As the ‘30’s wore on, and the country began to climb out of the great depression, there seems to have been no visible letup in popularity of circuses with the masses, although alternative forms of entertainment were becoming more generally affordable to John Q. Public. In film, they remained a recurring theme of storylines. Spanky MacFarland would encounter the subject at least three in the last half of the decade, attempting to dodge school to see the show in Our Gang’s “Spooky Hooky’ (1937), and actually getting to the show in the feature “Peck’s Bad Boy With the Circus” (1939) with Hal Roach veterans Edgar Kennedy and Billy Gilbert. Spanky would himself become ringmaster, producing his own show and joined by Alfalfa on the flying trapeze, in the Gang short “Clown Princes’ (1939). The Marx Brothers would rampage through the big top in “The Marx Brothers At the Circus” (1939), giving Groucho one of his most memorable song numbers, “Lydia, the Tattooed Lady”. The atmosphere of popcorn, peanuts, and balloons would thus retain its magnetic appeal, even as the people became more generally urban, and threats of a looming war with foreign lands mobilized the public into growing settings of mass production and mechanization.

The Lyin’ Mouse (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 10/16/37 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – This could perhaps be called an example of Freleng at his most basic. Nothing elaborate, pretentious, or even significantly thought out. Just a simple old tale, told rather straight, with a slight sarcastic twist typical of Warner product. A mouse caught by his tail in a mousetrap tries to convince the cat who caught him that he can do a good turn for the cat someday, by telling him the old fable of the lion and the mouse. There are comparatively few true gags for a Warner product. The mouse, in relating the story, speeds his voice up to pipsqueak tones when describing the mouse in the fable, then slows his voice down to resonant Billy Bletcher tones when referring to the lion. The lion makes an entrance that predicts many a Freleng cartoon to come, uttering a series of boasts one would more expect out of the lips of the yet-to-be-created Yosemite Sam: “I’m the rip-snortinest, Edward Everett Hortonest, Charles Laughtonest, and ya’ ain’t seen naw-thonest, lion in the whole world.” He gives out with a roar, the force of which rolls up the savannah turf like a carpet. He continues with a series of roars that frightens the jungle animals away, including a cameo by the baby ostrich who previously appeared in “Plenty of Money and You”, who buries his head in the sand, then pulls the hole out of the ground around his neck to run away. The mouse in the story tries to copy the roar by blowing through an old party horn, scaring two turtles into the same shell. After the usual “do a good turn for you” encounter between mouse and lion, the lion falls for a series if booby traps left by the Frank Cluck Expedition. He gingerly extricates a roast chicken out of a bear trap, only to have a mousetrap snapped upon him when he bites into the bird. A tempting live lamb with a rope attached to its collar (who gives its own sales pitch upon the desirability of lamb through a series of advertising signs) is the trigger for a jack-on-the-box spring with a boxing glove attached, which knocks the lion cold. The lion is captured and brought to the circus, where he again performs the standard cliche act of having trainer put head in the lion’s mouth, followed by lion putting head in the trainer’s mouth. At night, the lion weeps, locked in his cage, until the mouse appears out of nowhere. (How did he get to the circus? Is the big show playing a jungle circuit?) The mouse begins gnawing at the cage wall like a buzz-saw, stopping briefly to spit out a nail, and carves out an exit in the perfect silhouette for the lion to walk through. The film ends with the real mouse being released from the trap by the cat, and being handed the cheese bait. The mouse walks over to a position where he is mere inches from his hole, then turns to the cat to jeer him wuth “SUCKER!”, darting nto the hole. “Can ya’ imagine that?”, closes the cat.

The Lyin’ Mouse (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 10/16/37 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – This could perhaps be called an example of Freleng at his most basic. Nothing elaborate, pretentious, or even significantly thought out. Just a simple old tale, told rather straight, with a slight sarcastic twist typical of Warner product. A mouse caught by his tail in a mousetrap tries to convince the cat who caught him that he can do a good turn for the cat someday, by telling him the old fable of the lion and the mouse. There are comparatively few true gags for a Warner product. The mouse, in relating the story, speeds his voice up to pipsqueak tones when describing the mouse in the fable, then slows his voice down to resonant Billy Bletcher tones when referring to the lion. The lion makes an entrance that predicts many a Freleng cartoon to come, uttering a series of boasts one would more expect out of the lips of the yet-to-be-created Yosemite Sam: “I’m the rip-snortinest, Edward Everett Hortonest, Charles Laughtonest, and ya’ ain’t seen naw-thonest, lion in the whole world.” He gives out with a roar, the force of which rolls up the savannah turf like a carpet. He continues with a series of roars that frightens the jungle animals away, including a cameo by the baby ostrich who previously appeared in “Plenty of Money and You”, who buries his head in the sand, then pulls the hole out of the ground around his neck to run away. The mouse in the story tries to copy the roar by blowing through an old party horn, scaring two turtles into the same shell. After the usual “do a good turn for you” encounter between mouse and lion, the lion falls for a series if booby traps left by the Frank Cluck Expedition. He gingerly extricates a roast chicken out of a bear trap, only to have a mousetrap snapped upon him when he bites into the bird. A tempting live lamb with a rope attached to its collar (who gives its own sales pitch upon the desirability of lamb through a series of advertising signs) is the trigger for a jack-on-the-box spring with a boxing glove attached, which knocks the lion cold. The lion is captured and brought to the circus, where he again performs the standard cliche act of having trainer put head in the lion’s mouth, followed by lion putting head in the trainer’s mouth. At night, the lion weeps, locked in his cage, until the mouse appears out of nowhere. (How did he get to the circus? Is the big show playing a jungle circuit?) The mouse begins gnawing at the cage wall like a buzz-saw, stopping briefly to spit out a nail, and carves out an exit in the perfect silhouette for the lion to walk through. The film ends with the real mouse being released from the trap by the cat, and being handed the cheese bait. The mouse walks over to a position where he is mere inches from his hole, then turns to the cat to jeer him wuth “SUCKER!”, darting nto the hole. “Can ya’ imagine that?”, closes the cat.

The Big Top (Terrytoons/Educational, Puddy the Pup, 5/12/38 – Mannie Davis, dir.) – Typical establishing shots show the crowds thronging to the big tent, and a variety of acts both above and at ground level in progress inside. A strange opening act has a fat lady swinging on trapeze, for the sole purpose of having a clown standing on the opposite platform whack her across the butt with a paddle on each swing. (Source of this footage is from a complete Castle Films print – I wonder if CBS would have chosen to censor this rude behavior?) Outside, Puddy arrives at the circus grounds, but observes a signpost reading “No dogs allowed”. Thinking disdainfully of such discrimination, Puddy kicks up some mud, covering the sign’s lettering with it, then looks for a way in. He begins digging a deep hole with intent to tunnel under the tent flaps, until he observes a large pair of impatiently tapping shoes next to the hole, insude of which stand a pair of considerably flat feet. It is an angry circus cop. With a nervous grin, Puddy pushes two mounds of earth back into the hole to fill it up, then dodges a swing of the cop’s billy club. Puddy ducks under the wheels of a circus wagon, where he spots a new idea to gain entry. A march of elephants is entering the tent, clinging trunk to tail. Taking his cue from their cadence, Pudgy runs behind the last elephant in line, nipping lightly upon the mammoth’s tail to join the grand entry. A latecomer elephant appears behind Puddy, and takes hold of Puddy’s tail with his trunk, pulling him upwards and off his feet, so that Puddy makes his entrance suspended in air between the forward elephant’s tail and the rear elephant’s trunk. Puddy abandons the elephants inside the tent, and attempts to find a space in the bleachers to watch the show.

The Big Top (Terrytoons/Educational, Puddy the Pup, 5/12/38 – Mannie Davis, dir.) – Typical establishing shots show the crowds thronging to the big tent, and a variety of acts both above and at ground level in progress inside. A strange opening act has a fat lady swinging on trapeze, for the sole purpose of having a clown standing on the opposite platform whack her across the butt with a paddle on each swing. (Source of this footage is from a complete Castle Films print – I wonder if CBS would have chosen to censor this rude behavior?) Outside, Puddy arrives at the circus grounds, but observes a signpost reading “No dogs allowed”. Thinking disdainfully of such discrimination, Puddy kicks up some mud, covering the sign’s lettering with it, then looks for a way in. He begins digging a deep hole with intent to tunnel under the tent flaps, until he observes a large pair of impatiently tapping shoes next to the hole, insude of which stand a pair of considerably flat feet. It is an angry circus cop. With a nervous grin, Puddy pushes two mounds of earth back into the hole to fill it up, then dodges a swing of the cop’s billy club. Puddy ducks under the wheels of a circus wagon, where he spots a new idea to gain entry. A march of elephants is entering the tent, clinging trunk to tail. Taking his cue from their cadence, Pudgy runs behind the last elephant in line, nipping lightly upon the mammoth’s tail to join the grand entry. A latecomer elephant appears behind Puddy, and takes hold of Puddy’s tail with his trunk, pulling him upwards and off his feet, so that Puddy makes his entrance suspended in air between the forward elephant’s tail and the rear elephant’s trunk. Puddy abandons the elephants inside the tent, and attempts to find a space in the bleachers to watch the show.

However, the audience is well packed-in, and one of the spectators doesn’t take well to Puddy attempting to peek out between his feet. Puddy needs a secret weapon – and finds it in the form of a caged animal that no self-respecting circus menagerie would include, except for this one – a skunk. Puddy releases the walking stench bomb from his cage, and a section of bleachers is soon cleared of seat-warmers, allowing Puddy all the room he needs to enjoy the performance. The cop patrols by, and notices the skunk cage empty. He smells a rat instead of a skunk, as he spots Puddy’s tail in the bleachers. A chase ensues, as the cop and Puddy climb to a high-wire platform above, where a pig on a unicycle and carrying an umbrella is performing. Puddy leaps upon the pig’s umbrella, spinning it in circles as he runs like a revolving turntable. The pig is thrown off balance, the wheel of his unicycle crashing into the cop, and spinning him round and round atop the tight wire, then, knocking him off the wire entirely. The cop falls into a seal tank far below, and emerges riding one of the critters, who crashes him into a tent pole, knocking the cop cold. Puddy, now down from the platform and happy to see his adversary out of the picture, returns to his seat. The next act is a trained dog act, featuring a male and female set of French poodles. The female is named Mademoiselle Fifi, and the sight of her sets Puddy’s eyes spinning and his heart palpitating. The two poodles engage in a traditional Apache dance, with the female getting violently thrown around, but seeming to love it. Chivalry rises in Piddy, who can’t stand to see a woman abused. Growling fiercely, Puddy leaps into the center ring, engaging in battle with the male poodle. When the dust clears, the poodle is knocked cold, and Puddy, frazzled and panting, stands his ground. A ringmaster enters the scene, holding up Puddy’s paw in the air. “The winner”, he declares to the crowd. The final scene dissolves to a new day’s performance, displaying a poster fresh off the presses, advertising Puddy and Fifi as the new sensational act of the circus, for the iris out.

However, the audience is well packed-in, and one of the spectators doesn’t take well to Puddy attempting to peek out between his feet. Puddy needs a secret weapon – and finds it in the form of a caged animal that no self-respecting circus menagerie would include, except for this one – a skunk. Puddy releases the walking stench bomb from his cage, and a section of bleachers is soon cleared of seat-warmers, allowing Puddy all the room he needs to enjoy the performance. The cop patrols by, and notices the skunk cage empty. He smells a rat instead of a skunk, as he spots Puddy’s tail in the bleachers. A chase ensues, as the cop and Puddy climb to a high-wire platform above, where a pig on a unicycle and carrying an umbrella is performing. Puddy leaps upon the pig’s umbrella, spinning it in circles as he runs like a revolving turntable. The pig is thrown off balance, the wheel of his unicycle crashing into the cop, and spinning him round and round atop the tight wire, then, knocking him off the wire entirely. The cop falls into a seal tank far below, and emerges riding one of the critters, who crashes him into a tent pole, knocking the cop cold. Puddy, now down from the platform and happy to see his adversary out of the picture, returns to his seat. The next act is a trained dog act, featuring a male and female set of French poodles. The female is named Mademoiselle Fifi, and the sight of her sets Puddy’s eyes spinning and his heart palpitating. The two poodles engage in a traditional Apache dance, with the female getting violently thrown around, but seeming to love it. Chivalry rises in Piddy, who can’t stand to see a woman abused. Growling fiercely, Puddy leaps into the center ring, engaging in battle with the male poodle. When the dust clears, the poodle is knocked cold, and Puddy, frazzled and panting, stands his ground. A ringmaster enters the scene, holding up Puddy’s paw in the air. “The winner”, he declares to the crowd. The final scene dissolves to a new day’s performance, displaying a poster fresh off the presses, advertising Puddy and Fifi as the new sensational act of the circus, for the iris out.

Brief honorable mention goes to A Day at the Zoo (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 3/11/39 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.). This spot-gag film shouldn’t even be on our radar for this trail, yet becomes the unexpected receptacle for a stray joke completely off its own stated subject matter. The narrator introduces a fellow dressed in a circus outfit, stooped over as if his head is engrossed and buried in reading a newspaper. It is J. Wellington Buttonhook, former lion tamer with the circus, who used to thrill thousands by putting his head in the lion’s mouth. Buttonhook lowers his newspaper and stands to walk away, revealing that the famous head is no more, the area above his uniform’s collar entirely empty of any neck or cranium. Despite an abundance of animals in this film to loosely relate this gag to, it seems out of place when juxtaposed against a running gag of Egghead teasing a lion and eventually getting eaten for it. The gag could have been saved for more fitting inclusion in two other Avery spot-gag films to be produced within the forthcoming year and one-half – “Believe It Or Else” (1939), or “Circus Today” (1940), discussed below.

Brief honorable mention goes to A Day at the Zoo (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 3/11/39 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.). This spot-gag film shouldn’t even be on our radar for this trail, yet becomes the unexpected receptacle for a stray joke completely off its own stated subject matter. The narrator introduces a fellow dressed in a circus outfit, stooped over as if his head is engrossed and buried in reading a newspaper. It is J. Wellington Buttonhook, former lion tamer with the circus, who used to thrill thousands by putting his head in the lion’s mouth. Buttonhook lowers his newspaper and stands to walk away, revealing that the famous head is no more, the area above his uniform’s collar entirely empty of any neck or cranium. Despite an abundance of animals in this film to loosely relate this gag to, it seems out of place when juxtaposed against a running gag of Egghead teasing a lion and eventually getting eaten for it. The gag could have been saved for more fitting inclusion in two other Avery spot-gag films to be produced within the forthcoming year and one-half – “Believe It Or Else” (1939), or “Circus Today” (1940), discussed below.

Animal Cracker Circus (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Color Rhapsody, 9/23/38 – Ben Harrison, dir.) – Nabisco did not invent the animal cracker – but they certainly rendered the product an institution, with their circus-themed packaging of “Barnum’s Animals”, designed to resemble a double-tiered circus wagon of cages enclosing many exotic animals. (Recent packaging redesigns have striven for political correctness, attempting to remove the imprisoned look by removing cage bars and hinting at depiction of the creatures in their wildlife settings.) The popularity of the product was a part of pop culture in the 1930’s, and well beyond. Imagery suggesting the product appears as early as Van Beuren’s first Cinecolor short, Ted Eshbaugh’s “Pastry Town Wedding”, where a rotary press cuts animal shapes out of a long moving strip of dough. Shirley Temple would introduce a hit song in her feature “Curly Top” (1935) – “Animal Crackers In My Soup”. The song provides the nucleus for the underscore of Columbia’s 1938 cartoon here reviewed, and is sung in part at its very opening by its central child protagonist, a recurring young toddler boy, who in recent syndications has been referred to as Sparky, but in ths episode is referred to by his mother as Johnny.

Animal Cracker Circus (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Color Rhapsody, 9/23/38 – Ben Harrison, dir.) – Nabisco did not invent the animal cracker – but they certainly rendered the product an institution, with their circus-themed packaging of “Barnum’s Animals”, designed to resemble a double-tiered circus wagon of cages enclosing many exotic animals. (Recent packaging redesigns have striven for political correctness, attempting to remove the imprisoned look by removing cage bars and hinting at depiction of the creatures in their wildlife settings.) The popularity of the product was a part of pop culture in the 1930’s, and well beyond. Imagery suggesting the product appears as early as Van Beuren’s first Cinecolor short, Ted Eshbaugh’s “Pastry Town Wedding”, where a rotary press cuts animal shapes out of a long moving strip of dough. Shirley Temple would introduce a hit song in her feature “Curly Top” (1935) – “Animal Crackers In My Soup”. The song provides the nucleus for the underscore of Columbia’s 1938 cartoon here reviewed, and is sung in part at its very opening by its central child protagonist, a recurring young toddler boy, who in recent syndications has been referred to as Sparky, but in ths episode is referred to by his mother as Johnny.

The film itself is a well-animated but unfortunately uninspired attempt to mimic the style of Disney’s classic of several seasons earlier, “The Cookie Carnival” (1935). Oddly, this same Disney epic had already been the inspiration in spirit for Mintz’s first 3-strip Technicolor cartoon, “Bon Bon Parade”, merely changing character designs from cookies to candies. Such earlier Mintz effort was far more creative in design and execution than its 1938 counterpart discussed here, and included a color palette using every hue of cel paint imaginable, and an engaging original music score. “Animal Cracker Circus” includes neither of the latter benefits. Once the Shirley Temple melody is established, it is merely repeated in a range of tempos and variations. The film’s color scheme is also rather standard, in fact limited in large part by the dough-like color that predominates most of its baked characters. Sparky (or Johnny) adds little to the film’s charm, being merely a spectator in a high-chair who eats his spinach (without packing Popeye muscles) only after a ringmaster cookie promises to put on a full show for him if he eats it all like a good boy. There are further nearly no gags, nor unique feats of derring-do, to liven up the various circus acts portrayed, all of which are rather expected and routine. The studio instead seems content with letting this film stand or fall solely upon the strength of the flat-cookie designs of its characters, thinking that the tiny tots will be entertained merely at the sight of seeing animal crackers moving. It only works for a few minutes on Sparky/Johnny, who ultimately falls asleep in his chair in the middle of the performance, and has to be carried to bed. Was it all a dream? The only indication no is a lion cookie who tags along behind Sparky’s dog, and settles down to sleep under Sparky’s bed. By the end of the film, we feel a bit like falling asleep ourselves. A lot of pretty pictures, but very little more to really be said about them.

The film itself is a well-animated but unfortunately uninspired attempt to mimic the style of Disney’s classic of several seasons earlier, “The Cookie Carnival” (1935). Oddly, this same Disney epic had already been the inspiration in spirit for Mintz’s first 3-strip Technicolor cartoon, “Bon Bon Parade”, merely changing character designs from cookies to candies. Such earlier Mintz effort was far more creative in design and execution than its 1938 counterpart discussed here, and included a color palette using every hue of cel paint imaginable, and an engaging original music score. “Animal Cracker Circus” includes neither of the latter benefits. Once the Shirley Temple melody is established, it is merely repeated in a range of tempos and variations. The film’s color scheme is also rather standard, in fact limited in large part by the dough-like color that predominates most of its baked characters. Sparky (or Johnny) adds little to the film’s charm, being merely a spectator in a high-chair who eats his spinach (without packing Popeye muscles) only after a ringmaster cookie promises to put on a full show for him if he eats it all like a good boy. There are further nearly no gags, nor unique feats of derring-do, to liven up the various circus acts portrayed, all of which are rather expected and routine. The studio instead seems content with letting this film stand or fall solely upon the strength of the flat-cookie designs of its characters, thinking that the tiny tots will be entertained merely at the sight of seeing animal crackers moving. It only works for a few minutes on Sparky/Johnny, who ultimately falls asleep in his chair in the middle of the performance, and has to be carried to bed. Was it all a dream? The only indication no is a lion cookie who tags along behind Sparky’s dog, and settles down to sleep under Sparky’s bed. By the end of the film, we feel a bit like falling asleep ourselves. A lot of pretty pictures, but very little more to really be said about them.

Merbabies (Disney/RKO, 12/9/38 – Rudolf Ising/George Stallings, dir.) – In the press of Walt’s move into feature production, it became increasingly difficult to meet production quotas with the sort of superior, innovative animation that had been the trademark of the Silly Symphonies (possibly the principal reason behind the series’ forthcoming shutdown in the following season). To meet his contractual commitments, Disney was forced to farm out this episode to his crosstown rivals at MGM, obtaining Rudolf Ising’s services for hire. This of course was nothing new for Ising, who had previously freelanced work for Van Beuren on several Cubby Bear cartoons, though this would be the first time that a for-hire job would be produced in Technicolor and on such an exorbitant budget. But then, Ising and Harman seemed to have written the book on breaking the budget, with their ten-minute-long extravaganzas for the Happy Harmonies series. No one in Hollywood would have seemed capable of filling the Disney shoes without detection or missing a beat except Ising or Harman, who had by this time raised the quality of their product to the same level of visual perfection as Disney’s, if not always the same perfection of storytelling. But that would be no problem here, as it is believed the storyboards for the work developed from within Disney’s own walls, as an intended follow-up to Disney’s own “Water Babies” from 1935. With film concept already in hand, Ising couldn’t very well miss, and it is doubtful than anyone except those few insiders in the know could have told that this splendid production was not simply another eye-popping masterpiece from the Mouse House.

Merbabies (Disney/RKO, 12/9/38 – Rudolf Ising/George Stallings, dir.) – In the press of Walt’s move into feature production, it became increasingly difficult to meet production quotas with the sort of superior, innovative animation that had been the trademark of the Silly Symphonies (possibly the principal reason behind the series’ forthcoming shutdown in the following season). To meet his contractual commitments, Disney was forced to farm out this episode to his crosstown rivals at MGM, obtaining Rudolf Ising’s services for hire. This of course was nothing new for Ising, who had previously freelanced work for Van Beuren on several Cubby Bear cartoons, though this would be the first time that a for-hire job would be produced in Technicolor and on such an exorbitant budget. But then, Ising and Harman seemed to have written the book on breaking the budget, with their ten-minute-long extravaganzas for the Happy Harmonies series. No one in Hollywood would have seemed capable of filling the Disney shoes without detection or missing a beat except Ising or Harman, who had by this time raised the quality of their product to the same level of visual perfection as Disney’s, if not always the same perfection of storytelling. But that would be no problem here, as it is believed the storyboards for the work developed from within Disney’s own walls, as an intended follow-up to Disney’s own “Water Babies” from 1935. With film concept already in hand, Ising couldn’t very well miss, and it is doubtful than anyone except those few insiders in the know could have told that this splendid production was not simply another eye-popping masterpiece from the Mouse House.

I have never heard of any critique by Walt himself upon this film. Perhaps he was too embroiled with his own work to pay much attention to it, and looked the other way. However, even on a day when Walt was in one of his frequent sternly-critical moods, it might be difficult to imagine what Walt could possibly find fault with here. Animation timing and checking, inking and paint work are meticulous, and I have never detected any visual flaws to the product. Character animation is rich, expressive, and fluid in execution. Sound work (was recording conducted at Disney or at the Ising studio?) is of the highest fidelity and richly orchestrated. Whatever the budget may have been, every dollar shows on the screen, and Ising did not disappoint. The only possible point I could envision Walt picking on was that the whale was not realistic enough for his tastes. True, he is not that dissimilar to designs used by Walt himself in Mickey Mouse’s “The Whalers” in the same season, nor much inferior to the more rubbery Walt design used for Willie the Whale in the later “Make Mine Music”. But no doubt Walt was already conceiving images for his own Monstro the Whale for his production of Pinocchio, and the sneezing whale bit from this film plays like something of a dress rehearsal for that sequence. Could Walt have chosen this project for Ising for a hidden purpose – to see how his leading rival would handle the sequence, then take lessons from it as a means of improving upon the concept for his own production? The inner workings of the planning, clever mind of Walt can never be underestimated, and I frankly wouldn’t put it past him if this was indeed a part of his secret agenda.

I have never heard of any critique by Walt himself upon this film. Perhaps he was too embroiled with his own work to pay much attention to it, and looked the other way. However, even on a day when Walt was in one of his frequent sternly-critical moods, it might be difficult to imagine what Walt could possibly find fault with here. Animation timing and checking, inking and paint work are meticulous, and I have never detected any visual flaws to the product. Character animation is rich, expressive, and fluid in execution. Sound work (was recording conducted at Disney or at the Ising studio?) is of the highest fidelity and richly orchestrated. Whatever the budget may have been, every dollar shows on the screen, and Ising did not disappoint. The only possible point I could envision Walt picking on was that the whale was not realistic enough for his tastes. True, he is not that dissimilar to designs used by Walt himself in Mickey Mouse’s “The Whalers” in the same season, nor much inferior to the more rubbery Walt design used for Willie the Whale in the later “Make Mine Music”. But no doubt Walt was already conceiving images for his own Monstro the Whale for his production of Pinocchio, and the sneezing whale bit from this film plays like something of a dress rehearsal for that sequence. Could Walt have chosen this project for Ising for a hidden purpose – to see how his leading rival would handle the sequence, then take lessons from it as a means of improving upon the concept for his own production? The inner workings of the planning, clever mind of Walt can never be underestimated, and I frankly wouldn’t put it past him if this was indeed a part of his secret agenda.

As for the film’s actual plot content, what starts out like a prequel to “The Little Mermaid”, with miniature sea-children materializing out of sea foam, becomes a unique twist upon portrayal of circus life, as the greatest show on earth puts on a performance in a new underwater domain. For this to plausibly occur, some species substitution is obvously necessary. A circus bandwagon is pulled by a team of sea horses, and constructed from what is probably a large conch shell, with instruments comprised of coral and other shell artifacts. The sides of a puffer fish serve as a bass drum. Huge octopi march as elephants, with forward tentacle serving as trunk, and rear tentacle as tail. Crustaceans ride in cages as apes, and a tiger-striped fish roars fiercely from another cage. A curving serpent gives the impression of the humps of a walking camel. Clowns are portrayed by – what else – clown fish, while starfish also become comic circus stars. Inside the arena, sharks perform as lions, even allowing a merbaby to swim inside the shark’s open mouth. (There’s a feat Steven Spielberg couldn’t work into his “Jaws” series.) Eels form the hoops for sea horses to jump through. And a quartet of sea snails takes the place of seals, balancing air bubbles on their noses, and playing melodies through shells of various sizes that serve as tuned horns. The film climaxes as the merbabies dance an elaborate water ballet/bubble dance, adorning themselves with the air bubbles generated from the blowhole of a sleeping, submerged whale. The smallest of the sea snails, anxious to obtain a bubble to balance, stands in front of the nose of the sleeping whale, wagging his tail like an anxious puppy directly below the whale’s sinuses. The whale is awakened, and finds he cannot hold back a sneeze. The babies and snail hang on for dear life as the whale’s inhaling nearly sucks them inside, then they are struck full force with the strength of the whale’s blowing nose. The sneeze empties the arena, sailing the merbabies on a winding trail of bubbles up to the surface. As each bubble rises to sea level, it pops – and so does the baby clinging to it, returning to the form of sea foam again (just as in the original Hans Christian Andersen tale). The film closes on a placid view of the night sea, the merbabies gone. Perhaps we will have o wait for the next high tide, when hopefully, the foamy sea waves will deposit another bumper crop of the adorable beings upon the rocks once more.

As for the film’s actual plot content, what starts out like a prequel to “The Little Mermaid”, with miniature sea-children materializing out of sea foam, becomes a unique twist upon portrayal of circus life, as the greatest show on earth puts on a performance in a new underwater domain. For this to plausibly occur, some species substitution is obvously necessary. A circus bandwagon is pulled by a team of sea horses, and constructed from what is probably a large conch shell, with instruments comprised of coral and other shell artifacts. The sides of a puffer fish serve as a bass drum. Huge octopi march as elephants, with forward tentacle serving as trunk, and rear tentacle as tail. Crustaceans ride in cages as apes, and a tiger-striped fish roars fiercely from another cage. A curving serpent gives the impression of the humps of a walking camel. Clowns are portrayed by – what else – clown fish, while starfish also become comic circus stars. Inside the arena, sharks perform as lions, even allowing a merbaby to swim inside the shark’s open mouth. (There’s a feat Steven Spielberg couldn’t work into his “Jaws” series.) Eels form the hoops for sea horses to jump through. And a quartet of sea snails takes the place of seals, balancing air bubbles on their noses, and playing melodies through shells of various sizes that serve as tuned horns. The film climaxes as the merbabies dance an elaborate water ballet/bubble dance, adorning themselves with the air bubbles generated from the blowhole of a sleeping, submerged whale. The smallest of the sea snails, anxious to obtain a bubble to balance, stands in front of the nose of the sleeping whale, wagging his tail like an anxious puppy directly below the whale’s sinuses. The whale is awakened, and finds he cannot hold back a sneeze. The babies and snail hang on for dear life as the whale’s inhaling nearly sucks them inside, then they are struck full force with the strength of the whale’s blowing nose. The sneeze empties the arena, sailing the merbabies on a winding trail of bubbles up to the surface. As each bubble rises to sea level, it pops – and so does the baby clinging to it, returning to the form of sea foam again (just as in the original Hans Christian Andersen tale). The film closes on a placid view of the night sea, the merbabies gone. Perhaps we will have o wait for the next high tide, when hopefully, the foamy sea waves will deposit another bumper crop of the adorable beings upon the rocks once more.

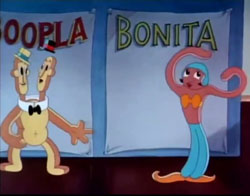

Scrappy’s Side Show (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Scrappy, 3/3/39 – Allen Rose, story (dir?)) – Allen Rose generally does not qualify as one of Charles Mintz’s/Columbia’s most accomplished writers or directors. Yet here, he turns out a competently-conceived juvenile comedy that evokes some of the mood and spirit of “Our Gang” comedies as originally conceived by Hal Roach (the actual “Our Gang” series was at this time falling under the outright ownership of MGM, and would begin to falter in its storylines and sincerity). Scrappy is depicted in a modernized design similar to new models in use by Art Davis’s unit, adding whites to his eyes. more-developed mouth movement, a smaller, more realistic head, and dimensionally-flowing fullness to the pointed patch of hair that always protrudes from his forehead. There is no sign of Oopie, and the role that once might have been Margie’s is now held by a younger, brattier female, who might make a good double for Baby Snooks. The storyline is built on a series of spot gags as Scrappy, with the help of a large troupe of assisting children, acts as barker, ringmaster, and performer in an elaborate makeshift circus for kids, raking place within the fences of a vacant lot. Chalk depictions of various sideshow freaks, with misspelled childish scrawl identifying the names of the performers, appear on the fence surrounding the lot, instantly casting us into the “Our Gang” mood as befit the Gang’s many misspelled signs in their live-action adventures. Scrappy attempts to boast the merits of the show at only a penny admission to those kids of the neighborhood who are not already involved in the performance, but the bratty girl tries to waltz right in the gate before their very eyes without paying, embarrassing Scrappy. Scrappy tells her to go home and get a penny, but the girl, either lacking the coin at home or too lazy/stubborn to go and get it, busts out crying for Mama. She walks back down the sidewalk a few paces, but then approaches the fence, and with her bare hands digs like a dog to create a tunnel under the barrier. She emerges on the other side, but finds her freedom of movement restricted by cage bars which form an enclosure around the area where she is standing. The camera pulls back through the bars to reveal a sign on the otherwise-empty enclosure, reading “Baboon”. Scrappy, not noticing who is inhabiting the cage, leads a tour group past the enclosure, directing their attention to “the funniest freak in captivity. Stand back, folks, it’s very dangerous.” Upon discovering the girl behind the bars, Scrappy reacts with surprise, but then a smile, realizing his description fit the cage’s contents anyway.

Scrappy’s Side Show (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Scrappy, 3/3/39 – Allen Rose, story (dir?)) – Allen Rose generally does not qualify as one of Charles Mintz’s/Columbia’s most accomplished writers or directors. Yet here, he turns out a competently-conceived juvenile comedy that evokes some of the mood and spirit of “Our Gang” comedies as originally conceived by Hal Roach (the actual “Our Gang” series was at this time falling under the outright ownership of MGM, and would begin to falter in its storylines and sincerity). Scrappy is depicted in a modernized design similar to new models in use by Art Davis’s unit, adding whites to his eyes. more-developed mouth movement, a smaller, more realistic head, and dimensionally-flowing fullness to the pointed patch of hair that always protrudes from his forehead. There is no sign of Oopie, and the role that once might have been Margie’s is now held by a younger, brattier female, who might make a good double for Baby Snooks. The storyline is built on a series of spot gags as Scrappy, with the help of a large troupe of assisting children, acts as barker, ringmaster, and performer in an elaborate makeshift circus for kids, raking place within the fences of a vacant lot. Chalk depictions of various sideshow freaks, with misspelled childish scrawl identifying the names of the performers, appear on the fence surrounding the lot, instantly casting us into the “Our Gang” mood as befit the Gang’s many misspelled signs in their live-action adventures. Scrappy attempts to boast the merits of the show at only a penny admission to those kids of the neighborhood who are not already involved in the performance, but the bratty girl tries to waltz right in the gate before their very eyes without paying, embarrassing Scrappy. Scrappy tells her to go home and get a penny, but the girl, either lacking the coin at home or too lazy/stubborn to go and get it, busts out crying for Mama. She walks back down the sidewalk a few paces, but then approaches the fence, and with her bare hands digs like a dog to create a tunnel under the barrier. She emerges on the other side, but finds her freedom of movement restricted by cage bars which form an enclosure around the area where she is standing. The camera pulls back through the bars to reveal a sign on the otherwise-empty enclosure, reading “Baboon”. Scrappy, not noticing who is inhabiting the cage, leads a tour group past the enclosure, directing their attention to “the funniest freak in captivity. Stand back, folks, it’s very dangerous.” Upon discovering the girl behind the bars, Scrappy reacts with surprise, but then a smile, realizing his description fit the cage’s contents anyway.

The girl escapes the enclosure by breaking through the bars, which appear to be only of the wooden variety like a child’s playpen. Scrappy begins introducing freaks from his sideshow. A duck wearng a spring around his neck fills the position of a plate-lipped African Ubangi, Another duck and an old sow, fastened together at the torso by a concealing barrel, serves as an early-day equivalent to a Cat-Dog. The bratty girl starts revealing fake freaks for what they are. She pulls the dress off the “fat lady”, revealing the face to belong to a boy wearing a wig and carrying many pillows upon him to fill out the dress’s girth. Addressing what appears to be a midget, the girl boasts “I’m bigger than you are”, angering the “midget” boy, who stands from a point where his body was concealed in a sitting position within the stage platform, revealing himself to be three times taller than her, with a midget set of clothes tied under his chin to conceal the sight of his own neck and chest. As for the circus giant, he really is a boy shorter than the girl, standing on stilts. A dancing-girl snake charmer is also revealed to be fake when the bratty girl discovers her snake is only a garden hose, and turns the water on full force to douse the charmer. Scrappy stops the performance to throw the little girl out, but she begs for a chance to act in Scrappy’s show. Scrappy offers her a position, telling her to stick her head through a hole. It is if course the hole of an “African Dodger”, and she is pelted with baseballs from the front, while Scrappy paddles her rear end on the other side.

The girl escapes the enclosure by breaking through the bars, which appear to be only of the wooden variety like a child’s playpen. Scrappy begins introducing freaks from his sideshow. A duck wearng a spring around his neck fills the position of a plate-lipped African Ubangi, Another duck and an old sow, fastened together at the torso by a concealing barrel, serves as an early-day equivalent to a Cat-Dog. The bratty girl starts revealing fake freaks for what they are. She pulls the dress off the “fat lady”, revealing the face to belong to a boy wearing a wig and carrying many pillows upon him to fill out the dress’s girth. Addressing what appears to be a midget, the girl boasts “I’m bigger than you are”, angering the “midget” boy, who stands from a point where his body was concealed in a sitting position within the stage platform, revealing himself to be three times taller than her, with a midget set of clothes tied under his chin to conceal the sight of his own neck and chest. As for the circus giant, he really is a boy shorter than the girl, standing on stilts. A dancing-girl snake charmer is also revealed to be fake when the bratty girl discovers her snake is only a garden hose, and turns the water on full force to douse the charmer. Scrappy stops the performance to throw the little girl out, but she begs for a chance to act in Scrappy’s show. Scrappy offers her a position, telling her to stick her head through a hole. It is if course the hole of an “African Dodger”, and she is pelted with baseballs from the front, while Scrappy paddles her rear end on the other side.

Scrappy turns performer, wowing the crowd with a barbell-lifting act as circus strong man. The brat girl returns, stealing his thunder by lifting and twirling the barbell easily, then popping one of its weights as a mere balloon, and dribbling the other like a basketball. She bumps into a team of dog acrobats forming a pyramid, reducing them to a fighting dog pile, then reassembling with her atop the pyramid. The girl rides on a dancing horse, causing its back to sag, revealing two kids providing the legs for the horse inside a costume. Finally, the girl hides in a makeshift cannon built of three barrels piled atop one another in decreasing diameters, and fired by a spring-device resembling a pinball machine plunger. Scrappy enters the same cannon to perform the human cannonball act, and an assistant pulls back and fires the launching plunger. Both Scrappy and the girl are launched clear across their valley home, landing on a board straddling the edges of the community’s highest water tower. Scrappy and the girl look down from their precarious height, and close the cartoon both simultaneously crying for Mama, with an iris out.

Nellie of the Circus (Walter Lantz, Mello-Drama, 5/8/39 – Alex Lovy, dir.) – One of a continuing series of tongue-in-cheek gay-90’s spoofs. Our hero, Dauntless Dan, trudges along a country road, thumbing for a lift. No one will give him a ride – not the rider of a tandem bike, with three vacant seats, but a sign on the rear reading “No Riders”, nor Harpo Marx, riding along in md-air on an imaginary unicycle. Dan has spent many years on a seemingly-endless quest to find his long-lost Nellie, and, with the narrator’s help, spots a prominent billboard advertising the performance of Nell, Queen of the Air, at the local fairgrounds, in a performance of the Ring-Ding-a-Ling Circus. A flashback shows how it all began, with baby Nellie performing swings from the handle of a picnic basket, while baby Dan attempts to provide whistles of appreciation, getting no sound from blowing on his fingers, but producing a foghorn-like note by blowing on his toes. The scene fast-forwards to adolescence, with Dan pushing Nellie on a swing as she performs impossible flips off the edge of the swing seat. Enter by way of a pocket whirlwind Rudolf Ratbone, villain from the big city. Spotting Nellie, he determines to sign her up for the circus. To get Dan out of the way, he hits Dan from behind with a mallet. The mallet develops a throbbing lump instead of Dan’s head. The narrator’s hand enters the frame, providing Ratbone with a bigger mallet. Nellie is spirited away, while Dan is left in a cloud of exhaust from Ratbone’s auto, blackening his face so as to cause him to talk like Rochester, calling after Ratbone with the threat to pull out his razor, with no intention of shaving.

Nellie of the Circus (Walter Lantz, Mello-Drama, 5/8/39 – Alex Lovy, dir.) – One of a continuing series of tongue-in-cheek gay-90’s spoofs. Our hero, Dauntless Dan, trudges along a country road, thumbing for a lift. No one will give him a ride – not the rider of a tandem bike, with three vacant seats, but a sign on the rear reading “No Riders”, nor Harpo Marx, riding along in md-air on an imaginary unicycle. Dan has spent many years on a seemingly-endless quest to find his long-lost Nellie, and, with the narrator’s help, spots a prominent billboard advertising the performance of Nell, Queen of the Air, at the local fairgrounds, in a performance of the Ring-Ding-a-Ling Circus. A flashback shows how it all began, with baby Nellie performing swings from the handle of a picnic basket, while baby Dan attempts to provide whistles of appreciation, getting no sound from blowing on his fingers, but producing a foghorn-like note by blowing on his toes. The scene fast-forwards to adolescence, with Dan pushing Nellie on a swing as she performs impossible flips off the edge of the swing seat. Enter by way of a pocket whirlwind Rudolf Ratbone, villain from the big city. Spotting Nellie, he determines to sign her up for the circus. To get Dan out of the way, he hits Dan from behind with a mallet. The mallet develops a throbbing lump instead of Dan’s head. The narrator’s hand enters the frame, providing Ratbone with a bigger mallet. Nellie is spirited away, while Dan is left in a cloud of exhaust from Ratbone’s auto, blackening his face so as to cause him to talk like Rochester, calling after Ratbone with the threat to pull out his razor, with no intention of shaving.

Dan begins combing every corner of the Earth for Nellie. The pyramids of Egypt, where he interrupts a mummy trying to make a phone call. The bottom of the ocean, where he encounters Jonah in a whale. The jungles of Africa, where he stumbles upon a cannibal tribe with a missionary already in a pot, who invites Dan with “Won’t you join me in a bowl of soup?” The scene returns to present day, as Dan races off toward the big top. Inside, Nellie practices her routine on the trapeze above, while Ratbone cracks a whip from below behind her rear end. Dan appears, causing Ratbone to flee. Dan removes the round weight off a strong man’s barbell, and rolls it like a bowling ball after Ratbone. It connects, breaking Ratbone up into ten little Ratbones, upon which Dan makes another strike with the second weight, causing the little Ratbones to reform into the big one again. Ratbone snaps his whip at Dan, but Dan grabs the end of it, then tugs, flipping Ratbone into the air, and through the roof of the lion’s cage. In a display of pure cowardice, Ratbone is seen cringing in a corner of the cage, screaming for help and for someone to keep the beast from coming near him. Ratbone manages to bend the bars of the cage and slip through, escaping the awful wrath of – a mere harmless lion cub. Ratbone races on foot down the country road into the distance, as Dan bows with arms extended and lips puckered, expecting to catch Nellie in his arms. Nellie leaps gracefully toward Dan, but misses his arms entirely, landing soundly on her bottom. No matter, as she merely grabs Dan into her own embrace, planting a kiss upon him that knocks Dan out cold, for the fade out.

Dan begins combing every corner of the Earth for Nellie. The pyramids of Egypt, where he interrupts a mummy trying to make a phone call. The bottom of the ocean, where he encounters Jonah in a whale. The jungles of Africa, where he stumbles upon a cannibal tribe with a missionary already in a pot, who invites Dan with “Won’t you join me in a bowl of soup?” The scene returns to present day, as Dan races off toward the big top. Inside, Nellie practices her routine on the trapeze above, while Ratbone cracks a whip from below behind her rear end. Dan appears, causing Ratbone to flee. Dan removes the round weight off a strong man’s barbell, and rolls it like a bowling ball after Ratbone. It connects, breaking Ratbone up into ten little Ratbones, upon which Dan makes another strike with the second weight, causing the little Ratbones to reform into the big one again. Ratbone snaps his whip at Dan, but Dan grabs the end of it, then tugs, flipping Ratbone into the air, and through the roof of the lion’s cage. In a display of pure cowardice, Ratbone is seen cringing in a corner of the cage, screaming for help and for someone to keep the beast from coming near him. Ratbone manages to bend the bars of the cage and slip through, escaping the awful wrath of – a mere harmless lion cub. Ratbone races on foot down the country road into the distance, as Dan bows with arms extended and lips puckered, expecting to catch Nellie in his arms. Nellie leaps gracefully toward Dan, but misses his arms entirely, landing soundly on her bottom. No matter, as she merely grabs Dan into her own embrace, planting a kiss upon him that knocks Dan out cold, for the fade out.

Circus Today (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 6/22/40 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – Not Avery on his most creative of days, but a few memorable moments enliven an artistically-presented cartoon featuring some spectacularly-detailed background art, and colorfully-embellished band animation. (The MeTV restoration has been uploaded on Youtube run in reverse. If you have the technology, it’s worth reversing the film again to see just how good the visuals of this film really were intended to look.) The film opens with the shouts and narration of a sideshow barker and a balloon vendor. The vendor appears to be walking around, clinging to an armload of his inflated wares, but the camera pulls back to reveal that the balloons have taken him hundreds of feet aloft, leaving him helplessly walking on air. The barker introduces Gamer the Glutton (a reference to Warner effects animator A.C. Gamer), who eats anything and everything like a goat, then takes a bow, his insides clanking like a walking trash heap. Hotfoot Hogan the Fire Walker is a mystic who walks on red-hot coals – but not without pain, as he yells and shrieks while en route across them. (Watch for an animation error, as Hogan disappears from his chair during the cross-dissolve.) A human cannonball act copies a gag first used in Porky’s “Kristopher Kolumbus, Jr.”, as the performer is blasted clear round the world, returning from the opposite side of the screen with his back plastered with the type of souvenir travel stickers travelers would customarily affix to their steamer trunks to memorialize what countries they had visited. Next, the menagerie. Avery copies from himself, repeating “A Day At the Zoo”’s gag of a customer ignoring the “Do Not Feed the Animals” sign. (He had also used a variant on the same gag in the opening scenes of 1939′ s “Cross-Country Detours”). Instead of being told by the animal to read the sign, a monkey grabs the man by the sleeve, beats him over the head with an umbrella, and calls for the police to arrest the lawbreaker.

Circus Today (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 6/22/40 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – Not Avery on his most creative of days, but a few memorable moments enliven an artistically-presented cartoon featuring some spectacularly-detailed background art, and colorfully-embellished band animation. (The MeTV restoration has been uploaded on Youtube run in reverse. If you have the technology, it’s worth reversing the film again to see just how good the visuals of this film really were intended to look.) The film opens with the shouts and narration of a sideshow barker and a balloon vendor. The vendor appears to be walking around, clinging to an armload of his inflated wares, but the camera pulls back to reveal that the balloons have taken him hundreds of feet aloft, leaving him helplessly walking on air. The barker introduces Gamer the Glutton (a reference to Warner effects animator A.C. Gamer), who eats anything and everything like a goat, then takes a bow, his insides clanking like a walking trash heap. Hotfoot Hogan the Fire Walker is a mystic who walks on red-hot coals – but not without pain, as he yells and shrieks while en route across them. (Watch for an animation error, as Hogan disappears from his chair during the cross-dissolve.) A human cannonball act copies a gag first used in Porky’s “Kristopher Kolumbus, Jr.”, as the performer is blasted clear round the world, returning from the opposite side of the screen with his back plastered with the type of souvenir travel stickers travelers would customarily affix to their steamer trunks to memorialize what countries they had visited. Next, the menagerie. Avery copies from himself, repeating “A Day At the Zoo”’s gag of a customer ignoring the “Do Not Feed the Animals” sign. (He had also used a variant on the same gag in the opening scenes of 1939′ s “Cross-Country Detours”). Instead of being told by the animal to read the sign, a monkey grabs the man by the sleeve, beats him over the head with an umbrella, and calls for the police to arrest the lawbreaker.

A stork receives a nagging phone call, from Eddie Cantor, who is still pressuring him to deliver a boy. A gorilla is introduced as “2,000 pounds of hate and fury”, yet greets the audience with a sissified read of the Mad Russian’s radio catch-phrase, “How do you do?” Inside the big top, a trapeze trio, The Flying Cadenzas, are introduced, who literally fly up to their trapeze posts. Previous reviewers have commented at the inconsistency that they forget how to fly while performing, as one of them fails to catch the other in an acrobatic leap, resulting in a crash, while the unharmed performer asks if there is a doctor in the house. (But then, Warner characters were prone to forget they can fly, such as Daffy Duck in the later “The Million-Hare”.) A female horseback rider attempts to lower herself from the saddle to pick up a handkerchief with her teeth – but only leaves behind her loose dentures – again. Speaking of again, Avery even stoops to the old lion’s head in the trainer’s mouth bit, for the umpteenth time. Prancer, the dancing horse, assumes human position to place his forward legs around his trainer, engaging in fox trot moves to the tune of Avery favorite, “Sweet Georgia Brown”. An elephant act enters the arena, with the trainer the last in the elephant parade, walking on all fours and biting upon the tail of the elephant preceding him. He asks one of the elephants to place its entire weight upon his head. In a repeat of a payoff gag by a bobcat also appearing only a few episodes previously in “Cross-Country Detours”, the elephant stops at the very last minute, and collapses forward on the ground in a crying wail, weeping “I can’t do it. I just can’t do it.” The show climaxes with Count Boris Leapoff’s leap for life – a dive into a tank of water 5,462 feet below. The act is presented from the unusual point of view of the circus bandmaster and his orchestra, with only brief cutaways to the Count as he makes his ascent, then dives off a platform. We do not see the progress of the dive, instead focusing upon the bandmaster, as he conducts his drummer in a dramatic drum roll, while the bandmaster’s eyes follow the progress of the act down, down, down. Suddenly, without visual clue or sound effect, the bandmaster cues the drummer to cease the drum roll, then passes the solo to his trumpeter. “Okay, Joe, take it”, commands the bandmaster in an unusually quiet tone. Joe the trumpeter rises somberly, removes his hat in respect, and begins to play Taps, signaling a tragic end to the afternoon’s performance, and the iris out.

A stork receives a nagging phone call, from Eddie Cantor, who is still pressuring him to deliver a boy. A gorilla is introduced as “2,000 pounds of hate and fury”, yet greets the audience with a sissified read of the Mad Russian’s radio catch-phrase, “How do you do?” Inside the big top, a trapeze trio, The Flying Cadenzas, are introduced, who literally fly up to their trapeze posts. Previous reviewers have commented at the inconsistency that they forget how to fly while performing, as one of them fails to catch the other in an acrobatic leap, resulting in a crash, while the unharmed performer asks if there is a doctor in the house. (But then, Warner characters were prone to forget they can fly, such as Daffy Duck in the later “The Million-Hare”.) A female horseback rider attempts to lower herself from the saddle to pick up a handkerchief with her teeth – but only leaves behind her loose dentures – again. Speaking of again, Avery even stoops to the old lion’s head in the trainer’s mouth bit, for the umpteenth time. Prancer, the dancing horse, assumes human position to place his forward legs around his trainer, engaging in fox trot moves to the tune of Avery favorite, “Sweet Georgia Brown”. An elephant act enters the arena, with the trainer the last in the elephant parade, walking on all fours and biting upon the tail of the elephant preceding him. He asks one of the elephants to place its entire weight upon his head. In a repeat of a payoff gag by a bobcat also appearing only a few episodes previously in “Cross-Country Detours”, the elephant stops at the very last minute, and collapses forward on the ground in a crying wail, weeping “I can’t do it. I just can’t do it.” The show climaxes with Count Boris Leapoff’s leap for life – a dive into a tank of water 5,462 feet below. The act is presented from the unusual point of view of the circus bandmaster and his orchestra, with only brief cutaways to the Count as he makes his ascent, then dives off a platform. We do not see the progress of the dive, instead focusing upon the bandmaster, as he conducts his drummer in a dramatic drum roll, while the bandmaster’s eyes follow the progress of the act down, down, down. Suddenly, without visual clue or sound effect, the bandmaster cues the drummer to cease the drum roll, then passes the solo to his trumpeter. “Okay, Joe, take it”, commands the bandmaster in an unusually quiet tone. Joe the trumpeter rises somberly, removes his hat in respect, and begins to play Taps, signaling a tragic end to the afternoon’s performance, and the iris out.

Next: Into the 1940’s.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Ah, animal crackers. Nabisco started production of Barnum’s Animals in 1902, and I know this because in 1982 they were being sold in special limited-edition 80th anniversary commemorative tins. Since my only complaint about animal crackers was that there were never enough of them in the box, I bought commemorative tins of Barnum’s Animals that year like they were going out of style, which they quickly did. I still have one of the tins, crammed full of little keepsakes from the early part of my life, like my Cub Scout ring and my first shotgun pipe.

I didn’t know that Nabisco had changed the packaging in recent years, but, nostalgic though I am for the circus wagon cracker boxes of my childhood, I can’t exactly say I’m sorry. Even as a little boy, I felt sorry for the poor giraffe that couldn’t stand up straight in its tiny lower-tier cage. I remember the boxes had a little white string on them so you could carry them around like a purse, if you were a girl, or a duffel bag, if you weren’t. The boxes also had little perforations on the bottom to make fully rounded wheels for the circus wagon; however, I remember my brother or my dad using Tinkertoys to build functional axles and wheels that really rolled, so you could pull the circus wagon along by its string! Fun times.

As much as I loved animal crackers, I never once put them in my soup. It sounds disgusting.

At the end of “The Lyin’ Mouse”, the mouse’s lip movements don’t match the word “Sucker!” at all. Could it be a last-minute substitution for something stronger? When I look at it with the sound off, I swear it looks as if he’s saying “Dumbass!”

I don’t know if the scene of the corpulent trapeze artist getting swatted in the rump with a two-by-four was cut from TV prints of “The Big Top”, but that gag would be used again and again in subsequent Terrytoons, as we shall surely see.

“Nellie of the Circus” would be a better cartoon if it had more Nellie in it.

In “Circus Today”, the human cannonball is identified as “Captain Clampett”, just in case anyone’s wondering who’s being caricatured here.

Paul, my understanding is that the string on the animal crackers box was so you could hang it up on your Christmas tree!

What a wonderful idea! But they wouldn’t have lasted long on my Christmas tree!

About Merbabies: if Walt didn’t regret his collaboration with Harman, it wasn’t the other way around. See the Barrier interview.

For live-action films with a circus theme, did you mention the LAUREL AND HARDY short, THE CHIMP (1932) and don’t forget the W.C. Fields’ feature, YOU CAN’T CHEAT AN HONEST MAN (1939).

With all the “Do-Gooders” worrying about “animal rights” (especially regarding elephants) over the last decade or two, do they still have circuses anywhere? When I took my sister-in-law and her kids to a circus some years back, it was totally in-doors. I can’t really remember seeing a circus ouside in tented areas, but I’m sure I must have as a child! When the Cirque Du Soleil was a “big deal” in Chicago (and other parts of the country), my mom got tickets for her and some family members to see it. It was entertaining, but kind of weird – as if it was a circus act that had escaped from Ray Bradbury’s SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES.

Favorite “circus-themed” cartoons of mine (outside of THE MAN ON THE FLYING TRAPEZE – already discussed) are ACROBATTY BUNNY (1946) and … well, I’ll think of ’em later!

Gee, I hate to be a “downer”, but since you asked….

Circuses have been commonly held in indoor venues ever since 1941, when a terrible fire at a circus in Hartford, Connecticut, killed around 200 people, mostly children. They used to use paraffin to waterproof the canvas for the big top, and when it caught fire it spread quickly and rained down on the audience like napalm. Many municipalities passed ordinances banning tent circuses in its aftermath. (It gives me pause today to see the fire scenes in “Dumbo”, released the very same year.)

Australia has some touring circuses with domestic animal acts: dogs, horses, camels, goats, and so on. There might still be one with lions. Some other countries have banned the use of exotic animals in circuses altogether. When I saw the Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1988, they had a big troupe of performing elephants, at least twenty of them. However, some tragic instances of circus elephants killing their trainers and running amok in the early ’90s drew public attention to the deplorable conditions in which they were kept. Even if it were possible for elephants to lead happy and healthy lives as circus performers — and it’s not — it’s simply no longer economically feasible for circuses to maintain them.

Don’t get me started on Cirque du Soleil and the $700 I’ll never get back.

The Clyde Beatty Cole Bros. Circus traversed the hinterlands with a big top-tent show for many years — until perhaps a decade ago.

Anyhow, as a kid, I saw the Beatty/Cole Bros. outfit show in a tent set up in a big field in southern Michigan in the early ‘sixties. I later saw the big Ringling/Barnum show a couple of times in posh indoor venues — including Madison Square Garden — and it was a swell extravaganza… but my memories of the thrills of that Beatty/Cole show in that crowded big top-tent are vivid. They defined ‘circus.’ Sawdust was everywhere.

Leonard, the Ringling show is back (I did a double take when I saw the TV ad). It’s just called “Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey” (no “Circus”). No animals, and in indoor arenas. A few years ago, when the circus came to town for the last time, I went up to where the circus train was parked, and I snapped some nice photos.

Considering how critical Walt Disney was of “To Spring” (“They got colors everywhere and it looks cheap”), he must have sent a couple of staff members to Harman-Ising to check on “Merbabies.”

No actual circus is shown in “Seal Skinners” (MGM, The Captain and the Kids, 28/1/39 — Friz Freleng, dir.), but it figures in the story’s premise. Patty the trained seal has escaped from the Jingling Brothers Circus and headed back to her home in the Arctic. When the circus offers a $100,000 reward for her return, the captain and John Silver the pirate set out separately for the icy north. The climax of the cartoon has some well-animated circus-type acrobatics up in the rigging of the captain’s ship, but no real laughs anywhere. The best thing you can say about “Seal Skinners” is that no seals were actually skinned during the filming of it.