As war approached from foreign lands, a new focus to film production increasingly took center stage – morale-boosting films designed to ignite patriotic spirit, drum up support for the fighting men and for home defense stateside, and to instill negative images of the enemy, either through hatred of the atrocities of war, or by casting the enemy leaders as mockable buffoons. One would think that circus life and atmosphere hardly fit into this mold, and that imagery of such frivolity would seem out of style. Yet, the public still longed for the days of simple entertainments and diversion/escapism from the complexities of the battlefront, and the big show somehow continued to remain a recurring image in animated outings during the war years. In real life, it is likely conscription’s draw-away of manpower had a substantial effect on limiting the caliber and number of acts remaining available for traveling performances. Yet in the animated world, following the oldest of entertainment traditions, the motto remained that the show must go on.

Goofy Groceries (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 3/29/41 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – After years of toiling in black and white to turn out a seemingly endless run of Porky Pig Looney Tunes, Bob Clampett was finally given the green light to produce something in color for the Merrie Melodies series. This effort fell back on the trued-and-true “Midnight in a…” plot mold, in use since the Harman-Ising days, casting its action inside the doors of a corner grocery store closed for the evening. One wonders if the animation for this film was completed in the same order as the placement of shots in the finished film, as the animation seems to progress from rough to well-tooled as the story unfolds. Early shots, including an ersatz Carnation contented cow serenading a “FullaBull” tobacco bull (lampooning Bull Durham tobacco), show the same awkwardness and lack of checking as some comparable scenes from Looney Tunes, with wobbling outlines in a long shot, then the cow’s dimensions seeming to bloat and contract in ways that do not match the perspective of the camera angle or set, and the spots of the bull shifting from misalignment of cels. Yet, later scenes, including a lampoon of Billy Rose’s Aquacade, an escaped gorilla, and an action-packed finale, show Clampett rising to the occasion, with carefully-checked color animation and neat perspective and character design. This film thus looks like an exercise in on-the-job-training, in the course of which we see Clampett growing and developing right before our eyes. The short serves as a learning experience from which its director no doubt benefitted in his later productions.

Goofy Groceries (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 3/29/41 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – After years of toiling in black and white to turn out a seemingly endless run of Porky Pig Looney Tunes, Bob Clampett was finally given the green light to produce something in color for the Merrie Melodies series. This effort fell back on the trued-and-true “Midnight in a…” plot mold, in use since the Harman-Ising days, casting its action inside the doors of a corner grocery store closed for the evening. One wonders if the animation for this film was completed in the same order as the placement of shots in the finished film, as the animation seems to progress from rough to well-tooled as the story unfolds. Early shots, including an ersatz Carnation contented cow serenading a “FullaBull” tobacco bull (lampooning Bull Durham tobacco), show the same awkwardness and lack of checking as some comparable scenes from Looney Tunes, with wobbling outlines in a long shot, then the cow’s dimensions seeming to bloat and contract in ways that do not match the perspective of the camera angle or set, and the spots of the bull shifting from misalignment of cels. Yet, later scenes, including a lampoon of Billy Rose’s Aquacade, an escaped gorilla, and an action-packed finale, show Clampett rising to the occasion, with carefully-checked color animation and neat perspective and character design. This film thus looks like an exercise in on-the-job-training, in the course of which we see Clampett growing and developing right before our eyes. The short serves as a learning experience from which its director no doubt benefitted in his later productions.

Action quickly shifts from general puns on known product names and logos to a subplot involving a circus. A painted crowd flocks to the show on a box of Big Top Popcorn. Cigarettes sticking out of the top of an opened pack issue calliope music with their own puffs of steam. A hound on a box of Barker Dog Food becomes a circus barker, introducing various sideshow acts. A belly dance is performed by a curvaceous stick of Wiggly Gum. The Aquacade sequence is performed with synchronized swimming by the occupants of a sardine can wearing bathing suits. (A water ballet may seem a strange inclusion in a circus cartoon, but real-life producer Billy Rose had a well-known circus connection, having previously produced a show at the New York Hippodrome called “Jumbo”, coupling a Broadway musical loosely based around the famous elephant of the Barnum circus with integrated circus acts woven into the production.) And the girlie acts keep on coming, with a performance of the French Can-Can, danced by actual tomato cans wearing skirts. The camera angle rises to a shelf high above the performance, where a solitary box of animal crackers (complete with its white cloth strap in the style of “Barnum’s Animals” discussed last week) suddenly rips apart at the side, tearing away paper cage bars, to reveal a huge gorilla (drawn normally rather than in the flattened dimensions of a cookie). The gorilla roars at the camera, but pauses to talk like a mild-mannered human, remarking to the audience, “Gosh, ain’t I repulsive?” He looks down, as we see in montage form the images he sees below, of the dancing gum, sardines, and tomato cans. Intrigued, he swings to a light fixture, flicking off the bulb with the pull of a cord. Confused and terrified foods run everywhere, and when the lights come back on, the gorilla has abducted one of the tomato dancers. A rabbit depicted on an unknown product, who has previously Introduced umself as Jack Bunny, becomes a would-be hero, pursuing the ape while riding bareback upon a galloping bottle of horseradish (with a reference to radio star Benny’s western alter-ego, “Buck Benny Rides Again”). He acquires an axe, and attempts to charge the gorilla, but the gorilla picks up a tube full of roman candles, bombarding the axe until it is carved down to a size barely capable of carving a toothpick. The gorilla continues with explosive props, obtaining a king-size firecracker, with which he corners Bunny while lighting the fuse. The first attempt to lampoon Superman in a cartoon (appearing well before Fleischer’s introduction of the straight action-adventure series) has the man of steel appear off a box of soap, not quite flying, but rising to the rescue in charging leaps. But one roar of the gorilla in his face reduces the man of steel to a wailing infant. Just as it seems the gorilla will triumph, a call familiar to radio listeners of the day is heard – a woman’s cry of the name “HENRY!!” (The stock intro to the radio adventures of Henry Aldrich). The gorilla hesitates, then merely hands off the firecracker to Bunny, racing back to the animal cracker box with the obedient reply always heard on the radio show, “Coming, mother.” Bunny wipes his brow at being rid of the gorilla, but forgets he is still holding the firecracker. BOOM! In a repeat of an often-censored gag first used in Porky Pig’s “Jeepers Creepers”, Bunny is turned black from the explosion, looks down at himself, and remarks in Mel Blanc’s best impression of Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, ‘Tattle-tale gray!”

Action quickly shifts from general puns on known product names and logos to a subplot involving a circus. A painted crowd flocks to the show on a box of Big Top Popcorn. Cigarettes sticking out of the top of an opened pack issue calliope music with their own puffs of steam. A hound on a box of Barker Dog Food becomes a circus barker, introducing various sideshow acts. A belly dance is performed by a curvaceous stick of Wiggly Gum. The Aquacade sequence is performed with synchronized swimming by the occupants of a sardine can wearing bathing suits. (A water ballet may seem a strange inclusion in a circus cartoon, but real-life producer Billy Rose had a well-known circus connection, having previously produced a show at the New York Hippodrome called “Jumbo”, coupling a Broadway musical loosely based around the famous elephant of the Barnum circus with integrated circus acts woven into the production.) And the girlie acts keep on coming, with a performance of the French Can-Can, danced by actual tomato cans wearing skirts. The camera angle rises to a shelf high above the performance, where a solitary box of animal crackers (complete with its white cloth strap in the style of “Barnum’s Animals” discussed last week) suddenly rips apart at the side, tearing away paper cage bars, to reveal a huge gorilla (drawn normally rather than in the flattened dimensions of a cookie). The gorilla roars at the camera, but pauses to talk like a mild-mannered human, remarking to the audience, “Gosh, ain’t I repulsive?” He looks down, as we see in montage form the images he sees below, of the dancing gum, sardines, and tomato cans. Intrigued, he swings to a light fixture, flicking off the bulb with the pull of a cord. Confused and terrified foods run everywhere, and when the lights come back on, the gorilla has abducted one of the tomato dancers. A rabbit depicted on an unknown product, who has previously Introduced umself as Jack Bunny, becomes a would-be hero, pursuing the ape while riding bareback upon a galloping bottle of horseradish (with a reference to radio star Benny’s western alter-ego, “Buck Benny Rides Again”). He acquires an axe, and attempts to charge the gorilla, but the gorilla picks up a tube full of roman candles, bombarding the axe until it is carved down to a size barely capable of carving a toothpick. The gorilla continues with explosive props, obtaining a king-size firecracker, with which he corners Bunny while lighting the fuse. The first attempt to lampoon Superman in a cartoon (appearing well before Fleischer’s introduction of the straight action-adventure series) has the man of steel appear off a box of soap, not quite flying, but rising to the rescue in charging leaps. But one roar of the gorilla in his face reduces the man of steel to a wailing infant. Just as it seems the gorilla will triumph, a call familiar to radio listeners of the day is heard – a woman’s cry of the name “HENRY!!” (The stock intro to the radio adventures of Henry Aldrich). The gorilla hesitates, then merely hands off the firecracker to Bunny, racing back to the animal cracker box with the obedient reply always heard on the radio show, “Coming, mother.” Bunny wipes his brow at being rid of the gorilla, but forgets he is still holding the firecracker. BOOM! In a repeat of an often-censored gag first used in Porky Pig’s “Jeepers Creepers”, Bunny is turned black from the explosion, looks down at himself, and remarks in Mel Blanc’s best impression of Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, ‘Tattle-tale gray!”

Dumbo (Disney/RKO, 10/23/41) – Perhaps one of the best remembered of all circus cartoons, and a personal favorite of Disney (despite its ultra-short running time as compared to most Disney features). Running time wasn’t the only shortcut, as the film is also remarkably short on visual effects animation, most scenes more akin to the product of the short-subjects division, lacking in the breakthrough spectacle of Fantasia, Pinocchio, and the later Banbi. Disney, who allegedly criticized Harman-Ising’s “To Spring” as too gaudy in throwing colors around, commits the same sin on a lesser scale in a choice of basic primary color schemes for such sequences as the circus parade, presented with no shading or modeling, giving the impression (especially on a big screen) of being churned out in a hurry without care for detail. All but the night scenes of Casey Jr. the circus train continue in this pattern. Only two sequences attempt to make up for this – the well-shaded and moody-colored “Song of the Roustabouts” number (as the cast erect the circus tent during a driving rainstorm), and the optically-creative (though largely dependent upon basic outline animation) “Pink Elephants on Parade”. Labor issues at the studio were likely contributory to these cutbacks – but another factor was that Disney had lost money on Pinocchio due to its lavishness and budget, and certainly knew he was also taking a gamble in producing a feature from an original story instead of a well-known fairy tale with instant audience recognition. Disney was thus putting economics ahead of his personal tastes, and pushing the envelope to see just how inexpensively he could produce a feature to ensure a box-office profit. The plan worked, and the film was a success for its charm and story presentation alone. However, it was not a model for success that Disney would follow religiously. Bambi was a return to lavishness, and initially, another money-loser. Disney would spend most of the later ‘40’s continuing to budget-cut with his package films, yet get creative when he wanted to with his special processes for “Song of the South”, and lavish again in his feature output of the 1950’s.

Dumbo (Disney/RKO, 10/23/41) – Perhaps one of the best remembered of all circus cartoons, and a personal favorite of Disney (despite its ultra-short running time as compared to most Disney features). Running time wasn’t the only shortcut, as the film is also remarkably short on visual effects animation, most scenes more akin to the product of the short-subjects division, lacking in the breakthrough spectacle of Fantasia, Pinocchio, and the later Banbi. Disney, who allegedly criticized Harman-Ising’s “To Spring” as too gaudy in throwing colors around, commits the same sin on a lesser scale in a choice of basic primary color schemes for such sequences as the circus parade, presented with no shading or modeling, giving the impression (especially on a big screen) of being churned out in a hurry without care for detail. All but the night scenes of Casey Jr. the circus train continue in this pattern. Only two sequences attempt to make up for this – the well-shaded and moody-colored “Song of the Roustabouts” number (as the cast erect the circus tent during a driving rainstorm), and the optically-creative (though largely dependent upon basic outline animation) “Pink Elephants on Parade”. Labor issues at the studio were likely contributory to these cutbacks – but another factor was that Disney had lost money on Pinocchio due to its lavishness and budget, and certainly knew he was also taking a gamble in producing a feature from an original story instead of a well-known fairy tale with instant audience recognition. Disney was thus putting economics ahead of his personal tastes, and pushing the envelope to see just how inexpensively he could produce a feature to ensure a box-office profit. The plan worked, and the film was a success for its charm and story presentation alone. However, it was not a model for success that Disney would follow religiously. Bambi was a return to lavishness, and initially, another money-loser. Disney would spend most of the later ‘40’s continuing to budget-cut with his package films, yet get creative when he wanted to with his special processes for “Song of the South”, and lavish again in his feature output of the 1950’s.

The basic gimmick of the storyline for this film – a little elephant who could fly – could hardly be called original. Especially if you are a fan of the early work of Paul Terry, it was essentially a rule of thumb at the studio that every elephant could fly, by merely flapping its ears. Such scenes would appear for a laugh again and again – one of my favorite examples being “South Pole or Bust” (1934), where a team of flying elephants invent the process of aerial refueling by sucking up airplane fuel through their trunks, then pumping it into a moving plane through a funnel. Even Stan Laurel had incorporated the stock gag into one animated scene of the Laurel and Hardy caveman short, “Flying Elephants” (1928). One wonders if this titling suggests that the phrase had broader meaning for a time than the Paul Terry gag, perhaps suggesting intoxication in the same manner as pink elephants, though I can find no discussion on internet blogs of the phrase’s use apart from the above-referenced films. The gag had finally fallen out of vogue for a few years when Dumbo was made, so Disney perhaps hoped people had forgotten it. (Yet, as discussed below, there is the odd coincidence in time of a popular book by Theodor “Seuss” Geisel culminating in a flying elephant, which may or may not also have been an influence on the Disney story, and would shortly after Disney’s become a film of its own.) The entire Disney project, then, amounts to coming up with a backstory to explain this incongruous phenomenon which, in the hands of others, had amounted only to a visually-jarring throwaway gag. The answer to this riddle didn’t develop overnight. Early storyboard treatments show Dumbo surrounded by an entirely-different cast, appearing to include a robin as his friend in place of Timothy Mouse (a choice of partnerships far less natural than the final film’s playing upon defying the old cliche of elephants being scared of a mouse), and a wise old owl as his sage instructor in place of the crows (such owl having to wait until the next production to make his appearance in “Bambi”). Yes, Dumbo was even supposed to talk (in the final film, he is a purely pantomime character, except for one sneeze and some trunk snorts). So, what chemistry made the film finally click? Some perseverance, persistent rewriting, and perhaps a touch of Disney’s own knack of seeking perfection in a storyline – settling on a story of a little underdog who, with the help of one faithful friend, battles adversity and prejudice to triumph and become a world sensation. A lofty and universally-appealing theme indeed, when you consider that it is here solely to explain one wild sight gag that started it all.

The basic gimmick of the storyline for this film – a little elephant who could fly – could hardly be called original. Especially if you are a fan of the early work of Paul Terry, it was essentially a rule of thumb at the studio that every elephant could fly, by merely flapping its ears. Such scenes would appear for a laugh again and again – one of my favorite examples being “South Pole or Bust” (1934), where a team of flying elephants invent the process of aerial refueling by sucking up airplane fuel through their trunks, then pumping it into a moving plane through a funnel. Even Stan Laurel had incorporated the stock gag into one animated scene of the Laurel and Hardy caveman short, “Flying Elephants” (1928). One wonders if this titling suggests that the phrase had broader meaning for a time than the Paul Terry gag, perhaps suggesting intoxication in the same manner as pink elephants, though I can find no discussion on internet blogs of the phrase’s use apart from the above-referenced films. The gag had finally fallen out of vogue for a few years when Dumbo was made, so Disney perhaps hoped people had forgotten it. (Yet, as discussed below, there is the odd coincidence in time of a popular book by Theodor “Seuss” Geisel culminating in a flying elephant, which may or may not also have been an influence on the Disney story, and would shortly after Disney’s become a film of its own.) The entire Disney project, then, amounts to coming up with a backstory to explain this incongruous phenomenon which, in the hands of others, had amounted only to a visually-jarring throwaway gag. The answer to this riddle didn’t develop overnight. Early storyboard treatments show Dumbo surrounded by an entirely-different cast, appearing to include a robin as his friend in place of Timothy Mouse (a choice of partnerships far less natural than the final film’s playing upon defying the old cliche of elephants being scared of a mouse), and a wise old owl as his sage instructor in place of the crows (such owl having to wait until the next production to make his appearance in “Bambi”). Yes, Dumbo was even supposed to talk (in the final film, he is a purely pantomime character, except for one sneeze and some trunk snorts). So, what chemistry made the film finally click? Some perseverance, persistent rewriting, and perhaps a touch of Disney’s own knack of seeking perfection in a storyline – settling on a story of a little underdog who, with the help of one faithful friend, battles adversity and prejudice to triumph and become a world sensation. A lofty and universally-appealing theme indeed, when you consider that it is here solely to explain one wild sight gag that started it all.

The film begins with the delivery by stork of baby animals to the winter headquarters of a circus in Florida. Everyone gets theirs except Mrs. Jimbo, whose baby is late due to its weight, and is ultimately delivered to her while on board Casey Jr., the circus train. The other elephants are charmed by the infant’s cuteness, until a sneeze unfurls a set of ears about three times bigger than a normal elephant (even larger than those of an African elephant, which are naturally more sizeable than those of the more common and docile Indian elephant). The baby (Jumbo Jr.) becomes a laughing stock, and one of the other elephants jeeringly nicknames him “Dumbo” – a moniker that sticks for life. Mother lovingly defends her child, keeping the other elephants away, and tenderly caring for the affectionate and unknowing baby. The circus begins to play its circuit of towns, enlisting Dumbo’s minor help, along with the substantial contribution of the other elephants in the show, in the arduous process of raising the circus tent, then including Dumbo in the introductory parade (where he stumbles into a mud puddle, resulting in his first rounds of ridiculing laughter from the public).

The film begins with the delivery by stork of baby animals to the winter headquarters of a circus in Florida. Everyone gets theirs except Mrs. Jimbo, whose baby is late due to its weight, and is ultimately delivered to her while on board Casey Jr., the circus train. The other elephants are charmed by the infant’s cuteness, until a sneeze unfurls a set of ears about three times bigger than a normal elephant (even larger than those of an African elephant, which are naturally more sizeable than those of the more common and docile Indian elephant). The baby (Jumbo Jr.) becomes a laughing stock, and one of the other elephants jeeringly nicknames him “Dumbo” – a moniker that sticks for life. Mother lovingly defends her child, keeping the other elephants away, and tenderly caring for the affectionate and unknowing baby. The circus begins to play its circuit of towns, enlisting Dumbo’s minor help, along with the substantial contribution of the other elephants in the show, in the arduous process of raising the circus tent, then including Dumbo in the introductory parade (where he stumbles into a mud puddle, resulting in his first rounds of ridiculing laughter from the public).

Things come to a head when a group of heartless kids (one who has his own set of ears big enough to earn him the same type of insults) poke fun at Dumbo inside the menagerie, then object as Mother attempts to hide her son behind her. The kids reach between Mother’s legs, dragging Dumbo out by the ear, and cruelly blow in Dumbo’s ear as well. Mother defensively grabs up one of the kids with her trunk, then begins to spank his rear with it. The other kids run in panic, as the ringmaster emerges to see what is the commotion. “Surround her”, he orders, and in a violent confrontation, with one trainer and the ringmaster tossed about in the strong grip of Mother’s trunk, Mother is shackled by the ankles, and dragged away to a solitary barred circus wagon, where she is branded by signs as a mad elephant. Dumbo is separated from his mom, and remains a solitary figure in the elephant enclosure, the other elephants branding him a freak and blaming him as the cause of the unfortunate events.

Things come to a head when a group of heartless kids (one who has his own set of ears big enough to earn him the same type of insults) poke fun at Dumbo inside the menagerie, then object as Mother attempts to hide her son behind her. The kids reach between Mother’s legs, dragging Dumbo out by the ear, and cruelly blow in Dumbo’s ear as well. Mother defensively grabs up one of the kids with her trunk, then begins to spank his rear with it. The other kids run in panic, as the ringmaster emerges to see what is the commotion. “Surround her”, he orders, and in a violent confrontation, with one trainer and the ringmaster tossed about in the strong grip of Mother’s trunk, Mother is shackled by the ankles, and dragged away to a solitary barred circus wagon, where she is branded by signs as a mad elephant. Dumbo is separated from his mom, and remains a solitary figure in the elephant enclosure, the other elephants branding him a freak and blaming him as the cause of the unfortunate events.

Enter Timothy Mouse, a little rodent with a Brooklyn accent who has somehow acquired a miniature bright red circus outfit of his own, and, though there is no evidence of his being a formal part of the show, tags along with the traveling troupe in search of its abundant food supply of peanuts. Overhearing the gossip of the elephants, Timothy becomes aware of the existence of Dumbo, and of the other elephants’ continuing jokes about “ears only a mother coild love” – yet, without sign of malice or prejudice, Timothy expresses to himself his own genuine opinion on the subject. “What’s the matter with his ears? I don’t see nothin’ wrong with ‘em. I think they’re cute.” Timothy observes the elephants turning their rears to Dumbo to exclude him from their circle, and in comic underplay, describes the incident as “giving him the cold shoulder”. Realizing Dumbo hasn’t a friend in the world, Timothy decides to stand up for Dumbo’s rights, and uses his natural advantage to put the elephants in their place, marching directly into their circle. “A mouse!”, screams the elephant pack, as the pachyderms scramble for the most unlikely places of safety, up the tent poles and the like. “So ya’ like to pick on little guys, eh? Well, why don’t you pick on me?” taunts Timothy. Dumbo is now defended from further abuse by the herd. Dumbo, however, is naturally scared too, until Timothy wins his confidence with ideas of how possibly to get his mother “out of the clink.” His plan – build an act, to make Dumbo a headliner. “Dumbo the Great”, shouts Timothy – then pauses with an afterthought – “The great what?”

Enter Timothy Mouse, a little rodent with a Brooklyn accent who has somehow acquired a miniature bright red circus outfit of his own, and, though there is no evidence of his being a formal part of the show, tags along with the traveling troupe in search of its abundant food supply of peanuts. Overhearing the gossip of the elephants, Timothy becomes aware of the existence of Dumbo, and of the other elephants’ continuing jokes about “ears only a mother coild love” – yet, without sign of malice or prejudice, Timothy expresses to himself his own genuine opinion on the subject. “What’s the matter with his ears? I don’t see nothin’ wrong with ‘em. I think they’re cute.” Timothy observes the elephants turning their rears to Dumbo to exclude him from their circle, and in comic underplay, describes the incident as “giving him the cold shoulder”. Realizing Dumbo hasn’t a friend in the world, Timothy decides to stand up for Dumbo’s rights, and uses his natural advantage to put the elephants in their place, marching directly into their circle. “A mouse!”, screams the elephant pack, as the pachyderms scramble for the most unlikely places of safety, up the tent poles and the like. “So ya’ like to pick on little guys, eh? Well, why don’t you pick on me?” taunts Timothy. Dumbo is now defended from further abuse by the herd. Dumbo, however, is naturally scared too, until Timothy wins his confidence with ideas of how possibly to get his mother “out of the clink.” His plan – build an act, to make Dumbo a headliner. “Dumbo the Great”, shouts Timothy – then pauses with an afterthought – “The great what?”

By coincidence, the ringmaster, heard through his dressing tent wall, has an idea for a sensational act that might just fit the bill for Timothy’s needs – but is lacking a climax. The ringmaster envisions elephants balancing atop other elephants, to form a living pyramid of pachyderms. (I believe some real-life circus poster of the period depicted such an image, though it is highly doubtful that such an act ever occurred.) Except once the elephants are up there, the ringmaster doesn’t know how to end the act with a bang. Timothy, however sees possibilities for Dumbo. Creeping into the ringmaster’s tent at night, Timothy whispers into his ear the suggestion that Dumbo spring from a springboard, land on a platform at the pinnacle of the pyramid, and wave a flag. Thinking that he has received an inspiration in a dream, the ringmaster places the act into production. It is never seen on screen whether the feat goes through any advance rehearsals, or is simply commanded of the elephants to perform before a live audience. Timothy and Dumbo wait in the wings, as the mammoths clumsily and precariously pile one atop another, with their leader at the bottom of the stack, balancing atop a large ball. Timothy asks Dumbo to show him just how he will run for the springboard launch, but fails to reckon upon the length of Dumbo’s ears, which trip the tyke up. As an emergency measure, Timothy ties the ends of Dumbo’s ears together in a knot above his head. The strange sight brings laughter from the crowd as Dumbo is introduced, causing the little elephant to instantly lose confidence. The only way Timothy can get Dumbo not to miss his cue is to stick him in the rear with a pin. Dumbo gallops forward, but the vibration of his run loosens the knot in his ears. Dumbo stumbles again, misses the springboard entirely, and slams directly into the ball supporting the elephants. A scene of living disaster results, as the pyramid becomes mobile atop the ball, and elephants begin to be thrown everywhere. Dumbo himself is almost squashed by the oncoming ball, as the lead elephant shouts, “Out of my way, assassin.” A falling elephant clutches to the main pole supporting the tent, and the entire big top falls. Through a small hole in the collapsed canvas, the weary trunk of Dumbo emerges to wave his flag, as his small flagpole snaps in two.

By coincidence, the ringmaster, heard through his dressing tent wall, has an idea for a sensational act that might just fit the bill for Timothy’s needs – but is lacking a climax. The ringmaster envisions elephants balancing atop other elephants, to form a living pyramid of pachyderms. (I believe some real-life circus poster of the period depicted such an image, though it is highly doubtful that such an act ever occurred.) Except once the elephants are up there, the ringmaster doesn’t know how to end the act with a bang. Timothy, however sees possibilities for Dumbo. Creeping into the ringmaster’s tent at night, Timothy whispers into his ear the suggestion that Dumbo spring from a springboard, land on a platform at the pinnacle of the pyramid, and wave a flag. Thinking that he has received an inspiration in a dream, the ringmaster places the act into production. It is never seen on screen whether the feat goes through any advance rehearsals, or is simply commanded of the elephants to perform before a live audience. Timothy and Dumbo wait in the wings, as the mammoths clumsily and precariously pile one atop another, with their leader at the bottom of the stack, balancing atop a large ball. Timothy asks Dumbo to show him just how he will run for the springboard launch, but fails to reckon upon the length of Dumbo’s ears, which trip the tyke up. As an emergency measure, Timothy ties the ends of Dumbo’s ears together in a knot above his head. The strange sight brings laughter from the crowd as Dumbo is introduced, causing the little elephant to instantly lose confidence. The only way Timothy can get Dumbo not to miss his cue is to stick him in the rear with a pin. Dumbo gallops forward, but the vibration of his run loosens the knot in his ears. Dumbo stumbles again, misses the springboard entirely, and slams directly into the ball supporting the elephants. A scene of living disaster results, as the pyramid becomes mobile atop the ball, and elephants begin to be thrown everywhere. Dumbo himself is almost squashed by the oncoming ball, as the lead elephant shouts, “Out of my way, assassin.” A falling elephant clutches to the main pole supporting the tent, and the entire big top falls. Through a small hole in the collapsed canvas, the weary trunk of Dumbo emerges to wave his flag, as his small flagpole snaps in two.

Having no place else to put him in the show, Dumbo is assigned the humiliating task of portraying a baby trapped in the window of a burning building in a clown fireman act. The act ends with a clown paddling Dumbo in the rear, knocking him off his platform high above the arena toward a waiting team of clowns holding a fireman’s net below. However, the net is only a hoop made of paper, and Dumbo goes right through it, landing in a tub fill of sticky paste concealed below. The clowns celebrate that night the success of their new act with champagne, then begin tossing about ideas to improve the performance. They conclude that ‘simple mathematics” would make the act funnier if the elephant dived from even more dizzying heights. They settle upon the round figure of a 1,000-foot jump. “Be careful, you’ll hurt the little guy”, comments one conscientious clown. He is soon drowned out by the comments, “Aw, go on, elephants ain’t got no feelins’.” “Naw, they’re made of rubber.” As the clowns leave their tent, with intention of hitting the boss for a raise with their creativity, one jostles one of the champagne bottles, causing its contents to empty outside the tent into a watering pail. A saddened Dumbo and Timothy choose this pail to drink from, and instantly become intoxicated. They hallucinate, leading into the aforementioned “Punk Elephants on Parade” dream sequence, well-remembered by most Disney fans. Their activities for the remainder of the night remain unseen by the camera – but when they awaken the next morning, they are miles from the big top, resting high in the branches of a tall tree. Awakened by a quartet of curious crows, the startled mouse and elephant fall awkwardly to the ground, rising with the mystery of how they got up there in the first place. One of the crows (voiced by Cliff Edwards) laughingly calls after them, “Maybe you-all flew up.” Timothy first brushes off this suggestion as a bad joke, then has second thoughts. It is the only possible explanation. Looking at Dumbo’s ears, Timothy realizes they might be perfect wings. But how to convince the doubtful and fearful Dumbo that he can really perform such a stunt? The crows suggest using psychology, and, plucking a tail feather out of one of their members, suggest that Timothy pass it off to Dumbo as a “magic feather” giving the power of flight. Dumbo is led to a high cliff, clutching the feather n his trunk, and told to flap his ears as hard as he can. A mighty cloud of dust is blown up from the draft, and when the dust clears, Dumbo, and Timothy riding in his hat brim, are airborne.

Having no place else to put him in the show, Dumbo is assigned the humiliating task of portraying a baby trapped in the window of a burning building in a clown fireman act. The act ends with a clown paddling Dumbo in the rear, knocking him off his platform high above the arena toward a waiting team of clowns holding a fireman’s net below. However, the net is only a hoop made of paper, and Dumbo goes right through it, landing in a tub fill of sticky paste concealed below. The clowns celebrate that night the success of their new act with champagne, then begin tossing about ideas to improve the performance. They conclude that ‘simple mathematics” would make the act funnier if the elephant dived from even more dizzying heights. They settle upon the round figure of a 1,000-foot jump. “Be careful, you’ll hurt the little guy”, comments one conscientious clown. He is soon drowned out by the comments, “Aw, go on, elephants ain’t got no feelins’.” “Naw, they’re made of rubber.” As the clowns leave their tent, with intention of hitting the boss for a raise with their creativity, one jostles one of the champagne bottles, causing its contents to empty outside the tent into a watering pail. A saddened Dumbo and Timothy choose this pail to drink from, and instantly become intoxicated. They hallucinate, leading into the aforementioned “Punk Elephants on Parade” dream sequence, well-remembered by most Disney fans. Their activities for the remainder of the night remain unseen by the camera – but when they awaken the next morning, they are miles from the big top, resting high in the branches of a tall tree. Awakened by a quartet of curious crows, the startled mouse and elephant fall awkwardly to the ground, rising with the mystery of how they got up there in the first place. One of the crows (voiced by Cliff Edwards) laughingly calls after them, “Maybe you-all flew up.” Timothy first brushes off this suggestion as a bad joke, then has second thoughts. It is the only possible explanation. Looking at Dumbo’s ears, Timothy realizes they might be perfect wings. But how to convince the doubtful and fearful Dumbo that he can really perform such a stunt? The crows suggest using psychology, and, plucking a tail feather out of one of their members, suggest that Timothy pass it off to Dumbo as a “magic feather” giving the power of flight. Dumbo is led to a high cliff, clutching the feather n his trunk, and told to flap his ears as hard as he can. A mighty cloud of dust is blown up from the draft, and when the dust clears, Dumbo, and Timothy riding in his hat brim, are airborne.

The two decide to spring Dumbo’s newfound power upon the crowds at tonight’s performance, where, indeed, the clowns have raised the platform to 1,000 feet. Dumbo dives, but the feather is blown out of the grasp of his trunk on the way down. Dumbo freezes in panic, and the equally-panicked Timothy, sensing their impending doom, confesses regarding his white lie. “The magic feather was just a gag. You can fly. Honest you can. Hurry, open them up!” Inches shy of the ground, Dumbo curves into a soaring pattern over the arena. With victory now in their grasp, Timothy takes command, directing Dumbo into a power dive. Dumbo buzzes the spectators and performers alike in one pass after another – driving the clowns into their own fire, the ringmaster into a bucket of water, and peppering the elephants who criticized him wuth a barrage of peanuts sucked up by Dumbo’s trunk from a vendor’s wagon. Dumbo is an overnight sensation and media marvel, leading to a Hollywood contract under his new manager Timothy, record-breaking altitude flights, and even a new design for wartime bombers with noses resembling his likeness, dubbed “Dumbobombers for Defense.” Most important of all, Mrs Jumbo now travels in style, freed and as the co-occupant of a private car with her son at the end of the circus train. The crows wave goodbye at the close of the film, happy with the knowledge that one of them has gotten Dumbo’s autograph.

The two decide to spring Dumbo’s newfound power upon the crowds at tonight’s performance, where, indeed, the clowns have raised the platform to 1,000 feet. Dumbo dives, but the feather is blown out of the grasp of his trunk on the way down. Dumbo freezes in panic, and the equally-panicked Timothy, sensing their impending doom, confesses regarding his white lie. “The magic feather was just a gag. You can fly. Honest you can. Hurry, open them up!” Inches shy of the ground, Dumbo curves into a soaring pattern over the arena. With victory now in their grasp, Timothy takes command, directing Dumbo into a power dive. Dumbo buzzes the spectators and performers alike in one pass after another – driving the clowns into their own fire, the ringmaster into a bucket of water, and peppering the elephants who criticized him wuth a barrage of peanuts sucked up by Dumbo’s trunk from a vendor’s wagon. Dumbo is an overnight sensation and media marvel, leading to a Hollywood contract under his new manager Timothy, record-breaking altitude flights, and even a new design for wartime bombers with noses resembling his likeness, dubbed “Dumbobombers for Defense.” Most important of all, Mrs Jumbo now travels in style, freed and as the co-occupant of a private car with her son at the end of the circus train. The crows wave goodbye at the close of the film, happy with the knowledge that one of them has gotten Dumbo’s autograph.

Horton Hatches the Egg (4/11/42) – Strange coincidence? A children’s book, published in 1940, that became a best-seller, also involving an elephant who could fly? Its copyright appears to be a year following the literary work that formed the basis for Dumbo, though it would seem that Disney could hardly have been unaware of it in following children’s literature. Which came first, the Dumbo, or the Egg? Disney’s gestation period for Dumbo would indicate early development was likely already in the works when Horton was published. Seuss was not yet a force in animation, and still fairly new in literature, so it was unlikely that Seuss was a target for pre-publication spying by anyone in the Disney organization or in the camps of Dumbo’s original literary work. Seuss, on the other hand, would have little reason for spying on Disney, and his explanation of the creation of an “elephant-bird” through pure devotion and mother love is certainly different than Disney’s concept. Did Seuss, however, know of the original children’s book on which Dumbo was based when conceiving his story? So, how did two creative geniuses come up with flying elephants within such a short time of one another? I’m tempted to blame mere happenstance on this one – and a common memory of those creaky old Paul Terry cartoons, or even Stan Laurel. However, that’s not to say that the literary success of Horton might not have bolstered Disney’s confidence in bringing Dumbo to the screen – or that the screen success of Dumbo might not have had a role in driving Seuss and Warner Brothers into their first collaborative effort to bring a Seuss story to the field of animation.

Horton Hatches the Egg (4/11/42) – Strange coincidence? A children’s book, published in 1940, that became a best-seller, also involving an elephant who could fly? Its copyright appears to be a year following the literary work that formed the basis for Dumbo, though it would seem that Disney could hardly have been unaware of it in following children’s literature. Which came first, the Dumbo, or the Egg? Disney’s gestation period for Dumbo would indicate early development was likely already in the works when Horton was published. Seuss was not yet a force in animation, and still fairly new in literature, so it was unlikely that Seuss was a target for pre-publication spying by anyone in the Disney organization or in the camps of Dumbo’s original literary work. Seuss, on the other hand, would have little reason for spying on Disney, and his explanation of the creation of an “elephant-bird” through pure devotion and mother love is certainly different than Disney’s concept. Did Seuss, however, know of the original children’s book on which Dumbo was based when conceiving his story? So, how did two creative geniuses come up with flying elephants within such a short time of one another? I’m tempted to blame mere happenstance on this one – and a common memory of those creaky old Paul Terry cartoons, or even Stan Laurel. However, that’s not to say that the literary success of Horton might not have bolstered Disney’s confidence in bringing Dumbo to the screen – or that the screen success of Dumbo might not have had a role in driving Seuss and Warner Brothers into their first collaborative effort to bring a Seuss story to the field of animation.

Circus action is at a bare minimum in this film, as the largely immobile Horton is the action. Horton, charged with the duty of sitting on a bird’s egg in a tree nest while a lazy mother (Maisy) abandons her egg-sitting duties for a vacation in Palm Beach, simply sits and sits and sits, a picture of devotion, through ridicule, torrential changes of weather, and even the danger of an elephant gun wielded by a trio of hunters. “An elephant’s faithful, one hundred percent”, repeats the weary but determined pachyderm. The hunters decide the elephant is worth more alive as a hilarious circus attraction, and saw off the tree, transporting Horton and nest by ship to the States for booking by a circus at 10 cents a peek. Horton sits day after day in a hot, noisy tent as spectators gawk and laugh. Then, unknowing of Horton’s presence, Maisy spots the big top, and decides to go to the show. She flies in the tent, running smack-dab into the side of Horton. “Good gracious! I’ve seen you before”, she squawks. Horton has neither time, nor can find the words, to explain what he’s been through, when all of a sudden, the egg begins to hatch, after being warmed by Horton for 51 weeks. Having done none of this nurturing herself, Maisy nevertheless objects when she hears Horton tenderly refer to the cracking orb as “my egg”, and demands that Horton surrender the egg back to her, now that the work is all done. Horton raises no fuss to the ungrateful bird, and begins to back down – until nature decides who is the rightful owner. The eggshell cracks, and out darts a small, yet rotund, flying whizz. Something brand new – an elephant-bird, created from the strength of Horton’s love. Design is different from Dumbo, as this creature has physical wings attached upon the body of an elephant, rather than flying by flapping its ears – so there was little danger of Disney claiming a foul. Maisy’s treachery is foiled, as the little hatchling instantly sidles up to and bonds with “mother” Horton, and the circus, rather than keep Horton and son in profitable captivity, charitably allows the two of them to be shipped home to their natural jungle habitat. (Somehow, I feel these two should consider themselves lucky the circus was not presided over by P.T. Barnum, with whom I am sure any thought of future freedom from captivity would have been impossible, so long as the Rubes would continue to pay for a look.)

Circus action is at a bare minimum in this film, as the largely immobile Horton is the action. Horton, charged with the duty of sitting on a bird’s egg in a tree nest while a lazy mother (Maisy) abandons her egg-sitting duties for a vacation in Palm Beach, simply sits and sits and sits, a picture of devotion, through ridicule, torrential changes of weather, and even the danger of an elephant gun wielded by a trio of hunters. “An elephant’s faithful, one hundred percent”, repeats the weary but determined pachyderm. The hunters decide the elephant is worth more alive as a hilarious circus attraction, and saw off the tree, transporting Horton and nest by ship to the States for booking by a circus at 10 cents a peek. Horton sits day after day in a hot, noisy tent as spectators gawk and laugh. Then, unknowing of Horton’s presence, Maisy spots the big top, and decides to go to the show. She flies in the tent, running smack-dab into the side of Horton. “Good gracious! I’ve seen you before”, she squawks. Horton has neither time, nor can find the words, to explain what he’s been through, when all of a sudden, the egg begins to hatch, after being warmed by Horton for 51 weeks. Having done none of this nurturing herself, Maisy nevertheless objects when she hears Horton tenderly refer to the cracking orb as “my egg”, and demands that Horton surrender the egg back to her, now that the work is all done. Horton raises no fuss to the ungrateful bird, and begins to back down – until nature decides who is the rightful owner. The eggshell cracks, and out darts a small, yet rotund, flying whizz. Something brand new – an elephant-bird, created from the strength of Horton’s love. Design is different from Dumbo, as this creature has physical wings attached upon the body of an elephant, rather than flying by flapping its ears – so there was little danger of Disney claiming a foul. Maisy’s treachery is foiled, as the little hatchling instantly sidles up to and bonds with “mother” Horton, and the circus, rather than keep Horton and son in profitable captivity, charitably allows the two of them to be shipped home to their natural jungle habitat. (Somehow, I feel these two should consider themselves lucky the circus was not presided over by P.T. Barnum, with whom I am sure any thought of future freedom from captivity would have been impossible, so long as the Rubes would continue to pay for a look.)

Happy Circus Days (Terrytoons/Fox, 1/23/42 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – When CBS acquired the Terrytoons library, the sheer number of cartoons included necessitated that the films be divided up into multiple distribution packages. Despite initial broadcast in black and whire, those color films with star-caliber characters Heckle and Jeckle, Gandy Goose, Dinky, and Little Roquefort were initially shown on the short-lived prime-time “CBS Cartoon Theater”, while most other color items and select black and white cartoons found their way to the Saturday morning “Mighty Mouse Playhouse”. The earliest of the library were sandwiched between Farmer Al Falfa cartoons in a syndicated package of his own. Many of the later and better black and whites appeared, however, on a curiosity of a package known as “Barker Bill’s Cartoon Show”. For this package, a new piece of short animation was created, re-servicing a calliope tune heard in “The Magic Shell” with a new lyric to describe the title character. Who was Barker Bill? Not a mere invention of the syndicators, he was actually a real Terrytoons character who had appeared in only one film – and this is the title. Oddly, as this film was made in color, it is unlikely it ever appeared on Barker Bill’s own show.

Happy Circus Days (Terrytoons/Fox, 1/23/42 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – When CBS acquired the Terrytoons library, the sheer number of cartoons included necessitated that the films be divided up into multiple distribution packages. Despite initial broadcast in black and whire, those color films with star-caliber characters Heckle and Jeckle, Gandy Goose, Dinky, and Little Roquefort were initially shown on the short-lived prime-time “CBS Cartoon Theater”, while most other color items and select black and white cartoons found their way to the Saturday morning “Mighty Mouse Playhouse”. The earliest of the library were sandwiched between Farmer Al Falfa cartoons in a syndicated package of his own. Many of the later and better black and whites appeared, however, on a curiosity of a package known as “Barker Bill’s Cartoon Show”. For this package, a new piece of short animation was created, re-servicing a calliope tune heard in “The Magic Shell” with a new lyric to describe the title character. Who was Barker Bill? Not a mere invention of the syndicators, he was actually a real Terrytoons character who had appeared in only one film – and this is the title. Oddly, as this film was made in color, it is unlikely it ever appeared on Barker Bill’s own show.

A little boy and his dog awaken to the music of a passing circus parade on the street. Those of you who have been following these posts will instantly recognize the first performer in the parade as someone we’ve seen before, now retraced and colored in. It is Slippery Sam, with his face now redesigned and masked in clown makeup, playing the same yowling cat calliope which opened the parade in “Just a Clown”. Assorted other new performers march behind him, including a clown with an electric bulb in his nose, and an elephant who plays two drums fastened on his sides with his tail, and carries two saxophone-blowing monkeys in his “trunk” (shaped like a steamer trunk). The boy hastily washes in the same manner as various tots in films of the crosstown rivals at Fleischer’s – by applying a drop of water apiece to each of his respective cheeks. Then the boy and his dog slide down the staircase banister, causing a posed statue mounted on the railing at the foot of the stairs to leap out of the way, as the boy and dog sail past, exiting the house by puncturing silhouette-shaped holes of themselves through the front door. Arriving at the circus grounds, they listen to the spiel of Barker Bill, who provides verbal descriptions of the various acts inside, while we in the audience receive actual glimpses of the performers. Gigantica, world’s largest ape. A roller-skating jackass, who trips up his skating trainer, then laughs at him like Gandy Goose. Mademoiselle Petite – a hippo redrawing of the same fat lady pig trapeze artist who got repeatedly swatted on the fanny by a clown in Puddy the Pup’s “The Big Top”.

A little boy and his dog awaken to the music of a passing circus parade on the street. Those of you who have been following these posts will instantly recognize the first performer in the parade as someone we’ve seen before, now retraced and colored in. It is Slippery Sam, with his face now redesigned and masked in clown makeup, playing the same yowling cat calliope which opened the parade in “Just a Clown”. Assorted other new performers march behind him, including a clown with an electric bulb in his nose, and an elephant who plays two drums fastened on his sides with his tail, and carries two saxophone-blowing monkeys in his “trunk” (shaped like a steamer trunk). The boy hastily washes in the same manner as various tots in films of the crosstown rivals at Fleischer’s – by applying a drop of water apiece to each of his respective cheeks. Then the boy and his dog slide down the staircase banister, causing a posed statue mounted on the railing at the foot of the stairs to leap out of the way, as the boy and dog sail past, exiting the house by puncturing silhouette-shaped holes of themselves through the front door. Arriving at the circus grounds, they listen to the spiel of Barker Bill, who provides verbal descriptions of the various acts inside, while we in the audience receive actual glimpses of the performers. Gigantica, world’s largest ape. A roller-skating jackass, who trips up his skating trainer, then laughs at him like Gandy Goose. Mademoiselle Petite – a hippo redrawing of the same fat lady pig trapeze artist who got repeatedly swatted on the fanny by a clown in Puddy the Pup’s “The Big Top”.

A policeman clown walking on stilts is added to this action, attempting to break up the paddling. But the passing by of Miss Petite blows off all of the cop’s clothes except for a set of bathing trunks worn underneath. Two clowns below carve away at the stilts with axes, while two others carry a bathtub. The cop falls, is caught in the tub, and drives out from the tub water about half a dozen seals, emerging himself from the water riding one (another gag lifted from “The Big Top”). Adolf the Wild Man (who does not happen to bear any resemblance to Hitler, though the choice of names may have been intentional), is a virtual twin to one of the battling behemoths with ships tattooed on their chest appearing in 1935’s “Circus Days”. He attempts to replicate William Tell’s trick, by having an apple shot off his head by cannon. The weapon’s blast misses the apple entirely, but blackens Adolf’s face, and as usual causes the tattooed ship to sink beneath the waves. The final act is the old lion tamer bit, as Colonel Cornelius Crackpot places his head in the lion’s mouth, then opens his own mouth to briefly swallow the lion whole (modification of the sequence from “Just a Clown”). An add-on to the scene has the Colonel take a bow, and lose his toupee on the ground, which the lion points out to his embarrassment. Barker Bill finally calls for the crowd to ante up their “one thin dime” for admission. The boy and dog sneak away from the crowd, and the boy asks his dog whether they should spend their dime on the show. The dog shakes his head no, but when the boy suggests an alternative use of the coin to go to the movies, the pup nods yes. They march off together happily as the film fades out.

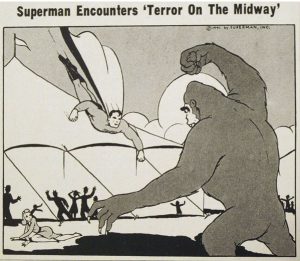

Terror On the Midway (Fleischer/Paramount, Superman, 8/30/42 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Orestes Calpini/Jim Davis, anim.) – The last Fleischer cartoon released by Paramount. Its subject matter seems almost a tame assignment for the man of steel, whom we usually expect to find fighting bigger foes. Yet, based on information provided last week by bloggers of this site regarding a disastrous circus tent fire occurring around the same period, this production may have been inspired by recent headlines, accounting for its creation. Lois and Clark are assigned the menial task of covering the circus opening. One unusual act includes a line of elephants dancing the conga with a clown. But the star attraction is Gigantic, a huge gorilla, kept locked in a cage. A loose monkey in a red circus coat curiously tugs at a metal loop attached to a rope on the the cage, releasing the steel bar that holds the cage door shut. The monstrous ape is freed, and sends the spectators and performers into a panic. Trainers and roustabouts try to cast ropes around Gigantic to bind him, but the ape flips the men on the ends of the ropes almost as if cracking a whip, sending them scattering, and then tosses a whole circus wagon across the arena, stampeding the elephants. One thing leads to another, and soon, every wild animal is loose from their cages. Lois meanwhile finds herself in direct peril, as she darts in front of the ape to prevent his reaching a small girl, placing the child up into the bleachers where she can make an escape, but is then pursued by the gorilla herself. A job for Superman. While attempting to change costumes, Clark dodges gunfire from trainers trying to stop the advance of a loose tiger, then Clark is jumped by a pouncing panther. Now in Superman garb, the man of steel wrestles the panther, depositing him back into a cage. Superman rounds up lions two at a time, then pursues another under the bleachers, when he becomes aware of Lois, being pursued up a tentpole by the climbing ape. Superman flies to a platform on the pole and wrestles with the ape, causing the ladder on which they are standing to break loose from the pole and fall. As they plummet to the ground, an electrical wire is snapped, igniting a fire. Superman continues to deliver mighty punches to the gorilla’s jaw, then seizes a net from the trapeze act to bind the gorilla securely. The fire has spread to Lois’s pole, which begins to topple. Superman darts in to catch Lois before it falls, then uses his cape to smother out the fire. Lois lives to tell the tale, in another scoop of a story.

Terror On the Midway (Fleischer/Paramount, Superman, 8/30/42 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Orestes Calpini/Jim Davis, anim.) – The last Fleischer cartoon released by Paramount. Its subject matter seems almost a tame assignment for the man of steel, whom we usually expect to find fighting bigger foes. Yet, based on information provided last week by bloggers of this site regarding a disastrous circus tent fire occurring around the same period, this production may have been inspired by recent headlines, accounting for its creation. Lois and Clark are assigned the menial task of covering the circus opening. One unusual act includes a line of elephants dancing the conga with a clown. But the star attraction is Gigantic, a huge gorilla, kept locked in a cage. A loose monkey in a red circus coat curiously tugs at a metal loop attached to a rope on the the cage, releasing the steel bar that holds the cage door shut. The monstrous ape is freed, and sends the spectators and performers into a panic. Trainers and roustabouts try to cast ropes around Gigantic to bind him, but the ape flips the men on the ends of the ropes almost as if cracking a whip, sending them scattering, and then tosses a whole circus wagon across the arena, stampeding the elephants. One thing leads to another, and soon, every wild animal is loose from their cages. Lois meanwhile finds herself in direct peril, as she darts in front of the ape to prevent his reaching a small girl, placing the child up into the bleachers where she can make an escape, but is then pursued by the gorilla herself. A job for Superman. While attempting to change costumes, Clark dodges gunfire from trainers trying to stop the advance of a loose tiger, then Clark is jumped by a pouncing panther. Now in Superman garb, the man of steel wrestles the panther, depositing him back into a cage. Superman rounds up lions two at a time, then pursues another under the bleachers, when he becomes aware of Lois, being pursued up a tentpole by the climbing ape. Superman flies to a platform on the pole and wrestles with the ape, causing the ladder on which they are standing to break loose from the pole and fall. As they plummet to the ground, an electrical wire is snapped, igniting a fire. Superman continues to deliver mighty punches to the gorilla’s jaw, then seizes a net from the trapeze act to bind the gorilla securely. The fire has spread to Lois’s pole, which begins to topple. Superman darts in to catch Lois before it falls, then uses his cape to smother out the fire. Lois lives to tell the tale, in another scoop of a story.

The Dizzy Acrobat (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 5/31/43 – Alex Lovy is believed to be director, though no direction credit appears on the original titles). Our scene opens at the usual circus grounds, with a barker touting the sideshow. Saving on animation, several sideshow acts are depicted merely on canvas illustrations. Buelah Bulge, the fat lady. Bernie Burny, the fire eater. And Art Gum, rubber man (with an added wartime sign reading “Gone for the duration”). Enter Woody, carrying a hot dog, and cheerily singing “I Went To the Animal Fair”. Oblivious to goings-on around him, Woody barely misses being slammed by the sledge hammer of a man using the high-striker, and also saunters through and back out the bars of a tiger’s cage, narrowly avoiding a mauling. He pauses to figure out the spelling of the sign on a rhino’s cage, mispronouncing the word as “rhino-ce-herious”. While he does so, a lion in the next cage bites off and swallows a large portion of Woody’s hot dog. Woody doesn’t notice, until he turns around to find the meat gone, and the lion still chewing. Deftly, Woody takes hold of the lion’s tail hanging out through the cage bars, and slips it into the remaining portion of his hot dog bun. He then holds the bun up deliberately high, and the lion takes another chew. The lion screams in pain, whizzing around the cage like a comet, and when he stops, the end of his tail has disappeared. Turning to the audience, and lapsing into a vocal impression of Jerry Colonna, the lion states, “Well, just call me Stubby.”

The Dizzy Acrobat (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 5/31/43 – Alex Lovy is believed to be director, though no direction credit appears on the original titles). Our scene opens at the usual circus grounds, with a barker touting the sideshow. Saving on animation, several sideshow acts are depicted merely on canvas illustrations. Buelah Bulge, the fat lady. Bernie Burny, the fire eater. And Art Gum, rubber man (with an added wartime sign reading “Gone for the duration”). Enter Woody, carrying a hot dog, and cheerily singing “I Went To the Animal Fair”. Oblivious to goings-on around him, Woody barely misses being slammed by the sledge hammer of a man using the high-striker, and also saunters through and back out the bars of a tiger’s cage, narrowly avoiding a mauling. He pauses to figure out the spelling of the sign on a rhino’s cage, mispronouncing the word as “rhino-ce-herious”. While he does so, a lion in the next cage bites off and swallows a large portion of Woody’s hot dog. Woody doesn’t notice, until he turns around to find the meat gone, and the lion still chewing. Deftly, Woody takes hold of the lion’s tail hanging out through the cage bars, and slips it into the remaining portion of his hot dog bun. He then holds the bun up deliberately high, and the lion takes another chew. The lion screams in pain, whizzing around the cage like a comet, and when he stops, the end of his tail has disappeared. Turning to the audience, and lapsing into a vocal impression of Jerry Colonna, the lion states, “Well, just call me Stubby.”

Woody continues on his way, now carrying a triple-scoop ice cream cone. He narrowly escapes doom again, walking right through the path of a knife-throwing act, then marches under the tent flap of the big top to enter without a ticket. A large boot instantly launches Woody through the tent canvas and back outside. The action is repeated, and Woody is booted again, his ice cream cone landing upside down on his head. A third attempt runs him face-to-face into the roustabout with the big boot. The large man states that if Woody wants to see the show, he’s gotta work for it. Returning to the days of Mutt and Jeff, Woody repeats the old gag of watering an elephant by hooking its trunk to a fire hydrant. The angered roustabout blocks Woody from the tent entrance, and rolls up his sleeves. “When I get through with you, any similarity between you and a woodpecker will be purely coincidental.” A chase commences, round and round a circus wagon. Woody exits the colored blurs around the wagon, as the roustabout keeps circling. To trip him up, Woody lifts the wagon tongue into the path of the roustabout’s feet. Then, the chasers enter the arena. Woody holds a cage door open, allowing the roustabout to run right past him, straight into the lion. Woody locks the cage door, but the panicked roustabout somehow manages to whiz right through the bars despite his girth, the friction of his passing through them turning the bars red hot. Without even knowing where he has wound up, the roustabout finds himself at the top of a platform atop a balanced pole, sitting in an easy chair.

Woody continues on his way, now carrying a triple-scoop ice cream cone. He narrowly escapes doom again, walking right through the path of a knife-throwing act, then marches under the tent flap of the big top to enter without a ticket. A large boot instantly launches Woody through the tent canvas and back outside. The action is repeated, and Woody is booted again, his ice cream cone landing upside down on his head. A third attempt runs him face-to-face into the roustabout with the big boot. The large man states that if Woody wants to see the show, he’s gotta work for it. Returning to the days of Mutt and Jeff, Woody repeats the old gag of watering an elephant by hooking its trunk to a fire hydrant. The angered roustabout blocks Woody from the tent entrance, and rolls up his sleeves. “When I get through with you, any similarity between you and a woodpecker will be purely coincidental.” A chase commences, round and round a circus wagon. Woody exits the colored blurs around the wagon, as the roustabout keeps circling. To trip him up, Woody lifts the wagon tongue into the path of the roustabout’s feet. Then, the chasers enter the arena. Woody holds a cage door open, allowing the roustabout to run right past him, straight into the lion. Woody locks the cage door, but the panicked roustabout somehow manages to whiz right through the bars despite his girth, the friction of his passing through them turning the bars red hot. Without even knowing where he has wound up, the roustabout finds himself at the top of a platform atop a balanced pole, sitting in an easy chair.

Hullaba-Lulu (Famous/Paramount, Little Lulu, 2/25/44 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) -Lulu’s second cartoon finds her at the circus. The original animated titles, fortunately preserved, have the letters of the film’s name jump through a circus hoop held by Lulu. The action opens on a scene of disrupted action, as anxious customers wait endlessly in line at the ticket wagon for the show, while Lulu pays for a single ticket, all in pennies. She is about to enter the performance, when the ringmaster appears, tossing a small boy out the side of the tent, and warning him not to try to sneak back in. Lulu asks what is the matter, and the weeping boy responds that he’s never see a circus before, and it looks like he never will. Lulu attempts to dismiss this distressing scene from her thoughts, and proceeds toward the entrance – but an invisible force tugs at the hem of her skirt, and keeps holding her back. Suddenly, a miniature shoulder angel, with Lulu’s face, materializes, and suggests that the right thing to do is to give the poor boy her ticket. Just as suddenly, an equally-small devil-Lulu appears on her other side, telling her not to be a sucker. “You haven’t seen a circus yourself – – this year.” “It’s better to give than to receive”, counters the angel. The devil replies by quoting a catch phrase from the studio’s new character, Blackie the Black Sheep – “Are you kiddin’?” The angel chases the devil round and round Lulu’s head, then removes Lulu’s lollipop from her lips, using it to bat the devil clear out of the picture. “Go”, commands the angel to Lulu. Lulu allows her ticket to drop close to the crying boy, who is overjoyed to discover it, never realizing from where it came. Now, having done her good deed, Lulu reverts to form, devising a scheme to get inside herself without a ticket, by ripping off portions of the advertisement from sandwich-sign boards of a passing man, advertising suit-pressing at a local tailor’s. Lulu tears away the picture of a business suit, and the portion of the sign’s lettering that reads “Press”, and holds them in front of herself to gain free entry at the ticket-taker’s turnstyle.

Hullaba-Lulu (Famous/Paramount, Little Lulu, 2/25/44 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) -Lulu’s second cartoon finds her at the circus. The original animated titles, fortunately preserved, have the letters of the film’s name jump through a circus hoop held by Lulu. The action opens on a scene of disrupted action, as anxious customers wait endlessly in line at the ticket wagon for the show, while Lulu pays for a single ticket, all in pennies. She is about to enter the performance, when the ringmaster appears, tossing a small boy out the side of the tent, and warning him not to try to sneak back in. Lulu asks what is the matter, and the weeping boy responds that he’s never see a circus before, and it looks like he never will. Lulu attempts to dismiss this distressing scene from her thoughts, and proceeds toward the entrance – but an invisible force tugs at the hem of her skirt, and keeps holding her back. Suddenly, a miniature shoulder angel, with Lulu’s face, materializes, and suggests that the right thing to do is to give the poor boy her ticket. Just as suddenly, an equally-small devil-Lulu appears on her other side, telling her not to be a sucker. “You haven’t seen a circus yourself – – this year.” “It’s better to give than to receive”, counters the angel. The devil replies by quoting a catch phrase from the studio’s new character, Blackie the Black Sheep – “Are you kiddin’?” The angel chases the devil round and round Lulu’s head, then removes Lulu’s lollipop from her lips, using it to bat the devil clear out of the picture. “Go”, commands the angel to Lulu. Lulu allows her ticket to drop close to the crying boy, who is overjoyed to discover it, never realizing from where it came. Now, having done her good deed, Lulu reverts to form, devising a scheme to get inside herself without a ticket, by ripping off portions of the advertisement from sandwich-sign boards of a passing man, advertising suit-pressing at a local tailor’s. Lulu tears away the picture of a business suit, and the portion of the sign’s lettering that reads “Press”, and holds them in front of herself to gain free entry at the ticket-taker’s turnstyle.

Lulu attends the sideshow, where she goes about the process of debunking the acts of the various performers and freaks. Asbesto the fire eater can seemingly swallow the flame off of lit torches – but can’t take a hotfoot. The ringmaster’s own sawing-a-lady-in-half trick appears to leave some unseen connection between the two halves of the box, as the lady’s head laughs hysterically when her feet hanging out of the other half box are tickled. A Rajah who walks across a bed of allegedly razor-sharp spikes can’t bear the sharp edges of Lulu’s peanut shells scattered about the stage. Finally, the ringmaster prepares to engage in a lion taming act against Ferocio, the jungle killer. The real Ferocio is safely secured inside a wagon, while at a tunnel entrance leading to the ringmaster’s cage, two roustabouts don a lion costume. “Fakers”, Lulu whispers to Ferocio, as she pulls the pin to open the wagon’s cage door. The roustabouts are stopped in their tracks when the freed Ferocio steps upon the costume’s tail. One look at the real lion loose, and the roustabouts abandon costume and depart pronto. Now Ferocio enters the tunnel to join the ringmaster. This is just the show Lulu paid – make that didn’t pay – to see, and she stands transfixed outside the cage bars, licking her lollipop in rapid-fire strokes in time with the racing of her heart. The ringmaster suspects something is amiss when the force of Ferocio’s roar within the tunnel nearly blows the ringmaster backwards. The lion enters, and an effort to drive him back with a chair results in the chair being reduced to splinters by one swipe of a mighty paw. Dropping the chair’s remains, the ringmaster turns to whip and pistol. Each seems to have little effect, and the gun is soon emptied of shells. Terrified, the ringmaster leaps as high as he can, clinging to the bars of the cage. The lion rears back, then pounces into the air, as the ringmaster braces himself for his doom. But there is a long pause, during which the lion’s roaring is silenced, and the ringmaster remains in one piece. Cautiously, he opens his eyes for a look, and sees the amazing sight of Lulu, now within the cage, totally pacifying the lion by stroking her lollipop up and down across the beast’s huge tongue. The lion becomes Mesmerized by the flavor, and ends the film with a happy smile, his eyes dancing cartwheels in independent orbit from one another (a Jim Tyer effect?), for the iris out.

Lulu attends the sideshow, where she goes about the process of debunking the acts of the various performers and freaks. Asbesto the fire eater can seemingly swallow the flame off of lit torches – but can’t take a hotfoot. The ringmaster’s own sawing-a-lady-in-half trick appears to leave some unseen connection between the two halves of the box, as the lady’s head laughs hysterically when her feet hanging out of the other half box are tickled. A Rajah who walks across a bed of allegedly razor-sharp spikes can’t bear the sharp edges of Lulu’s peanut shells scattered about the stage. Finally, the ringmaster prepares to engage in a lion taming act against Ferocio, the jungle killer. The real Ferocio is safely secured inside a wagon, while at a tunnel entrance leading to the ringmaster’s cage, two roustabouts don a lion costume. “Fakers”, Lulu whispers to Ferocio, as she pulls the pin to open the wagon’s cage door. The roustabouts are stopped in their tracks when the freed Ferocio steps upon the costume’s tail. One look at the real lion loose, and the roustabouts abandon costume and depart pronto. Now Ferocio enters the tunnel to join the ringmaster. This is just the show Lulu paid – make that didn’t pay – to see, and she stands transfixed outside the cage bars, licking her lollipop in rapid-fire strokes in time with the racing of her heart. The ringmaster suspects something is amiss when the force of Ferocio’s roar within the tunnel nearly blows the ringmaster backwards. The lion enters, and an effort to drive him back with a chair results in the chair being reduced to splinters by one swipe of a mighty paw. Dropping the chair’s remains, the ringmaster turns to whip and pistol. Each seems to have little effect, and the gun is soon emptied of shells. Terrified, the ringmaster leaps as high as he can, clinging to the bars of the cage. The lion rears back, then pounces into the air, as the ringmaster braces himself for his doom. But there is a long pause, during which the lion’s roaring is silenced, and the ringmaster remains in one piece. Cautiously, he opens his eyes for a look, and sees the amazing sight of Lulu, now within the cage, totally pacifying the lion by stroking her lollipop up and down across the beast’s huge tongue. The lion becomes Mesmerized by the flavor, and ends the film with a happy smile, his eyes dancing cartwheels in independent orbit from one another (a Jim Tyer effect?), for the iris out.

Into the later 40’s, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

I can identify the “unknown product” with the rabbit on the label in “Goofy Groceries”. It’s Brer Rabbit Molasses, a brand that has been around for over a hundred years. Molasses was a popular sweetener during the war because, unlike sugar, it was never rationed.

While “Dumbo” lacks any elaborate multiplane camera effects, it doesn’t strike me as cheaply made or rushed into production in the same sense as, say, “The Sword in the Stone” does. It’s one of Disney’s finest, most perfect films, and I don’t blame Walt for being proud of it. Since Dumbo’s real name was “Jumbo Jr.,” and the historic Jumbo was an African elephant with correspondingly large ears, then it’s possible that Dumbo inherited that feature patrilineally. (In real life, African and Asiatic elephants are not interfertile.)

The giant apes in “Happy Circus Days” and “Terror on the Midway” appear to have been inspired by Gargantua, a star attraction of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in the 1940s, billed as “the largest gorilla ever exhibited.” Gargantua had a badly scarred face from acid burns inflicted on him in his youth, giving him a very fearsome appearance, and circus publicity made much of his aggressive and violent nature. After his death an autopsy found several impacted and rotten wisdom teeth, which may account for his bad disposition.