This week, we say adieu to television cartoons (pre-2000) involving circuses, with a few last gasps, including a parting reference to an iconic character that continues to this day. We then move into feature films. We’ve already covered the grand-daddy of them all, Disney’s original Dumbo, so we’ll continue beginning with the 1960’s forward. As these features take a little time to view and then review, I will address them in somewhat random viewing order instead of strictly chronological, depending on my viewing tastes at time of writing, and in order to attempt to pace discussion with something of an even split between the good and the not-so-good.

First, we can’t very well leave a discission of TV circuses without reference to the immortal Krusty the Clown, host of the show-within-a-show commonly spotlighted in The Simpsons. Krusty is an obvious satire of such children’s show hosts as Larry Harmon’s Bozo the Clown. Krusty may have initially been introduced to the series with the primary intent of providing a framework for the screening of the “Itchy and Scratchy” cartoons – a favorite sidelight of the writers allowing broad send-ups of Tom and Jerry, with homicidal and super-violent gag twists. But Krusty took on a life of his own. On camera, he can turn on the hyper-active zaniness required of a kids’ show host. But shallowly beneath the face-painted surface lies a chain-smoking, frequently depressed and insecure character, often prone to mild swearing, who feels over-worked, under-appreciated, and easily frustrated in his goals. He puts up with kids, but only as an occupational hazard of his job. He seems to have strange tastes in picking TV sidekicks, first acquiring Sideshow Bob and then Sideshow Mel, each of whom below the costumes and wigs speak with the diction and intellect of a thespian, yet have to put up with demeaning slapstick pratfalls at Krusty’s hand. And Bob turned out to be a homicidal maniac – leading to a whole sub-genre of episodes that have lasted the run of the series, in which the chronic jailbird annually escapes to concoct wild scenarios and master plots to have vengeance upon Bart Simpson, responsible for his first incarceration.

First, we can’t very well leave a discission of TV circuses without reference to the immortal Krusty the Clown, host of the show-within-a-show commonly spotlighted in The Simpsons. Krusty is an obvious satire of such children’s show hosts as Larry Harmon’s Bozo the Clown. Krusty may have initially been introduced to the series with the primary intent of providing a framework for the screening of the “Itchy and Scratchy” cartoons – a favorite sidelight of the writers allowing broad send-ups of Tom and Jerry, with homicidal and super-violent gag twists. But Krusty took on a life of his own. On camera, he can turn on the hyper-active zaniness required of a kids’ show host. But shallowly beneath the face-painted surface lies a chain-smoking, frequently depressed and insecure character, often prone to mild swearing, who feels over-worked, under-appreciated, and easily frustrated in his goals. He puts up with kids, but only as an occupational hazard of his job. He seems to have strange tastes in picking TV sidekicks, first acquiring Sideshow Bob and then Sideshow Mel, each of whom below the costumes and wigs speak with the diction and intellect of a thespian, yet have to put up with demeaning slapstick pratfalls at Krusty’s hand. And Bob turned out to be a homicidal maniac – leading to a whole sub-genre of episodes that have lasted the run of the series, in which the chronic jailbird annually escapes to concoct wild scenarios and master plots to have vengeance upon Bart Simpson, responsible for his first incarceration.

Episodes of the series involving Krusty are far too numerous to track over thirty-something seasons. So we’ll highlight just a couple as exemplars. Like Father, Like Clown (10/24/91) finds Krusty in usual form for his broadcast – tossing axes at Sideshow Mel, and nearly splitting the latter’s frizzed hairdo. All is laughter and song until the camera switches off, and Krusty reverts to his usual behind-the scenes melancholy – and his reserve pack of nicotine gum. He instructs his personal secretary to cancel all appointments – including a fifth cancellation of a dinner engagement with Bart at the Simpson home, despite Bart’s previous saving Krusty from taking the rap for Sideshow Bob’s misdeeds. At the Simpsons’ home, Bart, who has spruced up in formal attire and splashed on Krusty Kologne (the smell of the Big Top) for the occasion, is devastated by the news of the cancellation, and writes a letter to Krusty, turning in his fan club membership. Krusty’s secretary, upon receiving the letter, corners Krusty to keep his promise, informing him that the boy who never lost faith in him has lost faith in him. The dinner date is rescheduled, and Krusty appears at the door, honking off-key horn and rolling into the living room in a somersault. Krusty pulls out a unicycle, and balances objects on his nose while riding, until Lisa and Bart inform him that he, as their guest, doesn’t have to be “on”, and can relax and be himself. Krusty slumps to relaxed posture, and instructs a monkey in his prop bag to wait in the car.

Episodes of the series involving Krusty are far too numerous to track over thirty-something seasons. So we’ll highlight just a couple as exemplars. Like Father, Like Clown (10/24/91) finds Krusty in usual form for his broadcast – tossing axes at Sideshow Mel, and nearly splitting the latter’s frizzed hairdo. All is laughter and song until the camera switches off, and Krusty reverts to his usual behind-the scenes melancholy – and his reserve pack of nicotine gum. He instructs his personal secretary to cancel all appointments – including a fifth cancellation of a dinner engagement with Bart at the Simpson home, despite Bart’s previous saving Krusty from taking the rap for Sideshow Bob’s misdeeds. At the Simpsons’ home, Bart, who has spruced up in formal attire and splashed on Krusty Kologne (the smell of the Big Top) for the occasion, is devastated by the news of the cancellation, and writes a letter to Krusty, turning in his fan club membership. Krusty’s secretary, upon receiving the letter, corners Krusty to keep his promise, informing him that the boy who never lost faith in him has lost faith in him. The dinner date is rescheduled, and Krusty appears at the door, honking off-key horn and rolling into the living room in a somersault. Krusty pulls out a unicycle, and balances objects on his nose while riding, until Lisa and Bart inform him that he, as their guest, doesn’t have to be “on”, and can relax and be himself. Krusty slumps to relaxed posture, and instructs a monkey in his prop bag to wait in the car.

At the dinner table, Lisa invites Krusty to say grace. Krusty agrees, though stating he’s a little rusty. To everyone’s surprise, Krusty begins reciting a ritualistic prayer in Hebrew! Krusty further states that this brings back memories – and breaks out in a fit of weeping. The Simpsons ask him to talk about what is wrong. Krusty reveals that his real name in Herschel Krustofsky, and that he comes from a long family line of nothing but Rabbis. But the call of clowning ran deep in young Herschel’s blood, and he aspired to a life of comedy. In clever parody of Warner Brothers’ “The Jazz Singer”, his father, Rabbi Krustofsky, rigidly disapproves clowning as beneath the dignity of the family. But Krusty secretly studies and trains, finally getting a break to entertain in a Jewish night-club. As Krusty shapes balloons in the form of the Star of David and a Menorah, he notices his father in the audience, meeting with learned men at one of the tables. Krusty attempts to make an exit, still hidden under his makeup, but someone in the front row squirts him in the face with a seltzer bottle, washing off his false pasty-face. Krusty’s identity is revealed, and his father disowns him, ordering him to leave home.

Back in the present, Krusty becomes so sentimental about his lost family life, that he won’t go home, spending hours poring through every father and son photo in the Simpsons’ family albums. He does not depart until the wee small hours. On the next day’s broadcast, all that Krusty can see in an Itchy and Scratchy cartoon where father-and-son mice murder father-and son cats with a farm thresher, is how much fun the kids were having with their fathers – and bursts out crying on camera. Lisa remarks that when anyone envies the life of the Simpsons’ family, it is obvious they need help. Lisa and Bart thus look up Krusty’s father, who happens to be a fellow religious consultant with Reverend Lovejoy on a public access radio talk show, “Gabbin’ With God”. Bart calls in anonymously, posing a question about reconciling between a father and son. Lovejoy and a monsignor both respond “Yes”, but the Rabbi vents a vehement “No”. The kids now know where Krusty’s dad stands. Bart launches a campaign to meet up with the Rabbi again and again, including costuming as a Rabbi himself, but every attempt to place thought in Krusty’s dad’s head of reconcile meet with stubborn opposition. Attempt to lure Krusty and his dad to the same deli backfires with Dad leaving early and Krusty arriving late. Lisa realizes they’re approaching the problem wrong, and that the one thing Rabbis respect is knowledge. She begins an extensive stint of library research of holy books and ancient Jewish history, stating that she will find something to hit the Rabbi “right in the Judaica.” Bart plays messenger to deliver quote after quote to the Rabbi from learned men of the past promoting reconcile – but the Rabbi has his own counter-quote to match each, with the counter-opinion to hold firm. When all the library books are exhausted (short of Lisa having to learn ancient Hebrew – which she refuses to do), she hands Bart one last quote, that she states is a longshot, but the best she’s got. A moving statement of reconciliatory spirit prompts the Rabbi to ask who of the learned men made ths quote. Bart replies, “Sammy Davis Jr. – an entertainer.” The episode ends in a touching reunion in Krusty’s dressing room, and Krusty bringing his Dad on stage after their 25-year estrangement, where the two sing a duet of “Oh Mein Papa”. The broadcast ends with Dad, in the spirit of things, smacking Krusty in the face with a custard pie.

Back in the present, Krusty becomes so sentimental about his lost family life, that he won’t go home, spending hours poring through every father and son photo in the Simpsons’ family albums. He does not depart until the wee small hours. On the next day’s broadcast, all that Krusty can see in an Itchy and Scratchy cartoon where father-and-son mice murder father-and son cats with a farm thresher, is how much fun the kids were having with their fathers – and bursts out crying on camera. Lisa remarks that when anyone envies the life of the Simpsons’ family, it is obvious they need help. Lisa and Bart thus look up Krusty’s father, who happens to be a fellow religious consultant with Reverend Lovejoy on a public access radio talk show, “Gabbin’ With God”. Bart calls in anonymously, posing a question about reconciling between a father and son. Lovejoy and a monsignor both respond “Yes”, but the Rabbi vents a vehement “No”. The kids now know where Krusty’s dad stands. Bart launches a campaign to meet up with the Rabbi again and again, including costuming as a Rabbi himself, but every attempt to place thought in Krusty’s dad’s head of reconcile meet with stubborn opposition. Attempt to lure Krusty and his dad to the same deli backfires with Dad leaving early and Krusty arriving late. Lisa realizes they’re approaching the problem wrong, and that the one thing Rabbis respect is knowledge. She begins an extensive stint of library research of holy books and ancient Jewish history, stating that she will find something to hit the Rabbi “right in the Judaica.” Bart plays messenger to deliver quote after quote to the Rabbi from learned men of the past promoting reconcile – but the Rabbi has his own counter-quote to match each, with the counter-opinion to hold firm. When all the library books are exhausted (short of Lisa having to learn ancient Hebrew – which she refuses to do), she hands Bart one last quote, that she states is a longshot, but the best she’s got. A moving statement of reconciliatory spirit prompts the Rabbi to ask who of the learned men made ths quote. Bart replies, “Sammy Davis Jr. – an entertainer.” The episode ends in a touching reunion in Krusty’s dressing room, and Krusty bringing his Dad on stage after their 25-year estrangement, where the two sing a duet of “Oh Mein Papa”. The broadcast ends with Dad, in the spirit of things, smacking Krusty in the face with a custard pie.

Krusty Gets Kancelled (5/13/93) – Who is Gabbo? That is what TV spot ads and newspaper headlines scream for weeks, until an announcement comes that he will appear on TV. The long-awaited event reveals a ventriloquist dummy, who, despite being made of wood, seems to be capable of doing anything, including performing an elaborate production number that in many shots mimics elements of the “I’ve Got No Strings” sequence from Pinocchio. Gabbo’s ventriloquist announces that Gabbo’s new show will premiere the next day – directly opposite the time slot for the Krusty the Clown show. Despite all the press hype, Krusty pretends not to be worried (though a bowl full of burnt-out cigarette butts says otherwise). He claims he’s taken down the competition before, including the Special Olympics. But Gabbo seems to have a magnetic charm, and even a catch-phrase – “I’m a bad little boy” – that everyone latches onto, including Mayor Quimby when caught involved in a hit-man scandal, guaranteeing him re-election. Krusty’s ratings drop into the basement (even below Bumblebee Man on Channel Ocho), so he counters with a ventriloquist dummy of his own, not knowing a thing about how to operate it. When the dummy’s jaw falls out, and eye pops out of its socket, the kids in the gallery react in horror. Soon, Krusty can’t even hold onto rights to the Itchy and Scratch cartoons, and is forced to run Eastern Europe’s favorite cat and mouse team, Whacker and Parasite. The short is a stylistic send-up of Soyuz and Zagreb studios combined, with primitive cut-out animation, pattern backgrounds that float past the characters, and no action. The camera cuts back to Krusty at the conclusion of the short, his jaw dropped open and a limp cigarette butt hanging from his lips. “What the hell was that?” is all he can say.

Krusty Gets Kancelled (5/13/93) – Who is Gabbo? That is what TV spot ads and newspaper headlines scream for weeks, until an announcement comes that he will appear on TV. The long-awaited event reveals a ventriloquist dummy, who, despite being made of wood, seems to be capable of doing anything, including performing an elaborate production number that in many shots mimics elements of the “I’ve Got No Strings” sequence from Pinocchio. Gabbo’s ventriloquist announces that Gabbo’s new show will premiere the next day – directly opposite the time slot for the Krusty the Clown show. Despite all the press hype, Krusty pretends not to be worried (though a bowl full of burnt-out cigarette butts says otherwise). He claims he’s taken down the competition before, including the Special Olympics. But Gabbo seems to have a magnetic charm, and even a catch-phrase – “I’m a bad little boy” – that everyone latches onto, including Mayor Quimby when caught involved in a hit-man scandal, guaranteeing him re-election. Krusty’s ratings drop into the basement (even below Bumblebee Man on Channel Ocho), so he counters with a ventriloquist dummy of his own, not knowing a thing about how to operate it. When the dummy’s jaw falls out, and eye pops out of its socket, the kids in the gallery react in horror. Soon, Krusty can’t even hold onto rights to the Itchy and Scratch cartoons, and is forced to run Eastern Europe’s favorite cat and mouse team, Whacker and Parasite. The short is a stylistic send-up of Soyuz and Zagreb studios combined, with primitive cut-out animation, pattern backgrounds that float past the characters, and no action. The camera cuts back to Krusty at the conclusion of the short, his jaw dropped open and a limp cigarette butt hanging from his lips. “What the hell was that?” is all he can say.

The inevitable word comes down that Krusty’s show is cancelled. Krusty trues to audition for a dramatic role, but his kiss scene is blown when the girl presses up to his red nose, causing it to honk. “Next” calls the director. Having failed to maintain any nest egg, Krusty squanders his last ten dollars at the racetrack, on a filly who ignores the race to trot affectionately over to him at the railing. Bart and Lisa finally encounter Krusty on the street, destitute and carrying a sign, “Will drop pants for food.” They escort Krusty home, where they spot a wall full of celebrity photos showing Krusty with numerous stars he hob-nobbed with on his show in its heydey. Bart and Lisa decide that the key to restoring Krusty’s rightful place on the air is to call in favors from his old celebrity friends, for a star-studded Comeback Special. The climactic broadcast pays homage to Elvis, with Krusty performing a moving version of “Send in the Clowns” with Sideshow Mel, Johnny Carson juggling a 1987 Buick Skylark, Luke Perry blasted out of a cannon halfway across town, through walls, buildings, and an acid display in the Kwik-e-Mart, a semi-obscene rock number by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and a soulful duet between Krusty and Bette Midler on “The Wind Beneath My Wings”. Though we never actually see the downfall of Gabbo, this is apparently more competition than he can handle, and Krusty is restored to the airwaves, with Johnny Carson playing an accordion version of the Simpsons’ theme at a closing victory party.

The inevitable word comes down that Krusty’s show is cancelled. Krusty trues to audition for a dramatic role, but his kiss scene is blown when the girl presses up to his red nose, causing it to honk. “Next” calls the director. Having failed to maintain any nest egg, Krusty squanders his last ten dollars at the racetrack, on a filly who ignores the race to trot affectionately over to him at the railing. Bart and Lisa finally encounter Krusty on the street, destitute and carrying a sign, “Will drop pants for food.” They escort Krusty home, where they spot a wall full of celebrity photos showing Krusty with numerous stars he hob-nobbed with on his show in its heydey. Bart and Lisa decide that the key to restoring Krusty’s rightful place on the air is to call in favors from his old celebrity friends, for a star-studded Comeback Special. The climactic broadcast pays homage to Elvis, with Krusty performing a moving version of “Send in the Clowns” with Sideshow Mel, Johnny Carson juggling a 1987 Buick Skylark, Luke Perry blasted out of a cannon halfway across town, through walls, buildings, and an acid display in the Kwik-e-Mart, a semi-obscene rock number by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and a soulful duet between Krusty and Bette Midler on “The Wind Beneath My Wings”. Though we never actually see the downfall of Gabbo, this is apparently more competition than he can handle, and Krusty is restored to the airwaves, with Johnny Carson playing an accordion version of the Simpsons’ theme at a closing victory party.

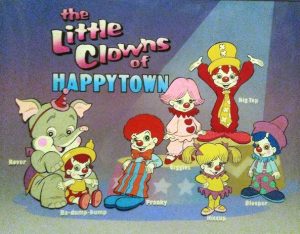

A few brief lines before leaving the subject of TV upon what must be one of the most forgotten series in Saturday-Morning network history, The Little Clowns of Happytown (Murakami Wolf Swenson/ABC Entertainment/Marvel Productions, 1987-88) which aired on ABC for one season, but remained in the form of 30-second bumpers for another couple of seasons to follow as “Joking Around With the Little Clowns.” It was a saccharine-sweet effort lacking in genuine plot or comedy, aimed at the tiny tots, and aspired to become the next Smurfs, using the same gimmick of substituting the word “clown” for every random noun or verb. It focused upon a community of junior clowns-in training, attempting to learn their trade in a grade-level clown school. It also featured “Clownimals” – a race of animals of various and varied species, who are somehow born with clown-painted faces. Too far out? Indeed. Animation is sub-par, and there’s not a laugh to be found in the writing. I find the project virtually unwatchable.

A few brief lines before leaving the subject of TV upon what must be one of the most forgotten series in Saturday-Morning network history, The Little Clowns of Happytown (Murakami Wolf Swenson/ABC Entertainment/Marvel Productions, 1987-88) which aired on ABC for one season, but remained in the form of 30-second bumpers for another couple of seasons to follow as “Joking Around With the Little Clowns.” It was a saccharine-sweet effort lacking in genuine plot or comedy, aimed at the tiny tots, and aspired to become the next Smurfs, using the same gimmick of substituting the word “clown” for every random noun or verb. It focused upon a community of junior clowns-in training, attempting to learn their trade in a grade-level clown school. It also featured “Clownimals” – a race of animals of various and varied species, who are somehow born with clown-painted faces. Too far out? Indeed. Animation is sub-par, and there’s not a laugh to be found in the writing. I find the project virtually unwatchable.

The earliest feature on our roster is Hanna-Barbera’s “Hey There, It’s Yogi Bear” (released through Columbia, 6/3/64), the first animated feature to star characters moving from the small to big screen. (Such a move would around the same time become a staple for Universal studios in the live-action field, resulting in two McHale’s Navy features and another for the Munsters.) This film is a nostalgia trip for me, as it was one of the first animated features I viewed theatrically. It was well-publicized, and an instant hit, although oddly, it took many years for it to make its way to small-screen re-broadcasts, H-B apparently preferring to push their new product rather than live off the royalties of the old. While the film was far from attempting to mimic the animation quality of the Tom and Jerry shorts, or H-B’s sequences contributed to “Anchors Aweigh”, “Dangerous When Wet”, or “Invitation To the Dance”, the artwork would show a considerable upgrade over that of the television series, with full-body movement, attractive character re-designs (particularly, a new, more charming brown-fur design for Cindy Bear with a much cuter face), and reasonably lush backgrounds. There were a few touches that told that some ex-MGM-ers were still at work for the directors, one particular tip-off being a blonde wig design in the musical number “St. Louie”, that looks lifted straight out of “Mutts About Racing” and “Cellbound”. A spunky music score was performed by Marty Paitch, providing several memorable original songs, which actually don’t do much to advance the plot, but still are generally a pleasure to the ear. On record, however, sales were not that brisk of a soundtrack album, which took the odd move for a children’s record of presenting only musical score and songs rather than a storyteller version of the plot (which was the reason I didn’t pick it up as a child). More commonly found and better known is a 7″ long-play 33 rpm “single” featuring the original voice cast, which fulfills the need for a storyteller synopsis, offered by Kelloggs as a box-top mail-in promotion, and featuring an alternate take of the film’s theme song which is a nice supplement to the soundtrack album.

The earliest feature on our roster is Hanna-Barbera’s “Hey There, It’s Yogi Bear” (released through Columbia, 6/3/64), the first animated feature to star characters moving from the small to big screen. (Such a move would around the same time become a staple for Universal studios in the live-action field, resulting in two McHale’s Navy features and another for the Munsters.) This film is a nostalgia trip for me, as it was one of the first animated features I viewed theatrically. It was well-publicized, and an instant hit, although oddly, it took many years for it to make its way to small-screen re-broadcasts, H-B apparently preferring to push their new product rather than live off the royalties of the old. While the film was far from attempting to mimic the animation quality of the Tom and Jerry shorts, or H-B’s sequences contributed to “Anchors Aweigh”, “Dangerous When Wet”, or “Invitation To the Dance”, the artwork would show a considerable upgrade over that of the television series, with full-body movement, attractive character re-designs (particularly, a new, more charming brown-fur design for Cindy Bear with a much cuter face), and reasonably lush backgrounds. There were a few touches that told that some ex-MGM-ers were still at work for the directors, one particular tip-off being a blonde wig design in the musical number “St. Louie”, that looks lifted straight out of “Mutts About Racing” and “Cellbound”. A spunky music score was performed by Marty Paitch, providing several memorable original songs, which actually don’t do much to advance the plot, but still are generally a pleasure to the ear. On record, however, sales were not that brisk of a soundtrack album, which took the odd move for a children’s record of presenting only musical score and songs rather than a storyteller version of the plot (which was the reason I didn’t pick it up as a child). More commonly found and better known is a 7″ long-play 33 rpm “single” featuring the original voice cast, which fulfills the need for a storyteller synopsis, offered by Kelloggs as a box-top mail-in promotion, and featuring an alternate take of the film’s theme song which is a nice supplement to the soundtrack album.

The film was not perfect, and took some risks, particularly on its musical numbers, as apparently, none of the principal voice cast were deemed capable of providing singing performances in their character roles. This again worked against sales of the music-only LP, which has no sign of Daws Butler or Don Messick – only singing substitutes who for the most part sound nothing like the speaking voices of the characters. Yet, onscreen staging of the numbers is handled for the most part quite well, so that the occasional intrusion of the fake voices is soon forgiven by the overall appeal of the presentation. The most far-out departure among these numbers is a romantic dream sequence between Yogi and Cundy as if on a gondola in Venice, for the number “Ven-e, Ven-o, Ven-a”. Boo Boo, who entertains during the number as a bumbling gondolier, gives away the self-promotion of substituting a Colpix records recording artist for Yogi’s singing, remarking, “Gee Yogi, you sing just like James Darren”, to which Yogi responds “And that ain’t easy.” (Darren, notably, made one other spot appearance with H-B, in the television Flintstones episode “Surfin’ Fred”.)

The film was not perfect, and took some risks, particularly on its musical numbers, as apparently, none of the principal voice cast were deemed capable of providing singing performances in their character roles. This again worked against sales of the music-only LP, which has no sign of Daws Butler or Don Messick – only singing substitutes who for the most part sound nothing like the speaking voices of the characters. Yet, onscreen staging of the numbers is handled for the most part quite well, so that the occasional intrusion of the fake voices is soon forgiven by the overall appeal of the presentation. The most far-out departure among these numbers is a romantic dream sequence between Yogi and Cundy as if on a gondola in Venice, for the number “Ven-e, Ven-o, Ven-a”. Boo Boo, who entertains during the number as a bumbling gondolier, gives away the self-promotion of substituting a Colpix records recording artist for Yogi’s singing, remarking, “Gee Yogi, you sing just like James Darren”, to which Yogi responds “And that ain’t easy.” (Darren, notably, made one other spot appearance with H-B, in the television Flintstones episode “Surfin’ Fred”.)

Plot of the film is actually more of a series of entertaining episodic events rather than a single storyline, but they are strung together reasonably sequentially, so that audience interest is generally maintained with the appearance of a cohesive whole. Yogi is up to his old tricks at the dawn of spring, while Cindy has aspirations toward snagging the picnic-loving bear as her permanent beau in matrimony. Yogi pushes his luck with Ranger Smith, protesting enforcement of the park rules with an ultimatum that the rules go, or he goes. “When you put it that way, you leave me no choice”, says Smith, placing a tag around Yogi’s neck, identifying him for shipment to the San Diego Zoo. “What’s the medal for – for stupidity?”, says Yogi. But Yogi pulls the usual fast one, letting a hillbilly bear named Cornpone take on the tag, on the pretense that the tag is his ticket to the sunshine and bright lights of California – the movie capitol. Knowing that if Smith finds out about the switch, there will be the devil to pay, Yogi tells no one of the substitution – not even Boo Boo, and disappears into the deep woods until the heat dies down. Still requiring his needed sustenance, Yogi assumes the role of the mysterious “Brown Phantom”, filching picnic baskets in Robin Hood style. Smith doesn’t know who to blame for the crime wave, assuming Yogi to be already gone, and roams the back-stretches of the forest in his jeep, announcing to all the bears with a megaphone that if he lays hands on the Brown Phantom, it’ll be a one-way ticket to the zoo. By this time, Cundy has already gotten wind of Yogi’s being shipped-out by the Ranger, and she views this as her opportunity to be reunited with Yogi in the zoo. Cindy thus does something she’s never done before – grabs a picnic basket, and lets Smith catch her with the goods. Smith still can’t believe she could be the Brown Phantom. “If you’d ever done one little thing wrong…” Cindy proves she is capable – by tossing a berry pie in the ranger’s face. “And that did it”, responds the Ranger.

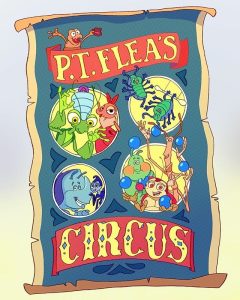

Cindy happily travels in a crate aboard a train, anticipating her reunion with Yogi, and is temporarily entertained by a quartet of singing bears on board for the same destination. However, to her dismay, she discovers that the bears are not bound for San Diego, but St, Louis. It turns out the San Diego zoo didn’t need any more bears, so Smith changed Cindy’s destination to the St. Louis Zoo. As Cindy falls asleep crying in her crate, the train’s vibrations shift her crate closer and closer to an open box-car door, until it falls out, smashing and dumping Cinfy along the side of the railway bed. Cindy uses the opportunity to make an escape, though she has no idea how to find her way back to either Jellystone Park or San Diego. A circus truck lumbers along in the night from the Chizzling Brothers Circus, containing the brothers – a ringmaster named Grifter (Mel Blanc) and his assistant named Snivley (J. Pat O’Malley) – and their pet, a dog named Mugger. The dog is the premiere appearance, in almost fully-perfected model, of the snickering hound who would become better-known as Muttley, considerably re-designed from similar snickering mutts featured in the Huckleberry Hound show. Mugger is of ferocious, teeth-chomping nature, and doubles in costume as the circus lion. The brothers are down and out, with their elephant and calliope repossessed, and their acts having walked out. However, they consider their fortune made when Mugger gets whiff of Cindy in the woods, and jumps out the truck window after her. Cindy heads for a telephone pole with Mugger’s jaws snapping behind her, and when the brothers arrive at the base of the pole, they observe Cindy, using her parasol for balance, attempting to make an escape by tightrope walking on the telephone wires. Grifter orders Snivley to obtain a net from the truck, and as a trap is laid for Cindy, all he can see is dollar signs in his eyes at the thought of his new attraction – Cindy, the high-wire bear.

Cindy happily travels in a crate aboard a train, anticipating her reunion with Yogi, and is temporarily entertained by a quartet of singing bears on board for the same destination. However, to her dismay, she discovers that the bears are not bound for San Diego, but St, Louis. It turns out the San Diego zoo didn’t need any more bears, so Smith changed Cindy’s destination to the St. Louis Zoo. As Cindy falls asleep crying in her crate, the train’s vibrations shift her crate closer and closer to an open box-car door, until it falls out, smashing and dumping Cinfy along the side of the railway bed. Cindy uses the opportunity to make an escape, though she has no idea how to find her way back to either Jellystone Park or San Diego. A circus truck lumbers along in the night from the Chizzling Brothers Circus, containing the brothers – a ringmaster named Grifter (Mel Blanc) and his assistant named Snivley (J. Pat O’Malley) – and their pet, a dog named Mugger. The dog is the premiere appearance, in almost fully-perfected model, of the snickering hound who would become better-known as Muttley, considerably re-designed from similar snickering mutts featured in the Huckleberry Hound show. Mugger is of ferocious, teeth-chomping nature, and doubles in costume as the circus lion. The brothers are down and out, with their elephant and calliope repossessed, and their acts having walked out. However, they consider their fortune made when Mugger gets whiff of Cindy in the woods, and jumps out the truck window after her. Cindy heads for a telephone pole with Mugger’s jaws snapping behind her, and when the brothers arrive at the base of the pole, they observe Cindy, using her parasol for balance, attempting to make an escape by tightrope walking on the telephone wires. Grifter orders Snivley to obtain a net from the truck, and as a trap is laid for Cindy, all he can see is dollar signs in his eyes at the thought of his new attraction – Cindy, the high-wire bear.

Yogi tires of his hermitage as the Brown Phantom, and misses Boo Boo and mostly Cindy. His inner-self tells him to go back and make a clean breast of it to the ranger, hopefully to be accepted back and re-win the heart of Cindy. But outside the ranger station, Yogi hears Smith receive the call that Cindy never reached St, Louis. Yogi bursts in in the panic of the moment, attempting to take command, and directing Smith to organize searching parties in the back-country of four states, while Yogi monitors the command post, and stirs up things in Washington. Smith is about to zoom away on his mission, when he realizes it is Yogi who is directing him. Smith corrals Yogi in his own desk chair, and attempts to lock Yogi in a closet until the zoo comes back for him, but Yogi beats Smith out of the closet, and locks Smith in. A wild cross-country jaunt ensues, as Yogi, who becomes reunited with Boo Boo, plots an escape from the park and a series of methods to hitch transportation to reach Cindy. The ornate sequence involves transport by helium-filled rubber life raft, dump truck, hay wagon, automobile carruer, jet plane, and rail, finally landing our heroes in the same town where the crcus is playing. A cutaway to the big top shows how the brothers are accomplishing their feature act. Cindy remains locked in a cage, released only at show time, when Mugger begins snapping at her heels again. In like fashion to the telephone pole incident, Mugger pursues her up a pole inside the tent to the high-wire platform, leaving her only the wire as a means of getting away, and rousing applause from the crowd as Cindy balances.

Yogi tires of his hermitage as the Brown Phantom, and misses Boo Boo and mostly Cindy. His inner-self tells him to go back and make a clean breast of it to the ranger, hopefully to be accepted back and re-win the heart of Cindy. But outside the ranger station, Yogi hears Smith receive the call that Cindy never reached St, Louis. Yogi bursts in in the panic of the moment, attempting to take command, and directing Smith to organize searching parties in the back-country of four states, while Yogi monitors the command post, and stirs up things in Washington. Smith is about to zoom away on his mission, when he realizes it is Yogi who is directing him. Smith corrals Yogi in his own desk chair, and attempts to lock Yogi in a closet until the zoo comes back for him, but Yogi beats Smith out of the closet, and locks Smith in. A wild cross-country jaunt ensues, as Yogi, who becomes reunited with Boo Boo, plots an escape from the park and a series of methods to hitch transportation to reach Cindy. The ornate sequence involves transport by helium-filled rubber life raft, dump truck, hay wagon, automobile carruer, jet plane, and rail, finally landing our heroes in the same town where the crcus is playing. A cutaway to the big top shows how the brothers are accomplishing their feature act. Cindy remains locked in a cage, released only at show time, when Mugger begins snapping at her heels again. In like fashion to the telephone pole incident, Mugger pursues her up a pole inside the tent to the high-wire platform, leaving her only the wire as a means of getting away, and rousing applause from the crowd as Cindy balances.

As a circus parade passes, Yogi and Boo Boo join the spirit with their own replica parade on the other side of a fence, using routine items thrown away in the back alleys for parade decorations, and leading a squad of marching alley cats (the musical number “Ash Can Parade”). They encounter a poster advertising Cinfy’s performance tonight. Yogi believes Cindy ran away for the bright lights rather than to follow him, but Boo Boo convinces him to see her and at least wish her luck. Yogi slips into the show without a ticket, by assuming a clown’s disguise. Unfortunately, he is recruited as the driver of the clown car, which systematically explodes apart, leaving Yogi riding one wheel. He bounces into a net, and from that into the backstage area, encountering Cindy in her cage. Cindy quickly explains that she is not a star, but a prisoner, and Yogi sets himself for a confrontation with the management. The brothers and Mugger are in their own tent, counting up their pile of cash, and Snivley speculates that if they had two bears, they’d reap twice the money. “Where are we supposed to find another bear?” snarls Grifter. “At your shoulder, sir”, pipes up Yogi. The brothers are startled, until Yogi claims he is on a government mission to return Cindy, a government-protected bear, to her home in Jellystone. “Do they know you’re here?” asks Grifter. “Are you joshing, sir?’ responds Yogi, letting slip that bears are not allowed outside the park, and asking that this be their little secret. Grifter sees his chance, and, leading Yogi to Cindy’s cage, pushes Yogi in and locks the door, posting Mugger as guard on a throw-rug outside the cage. But Boo Boo is still free, and that night, slips into the brothers’ tent to retrieve the cage key from under Snivley’s hat. In the process, Boo Boo has the foresight to tie loops in both ends of a short rope, and throw the loops around the respective ankles of the sleeping brothers. He slips behind Mugger, carrying the key, and plays ring-around-a-rosy as Mugger scans the tent in a circle for an intruder, staying directly behind Mugger out of the dog’s view. Mugger gets smart, and looks down between his own legs. But Yogi picks up Boo Boo in the nick of time so that Boo Boo’s ankles don’t show. The key is delivered to Yogi, and he and Cindy slip out, then Yogi carefully pulls the throw rug holding the now-sleeping Mugger into the cage, locking the cage door upon him. As Mugger awakens and snarls, only to find himself behind bars, Yogi gives him a trademark Muttley snicker, and departs. Boo Boo finds an escape vehicle – but it s the clown car. The noise of the vehicle awakens the brothers, who attempt to race out of the tent, but snag the rope looped upon their ankles around the tent pole. They bring the canvas down upon them to prevent a timely exit, while the bears roll in the clown car, enduring explosion after explosion, until Yogi is left carrying the others, balancing upon the last car tire like a unicycle down the road.

As a circus parade passes, Yogi and Boo Boo join the spirit with their own replica parade on the other side of a fence, using routine items thrown away in the back alleys for parade decorations, and leading a squad of marching alley cats (the musical number “Ash Can Parade”). They encounter a poster advertising Cinfy’s performance tonight. Yogi believes Cindy ran away for the bright lights rather than to follow him, but Boo Boo convinces him to see her and at least wish her luck. Yogi slips into the show without a ticket, by assuming a clown’s disguise. Unfortunately, he is recruited as the driver of the clown car, which systematically explodes apart, leaving Yogi riding one wheel. He bounces into a net, and from that into the backstage area, encountering Cindy in her cage. Cindy quickly explains that she is not a star, but a prisoner, and Yogi sets himself for a confrontation with the management. The brothers and Mugger are in their own tent, counting up their pile of cash, and Snivley speculates that if they had two bears, they’d reap twice the money. “Where are we supposed to find another bear?” snarls Grifter. “At your shoulder, sir”, pipes up Yogi. The brothers are startled, until Yogi claims he is on a government mission to return Cindy, a government-protected bear, to her home in Jellystone. “Do they know you’re here?” asks Grifter. “Are you joshing, sir?’ responds Yogi, letting slip that bears are not allowed outside the park, and asking that this be their little secret. Grifter sees his chance, and, leading Yogi to Cindy’s cage, pushes Yogi in and locks the door, posting Mugger as guard on a throw-rug outside the cage. But Boo Boo is still free, and that night, slips into the brothers’ tent to retrieve the cage key from under Snivley’s hat. In the process, Boo Boo has the foresight to tie loops in both ends of a short rope, and throw the loops around the respective ankles of the sleeping brothers. He slips behind Mugger, carrying the key, and plays ring-around-a-rosy as Mugger scans the tent in a circle for an intruder, staying directly behind Mugger out of the dog’s view. Mugger gets smart, and looks down between his own legs. But Yogi picks up Boo Boo in the nick of time so that Boo Boo’s ankles don’t show. The key is delivered to Yogi, and he and Cindy slip out, then Yogi carefully pulls the throw rug holding the now-sleeping Mugger into the cage, locking the cage door upon him. As Mugger awakens and snarls, only to find himself behind bars, Yogi gives him a trademark Muttley snicker, and departs. Boo Boo finds an escape vehicle – but it s the clown car. The noise of the vehicle awakens the brothers, who attempt to race out of the tent, but snag the rope looped upon their ankles around the tent pole. They bring the canvas down upon them to prevent a timely exit, while the bears roll in the clown car, enduring explosion after explosion, until Yogi is left carrying the others, balancing upon the last car tire like a unicycle down the road.

More episodes follow, none of them dealing with the circus, finally climaxing with a police pursuit of the bears in the big city, and an intervention by Ranger Smith via helicopter as television broadcasts images of the bears stranded atop a skyscraper under construction. The bears are finally rescued by Smith, and a call from the Commissioner does not result in Smith’s firing, but a commendation for devotion to duty and love of animals. For many years before the film resurfaced on television, and to this day, I can still clearly see in my mind’s eye the image of Smith’s helicopter musically dancing through the skies into the sunset, as I originally saw it on a large drive-in movie screen in Boston, Massachusetts so many years ago. A pleasant remembrance of a memorable film.

More episodes follow, none of them dealing with the circus, finally climaxing with a police pursuit of the bears in the big city, and an intervention by Ranger Smith via helicopter as television broadcasts images of the bears stranded atop a skyscraper under construction. The bears are finally rescued by Smith, and a call from the Commissioner does not result in Smith’s firing, but a commendation for devotion to duty and love of animals. For many years before the film resurfaced on television, and to this day, I can still clearly see in my mind’s eye the image of Smith’s helicopter musically dancing through the skies into the sunset, as I originally saw it on a large drive-in movie screen in Boston, Massachusetts so many years ago. A pleasant remembrance of a memorable film.

We’re Back!: A Dinosaur’s Story (Amblin Entertainment/Universal, 11/24/93) is a film you start out wanting to like, yet somehow fail to in the end. It packs star power (John Goodman as Rex, and likely the only voice-over work of Walter Kronkite (Captain Neweyes) and Julia Child. It’s animation is top -notch, with flashy special effects, smoothly-executed and expressive character action, and nicely-chosen camera angles. It seems to have everything going for it on the creative and technical ends. Except it’s source story, culled from a children’s book, has too many implausibles to capture the imagination of all but the youngest viewers, and, while perhaps not reaching quite the problem-level of a Don Bluth production, too sudden and simple a resolution of climactic plot points to leave the viewer with a true feeling of satisfaction and closure. The result was a certified bomb at the box-office and received mixed critical reviews, all in spite of the extreme labor and effort that had to have gone into bringing the story to the screen.

We’re Back!: A Dinosaur’s Story (Amblin Entertainment/Universal, 11/24/93) is a film you start out wanting to like, yet somehow fail to in the end. It packs star power (John Goodman as Rex, and likely the only voice-over work of Walter Kronkite (Captain Neweyes) and Julia Child. It’s animation is top -notch, with flashy special effects, smoothly-executed and expressive character action, and nicely-chosen camera angles. It seems to have everything going for it on the creative and technical ends. Except it’s source story, culled from a children’s book, has too many implausibles to capture the imagination of all but the youngest viewers, and, while perhaps not reaching quite the problem-level of a Don Bluth production, too sudden and simple a resolution of climactic plot points to leave the viewer with a true feeling of satisfaction and closure. The result was a certified bomb at the box-office and received mixed critical reviews, all in spite of the extreme labor and effort that had to have gone into bringing the story to the screen.

At the root of the story line are a pair of human brothers, both geniuses, but with polar -opposite motivations. Captain Neweyes is a purely good-guy, whose inventions include a wish-radio, capable of tuning in to the thoughts and desires of the population, particularly the youth, who express a recurring wish to see real dinosaurs. Neweyes has also perfected time-travel via a saucer-shaped ship, and has further invented a “cereal” called “Brain Grain”, which endows common and exotic beasts with the powers of speech, reasoned thinking, and civilization of wild instincts. The second brother, Professor Screweyes (named for a childhood incident in which a crow pecked out one eye, leaving him to substitute for such optic with a large metal screw inserted in one eye-socket), is pure greed and evil, countering his brother’s inventions with a fear radio that tunes in on mankind’s darkest fears, an unidentified hypnotic power built into his screw-eye to overcome the will-power of the viewer, and a counter-antidote to Neweyes’ cereal, in the form of a pill called “Brain Drain”. Neweyes aspires to make children of the world happy by bringing back real dinosaurs to the modern world from the distant past. Screweyes, on the other hand, unknowing of his brother’s quest, hones his skills upon creating an “Eccentric Circus”, attempting to provide all the horrors humans fear most as a form of lucrative entertainment. Four dinosaurs, including Rex (a T-Rex) and a pterodactyl, among others (character traits are rather un-notable among these dinosaurs besides Rex – another point upon with critics dwelled in their reviews of the film), are rounded up by Neweyes’ space-time ship, fed Brain Grain, and filled-in on Neweyes’ plans to drop them in the East River off of Manhattan Island, with instructions to meet up with the curator of the Museum of Natural History (Julia Child) for their planned secret exhibition – and a further warning to avoid contact with Screweyes. Things don’t go according to plan, as the dinosaurs keep missing the Museum curator (who in her own dithered manner is too excited to stay in one place, and putters around town trying to drum up publicity for the exhibit), and also meet up with a couple of runaway kids who have their mind set upon joining the circus – the only such show in town of course being that of Screweyes in Central Park. A highlight of the film is the dinosaurs’ infiltrating of a Macy’s parade as if part of an animatronic float, only to be discovered, leading to a wild police chase. One good gag has the pterodactyl go unnoticed by police helicopters, by posing as a building gargoyle.

The action moves to Screweyes’ circus, which the kids reach first. The dinosaurs discover who runs the show from a publicity poster, and Rex remarks, “That’s the bad guy.” They proceed to the show, but too late. The kids have already encountered Screweyes, who has presented them with a contract to sign – on a blank piece of parchment. “I like to keep things simple”, he tells the kids to explain the blank paper. He pricks the boy’s finger with a pen point, and has him sign the contract in blood, with the girl following. Then, the page magically fills with long-term control clauses over them, including exclusive control over their will power. (Another convenient implausibility – it seemed that the two brothers’ powers were supposed to root from science – but how do you explain this magic parchment?) The dinosaurs arrive, and one look at them tells Screweyes his brother must be behind this. Screweyes sees possibilities for his own gain in the dinosaurs, and, discovering that the dinosaurs are the kids’ friends, Screweyes demonstrates to the dinos what he intends to do with the kids, by hypnotizing them ro take a half-dose of his Brain Drain, devolving them into wild chimpanzees. The dinos protest, but Screweyes will not be Intimidated, knowing the Brain Grain has civilized the dinos and taken the fight out of them, so that they will be forced to honor his contract in a civilized manner. However, he offers them terms to save the kids – take their place under his control, and submit to the Brain Drain to devolve them back to their pre-historic selves. The dinos reluctantly consent, and the kids’ contracts are torn up, while the dinos are led away to be shackled in chains and restored to raging monsters.

The action moves to Screweyes’ circus, which the kids reach first. The dinosaurs discover who runs the show from a publicity poster, and Rex remarks, “That’s the bad guy.” They proceed to the show, but too late. The kids have already encountered Screweyes, who has presented them with a contract to sign – on a blank piece of parchment. “I like to keep things simple”, he tells the kids to explain the blank paper. He pricks the boy’s finger with a pen point, and has him sign the contract in blood, with the girl following. Then, the page magically fills with long-term control clauses over them, including exclusive control over their will power. (Another convenient implausibility – it seemed that the two brothers’ powers were supposed to root from science – but how do you explain this magic parchment?) The dinosaurs arrive, and one look at them tells Screweyes his brother must be behind this. Screweyes sees possibilities for his own gain in the dinosaurs, and, discovering that the dinosaurs are the kids’ friends, Screweyes demonstrates to the dinos what he intends to do with the kids, by hypnotizing them ro take a half-dose of his Brain Drain, devolving them into wild chimpanzees. The dinos protest, but Screweyes will not be Intimidated, knowing the Brain Grain has civilized the dinos and taken the fight out of them, so that they will be forced to honor his contract in a civilized manner. However, he offers them terms to save the kids – take their place under his control, and submit to the Brain Drain to devolve them back to their pre-historic selves. The dinos reluctantly consent, and the kids’ contracts are torn up, while the dinos are led away to be shackled in chains and restored to raging monsters.

The kids awaken the next morning, the pills having worn off, back to their normal selves. A kindly clown named Stubbs (improbably under Screweyes’ employ, though Screweyes appears to have no use for comedy in his show, and thus seemingly included in the script purely for comic relief) offers them breakfast, then tells them they are free. But what about the dinosaurs? “You’re not gonna like it”, he remarks, taking them to a darkened tent to see their friends, restored to all their primitive savagery, and having no recognition of the kids. The boy insists that Stubbs get them into the show tonight to see if there is some way to help the dinos. Stubbs puts them in costume as devil imps, and they participate in a parade of horrors as a visually-spectacular opening act of Screweyes’ performance that night, with special-effects ghosts, dragons, devils, and other things that go bump in the night giving the thrill-seeking audience the willies. Finally, Screweyes unveils the ultimate “monsters” in the form of the dinosaur quartet. The audience is panic-stricken, but the chains around the beasts’ ankles hold fast. That is, until Screweyes attempts to control Rex with his hypnotic screw-eye, and orders his assistants to unlock Rex’s chains. Rex steps forward on command, and obeys as told – until a strange mishap disrupts the performance. For reasons unknown (another implausibility), crows continue to have an affinity for Screweyes (is it his flavor?), and hang around in the upper-reaches of the circus tent. One swoops down toward a special-effects control panel, and randomly pecks a red button marked “Flare”. An explosion of light hits Rex’s eye, somehow breaking the hypnotic trance Screweyes has placed upon him. Before Screweyes can exert his power again, Rex seizes Screweyes up in his giant clawed hand, and holds him precariously close to his snapping, snarling jaws, with apparent intent to devour him. The boy throws back the head of his imp costume, and races forward into the arena, while the girl wishes over and over that nothing bad happen. The boy stands at Rex’s feet, and pleads in heartfelt manner that Rex not do this. He points out that Rex is better than this, and that Rex has nothing to prove, as he, after all, is already “the original tough-guy”, and need not act the bully to prove this point. The boy gently strokes Rex’s leg, and a close-up on Rex’s savage face discloses a softening in expression in his eye. Miraculously, the effect of the Brain Drain is reversed, and Rex returns to civilized form. Similar remarks to the other three dinos restore them to good-guys as well. (A bit pat for a solution – why should even the wearing off or countermanding of the Brain Drain suddenly convert the dinosaurs to the full power of the Brain Grain, when they obviously haven’t had a bowl of the stuff for a while? Why not some state of happy medium between the savage and the intelligent? Of course, then we wouldn’t have a happy ending.) The girl’s wishes also have been picked up on Captain Neweyes’ wish radio, zeroing-in his ship upon the scene for a last-minute intervention, picking up the dinosaurs and kids to finally get them safely to the museum. In a totally weird and too-convenient moment, Screweyes, left alone in the tent (as Stubbs has finally quit too), remarks in almost a half-whimper that when he is left alone, he becomes frightened too. Suddenly, the crows in the tent descend upon him, assume a formation eclipsing Screweyes’ form, then disperse, with Screweyes nowhere to be seen, presumably devoured! A solitary crow pecks at the metal screw from his eye socket left on the ground, shorting out its power, then flies off with it. Too quick, too upsetting, and too unbelievable for a finish. The dinosaurs make a living posing as statues in the museum until alone with the kids, then fraternize with them as “our little secret”. But occasionally, in their off-time, they take in a game of golf in the early-morning light, which is where we leave Rex for the fade-out.

The kids awaken the next morning, the pills having worn off, back to their normal selves. A kindly clown named Stubbs (improbably under Screweyes’ employ, though Screweyes appears to have no use for comedy in his show, and thus seemingly included in the script purely for comic relief) offers them breakfast, then tells them they are free. But what about the dinosaurs? “You’re not gonna like it”, he remarks, taking them to a darkened tent to see their friends, restored to all their primitive savagery, and having no recognition of the kids. The boy insists that Stubbs get them into the show tonight to see if there is some way to help the dinos. Stubbs puts them in costume as devil imps, and they participate in a parade of horrors as a visually-spectacular opening act of Screweyes’ performance that night, with special-effects ghosts, dragons, devils, and other things that go bump in the night giving the thrill-seeking audience the willies. Finally, Screweyes unveils the ultimate “monsters” in the form of the dinosaur quartet. The audience is panic-stricken, but the chains around the beasts’ ankles hold fast. That is, until Screweyes attempts to control Rex with his hypnotic screw-eye, and orders his assistants to unlock Rex’s chains. Rex steps forward on command, and obeys as told – until a strange mishap disrupts the performance. For reasons unknown (another implausibility), crows continue to have an affinity for Screweyes (is it his flavor?), and hang around in the upper-reaches of the circus tent. One swoops down toward a special-effects control panel, and randomly pecks a red button marked “Flare”. An explosion of light hits Rex’s eye, somehow breaking the hypnotic trance Screweyes has placed upon him. Before Screweyes can exert his power again, Rex seizes Screweyes up in his giant clawed hand, and holds him precariously close to his snapping, snarling jaws, with apparent intent to devour him. The boy throws back the head of his imp costume, and races forward into the arena, while the girl wishes over and over that nothing bad happen. The boy stands at Rex’s feet, and pleads in heartfelt manner that Rex not do this. He points out that Rex is better than this, and that Rex has nothing to prove, as he, after all, is already “the original tough-guy”, and need not act the bully to prove this point. The boy gently strokes Rex’s leg, and a close-up on Rex’s savage face discloses a softening in expression in his eye. Miraculously, the effect of the Brain Drain is reversed, and Rex returns to civilized form. Similar remarks to the other three dinos restore them to good-guys as well. (A bit pat for a solution – why should even the wearing off or countermanding of the Brain Drain suddenly convert the dinosaurs to the full power of the Brain Grain, when they obviously haven’t had a bowl of the stuff for a while? Why not some state of happy medium between the savage and the intelligent? Of course, then we wouldn’t have a happy ending.) The girl’s wishes also have been picked up on Captain Neweyes’ wish radio, zeroing-in his ship upon the scene for a last-minute intervention, picking up the dinosaurs and kids to finally get them safely to the museum. In a totally weird and too-convenient moment, Screweyes, left alone in the tent (as Stubbs has finally quit too), remarks in almost a half-whimper that when he is left alone, he becomes frightened too. Suddenly, the crows in the tent descend upon him, assume a formation eclipsing Screweyes’ form, then disperse, with Screweyes nowhere to be seen, presumably devoured! A solitary crow pecks at the metal screw from his eye socket left on the ground, shorting out its power, then flies off with it. Too quick, too upsetting, and too unbelievable for a finish. The dinosaurs make a living posing as statues in the museum until alone with the kids, then fraternize with them as “our little secret”. But occasionally, in their off-time, they take in a game of golf in the early-morning light, which is where we leave Rex for the fade-out.

Animal Crackers (Blue Dream Studios, Beijing Wen Hua Dong Run Investment Co., 7/24/20) was a film long-delayed in release through the failure of multiple distributing companies, and missed a theatrical release during the pandemic, only appearing on Netflix. It thus escaped my radar without even so much as a blip. It is, technically, a competent rendering of CGI animation, and another film packing a good deal of voicing star-power (including the familiar voices of Patrick Worburton, Gilbert Gottfried, Sanny DeVito, and Sylvester Stallone. It is another feature that one hopes will rise to the level of great expectations – but something again falls flat. Principal problems here appear to be both story-line and direction. For a first problem, the quite-basic gimmick of the story seems to take an interminable amount of turns to set up, beginning in extended flashback through a few generations of characters in a family-line of circus performers, introducing so many characters one rapidly finds oneself losing count. Principals again appear to be two brothers, a flamboyant, ego-centric ringmaster named Horatio and his younger brother, Bob, who just wants to entertain and be a clown. A gypsy fortune teller from the sideshow introduces her lovely niece from the old country, and both Bob and Horatio are smitten, as the grl becomes new bareback rider in the troupe. Horatio, full of himself, believes he has the edge in charm, but Bob gets the acceptance of marriage proposal. A schism occurs between the brothers, with Bob and the girl ousted from the show. However, Bob somehow forms his own circus, which eclipses Horatio’s, with a seemingly magical array of animals. No one seems to quite know how Bob managed to acquire such a menagerie, but, as the plot moves into yet another generation of players, including a nephew who becomes the central character of the story and his young wife, both moved from their original attraction to circus life to a mundane career in the girl’s dad’s dog biscuit company, a secret as to the source of Bob’s success is revealed at what is believed to be a funeral for Bob.

Animal Crackers (Blue Dream Studios, Beijing Wen Hua Dong Run Investment Co., 7/24/20) was a film long-delayed in release through the failure of multiple distributing companies, and missed a theatrical release during the pandemic, only appearing on Netflix. It thus escaped my radar without even so much as a blip. It is, technically, a competent rendering of CGI animation, and another film packing a good deal of voicing star-power (including the familiar voices of Patrick Worburton, Gilbert Gottfried, Sanny DeVito, and Sylvester Stallone. It is another feature that one hopes will rise to the level of great expectations – but something again falls flat. Principal problems here appear to be both story-line and direction. For a first problem, the quite-basic gimmick of the story seems to take an interminable amount of turns to set up, beginning in extended flashback through a few generations of characters in a family-line of circus performers, introducing so many characters one rapidly finds oneself losing count. Principals again appear to be two brothers, a flamboyant, ego-centric ringmaster named Horatio and his younger brother, Bob, who just wants to entertain and be a clown. A gypsy fortune teller from the sideshow introduces her lovely niece from the old country, and both Bob and Horatio are smitten, as the grl becomes new bareback rider in the troupe. Horatio, full of himself, believes he has the edge in charm, but Bob gets the acceptance of marriage proposal. A schism occurs between the brothers, with Bob and the girl ousted from the show. However, Bob somehow forms his own circus, which eclipses Horatio’s, with a seemingly magical array of animals. No one seems to quite know how Bob managed to acquire such a menagerie, but, as the plot moves into yet another generation of players, including a nephew who becomes the central character of the story and his young wife, both moved from their original attraction to circus life to a mundane career in the girl’s dad’s dog biscuit company, a secret as to the source of Bob’s success is revealed at what is believed to be a funeral for Bob.

A mysterious wooden box containing a stash of aged animal crackers somehow falls into out hero’s hands in a melee at the funeral (where Horatio tries to claim title to his brother’s former show). Escaping from a free-for-all fracas between Horatio’s henchmen and the circus performers, the nephew samples one of the crackers – and instantly transforms into a hamster (the animal whose shape was depucted by the cookie). It eventually is deduced that the crackers have been subjected to gypsy magic by the fortune teller, and were the source of Bob’s fantastic animals. Everyone wants the crackers, and Horatio eventually entraps the nephew into working for him as a changeable animal performer. A revolt finally takes place, with everyone in the show scrambling to munch cookies, and a transformation jubilee punctuating what should be an epic battle. The problem is, too many characters are involved in the sequence, and visual identities change so frequently, that the whole thing becomes nothing but confusion, with no meaningful ability to tell who us who, or even good guy from bad guy. Direction is too frenetic, with too many quick shots to follow coherently. Moreover, the transformations appear quite random, and not well-though out for the most part as to practical use of the animals’ respective powers (excepting a human cannonball who is first launched skyward as a human, then transforms into a rhinoceros with a bite of cookie to spear Horatio in the belly in his state as a flying dragon-like beast). Disney had great success with a similar-themed sequence in “The Sword and the Stone”’s wizard’s duel between Merlin and Madam Mim – but the battle here comes nowhere close to delivering the laughs or wit of Disney. Instead of Merlin’s clever changing into a germ to win his battle, out hero merely tosses a hamster cookie into the villain’s open mouth, reducing him to harmless form. The villain takes out his frustrations by running on a hamster wheel in a cage, while everything outside somehow straightens itself out. I confess to skipping over details as to where antidotes to the cookies came from, or figuring out how Bob turns out to be not dead at all, but merely converted into a dog, and I did not stick around for the plot-exposition ending, as by this time, I really could have cared less.

A mysterious wooden box containing a stash of aged animal crackers somehow falls into out hero’s hands in a melee at the funeral (where Horatio tries to claim title to his brother’s former show). Escaping from a free-for-all fracas between Horatio’s henchmen and the circus performers, the nephew samples one of the crackers – and instantly transforms into a hamster (the animal whose shape was depucted by the cookie). It eventually is deduced that the crackers have been subjected to gypsy magic by the fortune teller, and were the source of Bob’s fantastic animals. Everyone wants the crackers, and Horatio eventually entraps the nephew into working for him as a changeable animal performer. A revolt finally takes place, with everyone in the show scrambling to munch cookies, and a transformation jubilee punctuating what should be an epic battle. The problem is, too many characters are involved in the sequence, and visual identities change so frequently, that the whole thing becomes nothing but confusion, with no meaningful ability to tell who us who, or even good guy from bad guy. Direction is too frenetic, with too many quick shots to follow coherently. Moreover, the transformations appear quite random, and not well-though out for the most part as to practical use of the animals’ respective powers (excepting a human cannonball who is first launched skyward as a human, then transforms into a rhinoceros with a bite of cookie to spear Horatio in the belly in his state as a flying dragon-like beast). Disney had great success with a similar-themed sequence in “The Sword and the Stone”’s wizard’s duel between Merlin and Madam Mim – but the battle here comes nowhere close to delivering the laughs or wit of Disney. Instead of Merlin’s clever changing into a germ to win his battle, out hero merely tosses a hamster cookie into the villain’s open mouth, reducing him to harmless form. The villain takes out his frustrations by running on a hamster wheel in a cage, while everything outside somehow straightens itself out. I confess to skipping over details as to where antidotes to the cookies came from, or figuring out how Bob turns out to be not dead at all, but merely converted into a dog, and I did not stick around for the plot-exposition ending, as by this time, I really could have cared less.

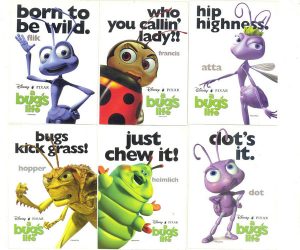

A Bugs’ Life (Pixar/Disney, 11/14/98), might also be sub-titled “A Perfect Film”. It defines the early Pixar brand along with “Toy Story”, and set the bar for all CGI as we presently know it. Prepared in a production race with Woody Allen’s “Antz” from Dreamworks, it was the last of the two to hit the big screen – yet essentially eclipsed the Allen vehicle to the point of nearly driving the prior film from viewer memory. Its vibrant color schemes and richly-detailed animation blotted-out the Allen images of dark tunnels and rigid earth-toned uniformity that were more-suited to Allen’s dark tale of militarism and societal conformity, and immersed us in a counter-world which, while fraught with danger and peril, still had a charm and appeal that we might want to visit, leading to a California Adventure “land” that continues to endure as a crowd-pleaser to the present day.

A Bugs’ Life (Pixar/Disney, 11/14/98), might also be sub-titled “A Perfect Film”. It defines the early Pixar brand along with “Toy Story”, and set the bar for all CGI as we presently know it. Prepared in a production race with Woody Allen’s “Antz” from Dreamworks, it was the last of the two to hit the big screen – yet essentially eclipsed the Allen vehicle to the point of nearly driving the prior film from viewer memory. Its vibrant color schemes and richly-detailed animation blotted-out the Allen images of dark tunnels and rigid earth-toned uniformity that were more-suited to Allen’s dark tale of militarism and societal conformity, and immersed us in a counter-world which, while fraught with danger and peril, still had a charm and appeal that we might want to visit, leading to a California Adventure “land” that continues to endure as a crowd-pleaser to the present day.

All is not happiness on the “island” an ant colony calls its home. (While referred to as an island, the small area of green field and trees seems to be surrounded not by water, but mostly by canyons apparently formed by a now-dry river bed, floored with parched, cracked earth.) Approaching the end of spring, the ants busy themselves in intense labor, piling small bits of food upon a large leaf upon a rock, as an “offering” to their annual visitors and nemeses – the grasshoppers. The arrangement is that the ants must supply the grasshoppers with an annual feast to gorge themselves upon in the course of their yearly migration, and then are left alone for the remainder of the year, during which time the ants redouble their efforts to round up what food is left on the island to see the colony through the winter. No one wants to know the consequences should they refuse to provide the offering, as the aggressive grasshoppers measure about four times their size.

The Queen of the colony is getting along in years, and has two offspring in line for succession to the throne. The elder princess is in training, and this marks her first year supervising the foraging for the offering. She is in a dither over the details, and worried that she will crack under the pressure, though the Queen reassures her that she is doing just fine. The youngest princess (Dot) is a juvenile, and still struggles to master the power of her budding wings, though the Queen says she should wait until they develop to attempt flight. Among the worker ants is one who strays from the norm, a self-styled inventor named Flik. He nearly pummels the elder princess when his latest invention, a plant-built miniature power saw, topples whole stalks like tree trunks, narrowly missing the princess. He is still wearing the apparatus when the blowing of ant-fashioned horns signals the approach of the flight of grasshoppers. All ants are ordered to place their last bits of food into the offering, then race in single-file to the safety of the ant tunnels below ground. Flik is the last in line, and, still wearing his cumbersome device, accidentally topples a twig supporting the offering leaf. The leaf slides from the rock, one end dipping to allow all the food to roll off a ledge, where it lands in the depths of a small pool of water ay one end of the river bed, out of reach of the insects. Flik races down into the ant hill, and nervously tries to approach the princess to explain what has happened – but never gets the chance, as explanation comes from a more frightening source. The buzz of the wings of the grasshopper horde stops above, then, after a few yells and a short silence, the giant feet of the grasshoppers begin to stomp holes in the sandy soil above, as the grasshoppers invade the ant tunnels. Their leader, Hopper, confronts the Queen and princess. “Where is it?”. he demands. “Isn’t it up there?” asks the princess nervously. “Do I look stupid? Would I be lowering muself to your level it if was up there?” shouts Hopper. Hopper reminds all of the arrangement, and that without food, the colony’s safety cannot be guaranteed, displaying a mad, ravenous grasshopper who seems ready to devour anything in its path. Flik attempts to stand up for the princess, telling Hopper to leave her alone. But Hopper quickly intimidates Flik with his size, and orders the upstart to get back in line. Hopper delivers a generous ultimatum – double the order for the food by the end of the summer, at which time the grasshoppers will return. The Queen and princess point out this will leave no time for the colony to forage for their own winter food supply, but receive no reprieve from Hopper’s order.

The Queen of the colony is getting along in years, and has two offspring in line for succession to the throne. The elder princess is in training, and this marks her first year supervising the foraging for the offering. She is in a dither over the details, and worried that she will crack under the pressure, though the Queen reassures her that she is doing just fine. The youngest princess (Dot) is a juvenile, and still struggles to master the power of her budding wings, though the Queen says she should wait until they develop to attempt flight. Among the worker ants is one who strays from the norm, a self-styled inventor named Flik. He nearly pummels the elder princess when his latest invention, a plant-built miniature power saw, topples whole stalks like tree trunks, narrowly missing the princess. He is still wearing the apparatus when the blowing of ant-fashioned horns signals the approach of the flight of grasshoppers. All ants are ordered to place their last bits of food into the offering, then race in single-file to the safety of the ant tunnels below ground. Flik is the last in line, and, still wearing his cumbersome device, accidentally topples a twig supporting the offering leaf. The leaf slides from the rock, one end dipping to allow all the food to roll off a ledge, where it lands in the depths of a small pool of water ay one end of the river bed, out of reach of the insects. Flik races down into the ant hill, and nervously tries to approach the princess to explain what has happened – but never gets the chance, as explanation comes from a more frightening source. The buzz of the wings of the grasshopper horde stops above, then, after a few yells and a short silence, the giant feet of the grasshoppers begin to stomp holes in the sandy soil above, as the grasshoppers invade the ant tunnels. Their leader, Hopper, confronts the Queen and princess. “Where is it?”. he demands. “Isn’t it up there?” asks the princess nervously. “Do I look stupid? Would I be lowering muself to your level it if was up there?” shouts Hopper. Hopper reminds all of the arrangement, and that without food, the colony’s safety cannot be guaranteed, displaying a mad, ravenous grasshopper who seems ready to devour anything in its path. Flik attempts to stand up for the princess, telling Hopper to leave her alone. But Hopper quickly intimidates Flik with his size, and orders the upstart to get back in line. Hopper delivers a generous ultimatum – double the order for the food by the end of the summer, at which time the grasshoppers will return. The Queen and princess point out this will leave no time for the colony to forage for their own winter food supply, but receive no reprieve from Hopper’s order.

As the grasshoppers leave, it becomes apparent that Flik was the cause of the disaster. Realizing the hopelessness of meeting the grasshoppers’ demands, Flik arrives at the idea that what they need is bigger bugs from off the island to fight and scare the grasshoppers away. The royal council deems such a mission suicide – but then huddles, realizing this might be the perfect excuse to get Flik out of the way and prevent his ability to cause further trouble. Flik is sent alone on his mission, the cheers of the ant crowd only being heard by Flik after he is in a position out of sight of them over a hill. Flik plucks a dandelion seed stem, and floats over the dry river bed on the breeze, seeking out “the big city” and the likelihood of finding rough, tough warriors there.