No, this article’s not all about Dreamworks or Pixar. It’s summer – so I figured we need something appropriate for the season. Summer means picnics. And picnics inevitably mean – ants!

With the exception of the “True Life Adventures” and modern day documentaries utilizing advanced magnifying camera techniques, animation has almost since its dawning been the exclusive medium for the insect world to hit the silver screen. Magnification and point-of-view angles have never posed major obstacles to a skilled man with a pencil and a good imagination – though they have undoubtedly daunted many a nature photographer. Furthermore, an animator can endow such critters with something a live-action director cannot – screen personality. It’s hard to make a star out of one crawly insect in a swarm – unless you can magically embellish the creature with semi-human qualities that make him or her stand out in a crowd.

With the exception of the “True Life Adventures” and modern day documentaries utilizing advanced magnifying camera techniques, animation has almost since its dawning been the exclusive medium for the insect world to hit the silver screen. Magnification and point-of-view angles have never posed major obstacles to a skilled man with a pencil and a good imagination – though they have undoubtedly daunted many a nature photographer. Furthermore, an animator can endow such critters with something a live-action director cannot – screen personality. It’s hard to make a star out of one crawly insect in a swarm – unless you can magically embellish the creature with semi-human qualities that make him or her stand out in a crowd.

The animation industry did, however, have a tendency to take these principles too far. In many, many instances, insects were nearly deprived altogether of their natural attributes, in favor of coming up with characters that were unbearably “cute” and decidedly over-humanized – rendering them into so many little identical “Mickey Mice”. Consequently, predominant species utilized in most cartoons tend to be either flies or beetles – with rounder bodies so the animators can make life easy for themselves by drawing circles or ovals – and with not so many negative natural qualities that audiences will be scared of or at least take a disliking to them. Many films hardly attempt to identify a species at all, but instead categorize their casts generically (such as Disney’s Bugs in Love (Silly Symphony, 1932)).

But a few species managed to stand out, and retain something of what nature gave them, even in the cartoon world. Sometimes playing these characters more realistically would have the downside of reverting to “swarm mentality”, where they would only act in groups rather than as individuals. Even so, a few hearty fellows would always manage to rise above the crowd. But often, where natural traits were retained, some species would endure some of Hollywood’s most extreme instances of “type casting” – developing whole sub-genres of films that would share commonalities of character traits and storylines from studio to studio – hence, another opportunity to explore an animation trail.

The ant is not a solitary creature. Its whole life in the real world seems to be spent either following – or being followed – or both, by others of its kind. Thus, it became one of the most commonly “swarmed” types of characters in the animated world, setting its niche for treatment by the various studio systems.

Where did the ant first rise to star prominence? Surprisingly, at almost the inception of cinema. Though it’s a lost film, and no source seems to confirm if it was live, puppet, or stop motion, George Melies set before his audiences a first retelling of the ancient fable “The Ants and the Grasshopper”in 1897! This timeless story would continue to have influence on filmmakers for decades, and was among the earliest of Paul Terry’s “Aesop’s Fables” cartoon series in 1921! But Terry may have also been creating new storylines about the same time, as his release calendar for the same year also included the title, The Fly and the Ant (1921). Later in his silent series, another notable title appears: Ant Life As It Isn’t (8/7/27). None of these films can be found on the internet, nor are any plot summaries available – it’s unknown if they’re lost.

For a long stretch thereafter, there seems to be little verifiable evidence of the involvement of ants in American cinema. It may be that the early animators were somewhat intimidated by the ant’s segmented physique, and at this time start favoring the more rounded insects referenced above to meet their daily footage quotas.

“Father Noah’s Ark” (Disney/UA, Silly Symphony, 4/8/33 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.), perhaps deserves an honorable mention for one particular scene. While Noah takes inventory with a checklist at a main gangplank of the ark for all the traditional animal species, Mrs. Noah is seen presiding over a much smaller gangplank, where she takes inventory of the boarding of all the world’s insects! Presumably, there must be at least two ants in there somewhere.

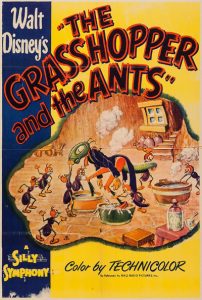

Disney’s “The Grasshopper and the Ants” (United Artists, Silly Symphony, 2/10/34 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.) is by far the ultimate version of this story, and a bona fide classic – in my humble opinion my second favorite of the entire series, though it did not win an academy award, or even a nomination. The storytelling is unpretentious and straightforward – but is peppered with humor, moments of spectacle, and trademark Disney sincerity. The Grasshopper (voiced by Pinto Colvig, in the role that would truly rank him as a star, and cement a facet in fleshing out the personality of his then-developing Goofy character) is a totally happy-go-lucky fellow, in love with life and his old violin, which he bows away at all day long, while taking intermittent stops to munch on a leaf or two, or drink dew from the cups of bluebells. In contrast, he spies an ant colony headquartered in the trunk of a large tree, who are the spirit of industriousness in gathering a storehouse of food. The ants are depicted with round toony “bug” faces and only four limbs, but retain segmented bodies, and even signs of jaggedness behind their forearms and legs, making for an interesting 30’s mix of both realistic and “cute” appeal. While the ants saw off slices of carrots for convenient storage, pry off kernels of corn from a cob, and engage in other mass food gathering, a lone ant struggles with a small cart filled with three cherries, but stuck in a mud hole. His tow rope breaks, landing him face-first in mud. The grasshopper bursts into laughter, and decides to set the little guy straight with his own philosophy. In the delightful song “The World Owes Me a Living” (which would become the often-used unofficial theme song for Goofy beginning with On Ice (1935)), the grasshopper observes that the Lord provides food on every tree, and that he sees no reason to worry and work. He strikes up a tune on his fiddle, and wins the ant over to performing a mock-Russian dance. However, passing nearby is the royal procession of the Ant Queen (wearing full crown and gown). She spies the dancing at its height, and stops the procession to investigate. When the dancing ant discovers the Queen is behind him, he feigns a hurried bow in apology, races back to his cart, and lifts it out of the mud bodily, racing away with the cart upon his shoulders. The Queen cautions the grasshopper that “You’ll change that tune when winter comes and the ground is covered with snow.” The grasshopper ignores her, observing that winter is a long way off – but the Queen likewise ignores his invitation to join in the dance (though another ant of her royal procession is obviously sorely tempted by the grasshopper’s words).

Disney’s “The Grasshopper and the Ants” (United Artists, Silly Symphony, 2/10/34 – Wilfred Jackson, dir.) is by far the ultimate version of this story, and a bona fide classic – in my humble opinion my second favorite of the entire series, though it did not win an academy award, or even a nomination. The storytelling is unpretentious and straightforward – but is peppered with humor, moments of spectacle, and trademark Disney sincerity. The Grasshopper (voiced by Pinto Colvig, in the role that would truly rank him as a star, and cement a facet in fleshing out the personality of his then-developing Goofy character) is a totally happy-go-lucky fellow, in love with life and his old violin, which he bows away at all day long, while taking intermittent stops to munch on a leaf or two, or drink dew from the cups of bluebells. In contrast, he spies an ant colony headquartered in the trunk of a large tree, who are the spirit of industriousness in gathering a storehouse of food. The ants are depicted with round toony “bug” faces and only four limbs, but retain segmented bodies, and even signs of jaggedness behind their forearms and legs, making for an interesting 30’s mix of both realistic and “cute” appeal. While the ants saw off slices of carrots for convenient storage, pry off kernels of corn from a cob, and engage in other mass food gathering, a lone ant struggles with a small cart filled with three cherries, but stuck in a mud hole. His tow rope breaks, landing him face-first in mud. The grasshopper bursts into laughter, and decides to set the little guy straight with his own philosophy. In the delightful song “The World Owes Me a Living” (which would become the often-used unofficial theme song for Goofy beginning with On Ice (1935)), the grasshopper observes that the Lord provides food on every tree, and that he sees no reason to worry and work. He strikes up a tune on his fiddle, and wins the ant over to performing a mock-Russian dance. However, passing nearby is the royal procession of the Ant Queen (wearing full crown and gown). She spies the dancing at its height, and stops the procession to investigate. When the dancing ant discovers the Queen is behind him, he feigns a hurried bow in apology, races back to his cart, and lifts it out of the mud bodily, racing away with the cart upon his shoulders. The Queen cautions the grasshopper that “You’ll change that tune when winter comes and the ground is covered with snow.” The grasshopper ignores her, observing that winter is a long way off – but the Queen likewise ignores his invitation to join in the dance (though another ant of her royal procession is obviously sorely tempted by the grasshopper’s words).

The grasshopper proceeds through a montage of changing backgrounds, illustrating the passage of summer, leaves beginning to fall, and the first gusts of winter wind blowing away foliage from the countryside. In a flurry of activity, the ants store up the last food they can find and disappear into their tree, bolting the door against the wind. We phase-dissolve to a new shot of the same tree, deep in a blanket of snow. The grasshopper is now revealed in a tragically different mood – trudging along the snow covered paths, looking up at tree limbs now bare of any sustenance, and tightening his belt. In a scene of well-timed dramatic effect and pathos, the grasshopper spies one large brown dried-up leaf still clinging to a twig. He’s been so long without food that his mouth waters at even this depressing sight – “Food. FOOD!” he cries. Steeling himself for the extra effort, he trudges toward this last hope – but just as it seems within his grasp, a sudden gust of wind hits the leaf, ripping it from the twig, and sending it floating with the wind current over the horizon, while the grasshopper looks on with utter helplessness. This is the sort of reaching-the-audience (particularly in the wake of a depression where many had known the pangs of hunger) that was establishing Disney’s reputation as a master of storytelling. The grasshopper proceeds aimlessly, but in phases changes from his usual yellow-green complexion to a deep shade of solid blue, and collapses. But a possible ray of salvation reveals itself, as he spies ahead that he has returned to the tree of the ants, where an inviting yellow glow is seen through the window of the front door.

The grasshopper proceeds through a montage of changing backgrounds, illustrating the passage of summer, leaves beginning to fall, and the first gusts of winter wind blowing away foliage from the countryside. In a flurry of activity, the ants store up the last food they can find and disappear into their tree, bolting the door against the wind. We phase-dissolve to a new shot of the same tree, deep in a blanket of snow. The grasshopper is now revealed in a tragically different mood – trudging along the snow covered paths, looking up at tree limbs now bare of any sustenance, and tightening his belt. In a scene of well-timed dramatic effect and pathos, the grasshopper spies one large brown dried-up leaf still clinging to a twig. He’s been so long without food that his mouth waters at even this depressing sight – “Food. FOOD!” he cries. Steeling himself for the extra effort, he trudges toward this last hope – but just as it seems within his grasp, a sudden gust of wind hits the leaf, ripping it from the twig, and sending it floating with the wind current over the horizon, while the grasshopper looks on with utter helplessness. This is the sort of reaching-the-audience (particularly in the wake of a depression where many had known the pangs of hunger) that was establishing Disney’s reputation as a master of storytelling. The grasshopper proceeds aimlessly, but in phases changes from his usual yellow-green complexion to a deep shade of solid blue, and collapses. But a possible ray of salvation reveals itself, as he spies ahead that he has returned to the tree of the ants, where an inviting yellow glow is seen through the window of the front door.

Mustering up his last strength, the grasshopper uses his fiddle almost as an oar to draw himself through the snow to the ants’ door, Peering in the window, he sees one of those massive group shots that only Disney could manage, of the entire colony enjoying a twelve-course banquet of food and drink. As his strength ebbs, the grasshopper manages a feeble knock on the door, then passes out. Numerous ants discover him, and together lift him, carrying the miserable creature inside. Bundling him with blankets and placing his feet and rear abdomen in respective pails of hot water, the ants administer him several spoons full of warm “Ant-Ti Cold Syrup”, gradually returning the yellow-green to his cheeks. But the Queen notices the doings, and approaches the grasshopper with an icy stern expression. Upon seeing her, the grasshopper almost appears to shrink, chagrined at remembering his last words to her. He is humbly reduced to begging for her forgiveness. “Oh, madame Queen. Wisest of ants. Don’t throw me out! Please give me a chance!” The Queen makes her message clear, and sternly states, “With ants, just those who work may stay! So take your fiddle…” She hands the instrument back to the grasshopper, who presumes all is lost, and hopelessly braces to face the cold again. But the Queen, to everyone’s surprise, turns the tables, and comes up with the perfect solution to the problem – with a smile, she completes her sentence: “…and play!” The grasshopper finally finds a living – as a court musician. Rewriting his signature tune, the grasshopper admits, “I’ve been a fool a whole year long, but now I’m singing a different song. Your were right. I was wrong!”, while the ants happily dance to the entertainment.

This vintage masterpiece has unfortunately not been one of the best preserved of Disney’s negatives. While an old copy (possibly from an IB Technicolor 16mm) exists with good colors and reasonable sharpness on the old VHS release “Storybook Classics” (if you’re lucky enough to find a copy not suffering from videotape image “flagging” – my copy is loaded with it), the current DVD master has several scenes where the respective camera negatives do not seem to properly align, resulting in images which are blurry or appear to have double-outlines of the characters. More jarring still was an attempt at striking a new print made back in the days of the “Ink and Paint Club” on the Disney Channel – where all the colors looked bleached, turning the grasshopper’s yellow-green into something closer resembling a poached egg. But the damage to this print was not limited to picture. As early as the mid-1940’s reissue of the cartoon by RKO (from which source all current prints of the film derive), a careful inspection of the “The End” card reveals a seemingly irreparable defect. Said “The End” card, as currently presented, is the shortest in duration of any Disney production of the year. Why? Listen to a current print carefully, and you will detect a break in the soundtrack element, occurring just before the last four notes of the closing fanfare. A total of six notes were in fact removed from the soundtrack for the reissue. We might presume that the negative break may not have been so catastrophic as to destroy all six notes, but, since such notes were played in a brief change to a minor chord, the preservation of any of them into the tune without the others would have revealed like the proverbial sore thumb that something was wrong – so Disney excised the whole musical phrase to attempt to keep a continuous melody line going. How do I know these things? I’m also a record collector. And it just so happens that “Grasshopper and the Ants” was chosen among some of the first film soundtracks to be committed to commercial records – on 78 RPM shellac in the mid 1930’s for HMV records in Great Britain and Bluebird Records (Victor’s budget label) in the U.S. This transfer was made only a few years after the film’s initial release – before the damage was done. Thus, only by way of these records is the remainder of the original musical performance preserved, uncut. I am fortunate enough to own both the HMV and Bluebird issues of this rare single (the Bluebird having a superior, non-gritty surface with less noise or crackle).

Oddly, no one to date has posted a transfer of this rare record on the internet, or even its one-of-a-kind six note passage. I thus present as a special treat a new reconstruction below utilizing the missing musical passage in its closing. (Yes, there’s a bit of drop-off in sound quality, and the original side’s dubbing even exhibits a slight degree of speed irregularity in the transfer from film. But it’s there, in what form we have it, at last.) As an added bonus, I’ve attempted to recreate the original United Artists 1934 opening and closing title cards. I may be criticized for my choice, as more popular inclination tends to believe that style of these titles mirrored other 1934 releases such as “The Wise Little Hen” and “The Big Bad Wolf”, in a faceted gray background. However, the chronology of releases for 1934 Silly Symphonies indicates two titles in the early part of the year for which no original titling has been found: “The Grasshopper and the Ants”, and “Funny Little Bunnies”. Previous 1933 releases utilized what I call the “rainbow prism” second title card, and always to me looked drop-dead gorgeous. As “Grasshopper” was the first 1934 release, and right at the junction between the two titling styles, I’d like to believe that it was possibly the last, or maybe even second-to-last, of the “rainbow” openings, and have recreated it in such style. I hope you enjoy.

Editor’s Note: As we should have suspected – the copyright police have disputed our upload of this video. Click Here to view on Google Drive. We are working to get an embed posted here as soon as we can. Thanks for your patience.

As a final an interesting tribute to this classic, a new series of instrumental recordings was prepared as background music for Disneyland’s “Toontown” attraction years ago, revisiting classic scores from Disney’s early past in reasonably high fidelity but with a good period mix of instrumentation closely resembling the original productions. “The Grasshopper and The Ants” from such park recordings has been posted on Youtube on the “Monorail Blue” channel (do not confuse with “The World Owes Me a Living”, which is a different recording entirely). The orchestra was either working from original score sheets or from some of the finest score transcribing I’ve ever seen accomplished, as the sound is nearly dead-on in comparison to the original track. I’m inclined, however, to believe they found original score sheets for this item – because the missing six notes from the ending passage are restored in close paraphrase to the original in this remake recording! Check it out for an interesting listen.

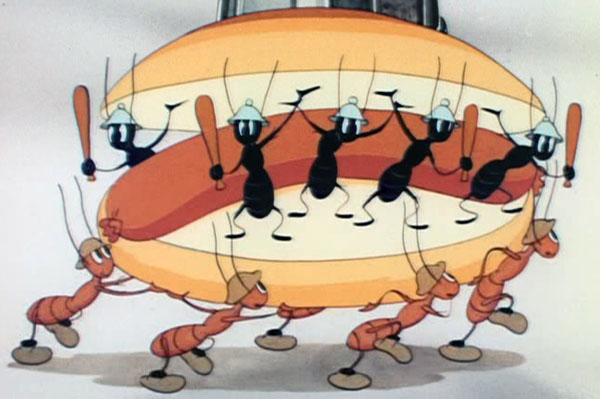

“Beach Picnic” (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 6/9/39 – Clyde Geronimi, dir.) – While a sizeable portion of this film is devoted to an excuse for a Technicolor remake of the “Pluto and flypaper” sequence from Playful Pluto (1934) (which film buffs may remember as the cartoon sequence featured by Preston Sturges in Paramount’s Sullivan’s Travels (1941)), some new sequences appear for Donald in his first encounter with our subject six-legged friends. While he somehow managed to hold a previous picnic without them in 1936’s The Orphan’s Picnic, Donald’s seaside banquet spread becomes target for tonight for a tribe of red ants, designed by the animators to resemble war-painted American Indians (perhaps not politically correct today – but mild compared to how Jack Hannah treated the same situation years later). A scout ant spies Donald’s beach blanket loaded with food, and gives an Indian war call to his fellow “braves”, who emerge en masse from nearby anthills (a scene which would be repeated verbatim with a different background in Hannah’s subsequent films to be discussed later in this article). A suitably Disney-elaborate, but unfortunately disappointingly short, sequence tracks the tribal raid on the picnic feast. A circle of braves dance an Indian war dance around the perimeter crust of a pie.

“Beach Picnic” (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 6/9/39 – Clyde Geronimi, dir.) – While a sizeable portion of this film is devoted to an excuse for a Technicolor remake of the “Pluto and flypaper” sequence from Playful Pluto (1934) (which film buffs may remember as the cartoon sequence featured by Preston Sturges in Paramount’s Sullivan’s Travels (1941)), some new sequences appear for Donald in his first encounter with our subject six-legged friends. While he somehow managed to hold a previous picnic without them in 1936’s The Orphan’s Picnic, Donald’s seaside banquet spread becomes target for tonight for a tribe of red ants, designed by the animators to resemble war-painted American Indians (perhaps not politically correct today – but mild compared to how Jack Hannah treated the same situation years later). A scout ant spies Donald’s beach blanket loaded with food, and gives an Indian war call to his fellow “braves”, who emerge en masse from nearby anthills (a scene which would be repeated verbatim with a different background in Hannah’s subsequent films to be discussed later in this article). A suitably Disney-elaborate, but unfortunately disappointingly short, sequence tracks the tribal raid on the picnic feast. A circle of braves dance an Indian war dance around the perimeter crust of a pie.

Six ants transport a slice of Swiss cheese positioned in each of its holes, then toss it on the beginnings of a multi-layer “Dagwood Bumstead” style sandwich, to which other ants add layers of ham, sausage, lettuce, mustard, eggs, tomato, and top bread slice – crowned by a toothpick and olive with pimiento. A complex scene shows the sandwich, along with other plates of goodies, being carted away by the tribe. A roast ham and its plate are rolled along on a bed of candy peppermint sticks. A string of sausages trails along, curling like a snake (another gag Hannah would lift for later treatment). Finally, the looming shadow of Donald, together with his quacking protests, is seen and heard, sending the ants scattering. Donald calls them thieves and robbers, and tries to dive at them – only to land face first in a pie. Now Donald resorts to spreading flypaper around, but one lone ant remains, and attempts to make off with a slice of strawberry cake twenty times his size. He chooses a poor direction, and comes nose-to-nose with Pluto, who begins sniffing after him. Donald, noticing their approach, tosses his last sheet of flypaper to land in their path. The ant just misses getting stuck, and instead ducks under the flypaper on the dry side. But Pluto walks his nose right into it – and thus the flypaper sequence that ends the cartoon, with some new added footage in which Pluto gets Donald all stuck up in the remainder of the flypaper. While the ants’ participation here was left unfairly short, the animation was memorable – and took a major role in shaping the way ants would be depicted for years to come – not only at Disney, but particularly at Warner Brothers.

“Ants In the Plants” (Fleischer/Paramount, Color Classics, 3/15/40 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Myron Waldman/ George Moreno, anim.) – Rumored to have been planned as something of a dress rehearsal for Fleischer’s upcoming feature, “Mr. Bug Goes To Town’ (1941) – except that, curiously, “Mr. Bug” seems to include no featured parts for ants! So the rumor may have a hole in it. At any rate, this episode returns to the ant’s home life instead of the picnic ground. Emphasis here is on “cute” rather than scientifically correct, with more four-legged ants and overuse by Waldman of “pie-slice” eye reflections a la early Mickey Mouse cartoons on nearly every character. We first see surface community life – a traffic cop using fireflies for “stop” and “go” lights, a snail moving van, and a “restaur-ant” specializing in politically incorrect pancakes (using “Ant Jermimah” pancake flour). A crew of “lumberjack” ants yells, “Timber”, only to reveal they’ve felled a daisy instead of a giant redwood. We next visit the royal tunnels. While resembling superficially the queen’s guard from Disney’s “Grasshopper and the Ants”, Fleischer’s view makes the guards considerably more militaristic – resembling the regiments of British soldiers guarding their queen concurrently in Europe, or possibly Russian cossacks. The Queen drills her troops with a lecture/pep talk regarding their vicious enemy, the ant-eater (the first and only known use of this species in cartoons until Depatie-Freleng in 1969 (to be discussed later in these articles)).

The creature is depicted with a bulky striped nose resembling a large elephant trunk, and has a mouth separate from his nose below this apparatus – so he can hardly be called anatomically correct. Departing even further from nature, he has no sticky tongue – but instead uses his “trunk” like a giant vacuum cleaner. The Queen (she and all ants speak in speeded-up “chipmunk” dialogue”) leads her guards in the rally song, “Make Him Yell ‘Uncle’”, with such tactics described as “Kick hm in the snoot!” Meanwhile, the real anteater skulks nearby. A scout ant spots him through a telescope, and plugs one of his antennae into a public address system (using trumpet-shaped lilies as megaphones) and talks into his other antenna as a mouthpiece. He shouts of “Danger. Public Enemy No. 1 at large. Do you want to be his next victim? Then SCRAM!” Various ants run for cover. One disappears into a small anthill, hanging a sign on a door thereof, reading “Anty Doesn’t Live Here Anymore” (play on words on a popular song, “Annie Doesn’t Live Here Anymore”, which Oswald Rabbit had virtually made a music video out of years earlier in Annie Moved Away (1934)).

The anteater passes the scout ant, barely missing him with his suction snoot. When he passes, the scout runs to an emergency control appearing to be a fire alarm box, reading “In case of ant-eater, break glass.” He does, and a squadron of the Queen’s guards pile out one by one through the little window. They advance – but chicken out and hide under their hats when they meet the anteater face to face. The scout ant is left by himself, and races for the safety of an anthill. But the anteater sticks his long snout down the tunnel like a snake, following the ant’s scent. The scout ant does a few whirls around a metal pole inside the tunnel and confuses the anteater, causing him to tie his nose in a knot around the pole. When he can’t pull his nose back, the scout ant grabs the end of it, and clamps it into the end of a metal pipe extending from one wall of the tunnel. Shouting in a direction above the pipe, the scout tells others to “Give him the works!” In a cutaway view, the camera proceeds upward to the next level, where the Queen and several guards load into the other end of the pipe, “Pepper! Salt! Mustard! Vinegar!” (Play on words of an old jump-rope rhyme Fleischer must have been particularly fond of, as he used it again and again in such films as “Swim ofr Sink” (1932) and “Betty Boop and the Little King” (1936). With a pump, the ants force this concoction up the anteater’s schnozzola. In great pain, the anteater’s snout turns glowing red, and the stripes on his snout morph into a spiraling barber-pole design. The anteater finally manages to yank his nose loose, and races to a nearby stream to douse the painful thing in water.

The queen appears atop the anthill, mounted on a snail, and calls a “Charge!” of her soldiers, accompanied by two small tanks using “caterpillar” treads. The anteater’s nose is out of commission and now in bandages – but that’s not going to stop him. He pulls out an eye-dropper, then aims it at the ants, sucking several of them into it, then squeezing them out into a bottle for safekeeping. The ants desperately battle, their best weapon being a corn cob on rollers under a magnifying glass, using the sun’s rays to pop off row after row of kernels into the anteater’s face. But the anteater succeeds in sucking up the whole colony, including the Queen, into the bottle. Or so it seems. As the anteater pours the bottle’s contents between two slices of bread for a sandwich, the scout ant has one more trick up his sleeve. Beeping radio signals in a morse code “S.O.S.” through his antennae, his signal is picked up at a pipe buried in the ground. A cap on the pipe flips open, revealing the letters, “Sewer-Side Squad”. Out come an elite reserve of guardsmen, armed with swords. They climb up and enter the anteater’s trousers, becoming “ants in the pants”. We hear the springy points of their swords making contact, and the anteater howls in pain, dropping the sandwich, and dragging himself down the road on his butt, yelling “Uncle! Uncle!” A cue for a reprise of the Queen’s song as a victory march, if ever I heard one. A clever and creative cartoon for its day. While its designs would not be reused by other studios, its themes and ideas of mass militarization, even more so than the Indian warriors of the brief “Beach Picnic” sequence, would seem to have a profound influence on other studio’s product to follow – especially our next episode, where the theatrical image of ants seems to crystalize indelibly into readily recognizable form.

“The Fighting 69½th” (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 1/18/41 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – It cannot be doubted that Freleng must have seen both of the preceding two episodes, and he and/or his writers were moved creatively by them. Taking an idea and running with it, Freleng adapts the use of military ants to a bigger and broader campaign – an operation mirroring the tactics of World War I. Cashing in on the recent box-office success of James Cagney in the studio’s high-budget historical tribute to a fighting Irish regiment from said war, “The Fighting 69th” (1940), Freleng merely adds a fraction to it, and concocts a tale of two ant scouts – one red, one black – both spying the same picnic banquet sprawled on a blanket at the ready, at the same time. While still four-legged, Freleng’s ants are drawn surprisingly realistically, with proper-shaped heads, well segmented bodies, and hairs on their arms and legs. Gone is the fake coloration of mock “war paint” from Disney’s model – such that these ants would provide the new “high-bar” for animators to aspire to for the remainder of the golden age of Hollywood. The two ants converge on a single olive, and engage in a tug of war. (“Oh no you don’t” “Oh yes I do”) Ultimately, the red ant grabs the olive, and in spite, brings it down squarely on the black ant’s head, splashing him liberally with pimiento. Lifting a line that Bugs Hardaway’s “Bunny” had already used once in one of his prototype appearances, the black ant announces, “Of course you know, this means war!”

“The Fighting 69½th” (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 1/18/41 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – It cannot be doubted that Freleng must have seen both of the preceding two episodes, and he and/or his writers were moved creatively by them. Taking an idea and running with it, Freleng adapts the use of military ants to a bigger and broader campaign – an operation mirroring the tactics of World War I. Cashing in on the recent box-office success of James Cagney in the studio’s high-budget historical tribute to a fighting Irish regiment from said war, “The Fighting 69th” (1940), Freleng merely adds a fraction to it, and concocts a tale of two ant scouts – one red, one black – both spying the same picnic banquet sprawled on a blanket at the ready, at the same time. While still four-legged, Freleng’s ants are drawn surprisingly realistically, with proper-shaped heads, well segmented bodies, and hairs on their arms and legs. Gone is the fake coloration of mock “war paint” from Disney’s model – such that these ants would provide the new “high-bar” for animators to aspire to for the remainder of the golden age of Hollywood. The two ants converge on a single olive, and engage in a tug of war. (“Oh no you don’t” “Oh yes I do”) Ultimately, the red ant grabs the olive, and in spite, brings it down squarely on the black ant’s head, splashing him liberally with pimiento. Lifting a line that Bugs Hardaway’s “Bunny” had already used once in one of his prototype appearances, the black ant announces, “Of course you know, this means war!”

With the sound of a bugle, two competing ant divisions trudge through the mud to the battlefield. Emblazoned on their pennant, “The 4th Alabam ‘Ants In Your Pants’ Division” faces off against such competition as “The Royal Flying Ants”, and Catterpillar tanks bearing jars of insect powder with added cannons. The two sides dig entrenchments around the picnic grounds, and at the crack of dawn, the picnic area becomes no-man’s land. A sergeant gives a squad orders to infiltrate behind the potato chips, and capture the hot dog. They carefully sneak across the battlefield, dodging machine gun fire, and at the sound of an aerial bomb dive for cover into swiss cheese holes like foxholes. Another scream bomb sends them diving into the next piece of cheese – but right back out again, as they realize its Limburger. They succeed in reaching the hot dog, and begin carrying it off, only to find an equal number of black ants already inside the bun, who conk them on the head with small blackjacks. The black ants carry off the prize. Back in their trenches, in a stray racial stereotype, their sergeant (who has protruding flesh-colored lips), upon seeing the hot dog, zips out himself into no-man’s land, returning with a bottle, and commenting in an impression of Jack Benny program’s Eddie (Rochester) Anderson, “Forgot the mustard!”

The battle wages on. A red ant threads a needle, then shoots it using a safety pin as a bow and arrow at a stack of peas, spearing most of them like beads on a string and dragging them off. A black ant flings some of the Limburger into the red ants’ trenches. Treating it as a gas attack, a squad of red ants quickly buries the cheese with shovels, and sticks a sign in the ground above it – “Keep in a cool dry place”. At a whistle, red ants converge on a chocolate cake – then segment it into sixteen slices which disappear in separate directions – with a lone ant reentering the scene and making off with the cherry on top. A black ant squad of normal size, followed by one tiny pipsqueak of an ant, charge onto the field. All the normal sized ants return carrying small fruit. The puny one returns carrying a watermelon! The red ants advance, and, borrowing liberally from “Beach Picnic”, construct virtually the same multi-layered “Dagwood” sandwich from the previous cartoon – but with the new addition of a signature gag that would become a Warner trademark. The last ingredient is a slice of onion. But the sergeant in the trench holds up a large sign, reading “Hold the onions.” Exit one ingredient.

Finally, a large shadow looms over the picnic blanket. A young woman returns to the picnic area, folding up the blanket to bundle up the remaining food, and carrying it away. But ons square slice of cake with a cherry on top falls out from the bundle. Both armies converge upon the one remaining prize, and engage in a tug of war over it that gets nowhere. The respective generals tire of endlessly yelling, “Heave. Heave”, and decide there must be a way to settle this through a peace conference. After conferring, they announce that it is agreed the cake will be divided equally. A pair of “old soldiers” from each army, dressed as if they came from the civil war, nod to each other in agreement. One general announces, “We will divide it this way…” and draws a line in the cake frosting – except when he reaches the cherry, he curves the line so that the cherry is included on his side. “Oh, no you don’t”, shouts the other general, and redraws the line so that he has the cherry. “I beg to differ”, yells the other, and redraws it his way. The two generals come to blows – and so do all the other ants around them, The battle continues full force as we iris out on the chaos. (Notably, this cartoon would not only serve as a recurring inspiration to the industry, but would make its way into other media, forming the nucleus for a plot reworking into the Capitol “Record Reader”, “Woody Woodpecker’s Picnic” – with Mel Blanc along for the ride, providing the voicing.)

“The Way of All Pests” (Columbia/Screen Gems, Color Rhapsody, 2/28/41 – Art Davis, dir.) – An overly “talky” cartoon, wasting a good deal of its footage on a mass meeting of insects to vote to drive out a “tyrant” human who seems to swat at or nearly step on them at every turn. What could have been a good premise ultimately results in only about two minutes of the cartoon being devoted to giving the human “the works”.

“The Way of All Pests” (Columbia/Screen Gems, Color Rhapsody, 2/28/41 – Art Davis, dir.) – An overly “talky” cartoon, wasting a good deal of its footage on a mass meeting of insects to vote to drive out a “tyrant” human who seems to swat at or nearly step on them at every turn. What could have been a good premise ultimately results in only about two minutes of the cartoon being devoted to giving the human “the works”.

Ants appear to figure into one shot, where the human pours sugar cubes out of a bowl, only to have each cube march away under its own power by a pair of ant legs protruding from under each cube.

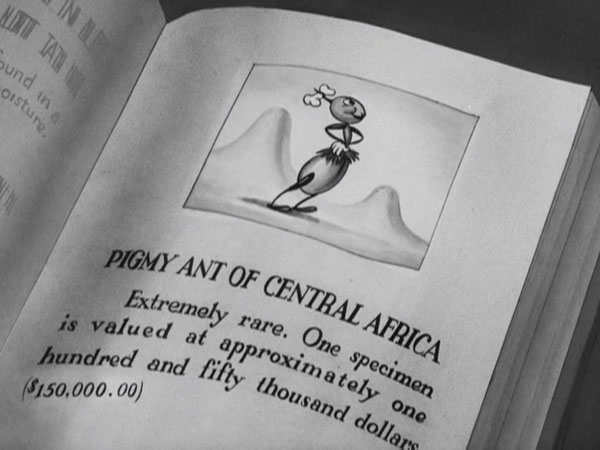

“Porky’s Ant” (Warner, Looney Tunes, Porky Pig, 5/10/41- Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.) – About this time, Chuck Jones was developing a certain affinity for cartoons about the African jungle – having recently launched into his now-politically incorrect “Inki” series about a young native/would-be hunter and his inevitable encounters with a mysterious, super-strong Minah Bird who seems to have nothing better to do than to walk around all day with a signature hop to the tune of “Fingal’s Cave” – and generally make other’s lives miserable. So Porky Pig gets the same treatment under his supervision, in standard early, decidedly-slow Jones pacing. In Africa, accompanied by a local native bearer wearing a large bone tied in his hair, Porky conducts an expedition to capture a rare pigmy ant, worth $150,000.00. The ant, also depicted in the manner of a stereotype African native, wears a tiny bone on top of his head – and covets the large one of the native bearer. He creeps up behind the human native and tugs at his minimal clothes. The bearer, continuing to balance a tall pile of Porky’s bags on his head, turns to look behind him. In doing so, he doesn’t watch where he’s going, bumps into Porky – and all the baggage goes sprawling. Porky, borrowing a “sheet” from Donald’s “Beach Picnic”, attempts to trap the ant with flypaper in front of a food bait. The ant toys with Porky, acting like he’s about to step into the trap – then in super speed just zips around the paper sheet to grab off the food and disappear with it into his ant-hill, reappearing to give Porky a little wave. Porky throws away the flypaper in disgust – which lands squarely on the face of the native bearer, who spends the next several minutes attempting to peel it off. Meanwhile, the ant takes up a safe position close to the paws of a sleeping lion.

Porky, hiding in a bush, attempts to toss a small lasso of string out to rope the ant, but gets the claw of the big cat’s paw instead. Seeing what he has pulled in, Porky pushes it back to the other side of the bush, and nervously wipes sweat off his brow. The ant continues to taunt him, but fails to notice the lion waking up. Ignoring the ant, the lion calmly walks off into the jungle. Porky sees opportunity and calls the ant’s bluff, coming out from hiding to confront him. The ant continues boldly to tease – until he backs up and realizes there’s only thin air there rather than the protective cat. The ant gives Porky a broad sheepish grin – then runs for it. Meanwhile, the lion comes upon the native bearer. The bearer finally peels back the flypaper. Seeing the lion, he decides he preferred the previous view, and re-sticks the flypaper to his face, then runs. Porky is about to corner the ant, when the bearer collides with him again, allowing the ant to escape. The flypaper falls off the native’s face, and Porky and the native face the terror of the oncoming charge of the savage lion. The ant, standing near the flypaper, sees his duty, and tosses the flypaper into the path of the approaching lion. His paws get caught up in it, sending him tumbling over and over into a ravine, to get stuck in the dead stump of an old tree. Realizing the ant has saved their lives, Porky says, “Is there anything I can do to repay you? Anything?” The ant nods yes. In the last shot, we see the feet of Porky and the bearer returning home – no dough, but happy to be alive – and behind them, the ant, learning a new walking posture as he balances on his head the bearer’s giant size hair bone. (Of final note is that Jones would return to use of the hair bone as a plot point in later years, such trinket presenting the primary motivation for the much funnier and faster-paced Inki at the Circus (1947).)

“The Bug Parade” (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 10/21/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – a spot-gag reel on insects. Ants briefly appear in the first shot among multiple other species. We are ultimately treated to the meeting of a red ant and a black ant (“Hello, Red.” “Hello, Blackie.”), and then to two columns of ants leaving an anthill, passing a tall flower stem between the columns, prompting each pair of ants to engage in endless repetition of the phrase “Bread and butter”.

“Porky’s Midnight Matinee” (Warner, Looney Tunes, Porky Pig, 11/2/41 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.) – It’s hard to believe that Porky’s Ant could have been a box office hit. Yet within a few short months, the pigmy ant returns to the screen! Jones was feeling his way at this time, and on the strength of his artistic talent alone and despite his slow pacing, had already under his belt the launching of three series: Sniffles the Mouse, the nameless Two Curious Dogs, and Inki. Seemingly, he saw series possibilities in the ant too (though one can only wonder where plotlines could hve possibly gone if he had ever attempted a third episode – mercifully, this one would prove the pigmy’s last.) Stage hand Porky closes for the night a local vaudeville theater/movie house, singing in a slightly modified lyric, “I Ought To Be In Pictures” (from the 1934 song hit “You Oughta Be In Pictures”, a tune which Warner must have picked up through its owned publishing houses, as the song was introduced in the film of a rival studio (Columbia), “New York Town” – a film so forgotten there isn’t even a listing for it on the IMDB! Use of this song also constitutes a nice harken to Porky’s hit cartoon of the preceding season, the creative live action/animation mix You Ought To Be In Pictures (1940).) Suddenly, Porky hears a whistle from backstage. On the floor is a small cage, with the pigmy ant inside. He pantomimes for Porky to open the cage door. Gullible Porky does so, and the ant, once out, disappears up a rope into the high rafters of the theater. The force of his exit overturns both Porky and his cage, at the bottom of which is an inscription: “Prof. McGurk’s Trained Pigmy Ant . Value $162,442,503.51 plus sales tax.” (Wow! The rate of inflation on that little guy in a few short months!) After repeating aloud the price tag in a more nervous stutter than usual, Porky responds with a Jack Benny-signature, “YIPE!” The pursuit is on throughout the theater.

The ant does some graceful moves on a flying trapeze. Porky precariously balances on a high-wire, while the ant vigorously vibrates the rope to make his life all the more difficult. The ant performs a trampoline act on the bread slices of a sandwich. Porky swats at him, but gets his hand stuck in a jar of mustard. The ant pantomimes for him to give the jar a good smack against the table to break it. Porky does, but screams in pain “Ouch!”, and puts his hand in his mouth to sooth the pain – not realizing he’s force-feeding himself the bottle’s contents on his hand. Helpful ant gives him a bottle to wash it down – of turpentine! Finally Porky skulks through the stage area with a peppermint stick in hand, as bait to lure the ant out. The ant sneaks under him from behind, then steals the peppermint and replaces it with a dynamite stick in Porky’s hand. Porky discovers it before it explodes, and tosses it away. It comes to land behind the ant (who is eating a broken-off morsel of the peppermint), sliding into place in the exact spot where the remainder of the peppermint stick previously rested. Porky tries to signal the ant to run, but the ant ignores him and blindly reclines on what he still thinks is the peppermint. Kaboom! The smoke clears, and Porky brightens – the explosion has blasted the ant back into his cage, now charred black with stereotype white protruding lips, with which he smiles sheepishly to the audience.

“Porky’s Café” (Warner, Looney Tunes, Porky Pig, 2/21/42 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.) – A tale told in three parts, alternating screen time. Segment 1 – Porky and his contraptive devices for preparing food. Segment 2- Porky taking and filling the orders of a low-key moustached patron (with some downright poor attempts to lip-sync the customer’s dialogue – the sound frequently doesn’t feel as if it’s coming out of his lips, and his facial expressions in shots with Porky often feel absolutely dead); Segment 3 – Conrad Cat as cook, attempting to make a morning supply of pancakes. Segment 3 provides the opportunity for an ant, hiding out in the cane sugar bag, to get accidently mixed by Conrad into the pancake batter. When poured onto the griddle, the ant jumps up in the form of a walking pancake, attempting to keep from getting a hotfoot. Conrad tries to squash him, but winds up with his hand on the hot griddle for a surprise “Ouch!” He beckons to the ant, but the ant won’t come to him – so he starts flailing away at the pancake with a spatula, and gives chase. Porky is seen coming from the other end of the café, carrying a multi-layered wedding cake. (Where’d this come from? The sign didn’t say “Bakery”, and no one ordered it. Was this a prop from Porky’s Pastry Pirates (also 1942)?) Conrad and the ant fly through a doorway, bumping Porky with the door and knocking him off balance. Porky teeters and totters his way through the café attempting to balance the cake – and destroying most of the chairs and tables at the same time. Conrad and the ant fly through the scene shortly behind Porky. They all converge at the sole customer’s table, crashing into him and his dinner. The dust clears. Porky is laid out on the customer’s dinner platter with an apple in his mouth. The customer and Conrad are buried in layers of the cake. And atop the cake, taking the place of the groom figurine – the ant, finally free of the pancake.

“Porky’s Café” (Warner, Looney Tunes, Porky Pig, 2/21/42 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.) – A tale told in three parts, alternating screen time. Segment 1 – Porky and his contraptive devices for preparing food. Segment 2- Porky taking and filling the orders of a low-key moustached patron (with some downright poor attempts to lip-sync the customer’s dialogue – the sound frequently doesn’t feel as if it’s coming out of his lips, and his facial expressions in shots with Porky often feel absolutely dead); Segment 3 – Conrad Cat as cook, attempting to make a morning supply of pancakes. Segment 3 provides the opportunity for an ant, hiding out in the cane sugar bag, to get accidently mixed by Conrad into the pancake batter. When poured onto the griddle, the ant jumps up in the form of a walking pancake, attempting to keep from getting a hotfoot. Conrad tries to squash him, but winds up with his hand on the hot griddle for a surprise “Ouch!” He beckons to the ant, but the ant won’t come to him – so he starts flailing away at the pancake with a spatula, and gives chase. Porky is seen coming from the other end of the café, carrying a multi-layered wedding cake. (Where’d this come from? The sign didn’t say “Bakery”, and no one ordered it. Was this a prop from Porky’s Pastry Pirates (also 1942)?) Conrad and the ant fly through a doorway, bumping Porky with the door and knocking him off balance. Porky teeters and totters his way through the café attempting to balance the cake – and destroying most of the chairs and tables at the same time. Conrad and the ant fly through the scene shortly behind Porky. They all converge at the sole customer’s table, crashing into him and his dinner. The dust clears. Porky is laid out on the customer’s dinner platter with an apple in his mouth. The customer and Conrad are buried in layers of the cake. And atop the cake, taking the place of the groom figurine – the ant, finally free of the pancake.

Writing this stuff is no “picnic”! Next time: Freleng takes his “troops” into a new theater of war – and also into an unexpected vintage musicale. Hanna-Barbera develops their own new angle for a trio of theatricals. And Jack Hannah raises his own “tribe” to the heights of Oscar consideration. See you next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

An “excell-ant” post, informative and very well written as always. I was especially intrigued by your discussion of Disney’s “The Grasshopper and the Ants”, which is likewise a favourite of mine. (“The World Owes Me a Living” is the anthem of musicians everywhere.) I don’t know if you noticed that the orthopteran violinist is ambidextrous: in one scene in the middle of the cartoon, he plays with the bow in his left hand, which is next to impossible in real life.

But when you say that the anteater in “Ants in the Plants” is “the first and only known use of this species in cartoons until DePatie-Freleng in 1969” — well, wrong on two counts. You’re clearly referring to the “Ant and the Aardvark” series, but the aardvark is a different species inhabiting another continent and not even closely related to the anteater, although both of them do eat ants. One of the musical numbers in :The Lion King” (the original) shows South American giant anteaters in the African savannah, and it drives me crazy every time I see it.

Secondly, I know of at least one animated anteater prior to 1969. In the Jonny Quest episode “Treasure of the Temple”, a giant anteater comes along and eats an ant that has caught the attention of Bandit the bulldog. Quite a realistic ant by cartoon standards, too, with six legs and three distinct body segments.

Looking forward to joining you and the ants at your next picnic.

There’s also the Top Cat episode, “The Case of the Absent Anteater”.

Ah yes, I had forgotten about that one and just watched it again. During the course of the cartoon, the Absent Anteater eats a sandwich, two apples, a banana, six hot dogs, and even Top Cat’s watch — but not a single ant!

Well, you left out one minor cartoon from Warner Brothers, although I’m not quite sure whether or not the insects are supposed to be ants, and the cartoon is more a music vehicle–I’m referring of course to “BINGO CROSBY-ANNA”. Aside from ants, it seems that the only other insects to get a great deal of attention from animators in the theatrical age were bees and fleas, with the occasional appearance of spiders. Once we get to flies and fleas, the post will become far larger, especially when it comes to rare MGM cartgoons. For fleas, there was “CIRCUS DAZE”, one of the taboo BOSKO cartoons, although the bulk of the cartoon puts Bruno uncomfortably at center stage; and then tehre is the later Rudy Ising cartoon “THE HOMELESS FLEA” which toys with some impressive point-of-view shots, and Tex Avery’s two cartoons, “WHAT PRICE FLEADOM” and “THE FLEA CIRCUS”. Oh, and I’m forgetting “DIXIELAND DROOPY” which focuses more on the musical fleas on the dog’s back. But, I’m sure you’ll get to these in time, no matter what the season. As always, a terrific post.

This is the first time I’ve seen “Ants in the Plants”, and I must say, it’s a very impressive short. Especially the opening shot, which is a little more elaborate than the usual Stereoscopic setback shot, the camera moving on a sweeping parabolic track rather than merely panning side to side. If the story itself isn’t a trial run for “Mr. Bug Goes to Town”, that first shot is certainly a preview of that film’s impressive title sequence.