We continue today with our latest trail, about cartoons exploring the mysteries of their own medium, characters with a knowledge of their ink and pen origins and screen life, or characters prone to taking up the tools of the artist themselves, often to shape and alter their own world. We pick up from last time in the silent era, then proceed into the dawn of sound.

It is my personal opinion that a large legacy has been lost to animated history due to the failure to maintain the film holdings of Bud Fisher’s “Mutt and Jeff” cartoons. Such a pathetically small portion of the vast number of episodes produced in this series has been passed down to us over the years, most titles seeming to have vanished without a trace. Yet, judging alone from what survives, a surprising trait is noticeable. More gags and tropes which reappear in cartoons of the sound era seem to be recognizable as occurring first within this series than from just about any other series of silent cartoons. Perhaps Paul Terry’s Aesop’s Fables would come close in this regard, but most of the reappearances of material arising from their product were reuses restricted to in-house productions – i.e., gags directly recycled from earlier animation in their own cartoons, but not of a general appeal so as to cross-over into use by rival studios. Mutt and Jeff, however, projected a certain contemporary, modern appeal that seemed to keep them current, and further kept their gags feeling fresh and ripe for reuse. Concepts such as stumbling blindly into death-defying walks on construction girders, fighting anthropomorphic fires, rigging accidents to collect on insurance, and even an accidental shot introducing the idea of defying gravity, to name a few, all seem to trace back to these cartoons. It is highly unlikely that the credit for these concepts can be laid in Bud Fisher’s lap. as he is rumored to have had very little if anything to do with the actual creation of these cartoons, delegating animation tasks to diverse hands over the years. Nevertheless, he seems to have had good luck in hiring competent personnel to keep the series stocked with new plot material Thus, we may always wonder how many more concepts we take for granted from the films of the ‘30’s and onwards that we know so well might have had earlier origins in the numerous installments of this comic duo lost to the sands of time. But I digress.

A fabled instance where Mutt and Jeff apparently become aware of their screen existence is Sound Your ‘A’ (Bud Fisher/Fox, 8/24/19). Unfortunately, despite this film receiving brief mention in Leonard Maltin’s “Of Mice and Magic”, it is doubtful the author ever saw it, as no prints seem to have turned up, and it is more likely that what little is known of it is from advertisements and trades of the day. Its premise appears to have Jeff take command of the theater orchestra, conducting it in some kind of program from the screen. A novel concept, somewhat harkening back to Winsor McCay’s interactive play with Gertie the Dinosaur.

A fabled instance where Mutt and Jeff apparently become aware of their screen existence is Sound Your ‘A’ (Bud Fisher/Fox, 8/24/19). Unfortunately, despite this film receiving brief mention in Leonard Maltin’s “Of Mice and Magic”, it is doubtful the author ever saw it, as no prints seem to have turned up, and it is more likely that what little is known of it is from advertisements and trades of the day. Its premise appears to have Jeff take command of the theater orchestra, conducting it in some kind of program from the screen. A novel concept, somewhat harkening back to Winsor McCay’s interactive play with Gertie the Dinosaur.

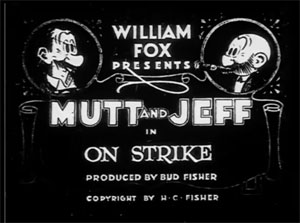

Mutt and Jeff on Strike (Bud Fisher/Fox, 1/20). despite some nitrate deterioration in middle scenes of the reel, is fortunately one of the survivors. It is another groundbreaker, taking to the next level the occasional instance where Koko the Clown might use a pen or ink stamp to clone himself for revenge on Max. Koko, however, never used his own creative talents to go into competition with his own boss. Mutt and Jeff take exactly this bold step in this episode. The trouble begins in a projection booth, when a projectionist comments to an assistant that he is about to screen a reel on comic strip creator Bud Fisher. It conveniently so happens that the miniature Mutt and Jeff, who apparently reside on the frames of celluloid inside a film can, overhear the conversation, and escape from their can to creep into the back row of the theater and peer over the top of the cushioned seats to watch the short. Fisher himself appears in some brief live-action footage, inside a classy estate home, living a life of luxury. Mutt comments to Jeff, “Why should we work our heads off for that guy?” The two proceed to a phone booth in the theater lobby, and dial up Fisher. Mutt states his demands: 75% of the profits, a three hour work day, and five days a week. The answer is a shouting “NO!” An impasse reached, the duo declare a strike.

Mutt tells Jeff they can do without Fisher – by taking on the task of animating themselves. Jeff insists they can’t do it, as they have neither studio, camera, supplies or equipment. In a pen-and-ink world, Mutt supplies the solution by reaching in his pocket and uncapping a trusty fountain pen. With deft hand, he proceeds to draw an animation desk and stool on the blank screen background, a supply of drawing paper, and a bottle of artist’s ink. He casually tosses the ink bottle over his shoulder to Jeff, while engaged in drawing for himself an animation camera. The stopper falls out of the bottle, and Jeff is instantly covered from head to toe in black ink. Mutt, still in a take-charge mood, draws a new bottle, of ink remover. He pours out the contents on Jeff, and the ink coating disappears. But so does Jeff, being made of the stuff himself! Mutt reacts with shock, then nervously fidgets at the thought of what to do without his needed partner. Producing his pen again, Mutt boldly takes on redrawing his old friend back into existence. Mutt once again proves himself a competent artist, accurately re-creating Jeff – except for forgetting to draw in his right leg. Jeff stumbles, wails loudly, and attempts to balance like a stork. Mutt laughs heartily at his own mistake, but Jeff doesn’t think it so funny, and socks Mutt on the nose. Mutt gets serious, and completes drawing in Jeff’s missing limb, which Jeff carefully tests by wiggling his toes before tenuously putting his full weight upon it. Jeff shakes Mutt’s hand, renewing their friendship, then settles down to business churning out drawings at the animation desk. Jeff’s working is depicted with reasonable real-life accuracy, placing respective drawings upon registration pins, and flipping them to observe if motion is being achieved properly. By now, Mutt has finished drawing his animation camera, and Jeff flings each new drawing across the room so Mutt can photograph it. Jeff asks how many drawings are needed to complete a reel, and Mutt estimates about 3,000. (An interesting comparison with the frame rate of Winsor McCay’s “Nemo” film, which allegedly took 4,000 drawings just to present about two minutes of image – demonstrating the reduction in quality that production-line animation had already taken.) Jeff is still flabbergasted at this statistic.

Mutt tells Jeff they can do without Fisher – by taking on the task of animating themselves. Jeff insists they can’t do it, as they have neither studio, camera, supplies or equipment. In a pen-and-ink world, Mutt supplies the solution by reaching in his pocket and uncapping a trusty fountain pen. With deft hand, he proceeds to draw an animation desk and stool on the blank screen background, a supply of drawing paper, and a bottle of artist’s ink. He casually tosses the ink bottle over his shoulder to Jeff, while engaged in drawing for himself an animation camera. The stopper falls out of the bottle, and Jeff is instantly covered from head to toe in black ink. Mutt, still in a take-charge mood, draws a new bottle, of ink remover. He pours out the contents on Jeff, and the ink coating disappears. But so does Jeff, being made of the stuff himself! Mutt reacts with shock, then nervously fidgets at the thought of what to do without his needed partner. Producing his pen again, Mutt boldly takes on redrawing his old friend back into existence. Mutt once again proves himself a competent artist, accurately re-creating Jeff – except for forgetting to draw in his right leg. Jeff stumbles, wails loudly, and attempts to balance like a stork. Mutt laughs heartily at his own mistake, but Jeff doesn’t think it so funny, and socks Mutt on the nose. Mutt gets serious, and completes drawing in Jeff’s missing limb, which Jeff carefully tests by wiggling his toes before tenuously putting his full weight upon it. Jeff shakes Mutt’s hand, renewing their friendship, then settles down to business churning out drawings at the animation desk. Jeff’s working is depicted with reasonable real-life accuracy, placing respective drawings upon registration pins, and flipping them to observe if motion is being achieved properly. By now, Mutt has finished drawing his animation camera, and Jeff flings each new drawing across the room so Mutt can photograph it. Jeff asks how many drawings are needed to complete a reel, and Mutt estimates about 3,000. (An interesting comparison with the frame rate of Winsor McCay’s “Nemo” film, which allegedly took 4,000 drawings just to present about two minutes of image – demonstrating the reduction in quality that production-line animation had already taken.) Jeff is still flabbergasted at this statistic.

The duo’s first reel debuts – an epic entitled A Thrilling Rescue. (No details are provided as to how M&J found a distributor, as the credits for the reel give no indication that it is issued under their old Fox contract.) The reel is perhaps the first of its kind in animation history – giving the real-life animators the chance to have some fun, presenting their characters deliberately badly-drawn! In modern hindsight, watching the film today, one is instantly reminded of subsequent sound films like “Making ‘Em Move”, “Porky’s Preview”, and “Cartoons Ain’t Human”, all of which will be subsequently discussed, for which this film was the obvious prototype. In the duo’s self-drawn masterpiece, Jeff meets a milkmaid with springy oversized curls, and instantly asks her to be his wife. She responds that she is engaged to another, causing Jeff and the cow to cry oversized teardrops across the shot (a water effect which may have been remembered by Tex Avery in producing equally oversized raindrops for the “September In the Rain” number of “Porky’s Preview”). Mutt hobbles in in a stilted walk cycle, and is embraced by the girl, while Jeff faints, becoming unusually 2-D flat as he collapses to the ground. Mutt points to the sky, stating that there is a beautiful moon out tonight – but the sky is empty. Forgetful Jeff the animator has forgotten to draw it in, and it suddenly appears from nowhere over Mutt’s finger, and for good measure bites Mutt’s outstretched digit. Suddenly, the milkmaid is abducted by an Indian Chief, who carries her away on horseback. “My kingdom for a horse”, shouts Mutt. With the same suddenness as the moon’s appearance, a horse appears in the very next frame under Mutt, plus a horsewhip in Mutt’s hand. Mutt gives the nag a few whacks, and the horse starts up – but awkwardly, in rocking-horse fashion, for its first few seconds.

The duo’s first reel debuts – an epic entitled A Thrilling Rescue. (No details are provided as to how M&J found a distributor, as the credits for the reel give no indication that it is issued under their old Fox contract.) The reel is perhaps the first of its kind in animation history – giving the real-life animators the chance to have some fun, presenting their characters deliberately badly-drawn! In modern hindsight, watching the film today, one is instantly reminded of subsequent sound films like “Making ‘Em Move”, “Porky’s Preview”, and “Cartoons Ain’t Human”, all of which will be subsequently discussed, for which this film was the obvious prototype. In the duo’s self-drawn masterpiece, Jeff meets a milkmaid with springy oversized curls, and instantly asks her to be his wife. She responds that she is engaged to another, causing Jeff and the cow to cry oversized teardrops across the shot (a water effect which may have been remembered by Tex Avery in producing equally oversized raindrops for the “September In the Rain” number of “Porky’s Preview”). Mutt hobbles in in a stilted walk cycle, and is embraced by the girl, while Jeff faints, becoming unusually 2-D flat as he collapses to the ground. Mutt points to the sky, stating that there is a beautiful moon out tonight – but the sky is empty. Forgetful Jeff the animator has forgotten to draw it in, and it suddenly appears from nowhere over Mutt’s finger, and for good measure bites Mutt’s outstretched digit. Suddenly, the milkmaid is abducted by an Indian Chief, who carries her away on horseback. “My kingdom for a horse”, shouts Mutt. With the same suddenness as the moon’s appearance, a horse appears in the very next frame under Mutt, plus a horsewhip in Mutt’s hand. Mutt gives the nag a few whacks, and the horse starts up – but awkwardly, in rocking-horse fashion, for its first few seconds.

Jeff revives, and sniffs the ground to follow Mutt’s trail. We suddenly cut to the results of the chase, which haven’t turned out well for Mutt. He is tied to a stake, with the Chief menacing him with a drawn dagger. Jeff appears behind the Chief, armed with a pistol, and fires a shot. Inexplicably, the bullet travels three-quarters of the way to the Chief, then stops in mid-air. Nevertheless, the Chief falls like he’s been hit, with the bullet still stranded in air on its last cel. (Maybe Jeff hasn’t figured out how to draw special effects to animate the bullet’s impact.) “My hero”, declares the girl, as Jeff receives a kiss, while Mutt is left tied up. (Mutt’s real mistake here was putting Jeff in charge of animation. Considering his own realistic penmanship in providing a studio and restoring Jeff from his fountain pen, perhaps the film would have turned out better if the two had exchanged their respective production roles.) The theater audience, to say the least, is dissatisfied, as the miniature Mutt and Jeff, again observing from behind the seats in the back row, hear shouts of “Punk!” “The worst I ever saw.” M&J abruptly leave, and suddenly appear at the door of the office of their old boss. Mutt sends Jeff in, with instructions to tell Fisher thar if he’ll take them back, they’ll work for nothing. The results are favorable, as Jeff re-emerges in something of a swoon, informing Mutt that Fisher was so happy to have them back, he kissed Jeff.

Jeff revives, and sniffs the ground to follow Mutt’s trail. We suddenly cut to the results of the chase, which haven’t turned out well for Mutt. He is tied to a stake, with the Chief menacing him with a drawn dagger. Jeff appears behind the Chief, armed with a pistol, and fires a shot. Inexplicably, the bullet travels three-quarters of the way to the Chief, then stops in mid-air. Nevertheless, the Chief falls like he’s been hit, with the bullet still stranded in air on its last cel. (Maybe Jeff hasn’t figured out how to draw special effects to animate the bullet’s impact.) “My hero”, declares the girl, as Jeff receives a kiss, while Mutt is left tied up. (Mutt’s real mistake here was putting Jeff in charge of animation. Considering his own realistic penmanship in providing a studio and restoring Jeff from his fountain pen, perhaps the film would have turned out better if the two had exchanged their respective production roles.) The theater audience, to say the least, is dissatisfied, as the miniature Mutt and Jeff, again observing from behind the seats in the back row, hear shouts of “Punk!” “The worst I ever saw.” M&J abruptly leave, and suddenly appear at the door of the office of their old boss. Mutt sends Jeff in, with instructions to tell Fisher thar if he’ll take them back, they’ll work for nothing. The results are favorable, as Jeff re-emerges in something of a swoon, informing Mutt that Fisher was so happy to have them back, he kissed Jeff.

Another presumably lost Mutt and Jeff title, A Fisherless Cartoon (1918), potentially siffest variations on the same theme. But we may never know.

Max Fleischer’s Song Cartunes, later renamed Screen Songs, had an obvious awareness of an audience, but began with multiple instances of use of stock footage of Koko drawing an orchestra, then joining it at a theater, where he would hold up a sign asking the audience to join in the song of the day. For Koko, being aware of cartoon life was of course nothing new by this time. However, a certain breakthrough seems to have occurred with the early sound release. My Old Kentucky Home (Fleischer/Red Seal, 6/26) in which a little dog breaks the fourth wall by actually speaking directly to the audience. The dog may have been intended as something of a mascot for Fleischer’s early sound releases, as he also appears in “Pack Up Your Troubles” from the same year, in which his bark is heard over the titles – and the track for “Kentucky Home”, on which opening titles have been removed in present prints, includes the same barking. The dog arrives home (presumably after a hard day’s work), and removes a derby hat and coat. Instead of hanging the hat on a nearby lion’s head statue, the dog pumps the tail of the statue to fill the inverted hat with a flow of water from the lion’s mouth, then washes his face with the water, drying off with his own coat as a towel. Using a musical gag of the Jewish cue, “Mahzel Tov”, the dog removes from a box a large juicy ham. With a large knife, he carefully slices meat away from center bone – but throws the meat carelessly away, seeking only the large hambone within for his supper. The dog removes from his jaws a set of false teeth, stopping to notice that one fake tooth has fallen out. With a hammer, he pounds the loose tooth back in, with a sound gag roughly synchronizing the hammer blows to the “Anvil Chorus”. The dog produces a grinding stone, and polishes the false teeth to sharpened perfection. With the dentures re-installed, the dog bites off and consumes one end of the hambone. Then, for no particular reason, he miraculously stretches the “bone” into a slide trombone. After playing a few bars of the title tune on the instrument, the dog removes the bell of the horn, and compresses it with his hands into a ball. “Follow the ball, and join in, everybody”, speaks the dog to the camera in relatively bad synchronization. The rest is the usual bouncing ball lyric, and transformation of printed lyrics into objects in the closing stanzas.

Max Fleischer’s Song Cartunes, later renamed Screen Songs, had an obvious awareness of an audience, but began with multiple instances of use of stock footage of Koko drawing an orchestra, then joining it at a theater, where he would hold up a sign asking the audience to join in the song of the day. For Koko, being aware of cartoon life was of course nothing new by this time. However, a certain breakthrough seems to have occurred with the early sound release. My Old Kentucky Home (Fleischer/Red Seal, 6/26) in which a little dog breaks the fourth wall by actually speaking directly to the audience. The dog may have been intended as something of a mascot for Fleischer’s early sound releases, as he also appears in “Pack Up Your Troubles” from the same year, in which his bark is heard over the titles – and the track for “Kentucky Home”, on which opening titles have been removed in present prints, includes the same barking. The dog arrives home (presumably after a hard day’s work), and removes a derby hat and coat. Instead of hanging the hat on a nearby lion’s head statue, the dog pumps the tail of the statue to fill the inverted hat with a flow of water from the lion’s mouth, then washes his face with the water, drying off with his own coat as a towel. Using a musical gag of the Jewish cue, “Mahzel Tov”, the dog removes from a box a large juicy ham. With a large knife, he carefully slices meat away from center bone – but throws the meat carelessly away, seeking only the large hambone within for his supper. The dog removes from his jaws a set of false teeth, stopping to notice that one fake tooth has fallen out. With a hammer, he pounds the loose tooth back in, with a sound gag roughly synchronizing the hammer blows to the “Anvil Chorus”. The dog produces a grinding stone, and polishes the false teeth to sharpened perfection. With the dentures re-installed, the dog bites off and consumes one end of the hambone. Then, for no particular reason, he miraculously stretches the “bone” into a slide trombone. After playing a few bars of the title tune on the instrument, the dog removes the bell of the horn, and compresses it with his hands into a ball. “Follow the ball, and join in, everybody”, speaks the dog to the camera in relatively bad synchronization. The rest is the usual bouncing ball lyric, and transformation of printed lyrics into objects in the closing stanzas.

Felix the Cat, though not necessarily aware in the majority of his episodes that he is a cartoon, was certainly among the first major characters to engage in a regular habit of “breaking the fourth wall”, definitely aware that there is an audience out there in the darkness watching him. He exchanges aside looks with us, shrugs his shoulders to us when he becomes frustrated and can’t come up with an idea, and communicates a regular banter of comic-strip balloon dialogue with us that differs from most characters of the day, as it is not merely seen when he is talking to a character on screen, but in lines delivered when no one else is around, specifically confiding his thought processes with us. This speaking trait was on rare occasions employed by Koko the Clown at Fleischer’s, but more often than not, Koko’s dialogue was focused on his boss Max, Fitz, or others, making it more traditionally conversational. Felix’s was on a personal level, as if we were his confidants and trusted friends, to which he could reveal his most pressing needs and most devilish plans. While such manner of delivering lines had become conventional by the 1940’s, its ever-present use at this early stage of filmmaking probably was a strong factor in contributing to the character’s audience appeal, allowing Felix to climb to top spot in popularity of silent animated characters. It is a sad loss that so many of Felix’s films have been retrofitted for sound, splicing away Felix’s personal remarks to the public, and thus removing a good deal of their charm, as well as reducing general understandability of the storylines.

Felix the Cat, though not necessarily aware in the majority of his episodes that he is a cartoon, was certainly among the first major characters to engage in a regular habit of “breaking the fourth wall”, definitely aware that there is an audience out there in the darkness watching him. He exchanges aside looks with us, shrugs his shoulders to us when he becomes frustrated and can’t come up with an idea, and communicates a regular banter of comic-strip balloon dialogue with us that differs from most characters of the day, as it is not merely seen when he is talking to a character on screen, but in lines delivered when no one else is around, specifically confiding his thought processes with us. This speaking trait was on rare occasions employed by Koko the Clown at Fleischer’s, but more often than not, Koko’s dialogue was focused on his boss Max, Fitz, or others, making it more traditionally conversational. Felix’s was on a personal level, as if we were his confidants and trusted friends, to which he could reveal his most pressing needs and most devilish plans. While such manner of delivering lines had become conventional by the 1940’s, its ever-present use at this early stage of filmmaking probably was a strong factor in contributing to the character’s audience appeal, allowing Felix to climb to top spot in popularity of silent animated characters. It is a sad loss that so many of Felix’s films have been retrofitted for sound, splicing away Felix’s personal remarks to the public, and thus removing a good deal of their charm, as well as reducing general understandability of the storylines.

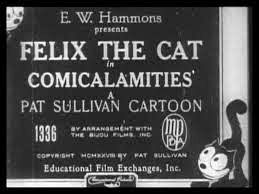

On one occasion, however, Felix became even more keenly aware of his screen existence, acknowledging the presence of a “higher source” who oversees his world and from whom to seek assistance. Comicalamities (Pat Sullivan/Educational, 4/1/28) opens in Max Fleischer style, with the hand of an animator (a still photograph moved around the screen) drawing in Felix on a black background with a pen. Felix denotes dissatisfaction when he is fully able to move, pointing out that the artist has left off his tail. The pen returns to draw in the missing appendage. Felix then becomes aware that he is only in outline form, and yells to the animator, “You forgot to blacken me in.” But the animator does not respond, having disappeared somewhere. (Is it lunch break?) Felix puzzles what to do, then hits on a solution, walking out of the blank frame into an adjoining background of a shoe-shiner’s stand. For a nickel, Felix receives a full coating of shoe polish, and some vigorous polishing of his paws and tail. Problem solved. As Felix proceeds on his way, he believes he feels the first signs of downpouring rain, and grabs a small fir tree from the ground, opening its limbs above him as an umbrella. But the rain is not from the skies, but from the weeping eyes of a female cat sitting on a nearby park bench. Being chivalrous with those of the opposite sex, Felix inquires what is wrong. A few intertitles appear to be missing from current prints, as the girl hands Felix some kind of printed flyer, which we can only guess must advertise a talent search or beauty contest. Felix points to the flyer, then to the girl, as if to say, “You?” The girl for the first time reveals her face, and Felix reacts in taken-aback shock, instantly realizing there is a problem. The girl is as homely as a mud fence. Lunch break must be over for the animator, as Felix responds to the girl’s imploring remark, “Oh, if I were only beautiful”, by calling for the animator’s eraser. Using it, he blanks out the girl’s face, then borrows the animator’s pen to draw in a pair of pretty eyes and lipsticked lips, with some light cat whiskers on the sides.

On one occasion, however, Felix became even more keenly aware of his screen existence, acknowledging the presence of a “higher source” who oversees his world and from whom to seek assistance. Comicalamities (Pat Sullivan/Educational, 4/1/28) opens in Max Fleischer style, with the hand of an animator (a still photograph moved around the screen) drawing in Felix on a black background with a pen. Felix denotes dissatisfaction when he is fully able to move, pointing out that the artist has left off his tail. The pen returns to draw in the missing appendage. Felix then becomes aware that he is only in outline form, and yells to the animator, “You forgot to blacken me in.” But the animator does not respond, having disappeared somewhere. (Is it lunch break?) Felix puzzles what to do, then hits on a solution, walking out of the blank frame into an adjoining background of a shoe-shiner’s stand. For a nickel, Felix receives a full coating of shoe polish, and some vigorous polishing of his paws and tail. Problem solved. As Felix proceeds on his way, he believes he feels the first signs of downpouring rain, and grabs a small fir tree from the ground, opening its limbs above him as an umbrella. But the rain is not from the skies, but from the weeping eyes of a female cat sitting on a nearby park bench. Being chivalrous with those of the opposite sex, Felix inquires what is wrong. A few intertitles appear to be missing from current prints, as the girl hands Felix some kind of printed flyer, which we can only guess must advertise a talent search or beauty contest. Felix points to the flyer, then to the girl, as if to say, “You?” The girl for the first time reveals her face, and Felix reacts in taken-aback shock, instantly realizing there is a problem. The girl is as homely as a mud fence. Lunch break must be over for the animator, as Felix responds to the girl’s imploring remark, “Oh, if I were only beautiful”, by calling for the animator’s eraser. Using it, he blanks out the girl’s face, then borrows the animator’s pen to draw in a pair of pretty eyes and lipsticked lips, with some light cat whiskers on the sides.

The girl tries out her new optics with a few blinks, and is pleased – but still has an inquiry. In another missing intertitle, she appears to call for something suitable to wear. Felix provides same, by plucking from the ground an oversized morning glory bell, inverting it, and placing it down over the girl’s head as a new dress. In another missing subtitle, the girl’s desires begin to get more demanding, suggesting a pearl necklace to improve her ensemble. Felix remains the gallant, trotting over to the local jewelry store, but jumps backwards when he sees the prices – nothing under $500. He shuns the store’s merchandise, and proceeds to a bluff overlooking the ocean. “That’s where they grow – down there”, Felix remarks to the offscreen animator. The animator’s fountain pen appears above the water, and the hand triggers the pen to shoot a thin trail of ink out and into the water. Felix leaps onto the line formed by the falling ink, and clings to it, descending into the ocean depths. There, Felix fins a row of oyster “beds” in which small oysters rest, sleeping upon plush pillows. Felix picks them up one by one, tickling them under the chin of their shells until they open their mouth in laughter. Two shells turn up empty, but the third wears a pearl necklace inside as it it were the oyster’s upper bridgework. Felix plucks out the wanted jewelry, casting the oyster aside. The creature begins wailing for its mother – an oversized oyster rocking cradles, named “Mother of Pearl”. She begins angrily pursuing Felix through the water. Felix ducks into a sponge hole, but emerges again in a hurry, pursued by a serpent. More weird creatures join in the chase, until Felix finds monsters in pursuit from both the front and the back. “Hide me! Save me!”, Felix implores to the offscreen animator. The shot changes to view above the water surface, as the animator pours a whole bottle of ink into the ocean. The ink seeps down into the water, and, like the ink of an octopus, gradually darkens the scene to black, with only Felix’s eyes showing. This gives Felix his chance to escape to the surface, wiping the excess ink away from his face, and returning to the girl, necklace in hand.

The girl tries out her new optics with a few blinks, and is pleased – but still has an inquiry. In another missing intertitle, she appears to call for something suitable to wear. Felix provides same, by plucking from the ground an oversized morning glory bell, inverting it, and placing it down over the girl’s head as a new dress. In another missing subtitle, the girl’s desires begin to get more demanding, suggesting a pearl necklace to improve her ensemble. Felix remains the gallant, trotting over to the local jewelry store, but jumps backwards when he sees the prices – nothing under $500. He shuns the store’s merchandise, and proceeds to a bluff overlooking the ocean. “That’s where they grow – down there”, Felix remarks to the offscreen animator. The animator’s fountain pen appears above the water, and the hand triggers the pen to shoot a thin trail of ink out and into the water. Felix leaps onto the line formed by the falling ink, and clings to it, descending into the ocean depths. There, Felix fins a row of oyster “beds” in which small oysters rest, sleeping upon plush pillows. Felix picks them up one by one, tickling them under the chin of their shells until they open their mouth in laughter. Two shells turn up empty, but the third wears a pearl necklace inside as it it were the oyster’s upper bridgework. Felix plucks out the wanted jewelry, casting the oyster aside. The creature begins wailing for its mother – an oversized oyster rocking cradles, named “Mother of Pearl”. She begins angrily pursuing Felix through the water. Felix ducks into a sponge hole, but emerges again in a hurry, pursued by a serpent. More weird creatures join in the chase, until Felix finds monsters in pursuit from both the front and the back. “Hide me! Save me!”, Felix implores to the offscreen animator. The shot changes to view above the water surface, as the animator pours a whole bottle of ink into the ocean. The ink seeps down into the water, and, like the ink of an octopus, gradually darkens the scene to black, with only Felix’s eyes showing. This gives Felix his chance to escape to the surface, wiping the excess ink away from his face, and returning to the girl, necklace in hand.

But the girl’s demands aren’t finished. Now she suggests that such beautiful pearls can’t be done justice without a fur coat. Felix is startled by this new request, but swallows his pride, and continues to do the girl’s bidding. Of course, there’s no point in visiting a furrier. Instead, Felix goes to the pole, a destination declared by an intertitle as “Fur, fur away.” Felix battles with a large bear over his coat, but is socked for a loop, landing seemingly unconscious on his back. The animator appears to have little faith in Felix’s quest, as he signals the closing of an iris out. However, the hands of Felix rise just before the circle closes, pushing it open again, allowing him to complain to the animator: “Hold it! This picture isn’t finished by a long shot!” Pushing the circle back out of frame, Felix again requests the animator’s assistance. This time, the animator doesn’t even resort to his drawing tools. Instead, his hand reaches down over the bear, picking him up by the scruff of the neck. A button gives way, and the fur comes right off the bear’s back, already fashioned as a coat. Felix receives the prize from the animator, waves thanks, and proceeds on his way home. The scene returns to the girl cat, as Felix places the stylish wrap upon her shoulders. Then Felix finally puckers up, expecting to receive a kiss. To his dismay, the girl reacts in haughty fashion. “You dare to make love to me? Me, a MOVIE STAR!” This us all Felix can stand. Felix remarks to both audience and animator, “Oh, well, she’s only a paper lover.” Felix extends his paws, clutching at the paper background on which he and the girl exist, and tears a large oval of paper out of the sheet, removing with it the entire image of the girl from the screen. Felix crumples the paper wad into a ball, then tosses it out of the frame with disdain and relief. As a final touch, without an intertitle, Felix again calls to the animator, and visibly mouths the words “Hey, you…”, gesturing with his hands as if mimicking the closing of an iris out. The camera performs just such a closing, this time shutting entirely for the The End card.

But the girl’s demands aren’t finished. Now she suggests that such beautiful pearls can’t be done justice without a fur coat. Felix is startled by this new request, but swallows his pride, and continues to do the girl’s bidding. Of course, there’s no point in visiting a furrier. Instead, Felix goes to the pole, a destination declared by an intertitle as “Fur, fur away.” Felix battles with a large bear over his coat, but is socked for a loop, landing seemingly unconscious on his back. The animator appears to have little faith in Felix’s quest, as he signals the closing of an iris out. However, the hands of Felix rise just before the circle closes, pushing it open again, allowing him to complain to the animator: “Hold it! This picture isn’t finished by a long shot!” Pushing the circle back out of frame, Felix again requests the animator’s assistance. This time, the animator doesn’t even resort to his drawing tools. Instead, his hand reaches down over the bear, picking him up by the scruff of the neck. A button gives way, and the fur comes right off the bear’s back, already fashioned as a coat. Felix receives the prize from the animator, waves thanks, and proceeds on his way home. The scene returns to the girl cat, as Felix places the stylish wrap upon her shoulders. Then Felix finally puckers up, expecting to receive a kiss. To his dismay, the girl reacts in haughty fashion. “You dare to make love to me? Me, a MOVIE STAR!” This us all Felix can stand. Felix remarks to both audience and animator, “Oh, well, she’s only a paper lover.” Felix extends his paws, clutching at the paper background on which he and the girl exist, and tears a large oval of paper out of the sheet, removing with it the entire image of the girl from the screen. Felix crumples the paper wad into a ball, then tosses it out of the frame with disdain and relief. As a final touch, without an intertitle, Felix again calls to the animator, and visibly mouths the words “Hey, you…”, gesturing with his hands as if mimicking the closing of an iris out. The camera performs just such a closing, this time shutting entirely for the The End card.

Bosko the Talk-Ink Kid (5/29/29), like “Alice’s Wonderland”, was never seen by the theater public, but only by exhibitors who were solicited by Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising for distribution of a new series. The winning bid went to Warner Brothers. It is unknown what kind of sound system H&I used for this pilot, as the results are exceptionally noisy, with a ton of background hum. (Some reissues of the film attempt to fill with silent gaps between dialogue lines, but the difference in ambience with the recorded scenes still makes it jarring.)

Rudolf Ising appears on screen at a drawing easel. He seems to be searching for a new idea, dissatisfied with his first drawing and crumpling it up into the wastebasket. He then creates a drawing of Bosko before our eyes. The drawing comes to life, and begins to speak to him (in a voice more heavily-laden with stereotypical black Southern accent than usual). “Well, here I is, and I sure feel good”, the character states. Ising asks why, and Bosko replies, “I is just out of the pen” (play on slang for “penitentiary”). The character introduces himself by name, and when asked what he can do, responds, “Boss, what I can’t do, ain’t.” Bosko engages in humming, whistling, and tap dancing, then suddenly becomes aware of other eyes upon him. “Who’s all them folks out there in the dark?”, Bosko asks Ising. “Why, the audience, Bosko. Can you make ‘em laugh?”. responds Rudy. Bosko scratches his head in thought, then asks if Rudy has a piano. Rudy draws one in. Bosko tests the keyboard, finding a base note out of place among the treble keys. Bosko merely plucks the key out of the board, replanting it in a lower position in proper sequence. He then begins a rendition of Al Jolson’s “Sonny Boy, holding the “Boy” note for an incredibly long time on bended knee, until his head vibrates loose from his body, springing to the top of the screen on a neck spring like the head of a jack in the box. “Where’s I at?”. asks Bosko, and attempts with his arms to push his head back to his collar line, only to have ir spring upwards to full extension once again. The only quick fix is for Bosko to twirl his piano stool, allowing his body to rise to the level of his head, and his neck to re-attach. Bosko then resumes his song, causing Ising to plug his ears, and remark, “Rotten!” Ising produces his fountain pen, and sucks Bosko and the piano back inside its barrel where they belong, then ejects the ink into the inkwell, inserting a stopper just as did Fleischer. However, Bosko pops the stopper long enough to tell the audience, “Well, so long folks. I’ll be seeing you.” “That’s all, folks” had not yet been coined. (Front and end titles below were created decades later by Mark Kausler).

Rudolf Ising appears on screen at a drawing easel. He seems to be searching for a new idea, dissatisfied with his first drawing and crumpling it up into the wastebasket. He then creates a drawing of Bosko before our eyes. The drawing comes to life, and begins to speak to him (in a voice more heavily-laden with stereotypical black Southern accent than usual). “Well, here I is, and I sure feel good”, the character states. Ising asks why, and Bosko replies, “I is just out of the pen” (play on slang for “penitentiary”). The character introduces himself by name, and when asked what he can do, responds, “Boss, what I can’t do, ain’t.” Bosko engages in humming, whistling, and tap dancing, then suddenly becomes aware of other eyes upon him. “Who’s all them folks out there in the dark?”, Bosko asks Ising. “Why, the audience, Bosko. Can you make ‘em laugh?”. responds Rudy. Bosko scratches his head in thought, then asks if Rudy has a piano. Rudy draws one in. Bosko tests the keyboard, finding a base note out of place among the treble keys. Bosko merely plucks the key out of the board, replanting it in a lower position in proper sequence. He then begins a rendition of Al Jolson’s “Sonny Boy, holding the “Boy” note for an incredibly long time on bended knee, until his head vibrates loose from his body, springing to the top of the screen on a neck spring like the head of a jack in the box. “Where’s I at?”. asks Bosko, and attempts with his arms to push his head back to his collar line, only to have ir spring upwards to full extension once again. The only quick fix is for Bosko to twirl his piano stool, allowing his body to rise to the level of his head, and his neck to re-attach. Bosko then resumes his song, causing Ising to plug his ears, and remark, “Rotten!” Ising produces his fountain pen, and sucks Bosko and the piano back inside its barrel where they belong, then ejects the ink into the inkwell, inserting a stopper just as did Fleischer. However, Bosko pops the stopper long enough to tell the audience, “Well, so long folks. I’ll be seeing you.” “That’s all, folks” had not yet been coined. (Front and end titles below were created decades later by Mark Kausler).

Showing Off (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Scrappy, 11/11/31 – Dick Huemer, dir.), is an early entry in Mintz’s Our Gang-style little boy series, providing an alternate to his long-running Krazy Kat cartoons. Today, we find Margie (in her screen debut) engaging in some embroidery on her front porch. Scrappy sits on a curb on the other side of the street, admiring her. A love heart emerges in air from his chest, out of which appears Dan Cupid, who first makes a direct hit upon him with an arrow, then peppers him with love bullets from a machine gun, causing Scrappy to be totally smitten. “Yoo Hoo”, calks Scrappy to the girl. “Go away, little boy”, responds Margie, turning up her nose at him (with a push upon it by her finger). At the words, “little boy”, Scrappy shrinks, until he is lower than the curb edge. Eventually, he regains his normal height, disgusted at being insulted. But a billboard ad of a tough-looking cowboy provides a possible answer. “Be a man – smoke El Ranko Cigars.” Not being able to afford the real thing, Scrappy pinches a head of lettuce from a local vegetable stand, proceeds to a trash can, and rolls the lettuce inside a sheet of discarded newspaper, providing a reasonable visual facsimele. He realizes he has no matches, but takes advantage of a passing drunkard emerging from a drinking spree, igniting the fake cigar with the glow from the drunkard’s flushed-red nose. Scrappy spends the next three minutes showing off his smoking style, largely to the bored yawns of Margie. He flips the cigar into the air with a twist, causing it to skywrite the words “Oh you kid!” in smoke, and even dot the exclamation point. He engages in a tap-dancing impersonation of then-current stage star Joe Frisco, who used his cigar for a dancing prop. Scrappy then jerks his head backwards, sending the cigar into the air again, with intent to catch it in his mouth on the way down. The cigar, however, flips end over end, landing in Scrappy’s mouth with flame-end down, and is swallowed into Scrappy’s gullet. Scrappy doubles up in stomach pain, and spits fire, calling for help with each exhale of flame. Margie ventures too close, and is burned by the flames igniting on the ground around Scrappy, one shot of flame setting on fire her lace panties. Another shot of flame finally forms into the shape of a foot, giving Scrappy a kick in the pants, and ejecting the cigar from his stomach. Margie, however, is still running around in circles with her pants on fire. Scrappy finally proves he is aware he is a screen creation, performing in one of its earliest uses a trope that would become a regular part of the repertoire of both Warner Brothers and MGM, primarily through the influence of Tex Avery. He turns to the theater audience, and implores, “Is there a fireman in the house?” After a brief pause to let him through, a fireman does jump onto the screen, aims a hose at Margie, and puts out the flame with a short, quick spurt of water, for an abrupt fade out.

Showing Off (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Scrappy, 11/11/31 – Dick Huemer, dir.), is an early entry in Mintz’s Our Gang-style little boy series, providing an alternate to his long-running Krazy Kat cartoons. Today, we find Margie (in her screen debut) engaging in some embroidery on her front porch. Scrappy sits on a curb on the other side of the street, admiring her. A love heart emerges in air from his chest, out of which appears Dan Cupid, who first makes a direct hit upon him with an arrow, then peppers him with love bullets from a machine gun, causing Scrappy to be totally smitten. “Yoo Hoo”, calks Scrappy to the girl. “Go away, little boy”, responds Margie, turning up her nose at him (with a push upon it by her finger). At the words, “little boy”, Scrappy shrinks, until he is lower than the curb edge. Eventually, he regains his normal height, disgusted at being insulted. But a billboard ad of a tough-looking cowboy provides a possible answer. “Be a man – smoke El Ranko Cigars.” Not being able to afford the real thing, Scrappy pinches a head of lettuce from a local vegetable stand, proceeds to a trash can, and rolls the lettuce inside a sheet of discarded newspaper, providing a reasonable visual facsimele. He realizes he has no matches, but takes advantage of a passing drunkard emerging from a drinking spree, igniting the fake cigar with the glow from the drunkard’s flushed-red nose. Scrappy spends the next three minutes showing off his smoking style, largely to the bored yawns of Margie. He flips the cigar into the air with a twist, causing it to skywrite the words “Oh you kid!” in smoke, and even dot the exclamation point. He engages in a tap-dancing impersonation of then-current stage star Joe Frisco, who used his cigar for a dancing prop. Scrappy then jerks his head backwards, sending the cigar into the air again, with intent to catch it in his mouth on the way down. The cigar, however, flips end over end, landing in Scrappy’s mouth with flame-end down, and is swallowed into Scrappy’s gullet. Scrappy doubles up in stomach pain, and spits fire, calling for help with each exhale of flame. Margie ventures too close, and is burned by the flames igniting on the ground around Scrappy, one shot of flame setting on fire her lace panties. Another shot of flame finally forms into the shape of a foot, giving Scrappy a kick in the pants, and ejecting the cigar from his stomach. Margie, however, is still running around in circles with her pants on fire. Scrappy finally proves he is aware he is a screen creation, performing in one of its earliest uses a trope that would become a regular part of the repertoire of both Warner Brothers and MGM, primarily through the influence of Tex Avery. He turns to the theater audience, and implores, “Is there a fireman in the house?” After a brief pause to let him through, a fireman does jump onto the screen, aims a hose at Margie, and puts out the flame with a short, quick spurt of water, for an abrupt fade out.

Making ‘Em Move (aka “In a Cartoon Studio” – Van Beuren, Pathe, Aesop’s Fables, 7/5/31 – John Foster, Harry Bailey. dir,). For some, this may be one of our earliest recollections of a cartoon attempting to describe the animation process. It begins with a female cat approaching a “Keeper” positioned at the locked door of an animated cartoon studio. “Pardon me. I’ve always wondered how they were made”, she inquires. The guard signals her with a shush to be very quiet, then unlocks the front door. He ushers her through three consecutive corridors, all including signs requesting “Silence”, then opens the final door. A barrage of animation drawing paper emerges in a flood from the doorway. When the paper clears, we see wall-to-wall activity, as animal artists churn out drawings from their drawing boards by the tons, randomly tossing them everywhere, while other stock bots round up the drawings in sky-high piles and carry them away. An orchestra performs hectic mood music in the background for the artists’ inspiration. A gag is used that John Foster must have thought hilarious, as he reused it time and again in both Van Beuren and later Terrytoons productions. Whenever the orchestra reaches a rapid, complicated passage in their music, everyone rolls off their seats, bobbing around like spilled marbles upon the floor, until the music pauses, then everyone slowly rises and eventually regains their seats.

Making ‘Em Move (aka “In a Cartoon Studio” – Van Beuren, Pathe, Aesop’s Fables, 7/5/31 – John Foster, Harry Bailey. dir,). For some, this may be one of our earliest recollections of a cartoon attempting to describe the animation process. It begins with a female cat approaching a “Keeper” positioned at the locked door of an animated cartoon studio. “Pardon me. I’ve always wondered how they were made”, she inquires. The guard signals her with a shush to be very quiet, then unlocks the front door. He ushers her through three consecutive corridors, all including signs requesting “Silence”, then opens the final door. A barrage of animation drawing paper emerges in a flood from the doorway. When the paper clears, we see wall-to-wall activity, as animal artists churn out drawings from their drawing boards by the tons, randomly tossing them everywhere, while other stock bots round up the drawings in sky-high piles and carry them away. An orchestra performs hectic mood music in the background for the artists’ inspiration. A gag is used that John Foster must have thought hilarious, as he reused it time and again in both Van Beuren and later Terrytoons productions. Whenever the orchestra reaches a rapid, complicated passage in their music, everyone rolls off their seats, bobbing around like spilled marbles upon the floor, until the music pauses, then everyone slowly rises and eventually regains their seats.

A group of artists work side by side in the fashion of an assembly line, each one adding over and over again the same line, eyes, limbs, torso, etc. as each drawing is passed from one easel to another. (Unfortunately, this kind of production would not work out, as every drawing would retain the same pose!) One artist shows the value of live-action reference (something the actual Van Beuren artists probably could rarely afford), as a girl performs a belly dance in a series of held poses in different positions, while the artist renders each pose on paper, then the artist compares his drawing stack with the real thing by flipping the drawings while the girl dances at full speed, the actions of each matching precisely. In the process of the session, the artist’s pencil breaks, but is chewed sharp again by the teeth of a mouse who serves as pencil sharpener. A camera on a tripod, alive and with eyes rolling upon its film-reel canisters, dances its way over to each animator’s desk, easily and quickly photographing each artist’s stack of drawings as the srtist merely flips the paper before the camera. (Is there anyone in the industry who doesn’t wish it was that simple?) Soundtrack recording is also miraculously simplified, as the camera unreels its load onto a film winder (without so much as film processing to protect the film from exposure to light), lowers a gramophone recording horn with attached needle directly onto the film, and mutters “Run it”. The orchestra plays in a recording booth, and the sound waves are instantly transferred into a record-style groove right on the film (a method of sound recording nobody ever tried).

A group of artists work side by side in the fashion of an assembly line, each one adding over and over again the same line, eyes, limbs, torso, etc. as each drawing is passed from one easel to another. (Unfortunately, this kind of production would not work out, as every drawing would retain the same pose!) One artist shows the value of live-action reference (something the actual Van Beuren artists probably could rarely afford), as a girl performs a belly dance in a series of held poses in different positions, while the artist renders each pose on paper, then the artist compares his drawing stack with the real thing by flipping the drawings while the girl dances at full speed, the actions of each matching precisely. In the process of the session, the artist’s pencil breaks, but is chewed sharp again by the teeth of a mouse who serves as pencil sharpener. A camera on a tripod, alive and with eyes rolling upon its film-reel canisters, dances its way over to each animator’s desk, easily and quickly photographing each artist’s stack of drawings as the srtist merely flips the paper before the camera. (Is there anyone in the industry who doesn’t wish it was that simple?) Soundtrack recording is also miraculously simplified, as the camera unreels its load onto a film winder (without so much as film processing to protect the film from exposure to light), lowers a gramophone recording horn with attached needle directly onto the film, and mutters “Run it”. The orchestra plays in a recording booth, and the sound waves are instantly transferred into a record-style groove right on the film (a method of sound recording nobody ever tried).

The completed cartoon debuts to an audience of Aesop animals, as “Little Nell”. As in “Mutt and Jeff on Strike”, the real-life animators get to have some fun drawing deliberately bad, this time depicting their characters as modified stick figures. (Sometimes I’ve wondered if this was the proper level of art these animators were most suited for in the first place.) The “plot” is pure melodrama, with a moustached villain who plays his own chorus of standard sinister music on a saxophone, and also a musical raspberry to the booing and hissing audience. He sucks away the heroine upon his saxophone, and takes her to a sawmill. The girl refuses his offer of pearls, and is (unusual for a cartoon) beaten into unconsciousness, laid out upon a log heading for the buzzsaw. Just as it seems the buzzsaw blade with part her hair down the middle, a slide covers the screen with a projectionist’s call of trouble: “One moment, please.” The impatient and held-in-suspense audience rhythmically stamps its feet and claps its hands until the film gets rolling again. They cheer the next shot, showing the hero racing to the rescue. Back at the sawmill, the girl is not quite as unconscious as she appears, sliding a few extra feet away from the saw blade each time it comes close. The hero arrives, and takes a shot at the villain. He scores a hit, with the villain’s torso whirling around ad around as if pivoting upon his hip joints, finally landing in a heap in the corner. The bot leaps up upon the log, presses his foot upon the toes of the girl’s shoes to pivot her into a standing position, then carries her off the log, just as the saw slices clear through. “My hero”, responds Nell, and the two lock in a kiss, with a missed audio cue, as Nell’s lower torso sways like a wedding bell, but with no clang to signal the impending nuptials. A “The End” sign appears on the screen, after which the on-screen characters take curtain calls to the audience’s applause – all except the villain, who receives more boos and hisses, as the audience attacks the screen in a free-for-all brawl to end the film.

The completed cartoon debuts to an audience of Aesop animals, as “Little Nell”. As in “Mutt and Jeff on Strike”, the real-life animators get to have some fun drawing deliberately bad, this time depicting their characters as modified stick figures. (Sometimes I’ve wondered if this was the proper level of art these animators were most suited for in the first place.) The “plot” is pure melodrama, with a moustached villain who plays his own chorus of standard sinister music on a saxophone, and also a musical raspberry to the booing and hissing audience. He sucks away the heroine upon his saxophone, and takes her to a sawmill. The girl refuses his offer of pearls, and is (unusual for a cartoon) beaten into unconsciousness, laid out upon a log heading for the buzzsaw. Just as it seems the buzzsaw blade with part her hair down the middle, a slide covers the screen with a projectionist’s call of trouble: “One moment, please.” The impatient and held-in-suspense audience rhythmically stamps its feet and claps its hands until the film gets rolling again. They cheer the next shot, showing the hero racing to the rescue. Back at the sawmill, the girl is not quite as unconscious as she appears, sliding a few extra feet away from the saw blade each time it comes close. The hero arrives, and takes a shot at the villain. He scores a hit, with the villain’s torso whirling around ad around as if pivoting upon his hip joints, finally landing in a heap in the corner. The bot leaps up upon the log, presses his foot upon the toes of the girl’s shoes to pivot her into a standing position, then carries her off the log, just as the saw slices clear through. “My hero”, responds Nell, and the two lock in a kiss, with a missed audio cue, as Nell’s lower torso sways like a wedding bell, but with no clang to signal the impending nuptials. A “The End” sign appears on the screen, after which the on-screen characters take curtain calls to the audience’s applause – all except the villain, who receives more boos and hisses, as the audience attacks the screen in a free-for-all brawl to end the film.

Magic Art (Van Buren/Radio or Pathe?, Aesop’s Fables, 4/25/32 – John Foster/Harry Bailey, dir.) is a strange, nearly plotless cartoon, which might as easily have gone under the title of a later Little King production, “Art for Art’s Sake”. Waffles the dog observes a cat attempting to create art with a painters’ palette, canvas and easel. The cat seems pretty good, getting his tube of paint to stand up like a charmed snake, and splattering a few drops into Waffles’ eye, but in the end, the paint splatters all over his canvas, ruining his masterpiece. Waffles shows him up, producing from his pocket an enchanted artist’s pencil. He draws in mid-air a magician’s hat, producing from it various birds and a row of eggs, upon which two of the birds musically dance as if playing xylophone bars. (A break, possibly for censorship, omits whatever gag item or character hatched out of the eggs.) The cat is puzzled. Waffles then flings some lead, which looks more like ink, out of the end of the pencil, producing a dachshund. Waffles holds two fingertips together ro form a hoop for the dog to jump through, and the canine converts to a link of sausages as he passes through. “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet”, boasts Waffles, next sketching a stick-figure black firl, who serenades with the song “I Ain’t Got Nobody.” Waffles is further able to blow through the pencil, producing saxophone notes and a large soap bubble at the other end of the pencil.

Magic Art (Van Buren/Radio or Pathe?, Aesop’s Fables, 4/25/32 – John Foster/Harry Bailey, dir.) is a strange, nearly plotless cartoon, which might as easily have gone under the title of a later Little King production, “Art for Art’s Sake”. Waffles the dog observes a cat attempting to create art with a painters’ palette, canvas and easel. The cat seems pretty good, getting his tube of paint to stand up like a charmed snake, and splattering a few drops into Waffles’ eye, but in the end, the paint splatters all over his canvas, ruining his masterpiece. Waffles shows him up, producing from his pocket an enchanted artist’s pencil. He draws in mid-air a magician’s hat, producing from it various birds and a row of eggs, upon which two of the birds musically dance as if playing xylophone bars. (A break, possibly for censorship, omits whatever gag item or character hatched out of the eggs.) The cat is puzzled. Waffles then flings some lead, which looks more like ink, out of the end of the pencil, producing a dachshund. Waffles holds two fingertips together ro form a hoop for the dog to jump through, and the canine converts to a link of sausages as he passes through. “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet”, boasts Waffles, next sketching a stick-figure black firl, who serenades with the song “I Ain’t Got Nobody.” Waffles is further able to blow through the pencil, producing saxophone notes and a large soap bubble at the other end of the pencil.

With a wave of the magic drawing tool, Waffles converts the black singer into a canine chorus girl. The cat dances with her, and prepares to kiss her, but Waffles quickly sucks her back into the pencil. The cat gnaws at the pencil end, then spits out a rabbit. The cat seems to give up on the whole thing, while Waffles draws some large shoeprints on the ground. The prints travel across the ground to where the cat is sitting. From one footprint rises a boot, and from the boot a whole hobo, leaving behind a corked booze bottle. The cat struggles to pop the cork, but makes no progress. Waffles draws a pig with a curly tail to use as a corkscrew. The cat screws the bottle upon the pig’s tail, but the cork still won’t give way, as the frightened pig drags Waffles and the cat all around the barnyard. Finally, the bottle opens, but its contents won’t spill out. The cat inverts the bottle and taps on it, and suddenly the thing shoots into the skies as a skyrocket, exploding in a shower of stars. Forgetting about the prospects of an intoxicating drink, Waffles and the cat ooh and aah at the display, until the bottle falls from the sky, conking each of them upon the head. The two characters continue to ooh and ahh, at the further display of stars emitting from their own craniums, for a star-shaped iris out.

With a wave of the magic drawing tool, Waffles converts the black singer into a canine chorus girl. The cat dances with her, and prepares to kiss her, but Waffles quickly sucks her back into the pencil. The cat gnaws at the pencil end, then spits out a rabbit. The cat seems to give up on the whole thing, while Waffles draws some large shoeprints on the ground. The prints travel across the ground to where the cat is sitting. From one footprint rises a boot, and from the boot a whole hobo, leaving behind a corked booze bottle. The cat struggles to pop the cork, but makes no progress. Waffles draws a pig with a curly tail to use as a corkscrew. The cat screws the bottle upon the pig’s tail, but the cork still won’t give way, as the frightened pig drags Waffles and the cat all around the barnyard. Finally, the bottle opens, but its contents won’t spill out. The cat inverts the bottle and taps on it, and suddenly the thing shoots into the skies as a skyrocket, exploding in a shower of stars. Forgetting about the prospects of an intoxicating drink, Waffles and the cat ooh and aah at the display, until the bottle falls from the sky, conking each of them upon the head. The two characters continue to ooh and ahh, at the further display of stars emitting from their own craniums, for a star-shaped iris out.

Pencil Mania (Van Beuren/Radio, Tom and Jerry, 12/9/32 John Foster, George Stallings, dir,), presents nearly the same idea as the last all over again, in the same year of production, for its new characters Tom and Jerry (a Mutt and Jeff-style duo). In fact, it starts out almost identically. Tom is now the painter instead of the cat, and splashes paint in Jerry’s eye just the way the cat did to Waffles. Jerry’s first pencil trick is again with an egg, Tom marveling at how it remains suspended in mid-air, until he looks underneath it, and it falls with a splat into his eye. Tom tries to make the pencil perform for him, but nothing will draw in air. Jerry takes the instrument and sharpens it, each knife whittle producing a wooden shoe. Two birds suddenly appear, and perform a xylophone dance upon the shoes in the same manner as the eggs from the last production. Next, Jerry plays saxophone notes on the pencil again, though this time reshaping the pencil into an actual instrument. Watch for a new gag where Jerry’s notes, and the sax itself, convert into a line of waddling geese – you’ll see it again in a later Gandy Goose cartoon, “The Magic Pencil.” Jerry next draws three faces, on the bodies of a tomato, potato, and cucumber. (Was this the inspiration for Mr. Potato Head?) They sing a chorus of “Yes, We Have No Bananas”. Then Jerry stretches each face into a fully-rendered human character, providing a hero, heroine, and villain for another melodrama. There is no rationale behind their cavorting, but watch again for another gag where their chase enters a house, while Jerry draws wheels and fenders around the house doorway, converting it to a getaway car for the good guys – another gag later directly lifted into “The Magic Pencil”. The villain stows away in the rumble seat, but is socked back in by the girl. Suddenly, a rope ladder dangling from the sky passes the car, and the boy and girl grab it, climbing to a passing airplane with no pilot. The villain produces a rifle, taking pot shots at the plane from the car, but narrowly avoids disaster as the car plummets over a cliff. Another shot finally hits the mark, and the boy and girl fall from the sky. Somehow, the girl lands unharmed, in a stretch of land where Jerry has been drawing railroad tracks. The boy however, is dazed, and a hammer blow by the villain underneath the nero’s false blonde wig renders him unconscious on the tracks. A train approaches at full speed (something again previously seen, in stock shots from the year’s earlier T&J production. “Pots and Pans”. Tom stands nearby, unable to watch. But he opens his eyes to a surprising sight. The train somehow disappears from existence at a dividing line in the middle of the screen, vanishing piecemeal as it passes the line of no return. The hero somehow disappears too, leaving Tom alone to face the villain. Tom takes a sock at the villain’s chin, and he explodes, into a splash of ink on Tom’s hand. The girl enters the scene, with the usual read of “My hero”. But Jerry, appearing through a hole which he breaks in the background paper, sucks up the girl into his pencil before Tom can get a kiss. Tom leaps through the hole into another background, and pursues Jerry in perspective up a country road, for the iris out.

Pencil Mania (Van Beuren/Radio, Tom and Jerry, 12/9/32 John Foster, George Stallings, dir,), presents nearly the same idea as the last all over again, in the same year of production, for its new characters Tom and Jerry (a Mutt and Jeff-style duo). In fact, it starts out almost identically. Tom is now the painter instead of the cat, and splashes paint in Jerry’s eye just the way the cat did to Waffles. Jerry’s first pencil trick is again with an egg, Tom marveling at how it remains suspended in mid-air, until he looks underneath it, and it falls with a splat into his eye. Tom tries to make the pencil perform for him, but nothing will draw in air. Jerry takes the instrument and sharpens it, each knife whittle producing a wooden shoe. Two birds suddenly appear, and perform a xylophone dance upon the shoes in the same manner as the eggs from the last production. Next, Jerry plays saxophone notes on the pencil again, though this time reshaping the pencil into an actual instrument. Watch for a new gag where Jerry’s notes, and the sax itself, convert into a line of waddling geese – you’ll see it again in a later Gandy Goose cartoon, “The Magic Pencil.” Jerry next draws three faces, on the bodies of a tomato, potato, and cucumber. (Was this the inspiration for Mr. Potato Head?) They sing a chorus of “Yes, We Have No Bananas”. Then Jerry stretches each face into a fully-rendered human character, providing a hero, heroine, and villain for another melodrama. There is no rationale behind their cavorting, but watch again for another gag where their chase enters a house, while Jerry draws wheels and fenders around the house doorway, converting it to a getaway car for the good guys – another gag later directly lifted into “The Magic Pencil”. The villain stows away in the rumble seat, but is socked back in by the girl. Suddenly, a rope ladder dangling from the sky passes the car, and the boy and girl grab it, climbing to a passing airplane with no pilot. The villain produces a rifle, taking pot shots at the plane from the car, but narrowly avoids disaster as the car plummets over a cliff. Another shot finally hits the mark, and the boy and girl fall from the sky. Somehow, the girl lands unharmed, in a stretch of land where Jerry has been drawing railroad tracks. The boy however, is dazed, and a hammer blow by the villain underneath the nero’s false blonde wig renders him unconscious on the tracks. A train approaches at full speed (something again previously seen, in stock shots from the year’s earlier T&J production. “Pots and Pans”. Tom stands nearby, unable to watch. But he opens his eyes to a surprising sight. The train somehow disappears from existence at a dividing line in the middle of the screen, vanishing piecemeal as it passes the line of no return. The hero somehow disappears too, leaving Tom alone to face the villain. Tom takes a sock at the villain’s chin, and he explodes, into a splash of ink on Tom’s hand. The girl enters the scene, with the usual read of “My hero”. But Jerry, appearing through a hole which he breaks in the background paper, sucks up the girl into his pencil before Tom can get a kiss. Tom leaps through the hole into another background, and pursues Jerry in perspective up a country road, for the iris out.

NEXT: Moving into 1933 and beyond.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

I thought I was acquainted with the entire Waffles and Don filmography, but “Magic Art” is a new one to me. I look forward to making other discoveries as this series continues.

When Felix sees the high prices on the pearl necklaces in the jewelry store window, why doesn’t he just get his cartoonist friend to make a sign: “Free Samples — Take One”. I guess because if he did, the cartoon would only be five minutes long.

I was intrigued to see one “Jimmy Flora” credited as the organ accompanist on “My Old Kentucky Home”. There was a graphic artist named Jim Flora, famous for his distinctive cover art on many jazz albums. In 1926, however, Jim Flora was only twelve years old and still living in his native Ohio, so the organist on the cartoon’s soundtrack couldn’t possibly have been the same guy. Jim Flora had one cartoon connection that I know of: in the early 1950s, he storyboarded some animated commercials for UPA, under the direction of Gene Deitch.

The gag with the eighth notes turning into honking geese in “Pencil Mania” isn’t the only one that John Foster would later reuse in “The Magic Pencil”; the latter cartoon is like a lot of the plastic bottles one sees nowadays: “Contains over 50% recycled material.” It’s still a funny cartoon, and in many respects an improvement on its predecessor — but we’ll get to that at a future date.

Chuck Jones must’ve had Comicalities in the back of his head when he did Duck Amuck.

The myth that My Old Kentucky Home is the “real” first sound cartoon is stubborn.

Nearly a decade before he co-directed “Pencil Mania”, George Vernon Stallings directed and starred in “Col. Heeza Liar, Detective” (J. R. Bray, 1/2/23), in which a cartoon creation of ink and paper uses the magic of the medium to rectify injustice in our own world.

Stallings, at his drawing board, draws a picture of a door with a suit of clothes hanging on a peg next to it and a pair of shoes down below. The door opens a crack, and Col. Heeza Liar sticks his head out and says in an intertitle, “Good morning! I’ll be dressed in a minute!” He takes the clothes, and a moment later he emerges fully clad, tosses the door off into the distance, and in an amusing gag grabs the line that marked the juncture between the door and the floor and fashions it into a necktie.

The cartoonist’s friend Mr. Nutt drops in, proudly showing off a photo of a prize rooster he had just purchased for $10,000 in the hopes of starting a poultry business. But then Mrs. Nutt telephones with bad news: the rooster has been stolen! Heeza Liar offers to crack to case. Stallings tosses him a gun, badge, and deerstalker cap, which transform from three-dimensional objects into cartoon props as they enter the drawing board. Then he writes a letter of introduction to Mrs. Nutt, seals it into an envelope with Heeza Liar, and hands it to a messenger (a grizzled old man on roller skates) for delivery to the Nutts’ Long Island farm.

Upon arrival, Heeza bursts out of the envelope, and Mrs. Nutt takes him to the chicken coop to search for clues. He follows three sets of footprints in the snow and discovers a trio of hoboes feasting on roast chicken. Too late, right? Not for Heeza Liar it’s not! Heeza pulls a gun on the hoboes and demands: “Put that rooster back!” Through the miracle of reverse cinematography, the hoboes assemble the chicken pieces into a whole carcass; then, at Heeza’s continued urging, they reattach its feathers, wings, legs, and head. The rooster comes back to life and takes refuge in a drawstring bag as the hoboes head for the hills.

Back at the studio, Heeza restores the rooster to its owner and returns to his place on the drawing board. Mr. Nutt is overjoyed to have his rooster back — until he discovers to his horror that it has just laid an egg! “How dare you make a fool of me!” he rages, hurling the egg at the detective. “Well,” says Heeza as raw egg drips down over the drawing board, “she didn’t tell me she was that kind of rooster!”

The cartoon is available on home video as part of the Cartoon Roots collection of Tommy Jose Stathes, which I cannot recommend highly enough.