The craze of toons for trailers continues, possibly hitting its ultimate expression below. Meanwhile, a new series of exotic locales takes center stage, as Tex Avery and other perfect a formula lampooning the success of a rival studio in a new Tecnicolor medium – the theatrical travelogue.

The Rest Resort (Lantz/Universal, Meany, Miney, and Moe, 8/23/37) – Walter Lantz’s 3 Stooges-inspired simian trio are found as proprietors of a rickety Western hotel called the “Lazy Lodge – Paradise for Rest.” Well, it works for them, as they spend most of their day sound asleep. Until a mother elephant drives into town looking for relaxation. She obviously didn’t read up on the travel brochures, as she is surprised by a prominent sign outside announcing a policy of the house – “No Children Allowed”. Having driven all this way, she’s not about to let this spoil her plans – and has her comparatively small but nevertheless portly son hide in a large steamer trunk on the luggage rack of the car. (He puts his “trunk” in the trunk.) She enters the hotel and haughtily rings for service. Meany awakens, and sets to escort the lady to her room, while directing Miney and Moe to bring in the trunk. Meany’s efforts are stopped cold when Mama gets stuck in one of the hotel doorways, leading to a series of running gags as Meany tries various ideas to unlodge her from the lodge – including an auto jack mounted at a 45 degree angle, which collapses back under the weight of Mama’s hefty bottom.

Meanwhile, bellboys Miney and Moe struggle and strain over the heaviest trunk they’ve ever tried to lift. At one point, they exert all their might to raise the handles on opposite sides of the trunk – only to have both handles break off. They try tipping the trunk, only causing it to roll end over end, hit a tree, and roll back. Junior starts to wriggle around inside, but our heroes quiet him by bashing the trunk with a club. Finally, Miney succeeds in pushing the trunk onto Moe’s back, offering him nothing for help but the touch of a single hand at the front end. Junior starts getting aggressive, sticks his trunk out the lid, and snaps Moe’s tail like an elastic band. A sledge hammer blow is delivered to Miney. Junior then escapes the trunk, and in another room finds a basket of eggs. Taking a heaping handful of them, he stuffs them into his cheeks, then proceeds to use his trunk as an egg-shooting machine gun. Miney and Moe duck for cover, and while Moe attempts to misdirect fire by placing his hat on his tail as a decoy while peering around a wall at low level, takes a surprise direct hit right in the face. Miney creeps up on junior’s trunk (extended through a hole in a wall) and comes up with the solution to be rid of these pests – inserting a wind-up toy mouse into Junior’s trunk. Junior exhales the toy rodent, and runs in a panic for Mama. Mama dislodges herself and, at the sight of an elephant’s worst nightmare, hauls Junior back to the car, where they take off for parts unknown. Despite both front windows of the hotel doors being broken from the egg barrage, Meany places a padlock across the doors, and a sign is hung across them, reading, “Closed – Gone Away For Rest.”

Meanwhile, bellboys Miney and Moe struggle and strain over the heaviest trunk they’ve ever tried to lift. At one point, they exert all their might to raise the handles on opposite sides of the trunk – only to have both handles break off. They try tipping the trunk, only causing it to roll end over end, hit a tree, and roll back. Junior starts to wriggle around inside, but our heroes quiet him by bashing the trunk with a club. Finally, Miney succeeds in pushing the trunk onto Moe’s back, offering him nothing for help but the touch of a single hand at the front end. Junior starts getting aggressive, sticks his trunk out the lid, and snaps Moe’s tail like an elastic band. A sledge hammer blow is delivered to Miney. Junior then escapes the trunk, and in another room finds a basket of eggs. Taking a heaping handful of them, he stuffs them into his cheeks, then proceeds to use his trunk as an egg-shooting machine gun. Miney and Moe duck for cover, and while Moe attempts to misdirect fire by placing his hat on his tail as a decoy while peering around a wall at low level, takes a surprise direct hit right in the face. Miney creeps up on junior’s trunk (extended through a hole in a wall) and comes up with the solution to be rid of these pests – inserting a wind-up toy mouse into Junior’s trunk. Junior exhales the toy rodent, and runs in a panic for Mama. Mama dislodges herself and, at the sight of an elephant’s worst nightmare, hauls Junior back to the car, where they take off for parts unknown. Despite both front windows of the hotel doors being broken from the egg barrage, Meany places a padlock across the doors, and a sign is hung across them, reading, “Closed – Gone Away For Rest.”

Hawaiian Holiday (Disney/RKO, Mickey Mouse, 9/24/37 – Ben Sharpsteen, dir.) is a landmark in several respects. It is one of the few “all star” episodes ever produced by the Disney studios, featuring not just Mickey, Donald, and Goofy, but Minnie and Pluto too. (On Ice (1035), and brief cameos in Pluto’s Christmas Tree (1952), are I believe the only other instances in which the “big five” appeared together in the golden age.) It was the initial release for Disney under his new and longest-lasting distribution deal with RKO Radio Pictures. And it was rumored to be the animation debut for the studio of “Woolie” Wolfgang Reitherman – and one in which he would express pride in his later days.

Plotwise, there’s actually not much to speak of, as the film is merely an intersecting stream of episodic vignettes of the respective stars’ various activities while they take a break from their busy studio routine in the paradise islands. But Reitherman and crew make the most of the material, producing an episode of such lasting appeal, it has remained constantly in print in virtually all video formats since the days Disney first established its own in-house 8mm home movie distribution, and was included in the first wave of releases both in 8mm and on later Betamax and VHS video tape.

Plotwise, there’s actually not much to speak of, as the film is merely an intersecting stream of episodic vignettes of the respective stars’ various activities while they take a break from their busy studio routine in the paradise islands. But Reitherman and crew make the most of the material, producing an episode of such lasting appeal, it has remained constantly in print in virtually all video formats since the days Disney first established its own in-house 8mm home movie distribution, and was included in the first wave of releases both in 8mm and on later Betamax and VHS video tape.

Segments include: (1) Minnie dancing hula to a dexterous demonstration of ukelele playing by Mickey, with his four-digit hands assuming the poses of dancers on the ukulele strings; (2) Donald joining the hula in grass skirt, but getting too close to the cooking fire for their lunch, and setting his foliage ablaze; (3) Pluto in beachfront encounters first with a starfish, then a crab (in a design which notably, would be ripped off nearly verbatim by Rudolf Ising for his return to MGM in The Little Goldfish (1939)), always resulting in Pluto buried in the sand by the impact of the crashing waves; and (4) In the most memorable segments of all, Goofy attempting to conquer his first “sport”, as he tries his hand (or is it toes) at surfing. The surf gags do more to transform mere water into a real personality than perhaps was accomplished in any other cartoon (an idea only crudely attempted in such films as Krazy Kat’s Honolulu Wiles (1930) and Fleischer’s Swim or Sink and Is My Palm Read (reviewed last week) and Popeye’s Shiver Me Timbers (1934), to name a few), with the water proving a perfect foil for Goofy, anticipating his every move and outwitting him time and again, leaving him to take the pratfalls. Finally, using Goofy’s own surfboard as a bat, the wave knocks Goofy for a home run, burying him under the beach sand and planting Goofy’s board above the grave as a commemorative headstone. (Of course, the Goof’s not really dead, and pops out long enough for his trademark “Gawsh”, as we iris out.)

Zula Hula (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 12/24/37 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Thomas Johnson/Frank Endres, anim.) – Betty and Grampy enjoy an unusual leisure jaunt in Grampy’s private plane – when their outing is interrupted by a lightning storm – landing fist-shaped blows on their craft. Betty asks if there’s something wrong with the altitude. Grampy states that the engine’s missing. “Then why didn’t you bring it along?”, imquires Betty. Another lightning bolt reaches into the cockput and grabs away the steering column, and another transforms into a pair of scissors, cutting off the wings. The plane falls in a steep dive – but of course inventor Grampy is prepared for just such an emergency. A simple pull of a lever, and a huge umbrella opens from the top of the plane, floating it down like a parachute to safety upon an island below. The two unpack supplies, while Betty comments that she hopes they have a beauty parlor because she needs a shampoo. Grampy recruits the local wildlife to assist in building shelter – using a swordfish to cut bamboo, and a woodpecker to drill holes for nails. He supplies fresh coconut milk dispensed from the shell with the nozzle of a seltzer bottle. And he provides a gentle breeze with a contraption using a large palm leaf for a fan, tied to a pivoting pole where two seagulls play tug of war over a fish tied to the center pole. But their every move is watched by typical 1930’s politically incorrect cannibal natives (accounting for the comparative scarcity of this title among Grampy episodes). As usual, Grampy dons his mortarboard thinking cap for a solution – with one unusual twist, as a cannibal spear breaks the light bulb on top of the cap, causing Grampy to pause to install a new bulb. In accordance with the typical formula for Grampy episodes, everuthing can be solved with a music machine – which Grampy makes out of the plane’s engine, installing bamboo reeds to the exhaust system as flutes. A pulley extends from the motor to a rotating pole on a tree, to which drumming devices have been fastened to beat out time on the belly of a turtle. The natives happily dance in wild frenzy – giving Grampy time to build a new smaller makeshift autogyro for he and Betty to make their escape – with propeller powered by a ladder-style belt where a monkey endlessly climbs in hopeless effort to reach a bunch of bananas suspended above him.

Zula Hula (Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 12/24/37 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Thomas Johnson/Frank Endres, anim.) – Betty and Grampy enjoy an unusual leisure jaunt in Grampy’s private plane – when their outing is interrupted by a lightning storm – landing fist-shaped blows on their craft. Betty asks if there’s something wrong with the altitude. Grampy states that the engine’s missing. “Then why didn’t you bring it along?”, imquires Betty. Another lightning bolt reaches into the cockput and grabs away the steering column, and another transforms into a pair of scissors, cutting off the wings. The plane falls in a steep dive – but of course inventor Grampy is prepared for just such an emergency. A simple pull of a lever, and a huge umbrella opens from the top of the plane, floating it down like a parachute to safety upon an island below. The two unpack supplies, while Betty comments that she hopes they have a beauty parlor because she needs a shampoo. Grampy recruits the local wildlife to assist in building shelter – using a swordfish to cut bamboo, and a woodpecker to drill holes for nails. He supplies fresh coconut milk dispensed from the shell with the nozzle of a seltzer bottle. And he provides a gentle breeze with a contraption using a large palm leaf for a fan, tied to a pivoting pole where two seagulls play tug of war over a fish tied to the center pole. But their every move is watched by typical 1930’s politically incorrect cannibal natives (accounting for the comparative scarcity of this title among Grampy episodes). As usual, Grampy dons his mortarboard thinking cap for a solution – with one unusual twist, as a cannibal spear breaks the light bulb on top of the cap, causing Grampy to pause to install a new bulb. In accordance with the typical formula for Grampy episodes, everuthing can be solved with a music machine – which Grampy makes out of the plane’s engine, installing bamboo reeds to the exhaust system as flutes. A pulley extends from the motor to a rotating pole on a tree, to which drumming devices have been fastened to beat out time on the belly of a turtle. The natives happily dance in wild frenzy – giving Grampy time to build a new smaller makeshift autogyro for he and Betty to make their escape – with propeller powered by a ladder-style belt where a monkey endlessly climbs in hopeless effort to reach a bunch of bananas suspended above him.

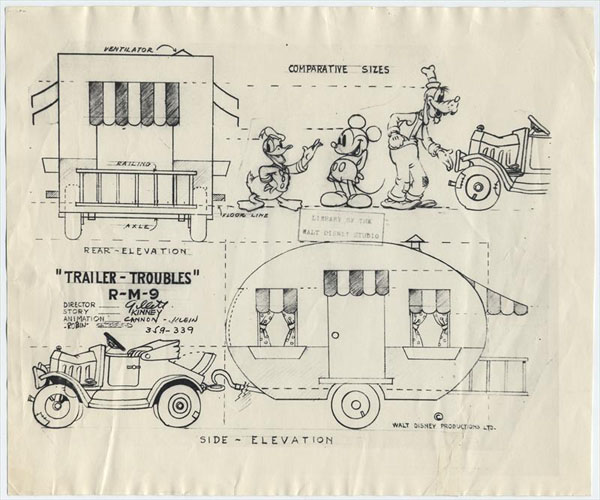

Mickey’s Trailer (Disney/RKO, Mickey Mouse, 5/6/38 – Ben Sharpsteen, dir.) – Well, every other character in Hollywood seemed to be getting a futuristic trailer. Why not Mickey? While some of the situations to be described below are definitely familiar from the descriptions of Scrappy, Oswald, and Farmer Al Falfa episodes discussed in last week’s column, Disney’s version as usual comes out smelling like a rose by comparison – thanks to the typical studio advantages of flawless animation, attention to detail, well-defined character personalities welcomed by audiences as old friends, and an impeccable sense of comic timing, where gags are savored and developed instead of thrown away in haphazard fashion.

Mickey’s Trailer (Disney/RKO, Mickey Mouse, 5/6/38 – Ben Sharpsteen, dir.) – Well, every other character in Hollywood seemed to be getting a futuristic trailer. Why not Mickey? While some of the situations to be described below are definitely familiar from the descriptions of Scrappy, Oswald, and Farmer Al Falfa episodes discussed in last week’s column, Disney’s version as usual comes out smelling like a rose by comparison – thanks to the typical studio advantages of flawless animation, attention to detail, well-defined character personalities welcomed by audiences as old friends, and an impeccable sense of comic timing, where gags are savored and developed instead of thrown away in haphazard fashion.

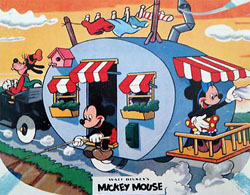

Our scene opens on what appear to be a full-featured house nestled in a scenic region of mountains and lakes, complete with picket fence, lawn, trees and shrubbery, arched entryway, and birdhouse. Mickey appears on the porch in nightcap and nightshirt, commenting, “Oh boy! What a day!”, then pulls a large lever on the porch. Everything begins to disappear! Angled roof folds up and into what is in fact the trailer below (standard oval model, with awnings). Fencing and archway collapse like a closing telephone extender. Trees and shrubbery deflate, and lawn rolls up. The front wall of the trailer lowers, and out from inside rolls a sleeping Goofy in a Model T Ford. So far, quite similar to Scrappy’s Trailer. Then, the crowning topper. The blue skies, mountains and lake all fold up like a fan – being on a painted backdrop, revealing their true surroundings – a smoggy city dump!

At a pull on a bell cord like a streetcar conductor, Mickey signals Goofy to commence towing. Goofy steers the trailer onto a country road, to his melodious (??) strains of “She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain”. Inside, Mickey fixes lunch, with aome free assists from local farmers and mother nature. Bu merely leaning out the window, Mickey retrieves fresh water from a waterfall, and ears of corn from a farmer’s field. Goofy lends a hand in obtaining milk, holding out a handful of hay to a cow on the side of the road, getting her to chase the car, while Mickey milks her from out the window. Meanwhile, Donald Duck is sleeping in late. An alarm clock with an axle and spool attached into its rear workings sounds off, the spool winding Donald’s blanket up and slapping his feet with it on each rotation.

Donald is still droopy, but Mickey knows the remedy for that. With a push of a button, Donald’s bunk folds out from under him, and the wall flips, changing into a sink and mirror. Under Donald sprouts a flexible contraption with zipper, which Donald unzips into a bathtub! Donald is ready for this, wearing a bathing-suit top under his nightshirt. After a leisurely bath (except for a flock of birds peering in at him), another press of a button fold up the bathroom and Donald into the wall, changing the area into a breakfast nook, with Donald emerging from a chute dressed in his usual sailor suit. Mickey enters with corn, milk, coffee, potatoes, and watermelon, and rings a dinner bell for Goofy to come inside. Goofy responds to the mess call – but makes a mess of things in the process, completely forgetting to shut off the car, which continues down the road, and right through a “Road Closed” sign. Inside, the bumpy road causes Goofy several mishaps with lunch. First, his potato flips into a cabinet drawer so he can’t find it. Goofy’s slice of watermelon is squished onto his face by two dawers, and he “shaves” the goop off with a butter knife. Goofy’s fork gets stuck in an ear of corn, and in pulling it out, Goofy sticks the fork into an electric socket, transforming the ear in his other hand into popcorn. By now, the trailer has ventured onto a thin and winding mountain road. “Hey, who’s driving?”, Mickey and Donald finally observe. “Why I’m driving”, Goofy responds – then suddenly realizes what he is saying. He scrambles out the window to regain control of the steering wheel, struggling for footing on the car’s trunk – and dislodges the trailer hitch. Without a tow, the trailer rolls backward at ever increasing pace down the mountain road. Oblivious to everything, and now over the hump, Goofy at the wheel hollers back to where he thinks his pals are, reassuring them, “The worst is over. It’s all downhill from here.”

Donald is still droopy, but Mickey knows the remedy for that. With a push of a button, Donald’s bunk folds out from under him, and the wall flips, changing into a sink and mirror. Under Donald sprouts a flexible contraption with zipper, which Donald unzips into a bathtub! Donald is ready for this, wearing a bathing-suit top under his nightshirt. After a leisurely bath (except for a flock of birds peering in at him), another press of a button fold up the bathroom and Donald into the wall, changing the area into a breakfast nook, with Donald emerging from a chute dressed in his usual sailor suit. Mickey enters with corn, milk, coffee, potatoes, and watermelon, and rings a dinner bell for Goofy to come inside. Goofy responds to the mess call – but makes a mess of things in the process, completely forgetting to shut off the car, which continues down the road, and right through a “Road Closed” sign. Inside, the bumpy road causes Goofy several mishaps with lunch. First, his potato flips into a cabinet drawer so he can’t find it. Goofy’s slice of watermelon is squished onto his face by two dawers, and he “shaves” the goop off with a butter knife. Goofy’s fork gets stuck in an ear of corn, and in pulling it out, Goofy sticks the fork into an electric socket, transforming the ear in his other hand into popcorn. By now, the trailer has ventured onto a thin and winding mountain road. “Hey, who’s driving?”, Mickey and Donald finally observe. “Why I’m driving”, Goofy responds – then suddenly realizes what he is saying. He scrambles out the window to regain control of the steering wheel, struggling for footing on the car’s trunk – and dislodges the trailer hitch. Without a tow, the trailer rolls backward at ever increasing pace down the mountain road. Oblivious to everything, and now over the hump, Goofy at the wheel hollers back to where he thinks his pals are, reassuring them, “The worst is over. It’s all downhill from here.”

Inside the trailer, things are a panicked shambles. As with Oopie and Oswald, Mickey and Donald bounce around like ping pong balls, while everything in the trailer transforms into everything else. Mickey barely keeps the trailer from running off the road by jumping out the window and pushing the trailer back onto the roadway from a footing on an opposite cliff. Donald has a telephone pop out in his face from a cabinet, and tries to call for help. His call becomes more frantic as the phone launches out the window on an extender, dangling Donald over a precipice. Then, the sound of a train whistle is heard. Below lies a junction, with a long and speeding freight train approaching around a bend. “Get out of the way!” shouts Donald, then reverts to prayers. With precision timing, the trailer slips through the crossing a split second ahead of the train. Then, in classic slapstick fashion, the gag is magnified, as Mickey and Donald hear the train whistle again. The track has curved back across the road, and the train is now ahead of them, already in the next junction. As train car after train car passes, the trailer reaches collision point – just as the last car clears the track, and the trailer gets through again unscathed. But the trailer finally runs out of road, jumping a chasm and landing on an opposite hill upside down, boucning and rolling over and over, while Mickey and Donald run inside amidst flying debris like hamsters in a wheel. The scene dissolves to a cheery Goofy, now on flat road, singing again. From the hill alongside the road rolls the trailer, flipping upright on its final bounce to rehitch itself to the Model T. As Mickey and Donald look up helplessly from the devastation inside, Goofy can only say, “Well, I brought ya down, safe and sound.”

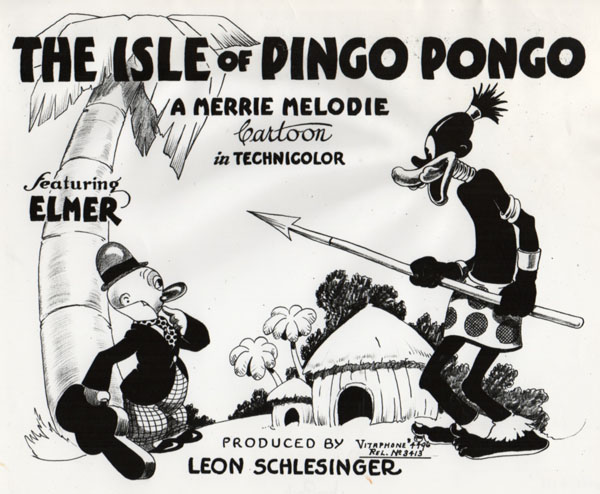

The Isle of Pingo Pongo (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 5/28/38 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – James A Fitzpatrick was not the only producer of theatrical travelogues – but he seems to have become the most prolific, and definitely the most well remembered. He had been kicking around in the business for years when he produced his first travel picture in 1930. He himself would provide narration, leading to the series title, “Fitzpatrick Traveltalks”. The films were provided some unusual flavor, despite his own rather stoic approach to narration, by the regular use of top orchestras to provide musical scores themed to the locale in question (early episodes, for example, used Victor Records’ house musical director Nat Shilkret and his relative (brother?) Jack Shilkret in many instances). And, when Technicolor became available, Fitzpatrick was one of the first to champion its use, converting to full color in 1934. This move cemented his place at the forefront of the travelogue industry, under the top-flight distribution of MGM, where he would remain until well into the 1950’s.

Of course, when you produce a successful film genre, you can expect that the animation industry will find a way to provide a lampoon. Enter Tex Avery, who was still looking for a regular series or formula of his own capable of drawing studio recognition. He had introduced Daffy Duck, probably with no more expectation than that he would be an interesting one-shot flash in the pan. When the studio asked for more, he may have been at a bit of a loss for new ideas – producing only two more cartoons himself (“Daffy Duck and Egghead”, and “Daffy Duck in Hollywood”), then relinquishing the character to Chuck Jones for one early episode, and ultimately back to black and white in Bob Clampett’s Looney Tunes. He would also work with the reigning established characters of the studios he worked for (Oswald for Lantz, and Porky for Warners), but may have also felt uneasy in these waters, in that, wherever he went in his career, until the successful creation of Droopy, he always seemed to gravitate to the niche of producing “one-shots” – non-series cartoons about different characters or situations each time. Possibly, he felt this gave him more artistic freedom – the chance to build an episode around any wild or random gag situation he could think up, without being regimented into one character’s book of rules and personality traits. However it occurred, the one-shot became Avery’s stock in trade, and he would be the go-to man at both Warners and MGM for as many miscellaneous episodes as were needed to fill an annual production schedule, between other animators’ labors to try to find new things to do for their established characters.

But even a “one-shot” director needs inspiration. Random ideas are fine – but they don’t always come on cue. Even if the subject matter differs from film to film, a formula is always helpful to get a project started when a production deadline looms. Avery would realize this even late in his career (regularly falling back in his MGM days upon a recurring formula of filling in the blank on “The —- Of Tomorrow”.) At Warners’, his first such inspiration for a formula was to spoof a movie genre. His target – the Fitzpatrick Traveltalk. A great and open-ended prospect, given the world of travel possibilities for spot gags offered by the myriad of destinations covered in such a travel series. Rather, however, than starting with a real-life travel destination (most of the best of which had already been the locale for one cartoon or another from other series), Avery chose to devise a mythical and nonsensical destination no one had ever seen, not only allowing his imagination to run wild, but allowing the project to be truly his own. Thus, the tropical paradise of Pingo Pongo sprung into existence (a wordplay on the real-life location, Pago Pago).

But even a “one-shot” director needs inspiration. Random ideas are fine – but they don’t always come on cue. Even if the subject matter differs from film to film, a formula is always helpful to get a project started when a production deadline looms. Avery would realize this even late in his career (regularly falling back in his MGM days upon a recurring formula of filling in the blank on “The —- Of Tomorrow”.) At Warners’, his first such inspiration for a formula was to spoof a movie genre. His target – the Fitzpatrick Traveltalk. A great and open-ended prospect, given the world of travel possibilities for spot gags offered by the myriad of destinations covered in such a travel series. Rather, however, than starting with a real-life travel destination (most of the best of which had already been the locale for one cartoon or another from other series), Avery chose to devise a mythical and nonsensical destination no one had ever seen, not only allowing his imagination to run wild, but allowing the project to be truly his own. Thus, the tropical paradise of Pingo Pongo sprung into existence (a wordplay on the real-life location, Pago Pago).

Aboard the S.S. Queen Minnie (which, curiously, would be the same name Mickey Mouse would have Minnie christen his do-it yourself ship in “Boat Builders” in the same year), of the Half Dollsr Lines, we depart from New York. The Statue of Liberty plays a mere traffic signal, its torch alternating between red and green lights, as it rotates to let a speedboat through ocean liner cross-traffic. We get our first use of a map gag showing a “direct course” to the island – looping and zig-zagging between every landmark (a gag to later reappear in “Crazy Cruise”, to be discussed in a subsequent chapter). Passing a sign reading, “Los Angeles City Limits”, we are treated to glimpses of the Canary Islands (abounding in bird cages), the Sandwich Island (inhabited by a giant hamburger on a bun), and the Thousand Islands (with a giant bottle of salad dressing). Enter our running gag – Egghead, carrying a violin case, asking the narrator, “Now?” “No, not now”, replies the narrator.

Pingo Pongo rises suddenly on the horizon – literally popping up from underwater. In its bay, a passenger tosses a coin to natives below. However, the rest of the passengers dive overboard to retrieve the coin before the native can get near it. Several routine spot gags highlight the local bird and wildlife. When the fastest animal on Earth, the Pingo Pongo spotted gazelle, zips by in a blur too fast for the camera, the narrator talks one into letting us have a good look at her – and she parades as if on a fashion show runway. A random shot finds a polar bear and Eskimo, who explain their odd presence by stating “We’re on a vacation. Nyah!”

The primary sequence (which got the cartoon on the Censored 11) takes place in the native village, with more racial stereotypes, at least for the most part comically designed. A quartet of fierce-looking native drummers break from their primitive rhythm into an unexpected hillbilly rendition of “She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain”. At the Dark Brown Derby restaurant, breakfast is served up hot – directly into the plates within a Ubangi’s lips. A native game similar to football is demonstrated, but the quarterback’s numbered signals are merely responded to by one of the linebackers calling, “Bingo”. A final production number gives us a native celebration – beginning unexpectedly oddly with the natives performing a polite European minuet – but kicking into high as a quartet resembling the Mills Brothers and a soloist resembling Fats Waller perform a spirited rendition of “Sweet Georgia Brown”. While milder by comparison, this sequence bears considerable influence from similar production number closing the events in Harman and Ising’s “Swing Wedding” for MGM a few years earlier, with several scenes closing the festivities with dancing abandon.

The primary sequence (which got the cartoon on the Censored 11) takes place in the native village, with more racial stereotypes, at least for the most part comically designed. A quartet of fierce-looking native drummers break from their primitive rhythm into an unexpected hillbilly rendition of “She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain”. At the Dark Brown Derby restaurant, breakfast is served up hot – directly into the plates within a Ubangi’s lips. A native game similar to football is demonstrated, but the quarterback’s numbered signals are merely responded to by one of the linebackers calling, “Bingo”. A final production number gives us a native celebration – beginning unexpectedly oddly with the natives performing a polite European minuet – but kicking into high as a quartet resembling the Mills Brothers and a soloist resembling Fats Waller perform a spirited rendition of “Sweet Georgia Brown”. While milder by comparison, this sequence bears considerable influence from similar production number closing the events in Harman and Ising’s “Swing Wedding” for MGM a few years earlier, with several scenes closing the festivities with dancing abandon.

And now, the memorable closing that lampooned a signature line which became closely associated with the Fitzpatrick series. Though in watching numerous of the Fitzpatrick films recently released on DVD, I’ve yet to encounter the line, a montage which I believe was once featured in one of the “That’s Entertainment” features clipped together about seven instances where Traveltalks ended with the phrase “As the sun sinks slowly in the West, we bid a fond farewell to (fill in the blank).” Avery has hos narrator mimic this line as closely as possible – but the sun doesn’t drop an inch. He repeats the line over and over, but nothing. Egghead appears for about the fifth time in the film. “Now, boss?” “Yes, now”, replies the narrator. Egghead opens his violin case, producing a shotgun, and blasts the sun out of the skies for the iris out.

Travel Squawks (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Krazy Kat, 7/4/38 – Allen Rose/Harry Love, dir.) – One of the only cartoons to directly take off upon the name of the Fitzpatrick series in its tutle, presumably rushed to production in the wake of the success of “Pingo Pongo”. Krazy is unusually verbose in this episode, having to play the role of narrator (in a baritone voice much deeper than usual) as he escorts us on a world tour from aboard a flying carpet. We leave the peace of civilization (where buildings below randomly explode), as Krazy does a quick costume change and takes us in Arctic furs to the North Pole. Penguins board a seal for toboggan-like transportation to an arctic baseball game, payed by seals who balance and toss the ball from their noses. Next stop, Holland. A local gets a clean shave by lathering up, then sticking his head out a mill window, letting the spinning windmill blades do the task. Some kids and a dog demonstrate the local dance, while Krazy comments “Wooden shoe like to dance like this? Get it?” Final stop – Africa. Things go off the deep end here for political incorrectness, at the trial of a female native accused of not having rhythm. Her defense attorney proves her innocent by having her demonstrate her dancing technique, while the jury produces a brass section for accompaniment. While the natives in “Kannibal Kapers”, reviewed last week, were strictly toony in design, the problem with this film is that some of the stereotypes are drawn downright ugly, and quite difficult to watch. Krazy drops down to join in the music (which, believe it or not, turns out to be yet another retread of Joe De Nat’s original, “Ummba Ummba”), and almost gets captured by the natives himself. He of course takes off on the carpet in the nick of time, dumping out the accused female onto the judge’s bench, then waves goodbye and flies off into the sunset. The film fails to successfully parody anything from the MGM series, and barely manages to even pass for a cartoon, being nothing more than a six-minute “programmer” of little note.

We apologize in advance for this copy of the cartoon:

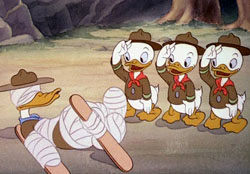

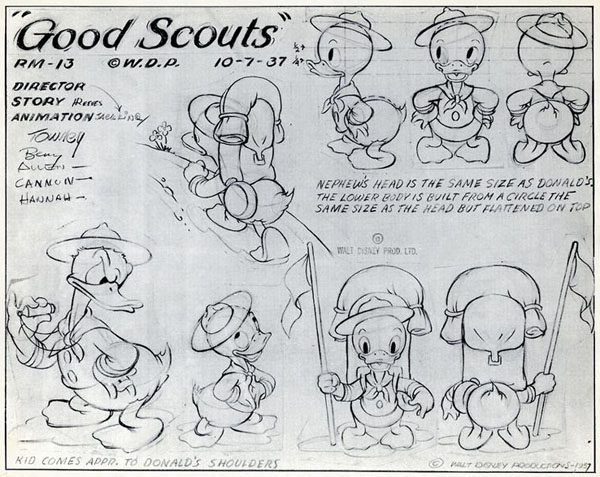

Good Scouts (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 7/8/38 – Jack King, dir.) – As scoutmaster of what Carl Barks would eventually transform into the “Junior Woodchucks”, Donald introduces his nephews for the first time to the thrills of scouting, for a camping excursion into Yellowstone Park. The first thing Donald needs to work on is the kids’ understanding of the term “halt”, as they plow into him from the rear. “Exasperating”, scowls Donald. He orders the kids to make camp. One nephew is in charge of obtaining firewood, but lazily chops at a shrub too small to support any reasonable spark. “You call that a tree?”, Donald scolds. “I’ll show you a man-sized tree.” Behind him looms a forest giant, to which Donald reacts, “Oh boy!”. As he raises his axe, his nephew spots a sign Donald has ignored, reading “Petrified Tree”. No amount of warning will dissuade Donald, who tells him to “Scram! Doggone kids don’t know how to do anything.” The nephew braces for the result, as Donald’s blow puts him into an instant state of shock trembles – right down to the tip of his tail. Meanwhile, the other two nephews are having an equal lack of success pitching the tent, which collapses before they can secure its ropes. Bossy Donald steps in again. “This is the way to tie a knot. When you do a thing, do it right.” He pulls down the end of a springy sapling, and ties it down with an impossible-looking massive knot that seems to combine every hitch in the nomenclature of a sailor into one rope. Tossing the canvas over the bent tree as instant tent, Donald stands proud atop it. Unfortunately, Donald’s prowess with rope has only succeeded in creating the world’s largest slip knot, which completely unravels, launching Donald and the tent across the clearing. Donald lands in a messy pile of their food supplies, splattered with condiments. The kids begin to get the idea that Donald’s no know-it-al, and break into uncontrollable laughter. Donald throws one of his classic tantrums, but spots among the supplies a bottle ot catsup. “I’ll make ‘em sorry”, he mumbles, and splatters gobs of the stuff upon himself, then moans as if wounded. If there’s one thing the nephews have been boning up on for their merit badges, it’s first aid. Grabbing their medical supplies, the nephews, to Donald’s surprise, soon have the angry duck bandaged and splinted in complete traction.

Good Scouts (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 7/8/38 – Jack King, dir.) – As scoutmaster of what Carl Barks would eventually transform into the “Junior Woodchucks”, Donald introduces his nephews for the first time to the thrills of scouting, for a camping excursion into Yellowstone Park. The first thing Donald needs to work on is the kids’ understanding of the term “halt”, as they plow into him from the rear. “Exasperating”, scowls Donald. He orders the kids to make camp. One nephew is in charge of obtaining firewood, but lazily chops at a shrub too small to support any reasonable spark. “You call that a tree?”, Donald scolds. “I’ll show you a man-sized tree.” Behind him looms a forest giant, to which Donald reacts, “Oh boy!”. As he raises his axe, his nephew spots a sign Donald has ignored, reading “Petrified Tree”. No amount of warning will dissuade Donald, who tells him to “Scram! Doggone kids don’t know how to do anything.” The nephew braces for the result, as Donald’s blow puts him into an instant state of shock trembles – right down to the tip of his tail. Meanwhile, the other two nephews are having an equal lack of success pitching the tent, which collapses before they can secure its ropes. Bossy Donald steps in again. “This is the way to tie a knot. When you do a thing, do it right.” He pulls down the end of a springy sapling, and ties it down with an impossible-looking massive knot that seems to combine every hitch in the nomenclature of a sailor into one rope. Tossing the canvas over the bent tree as instant tent, Donald stands proud atop it. Unfortunately, Donald’s prowess with rope has only succeeded in creating the world’s largest slip knot, which completely unravels, launching Donald and the tent across the clearing. Donald lands in a messy pile of their food supplies, splattered with condiments. The kids begin to get the idea that Donald’s no know-it-al, and break into uncontrollable laughter. Donald throws one of his classic tantrums, but spots among the supplies a bottle ot catsup. “I’ll make ‘em sorry”, he mumbles, and splatters gobs of the stuff upon himself, then moans as if wounded. If there’s one thing the nephews have been boning up on for their merit badges, it’s first aid. Grabbing their medical supplies, the nephews, to Donald’s surprise, soon have the angry duck bandaged and splinted in complete traction.

Donald stumbles about on the splints, falling beak-first into an open jar of honey. On the other side of camp prowls a giant grizzly bear (a powerful character design which saw a great deal of use over the course of a few short years, originating in Little Hiawatha (1937), reappearing here, and to have further use in Mickey Moise’s The Pointer (1939) and Donald’s Vacation (to be discussed below). The bear picks up the scent of the honey, and smacks his lips. One growl sends the nephews running, but Donald, with bandages over his eyes, thinks the nephews are clowning around – even when the bear’s tongue tickles Donald into a fit of laughter as he consumes Donald’s honey-coating. “That’s enough!”, shouts Donald, clunking the bear with one of the splints. A roar of twice the magnitude of the previous ones shakes Dona;d’s head bandage off, and Donald cones face-to-face with a reality check. Donald becomes a literal blur as he makes tracks – with one long strip of bandage trailing behind him. The bear bites nto the bandage, unraveling Donald’s remaining wrappings, and sending him spinning off a high cliff. Donald plunges into a canyon below, but is saved from impact by a bandage knot secure around his foot. (Well, the kids learned how to tie knots after all.) The bear, on the cliff edge above, shakes his clenched jaw violently, putting the tremors into the suspended Donald, who blows a small command whistle for help. His troops arrive on a path along the canyon wall. Forming a sort of human-telephone extender via a hand and foot link, the nephews extend themselves out over the gorge, allowing one to cut the bandage with a small knife.

Donald lands with a plop upon soft ground below, with his rear end in a large hole. The bear roars from above, and Donald jeers at him by giving him the raspberry. Suddenly, the ground below rumbles and trembles unexpectedly. Donald spots another sign he should have read: “Old Reliable Geyser – erupts at Twelve o’Clock.” Of course, this is a cue for Donald’s watch to indicate he’s right on time. As Donald folds into a praying position, the geyser erupts, shooting him skyward in a jet of water. Donald again whistles for his scouts. The resourceful nephews grab a long log and attempt to stuff one end of it into the watery hole. But the force of the steamy jet is too great, and the log also shoots up with the flow, catching Donald on the other end. Donald is propelled even higher on the log’s end – right up to the waiting bear on the cliff edge. A sheepish tip of Donald’s hat is not enough to pacify the bear, who takes a swipe at him with a huge paw, knocking Donald back into the water plume. (A curious production note at this point in the story. A continuity script for the film exists in the UCLA Televison and Film library, indicating an additional sequence here which is crossed through in pencil. The nephews were next to try to stuff the geyser with a cactus – which of course would also shoot up and get Donald in the rear end. Probably a Carl Barks gag, knowing his reputation at this time for crazy sight and prop situations. However, some cooler head likely realized that cactus weren’t native to Yellowstone.) So instead, the nephews dislodge a series of boulders, letting them roll onto the geyser hole. Three small boulders fail to do the job, each one being propelled upward to bounce off Donald’s rear. The nephews converge on one mammoth rock, and its substantial tonnage finally plugs the flow of water. Unfortunately, that’s all that Donald was standing on, and he suddenly finds himself going down faster than comfortable. But nature will have its way – rock or no rock, as the pressure builds below. A massive explosion breaks up Old Reliable, blowing away most of the original topsoil, so that the jet of water is now three-times wider, and apparently uncontrollable. The boulder shoots upward, intercepting Donald in mid-fall, and again shooting him back to a level parallel with the still-peeved bear. The bear leaps onto the rock with him, and as Donald begins to run, the boulder develops a rotation like a small planet atop the water jet, providing a revolving surface for the duck and bear to keep on running. For our final scene, the shot dissolves to nighttime, where Huey, Dewey, and Louie rest in their tent lit by the flames of a campfire. They look upward and consecutively call, “Goodnight – Uncle – Donald!” Above, the bear’s pursuit of Donald has not lost steam – nor has the flow of the geyser – as it appears Donald will remain running and whistling well into the dawn.

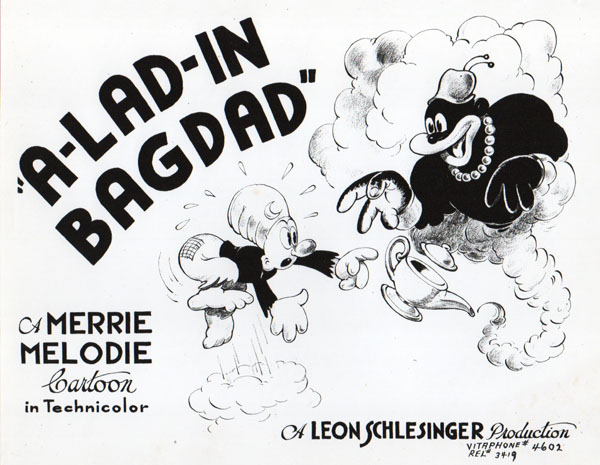

A Lad In Baghdad (Warner, Merrie Melodies (Egghead), 8/27/38 – Cal Howard/Cal Dalton, dir.) – Another film where it’s hard to tell if the lead character is on vacation or not. But Egghead wanders into Arabian Nights territory carrying a bindle stick – the same means of travel used by Sniffles the Mouse for his vacation two years later – so we’ll assume for the sake of argument that he’s a tourist rather than a passing hobo. While viewing the sights, he spots a sheik attempting to win a golden lamp from an arcade claw machine, but getting nothing but candy beans instead. While the sheik wails in frustration, Egghead pops a nickel in the slot, and without even aiming the claw digger, wins the lamp on the first try. “Boy am I lucky. What a terrific sugar bowl”, Egghead observes in his best Joe Penner impression. Directions on the bottom of the lamp instruct him to rub, and the usual genie appears. Egghead wishes himself into some new clothes, then, seeing a poster inviting the cleverest entertainers to compete at the palace for the Sultan’s daughter’s hand, wishes for a magic carpet (delivered complete with outboard motor). Meanwhile the sheik observes all from the shadows, and determines to obtain the lamp for himself.

Ar the palace, line forms at the right for entertainers. A highlight is a singing dio called the “Slap-Happy Boys” – a parody of popular radio and recording stars, Billy Jones and Ernest Hare (The Happiness Boys). As they perform an endless patter-song (“How Do You Do and How Are You?”), the Sultan drops them through a trap door into a pit (a gag which would be reused in Tex Avery’s “Hamateur Nnight”, and remembered over a decade later for Bugs Bunny’s “Hare-abian Nights”). But this time, despite having been dropped into the depths, the boys won’t stop singing – and have to be knocked off one by one with pistol shots from the Sultan himself. Finally, Egghead performs. Musically he’s first rate with a rendition of “Bei Mir Bist Du Schon”. But when he reaches for the lamp for an encore, he finds the sheik has pulled a switch, substituting instead an old coffee pot. Egghead gets the trap door – which in this case merely dumps him outside. Through the window, he sees the sheik present the Sultan with jewels and riches from the lamp. Busting in the door, Egghead announces, “Stop! I’ve been swindled!” Here, the writers simply lose their creativity. Egghead merely socks the sheik on the jaw, retrieves the lamp, pulls the Sultan’s daughter outside to the magic carpet, and they fly away safely, with no gag complications. In a somewhat unexplained final shot, Egghead and the Sultan’s daughter now reside in their own palace, but the girl seems to have grown dissatisfied with her suitor, commenting “I’ve been swindled.” She rubs the lamp herself, producing a new genie who I believe is a caricature of Robert Taylor. The two disappear into the lamp together, and when Egghead lifts the lid to peer in, only gets his nose pinched for his troubles.

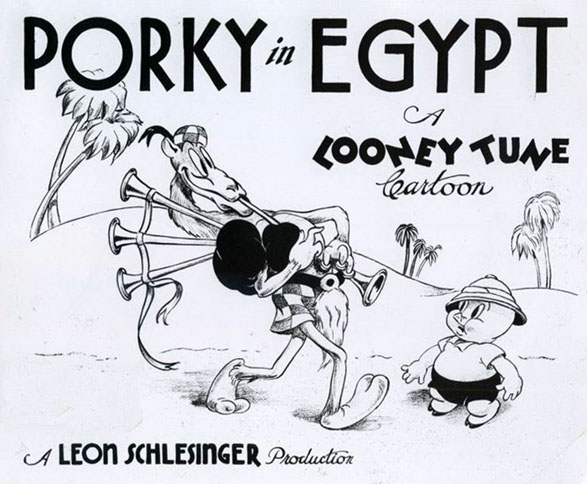

Porky in Egypt (Warner, Looney Tunes (Porky Pig), 11/5/38 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – Amidst the land of the fake fakirs, a tour group sets out on a sightseeing jaunt to the homes of the Mummy Stars, aboard a camel with a seemingly endless line of humps between which to seat passengers, and a trailer in tow for skunks. Porky Pig is a late riser, and misses the tour. Determined to see the sights, he hires a private camel – one Humpty Bumpty. Porky finds his new steed is a bit on the slow side, and urges him on: “C-c-can’t ya go any fa-f-f-fa-f-f- – -SWING IT!” But the desert sun burns without mercy, focusing its beam like a spotlight on Porky, then on the only convenient oasis to burn up irs palm trees like matchsticks and dry up its water hole. Backgrounds start to spiral, as the camel hears his name called by a variety of different voices from nowhere. “The voices…..IT’S THE DESERT MADNESS!!”, the camel shouts. He randomly breaks into lines from “The Charge of the Light Brigade”, then falls at Porky’s feet, declaring them as lost, destined to become “white chalky bones”. Suddenly he envisions an endless caravan on the horizon. “We’re saved! The camels are coming!” He instantly converts this into the Scottish standard, “The Campbells are Coming”, donning a kilt and playing a bagpipe while dancing a highland fling. He disappears over a hill, leaving Porky to think he’s been abandoned – but he finds the camel appearing to bathe in a swimming pool in an oasis marked “Palm Springs”. Of course, when Porky dives in too, he finds them both to be merely submerged in dry sand. The camel breaks into random impressions of Lew Lehr (“Camels is de Kraziest people”) and the Lone Ranger, until he crashes into a tree, knocking himself out of the daze. Temporarily sober, he tells Porky he’s all right now. But then, the voices are distantly heard again. “They’re coming back. Quick, let’s get outta here!” The camel races at top speed through the dunes, eventually winding his way back to the city. He takes Porky inside one of the structures as the voices appear nearly upon him, and locks four doors, shutting the voices out. “Safe at last”, Bumpty declares. “Y-y-yeah, now we’re safe”, Porky answers – then dons a Napoleon hat and breaks into a fit for the iris out.

Here’s the Desert Madness scene:

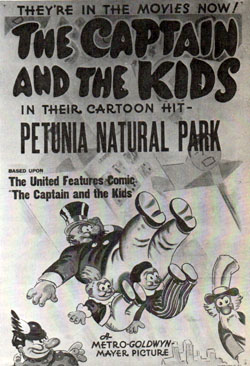

Petunia Natural Park (MGM, The Captain and the Kids, 1/4/39 – Friz Freleng, dir.) – The Captain and the Kids were generally viewed in the industry as a box-office failure, despite the frequent input of Friz Freleng and alleged demographic studies by the studio which advance-guaranteed that the series was destined to be a hit. The series was initially produced in black and white (the first such move by the studio since the Willie Whopper days) to save on the excesses of budget indulged in by Harman and Ising’s late product. But with interest in the series failing, the studio felt desperate measures were in order – and finally consented to invest in Technicolor again. With considerable advance-promotion in the trades, this rather less-than memorable episode was trotted out, as one of only two titles to receive color, before the studio execs abandoned the whole project as a bad job. It also features something unique to MGM cartoons – the only time the standard MGM lion was rotoscoped (sort of) to appear in animated form. (Ub Iwerks had used an animated Leo, but in a humanized version wearing a tuxedo, in Willie Whopper’s “Davy Jones Locker”, and a similar design was used by Lou Bunin for a stop-motion prologue partially excised from the MGM feature “Ziegfield Follies” – such ended the short animation career of the MGM mascot.)

Gag material is rather off-the-wall, and much has very little to do with the personalities of our principal cast. A loudmouth narrator tells of the virgin territory, untouched by human hands – well, almost, as we pass a debris field with a sign stating “No Dumping”. Rare species of wildlife are illustrated by visuals of a standard barnyard cow, sows and chickens. Our heroes finally arrive, illustrative by the common tourist, and are welcomed at the gate by a squad of rangers who block up the Captain’s windshield with warning stickers, including one over the Captain’s eyes reading, “Drive Carefully”. The family drives their car through the trunk tunnel of an old sequoia tree – and come out on an upper limb instead of on the other side. (Did Hanna and Barbera remember this gag for the opening of the Yogi Bear show?) The narrator states, “Let’s take a hop over to the geysers’, and the camera does just that, bouncing the audience to the next scene, while the narrator reacts, “Well, some hop.” Old Dependable fires off right on schedule – for a spit into a spittoon. Mama tries to photograph a bear – but a flock of bears instead take candid shots of her. Some bears are seen shaking nuts from a tree – including the Captain on a limb. After receiving a bite on the shin, the Captain lands in one of the geysers – and is tossed out by the devil. Mama listens to a babbling brook – talking in ladies’ voices with the day’s latest gossip, until one voice says “I think someone’s listening”, and splashes water in Mama’s face. Both Mama and Papa have run-ins with the law – Mama for picking one of the flowers, and Papa for feeding an olive to a bear who turns out to be an Irish cop in disguise. A gag is modified from “Gulliver Mickey” as the curtain of night os pulled over the scene – literally, and the narrator demonstrates how you can hear a pin drop – its fall jarring the whole scenic background as if someone dropped a ten ton weight. A fawn steals down to the water’s edge to get a drink – from a corn liquor jug.

Gag material is rather off-the-wall, and much has very little to do with the personalities of our principal cast. A loudmouth narrator tells of the virgin territory, untouched by human hands – well, almost, as we pass a debris field with a sign stating “No Dumping”. Rare species of wildlife are illustrated by visuals of a standard barnyard cow, sows and chickens. Our heroes finally arrive, illustrative by the common tourist, and are welcomed at the gate by a squad of rangers who block up the Captain’s windshield with warning stickers, including one over the Captain’s eyes reading, “Drive Carefully”. The family drives their car through the trunk tunnel of an old sequoia tree – and come out on an upper limb instead of on the other side. (Did Hanna and Barbera remember this gag for the opening of the Yogi Bear show?) The narrator states, “Let’s take a hop over to the geysers’, and the camera does just that, bouncing the audience to the next scene, while the narrator reacts, “Well, some hop.” Old Dependable fires off right on schedule – for a spit into a spittoon. Mama tries to photograph a bear – but a flock of bears instead take candid shots of her. Some bears are seen shaking nuts from a tree – including the Captain on a limb. After receiving a bite on the shin, the Captain lands in one of the geysers – and is tossed out by the devil. Mama listens to a babbling brook – talking in ladies’ voices with the day’s latest gossip, until one voice says “I think someone’s listening”, and splashes water in Mama’s face. Both Mama and Papa have run-ins with the law – Mama for picking one of the flowers, and Papa for feeding an olive to a bear who turns out to be an Irish cop in disguise. A gag is modified from “Gulliver Mickey” as the curtain of night os pulled over the scene – literally, and the narrator demonstrates how you can hear a pin drop – its fall jarring the whole scenic background as if someone dropped a ten ton weight. A fawn steals down to the water’s edge to get a drink – from a corn liquor jug.

The woodland animals keep the Captain awake with their loud sounds and reflective eyes. The Captain retaliates with gunshots and an attack with a club upon the lone pair of “eyes” left standing – which turns out to be the headlights of the Captain’s car. Only in the last sequence do Hans and Fritz – whom we’d have expected to be center stage with mischief – get to do anything, fetching a pail of water for the car (and the Captain) when the radiator overheats the next morning. They choose to retrieve the water from one of the geysers. Without too much of the unexpected, the car internally “erupts” and zooms off down the road, leaving the Captain, who, having drunk some of the water himself, also experiences tummy trouble as he races after the car. The narrator closes, “So long, Captain. See you next year.” Shaking his fist, the Captain responds, “Not if I see you first!” This is another of those films that plays better on paper than it does on the screen, and despite the participation of Freleng, just feels like it’s trying too hard for a zaniness which at the time the studio was just not accustomed to. It would have been interesting to see Tex Avery in the studio’s later years get hold of the same material and fashion it into a remake. With his adept timing (sorely lacking in the original), one can only wonder how massively the picture would have been improved.

More travelogues, trailers, and returns for some seasoned traveler cartoon stars next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

In terms of sheer imaginative spectacle and brilliant, absurdly elaborate design/animation execution, it’s hard to beat the opening of MICKEY’S TRAILER, in which Mickey pulls that lever and the entire bucolic facade surrounding the trailer folds-up and disappears, to reveal the particularly unappetizing city dump behind. When I saw this in a good 35mm print in the late ’70s, the crowd gasped — and then laughed and cheered. I’ve always assumed that audiences in 1938 must have reacted in much the same way.

“Mickey’s Trailer” certainly is a great cartoon, but what’s interesting is Oliver Wallace’s clever use of “Merrily We Roll Along” as a leitmotif for the trailer rolling along. In fact, the tune is heard at the very end of the cartoon after the iris out — as far as I know, a unique example of this in a non-Warners cartoon.

Fun trivia: The claw machine depicted at the beginning of “A-Lad-In Bagdad” was invented by Max Fleischer’s older brother Charles, according to Richard Fleischer’s book “Out of the Inkwell” (2005).

Speaking of brothers, Jack Shilkret was Nat’s younger brother. They also had an older brother, Lew, a talented pianist who made his living in the insurance business; and the youngest brother, Harry, became a medical doctor but also played trumpet on many of his brothers’ recordings.

I look forward to next week’s outing — when, I have a hunch, we’ll find out how a wabbit can wuin a camping twip! Happy twails!

Actually, the “Merrily We Roll Along” motif used in Mickey’s Trailer doesn’t use the “Merrily” associated with Warners and Eddie Cantor. It’s the last part of the lyric of “Goodnight Ladies”. This earlier “Merrily” appears in the ending of Max Fleischer’s “Finding His Voice” (1929), and the giveaway that this is the version intended is that the Mickey riff includes a paraphrase of the lyric’s last line, “O’er the deep blue sea” during the scene where Mickey is getting water from the waterfall and plucking corn. That portion of the melody was not interpolated into the Cantor version.

By the way – the “wabbit” will show up in two weeks.

Thank you! I’ve seen “Finding His Voice”, but I’d forgotten that “Goodnight Ladies” (with the “Merrily We Roll Along” bridge) was in it.

Two weeks! This vacation is going to be longer than I expected. Guess I’d better stay out of “twouble” until then!

Oh, how I only wish that “REST RESORT” was imbedded in this article. It sure sounded like a funny cartoon from your vivid description, and yes, I’m sorry that the soundtrack to the KRAZY KAT cartoon wasn’t cleaner…and, as always, I have to say that I wish that at least one animated version of the Herriman strip really contained Herriman’s original vision for the characters. I never got to read the original comics panels, but imagine how it could be animated. I’ll also have to look up the set on those Fitzpatrick Traveltalks. I think there were some live action parodies of this kind of live action travelogue, appearing on one of the Thunderbean sets. I look forward to the next installment.

It’s hard to top “Mickey’s Trailer” for a magnificent use of the cartoon medium to make the unbelievable look real. I always thought there was an honorable nod to the architect Buckminster Fuller’s domed-living spaces in the presentation of the trailer and its hidden functionalities.

Mickey’s Trailer is it for me – My favorite Mickey short. Bought the “Mickey Mouse in Living Color” Treasures set at a somewhat inflated price years ago, primarily for that cartoon.

And, speaking of inflated prices, I want to pass along this related bit of news to those interested: While flipping through the current issue of Diamond Previews yesterday, I noticed the publisher, Taschen, is offering not only “Mickey Mouse: The Ultimate History” , but also “Walt Disney Film Archives: The Animated Movies 1921-1968” hardcover books for only $25.00. Now, these volumes measure only 6 x 9, but they’re the same books. I purchased “Golden Age of DC Comics” in the same format last year and was happy with it. Those of you (like me) who balked at paying the exorbitant original cover price for these two tomes might want to take advantage. To quote a classic Eddie Murphy routine: What a bargain! That’s a bargain for me!