For once, a shorter trail this week – and a rare opportunity to see a head-to-head battle of creativity between John Hubley and king of the gags, Tex Avery.

(An aside. Although title for this article was chosen several weeks ago, no one could anticipate the sad recent loss of Doris Day, from whose hit such title quotes. Her animation-related legacy is covered well on Greg Ehrbar’s Spin post of 5/14. We’ll miss you, Doris.)

Animation is a naturally magical art – bringing life forces to still drawings, stop motion, etc. So it’s subject matter would frequently cross over into tricks that would defy the laws of physics, logic, and all sense of reality, creating its own world with its own rules – or lack of them.

Animation is a naturally magical art – bringing life forces to still drawings, stop motion, etc. So it’s subject matter would frequently cross over into tricks that would defy the laws of physics, logic, and all sense of reality, creating its own world with its own rules – or lack of them.

Magic acts were a common item on the bill in the days of vaudeville. The film industry noted from its earliest days that the old notion of “sleight of hand” to make things seem to appear and disappear was particularly adaptable to the medium of the camera. (For a stunning early example of how trick photography and well-timed cutting could accomplish such purpose, see George Melies’ The Magician (1898).) What live-action could do the hard way, animation could make look easy.

The magician as a form of entertainment in the animated cartoon thus saw innumerable uses over the theatrical years: some of the best examples include “Silly Scandals” (Paramount Fleischer, Talkartoon, Betty Boop – 1931), “The Crystal Gazebo” (Columbia/Mintz, Krazy Kat – 1932), “Coo Coo the Magician” (MGM/Ub Iwerks, Flip the Frog – 1933), “Spinning Mice” (RKO/Van Buren, Rainbow Parade – 1935), “The Hyp-Nut-Tist” (Paramount/Fleischer, Popeye – 1935), “House of Magic” (Lantz/Universal, Meany, Miney, and Moe – 1937). “Magician Mickey” (Disney/United Artists, Mickey Mouse, 1937, David Hand, dir,), “Prest-O Change-O” (Warner, Merrie Melodies (with formative Bugs Bunny), 1939 – Charles M.(Chuck) Jones, Dir,), “Stage Fright” (Warner, Merrie Melodies (with a formative Henery Hawk), 1940 – Charles M.(Chuck) Jones, Dir.), “The Henpecked Duck” (Warner, Looney Tunes, Porky and Daffy, 1941 – Robert Clampett, dir. (reviewed in my “Holy Matrimony! And a Stack of Storks, Part 1″ article, this website), “Baggage Buster” (Disney/RKO, Goofy, 1941 – Jack Kinney, dir.)…

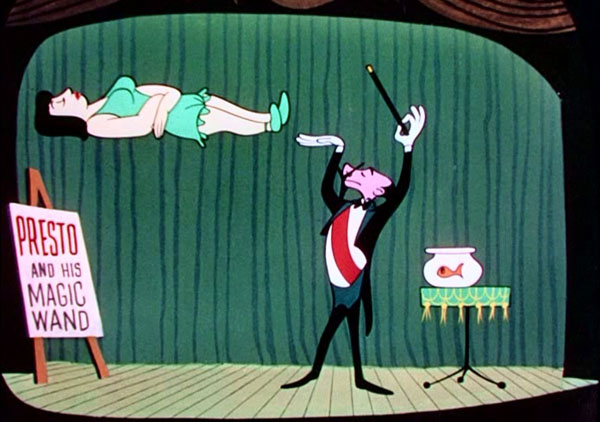

…“The Case of the Missing Hare” (Warner, Bugs Bunny Merrie Melodies, 1942 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, Dir.), “The Bird Came C.O.D.” (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 1942 – Chuck Jones, dir.), “Magicalulu” (Paramount/Famous, Little Lulu, 1945 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.), “The Fistic Mystic” (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 1946 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.), “Mysto-Fox” (Columbia/Screen Gems, Fox and Crow, 1946 – Bob Wickersham, dir.), “Mighty Mouse and the Magician” (Fox/Terrytoons, 1948, Eddie Donnelly, dir.), “A Balmy Swami (Paramount,/Famous, Popeye, 1949 – I. Sparber, dir.) “Of Mice and Magic” (Paramount/Famous, Herman and Katnip, 1953, I. Sparber, dir.). “The Great Who-Dood-It” (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 1952, Don Patterson, dir.), “Voo Doo Boo Boo” (Universal/Lantz, Woody Woodpecker/Gabby Gator, 1961 – Jack Hannah, dir.), “Tragic Magic” (Universal/Lantz, Woody Woodpecker, 1962 – Paul J. Smith, Dir.), “Haunted Mouse” (MGM/Chuck Jones, Tom and Jerry, 1965), “The Hand Is Pinker Than the Eye” (Depatie-Freleng,/UA, Pink Panther, 1967), “Mystic Pink” (Depatie-Freleng,/UA, Pink Panther, 1976) and brief magician sequences in “Hamateur Night” (Warner.Merrie Melodies, Egghead , 1939 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.), “Believe It Or Else” (Warner/Merrie Melodies, Egghead, 1939 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir,), and “Show Biz Bugs” (Warner, Bugs Bunny/Daffy Duck, 1957 – Friz Freling, dir.), plus an entire series at Warner starring Merlin the Magic Mouse. Most recently, Pixar provided us with the delightful Presto (2008) – a near-homage in CGI to Bugs Bunny’s Case of the Missing Hare with some new surprise twists.

…“The Case of the Missing Hare” (Warner, Bugs Bunny Merrie Melodies, 1942 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, Dir.), “The Bird Came C.O.D.” (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 1942 – Chuck Jones, dir.), “Magicalulu” (Paramount/Famous, Little Lulu, 1945 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.), “The Fistic Mystic” (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 1946 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.), “Mysto-Fox” (Columbia/Screen Gems, Fox and Crow, 1946 – Bob Wickersham, dir.), “Mighty Mouse and the Magician” (Fox/Terrytoons, 1948, Eddie Donnelly, dir.), “A Balmy Swami (Paramount,/Famous, Popeye, 1949 – I. Sparber, dir.) “Of Mice and Magic” (Paramount/Famous, Herman and Katnip, 1953, I. Sparber, dir.). “The Great Who-Dood-It” (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 1952, Don Patterson, dir.), “Voo Doo Boo Boo” (Universal/Lantz, Woody Woodpecker/Gabby Gator, 1961 – Jack Hannah, dir.), “Tragic Magic” (Universal/Lantz, Woody Woodpecker, 1962 – Paul J. Smith, Dir.), “Haunted Mouse” (MGM/Chuck Jones, Tom and Jerry, 1965), “The Hand Is Pinker Than the Eye” (Depatie-Freleng,/UA, Pink Panther, 1967), “Mystic Pink” (Depatie-Freleng,/UA, Pink Panther, 1976) and brief magician sequences in “Hamateur Night” (Warner.Merrie Melodies, Egghead , 1939 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.), “Believe It Or Else” (Warner/Merrie Melodies, Egghead, 1939 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir,), and “Show Biz Bugs” (Warner, Bugs Bunny/Daffy Duck, 1957 – Friz Freling, dir.), plus an entire series at Warner starring Merlin the Magic Mouse. Most recently, Pixar provided us with the delightful Presto (2008) – a near-homage in CGI to Bugs Bunny’s Case of the Missing Hare with some new surprise twists.

Our trail, though, focuses on a specialized breed of film, presenting a setting almost unique to the cartoon medium – the pairing of a magician’s tricks with animation’s traditional love for music. Magic acts presented in a musical setting – or doing their best to destroy a musical performance.

Only one live-action short is currently known to this author to have combined the mediums of magic and music – Warner/Vitaphone’s Postal Union (1937), starring Georgie Price, who engages in a singing magic act of camera-trick disappearances for a tuneful finale.

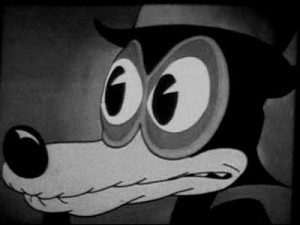

Though not truly in the context of a magic act, one of the earliest precursors of musical magic may have to be Svengarlic (Columbia, Charles Mintz, Krazy Kat – 1931 – Ben Harrison/Manny Gould). Reprising in animated form the legendary story of Svengali and his magical influence in bewitching his protégé “Trilby” into a coloratura singing career, wolf Svengarlic uses magnetizing finger waves and wild-eyed hypnotic glances to place Krazy’s girlfriend (renamed “Trilby” for this cartoon) into a trance, to follow him to the theater stage. (Footnote: I must have blinked when I first saw this cartoon – I missed a momentary morph during Svengarlic’s hypnotic stare, that transforms his eyeballs for about two seconds into miniature magnets – thus, cross-reference this title into my previous article, “Magnetic Personalities”.) Thinking he has locked Krazy out, Svengarlic proceeds to the maestro’s podium in the orchestra pit as the curtain rises. Trilby’s performance under his baton begins – but is interrupted by a “raspberry” from the balcony, as Krazy appears.

Though not truly in the context of a magic act, one of the earliest precursors of musical magic may have to be Svengarlic (Columbia, Charles Mintz, Krazy Kat – 1931 – Ben Harrison/Manny Gould). Reprising in animated form the legendary story of Svengali and his magical influence in bewitching his protégé “Trilby” into a coloratura singing career, wolf Svengarlic uses magnetizing finger waves and wild-eyed hypnotic glances to place Krazy’s girlfriend (renamed “Trilby” for this cartoon) into a trance, to follow him to the theater stage. (Footnote: I must have blinked when I first saw this cartoon – I missed a momentary morph during Svengarlic’s hypnotic stare, that transforms his eyeballs for about two seconds into miniature magnets – thus, cross-reference this title into my previous article, “Magnetic Personalities”.) Thinking he has locked Krazy out, Svengarlic proceeds to the maestro’s podium in the orchestra pit as the curtain rises. Trilby’s performance under his baton begins – but is interrupted by a “raspberry” from the balcony, as Krazy appears.

Svengarlic casts his magical finger waves at Krazy, causing Krazy’s eyes to rotate wildly in their sockets, then his head to disappear into his body below the collar line. Krazy briefly collapses below the level of the balcony railing, and the singing performance continues – but Krazy reappears (his head now restored), and peppers the maestro with peas from a peashooter. The maestro warms up his fingers for another dose of magic – but Krazy wards off the spell by donning a pair of dark sunglasses. Trilby attempts to hit a high note, but her voice cracks terribly. Svengarlic lives up to his name by chewing a strong piece of garlic, then blowing the aromas in Trilby’s face, causing her to reach the high note that was eluding her. Krazy ducks into the engravings on the outer wall of the balcony, shaped like a theater mask, sticking his peashooter out of the mouth of the face to play the stick like a flute. His flute obbligatos are matched by Trilby, who reaches for higher and higher notes – but again gets stuck for a top one. Svengarlic reaches for another piece of garlic to chew – but Krazy douses him from the balcony with even stronger concentrated fumes out of an insect spray gun, causing Svengarlic to collapse. Trilby is now seen in point of view from the wings, with portions of the backstage visible in the rear of the curtain behind her. As she makes one last desperate try to ascend the scale to reach her high note, Krazy appears behind her backstage, and at the crucial moment slaps Trilby on the butt through the curtain. Trilby screams – precisely on key – and the concert is saved, as Krazy comes out on stage to give her a “Mickey Mouse” style kiss as the scene irises out to the applause of her public.

The Wizard of Oz (Ted Eshbaugh/J.R. Booth, prod. , Eshbaugh, dir. – 1933) – This breakthrough independent film, recently restored in glorious three-strip Technicolor (and apparently produced without theatrical release as a demonstration film for the Technicolor company according to recent sources), practically blows the color palette of Disney’s Oscar-winning “Flowers and Trees” out of the water. We can only wonder what would have happened if the Eshbaugh film had been made available for Oscar consideration. Loosely based on the book and stage versions of the story (and without a cowardly lion), this film presents the Wizard in an entirely different light than other versions. No humbug from Kansas, he is an old white-bearded fellow in traditional pointed hat and robe, whose only aim in life seems to be to provide magical entertainment for his guests. As he produces four different-style chairs for Dorothy, Toto, the Scarecrow and Tin Woodsman, he engages in musically-timed acts of legerdemain, including producing eight magic hats, out of which seem to pop the heads of rabbits – but which turn out to be the legs and panties of eight dancing dolls, who perform a choreographed precision dance while the background is completely blacked out to emphasize their changing colors and movement.

The Wizard’s next trick (not quite as musically timed) has him producing a hen, and pouring a magic potion into her mouth. She lays a series of eggs, and the Wizard taps each with his wand, hatching weird animals that seem to be half bird, half something-else (including parts of elephants, giraffes, monkeys, and even a dragon). The last egg is a pipsqueak and the mother hen cries to let it out. As she listens for activity inside the shell, the egg suddenly doubles in size – then again – and again. It develops humongous, room filling proportions, and Toto picks this inopportune time to steal the magic wand like he was fetching a stick. Some chaos ensues as the Wizard gives chase, the Scarecrow and Tin Man helplessly attack the egg with a series of axes that each break, and the egg’s growth threatens the structural foundation of the emerald palace. Fortunately, as the Woodsman reaches back for the last axe on the wall, Toto shows up, and he grabs the magic wand instead. The shell is finally broken in an explosion. To everyone’s surprise, all that was inside the giant egg was a normal baby chick, to the mother hen’s delight.

Mickey Mouse provides what amounts to the crystalizing root for the genre of this article in Mickey’s Grand Opera (Disney/United Artists , 3/7/36 – Wilfred Jackson). Recently mentioned in Devon Baxter’s post on Magician Mickey, this website, both this film and Magician Mickey share a common origin – an early draft story entitled “Mickey’s Vaudeville Show”, in which the magic act was to form part one of the story, and the opera the finale. As it was, when the script was split in two, the opera was produced a year ahead of the magic act. But the act, though not seen in this cartoon, nevertheless plays a central role in disrupting the musical performance.

Mickey Mouse provides what amounts to the crystalizing root for the genre of this article in Mickey’s Grand Opera (Disney/United Artists , 3/7/36 – Wilfred Jackson). Recently mentioned in Devon Baxter’s post on Magician Mickey, this website, both this film and Magician Mickey share a common origin – an early draft story entitled “Mickey’s Vaudeville Show”, in which the magic act was to form part one of the story, and the opera the finale. As it was, when the script was split in two, the opera was produced a year ahead of the magic act. But the act, though not seen in this cartoon, nevertheless plays a central role in disrupting the musical performance.

Mickey plays only a minor role in this title as conductor. The lion’s share of footage goes to new star Donald Duck, and his returning co-star, direct from her former stage triumph in Orphans’ Benefit (1934), operatic poultry Clara Cluck. (“Cluck” (voiced by Florence Gill) actually had her origins closely associated with those of Donald – first appearing in slightly different form as “The Wise Little Hen” (Silly Symphony, 1934), the same film in which Donald debuted, and then recast in full operatic form for Donald’s second appearance in Orphans’ Benefit.) While Donald and Clara had been rather at loggerheads or in competition with each other in the previous episodes, this time they’re cast as something of an item – starring as Romeo and Juliet in a musical version of the balcony scene, oddly converting for score the “Rigoletto” quartet into a duo. Such duet singing would later become something of a regular feature on Mickey Mouse radio shows of the 1930’s. For a chance to see Gill in clucking action around this time, check out the Paramount feature, “Every Night at Eight” (1935), on ok.ru website.

However, bringing up the rear (in this case, the backstage) is Pluto, who’s not supposed to be there in the first place, as Mickey ordered him home. While Pluto attempts to rest in the prop room (filled with trunks and posters announcing the upcoming performance of “the Famous Magic Hat”), one rabbit, then two, engage in a game of peek-a-boo out of said hat, then deliver the hound a sock on the nose. Pluto shakes the hat by the brim, only to have a flock of doves appear and swoop down on him. Crushing the hat fails, as it pops back to normal shape. The hat now begins to creep along the floor under its own power, and Pluto chases it round and round a crate. The performance has meanwhile begun, going smoothly except for Donald almost bursting into a temper tantrum when a sword he is carrying gets wedged into a prop tree. The hat creeps its way onto stage, Pluto cautiously following. Mickey, at the conductor’s podium, spots Pluto when he reaches center stage, and whispers to him to “Go home.” Pluto starts to, but has second thoughts and continues to follow the hat. Another “go home” gets the same lack of results. Finally, the whole orchestra yells in unison, “GO HOME!” for a surprise to both us and Pluto. But the hat skitters under his legs and the chase persists. The hat climbs onto the mouth of the tuba, and inside. Suddenly, with every tuba note, an eruption of doves and rabbits emerges from within.

However, bringing up the rear (in this case, the backstage) is Pluto, who’s not supposed to be there in the first place, as Mickey ordered him home. While Pluto attempts to rest in the prop room (filled with trunks and posters announcing the upcoming performance of “the Famous Magic Hat”), one rabbit, then two, engage in a game of peek-a-boo out of said hat, then deliver the hound a sock on the nose. Pluto shakes the hat by the brim, only to have a flock of doves appear and swoop down on him. Crushing the hat fails, as it pops back to normal shape. The hat now begins to creep along the floor under its own power, and Pluto chases it round and round a crate. The performance has meanwhile begun, going smoothly except for Donald almost bursting into a temper tantrum when a sword he is carrying gets wedged into a prop tree. The hat creeps its way onto stage, Pluto cautiously following. Mickey, at the conductor’s podium, spots Pluto when he reaches center stage, and whispers to him to “Go home.” Pluto starts to, but has second thoughts and continues to follow the hat. Another “go home” gets the same lack of results. Finally, the whole orchestra yells in unison, “GO HOME!” for a surprise to both us and Pluto. But the hat skitters under his legs and the chase persists. The hat climbs onto the mouth of the tuba, and inside. Suddenly, with every tuba note, an eruption of doves and rabbits emerges from within.

They disrupt Donald’s singing by yanking and tearing his cape, and Clara almost has her tongue swallowed by two doves staring inside her widely-singing bill. Meanwhile, a new trick hatches from the tuba – a growing plant, with five different blooms, the largest one being a sunflower with a live frog on top. The frog leaps onto the stage, and is hopped after by Pluto. Donald continues to sing, and while his mouth spreads wide for a long note, the frog leaps inside. Donald is now at the mercy of the frog, who bounces him everywhere as he leaps inside Donald’s rear end. Donald, still holding onto his sword, is bounced directly under Clara’s balcony. A high leap from the frog shoots Donald upwards, his sword penetrating the balcony floor under Clara, who lets fly with the highest screeching “cluck” of her career. She shoots high into the air, then falls hard back onto the balcony. Her weight topples the scenery, crashing cast, balcony and backdrop to the stage below. Out through the fallen backdrop canvas pop the heads of Donald, Clara, Pluto, and the frog, each howling a long note in four-part harmony, as the camera slowly irises out on this grand finale.

They disrupt Donald’s singing by yanking and tearing his cape, and Clara almost has her tongue swallowed by two doves staring inside her widely-singing bill. Meanwhile, a new trick hatches from the tuba – a growing plant, with five different blooms, the largest one being a sunflower with a live frog on top. The frog leaps onto the stage, and is hopped after by Pluto. Donald continues to sing, and while his mouth spreads wide for a long note, the frog leaps inside. Donald is now at the mercy of the frog, who bounces him everywhere as he leaps inside Donald’s rear end. Donald, still holding onto his sword, is bounced directly under Clara’s balcony. A high leap from the frog shoots Donald upwards, his sword penetrating the balcony floor under Clara, who lets fly with the highest screeching “cluck” of her career. She shoots high into the air, then falls hard back onto the balcony. Her weight topples the scenery, crashing cast, balcony and backdrop to the stage below. Out through the fallen backdrop canvas pop the heads of Donald, Clara, Pluto, and the frog, each howling a long note in four-part harmony, as the camera slowly irises out on this grand finale.

Clara returned to the small screen for a cameo in Disney’s TV Mickey Mouse short, “Bad Ear Day” (2013), amazing her audience with her versatility in clucking the “Figaro” aria from “Barber of Seville” while playing Brunhilde from Wagner’s “Die Walküre”!

“The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” sequence from Disney’s famous symphonic tour-de-force Fantasia (1940), presenting Mickey Mouse in his first feature role, is of course well-known, with Mickey’s wizard outfit becoming a veritable corporate symbol. Rooting from the equally famous symphonic treatment by Paul Dukas of an early poem by Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe from 1797, this tale of miscast spells and enchanted water-carrying broomsticks presents one of the world’s most tuneful treatments of magical feats, and has delighted audiences for decades, generally regarded as one of Disney’s crowning classics. But does he really deserve all of its credit? You be the judge. Take a look at the virtually unknown and forgotten early talkie short, The Wizard’s Apprentice (1930), a combination of live action with puppet and stop-motion animation. This curious yet enchanting short follows the same musical pattern and arrangement as its 1940 successor, and presents in dramatically-edited and well-timed form nearly the same storyboard as the Disney version – brooms, water, multiplying, and all. The 1930 version embellishes in a few directions Disney didn’t, including a female magically conjured who becomes sort of a girlfriend for the apprentice – but the basic spirit and timing remain intact. The broom animation is primitive – yet reasonably effective. Distribution of the 1930 short remains a mystery – Joseph M. Schenck (you’ve seen his name on every surviving United Artists Mickey Mouse black and white episode as the resident mogul for that studio, taking name credit above Disney’s) had a hand in its production, again taking credit above the film title – but there’s no reference on surviving prints to United Artists. Perhaps this was before Schenck’s association with that studio – or the titles of the current prints may have been altered. However, and especially given Disney’s long association with Schenck, it would be amazingly unlikely that Disney didn’t know of this film long before producing his own. Presenting so many obvious suggestions for layout and cinematography, it’s my feeling that the early film deserves substantial credit for both originality and influence upon the final Technicolor Disney product we’ve all grown to know and love. Fantasia, which originally had no credits onscreen, should probably have justly included a credit to “Suggested by a screenplay by…” or something to that effect. (The 1930 film has been in recent years made commercially available through Thunderbean, in its former DVD set Grotesqueries – soon to be reissued in blu-ray.)

“The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” sequence from Disney’s famous symphonic tour-de-force Fantasia (1940), presenting Mickey Mouse in his first feature role, is of course well-known, with Mickey’s wizard outfit becoming a veritable corporate symbol. Rooting from the equally famous symphonic treatment by Paul Dukas of an early poem by Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe from 1797, this tale of miscast spells and enchanted water-carrying broomsticks presents one of the world’s most tuneful treatments of magical feats, and has delighted audiences for decades, generally regarded as one of Disney’s crowning classics. But does he really deserve all of its credit? You be the judge. Take a look at the virtually unknown and forgotten early talkie short, The Wizard’s Apprentice (1930), a combination of live action with puppet and stop-motion animation. This curious yet enchanting short follows the same musical pattern and arrangement as its 1940 successor, and presents in dramatically-edited and well-timed form nearly the same storyboard as the Disney version – brooms, water, multiplying, and all. The 1930 version embellishes in a few directions Disney didn’t, including a female magically conjured who becomes sort of a girlfriend for the apprentice – but the basic spirit and timing remain intact. The broom animation is primitive – yet reasonably effective. Distribution of the 1930 short remains a mystery – Joseph M. Schenck (you’ve seen his name on every surviving United Artists Mickey Mouse black and white episode as the resident mogul for that studio, taking name credit above Disney’s) had a hand in its production, again taking credit above the film title – but there’s no reference on surviving prints to United Artists. Perhaps this was before Schenck’s association with that studio – or the titles of the current prints may have been altered. However, and especially given Disney’s long association with Schenck, it would be amazingly unlikely that Disney didn’t know of this film long before producing his own. Presenting so many obvious suggestions for layout and cinematography, it’s my feeling that the early film deserves substantial credit for both originality and influence upon the final Technicolor Disney product we’ve all grown to know and love. Fantasia, which originally had no credits onscreen, should probably have justly included a credit to “Suggested by a screenplay by…” or something to that effect. (The 1930 film has been in recent years made commercially available through Thunderbean, in its former DVD set Grotesqueries – soon to be reissued in blu-ray.)

The Magic Fluke (Columbia/UPA, Fox and Crow, 3/24/49 – John Hubley). Columbia, in a period of ever tightening budgets affecting numerous aspects of production (leading, for example, to massive reuses of stock footage and episodes ranging from partial remakes to virtual disguised reissues in its live action shorts (Three Stooges, Andy Clyde and serials, and to numerous short features made on-the-cheap by producer Sam Katzman), and after numerous changes of leadership and managerial upheaval among its animation staff, had closed down its own in-house animation studio (Screen Gems) permanently. Attempting to survive (as did MGM for a time in the late ‘50’s) on doling out on a gradual basis a backstock of already completed titles between reissues of its vintage cartoons (several dating back to the 1930’s, which must have looked pretty passe to 1950’s audiences), bookings and revenues must have been going increasingly downhill. Someone (as later happened with MGM) must have realized that an affordable alternative source for new product had to be found, or the animation release schedule would have to be abandoned altogether.

The Magic Fluke (Columbia/UPA, Fox and Crow, 3/24/49 – John Hubley). Columbia, in a period of ever tightening budgets affecting numerous aspects of production (leading, for example, to massive reuses of stock footage and episodes ranging from partial remakes to virtual disguised reissues in its live action shorts (Three Stooges, Andy Clyde and serials, and to numerous short features made on-the-cheap by producer Sam Katzman), and after numerous changes of leadership and managerial upheaval among its animation staff, had closed down its own in-house animation studio (Screen Gems) permanently. Attempting to survive (as did MGM for a time in the late ‘50’s) on doling out on a gradual basis a backstock of already completed titles between reissues of its vintage cartoons (several dating back to the 1930’s, which must have looked pretty passe to 1950’s audiences), bookings and revenues must have been going increasingly downhill. Someone (as later happened with MGM) must have realized that an affordable alternative source for new product had to be found, or the animation release schedule would have to be abandoned altogether.

Based on its last in-house output, Columbia didn’t have many properties it could call marketable “stars”. Licensing of “L’il Abner” had failed to click both with the public and with Al Capp himself. The good-neighbor policy inspired “Tito and his Burrito” now seemed mild and outdated, and only enjoyed continued life in comic books. “Flippy”, a cat and canary series, had been in a position to potentially take the world by storm, but never quite succeeded in developing on-screen personality for the characters, especially in the case of Flippy himself, who could only tweet. Friz Freleng at Warners would usurp Flippy’s throne, despite Columbia’s precedence in time in use of a cat/bird duo, by the ingenious idea of pairing Bob Clampett’s independently-working Tweetie Pie and Sylvester the Cat into a partnership that would last the years, while Flippy (renamed “Flippity” and the cat “Flop”) would find himself also relegated to comics.

The only viable alternative left for Columbia was “Fox and Crow”, its most successful series from the 1940’s, inaugurated by Frank Tashlin and maintained for years in highly entertaining form by Fleischer veteran Bob Wickersham. However, some of the steam had gone out of the product in recent years past, as Wickersham had left, and the characters’ mutual voice (Frank Graham) had also departed. Producers Raymond Katz and Henry Binder did a downright rotten job of voice recasting, changing Fox’s personality from high pitched gullible-but- reasonably-intelligent Milquetoast to a deeper voiced basic “dum dum” type, and raising the pitch of Crow’s gravelly voice to a level that came off irritating. And Alex Lovy, in what amounted to one of his rare directorial failures, couldn’t seem to maintain the pacing and energy of the characters that had been their previous lifeblood. The last couple of installments from Katz-Binder thus suffer accordingly.

The only viable alternative left for Columbia was “Fox and Crow”, its most successful series from the 1940’s, inaugurated by Frank Tashlin and maintained for years in highly entertaining form by Fleischer veteran Bob Wickersham. However, some of the steam had gone out of the product in recent years past, as Wickersham had left, and the characters’ mutual voice (Frank Graham) had also departed. Producers Raymond Katz and Henry Binder did a downright rotten job of voice recasting, changing Fox’s personality from high pitched gullible-but- reasonably-intelligent Milquetoast to a deeper voiced basic “dum dum” type, and raising the pitch of Crow’s gravelly voice to a level that came off irritating. And Alex Lovy, in what amounted to one of his rare directorial failures, couldn’t seem to maintain the pacing and energy of the characters that had been their previous lifeblood. The last couple of installments from Katz-Binder thus suffer accordingly.

Enter a bid from a total newcomer to the entertainment field – United Productions of America (UPA), whose stock in trade for several years of development had been strictly commercial and educational films. Could these renegades, stressing and specializing in improvisational artistic freedom and moderne design in substitution for traditional fluid movement, save a floundering animation division where so many others had failed, and compete with the big boys like MGM and Warners? The answer is a well-documented part of animation history, which would lead Columbia to numerous nominations and academy awards (including the sweeping of the entire list of nominees for the Oscar in 1957).

UPA’s most celebrated director, John Hubley, manned the helm for the studio’s first four entries. Columbia (sticking with its only characters with a track record), commissioned Hubley to direct a new Fox and Crow. Robin Hoodlum would for the first time place the characters into the new setting of a costumed medieval adventure. Although Fox’s new voice would vary to fit the need in each of Hubley’s episodes (British-accented in “Hoodlum”, Mediterranean-accented in the later costume epic, Punchy De Leon, and straight in Magic Fluke), Crow’s new voice (John T, Smith, best remembered for his catch line “What! No gravy??” in Warner’s Chow Hound (1951)) was basically dead-on, and closely resembled Graham’s previous work. Most of all, the duo seemed to recover its previous zing. “Hoodlum” would receive an Oscar nomination – not bad for the studio’s first try.

UPA’s most celebrated director, John Hubley, manned the helm for the studio’s first four entries. Columbia (sticking with its only characters with a track record), commissioned Hubley to direct a new Fox and Crow. Robin Hoodlum would for the first time place the characters into the new setting of a costumed medieval adventure. Although Fox’s new voice would vary to fit the need in each of Hubley’s episodes (British-accented in “Hoodlum”, Mediterranean-accented in the later costume epic, Punchy De Leon, and straight in Magic Fluke), Crow’s new voice (John T, Smith, best remembered for his catch line “What! No gravy??” in Warner’s Chow Hound (1951)) was basically dead-on, and closely resembled Graham’s previous work. Most of all, the duo seemed to recover its previous zing. “Hoodlum” would receive an Oscar nomination – not bad for the studio’s first try.

On the strength of this triumph, the orders continued for more episodes. Hubley agreed to produce two more as mentioned above, but requested permission to try something new for a fourth cartoon – a little curmudgeon of a man with an advanced case of severe myopia – birth of the immortal Mister Magoo. The studio would never look back to Columbia’s old character roster again.

With this background, we now focus on Hubley’s second epic, Magic Fluke. Having no known counterpart in previous cartoon productions save the minimal inspirations of the cartoons reviewed above, UPA and Hubley come up with an entirely original premise. Suppose a magic wand got mistaken for a conductor’s baton? After all, they look almost alike. A forgivable mistake – until the sparks start to fly.

With this background, we now focus on Hubley’s second epic, Magic Fluke. Having no known counterpart in previous cartoon productions save the minimal inspirations of the cartoons reviewed above, UPA and Hubley come up with an entirely original premise. Suppose a magic wand got mistaken for a conductor’s baton? After all, they look almost alike. A forgivable mistake – until the sparks start to fly.

Fox and Crow enter this odd situation through a series of unfortunate happenstances. This time, instead of being immediately at each other’s throats as they were in many a cartoon, they are cast as musician buddies, performing in a local “Eat at Joe’s” diner for dancing. Well, they’re not really both performing. “Lips” Fox (though he never blows a trumpet) is strictly a baton waver, fronting an “orchestra” consisting entirely of Crow (his “Hot One”) as an overworked but eager one man band. They co-exist happily until a telegram arrives. Fox (apparently a status seeker), has other irons in the fire, and receives word in the message that he has been accepted for the post of symphony conductor. Giving no thought to his erstwhile pal, Fox abruptly dissolves the partnership, leaving in a taxi for the bright lights. Crow is left on the street, bemoaning the loss of his pal.

Time passes. Crow (providing voice over narration), indicates he seriously considered quitting show business, and is seen wandering the streets in shabby clothing, and (much in the same manner as Donald Duck in the Disney short No Sail (1945)) with unshaven stubble grown out of his bill. He suddenly brightens at discovering a theater marquee annumncing Fox’s conducting debut, as the great “Foxini”. He joins the gathering crowd as Fox arrives in a limousine. Crow attempts to congratulate and reestablish contact with Fox, but Fox refuses to lower himself to recognize him (or perhaps really has forgotten about him altogether), and merely autographs Crow’s gloved hand. Crow, only mildly discouraged, attributes Fox’s attitude to “anything for a laugh.”

Time passes. Crow (providing voice over narration), indicates he seriously considered quitting show business, and is seen wandering the streets in shabby clothing, and (much in the same manner as Donald Duck in the Disney short No Sail (1945)) with unshaven stubble grown out of his bill. He suddenly brightens at discovering a theater marquee annumncing Fox’s conducting debut, as the great “Foxini”. He joins the gathering crowd as Fox arrives in a limousine. Crow attempts to congratulate and reestablish contact with Fox, but Fox refuses to lower himself to recognize him (or perhaps really has forgotten about him altogether), and merely autographs Crow’s gloved hand. Crow, only mildly discouraged, attributes Fox’s attitude to “anything for a laugh.”

The time for the performance draws near. Crow peers into the theater wings from a small rear window. A trio of flunkies inside commit a fatal oversight – they have forgotten to procure the Maestro a baton. Crow, outraged at their ineptness, decides to intervene. Spotting through the stage door of an adjoining theater a magic act in progress, Crow sneaks in and makes off with the magician’s wand in mid-performance. Running back to the concert hall, he presents the wand to Fox. Without a word, Fox examines the wand, gives a cold nod of approval, and pockets it to make his entrance onto the stage (stepping on Crow in the process). Crow manages to procure a discount seat somewhere in the 40th balcony, and the concert commences. Set (for the umpteenth time in cartoon history) to the tune of Lizst’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, Fox’s performance is punctuated (and devastated) by a series of accidental triggerings of magic tricks with each wave of the wand, including appearing and disappearing football pennants, umbrellas, and balloons, levitation tricks, sawing a woman in half (by conversion of the orchestra’s bass fiddle and bow), and appearances of doves and rabbits from nowhere. Finally, with two sweeping moves, Fox causes his whole orchestra to disappear, just as the wand poops out of powers and shrivels in his hand. Can Crow save the situation? Well, watch this little gem and see for yourself.

“Fluke” was anything but what its title suggests, Like its predecessor, the film would draw in another Academy nomination certificate for Columbia. At this point Hubley and studio producer Steve Bosustow could pretty much do no wrong in the eyes of the Columbia executives – as long as they stayed within budget.

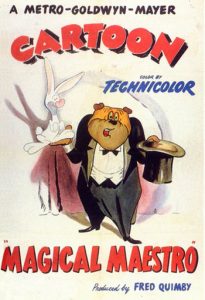

Magical Maestro (MGM, 2/9/52 – Tex Avery) – Although Columbia was “on the rebound” when Magic Fluke was produced above, and no doubt was not in a position to achieve theatrical bookings parallel to the more major studios (especially considering that Columbia, unlike Warners and MGM (through Loew’s International), did not control its own chain of theaters to provide a guaranteed avenue for screening dates), the attention of an Oscar nomination for “Fluke” must have meant that at least those in the industry would have been well aware of its presence and content. While Terrytoons’ reputation would have normally pegged them as the most likely suspects to dare think of plagiarizing an award contender within only three years of its release, major player MGM’s exclusive source of one-shot non-series cartoons, Tex Avery, unexpectedly leaps into the fray.

Magical Maestro (MGM, 2/9/52 – Tex Avery) – Although Columbia was “on the rebound” when Magic Fluke was produced above, and no doubt was not in a position to achieve theatrical bookings parallel to the more major studios (especially considering that Columbia, unlike Warners and MGM (through Loew’s International), did not control its own chain of theaters to provide a guaranteed avenue for screening dates), the attention of an Oscar nomination for “Fluke” must have meant that at least those in the industry would have been well aware of its presence and content. While Terrytoons’ reputation would have normally pegged them as the most likely suspects to dare think of plagiarizing an award contender within only three years of its release, major player MGM’s exclusive source of one-shot non-series cartoons, Tex Avery, unexpectedly leaps into the fray.

How did this occur? Most likely not from any involvement or input of the studio’s producer, Fred Quimby, who had a reputation for having no sense of humor, and seemed to care less what was produced so long as it got the bookings. As there further seems to be no commonality of writer or animator credits between Fluke and Maestro, Avery himself would seem to be the culprit. Although Avery was not generally prone to story “borrows” from others, one further instance would occur shortly after this production – 1952’s One Cab’s Family (to be discussed and analyzed in a future article). With Avery’s long track record of originality, one can hardly attribute these two strange instances to running out of material or writer’s block. More likely, this was another circumstance similar to Avery’s creation of What’s Buzzin’, Buzzard? in apparent reaction to Woody Woodpecker’s Pantry Panic (both discussed in my previous article, “Unhealthy Appetites”, this website) – something must have stuck in his craw about the rival cartoon, leading him to believe that he could go it one better. Let’s just say, Tex does his darndest to live up to such challenge in this one.

The main plotline distinctions between Maestro and Fluke are that (1) Avery chooses instead of the symphony to have the magic invade an operatic recital (incorporating an element of Mickey’s Grand Opera), and (2) rather than happenstance, Avery decides things can be funnier if the interference with the act is intentional, instigated by another for the purpose of humiliation and revenge.

The main plotline distinctions between Maestro and Fluke are that (1) Avery chooses instead of the symphony to have the magic invade an operatic recital (incorporating an element of Mickey’s Grand Opera), and (2) rather than happenstance, Avery decides things can be funnier if the interference with the act is intentional, instigated by another for the purpose of humiliation and revenge.

The film, starring Avery’s regular bulldog foil for Droopy, Spike, opens on a theater marquee, announcing in neon lights performance of Spike under the stage name of the great “Poochini” (a direct parallel to Fox’s assumption of the name “Foxini” in Fluke). To the stage door and backstage enters a top-hatted performer with a small traveling suitcase. He knocks on the door of Poochini’s dressing room, introduces himself as “Mysto the Magician”, and states that what Poochini’s show needs is a “sure-fire magic act.” He pulls two rabbits (male and female, differentiated by length of eyelashes) out of his hat, and makes flowers appear. “Now, do I get the job?”, he asks. We abruptly cut to exterior outside the stage door, where we hear from inside the distant but booming answer of Poochini – “NOOOOOOOOOOO!!!!” Mysto is kicked out the door and onto his proverbial ear, with a large footprint embedded in the seat of his pants. Discouraged, Mysto’s gaze falls on his wand, and he toys with repeated appearances of the rabbits and flower – then brightens as an idea for revenge hatches. He walks over to a promotional poster on the theater wall of Poochini and his conductor. In his mind’s eye, the poster image is transformed, replacing himself in place of the conductor, holding his magic wand instead of the conductor’s baton. The scene fades out.

It is now performance time, with the orchestra tuning up. Poochini makes his entrance, and the orchestra begins the introductory bars of the “Largo al Factotum” aria from “The Barber of Seville”. But before the introduction is completed, there is a brief pause. The conductor is paralyzed by a zap from Mysto’s magic wand, and drawn into a prompter’s box below the stage where Mysto is waiting. More zaps, and Mysto magically transfers to himself the conductor’s tuxedo, hairdo (is it a wig or does he get scalped?), and even the conductor’s nose!. Leaving the conductor motionless in his flannel underwear, Mysto takes his place on the podium, and the musicians complete playing the introduction. Now for Poochini. As he sings, a flower pot appears from nowhere in one hand. Surpried, he ducks it out of sight behind him. But when he next raises his hands, the rabbits appear in his right and left palms. He attempts to duck them also behind his back, but when his arms come out again, both rabbits are still there, accompanied by twelve baby bunnies on his forearms! This is only the beginning, folks. Traditional magic tricks include a water-squirting flower in his lapel, a handkerchief knotted to a seemingly endless string of further handkerchiefs, the last of which is knotted to and pulls off his trousers, and a levitation trick sending Poochini floating to the rafters, then crashing to the stage (similar to the levitation scenes in “Fluke”).

For the remainder of his gags, Avery goes in a new direction, only briefly touched by “Fluke”, and has Spike subjected to an endless steam of instantaneous costume changes, most of them not only upsetting his physical appearance, but affecting the nature of his vocal performance, too. He is transformed into a ballerina, Indian chief, tennis player, prisoner, football quarterback, Chinaman, singing cowboy, square dance caller, three-year-old boy, Hawaiian native, and even (in his funniest costume of all) a drag version of Brazilian bombshell Carmen Miranda – all punctuated at intervals by abusive reappearances of the rabbits. A fed-up paying customer in the balcony even gets into the act, first squirting Poochini with blue ink from a fountain pen, transforming his facial appearance and vocal performance to a near-blackface impersonation of the falsetto crooning of Bill Kenny from the singing quartet, The Ink Spots (in their only-known caricature parody), performing, “Everything I Have Is Yours”, a song hit from MGM’s Joan Crawford/Clark Gable feature, Dancing Lady (1933). To make the parody complete, the customer next drops an anvil on Poochini’s head, rendering him short and squatty, instantly transforming his voice to an impersonation of Ink Spots bass singer, Hoppy Jones, who usually took the middle verses of their arrangements in a conversational talk-sing fashion. For a chance to see the real Ink Spots in performance, check the multiple “Soundie” shorts on the internet, and their extended performance in Abbott and Costello’s “Pardon My Sarong” (Universal, 1942).

For the remainder of his gags, Avery goes in a new direction, only briefly touched by “Fluke”, and has Spike subjected to an endless steam of instantaneous costume changes, most of them not only upsetting his physical appearance, but affecting the nature of his vocal performance, too. He is transformed into a ballerina, Indian chief, tennis player, prisoner, football quarterback, Chinaman, singing cowboy, square dance caller, three-year-old boy, Hawaiian native, and even (in his funniest costume of all) a drag version of Brazilian bombshell Carmen Miranda – all punctuated at intervals by abusive reappearances of the rabbits. A fed-up paying customer in the balcony even gets into the act, first squirting Poochini with blue ink from a fountain pen, transforming his facial appearance and vocal performance to a near-blackface impersonation of the falsetto crooning of Bill Kenny from the singing quartet, The Ink Spots (in their only-known caricature parody), performing, “Everything I Have Is Yours”, a song hit from MGM’s Joan Crawford/Clark Gable feature, Dancing Lady (1933). To make the parody complete, the customer next drops an anvil on Poochini’s head, rendering him short and squatty, instantly transforming his voice to an impersonation of Ink Spots bass singer, Hoppy Jones, who usually took the middle verses of their arrangements in a conversational talk-sing fashion. For a chance to see the real Ink Spots in performance, check the multiple “Soundie” shorts on the internet, and their extended performance in Abbott and Costello’s “Pardon My Sarong” (Universal, 1942).

A special mention of a famous gag sequence from this film is deserved. Avery played on a common problem of film projection in the golden years of cinema – the inevitable hair getting stuck in the projector mechanism, and showing up as a black wiggling line shadowing the image on the screen. Such events would often lead in the good-old-days to unexpected audience participation – whistles, howls, and stamping of feet to signal the projectionist to do something about it – who would usually apply a brush to attempt to jostle the offending strand out of frame, or physically stop the film to pull the thing out manually. Pulling one of his best practical jokes on the audience, Avery had a genuine hair photographed while caught in a projector, then rotoscoped (tracing frame by frame) the image into several shots of the animation, giving the convincing impression that a hair was caught on the film for real. Avery learned his lesson in asking for the rotoscoping, as he had previously tried a near-identical gag in a Warner short, Aviation Vacation (1941), but found that hand-drawn animation couldn’t capture a realistic-looking wiggle or the fluidity of motion necessary to convince that the hair was real. In “Aviation”, also largely defeating the punch of the gag, a character merely joins the audience in shouting for the projectionist to “Get that hair outta there”, and is obliged by the hand-drawn silhouette of a projectionist’s fingers doing so. In “Maestro”, however, Poochini takes matters into his own hands (see the film for yourself to see how its done), for an uproarious audience reaction. (The effect turned out so good that projectionists were being driven crazy by it – believing the hair to be real, and returning many copies of the film to the studio with the complaint that they just couldn’t project it without the hair showing up. MGM had to reissue the cans with special warning labels to the projectionists that the hair was on the film, not in their projectors).

After enduring total humiliation, Poochini finally notices a slip-up, as Mysto’s wig starts to come loose. See the film for the wrap-up. Retaliation is sweet.

Disney continued to offer us occasional glimpses of magic set to music, but only in the setting of feature films. Spawning a song hit (see James Parten’s article, “The Thing-Umma-Bob That Does the Job” on “Needle Drop Notes” subchannel of this website), Cinderella (1950) gave us the Fairy Godmother’s memorable “Bibbidi Bobbidi Boo” while creating Cindy’s coach and gown. The same studio just dodged setting another magical sequence to a song in Sleeping Beauty (1959), choosing in final form to present fairies Flora, Fauna, and Merryweather’s magical birthday party preparations with only an instrumental accompaniment, dropping the lyric to what would on records become, “Sing a Smiling Song”. 1963‘s The Sword in the Stone, in one of the few memorable sequences from an otherwise surprisingly mediocre picture, presented a comical demonstration of magical packing to the Sherman Brothers’ “Higitus Figitus” (with a delightful tongue-twisting lyric of pure poppycock). The Shermans would pen two more magical musical interludes for Disney live action/animation combos, including “A Spoonful of Sugar” for Mary Poppins (1964), and “Substitutiary Locomotion” for Bedknobs and Broomsticks (1971).

I’ll end this installment with a few personal recollections relating to the above. I was fortunate enough to be introduced to both Magic Fluke and Magical Maestro in the setting of a theater screen with a live audience. “Fluke” was screened as the opening title of a night of UPA cartoons many years ago at Los Angeles County Museum of Art, long before its presence on the internet and DVD, when it was considered a rarity alongside other UPA obscurities such as Fudget’s Budget and Willie the Kid. Much earlier, when I was a student at UCLA, “Maestro” was screened from a good 16mm print on a large screen at the school’s old Melnitz Hall theater, under even more fortuitous circumstances – hosted by Tex Avery himself, in a rare public appearance. The Avery program (which was attended by a capacity crowd – although the UPA program was also near capacity) presented a generous assortment of nine cartoons, including “Porky’s Duck Hunt”, “Red Hot Riding Hood”, “Drag-a-Long Droopy”, “Three Little Pups”, “The Counterfeit Cat”, “Uncle Tom’s Cabana” (in the best print I’ve seen to date), “Bad Luck Blackie”, and “King Size Canary” for the finale. Crowd reaction (including from myself, to whom the majority of said titles were first-time viewings) was uproarious, and topped with a well-deserved standing ovation for Mr. Avery.

But it’s notable that, comparing “Fluke” and “Maestro”, I’d say the overall reactions of the two different crowds were almost dead even. Neither film could claim a victory over the other. The only slight edge for the Avery title was the “hair” gag, which surprised the h— out of most of the crowd (again including myself) for the best whoop of the evening. “Fluke”, on the other hand, was the hands-down favorite of the UPA festival, getting resounding howls, and outranking all other films that followed (including “Gerald Mc Boing Boing”) in audience reaction. Artistic style be damned – audiences love a good laugh!

But it’s notable that, comparing “Fluke” and “Maestro”, I’d say the overall reactions of the two different crowds were almost dead even. Neither film could claim a victory over the other. The only slight edge for the Avery title was the “hair” gag, which surprised the h— out of most of the crowd (again including myself) for the best whoop of the evening. “Fluke”, on the other hand, was the hands-down favorite of the UPA festival, getting resounding howls, and outranking all other films that followed (including “Gerald Mc Boing Boing”) in audience reaction. Artistic style be damned – audiences love a good laugh!

A curator must have selected the prints for the Avery show without Tex getting to pre-screen their condition – Tex was a bit nervous and apologized in advance that “Maestro” might be a television-edited print, and that he’d verbally fill in anything missing. As it turned out, the print was complete, and no apologies were necessary. When Avery got his ovation, the personable, self-effacing gentleman commented that before that evening (which was before his name would become a household word from comprehensive biographies, “The Tex Avery Show” on Cartoon Network, and posthumous lifting of his name as a Western character for DIC), he had wondered if he had become “the forgotten man”. He was obviously pleased and emotionally touched that the crowd had proven him wrong.

A final, unforgettable memory I will carry the rest of my life of the Avery appearance was after the show, where Avery lingered for a good long time at the speakers’ table to talk one-on-one with members of the crowd. An enterprising patron (how I wish I’d though of it) surprised everyone by producing a small artist’s pad, and begged Tex to draw him a picture of Droopy. With complete graciousness and without hesitation, Avery agreed. I am over 6 feet tall, so I was able to pick out a choice spot behind Avery’s right shoulder where I could watch closely as he worked at the art pad. His skill, after all his years, was deft. Inside of about three minutes, he produced a Droopy in original 1940’s design, letter perfect, cleaned up, and looking absolutely ready for final ink and paint! I wonder if the lucky person who received this drawing, if anyone knows who that might be, might someday share a scan of this rare gem with all of us on this site, as a momento of a once-in-a-lifetime evening.

Our journeys through animation history will resume in the month of July. Until then, thanks for your attention, and Happy Trails To You!

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Thanks again for another excellent article.

The amount of time you must put in to whittling down titles, “reminder” viewing and the final draft must be giving your jazz time a beating.

I’d like to see a series of posts on the use of certain pieces of music in cartoons; Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2 and Largo al Factotum, already mentioned on this article, are good candidates to start.

I would add that there’s another Avery cartoon that seemed to be inspired by another studio’s cartoon; compare Friz Freleng’s 1946 cartoon “Holiday for Shoestrings” with Avery’s 1950 cartoon “The Peachy Cobbler.” The gags involving cross-eyed elves stand out in particular. I’ll grant you, a number of studios did shoemaker/elf cartoons, but it does strike me that the two have similar themes and the same setup of blackout gags.

Avery’s “Poochini” may superficially parallel the Fluke’s “Foxini,” but more to the point, and brilliantly clever, it’s a pun on opera composer Giacomo Puccini (which is actually pronounced “Poochini”) whose name, along with that of Verdi and Wagne, is virtually synonymous with opera, even to a goodly portion of the general audience.

It’s nice to see Merlin the Magic Mouse get mentioned in this post on Cartoon Research! I would love to see more on Cool Cat and Merlin the Magic Mouse, from the final three years of Warner Bros. Cartoons (1967-1969), in future posts on Cartoon Research someday.

Avery’s hair gag from “Magical Maestro” was used in live action most famously (or infamously) by British comedian Benny Hill towards the end of his April 25, 1984 special. This was during the ending chase sequence were Benny was being chased outside the rounds of a recently-opened hospital by irate staff – and at one point Benny notices a hair caught in a projection gate, and stops the chase long enough to pull the hair out, after which the chase resumes.

Hill seemed to have an affinity for at least some Avery cartoons. His nighttime-soap parody from March 31, 1986, “The Herd,” used a split-screen gag that was in three of Avery’s Schlesinger-era shorts, “Thugs With Dirty Mugs,” “Cross-Country Detours” and “The Bear’s Tale.” A silent March 14, 1979 sketch about the workings of Britain’s National Health Service had a bit where, after a patient had a huge bandage abruptly taken off, he went outside to yell in pain – lifted from two Avery cartoons, “Rock-a-Bye Bear” and “Deputy Droopy.” But a less admirable side to this has to be the early Hill’s Angels numbers from 1980-83; the juxtaposition of T&A displays with the reactions of Hill, Henry McGee, Bob Todd, Jackie Wright et al., seemed to me highly derivative of the formula of Avery’s 1943-49 Red/Wolf shorts (at the time Hill’s show was first syndicated to the U.S. in 1979, the only one of those I saw was the last, “Little Rural Riding Hood”). One gag from such an early Angels segment, from 1980 (in which Jackie distractedly and absent-mindedly slathered butter on his arm while ogling the pulchritude next to

him), seemed like a toned-down version of one of the gags in “Uncle Tom’s Cabana.”

Can anyone else who’s schooled in both Tex Avery and Benny Hill advise as to where else the latter employed gags heavily influenced by the former?