgli realizes Baloo now needs help. At this crucial juncture, a lightning storm develops, allowing for some interesting visual punctuation as the frustrated Khan takes out his rage upon Baloo, slashing wildly with his claws as lightning seems to whiten the sky behind him to emphasize the power in every slash. One bolt stabs down to set a dead tree afire, and the vultures tip off Mowgli that fire is the only thing “old stripes” is afraid of. Mowgli grabs up the non-burning end of a fallen branch with several twigs lit ablaze like a torch, and carries it and a long vine to a point behind Khan. As Baloo falls, the vultures run interference with flying swoops in front of the tiger to distract him, while Mowgli uses the vine to tie the burning branch to Khan’s tail. “Look behind you, chum”, says one of the vultures, once Mowgli’s job is finished. The panicked tiger tries to bat at the flames with his paws, but only sizzles his own skin rather than smothering the fire. Khan can think of nothing else to do but rin, for heaven knows where, lighting up the jungle like a flaming comet passing through. As Khan disappears, hopefully never to be seen again, a gentle rain begins to fall, upon the seemingly lifeless body of Baloo. Tears are shed by Mowgli, and consoling Bagheera the panther presides over a funeral oration for the brave bear. No one notices Baloo wearily open his eyes, and begin taking in all the uncharacteristically-kind words Bagheera has to say about him. “Beautiful”, Baloo utters under his breath to himself, and further adds “He’s crackin’ me up.” When Bagheera runs out of speech, having proclaimed the place a hallowed spot in Baloo’s honor, he and Mowgli sadly turn to leave. Baloo finally breaks the mood entirely, rising to complain, “Hey, don’t stop now, Baggy, you’re doing great. There’s more, lots more!”

In The Jungle Book (Disney, 10/18/67), weather again sets the scene for turning the tide in a climactic battle between Mowgli and Shere Khan the tiger. Making good his threat to track down the man-cub in the jungle to see that he does not reach maturity, Khan prepares to pounce upon Mowgli, while Mowgli bravely but foolheartedly attempts to stand his ground, armed only with a stick. Only Baloo the bear prevents an early victory for Khan by literally grabbing “a tiger by the tail”, but then plays a dangerous game of trying to keep awat from the teeth on the other end. A quartet of vultures whom Mowgli has befriended (with intentional resemblance in voicings and hairdos to a certain fab four from Liverpool) grab hold of the boy and fly him to a safe distance from the tiger, but Mowgli realizes Baloo now needs help. At this crucial juncture, a lightning storm develops, allowing for some interesting visual punctuation as the frustrated Khan takes out his rage upon Baloo, slashing wildly with his claws as lightning seems to whiten the sky behind him to emphasize the power in every slash. One bolt stabs down to set a dead tree afire, and the vultures tip off Mowgli that fire is the only thing “old stripes” is afraid of. Mowgli grabs up the non-burning end of a fallen branch with several twigs lit ablaze like a torch, and carries it and a long vine to a point behind Khan. As Baloo falls, the vultures run interference with flying swoops in front of the tiger to distract him, while Mowgli uses the vine to tie the burning branch to Khan’s tail. “Look behind you, chum”, says one of the vultures, once Mowgli’s job is finished. The panicked tiger tries to bat at the flames with his paws, but only sizzles his own skin rather than smothering the fire. Khan can think of nothing else to do but rin, for heaven knows where, lighting up the jungle like a flaming comet passing through. As Khan disappears, hopefully never to be seen again, a gentle rain begins to fall, upon the seemingly lifeless body of Baloo. Tears are shed by Mowgli, and consoling Bagheera the panther presides over a funeral oration for the brave bear. No one notices Baloo wearily open his eyes, and begin taking in all the uncharacteristically-kind words Bagheera has to say about him. “Beautiful”, Baloo utters under his breath to himself, and further adds “He’s crackin’ me up.” When Bagheera runs out of speech, having proclaimed the place a hallowed spot in Baloo’s honor, he and Mowgli sadly turn to leave. Baloo finally breaks the mood entirely, rising to complain, “Hey, don’t stop now, Baggy, you’re doing great. There’s more, lots more!”

Rain Drain (Terrytoons/Fox, James Hound, 9/66 – Ralph Bakshi, dir.) – There are right ways and wrong ways to direct a cartoon. In the waning days of Terrytoons, Ralph Bakshi seemed to vacillate between the two. We’ll take an example of the wrong way first. The James Hound series, a typical spoof on the secret agent craze of the day, was loaded with budget-saving shortcuts to lighten the production load. Numerous scenes in each episode were set against the same stock backgrounds, and duplicated the same poses from previous episodes – especially a tendency to pose Hound’s vocal lines in an identical facial close-up where the only action would be stylistically-stilted movement of the lips, and a signature wriggle of the eyebrows that Ralph might have picked up from the limited motion of characters in Colonel Bleep. Once these pieces were set, things got occasionally worse, as entire shots would be merely spliced in from preceding pictures, only altering the soundtrack. This habit led to recurrences of one of the most embarrassing giveaways of such “cheating”, as Hound, who was prone to repeatedly responding “Right, Chief”, would appear in reused shots timed for the dialogue of another cartoon, and literally step on the new lines of the Chief with his stock response before Dayton Allen in the new voice session could even finish the sentences of the Chief’s orders! They couldn’t even take the time to have Allen do a second take to speed up his read to synchronize with the stock shot! You’ll see this occur within this cartoon, as well as see several of the standard shots which, if you’ve seen other installments in the series, you’ll be overly familiar with.

Rain Drain (Terrytoons/Fox, James Hound, 9/66 – Ralph Bakshi, dir.) – There are right ways and wrong ways to direct a cartoon. In the waning days of Terrytoons, Ralph Bakshi seemed to vacillate between the two. We’ll take an example of the wrong way first. The James Hound series, a typical spoof on the secret agent craze of the day, was loaded with budget-saving shortcuts to lighten the production load. Numerous scenes in each episode were set against the same stock backgrounds, and duplicated the same poses from previous episodes – especially a tendency to pose Hound’s vocal lines in an identical facial close-up where the only action would be stylistically-stilted movement of the lips, and a signature wriggle of the eyebrows that Ralph might have picked up from the limited motion of characters in Colonel Bleep. Once these pieces were set, things got occasionally worse, as entire shots would be merely spliced in from preceding pictures, only altering the soundtrack. This habit led to recurrences of one of the most embarrassing giveaways of such “cheating”, as Hound, who was prone to repeatedly responding “Right, Chief”, would appear in reused shots timed for the dialogue of another cartoon, and literally step on the new lines of the Chief with his stock response before Dayton Allen in the new voice session could even finish the sentences of the Chief’s orders! They couldn’t even take the time to have Allen do a second take to speed up his read to synchronize with the stock shot! You’ll see this occur within this cartoon, as well as see several of the standard shots which, if you’ve seen other installments in the series, you’ll be overly familiar with.

Professor Mad, standard evil genius, was more times than not the recurring villain of the series. His assistant was an Igor-type hunchback with bolts in his neck. In this episode, the assistant opens the film, flying a specially-equipped blimp. He reports by radio to Professor Mad that he has captured another group of clouds, and is about to empty the reservoir. Mad, seen riding a camel in the desert, gives the order to proceed. Behind the blimp, in the grip of a tractor beam, three clouds follow the blimp at close range, appearing to gallop through the skies as if magnetized to the beam. At the pull up a lever, the clouds operate in reverse, sucking up all water below them, then follow the blimp wherever it leads them. When the blimp reaches the desert, Mad order the assistant to “pour it on”. At the pull of another lever, the clouds let go their cargo of water, drenching the desert sand with a strong downpour. Instantly, jungle-style greenery sprouts from everywhere around Mad, creating from the burning sands an instant rain forest. Mad informs the audience that he bought up this desert land cheap, and now, by cornering the market on water and guaranteeing rainfall to the property, he will resell it at exorbitant profit and become the richest man in thr world.

Professor Mad, standard evil genius, was more times than not the recurring villain of the series. His assistant was an Igor-type hunchback with bolts in his neck. In this episode, the assistant opens the film, flying a specially-equipped blimp. He reports by radio to Professor Mad that he has captured another group of clouds, and is about to empty the reservoir. Mad, seen riding a camel in the desert, gives the order to proceed. Behind the blimp, in the grip of a tractor beam, three clouds follow the blimp at close range, appearing to gallop through the skies as if magnetized to the beam. At the pull up a lever, the clouds operate in reverse, sucking up all water below them, then follow the blimp wherever it leads them. When the blimp reaches the desert, Mad order the assistant to “pour it on”. At the pull of another lever, the clouds let go their cargo of water, drenching the desert sand with a strong downpour. Instantly, jungle-style greenery sprouts from everywhere around Mad, creating from the burning sands an instant rain forest. Mad informs the audience that he bought up this desert land cheap, and now, by cornering the market on water and guaranteeing rainfall to the property, he will resell it at exorbitant profit and become the richest man in thr world.

Hound is feeling the effects of Mad’s work, as a news bulletin announces that there has been no rain now for 6 months. A small leak in a pipe is occasion for Hound to set up a shower curtain under the drips and attempt to take a shower. But the TV announcer reports that water conservation is no longer necessary – as the city reservoir is already completely empty. As a call comes in from the Chief, Hound reports to headquarters inside his shower curtain, some of the soap suds still clinging to his outfit. He is informed that Mad appears to be using a cloud inverter device, and sets off in pursuit of Mad from the runway of the nearest airport, using rocket jets built into the sleeves of his trenchcoat to take off like a private plane. Hound stops once out of town, hovering in the sky, and produces an aerosol can, spraying a smoke screen around himself resembling a cloud – then lies in wait for something to happen. Sure enough, Mad’s assistant takes, the bait, though thinking it odd to find a cloud wearing a hat visible on top. Hound is sucked along in the tractor beam, and tipped upside down to absorb another reservoir into his cloudy screen. However, once over the desert, another emptying out of the rain reveals Hound inside the fake cloud, who falls to the ground, getting caught within the spokes of Mad’s inverted umbrella like a miniature jail cell. Mad shows off his handiwork in the form of a large reservoir where he has been collecting the stolen water – then attempts to do Hound in with the sharp tip of the detachable cane of his umbrella. But Hound dodges the thrust, then dives into the reservoir, producing instant scuba gear to stay underwater. Mad instructs his assistant to aim the clouds at the reservoir, sucking up the water temporarily to reveal Hound high and dry upon the bed of the reservoir. Mad declares Houd to be finished – but Hound has another trick up his sleeve. He produces a glass of water – enough that the cloud machine sucks him up by the water glass into the air. Hound leaps into the gondola of the blimp, ordering Mad’s assistant to return the clouds to where they came from. “Clever, but not clever enough”, shouts Mad, attacking the blimp in a fighter jet. After several unsuccessful passes by the jet in attempt to target Hound in its sights, Hound decides action must be taken before Mad tries again. He takes a random pound upon the buttons of the control panel within the blimp. The result is another reversal of behavior of the clouds, who gallop out of the grip of the tractor beam, and run at full speed toward Mad’s plane as a cloud stampede. They hit Mad’s plane, enveloping it in lightning bolts of great immensity. The plane falls out through the bottom of the clouds, a charred wreck. Mad also falls, his shirt blossoming out to serve as a built-in parachute, as Mad defiantly shouts, “Till we meet again, Hound.” And of course, they do, as in the next episode below.

The Heat’s Off (James Hound, 4/67 – Ralph Bakshi, dir.) – On the other end of the extremes, Bakshi seems to do very little shortcutting in this one, and provides some new views of Hound’s apartment life and of a freezing Chief’s headquarters, making this episode feel more fresh and fun. James awakens in his apartment, bundled up under blankets, as icy breezes waft a coating of snow through the window several feet into the apartment floor, and the apartment radiator is covered in icicles. James telephones his building superintendent for heat, but is informed of an odd fact – the calendar reads July 4th, and the heating isn’t scheduled to be made operational until winter. He attempts to run hot bath water, but when he returns to the tub, finds it frozen over like an icy pond. James makes the most of it, considering it a new attraction of his luxury apartment – a personal ice-skating rink. A call on James’s hat phone from the Chief startles him while performing a figure-8, and he falls through the ice into the freezing tub. He reports at the Chief’s command to headquarters, making the trip by way of his sleeve rockets again. On his way in, he passes the Chief’s secretary Miss Q, who is also trembling with cold. The same conditions are found in the Chief’s private office, where the Chief asks Hound to turn his rocket jets in his direction so he can get a little heat. The Chief reveals that the strange weather problems are worldwide, showing him images on the TV screen of icebergs blocking New York harbor, a heat wave at the North Pole causing Eskimos to use electric fans and eat ice cream cones, and, worst of all, the top of Old Smokey is no longer covered with snow. Reconnaissance reveals that the suspect is, as usual, Professor Mad, who is believed to have come up with a way to alter the Gulf Stream current to change climate conditions. Hound rockets through the Chief’s ceiling to search out the villain, allowing a large pile of snow to fall through the roof hole, covering the Chief completely.

The Heat’s Off (James Hound, 4/67 – Ralph Bakshi, dir.) – On the other end of the extremes, Bakshi seems to do very little shortcutting in this one, and provides some new views of Hound’s apartment life and of a freezing Chief’s headquarters, making this episode feel more fresh and fun. James awakens in his apartment, bundled up under blankets, as icy breezes waft a coating of snow through the window several feet into the apartment floor, and the apartment radiator is covered in icicles. James telephones his building superintendent for heat, but is informed of an odd fact – the calendar reads July 4th, and the heating isn’t scheduled to be made operational until winter. He attempts to run hot bath water, but when he returns to the tub, finds it frozen over like an icy pond. James makes the most of it, considering it a new attraction of his luxury apartment – a personal ice-skating rink. A call on James’s hat phone from the Chief startles him while performing a figure-8, and he falls through the ice into the freezing tub. He reports at the Chief’s command to headquarters, making the trip by way of his sleeve rockets again. On his way in, he passes the Chief’s secretary Miss Q, who is also trembling with cold. The same conditions are found in the Chief’s private office, where the Chief asks Hound to turn his rocket jets in his direction so he can get a little heat. The Chief reveals that the strange weather problems are worldwide, showing him images on the TV screen of icebergs blocking New York harbor, a heat wave at the North Pole causing Eskimos to use electric fans and eat ice cream cones, and, worst of all, the top of Old Smokey is no longer covered with snow. Reconnaissance reveals that the suspect is, as usual, Professor Mad, who is believed to have come up with a way to alter the Gulf Stream current to change climate conditions. Hound rockets through the Chief’s ceiling to search out the villain, allowing a large pile of snow to fall through the roof hole, covering the Chief completely.

Below a floating mine in the ocean with a protruding sign reading “Keep Away”, Professor Mad conceals a submarine, equipped with a large electric fan atop its conning tower, serving as a propeller to blow the ocean currents in the opposite direction. Mad plans to demand a billion clams ransom to get that old miserable weather back where it belongs. Above, Hound flies, a long scarf trailing from his neck, bucking the wind of a snowy blizzard, when he suddenly encounters the edge of a storm front, abruptly changing the climate to brilliant sunshine. Hound decides to drop down to see what’s causing this odd phenomenon, and dives into the water with his scuba gear, spotting the submarine and fan below. He peers in a porthole, spotting Mad and his Igor henchman, who also spot him. “That big-mouthed bass is none other than secret agent James Hound”, says Mad, ordering his assistant to release their “official handshaker”. Out of a hatch reach one tentacled arm after another, until a giant squid leaps out, pouncing upon Hound. James engages in a fierce battle, seeming to lose round after round, but somehow gets the squid’s arms knotted together, placing the creature under arrest for obstructing justice. Mad orders the fan to be switched into reverse, and James finds himself being sucked toward its blades, with no visible means of escape. However, James’s long scarf is the first to be sucked into the blades – and winds around the fan’s axle, stopping the blades’ rotation before Hound can be sliced and diced. The freeze-up of the motor short-circuits the sub’s engines, causing the sub to explode. Mad and his henchman live to fight another day, making an escape riding atop a torpedo. Hound returns victoriously to the Chief’s office, where the weather is now back to a normal sweltering July day. Hound brings along a momento of the case for the Chief – the rescued giant fan, which he turns on facing the Chief straight in the face. The Chief’s muffled voice is heard in complaint, as all the papers from his desk blow right in his face, cutting off his air flow, and his wastebasket slams directly into his nose, while a puzzled Hound looks on for the fade out.

Below a floating mine in the ocean with a protruding sign reading “Keep Away”, Professor Mad conceals a submarine, equipped with a large electric fan atop its conning tower, serving as a propeller to blow the ocean currents in the opposite direction. Mad plans to demand a billion clams ransom to get that old miserable weather back where it belongs. Above, Hound flies, a long scarf trailing from his neck, bucking the wind of a snowy blizzard, when he suddenly encounters the edge of a storm front, abruptly changing the climate to brilliant sunshine. Hound decides to drop down to see what’s causing this odd phenomenon, and dives into the water with his scuba gear, spotting the submarine and fan below. He peers in a porthole, spotting Mad and his Igor henchman, who also spot him. “That big-mouthed bass is none other than secret agent James Hound”, says Mad, ordering his assistant to release their “official handshaker”. Out of a hatch reach one tentacled arm after another, until a giant squid leaps out, pouncing upon Hound. James engages in a fierce battle, seeming to lose round after round, but somehow gets the squid’s arms knotted together, placing the creature under arrest for obstructing justice. Mad orders the fan to be switched into reverse, and James finds himself being sucked toward its blades, with no visible means of escape. However, James’s long scarf is the first to be sucked into the blades – and winds around the fan’s axle, stopping the blades’ rotation before Hound can be sliced and diced. The freeze-up of the motor short-circuits the sub’s engines, causing the sub to explode. Mad and his henchman live to fight another day, making an escape riding atop a torpedo. Hound returns victoriously to the Chief’s office, where the weather is now back to a normal sweltering July day. Hound brings along a momento of the case for the Chief – the rescued giant fan, which he turns on facing the Chief straight in the face. The Chief’s muffled voice is heard in complaint, as all the papers from his desk blow right in his face, cutting off his air flow, and his wastebasket slams directly into his nose, while a puzzled Hound looks on for the fade out.

Much, I am sure, to the consternation of our website’s curator, who recently classified this entire series as among cartoons most qualified to be forgotten, we must make brief reference to two installments of Walter Lantz’s “The Beary Family Album” series, both directed by the well over-the-hill Paul J. Smith, who was the only director left in Lantz’s employ. Charlie the Rainmaker (1971, release date unknown) features no actual precipitation. Instead, it showcases predictable hijinks when Charlie, tired of the chore of watering the lawn, decides to install a lawn sprinkling system himself to save the $300 installation charge. A lot of windows get broken by flying pipes, and Bessie delivers a lot of frying pan whacks to Charlie’s head. When the system is finally in, the water is not – as Charlie has forgotten to pay the water bill. Bessie leaves him outside until he drums up some rain by means of an Indian rain dance – which dance lasts far into the night, with no results for moisture except the tears of a weeping Charlie. (Note: This is the only installment of the series in which Charlie wears a medium blue shirt instead of a yellow one. Lantz was known around this time for substituting awful paler colors when the price of the brighter paint shades increased at Cartoon Color Company. Was the price of golden yellow at a premium for only the duration of time that this one title was in production? Perhaps Lantz should have gone one better, and saved more money by converting the fur color of the Bearys to a neutral gray.)

Much, I am sure, to the consternation of our website’s curator, who recently classified this entire series as among cartoons most qualified to be forgotten, we must make brief reference to two installments of Walter Lantz’s “The Beary Family Album” series, both directed by the well over-the-hill Paul J. Smith, who was the only director left in Lantz’s employ. Charlie the Rainmaker (1971, release date unknown) features no actual precipitation. Instead, it showcases predictable hijinks when Charlie, tired of the chore of watering the lawn, decides to install a lawn sprinkling system himself to save the $300 installation charge. A lot of windows get broken by flying pipes, and Bessie delivers a lot of frying pan whacks to Charlie’s head. When the system is finally in, the water is not – as Charlie has forgotten to pay the water bill. Bessie leaves him outside until he drums up some rain by means of an Indian rain dance – which dance lasts far into the night, with no results for moisture except the tears of a weeping Charlie. (Note: This is the only installment of the series in which Charlie wears a medium blue shirt instead of a yellow one. Lantz was known around this time for substituting awful paler colors when the price of the brighter paint shades increased at Cartoon Color Company. Was the price of golden yellow at a premium for only the duration of time that this one title was in production? Perhaps Lantz should have gone one better, and saved more money by converting the fur color of the Bearys to a neutral gray.)

Rain, Rain, Go Away (1972, release date unknown) is a little different than usual, without Charlie fixing or installing anything. However, veteran writer Cal Howard is far from at the top of his game, and leaves a gaping plot hole/inconsistency painfully obvious in the presentation. As if lifted from “Donald’s Off Day”, Howard has Charlie readying himself for a day on the golf links, but – same old problem – every time he wants to golf, it rains. One step out the door, and he is not only drenched, but on cue struck by lightning. Grumbling Charlie kicks away his matched set of clubs (stubbing his toe), then tries to occupy himself by sitting down in front of the TV set. But lo, the set won’t turn on. Charlie asks Bessie what he’s supposed to do with himself, and Bessie, sensing trouble, recommends that whatever he wants to do – don’t do it. Junior won’t play Parcheesi with him – too busy in his room playing with a yo-yo. Charlie spends the film puttering around his trophy shelf (consisting of one loving cup about an inch tall), the attic, and the hall closet, revisiting old memories of Charleston competions, raccoon coats, ukeleles, and nights at the bowling alley – all of which either tire him out in trying to recreate his past prowess, or lead to predictable household disasters (such as a bowling ball getting loose and smashing through the window of the washing machine), and Bessie’s ever-present frying pan. Then, without explanation, Charlie sits down at the TV set once again, despite having already established at the beginning of the film that he knows the set isn’t working. Again, as if it was his first time, Charlie can’t get a picture – but Bessie now reveals that she unplugged the set when she was doing her vacuuming – something she could have said at the beginning of the picture, and saved all the trouble. Charlie finally settles don to watch a ball game – but by now, the rain outside has increased, and is leaking through every hole in the roof Charlie has never gotten around to fixing – even upon Charlie’s easy chair. Charlie fills the house with pots and pans to catch the drips, and returns once again to his ball game, only to have lightning strike the TV aerial, and short out the set, leaving Charlie weeping as usual.

Rain, Rain, Go Away (1972, release date unknown) is a little different than usual, without Charlie fixing or installing anything. However, veteran writer Cal Howard is far from at the top of his game, and leaves a gaping plot hole/inconsistency painfully obvious in the presentation. As if lifted from “Donald’s Off Day”, Howard has Charlie readying himself for a day on the golf links, but – same old problem – every time he wants to golf, it rains. One step out the door, and he is not only drenched, but on cue struck by lightning. Grumbling Charlie kicks away his matched set of clubs (stubbing his toe), then tries to occupy himself by sitting down in front of the TV set. But lo, the set won’t turn on. Charlie asks Bessie what he’s supposed to do with himself, and Bessie, sensing trouble, recommends that whatever he wants to do – don’t do it. Junior won’t play Parcheesi with him – too busy in his room playing with a yo-yo. Charlie spends the film puttering around his trophy shelf (consisting of one loving cup about an inch tall), the attic, and the hall closet, revisiting old memories of Charleston competions, raccoon coats, ukeleles, and nights at the bowling alley – all of which either tire him out in trying to recreate his past prowess, or lead to predictable household disasters (such as a bowling ball getting loose and smashing through the window of the washing machine), and Bessie’s ever-present frying pan. Then, without explanation, Charlie sits down at the TV set once again, despite having already established at the beginning of the film that he knows the set isn’t working. Again, as if it was his first time, Charlie can’t get a picture – but Bessie now reveals that she unplugged the set when she was doing her vacuuming – something she could have said at the beginning of the picture, and saved all the trouble. Charlie finally settles don to watch a ball game – but by now, the rain outside has increased, and is leaking through every hole in the roof Charlie has never gotten around to fixing – even upon Charlie’s easy chair. Charlie fills the house with pots and pans to catch the drips, and returns once again to his ball game, only to have lightning strike the TV aerial, and short out the set, leaving Charlie weeping as usual.

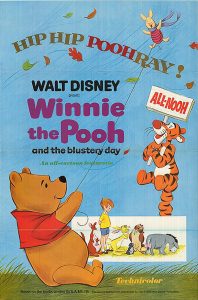

Juggling the order of our reviews, just so we end on a high note, we’ll close this chapter with the Oscar-winning Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day (12/20/68 – Wolfgang Reitherman, dir.) – In this episode, we are introduced to two characters omitted from the first short – Tigger, and, most notably, Piglet. Piglet plays the important roles with regard to the unusual atmospheric conditions leading Gopher to identify this date as a “Windsday”. As Pooh sets out to wish Piglet a happy Windsday, Piglet is having trouble clearing falling leaves from in front of his beech tree home. Being a very small animal, Piglet finds himself blown about by the increasing wind, running forward but progressing backward. As he passes Pooh, Pooh inquires where he is going. “That’s what I’m asking myself, where?”, Piglet replies. “And what do you think you will answer yourself?”, queries Pooh. The wind provides the answer, lifting Piglet into the sky, with Pooh grabbing onto the unraveling end of Piglet’s scarf (much as Mickey Mouse previously did with Donald Duck in “On Ice”) and flying Piglet like a kite. A stronger gust lifts Pooh off the ground as well, soaring both of them to their final destination – the window panes of Owl’s treehouse abode. Having guests arrive in such unusual fashion seems to come as no shock to dignified Owl, who calmly remarks, “Someone has pasted Piglet on my window.” Opening the window glass, Owl allows the wind to do the honors of inviting his guests inside. Classifying the gale-force storm as merely a “gentle spring zephyr”, Owl does his best to be sociable, inviting Pooh and Piglet to partake of honey from a pot. However, the pot proves elusive, as the tree itself begins to tip violently from side to side, repeatedly sliding the table on which the honey rests just out of Pooh’s reach. Piglet slides below the table on a stool, out the front door, and almost to the end of one of the tree’s branches, before the tree tips back the other way. Re-entering the house on the descending slope, Piglet winds up with the honey jar in his hands, and slams it right onto the end of Pooh’s snout. The bear is just happy he’s finally reached the food, and from inside the jar is heard to politely say “Thank you, Piglet.” At last, the tree can’t stand more strain, gives way at the roots, and collapses, wrecking Owl’s home. Surveying the damage, Eeyore observes, “When a house looks like that, it’s time to find another one.” Eeyore, in his usual deadpan manner, volunteers to scout around for a new home for Owl.

Juggling the order of our reviews, just so we end on a high note, we’ll close this chapter with the Oscar-winning Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day (12/20/68 – Wolfgang Reitherman, dir.) – In this episode, we are introduced to two characters omitted from the first short – Tigger, and, most notably, Piglet. Piglet plays the important roles with regard to the unusual atmospheric conditions leading Gopher to identify this date as a “Windsday”. As Pooh sets out to wish Piglet a happy Windsday, Piglet is having trouble clearing falling leaves from in front of his beech tree home. Being a very small animal, Piglet finds himself blown about by the increasing wind, running forward but progressing backward. As he passes Pooh, Pooh inquires where he is going. “That’s what I’m asking myself, where?”, Piglet replies. “And what do you think you will answer yourself?”, queries Pooh. The wind provides the answer, lifting Piglet into the sky, with Pooh grabbing onto the unraveling end of Piglet’s scarf (much as Mickey Mouse previously did with Donald Duck in “On Ice”) and flying Piglet like a kite. A stronger gust lifts Pooh off the ground as well, soaring both of them to their final destination – the window panes of Owl’s treehouse abode. Having guests arrive in such unusual fashion seems to come as no shock to dignified Owl, who calmly remarks, “Someone has pasted Piglet on my window.” Opening the window glass, Owl allows the wind to do the honors of inviting his guests inside. Classifying the gale-force storm as merely a “gentle spring zephyr”, Owl does his best to be sociable, inviting Pooh and Piglet to partake of honey from a pot. However, the pot proves elusive, as the tree itself begins to tip violently from side to side, repeatedly sliding the table on which the honey rests just out of Pooh’s reach. Piglet slides below the table on a stool, out the front door, and almost to the end of one of the tree’s branches, before the tree tips back the other way. Re-entering the house on the descending slope, Piglet winds up with the honey jar in his hands, and slams it right onto the end of Pooh’s snout. The bear is just happy he’s finally reached the food, and from inside the jar is heard to politely say “Thank you, Piglet.” At last, the tree can’t stand more strain, gives way at the roots, and collapses, wrecking Owl’s home. Surveying the damage, Eeyore observes, “When a house looks like that, it’s time to find another one.” Eeyore, in his usual deadpan manner, volunteers to scout around for a new home for Owl.

A blustery night turns into a rainy night. Pooh awakens from a creative dream sequence reminiscent of Dumbo’s “Pink Elephants” involving Heffalumps and Woozles (elephants and weasels) trying to steal his honey, to find the inside of his home flooded in about a foot of water. Speaking to his own reflection in a mirror as if a personal companion, Pooh asks, “Is it raining in there? It’s raining out here, too.” In fact, the entire Hundred Acre Wood is enduring the deluge, as water overflowing from an illustration in the book washes the printed letters off the page below. An expository song, “The Rain Rain Rain Came Down Down Down” shows a similar situation inside Piglet’s house. Trying to escape the flood waters, Piglet ducks under the covers of his bed – only, the bed is underwater too, so this accomplishes little relief. Piglet floats upon a chair over to a writing desk, penning a sort of S.O.S. message, reading “Help. P-P-Piglet (Me).” He places it in a botte and tosses it out a window. Piglet then uses a ladle to start bailing water into pots and pans – which only sinks the floating receptacles below the water. Before long, Piglet’s chair floats out the door, where he joins the flow of the rising waters. Our scene returns to Pooh, who has climbed to one of the highest branches of his tree home, where he has placed ten rescued honey pots. Unfortunately, as he tries to “sop up his supper” from one large pot, he winds up stuck inside it headfirst, upside down, as the pot topples from the tree and also floats along in the flood’s rising current.

A blustery night turns into a rainy night. Pooh awakens from a creative dream sequence reminiscent of Dumbo’s “Pink Elephants” involving Heffalumps and Woozles (elephants and weasels) trying to steal his honey, to find the inside of his home flooded in about a foot of water. Speaking to his own reflection in a mirror as if a personal companion, Pooh asks, “Is it raining in there? It’s raining out here, too.” In fact, the entire Hundred Acre Wood is enduring the deluge, as water overflowing from an illustration in the book washes the printed letters off the page below. An expository song, “The Rain Rain Rain Came Down Down Down” shows a similar situation inside Piglet’s house. Trying to escape the flood waters, Piglet ducks under the covers of his bed – only, the bed is underwater too, so this accomplishes little relief. Piglet floats upon a chair over to a writing desk, penning a sort of S.O.S. message, reading “Help. P-P-Piglet (Me).” He places it in a botte and tosses it out a window. Piglet then uses a ladle to start bailing water into pots and pans – which only sinks the floating receptacles below the water. Before long, Piglet’s chair floats out the door, where he joins the flow of the rising waters. Our scene returns to Pooh, who has climbed to one of the highest branches of his tree home, where he has placed ten rescued honey pots. Unfortunately, as he tries to “sop up his supper” from one large pot, he winds up stuck inside it headfirst, upside down, as the pot topples from the tree and also floats along in the flood’s rising current.

Christopher Robin and Roo, on the high ground of Christopher Robin’s house, discover Piglet’s floating bottle and the enclosed message. Owl is sent out to attempt to locate Piglet from the sky, while Christopher and the others try to think of a way to make a rescue. Owl spots Piglet and the inverted Pooh floating closely together, and tells them to be brave until a rescue is thought of. Bravery may not be the proper reaction at this time – as Pooh and Piglet are headed straight for a waterfall. As they both go over the falls, some tree branches protruding from the cliffside below the falls interfere with their descent, flipping the two off their respective mounts, so that Pooh winds up unstuck from the honey jar, safely floating on Piglet’s chair, while Piglet lands inside the honey pot, sailing like a miniature boat. They float up to the shoreline at Christopher Robin’s house, and everyone jumps to the conclusion that Pooh has somehow rescued Piglet, declaring him a hero. When the storm clears, a “hero party” is thrown for Pooh, but is interrupted by Eeyore, who raises everyone’s hopes with the news that he has found a new home for Owl. Everyone proceeds to the site of Eeyore’s find – but the domicile is all too familiar to everyone but Eeyore and Owl – Piglet’s house. Those in the know hate to burst the donkey’s and owl’s bubble, and hesitate to tell them of the mistake. Sentimental Piglet, however, just doesn’t have the heart to see Owl’s happiness dashed, and declares the home “the best house in the whole world” – and the property of Owl. The kindly porker makes the sacrifice without having any idea where he will live himself – but Pooh comes to his rescue, and volunteers that Piglet come to live with him. Pooh further suggests to Christopher Robin, “Can you make a one-hero party into a two-hero party?” – and so they can, as Piglet becomes second guest of honor for the festivities, which close out the film as the book closes.

Christopher Robin and Roo, on the high ground of Christopher Robin’s house, discover Piglet’s floating bottle and the enclosed message. Owl is sent out to attempt to locate Piglet from the sky, while Christopher and the others try to think of a way to make a rescue. Owl spots Piglet and the inverted Pooh floating closely together, and tells them to be brave until a rescue is thought of. Bravery may not be the proper reaction at this time – as Pooh and Piglet are headed straight for a waterfall. As they both go over the falls, some tree branches protruding from the cliffside below the falls interfere with their descent, flipping the two off their respective mounts, so that Pooh winds up unstuck from the honey jar, safely floating on Piglet’s chair, while Piglet lands inside the honey pot, sailing like a miniature boat. They float up to the shoreline at Christopher Robin’s house, and everyone jumps to the conclusion that Pooh has somehow rescued Piglet, declaring him a hero. When the storm clears, a “hero party” is thrown for Pooh, but is interrupted by Eeyore, who raises everyone’s hopes with the news that he has found a new home for Owl. Everyone proceeds to the site of Eeyore’s find – but the domicile is all too familiar to everyone but Eeyore and Owl – Piglet’s house. Those in the know hate to burst the donkey’s and owl’s bubble, and hesitate to tell them of the mistake. Sentimental Piglet, however, just doesn’t have the heart to see Owl’s happiness dashed, and declares the home “the best house in the whole world” – and the property of Owl. The kindly porker makes the sacrifice without having any idea where he will live himself – but Pooh comes to his rescue, and volunteers that Piglet come to live with him. Pooh further suggests to Christopher Robin, “Can you make a one-hero party into a two-hero party?” – and so they can, as Piglet becomes second guest of honor for the festivities, which close out the film as the book closes.

We’ll begin a survey of selected weather highlights from the TV days, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

In DFE’s Roland and Rattfink entry “Sweet and Sourdough” (1969), Rattfink runs outside to reach a destination before winter, only to have a season’s worth of snow fall on him in a split second.

In DFE’s Hoot Kloot episode “Phony Express” (1974), Hoot and Fester ride into a heat wave in Death Valley, and Hoot starts seeing mirages.

Chilly Willy’s bright red streamlined fireplace bucket was very fashionable in the 1960s. My family had one exactly like it, to go with our bright red streamlined mid-century modern fireplace.

The musical score to “Snowbody Loves Me” is derived entirely from the works of Chopin; one seldom hears so much Chopin outside of a Walter Lantz cartoon. I assume “Eulenspiegel’s Schnapps” refers to Till Eulenspiegel, the great practical joker of German folklore, whose adventures were set to music by Richard Strauss in his tone poem “Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks”. Chuck Jones was fond of Strauss’s music.

Tom certainly went to a lot of trouble constructing an elaborate Rube Goldberg device to extricate Jerry from a wheel of Swiss cheese. For crying out loud, just grab a knife and slice it up.

I had to laugh at your suggestion that Ralph Bakshi was inspired by Col. Bleep when he animated James Hound’s hyperkinetic eyebrows. But I suspect Bakshi was merely emphasizing them to play up Hound’s resemblance to Sean Connery, which is otherwise pretty negligible.