Today’s batch of titles from the mid 1930‘s take up the subject of flying on a sometimes smaller scale – several literally scaling down the action to the world of toys, while others present full size aircraft in roles more incidental to their story plotlines. Yet amidst them, animal aviators continue to occasionally strive for distance and endurance records to exotic lands, providing an overall varied bag of offerings to raise the eyes ever skyward, and the eyebrows in surprise.

Just barely out of the holiday season, we begin with honorable mentions for two Christmas cartoon classics. Max Fleischer’s Parade of the Wooden Soldiers (Paramount, Betty Boop, 12/1/33 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Seymour Kneitel/William Henning, anim. – featuring Rubinoff and his Orchestra, of fame from his association with Eddie Cantor on radio’s Chase and Sanborn Show), casts Betty as the masterpiece of all toy creation – a mechanical doll, which took five toy factories’ combined labor to produce (deflating each production plant like an exhausted balloon when the work was through). Even the shipping process gives Betty the red-carpet treatment, transitioning from delivery truck to locomotive to aerial delivery from a six-engine China Clipper! The box she is packaged in is dropped from the plane by parachute, and the tall chimney of the toy store below has to compensate for inaccurate marksmanship by disconnecting from the building and hopping about ten feet to catch the falling chute, then re-attach itself to the building. It looks like Betty is still in hot water, as there is a roaring fire blazing in the hearth below – but the flames leap out of the hearth, parting into two columns to leave an entry path for the descending package, and take graceful low bows as the package tumbles into the store, to welcome their distinguished guest. (With all this pomp and ceremony, you’d have thought this film could have been the greatest commercial of all time for the sale of real Betty Boop dolls, if Paramount’s marketing department had thought to fully exploit its possibilities.)

The Fleischers pull out all the stops on this production, with marvelous animation coming as close to matching the spectacle of Disney’s Santa’s Workshop toy parade as the New York artists could manage. Unusual and interesting camera angles abound, including 3D tracking shots, hand-drawn full frame camera pullbacks, a toy railroad tunnel ornately detailed for a frame-by-frame pan attempting to change its details dimensionally from the viewpoint of the passing camera, and a wonderfully smooth rag doll dance using a combination of hand-drawn and rotoscoped effects. In another complex and incredibly smooth shot, a toy autogyro, with attachment of a clamshell construction bucket of the type found on toy cranes, picks up a hefty load of lettered blocks, rises to the ceiling of the shop, and releases the blocks, which fall with precision to form a massive queen’s throne for Betty, complete with her name spelled in blocks around the perimeter.

The Fleischers pull out all the stops on this production, with marvelous animation coming as close to matching the spectacle of Disney’s Santa’s Workshop toy parade as the New York artists could manage. Unusual and interesting camera angles abound, including 3D tracking shots, hand-drawn full frame camera pullbacks, a toy railroad tunnel ornately detailed for a frame-by-frame pan attempting to change its details dimensionally from the viewpoint of the passing camera, and a wonderfully smooth rag doll dance using a combination of hand-drawn and rotoscoped effects. In another complex and incredibly smooth shot, a toy autogyro, with attachment of a clamshell construction bucket of the type found on toy cranes, picks up a hefty load of lettered blocks, rises to the ceiling of the shop, and releases the blocks, which fall with precision to form a massive queen’s throne for Betty, complete with her name spelled in blocks around the perimeter.

Of course, a Betty epic isn’t complete without a villain, which is provided when the toy soldiers begin launching skyrockets in celebration of Betty’s coronation, awakening a large rag-doll gorilla. (After all, this was the year of King Kong.) The beast begins destructively lumbering around the shop, stomping on any toy in its path, and pointlessly knocking others from their shelves. Spotting some stereotypic ethnic negro and Chinese dolls, the ape creates a pastime by pulling off their heads and replacing them with the heads of other dolls (such as that of an elephant). But he seeks a more perfect head, and, spying Betty, imagines her cranium as ideal. Climbing to the top shelf of the shop, the gorilla uses a toy crane to snag Betty from her throne below, and carries her to a buzzsaw device to behead her. (What exactly is a buzzsaw doing in this toy shop?) The toy soldier army springs into action, launching a squadron of toy planes in the process of their rescue attempts. In an elaborate and destructive battle, the villain of course takes it on the chin, and the air forces have the last say, by launching two planes carrying between them a set of weighted ropes, much like the Argentine bolas (See the kind of knowledge you can pick up from watching “El Gaucho Goofy”?), which spiral around the gorilla in opposite directions, tying him up in a confining coil of rope. Boop concludes the film by leading a victory parade of the now battered toys, many carrying crutches, bandages, and makeshift substitute parts. Betty herself didn’t come out unscathed from her encounter with the buzzsaw, as a turn reveals that the back of her dress is missing, exposing her usual undies. She and the other toys finally drop and come to a halt upon the toy counter as the final notes of military music are played, below a new sign reading: “Sale – Damaged Toys”. (This closing is notably mimicked by a Disney Silly Symphony of the following year, “The China Shop”, where the battled-ravaged china figures are made marketable again by advertising them as “Antiques”, at double their original prices!) A true Fleischer masterpiece!

Of course, a Betty epic isn’t complete without a villain, which is provided when the toy soldiers begin launching skyrockets in celebration of Betty’s coronation, awakening a large rag-doll gorilla. (After all, this was the year of King Kong.) The beast begins destructively lumbering around the shop, stomping on any toy in its path, and pointlessly knocking others from their shelves. Spotting some stereotypic ethnic negro and Chinese dolls, the ape creates a pastime by pulling off their heads and replacing them with the heads of other dolls (such as that of an elephant). But he seeks a more perfect head, and, spying Betty, imagines her cranium as ideal. Climbing to the top shelf of the shop, the gorilla uses a toy crane to snag Betty from her throne below, and carries her to a buzzsaw device to behead her. (What exactly is a buzzsaw doing in this toy shop?) The toy soldier army springs into action, launching a squadron of toy planes in the process of their rescue attempts. In an elaborate and destructive battle, the villain of course takes it on the chin, and the air forces have the last say, by launching two planes carrying between them a set of weighted ropes, much like the Argentine bolas (See the kind of knowledge you can pick up from watching “El Gaucho Goofy”?), which spiral around the gorilla in opposite directions, tying him up in a confining coil of rope. Boop concludes the film by leading a victory parade of the now battered toys, many carrying crutches, bandages, and makeshift substitute parts. Betty herself didn’t come out unscathed from her encounter with the buzzsaw, as a turn reveals that the back of her dress is missing, exposing her usual undies. She and the other toys finally drop and come to a halt upon the toy counter as the final notes of military music are played, below a new sign reading: “Sale – Damaged Toys”. (This closing is notably mimicked by a Disney Silly Symphony of the following year, “The China Shop”, where the battled-ravaged china figures are made marketable again by advertising them as “Antiques”, at double their original prices!) A true Fleischer masterpiece!

Disney’s The Night Before Christmas (United Artists, Silly Symphony, 12/9/33, Wilfred Jackson, dir.), the direct sequel to “Santa’s Workshop” of the preceding year, exhibits possibly even greater sophistication and complexity of animation than its predecessor, plus more heart. The film again features a tip of the cap to aviation, in the form of a flying feat by a wind-up toy dirigible (a toymaking accomplishment I’d challenge anyone to duplicate in the real world), which suspensefully circles the Christmas tree to gain altitude, then successfully launches and plants the star in a bulls-eye exhibition of precision bombing atop the tree. I’ll bet the U.S. Navy aircrews of the day could have never pulled off such a shot – and without even breaking the glass ornament.

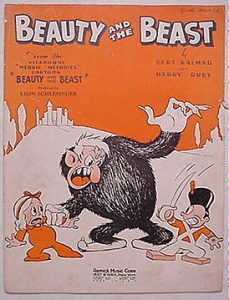

Beauty and the Beast (Warner, Merrie Melodies (2-strip Cinecolor), 4/14/34, Isadore (Friz) Freleng, dir.), is yet another visit to a toy-filled world, as a little girl is lulled into a dream world in the clouds by a sprinkle from the sandman who emerges off the wallpaper in her bedroom. She instantly befriends (and seems to fall in love with) a toy soldier residing there. He takes her to a secret row of giant storybooks, where they read (in an original song) about the Beast who haunts this Toyland. Flipping to an illustration in the book, the picture comes to life, and the beast reaches for the defenseless damsel, until the soldier slams the book cover in his face. The beast nevertheless pursues, prompting the soldier to employ military tactics in defense of the child. Finding a wind-up toy plane, the soldier launches it at the villain. The plane takes an unexpected wide loop, circling back around the soldier, but eventually heads in the right direction. It first proceeds up the beast’s spine, carving a line with its propeller in his hairy fur up his backbone. Then, the plane continues in a spiral path around and down the beast’s torso, leaving his body half-shaved, so that his fur resembles prison stripes. A cannon fails to fire, instead dragging its tail on the ground where its fuse was ignited, as if trying to smother a hotfoot, and the beast finally gets the little girl in his clutches. Of course, this was all a sandman-induced dream, and the girl awakens to hide under her bedcovers, her pajama drop-seat opening for a revealing “end” shot at the iris out.

Beauty and the Beast (Warner, Merrie Melodies (2-strip Cinecolor), 4/14/34, Isadore (Friz) Freleng, dir.), is yet another visit to a toy-filled world, as a little girl is lulled into a dream world in the clouds by a sprinkle from the sandman who emerges off the wallpaper in her bedroom. She instantly befriends (and seems to fall in love with) a toy soldier residing there. He takes her to a secret row of giant storybooks, where they read (in an original song) about the Beast who haunts this Toyland. Flipping to an illustration in the book, the picture comes to life, and the beast reaches for the defenseless damsel, until the soldier slams the book cover in his face. The beast nevertheless pursues, prompting the soldier to employ military tactics in defense of the child. Finding a wind-up toy plane, the soldier launches it at the villain. The plane takes an unexpected wide loop, circling back around the soldier, but eventually heads in the right direction. It first proceeds up the beast’s spine, carving a line with its propeller in his hairy fur up his backbone. Then, the plane continues in a spiral path around and down the beast’s torso, leaving his body half-shaved, so that his fur resembles prison stripes. A cannon fails to fire, instead dragging its tail on the ground where its fuse was ignited, as if trying to smother a hotfoot, and the beast finally gets the little girl in his clutches. Of course, this was all a sandman-induced dream, and the girl awakens to hide under her bedcovers, her pajama drop-seat opening for a revealing “end” shot at the iris out.

Skywriting reputedly began during WW1, within the ranks of the British Air Corps. It began to be commercially exploited in earnest around 1932. Of course, this meant within a matter of years, it was also ripe for exploitation by animators. Two brief examples of it appear during our present survey, providing spectacle in the first color cartoons from two different studios Pastry Town Wedding (Van Buren/RKO, Rainbow Parade (2-strip), 7/27/34 – Ted Eshbaugh, Burt Gillett, dir.) uses a dragonfly in lieu of a plane, emerging from a hangar to spell out in cake icing squirted from a tube by a baking elf the words, “Happy Wedding” in the sky. The lettering drifts down, to settle on the top layer of a giant wedding cake. Holiday Land (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Color Rhapsody (2-strip), 11/9/34, Sid Marcus, dir.). in its Christmas tableau for Scrappy, also features Christmas elves who decorate the tree by flying by on a large tube of white toothpaste with an aerial motor attached, squeezing out the words, “Merry Xmas” across the limbs of a Christmas tree.

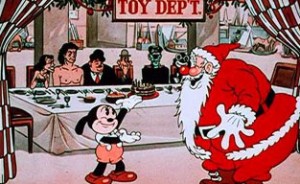

Toyland Premiere (Lanuz/Universal, Cartune Classics (2-strip), 12/7/34, Walter Lantz. dir.), again features brief shots of a toy armada sent out to teach a lesson to Laurel and Hardy, who attempt to steal a chocolate cake at a department store party thrown by Oswald Rabbit for Santa by disguising themselves in a dragon costume. Santa’s toy troops of course include an air corps, who buzz the boys in low flight right and left, almost severing the two-man costume down the middle with their propellers. This delightful holiday eye-feast benefits from an interesting vocal read for Santa, made even more fascinating from the realization that the voice is provided by none other than animation legend Tex Avery himself! Two shots are censored from current prints: the first being the creation of a replacement Santa suit with the use of a can of red paint, with one elf painting in the area on the seat of Santa’s pants as the portly toymaker stands. The last center dot of material to be painted is not currently shown, suggesting that Santa received a “goosing “ with the tip of the elf’s paintbrush, which did not pass for code re-release. The second is at the very end of the film, when Santa blows with hearty lung power upon the candles of the chocolate cake, sweeping the cake right off the table in the direction of Laurel and Hardy. We can safely assume the cake was smashed, and Laurel and Hardy made to appear in “brownface” in the chocolate frosting. It is almost surprising in the context of this film that this gag was edited out, as the film has no qualm about portraying a blackface Al Jolson in other scenes. Had I been writer on the excised shot, I would have envisioned Jolson approaching Laurel and Hardy on one knee, and calling them, “Sonny Boys!” Perhaps this is really what happened in the film.

Toyland Premiere (Lanuz/Universal, Cartune Classics (2-strip), 12/7/34, Walter Lantz. dir.), again features brief shots of a toy armada sent out to teach a lesson to Laurel and Hardy, who attempt to steal a chocolate cake at a department store party thrown by Oswald Rabbit for Santa by disguising themselves in a dragon costume. Santa’s toy troops of course include an air corps, who buzz the boys in low flight right and left, almost severing the two-man costume down the middle with their propellers. This delightful holiday eye-feast benefits from an interesting vocal read for Santa, made even more fascinating from the realization that the voice is provided by none other than animation legend Tex Avery himself! Two shots are censored from current prints: the first being the creation of a replacement Santa suit with the use of a can of red paint, with one elf painting in the area on the seat of Santa’s pants as the portly toymaker stands. The last center dot of material to be painted is not currently shown, suggesting that Santa received a “goosing “ with the tip of the elf’s paintbrush, which did not pass for code re-release. The second is at the very end of the film, when Santa blows with hearty lung power upon the candles of the chocolate cake, sweeping the cake right off the table in the direction of Laurel and Hardy. We can safely assume the cake was smashed, and Laurel and Hardy made to appear in “brownface” in the chocolate frosting. It is almost surprising in the context of this film that this gag was edited out, as the film has no qualm about portraying a blackface Al Jolson in other scenes. Had I been writer on the excised shot, I would have envisioned Jolson approaching Laurel and Hardy on one knee, and calling them, “Sonny Boys!” Perhaps this is really what happened in the film.

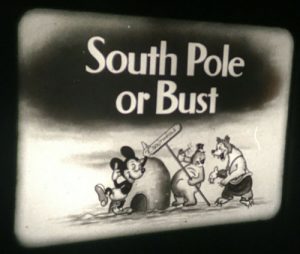

South Pole or Bust (Terrytoons/Educational, 12/14/34) retreads some old ground, but adds some new twists. Another pair of daring aviators (this time, a proto-Puddy pup and mouse), leave New York on a flight to the South Pole. The mouse spins the prop from above while standing on top of the plane, and almost gets blown off the tail by the force of the air flow, clambering back to a roof hatch to be let inside. The plane’s takeoff is another combination of running landing gear and flapping wings. When it reaches the end of a pier, it dives into the water, overturning three docked power boats, then swims a short way to get up speed for take-off. The plane passes between two skyscrapers, each of which bends in the middle to allow the plane’s wingspan to pass through their airspace. Even though they are still over New York City (depicted by a shot using a real-life photograph of the skyline with the animated characters laid over it), Terry can’t resist recycling his old gag from “Hawaiian Pineapple” of using flying elephants (two of them this time) for mid-air refueling with their trunks. (So why didn’t the boys simply gas up before takeoff?) For once, we get to see how pilots sustain themselves during a long flight, as the mouse is sent into the aircraft’s galley to rustle-up some sandwiches. Grabbing a loaf of bread and a stick of salami, the mouse climbs out the plane’s roof hatch, and feeds both foodstuffs into the plane’s propeller, where they are neatly sliced, the slices being sucked back into the ship via an air intake placed near the engine, where they land back in the galley, stacking themselves neatly into a tower of sandwiches.

The plane begins to encounter rough weather. A rainstorm prompts the pilots to extend a huge umbrella out the roof hatch, only to have the handle blasted apart by a bolt of lightning. Now over Antarctica, the plane bores headfirst into the side of an iceberg – which turns out to house a set of high-rise apartments, with a flock of polar bears aroused and peering out windows of the ice peak. The plane is covered in snow, and as the mouse shovels, he discovers they’ve picked up a passenger. No, it is not the same polar bear from “Ireland or Bust”, but a walrus, fast asleep in a four-post bed. The mouse slides the bed off the plane’s tail, leaving the walrus to crash through the ice surface below into cold water. (Wait a minute. Antarctica is a land continent, not a polar ice cap, so why is there water?) The infuriated walrus removes his tusks, and fastens them to his feet as skis to follow the plane. Amidst the polar lights, the plane comes in for a landing, to the cheers of the local wildlife. A quartet of penguins, carrying a key to the city and a sign reading ‘South Pole Rotarians”, bids formal greeting through a spokesman bird who sounds like Jimmy Durante – “Welcome to the South Pole and all dat kinda stuff!” But the crowd quickly disperses, as the walrus looms behind the two pilots. He gives chase, and the boys climb up the South Pole itself in attempt to escape the beast’s reach. The walrus tries to shake them down, and in a creative shot, a view of the earth is seen from outer space, with the whole planet trembling from the violent shaking of the walrus seen upside down at the pole below. For the first time, the plane sprouts a face, and, aroused by the shaking, takes off to the rescue. It drops a rope ladder to the boys, the pup and mouse hanging on both to the ladder and the pole, allowing the plane to tow both them and the pole away into the sky, with the walrus slipping off and left to futilely pursue on foot to the horizon for the iris out.

The plane begins to encounter rough weather. A rainstorm prompts the pilots to extend a huge umbrella out the roof hatch, only to have the handle blasted apart by a bolt of lightning. Now over Antarctica, the plane bores headfirst into the side of an iceberg – which turns out to house a set of high-rise apartments, with a flock of polar bears aroused and peering out windows of the ice peak. The plane is covered in snow, and as the mouse shovels, he discovers they’ve picked up a passenger. No, it is not the same polar bear from “Ireland or Bust”, but a walrus, fast asleep in a four-post bed. The mouse slides the bed off the plane’s tail, leaving the walrus to crash through the ice surface below into cold water. (Wait a minute. Antarctica is a land continent, not a polar ice cap, so why is there water?) The infuriated walrus removes his tusks, and fastens them to his feet as skis to follow the plane. Amidst the polar lights, the plane comes in for a landing, to the cheers of the local wildlife. A quartet of penguins, carrying a key to the city and a sign reading ‘South Pole Rotarians”, bids formal greeting through a spokesman bird who sounds like Jimmy Durante – “Welcome to the South Pole and all dat kinda stuff!” But the crowd quickly disperses, as the walrus looms behind the two pilots. He gives chase, and the boys climb up the South Pole itself in attempt to escape the beast’s reach. The walrus tries to shake them down, and in a creative shot, a view of the earth is seen from outer space, with the whole planet trembling from the violent shaking of the walrus seen upside down at the pole below. For the first time, the plane sprouts a face, and, aroused by the shaking, takes off to the rescue. It drops a rope ladder to the boys, the pup and mouse hanging on both to the ladder and the pole, allowing the plane to tow both them and the pole away into the sky, with the walrus slipping off and left to futilely pursue on foot to the horizon for the iris out.

Kool Penguins, an advertising film produced circa 1935, attributed by some to Audio Cinema, the company from which Terrytoons sprung (though I am not certain that the animation style matches the Terry product at all), includes the inexplicable image of a flock of penguins escaping poachers at the South Pole by, of all things, flying (the one thing penguins don’t do), by means of assuming a massed formation resembling a plane’s wings and fuselage. Well, I guess the writers couldn’t come up with any more practical form of transportation to carry the penguins from the pole to the cigarette factory in Kentucky. Just goes to show you should never believe what you’re told by a tobacco dealer.

Kool Penguins, an advertising film produced circa 1935, attributed by some to Audio Cinema, the company from which Terrytoons sprung (though I am not certain that the animation style matches the Terry product at all), includes the inexplicable image of a flock of penguins escaping poachers at the South Pole by, of all things, flying (the one thing penguins don’t do), by means of assuming a massed formation resembling a plane’s wings and fuselage. Well, I guess the writers couldn’t come up with any more practical form of transportation to carry the penguins from the pole to the cigarette factory in Kentucky. Just goes to show you should never believe what you’re told by a tobacco dealer.

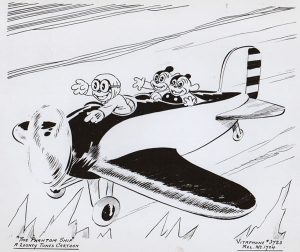

The Phantom Ship (Warner, Looney Tunes (Beans, Ham and Ex), 2/24/36 – Jack King, dir.) is a considerable disappointment. In discovering the transitional Looney Tunes that moved the studio away from the eras of Bosko and Buddy into the “funny animals” mode, it was at first intriguing to discover the efforts to create a stable of breakout characters from the cast of “I Haven’t Got a Hat”, and surprising to find that the likes of Beans the Cat, and the pups Ham and Ex, would be launched in starring efforts to give them a life of their own. Personally, I always hoped to find some standout instance among them where the characters would really shine and take on personality. Sadly, with the well-known exception of Porky Pig, none of these ventures ever quite lived up to potential. I generally came away with fonder recollections of certain episodes of the Buddy series than of the Beans gang (with the possible exception of “Westward Whoa”, which does not score on the personality strength of any one character, but as the only successful ensemble performance of all the characters together since “Hat”). In this one, Beans is almost totally upstaged by Ham and Ex, getting little chance to pull off any laughs of his own (as contrasted with “Alpine Antics”, where at least he is provided with some decent sight gag material, though there are no personality traits to lend any unique mood or style). Ham and Ex come off as unbearably intrusive and irritating, and not in a funny way as in the studio’s later introduction of “Porky’s Naughty Nephew”. To confuse the issue, they refer to their screen costar as “Uncle Beans”, which defies logic, considering Beans is a cat, while they are dogs. And, despite elaborate and advanced animation from Jack King, directing of the film in fact lacks direction, zipping through about 80% of the material as if hurrying to make way for the next sequence within the allotted footage, rarely allowing any scene to register in natural tempo. Even Bernard Brown’s musical score feels as if played too fast, barely able to keep up with the rushed pace of production. Add a weak, gagless ending, and a plotline that practically mirrors, yet pales by comparison to the surprises of, Waffles and Don’s “The Haunted Ship”, and it is easy to conclude why the film just doesn’t come off as memorable, and has languished in the vaults for years as a screening rarity.

The Phantom Ship (Warner, Looney Tunes (Beans, Ham and Ex), 2/24/36 – Jack King, dir.) is a considerable disappointment. In discovering the transitional Looney Tunes that moved the studio away from the eras of Bosko and Buddy into the “funny animals” mode, it was at first intriguing to discover the efforts to create a stable of breakout characters from the cast of “I Haven’t Got a Hat”, and surprising to find that the likes of Beans the Cat, and the pups Ham and Ex, would be launched in starring efforts to give them a life of their own. Personally, I always hoped to find some standout instance among them where the characters would really shine and take on personality. Sadly, with the well-known exception of Porky Pig, none of these ventures ever quite lived up to potential. I generally came away with fonder recollections of certain episodes of the Buddy series than of the Beans gang (with the possible exception of “Westward Whoa”, which does not score on the personality strength of any one character, but as the only successful ensemble performance of all the characters together since “Hat”). In this one, Beans is almost totally upstaged by Ham and Ex, getting little chance to pull off any laughs of his own (as contrasted with “Alpine Antics”, where at least he is provided with some decent sight gag material, though there are no personality traits to lend any unique mood or style). Ham and Ex come off as unbearably intrusive and irritating, and not in a funny way as in the studio’s later introduction of “Porky’s Naughty Nephew”. To confuse the issue, they refer to their screen costar as “Uncle Beans”, which defies logic, considering Beans is a cat, while they are dogs. And, despite elaborate and advanced animation from Jack King, directing of the film in fact lacks direction, zipping through about 80% of the material as if hurrying to make way for the next sequence within the allotted footage, rarely allowing any scene to register in natural tempo. Even Bernard Brown’s musical score feels as if played too fast, barely able to keep up with the rushed pace of production. Add a weak, gagless ending, and a plotline that practically mirrors, yet pales by comparison to the surprises of, Waffles and Don’s “The Haunted Ship”, and it is easy to conclude why the film just doesn’t come off as memorable, and has languished in the vaults for years as a screening rarity.

Aviator Beans makes the headlines with intentions to fly to a treasure ship wreck, apparently discovered frozen and locked in the ice of Iceland. Ham and Ex read the article, and decide to stow away aboard Beans’ plane. There is little new about the plane’s design – another craft that takes on a face when needed, and loves lubrication from Beans’ oil can. Noting the twin pips sneaking up on the plane, the plane itself crouches low, making easier the pups’ climb into the rear passenger compartment. With no gag for the spinning of the prop, Beans takes off, first flying over Russia. All circulating prints make a cut at this point, so we never see what Beans sees below – I can only guess a country full of bomb-throwing Bolsheviks. All we do see is a brief shot of Beans dancing a Russian high-kick dance atop the plane’s fuselage. Then, a location indicator on Beans’ dashboard switches from Russia to Iceland, as the thermometer dips so low, the mercury breaks out the bottom. Beans is briefly seen with a long icicle grown our from his nose, which he snaps off and tosses away. Sighting the ice-locked wreck below, Beans spirals down for a landing next to the ship. Out pop Ham and Ex with call of “Surprise!” – obviously not a pleasant one for Beans. One sight gag works, as Beans and the pups mount a gangplank/stairway that mysteriously drops from the side of the ship, only to have the stairs begin to move like a downward escalator, running the characters as if on a treadmill. Aboard ship, Beans finds a treasure chest, but also finds two pirates, frozen stiff next to a pot-bellied stove whose flame has gone out. Rather than leave well-enough alone, Beans pulls the wooden chairs out from under the seated pirates, tosses the seats into the stove, and lights a blaze inside. He then goes back to tossing treasure sacks out the porthole into his plane, never bothering to see the effects of the fire he has lit. (Did he set the fire just to get warm himself, or wouldn’t he realize it might have a thawing effect upon the two pirates?) So, why is he surprised when the pirates return to life, and try to reclaim their treasure? Ham and Ex run a bit of interference for their “Uncle”, and escape the clutches of one of the pirates by climbing hand over hand across the ship’s rigging. The pursuing pirate cuts their rope, but only succeeds in dropping the pups overboard into the plane cockpit, in which they take off. Meanwhile, Beans takes the blow of a rolled barrel of explosives, launching him into the air – where he intercepts the plane, landing in the passenger seat. Beans kisses the boys in thanks, and the plane simply flies away for the iris out.

Aviator Beans makes the headlines with intentions to fly to a treasure ship wreck, apparently discovered frozen and locked in the ice of Iceland. Ham and Ex read the article, and decide to stow away aboard Beans’ plane. There is little new about the plane’s design – another craft that takes on a face when needed, and loves lubrication from Beans’ oil can. Noting the twin pips sneaking up on the plane, the plane itself crouches low, making easier the pups’ climb into the rear passenger compartment. With no gag for the spinning of the prop, Beans takes off, first flying over Russia. All circulating prints make a cut at this point, so we never see what Beans sees below – I can only guess a country full of bomb-throwing Bolsheviks. All we do see is a brief shot of Beans dancing a Russian high-kick dance atop the plane’s fuselage. Then, a location indicator on Beans’ dashboard switches from Russia to Iceland, as the thermometer dips so low, the mercury breaks out the bottom. Beans is briefly seen with a long icicle grown our from his nose, which he snaps off and tosses away. Sighting the ice-locked wreck below, Beans spirals down for a landing next to the ship. Out pop Ham and Ex with call of “Surprise!” – obviously not a pleasant one for Beans. One sight gag works, as Beans and the pups mount a gangplank/stairway that mysteriously drops from the side of the ship, only to have the stairs begin to move like a downward escalator, running the characters as if on a treadmill. Aboard ship, Beans finds a treasure chest, but also finds two pirates, frozen stiff next to a pot-bellied stove whose flame has gone out. Rather than leave well-enough alone, Beans pulls the wooden chairs out from under the seated pirates, tosses the seats into the stove, and lights a blaze inside. He then goes back to tossing treasure sacks out the porthole into his plane, never bothering to see the effects of the fire he has lit. (Did he set the fire just to get warm himself, or wouldn’t he realize it might have a thawing effect upon the two pirates?) So, why is he surprised when the pirates return to life, and try to reclaim their treasure? Ham and Ex run a bit of interference for their “Uncle”, and escape the clutches of one of the pirates by climbing hand over hand across the ship’s rigging. The pursuing pirate cuts their rope, but only succeeds in dropping the pups overboard into the plane cockpit, in which they take off. Meanwhile, Beans takes the blow of a rolled barrel of explosives, launching him into the air – where he intercepts the plane, landing in the passenger seat. Beans kisses the boys in thanks, and the plane simply flies away for the iris out.

Boom Boom (Warner, Looney Tunes (Porky and Beans), 2/29/36 – Jack King, dir.), includes one of the briefest aerial sequences in any cartoon. A WWI epic, featuring the only concentrated effort to cast Porky Pig and Beans the Cat as a comedy-adventure team, the climax finds the boys on a mission to rescue the captured General Hardtack from torture. Their final getaway is made by hijacking an enemy plane, which is shot down by friendly fire from their own anti-aircraft guns in under 30 seconds! Nevertheless, from a hospital bed shared by the boys and the general, the general presents a medal, which Beans tears down the middle so that he and Porky can share it.

Off to China (Terrytoons/Educational, 3/20/36) – Here we go again with another Terry aviation toon. This time, a whole flight team, consisting of a cat and three mice, is saluted and sent upon a voyage to China in Terry’s first use of a “China Clipper” jumbo aircraft, by none other than Uncle Sam himself. Planned route includes a stopover in Hawaii, then on to China. Their plane runs and flaps wings in the usual rubbery fashion, but for once has the sense to gas up first, stopping an an ultra-large service station pump, and guzzling down 600 gallons of fuel. Huge throngs on the rooftops of three skyscrapers hop up and down to bid them farewell, while the boats in the harbor of what is presumably San Francisco (due to the presence of what appears to be the Golden Gate Bridge) toot a salute. As the plane sets out over the ocean waves, the cat pilot checks under the engine hood, revealing the role of the three mice, who manually run upon the engine crankshaft to fire the pistons. Some old gags receive reuse, first with a flock of gulls landing upon the tail of the plane and having to be shooed off, in similar fashion to Terry’s previous Hawaiian Pineapple. A new gag has the gulls circle and land in puffs of exhaust from the plane’s tail pipe, making the clouds into nests, where they lay eggs and hatch new broods of chicks. The windshield-wiper goggle gag appears again, nearly identical to its presentation in Disney’s “The Mail Pilot”. The plane shifts into vertical flight to fly above a rain cloud, as it had in “Lindy’s Cat”. Suddenly, the plane reaches Hawaii, where more reused animation appears, in the form of hula dancers identical in design to an earlier Navy-themed Terrytoon, “See the World”. A mouse jettisons a sack of mail for the islands, so large it temporarily sinks Hawaii below the water. For the last leg of the journey, the plane receives support in the form of a swim-in by riding straddled atop the backs of two whales. Arriving at the Chinese docks, we discover (although the ending of CBS’s prints appears cropped) that the purpose of the mission was merely to deliver bundle after bundle of dirty clothes to the Chinese laundries!

Off to China (Terrytoons/Educational, 3/20/36) – Here we go again with another Terry aviation toon. This time, a whole flight team, consisting of a cat and three mice, is saluted and sent upon a voyage to China in Terry’s first use of a “China Clipper” jumbo aircraft, by none other than Uncle Sam himself. Planned route includes a stopover in Hawaii, then on to China. Their plane runs and flaps wings in the usual rubbery fashion, but for once has the sense to gas up first, stopping an an ultra-large service station pump, and guzzling down 600 gallons of fuel. Huge throngs on the rooftops of three skyscrapers hop up and down to bid them farewell, while the boats in the harbor of what is presumably San Francisco (due to the presence of what appears to be the Golden Gate Bridge) toot a salute. As the plane sets out over the ocean waves, the cat pilot checks under the engine hood, revealing the role of the three mice, who manually run upon the engine crankshaft to fire the pistons. Some old gags receive reuse, first with a flock of gulls landing upon the tail of the plane and having to be shooed off, in similar fashion to Terry’s previous Hawaiian Pineapple. A new gag has the gulls circle and land in puffs of exhaust from the plane’s tail pipe, making the clouds into nests, where they lay eggs and hatch new broods of chicks. The windshield-wiper goggle gag appears again, nearly identical to its presentation in Disney’s “The Mail Pilot”. The plane shifts into vertical flight to fly above a rain cloud, as it had in “Lindy’s Cat”. Suddenly, the plane reaches Hawaii, where more reused animation appears, in the form of hula dancers identical in design to an earlier Navy-themed Terrytoon, “See the World”. A mouse jettisons a sack of mail for the islands, so large it temporarily sinks Hawaii below the water. For the last leg of the journey, the plane receives support in the form of a swim-in by riding straddled atop the backs of two whales. Arriving at the Chinese docks, we discover (although the ending of CBS’s prints appears cropped) that the purpose of the mission was merely to deliver bundle after bundle of dirty clothes to the Chinese laundries!

Into the second half of the 1930’s next time, including a notable early classic from Tex Avery.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

You’ve overlooked one cartoon from the mid-’30s that, whatever its entertainment value, has considerable historical interest, especially with respect to aviation: “In Venice” (Terrytoons/Educational, 15/12/33 — Frank Moser, dir.).

As the domes and bell tower of St. Mark’s Basilica throb obscenely in the background, the residents of Venice sing a merry chorus while paddling their gondolas down the Grand Canal. Among them is the milkmaid Mariuccia, milking her cow right there in the gondola and occasionally squirting jets of milk into the mouths of hungry fish. A policeman stops traffic to let through a submerged limousine with a motorcycle escort. The convoy ascends onto the piazza; the limousine’s door opens, a carpet rolls out, and who should emerge but… Will Rogers, with spurs on his boots and chewing his trademark wad of gum. (What is Will Rogers doing in Italy? See below.)

“Signores! Signores! Greetings to you, my friends!” the cowboy humorist sings in a resonant baritone, and a battalion of soldiers chant a reply, their right arms raised in a Fascist salute. Rogers continues: “What’s in the sky, flying high? Balbo coming home! Hail to our hero, brave and true!” (Who’s Balbo? See below.) There in the sky, Balbo is leading a squadron of airplanes, although he himself is not piloting one but merely flapping his arms like wings. After executing some tricky aerial maneuvers, he lands in front of Rogers, who pins a medal to his chest. Balbo reciprocates by pulling off his pointed beard and affixing it to Rogers’s chin.

The crowd cheers wildly… but then, the milkmaid’s gondola sinks into the canal. She cries out for help, and her cow removes one of its horns and blows an alarm with it. A soldier named Mario, sort of an Italian analogue to Puddy the Pup, dives in and swims to the rescue; but meanwhile, a top-hatted octopus has grabbed Mariucc’ by a shapely leg and dragged her off to his underwater castle. The pilot of a reconnaissance plane points out the octopus’s location, and Mario uses a handy swordfish to saw his way into the villain’s lair. They duel, all the while singing faux-Italian opera with a libretto consisting mainly of musical and culinary terms (“Mezzo-forte! Antipasto!”). Mario rescues the maiden, and the reconnaissance plane fishes them out of the canal on its anchor line. They declare their love in song, and the Venetian chorus shows its approbation with a stiff-arm salute.

So what’s going on here? In 1926 the Saturday Evening Post sent Will Rogers on a tour of Europe to get his impressions of the continent. Richard Washburn Child, the Post’s editor and a former U.S. Ambassador to Italy, was outspokenly pro-Fascist; he would later translate/ghostwrite Mussolini’s autobiography and run it as a serial in the pages of the Post, behind the wholesome Americana of Norman Rockwell’s cover paintings. Child arranged for Rogers to meet with Mussolini, who was deeply concerned with how his regime was perceived abroad and was always willing to speak with foreign journalists. Rogers was especially keen to ask Il Duce about his practice of torturing his political enemies by force-feeding them castor oil until they soiled themselves. Rogers thought that was hilarious.

Rogers never met a man he didn’t like, and he absolutely adored Mussolini. For the rest of his life — which, as we all know, ended in a plane crash in Alaska in 1935 — he would take every opportunity to extol the Fascist dictator and his policies. Given his abhorrence of war, his disdain for the Roosevelt administration, his friendship with Charles Lindbergh and his cozy relationship with Il Duce, it’s likely that Rogers, had he lived, would have been an enthusiastic supporter of the non-interventionist America First movement — at least, until Pearl Harbor.

As for Balbo, aviator Italo Balbo was Italy’s Minister of the Air Force. In the summer of 1933, as this cartoon was being planned, he took a squadron called the Italian Air Armada to the Century of Progress exhibition in Chicago. The airshow was immensely popular; a monument to Balbo was erected in Chicago (it’s still there, near Soldier Field), and President Roosevelt awarded him the Distinguished Flying Cross. To this day, in Commonwealth countries at least, the massed fly-by in the finale of an airshow is called a “balbo”. Italo Balbo was shot down by friendly fire during the Battle of Tobruk in 1940.

in toyland premiere that was eddie cantor yes i would like it restored it would take time but some folks out in cartoonland could recreate backrounds and the required animation and music for all of 15 seconds to complete the job it would be a labor of love and work and the results would be wonderful also with controversy

“Off to China” reflects Paul Terry’s interest in real-life aviation milestones, in this case the China Clipper, the first transpacific air mail service, which made its maiden flight in November 1935, just four months before the cartoon was released. It took off from Alameda Naval Air Station just south of Oakland, and as such its flight path would have taken it over the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge rather than the Golden Gate (although the bridge in the cartoon resembles the latter more than the former). Both bridges were still under construction in 1936.

I’ve heard of “Kool Penguins” but have never seen it before. It seems to get yanked off the Internet as soon as someone posts it, so enjoy it while it lasts. It looks to me like Ted Eshbaugh’s work; the whinnying horse wears an expression much like Goofy Goat, and when the penguins walk in single file I expect them to sing “We’re happy when we’re sad!” I love the ending, where Lady Liberty lights a cigarette with her torch and tilts her crown at a rakish angle. Well, she is French after all….

I used to see Toyland Premiere uncut on my local station. The chocolate from the cake “brownfaces” Laurel and Hardy into Amos ‘N’ Andy. Also, that blackface dude is NOT Al Jolson but Eddie Cantor. That’s a very good impression of Cantor’s voice.

However, the guy doing Bing Crosby sounds NOTHING like the actual thing. The impressionist has a tenor voice, and the real Bing was a baritone.

While it would be nice to see “Toyland Premiere” uncut, I’m more interested in what was cut from the scene with King Neptune and the mermaid in “Kool Penguins”.

Two Fleischer Screen Songs from this period are apposite here.

“Love Thy Neighbor” (20/7/34 — Myron Waldman and Edward Nolan, anim.), one of the newsreel parodies in the series, contains a segment with the dateline “Skeleton, Ky. Daring Newsreel Cameramen Get Kick Out Of Big Feat.” High in the sky, a man cranks a motion picture camera while standing on an airplane’s wing, and he continues to do so even when the plane dives, goes into a spin, and crashes. After two other cameramen are respectively shelled on a battlefield and attacked by a lion, a card is shown onscreen: “Cameraman Wanted!”

“I Wished on the Moon” (20/9/35 — Thomas Johnson, anim.) opens with an airborne dirigible marked “Portable Theatre Co. — Theatres for Rent” dumping a load of building materials onto a vacant lot; when they hit the ground, they assemble magically into a beautiful theatre building in Greek Revival style. After a second successful installation, however, the building components bounce off a peaked roof and wind up assembled all askew. This cartoon marks he debut of Wiffle Piffle, known for his peculiar arm-flapping gait and little else, who repeatedly tries to find his seat in a theatre filled with confusing staircases like Escher’s “Relativity”. In the end, the theatre’s lease runs out (because the lot is needed for a ball game), and a giant vacuum cleaner hose descends from the dirigible and sucks the building back into the airship’s cargo hold. The theatregoers are left lying on the ground in a daze, but Wiffle Piffle just picks himself up and goes unflappably on his way.