Animation is a medium that has fascinated and dazzled the eyes of audiences for over a century. The novelty of seeing line drawings move, seemingly under ther own power, was something akin to magic when it first appeared – only slightly more magical than the innovation of the motion picture itself, which already had performed miracles in allowing the relatively new industry of photography to take on the illusion of displaying life-like movement, even if prone to flicker and lack of smoothness of action between frames. Fascination level was so high, animation could even pass as a substitute for the live stage acts of Vaudeville, as in the instance of Winsor McCay’s clever interaction with an on-screen illustrated prehistoric monster in “Gertie the Dinosaur” – an act so popular, rival Bray Studios wert to all the trouble of attempting to copy the film verbatim for its own stage presentations. No doubt, those first exposed to these modern marvels had to wonder how in the world the miracle was achieved – and even when the basics of the process were known, how master producers like McCay, Max Fleischer, Walt Disney, Pat Sullivan, Bud Fischer, Walter Lantz, and even the lowly Paul Terry were able to pull it off. With no ready availability of art courses to teach the tricks of the trade, one can only imagine how many youths must have dabbled with doodles in flip-book fashion in hopes of figuring out the mysteries, only to be confounded by the rules of perspective, the uncharted territory of achieving special effects, and just the sheer labor-intensiveness of achieving satisfactory results for even a single scene.

Amid all this atmosphere of magic and mystery, many early animators decided that the time was right to let audiences in on their little game – sort of. For the most part, the industry was far from ready to yet display documentary-style presentations of the behind-the-scenes hell or humdrum of real-life animators, such as would begin to occur in the 1930’s with shorts such as Cartoonland Mysteries, or the extravaganza of in-house footage that would become Disney’s The Reluctant Dragon in the 1940’s. Instead, studios decided to play on the public’s imaginations of what might be going on within an animation studio, by developing fanciful depictions of an animator’s life, where creations of the pen spring off the drawing board, interact with their bosses, and wreak havoc upon the real world at the drop of a hat. Sometimes a real-life trick or two might be revealed as a plot point for the interplay between character and animator. But for the most part, the animator’s own world was generally depicted as nearly as distanced from reality as that of his 2-D creations. Other animators would leave reality altogether, finding ways of dropping out of the real world into the drawing board itself, to join their creatons in their own world of confusion and chaos.

A fascinating aspect of this unreal real-world concept was that on-screen animators were rarely able to maintain control of the situation. Generally with only a pen and eraser at hand, the animator was barely able to keep up with the antics of the starring character, who not only would usually dominate by the end of the picture, but displayed an uncanny savvy that he existed in a cartoon world, rather than merely in a self-existing universe mocking reality. The rules of physics didn’t apply to him – he could break them at will. He had freedom of choice, even as to his plane of existence, and could leave the drawing board whenever the need arose to mingle among the people, props and objects of real life. He could even create himself, often stealing the artist’s tools to create new worlds of fantasy within his own paper-and-ink world. Thus, a new level of film making was born – not only cartoons about animators and the animation process, but cartoons about characters who knew they were in cartoons, and had something to say about it and the medium in general.

Though the sheer abundance of this kind of animation product, particularly in the silent era, defies complete comprehensive coverage, I’ll try to provide a basic overview here, then move into films from the sound era where reality continued to get a kick n the pants, and characters insisted on having their own way with the medium, with or without the assistance of an animator’s pen. We’ll not attempt to itemize all instances of mere violations of physical rules – otherwise, we might have to critique every cartoon ever made. Our focus instead will be on films that exhibit either character self-consciousness of being drawn, or break the fourth wall to expressly remind the audience that the story you are about to see is false, not to be confused with anything else that may be observed on your planet. Also (with some exceptions), I’ll try to avoid mere backstage tales of Hollywood movie production in general, or of life upon the wicked stage, as these types of stories were equally prevalent in live-action, and not unique to the animated medium. Many of the films which will appear along this trail have been documented from time to time by other writers, so there will be several old familiar friends along the way. But there’ll also be the surprise from time to time of additional films not as well known or subject to review, to provide variety as we go. Again, I strongly suspect there will be omissions, some inadvertent, perhaps a few intentional, along our trail of films, which might fit the category for one reason or another. So, audience participation is again invited as usual to fill in any holes, whether left by me or Professor Calvin Q. Calculus.

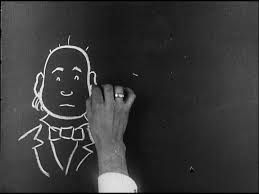

Among the earliest surviving films about the simple science of making drawings move is Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (J. Stuart Blackton/Vitagraph Company of America, 4/6/1906), a plotless collection of four segments, seeming to be drawn in chalk by an artist (unseen except for his hand) on a chalkboard. Some of the segments appear to play it straight, using actual chalk drawings with frame-by-frame embellishment. A few others seem suspect, with portions or all of outlines appearing to be too uniform from frame to frame and yet moving across the screen, suggesting the substitution of some form of primitive cel or cutout animation in place of actual chalk sketching, or, if in fact drawn in chalk, the use of stencils to keep features precise in size wherever drawn. The effect has a fascinating appeal in the scenes actually hand-drawn, although the shutter of the camera takes light in rather irregularly, lending the images very noticeable flicker between respective drawings. (One curious artifact in the last sequence, despite being the most notably composed either of cutouts or stencils, is the accidental appearance of the artist’s hand in the frame in several repositionings of the drawing. The cameraman must have been in a hurry to get home, unwilling to allow sufficient time for the artist to get out of the way!) Short segments include a portly man and a prim matron, making flirtatious smiles at one another, but the man appearing to become more prominent, acquiring a top hat and black cigar, and rudely blowing a cloud of smoke into the matron’s face.

Among the earliest surviving films about the simple science of making drawings move is Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (J. Stuart Blackton/Vitagraph Company of America, 4/6/1906), a plotless collection of four segments, seeming to be drawn in chalk by an artist (unseen except for his hand) on a chalkboard. Some of the segments appear to play it straight, using actual chalk drawings with frame-by-frame embellishment. A few others seem suspect, with portions or all of outlines appearing to be too uniform from frame to frame and yet moving across the screen, suggesting the substitution of some form of primitive cel or cutout animation in place of actual chalk sketching, or, if in fact drawn in chalk, the use of stencils to keep features precise in size wherever drawn. The effect has a fascinating appeal in the scenes actually hand-drawn, although the shutter of the camera takes light in rather irregularly, lending the images very noticeable flicker between respective drawings. (One curious artifact in the last sequence, despite being the most notably composed either of cutouts or stencils, is the accidental appearance of the artist’s hand in the frame in several repositionings of the drawing. The cameraman must have been in a hurry to get home, unwilling to allow sufficient time for the artist to get out of the way!) Short segments include a portly man and a prim matron, making flirtatious smiles at one another, but the man appearing to become more prominent, acquiring a top hat and black cigar, and rudely blowing a cloud of smoke into the matron’s face.

Transitions between segments are accomplished by the artist using an eraser and washcloth to obliterate the images with spiral strokes. The second sequence, filmed in stencil or cutout, briefly shows another prosperous man with a top hat, tailed coat, and umbrella. The third segment doesn’t make much sense, featuring an old-timer and another woman, but for no apparent reason presented as filmed backwards! The final shot is the most elaborate (and should have been mentioned in my previous series on circuses), featuring a clown holding a hoop, and performing in an act where his little dog, in highly-stilted fashion, jumps through it. Just when you’re sure the whole shot was composed on negative film with cutouts, the artist’s hand appears again, and erases half the image with eraser and cloth in the same manner as the previous segments, seemingly demonstrating that the image somehow really is of chalk on a blackboard. However, there is yet a final surprise, as the remaining half of the drawing refuses to be put out of existence, and attempts to further move, before the artist re-moistens his erasing cloth and completes the task. A nice trick, again suggesting that stencils were used rather than paper cutouts, to allow for the final eraser effect.

Transitions between segments are accomplished by the artist using an eraser and washcloth to obliterate the images with spiral strokes. The second sequence, filmed in stencil or cutout, briefly shows another prosperous man with a top hat, tailed coat, and umbrella. The third segment doesn’t make much sense, featuring an old-timer and another woman, but for no apparent reason presented as filmed backwards! The final shot is the most elaborate (and should have been mentioned in my previous series on circuses), featuring a clown holding a hoop, and performing in an act where his little dog, in highly-stilted fashion, jumps through it. Just when you’re sure the whole shot was composed on negative film with cutouts, the artist’s hand appears again, and erases half the image with eraser and cloth in the same manner as the previous segments, seemingly demonstrating that the image somehow really is of chalk on a blackboard. However, there is yet a final surprise, as the remaining half of the drawing refuses to be put out of existence, and attempts to further move, before the artist re-moistens his erasing cloth and completes the task. A nice trick, again suggesting that stencils were used rather than paper cutouts, to allow for the final eraser effect.

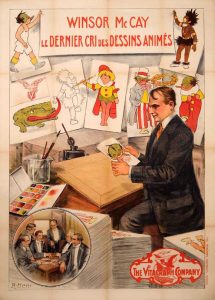

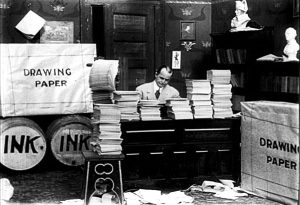

Little Nemo (Winsor McCay/Vitagraph, 4/8/1911) is definitely a film about animation, though most of the self-referential footage is shot in live action. It was McCay’s debut in the field, containing approximately 4,000 paper drawings, and photographed under the supervision of Blackton. Though initially produced in traditional black-and-white, McCay responded quickly to favorable audience reaction, by adding color through a frame-by-frame tinting process shortly afterwards (which fortunately survives). In the live-action intro, McCay is scoffed at by fellow New York artists when he proposes to try his hand at creating a film with drawings that move. He begins on a large screen-sized drawing board, consuming a couple of minutes’ footage in demonstrating the effort of composing single drawings by hand. The scenes are shot without animation, but compress time by stop-motion photography of the hand in the course of drawing, speeding up the process somewhat for the sake of brevity of footage and not totally boring the audience. Notably, there is a break in photography on the first drawing every time McCay completes the image of one of its three characters – a wise move, substituting a duplicate of those portions of the drawing already completed in place of the original, in case the on-screen creation of the next character doesn’t come out as hoped for or gets smudged. Once McKay has completed three sample drawings, in masterful form, he wagers his rivals that he can create 4,000 drawings within a month that will move. The bet is on (though the stakes are never stated). McCay disappears into a moderate-sized office at Vitagraph studios, which quickly becomes quite crowded, as several prop-men tote in bundles of hundreds of reams of drawing paper, and three large barrels marked “Ink”.

Little Nemo (Winsor McCay/Vitagraph, 4/8/1911) is definitely a film about animation, though most of the self-referential footage is shot in live action. It was McCay’s debut in the field, containing approximately 4,000 paper drawings, and photographed under the supervision of Blackton. Though initially produced in traditional black-and-white, McCay responded quickly to favorable audience reaction, by adding color through a frame-by-frame tinting process shortly afterwards (which fortunately survives). In the live-action intro, McCay is scoffed at by fellow New York artists when he proposes to try his hand at creating a film with drawings that move. He begins on a large screen-sized drawing board, consuming a couple of minutes’ footage in demonstrating the effort of composing single drawings by hand. The scenes are shot without animation, but compress time by stop-motion photography of the hand in the course of drawing, speeding up the process somewhat for the sake of brevity of footage and not totally boring the audience. Notably, there is a break in photography on the first drawing every time McCay completes the image of one of its three characters – a wise move, substituting a duplicate of those portions of the drawing already completed in place of the original, in case the on-screen creation of the next character doesn’t come out as hoped for or gets smudged. Once McKay has completed three sample drawings, in masterful form, he wagers his rivals that he can create 4,000 drawings within a month that will move. The bet is on (though the stakes are never stated). McCay disappears into a moderate-sized office at Vitagraph studios, which quickly becomes quite crowded, as several prop-men tote in bundles of hundreds of reams of drawing paper, and three large barrels marked “Ink”.

Once the supplies are loaded in, McCay sets feverishly to work. An office boy enters with a feather duster, first attending to his task, but dying of curiosity over McCay’s work. He pauses to roll a large wheel on which McCay has placed about a hundred drawings to test them for movement in flip-book style, though McCay attempts to shoo him away. The nosy boy returns, to peer over the top of tall stacks of drawings upon McCay’s desk, failing to notice that his belly is bumping into another stack of drawings balanced on a stool. Comically, the stool full of drawings is knocked over, and as the boy leans further forward in attempt to catch them, three-quarters of the drawings on the desk are dislodged, landing with the boy on the office floor in a hopeless jumble. (It’s a good thing these paper “drawings” were merely comic props, as the tearing, folds, and dog-eared corners that might have resulted from a real fall would probably have rendered many valuable drawings unsuitable for photography before the camera.) Finally, the finished film is shown. The color-tinted version is typically spliced in at this point, though it is odd that a still of the character Flip transforms back to black and white as the words “Watch Me Move” appear above his head, suggesting that these frames were for no understandable reason removed from the hand-colored re-release print. There is no plot, but a brief battle ensues between Flip and the native Impie. Nemo appears in resplendent robes, and performs what may be animation’s first use of squash-and-stretch, distorting and bending his pals’ bodies at will with mere waves of his hand. (Distortion poses of this sort had actually appeared within frames of the Nemo comic strip,) Nemo himself draws the Princess into existence, hands her a conveniently-sprouted rose, and the two ride away on a throne which is really the rolled-up tongue of a dragon. (It is fortunate that the color version was eventually located, as surviving copies of the original black and white traditionally exhibit a large break during the dragon animation, making the film come out at least 24 drawings shy of the requisite number to win the bet.) Flip and Impie drive in aboard an old jalopy, but it explodes, causing them to land upon a character named Doctor Pill. The action suddenly freezes abruptly, and the camera pulls back to reveal an inscription at the base of the last drawing, reading “No. 4000″.

Once the supplies are loaded in, McCay sets feverishly to work. An office boy enters with a feather duster, first attending to his task, but dying of curiosity over McCay’s work. He pauses to roll a large wheel on which McCay has placed about a hundred drawings to test them for movement in flip-book style, though McCay attempts to shoo him away. The nosy boy returns, to peer over the top of tall stacks of drawings upon McCay’s desk, failing to notice that his belly is bumping into another stack of drawings balanced on a stool. Comically, the stool full of drawings is knocked over, and as the boy leans further forward in attempt to catch them, three-quarters of the drawings on the desk are dislodged, landing with the boy on the office floor in a hopeless jumble. (It’s a good thing these paper “drawings” were merely comic props, as the tearing, folds, and dog-eared corners that might have resulted from a real fall would probably have rendered many valuable drawings unsuitable for photography before the camera.) Finally, the finished film is shown. The color-tinted version is typically spliced in at this point, though it is odd that a still of the character Flip transforms back to black and white as the words “Watch Me Move” appear above his head, suggesting that these frames were for no understandable reason removed from the hand-colored re-release print. There is no plot, but a brief battle ensues between Flip and the native Impie. Nemo appears in resplendent robes, and performs what may be animation’s first use of squash-and-stretch, distorting and bending his pals’ bodies at will with mere waves of his hand. (Distortion poses of this sort had actually appeared within frames of the Nemo comic strip,) Nemo himself draws the Princess into existence, hands her a conveniently-sprouted rose, and the two ride away on a throne which is really the rolled-up tongue of a dragon. (It is fortunate that the color version was eventually located, as surviving copies of the original black and white traditionally exhibit a large break during the dragon animation, making the film come out at least 24 drawings shy of the requisite number to win the bet.) Flip and Impie drive in aboard an old jalopy, but it explodes, causing them to land upon a character named Doctor Pill. The action suddenly freezes abruptly, and the camera pulls back to reveal an inscription at the base of the last drawing, reading “No. 4000″.

The “Out of the Inkwell” series, first conceived while Max Fleischer was distribting through the Bray studio, was all about the craft of animation. Nearly every film followed a formula. Max would uncork an inkwell on his desk, dip his pen, then proceed to create a drawing on a large drawing pad. Each film seemed to take pride in allowing Max to create his primary character, Koko the Clown, in a different way. (Many are highly creative, including “Puzzle”, in which Koko is assembled from random puzzle parts.) Koko interacts with Max, making statements or asking questions in either comic-strip balloon form or as full-screen intertitles. Often, he asks Max to offer help, by drawing in some person, animal, or prop. Frequently, Koko either borrows objects from Max’s desk or has them handed up to him by Max onto the board upon request, for use in Koko’s latest endeavors. As the series progressed, Koko would become more venturous, leaving the drawing board whenever he had a score to settle with Max, or sometimes just for a jaunt into the heart of New York City. In still later episodes, Koko would partner-up with a pet dog named Fitz, sometimes for a common goal, but in others at rival cross-purposes, providing Koko with a dependable comic foil (and eventually leading to Fitz essentially sharing billing with Koko as a team, when Paramount changed the name of the series to “The Inkwell Imps.” Primary among the themes of the series was the fact that Koko was among the first characters to consciously realize he had just come out of a pen, and was a creation of ink. He knew his medium, and realized both its strengths and limitations. (In “Fade Away”, for example, he soon discovers and makes appropriate adjustments for Max’s substitution of disappearing ink on the drawing board.) Most importantly, Koko knew how to make an exit. Whenever things would get too hot for him, or a vengeful Max was right on his tail, Koko could always find refuge by merely hopping into the inkwell, returning to the element from which he was created and becoming one with it, with Max usually plugging up the bottle with the stopper (though even this had many variants, sometimes Koko pulling in the stopper upon himself, sometimes the bottle being tipped by Max in fruitless search for Koko, only to find him completely dissolved and merged into the flow of ink, and at least once with Koko and Fitz never making it back to the inkwell, as their pull on an “Earth Control” handle has brought about the end of the world, and the violent tipping of Max’s desk merely dissolves them into a puddle of ink upon the desk’s surface.

The “Out of the Inkwell” series, first conceived while Max Fleischer was distribting through the Bray studio, was all about the craft of animation. Nearly every film followed a formula. Max would uncork an inkwell on his desk, dip his pen, then proceed to create a drawing on a large drawing pad. Each film seemed to take pride in allowing Max to create his primary character, Koko the Clown, in a different way. (Many are highly creative, including “Puzzle”, in which Koko is assembled from random puzzle parts.) Koko interacts with Max, making statements or asking questions in either comic-strip balloon form or as full-screen intertitles. Often, he asks Max to offer help, by drawing in some person, animal, or prop. Frequently, Koko either borrows objects from Max’s desk or has them handed up to him by Max onto the board upon request, for use in Koko’s latest endeavors. As the series progressed, Koko would become more venturous, leaving the drawing board whenever he had a score to settle with Max, or sometimes just for a jaunt into the heart of New York City. In still later episodes, Koko would partner-up with a pet dog named Fitz, sometimes for a common goal, but in others at rival cross-purposes, providing Koko with a dependable comic foil (and eventually leading to Fitz essentially sharing billing with Koko as a team, when Paramount changed the name of the series to “The Inkwell Imps.” Primary among the themes of the series was the fact that Koko was among the first characters to consciously realize he had just come out of a pen, and was a creation of ink. He knew his medium, and realized both its strengths and limitations. (In “Fade Away”, for example, he soon discovers and makes appropriate adjustments for Max’s substitution of disappearing ink on the drawing board.) Most importantly, Koko knew how to make an exit. Whenever things would get too hot for him, or a vengeful Max was right on his tail, Koko could always find refuge by merely hopping into the inkwell, returning to the element from which he was created and becoming one with it, with Max usually plugging up the bottle with the stopper (though even this had many variants, sometimes Koko pulling in the stopper upon himself, sometimes the bottle being tipped by Max in fruitless search for Koko, only to find him completely dissolved and merged into the flow of ink, and at least once with Koko and Fitz never making it back to the inkwell, as their pull on an “Earth Control” handle has brought about the end of the world, and the violent tipping of Max’s desk merely dissolves them into a puddle of ink upon the desk’s surface.

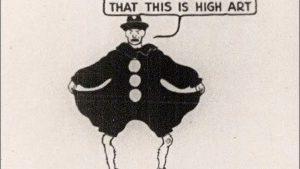

We’ll feature two entries from the series here (though every episode could conceivably fit our category). First, the little-known The Clown’s Pup (Fleischer/Bray, 8/30/19), said (at present) to be the earliest surviving installment of the Bray Studios’ product. It is very short in length, far less than a reel, possibly intended for inclusion in a “screen magazine” format to sandwich it in with the work of other animators on a double or triple-feature reel. Max begins by drawing Koko’s face, then in pieces the outline of Koko’s hat, collar (tossed over his head loosely in the manner one might have a flower lei tossed on while visiting Hawaii),, and several individual buttons, which the clown himself seems to will to travel over to appropriate positions upon his chest. Two wiggly lines are drawn separately, which Koko reaches for with his newly-drawn hands, then bends to shape as if they were each a pantleg into which he was inserting an invisible foot, forming the lower half of his body. Finally, Max uses the pen to blacken-in Koko’s costume. “That’s pretty fair”, responds Koko. “What do you mean, pretty fair?” inquires Max, by drawing the words of the inquiry upon Koko’s drawing paper. Koko lifts his pantlegs high, exposing a bony-looking pair of legs and ankles underneath. “You don’t mean to say that this is high art?” quips Koko. Even Max thinks the clown’s limbs unsightly, and hides his eyes, waving to Koko to lower his hemline. Max covers the lower half of the drawing pad with his hand, and Koko remarks, “Alright, censor.” Koko inquires if Max has ever seen him draw. Borrowing Max’s pen, Koko creates his own pet – a four-legged oval with a sort of canine head, which he calls a bulldog. Max responds that he looks more like “a full-blooded Cruller.” Max shows Koko up, by drawing in a more realistic bulldog. The two canines take an instant disliking to one another and a dogfight begins. In a longshot, both Max and Koko observe the fight with wonder from the sidelines. Then, Koko somehow finds himself in the middle of the action, with the two dogs chomping into each of Koko’s respective pantlegs. Koko calls for Max’s help, requesting that he open the ink bottle. As would become the custom, Koko dives, with the two dogs still clinging to him, inside the bottle, and Max inserts the stopper for the iris out.

We’ll feature two entries from the series here (though every episode could conceivably fit our category). First, the little-known The Clown’s Pup (Fleischer/Bray, 8/30/19), said (at present) to be the earliest surviving installment of the Bray Studios’ product. It is very short in length, far less than a reel, possibly intended for inclusion in a “screen magazine” format to sandwich it in with the work of other animators on a double or triple-feature reel. Max begins by drawing Koko’s face, then in pieces the outline of Koko’s hat, collar (tossed over his head loosely in the manner one might have a flower lei tossed on while visiting Hawaii),, and several individual buttons, which the clown himself seems to will to travel over to appropriate positions upon his chest. Two wiggly lines are drawn separately, which Koko reaches for with his newly-drawn hands, then bends to shape as if they were each a pantleg into which he was inserting an invisible foot, forming the lower half of his body. Finally, Max uses the pen to blacken-in Koko’s costume. “That’s pretty fair”, responds Koko. “What do you mean, pretty fair?” inquires Max, by drawing the words of the inquiry upon Koko’s drawing paper. Koko lifts his pantlegs high, exposing a bony-looking pair of legs and ankles underneath. “You don’t mean to say that this is high art?” quips Koko. Even Max thinks the clown’s limbs unsightly, and hides his eyes, waving to Koko to lower his hemline. Max covers the lower half of the drawing pad with his hand, and Koko remarks, “Alright, censor.” Koko inquires if Max has ever seen him draw. Borrowing Max’s pen, Koko creates his own pet – a four-legged oval with a sort of canine head, which he calls a bulldog. Max responds that he looks more like “a full-blooded Cruller.” Max shows Koko up, by drawing in a more realistic bulldog. The two canines take an instant disliking to one another and a dogfight begins. In a longshot, both Max and Koko observe the fight with wonder from the sidelines. Then, Koko somehow finds himself in the middle of the action, with the two dogs chomping into each of Koko’s respective pantlegs. Koko calls for Max’s help, requesting that he open the ink bottle. As would become the custom, Koko dives, with the two dogs still clinging to him, inside the bottle, and Max inserts the stopper for the iris out.

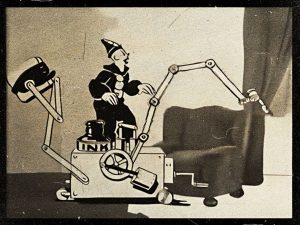

Cartoon Factory (Fleischer, 2/21/24) is an episode transcending Max and the drawing board, in which Max attempts to raise animation to the next level – mass-production. (Sounds sort of like television.) Max starts the drawing off with a rudimentary background, and the top half of Koko, who remains still and motionless. But Max has added a few wrinkles to his animation desk, in the form of various power boxes, switches, and dials which look much like they were lifted from some kid’s electric train set. At the throw of a switch, wires draped loosely over the desk-cover holding Max’s art tools electrify the ink bottle and various art implements, causing them in stop-motion to scurry all over the desk. Shutting off the switch makes the objects briefly lifeless again, so Max knows he is in control. Shooting the juice to the desk cover again, Max has his pen automatically finish the drawing of Koko electrically, without the aid of human hand. The finished Koko still remains stationary, until Max hooks a wire from a second power transformer under Koko’s shirt. Max turns a dial, initiating and increasing voltage to Koko, who awakens with a bolt-start, and begins walking across the background. Max sadistically cranks up the ampage of the transformer box to maximum, tripling the speed of Koko’s walk, causing the clown to shout, “WOW! Shut it off!” Max finally obliges, giving Koko some brief relief. But a surprise awaits Koko, as Max electrifies his pen into action again. A mobile invention is created before Koko’s eyes, featuring a crank that resembles the starting crank ignition of a Model T, a goodly supply of ink in an oversized bottle, and two extendable mechanical arms, one equipped with a pen attachment, and another an eraser. As Koko gives the crank a spin, the drawing arm of the device creates in outline form on a blank wall the image of a roast turkey, a fork and knife. Koko’s mouth waters, and he prepares to reach for the splendid meal. But a split-second before he can, the eraser arm barges in, wiping away the image entirely before Koko can get one bite. Koko shouts at the device, demanding that it put that turkey back where it was. The drawing arm goes to work again, but instead of a turkey, draws an attractive female. Koko is taken aback, and reacts with coy shyness, as the gitl magically begins to move, making friendly overtures, and puckering up for a kiss. Koko closes his eyes, and bends forward to receive the smooch. The eraser arm resorts to its old tricks, wiping away the girl, leaving Koko to get a kiss of bare wallpaper. Koko decides to take charge of the device, giving it another crank, then hopping on for a ride. The drawing arm works like mad, drawing in new backgrounds wherever it goes, and finally, the wall of a house in front of Koko with open doorway. The device rolls inside, and proves it can illustrate better than a cartoon, drawing in furnishings and carpet for the house which are actually images from the real world, fully shadowed in photographic image.

Cartoon Factory (Fleischer, 2/21/24) is an episode transcending Max and the drawing board, in which Max attempts to raise animation to the next level – mass-production. (Sounds sort of like television.) Max starts the drawing off with a rudimentary background, and the top half of Koko, who remains still and motionless. But Max has added a few wrinkles to his animation desk, in the form of various power boxes, switches, and dials which look much like they were lifted from some kid’s electric train set. At the throw of a switch, wires draped loosely over the desk-cover holding Max’s art tools electrify the ink bottle and various art implements, causing them in stop-motion to scurry all over the desk. Shutting off the switch makes the objects briefly lifeless again, so Max knows he is in control. Shooting the juice to the desk cover again, Max has his pen automatically finish the drawing of Koko electrically, without the aid of human hand. The finished Koko still remains stationary, until Max hooks a wire from a second power transformer under Koko’s shirt. Max turns a dial, initiating and increasing voltage to Koko, who awakens with a bolt-start, and begins walking across the background. Max sadistically cranks up the ampage of the transformer box to maximum, tripling the speed of Koko’s walk, causing the clown to shout, “WOW! Shut it off!” Max finally obliges, giving Koko some brief relief. But a surprise awaits Koko, as Max electrifies his pen into action again. A mobile invention is created before Koko’s eyes, featuring a crank that resembles the starting crank ignition of a Model T, a goodly supply of ink in an oversized bottle, and two extendable mechanical arms, one equipped with a pen attachment, and another an eraser. As Koko gives the crank a spin, the drawing arm of the device creates in outline form on a blank wall the image of a roast turkey, a fork and knife. Koko’s mouth waters, and he prepares to reach for the splendid meal. But a split-second before he can, the eraser arm barges in, wiping away the image entirely before Koko can get one bite. Koko shouts at the device, demanding that it put that turkey back where it was. The drawing arm goes to work again, but instead of a turkey, draws an attractive female. Koko is taken aback, and reacts with coy shyness, as the gitl magically begins to move, making friendly overtures, and puckering up for a kiss. Koko closes his eyes, and bends forward to receive the smooch. The eraser arm resorts to its old tricks, wiping away the girl, leaving Koko to get a kiss of bare wallpaper. Koko decides to take charge of the device, giving it another crank, then hopping on for a ride. The drawing arm works like mad, drawing in new backgrounds wherever it goes, and finally, the wall of a house in front of Koko with open doorway. The device rolls inside, and proves it can illustrate better than a cartoon, drawing in furnishings and carpet for the house which are actually images from the real world, fully shadowed in photographic image.

What causes the next events to occur is a bit unclear. The drawing device rolls back outside, and approaches the door of a machine shop. (Where the shop came from is unknown – perhaps it was drawn in as part of the scrolling backgrounds by the machine when no one was looking.) Koko goes in, and finds a stamping device pressing out miscellaneous parts that squirt out of the machine to land respectively in one of two holding hampers. Koko rummages through the various parts, and comes up with a rolling four-wheeled platform, various robotic steel limbs and a large spring which he uses for a neck support (much like the modern bobble-head), and a head resembling a toy soldier – but with the actual face of the live-action Max (a cut-out from a still portrait). He assembles the parts before our eyes (including pressing into place Max’s head onto the neck spring), obtains garb for the creation from the machine’s output to dress it in a soldier uniform (also cutouts from a photographic image of the live Max), then prepares to launch his creation into the outside world. The rolling platform instead shifts into reverse, rebounds off Koko, and rolls Max-soldier outside free. Koko catches up to it, and rides it into the house, where it finally comes to a stop. Koko removes the Max-soldier’s head, applying a little oil., then bops the head back into place. From Max’s back, Koko pulls a pull-string, common to old talking dolls, then pauses outside the house door to watch his creation in action. Being a silent movie, Max-soldier does not perform like a talking doll. Instead, switching to live footage, Max (the real one in soldier outfit) takes the place of his cutout on the screen amidst the “painted” live furnished room, and begins drawing the outlines of multiple toy soldiers his own size on the wallpaper. Koko wonders what’s the idea, until the Max-soldier issues vocal orders to his “troops”. “About Face”, and “Charge!”. The outline soldiers, not dependent upon their rolling bases or pull strings, jump off the platforms and stampede after Koko. Koko races to where he parked the cartoon machine, and once again cranks it into action. Activating the eraser arm, Koko sets it swinging rapidly, just as the pursuing soldiers come into arm’s reach. As fast as they arrive, they are erased from existence. Back at the house, Max-soldier is still drawing new recruits, but the eraser obliterates them faster than Max can draw them. This allows Koko to gain ground, and drive his machine up to the doorway of the house. There, Koko employs the machine’s drawing arm to create for him a cannon. Perhaps unwisely, the cartoon machine s shoed away by the clown, to allow him to roll the cannon into place at the door and take aim. He fires, and Max-soldier’s drawing spree is abruptly interrupted, as he is hit with a cocoanut-sized cannonball which bounces like rubber off of him. Koko finds that his cartoon cannon has rapid fire action like a machine gun, and can fire multiple balls in the same shot as well. Koko increases the barrage, first firing in twos, then threes, then fours, then finally just pulling the firing pin every second, to pelt his adversary with volleys. The live room rapidly gets crowded with cannonballs, and Max-soldier no longer has the strength or balance to stand. But, back at the machine shop, the stamping device continues to churn out parts, which now, on their own, assemble themselves into more duplicates of live Max-soldier – a legion of them, rolling off the presses one behind the other in a military line. ‘Uh oh”, reacts Koko in shock, and witn the cartoon machine gone (Would the eraser have been able to rub out live-action Maxes anyway?), Koko turns to his last line of defense – running for it. The soldiers pursue him through the house, then out the back door. When Koko reaches the back porch, he hops off the drawing board, back into his comfortable inkwell. Though no one has pulled any strings to start the soldiers’ motors independent of their platforms, the soldiers (now with substitution of shaded line drawings to allow for motion without filming Max) each hop off their platforms as they emerge from the door, following Koko into the open inkwell. Back in the “real” world, Max the animator decides the time has come to put an end to this nonsense, shutting off the electrical current to stop the never-ending flow of new soldiers, then inserting the stopper into the ink bottle for the usual finale.

What causes the next events to occur is a bit unclear. The drawing device rolls back outside, and approaches the door of a machine shop. (Where the shop came from is unknown – perhaps it was drawn in as part of the scrolling backgrounds by the machine when no one was looking.) Koko goes in, and finds a stamping device pressing out miscellaneous parts that squirt out of the machine to land respectively in one of two holding hampers. Koko rummages through the various parts, and comes up with a rolling four-wheeled platform, various robotic steel limbs and a large spring which he uses for a neck support (much like the modern bobble-head), and a head resembling a toy soldier – but with the actual face of the live-action Max (a cut-out from a still portrait). He assembles the parts before our eyes (including pressing into place Max’s head onto the neck spring), obtains garb for the creation from the machine’s output to dress it in a soldier uniform (also cutouts from a photographic image of the live Max), then prepares to launch his creation into the outside world. The rolling platform instead shifts into reverse, rebounds off Koko, and rolls Max-soldier outside free. Koko catches up to it, and rides it into the house, where it finally comes to a stop. Koko removes the Max-soldier’s head, applying a little oil., then bops the head back into place. From Max’s back, Koko pulls a pull-string, common to old talking dolls, then pauses outside the house door to watch his creation in action. Being a silent movie, Max-soldier does not perform like a talking doll. Instead, switching to live footage, Max (the real one in soldier outfit) takes the place of his cutout on the screen amidst the “painted” live furnished room, and begins drawing the outlines of multiple toy soldiers his own size on the wallpaper. Koko wonders what’s the idea, until the Max-soldier issues vocal orders to his “troops”. “About Face”, and “Charge!”. The outline soldiers, not dependent upon their rolling bases or pull strings, jump off the platforms and stampede after Koko. Koko races to where he parked the cartoon machine, and once again cranks it into action. Activating the eraser arm, Koko sets it swinging rapidly, just as the pursuing soldiers come into arm’s reach. As fast as they arrive, they are erased from existence. Back at the house, Max-soldier is still drawing new recruits, but the eraser obliterates them faster than Max can draw them. This allows Koko to gain ground, and drive his machine up to the doorway of the house. There, Koko employs the machine’s drawing arm to create for him a cannon. Perhaps unwisely, the cartoon machine s shoed away by the clown, to allow him to roll the cannon into place at the door and take aim. He fires, and Max-soldier’s drawing spree is abruptly interrupted, as he is hit with a cocoanut-sized cannonball which bounces like rubber off of him. Koko finds that his cartoon cannon has rapid fire action like a machine gun, and can fire multiple balls in the same shot as well. Koko increases the barrage, first firing in twos, then threes, then fours, then finally just pulling the firing pin every second, to pelt his adversary with volleys. The live room rapidly gets crowded with cannonballs, and Max-soldier no longer has the strength or balance to stand. But, back at the machine shop, the stamping device continues to churn out parts, which now, on their own, assemble themselves into more duplicates of live Max-soldier – a legion of them, rolling off the presses one behind the other in a military line. ‘Uh oh”, reacts Koko in shock, and witn the cartoon machine gone (Would the eraser have been able to rub out live-action Maxes anyway?), Koko turns to his last line of defense – running for it. The soldiers pursue him through the house, then out the back door. When Koko reaches the back porch, he hops off the drawing board, back into his comfortable inkwell. Though no one has pulled any strings to start the soldiers’ motors independent of their platforms, the soldiers (now with substitution of shaded line drawings to allow for motion without filming Max) each hop off their platforms as they emerge from the door, following Koko into the open inkwell. Back in the “real” world, Max the animator decides the time has come to put an end to this nonsense, shutting off the electrical current to stop the never-ending flow of new soldiers, then inserting the stopper into the ink bottle for the usual finale.

It should be mentioned that Fleisher also had a short-lived alternative series called “Inklings”, which depended not so much on motion animation, but upon depictions of a still-frame hand performing speed-sketches in time-compressed stop motion, then re-arranging elements of the sketch to transform the image into the portrait of some famous person, or to assemble a puzzle from the pieces that would construct into some surprise object. Though definitely films about the art of drawing, they are not really even up to the level of “Humorous Phases” discussed above, in that their subjects don’t take on life of their own, nor are cognizant of it, so the concept merely receives an honorable mention here.

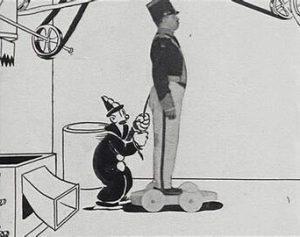

Others at Bray would attempt to copy or incorporate Fleischer’s successful concepts into their own films. Though inconsistently utilized in the series, Earl Hurd’s semi-realistic “Bobby Bumps” series was known to include episodes where Bobby is obviously aware of his cartoon existence. Perhaps the most well-known example, in the most available of his films, appears in Bobby Bumps Puts a Beanery On the Bum (12/4/18). The film begins on a drawing pad, with no live-action footage seen – only the “hand” of an animator, rendered by photographic stills placed onto cels or cutouts amidst the animated elements. The animator’s pen begins drawing Bobby in a lazy recline upon the bare paper. Bobby is quite aware he is being drawn, as he sleepily raises one leg to allow the artist to draw in the back side of his limbs while it is raised. The animator writes in on-screen letters to give instruction to Bobby, including “Hat off” to allow the pen to black-in Bobby’s hair, and “Roll over”, allowing the hand to pour some ink on the seat of Bobby’s pants to blacken-in its backside. Rising, Bobby climbs aboard the photographed hand, taking a seat atop it.

Others at Bray would attempt to copy or incorporate Fleischer’s successful concepts into their own films. Though inconsistently utilized in the series, Earl Hurd’s semi-realistic “Bobby Bumps” series was known to include episodes where Bobby is obviously aware of his cartoon existence. Perhaps the most well-known example, in the most available of his films, appears in Bobby Bumps Puts a Beanery On the Bum (12/4/18). The film begins on a drawing pad, with no live-action footage seen – only the “hand” of an animator, rendered by photographic stills placed onto cels or cutouts amidst the animated elements. The animator’s pen begins drawing Bobby in a lazy recline upon the bare paper. Bobby is quite aware he is being drawn, as he sleepily raises one leg to allow the artist to draw in the back side of his limbs while it is raised. The animator writes in on-screen letters to give instruction to Bobby, including “Hat off” to allow the pen to black-in Bobby’s hair, and “Roll over”, allowing the hand to pour some ink on the seat of Bobby’s pants to blacken-in its backside. Rising, Bobby climbs aboard the photographed hand, taking a seat atop it.

“Get off my hand”, writes the animator’s pen. Bobby shakes his head in playful little-boy stubbornness. The animator’s hand shakes, then bucks Bobby out of position, flicking him back onto the drawing board. The pen draws in Bobby’s dog Fido, but Bobby has to remind the animator that he forgot to include Fido’s tail. Then, the pen draws in the background for today’s adventure, and splashes it with a little ink from a bottle to give it a bit of realistic shading. The main body of the film consists of standard animation, as Bobby takes on the job of assistant to a short-order cook, causing considerable chaos in the kitchen. One cartoony gag has Fido insulted by a passing cat, who calls him a “Cur” in dialog printed in a comic-strip balloon. Fido responds that he is going to make the cat eat those words, and, when the cat repeats the insult, Fido grabs its dialog-balloon, lifts it from the drawing pad to roll it up as a cylinder, then stuffs it down the cat’s throat. Only an intervening poke from the animator’s pen at Fido’s tail breaks up the squabble. At the end of the film, the cook pursues Bobby to discipline him for breaking a towering stack of dishes. Bobby and Fido exit the restaurant, and find themselves on a blank drawing sheet with no background penned-in. Bobby begins calling for help. The trusty animator’s hand reappears, drawing in a ladder for Bobby and Fido to climb. Then, using an eraser, the hand obliterates the lower portions of the ladder, removing the ladder from view of the cook, who peers all around his blank portion of background for some sign of Bobby. Bobby’s chunk of ladder does not observe the principles of gravity, remaining suspended in air high above as a safe haven for Bobby and Fido. The animator carries into the frame an open ink bottle, and for a moment, we expect Bobby and Fido to jump in, the same as Koko. Instead, Bobby takes hold of the bottle, and pours it out, letting it spill past the view of the frame. Below, the cook finds himself deluged in ink, which fills the frame, leaving only the whites of his eyes visible in an expression of “What happened?”, as the film ends.

“Get off my hand”, writes the animator’s pen. Bobby shakes his head in playful little-boy stubbornness. The animator’s hand shakes, then bucks Bobby out of position, flicking him back onto the drawing board. The pen draws in Bobby’s dog Fido, but Bobby has to remind the animator that he forgot to include Fido’s tail. Then, the pen draws in the background for today’s adventure, and splashes it with a little ink from a bottle to give it a bit of realistic shading. The main body of the film consists of standard animation, as Bobby takes on the job of assistant to a short-order cook, causing considerable chaos in the kitchen. One cartoony gag has Fido insulted by a passing cat, who calls him a “Cur” in dialog printed in a comic-strip balloon. Fido responds that he is going to make the cat eat those words, and, when the cat repeats the insult, Fido grabs its dialog-balloon, lifts it from the drawing pad to roll it up as a cylinder, then stuffs it down the cat’s throat. Only an intervening poke from the animator’s pen at Fido’s tail breaks up the squabble. At the end of the film, the cook pursues Bobby to discipline him for breaking a towering stack of dishes. Bobby and Fido exit the restaurant, and find themselves on a blank drawing sheet with no background penned-in. Bobby begins calling for help. The trusty animator’s hand reappears, drawing in a ladder for Bobby and Fido to climb. Then, using an eraser, the hand obliterates the lower portions of the ladder, removing the ladder from view of the cook, who peers all around his blank portion of background for some sign of Bobby. Bobby’s chunk of ladder does not observe the principles of gravity, remaining suspended in air high above as a safe haven for Bobby and Fido. The animator carries into the frame an open ink bottle, and for a moment, we expect Bobby and Fido to jump in, the same as Koko. Instead, Bobby takes hold of the bottle, and pours it out, letting it spill past the view of the frame. Below, the cook finds himself deluged in ink, which fills the frame, leaving only the whites of his eyes visible in an expression of “What happened?”, as the film ends.

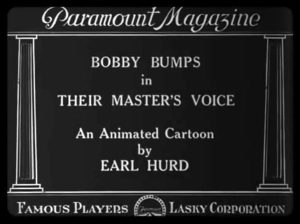

Another later example, produced after Hurd left Bray studios, is Their Master’s Voice (Paramount Magazine, 11/9/19), part of a three-subject reel that also included the first appearance of Felix the Cat. Bobby is again aware of his screen career, as he appears in a special opening to the reel, puncturing a hole in a blank screen framed by the banner title for the Paramount series, and being handed out the hole by unseen hands what looks like a carpet roll. Fido emerges from inside the carpet, and the two of them unroll the fabric against the camera lens, on which is printed the main title for the present episode. The film irises in to a desk in Hurd’s animation studio, with an ink bottle in the foreground, an alarm clock, and a towering candlestick telephone. The clock alarm rings, arousing the tiny Bobby and Fido from the inkwell. But Hurd is nowhere to be found. Bobby wonders at the “boss”’s absence during work hours, and decides to phone him to see what’s up. As the telephone is so tall compared to the characters’ diminutive size, Bobby climbs up to the mouthpiece, while Fido listens below at the receiver, and the two attempt to communicate to each other their respective parts of the conversation. Hurd this time appears in live action shots, though not together with Bobby (at least not in what footage survives, as it seems likely in view of the film’s abrupt ending that we are only viewing a surviving fragment with the ending missing). Hurd, at first unable to hear Bobby, utters a flustered “Hello?”, which blasts out of the phone’s earpiece, sending Fido rolling. Bobby finally speaks up on his end, and Hurd instructs them to bring the ink and pen, as they’ll be working at his home today. Fido dances with glee that “We’re invited out”, but receives a rude coda, as Hurd exhales a large puff of smoke from a cigar, delivering a smoke-cloud through the earpiece of the phone into Fido’s face. Fido retaliates, running over to the boss’s real-life pipe on the desk, inhaling deeply, then blowing his own smoke cloud back through the earpiece into Hurd’s face. Bobby and Fido then begin packing the art supplies into a cigar box. Fido spots a spider, and takes a whack at it with a pen, missing and knocking Bobby into the box. The film, as mentioned, thus ends abruptly – just when it was getting good.

Another later example, produced after Hurd left Bray studios, is Their Master’s Voice (Paramount Magazine, 11/9/19), part of a three-subject reel that also included the first appearance of Felix the Cat. Bobby is again aware of his screen career, as he appears in a special opening to the reel, puncturing a hole in a blank screen framed by the banner title for the Paramount series, and being handed out the hole by unseen hands what looks like a carpet roll. Fido emerges from inside the carpet, and the two of them unroll the fabric against the camera lens, on which is printed the main title for the present episode. The film irises in to a desk in Hurd’s animation studio, with an ink bottle in the foreground, an alarm clock, and a towering candlestick telephone. The clock alarm rings, arousing the tiny Bobby and Fido from the inkwell. But Hurd is nowhere to be found. Bobby wonders at the “boss”’s absence during work hours, and decides to phone him to see what’s up. As the telephone is so tall compared to the characters’ diminutive size, Bobby climbs up to the mouthpiece, while Fido listens below at the receiver, and the two attempt to communicate to each other their respective parts of the conversation. Hurd this time appears in live action shots, though not together with Bobby (at least not in what footage survives, as it seems likely in view of the film’s abrupt ending that we are only viewing a surviving fragment with the ending missing). Hurd, at first unable to hear Bobby, utters a flustered “Hello?”, which blasts out of the phone’s earpiece, sending Fido rolling. Bobby finally speaks up on his end, and Hurd instructs them to bring the ink and pen, as they’ll be working at his home today. Fido dances with glee that “We’re invited out”, but receives a rude coda, as Hurd exhales a large puff of smoke from a cigar, delivering a smoke-cloud through the earpiece of the phone into Fido’s face. Fido retaliates, running over to the boss’s real-life pipe on the desk, inhaling deeply, then blowing his own smoke cloud back through the earpiece into Hurd’s face. Bobby and Fido then begin packing the art supplies into a cigar box. Fido spots a spider, and takes a whack at it with a pen, missing and knocking Bobby into the box. The film, as mentioned, thus ends abruptly – just when it was getting good.

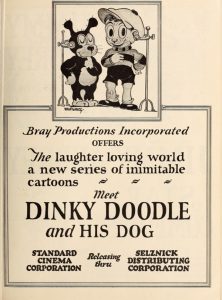

Walter Lantz would join Bray’s ranks, as the successor-apparent after the departure of Fleischer. He too wanted to capitalize on Fleischer’s “inkwell” universe. First producing some revival films of Colonel Heeza Liar, there were occasions when the braggadocio Colonel would exhibit awareness of his medium, boasting of his exploits to live folk on the other side of the paper world. But Lantz’s most memorable interplay with the animated world was in the creation of the characters Dinky Doodles and Weakheart. The characters could hardly be called original – basically, another boy and his dog, the same as Bobby and Fido. However, no semblance of realism was attempted in the design of these characters – they were strictly from Toonsville. Nor did they play in realistic settings, more likely to turn up in stylized worlds with fantasy themes. Dinky was also not at all well-behaved, more of a wise-guy and triblemaker, perhaps akin to Columbia’s later character Scrappy in his early days, multiplied by a few mathematical powers. Lantz’s biggest breakthrough, however, was a photographic technique by which he sought to eliminate process-shot photography, and allegedly sync-up animated action to live-action more precisely, by filming live sequences in normal manner, but having the film enlarged frame-by-frame into photographic stills of drawing-paper size, to serve as backgrounds from which cels would be produced by overlay to place the characters or visual effects precisely in the spots where they were intended to interact with the live-action actors and props. The technique was far from perfect, often resulting in pronounced shutter flicker visible in the still photographs, and the animation crude compared to Fleischer standards – but at times it attained interesting results. Few Dinky episodes survive intact, but there are isolated clips that have surfaced from time to time in documentaries on Lantz, showing the animator himself driving in an explosive toon flivver, and dueling within the studio with a menacing, sword-wielding wolf – perhaps a few concepts that would have kept Fleischer up nights trying to conceive how to produce in his own processes.

By default, due to the severe lack of examples available on the internet, I present as a sample The House That Dinky Built (3/20/25). (Advance apologies for poor print quality, and lettering superimposed upon the screen.) A doll house provides the setting causing Donky and Weakheart to leave their 2-D world, which they and Lantz are attempting to renovate on speculation as Dinky’s new residence. Lantz and Dinky attempt to clean up with broom and garden hose, but end up in a playful duel of hitting each other with blasts of water. Provisions are loaded into the house, including sacks of malt, which Lantz suggests will be handy for making beer. However, a large mouse intercepts the tossing of the sacks into the window, devouring them whole, and becoming severely intoxicated in the process. When the mouse becomes aggressive, Dinky, Weakheart, and the rodent run up Lantz’s pantleg. Lantz goes through fits as the three send him into a ticklish frenzy inside his overalls. Dinky and Weakheart leap out, and into a 2-D world in a cartoon illustration on the wall, riding a cow and meeting the milkmaid who is its mistress. Dinky is immediately smitten with the girl, and Weakheart has a rooster crow for the parson, informing the bird that he’s got a couple of customers for the clergyman. A marriage is performed, and action exits the wall painting. Dinky introduces the girl to Lantz – “Meet my ball and chain.” Lantz asks if he can kiss the bride, and, without intertitle, Dinky disapprovingly mouths words which appear to be, “Heck, no.” Dinky takes the bride inside the new home, not observing the standard ritual of carrying her across the threshold. The two leave Weakheart outside, then pull down all the window curtains. Suddenly, the doll house erupts with shudders, vibrations, and spins around like a top. Lantz and Weakheart exchange perplexed looks, only imagining what might be going on in there. Lantz finally braves peering in, to observe Dinky being repeatedly bashed over the head by the wife’s rolling pin. When Lantz tries to interject a word to break up the brutal battle, the couple join forces as a united front, replying “Mind your own business. This is our fight”. The bride throws her rolling pin straight at the camera, and the scene cuts to the live Lantz, being beaned solidly, spinning, and seeing stars, for the fade out.

By default, due to the severe lack of examples available on the internet, I present as a sample The House That Dinky Built (3/20/25). (Advance apologies for poor print quality, and lettering superimposed upon the screen.) A doll house provides the setting causing Donky and Weakheart to leave their 2-D world, which they and Lantz are attempting to renovate on speculation as Dinky’s new residence. Lantz and Dinky attempt to clean up with broom and garden hose, but end up in a playful duel of hitting each other with blasts of water. Provisions are loaded into the house, including sacks of malt, which Lantz suggests will be handy for making beer. However, a large mouse intercepts the tossing of the sacks into the window, devouring them whole, and becoming severely intoxicated in the process. When the mouse becomes aggressive, Dinky, Weakheart, and the rodent run up Lantz’s pantleg. Lantz goes through fits as the three send him into a ticklish frenzy inside his overalls. Dinky and Weakheart leap out, and into a 2-D world in a cartoon illustration on the wall, riding a cow and meeting the milkmaid who is its mistress. Dinky is immediately smitten with the girl, and Weakheart has a rooster crow for the parson, informing the bird that he’s got a couple of customers for the clergyman. A marriage is performed, and action exits the wall painting. Dinky introduces the girl to Lantz – “Meet my ball and chain.” Lantz asks if he can kiss the bride, and, without intertitle, Dinky disapprovingly mouths words which appear to be, “Heck, no.” Dinky takes the bride inside the new home, not observing the standard ritual of carrying her across the threshold. The two leave Weakheart outside, then pull down all the window curtains. Suddenly, the doll house erupts with shudders, vibrations, and spins around like a top. Lantz and Weakheart exchange perplexed looks, only imagining what might be going on in there. Lantz finally braves peering in, to observe Dinky being repeatedly bashed over the head by the wife’s rolling pin. When Lantz tries to interject a word to break up the brutal battle, the couple join forces as a united front, replying “Mind your own business. This is our fight”. The bride throws her rolling pin straight at the camera, and the scene cuts to the live Lantz, being beaned solidly, spinning, and seeing stars, for the fade out.

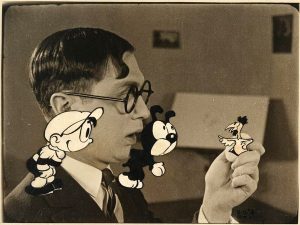

Walt Disney was a mere up-and-comer when Max’s concepts were being firmly established. He was carefully aware of Max’s creations, and in fact, one might say that his original Newman Laugh-o-Grams (of which very little survives) were like a sort of copycat of Fleischer’s “Inklings” with less creativity and an emphasis on local politics. But Walt eventually saw an idea from Fleischer’s “Inkwell” series. Why not reverse things, and have the live-action character be the star by joining into the cartoon? Thus began several years of production of the “Alice” Comedies. Oddly, once the idea was established by a pilot, Walt abandoned the concept of any interplay between animator and drawing board, merely commencing each episode with Alice already the permanent resident of the cartoon world, expressing no on-screen cognizance that she is in an odd setting or not following real-life rules of existence. Thus, only Alice’s Wonderland (10/16/23) qualifies for inclusion within the present trail. This film was truly a pilot only, never released theatrically, but only shown in private screenings to draw the interest of distributors – so the viewing public was never actually let in on the method by which its star joined the animated world.

Walt Disney was a mere up-and-comer when Max’s concepts were being firmly established. He was carefully aware of Max’s creations, and in fact, one might say that his original Newman Laugh-o-Grams (of which very little survives) were like a sort of copycat of Fleischer’s “Inklings” with less creativity and an emphasis on local politics. But Walt eventually saw an idea from Fleischer’s “Inkwell” series. Why not reverse things, and have the live-action character be the star by joining into the cartoon? Thus began several years of production of the “Alice” Comedies. Oddly, once the idea was established by a pilot, Walt abandoned the concept of any interplay between animator and drawing board, merely commencing each episode with Alice already the permanent resident of the cartoon world, expressing no on-screen cognizance that she is in an odd setting or not following real-life rules of existence. Thus, only Alice’s Wonderland (10/16/23) qualifies for inclusion within the present trail. This film was truly a pilot only, never released theatrically, but only shown in private screenings to draw the interest of distributors – so the viewing public was never actually let in on the method by which its star joined the animated world.

An illustrious trio assisted Disney in ths effort including Ub (existing prints credit him as “Ubbe”) Iwerks, Hugh Harman, and Rudolf Ising. Young Virginia Davia (Alice) pays her first visit to a cartoon studio. She finds Walt seated at a drawing board, putting finishing touches on an outline of a doghouse. Knocking on Walt’s door, Alice asks if she can watch Walt draw some funnies. Walt seats Alice in his chair, and they both watch his drawing, which suddenly springs to life, the doghouse vibrating with the shock-waves of a battle within. A little dog is tossed out the door again and again, but rejoins the fray, only to finally be deposited outside by the victor – a feline, who would become Julius the Cat (a close look-alike to Felix). Walt shows that things in an animator’s studio don’t always remain on the drawing board, showing off another desk, on which another pair of cats dance, while three more provide music with miniature instruments. At another drawing pad (with several other animators shown working behind the desk in the background, several of them likely the principals named in the credits), a cartoon mouse (long distanced from Mickey) duels with his tail to chase a live cat off the desk. Julius and the dog square off again, this time with boxing gloves, as the animation crew crowds around the drawing board to watch the main event, one of the animators keeping time by clanging the side of a glass vase like a bell between rounds. The dog finally stands victorious, with Julius canvas-backed on the floor, as the animators cheer.

An illustrious trio assisted Disney in ths effort including Ub (existing prints credit him as “Ubbe”) Iwerks, Hugh Harman, and Rudolf Ising. Young Virginia Davia (Alice) pays her first visit to a cartoon studio. She finds Walt seated at a drawing board, putting finishing touches on an outline of a doghouse. Knocking on Walt’s door, Alice asks if she can watch Walt draw some funnies. Walt seats Alice in his chair, and they both watch his drawing, which suddenly springs to life, the doghouse vibrating with the shock-waves of a battle within. A little dog is tossed out the door again and again, but rejoins the fray, only to finally be deposited outside by the victor – a feline, who would become Julius the Cat (a close look-alike to Felix). Walt shows that things in an animator’s studio don’t always remain on the drawing board, showing off another desk, on which another pair of cats dance, while three more provide music with miniature instruments. At another drawing pad (with several other animators shown working behind the desk in the background, several of them likely the principals named in the credits), a cartoon mouse (long distanced from Mickey) duels with his tail to chase a live cat off the desk. Julius and the dog square off again, this time with boxing gloves, as the animation crew crowds around the drawing board to watch the main event, one of the animators keeping time by clanging the side of a glass vase like a bell between rounds. The dog finally stands victorious, with Julius canvas-backed on the floor, as the animators cheer.

That night, Alice is tucked into bed by her Mom in her own room, and begins to dream. It feels as though there is a shot or two missing here, as there is no dissolve or clean transition into the animated world, nor immediate explanation that Alice is aboard the cartoon train which we suddenly see, hopping wide chasms where there is no bridge, and rising and falling while tracing a string of mountain peaks, performing a loop-de-loop for no apparent reason between two hills. A band and reception committee of cartoon animals awaits at the Cartoonland station, holding banners reading “Welcome, Alice.” Some insertions of the live Alice in shots are performed simply, such as Alice appearing in a totally live shot emerging from a full-sized flat mock-up of the side of one of the railway cars. Others are sophisticated, such as a shot where Alice is greeted by four city-delegate dogs in top hats, with Alice walking across a fully-rendered cartoon background. Still, most shots are created in what would become Walt’s standard process – providing an area of blank screen or a blank segment of the frame, in which the footage of Alice could be neatly superimposed without risk of overlapping images. A parade is held in Alice’s honor, and Alice performs a dance to entertain the crowd. However, a quartet of rather round, overweight lions (what have they been gorging themselves on?) escapes from the local zoo by chewing right through the cage’s iron bars. Julius warns of the lions’ approach, and the film climaxes in an extended chase between Alice and the kings of beasts. One lion removes its dentures to sharpen them with a file. One of the better process shots has Alice’s feet passing behind animation of jumping jack-rabbits, outracing them in her attempt to escape the pursuing beasts. The processing lab has trouble with a shot in which Alice is to duck into the darkened hole of a hollow tree, some double exposure of Alice’s image visible over the tree background – but does better shortly afterwards in a shot where Alice similarly ducks into a cave. Finally, Alice is cornered at a cliff’s edge, and jumps, falling, falling, falling, much as the literary Alice did down the rabbit hole. Original issues of the short to home video abruptly end at this shot, giving indication that the last scenes of the short have been lost to time. However, someone has neatly repeated a couple of shots from the live scenes of Alice’s being put to bed by her Mom, run in reverse, with the new caption, “Alice, Alice, wake up”, to fake an ending, also superimposing an iris out, at least giving the film a semblance of closure. Should anyone have information on any content, if different, of the real original closing shots, they are welcomed to contribute.

That night, Alice is tucked into bed by her Mom in her own room, and begins to dream. It feels as though there is a shot or two missing here, as there is no dissolve or clean transition into the animated world, nor immediate explanation that Alice is aboard the cartoon train which we suddenly see, hopping wide chasms where there is no bridge, and rising and falling while tracing a string of mountain peaks, performing a loop-de-loop for no apparent reason between two hills. A band and reception committee of cartoon animals awaits at the Cartoonland station, holding banners reading “Welcome, Alice.” Some insertions of the live Alice in shots are performed simply, such as Alice appearing in a totally live shot emerging from a full-sized flat mock-up of the side of one of the railway cars. Others are sophisticated, such as a shot where Alice is greeted by four city-delegate dogs in top hats, with Alice walking across a fully-rendered cartoon background. Still, most shots are created in what would become Walt’s standard process – providing an area of blank screen or a blank segment of the frame, in which the footage of Alice could be neatly superimposed without risk of overlapping images. A parade is held in Alice’s honor, and Alice performs a dance to entertain the crowd. However, a quartet of rather round, overweight lions (what have they been gorging themselves on?) escapes from the local zoo by chewing right through the cage’s iron bars. Julius warns of the lions’ approach, and the film climaxes in an extended chase between Alice and the kings of beasts. One lion removes its dentures to sharpen them with a file. One of the better process shots has Alice’s feet passing behind animation of jumping jack-rabbits, outracing them in her attempt to escape the pursuing beasts. The processing lab has trouble with a shot in which Alice is to duck into the darkened hole of a hollow tree, some double exposure of Alice’s image visible over the tree background – but does better shortly afterwards in a shot where Alice similarly ducks into a cave. Finally, Alice is cornered at a cliff’s edge, and jumps, falling, falling, falling, much as the literary Alice did down the rabbit hole. Original issues of the short to home video abruptly end at this shot, giving indication that the last scenes of the short have been lost to time. However, someone has neatly repeated a couple of shots from the live scenes of Alice’s being put to bed by her Mom, run in reverse, with the new caption, “Alice, Alice, wake up”, to fake an ending, also superimposing an iris out, at least giving the film a semblance of closure. Should anyone have information on any content, if different, of the real original closing shots, they are welcomed to contribute.

NEXT WEEK: A few more silent escapades, and then into sound.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Very interesting subject for an Animation Trail! Offhand I can think of some cartoon classics that are bound to be covered here in the coming weeks, but I’m looking forward to discovering some rare and little-known obscurities in the genre. I especially enjoyed seeing the youthful Walt Disney, Ub Iwerks, Hugh Harman and Rudy Ising captured on film at the onset of their distinguished careers in animation and obviously having the time of their lives.

The men in the live-action opening scene of “Little Nemo” can be identified. At the table in the foreground, J. Stuart Blackton is seated at the far left, with Winsor McCay sitting opposite him on the far right. To Blackton’s left is actor and director Maurice Costello. The heavyset man on McCay’s right is silent film comedian John Bunny; Bunny was a big star in his day, but nearly all of his films have been lost, and this scene from “Little Nemo” is one of his few surviving film performances.

At the table in the rear, the man on the left is George McManus, creator of the long-running comic strip “Bringing Up Father”. On the right is publisher Eugene V. Brewster, conspicuously holding up a copy of The Motion Picture Story Magazine, founded by Blackton in 1911; it was the first film magazine geared toward the general public rather than film distributors and exhibitors. The magazine changed its name to The Motion Picture Magazine in 1914 and ultimately ceased publication in 1977. So the notion of motion picture studios using their films to promote their other media properties is clearly something that’s been going on since the very beginning.

Charles, This is an excellent idea for a series of posts. Thanks for the effort you’ve put into this. There’s an awful lot of work even just finding the cartoons, let alone writing about them.

I still have a soft spot for Van Beuren’s ‘Making ‘Em Move,’ partly due to its casualness regarding story, but you’ll get there.

Your most interesting topic for a series of posts yet, Charles. Really would like to see where this goes.

Will Roger Rabbit make it? Or is that a movie about cartoons?

This is a clever and novel topic for an animation trail, Charles!

I look forward to seeing what examples you’re able to produce within the mid-1930s period when the Disney Silly Symphonies, which almost never broke the fourth wall, were the gold standard- and often copied to the letter by rival studios.

This is a great topic! It’ll be fun to see how the style of these evolve over time. At first of course it’s very literal, but there’s a lot of ground between that and the most famous examples some decades later.

Given his importance in the early history of the medium, J. R. Bray’s first animated film, “The Artist’s Dreams” (12/6/13) deserves to be mentioned here.

The artist (Bray) has just completed a drawing of a domestic scene: a dachshund wearing a sweater is lying on the floor next to a large wardrobe bureau, on top of which is a dish containing one sausage. The artist invites a bearded critic in to view the drawing and give his opinion of it. “No action in the dog — too stiff — awful!” the critic remarks in an intertitle before departing, whereupon the artist, too, steps out of the scene. Now we see the dog in the picture begin to stir and come to life. “Say, did you hear what that fellow said about me?” asks the dog. “No action, hey? Just wait!”

The dog notices the sausage and thinks up a way to reach it. He pulls out the drawers of the wardrobe to create a staircase, climbs it to the top, grabs the sausage, takes it back down and eats it before resuming his previous position on the floor. When the artist returns, he is baffled to find that the sausage he had drawn earlier is no longer in the picture; so he draws three more sausages in its place. The dachshund then hides in the wardrobe’s closet while his creator’s back is turned; and when the artist looks at the drawing a moment later, he notices that the sausages are still there, but the dog is gone! Now he runs off to tell his friend the critic, “There’s something queer going on in my studio!”