Another look at circus life, spanning the period from 1953 into 1955. Circus cartoons were starting to become a little less common by this period, perhaps in attempt to lessen budgets. However, as initiated by UPA’s Magoo episode discussed last week, and continued with another UPA entry discussed here, animators would soon discover that circus fare could be adapted to limited animation and presented without the need for extreme detail and hoopla, guaranteeing the genre’s continued appearance in theatrical productions from time to time, and especially in frequent storylines developed for television. Stars appearing among this week’s offerings include Donald Duck, Tweety and Sylvester, Herman and Katnip, Casper, and an early appearance by Walter Lantz’s star-wanna-be, Sugarfoot.

The Mouse and the Lion (Lantz/Universal, Foolish Fable, 5/11/53 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – Buck Mouse, circus talent scout, roams the jungles of Africa on safari in search of a new animal act for the Bungling Brothers Circus. There is actually very little to recommend about this one, which quickly becomes a routine cat-and-mouse pursuit between Buck and the king of beasts, with practically no creative gags. The closest things to memorable moments are a scene in which the lion’s tail repeatedly drapes over the head of Buck, transforming in shape from various wig hairstyles to a coonskin cap, and even a beard. And a scene where Buck fills a dummy mouse with a lit firecracker, which the lion ingests after threatening the dummy, “Speak up or be et’ up.” The lion finally falls into his own crate of mousetraps, and is captured. He performs in the circus show for the finale, riding a unicycle on a high wire while juggling hoops in his hands and balls with his tail, periodically dodging the mile-long whip of Buck to flip the whole act upside-down. Buck takes a final bow to the crowd, revealing himself to be wearing the lion’s crown under his own ringmaster’s hat.

The Mouse and the Lion (Lantz/Universal, Foolish Fable, 5/11/53 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – Buck Mouse, circus talent scout, roams the jungles of Africa on safari in search of a new animal act for the Bungling Brothers Circus. There is actually very little to recommend about this one, which quickly becomes a routine cat-and-mouse pursuit between Buck and the king of beasts, with practically no creative gags. The closest things to memorable moments are a scene in which the lion’s tail repeatedly drapes over the head of Buck, transforming in shape from various wig hairstyles to a coonskin cap, and even a beard. And a scene where Buck fills a dummy mouse with a lit firecracker, which the lion ingests after threatening the dummy, “Speak up or be et’ up.” The lion finally falls into his own crate of mousetraps, and is captured. He performs in the circus show for the finale, riding a unicycle on a high wire while juggling hoops in his hands and balls with his tail, periodically dodging the mile-long whip of Buck to flip the whole act upside-down. Buck takes a final bow to the crowd, revealing himself to be wearing the lion’s crown under his own ringmaster’s hat.

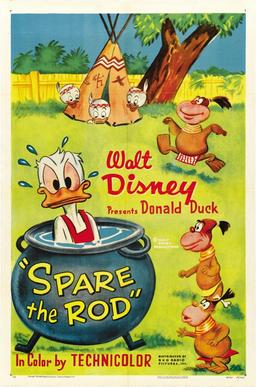

Spare the Rod (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 1/15/54 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – An odd entry in the series, first for its use of some slide-like intertitles and deliberately corny narration, and secondly, as one of the last racially politically-incorrect cartoons to be produced involving cannibals (possibly the only one later was Paramount’s Chew Chew Baby, though the color chosen for Chew Chew’s skin was more neutral than Negro). We open at Donald’s house, where everyone is supposed to be doing their chores. But the log pile where Huey, Louie, and Dewey are supposed to be chopping firewood has been deserted. They are off playing at being island natives in a makeshift grass hut, dancing a savage dance to tom-tom beat with wooden knives flashing about. Donald’s steadiness of hand is disturbed by the drum beats while painting a window frame, and he retaliates by using his paints to create a horrific tiki face upon the top lid of an old barrel, lifting it to the door of the hut and uttering angry roars to scare the kids out and back to work. But the effort doesn’t last long, and soon the boys have abandoned their work again, now playing pirate on a home-made replica ship’s deck. Donald prepares to wage war upon them again, when he is stopped in his tracks by the appearance of a miniature duck-spirit in a college cap and gown (voiced by Bill Thompson), announcing himself as the Voice of Child Psychology. The tiny egghead spirit suggests that the way to get the kids’ cooperation is not to treat them rough, but to win their confidence, join in their games, and be a pal. At the spirit’s prompting, Donald joins in the pirate games, wearing a patch over one eye and carrying a parrot puppet – but his first effort only succeeds in having him walk the plank into a bucket of water.

Spare the Rod (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 1/15/54 – Jack Hannah, dir.) – An odd entry in the series, first for its use of some slide-like intertitles and deliberately corny narration, and secondly, as one of the last racially politically-incorrect cartoons to be produced involving cannibals (possibly the only one later was Paramount’s Chew Chew Baby, though the color chosen for Chew Chew’s skin was more neutral than Negro). We open at Donald’s house, where everyone is supposed to be doing their chores. But the log pile where Huey, Louie, and Dewey are supposed to be chopping firewood has been deserted. They are off playing at being island natives in a makeshift grass hut, dancing a savage dance to tom-tom beat with wooden knives flashing about. Donald’s steadiness of hand is disturbed by the drum beats while painting a window frame, and he retaliates by using his paints to create a horrific tiki face upon the top lid of an old barrel, lifting it to the door of the hut and uttering angry roars to scare the kids out and back to work. But the effort doesn’t last long, and soon the boys have abandoned their work again, now playing pirate on a home-made replica ship’s deck. Donald prepares to wage war upon them again, when he is stopped in his tracks by the appearance of a miniature duck-spirit in a college cap and gown (voiced by Bill Thompson), announcing himself as the Voice of Child Psychology. The tiny egghead spirit suggests that the way to get the kids’ cooperation is not to treat them rough, but to win their confidence, join in their games, and be a pal. At the spirit’s prompting, Donald joins in the pirate games, wearing a patch over one eye and carrying a parrot puppet – but his first effort only succeeds in having him walk the plank into a bucket of water.

Meanwhile, a circus train chugs past town. In one cage of the train rides a trio of genuine pigmy cannibals. One of them reaches out between the bars to pull out the pin connecting their cage to the rest of the train. Their cage rolls back downhill along the tracks, derails, and crashes open, releasing the pigmies. They begin a war chant, and proceed into town, passing the gate of Donald’s home One spies Donald working in his yard, and the three of them envision Donald in roasted form. Inside the yard, the psychology spirit reappears, spotting the cannibals first. Due to the pigmies’ tiny size, the spirit jumps to the conclusion that they are the nephews again in a new game, now in disguise. He alerts Donald that the boys are back, and convinces Donald that playing along is the perfect setup to get the firewood chopped – as a cannibal pot will need firewood to boil. Donald not only cooperates at spearpoint, but drags in a cooking pot himself, and fills it with water from a garden hose. Then, he convinces the “boys” to go cut the firewood. The spirit congratulates Donald on the success of the plan, as the cannibals get busy chopping. On the other side of the yard, the real nephews are now playing Indians. They spot Donald in the pot, and take him out as hostage, tying him to a stake in their play-encampment. They too will need firewood to burn their captive, so also begin chopping away. The spirit now has double reasons for congratulating Donald, with the assurance that now, there should be enough firewood chopped to last all winter. But the cannibals return to the pot to find it empty. Searching the yard, they find Donald tied to the stake. Lifting the stake out of the ground, they carry it and the still-tied Donald back to the pot, dumping them inside. The nephews return to the camp to find their hostage gone, and attempt to take Donald back, resulting in a tug of war over the stake between the nephews and the cannibals. The spirit reappears, and realizes something is mathematically amiss. “Three Indians and three cannibals….You got six nephews?”. he asks Donald. The answer is obvious, and everyone suddenly realizes the cannibals are real. The spirit and the nephews flee in panic, leaving Donald at the mercy of the savages. Donald has an apple stuffed in his mouth, yet mumbles a prayer with hands together amidst the binding ropes. The fire is lit, and one of the cannibals performs a taste test upon Donald by biting his foot. Donald shouts in pain, and bursts out of his bonds, grabbing up the cannibals. To teach them a lesson, he carries them off to the woodshed, where the sounds of a loud spanking are heard amidst the shed’s violent vibrations. The three cannibals exit and disappear down the railroad tracks, holding onto their painful rear ends. Donald confronts the nephews, impatiently stamping his foot. The boys know better than to cross Donald in this state of temper, and resume their woodchopping at a vigorous triple-tempo. The spirit appears again, but, rather than give praise to Donald’s old-fashioned approach, tries to claim the credit. “See how my modern psychology works?” “What?”, says Donald, seizing up the spirit in one hand. The spirit sheepishly shrugs his shoulders, changing his tune. “Oh, well, your psychology, my psychology…What’s the difference?” “I’ll show ya’ the difference”, quacks Donald, and returns with the spirit to the woodshed, where we hear the spirit’s shouts as another loud spanking is administered, for the iris out.

Meanwhile, a circus train chugs past town. In one cage of the train rides a trio of genuine pigmy cannibals. One of them reaches out between the bars to pull out the pin connecting their cage to the rest of the train. Their cage rolls back downhill along the tracks, derails, and crashes open, releasing the pigmies. They begin a war chant, and proceed into town, passing the gate of Donald’s home One spies Donald working in his yard, and the three of them envision Donald in roasted form. Inside the yard, the psychology spirit reappears, spotting the cannibals first. Due to the pigmies’ tiny size, the spirit jumps to the conclusion that they are the nephews again in a new game, now in disguise. He alerts Donald that the boys are back, and convinces Donald that playing along is the perfect setup to get the firewood chopped – as a cannibal pot will need firewood to boil. Donald not only cooperates at spearpoint, but drags in a cooking pot himself, and fills it with water from a garden hose. Then, he convinces the “boys” to go cut the firewood. The spirit congratulates Donald on the success of the plan, as the cannibals get busy chopping. On the other side of the yard, the real nephews are now playing Indians. They spot Donald in the pot, and take him out as hostage, tying him to a stake in their play-encampment. They too will need firewood to burn their captive, so also begin chopping away. The spirit now has double reasons for congratulating Donald, with the assurance that now, there should be enough firewood chopped to last all winter. But the cannibals return to the pot to find it empty. Searching the yard, they find Donald tied to the stake. Lifting the stake out of the ground, they carry it and the still-tied Donald back to the pot, dumping them inside. The nephews return to the camp to find their hostage gone, and attempt to take Donald back, resulting in a tug of war over the stake between the nephews and the cannibals. The spirit reappears, and realizes something is mathematically amiss. “Three Indians and three cannibals….You got six nephews?”. he asks Donald. The answer is obvious, and everyone suddenly realizes the cannibals are real. The spirit and the nephews flee in panic, leaving Donald at the mercy of the savages. Donald has an apple stuffed in his mouth, yet mumbles a prayer with hands together amidst the binding ropes. The fire is lit, and one of the cannibals performs a taste test upon Donald by biting his foot. Donald shouts in pain, and bursts out of his bonds, grabbing up the cannibals. To teach them a lesson, he carries them off to the woodshed, where the sounds of a loud spanking are heard amidst the shed’s violent vibrations. The three cannibals exit and disappear down the railroad tracks, holding onto their painful rear ends. Donald confronts the nephews, impatiently stamping his foot. The boys know better than to cross Donald in this state of temper, and resume their woodchopping at a vigorous triple-tempo. The spirit appears again, but, rather than give praise to Donald’s old-fashioned approach, tries to claim the credit. “See how my modern psychology works?” “What?”, says Donald, seizing up the spirit in one hand. The spirit sheepishly shrugs his shoulders, changing his tune. “Oh, well, your psychology, my psychology…What’s the difference?” “I’ll show ya’ the difference”, quacks Donald, and returns with the spirit to the woodshed, where we hear the spirit’s shouts as another loud spanking is administered, for the iris out.

The Man on the Flying Trapeze (UPA/Columbia, 4/8/54, Ted Parmelee, dir.) – Writers Bill Scott and Fred Grable attempt to draw some new life out of the old and well-worn song first used by Popeye and Krazy Kat in the 1930’s. Their result plays like a watered-down version of the period-pieces, “The Dover Boys at Pimento University” from Warner, or Columbia’s own follow-up, “The Rocky Road to Ruin”, failing to generate the energy of either of such predecessors. The tale is told by a destitute young man (Wesley) playing drum in a street band, accompanied by a few off-key brass players and a coin-operated player piano (which keeps needing insertion of nickels at inopportune moments in the storytelling, for a running gag). In flashback, the young man courts one Fifi, winning kewpie dolls for her at a carnival dart-throwing gallery. Fifi is suddenly attracted by a poster for Alonzo, the man on the flying trapeze at the neighboring circus. Attending the show, she is smitten by the performer, just as Krazy Kat’s and Blackie Sheep’s girlfriends had been before her. She tosses a kewpie doll up to the performer, clunking him accidentally on the head, and leaving him hanging from the trapeze by his nose. But she has caught his attention, and the sparkles in their eyes indicate trouble for Wesley. Soon, Alonzo is greeting Fifi by her gate, and while Wesley carries a whole armful of prizes and presents for Fifi as he attempts to enter the gate, Alonzo is able to impress Fifi with a gift of only a single kewpie doll, causing her to leave Wesley stranded at the gate, with Fifi’s voracious dog chewing on his ankle. Next, Alonzo outraces Wesley on bicycle, arriving first at Fifi’s home for a date. Wesley fails to notice Alonzo meeting with Fifi secretly at her upper-story back window, while Wesley makes an entrance at the front door, becoming overwhelmed by mundane conversation from Fifi’s parents. Outside, Alonzo is rigging up a rope and pulley to reach Fifi’s window, plotting to spirit Fifi away. Fifi’s head appears upside-down through a window of the living room below, tossing Wesley the end of the rope, and asking him to “Hold this.” Wesley takes hold, unknowingly steadying a platform for Alonzo and the girl to descend from her window. As the lovers’ combined weight is added to the platform, they descend while Wesley is dragged to the ceiling. Then, as the lovers leave the platform, Wesley falls, through the living room coffee table.

The Man on the Flying Trapeze (UPA/Columbia, 4/8/54, Ted Parmelee, dir.) – Writers Bill Scott and Fred Grable attempt to draw some new life out of the old and well-worn song first used by Popeye and Krazy Kat in the 1930’s. Their result plays like a watered-down version of the period-pieces, “The Dover Boys at Pimento University” from Warner, or Columbia’s own follow-up, “The Rocky Road to Ruin”, failing to generate the energy of either of such predecessors. The tale is told by a destitute young man (Wesley) playing drum in a street band, accompanied by a few off-key brass players and a coin-operated player piano (which keeps needing insertion of nickels at inopportune moments in the storytelling, for a running gag). In flashback, the young man courts one Fifi, winning kewpie dolls for her at a carnival dart-throwing gallery. Fifi is suddenly attracted by a poster for Alonzo, the man on the flying trapeze at the neighboring circus. Attending the show, she is smitten by the performer, just as Krazy Kat’s and Blackie Sheep’s girlfriends had been before her. She tosses a kewpie doll up to the performer, clunking him accidentally on the head, and leaving him hanging from the trapeze by his nose. But she has caught his attention, and the sparkles in their eyes indicate trouble for Wesley. Soon, Alonzo is greeting Fifi by her gate, and while Wesley carries a whole armful of prizes and presents for Fifi as he attempts to enter the gate, Alonzo is able to impress Fifi with a gift of only a single kewpie doll, causing her to leave Wesley stranded at the gate, with Fifi’s voracious dog chewing on his ankle. Next, Alonzo outraces Wesley on bicycle, arriving first at Fifi’s home for a date. Wesley fails to notice Alonzo meeting with Fifi secretly at her upper-story back window, while Wesley makes an entrance at the front door, becoming overwhelmed by mundane conversation from Fifi’s parents. Outside, Alonzo is rigging up a rope and pulley to reach Fifi’s window, plotting to spirit Fifi away. Fifi’s head appears upside-down through a window of the living room below, tossing Wesley the end of the rope, and asking him to “Hold this.” Wesley takes hold, unknowingly steadying a platform for Alonzo and the girl to descend from her window. As the lovers’ combined weight is added to the platform, they descend while Wesley is dragged to the ceiling. Then, as the lovers leave the platform, Wesley falls, through the living room coffee table.

Fifi joins Alonzo’s act as an added attraction. Wesley follows the circus, hoping to win her back, by applying for a job with the show as a sweeper (stuck with the same sort of tasks Woody Woodpecker detested – cleaning up after the elephants). He watches each day as Alonzo and Fifi perform, but gets nowhere in diverting Fifi’s attentions back to him. Meanwhile, Fifi becomes a crowd favorite, her name becoming larger and larger in billing, until it finally tops the billing of Alonzo. One day, Fifi pulls a fast one, as Alonzo prepares to perform a triple somersault to a trapeze, then catch the bar with his teeth while carrying two flaming torches. Fifi tosses a rope down to Wesley, again asking him to “Hold this”. The rope is holding up the trapeze to which Alonzo is about to swing. Fifi then tosses a flower to Wesley below, just slightly out of his reach. The lovestruck boy leans forward, finding he cannot reach the flower without letting go of the rope. As he does so, he unknowingly removes all support for Alonzo, who, with the trapeze bar still clenched between his teeth, falls to his doom, despite landing upon the ringmaster. Fifi races to the scene, her only concern being the welfare of the ringmaster, who it is revealed she has eyes for – especially for the large diamond stick-pin protruding from the tip of his tie. The film reverts back to the present, where the player piano has run out of nickels, and is run over by a limousine carrying the ringmaster and Fifi. Fifi is now bedecked in jewels, and commands star billing of the show, giving the audience a knowing wink. The boy and his band are left staring at the protruding mainsprings of the wrecked player piano, as the boy concludes with the last line of the old song, “And that’s what’s become of my love.”

Fifi joins Alonzo’s act as an added attraction. Wesley follows the circus, hoping to win her back, by applying for a job with the show as a sweeper (stuck with the same sort of tasks Woody Woodpecker detested – cleaning up after the elephants). He watches each day as Alonzo and Fifi perform, but gets nowhere in diverting Fifi’s attentions back to him. Meanwhile, Fifi becomes a crowd favorite, her name becoming larger and larger in billing, until it finally tops the billing of Alonzo. One day, Fifi pulls a fast one, as Alonzo prepares to perform a triple somersault to a trapeze, then catch the bar with his teeth while carrying two flaming torches. Fifi tosses a rope down to Wesley, again asking him to “Hold this”. The rope is holding up the trapeze to which Alonzo is about to swing. Fifi then tosses a flower to Wesley below, just slightly out of his reach. The lovestruck boy leans forward, finding he cannot reach the flower without letting go of the rope. As he does so, he unknowingly removes all support for Alonzo, who, with the trapeze bar still clenched between his teeth, falls to his doom, despite landing upon the ringmaster. Fifi races to the scene, her only concern being the welfare of the ringmaster, who it is revealed she has eyes for – especially for the large diamond stick-pin protruding from the tip of his tie. The film reverts back to the present, where the player piano has run out of nickels, and is run over by a limousine carrying the ringmaster and Fifi. Fifi is now bedecked in jewels, and commands star billing of the show, giving the audience a knowing wink. The boy and his band are left staring at the protruding mainsprings of the wrecked player piano, as the boy concludes with the last line of the old song, “And that’s what’s become of my love.”

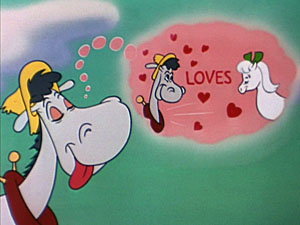

Hay Rube (Lantz/Universal, Sugarfoot, 6/7/54 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – Smith had been one of the principal animators on Bob Clampett’s financially (but not creatively-lacking) failed attempt to launch his own theatrical productions after leaving Warner Brothers, on the single episode of the intended series “Charlie Horse” for Republic, It’s a Grand Old Nag. When Smith came to Lantz studios, he seemed to treat the property as his own, probably going under the correct presumption that the vast majority of moviegoers never got to see the prior work. Making the most of his existing material, he rechristened the farm horse character as Sugarfoot, then divided the plotline of “Grand Old Nag” into two separate cartoons. The first was “A Horse’s Tale”, concentrating upon the portions of the original script casting the horse as a Hollywood stunt double. The second production (the cartoon we are now reviewing) lifted the ideas from portions of “Nag” dealing with the horse’s love-crush upon a celebrity filly (in the original named Hay-dee La Mare, in this episode renamed Starbright). Although Michael Maltese receives story credit, the film is one of his weaker efforts, probably due to the fact it is more of an “adapted” script than an original one. Notably, beyond these borrowed concepts, Smith was largely out of ideas to expand his horse-star’s career beyond these two episodes, and quickly dropped the character for several seasons. Only many years later would Sugarfoot resurface, as a recurring default horse in a seemingly never-ending supply of stock Westerns for Woody Woodpecker.

Hay Rube (Lantz/Universal, Sugarfoot, 6/7/54 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – Smith had been one of the principal animators on Bob Clampett’s financially (but not creatively-lacking) failed attempt to launch his own theatrical productions after leaving Warner Brothers, on the single episode of the intended series “Charlie Horse” for Republic, It’s a Grand Old Nag. When Smith came to Lantz studios, he seemed to treat the property as his own, probably going under the correct presumption that the vast majority of moviegoers never got to see the prior work. Making the most of his existing material, he rechristened the farm horse character as Sugarfoot, then divided the plotline of “Grand Old Nag” into two separate cartoons. The first was “A Horse’s Tale”, concentrating upon the portions of the original script casting the horse as a Hollywood stunt double. The second production (the cartoon we are now reviewing) lifted the ideas from portions of “Nag” dealing with the horse’s love-crush upon a celebrity filly (in the original named Hay-dee La Mare, in this episode renamed Starbright). Although Michael Maltese receives story credit, the film is one of his weaker efforts, probably due to the fact it is more of an “adapted” script than an original one. Notably, beyond these borrowed concepts, Smith was largely out of ideas to expand his horse-star’s career beyond these two episodes, and quickly dropped the character for several seasons. Only many years later would Sugarfoot resurface, as a recurring default horse in a seemingly never-ending supply of stock Westerns for Woody Woodpecker.

Starbright the Miracle Mare is appearing for one night only with the Jingling Brothers Circus. Sugarfoot is haunted by her image, the moon and stars outside his barn window at noght transforming into multiple miniatures of her face. He sneaks out of his stall to attend the show. At the circus grounds, having no money, he is unable to get inside, or past the circus cop when he tries to sneak a peek under the tent flaps. But the act he wants to see is not yet inside, and is still rehearsing in a wagon nearby. While Hay-dee La Mere in the original plot was a Western movie star, Maltese here doesn’t come up with much of an act for Starbright to perform. Her act consists of the mere equivalent of a seal’s tuned horns bit, which Starbright accomplishes by grasping tuned Swiss bells one by one with her teeth. The ringmaster admonishes her for not knowing the difference between an A-flat and a B-major, and in action unseen by the camera but suggested by the ringmaster’s yells and sound effects, applies the whip unmercifully to Starbright. Sugarfoot kicks in the wagon door, sending it flying across the room within, smashing the ringmaster flat against the opposite wall. Sugarfoot nuzzles with the affectionate and grateful Starbright, but when Sugarfoot tries to return Starbright’s kiss, he ends up in a liplock with the ringmaster, who has retrieved a shotgun. The chase is on, and Sugarfoot and the ringmaster mount an exterior ladder to an entrance door high on the wall of the big top. As in “Inki at the Circus” (a script also co-written by Maltese), they enter the doorway to find themselves walking on the high wire. Sugarfoot struggles to maintain balance, then finds himself about to sneeze. The ringmaster places a finger under Sugarfoot’s nose, preventing the sneeze- but then sneezes himself. The two fall off the wire, bounce off a trampoline, then wind up on a trapeze. The trapeze swings low, smacking Sugarfoot into the ground, while the ringmaster continues on for the full swing, bursting out through the tent roof. He lands atop an elephant, who flings him away with its trunk, into the wall of a cage from which the ringmaster is almost mauled by tigers. The ringmaster slides back into the big top, and takes a pot shot at Sugarfoot.

Starbright the Miracle Mare is appearing for one night only with the Jingling Brothers Circus. Sugarfoot is haunted by her image, the moon and stars outside his barn window at noght transforming into multiple miniatures of her face. He sneaks out of his stall to attend the show. At the circus grounds, having no money, he is unable to get inside, or past the circus cop when he tries to sneak a peek under the tent flaps. But the act he wants to see is not yet inside, and is still rehearsing in a wagon nearby. While Hay-dee La Mere in the original plot was a Western movie star, Maltese here doesn’t come up with much of an act for Starbright to perform. Her act consists of the mere equivalent of a seal’s tuned horns bit, which Starbright accomplishes by grasping tuned Swiss bells one by one with her teeth. The ringmaster admonishes her for not knowing the difference between an A-flat and a B-major, and in action unseen by the camera but suggested by the ringmaster’s yells and sound effects, applies the whip unmercifully to Starbright. Sugarfoot kicks in the wagon door, sending it flying across the room within, smashing the ringmaster flat against the opposite wall. Sugarfoot nuzzles with the affectionate and grateful Starbright, but when Sugarfoot tries to return Starbright’s kiss, he ends up in a liplock with the ringmaster, who has retrieved a shotgun. The chase is on, and Sugarfoot and the ringmaster mount an exterior ladder to an entrance door high on the wall of the big top. As in “Inki at the Circus” (a script also co-written by Maltese), they enter the doorway to find themselves walking on the high wire. Sugarfoot struggles to maintain balance, then finds himself about to sneeze. The ringmaster places a finger under Sugarfoot’s nose, preventing the sneeze- but then sneezes himself. The two fall off the wire, bounce off a trampoline, then wind up on a trapeze. The trapeze swings low, smacking Sugarfoot into the ground, while the ringmaster continues on for the full swing, bursting out through the tent roof. He lands atop an elephant, who flings him away with its trunk, into the wall of a cage from which the ringmaster is almost mauled by tigers. The ringmaster slides back into the big top, and takes a pot shot at Sugarfoot.

Sugarfoot hides inside the mouth of the human cannonball’s cannon. The cannon act goes on, and two figures emerge from the muzzle – the cannonball daredevil, riding atop Sugarfoot’s back into the net. Sugarfoot takes a bow, then ducks out of sight as another shot rings out. The ringmaster searches the arena, not realizing he has walked into the act of Asbesto the Fire Walker, and is standing upon a bed of red-hot coals. The ringmaster dives for one of the side rings, where an ice-skating act is going on. The ringmaster’s hot feet are quickly cooled, but melt through the ice surface, leaving him fallen into a puddle. Sugarfoot scrambles up a ladder to a high-diving platform, then loses his balance above, falling rapidly toward the arena floor. The ringmaster, with murderous intent, pushes the waiting water tank out of the way – but quickly realizes this was a mistake, as the shadow of the descending horse envelops him. Sugarfoot lands upon him with a thud, then rises to take a bow, while the ringmaster runs around and around, crushed down into his large top hat with only his waddling feet visible below. Sugarfoot won’t share the spotlight, and gives the hat a quick kick to get the ringmaster out of the way.

Sugarfoot hides inside the mouth of the human cannonball’s cannon. The cannon act goes on, and two figures emerge from the muzzle – the cannonball daredevil, riding atop Sugarfoot’s back into the net. Sugarfoot takes a bow, then ducks out of sight as another shot rings out. The ringmaster searches the arena, not realizing he has walked into the act of Asbesto the Fire Walker, and is standing upon a bed of red-hot coals. The ringmaster dives for one of the side rings, where an ice-skating act is going on. The ringmaster’s hot feet are quickly cooled, but melt through the ice surface, leaving him fallen into a puddle. Sugarfoot scrambles up a ladder to a high-diving platform, then loses his balance above, falling rapidly toward the arena floor. The ringmaster, with murderous intent, pushes the waiting water tank out of the way – but quickly realizes this was a mistake, as the shadow of the descending horse envelops him. Sugarfoot lands upon him with a thud, then rises to take a bow, while the ringmaster runs around and around, crushed down into his large top hat with only his waddling feet visible below. Sugarfoot won’t share the spotlight, and gives the hat a quick kick to get the ringmaster out of the way.

Sugarfoot joins a seal act, tossing back and forth with one of the seals a large ball, balanced on their noses. The ringmaster substitutes a bomb painted to match the ball. But an errant toss from Sugarfoot places the ball-bomb upon the ringmaster’s nose, just in time for the explosion. Sugarfoot improvises his own act, performing a tap dance, first with his front feet, then his hindquarters. The crowd eats it up and the ringmaster finally visualizes in a thought cloud, ringmaster plus Sugarfoot equals a sack of box office money. The ringmaster thus again confronts Sugarfoot with the rifle – but this time, the weapon is not loaded with bullets. Instead, a flag pops out, from which a paper unrolls, reading “Big Fat Contract”. Headlines soon proclaim Sugarfoot’s box office success throughout the season, followed by a final news story about the circus bedding down for the season in winter quarters. Back at the farm, Christmas is celebrated, and the farmer and his wife wonder if they’ll ever see Sugarfoot again, now that he’s a success. A knock at the window reveals Sugarfoot looking in, followed by Starbright. “You old rascal. What have you been up to?”, asks the farmer. The answer quickly appears, in the form of a young baby colt, as the Sugarfoot family smiles together for the iris out.

Sugarfoot joins a seal act, tossing back and forth with one of the seals a large ball, balanced on their noses. The ringmaster substitutes a bomb painted to match the ball. But an errant toss from Sugarfoot places the ball-bomb upon the ringmaster’s nose, just in time for the explosion. Sugarfoot improvises his own act, performing a tap dance, first with his front feet, then his hindquarters. The crowd eats it up and the ringmaster finally visualizes in a thought cloud, ringmaster plus Sugarfoot equals a sack of box office money. The ringmaster thus again confronts Sugarfoot with the rifle – but this time, the weapon is not loaded with bullets. Instead, a flag pops out, from which a paper unrolls, reading “Big Fat Contract”. Headlines soon proclaim Sugarfoot’s box office success throughout the season, followed by a final news story about the circus bedding down for the season in winter quarters. Back at the farm, Christmas is celebrated, and the farmer and his wife wonder if they’ll ever see Sugarfoot again, now that he’s a success. A knock at the window reveals Sugarfoot looking in, followed by Starbright. “You old rascal. What have you been up to?”, asks the farmer. The answer quickly appears, in the form of a young baby colt, as the Sugarfoot family smiles together for the iris out.

The Flea Circus (MGM, 11/6/54 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Pepito’s Cirque Des Fleas might be the precursor of the modern “Cirque Du Soleil” – not your typical affair with animal acts, trapeze performers, etc., but more of a potpourri of legitimate theater – with fleas as the performers. At the Paree Theater, Pepito himself is raking in the dough at the ticket booth, while handing out magnifying glasses to the patrons. On stage, a microphone drops nearly to the stage floor to pick up the music of a 52-piece flea marching band. A team of flea acrobats pile atop each other’s shoulders to form anything from a single-file tower to an outline in the shape of a sweet young lady. A tap dancer’s rendition of “Swanee River” is cut short when he falls through a crack in the floor. A sword swallower gulps down an entire human-sized sword which disappears from view – then hiccups. A concert pianist flea plays the “Unfinished Symphony” – which remains unfinished, when he overshoots the end of the keyboard of a concert grand and falls into a spittoon. The only act that lays an egg is Francois the Clown (voiced by Bill Thompson), a flea who looks like a little big-headed human in full clown makeup and outfit, whose sour rendition of “Clementine” draws a unanimous reaction of disapproving eyebrow-drops as seen through the magnifying glasses of the observing patrons, who boo him off the stage. But now comes the most-awaited act on the program, Fifi Le Flea. In her dressing room, a pampered female flea, who looks like a miniature human can-can dancer, primps herself before a mirror in final preparation to go on. Observing her through another magnifying glass, Pepito calls her on stage, and compliments her for looking “gorgeous”. “You only tell Fifi this because it is so true”, she replies.

The Flea Circus (MGM, 11/6/54 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Pepito’s Cirque Des Fleas might be the precursor of the modern “Cirque Du Soleil” – not your typical affair with animal acts, trapeze performers, etc., but more of a potpourri of legitimate theater – with fleas as the performers. At the Paree Theater, Pepito himself is raking in the dough at the ticket booth, while handing out magnifying glasses to the patrons. On stage, a microphone drops nearly to the stage floor to pick up the music of a 52-piece flea marching band. A team of flea acrobats pile atop each other’s shoulders to form anything from a single-file tower to an outline in the shape of a sweet young lady. A tap dancer’s rendition of “Swanee River” is cut short when he falls through a crack in the floor. A sword swallower gulps down an entire human-sized sword which disappears from view – then hiccups. A concert pianist flea plays the “Unfinished Symphony” – which remains unfinished, when he overshoots the end of the keyboard of a concert grand and falls into a spittoon. The only act that lays an egg is Francois the Clown (voiced by Bill Thompson), a flea who looks like a little big-headed human in full clown makeup and outfit, whose sour rendition of “Clementine” draws a unanimous reaction of disapproving eyebrow-drops as seen through the magnifying glasses of the observing patrons, who boo him off the stage. But now comes the most-awaited act on the program, Fifi Le Flea. In her dressing room, a pampered female flea, who looks like a miniature human can-can dancer, primps herself before a mirror in final preparation to go on. Observing her through another magnifying glass, Pepito calls her on stage, and compliments her for looking “gorgeous”. “You only tell Fifi this because it is so true”, she replies.

Francois appears, and is also gaga at the way Fifi looks. He lays down his coat to let her cross a few stray drops of water backstage – but this is not enough of a gesture to get her to accept his proposal of marriage, which Fifi refuses for the umpteenth time, “No, no NO!!” Fifi leads a massive troupe of nearly identical dancing girl fleas in a mammoth production number on an elaborate miniature set, “Applause, Applause” (The song, composed by Ira Gershwin, is borrowed from the obscure MGM musical, “Give a Girl a Break”, with Marge and Gower Champion – in fact, the rendition appearing here seems to be actually looped from the soundtrack of the feature, as performed by the MGM chorus.) While the audience’s eyes grow wide in appreciation through the magnifying glasses, no one notices that the stage door has been left unattended, and a stray dog wanders into the theatre. The musical number cuts off abruptly, and the entire troupe gallops off stage, briefly forming into the letters, “Wow! A Dog!” The dog reacts in panic as the entire circus jumps onto his back – and resumes singing their song! The dog runs out the stage door into the night. Pepito stands in the stage doorway, pleading for them to come back, and facing ruination. But one flea has remained faithful – Francois. Francois promises to bring back more fleas to Pepito – somehow – and takes off in pursuit of the troupe.

Francois appears, and is also gaga at the way Fifi looks. He lays down his coat to let her cross a few stray drops of water backstage – but this is not enough of a gesture to get her to accept his proposal of marriage, which Fifi refuses for the umpteenth time, “No, no NO!!” Fifi leads a massive troupe of nearly identical dancing girl fleas in a mammoth production number on an elaborate miniature set, “Applause, Applause” (The song, composed by Ira Gershwin, is borrowed from the obscure MGM musical, “Give a Girl a Break”, with Marge and Gower Champion – in fact, the rendition appearing here seems to be actually looped from the soundtrack of the feature, as performed by the MGM chorus.) While the audience’s eyes grow wide in appreciation through the magnifying glasses, no one notices that the stage door has been left unattended, and a stray dog wanders into the theatre. The musical number cuts off abruptly, and the entire troupe gallops off stage, briefly forming into the letters, “Wow! A Dog!” The dog reacts in panic as the entire circus jumps onto his back – and resumes singing their song! The dog runs out the stage door into the night. Pepito stands in the stage doorway, pleading for them to come back, and facing ruination. But one flea has remained faithful – Francois. Francois promises to bring back more fleas to Pepito – somehow – and takes off in pursuit of the troupe.

In a Parisian park, the dog finally finds a solution to his problem – a small lake, into which he jumps. The soggy fleas all abandon ship – except for Fifi, who can’t swim, and is about to go under with the dog’s tail. On the shore arrives Francois, who quickly dives into the water and drags Fifi to safety. Assuming it to be a meaningless gesture in Fifi’s eyes, Francois bids her a sad goodbye. Instead, she follows him on bended knees, and asks him to marry her. “Vive La France!”, Francois replies, and the scene ends with a heart-shaped iris out. But that is far from the end of the story. A miniature wedding takes place at a full-sized church. Sometime later, Francois arrives home to find Fifi knitting a baby outfit with human-sized knitting needles. Next comes the maternity ward, with Francois nervously pacing in the waiting room and puffing on full-sized cigarette butts left behind by other expectant fathers. A nurse brings in a basket of the new arrivals – a swarm of black dots that extend the width of the human-sized basket. (Someone was remembering Minnie Mouse’s maternity scene in “Mickey’s Nightmare”.) The happy family leave the hospital in a black swarm that covers the stairway. Arriving back at Pepito’s, they parade in in marching formation, ten times stronger in rank than the old marching band. The show goes on again, complete with the musical production number. The film ends with one additional Avery twist. At the conclusion of the performance, Francois goes into Fifi’s dressing room, and finds her working with the knitting needles again. “No, Fifi, No!”, says Francois. Fifi gently replies, in a voice signifying her acceptance that this may become a regular habit, “Francois, Vive La France.”

In a Parisian park, the dog finally finds a solution to his problem – a small lake, into which he jumps. The soggy fleas all abandon ship – except for Fifi, who can’t swim, and is about to go under with the dog’s tail. On the shore arrives Francois, who quickly dives into the water and drags Fifi to safety. Assuming it to be a meaningless gesture in Fifi’s eyes, Francois bids her a sad goodbye. Instead, she follows him on bended knees, and asks him to marry her. “Vive La France!”, Francois replies, and the scene ends with a heart-shaped iris out. But that is far from the end of the story. A miniature wedding takes place at a full-sized church. Sometime later, Francois arrives home to find Fifi knitting a baby outfit with human-sized knitting needles. Next comes the maternity ward, with Francois nervously pacing in the waiting room and puffing on full-sized cigarette butts left behind by other expectant fathers. A nurse brings in a basket of the new arrivals – a swarm of black dots that extend the width of the human-sized basket. (Someone was remembering Minnie Mouse’s maternity scene in “Mickey’s Nightmare”.) The happy family leave the hospital in a black swarm that covers the stairway. Arriving back at Pepito’s, they parade in in marching formation, ten times stronger in rank than the old marching band. The show goes on again, complete with the musical production number. The film ends with one additional Avery twist. At the conclusion of the performance, Francois goes into Fifi’s dressing room, and finds her working with the knitting needles again. “No, Fifi, No!”, says Francois. Fifi gently replies, in a voice signifying her acceptance that this may become a regular habit, “Francois, Vive La France.”

Tweety’s Circus (Warner, Tweety and Sylvester, 6/4/55 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Sylvester, in his jaunts along back fences, encounters a circus before opening time, and drops in for a look-see. Touring the menagerie, he finds a cage marked, “Lion – King of Beasts”. Taking this personally, Sylvester replies, “Well, you’re not my king”, and responds to the lion’s powerful roar by “crowning” the king on the head with a whack from a long pole. To add insult to injury, Sylvester spits and slashes his paw at the lion at a safe distance from the cage bars. He then continues his menagerie tour, finding amidst the cages of the usual tigers, elephants, camels, etc. the rare – Tweety Bird? Tweety did “taw” a “putty tat”, and the usual chase is on as Sylvester flings open the cage door. Sylvester grabs up a roustabout’s stake-driving mallet, and pursues Tweety through a wall of metal bars – straight into the back entrance of the lion’s cage. Coming face to face with the beast, Sylvester tries to defend himself by bopping the lion on the head with the mallet – but his blows repeatedly have absolutely no effect. The lion turns the tables by grabbing the mallet, and driving Sylvester into the ground like he was just another wooden stake.

Tweety’s Circus (Warner, Tweety and Sylvester, 6/4/55 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Sylvester, in his jaunts along back fences, encounters a circus before opening time, and drops in for a look-see. Touring the menagerie, he finds a cage marked, “Lion – King of Beasts”. Taking this personally, Sylvester replies, “Well, you’re not my king”, and responds to the lion’s powerful roar by “crowning” the king on the head with a whack from a long pole. To add insult to injury, Sylvester spits and slashes his paw at the lion at a safe distance from the cage bars. He then continues his menagerie tour, finding amidst the cages of the usual tigers, elephants, camels, etc. the rare – Tweety Bird? Tweety did “taw” a “putty tat”, and the usual chase is on as Sylvester flings open the cage door. Sylvester grabs up a roustabout’s stake-driving mallet, and pursues Tweety through a wall of metal bars – straight into the back entrance of the lion’s cage. Coming face to face with the beast, Sylvester tries to defend himself by bopping the lion on the head with the mallet – but his blows repeatedly have absolutely no effect. The lion turns the tables by grabbing the mallet, and driving Sylvester into the ground like he was just another wooden stake.

Tweety runs into what appears to be one of several loops of gray fire hose – except his stretch of “hose” is really the trunk of an elephant. The elephant tosses Sylvester over his shoulder, sliding him right back into the lion’s cage again. Sylvester grabs up a chair and whip, but the lion again turns things his way, grabbing them away, and using them in return upon Sylvester. Sylvester races out of the cage bars one step ahead of the whip’s lash, but a swipe from the lion’s mighty claws slashes Sylvester into four sections, which fall away one by one as he attempts to walk away. Pulling himself together, Sylvester next pursues Tweety up to a high-diving platform. Tweety jumps, safely landing in the water tank below. Before Sylvester can follow, Tweety treats the elephant to a nice long drink – emptying the water tank. Sylvester is left to pursue Tweety with the cat’s front side smashed flat. Tweety flings open the door of the lion’s cage, and lets the beast loose. Sylvester ducks for cover behind the sideshow booth of Flamo the fire eater. When he rises from behind the booth, he is disguised in a turban. Spotting him, the lion suspects him to be a fraud, and calmly leans on the booth with stern countenance, briefly turning to Flamo’s banner above the booth to remind Sylvester of who he is supposed to be. Sylvester grins nervously, realizing he’s going to have to go through with this bit to convince the skeptical lion. Sylvester ignites a stick from a fire kettle, then swallows it, posing for a nervous “Ta daah”. Begrudgingly satisfied, the lion walks away. Sylvester begins to smell smoke, and when he looks down, finds the fur on his lower half burning away and in flames. He jumps into another tank of water to put the fire out, but the elephant is thirsty again, and once more drains the tank dry, revealing the crouching Sylvester to the lion’s view. Sylvester returns to the ladder to the high-diving platform for an escape. Tweety is already up there, and instead of repeating the diving trick, hops onto the high wire.

Tweety runs into what appears to be one of several loops of gray fire hose – except his stretch of “hose” is really the trunk of an elephant. The elephant tosses Sylvester over his shoulder, sliding him right back into the lion’s cage again. Sylvester grabs up a chair and whip, but the lion again turns things his way, grabbing them away, and using them in return upon Sylvester. Sylvester races out of the cage bars one step ahead of the whip’s lash, but a swipe from the lion’s mighty claws slashes Sylvester into four sections, which fall away one by one as he attempts to walk away. Pulling himself together, Sylvester next pursues Tweety up to a high-diving platform. Tweety jumps, safely landing in the water tank below. Before Sylvester can follow, Tweety treats the elephant to a nice long drink – emptying the water tank. Sylvester is left to pursue Tweety with the cat’s front side smashed flat. Tweety flings open the door of the lion’s cage, and lets the beast loose. Sylvester ducks for cover behind the sideshow booth of Flamo the fire eater. When he rises from behind the booth, he is disguised in a turban. Spotting him, the lion suspects him to be a fraud, and calmly leans on the booth with stern countenance, briefly turning to Flamo’s banner above the booth to remind Sylvester of who he is supposed to be. Sylvester grins nervously, realizing he’s going to have to go through with this bit to convince the skeptical lion. Sylvester ignites a stick from a fire kettle, then swallows it, posing for a nervous “Ta daah”. Begrudgingly satisfied, the lion walks away. Sylvester begins to smell smoke, and when he looks down, finds the fur on his lower half burning away and in flames. He jumps into another tank of water to put the fire out, but the elephant is thirsty again, and once more drains the tank dry, revealing the crouching Sylvester to the lion’s view. Sylvester returns to the ladder to the high-diving platform for an escape. Tweety is already up there, and instead of repeating the diving trick, hops onto the high wire.

Sylvester is unsure of his balance to follow Tweety, so finds a balance pole to steady himself, stepping out onto the wire. But Tweety is no longer ahead of him. Instead, Tweety has somehow obtained a perch on one tip of Sylvester’s balance pole. Sylvester lays the pole down upon the wire, carefully centering it to balance against Tweety’s weight. He then attempts to climb out upon the pole after Tweety, but has failed to reckon on the displacement of his own body weight, as the pole tips violently. Scrambling back to center point, Sylvester leaves the wire momentarily, then returns with an armload of bricks. He tosses them onto the short side of the pole as he hops onto the side with Tweety, obtaining a shaky counterbalance. With great care, he reaches the end of the pole where Tweety stands, grabbing up the bird in his paw. But who should appear on the platform but the lion, giving Sylvester a stern look of disapproval. Sylvester releases Tweety to appease the lion’s objection, but the lion still has scores to settle, and kicks the bricks off the other end of the pole. Sylvester desperately grabs at Tweety’s tail feathers, but the little bird is inadequate to keep him aloft. The lion races down the ladder, and is waiting as Sylvester lands – directly in the lion’s mouth, being nearly swallowed. Sylvester pries open the jagged jaws from inside, and races for the gate of another cage, opening it to gain entrance, then shutting the gate behind him. Sylvester takes hold of the gate’s key, and swallows it as extra safety insurance, remarking, “Well, that solves my lion problem.” Not quite, as he has just entered an enclosure where dozens more of the beasts are caged, all with their eyes on him. We do not see the aftermath of this turn of events, but are only clued into them by Tweety, who assumes the role of a barker at the front entrance as the crowds finally arrive. “Huwwy, huwwy, huwwy! Step wight up. The gweatest show on Earth. Fifty wions and a putty tat!” A loud chorus of roars is heard from inside the tent, then dies away, as Tweety looks back to observe, then changes his barker spiel to just “Fifty wins! Count ‘em, fifty wins!”

Sylvester is unsure of his balance to follow Tweety, so finds a balance pole to steady himself, stepping out onto the wire. But Tweety is no longer ahead of him. Instead, Tweety has somehow obtained a perch on one tip of Sylvester’s balance pole. Sylvester lays the pole down upon the wire, carefully centering it to balance against Tweety’s weight. He then attempts to climb out upon the pole after Tweety, but has failed to reckon on the displacement of his own body weight, as the pole tips violently. Scrambling back to center point, Sylvester leaves the wire momentarily, then returns with an armload of bricks. He tosses them onto the short side of the pole as he hops onto the side with Tweety, obtaining a shaky counterbalance. With great care, he reaches the end of the pole where Tweety stands, grabbing up the bird in his paw. But who should appear on the platform but the lion, giving Sylvester a stern look of disapproval. Sylvester releases Tweety to appease the lion’s objection, but the lion still has scores to settle, and kicks the bricks off the other end of the pole. Sylvester desperately grabs at Tweety’s tail feathers, but the little bird is inadequate to keep him aloft. The lion races down the ladder, and is waiting as Sylvester lands – directly in the lion’s mouth, being nearly swallowed. Sylvester pries open the jagged jaws from inside, and races for the gate of another cage, opening it to gain entrance, then shutting the gate behind him. Sylvester takes hold of the gate’s key, and swallows it as extra safety insurance, remarking, “Well, that solves my lion problem.” Not quite, as he has just entered an enclosure where dozens more of the beasts are caged, all with their eyes on him. We do not see the aftermath of this turn of events, but are only clued into them by Tweety, who assumes the role of a barker at the front entrance as the crowds finally arrive. “Huwwy, huwwy, huwwy! Step wight up. The gweatest show on Earth. Fifty wions and a putty tat!” A loud chorus of roars is heard from inside the tent, then dies away, as Tweety looks back to observe, then changes his barker spiel to just “Fifty wins! Count ‘em, fifty wins!”

Mouse Trapeze (Paramount/Famous, Herman and Katnip, 8/5/55 – I, Sparber, dir.) – Arnold Stang does not appear to have made the recording date for this film (which seemed to occur for a couple of episodes around this time), as Herman’s voice is much more gravelly than usual, though the timing of the read seems a good impression of Stang. Herman and three nephews are attempting to take in a circus, but arrive too late, just as the crowds are leaving the performance. So the kids won’t be disappointed, Herman, who claims to have been previously known as Herman the Great, volunteers to put on a one-man show. Obtaining a mouse-sized acrobat outfit from nowhere, Herman begins an act on the high wire, walking upon his fingertips while juggling with his free hand and feet. Enter Katnip, scrounging around the trash cans outside, who overhears the kids’ cheers for Herman. Spotting the outfit of a hot dog vendor left hanging on a hook, Katnip appears inside the tent in disguise, carrying a large wicker basket to peddle his wares. The kids call for hot dogs, ice cream and candy, and Katnip opens one flap of the basket, saying “Help yourselves.” As the little mice leap in, Katnip slams the flap shut – but the kids merely pop out the other flap and make an escape behind Katnip’s back. Herman spots the commotion below, and jumps hard upon the wire, stretching it momentarily to the ground. It intercepts the passing Katnip’s midriff, and Herman jumps off, causing the wire to spring back, lifting and bouncing Katnip against the tent roof. Katnip falls, and lands hard on Herman, briefly stunning both contenders, who lay on the ground exhausted, then open their eyes, looking each other nose to nose. Herman runs, and Katnip pursues him with a lion tamer’s whip, wrapping the end of it around Herman’s neck. But the resourceful mouse turns the tables as he is hauled in by the cat, using his own flexible tail as a mini-whip, to score a painful lash across Katnip’s nose.

Mouse Trapeze (Paramount/Famous, Herman and Katnip, 8/5/55 – I, Sparber, dir.) – Arnold Stang does not appear to have made the recording date for this film (which seemed to occur for a couple of episodes around this time), as Herman’s voice is much more gravelly than usual, though the timing of the read seems a good impression of Stang. Herman and three nephews are attempting to take in a circus, but arrive too late, just as the crowds are leaving the performance. So the kids won’t be disappointed, Herman, who claims to have been previously known as Herman the Great, volunteers to put on a one-man show. Obtaining a mouse-sized acrobat outfit from nowhere, Herman begins an act on the high wire, walking upon his fingertips while juggling with his free hand and feet. Enter Katnip, scrounging around the trash cans outside, who overhears the kids’ cheers for Herman. Spotting the outfit of a hot dog vendor left hanging on a hook, Katnip appears inside the tent in disguise, carrying a large wicker basket to peddle his wares. The kids call for hot dogs, ice cream and candy, and Katnip opens one flap of the basket, saying “Help yourselves.” As the little mice leap in, Katnip slams the flap shut – but the kids merely pop out the other flap and make an escape behind Katnip’s back. Herman spots the commotion below, and jumps hard upon the wire, stretching it momentarily to the ground. It intercepts the passing Katnip’s midriff, and Herman jumps off, causing the wire to spring back, lifting and bouncing Katnip against the tent roof. Katnip falls, and lands hard on Herman, briefly stunning both contenders, who lay on the ground exhausted, then open their eyes, looking each other nose to nose. Herman runs, and Katnip pursues him with a lion tamer’s whip, wrapping the end of it around Herman’s neck. But the resourceful mouse turns the tables as he is hauled in by the cat, using his own flexible tail as a mini-whip, to score a painful lash across Katnip’s nose.

Herman vows to the kids that the show must go on, deciding to draw Katnip into the act. He leads Katnip in a chase up a ladder to a “Slide For Life” platform, where Katnip steps out onto the seat of a tall unicycle on a wire. The unicycle rolls down to the ground, then gets wrapped around a tent pole, with its wheel turned sideways and still spinning violently. Katnip is tossed into the air, then falls amid the wheel’s spinning spokes, which neatly slice him into patties like a food processer. Herman next plays a game of hide-and-seek with Katnip among a set of seal’s horns, causing Katnip to perform a seal’s tune in attempt to blow Herman out of the horns’ bells. Katnip’s last blow meets with a surprise, as Herman hooks up the hose of a fire hydrant in the horn’s other end, filling Katnip with water. Once full, Katnip is blasted backwards by the hose’s force, landing with his back pressed against the backside of the target board of a knife-throwing act, where the protruding tips of knives from the board cause enough puncture holes in Katnip’s back to produce a water fountain from the pent-up water within Katnip. Herman adds his own touch to the fountain, by tossing several ping-pong balls atop each water spray from Katnip’s back, then performing a sharp-shooting act of shooting the balls away one-by-one with a pistol, aiming the weapon over his shoulder with the aid of a mirror. Karnip revives, and chases Herman onto a trampoline. Herman pulls a simpler version of Woody Woodpecker’s stunt from “What’s Sweepin’”, placing a giant pin under the spot where Katnip lands. Katnip soars into the air in pain, and Herman climbs to catch him from a trapeze bar, then swings the cat by the tail up to a high diving platform, with Katnip landing upside down on his head atop the diving board. For a finish, Herman fills the tank below with quick-drying cement, so that when Katnip topples, he is caught tight in a permanent splash of cement from the rank, only his head remaining free. No curtain line or topper – just Herman taking his bows for the fade out.

Herman vows to the kids that the show must go on, deciding to draw Katnip into the act. He leads Katnip in a chase up a ladder to a “Slide For Life” platform, where Katnip steps out onto the seat of a tall unicycle on a wire. The unicycle rolls down to the ground, then gets wrapped around a tent pole, with its wheel turned sideways and still spinning violently. Katnip is tossed into the air, then falls amid the wheel’s spinning spokes, which neatly slice him into patties like a food processer. Herman next plays a game of hide-and-seek with Katnip among a set of seal’s horns, causing Katnip to perform a seal’s tune in attempt to blow Herman out of the horns’ bells. Katnip’s last blow meets with a surprise, as Herman hooks up the hose of a fire hydrant in the horn’s other end, filling Katnip with water. Once full, Katnip is blasted backwards by the hose’s force, landing with his back pressed against the backside of the target board of a knife-throwing act, where the protruding tips of knives from the board cause enough puncture holes in Katnip’s back to produce a water fountain from the pent-up water within Katnip. Herman adds his own touch to the fountain, by tossing several ping-pong balls atop each water spray from Katnip’s back, then performing a sharp-shooting act of shooting the balls away one-by-one with a pistol, aiming the weapon over his shoulder with the aid of a mirror. Karnip revives, and chases Herman onto a trampoline. Herman pulls a simpler version of Woody Woodpecker’s stunt from “What’s Sweepin’”, placing a giant pin under the spot where Katnip lands. Katnip soars into the air in pain, and Herman climbs to catch him from a trapeze bar, then swings the cat by the tail up to a high diving platform, with Katnip landing upside down on his head atop the diving board. For a finish, Herman fills the tank below with quick-drying cement, so that when Katnip topples, he is caught tight in a permanent splash of cement from the rank, only his head remaining free. No curtain line or topper – just Herman taking his bows for the fade out.

Boo Kind To Animals (Paramount/Famous, Casper, 12/23/55 – I. Sparber. dir.) – A Casper crossover, allowing the spirited spirit to meet up with an old blast from the past – Spunky the mule, who had not been seen on the screen since the wartime “Yankee Doodle Donkey”. This of course was not the only time that Casper was allowed to meet a character from the Fleischer stable, as many have noted that King Luna in “Boo Moon” is a dead ringer for King Bombo from “Gulliver’s Travels”. I wonder how Casper and Grampy might have gotten along? In a scene looking like it was lifted from any number of Fleischer films (“Be Kind To Aminals”, “Be Human”, or “A Kick In Time”), Spunky is first sighted by Casper pulling solo an overloaded hay wagon deserving a team of full-grown mules to be pulled practically, with the driver cruelly cracking the whip behind him. Casper intercedes, sending the driver running, carrying the haystack on his own back. Casper unhitches Spunky, and promises to find him an easier job.

Boo Kind To Animals (Paramount/Famous, Casper, 12/23/55 – I. Sparber. dir.) – A Casper crossover, allowing the spirited spirit to meet up with an old blast from the past – Spunky the mule, who had not been seen on the screen since the wartime “Yankee Doodle Donkey”. This of course was not the only time that Casper was allowed to meet a character from the Fleischer stable, as many have noted that King Luna in “Boo Moon” is a dead ringer for King Bombo from “Gulliver’s Travels”. I wonder how Casper and Grampy might have gotten along? In a scene looking like it was lifted from any number of Fleischer films (“Be Kind To Aminals”, “Be Human”, or “A Kick In Time”), Spunky is first sighted by Casper pulling solo an overloaded hay wagon deserving a team of full-grown mules to be pulled practically, with the driver cruelly cracking the whip behind him. Casper intercedes, sending the driver running, carrying the haystack on his own back. Casper unhitches Spunky, and promises to find him an easier job.

The first employment opportunity presents itself in the form of a kiddie photographer, who is about to lose a business opportunity because his child subject insists he wants to be photographed atop a pony. At Casper’s coaxing, Spunky slips up behind the boy, picks him up upon his nose, and flips him onto Spunky’s back. The photographer is pleased at this surprise, and prepares to take the pose, warning the child not to be afraid of the flash. However, Spunky doesn’t get the same message, rearing up in fear as the flash powder ignites, ejecting the boy from his back and also knocking down the camera tripod with a kick. The photographer prepares to vent his anger on Spunky, but Casper again has his say. The photographer flees, and so does the camera on its own tripod legs. Casper and Spunky next both get jobs as clowns in a circus. Casper dons white makeup over his ghostly ectoplasm so as not to let on as to his true identity, while Spunky wears a pointed clown’s hat. The two perform a bareback riding act in the center ring, with Casper adding his own touch of balancing atop Spunky in a handstand, then leaping into the air as Spunky circles the ring, Casper floating in air but pretending he is propelling himself by flipping his clown shoes like wings. Then Spunky jumps atop a large ball, and rolls it up a ramp. The act needs more rehearsal, as no one has taught Spunky how to roll down the other side. Losing his footing, the donkey collides with a strong man balancing a tall stack of chairs, making a mess of his performance. Spunky gets the boot, this time without Casper making a scare due to his clown makeup.

The first employment opportunity presents itself in the form of a kiddie photographer, who is about to lose a business opportunity because his child subject insists he wants to be photographed atop a pony. At Casper’s coaxing, Spunky slips up behind the boy, picks him up upon his nose, and flips him onto Spunky’s back. The photographer is pleased at this surprise, and prepares to take the pose, warning the child not to be afraid of the flash. However, Spunky doesn’t get the same message, rearing up in fear as the flash powder ignites, ejecting the boy from his back and also knocking down the camera tripod with a kick. The photographer prepares to vent his anger on Spunky, but Casper again has his say. The photographer flees, and so does the camera on its own tripod legs. Casper and Spunky next both get jobs as clowns in a circus. Casper dons white makeup over his ghostly ectoplasm so as not to let on as to his true identity, while Spunky wears a pointed clown’s hat. The two perform a bareback riding act in the center ring, with Casper adding his own touch of balancing atop Spunky in a handstand, then leaping into the air as Spunky circles the ring, Casper floating in air but pretending he is propelling himself by flipping his clown shoes like wings. Then Spunky jumps atop a large ball, and rolls it up a ramp. The act needs more rehearsal, as no one has taught Spunky how to roll down the other side. Losing his footing, the donkey collides with a strong man balancing a tall stack of chairs, making a mess of his performance. Spunky gets the boot, this time without Casper making a scare due to his clown makeup.

A third employment opportunity arises at an Army recruiting post, where army mules are being inducted, with no experience necessary. However, the recruiting sergeant merely laughs at the sight of puny Spunky, insisting that he is too young to enlist. As the dejected donkey sulks outside the recruiting station, while Casper continues to encourage him to keep trying, a mule and wagon hauling an artillery piece pass in front of the station. The mule gets a look at Casper, and hee-haws in panic, racing off down a road with his driver and wagon in tow. They head right into a restricted area where war games are in progress, and a cannon blast knocks apart the wagon, leaving its driver injured and unconscious on the ground. (See, folks? Casper is a menace to society. Somebody really got hurt.) Spunky bravely races into the war games area to rescue the fallen man, attempting to drag him by his uniform to safety. However, Casper spots a sign behind Spunky which the donkey does not see: “Mine Field”. “They’ll be blown to bits”, shouts Casper. Instead of flying to warn Spunky, Casper takes a more direct approach to the problem, diving down into the ground. As Spunky slowly pulls the wounded soldier along, Casper’s hand emerges at intervals from the ground behind him, pushing up and out of Spunky’s path mine after mine, clearing the way so that Spunky is able to tow the soldier to a field hospital. The military brass, having no knowledge of Casper’s intervention, honor Spunky’s bravery by accepting him for a position as a field medic, towing a small cart of stretchers and wearing a horse blanket with a red cross upon it. Spunky passes a reviewing station in a parade, and Casper appears from the barrel of a cannon in the next wagon ahead of him, to give Spunky a military salute, which Spunky returns by way of cocking one of his long ears. (Let’s just hope, for the soldiers’ sake, that Casper sticks around, in case of the next mine field.)

A third employment opportunity arises at an Army recruiting post, where army mules are being inducted, with no experience necessary. However, the recruiting sergeant merely laughs at the sight of puny Spunky, insisting that he is too young to enlist. As the dejected donkey sulks outside the recruiting station, while Casper continues to encourage him to keep trying, a mule and wagon hauling an artillery piece pass in front of the station. The mule gets a look at Casper, and hee-haws in panic, racing off down a road with his driver and wagon in tow. They head right into a restricted area where war games are in progress, and a cannon blast knocks apart the wagon, leaving its driver injured and unconscious on the ground. (See, folks? Casper is a menace to society. Somebody really got hurt.) Spunky bravely races into the war games area to rescue the fallen man, attempting to drag him by his uniform to safety. However, Casper spots a sign behind Spunky which the donkey does not see: “Mine Field”. “They’ll be blown to bits”, shouts Casper. Instead of flying to warn Spunky, Casper takes a more direct approach to the problem, diving down into the ground. As Spunky slowly pulls the wounded soldier along, Casper’s hand emerges at intervals from the ground behind him, pushing up and out of Spunky’s path mine after mine, clearing the way so that Spunky is able to tow the soldier to a field hospital. The military brass, having no knowledge of Casper’s intervention, honor Spunky’s bravery by accepting him for a position as a field medic, towing a small cart of stretchers and wearing a horse blanket with a red cross upon it. Spunky passes a reviewing station in a parade, and Casper appears from the barrel of a cannon in the next wagon ahead of him, to give Spunky a military salute, which Spunky returns by way of cocking one of his long ears. (Let’s just hope, for the soldiers’ sake, that Casper sticks around, in case of the next mine field.)

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Will you be looking at the 1993 Amblinmation feature ‘We’re Back! A Dinosaur’s Story’ when you get to the 1990s?

Strictly speaking, Ira Gershwin didn’t compose “Applause, Applause”. He wrote those wonderfully clever lyrics, while Burton Lane composed the music. Lane and Gershwin didn’t get along, and the MGM musical “Give a Girl a Break” was their only collaboration. And yes, the excerpt used in the cartoon was taken directly from the film’s soundtrack, where the song serves as the big opening musical number.

In 1966 the Hollies recorded “Fifi the Flea”: “Fifi the flea fell in love with a clown from a flea circus fair….” Their romance doesn’t end happily, but if that song wasn’t inspired by the Tex Avery cartoon, it’s certainly an amazing coincidence.

The “Unfinished Symphony” performed by “Le Concert Pianist” is actually the first two bars of Franz Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major. Liszt did eventually finish composing it, but it took him over twenty years.

“Tweety’s Circus” has mounted placards touting performers called “Flamo the Fire Eater” and “Krinko the Great”. Evidently those were actual people. Daniel P. Mannix, who later wrote the book that Disney adapted into “The Fox and the Hound”, spent the 1930s working as a sword swallower and fire eater in a travelling sideshow. In the late 1940s he wrote a series of articles for Collier’s magazine about his experiences; these were collected and expanded into his 1951 book “Step Right Up!”, which begins with the following sentence: “I probably never would have become America’s leading fire eater if Flamo the Great hadn’t happened to explode that night in front of Krinko’s Great Combined Carnival Side Shows.” It seems likely that Warren Foster read that book or Mannix’s earlier magazine articles. If he didn’t… well, then that’s another amazing coincidence.

“Boo Kind to Animals” fails to distinguish between mules and donkeys (and at one point even conflates Spunky with a pony). A mule is the offspring of a jackass (male donkey) and a mare (female horse). Spunky’s mother, Hunky, as seen in far too many Fleischer Color Classics, is clearly not a mare but a jenny (female donkey). If Spunky’s unknown father were a stallion, that would make him a hinny, not a mule. But whether he’s a half-breed hinny or a total jackass, it would have no bearing on Spunky’s eligibility for military service. After all, he was able to serve in the Army Canine Corps in “Yankee Doodle Donkey” thanks to his immunity to flea bites.

How would Casper and Grampy get along? Well, first of all, Betty would probably call Grampy on the phone and say: “Grampy, I just saw a ghost! What are you gonna do?” Then Grampy would put on his electric mortarboard and ponder the matter for a while. Then the bulb on his mortarboard would light up, and Grampy would dance and laugh and spin around the room. Then he’d build a proton pack ghostbusting gun out of odds and ends in his kitchen and use it to trap Casper in its particle stream before imprisoning the ghost in a box for all eternity. “But I only wanted to make friends!” “Boop a doop a doop a doop, boop oop a doop!”

This may be a stretch, but maybe Casper was the ghost of Grampy (who after all wouldn’t have been known as Grampy his whole life), regressed in death to a more childlike state. That would explain Casper’s frequent ingenuity. To digress for a minute, I’ve always thought that Louise in the Herman and Katnip “Of Mice and Magic” was Betty Boop reincarnated as a 1950s mouse. And there are suggestions of Koko in “Jolly the Clown,” which will undoubtedly be featured in next week’s batch of circus-themed cartoons. (Jolly squeaks instead of speaks, a subliminal reference to Koko’s having been a silent cartoon star.) It’s those Fleischer echoes that make the Famous cartoons more bearable than they’d be otherwise.

No. Grampy never would have had trouble making friends.

In “Wise Quacks” (Terrytoons/Fox, Dinky Duck, 27/2/53 — Mannie Davis, dir.) — not to be confused with the 1939 cartoon of the same title starring Daffy and Porky — Dinky dreams of being a great singer, even though the only sound he can make is “Quack.” The other woodland creatures laugh at him, and his mother scolds him for wanting to be something he’s not. Sulking by a pond, Dinky wishes he could sing — and lo and behold, a fairy emerges from a lotus flower and grants his wish. Now the woodland animals who once mocked him are swooning at the sound of his voice. A fast-talking fox comes along, offers to be Dinky’s agent and make him rich. Dinky’s mother tries to keep him at home; but, dreaming of stardom, Dinky follows the fox to the city.

Next we’re at a circus, where Dinky is billed as “Dinky the Wonder Duck — He sings! He croons!” However, like Stromboli with Pinocchio, the fox now has Dinky locked up in a tiny birdcage, forces him to perform, and keeps all the proceeds for himself. After touring with the circus, Dinky is ready for the big time: Kornygee Hall! But Dinky is miserable backstage, crying in his birdcage. “I wish I was an ordinary duck again!” he wails. “I’m sorry I ever asked for a voice!” The fairy reappears and grants Dinky’s wish.

Now the fox, resplendent in a tuxedo, takes Dinky onstage, bird cage and all. “You’d better sing your best tonight, or else!” threatens the fox as the orchestra tunes up, making a slashing motion across his throat with his baton. After a brief orchestral introduction, Dinky raises his voice — but all he can say now is “quack quack quack.” The audience boos, and pelts the fox with rotten vegetables. The fox grabs the birdcage and flees, but is knocked off his feet by a well-aimed tomato; he drops the birdcage, which hits the floor and bursts open, freeing Dinky. Dinky runs out of the hall as the audience members storm the stage and beat the living daylights out of the fox with heavy sticks. In the end Dinky returns home to his mother, now content to be a normal duck.