Although by the time covered by this week’s survey, television cartoons were coming into full swing, we’ll continue to focus this week’s offerings upon theatrical releases, returning to cover contemporary TV product in a subsequent installment. The days of short animated classics were definitely waning, but weather still continued to figure into sporadic offerings, which this week include, among others, Daffy Duck, Woody Woodpecker, two imports by Tom and Jerry, and three extended-length Disney projects.

Houndabout (Paramount, Noveltoon, 4/10/59 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – A dog (presumably of the terrier variety, given his rather square jaw) named Julius endures a highly uncomfortable night in a leaky doghouse during a rainstorm. The floor of his house is completely flooded, and Julius props himself up with all four paws against the walls of his house, just to keep himself braced above water. However, he is still feeling the moisture, as two sources of leaks drip upon his head from holes in the roof above him. Julius uses his last two appendages to plug both holes with his ears – until a new, larger hole opens directly over his brow, its water flow knocking him off balance and causing him to fall into the tummy-deep water below. Julius has had it, and eyes the comfortable abode of his master, whom he can see through the window making himself a tall sandwich in the kitchen. Julius howls at the front door, and his master relents to let him inside for once on a night like this. The master soon regrets his decision, as Julius shakes water out of his fur, drenching his owner, then attempts to take a bite out of the sandwich on the counter. Julius gets the boot back outside where he belongs. Conveniently, as the rain has served its plot-point purpose, the skies suddenly dry up on cue to save on animation budget, and Julius snaps off his collar, declaring he will no longer lead a dog’s life, and will learn to live like the humans do.

Houndabout (Paramount, Noveltoon, 4/10/59 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) – A dog (presumably of the terrier variety, given his rather square jaw) named Julius endures a highly uncomfortable night in a leaky doghouse during a rainstorm. The floor of his house is completely flooded, and Julius props himself up with all four paws against the walls of his house, just to keep himself braced above water. However, he is still feeling the moisture, as two sources of leaks drip upon his head from holes in the roof above him. Julius uses his last two appendages to plug both holes with his ears – until a new, larger hole opens directly over his brow, its water flow knocking him off balance and causing him to fall into the tummy-deep water below. Julius has had it, and eyes the comfortable abode of his master, whom he can see through the window making himself a tall sandwich in the kitchen. Julius howls at the front door, and his master relents to let him inside for once on a night like this. The master soon regrets his decision, as Julius shakes water out of his fur, drenching his owner, then attempts to take a bite out of the sandwich on the counter. Julius gets the boot back outside where he belongs. Conveniently, as the rain has served its plot-point purpose, the skies suddenly dry up on cue to save on animation budget, and Julius snaps off his collar, declaring he will no longer lead a dog’s life, and will learn to live like the humans do.

Julius exits the yard and wanders into town as day breaks. He passes a tailor’s shop, where a suit of clothes is displayed on a dummy outside. With no regard for ownership rights, Julius takes advantage of an opportune moment when no one is looking, and steals the entire outfit off the dummy. Now walking on his hind legs in the new suit, Julius admires himself in the reflection of a window, commenting “Clothes sure make the man.” He wanders over to the city park, spotting a sign saying “No Dogs Allowed.” Not so sure whether his new disguise will be effective, Julius cautiously enters the park gate. He is immediately addressed by a cop on the beat, but to his relief, the cop is just exchanging polite greetings, accepting him as human and commenting what a nice day it is for a walk. Now confident, Julius walks with pride. He spots a half-lit cigar butt on the ground, and decides to try out the humans’ habit of smoking. The taste is fine on the inhale and exhale – but the smoke vapor forms into the shape of a knot of rope, tightening for a stranglehold upon his neck. Julius’s face turns blue, then green. He collapses, his head hitting a public water fountain, breaking off part of its bowl, so that its water pours on his face as he lies prone at the fountain base, reviving him. Julius decides he’s not quite comfortable with what humans endure to enjoy smoking.

Julius exits the yard and wanders into town as day breaks. He passes a tailor’s shop, where a suit of clothes is displayed on a dummy outside. With no regard for ownership rights, Julius takes advantage of an opportune moment when no one is looking, and steals the entire outfit off the dummy. Now walking on his hind legs in the new suit, Julius admires himself in the reflection of a window, commenting “Clothes sure make the man.” He wanders over to the city park, spotting a sign saying “No Dogs Allowed.” Not so sure whether his new disguise will be effective, Julius cautiously enters the park gate. He is immediately addressed by a cop on the beat, but to his relief, the cop is just exchanging polite greetings, accepting him as human and commenting what a nice day it is for a walk. Now confident, Julius walks with pride. He spots a half-lit cigar butt on the ground, and decides to try out the humans’ habit of smoking. The taste is fine on the inhale and exhale – but the smoke vapor forms into the shape of a knot of rope, tightening for a stranglehold upon his neck. Julius’s face turns blue, then green. He collapses, his head hitting a public water fountain, breaking off part of its bowl, so that its water pours on his face as he lies prone at the fountain base, reviving him. Julius decides he’s not quite comfortable with what humans endure to enjoy smoking.

Julius passes the gates of a baseball stadium, where a fly ball lands upon the pavement and rolls out in front of him, Julius brings it to the gate attendant, and asks if they lost it. The attendant permits Julius to enter free for returning the ball, where he witnesses his first game. He tries to get into the spirit of things, by repeating everything he hears the other fans say. Unfortunately, he repeats the cheers of persons on both sides of him – one rooting for one team, the other rooting for the opponent. One of them seizes him by the collar, demanding to know “Who are you rootin’ for?” Having no idea what to say, he keeps alternating between the names of the rival teams, and is accused of being a “turncoat”. A policeman escorts Julius out bodily, stating, “What are you trying to do? Start a riot?” Julius is tossed out onto the turnstile. So Julius turns his attention to his developing appetite, and decides to try out fancy cooking in a swank French restaurant. Asked to place his order, Julius selects from a menu he can’t understand, by taking a fork, and randomly spearing an item on the menu with it. “Lobster Thermidor. An excellent choice, monsieur.” Ignoring the actual concept of the recipe (which calls for the meat to be removed from the shell), Julius is served a lobster whole. He attempts to open a claw with a metal cracking device. The lobster is still quite alive, and grabs the device, using it to clamp upon Julius’s nose. The waiter apologizes that the lobster is not quite done. He substitutes a flaming crepe Suzette, smothering the fire with a metal lid. Julius swallows the crepe, but opens his mouth, breathing fire. The waiter calmly puts out the internal blaze with the squirt of a seltzer bottle. Then comes the check. “What’s that for?” asks Julius. The waiter asks for money in every term he can name: “The sugar, the cabbage, the filthy lucre, the green stuff.” Turning inside-out his empty pockets, Julius reveals he has none of that. The polite waiter does not make a scene, but escorts Julius to the door, then brings down a large potted plant in an urn on Julius’s head.

Julius passes the gates of a baseball stadium, where a fly ball lands upon the pavement and rolls out in front of him, Julius brings it to the gate attendant, and asks if they lost it. The attendant permits Julius to enter free for returning the ball, where he witnesses his first game. He tries to get into the spirit of things, by repeating everything he hears the other fans say. Unfortunately, he repeats the cheers of persons on both sides of him – one rooting for one team, the other rooting for the opponent. One of them seizes him by the collar, demanding to know “Who are you rootin’ for?” Having no idea what to say, he keeps alternating between the names of the rival teams, and is accused of being a “turncoat”. A policeman escorts Julius out bodily, stating, “What are you trying to do? Start a riot?” Julius is tossed out onto the turnstile. So Julius turns his attention to his developing appetite, and decides to try out fancy cooking in a swank French restaurant. Asked to place his order, Julius selects from a menu he can’t understand, by taking a fork, and randomly spearing an item on the menu with it. “Lobster Thermidor. An excellent choice, monsieur.” Ignoring the actual concept of the recipe (which calls for the meat to be removed from the shell), Julius is served a lobster whole. He attempts to open a claw with a metal cracking device. The lobster is still quite alive, and grabs the device, using it to clamp upon Julius’s nose. The waiter apologizes that the lobster is not quite done. He substitutes a flaming crepe Suzette, smothering the fire with a metal lid. Julius swallows the crepe, but opens his mouth, breathing fire. The waiter calmly puts out the internal blaze with the squirt of a seltzer bottle. Then comes the check. “What’s that for?” asks Julius. The waiter asks for money in every term he can name: “The sugar, the cabbage, the filthy lucre, the green stuff.” Turning inside-out his empty pockets, Julius reveals he has none of that. The polite waiter does not make a scene, but escorts Julius to the door, then brings down a large potted plant in an urn on Julius’s head.

Now realizing the value of money, Julius passes a store which includes an outdoor slot machine. (Gambling laws must be loose in this town.) A single coin is still in the tray at the machine’s base, and Julius thinks it has fallen out accidentally, so replaces it into the machine via the coin slot. Fortune smiles on him, and he hits a jackpot. Now, he hears a whisper from someone beside him, who turns out to be a racing tout. The man recommends running that chicken feed up into some real scratch, by giving him a tip on a horse, and sending him into a local bookie joint. Julius nervously listens to the racing results inside, and his horse comes in – the 100 to 1 shot. Julius exits the racing parlor with his suit bulging with dollar bills, shouting, “I’m rich! I’m rich!” Within a split second, he is at gunpoint from two hold-up men on either side. The two fire as Julius ducks, blasting away the barrels of their respective pistols. The robbers switch to knives, as Julius tries to outrun them around a corner. Seeing no ready means of escape, Julius removes his clothes, pitching the entire outfit and the money over a fence, and nervously sits in canine position on the pavement as the crooks round the corner. They overlook him entirely, and continue on in opposite directions, still looking for their intended human target. Julius races back to his own yard, snaps his collar back on, and lays down inside the doghouse, where he receives his morning bowl of dog food from his master. “There’s nothing like a dog’s life after all”, closes Julius.

Now realizing the value of money, Julius passes a store which includes an outdoor slot machine. (Gambling laws must be loose in this town.) A single coin is still in the tray at the machine’s base, and Julius thinks it has fallen out accidentally, so replaces it into the machine via the coin slot. Fortune smiles on him, and he hits a jackpot. Now, he hears a whisper from someone beside him, who turns out to be a racing tout. The man recommends running that chicken feed up into some real scratch, by giving him a tip on a horse, and sending him into a local bookie joint. Julius nervously listens to the racing results inside, and his horse comes in – the 100 to 1 shot. Julius exits the racing parlor with his suit bulging with dollar bills, shouting, “I’m rich! I’m rich!” Within a split second, he is at gunpoint from two hold-up men on either side. The two fire as Julius ducks, blasting away the barrels of their respective pistols. The robbers switch to knives, as Julius tries to outrun them around a corner. Seeing no ready means of escape, Julius removes his clothes, pitching the entire outfit and the money over a fence, and nervously sits in canine position on the pavement as the crooks round the corner. They overlook him entirely, and continue on in opposite directions, still looking for their intended human target. Julius races back to his own yard, snaps his collar back on, and lays down inside the doghouse, where he receives his morning bowl of dog food from his master. “There’s nothing like a dog’s life after all”, closes Julius.

Noah’s Ark (Disney, 11/10/59 – Bill Justice, dir.) – A fairly straight retelling of the story in musical rhyme, without quite the spectacle of the original “Father Noah’s Ark” of 1933. What is unique, however, is that Disney tries out a medium with which it was not altogether familiar at the time – stop-motion animation. Disney was in no class to match the talents of George Pal at this craft – and indeed, didn’t even try to achieve such a Herculean feat. But possibly, director Justice may have conceived the idea for this extended short by observing children’s arts and crafts projects from grade school, seeing youngsters creating three-dimensional figures roughly resembling animals out of household items and miscellaneous junk. Thus, he assembles an entire array of animals, and even some principal human characters, out of such bric-a-brac. In a creative title sequence, Justice lets us in on the concept of what is going on, by demonstrating in stop-motion a sort of “how-to” on the construction of several of the animals. Flamingos, using pink pipe cleaners and hard-boiled eggs. Giraffes, using yellow number-2 pencils. Hippos, using corks cut into two parts for their heads. And so on. The film, even if sometimes crude in motion and sparce in backgrounds (which often show the shadow upon the backdrops of the three-dimensional objects placed before them), has a certain child-like creativeness to it that gives it a unique style, different from Rankin-Bass, Art Clokey, or other stop-motion masters of the day. A catchy music score by George Bruns and Mel Leven keeps the film lively and well-paced (including an interesting bluesy reverie from Mrs. Hippo – “Don’t Mention His Name To Me”). Nominated for an Academy Award. In the wake of this production, Disney would permit a few more stop-motion experiments, relying more heavily upon paper cutout animation, for animated credits to “The Misadventures of Merlin Jones”, and for Ludwig Von Drake’s only theatrical short, “A Symposium on Popular Songs.”

Noah’s Ark (Disney, 11/10/59 – Bill Justice, dir.) – A fairly straight retelling of the story in musical rhyme, without quite the spectacle of the original “Father Noah’s Ark” of 1933. What is unique, however, is that Disney tries out a medium with which it was not altogether familiar at the time – stop-motion animation. Disney was in no class to match the talents of George Pal at this craft – and indeed, didn’t even try to achieve such a Herculean feat. But possibly, director Justice may have conceived the idea for this extended short by observing children’s arts and crafts projects from grade school, seeing youngsters creating three-dimensional figures roughly resembling animals out of household items and miscellaneous junk. Thus, he assembles an entire array of animals, and even some principal human characters, out of such bric-a-brac. In a creative title sequence, Justice lets us in on the concept of what is going on, by demonstrating in stop-motion a sort of “how-to” on the construction of several of the animals. Flamingos, using pink pipe cleaners and hard-boiled eggs. Giraffes, using yellow number-2 pencils. Hippos, using corks cut into two parts for their heads. And so on. The film, even if sometimes crude in motion and sparce in backgrounds (which often show the shadow upon the backdrops of the three-dimensional objects placed before them), has a certain child-like creativeness to it that gives it a unique style, different from Rankin-Bass, Art Clokey, or other stop-motion masters of the day. A catchy music score by George Bruns and Mel Leven keeps the film lively and well-paced (including an interesting bluesy reverie from Mrs. Hippo – “Don’t Mention His Name To Me”). Nominated for an Academy Award. In the wake of this production, Disney would permit a few more stop-motion experiments, relying more heavily upon paper cutout animation, for animated credits to “The Misadventures of Merlin Jones”, and for Ludwig Von Drake’s only theatrical short, “A Symposium on Popular Songs.”

101 Dalmatians (Disney, 1/23/61) – This well-known and beloved Disney classic, in typical Disney fashion, makes good use of weather, both for dramatic effect and in furtherance of the plotline. Dalmatians Pongo and Perdita are expecting a litter of puppies, and the night of their arrival is a wild and stormy one, with rain outside the family flat and lightning flashing periodically through the sky. Pongo is nearly bowled over by the news that 15 puppies have arrived – but a tragedy seems to follow on the heels of this good news, as the family maid, Nanny Cook, announces that “We lost one”, carrying the tiny, lifeless form of one of the pups in, wrapped in a small towel. Roger, Pongo’s owner, tries to console Pongo. “It’s just one of those things…And yet, I wonder.” With gentle but firm hands, he begins to stroke and massage the form of the pup within the towel, while a curious, not quite ready to allow himself to be hopeful Pongo looks on. Tense minutes go by, and then a small bolt of lightning is seen striking outside the room’s window. As if the lightning has breathed life back into his body, the puppy begins to move, its nose curiously sniffing outside the folds of the towel. “Fifteen! We still have fifteen!”, calls out Roger, as an amazed Pongo breathes a sigh of relief. The lightning, however, continues to play a dramatic role, providing a flamboyant backdrop for the entrance of Cruella DeVil at the front door – just as if she walked out of a bad horror movie. With motives undisclosed, Cruella wants to immediately purchase all the puppies, but Roger, not trusting her intentions, refuses to sell.

101 Dalmatians (Disney, 1/23/61) – This well-known and beloved Disney classic, in typical Disney fashion, makes good use of weather, both for dramatic effect and in furtherance of the plotline. Dalmatians Pongo and Perdita are expecting a litter of puppies, and the night of their arrival is a wild and stormy one, with rain outside the family flat and lightning flashing periodically through the sky. Pongo is nearly bowled over by the news that 15 puppies have arrived – but a tragedy seems to follow on the heels of this good news, as the family maid, Nanny Cook, announces that “We lost one”, carrying the tiny, lifeless form of one of the pups in, wrapped in a small towel. Roger, Pongo’s owner, tries to console Pongo. “It’s just one of those things…And yet, I wonder.” With gentle but firm hands, he begins to stroke and massage the form of the pup within the towel, while a curious, not quite ready to allow himself to be hopeful Pongo looks on. Tense minutes go by, and then a small bolt of lightning is seen striking outside the room’s window. As if the lightning has breathed life back into his body, the puppy begins to move, its nose curiously sniffing outside the folds of the towel. “Fifteen! We still have fifteen!”, calls out Roger, as an amazed Pongo breathes a sigh of relief. The lightning, however, continues to play a dramatic role, providing a flamboyant backdrop for the entrance of Cruella DeVil at the front door – just as if she walked out of a bad horror movie. With motives undisclosed, Cruella wants to immediately purchase all the puppies, but Roger, not trusting her intentions, refuses to sell.

As those familiar with the story will know, Cruella hires a pair of “bad-uns” (Horace and Jasper) to steal the puppies, leaving no trail and baffling Scotland Yard. Only the dogs are able to play detective and put two and two together, by means of their mass communications link, the Twilight Bark, to trace the puppies to an old estate in the country, thought abandoned but actually owned by DeVil. Pongo and Perdita set off to the rescue, just as the dead of winter begins to set in. Snow blankets the countryside, and ice-filled rivers provide treacherous obstacles. They of course still make their way through, allowing the pups (and 84 more pups purchased from pet shops) to escape an intended fate in which they were to be transformed into dogskin coats.

The winter weather plays important roles in their trek as they try to make their way back to London, one step ahead of Cruella and the “bad-uns”. To keep their tracks from being seen, the dogs walk upon the ice of a frozen creek, huddling under a bridge to hide when Horace and Jasper pass above. Their feet are cold and slippery, but the ruse works. The next day finds them bucking the wind against a fierce blizzard. It is all that Pongo and Perdita can do to keep the column of puppies moving, and the sequence is one of the most emotionally-moving in the film, as the puppies reach near-exhaustion, and one of them (Lucky) simply can’t move any more from being nearly-frozen, and has to be carried by Pongo. Thankfully, a sanctuary presents itself, in the form of a dairy whose guard dog has been alerted of the Pongos’ imminent arrival. A place to rest, and milk for all. Next day finds the pups refreshed and energetic – but still not out of danger, as their path toward London requires the crossing of a snow-covered road. As Cruella’s car is heard in the distance, Pongo attempts to whisk away the tell-tale tracks with the ends of a fallen tree branch – but the effort proves futile, as there is no time to clear tracks remaining visible on either side of the road. A final climactic car chase has Cruella driving like a maniac straight out of hell, pursuing a moving van in which the Dalmatians are riding over icy country roads. Horace and Jasper attempt to intercept the van from a side road, but fail to time their approach properly, sliding down a steep, snowy slope – and collide with Cruella’s car instead, wrecking both pursuing vehicles, while the van carries on to London – and home.

The Saga of Windwagon Smith (Disney, 3/16/61 – Charles Nichols, dir.) – An interesting stylized film, using flattened, UPA influenced animation, and many amber-sky backgrounds (possibly influenced by the amber wood-etching color scheme of Friz Freleng’s Bugs Bunny short, “Wild and Wooly Hare”). A superb theme song flows through the music score and provides key exposition, performed by the Sons of the Pioneers. I am not entirely familiar with the chronology of the singers of this group, but their vocal blend on this film seems to precisely match its sound in the 1940’s production of “Pecos Bill” – a sound which had not been heard for years on their stereo recordings made for RCA Victor, which seem to lack requisite tenor lead – so one wonders who stepped in for this session, and whether in fact it marks a reunion for some of their vocalists from days of old. For a crowning touch, narration is provided by Rex Allen, veteran of many a Disney voice-over for its nature films, including concurrent or future feature projects on “The Incredible Journey” and “The Legend of Lobo” – in his only appearance on an animated short.

The Saga of Windwagon Smith (Disney, 3/16/61 – Charles Nichols, dir.) – An interesting stylized film, using flattened, UPA influenced animation, and many amber-sky backgrounds (possibly influenced by the amber wood-etching color scheme of Friz Freleng’s Bugs Bunny short, “Wild and Wooly Hare”). A superb theme song flows through the music score and provides key exposition, performed by the Sons of the Pioneers. I am not entirely familiar with the chronology of the singers of this group, but their vocal blend on this film seems to precisely match its sound in the 1940’s production of “Pecos Bill” – a sound which had not been heard for years on their stereo recordings made for RCA Victor, which seem to lack requisite tenor lead – so one wonders who stepped in for this session, and whether in fact it marks a reunion for some of their vocalists from days of old. For a crowning touch, narration is provided by Rex Allen, veteran of many a Disney voice-over for its nature films, including concurrent or future feature projects on “The Incredible Journey” and “The Legend of Lobo” – in his only appearance on an animated short.

A Conestoga wagon blows into the Kansas town of Westport in a cloud of dust, spooking horses and the community in general. It hitches itself to a hitching post by tossing out an anchor. When the dust clears, the townsfolk observe that there are no horses or oxen drawing the wagon. Instead, a deck is built above the wagon’s canvas canopy, a mast with sail mounted above through the wagon’s middle, and a tiller bar extends down from the mast to steer the wagon’s rear wheels. The captain of the vessel, one Windwagon Smith, descends in full naval outfit. Mayor Crumb is delegated to address the stranger, and deduces that the wind is what makes the wagon move. Smith explains that the prevailing Kansas winds permit sailing over the buffalo grass of the prairie as easy for him as sailing the seas. He suggests they belay the talk while he orders some grub at the local saloon, where he meets the mayor’s daughter, the seductive Molly, as waitress. His heart does a hornpipe flip, and he performs a Tex Avery-style take as he devours plates and saucers instead of his food while his eyes remain transfixed on the lovely view. The Mayor ushers Molly away, then engages Smith in business-talk, asking if his vessel will haul freight. Smith declares freight is nothing more than ballast to him, and he can haul a full cargo down the Santa Fe Trail in a record 14 days – a quarter of the usual time for ox-drawn wagon. The Mayor suggests that the wagons should be larger to permit double the profit, and Smith unfurls blueprints he has already designed for a super windwagon. A company is formed among Smith ad the townsfolk, and investment money piles high.

A Conestoga wagon blows into the Kansas town of Westport in a cloud of dust, spooking horses and the community in general. It hitches itself to a hitching post by tossing out an anchor. When the dust clears, the townsfolk observe that there are no horses or oxen drawing the wagon. Instead, a deck is built above the wagon’s canvas canopy, a mast with sail mounted above through the wagon’s middle, and a tiller bar extends down from the mast to steer the wagon’s rear wheels. The captain of the vessel, one Windwagon Smith, descends in full naval outfit. Mayor Crumb is delegated to address the stranger, and deduces that the wind is what makes the wagon move. Smith explains that the prevailing Kansas winds permit sailing over the buffalo grass of the prairie as easy for him as sailing the seas. He suggests they belay the talk while he orders some grub at the local saloon, where he meets the mayor’s daughter, the seductive Molly, as waitress. His heart does a hornpipe flip, and he performs a Tex Avery-style take as he devours plates and saucers instead of his food while his eyes remain transfixed on the lovely view. The Mayor ushers Molly away, then engages Smith in business-talk, asking if his vessel will haul freight. Smith declares freight is nothing more than ballast to him, and he can haul a full cargo down the Santa Fe Trail in a record 14 days – a quarter of the usual time for ox-drawn wagon. The Mayor suggests that the wagons should be larger to permit double the profit, and Smith unfurls blueprints he has already designed for a super windwagon. A company is formed among Smith ad the townsfolk, and investment money piles high.

The super windwagon goes into production. During construction, Smith strikes up a romantic interest with Molly, meeting her at night on the unfinished deck. The Mayor tries to interfere with the meetings, sending Molly home with the warning, “I’ve heard about sailors, you know”, causing Smith to sheepishly blush. A new dawn finds the unveiling of the massive new windwagon, with 12-foot wheels. The Mayor and board of directors pile into the hold to ride on the maiden voyage – but the Mayor sends Molly home following her Christening of the wagon’s cigar-store Indian figurehead with a jug of Kansas corn, insisting the voyage is for men only. Smith sets sail, and the wagon picks up speed until it is going sixty. The Mayor and board are trembling in the knees, and turning green from seasickness. They shout for Smith to let them off, and Smith turns the tiller to steer the wagon back towards town. But an unexpected mishap occurs, as the tiller sticks fast and cannot be pulled back to straighten out the vessel’s path – leaving it circling the town in a path two miles in diameter. On each spin past the town, members of the board, and finally the Mayor, jump out and abandon ship. Smith is left alone on deck, determined to go down with the wreck. But a hatch opens, and Molly appears from below decks, as the wagon’s first stowaway. “My captain, don’t give up the ship”, she coos. Smith turns to observe they are in for a blow, as a Kansas twister worthy of Dorothy Gale approaches. The Wagon is swept up in the funnel cloud, and rises, spinning violently. The force of the cyclone snaps the tiller free of its obstruction, and Smith declares he can steer again, and that they will ride out the storm. The wagon is last seen riding atop the cyclone, headed due West. In the film’s final scenes, years have passed, and the saddened Mayor and other former members of the company are now old-timers, who carry on tales of the old windwagon. They swear that at times when the sunset turns to gold, they can still see the windwagon, sailing in a sort of permanent orbit atop the clouds. Here, whether by means of their dreams or in reality, we close with view of the wagon, Smith and Molly (neither of whom seem to be any worse for wear despite the passage of years), as Smith sings of “Just Molly and me, o’er the lone prairie, on our wagon way up in the sky.” As food and provisions should have run out long ago, we can only assume this to be some sort of happy afterlife in the heavenly skies, as the wagon sails away into the golden clouds.

The super windwagon goes into production. During construction, Smith strikes up a romantic interest with Molly, meeting her at night on the unfinished deck. The Mayor tries to interfere with the meetings, sending Molly home with the warning, “I’ve heard about sailors, you know”, causing Smith to sheepishly blush. A new dawn finds the unveiling of the massive new windwagon, with 12-foot wheels. The Mayor and board of directors pile into the hold to ride on the maiden voyage – but the Mayor sends Molly home following her Christening of the wagon’s cigar-store Indian figurehead with a jug of Kansas corn, insisting the voyage is for men only. Smith sets sail, and the wagon picks up speed until it is going sixty. The Mayor and board are trembling in the knees, and turning green from seasickness. They shout for Smith to let them off, and Smith turns the tiller to steer the wagon back towards town. But an unexpected mishap occurs, as the tiller sticks fast and cannot be pulled back to straighten out the vessel’s path – leaving it circling the town in a path two miles in diameter. On each spin past the town, members of the board, and finally the Mayor, jump out and abandon ship. Smith is left alone on deck, determined to go down with the wreck. But a hatch opens, and Molly appears from below decks, as the wagon’s first stowaway. “My captain, don’t give up the ship”, she coos. Smith turns to observe they are in for a blow, as a Kansas twister worthy of Dorothy Gale approaches. The Wagon is swept up in the funnel cloud, and rises, spinning violently. The force of the cyclone snaps the tiller free of its obstruction, and Smith declares he can steer again, and that they will ride out the storm. The wagon is last seen riding atop the cyclone, headed due West. In the film’s final scenes, years have passed, and the saddened Mayor and other former members of the company are now old-timers, who carry on tales of the old windwagon. They swear that at times when the sunset turns to gold, they can still see the windwagon, sailing in a sort of permanent orbit atop the clouds. Here, whether by means of their dreams or in reality, we close with view of the wagon, Smith and Molly (neither of whom seem to be any worse for wear despite the passage of years), as Smith sings of “Just Molly and me, o’er the lone prairie, on our wagon way up in the sky.” As food and provisions should have run out long ago, we can only assume this to be some sort of happy afterlife in the heavenly skies, as the wagon sails away into the golden clouds.

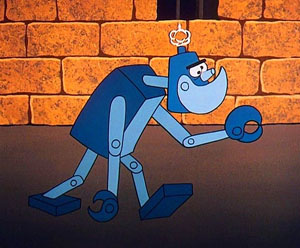

Franken-Stymied (Lantz/Universal, 7/8/61 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – Another Halloween-style atmospheric, set on a dark and stormy night. Woody races through the countryside, trying to stay one jump ahead of the lightning from a storm, which lights him in skeletal glow from several hits, and blasts craters in the ground behind him. As usual, a spooky castle presents itself. Inside, a mad scientist (unique in design in that his mouth is constantly full of closed teeth – even when his lips open to talk) is just bringing to life his ultimate creation – a robot who blows periodic smoke puffs through a stack like the Tin Man in the Wizard of Oz, and whose primary power lies in the use of hinged pincer claws serving as hands. He is not merely a robot – but a mechanical chicken-plucker. The device, however, has a one-track mind, and is constantly in search of something to pluck – beginning with the hairs of the mad doctor’s moustache. The doctor realizes he must get “Frankie” a real bird to pluck in a hurry, or become clean-shaven himself. The knocks of Woody at the door are music to his ears, as Woody’s feathers will suit Frankie fine. The doctor closes about seven types of metal doors on the castle entrance – excusing his conduct as intended “to keep the rain out.” He then introduces Woody to Frankie. “Frankly speaking”, Woody offers the robot his hand in a show of friendship. Instead of a return shake, Frankie takes Woody over his knee, and begins liberally plucking feathers out of Woody’s back. A typical chase ensues through the castle, with Frankie plucking more feathers at every turn where Woody hides.

Franken-Stymied (Lantz/Universal, 7/8/61 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – Another Halloween-style atmospheric, set on a dark and stormy night. Woody races through the countryside, trying to stay one jump ahead of the lightning from a storm, which lights him in skeletal glow from several hits, and blasts craters in the ground behind him. As usual, a spooky castle presents itself. Inside, a mad scientist (unique in design in that his mouth is constantly full of closed teeth – even when his lips open to talk) is just bringing to life his ultimate creation – a robot who blows periodic smoke puffs through a stack like the Tin Man in the Wizard of Oz, and whose primary power lies in the use of hinged pincer claws serving as hands. He is not merely a robot – but a mechanical chicken-plucker. The device, however, has a one-track mind, and is constantly in search of something to pluck – beginning with the hairs of the mad doctor’s moustache. The doctor realizes he must get “Frankie” a real bird to pluck in a hurry, or become clean-shaven himself. The knocks of Woody at the door are music to his ears, as Woody’s feathers will suit Frankie fine. The doctor closes about seven types of metal doors on the castle entrance – excusing his conduct as intended “to keep the rain out.” He then introduces Woody to Frankie. “Frankly speaking”, Woody offers the robot his hand in a show of friendship. Instead of a return shake, Frankie takes Woody over his knee, and begins liberally plucking feathers out of Woody’s back. A typical chase ensues through the castle, with Frankie plucking more feathers at every turn where Woody hides.

Woody catches on that the device is a chicken-plucker, and sets a lure for the robot by placing a feather on the end of a long pole. Like holding a carrot out in front of a mule, the robot is tricked into pursuing the feather to the edge of a flight of descending stairs – and tumbles down them, lying in a pile of disassembled parts at the foot of the staircase. “Well, that fractures Frankie”, quips Woody. “Frankie is indestructible”, boasts the doctor, pushing and pulling at levers on a control panel. Frankie’s parts become magnetically attracted to one another, and Frankie returns to his original assembled form. On the other side of the room, Woody spots a high voltage control and wire. He tricks Frankie into plucking at the exposed wire, blasting the robot apart again with the electric shock. The doctor jostles his levers, and Frankie reassembles – with some slight problems, as his parts are now randomly attached in places they don’t belong. Woody sends another shockwave into Frankie – and the two engage in a game of assemble and disassemble, the robot contorting into various odd restructurings of its components like a jigsaw puzzle, assuming shapes resembling a dog, a crab, and other weird combinations, including its arm attached where its nose should be. Woody finally realizes, “This is getting us strictly nowhere.” He darts up a staircase while the doctor performs a final reassembly of Frankie, then drops upon the doctor from above a pot of glue. Woody follows this with a liberal rain of feathers from a pillow, coating the doctor all over in white feathers firmly stuck to his person. One excited look by Frankie, and an inviting “Cluck cluck cluck” from Woody to attract him, and the doctor can see he’s in for no end of trouble. Frankie puts his instinctive abilities to work upon the new white “bird”, ignoring the doctor’s protests that he is not a chicken, and the feathers fly throughout the castle. Woody emerges from the castle, still in possession of most of his plumage, the rain now having subsided, and leaves performing his own mocking impression of the robot’s walk, followed by his signature laugh.

Woody catches on that the device is a chicken-plucker, and sets a lure for the robot by placing a feather on the end of a long pole. Like holding a carrot out in front of a mule, the robot is tricked into pursuing the feather to the edge of a flight of descending stairs – and tumbles down them, lying in a pile of disassembled parts at the foot of the staircase. “Well, that fractures Frankie”, quips Woody. “Frankie is indestructible”, boasts the doctor, pushing and pulling at levers on a control panel. Frankie’s parts become magnetically attracted to one another, and Frankie returns to his original assembled form. On the other side of the room, Woody spots a high voltage control and wire. He tricks Frankie into plucking at the exposed wire, blasting the robot apart again with the electric shock. The doctor jostles his levers, and Frankie reassembles – with some slight problems, as his parts are now randomly attached in places they don’t belong. Woody sends another shockwave into Frankie – and the two engage in a game of assemble and disassemble, the robot contorting into various odd restructurings of its components like a jigsaw puzzle, assuming shapes resembling a dog, a crab, and other weird combinations, including its arm attached where its nose should be. Woody finally realizes, “This is getting us strictly nowhere.” He darts up a staircase while the doctor performs a final reassembly of Frankie, then drops upon the doctor from above a pot of glue. Woody follows this with a liberal rain of feathers from a pillow, coating the doctor all over in white feathers firmly stuck to his person. One excited look by Frankie, and an inviting “Cluck cluck cluck” from Woody to attract him, and the doctor can see he’s in for no end of trouble. Frankie puts his instinctive abilities to work upon the new white “bird”, ignoring the doctor’s protests that he is not a chicken, and the feathers fly throughout the castle. Woody emerges from the castle, still in possession of most of his plumage, the rain now having subsided, and leaves performing his own mocking impression of the robot’s walk, followed by his signature laugh.

You can watch it on Halloween (or anytime) if you CLICK here.

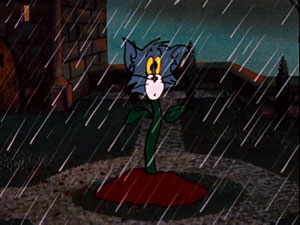

Switchin’ Kitten (Rembrandt Films/MGM, 9/7/61 – Gene Deitch, dir,)- A wild, stormy night in the twisting hills surrounding another mysterious castle sets the atmospheric scene for another tale of cartoon Gothic horror. A dark coach passes along a country road at full gallop, not even slowing to toss out a large sack along the road, which begins squirming the moment it hits ground. The rain water shrinks the sack around its contents, revealing inside Tom, who emerges wearing the shrunken sack as if it were a shower cap. Tom shakes his fist angrily at the coach, then races for the castle as the only shelter available. Inside, a lunatic, hysterically-giggling mad scientist is hard at work, ably assisted by, of all “people”, Jerry, who stands in as the scientist’s “Igor”: The scientist readies an elaborate row of machines, then allows Jerry to select as a subject for experiment one of several alley cats imprisoned in a cell. The cat is strapped to a lab table, aside another table to which is strapped a bulldog. Two helmets descend upon the subjects, instantly detecting in visual readouts the presence of a cat and dog, respectively, below them. The scientist throws the switches, and Jerry maneivers several dials and lights. Electricity pulses between the helmets, and suddenly the readouts on each reverse themselves, the dog’s helmet reading “Cat”, and vice-versa. The scientist releases what once was the cat, who takes on all the mannerisms of a friendly dog, holding Jerry fondly in his arms, and treating the mouse like his best friend.

Switchin’ Kitten (Rembrandt Films/MGM, 9/7/61 – Gene Deitch, dir,)- A wild, stormy night in the twisting hills surrounding another mysterious castle sets the atmospheric scene for another tale of cartoon Gothic horror. A dark coach passes along a country road at full gallop, not even slowing to toss out a large sack along the road, which begins squirming the moment it hits ground. The rain water shrinks the sack around its contents, revealing inside Tom, who emerges wearing the shrunken sack as if it were a shower cap. Tom shakes his fist angrily at the coach, then races for the castle as the only shelter available. Inside, a lunatic, hysterically-giggling mad scientist is hard at work, ably assisted by, of all “people”, Jerry, who stands in as the scientist’s “Igor”: The scientist readies an elaborate row of machines, then allows Jerry to select as a subject for experiment one of several alley cats imprisoned in a cell. The cat is strapped to a lab table, aside another table to which is strapped a bulldog. Two helmets descend upon the subjects, instantly detecting in visual readouts the presence of a cat and dog, respectively, below them. The scientist throws the switches, and Jerry maneivers several dials and lights. Electricity pulses between the helmets, and suddenly the readouts on each reverse themselves, the dog’s helmet reading “Cat”, and vice-versa. The scientist releases what once was the cat, who takes on all the mannerisms of a friendly dog, holding Jerry fondly in his arms, and treating the mouse like his best friend.

Tom appears at one of the castle windows, drenched from the storm. The first thing he spies inside is Jerry, and Tom could do with a good meal. He darts in and snatches Jerry up in his paw. Jerry gives a whistle, and Tom is suddenly confronted by the cat-turned-dog. Tom can’t understand why the cat is upset at his behavior – and assumes he merely wants to get a piece of the action in bashing the mouse. Tom thus graciously hands the cat a mallet, and bows to permit the other cat to do the honors of knocking Jerry senseless. Instead, the cat applies the mallet to Tom’s head. Tom tries to appeal to the cat’s natural allegiances, showing him that he’s a card-carrying union member (“International Brotherhood of Cats”), and demonstrates how to slap a mouse around. Tom receives another whack to the head that internally shatters every bone in his body, leaving Tom looking like a formless furry sack of trash. The cat-dog carries Tom outside, burying him in the moist earth of the castle courtyard. Soaked by the rain, something sprouts from the ground – Tom’s tail, which buds like a flower, revealing Tom’s face inside as its bloom.

Tom appears at one of the castle windows, drenched from the storm. The first thing he spies inside is Jerry, and Tom could do with a good meal. He darts in and snatches Jerry up in his paw. Jerry gives a whistle, and Tom is suddenly confronted by the cat-turned-dog. Tom can’t understand why the cat is upset at his behavior – and assumes he merely wants to get a piece of the action in bashing the mouse. Tom thus graciously hands the cat a mallet, and bows to permit the other cat to do the honors of knocking Jerry senseless. Instead, the cat applies the mallet to Tom’s head. Tom tries to appeal to the cat’s natural allegiances, showing him that he’s a card-carrying union member (“International Brotherhood of Cats”), and demonstrates how to slap a mouse around. Tom receives another whack to the head that internally shatters every bone in his body, leaving Tom looking like a formless furry sack of trash. The cat-dog carries Tom outside, burying him in the moist earth of the castle courtyard. Soaked by the rain, something sprouts from the ground – Tom’s tail, which buds like a flower, revealing Tom’s face inside as its bloom.

Tom continues to try to drive some sense into the mysterious cat, showing him an encyclopedia full of cat pictures – but gets unexpected reaction as the cat tears every picture out of the book, then smashes Tom in its pages. (Tom only “finds himself” in the book by sticking his arm out of its pages and running his fingers along alphabetical tabs on the side until he comes to “T”.) The cat charges Tom like a freight train, battles him inside a “cuckoo” grandfather’s clock, then forces Tom into a shape-shifting ride through the scientist’s test tubes that strongly resembles Harman-Ising’s “Bottles” but without the vivid splashes of Technicolor. Tom flees for any exit. He tries to open various castle doors – but finds surprising occupants – such as an elephant who chirps like a songbird and flaps his ears. A chicken who “baaa”s like a goat. The bulldog, who says, “Meow”. And a cuckoo bird in the clock who says, “Moo”. Tom spots Jerry alone at a mousehole. He approaches Jerry on bended knees, begging for some kind of explanation. In the topper of toppers, Jerry enters and rests in the entrance to his mousehole. A closer inspection of the hole reveals a familiar-looking border around it, with the inscription, “Ars Gratia Artis” – and Jerry roars as the MGM lion! Tom has reached the end of hs sanity, and transforms into a living rocket, blasting through the ceiling into space, and out onto the rainy country road, where he disappears into the night. Jerry-Leo winks at the audience for the final fade out.

Buddies Thicker Than Water (Rembrandt Films/MGM, 11/1/62 – Gene Deitch, dir.) – Fortune has smiled on Jerry, who resides cozily in a mousehole in a swank penthouse apartment. Even his mousehole is classy, with bed made from a plush jewelry box, a 14 karat gold framed hand mirror, and a small painting on the wall of Tom as if painted by Picasso! Fate has not looked similarly upon Tom, who has somehow again managed to be down and out, and emerges from under a coating of snow on the street below, shivering and pacing about briskly to try to keep from developing hypothermia in the height of a blizzard. Desperately, he scrounges up a milk bottle and a piece of paper from a trash can, and writes a note, then hurls it up iside the bottle to the patio landing of the penthouse. The clank of the bottle awakens Jerry, who puts on a velvet dressing robe and ventures out onto the snow-covered roof landing, finding the note, which reads, “Help! I’m Freezing. Your old pal, Tom.” Suddenly, Jerry is clunked by a second bottle, which drives him momentarily into the snow. It is another note, reading, “I’m also starving. Tom.” Jerry takes the elevator down to ground level, and finds Tom outside, prone in the snow, who before Jerry’s eyes freezes into solid blue ice. Jerry inverts a trash can lid, and drags frozen Tom atop it. Then, using the lid like a sled, he pushes Tom into the building. Returning to the penthouse floor, Jerry cautiously enters the apartment with a screwdriver, and removes the screws from a wall vent grating, allowing him to open a hole in the wall big enough to slide Tom into. Once Tom is safely inside, Jerry covers him with an electric blanket, pushing the button on its controls to high heat. Tom briefly turns red hot, but Jerry presses the off button, and Tom is safely and comfortably thawed. The grateful cat kisses Jerry for his kind deed. Jerry next takes care of Tom’s food needs, producing a plate of dehydrated powder and a glass of water. Just add water, and the platter is instantly full of a sizzling steak, fish, mashed potatoes, asparagus, and a dinner roll! (Modern advances sure make raiding the pantry a whole lot easier.)

Buddies Thicker Than Water (Rembrandt Films/MGM, 11/1/62 – Gene Deitch, dir.) – Fortune has smiled on Jerry, who resides cozily in a mousehole in a swank penthouse apartment. Even his mousehole is classy, with bed made from a plush jewelry box, a 14 karat gold framed hand mirror, and a small painting on the wall of Tom as if painted by Picasso! Fate has not looked similarly upon Tom, who has somehow again managed to be down and out, and emerges from under a coating of snow on the street below, shivering and pacing about briskly to try to keep from developing hypothermia in the height of a blizzard. Desperately, he scrounges up a milk bottle and a piece of paper from a trash can, and writes a note, then hurls it up iside the bottle to the patio landing of the penthouse. The clank of the bottle awakens Jerry, who puts on a velvet dressing robe and ventures out onto the snow-covered roof landing, finding the note, which reads, “Help! I’m Freezing. Your old pal, Tom.” Suddenly, Jerry is clunked by a second bottle, which drives him momentarily into the snow. It is another note, reading, “I’m also starving. Tom.” Jerry takes the elevator down to ground level, and finds Tom outside, prone in the snow, who before Jerry’s eyes freezes into solid blue ice. Jerry inverts a trash can lid, and drags frozen Tom atop it. Then, using the lid like a sled, he pushes Tom into the building. Returning to the penthouse floor, Jerry cautiously enters the apartment with a screwdriver, and removes the screws from a wall vent grating, allowing him to open a hole in the wall big enough to slide Tom into. Once Tom is safely inside, Jerry covers him with an electric blanket, pushing the button on its controls to high heat. Tom briefly turns red hot, but Jerry presses the off button, and Tom is safely and comfortably thawed. The grateful cat kisses Jerry for his kind deed. Jerry next takes care of Tom’s food needs, producing a plate of dehydrated powder and a glass of water. Just add water, and the platter is instantly full of a sizzling steak, fish, mashed potatoes, asparagus, and a dinner roll! (Modern advances sure make raiding the pantry a whole lot easier.)

After dinner, Tom and Jerry sneak out from the wall, making certain that no one is home. Jerry puts a record on the stereo, while Tom gets into the wine cabinet, opening one of a series of bottles of fine wines and champagne. After polishing off three or four bottles, the two friends are quite giddy, and lay in full view in the center of the living room, laughing it up. A key turn at the front door signals the arrival of the owner of the apartment – an obviously prosperous young woman (a rather forward-looking image for a cartoon of its day, considering that there is no sign of a husband about). Jerry takes the cue to disappear into the mousehole, but Tom is not so fast on the uptake, and is caught with the goods as he is discovered with the open bottles. The owner grabs Tom by the scruff of the neck, proceeds to the porch door, and is abut to toss Tom off the roof. But clever Tom breaks loose from her grasp, and hits upon a way to remain in these posh surroundings. He darts back to the mousehole, reaches his paw in, and grabs Jerry – proving to the owner that he is a good mouser. With no regard for his friendship and Jerry’s good deed, Tom drops Jerry off the roof, giving Jerry no more acknowledgement than to wave bye-bye, Within moments, Tom is reclining in the young woman’s lap, accepted into the household and purring like a kitten at the woman’s stroking caresses. Jerry meanwhile finds himself buried in the snowdrift upon Tom’s street home below. He quickly scrambles out of the snow, and again returns to the penthouse via the elevator. The owner has by now retired to bed, and Tom himself sleeps comfortably in the living room, on a plush velvet pillow, with a ready supply within reach of caviar and bon-bons.

After dinner, Tom and Jerry sneak out from the wall, making certain that no one is home. Jerry puts a record on the stereo, while Tom gets into the wine cabinet, opening one of a series of bottles of fine wines and champagne. After polishing off three or four bottles, the two friends are quite giddy, and lay in full view in the center of the living room, laughing it up. A key turn at the front door signals the arrival of the owner of the apartment – an obviously prosperous young woman (a rather forward-looking image for a cartoon of its day, considering that there is no sign of a husband about). Jerry takes the cue to disappear into the mousehole, but Tom is not so fast on the uptake, and is caught with the goods as he is discovered with the open bottles. The owner grabs Tom by the scruff of the neck, proceeds to the porch door, and is abut to toss Tom off the roof. But clever Tom breaks loose from her grasp, and hits upon a way to remain in these posh surroundings. He darts back to the mousehole, reaches his paw in, and grabs Jerry – proving to the owner that he is a good mouser. With no regard for his friendship and Jerry’s good deed, Tom drops Jerry off the roof, giving Jerry no more acknowledgement than to wave bye-bye, Within moments, Tom is reclining in the young woman’s lap, accepted into the household and purring like a kitten at the woman’s stroking caresses. Jerry meanwhile finds himself buried in the snowdrift upon Tom’s street home below. He quickly scrambles out of the snow, and again returns to the penthouse via the elevator. The owner has by now retired to bed, and Tom himself sleeps comfortably in the living room, on a plush velvet pillow, with a ready supply within reach of caviar and bon-bons.

Jerry slips past him and over to the owner’s make-up table, where he liberally coats himself in white powder. Then, to set the mood, he darkens the lighting in the room, and puts on the record player an album of eerie music published by the label, “Somber Records”. The music awakens Tom to the sight of Jerry, entering the room in a walk resembling a zombie, ghostly-white. Tom freaks at the thought that he has brought about Jerry’s demise in the snow, and hides trembling inside a kitchen wastebasket, and then behind any furniture he can find, as Jerry “spooks” him. Jerry even rigs up a line fron the ceiling wrapped around his waist, and soars through the air in flight, causing Tom to retreat through a latticed screen, which severs him into segments matching the intricacies of the screen design, like a work of modern op art. Finally, Tom is cornered at the patio door, and steps backward to the roof edge while Jerry continues his relentless slow-motion pursuit of Tom through the snowdrift on the patio floor. Unfortunately, Jerry does not count upon the effects of the snow on his powder covering – and emerges near the roof ledge with his lower half in natural brown, the powder having been washed away. Tom catches on fast, and his expression denotes his raging fury. His sharp claws emerge from his paw like switchblade knives, and he rears back to cut Jerry into ribbons. Jerry realizes the jug is up, and as there is little chance of making an escape on the narrow patio, braces himself to heroically take his medicine. But as Tom’s paw extends backward in preparation for a vicious slash, he is thrown off balance, and the snow covering on the ledge railing below his feet begins to give way. Losing his traction completely, Tom plunges off the roof ledge, taking the same fall that Jerry endured, and landing again among the trash cans on the snowy street. After pulling himself from the snow, Tom again grabs am empty bottle and a piece of paper, and sails another message up to Jerry. The new note, much as before, states, “Help! It’s freezing down here. Your old pal, Tom.” Instead of another elevator ride, Jerry calmly but determinedly walks back into the apartment, then returns to the patio ledge, tossing over the edge a parting gift for Tom – a pair of ice skates, and a hockey stick! (His owner obviously has some unusual athletic abilities.) The friendship is thus officially dissolved, and Jerry settles back comfortably in bed as the words “The End” appear.

Aqua Duck (Warner, Daffy Duck, 9/28/63 – Robert McKimson, dir.) – As one of our readers surmised last week, extreme heat is again exploited, without the need for a good deal of special effects animation. John Dunn provides the script, and, for all intents ad purposes, this film looks like a dress-rehearsal for the DePatie-Freleng studios that were to be. It is a pity that the rather dreary Bill Lava score, and a read by Mel Blanc that sounds overly-weary and well past Mel’s prime at voicing Daffy, work to greatly diminish the impact of a somewhat surreal script that actually had some good concepts behind it, and feels like it might have come out as something much more memorable in better or younger hands. Daffy is lost in the desert, and parched with thirst. Seeing what he believes to be a lake, he dives in, scooping up handfuls of the “fluid” into his mouth – only to find they are the usual sand, and the lake a mirage. As reality hits Daffy, he decides the only way he is going to find water is dig for it. He begins tunneling deep into the sand, until his hand clanks on something metallic. The unexpected object? A large gold nugget. A younger Daffy would have broken into over-the-top “Woo Woo” hysterics at the sight of the nugget, but Daffy’s glee is disappointingly subdued by comparison. Nevertheless, he realizes he has enough gold here to buy Lake Erie – the only problem being, how to safeguard it. Daffy begins pacing out a zig-zagging path between various desert objects, attempting to map out a secret spot for burying the nugget. He overlooks the fact that one of the landmarks on his map is a live and observant pack rat, who is watching his every move. Daffy finds a choice spot, buries the nugget, and with a convenient paint can, paints an X on the ground to mark the spot. He even goes through the trouble of drawing a map of his route, memorizing it, then chewing up the map to leave no trace. However, by the time he looks down again at his feet, the terrain has changed. While map-making, his paint can has been spirited away by a small lump of ground formed by something tunneling under the sand, and now the paint has been used to surround the ground about Daffy with thirty-or-so duplicate painted X’s. “I’ve been sabotaged”, growls Daffy. The duck then notices one of the X’s begin to move, slowly sneaking away on a mound of sand. Daffy produces a revolver, and points it at the moving mound. From below ground emerges the pack rat, who first tries to swap Daffy an old bone, but is ultimately forced at gunpoint to surrender Daffy’s nugget.

Aqua Duck (Warner, Daffy Duck, 9/28/63 – Robert McKimson, dir.) – As one of our readers surmised last week, extreme heat is again exploited, without the need for a good deal of special effects animation. John Dunn provides the script, and, for all intents ad purposes, this film looks like a dress-rehearsal for the DePatie-Freleng studios that were to be. It is a pity that the rather dreary Bill Lava score, and a read by Mel Blanc that sounds overly-weary and well past Mel’s prime at voicing Daffy, work to greatly diminish the impact of a somewhat surreal script that actually had some good concepts behind it, and feels like it might have come out as something much more memorable in better or younger hands. Daffy is lost in the desert, and parched with thirst. Seeing what he believes to be a lake, he dives in, scooping up handfuls of the “fluid” into his mouth – only to find they are the usual sand, and the lake a mirage. As reality hits Daffy, he decides the only way he is going to find water is dig for it. He begins tunneling deep into the sand, until his hand clanks on something metallic. The unexpected object? A large gold nugget. A younger Daffy would have broken into over-the-top “Woo Woo” hysterics at the sight of the nugget, but Daffy’s glee is disappointingly subdued by comparison. Nevertheless, he realizes he has enough gold here to buy Lake Erie – the only problem being, how to safeguard it. Daffy begins pacing out a zig-zagging path between various desert objects, attempting to map out a secret spot for burying the nugget. He overlooks the fact that one of the landmarks on his map is a live and observant pack rat, who is watching his every move. Daffy finds a choice spot, buries the nugget, and with a convenient paint can, paints an X on the ground to mark the spot. He even goes through the trouble of drawing a map of his route, memorizing it, then chewing up the map to leave no trace. However, by the time he looks down again at his feet, the terrain has changed. While map-making, his paint can has been spirited away by a small lump of ground formed by something tunneling under the sand, and now the paint has been used to surround the ground about Daffy with thirty-or-so duplicate painted X’s. “I’ve been sabotaged”, growls Daffy. The duck then notices one of the X’s begin to move, slowly sneaking away on a mound of sand. Daffy produces a revolver, and points it at the moving mound. From below ground emerges the pack rat, who first tries to swap Daffy an old bone, but is ultimately forced at gunpoint to surrender Daffy’s nugget.

Daffy continues on through the desert, but the heat begins to seriously take its toll upon him. Daffy spots a telephone upon a rock, and dashes to it to phone for room service, and a large pitcher of ice water. As he hangs up the receiver, the phone disappears – revealing itself as another mirage. A very real doorway, unmounted to any wall, suddenly appears before Daffy, with someone knocking on its other side. It is the pack rat, who presents himself through the prop door, carrying a pitcher of ice water. The delirious Daffy hands him the nugget as “something for your trouble”, and accepts the water pitcher – then realizes what he has just done. Furious at the nerve of the rat, Daffy tosses the pitcher away, spoiling his drink before obtaining one drop, and grabs back his nugget. From here on, it is to be a battle of the duck’s greed versus his need for liquid refreshment. Daffy’s delirium increases, as he dances with a dancing partner that is a cactus, then finds instead of natural water inside the pack rat, still offering him a tall, cool glass. At one point, Daffy believes he is in a saloon, buying a round of drinks for all the boys with his gold nugget. He orders and takes a large gulp from an imaginary drink on an invisible bar from the saloon’s invisible bartender – then accuses the bartender of having “watered” it. His chest feathers are suddenly pulled forward, as if someone twice his size was holding him in a firm nose-to-nose grip, and Daffy remarks to this affront, “What do you mean, ‘Smile, when I say that’?” (Reference to a famous line attributed to Western actor Gary Cooper.) Again, sadly, the impact of this clever line is largely undermined by Mel’s lackluster read, and weak direction, and one can only imagine how well the same line might have scored in Chuck Jones’ hands in the days of “Drip Along Daffy”. The pack rat keeps appearing periodically with that tempting glass of water, but Daffy holds out, enduring further far-out mirages where he imagines himself a baseball player, then waiting for a cross-town bus, and then a steamship. Ultimately, the heat prevails, and Daffy’s whole form disintegrates into a powder. His voice is still heard, stating, “Anyone for instant duck? Just add water.” The pack rat appears on cue, pouring a few drops from his glass upon the powder pile, transforming dehydrated Daffy back to his usual self. Daffy reluctantly gives in, and sacrifices his nugget to the pack rat in exchange for the glass of water. It may be expensive, but Daffy at last realizes he made the right trade – or so he thinks, as the circumstances abruptly change. A thunderclap is heard, and within seconds, the desert is covered by a flash flood of water up to Daffy’s waist. We expect the duck to die from frustration at having needlessly squandered his gold nugget. But Daffy closes the film by looking at things in an unexpectedly different way. “When I buy water, I get my money’s worth”, he declares, happily downing his glass of the life-sustaining fluid for the fade out. A script that probably read twice as funny on storyboard as the film it yielded. Dunn deserves his credit, but might have fairly claimed “sabotage” to his work as rightly as Daffy, given the state of the final product.

Daffy continues on through the desert, but the heat begins to seriously take its toll upon him. Daffy spots a telephone upon a rock, and dashes to it to phone for room service, and a large pitcher of ice water. As he hangs up the receiver, the phone disappears – revealing itself as another mirage. A very real doorway, unmounted to any wall, suddenly appears before Daffy, with someone knocking on its other side. It is the pack rat, who presents himself through the prop door, carrying a pitcher of ice water. The delirious Daffy hands him the nugget as “something for your trouble”, and accepts the water pitcher – then realizes what he has just done. Furious at the nerve of the rat, Daffy tosses the pitcher away, spoiling his drink before obtaining one drop, and grabs back his nugget. From here on, it is to be a battle of the duck’s greed versus his need for liquid refreshment. Daffy’s delirium increases, as he dances with a dancing partner that is a cactus, then finds instead of natural water inside the pack rat, still offering him a tall, cool glass. At one point, Daffy believes he is in a saloon, buying a round of drinks for all the boys with his gold nugget. He orders and takes a large gulp from an imaginary drink on an invisible bar from the saloon’s invisible bartender – then accuses the bartender of having “watered” it. His chest feathers are suddenly pulled forward, as if someone twice his size was holding him in a firm nose-to-nose grip, and Daffy remarks to this affront, “What do you mean, ‘Smile, when I say that’?” (Reference to a famous line attributed to Western actor Gary Cooper.) Again, sadly, the impact of this clever line is largely undermined by Mel’s lackluster read, and weak direction, and one can only imagine how well the same line might have scored in Chuck Jones’ hands in the days of “Drip Along Daffy”. The pack rat keeps appearing periodically with that tempting glass of water, but Daffy holds out, enduring further far-out mirages where he imagines himself a baseball player, then waiting for a cross-town bus, and then a steamship. Ultimately, the heat prevails, and Daffy’s whole form disintegrates into a powder. His voice is still heard, stating, “Anyone for instant duck? Just add water.” The pack rat appears on cue, pouring a few drops from his glass upon the powder pile, transforming dehydrated Daffy back to his usual self. Daffy reluctantly gives in, and sacrifices his nugget to the pack rat in exchange for the glass of water. It may be expensive, but Daffy at last realizes he made the right trade – or so he thinks, as the circumstances abruptly change. A thunderclap is heard, and within seconds, the desert is covered by a flash flood of water up to Daffy’s waist. We expect the duck to die from frustration at having needlessly squandered his gold nugget. But Daffy closes the film by looking at things in an unexpectedly different way. “When I buy water, I get my money’s worth”, he declares, happily downing his glass of the life-sustaining fluid for the fade out. A script that probably read twice as funny on storyboard as the film it yielded. Dunn deserves his credit, but might have fairly claimed “sabotage” to his work as rightly as Daffy, given the state of the final product.

More from the last days of the theatrical shorts, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Very interesting titles fully described here. Such a shame that there aren’t links to the cartoons to watch, but many of them are on home video. I especially like the unpredictable and bizarre Tom and Jerry titles here. Whenever I read about these, I wonder how their original creators would have handled this back in the gloriously animated MGM days. That is not to scoff at these cartoons or the others in this particular series. They are an acquired taste, I will grant you.

There are links to all of them, Kevin.

Fancy that: two cartoons in the same post mentioning lobster thermidor….

I had never seen “Noah’s Ark” and “Windwagon Smith” before, never even heard of them, and had no idea that Disney ever made films anything like that. The studio must have allowed greater latitude for stylistic and technical experimentation at that time than they ever had previously. Very impressive stuff; I’ll definitely have another look at both of them later.

The escutcheon on the wall of the mad scientist’s castle in “Franken-Stymied” has a bar sinister — that is, a diagonal red stripe — indicating the family’s descent on an illegitimate line. I wonder if he’s any relation to Simon.

It’s true that Mel Blanc’s performance in “Aqua Duck” falls far short of his usual standard. But, given the release date of 1963, I have to wonder if it might have been recorded during the months of convalescence following his 1961 automobile accident, when he had to deliver his lines while lying flat on his back in bed at home. Blanc’s work in season 2 of The Flintstones is superb; maybe Joe Barbera was able to coax better performances out of him than McKimson bothered to do.

Noah’s Ark was included on the Wonderful World Of Disney episode “A Rag A Bone A Box Of Junk” (1964) ,

The Saga Of Windwagon Smith aired on The New Mickey Mouse Club (1977)

“Windwagon Smith” was a sort of last stand by director Charles August Nichols to convince Walt Disney to keep making animated featurettes at a point when the financial returns no longer justified the expense. Nichols successfully demonstrated how a good cartoon featurette could still be made, on budget and on schedule, with this example. But Walt allegedly told Nichols that hated the UPA style in the picture and that was that. Nichols’ unit was disbanded and he soon left Disney for Hanna-Barbera, where he remained for a couple of decades, followed by a solid staff tenure at Ruby-Spears Enterprises. Nichols ended his very long career at Disney TV Animation, where he was affectionately known as “Nick” Nichols.

I love (most) all of these except Aqua Duck.

An afterthought I can’t resist tossing out for thought. “Aqua Duck” seems so much like a DePatie-Freleng cartoon, one can only wonder (though some tweaking would have been necessary to somehow place the character in the geographic setting) how much funnier and more acceptable a version of the film might have been if made starring Pat Harrington, Jr. as the Inspector. His reads, and a Mancini music score, would seem a natural to have put the cartoon over. The backgrounds and pack-rat animation wouldn’t have had to change at all.

The backgrounds in AD are more painterly than The Inspector shorts, whose BGs are more akin to those used in 101 Dalmatians which employed Xeroxed line drawings over areas of solid color (Although the Inspector ones are much more stylized).

Another afterthought, regarding Windwagon Smith and maritime law, If we are to assume that Smith and Molly are somehow still alive in the Windwagon after decades, what have they been doing all these years? There was no benefit of clergy before they sailed. Would the Windwagon classify as enough of an ocean-going vessel to give Smith Captain’s power to perform marriages? And even if so, under maritime law, could a Captain perform a wedding ceremony upon himself? Could these unanswered questions pose the possibility of some taboo-breaking – in, of all things, a Disney cartoon? I thought this kind of controversy didn’t develop until at least the production of Tarzan!

As long as we’re overthinking things, I want to play, too!

I don’t think maritime law applies to wind-powered vehicles on land or in the air, any more than it would to a boat being towed along a highway on a trailer, and therefore would have no bearing on the union of Windwagon Smith and Molly Crum. However, history provides an authentic example of a Smith marrying a Crum in the American West during the mid-19th century, which I think bears examining here.

In 1847 Lewis Crum Bidamon, who was not an admiral but an officer in the Illinois Militia, married Emma Smith, the widow of Mormon Church founder Joseph Smith, who had been murdered by an angry mob in 1844. Lewis was one of the militiamen who defended the Mormons against persecution in the aftermath of Smith’s death, though he never converted and by all accounts was not particularly religious. Lewis and Emma, who both had children from previous marriages, declined to join Brigham Young and his followers on their trek to Utah Territory and remained in Illinois for the rest of their lives. Emma’s sons by Smith were among the founders of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, which, unlike the Salt Lake City branch, has never sanctioned polygamy of racial discrimination.

I suggest that Windwagon Smith, whether or not a relation of Joseph, may have been the prophet of a Mormon splinter sect (there were several that emerged in the succession crisis following Joseph Smith’s murder) intent on leading his followers to the promised land of Santa Fe. Of course Smith and Molly couldn’t maintain a corporeal existence in the sky for so many years; they would have perished either when the windwagon crashed to the ground, or after they ran out of provisions. The fact that they can still be seen in the western sky suggests that they entered into what the LDS church calls a sealed or celestial marriage, which, unlike a civil marriage that ends upon the death of one spouse, endures throughout eternity. That explains why they still look so young and vital even when their contemporaries down on Earth have aged. Nowadays the sealing ordinance has to take place inside a temple under a specific church authority, but in the early days the details of the sacraments had yet to be fully worked out. There was nothing to prevent a prophet from conducting his own wedding ceremony, as long as he received a revelation from God telling him he could do so. Who knows, maybe the angel Moroni himself officiated. Anything’s possible in cartoons, or in Mormon theology.

As it happens, director Charles August Nichols and production design Ernest Nordli were both born in Utah, though I don’t know if they were raised in the Mormon faith. Now I’m wondering if Don Bluth worked on this film….

“Aqua Duck” at least tries to revive elements of the early zany Daffy (he even whoops at one point), but the limited animation and slow pacing defeat the effort.

Maurice Noble is said to have done some uncredited work in the early 1960s McKimson unit, and “Aqua Duck” looks like a prime example. The vegetation (apart from the ordinary cactus tree Daffy dances with) and backgrounds look good enough for a Salvador Dali painting, and lend this cartoon the parched atmosphere it needs.