Last week, we left off with a character premiere (Road Runner and Wile E. Coyote) that resorted to the excitement of skiing as an initial attraction. Within a few short weeks, another animation legend would be born, also riding to his first success on a pair of wooden boards. Many other notables would follow in their paths through the twists and turns of the 1950’s.

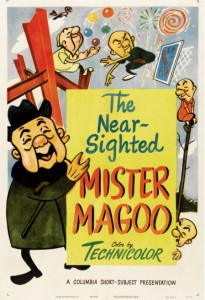

The Ragtime Bear (UPA/Columbia, Mister Magoo, 9/29/49 – John Hubley, dir.), marks the inaugural appearance of the nearsighted curmudgeon Magoo and his dense nephew Waldo – this time out for a weekend of relaxation at the posh “Hodge Podge Lodge” in the snow-capped mountains. While Magoo seeks peace and quiet, Waldo, to pass the time, has brought along a banjo, on which he picks away in country bluegrass tradition. Magoo is already fed up with it by the time they reach the lodge. “Waldo! Stop that guitar!”, he cautions, then blindly proceeds straight for a cliff edge. Waldo saves Uncle Magoo by thrusting his banjo underneath for a stepping stone between two ledges, on which Magoo walks to safety. But when Waldo tries to cross the ravine himself, the opposite ledge gives way, sending Waldo plummeting. Neither of them has noticed a tag-along behind them – a grizzly bear, entranced by the banjo music. As Waldo falls into the ravine, his hat and the banjo still twirl in the air above him – and are caught by the bear. Predicting Yogi Bear’s chapeau years before the creation of the character, the bear dons the green hat, then becomes a rapid self-study on the stringed instrument, mastering it in a matter of less than a minute. Magoo, about to step off another ledge, returns to confiscate the instrument. “Gimme that mandolin”, he shouts – completely convinced the bear is his nephew in his raccoon coat.

After introductions of his nephew in the lodge lobby (leaving the desk clerk well compressed from the force of a bear hug), the bear takes the opportunity of another Magoo misstep to regain the banjo and break into another tune. Determined to stop the music, Magoo for once sees clearly enough to hatch an idea, putting the banjo on a chair lift and sending it to the top of the mountain peak. Giggling in triumph, Magoo turns to head back to the warm lodge – only to hear the plinks and plunks of a distant melody. Down from the peak on the ski jump rides the bear on skis, banjo in hand – and collides with Magoo. Riding on the point of the skis, Magoo gives Waldo a final warning, seizes the banjo, and attempts to step off. He instantly breaks into an endless series of cartwheels down the slope (cleverly matched with the sound effect of banjo strings plucked in ultra-high notes below the tuning bridge), and lands with his head buried in the snow.

After introductions of his nephew in the lodge lobby (leaving the desk clerk well compressed from the force of a bear hug), the bear takes the opportunity of another Magoo misstep to regain the banjo and break into another tune. Determined to stop the music, Magoo for once sees clearly enough to hatch an idea, putting the banjo on a chair lift and sending it to the top of the mountain peak. Giggling in triumph, Magoo turns to head back to the warm lodge – only to hear the plinks and plunks of a distant melody. Down from the peak on the ski jump rides the bear on skis, banjo in hand – and collides with Magoo. Riding on the point of the skis, Magoo gives Waldo a final warning, seizes the banjo, and attempts to step off. He instantly breaks into an endless series of cartwheels down the slope (cleverly matched with the sound effect of banjo strings plucked in ultra-high notes below the tuning bridge), and lands with his head buried in the snow.

While the rest of the cartoon deviates from a skiing theme, the bear ultimately regains the instrument by masquerading as a bearskin rug at night, substituting the real rug in Waldo’s bed, and fooling Magoo into firing a shotgun which he thinks has riddled Waldo with buckshot. The real Waldo finally staggers in and complicates things further. A final threat by Magoo to really shoot Waldo if he plays as much as one more note leads to the bear framing Waldo by playing the fatal cadenza. Waldo takes to the hills amidst buckshot blasts, while the bear accompanies the proceedings with bluegrass chase music from the safety of a nearby tree.

The animated end-shot for this film has been presumably lost in favor of a “Columbia Favorite” blank art-card on reissue. An attempt to recreate the missing ending (nice looking, if I do say so myself), is included for a treat on the print imbedded below.

Snow Foolin’ (Paramount/Famous, Screen Song, 12/16/49, I. Sparber, dir.), includes a brief ski-jump by a kangaroo with a baby “Joey” in her pouch, filming the event with a newsreel camera from P.O.V. angle for posterity. Unfortunately, the jump doesn’t go so well, and mama kangaroo’s path is mostly straight down after leaving the ski ramp. She lands in a heap on the snow – but baby safely descends with a parachute, camera and all, neatly into her pouch.

A Swiss Miss (Terrytoons/Fox, Mighty Mouse, 6/20/51 – Mannie Davis, dir.), allows Oil Can Harry to briefly use skis as a means of escaping with Pearl Pureheart from a Swiss Alps setting. He passes a St. Bernard who is too busy reciting poetry about his rescuing prowess to actually engage in a rescue himself, and the wind from Oil Can’s passing blows the dog’s fur coat off, exposing the dog in his underwear. Oil Can’s downhill run, however, ends in a cliff and an upwards curve. He tosses away Pearl and pulls at the forward end of his skis, with sound effect suggesting applying the brakes (a borrow from “Swiss Ski Yodelers”). Mighty Mouse, in pursuit, catches Pearl, while Oil Can flies over the ledge, then drops into a snowbank behind the St. Bernard (good trick, as we thought the St. Bernard was well behind him miles above). With a victim close at hand, the St Bernard finally opens his brandy barrel, and we repeat the gag from “Dear Old Switzerland” with the dog mixing the brandy in a cocktail shaker, and Oil Can’s hand producing a martini glass in which the dog pours the drink and adds an olive. Oil Can recovers and emerges from the snow in a whirlwind, taking off uphill. “My goodness”, remarks the surprised dog. “I’ve saved the wrong person!” Oil Can defies gravity and continues speeding uphill, morphing into an express train, and recaptures Pearl right out of Mighty’s arms. And the endless battle goes on and on, to be continued in the next cartoon.

‘Sno Fun (Terrytoons/Fox, Heckle and Jeckle, 11/1/51 – Eddie Donnelly, dir.), is essentially the birds’ reworking of Tex Avery’s Droopy classic “Northwest Hounded Police” (1946), with some new gag material and making the most of the duo’s meddlesome personalities. As Mounties who appear everywhere, H&J pursue villain Powerful Pierre over the frozen North. Pierre briefly mounts a pair of skis and engages in a brisk downhill run. The camera cuts to a close tracking shot, as Pierre declares, “I am free. Never will they catch me now.” Unfortunately, as the camera cuts to a longer shot, Heckle and Jeckle are revealed, having substituted themselves in place of Pierre’s skis, with Jeckle pointing a revolver upwards at Pierre and saying, “Who says so?”

North Pal (Paramount/Famous, Casper, 5/29/53 – I. Sparber, dir.) – A typical formula episode, with Casper befriending a baby seal. In a short climactic sequence, Casper breaks off two sets of long icicles and converts them to skis for himself and his pal. Casper goes first, with the seal to play, “follow the leader”. Casper skis through a snowbank, ghosting his way through with the icicles only making two small holes. The seal plows through the whole snowbank and is briefly transformed into a snow walrus. Casper next skates through a tree trunk, while the seal clunks right into it. (Casper, are you oblivious to what you’re doing, or is this the way you treat a friend?) To put his pal into more peril, Casper skis over what appears to be another snowbank, but is really a polar bear. Turning around, the bear sees the oncoming seal, and waits at the foot of the slope with mouth open. The seal tries to put on the brakes – and manages to jam his icicle skis into the polar bear’s jaws to avoid being swallowed. Of course, Casper eventually gets wise to what’s happening behind him and saves the day as usual.

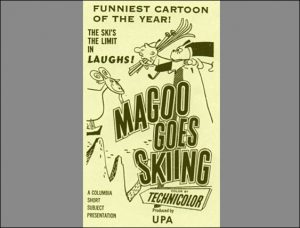

Magoo Goes Skiing (UPA/Columbia, Mister Magoo, 3/11/54 – Pete Burness, dir.), falls a bit short of qualifying as classic Magoo. The opening sets up a gag to follow, as Magoo calls out to a mountain peak with his best attempt at a yodel – but is disappointed to hear no echo. Of course, the fact that he’s serenading a picture on the ski lodge wall rather than a real mountain could be the explanation. Magoo actually isn’t as completely disoriented as usual, as he really is at a ski resort and really intends to go skiing – but of course picks up a St. Bernard along the way whom he thinks is his nephew Waldo. Warned of the danger of avalanches by the lodge owner, Magoo responds with a terrible pun, “‘Alf a ‘lanche is better than no ‘lanche at all.” He asks directions from a local which is really a road sign, and getting no response, tops himself in bad puns with “Heaven Alps those who Alp themselves.” He climbs to uncharted heights of the Matternott mountain, and is only saved from toppling off its peak by the counterweight of the St. Bernard on his skis. Comes the inevitable downhill run – in which Magoo’s hollering starts the equally inevitable avalanche. Waldo, the lodge owner, and everyone else at the lodge are bowled over by the oncoming snow – and wind up dangling in single file from the tips of Magoo’s skis wedged in the rear balcony railing of the lodge. Above, Magoo and the dog listen to the cries for help of the lodge owner dangling as bottom-man on the totem pole in the canyon. “Ha, the echo!”, Magoo tells the dog. “I yodeled this morning, and now it’s coming back. A little late…but clear as a bell!”

Magoo Goes Skiing (UPA/Columbia, Mister Magoo, 3/11/54 – Pete Burness, dir.), falls a bit short of qualifying as classic Magoo. The opening sets up a gag to follow, as Magoo calls out to a mountain peak with his best attempt at a yodel – but is disappointed to hear no echo. Of course, the fact that he’s serenading a picture on the ski lodge wall rather than a real mountain could be the explanation. Magoo actually isn’t as completely disoriented as usual, as he really is at a ski resort and really intends to go skiing – but of course picks up a St. Bernard along the way whom he thinks is his nephew Waldo. Warned of the danger of avalanches by the lodge owner, Magoo responds with a terrible pun, “‘Alf a ‘lanche is better than no ‘lanche at all.” He asks directions from a local which is really a road sign, and getting no response, tops himself in bad puns with “Heaven Alps those who Alp themselves.” He climbs to uncharted heights of the Matternott mountain, and is only saved from toppling off its peak by the counterweight of the St. Bernard on his skis. Comes the inevitable downhill run – in which Magoo’s hollering starts the equally inevitable avalanche. Waldo, the lodge owner, and everyone else at the lodge are bowled over by the oncoming snow – and wind up dangling in single file from the tips of Magoo’s skis wedged in the rear balcony railing of the lodge. Above, Magoo and the dog listen to the cries for help of the lodge owner dangling as bottom-man on the totem pole in the canyon. “Ha, the echo!”, Magoo tells the dog. “I yodeled this morning, and now it’s coming back. A little late…but clear as a bell!”

The Clockmaker’s Dog (Terrytoons/Fox, January, 1956 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) has already been discussed in my previous post “Countdown to 2020: More Tick Tock Talk” for its involvement with clocks, but also features a fast-paced skiing sequence. Dealing with a little dog (Fritzie) who wants to join the ranks of the St. Bernards, the cartoon features a rescue attempt by the monastery dog troops riding like humans on skis. Fritzie joins them, without ski poles and using slats from a broken brandy barrel as his footwear )the gag again from Krazy Kat’s “Snow Time”). A first jump from a ledge flips Fritzie so that he is briefly skiing down the hill on his tail. A St. Bernard negotiates a widening gap ahead of him by jumping into the air to take his weight off his skis, and bracing himself with his arms spread apart, the rings of his ski poles landing on each opposite ledge and acting like a pair of wheels to roll him down the slope. Fritzie, having no poles, does the same thing the hard way – by flipping upside down and spreading his ears to slide down the ledges on each side. A sort of natural ski-jump next faces the dogs, with a snowdrift plugging up the end of the jump. This allows Terry to use a gag that had been hanging around at least as early as 1930’s “Popcorn” – having each jumper stopped at the end of the ramp, only to have the next jumper impact him from behind to send him up into the leap. Fritzie, being the last in the line, gets the tips of his skis stuck in the snowdrift, which sends his torso spinning within his stopped thighs like a winding rubber band. Just as quickly, he unwinds, the force of which propels him off the ledge. He zooms over the four dogs ahead of them, leaving each driven into a quartet of conjoined silhouette craters in the snow. Fritzie keeps on going, and rolls into a giant snowball – just in time to intersect the fall of his master out looking for him in the mountains, and saving the master’s life.

Tree-Cornered Tweety (Warner, Tweety and Sylvester, 5/19/56 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – a series of black-out gag sequences, loosely themed as a parody of Jack Webb’s “Dragnet” radio and TV series, includes a wintertime gag with Tweety donning kitchen spoons as snowshoes to venture out for replenishment of his supply of bird seed. Sylvester leaps out from behind a tree with skis and ski poles, and takes off after Tweety down the hill. But it’s a short run, as he smacks face first into a tree. All Tweety sees is Sylvester’s skis, which have separated from his feet and continue down the hill, passing Tweety on either side. (The scene was later reused verbatim in the cheater clip-fest, “Trip for Tat” (1960).

The Big Snooze (Lantz/Universal, Chilly Willy, 10/21/57 – Alex Lovy, dir.) finds our precocious penguin holed up for the winter among a cave of hibernating bears at Grizzly National Park. A message from Washington about bear disturbances sends a ranger snooping. His efforts to oust Chilly arouse one bear into a somnambulistoc sleepwalk. Chilly complicates the ranger’s job by dropping a pair of skis in the bear’s path, setting the bear into a rapid downhill run. The ranger tries his best to keep the bear from harm without waking him. First, he physically pushes a giant tree out of the bear’s oncoming path. He leaps to spread himself across a small chasm as a human bridge for the bear to pass over. The next obstacle is a “Bridge Out’, of which remains only three wooden boards and about half of the framework beams In superspeed motion, the ranger repeatedly repositions the three boards under the bear to give him a skiing surface up to the end of the bridge framework – then, when the bear falls off, the ranger joins him on the back of his skis, and pops open a parachute to land them in safety. As the bear slides down another slope toward a cabin, the ranger races ahead of him, chopping a hole in the wall for the bear to slide through. The ranger runs around to the front door to open it for the bear – but upon opening the door, nothing happens. Wondering where the bear disappeared, the ranger sneaks a peek inside – and gets bowled over by the bear accompanied by the sound of a freight train whistle. The bear plunges off a cliff, but lands in a chair lift to a snowy summit. At the top, he is ejected from the chair, and slides down a ski jump. After a soaring leap, the bear crashes right into a tree trunk. But the impact merely pokes out a bear-shaped panel of wood from the other side of the tree, and the bear slides neatly out of the trunk. He finally slides into the door of the ranger station, and when the ranger finally catches up, the bear is comfortably asleep in the ranger’s bed. Chilly ultimately wraps things up with a final piece of mayhem – arousing all the other bears into a sleepwalking state, pointed at Washington D.C., and placing into each bear’s arms a giant firecracker. The ranger barely has time to place a pair of earmuffs on the park commissioner, as the explosion blows the lid off the capitol building, and leaves its dome balanced off-center at a rakish angle.

The Big Snooze (Lantz/Universal, Chilly Willy, 10/21/57 – Alex Lovy, dir.) finds our precocious penguin holed up for the winter among a cave of hibernating bears at Grizzly National Park. A message from Washington about bear disturbances sends a ranger snooping. His efforts to oust Chilly arouse one bear into a somnambulistoc sleepwalk. Chilly complicates the ranger’s job by dropping a pair of skis in the bear’s path, setting the bear into a rapid downhill run. The ranger tries his best to keep the bear from harm without waking him. First, he physically pushes a giant tree out of the bear’s oncoming path. He leaps to spread himself across a small chasm as a human bridge for the bear to pass over. The next obstacle is a “Bridge Out’, of which remains only three wooden boards and about half of the framework beams In superspeed motion, the ranger repeatedly repositions the three boards under the bear to give him a skiing surface up to the end of the bridge framework – then, when the bear falls off, the ranger joins him on the back of his skis, and pops open a parachute to land them in safety. As the bear slides down another slope toward a cabin, the ranger races ahead of him, chopping a hole in the wall for the bear to slide through. The ranger runs around to the front door to open it for the bear – but upon opening the door, nothing happens. Wondering where the bear disappeared, the ranger sneaks a peek inside – and gets bowled over by the bear accompanied by the sound of a freight train whistle. The bear plunges off a cliff, but lands in a chair lift to a snowy summit. At the top, he is ejected from the chair, and slides down a ski jump. After a soaring leap, the bear crashes right into a tree trunk. But the impact merely pokes out a bear-shaped panel of wood from the other side of the tree, and the bear slides neatly out of the trunk. He finally slides into the door of the ranger station, and when the ranger finally catches up, the bear is comfortably asleep in the ranger’s bed. Chilly ultimately wraps things up with a final piece of mayhem – arousing all the other bears into a sleepwalking state, pointed at Washington D.C., and placing into each bear’s arms a giant firecracker. The ranger barely has time to place a pair of earmuffs on the park commissioner, as the explosion blows the lid off the capitol building, and leaves its dome balanced off-center at a rakish angle.

UPA’s Winter Sports, was a musical element of the The Boing Boing Show, first telecast in May 1958. Mel Leven wrote the tune – and we think (or more accurately, our friend Mike Kazaleh suspects) that Osmond Evans was the director. Here, three jolly winter sports enthusiasts extoll the wonders of winter and their love of snow, ice skating, sledding, belly-flopping and yes, skiing! This is such a delightful little piece – I wish this series was restored and available again (hint, hint Universal Pictures)…

Two Scents Worth (Warner, Pepe Le Pew, 10/15/55 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.) – Kitty is as usual pursued by the amorous skunk – this time in the French Alps. Running for refuge, she climbs a tall ladder, and finds herself at the edge of a ski jump. Pepe appears behind her in mountaineer’s hat. “I am your guide to love, no?” He seizes her in the inevitable clinch, between kisses exclaiming, “The conquest of Everest will pale into insignificance.” Kitty finds a pair of stray skis, and slides down the ramp on one. Pepe finds his own pair and follows. As they sail through the air, Pepe plays as if he is in a bomber plane, speaking to himself: “Navigator to Pilot – Pretty girl at 3:00. – – Pilot to Navigator: Rowr Rowr!” He pretends to shoot at Kitty. “I pierce you with the ack-ack of love”, he boasts. His flight is abruptly cancelled as he crashes face first into a tree trunk. Quoting from the famous poem, “Trees”, he asides to the audience, “Poems were made by fools like me…” Pepe continues the pursuit by swinging through the trees like Tarzan, commenting to us, “I always got an ‘A’ in gym.” He catches up with his skis, and stays in close pursuit of Kitty, up and down the hills. Finally, Kitty runs out of room, as the edge of a cliff looms near. She scrambles with her claws to slow the ski, and stops it just teetering over the cliff edge. But along comes Pepe at full speed and scoops her up in his arms, flying off the cliff. “Darling, how good of you to wait for me”, he tells her. Terrified of a horrendous fall, she now clings to him. “She is no longer timid”, Pepe tells us. They fall out of frame – but suddenly, the frame is filled by the billowing of an opening parachute. “A true gentleman must be prepared for anything”, Pepe explains to the camera, as he and Kitty float gently earthward, suspended from a heart-shaped parachute, for a heart-shaped iris out.

Two Scents Worth (Warner, Pepe Le Pew, 10/15/55 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.) – Kitty is as usual pursued by the amorous skunk – this time in the French Alps. Running for refuge, she climbs a tall ladder, and finds herself at the edge of a ski jump. Pepe appears behind her in mountaineer’s hat. “I am your guide to love, no?” He seizes her in the inevitable clinch, between kisses exclaiming, “The conquest of Everest will pale into insignificance.” Kitty finds a pair of stray skis, and slides down the ramp on one. Pepe finds his own pair and follows. As they sail through the air, Pepe plays as if he is in a bomber plane, speaking to himself: “Navigator to Pilot – Pretty girl at 3:00. – – Pilot to Navigator: Rowr Rowr!” He pretends to shoot at Kitty. “I pierce you with the ack-ack of love”, he boasts. His flight is abruptly cancelled as he crashes face first into a tree trunk. Quoting from the famous poem, “Trees”, he asides to the audience, “Poems were made by fools like me…” Pepe continues the pursuit by swinging through the trees like Tarzan, commenting to us, “I always got an ‘A’ in gym.” He catches up with his skis, and stays in close pursuit of Kitty, up and down the hills. Finally, Kitty runs out of room, as the edge of a cliff looms near. She scrambles with her claws to slow the ski, and stops it just teetering over the cliff edge. But along comes Pepe at full speed and scoops her up in his arms, flying off the cliff. “Darling, how good of you to wait for me”, he tells her. Terrified of a horrendous fall, she now clings to him. “She is no longer timid”, Pepe tells us. They fall out of frame – but suddenly, the frame is filled by the billowing of an opening parachute. “A true gentleman must be prepared for anything”, Pepe explains to the camera, as he and Kitty float gently earthward, suspended from a heart-shaped parachute, for a heart-shaped iris out.

Weasel While You Work (Warner, Foghorm Leghorn, 9/6/58 – Robert McKimson, dir.), deserves only the briefest mention. In a departure episode setting the feud between Foghorn and Barnyard Dawg in the snow-covered winter, Foghorn tries various winter sports, including a brief try at skiing. “Look, I’m, flying”, Foghorn shouts after making a jump. But a weasel has placed a tall pole right in his way, causing him to crash into it face first, and slide down it neatly into a cooking pot. The John Seely stock music doesn’t help.

The advent and heyday of the television cartoon loom as the next mogul on out path. We’ll bravely dace them next time, along with the last of the snowy theatricals.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Ah, you’ve done it again! “The Ragtime Bear” is the standout of this week’s animation ski trail. Paradoxically, there’s very little ragtime music here, and the bear doesn’t play what little there is.

Ragtime generally uses the four-stringed tenor banjo, tuned in fifths like a viola (C3-G3-D2-A2) and strummed with a flat pick. This is the strumming technique used by Waldo at the beginning of the cartoon (he does not pick away “in country bluegrass tradition”), though the close harmony of the chords indicates that a five-string instrument — the standard bluegrass instrument, tuned to a G major chord and ordinarily played with finger picks — is being used. The bear, however, plays the banjo using the three-fingered picking technique that Earl Scruggs was popularising at this time. The tune he plays is in the uncharacteristic key of B-flat, which could only be executed by tuning the strings of the banjo down a tone and also tuning the lowest string down a minor third from D to B-flat. Such low tension on that string would cause the pitch to go flat during the decay, which doesn’t happen; so either the playback of the recording was at a slightly slower rate, or the banjo player used a slightly larger instrument that was normally tuned to a lower key. Since the bear’s performance of “Coming ‘Round the Mountain” later in the cartoon is in the standard key of G major, I suspect the former. In any case, as a former ragtime banjoist I find it all very intriguing, and I would be very grateful for any light that can be shed on the identity of this musician or other aspects of the music in this cartoon.

The very familiar music that plays during the scene with the desk clerk in the lobby of the lodge is the Pizzicato from the ballet Sylvia by Leo Delibes, just in case anybody was wondering. A lot of standard cartoon cues come from that ballet.

When Pierre discovers that his skis have transformed into Heckle and Jeckle, he exclaims: “L’homme de poisson!” The man of fish??? Is this just the sort of fractured French that Michael Maltese used to put in his Pepe Le Pew cartoons, or is there an actual joke here? Be that as it may, I can’t listen to Dayton Allen’s Humphrey Bogart impersonation without thinking of “Lancelot Link, Secret Chimp”.

Looking forward to next week’s trail through the television cartoons of the sixties — and one particular ski adventure involving a stolen diamond and a beauty contest, if you get my “drift”! SLALOM!

Sorry, I misspoke. I know full well that the interval between B-flat and D is a MAJOR third, not a minor third. Maybe now the ghosts of my music theory professors will stop tormenting me.

There’s also a skiing scene in another Heckle and Jeckle cartoon released the same year as “‘Sno Fun”. In “Movie Madness” (Terrytoons/Fox, 7/11/51 — Connie Rasinski, dir.), H&J sneak into a film studio and are pursued by a security guard. After impersonating a couple of Hollywood stars of the era (i.e., Jimmy Durante and Groucho Marx), Heckle (or possibly Jeckle) aims a gun at the guard and, imitating Edward G. Robinson, tells him: “All right, smart guy! You’re not pushing me around any more, see? I don’t have to take it from you or anyone else, see?” The guard backs away from this fearsome display of aggression, and then Jeckle (or possibly Heckle) put skis on the guard’s feet and pulls him over the verge of a snowy slope. (Apparently the studio is on top of a mountain.) The terrified guard skis backwards down the mountainside, narrowly missing dangerous chasms, as the magpies, in an overhead crane, film the scene and give direction: “That’s it! Get more personality into it! Keep going!… More action, more action!” But the guard has the last laugh. When Heckle and Jeckle have tired of tormenting the poor guy, the studio exit leads them right into the back of a police wagon.

One might not expect a cartoon about a dog show to have any skiing in it, but I found one that does.

“The Dog Show” (Terrytoons/Fox, 26/5/50 — Eddie Donnelly, dir.), like its Terrytoons predecessor “The Dog Show” (1934) and the similarly Warner Bros. cartoons “Dog Daze” (1937) and “Dog Tales” (1958), consists of a series of canine-themed blackout gags with no plot to speak of. Some gags are used in more than one of these cartoons, e.g., dogs that look like their owners, a Spitz that spits, and the St. Bernard dispensing alcoholic beverages. But “The Dog Show” of 1950 is the only one with a character on skis.

A skier, having begun his descent with confidence, loses his balance and tumbles down the mountainside, landing in a snowdrift. The faithful St. Bernard comes to the rescue with his keg of spirits. We hear the sounds of pouring and imbibing, and before long the skier and the dog emerge from the snowdrift singing “We Won’t Get Back Until Morning” in an advanced state of intoxication. Then the two of them dance a Schuhplattler — that is, that Bavarian folk dance with all the slapping and kicking that men in lederhosen do at Oktoberfest. As the tempo of the music increases, the dance devolves into a drunken donnybrook