Quite a bit of ground to cover today, as we deal with the last gasps of the theatrical short, then move on to big top action from the screwball television world of Jay Ward.

Seal on the Loose (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 1/26/70 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – As all followers of Lantz’s product know, Woody Woodpecker by this time had long before seen better days. With budgets ever-dwindling, and only one director left to helm all studio productions, creativity was at a minimum, art “quality” was down, color choices were restricted by the price of paints, and most films had a feeling of assembly-line mass production, with much of the nuts and bolts comprised of moving from one stock pose to another lifted from prior productions. Gone were the days of seeing unique off-model action, shock-takes, etc. – you feel like you’ve seen nearly every drawing many times before. Once in a blue moon, however, what little writing staff was left might drop in a verbal zinger that harkened back to Woody’s old days of wise cracks, which seem to provide the only life left in these late, tired episodes. This one, in all fairness, is a miniscule bit better than the average of its time, though it feels like it lacks any real ending.

Seal on the Loose (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 1/26/70 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – As all followers of Lantz’s product know, Woody Woodpecker by this time had long before seen better days. With budgets ever-dwindling, and only one director left to helm all studio productions, creativity was at a minimum, art “quality” was down, color choices were restricted by the price of paints, and most films had a feeling of assembly-line mass production, with much of the nuts and bolts comprised of moving from one stock pose to another lifted from prior productions. Gone were the days of seeing unique off-model action, shock-takes, etc. – you feel like you’ve seen nearly every drawing many times before. Once in a blue moon, however, what little writing staff was left might drop in a verbal zinger that harkened back to Woody’s old days of wise cracks, which seem to provide the only life left in these late, tired episodes. This one, in all fairness, is a miniscule bit better than the average of its time, though it feels like it lacks any real ending.

Woody is living at Mrs. Meny’s boarding house, where a strict “No Pets” rule is in effect. Woody is in Dutch with her for trying to test the limits of the rule, having brought home a small bowl of harmless goldfish. Meany orders him to dispose of the “troublesome creatures”, complaining out the window as Woody leaves, bowl in hand, that she is not running a pet shop. “Well, it looks like one with an old crow in the window”, Woody quips in one of the few clever lines of the script. He takes his fish to a park pond to dump them in, bit is stopped by a park cop. who thinks he is taking fish out. The cop empties the bowl himself into the pond, then slams the inverted bowl upon Woody’s head like a space helmet. “My mama said there’d be days like this”, remarks Woody as he trudges home. But before Woody can get back, a large truck passes from the Bungling Brothers Circus, and a crate falls out the rear end, unnoticed by the driver. Out of same pops a seal. The seal gives Woody some playful slaps across the face, while Woody unsuccessfully attempts to hail the disappearing truck driver. “Now what am I gonna do with you?”. Woody asks. The seal has his own ideas of what’s next, spotting the open rear door of a fish monger’s truck. Darting inside, the seal quickly begins to consume the owner’s product. Woody steps inside in attempt to get the seal out of there, but is spotted by the monger. Assuming Woody is the one who let his seal devour his wares, the monger demands ten bucks. “I haven’t got ten cents”, pleads Woody to the unsympathetic merchant. Woody is booted out of the van, the monger next vowing to get the seal too. The seal, however, wins the subsequent bout, bopping the monger over the head with his largest catch of the day.

Woody is living at Mrs. Meny’s boarding house, where a strict “No Pets” rule is in effect. Woody is in Dutch with her for trying to test the limits of the rule, having brought home a small bowl of harmless goldfish. Meany orders him to dispose of the “troublesome creatures”, complaining out the window as Woody leaves, bowl in hand, that she is not running a pet shop. “Well, it looks like one with an old crow in the window”, Woody quips in one of the few clever lines of the script. He takes his fish to a park pond to dump them in, bit is stopped by a park cop. who thinks he is taking fish out. The cop empties the bowl himself into the pond, then slams the inverted bowl upon Woody’s head like a space helmet. “My mama said there’d be days like this”, remarks Woody as he trudges home. But before Woody can get back, a large truck passes from the Bungling Brothers Circus, and a crate falls out the rear end, unnoticed by the driver. Out of same pops a seal. The seal gives Woody some playful slaps across the face, while Woody unsuccessfully attempts to hail the disappearing truck driver. “Now what am I gonna do with you?”. Woody asks. The seal has his own ideas of what’s next, spotting the open rear door of a fish monger’s truck. Darting inside, the seal quickly begins to consume the owner’s product. Woody steps inside in attempt to get the seal out of there, but is spotted by the monger. Assuming Woody is the one who let his seal devour his wares, the monger demands ten bucks. “I haven’t got ten cents”, pleads Woody to the unsympathetic merchant. Woody is booted out of the van, the monger next vowing to get the seal too. The seal, however, wins the subsequent bout, bopping the monger over the head with his largest catch of the day.

Woody is already walking home, just glad to be rid of the little troublemaker, but finds the seal following right behind. Despite Meany’s rules, Woody consents to take the seal home, until he can find who it belongs to. To get him past Meany, Woody borrows some baby clothes from a neighbor’s clothesline, dressing the seal with them. The two attempt to sneak inside, but the seal spots a trumpet left lying upon a table in the entrance room, and can’t resist the habits of his circus act to blow a tune upon it. Meany is aroused, and asks who the newcomer is. Woody at first blurts out the word “seal”, but covers by changing it to “Lucielle” (predicting in advance the play-on-words that would becoe the name of the San Francisco Giants’ mascot), convincing Meany he is baby-sitting. “What a cute baby”, remarks Meany, until she receives a slapping across the face by the seal’s flippers, leaving her temporarily dazed. Woody leaves the seal in his upstairs room, while stepping out to scout up some fish. The seal spots an appealing bathtub in the adjoining room, and quickly abandons his baby costume, filling the tub with running water and a full box of sudsy soap, then dives in to splash vigorously about. Drops of water begin to fall on Meany below, as the tub overflows. She races upstairs, and, thinking the baby is among the suds, dives into the tub. The secret is out, and the seal gets away while Meany slips inside the tub. Woody returns with a fish, and Meany lures him to her with a call of “Arf arf”. Woody tosses the fish into the suds, but Meany rises from the tub to slap him silly with the mackerel. A chase follows, sequences of which include: (1) the three getting tangled up in various positions of compression in a convertible sofa-bed; (2) Woody ducking inside a suitcase, with Meany stomping on it, only to be met by Woody who is already outside, and joins in the “fun” by stomping on the suitcase too, while Meany cruelly encourages him, “Harder, harder!”; (3) a prolonged rehash of the old “six-door chase”, a gag situation seen as early as Oswald Rabbit’s The Birthday Party and commonly used by Tex Avery, with characters passing back and forth on various modes of transportation (unicycle, motorcycle, balancing on a ball), and Meany at one point running into herself. The seal finally swats Meany in the rear, knocking her into the sofa-bed once again. The film abruptly ends, as Woody and the seal merely depart, the seal blowing his own fanfare upon the trumpet.

Woody is already walking home, just glad to be rid of the little troublemaker, but finds the seal following right behind. Despite Meany’s rules, Woody consents to take the seal home, until he can find who it belongs to. To get him past Meany, Woody borrows some baby clothes from a neighbor’s clothesline, dressing the seal with them. The two attempt to sneak inside, but the seal spots a trumpet left lying upon a table in the entrance room, and can’t resist the habits of his circus act to blow a tune upon it. Meany is aroused, and asks who the newcomer is. Woody at first blurts out the word “seal”, but covers by changing it to “Lucielle” (predicting in advance the play-on-words that would becoe the name of the San Francisco Giants’ mascot), convincing Meany he is baby-sitting. “What a cute baby”, remarks Meany, until she receives a slapping across the face by the seal’s flippers, leaving her temporarily dazed. Woody leaves the seal in his upstairs room, while stepping out to scout up some fish. The seal spots an appealing bathtub in the adjoining room, and quickly abandons his baby costume, filling the tub with running water and a full box of sudsy soap, then dives in to splash vigorously about. Drops of water begin to fall on Meany below, as the tub overflows. She races upstairs, and, thinking the baby is among the suds, dives into the tub. The secret is out, and the seal gets away while Meany slips inside the tub. Woody returns with a fish, and Meany lures him to her with a call of “Arf arf”. Woody tosses the fish into the suds, but Meany rises from the tub to slap him silly with the mackerel. A chase follows, sequences of which include: (1) the three getting tangled up in various positions of compression in a convertible sofa-bed; (2) Woody ducking inside a suitcase, with Meany stomping on it, only to be met by Woody who is already outside, and joins in the “fun” by stomping on the suitcase too, while Meany cruelly encourages him, “Harder, harder!”; (3) a prolonged rehash of the old “six-door chase”, a gag situation seen as early as Oswald Rabbit’s The Birthday Party and commonly used by Tex Avery, with characters passing back and forth on various modes of transportation (unicycle, motorcycle, balancing on a ball), and Meany at one point running into herself. The seal finally swats Meany in the rear, knocking her into the sofa-bed once again. The film abruptly ends, as Woody and the seal merely depart, the seal blowing his own fanfare upon the trumpet.

Unavailable for viewing, with no synopsis available, are two episodes of Terrytoons’ “Astronut” series, likely produced for television, which may have received theatrical release in the 1970’s – “Scientific Sideshow”, and “Going Ape”. I do not recall these films receiving any resyndication, and have never seen them. Thus, it is unknown if these titles suggest a circus connection, and anyone with information on these films is invited to contribute.

Unavailable for viewing, with no synopsis available, are two episodes of Terrytoons’ “Astronut” series, likely produced for television, which may have received theatrical release in the 1970’s – “Scientific Sideshow”, and “Going Ape”. I do not recall these films receiving any resyndication, and have never seen them. Thus, it is unknown if these titles suggest a circus connection, and anyone with information on these films is invited to contribute.

Fast forward several years, and Pixar contributes two circus-themes shorts during its formative years. Red’s Dream (7/10/87) is a somewhat moody piece, set in a bicycle shop after hours on a rainy night. Tucked away in a corner of the shop, leaning against a wall, is a single red unicycle. As the camera closes in, we cross-dissolve to discover that the unicycle has a life of its own, and is dreaming of what it wishes it could experience. We are transported to the center ring of a circus, in a darkened tent lit only by spotlight upon the performer.

To a trumpet fanfare, a clown enters the ring, riding the unicycle. (A nice comic touch appears on soundtrack, as, after the majestic fanfare, we hear only the meager applause of what is probably two sets of hands.) The clown begins a rather mediocre juggling act, circling around on the unicycle as he juggles three balls. He is not entirely proficient, as one ball falls out of his grip, takes a bounce off the ground, then returns to his moving hands. Another ball fumble causes an unexpected reaction, as “Red” the unicycle slips out from under the clown, leaving him defying gravity and pedaling in md-air, while Red catches the fallen ball on one of his pedals, and begins bouncing it up and down by rolling himself back and forth repeatedly, The clown continues to circle the ring, floating in air as if nothing has happened, until he looks down for the fallen ball, and spots Red. First law of cartoon physics goes into effect, and, having discovered himself floating in air, the clown falls, losing his hold on the two other balls in the process. Red catches the balls on his other foot pedal, and begins to juggle all three balls, with movements of both his pedals and his handlebar. He ends the performance by catching all three balls on one pedal, balanced atop each other. Now, we hear cheers and applause as is from a full house, and Red bends from his center pole and swivels his seat as if taking bows to the audience. The scene cross-dissolves back to the bicycle shop, where we find Red taking bows only to the immobile bicycles in the racks on either side of him, and slowing to a stop, as realization sets in that it was only a dream. Bowing his seat in a posture of forlorn dejection, Red slowly rolls back to his corner, straightening out to resume his lean against the wall, left to wait until the next morning, in hopes that someone will really purchase him.

To a trumpet fanfare, a clown enters the ring, riding the unicycle. (A nice comic touch appears on soundtrack, as, after the majestic fanfare, we hear only the meager applause of what is probably two sets of hands.) The clown begins a rather mediocre juggling act, circling around on the unicycle as he juggles three balls. He is not entirely proficient, as one ball falls out of his grip, takes a bounce off the ground, then returns to his moving hands. Another ball fumble causes an unexpected reaction, as “Red” the unicycle slips out from under the clown, leaving him defying gravity and pedaling in md-air, while Red catches the fallen ball on one of his pedals, and begins bouncing it up and down by rolling himself back and forth repeatedly, The clown continues to circle the ring, floating in air as if nothing has happened, until he looks down for the fallen ball, and spots Red. First law of cartoon physics goes into effect, and, having discovered himself floating in air, the clown falls, losing his hold on the two other balls in the process. Red catches the balls on his other foot pedal, and begins to juggle all three balls, with movements of both his pedals and his handlebar. He ends the performance by catching all three balls on one pedal, balanced atop each other. Now, we hear cheers and applause as is from a full house, and Red bends from his center pole and swivels his seat as if taking bows to the audience. The scene cross-dissolves back to the bicycle shop, where we find Red taking bows only to the immobile bicycles in the racks on either side of him, and slowing to a stop, as realization sets in that it was only a dream. Bowing his seat in a posture of forlorn dejection, Red slowly rolls back to his corner, straightening out to resume his lean against the wall, left to wait until the next morning, in hopes that someone will really purchase him.

Tin Toy (8/2/88) was the short that really put Pixar on the map, gleaning the studio its first Oscar, and in many ways setting the blueprint for what would become their first successful franchise, the Toy Story series. To the opening strains of “Puffin’ Billy”, a melody recorded by the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra in England for the Chappell records music library, which became a standard to nearly every American child when the tune was adopted as the theme song for Bob Keeshan’s Captain Kangaroo on CBS, our film opens in a typical American home, focused on the floor of a child’s playroom, where a paper shopping bag and an opened cardboard box with cellophane panels gives indication that a new toy has just been purchased and added to the collection. While we hear soundtrack snippets from a TV set in the next room of various Hanna-Barbera and Walter Lantz cartoons, and even the voice of the host of “The Price Is Right”, the camera pans from the box marked “Tin Toy”, to the article formerly housed within it – a colorful mechanical human-like figure, dressed as a circus bandmaster, decked out for participation in a parade, with a large bass drum strapped to his back that beats out a rhythm automatically with every step, cymbals connected atop the drum, a xylophone or glockenspiel and a small trumpet strapped on one side of the drum and manipulated somehow by the little man’s movements to play excerpts from famous march melodies, and an accordion strapped between his hands for further melodic accompaniment. The little bandmaster, alone for the moment, slowly turns his head to take in the layout of the room in which he has been placed, smiling approvingly. A sound outside the doorway signals the arrival of the room’s principal occupant, which attracts the toy’s eager stares to see who he belongs to. Enter an infant toddler, unclothed except for a diaper considerably too big for him, babbling and crawling on all fours. The toy’s face registers an emotion of “How adorable” – that is, until the toy gets a better idea of the kid’s standards of activity for playtime. Plopping down into a seated position on the floor, the tyke waves his hands around randomly, then reaches for the topmost of a stack of plastic rings of different colors, stacked in progressively larger sizes upon a wooden pole base.

Tin Toy (8/2/88) was the short that really put Pixar on the map, gleaning the studio its first Oscar, and in many ways setting the blueprint for what would become their first successful franchise, the Toy Story series. To the opening strains of “Puffin’ Billy”, a melody recorded by the Queen’s Hall Light Orchestra in England for the Chappell records music library, which became a standard to nearly every American child when the tune was adopted as the theme song for Bob Keeshan’s Captain Kangaroo on CBS, our film opens in a typical American home, focused on the floor of a child’s playroom, where a paper shopping bag and an opened cardboard box with cellophane panels gives indication that a new toy has just been purchased and added to the collection. While we hear soundtrack snippets from a TV set in the next room of various Hanna-Barbera and Walter Lantz cartoons, and even the voice of the host of “The Price Is Right”, the camera pans from the box marked “Tin Toy”, to the article formerly housed within it – a colorful mechanical human-like figure, dressed as a circus bandmaster, decked out for participation in a parade, with a large bass drum strapped to his back that beats out a rhythm automatically with every step, cymbals connected atop the drum, a xylophone or glockenspiel and a small trumpet strapped on one side of the drum and manipulated somehow by the little man’s movements to play excerpts from famous march melodies, and an accordion strapped between his hands for further melodic accompaniment. The little bandmaster, alone for the moment, slowly turns his head to take in the layout of the room in which he has been placed, smiling approvingly. A sound outside the doorway signals the arrival of the room’s principal occupant, which attracts the toy’s eager stares to see who he belongs to. Enter an infant toddler, unclothed except for a diaper considerably too big for him, babbling and crawling on all fours. The toy’s face registers an emotion of “How adorable” – that is, until the toy gets a better idea of the kid’s standards of activity for playtime. Plopping down into a seated position on the floor, the tyke waves his hands around randomly, then reaches for the topmost of a stack of plastic rings of different colors, stacked in progressively larger sizes upon a wooden pole base.

The tin toy is taken aback, and his countenance registers mild shock mixed with a twinge of revulsion, as the child takes the ring into his mouth, attempts to bite it, then drools all over it. Next the child grabs a string of oversized multicolor beads tied together into a loop, shakes the beads violently, then smashes the loop upon the floor, breaking the string within, and sending beads bouncing and rolling everyplace. The tin toy winces and attempts to duck out of the way as several of the beads pass around and over him. For good measure, the child sneezes, then finally casts his eyes on the little bandmaster. With trepidation as to what might come next, the little toy begins to slowly back away – with an unexpected result, as the little man forgets that every move he makes results in a drum beat or some instrument being played, which only serves to call further attention to himself. The child begins to make playful gurgling sounds, his attention now riveted upon the toy at the sound of the music. There is nothing for the toy to do but to make a run for it, which he does. The fevered music heard from his instruments as he runs seems to merely excite the child all the more, as he props himself up to waddle forward as a toddler will in a wobbly but determined walk to catch the toy. The toy almost reaches the far end of the room, but forgets another mechanism built within him – a direction-changer, that will cause him after so many steps to twirl around in circles a few times, then set out in a new direction. He finds himself heading straight back toward the child, and it takes all his resolve to put himself into another spin just short of the child’s reach, to shift his progress into another direction. This time, as the child closes in, the toy encounters an obstacle, as the little bandmaster runs right into the open flap of the cardboard box in which he was originally packaged, his forward progress stopped cold by the closed flap of the box’s other side. The child draws ever nearer, but the toy puts himself and the box into another reversal-spin move, and he somehow emerges from the box, making a desperate dart right between the child’s legs. The move works, and the toy passes the infant, and finally reaches a point of temporary safety, underneath an easy chair. In the darkness below such furnishing, the panting bandmaster makes a surprising discovery. Seemingly all the toys in the child’s collection who have the power of mobility have also taken refuge under the same chair, many of them still trembling with fear at the approach of their owner just outside the shadows.

The tin toy is taken aback, and his countenance registers mild shock mixed with a twinge of revulsion, as the child takes the ring into his mouth, attempts to bite it, then drools all over it. Next the child grabs a string of oversized multicolor beads tied together into a loop, shakes the beads violently, then smashes the loop upon the floor, breaking the string within, and sending beads bouncing and rolling everyplace. The tin toy winces and attempts to duck out of the way as several of the beads pass around and over him. For good measure, the child sneezes, then finally casts his eyes on the little bandmaster. With trepidation as to what might come next, the little toy begins to slowly back away – with an unexpected result, as the little man forgets that every move he makes results in a drum beat or some instrument being played, which only serves to call further attention to himself. The child begins to make playful gurgling sounds, his attention now riveted upon the toy at the sound of the music. There is nothing for the toy to do but to make a run for it, which he does. The fevered music heard from his instruments as he runs seems to merely excite the child all the more, as he props himself up to waddle forward as a toddler will in a wobbly but determined walk to catch the toy. The toy almost reaches the far end of the room, but forgets another mechanism built within him – a direction-changer, that will cause him after so many steps to twirl around in circles a few times, then set out in a new direction. He finds himself heading straight back toward the child, and it takes all his resolve to put himself into another spin just short of the child’s reach, to shift his progress into another direction. This time, as the child closes in, the toy encounters an obstacle, as the little bandmaster runs right into the open flap of the cardboard box in which he was originally packaged, his forward progress stopped cold by the closed flap of the box’s other side. The child draws ever nearer, but the toy puts himself and the box into another reversal-spin move, and he somehow emerges from the box, making a desperate dart right between the child’s legs. The move works, and the toy passes the infant, and finally reaches a point of temporary safety, underneath an easy chair. In the darkness below such furnishing, the panting bandmaster makes a surprising discovery. Seemingly all the toys in the child’s collection who have the power of mobility have also taken refuge under the same chair, many of them still trembling with fear at the approach of their owner just outside the shadows.

The tin toy remains motionless so as not to allow any of his instruments to play, as the child waddles close to the chair. Suddenly, the child takes a misstep, trips, and falls on his stomach, He pauses for a brief moment of surprised silence, then bursts out with a crying jag. The crying continues, as the other toys continue to shiver in the shadows, as far away from the infant as they can get. But the tin toy is moved to sympathetic affection by the child’s cries and tears, and his face registers an need inside himself to somehow help. A slight shift in position causes a couple of notes to be heard from his instruments, and suddenly, the toy’s face brightens to a wide smile. With confidence building, the little man reaches the realization that a toy is meant to be played with to make a child happy – and the further reality that there comes a time when a toy’s gotta do what a toy’s gotta do. To the amazement of the others under the chair, the tin toy slowly advances forward, beginning his melodies from all of his instruments, and emerges into the light from under the chair. Bravely, he parades and twirls close to the child, until the infant’s wailing stops, and the child takes notice. The toy finally finds himself grabbed up in the child’s hand, where he is given a bit of vigorous shaking, then dropped on the floor, but fortunately from not too high a height, and double-fortunately landing on his feet. Nothing breaks, but the little toy is briefly unnerved to the point of trembling and hiding his face behind his accordion bellows. As the brief shock of the ordeal subsides, the toy dares to take a glimpse past the accordion to see what the child will do next. To his surprise, the child no longer seems to be taking any notice of him. Instead, the infant has discovered something more interesting – the cardboard box from the toy’s packaging, which the toddler does his best to force his nose inside. This behavior the toy cannot understand at all, as he rolls a few times to nudge the child’s foot, as if to signal him, “Hey, I’m down here.” To the toy’s greater frustration, the child abandons the box for the even greater satisfaction of pulling the empty shopping bag completely down over his head, then waddling all over the house with his head covered, unable to see a thing. The little toy, now on a new mission to prove that he is the plaything, not the packaging, continues to follow the child everywhere, playing its music as loud as it possibly can, while the happy infant continues to roam aimlessly, and the credits begin to roll. A masterpiece of mini-storytelling, setting the mood for the CGI dynasty that was soon to emerge.

The tin toy remains motionless so as not to allow any of his instruments to play, as the child waddles close to the chair. Suddenly, the child takes a misstep, trips, and falls on his stomach, He pauses for a brief moment of surprised silence, then bursts out with a crying jag. The crying continues, as the other toys continue to shiver in the shadows, as far away from the infant as they can get. But the tin toy is moved to sympathetic affection by the child’s cries and tears, and his face registers an need inside himself to somehow help. A slight shift in position causes a couple of notes to be heard from his instruments, and suddenly, the toy’s face brightens to a wide smile. With confidence building, the little man reaches the realization that a toy is meant to be played with to make a child happy – and the further reality that there comes a time when a toy’s gotta do what a toy’s gotta do. To the amazement of the others under the chair, the tin toy slowly advances forward, beginning his melodies from all of his instruments, and emerges into the light from under the chair. Bravely, he parades and twirls close to the child, until the infant’s wailing stops, and the child takes notice. The toy finally finds himself grabbed up in the child’s hand, where he is given a bit of vigorous shaking, then dropped on the floor, but fortunately from not too high a height, and double-fortunately landing on his feet. Nothing breaks, but the little toy is briefly unnerved to the point of trembling and hiding his face behind his accordion bellows. As the brief shock of the ordeal subsides, the toy dares to take a glimpse past the accordion to see what the child will do next. To his surprise, the child no longer seems to be taking any notice of him. Instead, the infant has discovered something more interesting – the cardboard box from the toy’s packaging, which the toddler does his best to force his nose inside. This behavior the toy cannot understand at all, as he rolls a few times to nudge the child’s foot, as if to signal him, “Hey, I’m down here.” To the toy’s greater frustration, the child abandons the box for the even greater satisfaction of pulling the empty shopping bag completely down over his head, then waddling all over the house with his head covered, unable to see a thing. The little toy, now on a new mission to prove that he is the plaything, not the packaging, continues to follow the child everywhere, playing its music as loud as it possibly can, while the happy infant continues to roam aimlessly, and the credits begin to roll. A masterpiece of mini-storytelling, setting the mood for the CGI dynasty that was soon to emerge.

We shift our attention now to television, not necessarily attacking the medium in chronological order, but selecting a random producer’s output that happens to fit this article length. Out subject today is the work of Jay Ward. Ward’s influence was felt on TV years before the opening of his own studio, beginning with his association with Jerry Fairbanks’ productions on television’s first “animated” series hit, Crusader Rabbit. (“Animated” is in quotes, as at this stage of shoestring budgets, most of the film is nothing more than the filming of storyboard stills.) The very first installment of the very first story arc of such show has a circus connection. In Chapter 1 of Crusader Rabbit vs. the State of Texas, (1949), we are introduced to the diminutive bunny with the heart of a knight-errant from Galahad Glen. Despite having no special powers except the ability to run fast when faced with danger, Crusader’s fur bristles when he hears a radio news item about all Jack rabbits being driven out of the State of Texas. That’s his relatives they’re talking about – even if their closest relation is a 32nd cousin. Crusader declares a one-rabbit war upon the entire state. He is not worried about meeting the Texans themselves, whom he assumes should be easy to defeat – after all, they’re all singers. But those horses – they might require some extra muscle. So he looks for a strong companion to join him. As luck would have it, he is passing a circus grounds. A cage in the menagerie is attracting attention – that of the Man-Eating Tiger, from which terrifying roars are heard, leaving the crowd outside cowering in fear. Crusader cautiously approaches the cage, and peers in. Inside sits the large but friendly-faced Ragland T. Tiger (Rags for short), smiling at the spectators as he plays a sound-effects record on an old gramophone, from which all the roars are produced. At the conclusion of the record, Rags announces, “Duh, this has been a transcribed program.” Just the sort of companion Crusader needs – make that, rates. For more, catch the entire story arc, available online in many chapters.

We shift our attention now to television, not necessarily attacking the medium in chronological order, but selecting a random producer’s output that happens to fit this article length. Out subject today is the work of Jay Ward. Ward’s influence was felt on TV years before the opening of his own studio, beginning with his association with Jerry Fairbanks’ productions on television’s first “animated” series hit, Crusader Rabbit. (“Animated” is in quotes, as at this stage of shoestring budgets, most of the film is nothing more than the filming of storyboard stills.) The very first installment of the very first story arc of such show has a circus connection. In Chapter 1 of Crusader Rabbit vs. the State of Texas, (1949), we are introduced to the diminutive bunny with the heart of a knight-errant from Galahad Glen. Despite having no special powers except the ability to run fast when faced with danger, Crusader’s fur bristles when he hears a radio news item about all Jack rabbits being driven out of the State of Texas. That’s his relatives they’re talking about – even if their closest relation is a 32nd cousin. Crusader declares a one-rabbit war upon the entire state. He is not worried about meeting the Texans themselves, whom he assumes should be easy to defeat – after all, they’re all singers. But those horses – they might require some extra muscle. So he looks for a strong companion to join him. As luck would have it, he is passing a circus grounds. A cage in the menagerie is attracting attention – that of the Man-Eating Tiger, from which terrifying roars are heard, leaving the crowd outside cowering in fear. Crusader cautiously approaches the cage, and peers in. Inside sits the large but friendly-faced Ragland T. Tiger (Rags for short), smiling at the spectators as he plays a sound-effects record on an old gramophone, from which all the roars are produced. At the conclusion of the record, Rags announces, “Duh, this has been a transcribed program.” Just the sort of companion Crusader needs – make that, rates. For more, catch the entire story arc, available online in many chapters.

Regrettably unavailable, either in chapters or its entirety, is another early Crusader story arc, “Crusader and the Circus”, for which not even a synopsis is available. It is a pity that these early Fairbanks serials have bever been fully compiled and restored in any video format, excepting the first two which were issued complete many years ago by Rhino video. They are considerably more entertaining than their limited animation would suggest, and, particularly in story arc 2, begin to show recognizable trademark storytelling styles of Ward that would frequent his later series such as “Rocky and His Friends” and “Hoppity Hooper”. This looks like a job for Thunderbean Animation (??????)

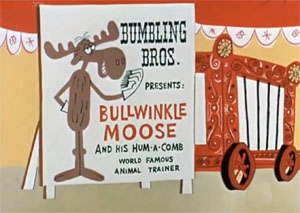

Speaking of Rocky and Bullwinkle, we move directly into such later productions, which made Ward’s name a household word. It would be interesting to see if there are similarities between the missing Crusader story referenced above and Bumbling Brothers Circus (Season 5, “The Bullwinkle Show”, NBC 1963) – A typically rambling narrrative (perhaps more so than usual) is presented, sufficient to get the program through several weeks of broadcasting. While engaged in a Frostbite Falls checker championship, Bullwinkle’s winning game is interrupted by the news that a circus is pulling into town. Bullwinkle’s opponent abandons the game to see the show, and the angry moose storms off to give the circus owner a piece of his mind. Rocky comments that that’s what he likes about Bullwinkle – no matter how little of something he’s got, he’s willing to share. At the circus grounds, Rocky notices a poster for the circus’s lion tamer, Claude Badley (play on the name of Clyde Beatty, one of the most famous of circus animal trainers, and the head of his own circus for many years). Rocky comments that the face seems familiar, and Bullwinkle points out that this is a switch from the usual “That voice. Haven’t I heard it somewhere before?” Bullwinkle has a confusing confrontation as he attempts to vent his complaint to the “owner”, who instead turns out to be a pair of twin brothers, Hugo and Igo Bumbling. Each appears one at a time, the first anxious to pacify Bullwinkle with free tickets, while the second (who turns up at alternating intervals) thinks Bullwinkle is a chisler after free tickets, and calls him a mooching moose. When Rocky finally clears up the confusion, both of our heroes are admitted free to see the show. Meanwhile, Claude Badley turns out to be none other than Boris Badenov, who, seemingly just for fun, is acting as a lion un-tamer, taunting one lion, by making ugly faces, into a state of ferocity, which Boris describes as not only making him man-eating, but moose-eating. At the evening performance (presented with all three rings placed concentrically one inside the other, as this is a low-budget circus), Boris remains safe in his own act, using lions so old their bones creak, and whose teeth are false and removable before the performance. The one infuriated man-eater remains in his own cage adjoining the circular enclosure in which Boris performs, until Natasha is given the signal to open his cage door and release him. Instead of releasing the fierce lion into Boris’s enclosure, the cage of the beast has been rolled in backwards, and opens outward toward the crowd. Panic ensues, and Rocky and Bullwinkle, being heroes, are required by definition to stay rather than flee, to try to resolve the situation. Rocky does some fancy flying near the lion’s nose, to distract him long enough for the crowd to escape, while Bullwinkle creeps up upon the lion with a net. True to form (though the narrator has to cue the disbelieving moose into his own bungle), Bullwinkle trips and falls into his own net. Rocky, now distracted himself, is swatted out of the air by the lion’s paw, and pinned upon the ground in the lion’s grip. Bullwinkle somehow gets free of the net, and tries every diversion in the book (tap-dancing, juggling, etc.), with no effect upon the lion, until the moose is reduced to use his last two remaining belongings – a sheet of tissue paper and a comb. Humming into them like a kazoo, Bullwinkle finds music charms the savage beast, and Rocky is released. The lion still advances on Bullwinkle, but as the moose changes tunes to a lullaby, the king of beasts rolls over on his back, and falls fast asleep like a harmless kitten. Despite Boris’s blatant act of sabotage in releasing the lion upon the crowd, the Bumbling Brothers are reluctant to do anything against him, noting that every circus must have a lion tamer, so Boris has them over a barrel. But Rocky thinks otherwise, volunteering Bullwinkle’s services as new lion tamer. Boris finds himself out on his ear, and swears (literally in Pottsylvanian) to have his revenge on the show.

Speaking of Rocky and Bullwinkle, we move directly into such later productions, which made Ward’s name a household word. It would be interesting to see if there are similarities between the missing Crusader story referenced above and Bumbling Brothers Circus (Season 5, “The Bullwinkle Show”, NBC 1963) – A typically rambling narrrative (perhaps more so than usual) is presented, sufficient to get the program through several weeks of broadcasting. While engaged in a Frostbite Falls checker championship, Bullwinkle’s winning game is interrupted by the news that a circus is pulling into town. Bullwinkle’s opponent abandons the game to see the show, and the angry moose storms off to give the circus owner a piece of his mind. Rocky comments that that’s what he likes about Bullwinkle – no matter how little of something he’s got, he’s willing to share. At the circus grounds, Rocky notices a poster for the circus’s lion tamer, Claude Badley (play on the name of Clyde Beatty, one of the most famous of circus animal trainers, and the head of his own circus for many years). Rocky comments that the face seems familiar, and Bullwinkle points out that this is a switch from the usual “That voice. Haven’t I heard it somewhere before?” Bullwinkle has a confusing confrontation as he attempts to vent his complaint to the “owner”, who instead turns out to be a pair of twin brothers, Hugo and Igo Bumbling. Each appears one at a time, the first anxious to pacify Bullwinkle with free tickets, while the second (who turns up at alternating intervals) thinks Bullwinkle is a chisler after free tickets, and calls him a mooching moose. When Rocky finally clears up the confusion, both of our heroes are admitted free to see the show. Meanwhile, Claude Badley turns out to be none other than Boris Badenov, who, seemingly just for fun, is acting as a lion un-tamer, taunting one lion, by making ugly faces, into a state of ferocity, which Boris describes as not only making him man-eating, but moose-eating. At the evening performance (presented with all three rings placed concentrically one inside the other, as this is a low-budget circus), Boris remains safe in his own act, using lions so old their bones creak, and whose teeth are false and removable before the performance. The one infuriated man-eater remains in his own cage adjoining the circular enclosure in which Boris performs, until Natasha is given the signal to open his cage door and release him. Instead of releasing the fierce lion into Boris’s enclosure, the cage of the beast has been rolled in backwards, and opens outward toward the crowd. Panic ensues, and Rocky and Bullwinkle, being heroes, are required by definition to stay rather than flee, to try to resolve the situation. Rocky does some fancy flying near the lion’s nose, to distract him long enough for the crowd to escape, while Bullwinkle creeps up upon the lion with a net. True to form (though the narrator has to cue the disbelieving moose into his own bungle), Bullwinkle trips and falls into his own net. Rocky, now distracted himself, is swatted out of the air by the lion’s paw, and pinned upon the ground in the lion’s grip. Bullwinkle somehow gets free of the net, and tries every diversion in the book (tap-dancing, juggling, etc.), with no effect upon the lion, until the moose is reduced to use his last two remaining belongings – a sheet of tissue paper and a comb. Humming into them like a kazoo, Bullwinkle finds music charms the savage beast, and Rocky is released. The lion still advances on Bullwinkle, but as the moose changes tunes to a lullaby, the king of beasts rolls over on his back, and falls fast asleep like a harmless kitten. Despite Boris’s blatant act of sabotage in releasing the lion upon the crowd, the Bumbling Brothers are reluctant to do anything against him, noting that every circus must have a lion tamer, so Boris has them over a barrel. But Rocky thinks otherwise, volunteering Bullwinkle’s services as new lion tamer. Boris finds himself out on his ear, and swears (literally in Pottsylvanian) to have his revenge on the show.

Boris’s first move is to make things “hot” for the brothers, by striking a match and setting fire to a stack of hay resting near the main tent. Rocky this time provides the rescue by lining up the elephants at a watering trough, and having them inhale snootfuls of water to hose down the flames. From this deed, Rocky also is hired as elephant trainer. Bullwinkle continues to wow the crowd with his tissue-and-comb serenades, not only charming both the young and old lions of Boris’s old act into becoming a performing dance troupe and acrobatic act, but having the same effect on virtually every other animal as well. The circus, flush with dough, decides to embark on a road show trip through Arizona and Nevada. But something is odd. In two states where the average rainfall is zero, black storm clouds trail the show wherever it appears, until the only two attendees are Igo’s and Hugo’s mothers-in-law. Rocky gets a boost from Bullwinkle to fly up to the clouds to see what is causing the freak weather. He radios Bullwinkle that he has spotted the problem from above, but is struck by a lightning bolt before he can reveal the secret, and falls into the convenient cockpit of a mysterious radio-controlled black plane with no pilot or control stick, and transported to a mesa where a large Indian ties Rocky to a stake. Bullwinkle trails Rocky, but is quickly captured and tied too. The Indian tribe appears, and Rocky reveals that he spotted them rain-dancing to create the clouds. Their “Chief Skunk-Who-Walk-Like-Man” is none other than Boris again, who orders that fires be lit below the two prisoners’ feet. Bullwinkle for once thinks on his feet, and encourages a festive mood out of the Indians by encouraging them to whoop it up in celebration, and playing a lively melody upon his tissue and comb. The Indians break into a dancing spree, which Boris quickly realizes is trouble, as the Indians, being rain-dancers, soon have a downpour created above them, putting the fire out. Big chief Boris and Natasha (dressed like the Lone Ranger), make an escape with a “Hi-Yo”, and a peace treaty is struck with the Indians.

Boris’s first move is to make things “hot” for the brothers, by striking a match and setting fire to a stack of hay resting near the main tent. Rocky this time provides the rescue by lining up the elephants at a watering trough, and having them inhale snootfuls of water to hose down the flames. From this deed, Rocky also is hired as elephant trainer. Bullwinkle continues to wow the crowd with his tissue-and-comb serenades, not only charming both the young and old lions of Boris’s old act into becoming a performing dance troupe and acrobatic act, but having the same effect on virtually every other animal as well. The circus, flush with dough, decides to embark on a road show trip through Arizona and Nevada. But something is odd. In two states where the average rainfall is zero, black storm clouds trail the show wherever it appears, until the only two attendees are Igo’s and Hugo’s mothers-in-law. Rocky gets a boost from Bullwinkle to fly up to the clouds to see what is causing the freak weather. He radios Bullwinkle that he has spotted the problem from above, but is struck by a lightning bolt before he can reveal the secret, and falls into the convenient cockpit of a mysterious radio-controlled black plane with no pilot or control stick, and transported to a mesa where a large Indian ties Rocky to a stake. Bullwinkle trails Rocky, but is quickly captured and tied too. The Indian tribe appears, and Rocky reveals that he spotted them rain-dancing to create the clouds. Their “Chief Skunk-Who-Walk-Like-Man” is none other than Boris again, who orders that fires be lit below the two prisoners’ feet. Bullwinkle for once thinks on his feet, and encourages a festive mood out of the Indians by encouraging them to whoop it up in celebration, and playing a lively melody upon his tissue and comb. The Indians break into a dancing spree, which Boris quickly realizes is trouble, as the Indians, being rain-dancers, soon have a downpour created above them, putting the fire out. Big chief Boris and Natasha (dressed like the Lone Ranger), make an escape with a “Hi-Yo”, and a peace treaty is struck with the Indians.

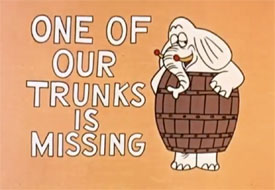

The circus resumes with full attendance, but startling news hits Rocky. His herd of elephants are weighing in at below the three-ton level – too small for the circus’s standards. He is almost fired, but Bullwinkle stands up for him, insisting, “If he goes, I go”. “No, I’m Igo”, quips one of the brothers. But anyway, Rocky stays on, until his elephants’ continued shrinkage reduces them to nearly walking skeletons. Rocky assesses their intake in hay, water, and peanuts from the kiddies, and calculates that the only way they could be losing weight is if someone was slipping them reducing pills. They weed out the “watering boy” (Boris, dressed as Gunga Din) and drive him away, taking over water and hay duties themselves. Rocky can’t believe any kid would continue to spike the elephants’ food supply, but of course, Boris has also been masquerading as a “mean widdle kid”, feeding the elephants peanut shells loaded with the reducing pills. Rocky fails to see through this disguise, and Boris adds insult to injury by chastising Rocky for his treatment of the elephants, and threatening to hit Rocky with his lollipop, making the squirrel think the kids of America have lost faith in him. With the squirrel on the ropes, now Boris decides it’s time to finish the moose. He and Natasha join the lion act inside a fake lion suit, equipped with steel bear-trap jaws dipped in poison, ready to do in the moose when he performs the head-in-the-lion’s-mouth trick. Just before Boris can trigger the trap, Rocky darts into the cage with a telegram from the Rocky and Bullwinkle fan club. In the message, the kids warn Bullwinkle not to put his head in, as it’s a trap – proving that America’s youth haven’t lost faith in them after all. Boris figures it’s time for a quick exit, but can’t get himself and Natasha out of the lion suit, as the zipper is stuck. Rocky concludes that the “lion” is too dangerous to keep in the performance, and arranges to donate the beast to a zoo – where Boris and Natasha seem destined to remain, with the zipper still refusing to budge. As the season closes, Rocky and Bullwinkle decide to five up their circus careers and return home (with no clue provided as to where the Brothers will find their next lion tamer and elephant trainer). All we hear of is newspaper stories indicating the success of the show on an international tour of Europe. Bullwinkle points out that the circus is known only by its initials in England – as the BBC. Rocky doesn’t get the reference, and Bullwinkle ends the story arc stuck with his bad joke and no reaction, for the fade out.

The circus resumes with full attendance, but startling news hits Rocky. His herd of elephants are weighing in at below the three-ton level – too small for the circus’s standards. He is almost fired, but Bullwinkle stands up for him, insisting, “If he goes, I go”. “No, I’m Igo”, quips one of the brothers. But anyway, Rocky stays on, until his elephants’ continued shrinkage reduces them to nearly walking skeletons. Rocky assesses their intake in hay, water, and peanuts from the kiddies, and calculates that the only way they could be losing weight is if someone was slipping them reducing pills. They weed out the “watering boy” (Boris, dressed as Gunga Din) and drive him away, taking over water and hay duties themselves. Rocky can’t believe any kid would continue to spike the elephants’ food supply, but of course, Boris has also been masquerading as a “mean widdle kid”, feeding the elephants peanut shells loaded with the reducing pills. Rocky fails to see through this disguise, and Boris adds insult to injury by chastising Rocky for his treatment of the elephants, and threatening to hit Rocky with his lollipop, making the squirrel think the kids of America have lost faith in him. With the squirrel on the ropes, now Boris decides it’s time to finish the moose. He and Natasha join the lion act inside a fake lion suit, equipped with steel bear-trap jaws dipped in poison, ready to do in the moose when he performs the head-in-the-lion’s-mouth trick. Just before Boris can trigger the trap, Rocky darts into the cage with a telegram from the Rocky and Bullwinkle fan club. In the message, the kids warn Bullwinkle not to put his head in, as it’s a trap – proving that America’s youth haven’t lost faith in them after all. Boris figures it’s time for a quick exit, but can’t get himself and Natasha out of the lion suit, as the zipper is stuck. Rocky concludes that the “lion” is too dangerous to keep in the performance, and arranges to donate the beast to a zoo – where Boris and Natasha seem destined to remain, with the zipper still refusing to budge. As the season closes, Rocky and Bullwinkle decide to five up their circus careers and return home (with no clue provided as to where the Brothers will find their next lion tamer and elephant trainer). All we hear of is newspaper stories indicating the success of the show on an international tour of Europe. Bullwinkle points out that the circus is known only by its initials in England – as the BBC. Rocky doesn’t get the reference, and Bullwinkle ends the story arc stuck with his bad joke and no reaction, for the fade out.

Bumpers and Intros for Rocky incarnations would also feature circus themes. A 15-minute syndicated edition called “The Rocky Show” used opening and closing title sequences depicting Rocky (for One Night Only) playing a rolling circus calliope, riding an elephant, jumping into a lion’s cage wagon and sticking his head into the beast’s mouth, then conducting Boris, Natasha, Captain Peter Peachfuzz, and Bullwinkle on a circus bandwagon, while himself playing fife. Matching closing credits featured more floats on parade bearing credits for the staff, and an elephant carrying traveling chair on its back for fictitious executive producer Ponsonby Britt, such producer only visible as a hand with smoke puffing from a large black pipe. (If 15 minutes seems an odd running time for a syndicated show this late in broadcasting history, it is believed such format, doubled up by most local stations into a half-hour, was created so as to allow those stations who chose it to devote the remaining 15 minutes of air time to Gamma Productions’ other principal product of the day, “The King and Odie Show”, a 15-minute block cut down from Total Television’s “King Leonardo and His Short Subjects”.)

A frequently seen bumper from “Rocky and His Friends”, believed to have been created for season 2, also featured Rocky at the top of a tall ladder on a diving platform, about to perform a dive into a tank of water far below (upon which a sign introducing Bullwinkle the Moose is painted0. Rocky leaps off, but uses the fur under his arms to soar in loops gracefully around the ladder as he descends. Bullwinkle, looking up, realizes that Rocky is not staying in a direct line to reach the water tank, so lifts the large bucket, and begins to run helter-skelter back and forth in attempt to keep the water under the squirrel. Eventually, Bullwinkle trips, and falls into the water himself, while Rocky, not needing the water at all, merely soars in and makes a graceful landing on the ground. Bullwinkle emerges dripping wet over the side wall of the tank, and Rocky exchanges a handshake of friendship with his pal as the bumper fades out. This sequence was capitalized upon in the additional season 5 story arc, “The Weather Lady”, in which the duo, needing quick money for a purchase to foil Boris’s latest evil plan, join up with a circus for a quick tour, replicating the same high-diving act always seen in the familiar bumper.

Another well-remembered element of “Rocky and His Friends” was “Peabody’s Improbable History”, in which genius Mr. Peabody (a college-educated dog), accompanied by his adopted human boy Sherman (voiced by Walter Tetley) would visit famous people of the past through Peabody’s massive time-traveling device, the W.A.B.A.C. Machine. In P.T. Barnum (season 1, circa 1960), they meet the creator of “The Greatest Show on Earth”, who has not yet joined up or merged with his later associates Bailey or the Ringling Brothers. Instead, Barnum has as co-owners of the show two trapeze artists who go by the names Hyde and Sick. They have a clause in their contract that, should Barnum fail to make the show go on at any time, all rights to the circus will revert to them. They thus engage in various skullduggery to sabotage the show. A high-diver takes a death-defying plunge – into a tank that has been drained of water, disappearing into a crater in the base of the empty tank. The script may have been edited for time or content, as the two villains (in dialogue that notably trades voices between characters in mid-stream, so we can’t really tell which villain is which) discuss having also sabotaged the lion act, expounding the pun “Remember the Mane”. Though Peabody and Sherman discover a picture of Barnum used as a dart board in the villains’ tent, as well as a voodoo doll of Barnum to implicate the trapeze performers as behind the sabotage, Barnum can’t call the police, as the villains are also his star performers, and if they don’t go on, the show won’t go on, and will revert to them. Hyde and Sick hear Barnum’s words, and determine that all they have to do to take over is not do anything. They thus resolve to remain stock still on their platform, refusing to begin their performance. Catching on, Peabody and Sherman ensure a bravura performance, as Peabody mounts to their platform, carrying a visitor – a skunk. The villains leap for the trapezes, seeking to escape by swinging to the opposite side of the tent. There, their exit is blocked by Sherman, carrying a blow torch. The villains thus spend hours swinging from one trapeze to another above the crowd, until they both hang over their trapezes, exhausted. Barnum still doesn’t have the heart to turn them over to the police, as theirs was the greatest trapeze performance he has ever seen. But they must be punished, so Peabody suggests a way. They continue to perform during each show, but after the performance are placed across the knee of the circus’s largest elephant, who whaps their rear-ends repeatedly with his massive trunk, “tanning their Hydes”, as Peabody puts it. Hyde himself has the last word, commenting to his villainous associate, “Now I’m sick, Sick.”

Another well-remembered element of “Rocky and His Friends” was “Peabody’s Improbable History”, in which genius Mr. Peabody (a college-educated dog), accompanied by his adopted human boy Sherman (voiced by Walter Tetley) would visit famous people of the past through Peabody’s massive time-traveling device, the W.A.B.A.C. Machine. In P.T. Barnum (season 1, circa 1960), they meet the creator of “The Greatest Show on Earth”, who has not yet joined up or merged with his later associates Bailey or the Ringling Brothers. Instead, Barnum has as co-owners of the show two trapeze artists who go by the names Hyde and Sick. They have a clause in their contract that, should Barnum fail to make the show go on at any time, all rights to the circus will revert to them. They thus engage in various skullduggery to sabotage the show. A high-diver takes a death-defying plunge – into a tank that has been drained of water, disappearing into a crater in the base of the empty tank. The script may have been edited for time or content, as the two villains (in dialogue that notably trades voices between characters in mid-stream, so we can’t really tell which villain is which) discuss having also sabotaged the lion act, expounding the pun “Remember the Mane”. Though Peabody and Sherman discover a picture of Barnum used as a dart board in the villains’ tent, as well as a voodoo doll of Barnum to implicate the trapeze performers as behind the sabotage, Barnum can’t call the police, as the villains are also his star performers, and if they don’t go on, the show won’t go on, and will revert to them. Hyde and Sick hear Barnum’s words, and determine that all they have to do to take over is not do anything. They thus resolve to remain stock still on their platform, refusing to begin their performance. Catching on, Peabody and Sherman ensure a bravura performance, as Peabody mounts to their platform, carrying a visitor – a skunk. The villains leap for the trapezes, seeking to escape by swinging to the opposite side of the tent. There, their exit is blocked by Sherman, carrying a blow torch. The villains thus spend hours swinging from one trapeze to another above the crowd, until they both hang over their trapezes, exhausted. Barnum still doesn’t have the heart to turn them over to the police, as theirs was the greatest trapeze performance he has ever seen. But they must be punished, so Peabody suggests a way. They continue to perform during each show, but after the performance are placed across the knee of the circus’s largest elephant, who whaps their rear-ends repeatedly with his massive trunk, “tanning their Hydes”, as Peabody puts it. Hyde himself has the last word, commenting to his villainous associate, “Now I’m sick, Sick.”

Dudley Do-Right would also have at least one circus encounter. In Mortgaging the Mountie Post (Season 1), Dudley is assigned to hold a solid-gold three-dollar watch intended for the retirement ceremony of their oldest mountie. He takes the liberty of cleaning it by tossing it into a washing machine, destroying the timepiece. Dudley is sent into town for a replacement watch, to the only shop in town carrying such artifacts – Snidely Whiplash’s hock shop. Having insufficient cash on him, Dudley signs a paper for a high-interest loan, mortgaging the post as collateral. The mounties can’t pay the exorbitant interest, and are soon packing their grips as Snidely prepares to assume ownership by 5:00. Snidely offers alternative terms – an exchange of the mortgage for Nell Fenwick’s hand in marriage. Dudley expresses moral outrage, but Nell seems surprisingly willing to make the noble sacrifice to save the post. Even though the amount of the debt has escalated to three million dollars and forty-five cents, Dudley vows to return with the money before foreclosure time – though he admits that getting that last forty-five cents might prove tough. Dudley and his horse sign up with a circus for a one-time performance of a horse-and-rider high diving act, for a sum of exactly the amount needed to satisfy the mortgage. While Dudley is afraid of heights, Horse isn’t. Unfortunately, Horse’s eyesight is poor, and the two miss the waiting water tank entirely. But they somehow survive, and seek the circus owner to claim their salary. Regrettably, in his eagerness to observe the act from a good vantage point, the circus owner backed too close to the lion’s cage, and all that is found of him on the ground before the cage is his ringmaster’s hat and coat, his whip, and his moustache. Dudley sadly hopes that he was covered by Blue Cross. Though defeated in his quest, Dudley still has an idea to save the day. As 5:00 approaches, Snidely hands the mortgage over to Inspector Fenwick, as he stands before a minister together with a tall veiled figure, whom he takes for his bride. Dudley enters upon conclusion of the ceremony, revealing that he has pulled a switch. Under the veil, Snidely’s bride turns out to be Dudley’s horse. What appears to be the real Nell now enters the room. “Say something, Nell”, requests Dudley. Confusingly, all “Nell” can do is respond in a horse-whinny, leaving a question as to who really won in the episode after all.

Dudley Do-Right would also have at least one circus encounter. In Mortgaging the Mountie Post (Season 1), Dudley is assigned to hold a solid-gold three-dollar watch intended for the retirement ceremony of their oldest mountie. He takes the liberty of cleaning it by tossing it into a washing machine, destroying the timepiece. Dudley is sent into town for a replacement watch, to the only shop in town carrying such artifacts – Snidely Whiplash’s hock shop. Having insufficient cash on him, Dudley signs a paper for a high-interest loan, mortgaging the post as collateral. The mounties can’t pay the exorbitant interest, and are soon packing their grips as Snidely prepares to assume ownership by 5:00. Snidely offers alternative terms – an exchange of the mortgage for Nell Fenwick’s hand in marriage. Dudley expresses moral outrage, but Nell seems surprisingly willing to make the noble sacrifice to save the post. Even though the amount of the debt has escalated to three million dollars and forty-five cents, Dudley vows to return with the money before foreclosure time – though he admits that getting that last forty-five cents might prove tough. Dudley and his horse sign up with a circus for a one-time performance of a horse-and-rider high diving act, for a sum of exactly the amount needed to satisfy the mortgage. While Dudley is afraid of heights, Horse isn’t. Unfortunately, Horse’s eyesight is poor, and the two miss the waiting water tank entirely. But they somehow survive, and seek the circus owner to claim their salary. Regrettably, in his eagerness to observe the act from a good vantage point, the circus owner backed too close to the lion’s cage, and all that is found of him on the ground before the cage is his ringmaster’s hat and coat, his whip, and his moustache. Dudley sadly hopes that he was covered by Blue Cross. Though defeated in his quest, Dudley still has an idea to save the day. As 5:00 approaches, Snidely hands the mortgage over to Inspector Fenwick, as he stands before a minister together with a tall veiled figure, whom he takes for his bride. Dudley enters upon conclusion of the ceremony, revealing that he has pulled a switch. Under the veil, Snidely’s bride turns out to be Dudley’s horse. What appears to be the real Nell now enters the room. “Say something, Nell”, requests Dudley. Confusingly, all “Nell” can do is respond in a horse-whinny, leaving a question as to who really won in the episode after all.

One of the last Ward projects to include a circus connection was George of the Jungle’s Big Flop at the Big Top (12/2/67). The Ring-a-Ding Brothers’ Circus spotlights the Great Fettuccini, who attempts to high0dive in a triple somersault into a damp handkerchief. His dive misses the handkerchief entirely, and he quits the show, as no one told him it was going to hurt. Using process of elimination, the circus owners realize no one is stupid enough to perform the same stunt among trapeze artists – except George of the Jungle. Two villains (Tiger and Weevil), are hired to trap George, at a promised salary of 10,000 clams Tiger would have preferred they get paid in real money, but Weevil reminds him that money can be traced. Tiger remarks, “So can clams – especially at low tide.” The body of the episode has little to do with circus life, instead becoming a standard bait-and-capture comedy with a few twists. Remembering Rags the Tiger’s entrance, a record of a woman’s voice yelling “Help, murder, police!” is used to lure George to various locations, ending with the words “This has been a recorded message,” Weevil raises a cage into the trajectory of George’s vine swing, but forgets to latch the rear door of same, so that George merely sails through. Tiger reminds Weevil, “When will you learn to keep your trap shut?” A pit trap is fallen into by the villains when a lion appears behind them. George knows the lion on first-name basis, having once removed a thorn from his paw (which the lion proves by displaying his still-present Band-Aid). The villains saw a hole out from under George while in his tree house, then stuff the unconscious George under the hood of their Jeep, as Tiger calls out to Ursula above, “I came, I saw, I conked him.” Sticking his head through the hole for one of the front headlights, George lets out a jungle yell, calling a rhinoceros for assistance. Instead, he gets a giant man-eating plant, who does just as well. Geoge points out that he had also done a favor for the plant, removing a paw from his thorn. The villains give up, and the narrator notes that now, we’ll never know if George could have performed a triple somersault into a damp handkerchief. Bit in fact, George and Ape, just for curiosity, are in the process of replicating the same stunt. Like Fettuccini, George misses the hankie, landing rigidly on his head upon the ground, knocking himself unconscious. Ape answers the narrator’s question: “The answer is…no.”

One of the last Ward projects to include a circus connection was George of the Jungle’s Big Flop at the Big Top (12/2/67). The Ring-a-Ding Brothers’ Circus spotlights the Great Fettuccini, who attempts to high0dive in a triple somersault into a damp handkerchief. His dive misses the handkerchief entirely, and he quits the show, as no one told him it was going to hurt. Using process of elimination, the circus owners realize no one is stupid enough to perform the same stunt among trapeze artists – except George of the Jungle. Two villains (Tiger and Weevil), are hired to trap George, at a promised salary of 10,000 clams Tiger would have preferred they get paid in real money, but Weevil reminds him that money can be traced. Tiger remarks, “So can clams – especially at low tide.” The body of the episode has little to do with circus life, instead becoming a standard bait-and-capture comedy with a few twists. Remembering Rags the Tiger’s entrance, a record of a woman’s voice yelling “Help, murder, police!” is used to lure George to various locations, ending with the words “This has been a recorded message,” Weevil raises a cage into the trajectory of George’s vine swing, but forgets to latch the rear door of same, so that George merely sails through. Tiger reminds Weevil, “When will you learn to keep your trap shut?” A pit trap is fallen into by the villains when a lion appears behind them. George knows the lion on first-name basis, having once removed a thorn from his paw (which the lion proves by displaying his still-present Band-Aid). The villains saw a hole out from under George while in his tree house, then stuff the unconscious George under the hood of their Jeep, as Tiger calls out to Ursula above, “I came, I saw, I conked him.” Sticking his head through the hole for one of the front headlights, George lets out a jungle yell, calling a rhinoceros for assistance. Instead, he gets a giant man-eating plant, who does just as well. Geoge points out that he had also done a favor for the plant, removing a paw from his thorn. The villains give up, and the narrator notes that now, we’ll never know if George could have performed a triple somersault into a damp handkerchief. Bit in fact, George and Ape, just for curiosity, are in the process of replicating the same stunt. Like Fettuccini, George misses the hankie, landing rigidly on his head upon the ground, knocking himself unconscious. Ape answers the narrator’s question: “The answer is…no.”

More early TV fun from random studios, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

I always thought the most horrifically grotesque CGI baby in the history of the medium was the dancing one on “Ally McBeal”, but then I had never seen “Tin Toy” before today. A new champion! As for “Red’s Dream”, if there’s anything I hate more than the Albinoni Adagio, it’s listening to someone vocalise it with too much digital delay while a creepy-looking clown juggles on a unicycle. I remember seeing “Luxo Jr.” at an animation festival in the ’80s and being conscious that Pixar was creating a revolution in animation, but these two…. yeesh. Give me a Paul Smith Woody any day.

The Jay Ward cartoons were a pleasure to watch, as always. The confusion between Hyde and Sick is so thorough that I can’t help but wonder if it was deliberate.

In case anyone is curious, and I’m pretty sure no one is, the skin membrane between the limbs of a flying squirrel (or any gliding mammal) is called a patagium. It comes up in crossword puzzles every so often.

Well, CGI has advanced since then. And I disagree about that Smith cartoon (which had the worst example of a running in the hallways gag) was better than the two Pixar shorts, especially since “Tin Toy” has since gotten into The Library of Congress’ The National Film Registry.

CGI may have advanced, but human skin still looks like plastic and human characters still look too much like dolls to provide the proper contrast with (animated) inanimate objects. Part of the problem is that the primary appeal of computer animation is that it fulfills, with its simulation of the third dimension and photo-realism, childhood’s oldest fantasy: toys coming to life and becoming playmates; “human” CGI characters are designed accordingly.

It’s basically virtual stop-motion more or less which is the oldest form of film animation.

You misunderstand me, Nic. By no means did I mean to imply that I thought “Seal on the Loose” was a better cartoon than “Red’s Dream” or “Tin Toy”. What I meant was, I would rather see ANY Paul J. Smith Woody Woodpecker (or Chilly Willy or Beary Family) cartoon than sit through either of those two Pixar shorts again. Maybe my tastes are a little eccentric, but I’m put off by the sight of monstrous drooling babies and the sound of Albinoni being yodelled in an echo chamber.

Okay, I get it. Sorry about it.

I’m assuming that “missing” Astronut short, “Going Ape” may have taken place at a zoo and not the circus, but that’s just a guess.

Interesting that Rocky, usually Bullwinkle’s straight man sidekick by this time, dominates the “Rocky Show” titles with Bullwinkle absent until the final gag.

May have come up before, but some pioneering cartoon shows — all cartoons, without human hosts — opened and closed in circus settings. Barker Bill presenting Terrytoons at the circus; Huckleberry Hound careening around the main tent in a car full of Kellogg’s mascots; and Matty’s Funday Funnies showing Harveytoon characters chasing around a big top / fairground.

The Bozo franchise naturally duplicated the animated Bozo’s milieu, and there are at least circus references in the opening titles of the Mickey Mouse Club (clowns and marching bands) before Mickey welcomes us on a proscenium theater stage.

The idea that the circus was the ultimate kid-friendly entertainment was already fading. The syndicated Three Stooges cartoons introduced them as circus-type musicians on parade, but personally don’t recall much if anything beyond that.