Although VE day would not be realized until May 8th, 1945, the attention of many animation studios in the waning year of the war seemed to be turning away from the Third Reich, and concentrating more upon the nation that had directly drawn us into the hostilities in the first place – Japan, and its rising sun. Those remaining wartime episodes to be discussed in this article follow such trend. But more importantly, animators were seeing increasing opportunity to return to their roots, forget the politics and patriotism that had driven their films for a good few too many years, and present comedy – and aviation – in a timeless, peacetime setting, with no agenda except pure entertainment and keeping up with the competing studios. Thus, we find a mixed bag of offerings for this wrap-up of the war years, still providing some education to the troops and a bit of propaganda here and there, but beginning to serve again the most basic need of the civilian audience – the chance for a good laugh.

The Plastics Inventor (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 9/1/44 – Jack King, dir.) – Plastics were a new thing on the scene in 1944. Hard for modern minds to imagine, but there was a time when virtually every useful object was fashioned from metal, wood, rubber, or stone. The discovery of chemical blends to develop artificial hardening substances of durability was a tremendous breakthrough, and, while many feel that the quality of objects created with it was “cheapened” and dramatically lessened as compared to objects made of the original materials, they made possible mass production that could only be dreamed of in days before, and drove overall production costs down so that objects previously costing many dollars might now be found in the five and dime. And, with the newest developments in finding more and more materials from which to blend these mixtures, it must have literally seemed like alchemy- fiving the impression that a usable plastic could be concocted out of almost anything. This film would not be the only pop-culture reference to be handed down upon the subject: witness the lyrics of a 1945 song hit for Helen Forrest and Dick Haymes, “I’ll Buy That Dream”. envisioning a post-war world with the couplet, “We’ll settle down in Dallas, in a little plastic palace.”

The Plastics Inventor (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 9/1/44 – Jack King, dir.) – Plastics were a new thing on the scene in 1944. Hard for modern minds to imagine, but there was a time when virtually every useful object was fashioned from metal, wood, rubber, or stone. The discovery of chemical blends to develop artificial hardening substances of durability was a tremendous breakthrough, and, while many feel that the quality of objects created with it was “cheapened” and dramatically lessened as compared to objects made of the original materials, they made possible mass production that could only be dreamed of in days before, and drove overall production costs down so that objects previously costing many dollars might now be found in the five and dime. And, with the newest developments in finding more and more materials from which to blend these mixtures, it must have literally seemed like alchemy- fiving the impression that a usable plastic could be concocted out of almost anything. This film would not be the only pop-culture reference to be handed down upon the subject: witness the lyrics of a 1945 song hit for Helen Forrest and Dick Haymes, “I’ll Buy That Dream”. envisioning a post-war world with the couplet, “We’ll settle down in Dallas, in a little plastic palace.”

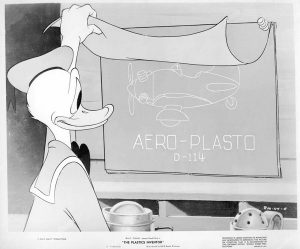

Donald Duck has taken up the craze of this phenomenon, which, in the fantasy world of Duckburg, has developed into a home industry. In the manner of a cooking show, a Professor Butterfield hosts radio’s “The Plastic Hour”, providing junior inventors with the latest recipes for use of the material. Today’s broadcast serves up the tasty prospect of baking an airplane – out of junk. Donald has obviously been following this show for a good long time, as he has outfitted his basement like a foundry, with boiling cauldrons, crane, ovens, custom cookie cutters, blueprints, and other industrial paraphernalia to assist in his projects, as if he were a junior Lockheed. For raw material, he has a two-story high pile of “junk”, including numerous mattresses and sofas, a chest of drawers, a battered piano, washboards, army boots, and half of a Model T. On the professor’s command, he dumps all of this mess into the pot, and stirs “until a rich, creamy texture is attained.” (With the varying melting points of all those errant objects, you’d think he’d be waiting until doomsday.) He then pours the “batter” into a giant metal mold pre-shaped for the fuselage, wings, propeller and tail, and waits for it to bake. While the station entertains with music from all plastic instruments, Donald rolls out an additional batch of batter with a rolling pin, and uses his custom cookie cutters to stamp out engine gears and a gearshift. He takes the remaining dough and compresses it into a cake decorating tube, squeezing it out as if it were icing upon a baking pan to form the shape of a steering wheel. As these simmer in another oven, the film commits a continuity error, as the professor asks “Is your tail assembly toasting? Well, don’t let it burn.” Two tail stabilizers pop out of a giant toaster, and Donald uses a butter knife to scrape off a bit of excess charcoal. (However, he never uses these parts, as the plane’s master mold already has a fully assembled tail.) The appropriate time has elapsed, and the master mold has done its work. Donald steps on a foot pedal, ejecting the “light as a feather” plane body from the mold, which he can push along in the air with the touch of a finger. This plastic is amazing stuff, as out of a single batter, the finished plane comes pre-colored in bright orange for its body and silver for its prop and exhaust pipes! “I’ll bet you forgot to bake your helmet”, the professor reminds. Donald grabs a last handful of batter, and smears it over the top of his head, down to his beak. He jabs two fingers in it to open two holes for his eyes (wouldn’t you think he’d need clear plastic there to complete his goggles?), and then runs to place his head under a quick-heating hair dryer. A few seconds, and the plastic again hardens into a two-color helmet and goggles set – still with his eyes presumably entirely unprotected by any transparent shields.

Donald Duck has taken up the craze of this phenomenon, which, in the fantasy world of Duckburg, has developed into a home industry. In the manner of a cooking show, a Professor Butterfield hosts radio’s “The Plastic Hour”, providing junior inventors with the latest recipes for use of the material. Today’s broadcast serves up the tasty prospect of baking an airplane – out of junk. Donald has obviously been following this show for a good long time, as he has outfitted his basement like a foundry, with boiling cauldrons, crane, ovens, custom cookie cutters, blueprints, and other industrial paraphernalia to assist in his projects, as if he were a junior Lockheed. For raw material, he has a two-story high pile of “junk”, including numerous mattresses and sofas, a chest of drawers, a battered piano, washboards, army boots, and half of a Model T. On the professor’s command, he dumps all of this mess into the pot, and stirs “until a rich, creamy texture is attained.” (With the varying melting points of all those errant objects, you’d think he’d be waiting until doomsday.) He then pours the “batter” into a giant metal mold pre-shaped for the fuselage, wings, propeller and tail, and waits for it to bake. While the station entertains with music from all plastic instruments, Donald rolls out an additional batch of batter with a rolling pin, and uses his custom cookie cutters to stamp out engine gears and a gearshift. He takes the remaining dough and compresses it into a cake decorating tube, squeezing it out as if it were icing upon a baking pan to form the shape of a steering wheel. As these simmer in another oven, the film commits a continuity error, as the professor asks “Is your tail assembly toasting? Well, don’t let it burn.” Two tail stabilizers pop out of a giant toaster, and Donald uses a butter knife to scrape off a bit of excess charcoal. (However, he never uses these parts, as the plane’s master mold already has a fully assembled tail.) The appropriate time has elapsed, and the master mold has done its work. Donald steps on a foot pedal, ejecting the “light as a feather” plane body from the mold, which he can push along in the air with the touch of a finger. This plastic is amazing stuff, as out of a single batter, the finished plane comes pre-colored in bright orange for its body and silver for its prop and exhaust pipes! “I’ll bet you forgot to bake your helmet”, the professor reminds. Donald grabs a last handful of batter, and smears it over the top of his head, down to his beak. He jabs two fingers in it to open two holes for his eyes (wouldn’t you think he’d need clear plastic there to complete his goggles?), and then runs to place his head under a quick-heating hair dryer. A few seconds, and the plastic again hardens into a two-color helmet and goggles set – still with his eyes presumably entirely unprotected by any transparent shields.

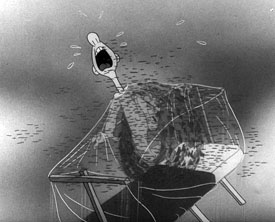

The first flight of the new invention. “This little number will do anything”, says the professor’s voice from the transistor radio, placed on the seat next to Donald in the cockpit, as the duck takes the craft into the wild blue. “Climbs like a rocket…and dives like a comet.” Donald tries these maneuvers, but briefly blacks out on the re-entry from the stratosphere. He pulls back on the controls just in time to avert a crash, passing so close to a leafless tree that the vacuum caused by his passing sucks all the tree’s spring foliage and blooms out months ahead of schedule. “Does the plane have any faults?” asks an announcer on the program. “Yes, one fault”, responds the professor. “It melts in water.” “Uh oh”, quacks Donald, and with good reason. He is flying straight into a storm system. To ensure he will be able to continue to listen to the broadcast for any helpful information, Donald safely tucks the radio under the seat, then concentrates on what is about to befall him. “Is your nose running? Well wipe it off”, suggests the professor, as gobs of gooey plastic begin to drip from around the engine cowling behind the propeller. Donald steps out onto the hood, desperately attempting to roll back the plastic with his hands. “Are your pants slipping?” Donald looks down to find the wheel wells – sometimes referred to as “pants” – dissolving and falling off from below, leaving him with no landing gear. One wing transforms into a wavy sea of goo. Donald grabs a rolling pin and flattens the dough out into wing shape again, using a knife to cut away excess beyond the area flattened, Approaching a range of high peaks, Donald attempts to steer and decelerate – but his foot pedals in the cockpit dissolve into sticky messes like gum stuck to his feet, and his steering wheel transforms into a pretzel. The planes slip-slides over the mountain slopes as if made of putty, leaving behind its last tire from the tail wheel, which breaks out of circular form to slither down the hill in a line like a snake. The engine starts to run away from the rest of the plane, and Donald has to grab it back, while the wings sag in the middle, unable to hold up the fuselage’s weight.

The first flight of the new invention. “This little number will do anything”, says the professor’s voice from the transistor radio, placed on the seat next to Donald in the cockpit, as the duck takes the craft into the wild blue. “Climbs like a rocket…and dives like a comet.” Donald tries these maneuvers, but briefly blacks out on the re-entry from the stratosphere. He pulls back on the controls just in time to avert a crash, passing so close to a leafless tree that the vacuum caused by his passing sucks all the tree’s spring foliage and blooms out months ahead of schedule. “Does the plane have any faults?” asks an announcer on the program. “Yes, one fault”, responds the professor. “It melts in water.” “Uh oh”, quacks Donald, and with good reason. He is flying straight into a storm system. To ensure he will be able to continue to listen to the broadcast for any helpful information, Donald safely tucks the radio under the seat, then concentrates on what is about to befall him. “Is your nose running? Well wipe it off”, suggests the professor, as gobs of gooey plastic begin to drip from around the engine cowling behind the propeller. Donald steps out onto the hood, desperately attempting to roll back the plastic with his hands. “Are your pants slipping?” Donald looks down to find the wheel wells – sometimes referred to as “pants” – dissolving and falling off from below, leaving him with no landing gear. One wing transforms into a wavy sea of goo. Donald grabs a rolling pin and flattens the dough out into wing shape again, using a knife to cut away excess beyond the area flattened, Approaching a range of high peaks, Donald attempts to steer and decelerate – but his foot pedals in the cockpit dissolve into sticky messes like gum stuck to his feet, and his steering wheel transforms into a pretzel. The planes slip-slides over the mountain slopes as if made of putty, leaving behind its last tire from the tail wheel, which breaks out of circular form to slither down the hill in a line like a snake. The engine starts to run away from the rest of the plane, and Donald has to grab it back, while the wings sag in the middle, unable to hold up the fuselage’s weight.

Donald nearly falls out when his control stick stretches to the limit during a dive, but the plane’s fuselage also stretches backward to catch him. Donald’s helmet is next to go, unraveling into two trails behind him which take the shape of braided hair, which Donald trims with a quick scissors cut. The exhaust pipes soften and inflate like balloons, then sprout holes everywhere, emitting the sounds of bagpipe music. The plane finally reaches the limits of its tolerances, and Donald is deluged in a sea of orange waves, sinking into the fluid substance. “If you keep flying plastic planes, you’ll be in the dough”, comments the professor. The entire plane dissolves, forming the shape of an orange parachute, with Donald suspended below like a marionette from sticky strands of the material. Below is his own front yard, where a small patch of garden greenery is bordered by a circle of wire, and a flock of birds picks at the soil. The plastic plops down over the circular patch, taking the shape of a pie crust, from which emerge “four and twenty blackbirds” from underneath. The last bird to emerge is Donald, red with rage, as the still-intact radio concludes, “Did your plane fall apart? That’s funny. You know it always happens to me that way too. Tune in again next week, and I’ll have a new recipe.” It’s all Donald can stand, and he grabs from his lawn a watering can, and, now knowing the plastic’s weakness, pours it liberally on the radio. The radio, of course, turns out to be plastic, too, and the professor’s voice distorts into an underwater blubble, as the radio dissolves into a puddle.

Donald nearly falls out when his control stick stretches to the limit during a dive, but the plane’s fuselage also stretches backward to catch him. Donald’s helmet is next to go, unraveling into two trails behind him which take the shape of braided hair, which Donald trims with a quick scissors cut. The exhaust pipes soften and inflate like balloons, then sprout holes everywhere, emitting the sounds of bagpipe music. The plane finally reaches the limits of its tolerances, and Donald is deluged in a sea of orange waves, sinking into the fluid substance. “If you keep flying plastic planes, you’ll be in the dough”, comments the professor. The entire plane dissolves, forming the shape of an orange parachute, with Donald suspended below like a marionette from sticky strands of the material. Below is his own front yard, where a small patch of garden greenery is bordered by a circle of wire, and a flock of birds picks at the soil. The plastic plops down over the circular patch, taking the shape of a pie crust, from which emerge “four and twenty blackbirds” from underneath. The last bird to emerge is Donald, red with rage, as the still-intact radio concludes, “Did your plane fall apart? That’s funny. You know it always happens to me that way too. Tune in again next week, and I’ll have a new recipe.” It’s all Donald can stand, and he grabs from his lawn a watering can, and, now knowing the plastic’s weakness, pours it liberally on the radio. The radio, of course, turns out to be plastic, too, and the professor’s voice distorts into an underwater blubble, as the radio dissolves into a puddle.

Target Snafu (Warner, Private Snafu, 10/23/44 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir,) – A first viewing of this film by civilian eyes might give avid Warner fans a case of deja-vu – and the more puzzling feeling that you’ve already seen this episode in color. Well, in a sense, you have. This black-and-white shortie for the troops was the blueprint and dry run for a Technicolor full length title which would surprisingly appear considerably after the war’s end – Of Thee I Sting (8/17/46), which we will take up in a later article. It is in style a classic early example of the sub-genre one might call “mockumentary”, presenting in graphic detail the training and exploits of a heroic flying squadron – who just happen to be mosquitos! With all the pomp and seriousness as if preserving for posterity the last mission of the Memphis Belle, Freleng brilliantly magnifies the daily routine event or tropical mosquitos looking for plasma into a complex, highly tactical military operation on the scale of D-Day. The idea had already been kicking around in Freleng’s head for awhile, but in the outfit of another war, previously inspiring a soldier-ant battle royal following the fighting strategies of WWI in 1940’s The Fighting 69 1/2th. Modernizing the send-up to the present great war would leave an indelible memory for winning satire of the whole genre of war epics, and would not only spark its color counterpart mentioned above, but be revisited years later as another vehicle for Freleng’s ants in Elmer Fudd’s Ant Pasted (1953).

Target Snafu (Warner, Private Snafu, 10/23/44 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir,) – A first viewing of this film by civilian eyes might give avid Warner fans a case of deja-vu – and the more puzzling feeling that you’ve already seen this episode in color. Well, in a sense, you have. This black-and-white shortie for the troops was the blueprint and dry run for a Technicolor full length title which would surprisingly appear considerably after the war’s end – Of Thee I Sting (8/17/46), which we will take up in a later article. It is in style a classic early example of the sub-genre one might call “mockumentary”, presenting in graphic detail the training and exploits of a heroic flying squadron – who just happen to be mosquitos! With all the pomp and seriousness as if preserving for posterity the last mission of the Memphis Belle, Freleng brilliantly magnifies the daily routine event or tropical mosquitos looking for plasma into a complex, highly tactical military operation on the scale of D-Day. The idea had already been kicking around in Freleng’s head for awhile, but in the outfit of another war, previously inspiring a soldier-ant battle royal following the fighting strategies of WWI in 1940’s The Fighting 69 1/2th. Modernizing the send-up to the present great war would leave an indelible memory for winning satire of the whole genre of war epics, and would not only spark its color counterpart mentioned above, but be revisited years later as another vehicle for Freleng’s ants in Elmer Fudd’s Ant Pasted (1953).

The “months of grueling work and preparation” that go into a massive raid are analyzed from the beginning. Selective service draws in the youth of the mosquito manpower, who line up for x-rays – receiving 1-A ratings if filled with malaria germs, and 4-F’s if they are clean. Boot camp drilling begins, with the fliers “marching” upon their wings in mid-air close formation. Manual of arms requires the troops to unscrew their long stinger noses for inspection of their hollow muzzles by a drill sergeant. Bayonet practice has the fliers zeroing in for direct stinger hits upon human-sized dummies with bulls-eyes at key positions of their most prominent veins. An obstacle course includes bottles of G.I. repellant, mechanical swatters and hand slappers, protective netting to scale and sever, and flypaper pits to leap. Night flying is practiced, amidst strings of searchlights combing the skies, and heavy anti-aircraft firing of spray from Flit cans. The cadets earn their wings as full-fledged fighter pilots. Now comes the meticulous planning from headquarters. Aerial photographers piece together a jigsaw puzzle of photos of the layout of the local army base, with results looking grimly discouraging, as most of the bunks have protective screening/netting and other precautions well-practiced. A last reconnaissance flier, who appears to have braved shot and shell to get his photo in, provides the last piece of the visual puzzle – a photo of Snafu, sleeping without his netting closed, and buck naked. Snafu’s photo is promptly ink-stamped, “Target for tonight.”

The “months of grueling work and preparation” that go into a massive raid are analyzed from the beginning. Selective service draws in the youth of the mosquito manpower, who line up for x-rays – receiving 1-A ratings if filled with malaria germs, and 4-F’s if they are clean. Boot camp drilling begins, with the fliers “marching” upon their wings in mid-air close formation. Manual of arms requires the troops to unscrew their long stinger noses for inspection of their hollow muzzles by a drill sergeant. Bayonet practice has the fliers zeroing in for direct stinger hits upon human-sized dummies with bulls-eyes at key positions of their most prominent veins. An obstacle course includes bottles of G.I. repellant, mechanical swatters and hand slappers, protective netting to scale and sever, and flypaper pits to leap. Night flying is practiced, amidst strings of searchlights combing the skies, and heavy anti-aircraft firing of spray from Flit cans. The cadets earn their wings as full-fledged fighter pilots. Now comes the meticulous planning from headquarters. Aerial photographers piece together a jigsaw puzzle of photos of the layout of the local army base, with results looking grimly discouraging, as most of the bunks have protective screening/netting and other precautions well-practiced. A last reconnaissance flier, who appears to have braved shot and shell to get his photo in, provides the last piece of the visual puzzle – a photo of Snafu, sleeping without his netting closed, and buck naked. Snafu’s photo is promptly ink-stamped, “Target for tonight.”

A row of tin cans open their lids like hangar doors, to reveal the fliers. Each one sharpens their stingers on grinding wheels, then fills up from miniature gasoline pumps of “high octane malaria”. Signals are flashed to the pilots by means of a firefly, giving the order to take off. Many rise from ground runways. Others emerge on water, wearing small pontoons made of seeds upon their feet, taking off as seaplanes. Another squad takes off from the deck of a “flat-top” leaf floating on a pond. The fliers amass over the army camp, go into dive formation, penetrate a gap in Snafu’s netting, and hit him right where it hurts the most. Snafu is then seen laid up in a hospital bed, alternating between images of panting like a dog upon a frying pan, or sitting on an ice block with teeth chattering. The victorious troops parade on land and in the skies in revue, as medals are handed out with the image of an exploding thermometer, reading “Order of the Rising Temperature”.

A row of tin cans open their lids like hangar doors, to reveal the fliers. Each one sharpens their stingers on grinding wheels, then fills up from miniature gasoline pumps of “high octane malaria”. Signals are flashed to the pilots by means of a firefly, giving the order to take off. Many rise from ground runways. Others emerge on water, wearing small pontoons made of seeds upon their feet, taking off as seaplanes. Another squad takes off from the deck of a “flat-top” leaf floating on a pond. The fliers amass over the army camp, go into dive formation, penetrate a gap in Snafu’s netting, and hit him right where it hurts the most. Snafu is then seen laid up in a hospital bed, alternating between images of panting like a dog upon a frying pan, or sitting on an ice block with teeth chattering. The victorious troops parade on land and in the skies in revue, as medals are handed out with the image of an exploding thermometer, reading “Order of the Rising Temperature”.

In the Aleutians – Isles of Enchantment (Oh Brother!) – (Warner, Private Snafu, 2/12/45 – Chuck Jones, dir.). Snafu plays a second fiddle in this episode to the islands themselves which form the center of attention for a mock “travelogue”. “Mother nature has endowed these islands with all the rich variety of weather from her abundant storehouse”, attests the narrator, as the scene changes abruptly from torrential rain to hurricane to blizzard. “In fact, the old bag blew her top!”, the narrator sums up. Snafu appears in a running gag of deciding what to wear in such a changeable climate, trudging along on foot to an appointed destination, and changing his outfit every four or five steps from raincoats to parkas to skis to bathing suit. Planes figure into the mix in two sequences, the first providing a new twist on Tex Avery’s “ice forming on the wings” gag from “Ceiling Hero”, showing at the tip of one of the plane’s wings an extension of ice atop which rests an Eskimo igloo, with its owner fishing with a line through a hole cut in the ice. In a second sequence, the narrator notes the recurring problem in these lands of being unable to keep moisture off the runways. Snafu reaches his destination, and is joined by a flight crew, who dive into a puddle of water so deep, they are totally submerged from view. Snafu himself makes one more costume change, into a deep sea diver’s helmet, then joins his comrades in the puddle’s depths. Out of the miniature lake rises a plane in takeoff, carrying Snafu. A view of him inside a gunner’s glass canopy reveals that being underwater has done the plane no good, with Snafu’s head underwater in a veritable goldfish bowl, complete with a live fish swimming around him. Snafu opens the plane’s bomb bay doors, and the fish parachutes out, only to be swallowed by a Jimmy Durante walrus for the iris out, who states “That’s the conditions that prevail.”

In the Aleutians – Isles of Enchantment (Oh Brother!) – (Warner, Private Snafu, 2/12/45 – Chuck Jones, dir.). Snafu plays a second fiddle in this episode to the islands themselves which form the center of attention for a mock “travelogue”. “Mother nature has endowed these islands with all the rich variety of weather from her abundant storehouse”, attests the narrator, as the scene changes abruptly from torrential rain to hurricane to blizzard. “In fact, the old bag blew her top!”, the narrator sums up. Snafu appears in a running gag of deciding what to wear in such a changeable climate, trudging along on foot to an appointed destination, and changing his outfit every four or five steps from raincoats to parkas to skis to bathing suit. Planes figure into the mix in two sequences, the first providing a new twist on Tex Avery’s “ice forming on the wings” gag from “Ceiling Hero”, showing at the tip of one of the plane’s wings an extension of ice atop which rests an Eskimo igloo, with its owner fishing with a line through a hole cut in the ice. In a second sequence, the narrator notes the recurring problem in these lands of being unable to keep moisture off the runways. Snafu reaches his destination, and is joined by a flight crew, who dive into a puddle of water so deep, they are totally submerged from view. Snafu himself makes one more costume change, into a deep sea diver’s helmet, then joins his comrades in the puddle’s depths. Out of the miniature lake rises a plane in takeoff, carrying Snafu. A view of him inside a gunner’s glass canopy reveals that being underwater has done the plane no good, with Snafu’s head underwater in a veritable goldfish bowl, complete with a live fish swimming around him. Snafu opens the plane’s bomb bay doors, and the fish parachutes out, only to be swallowed by a Jimmy Durante walrus for the iris out, who states “That’s the conditions that prevail.”

Cap’n Cub (Ted Eshbaugh, 3/12/45 – Ted Eshbaugh, dir.) – The pioneering independent animator who provided test films for so many early experimental color systems, introduced color to the Van Buren studios, and supplied promotional films to the 1939 World’s Fair, in what may have been his last production. Ted is obviously trying to “go modern” in this one, though it is difficult to determine precisely who he is trying to emulate. He is attempting more posed animation and cleaner lines, at times giving the production a look of wanting to be something either produced at Paramount’s Famous Studios or at Warner Brothers. Yet his title character is more of a throwback to the 30’s – a sort of a cross between Mickey Mouse and Cubby Bear, without much in the way of any distinctive personality traits, excepting being considerably more aggressive against the Japanese that Mickey would have ever dared to be. Painfully, despite Eshbaugh’s best efforts, and a small number of shots that work reasonably well, the final production has a look of being amateurish compared to the work of the major studios, with action often stilted and lacking in the smoothness of reasonable in-betweening, giving away the fact that the producer was probably critically understaffed for skilled manpower. It is further likely, given the rarity of this film and the unusual circumstances of an independent fighting for distribution so late in the game, that the film was seen by relatively few in its day. Even Eshbaugh must have been forced to concede that the day had passed when he could be competitive in the industry, and the decision to hang up his pencil could not have been far behind.

Cap’n Cub (Ted Eshbaugh, 3/12/45 – Ted Eshbaugh, dir.) – The pioneering independent animator who provided test films for so many early experimental color systems, introduced color to the Van Buren studios, and supplied promotional films to the 1939 World’s Fair, in what may have been his last production. Ted is obviously trying to “go modern” in this one, though it is difficult to determine precisely who he is trying to emulate. He is attempting more posed animation and cleaner lines, at times giving the production a look of wanting to be something either produced at Paramount’s Famous Studios or at Warner Brothers. Yet his title character is more of a throwback to the 30’s – a sort of a cross between Mickey Mouse and Cubby Bear, without much in the way of any distinctive personality traits, excepting being considerably more aggressive against the Japanese that Mickey would have ever dared to be. Painfully, despite Eshbaugh’s best efforts, and a small number of shots that work reasonably well, the final production has a look of being amateurish compared to the work of the major studios, with action often stilted and lacking in the smoothness of reasonable in-betweening, giving away the fact that the producer was probably critically understaffed for skilled manpower. It is further likely, given the rarity of this film and the unusual circumstances of an independent fighting for distribution so late in the game, that the film was seen by relatively few in its day. Even Eshbaugh must have been forced to concede that the day had passed when he could be competitive in the industry, and the decision to hang up his pencil could not have been far behind.

The entire concept also has a “dated” feel, seeming like a script that would have been developed much earlier in the war years, and was released at a time when pure propaganda flag-waver cartoons were starting to fall out of favor. This may also give away production problems and limitations, suggesting that the project may have begun a season or two before, and taken that long to reach completion or find a theater in which to screen. Cub might as well be the animal equivalent of Billy Mitchell or Major De Seversky before him – a veteran respected by military leaders, but left to be the voice from outside their ranks to propose the need for a stronger air presence in battle. He attends a parade where the latest in armament and weaponry passes before the military brass in a reviewing stand. Despite mighty tanks, skunk-powered stink bombs, and a cannon painted with invisible camouflage paint (lifting an idea from Donald Duck’s “The Vanishing Private” and George Pal’s “Rhythm in the Ranks”, among other competing cartoons), Cap’n Cub is non-plussed, and sums up that “Plainly speaking, what we need is planes, planers, planes!” He consults with a designer on blueprints, then supervises over a factory where all action is set to a conga beat. Airplane tires are mixed from melting scrap rubber objects (including inflatable rubber horses and other such bric-a-brac) in a cocktail-shaker shaped mixer, then pouring the batter into a waffle iron that produces three tires at a time. Sheet metal is pressed into a three-sided metal mold to produce instant fuselages, which meet up with the rolling tires to serve as their shoes, and dance their way to the painting room for a quick coat of yellow paint from spray nozzles. Next, each plane dances under an elevated platform where several animals screw a propeller onto their nose. Finally, both planes and pilots intersect each other in curving conga lines, the pilots hopping into the cockpits at the end of the line for immediate takeoff. Even the lowly Terrytoons could have animated this sequence twice as smoothly with one hand tied behind their backs. The “toony” yellow planes join up in the sky with the Cap’n at their lead. One unexpected laugh occurs as the squadron flies through a cloud, and briefly becomes separated, the Cap’n looking back to find himself at the head of a V-formation of quacking ducks who happened to be passing through the same cloud. But it doesn’t take more than a second for him to find the right fliers to lead again, and they proceed into enemy territory.

The entire concept also has a “dated” feel, seeming like a script that would have been developed much earlier in the war years, and was released at a time when pure propaganda flag-waver cartoons were starting to fall out of favor. This may also give away production problems and limitations, suggesting that the project may have begun a season or two before, and taken that long to reach completion or find a theater in which to screen. Cub might as well be the animal equivalent of Billy Mitchell or Major De Seversky before him – a veteran respected by military leaders, but left to be the voice from outside their ranks to propose the need for a stronger air presence in battle. He attends a parade where the latest in armament and weaponry passes before the military brass in a reviewing stand. Despite mighty tanks, skunk-powered stink bombs, and a cannon painted with invisible camouflage paint (lifting an idea from Donald Duck’s “The Vanishing Private” and George Pal’s “Rhythm in the Ranks”, among other competing cartoons), Cap’n Cub is non-plussed, and sums up that “Plainly speaking, what we need is planes, planers, planes!” He consults with a designer on blueprints, then supervises over a factory where all action is set to a conga beat. Airplane tires are mixed from melting scrap rubber objects (including inflatable rubber horses and other such bric-a-brac) in a cocktail-shaker shaped mixer, then pouring the batter into a waffle iron that produces three tires at a time. Sheet metal is pressed into a three-sided metal mold to produce instant fuselages, which meet up with the rolling tires to serve as their shoes, and dance their way to the painting room for a quick coat of yellow paint from spray nozzles. Next, each plane dances under an elevated platform where several animals screw a propeller onto their nose. Finally, both planes and pilots intersect each other in curving conga lines, the pilots hopping into the cockpits at the end of the line for immediate takeoff. Even the lowly Terrytoons could have animated this sequence twice as smoothly with one hand tied behind their backs. The “toony” yellow planes join up in the sky with the Cap’n at their lead. One unexpected laugh occurs as the squadron flies through a cloud, and briefly becomes separated, the Cap’n looking back to find himself at the head of a V-formation of quacking ducks who happened to be passing through the same cloud. But it doesn’t take more than a second for him to find the right fliers to lead again, and they proceed into enemy territory.

As a V-formation of Japanese bombers is sighted, Cub’s fliers engage them. An extended side trip focuses on a heavy-set Westerner of unknown species, three times too big to fit in his cockpit, who instead rides straddling the fuselage with a foot on each wing. The character looks and acts like a cross between Peg-Leg Pete in Two Gun Mickey and Slim Pickens in Dr. Strangelove, shooting in all directions with his six-shooters rather than aerial machine guns to blast out the motors of the enemy bombers, and letting out cowboy whoops and howls throughout the process. A kangaroo pilot stands in her cockpit and pulls out a machine gun from her pouch to fire at another plane. The Japanese bomber raises a cannon from its nose and blasts the machine gun out of the kangaroo’s hands. But reinforcement arrives in the form of a Joey inside the kangaroo’s pouch, armed with a double-barreled shotgun, who takes out the bomber’s motor with his shots, then tells his mother, “I dood it.”

As a V-formation of Japanese bombers is sighted, Cub’s fliers engage them. An extended side trip focuses on a heavy-set Westerner of unknown species, three times too big to fit in his cockpit, who instead rides straddling the fuselage with a foot on each wing. The character looks and acts like a cross between Peg-Leg Pete in Two Gun Mickey and Slim Pickens in Dr. Strangelove, shooting in all directions with his six-shooters rather than aerial machine guns to blast out the motors of the enemy bombers, and letting out cowboy whoops and howls throughout the process. A kangaroo pilot stands in her cockpit and pulls out a machine gun from her pouch to fire at another plane. The Japanese bomber raises a cannon from its nose and blasts the machine gun out of the kangaroo’s hands. But reinforcement arrives in the form of a Joey inside the kangaroo’s pouch, armed with a double-barreled shotgun, who takes out the bomber’s motor with his shots, then tells his mother, “I dood it.”

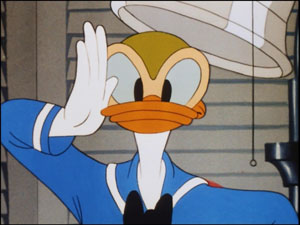

In the most elaborate sequence of the film, where most of the more sophisticated visual effects are clustered, an enemy superbomber casts its shadow over the puffy surface of a large cloudbank. Despite the aircraft’s size, the plane carries a crew consisting of a single monkey, who must serve as both pilot and gunnery crew. He lines up the Cap’n in the sights of twin machine guns, and briefly knocks the Cub for a loop, fortunately only causing him to touch down softly on another cloud. “Why you sappy Jappy. I’ll “knock” your sake”, grumbles Cub. He begins to fly circles around the bomber, shooting lines of bullet-hole perforations around key areas of the motors, wings, tail section, etc. Inside the larger aircraft, the monkey scrambles to meet each round of shooting with counter-measures. He appears to have a near endless supply of wire inside the plane, and as fast as a section of the ship becomes disconnected from Cub’s fire, the monkey ties it back to the plane with a loop of wire. But this can only go on for so long – until the plane is literally being held together by a thread. Dozens of parts of the craft bob and stretch away from one another, exposing the thin wiring that is their sole means of support. Cub continues systematically firing to sever the wire connections. The plane parts begin to randomly spin, producing one of the best laughs in the film, as they hopelessly twirl amidst the audible jabbering of the monkey, spinning him round and round, while the soundtrack music shifts to the sounds of a slightly off-key band organ to suggest a merry-go-round. Eventually, the snapping wires wrap themselves around the monkey, binding him securely to the pilot’s seat, while Cub delivers the final shots to cause an explosion, the monkey disappearing in a red blast that briefly takes on the shape of Japan’s rising sun insignia. Cub and his squadron fly in formation toward the camera in the final shot, Cub giving a salute to the audience for the fade out.

In the most elaborate sequence of the film, where most of the more sophisticated visual effects are clustered, an enemy superbomber casts its shadow over the puffy surface of a large cloudbank. Despite the aircraft’s size, the plane carries a crew consisting of a single monkey, who must serve as both pilot and gunnery crew. He lines up the Cap’n in the sights of twin machine guns, and briefly knocks the Cub for a loop, fortunately only causing him to touch down softly on another cloud. “Why you sappy Jappy. I’ll “knock” your sake”, grumbles Cub. He begins to fly circles around the bomber, shooting lines of bullet-hole perforations around key areas of the motors, wings, tail section, etc. Inside the larger aircraft, the monkey scrambles to meet each round of shooting with counter-measures. He appears to have a near endless supply of wire inside the plane, and as fast as a section of the ship becomes disconnected from Cub’s fire, the monkey ties it back to the plane with a loop of wire. But this can only go on for so long – until the plane is literally being held together by a thread. Dozens of parts of the craft bob and stretch away from one another, exposing the thin wiring that is their sole means of support. Cub continues systematically firing to sever the wire connections. The plane parts begin to randomly spin, producing one of the best laughs in the film, as they hopelessly twirl amidst the audible jabbering of the monkey, spinning him round and round, while the soundtrack music shifts to the sounds of a slightly off-key band organ to suggest a merry-go-round. Eventually, the snapping wires wrap themselves around the monkey, binding him securely to the pilot’s seat, while Cub delivers the final shots to cause an explosion, the monkey disappearing in a red blast that briefly takes on the shape of Japan’s rising sun insignia. Cub and his squadron fly in formation toward the camera in the final shot, Cub giving a salute to the audience for the fade out.

The film might be entirely forgotten today, if it were not for Official Films picking it up among other Eshbaugh titles like “Goofy Goat” and “The Snow Man” for home movie distribution. Some reissue sources have referred to the film by the title Cap’n Cub Blasts the Japs, making the cartoon seem more dated still.

Fisherman’s Luck (Terrytoons/Fox. Gandy Goose, 3/23/45 – Eddie Donnelly. dir.) – Back in civilian life for a change, Gandy and Sourpuss rest up from their many years of war adventures with a leisurely fishing excursion. They nevertheless keep things up to date, with the latest in modern conveyances – a fishing boat equipped with helicopter propeller, to make an aerial landing on the lake of their choice. Sourpuss reminds Gandy, “We’re out here to catch fish – not to drown woims!” Throwing out the anchor doesn’t go smoothly, as it is tossed back upon Sourpuss by a fish vigorously complaining that it conked him on the head. Gandy gets all the lucky breaks, catching whole schools of fish on one hook that encircle his bait to form a multicolored fish “bouquet”, with Gandy deeply inhaling to savor its fishy aroma. Sourpuss, on the other hand, encounters an electric eel, that scares his worm back into the bait box, and turns the cat into most of the hues in the Technicolor spectrum from its electric shock. Sourpuss tries a prank on Gandy, hooking Gandy’s line to an old submerged barrel. But when Gandy reels it in, he merely turns the handle on its tap, and pours out a continuous flow of fish. A school of flying fish flap lazily overhead. Gandy and Sourpuss rev up their helicopter motor and attempt to meet their prey in the sky, choosing rifles instead of rods and reels to bag them as if on a duck hunt. The recoil of their rifles is too great, and the flying boat is forced down from the shock waves into the lake, Sourpuss only having time to yell “Cease fire!” before the craft sinks into the blue waters. A monstrous fish (a marlin?), whom the narrator refers to as a “devil of the deep”, is seen at the top of the underwater food chain of a series of fish of ever-increasing size swallowing one another. He celebrates his champion status with a mighty Tarzan yell above the surface, and is spotted by Gandy and Sourpuss, aloft again in their boat. The boys haul out a harpoon gun from their supplies, and hook the marlin. A spirited tug of war develops, in which the narrator can’t tell who has who, and concludes “They’ve got each other.” Our heroes are dragged through the skies as they try to reel in, spending part of their flight time upside down, until with one mighty tug, they land the marlin aboard their ship. This is by no means an end to their troubles, as the marlin, many times bigger than the ship, menacingly stares down the boys eye to eye. A struggle takes place, the fish finally dragging Gandy overboard, while Sourpuss maintains a grip above on the harpoon reel. Gandy engages in fisticuffs with the marlin below, and eventually delivers a knockout blow that leaves the fish stiff and out like a light. Gandy climbs back to the boat above, and he and Sourpuss haul in the line, leaving the marlin dangling from the stern of the airboat. As the boys step on the gas to fly home, the vibration causes the marlin’s jaw to fall open. He falls away, leaving on the hook the large fish he had swallowed in the previous fish-eat-fish sequence of the film. That fish in turn falls away, leaving the next smallest on the line. And the next – and the next – and the next – until our triumphant boys wave goodbye to the camera, little realizing that all they have to show for their day’s efforts is one lone minnow on the hook.

Fisherman’s Luck (Terrytoons/Fox. Gandy Goose, 3/23/45 – Eddie Donnelly. dir.) – Back in civilian life for a change, Gandy and Sourpuss rest up from their many years of war adventures with a leisurely fishing excursion. They nevertheless keep things up to date, with the latest in modern conveyances – a fishing boat equipped with helicopter propeller, to make an aerial landing on the lake of their choice. Sourpuss reminds Gandy, “We’re out here to catch fish – not to drown woims!” Throwing out the anchor doesn’t go smoothly, as it is tossed back upon Sourpuss by a fish vigorously complaining that it conked him on the head. Gandy gets all the lucky breaks, catching whole schools of fish on one hook that encircle his bait to form a multicolored fish “bouquet”, with Gandy deeply inhaling to savor its fishy aroma. Sourpuss, on the other hand, encounters an electric eel, that scares his worm back into the bait box, and turns the cat into most of the hues in the Technicolor spectrum from its electric shock. Sourpuss tries a prank on Gandy, hooking Gandy’s line to an old submerged barrel. But when Gandy reels it in, he merely turns the handle on its tap, and pours out a continuous flow of fish. A school of flying fish flap lazily overhead. Gandy and Sourpuss rev up their helicopter motor and attempt to meet their prey in the sky, choosing rifles instead of rods and reels to bag them as if on a duck hunt. The recoil of their rifles is too great, and the flying boat is forced down from the shock waves into the lake, Sourpuss only having time to yell “Cease fire!” before the craft sinks into the blue waters. A monstrous fish (a marlin?), whom the narrator refers to as a “devil of the deep”, is seen at the top of the underwater food chain of a series of fish of ever-increasing size swallowing one another. He celebrates his champion status with a mighty Tarzan yell above the surface, and is spotted by Gandy and Sourpuss, aloft again in their boat. The boys haul out a harpoon gun from their supplies, and hook the marlin. A spirited tug of war develops, in which the narrator can’t tell who has who, and concludes “They’ve got each other.” Our heroes are dragged through the skies as they try to reel in, spending part of their flight time upside down, until with one mighty tug, they land the marlin aboard their ship. This is by no means an end to their troubles, as the marlin, many times bigger than the ship, menacingly stares down the boys eye to eye. A struggle takes place, the fish finally dragging Gandy overboard, while Sourpuss maintains a grip above on the harpoon reel. Gandy engages in fisticuffs with the marlin below, and eventually delivers a knockout blow that leaves the fish stiff and out like a light. Gandy climbs back to the boat above, and he and Sourpuss haul in the line, leaving the marlin dangling from the stern of the airboat. As the boys step on the gas to fly home, the vibration causes the marlin’s jaw to fall open. He falls away, leaving on the hook the large fish he had swallowed in the previous fish-eat-fish sequence of the film. That fish in turn falls away, leaving the next smallest on the line. And the next – and the next – and the next – until our triumphant boys wave goodbye to the camera, little realizing that all they have to show for their day’s efforts is one lone minnow on the hook.

Goofy News Views (Columbia/Screen Gems, Phantasy, 4/27/45 – Sid Marcus, dir.) – Standard style newsreel spoof a la Fleischer or Warner, without the gag locations for datelines. One news item reads, “Professor Baggysacks Demonstrates his New Auto-Gyro.” The device is a full-size propeller fastened to a cap worn on the professor’s head, wired to an engine/control box held in the professor’s hands. As a flock of pigeons looks on from above, the professor calls out, “Clear the way. I’m, coming up.” He starts up the device’s engine, but its two pistons sag and droop. He then turns a crank on the control box’s side – and the propeller unexpectedly shifts into reverse, driving the professor into a circular hole in the ground, which fills with water. Virtually this same gag would later be pilfered by Tex Avery for “Daredevil Droopy”, and a variant utilized by Chuck Jones for Wile E. Coyote.

Goofy News Views (Columbia/Screen Gems, Phantasy, 4/27/45 – Sid Marcus, dir.) – Standard style newsreel spoof a la Fleischer or Warner, without the gag locations for datelines. One news item reads, “Professor Baggysacks Demonstrates his New Auto-Gyro.” The device is a full-size propeller fastened to a cap worn on the professor’s head, wired to an engine/control box held in the professor’s hands. As a flock of pigeons looks on from above, the professor calls out, “Clear the way. I’m, coming up.” He starts up the device’s engine, but its two pistons sag and droop. He then turns a crank on the control box’s side – and the propeller unexpectedly shifts into reverse, driving the professor into a circular hole in the ground, which fills with water. Virtually this same gag would later be pilfered by Tex Avery for “Daredevil Droopy”, and a variant utilized by Chuck Jones for Wile E. Coyote.

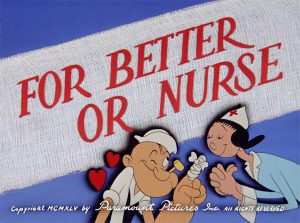

For Better or Nurse (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 6/8/45 – I. Sparber, dir.) This gives me a chance to make up for an omission from a previous article, where a gag passed by so quickly, I, in my haste to complete my deadline, chose to leave it out of discussion. This film is essentially a Technicolor remake of the earlier Fleischer Popeye film, “Hospitaliky” (4/16/37). The premise of both films is Popeye and Bluto following Olive to a hospital where she works as a nurse, only to be turned away by her at the door, who tells them that in order to go to a hospital they have to be sick or hurt real bad. The boys thus enter into a competition of self-destruction, to see who can get hurt the worst and the fastest. In both films, Popeye acquires a plane. In the original, he climbs out of the cockpit and merely jumps off the wing. A split second later, he finds himself surprisingly safe and sound, having accidentally landed in a net held by firemen at the scene of a fire below. In the 1945 version, Popeye decides to make it a power dive rather than a mere jump, by sawing away the wings of his plane, and proceeding to Earth at full throttle. The plane crashes, and Popeye and the wreck lay side by side as an ambulance approaches. The paramedics step out with a stretcher, and gently place the wrecked plane upon it, then drive off with it, leaving Popeye ignored upon the ground, apparently unhurt. Both films climax with a similar battle between the boys for positioning upon a railroad track in the path of an oncoming train, each of them delivering a sock to the other’s jaw that lands both of them off the tracks as the train passes. But Popeye determines that one of them is going to the hospital – “and it ain’t you!” He satisfies this prophecy by force-feeding Bluto spinach, causing him to involuntarily beat up on the helpless Popeye, putting him in traction. In the original, Popeye gets the girl. In the remake, an added twist occurs, as Olive dumps the bandaged Popeye out the window into a trash can, pointing out to them one overlooked detail. “Can’t you boys read?” She points to the sign above the hospital door. Above the word “Hospital” are the additional words, “Cat and Dog”. After all their efforts, Popeye and Bluto snap, and maniacally lapse into yowling and howling animal imitations of a cat and dog. The final shot shows them locked in the back compartment of a barred padded wagon, being driven to the “Happy Valley Screwball Institute” for the iris out.

For Better or Nurse (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 6/8/45 – I. Sparber, dir.) This gives me a chance to make up for an omission from a previous article, where a gag passed by so quickly, I, in my haste to complete my deadline, chose to leave it out of discussion. This film is essentially a Technicolor remake of the earlier Fleischer Popeye film, “Hospitaliky” (4/16/37). The premise of both films is Popeye and Bluto following Olive to a hospital where she works as a nurse, only to be turned away by her at the door, who tells them that in order to go to a hospital they have to be sick or hurt real bad. The boys thus enter into a competition of self-destruction, to see who can get hurt the worst and the fastest. In both films, Popeye acquires a plane. In the original, he climbs out of the cockpit and merely jumps off the wing. A split second later, he finds himself surprisingly safe and sound, having accidentally landed in a net held by firemen at the scene of a fire below. In the 1945 version, Popeye decides to make it a power dive rather than a mere jump, by sawing away the wings of his plane, and proceeding to Earth at full throttle. The plane crashes, and Popeye and the wreck lay side by side as an ambulance approaches. The paramedics step out with a stretcher, and gently place the wrecked plane upon it, then drive off with it, leaving Popeye ignored upon the ground, apparently unhurt. Both films climax with a similar battle between the boys for positioning upon a railroad track in the path of an oncoming train, each of them delivering a sock to the other’s jaw that lands both of them off the tracks as the train passes. But Popeye determines that one of them is going to the hospital – “and it ain’t you!” He satisfies this prophecy by force-feeding Bluto spinach, causing him to involuntarily beat up on the helpless Popeye, putting him in traction. In the original, Popeye gets the girl. In the remake, an added twist occurs, as Olive dumps the bandaged Popeye out the window into a trash can, pointing out to them one overlooked detail. “Can’t you boys read?” She points to the sign above the hospital door. Above the word “Hospital” are the additional words, “Cat and Dog”. After all their efforts, Popeye and Bluto snap, and maniacally lapse into yowling and howling animal imitations of a cat and dog. The final shot shows them locked in the back compartment of a barred padded wagon, being driven to the “Happy Valley Screwball Institute” for the iris out.

A Tale of Two Mice (Warner, 6/9/45 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) – In order to provide a return for the Abbott and Costello caricatures used to great advantage by Bob Clampett in “A Tale of Two Kitties”, Frank Tashlin presents this sort-of sequel, recasting the boys as mice instead of cats. Although the tall thin one of the two continues to be referred to by his short fat partner as “Babbitt”, it is unknown what new name would have been supplied in place of “Catsttello” to refer to the latter. So, for purposes of this article, we’ll just call him Costello. This time, instead of a tasty canary bird, objective for the boys is a large hunk of cheese inside the refrigerator – unfortunately well-guarded by a cat. The mice employ various means and plans to get at the cheese without being massacred, one of them involving placing Costello in a toy plane somehow brought by Babbitt into their mousehole. Costello is told by Babbitt to make a three-point landing on top of the refrigerator. Costello nervously asks if Babbitt is sure this idea will work. Babbitt responds, “If this don’t work, I’ll be a – jack-ass.” Good enough for Costello, who lets Babbitt spin the prop for contact, and zooms toward the mousehole door. As with “Goofy’s Glider”, no one has measured the plane’s wingspan, and both wings are instantly clipped off as the plane passes through the door. Unable to rise off the ground, the toy nevertheless hurtles toward the refrigerator – and straight at the sleeping cat. As the cat opens his mouth for a snore, Costello and the entire plane disappear down his throat, lodge in the cat’s tail to briefly buzz him internally with the plane’s propeller, then perform an about-face and zip out of the cat’s mouth again, back into the mousehole with a crash. Assuming the posture and facial features of the animal, Costello shouts in-you-face taunts at Babbitt, “Jack-ass! Jack-ass!”

A Tale of Two Mice (Warner, 6/9/45 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) – In order to provide a return for the Abbott and Costello caricatures used to great advantage by Bob Clampett in “A Tale of Two Kitties”, Frank Tashlin presents this sort-of sequel, recasting the boys as mice instead of cats. Although the tall thin one of the two continues to be referred to by his short fat partner as “Babbitt”, it is unknown what new name would have been supplied in place of “Catsttello” to refer to the latter. So, for purposes of this article, we’ll just call him Costello. This time, instead of a tasty canary bird, objective for the boys is a large hunk of cheese inside the refrigerator – unfortunately well-guarded by a cat. The mice employ various means and plans to get at the cheese without being massacred, one of them involving placing Costello in a toy plane somehow brought by Babbitt into their mousehole. Costello is told by Babbitt to make a three-point landing on top of the refrigerator. Costello nervously asks if Babbitt is sure this idea will work. Babbitt responds, “If this don’t work, I’ll be a – jack-ass.” Good enough for Costello, who lets Babbitt spin the prop for contact, and zooms toward the mousehole door. As with “Goofy’s Glider”, no one has measured the plane’s wingspan, and both wings are instantly clipped off as the plane passes through the door. Unable to rise off the ground, the toy nevertheless hurtles toward the refrigerator – and straight at the sleeping cat. As the cat opens his mouth for a snore, Costello and the entire plane disappear down his throat, lodge in the cat’s tail to briefly buzz him internally with the plane’s propeller, then perform an about-face and zip out of the cat’s mouth again, back into the mousehole with a crash. Assuming the posture and facial features of the animal, Costello shouts in-you-face taunts at Babbitt, “Jack-ass! Jack-ass!”

Eventually, after a harrowing experience in a failed plot of lifting Costello up to the refrigerator shelf via a miniature scaffold, Costello is nearly swallowed by the cat, but makes a last-minute substitution in mid-air between himself and an ironing board with flat iron on top. Costello retrieves the cheese on the way back to the mousehole, and races it inside so fast, the cheese’s holes have to catch up with him. After all this effort, it turns out Babbitt is picky. “Swiss cheese! You know I don’t like Swiss cheese”, he says. “Well, Babbitt, you’re going to learn to like it, right now!”, shouts Costello, unwilling to take any more of Babbitt’s guff. He vigorously forces chunk after chunk of cheese down Babbitt’s throat, while turning to the camera to apologize to the audience, “I’m a bad boy.”

Snap Happy (Paramount/Famous, Little Lulu, 6/22/45 – Bill Tytla, dir.) – A simple premise, repeated for variety’s sake again and again in changing locales. Lulu wants her picture taken, and persists in trailing a freelance newspaper cameraman throughout his searches for the latest “scoop”, attempting to coax him to let her be his camera subject. The tyke’s interference repeatedly makes him miss stories, or louses up his shots again and again. When the cameraman swindles Lulu out of a quarter offered to him to take the shot, without delivering a photo, Lulu is all the more determined to get her money’s worth. In the final extended sequence, the cameraman sees a news headline about an impending Peace Conference, and determines to get there for firsthand photos of the event. He throws Lulu into the back of a passing moving van, and chains and padlocks the rear doors. In rather direct imitation of Tex Avery’s premiere Droopy episode “Dumb-Hounded”, the cameraman sets a travel itinerary he believes no one can follow, across arctic snows, tropical jungles, by taxi, train, elephant, and kangaroo pouch, finally making a passenger flight to the convention. Still nervous after all of her surprise appearances, the cameraman’s eyes dart about the cabin, as he mutters, “She might be aboard this plane.” He inspects the most suspicious of the diplomats around him, yanking the top hat off one’s head to look underneath, parting through the beard of another with his hands, and unravelling the turban off another’s brow (only to reveal a tall pointed bald head). Satisfied that his search is complete, the cameraman finally settles down in his seat to relax and enjoy the flight. Soon, he arrives at the Peace Palace, and climbs the majestic steps to the conference hall. Setting up his camera in the doorway, he states that this will be the scoop of scoops. Then his eyes bug out, as his head protrudes right through the camera box. At the conference table, all of the diplomats are engaged in licking lollipops matching Lulu’s favorite signature brand, and in the center of the table sits Lulu, who has taken charge of the whole affair. “Yoo hoo”, she waves to the cameraman, “Take my picture now!”, as the scene irises out.

Snap Happy (Paramount/Famous, Little Lulu, 6/22/45 – Bill Tytla, dir.) – A simple premise, repeated for variety’s sake again and again in changing locales. Lulu wants her picture taken, and persists in trailing a freelance newspaper cameraman throughout his searches for the latest “scoop”, attempting to coax him to let her be his camera subject. The tyke’s interference repeatedly makes him miss stories, or louses up his shots again and again. When the cameraman swindles Lulu out of a quarter offered to him to take the shot, without delivering a photo, Lulu is all the more determined to get her money’s worth. In the final extended sequence, the cameraman sees a news headline about an impending Peace Conference, and determines to get there for firsthand photos of the event. He throws Lulu into the back of a passing moving van, and chains and padlocks the rear doors. In rather direct imitation of Tex Avery’s premiere Droopy episode “Dumb-Hounded”, the cameraman sets a travel itinerary he believes no one can follow, across arctic snows, tropical jungles, by taxi, train, elephant, and kangaroo pouch, finally making a passenger flight to the convention. Still nervous after all of her surprise appearances, the cameraman’s eyes dart about the cabin, as he mutters, “She might be aboard this plane.” He inspects the most suspicious of the diplomats around him, yanking the top hat off one’s head to look underneath, parting through the beard of another with his hands, and unravelling the turban off another’s brow (only to reveal a tall pointed bald head). Satisfied that his search is complete, the cameraman finally settles down in his seat to relax and enjoy the flight. Soon, he arrives at the Peace Palace, and climbs the majestic steps to the conference hall. Setting up his camera in the doorway, he states that this will be the scoop of scoops. Then his eyes bug out, as his head protrudes right through the camera box. At the conference table, all of the diplomats are engaged in licking lollipops matching Lulu’s favorite signature brand, and in the center of the table sits Lulu, who has taken charge of the whole affair. “Yoo hoo”, she waves to the cameraman, “Take my picture now!”, as the scene irises out.

And a final honorable mention for Hockey Homicide (Disney/RKO. Goofy, 9/21/45), Jack Kinney’s manic salute to the ice-bound sport. We’ve seen its footage regarding planes before – but not in this context. In the final minutes of the destructive match between two all-goof skating teams, referee “Clean-Game Kinney” finds himself in the way of a powerful shot on goal. Not only is the ref battered by the blow, but a seemingly unlimited supply of extra pucks is knocked out of the pockets of his uniform, and onto the ice. There are tons of pucks available for each member of each team to shoot at. Narrator Doodles Weaver from Spike Jones’ musical aggregation frantically announces the action at mile-a-minute pace, running the roster of names of each team to announce over and over that “(so and so) shoots, (so and so) shoots…and EVERYBODY SHOOTS!” Amidst all this chaos of flying pucks, director Kinney throws in a stock shot of machine gun fire from a flying Spitfire, likely lifted out of either “The New Spirit” or one of the Canadian Bond shorts produced by Disney, to heighten the insanity. He repeats this pattern with periodic cutaways to random stock shots of the past, including the Wright Brothers’ flight from “Victory Through Air Power”, random shots of other sports from “How To Play Football” and “How To Play Baseball”, and even a clip out of “Pinocchio” of Monstro the whale surfacing, as if rising out of the ice on the rink! As the scoreboards rapidly run out of numbers high enough to keep track of the pucks entering the goals, and the red light bulbs on the goal nets explode, the fans clamber over the railings to get into the action, and the brawling. Before long, they are all you can see on the ice, while we find safely clustered together in the stadium’s upper seating the members of the teams, relaxing to watch the show, while Mr. Weaver concludes, “And that’s why ice hockey is known as a spectator sport.”

And a final honorable mention for Hockey Homicide (Disney/RKO. Goofy, 9/21/45), Jack Kinney’s manic salute to the ice-bound sport. We’ve seen its footage regarding planes before – but not in this context. In the final minutes of the destructive match between two all-goof skating teams, referee “Clean-Game Kinney” finds himself in the way of a powerful shot on goal. Not only is the ref battered by the blow, but a seemingly unlimited supply of extra pucks is knocked out of the pockets of his uniform, and onto the ice. There are tons of pucks available for each member of each team to shoot at. Narrator Doodles Weaver from Spike Jones’ musical aggregation frantically announces the action at mile-a-minute pace, running the roster of names of each team to announce over and over that “(so and so) shoots, (so and so) shoots…and EVERYBODY SHOOTS!” Amidst all this chaos of flying pucks, director Kinney throws in a stock shot of machine gun fire from a flying Spitfire, likely lifted out of either “The New Spirit” or one of the Canadian Bond shorts produced by Disney, to heighten the insanity. He repeats this pattern with periodic cutaways to random stock shots of the past, including the Wright Brothers’ flight from “Victory Through Air Power”, random shots of other sports from “How To Play Football” and “How To Play Baseball”, and even a clip out of “Pinocchio” of Monstro the whale surfacing, as if rising out of the ice on the rink! As the scoreboards rapidly run out of numbers high enough to keep track of the pucks entering the goals, and the red light bulbs on the goal nets explode, the fans clamber over the railings to get into the action, and the brawling. Before long, they are all you can see on the ice, while we find safely clustered together in the stadium’s upper seating the members of the teams, relaxing to watch the show, while Mr. Weaver concludes, “And that’s why ice hockey is known as a spectator sport.”

Peace time returns next week. But then, when is life ever peaceful for a toon?

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Babbitt and… Moustello?

The music for “all-plastic instruments” that Donald listens to on the radio is played by a vibraphone (whose bars and resonators are made of aluminium) and a steel-bodied guitar. In 1944, the only all-plastic instruments around would have been ocarinas. Still, it’s a real toe-tapper of a tune.

The gag at the end of “Fisherman’s Luck”, where the fish on the line disgorge each other until only a very small one is left on the hook, was previously used in Van Beuren’s “Jolly Fish” (1932). I suppose the “devil of the deep” could be a marlin, though its rostrum is much too short; but it has a rayed dorsal fin, so it’s definitely not a shark. Cartoon ichthyology is an inexact science anyway. The amorous fish that puckers up for Sourpuss would be either a kissing gourami or a sweetlips.

Popeye sounds weird in “For Better or Nurse”. Jack Mercer must have been in the army then.

I’ve never seen “Snap Happy” before. What a bizarre premise! Imagine anyone making a cartoon today about a little girl determined to get a strange man to photograph her.

Interesting to see Goofy sweeping the ice between periods in “Hockey Homicide”. I guess the Zamboni hadn’t been invented yet.

Among the “Post War Inventions” (Terrytoons/Fox, 23/3/45 — Connie Rasinski, dir.) dreamt up by Gandy Goose — including dehydrated food pills, robot waiters, and television — are a number of airplanes and other flying machines, which buzz around the cavernous exhibition hall and occasionally send Gandy and Sourpuss scurrying for cover. One of them looks remarkably like a Stealth Bomber.

I believe the Jimmy Durante caricature in “In the Aleutians” is meant to be an elephant seal. Its long, droopy snout makes it a natural for a Durante character.

I noticed a couple of gags I’m surprised got passed the Hays Code; the “Sexquire” magazine on “Goofy News Views” and the bra with nipples on “Snap Happy”.

>> Popeye sounds weird in “For Better or Nurse”

Bluto sounds weird too. More high-pitched than Jackson Beck’s usual voice.

“Nimbus Libere”, or “Nimbus Liberated” (1944 — Raymond Jeannin [aka “Cal”], dir.), is a three-minute propaganda film commissioned by the Vichy government of France just months before the D-Day invasion. It is notable for its unauthorised use of several American cartoon stars as well as Professor Nimbus, a popular French comic strip character.

Listening to the radio with his family, Professor Nimbus tunes in to a broadcast from London. The announcer (a Jewish stereotype of the Nazi era, all nose, lips and effusive gestures) tells the French people that they will soon be liberated by the Allies. Overhead, the planes of the U.S. Air Force are manned by none other than Goofy, Felix the Cat, Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and Popeye. Dimwitted Mickey has trouble locating France on his map of France, while Popeye wonders whether the spinach in France is better than what he’s used to. Meanwhile, the Nimbus family cheerfully look forward to being liberated and able to get fine food, coffee and cigarettes again. Then the Allies drop their bombs, each labeled “Made in the U.S.A.”, and reduce the Nimbus home to rubble. The Angel of Death, scythe in his bony hand, hovers over the ruins, turns off the radio, and chuckles. Fin.

Andre Daix, the creator of Professor Nimbus, was a member of the fascist Francist movement and an outspoken anti-Semite. Fleeing into exile at war’s end, he was tried in absentia as a Nazi collaborator, found guilty and sentenced to 20 years hard labour. He ultimately returned to France under an assumed name after many years in Portugal and South America. Raymond Jeannin, the director of “Nimbus Libere”, was hired on the strength of his only previous film, “La Nuit Enchante [The Enchanted Night]”, where he demonstrated an ability to copy other people’s cartoon characters and little else. He was arrested as a collaborator but never tried, and for the rest of his long life (he died in 2007) he never worked in film again.

“Nimbus Libere” was lost for decades before being discovered in an unlabeled canister and restored by Serge Bromberg of Lobster Films. It was included in Thunderbean’s “Cartoons for Victory” collection, along with Eshbaugh’s “Cap’n Cub”.

Some years ago, we ran “Hockey Homicide” at Cinecon as a little hat-tip to Kinney’s centennial. Imagine our surprise when some maroon came out screaming at us for running such a “violent” cartoon. We politely pointed out that anything titled “Hockey Homicide” would probably have some violence, and anyway it was a Disney cartoon! (And only seven minutes long.) Sputtering, he stormed out of the theatre to a hearty chorus of “Good riddance!”