1942 and ‘43 (with one stray included here from ‘44) continued to bring us self-referential cartoons, ones breaking the fourth wall, and immersing characters into the movie-going experience and the lives of their narrators. Among today’s offerings are two landmark efforts by Tex Avery, more Warner zaniness, some Disney “How To”’s and a wartime Oscar nominee, and a Popeye classic which proves multi-dimensional in its visual approach.

Fresh Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 8/15/42 – I (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Freleng’s version of “fat” Elmer is in pursuit of Bugs again – this time as a Canadian Mountie, allegedly with a list of crimes Bugs has committed a mile long, including “conduct unbecoming to a wabbit.” Bugs is his usual wily self, always one step ahead – including handcuffing Elmer to a cartoon bomb. Elmer searches frantically for his keys, only to find that Bugs is holding the same. Bugs takes his own leisurely time searching out the right key, while Elmer utterly panics. (Bugs stops at one key on Elmer’s ring, long enough to utter a wolf whistle, suggesting the key to a lady’s apartment.) When Bugs finally removes the right key, the bomb goes off – so Bugs simply tosses the key away, aware that Elmer will have no further use for it. There is a lot of chasing through snowbanks, each character leaving silhouette impressions of himself in the snow when passing through. Inexplicably, the silhouette of a shapely girl appears in one snowbank, leaving Elmer to scratch his head as to what he just missed. Elmer finally bursts into tears at being unable to catch the wabbit, calling himself a “disgwace to the wegiment”. Bugs is a sport, and surrenders to the arrest to save Elmer’s reputation. Bugs is placed before a firing squad at the mountie post. “Before you die, you may have one wast wish”, says Elmer. Bugs thinks about it, then breaks into song: “I wish I was in Dixie. Hooray, Hooray.” Suddenly, the entire scene dissolves, as the mountie post disappears from the background, replaced by a Southern cotton-field setting, and everyone in the shot, Bugs, Elmer, and the firing squad, are transformed into the outfits and blackface makeup of minstrel performers, singing “Camptown Races.” Bugs, ever aware that the audience might be wondering about what just happened, turns to the theater crowd just beyond the screen in the blackness, and observes, “Fantastic, isn’t it?” (Watch for a recurring ink and paint error in the last shot, as the paint crew can’t seem to decide whether Elmer’s nose should be flesh-tone or black.)

Fresh Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 8/15/42 – I (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Freleng’s version of “fat” Elmer is in pursuit of Bugs again – this time as a Canadian Mountie, allegedly with a list of crimes Bugs has committed a mile long, including “conduct unbecoming to a wabbit.” Bugs is his usual wily self, always one step ahead – including handcuffing Elmer to a cartoon bomb. Elmer searches frantically for his keys, only to find that Bugs is holding the same. Bugs takes his own leisurely time searching out the right key, while Elmer utterly panics. (Bugs stops at one key on Elmer’s ring, long enough to utter a wolf whistle, suggesting the key to a lady’s apartment.) When Bugs finally removes the right key, the bomb goes off – so Bugs simply tosses the key away, aware that Elmer will have no further use for it. There is a lot of chasing through snowbanks, each character leaving silhouette impressions of himself in the snow when passing through. Inexplicably, the silhouette of a shapely girl appears in one snowbank, leaving Elmer to scratch his head as to what he just missed. Elmer finally bursts into tears at being unable to catch the wabbit, calling himself a “disgwace to the wegiment”. Bugs is a sport, and surrenders to the arrest to save Elmer’s reputation. Bugs is placed before a firing squad at the mountie post. “Before you die, you may have one wast wish”, says Elmer. Bugs thinks about it, then breaks into song: “I wish I was in Dixie. Hooray, Hooray.” Suddenly, the entire scene dissolves, as the mountie post disappears from the background, replaced by a Southern cotton-field setting, and everyone in the shot, Bugs, Elmer, and the firing squad, are transformed into the outfits and blackface makeup of minstrel performers, singing “Camptown Races.” Bugs, ever aware that the audience might be wondering about what just happened, turns to the theater crowd just beyond the screen in the blackness, and observes, “Fantastic, isn’t it?” (Watch for a recurring ink and paint error in the last shot, as the paint crew can’t seem to decide whether Elmer’s nose should be flesh-tone or black.)

How To Swim (Disney/RKO, Goofy, 10/23/42 – Jack Kinney, dir.) and “How To Play Golf” (Disney/RKO, Goofy, 3/9/44 – Jack Kinney, dir.) add a new narration wrinkle to the now-standard interplay between narrator and the Goof common to his sports and “how to” films. An on-screen comparison is made between the actions of Goofy and an idealized animated graphic “chart”. consisting of a bare white simplified outline of the perfect dive or golf stroke. In the diving exhibition, Goofy joins the animated chart on the platform, taking the lead in proceeding out to the end of the diving board. Goofy’s long foot catches its toe in the edge of the leather padding covering the outmost edge of the board, and Goofy stumbles, his body protruding out past the end of the board, while his foot remains stuck fast. The chart outline takes on a weight and mass of its own, not merely passing over or through the solid frame of the Goof, but hopping upon him, using Goofy’s face as the launch-off point for the chart’s own graceful dive, and stepping upon him heavily in the process, leaving Goof’s face vibrating.

How To Swim (Disney/RKO, Goofy, 10/23/42 – Jack Kinney, dir.) and “How To Play Golf” (Disney/RKO, Goofy, 3/9/44 – Jack Kinney, dir.) add a new narration wrinkle to the now-standard interplay between narrator and the Goof common to his sports and “how to” films. An on-screen comparison is made between the actions of Goofy and an idealized animated graphic “chart”. consisting of a bare white simplified outline of the perfect dive or golf stroke. In the diving exhibition, Goofy joins the animated chart on the platform, taking the lead in proceeding out to the end of the diving board. Goofy’s long foot catches its toe in the edge of the leather padding covering the outmost edge of the board, and Goofy stumbles, his body protruding out past the end of the board, while his foot remains stuck fast. The chart outline takes on a weight and mass of its own, not merely passing over or through the solid frame of the Goof, but hopping upon him, using Goofy’s face as the launch-off point for the chart’s own graceful dive, and stepping upon him heavily in the process, leaving Goof’s face vibrating.

In “Golf”, the chart takes on a life and personality of his own, stepping out of his own graphics to correct Goofy’s grip and swing, chastising him when he is tempted to cheat and break the ultimate golfing rule about hitting the ball where it lies, slapping Goofy in congratulatory manner upon the back when he finally escapes a sand trap by inadvertent luck, and panicking alongside the Goof when Goofy takes the golf rules too literally, and hits the ball off of an angry bull. After a harrowing chase, the chart is still in the midst of the action, carousing with beer and good cheer at the “19th hole” clubhouse with Goofy, and the bull, after the game.

Me Musical Nephews (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 12/25/42 – Seymour Keneitel, dir.) – A memorable Christmas present, though itself containing no holiday-themed content. Popeye’s four nephews attempt to entertain Popeye, back from a voyage, with a musicale recital in their living room, playing an off-key rendition of “Sweet and Low”. The hour is late, and Popeye is nodding off from fatigue and general boredom. The kids notice, and deliberately triple the tempo in swingtime to jar Popeye awake. Popeye suggests bedtime, but the kids insist upon being told a story. Popeye sees a deal in the works, bargaining with the kids for them to go to sleep if he gives them a story. However, Popeye cheats, improvising a fairy tale that is truly fractured, about a “Big red Hooding Ride who sat on a tuffet” and “chopped down the beanstalk”. The kids claim they were robbed, but Popeye carries all four off to the bedroom anyway. The kids kneel by their bedsides in prayer, offering verbal blessings to Olive, Wimpy Blito, and as an afterthought, Popeye – then zip back into praying position for a further afterthought – “and all the people who come to see our pictures.”

Me Musical Nephews (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 12/25/42 – Seymour Keneitel, dir.) – A memorable Christmas present, though itself containing no holiday-themed content. Popeye’s four nephews attempt to entertain Popeye, back from a voyage, with a musicale recital in their living room, playing an off-key rendition of “Sweet and Low”. The hour is late, and Popeye is nodding off from fatigue and general boredom. The kids notice, and deliberately triple the tempo in swingtime to jar Popeye awake. Popeye suggests bedtime, but the kids insist upon being told a story. Popeye sees a deal in the works, bargaining with the kids for them to go to sleep if he gives them a story. However, Popeye cheats, improvising a fairy tale that is truly fractured, about a “Big red Hooding Ride who sat on a tuffet” and “chopped down the beanstalk”. The kids claim they were robbed, but Popeye carries all four off to the bedroom anyway. The kids kneel by their bedsides in prayer, offering verbal blessings to Olive, Wimpy Blito, and as an afterthought, Popeye – then zip back into praying position for a further afterthought – “and all the people who come to see our pictures.”

In super-speed, Popeye prepares for a comfortable night’s sleep in the next room. But the kids, not a bit sleepy, are flat-out bored at being sent to bed so early. They lie listless in their beds, one rubbing his toes across the brass bars of his bed headboard, another repeatedly thumbing through the pages of a book, a third making slapping sounds as he attempts to swat a fly, and the fourth plucking a protruding spring from his mattress. They suddenly notice that they can do these sounds in combined rhythmic fashion, and the idea hatches for an impromptu jam session. Refining and updating basic ideas dating back to Fleischer’s “The Kids in the Shoe”, the kids start using every object in the room as effective substitute for a musical instrument. Brass bars from their beds become well-tuned horns. A Flit gun substitutes for a slide trombone. Radiator pipes make excellent vibes. Suspenders become the source of string bass low notes. And even a painting of a ship’s bell on the wall sounds a reverberating bong when tapped with a drumstick.

Frame from original end-title.

Sadly, no negative exists for the complete final shot of the film. However, an extremely blurry source, taken in all likelihood from a very-splicy 16mm reference print, has surfaced on a super 8mm release produced in the public domain. The ending, spliced together with clear frames from the original as far as existing, is imbedded herewith as a bonus extra for your enjoyment, exemplifying the theme of this trail. (Comparisons Below: 1. A.A.P. print, 2. The Popeye Show, 3. Popeye 75th Anniversary DVD, 4. Popeye The Sailor: 1941-1943 Volume Three, and 5. Original film)

Dumb-Hounded (MGM, Droopy, 3/23/43 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Avery’s third go-round with the idea of a pursuer who’s everywhere. He does not return to the mistake of Bugs Bunny’s “Tortoise Beats Hare” by revealing the secret of the pursuer’s ability at the outset of the cartoon. Instead, he opts to return more closely to the storytelling style of Porky Pig’s “The Blow-Out” – offering no explanation whatsoever as to how the hero is always wherever the villain goes. Yet, he continues to improve on his past. While “The Blow-Out” produced very little laughter, the pursuit of a mad bomber being played instead more for dramatic tension, “Dumb-Hounded” is played purely for belly-laughs, with every reappearance of the pursuing hound (Droopy, in his debut appearance) calculated to be more and more preposterously impossible.

Dumb-Hounded (MGM, Droopy, 3/23/43 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Avery’s third go-round with the idea of a pursuer who’s everywhere. He does not return to the mistake of Bugs Bunny’s “Tortoise Beats Hare” by revealing the secret of the pursuer’s ability at the outset of the cartoon. Instead, he opts to return more closely to the storytelling style of Porky Pig’s “The Blow-Out” – offering no explanation whatsoever as to how the hero is always wherever the villain goes. Yet, he continues to improve on his past. While “The Blow-Out” produced very little laughter, the pursuit of a mad bomber being played instead more for dramatic tension, “Dumb-Hounded” is played purely for belly-laughs, with every reappearance of the pursuing hound (Droopy, in his debut appearance) calculated to be more and more preposterously impossible.

Droopy is cast as a police bloodhound, in pursuit of a convict wolf, still dressed in prison stripes fresh from his escape over the wall. Droop is instantly aware of his onlooking audience from the first scene of his appearance, greeting the public with his signature deadpan introduction: “Hello, all you happy people.” As Droopy roams the streets at molasses-pace looking for clues, he passes a barrel. A hand holding a sign pops out the top, reading, “No, I’m not in here.” Satisfied, Droopy moves on. Out of the barrel appears the wolf, who high-tails it to his hideout, bolting the door. “Sure was a cinch getting rid of that little runt”. “That’s what you think, brother”, responds the voice of Droopy, sitting right behind the wolf, and looking him nose to nose when he turns. To magnify the impossibility of what we are seeing, the wolf pivots 180 degrees, reopens the hideout door to make an escape, and finds Droopy standing calmly in the doorway, already outside. He informs the wolf that he is going to go and call the cops, and instructs the wolf not to move. The wolf gives his solemn oath that he won’t move an inch – but the second the door closes, escapes out the fire escape, and engages in possibly the fastest and wildest round-the-globe jaunt ever committed to film. He utilizes practically every possible mode of transportation – taxi, motor scooter, train, ocean liner, jeep, plane, and horseback, reaching a remote cabin in the woods. Who is just inside the door? “Ya moved, didn’t ya”, observes Droopy. The wolf, after one of an ongoing series of wilder and wilder shock takes, gags and binds Droopy to the wall. Then, the entire travel montage is run in reverse at double tempo, returning the wolf to the original hideout. Waiting on the bed is Droopy, asking “Enjoy your trip?” The confused wolf demands an explanation. “How did you get back here, anyway?” All he (and the audience) gets for an answer is “Let’s not get nosy, bub.”

Much of the film is summed up by Droopy in the midst of the chase, addressing the audience with a line almost borrowed verbatim from Cecil Turtle in “Tortoise Beats Hare” – “ I surprise him like this all through the picture.” He does indeed, and the wolf continues to attempt to elude him in panicked fashion – most notably demonstrating his own awareness of the meduim in which he is appearing by rounding a corner of a city street at too-high speed, and running right past the moving sprocket-edge of the celluloid film, into blank white space. Running on air, the wolf corrects his path, regaining a footing on the film, and eventually running up the side of what seems the cartoon equivalent of the Empire State Building (a building so tall, the outlines of several states are scen below from a vantage point at its summit). The Droop is of course waiting for him on the roof. The wolf claims he’s plenty fed up with this, and threatens that if Droopy comes one step closer, he’ll jump. Unintimidated, Droopy quite deliberately sidles up to the wolf’s feet. The wolf makes good on his threat, plummeting in a fall rivaling “The Heckling Hare” for duration. He is in free fall so long, an undertaker is able to leap out of an office window about twenty stories down, join the wolf in mid-air to take measurements for a coffin, then leap back into the building before reaching the ground. As the pavement looms below, the Wolf stiffens his pose, and screeches to a stop, an inch above the sidewalk. “Good brakes”, he tells the audience. Back on the roof, Droopy is shown dropping over the roof ledge a boulder so large, it could masquerade as the Rock of Gibraltar. He again addresses the audience person-to-person, with the grizzly observation, “Yes, you’re right. It is gruesome.” Inscribed on the side of the falling boulder, we read, “This rock knocks him colder ‘n a wet mackerel!” As the wolf crosses a street, the shadow of the boulder looms above hum – but we never see the actual impact. Instead, dropping into the frame with a thud where the boulder should be, falls the front page of a newspaper, with headline, “Killer Captured.” Droopy receives a reward of an armful of stacks of money in a public ceremony. After calmly saying “Thank you”. Droopy lapses completely out of character, flashing a surprise smile, throwing money into the air and yelling “Yahoo” while blowing a party horn and firing pistols in celebration. Suddenly, he stops, reverting back to form, again addressing the audience with an underplayed, “I’m happy”, for the iris out.

Much of the film is summed up by Droopy in the midst of the chase, addressing the audience with a line almost borrowed verbatim from Cecil Turtle in “Tortoise Beats Hare” – “ I surprise him like this all through the picture.” He does indeed, and the wolf continues to attempt to elude him in panicked fashion – most notably demonstrating his own awareness of the meduim in which he is appearing by rounding a corner of a city street at too-high speed, and running right past the moving sprocket-edge of the celluloid film, into blank white space. Running on air, the wolf corrects his path, regaining a footing on the film, and eventually running up the side of what seems the cartoon equivalent of the Empire State Building (a building so tall, the outlines of several states are scen below from a vantage point at its summit). The Droop is of course waiting for him on the roof. The wolf claims he’s plenty fed up with this, and threatens that if Droopy comes one step closer, he’ll jump. Unintimidated, Droopy quite deliberately sidles up to the wolf’s feet. The wolf makes good on his threat, plummeting in a fall rivaling “The Heckling Hare” for duration. He is in free fall so long, an undertaker is able to leap out of an office window about twenty stories down, join the wolf in mid-air to take measurements for a coffin, then leap back into the building before reaching the ground. As the pavement looms below, the Wolf stiffens his pose, and screeches to a stop, an inch above the sidewalk. “Good brakes”, he tells the audience. Back on the roof, Droopy is shown dropping over the roof ledge a boulder so large, it could masquerade as the Rock of Gibraltar. He again addresses the audience person-to-person, with the grizzly observation, “Yes, you’re right. It is gruesome.” Inscribed on the side of the falling boulder, we read, “This rock knocks him colder ‘n a wet mackerel!” As the wolf crosses a street, the shadow of the boulder looms above hum – but we never see the actual impact. Instead, dropping into the frame with a thud where the boulder should be, falls the front page of a newspaper, with headline, “Killer Captured.” Droopy receives a reward of an armful of stacks of money in a public ceremony. After calmly saying “Thank you”. Droopy lapses completely out of character, flashing a surprise smile, throwing money into the air and yelling “Yahoo” while blowing a party horn and firing pistols in celebration. Suddenly, he stops, reverting back to form, again addressing the audience with an underplayed, “I’m happy”, for the iris out.

• “Dumb-Hounded” is complete on Facebook video at THIS LINK.

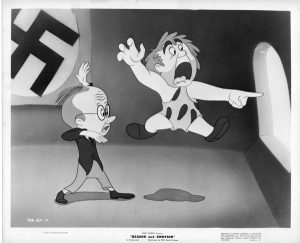

Reason and Emotion (Disney/RKO. 4/27/43 = Bill Roberts. dir.) – The original version of “Inside Out”, with a wartime twist. A narrator (Frank Graham, who was working for three studios at the time, including as Avery’s wolf and Columbia’s Fox and Crow) introduces us to two characters inside the mind of every human. Reason, an educated, erudite, bespectacled miniature thinking man, and Emotion, a cave man wearing a spotted leopard leotard a la Fred Flintstone, and armed with a club. They occupy a cavity in the human skull, which, as adulthood progresses, develops a control panel resembling the driver’s dashboard and steering wheel of an auto. Looking out at the world through the eye window, they control human destiny. The narrator takes us back to introduce us to junior versions of them inside the mind of a toddler. At first, Emotion has the place all to himself (just the same as Joy in the Pixar feature), as Reason isn’t born yet. Thus, the toddler freely does foolhardy things, like pulling a cat’s tail, and curiously tumbling down a flight of stairs. Reason suddenly materializes, dressed in a baby bonnet on account of just being born, and cautions Emotion that this incident wouldn’t have happened had he been on the scene. Emotion isn’t too happy about sharing living quarters, and cautions Reason that he’ll be the boss around here. “Time will tell”, responds Reason. As our study evolves to young adulthood, we find Reason occupying the newly-installed driver’s seat, with Emotion relegated to the role of back-seat driver. As the man being run by these two walks through town, Emotion complains he’s bored, and wants to live it up. Emotion spots a pretty girl through the eye window, and gets over-excited. While Reason cautions that they must show respect for womanhood, Emotion remarks, “Aw, they like the rough stuff.” Speaking of rough stuff, Emotion pulls out his club, bops Reason on the head, and takes the wheel, remarking that “We’re goin’ places.” He whirls the man around to address the girl, with a curt, “Hi, babe. Goin’ my way?” All he gets for his effort is a firm slap across the face by the girl.

Reason and Emotion (Disney/RKO. 4/27/43 = Bill Roberts. dir.) – The original version of “Inside Out”, with a wartime twist. A narrator (Frank Graham, who was working for three studios at the time, including as Avery’s wolf and Columbia’s Fox and Crow) introduces us to two characters inside the mind of every human. Reason, an educated, erudite, bespectacled miniature thinking man, and Emotion, a cave man wearing a spotted leopard leotard a la Fred Flintstone, and armed with a club. They occupy a cavity in the human skull, which, as adulthood progresses, develops a control panel resembling the driver’s dashboard and steering wheel of an auto. Looking out at the world through the eye window, they control human destiny. The narrator takes us back to introduce us to junior versions of them inside the mind of a toddler. At first, Emotion has the place all to himself (just the same as Joy in the Pixar feature), as Reason isn’t born yet. Thus, the toddler freely does foolhardy things, like pulling a cat’s tail, and curiously tumbling down a flight of stairs. Reason suddenly materializes, dressed in a baby bonnet on account of just being born, and cautions Emotion that this incident wouldn’t have happened had he been on the scene. Emotion isn’t too happy about sharing living quarters, and cautions Reason that he’ll be the boss around here. “Time will tell”, responds Reason. As our study evolves to young adulthood, we find Reason occupying the newly-installed driver’s seat, with Emotion relegated to the role of back-seat driver. As the man being run by these two walks through town, Emotion complains he’s bored, and wants to live it up. Emotion spots a pretty girl through the eye window, and gets over-excited. While Reason cautions that they must show respect for womanhood, Emotion remarks, “Aw, they like the rough stuff.” Speaking of rough stuff, Emotion pulls out his club, bops Reason on the head, and takes the wheel, remarking that “We’re goin’ places.” He whirls the man around to address the girl, with a curt, “Hi, babe. Goin’ my way?” All he gets for his effort is a firm slap across the face by the girl.

Our point of view switches to the woman, as the narrator asks her, “May we borrow your pretty head for the moment?” A dissolve shows what goes on inside her skull, where a cave girl Emotion and prim-dressed female Reason also sit in the control center. Reason is again at the wheel, but the cave girl complains that she shouldn’t have slapped the guy, as he was cute. Reason remarks that they must act like a lady. Emotion just wants to have fun, and, spotting a restaurant, proclaims she wants to eat. Reason states she’s not very hungry, but maybe something light like tea and toast. Emotion insists on a club sandwich with potato salad, ice cream, and other delights. She yanks Reason’s hair, then pulls Reason’s hat over her eyes, while taking the wheel. The food is ordered fast and furiously, while Reason, cautioning that they’re supposed to be on a diet, watches with horror as various graphs within the brain chamber show a the outlines of a double-chin developing, a bulging belly, and a butt that fills and overhangs the graph chart.

The film now shifts to a wartime angle. An average man is shown, following the news on radio and in headlines about the battles. He begins to react in increasing terror and panic to every negative story from the battlefront, and every rumor that we’re losing the war. Phantom gossipers appear around his easy chair, transforming into alarming images of jabbering parrots, talking skeletons, and other images that send his eyes spinning. Inside his head, Emotion is going out of control, and while Reason concludes that it’s all a lot of hearsay, Emotion yells, “I’ll believe anything I want to.” Emotion pulls out the steering column from the dashboard, and raises it above Reason’s head to strike him down. The narrator addresses the two directly. “That’s right, Emotion. Go ahead. Put Reason out of the way. That’s great…for Hitler.” Emotion stops cold, then exchanges glances with Reason, and back to the camera, as if to say, “What does he mean by that?” Emotion settles into his seat, facing the camera, to listen to the narrator’s explanation. The narrator now shifts us to a speech in Germany by Adolf, and inside the mind of an average Nazi. Here, Emotion wears a spiked helmet, firmly in command of the driver’s seat, while Reason meekly complains in the rear without a seat, being paid little or no attention to. Hitler uses four tactics in his speech – fear of concentration camps and Gestapo, sympathy (“I only want peace, but they force me into war”), pride in Arian superiority, and hate for democracy. Reason meekly claims it’s all lies, while Emotion swells three times in size from pride, bops Reason on the head, and insists that the Fuehrer is a genius and a great leader, forcing Reason to heil. In the end, Reason is encircled by barbed wire and kept at bayonet point by Emotion in a small circle marked off as a concentration camp, while Reason goose-steps in march around him, and so does the Nazi they control, into the battlefield. The narrator refers to it as madness, with Reason enslaved.

The film now shifts to a wartime angle. An average man is shown, following the news on radio and in headlines about the battles. He begins to react in increasing terror and panic to every negative story from the battlefront, and every rumor that we’re losing the war. Phantom gossipers appear around his easy chair, transforming into alarming images of jabbering parrots, talking skeletons, and other images that send his eyes spinning. Inside his head, Emotion is going out of control, and while Reason concludes that it’s all a lot of hearsay, Emotion yells, “I’ll believe anything I want to.” Emotion pulls out the steering column from the dashboard, and raises it above Reason’s head to strike him down. The narrator addresses the two directly. “That’s right, Emotion. Go ahead. Put Reason out of the way. That’s great…for Hitler.” Emotion stops cold, then exchanges glances with Reason, and back to the camera, as if to say, “What does he mean by that?” Emotion settles into his seat, facing the camera, to listen to the narrator’s explanation. The narrator now shifts us to a speech in Germany by Adolf, and inside the mind of an average Nazi. Here, Emotion wears a spiked helmet, firmly in command of the driver’s seat, while Reason meekly complains in the rear without a seat, being paid little or no attention to. Hitler uses four tactics in his speech – fear of concentration camps and Gestapo, sympathy (“I only want peace, but they force me into war”), pride in Arian superiority, and hate for democracy. Reason meekly claims it’s all lies, while Emotion swells three times in size from pride, bops Reason on the head, and insists that the Fuehrer is a genius and a great leader, forcing Reason to heil. In the end, Reason is encircled by barbed wire and kept at bayonet point by Emotion in a small circle marked off as a concentration camp, while Reason goose-steps in march around him, and so does the Nazi they control, into the battlefield. The narrator refers to it as madness, with Reason enslaved.

We return to the head of the American. The narrator addresses each of our protagonists. He tells Reason it is his job to think, to plan, to discriminate, and for Emotion to be a fine emotion with love for his country, his life, and his freedom. The two battling buddies shake hands, and in the final scene, are seen inside the head of a bomber pilot, dressed themselves in flight gear, with Reason again at the controls and Emotion as co-pilot. With this mindset, the narrator concludes, over images of a squadron of planes on route to the enemy lines, “We will go on and do the job we’ve set out to do – and do it right.” Nominated for an Academy Award.

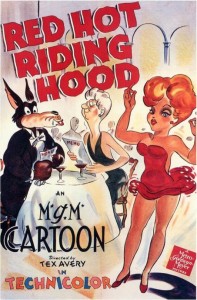

Red Hot Riding Hood (MGM, 5/8/43 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Cartoon self-awareness provides the set-up for the start of this story. A cloying radio-kiddie-show type narrator begins to tell the tale of Little Red Riding Hood in purely traditional fashion, with introductory images of little Red, feeble Grandma in her bed, and the wolf waiting in the woods. As the narration continues, the wolf begins to glare in irritation at the camera, then suddenly shouts, “AW, STOP IT!”, throwing his hat to the ground in disgust. He repeats the narrator’s words in mamby-pamby fashion, then rants, “I’m fed up with that sissy stuff. It’s the same old story over and over. If you can’t do this thing a new way, Bud, I quit.” The camera cuts to Little Red, who also throws down her goodie basket, adding “Me too. Every cartoon studio in Hollywood has done it this way.” The scene cuts to Grandma’s bed, where Granny chimes in, “Yes, I’m plenty sick of it myself.” Little Red and the wolf join her at the bedside, all complaining at once to the narrator, so you can hardly make out the words being said, until Grandma talks for a second longer than the others, with the words slipping out “It smells.” “Okay, okay, ALL RIGHT!”, finally responds the narrator. We’ll do the story in a new way.” The scene dissolves to a neon sign, with volts of electricity visibly leaping between the letters, bearing the title, “Red Hot Riding Hood – Something new has been added”. The narrator now assumes the voice of a street-wise toughie. “Once upon a time, there was a wolf.” At the corner of Hollywood and Vine, the wolf cruises in a long black limousine convertible, howling and whistling at pretty babes walking by. Grandma now resides in a swank penthouse apartment, with a neon sign atop its roof with an image of a beckoning finger, reading “Grandma’s Joint – Come up and see me sometime.” Grandma herself is modernized, lounging on a plush sofa in evening attire, reading a magazine titled “Oomph”. And Red, now fully mature (oh, brother, yes), has an act at a Hollywood night club, called “The Sunset Strip – 30 gorgeous girls – No cover.” What follows is well-known screen legend, as the seductive “Red” struts her stuff on stage in superb Preston Blair animation, to the tune of Bobby Troup’s “Daddy”. Avery pulls out all the stops on wild-take reactions of the aroused wolf at a ringside table (though he would prove in several subsequent cartoons to have a literal “Million of ‘em” in his wild-takes grab bag). But the wolf never gets to intercept Red in her evening visit to Grandma’s, as Grandma makes the wolf her target-for-tonight in a libido-driven loving frenzy. The wolf barely escapes with his life, leaping out a penthouse window, and falling to the street below, his head stuck in the framework of a street light. He returns to the nightclub to drown his sorrows, claiming that he’ll kill himself before he’ll look at another woman. The stage curtains part, as Red makes her appearance for another performance. The wolf produces a pistol, blows his brains out, and falls dead to the floor – but his ghost rises, to carry on with all the wild takes at Red, just as before.

• The full cartoon of Red Hot Riding Hood is on ok.ru

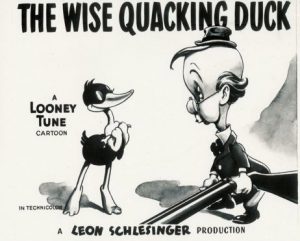

The Wise Quacking Duck (Warner, Daffy Duck, 5/12/43 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – A Mr. Meek (a personification of Bill Thompson’s Wallace Wimple character from the “Fibber McGee and Molly” radio show), approaches the poultry coop of his farm, carrying an axe. He informs the audience that his wife, Sweetie-Puss, has ordered that if he doesn’t fetch her a duck for dinner, “she’ll cook my goose.” Daffy Dick misses the chopping blade by a split-second, complaining that someone’s liable to get hurt with that thing. From here, the chase is on , mostly inside the Meek abode. At one point, Daffy runs in a wide loop around a large room, but gets stopped in his tracks when a rifle held by Meek looms out in front of him, catching his beak in its barrel. Meek, on the other end of the rifle, opens the oven door, and orders Daffy inside. Daffy prepares to enter in his own way – performing an extended strip-tease of his feathery coat, as if it were a one-poece garment. As the feathers finally fall, Daffy is revealed in boxer shorts in the roasting pan, and holds up two sprigs of celery in front of him as if hiding behind a fan. But it doesn’t take long before the chase is on again, sliding down a staircase banister (Daffy positioning a sculpture holding a bow and arrow at the foot of the stairs, leaving Meek to get the point in his rear-end), and with Daffy impersonating Jerry Colonna as a fake door-to-door fortune teller. In identical animation as before, Daffy rounds the room again, and comes face to face with the muzzle of Meek’s rifle. Daffy brings the proceedings to a momentary pause, addressing the camera. “No, no! Not twice in the same picture!” Meek blasts away Daffy’s feathers again in a single shot, then tosses him in the roasting pan and into the oven. Meek turns on the gas of the stove to maximum heat. Blood-curdling screams are heard from within the oven, chilling Meek to the bone. He quickly shuts off the gas, and peers in to pull the roasting pan out into view. Daffy casually reclines in the pan, remarking, “Say, now you’re cookin’ with gas”, then zanily begins to baste himself with a ladle, for the iris out.

The Wise Quacking Duck (Warner, Daffy Duck, 5/12/43 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – A Mr. Meek (a personification of Bill Thompson’s Wallace Wimple character from the “Fibber McGee and Molly” radio show), approaches the poultry coop of his farm, carrying an axe. He informs the audience that his wife, Sweetie-Puss, has ordered that if he doesn’t fetch her a duck for dinner, “she’ll cook my goose.” Daffy Dick misses the chopping blade by a split-second, complaining that someone’s liable to get hurt with that thing. From here, the chase is on , mostly inside the Meek abode. At one point, Daffy runs in a wide loop around a large room, but gets stopped in his tracks when a rifle held by Meek looms out in front of him, catching his beak in its barrel. Meek, on the other end of the rifle, opens the oven door, and orders Daffy inside. Daffy prepares to enter in his own way – performing an extended strip-tease of his feathery coat, as if it were a one-poece garment. As the feathers finally fall, Daffy is revealed in boxer shorts in the roasting pan, and holds up two sprigs of celery in front of him as if hiding behind a fan. But it doesn’t take long before the chase is on again, sliding down a staircase banister (Daffy positioning a sculpture holding a bow and arrow at the foot of the stairs, leaving Meek to get the point in his rear-end), and with Daffy impersonating Jerry Colonna as a fake door-to-door fortune teller. In identical animation as before, Daffy rounds the room again, and comes face to face with the muzzle of Meek’s rifle. Daffy brings the proceedings to a momentary pause, addressing the camera. “No, no! Not twice in the same picture!” Meek blasts away Daffy’s feathers again in a single shot, then tosses him in the roasting pan and into the oven. Meek turns on the gas of the stove to maximum heat. Blood-curdling screams are heard from within the oven, chilling Meek to the bone. He quickly shuts off the gas, and peers in to pull the roasting pan out into view. Daffy casually reclines in the pan, remarking, “Say, now you’re cookin’ with gas”, then zanily begins to baste himself with a ladle, for the iris out.

• “The Wise Quacking Duck” is available in a nice print on Facebook video at THIS LINK.

• A somewhat more blurry transfer though in proper speed and aspect ratio on Dailymotion.

NEXT WEEK: Continuing on with 1943.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

When Bugs Bunny whistled at Elmer’s key in “Fresh Hare”, the first thing I thought of was the Playboy Club keys that members had to show to gain admittance to the clubs when they were new. I don’t know if the keys ever actually opened anything, but they were adorned with the famous Playboy bunny logo, which Bugs might have found well worth whistling at. But of course the Playboy Club wasn’t around in 1942, though if it had been I like to think that Elmer would have been an enthusiastic member, chasing bunnies being something of a hobby with him. Bugs obviously has no idea what any of Elmer’s keys are for and is just wasting time waiting for the bomb to go off. A terrific cartoon, and one of Friz Freleng’s great early Bugs Bunny cartoons. There would be many more to follow.

“Fresh Hare” is one of the few Bugs Bunny cartoons I’ve seen in the German dub. I’m 99% sure Bugs is voiced by a woman.

Too bad Popeye didn’t think to use that trick of pulling in the blank screen to isolate himself from the annoying mouse in “Shuteye Popeye” and finally get some shuteye. But if it didn’t work in “Me Musical Nephews”, it probably wouldn’t have worked there either.

I don’t know how sound the psychology is in “Reason and Emotion”, but the film makes a very good point. I shudder to think what a panic the news junkies of World War II would have been thrown into if social media had been around back then.

Boy, Frank Graham was certainly a very busy voice over talent this year so far! Almost all of the cartoons feature him, including the Walt Disney short film. Great stuff again this week as usual.

In the 1970s, the syndicated version of “Fresh Hare” had the ending chopped off, presumably due to the blackface minstrel gag. So kids of that era must have believed Bugs was executed!

When I was a kid in the 2000s I always saw a cutoff version of Fresh Hare on whatever I had it on. I just thought it ended randomly!

When “Reason and Emotion” aired on a Disney anthology episode “Man is His Own Worst Enemy”, Ludwig von Drake took over as narrator, and references to World War II were taken out.

Something similar happened when an excerpt from the cartoon (the scene inside the woman’s brain) was shown on “The Mouse Factory” with new framing narration recorded by Don Knotts.