Another batch of animated eccentricities, including three more from the pencils of Tex Avery’s unit, the first Paramount Noveltoon, a double-dose of Bugs Bunny, and more one-shots from Disney and Columbia.

Who Killed Who? (MGM, 6/5/43 – Tex Avery, dir.) – With apologies for being out of chronological sequence, this often-reviewed crime classic directly spoofs a popular series of MGM live-action shorts running concurrently at the time, “Crime Does Not Pay”, including live-action wraparounds as an announcer promises that, from the pages of criminal files and through the medium of the animated cartoon, it will once again be proven here that the above-quoted adage still holds true. The film is abundant with Avery sign gags, including a variant in the introductory shot of the Interior of the murder mansion, reading “Spooky, isn’t it?” The chair of the owner of the mansion includes neon flashing on the seat back, reading “The Victim”. Said victim, an old dog, is well-aware of his presence in a cartoon – and how could he not be, when he quivers from reading a mystery novel entitled “Who Killed Who? (From the cartoon of the same name)”. He addresses the camera: “If this picture is anything like the book, I get bumped off.” A dagger hits the wall, attached to which is a note reading, “You will die at 11:30.” “This is terrible. I can’t die at 11:30″, says the dog. A second dagger delivers a second note: “Okay, so we’ll make it 12:00.” As midnight is announced in the manner of a telephone company time signal by the skeleton of a cuckoo bird, three shots ring out from a revolver, making metallic sounds like the musical chimes of NBC. Enter a bulldog cop. “Everybody stay where ya are. Don’t nobody move”, he shouts to the audience. The shadow of one patron rises to cross a row of seats. The cop socks the shadow on the head with a billy club. “That goes for you too, bud!.”

Who Killed Who? (MGM, 6/5/43 – Tex Avery, dir.) – With apologies for being out of chronological sequence, this often-reviewed crime classic directly spoofs a popular series of MGM live-action shorts running concurrently at the time, “Crime Does Not Pay”, including live-action wraparounds as an announcer promises that, from the pages of criminal files and through the medium of the animated cartoon, it will once again be proven here that the above-quoted adage still holds true. The film is abundant with Avery sign gags, including a variant in the introductory shot of the Interior of the murder mansion, reading “Spooky, isn’t it?” The chair of the owner of the mansion includes neon flashing on the seat back, reading “The Victim”. Said victim, an old dog, is well-aware of his presence in a cartoon – and how could he not be, when he quivers from reading a mystery novel entitled “Who Killed Who? (From the cartoon of the same name)”. He addresses the camera: “If this picture is anything like the book, I get bumped off.” A dagger hits the wall, attached to which is a note reading, “You will die at 11:30.” “This is terrible. I can’t die at 11:30″, says the dog. A second dagger delivers a second note: “Okay, so we’ll make it 12:00.” As midnight is announced in the manner of a telephone company time signal by the skeleton of a cuckoo bird, three shots ring out from a revolver, making metallic sounds like the musical chimes of NBC. Enter a bulldog cop. “Everybody stay where ya are. Don’t nobody move”, he shouts to the audience. The shadow of one patron rises to cross a row of seats. The cop socks the shadow on the head with a billy club. “That goes for you too, bud!.”

The array of classic Avery gags that follows has been well-penned about before. Ultimately, a hooded figure gets a pistol pointed in the cop’s back, demanding that he “Reach for the ceiling.” The cop does – although the ceiling where he stands is a good three stories above him. But the gun is empty – as depicted by a gas gauge built into its handle. The cop chases the hooded villain all through the mansion, finally faking him out by revealing effeminate-looking legs partially concealed by a curtain, which turn out to be the cop’s when the curtain is opened. The cop whacks the villain with a mallet, then reaches for the villain’s hood. “Now we’ll see who dun-it”, he boasts to the audience, and lifts the hood. The shot reverts to a matching live-action shot, and the culprit turns out to be the live announcer, who confesses, “I done it”, and wails bitterly as the film fades out.

The array of classic Avery gags that follows has been well-penned about before. Ultimately, a hooded figure gets a pistol pointed in the cop’s back, demanding that he “Reach for the ceiling.” The cop does – although the ceiling where he stands is a good three stories above him. But the gun is empty – as depicted by a gas gauge built into its handle. The cop chases the hooded villain all through the mansion, finally faking him out by revealing effeminate-looking legs partially concealed by a curtain, which turn out to be the cop’s when the curtain is opened. The cop whacks the villain with a mallet, then reaches for the villain’s hood. “Now we’ll see who dun-it”, he boasts to the audience, and lifts the hood. The shot reverts to a matching live-action shot, and the culprit turns out to be the live announcer, who confesses, “I done it”, and wails bitterly as the film fades out.

• Watch it here.

No Mutton For Nuttin’ (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon (Blackie), 11/26/43 – no director credits) – This was the first in Paramount’s new all-color collection of mini-series and one shots, and its eccentricity and lack of director credit seems to indicate that the entire staff was requested to contribute to ensure a successful series launch. Reaching outside its usual stable of voice talent, I believe this film marks the first association with the studio of Arnold Stang, who would not only supply Blackie’s voice throughout the mini-series’ run, but later Herman the Mouse, Top Cat for television, and appear every so often on camera, particularly in the memorable service station destruction sequence of It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World.

A wolf seeks sustenance on the farm, and, listening to the various sounds from within the gates, expresses a mental preference for the “high-priced spread”, so to speak, channeling his thoughts on lamb chops, currently $10 a pound. He gains entry by simply charging the fence, getting trisected into three pieces, but simply reassembling while still on the run. All the lambs flee, except Blackie, a black sheep, busy reading a book on “How To Outsmart a Wolf.” Without missing a step, Blackie sticks out one foot as the wolf passes in pursuit of the flock, tripping him up. The wolf becomes aware of Blackie, and smacks his lips, remaking “Dark meat.” A somewhat Avery-esque style chase is on, with many odd gags. As the two characters struggle behind a tree, their arms extend into view at intervals on either side of the trunk, holding an array of lethal weapons including a pistol, an axe, and a bomb. The wolf gets Blackie in a sack, yet then passes him standing next to a tree, shooting dice. “Huh?”, exclaims the wolf, and the letters of the word emit from his lips, separate and regroup in mid-air into the image of a pointing hand, pointing the wolf’s attention back to the sheep he just passed. A slow-motion chase underwater gives Blackie the opportunity to strike a match and give the wolf a hotfoot – while underwater! A crap game has Blackie kiss the dice, one of which develops a face blushing in embarrassment. The dice turn out to be “loaded”, not only including flipping panels to change numbers, but dynamite to blast the loser. Blackie fills in the crater left from the explosion with dirt, assuming he is burying the wolf, remaking “Too bad. I had a lot of fun with this guy. I was just beginning to like him. Oh, well. Here tomorrow, gone today.” But the wolf is not in the hole, instead behind Blackie, and announces, “For you, this is curtains”, reaching above the line of the screen frame to pull down a black curtain across the entire image, allowing for a fade in to the interior of the wolf’s cabin home.

A wolf seeks sustenance on the farm, and, listening to the various sounds from within the gates, expresses a mental preference for the “high-priced spread”, so to speak, channeling his thoughts on lamb chops, currently $10 a pound. He gains entry by simply charging the fence, getting trisected into three pieces, but simply reassembling while still on the run. All the lambs flee, except Blackie, a black sheep, busy reading a book on “How To Outsmart a Wolf.” Without missing a step, Blackie sticks out one foot as the wolf passes in pursuit of the flock, tripping him up. The wolf becomes aware of Blackie, and smacks his lips, remaking “Dark meat.” A somewhat Avery-esque style chase is on, with many odd gags. As the two characters struggle behind a tree, their arms extend into view at intervals on either side of the trunk, holding an array of lethal weapons including a pistol, an axe, and a bomb. The wolf gets Blackie in a sack, yet then passes him standing next to a tree, shooting dice. “Huh?”, exclaims the wolf, and the letters of the word emit from his lips, separate and regroup in mid-air into the image of a pointing hand, pointing the wolf’s attention back to the sheep he just passed. A slow-motion chase underwater gives Blackie the opportunity to strike a match and give the wolf a hotfoot – while underwater! A crap game has Blackie kiss the dice, one of which develops a face blushing in embarrassment. The dice turn out to be “loaded”, not only including flipping panels to change numbers, but dynamite to blast the loser. Blackie fills in the crater left from the explosion with dirt, assuming he is burying the wolf, remaking “Too bad. I had a lot of fun with this guy. I was just beginning to like him. Oh, well. Here tomorrow, gone today.” But the wolf is not in the hole, instead behind Blackie, and announces, “For you, this is curtains”, reaching above the line of the screen frame to pull down a black curtain across the entire image, allowing for a fade in to the interior of the wolf’s cabin home.

Blackie is all tied up on a platter, but requests a last wish – a smoke. Producing a pack with one hand miraculous free of the bonds, Blackie pops out from the carton one cigarette ten times taller than the pack, remarking “King Size.” As Blackie busies himself with the smoking, the wolf steps outside to sharpen his carving knife on a grinding wheel. Behind him, the cabin is seen, black smoke billowing from every crack and door and window frame. Suddenly, the whole house ignites in flame, is reduced to charred matchsticks without even so much as a sound effect, and crumbles, leaving only an unharmed Blackie standing next to the remaining stones of the fireplace. The horrified wolf charges Blackie with his knife, lifts Blackie by the throat, and proclaims he will cut Blackie to ribbons. Blackie points out, “Ya ain’t got time. This is the end of the picture.” The disbelieving wolf still continues to verbally vent his rage, not noticing that the iris out is closing upon him rapidly. The black circle closes upon his extended arm, still holding the knife, and traps it fast on the audience side of the theater screen, also shutting out the sound of the wolf’s protesting dialogue. Blackie saunters by along our side of the screen, pulling a wagon marked “Scrap metal drive”. “Are you kiddin’?” remarks Blackie, smacking the wolf’s arm with a large mallet, causing his hand to drop the knife into Blackie’s wagom. Blackie hauls away for an exit, leaving the wolf’s arm hanging limply from the iris, as the scene fades out.

Blackie is all tied up on a platter, but requests a last wish – a smoke. Producing a pack with one hand miraculous free of the bonds, Blackie pops out from the carton one cigarette ten times taller than the pack, remarking “King Size.” As Blackie busies himself with the smoking, the wolf steps outside to sharpen his carving knife on a grinding wheel. Behind him, the cabin is seen, black smoke billowing from every crack and door and window frame. Suddenly, the whole house ignites in flame, is reduced to charred matchsticks without even so much as a sound effect, and crumbles, leaving only an unharmed Blackie standing next to the remaining stones of the fireplace. The horrified wolf charges Blackie with his knife, lifts Blackie by the throat, and proclaims he will cut Blackie to ribbons. Blackie points out, “Ya ain’t got time. This is the end of the picture.” The disbelieving wolf still continues to verbally vent his rage, not noticing that the iris out is closing upon him rapidly. The black circle closes upon his extended arm, still holding the knife, and traps it fast on the audience side of the theater screen, also shutting out the sound of the wolf’s protesting dialogue. Blackie saunters by along our side of the screen, pulling a wagon marked “Scrap metal drive”. “Are you kiddin’?” remarks Blackie, smacking the wolf’s arm with a large mallet, causing his hand to drop the knife into Blackie’s wagom. Blackie hauls away for an exit, leaving the wolf’s arm hanging limply from the iris, as the scene fades out.

The Herring Murder Mystery (Screen Gems/Columbia, 11/30/43 – Don Roman, dir.) – This bizarre little nearly-lost gem, absent from the present holdings of the Columbia vaults, begins in the framework of a film-noir picture, in a small fish caning plant along a dark waterfront. The shrill screams of a small herring are heard from inside, and the camera dissolves to the interior of the cannery, where we witness the herring, clutched in a human hand, being submerged into a barrel of vinegar, placed into a can, and sealed shut within, by a lid reading “marinated herring.” A mild-mannered little man has committed the deed, and moans at his shameful way of making a living – a trade that makes him feel like a common murderer. That night, as he leaves the plant, walking along fog-shrouded wharves, the man can swear he is being followed. He alters his gait to tap out some dance steps, but is sure the “echo’ sounds don’t match his feet. He begins to run, into a blanket of fog, and collides with something in the mist. A cultured baritone voice asks if he has a match. The man produces one – illuminating his present location standing inside a trash can, and standing next to the can, a six-foot tall fish dressed in the outfit of an English detective. The fish inquires why the little man isn’t afraid of walking in the darkness, what with the “Marinator” on the loose. The fish presents his business card – Sherlock Shad, homicide division. Shad tells the man that he is investigating 500 cases of herring marination in one week – and all right in this vicinity. The little man’s nervousness rises, so much so, he is unable to hold the business card still in his hand. Suddenly, another huge fish dressed in a policeman’s outfit (a “carp”, per chance?), appears behind the trash can, and slaps the lid shut on the little man. The carp and shad take hold of the handles of the trash can, and heave it into the ocean.

The Herring Murder Mystery (Screen Gems/Columbia, 11/30/43 – Don Roman, dir.) – This bizarre little nearly-lost gem, absent from the present holdings of the Columbia vaults, begins in the framework of a film-noir picture, in a small fish caning plant along a dark waterfront. The shrill screams of a small herring are heard from inside, and the camera dissolves to the interior of the cannery, where we witness the herring, clutched in a human hand, being submerged into a barrel of vinegar, placed into a can, and sealed shut within, by a lid reading “marinated herring.” A mild-mannered little man has committed the deed, and moans at his shameful way of making a living – a trade that makes him feel like a common murderer. That night, as he leaves the plant, walking along fog-shrouded wharves, the man can swear he is being followed. He alters his gait to tap out some dance steps, but is sure the “echo’ sounds don’t match his feet. He begins to run, into a blanket of fog, and collides with something in the mist. A cultured baritone voice asks if he has a match. The man produces one – illuminating his present location standing inside a trash can, and standing next to the can, a six-foot tall fish dressed in the outfit of an English detective. The fish inquires why the little man isn’t afraid of walking in the darkness, what with the “Marinator” on the loose. The fish presents his business card – Sherlock Shad, homicide division. Shad tells the man that he is investigating 500 cases of herring marination in one week – and all right in this vicinity. The little man’s nervousness rises, so much so, he is unable to hold the business card still in his hand. Suddenly, another huge fish dressed in a policeman’s outfit (a “carp”, per chance?), appears behind the trash can, and slaps the lid shut on the little man. The carp and shad take hold of the handles of the trash can, and heave it into the ocean.

The trash can drifts slowly to the bottom of the bay. The little man pops his head out, but is prevented from leaving by an octopus, who takes hold of the lip of the trash can with numerous of its tentacles, and acts as a parachute to slowly lower the man to just above a chair, where he is dumped out by the octopus. The chair is the witness stand of an undersea courtroom, where the man finds himself “on trial for his life”. Suddenly, however, this dark-mood scene drastically switches gears, and the trial becomes a dead-on parody of a popular radio quiz show of the day, “Information, Please”, with a Judge emcee who gives out sets of encyclopedias to listeners who send in questions that stump a resident panel of experts. The octopus doubles as court reporter, as the judge poses questions about the charges of the case to those in the courtroom, in the form of seeking three right answers out of four, etc. A shark acts as prosecuting attorney, and engages in intense cross-examination of the little man, accusing him of the crime of marination. The man is a terrible witness, and frequently reacts with reflexive admissions of knowledge or guilt, followed by defensive switches of testimony to denials. Every time he does so, the fish jury breaks into a sing-song about “There’s something on the end of the hook – but it’s shad roe to me” The judge looks up shad roe in a dictionary of slang, inferring “falsehood, or a lot of baloney.” (The sing-song is a rewording of an actual radio jingle of the day, which I have only heard in one radio transcription. I do not even recall if it was from an “Information, Please” broadcast, nor can recall the product being advertised, but remember that the performance was so accurate to the cartoon, it even included a metallic clunky-note following the lyric, practically identical between jingle and cartoon Anyone who can identify the mystery jungle should really be entitled to a set of the judge’s encyclopedias.) The shark asks where the witness was on the night of June 13th. The little man responnds with lip movements and gestures as if he is giving significant testimony, but not a sound is heard.

The trash can drifts slowly to the bottom of the bay. The little man pops his head out, but is prevented from leaving by an octopus, who takes hold of the lip of the trash can with numerous of its tentacles, and acts as a parachute to slowly lower the man to just above a chair, where he is dumped out by the octopus. The chair is the witness stand of an undersea courtroom, where the man finds himself “on trial for his life”. Suddenly, however, this dark-mood scene drastically switches gears, and the trial becomes a dead-on parody of a popular radio quiz show of the day, “Information, Please”, with a Judge emcee who gives out sets of encyclopedias to listeners who send in questions that stump a resident panel of experts. The octopus doubles as court reporter, as the judge poses questions about the charges of the case to those in the courtroom, in the form of seeking three right answers out of four, etc. A shark acts as prosecuting attorney, and engages in intense cross-examination of the little man, accusing him of the crime of marination. The man is a terrible witness, and frequently reacts with reflexive admissions of knowledge or guilt, followed by defensive switches of testimony to denials. Every time he does so, the fish jury breaks into a sing-song about “There’s something on the end of the hook – but it’s shad roe to me” The judge looks up shad roe in a dictionary of slang, inferring “falsehood, or a lot of baloney.” (The sing-song is a rewording of an actual radio jingle of the day, which I have only heard in one radio transcription. I do not even recall if it was from an “Information, Please” broadcast, nor can recall the product being advertised, but remember that the performance was so accurate to the cartoon, it even included a metallic clunky-note following the lyric, practically identical between jingle and cartoon Anyone who can identify the mystery jungle should really be entitled to a set of the judge’s encyclopedias.) The shark asks where the witness was on the night of June 13th. The little man responnds with lip movements and gestures as if he is giving significant testimony, but not a sound is heard.

In a gag Tex Avery might have wished he came up with, the judge and shark exchange looks anf shrug their shoulders, and the judge asks, “Is something wrong with the sound track?” The camera pans left, revealing the film sprockets to one side of the picture image, and the jagged soundtrack line between them. The jagged line bends itself into the shape of an equally-jagged face, which enters the picture area and speaks to the judge in irritated fashion, “No, nothing’s wrong with the sound track”, then juts further into the picture to address the little man face to face, “Just speak a little more distinctly, stupid!” Finally, after a rash of piscatorial puns demonstrated by additional witnesses, the shark decides to reconstruct the crime, using the little man as a herring in the marination barrel. Before the man can face the dip, the jingle begins again from the jury box. The man repeatedly yells “stop”, and begs to confess to anything rather than have to listen to that song again. Just as the judge is about to pronounce sentence, a call is heard from the evidence table, demanding that the prisoner be let go. It is the herring we saw in the first shot, out of the can. It turns out that she actually likes the marination – which another cartoon might have referred to as being “pickled” – a synonym for intoxication. The judge admits that even he likes to be marinated too, bangs his gavel, and states, “Case dismissed,” The jury, however, still can’t resist singing their song, and the gavel bang flips the top of the judge’s bench over, revealing it to be built on the back side of a large sardine-style can. To avoid hearing the jingle once more, the judge leaps into the open side of his can, and unrolls the metal lid with its key to cover himself in. On the unrolled lid appear the words “The End”, leading to a dissolve to the Columbia logo.

In a gag Tex Avery might have wished he came up with, the judge and shark exchange looks anf shrug their shoulders, and the judge asks, “Is something wrong with the sound track?” The camera pans left, revealing the film sprockets to one side of the picture image, and the jagged soundtrack line between them. The jagged line bends itself into the shape of an equally-jagged face, which enters the picture area and speaks to the judge in irritated fashion, “No, nothing’s wrong with the sound track”, then juts further into the picture to address the little man face to face, “Just speak a little more distinctly, stupid!” Finally, after a rash of piscatorial puns demonstrated by additional witnesses, the shark decides to reconstruct the crime, using the little man as a herring in the marination barrel. Before the man can face the dip, the jingle begins again from the jury box. The man repeatedly yells “stop”, and begs to confess to anything rather than have to listen to that song again. Just as the judge is about to pronounce sentence, a call is heard from the evidence table, demanding that the prisoner be let go. It is the herring we saw in the first shot, out of the can. It turns out that she actually likes the marination – which another cartoon might have referred to as being “pickled” – a synonym for intoxication. The judge admits that even he likes to be marinated too, bangs his gavel, and states, “Case dismissed,” The jury, however, still can’t resist singing their song, and the gavel bang flips the top of the judge’s bench over, revealing it to be built on the back side of a large sardine-style can. To avoid hearing the jingle once more, the judge leaps into the open side of his can, and unrolls the metal lid with its key to cover himself in. On the unrolled lid appear the words “The End”, leading to a dissolve to the Columbia logo.

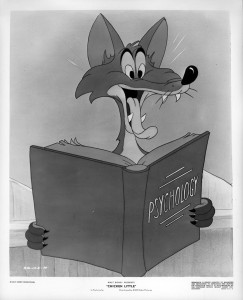

Chicken Little (Disney/RKO, 12/17/43 – Clyde Geronimi, dir.) – Another tour de force for the busy Frank Graham, who provides voices for the entire cast, including reuse of two familiar ones – his gruff Crow and Wolf voice provides the vocal tones for Foxy Loxy, and his Fox voice used in the Columbia series appears as the respective voices of several miscellaneous members of the barnyard poultry community. This somewhat twisted retelling of the tale was originally released in the “searchlight titles” series of one-shots produced during ‘43 and ‘44, with a definite wartime message angle intended, though underplayed without any direct references to Hitler or the conflict, so that the film was able to be theatrically re-released without its wartime titling, and pass as a regular though somewhat unsettling episode.

Chicken Little (Disney/RKO, 12/17/43 – Clyde Geronimi, dir.) – Another tour de force for the busy Frank Graham, who provides voices for the entire cast, including reuse of two familiar ones – his gruff Crow and Wolf voice provides the vocal tones for Foxy Loxy, and his Fox voice used in the Columbia series appears as the respective voices of several miscellaneous members of the barnyard poultry community. This somewhat twisted retelling of the tale was originally released in the “searchlight titles” series of one-shots produced during ‘43 and ‘44, with a definite wartime message angle intended, though underplayed without any direct references to Hitler or the conflict, so that the film was able to be theatrically re-released without its wartime titling, and pass as a regular though somewhat unsettling episode.

As the story opens, Foxy Loxy eyes a bustling barnyard community from over a high fence. There is danger to him if he enters, including a farmer’s shotgun. But the fox has bigger ideas – how to “influence the masses” and have them come to him. “Why should I settle for one, when I can have them all”, he tells the narrator. For that, he relies upon a book titled “Psychology”. Some studio references and possibly storyboard drawings suggest that original concept was to have him reading ideas expressed in Hitler’s book, “Mein Kampf”, but this idea was abandoned by the time of filming – after all, it had already been done anyway, in the competing Columbia cartoon from the preceding year, “Cholly Polly”. The book first instructs, “Aim for the least intelligent.” The obvious choice is Chicken Little, a simple-minded fowl who spends his time playing with a yo-yo. Another page of the book instructs, “If you tell a lie, don’t tell a little one. Tell a big one.” Foxy spots a wooden sign on a tree, advertising a Madame Izan, astrologist. The sign is painted blue, and features images of several stars. The fox breaks off a chunk of the sign depicting a star, places it into a slingshot, takes careful aim, and beans Chicken Little on the back of the head with it. Then, he whispers to Chicken Little through a small hole in the fence. “This is the voice of doom speaking. Special bulletin. Flash. The sky is falling. A piece of it just hit you on the head. Now be calm. Don’t get panicky – – RUN FOR YOUR LIFE!!” Chicken Little reports the incident in terror to the others of the community. Many are instantly convinced by Little’s evidence of the star chunk retrieved from the ground. But barnyard boss Cocky Locky intervenes, examining the object which struck Little, and concluding that it is nothing more than a hunk of wood. He tosses the wood chunk back over the fence, clunking the fox on the head with it. “Guess that’s the end of your stew”, interjects the narrator to Foxy.

The Fox begs to differ. Again quoting from the book, he reads, “Undermine the faith of the masses in their leaders.” The fox begins whispering into other knotholes of the fence to other sectors of the community, spreading the rumors that Cocky Locky is displaying “totalitarian tendencies” and dictating to them. What would happen if he is wrong? They should be able to decide for themselves if the sky is falling. To an inebriated club of ducks, the Fox whispers that Cocky Locky has been wallowing in mash, and hasn’t got all his marbles. The rumors spread, and the community begins to comment that Cocky is “not the cock of the walk anymore.” Reading again from the book, the Fox next follows the recommendation, “By the use of flattery, insignificant people can be made to look upon themselves as born leaders.” So, he whispers again to Chicken Little, “Now’s your chance, kid. They’ll listen to ya now. You were born to be a leader. Go to it.” Little steps high onto a rock, announcing he will be the community’s new leader, and tell them what to do. “Don’t listen to that pipsqueak”, responds Cocky Locky, insisting the sky isn’t falling.” “It is too”, shouts back Little. “If the sky is falling, why doesn;t it hit me on the head?” demands Cocky. The confused public doesn’t know who to side with, until Foxy takes aim with his slingshot at Cocky’s head with the same wooden star. One clunk, and Cocky is out cold – while the public clamors to Little to advise them what to do. The wolf’s whisper is again heard by Little – “Run to the cave.” Little repeats the advice to the community, resulting in a stampede through the fence gate, leaving the whole community out in the open. The fox posts a trail of signs leading “To the cave”. and all the poultry race inside his own home. “Dinner is served”, says Foxy, donning a restaurant bib. He himself darts into the cave, blocking up the entrance from inside with a stone, and hanging upon it a sign reading “In to lunch.” The narrator, however, calmly assures us, “Don’t worry folks. This all turns out all right.” Yet, when we dissolve to an interior view of the cave, Foxy is smacking his lips, displaying a full belly, and remarking “Dee-licious.” He takes a last suck off a wish bone, then plants the bone upside down in the ground, amidst a patch of earth dotted with wishbones like the stones of a graveyard. The shocked narrator responds, “Hey, wat a minute. This isn’t right. That’s not the way it ends in my book.” Toying with Chicken Little’s yo-yo, its original owner nowhere remaining to be found, the Fox directly addresses the narrator. “Oh yeah? Don’t believe everything you read, brother!” On this sobering, pointed, yet perfect un-Disney-like curtain line, we iris out on the rising and falling yo-yo, to black.

The Fox begs to differ. Again quoting from the book, he reads, “Undermine the faith of the masses in their leaders.” The fox begins whispering into other knotholes of the fence to other sectors of the community, spreading the rumors that Cocky Locky is displaying “totalitarian tendencies” and dictating to them. What would happen if he is wrong? They should be able to decide for themselves if the sky is falling. To an inebriated club of ducks, the Fox whispers that Cocky Locky has been wallowing in mash, and hasn’t got all his marbles. The rumors spread, and the community begins to comment that Cocky is “not the cock of the walk anymore.” Reading again from the book, the Fox next follows the recommendation, “By the use of flattery, insignificant people can be made to look upon themselves as born leaders.” So, he whispers again to Chicken Little, “Now’s your chance, kid. They’ll listen to ya now. You were born to be a leader. Go to it.” Little steps high onto a rock, announcing he will be the community’s new leader, and tell them what to do. “Don’t listen to that pipsqueak”, responds Cocky Locky, insisting the sky isn’t falling.” “It is too”, shouts back Little. “If the sky is falling, why doesn;t it hit me on the head?” demands Cocky. The confused public doesn’t know who to side with, until Foxy takes aim with his slingshot at Cocky’s head with the same wooden star. One clunk, and Cocky is out cold – while the public clamors to Little to advise them what to do. The wolf’s whisper is again heard by Little – “Run to the cave.” Little repeats the advice to the community, resulting in a stampede through the fence gate, leaving the whole community out in the open. The fox posts a trail of signs leading “To the cave”. and all the poultry race inside his own home. “Dinner is served”, says Foxy, donning a restaurant bib. He himself darts into the cave, blocking up the entrance from inside with a stone, and hanging upon it a sign reading “In to lunch.” The narrator, however, calmly assures us, “Don’t worry folks. This all turns out all right.” Yet, when we dissolve to an interior view of the cave, Foxy is smacking his lips, displaying a full belly, and remarking “Dee-licious.” He takes a last suck off a wish bone, then plants the bone upside down in the ground, amidst a patch of earth dotted with wishbones like the stones of a graveyard. The shocked narrator responds, “Hey, wat a minute. This isn’t right. That’s not the way it ends in my book.” Toying with Chicken Little’s yo-yo, its original owner nowhere remaining to be found, the Fox directly addresses the narrator. “Oh yeah? Don’t believe everything you read, brother!” On this sobering, pointed, yet perfect un-Disney-like curtain line, we iris out on the rising and falling yo-yo, to black.

What’s Cookin’, Doc? (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 1/1/44 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – For a long time, this tended to be one of the most poorly preserved, and least seen, Bugs cartoons of the 1940’s. Today, it is finally available in some sources from respectable restorations. The film is actually a blatant “cheater”, not only lifting a sizeable film clip from Friz Freleng’s “Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt”, but also stock shots from the live-action original version of “A Star Is Born” and/or other newsreel footage. Out of this mess of film that might have turned into another screen epic by Daffy Duck from scraps on the cutting room floor, Clampett constructs a subplot which takes until about the one-third mark of the film to materialize, in which our favorite wabbit again demonstrates his complete consciousness of his professional career on the screen, attending the ceremony for the presentation of the Academy Awards at the Biltmore Hotel. Seated at a banquet table on a plush red-cushioned seat (nearly the only background appearing in the cartoon), Bugs begins his appearance by directly confiding with the audience that his award is “in the bag”, then engages in hospitable greetings to other passing luminaries of the screen (all of whom pass his table behind the range of the camera so as to be out of view). We know, however, to whom Bugs is speaking, due to Bugs’s name-dropping, and engaging in visual and vocal impressions of the stars he addresses. He thus impersonates Katherine Hepburn, Edward G. Robinson, Jerry Colonna, and Bing Crosby. Oddly, it turns out Bugs is not waiting for the awarding for best animated short subject, but actually believes he is in contention for the Oscar for Best Actor (a category for which no animated character has ever even been nominated). Didn’t Bugs check out the nominations first – or does he believe the process is open enrollment for qualification? C’mon, Bugs, you’ve been kicking around Hollywood for five years in star form – you should know the drill by now.

What’s Cookin’, Doc? (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 1/1/44 – Robert Clampett, dir.) – For a long time, this tended to be one of the most poorly preserved, and least seen, Bugs cartoons of the 1940’s. Today, it is finally available in some sources from respectable restorations. The film is actually a blatant “cheater”, not only lifting a sizeable film clip from Friz Freleng’s “Hiawatha’s Rabbit Hunt”, but also stock shots from the live-action original version of “A Star Is Born” and/or other newsreel footage. Out of this mess of film that might have turned into another screen epic by Daffy Duck from scraps on the cutting room floor, Clampett constructs a subplot which takes until about the one-third mark of the film to materialize, in which our favorite wabbit again demonstrates his complete consciousness of his professional career on the screen, attending the ceremony for the presentation of the Academy Awards at the Biltmore Hotel. Seated at a banquet table on a plush red-cushioned seat (nearly the only background appearing in the cartoon), Bugs begins his appearance by directly confiding with the audience that his award is “in the bag”, then engages in hospitable greetings to other passing luminaries of the screen (all of whom pass his table behind the range of the camera so as to be out of view). We know, however, to whom Bugs is speaking, due to Bugs’s name-dropping, and engaging in visual and vocal impressions of the stars he addresses. He thus impersonates Katherine Hepburn, Edward G. Robinson, Jerry Colonna, and Bing Crosby. Oddly, it turns out Bugs is not waiting for the awarding for best animated short subject, but actually believes he is in contention for the Oscar for Best Actor (a category for which no animated character has ever even been nominated). Didn’t Bugs check out the nominations first – or does he believe the process is open enrollment for qualification? C’mon, Bugs, you’ve been kicking around Hollywood for five years in star form – you should know the drill by now.

The award presentation begins. Bugs reacts to the speaker’s words of praise regarding the winner’s abilities before naming him, responding with demonstrations of his acting skills, such as romancing a carrot as a great lover, and performing character roles (morphing into a Frankenstein’s rabbit). Bugs extends his arms to the shadow of the outstretched arms of the speaker holding the Oscar statuette, only to have his hopes dashed in a heartbeat by the utterance of the winner’s name – James Cagney. Bugs gasps for air, recovers, yells “STOP!” to the crowd, then claims he is the victim of “sabota-gee”. He demands a recount, and leaves the decision up to those in the room. To ensure reinforcement in the minds of the onlookers as to his acting skills, Bugs pulls down from the ceiling a projection screen, and produces several reels of “my best scenes” which he just happens to carry with him for such an emergency. He tosses the reels toward the camera to an unseen projectionist, and calls out, “O.K., Smokey, roll ‘em.” (Interesting nickname for a projectionist, as anyone who smoked in a 1940’s projection booth would be an obvious hazard for a nitrate fire.) A picture flashes on the screen – not one Bugs expected. An image of an antlered male deer is seen, surrounded by the letters “Stag Reel”, and the sound of harem music is heard. (Thus was 40’s parlance for girlie porn – or as close to it as criminal codes of the period would allow.) “HEYYY!!!” shouts Bugs, leaping in front of the screen in a desperate attempt to block the image. The projection stops, and Bugs apologizes with embarrassment, “Heh heh, wrong picture.” Finally, the right film comes on, eating up about a minute and a half. When the scene returns to the awards ballroom, Bugs is beating a large drum, on which is written the words, “Let Bugs have it” and “Give it to Bugs”. Bugs also tosses free cigars to everyone in the audience – probably whether they smoke or not. The audience does indeed let Bugs “have it”, burying him in a pile of tossed tomatoes and various other vegetable and fruit. Bugs rises from the pile with a stack of the produce piled high on his head, and impersonates Carmen Miranda and her tutti-frutti hats. Bugs then gets clunked in the face by a tossed golden statue. No, it is not an Oscar, but a “booby prize” statue shaped just like Bugs. Bugs can’t tell the difference, and embraces the statue, proclaiming his love of the award, and promising that he will even take the statue to bed with him every night. In a scene that surprisingly did not raise the censor’s ire, the statue comes to life, and responds, in a male voice, “Do you mean it?”, kisses Bugs in the rabbit’s typical style on the lips for a prolonged smack, then strikes a provocative pose for the fade out, as the puzzled Bugs looks on.

The award presentation begins. Bugs reacts to the speaker’s words of praise regarding the winner’s abilities before naming him, responding with demonstrations of his acting skills, such as romancing a carrot as a great lover, and performing character roles (morphing into a Frankenstein’s rabbit). Bugs extends his arms to the shadow of the outstretched arms of the speaker holding the Oscar statuette, only to have his hopes dashed in a heartbeat by the utterance of the winner’s name – James Cagney. Bugs gasps for air, recovers, yells “STOP!” to the crowd, then claims he is the victim of “sabota-gee”. He demands a recount, and leaves the decision up to those in the room. To ensure reinforcement in the minds of the onlookers as to his acting skills, Bugs pulls down from the ceiling a projection screen, and produces several reels of “my best scenes” which he just happens to carry with him for such an emergency. He tosses the reels toward the camera to an unseen projectionist, and calls out, “O.K., Smokey, roll ‘em.” (Interesting nickname for a projectionist, as anyone who smoked in a 1940’s projection booth would be an obvious hazard for a nitrate fire.) A picture flashes on the screen – not one Bugs expected. An image of an antlered male deer is seen, surrounded by the letters “Stag Reel”, and the sound of harem music is heard. (Thus was 40’s parlance for girlie porn – or as close to it as criminal codes of the period would allow.) “HEYYY!!!” shouts Bugs, leaping in front of the screen in a desperate attempt to block the image. The projection stops, and Bugs apologizes with embarrassment, “Heh heh, wrong picture.” Finally, the right film comes on, eating up about a minute and a half. When the scene returns to the awards ballroom, Bugs is beating a large drum, on which is written the words, “Let Bugs have it” and “Give it to Bugs”. Bugs also tosses free cigars to everyone in the audience – probably whether they smoke or not. The audience does indeed let Bugs “have it”, burying him in a pile of tossed tomatoes and various other vegetable and fruit. Bugs rises from the pile with a stack of the produce piled high on his head, and impersonates Carmen Miranda and her tutti-frutti hats. Bugs then gets clunked in the face by a tossed golden statue. No, it is not an Oscar, but a “booby prize” statue shaped just like Bugs. Bugs can’t tell the difference, and embraces the statue, proclaiming his love of the award, and promising that he will even take the statue to bed with him every night. In a scene that surprisingly did not raise the censor’s ire, the statue comes to life, and responds, in a male voice, “Do you mean it?”, kisses Bugs in the rabbit’s typical style on the lips for a prolonged smack, then strikes a provocative pose for the fade out, as the puzzled Bugs looks on.

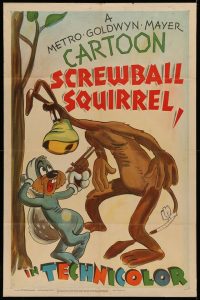

Screwball Squirrel (MGM, 4/1/44 – Tex Avery, dir.) – One of the most self-conscious openings in Tex Avery’s career begins this film. A placid forest scene focuses on the dancing nut gathering of a realistic and cute little gray squirrel, drawn similar to the classic style of late 1930’s MGM cartoons. He encounters a larger red squirrel leaning against a tree – the premiere appearance of Avery’s infamous troublemaker, Screwy Squirrel. Screwy asks “What kind of a picture is this gonna be anyway?” The gray squirrel, in a cutesie falsetto voice, replies, “I play the lead in this picture, and my name is Sammy Squirrel, and the story is all about me and my cute furry friends of the forest.” Screwy has heard enough, remarking (without the slightest notice from Sammy) “Oh brother, not that. Not that!” In iconoclastic revolt against the old MGM style (a principle near and dear to Avery’s heart), Screwy leads Sammy behind a tree, and in unseen action, depicted only by shock vibrations, dust clouds, and a shower of stars, whomps the daylights out of Sammy. Screwy emerges to our view, dusting off his hands, then addresses us. “You wouldn’t’ve liked the story anyway. The funny stuff will start as soon as the phone rings.” A ring from a pay phone booth puts Screwy in touch with a dimwitted dog named Meathead, whom Screwy challenges to break from his traditional occupation as pedigreed bird dog to chase squirrels. This he does by calling Meathead yellow and too slow to catch squirrels, then closing the door of the phone booth to mute the sound of a quite-visible voicing of a raspberry into the phone mouthpiece. Meathead appears at the door of the phone booth in an instant, totally furious. “I knew that’d get him”, remarks Screwy to the camera.

Screwball Squirrel (MGM, 4/1/44 – Tex Avery, dir.) – One of the most self-conscious openings in Tex Avery’s career begins this film. A placid forest scene focuses on the dancing nut gathering of a realistic and cute little gray squirrel, drawn similar to the classic style of late 1930’s MGM cartoons. He encounters a larger red squirrel leaning against a tree – the premiere appearance of Avery’s infamous troublemaker, Screwy Squirrel. Screwy asks “What kind of a picture is this gonna be anyway?” The gray squirrel, in a cutesie falsetto voice, replies, “I play the lead in this picture, and my name is Sammy Squirrel, and the story is all about me and my cute furry friends of the forest.” Screwy has heard enough, remarking (without the slightest notice from Sammy) “Oh brother, not that. Not that!” In iconoclastic revolt against the old MGM style (a principle near and dear to Avery’s heart), Screwy leads Sammy behind a tree, and in unseen action, depicted only by shock vibrations, dust clouds, and a shower of stars, whomps the daylights out of Sammy. Screwy emerges to our view, dusting off his hands, then addresses us. “You wouldn’t’ve liked the story anyway. The funny stuff will start as soon as the phone rings.” A ring from a pay phone booth puts Screwy in touch with a dimwitted dog named Meathead, whom Screwy challenges to break from his traditional occupation as pedigreed bird dog to chase squirrels. This he does by calling Meathead yellow and too slow to catch squirrels, then closing the door of the phone booth to mute the sound of a quite-visible voicing of a raspberry into the phone mouthpiece. Meathead appears at the door of the phone booth in an instant, totally furious. “I knew that’d get him”, remarks Screwy to the camera.

A wide array of Avery violence ensues, with several instances of audience awareness and consciousness of the screen medium. A chase begins to freeze and repeat itself as the musical strains of the William Tell Overture catch and repeat a passage over and over. Screwy breaks out of the repeating cycle, shrugging his shoulders to the camera, and steps over to a record player just offscreen, adjusting the needle to skip past an obstruction in the record groove providing the music, then rejoins Meathead in the chase. In another sequence, Screwy waits, poised with a baseball bat at the end of a hollow log. Before entering the other end of the log, Meathead calls out to Screwy, “Ya ain’t gonna hit me again, are ya?” Screwy responds only by addressing the audience again, sarcastically laughing, “Now he oughta know better than that.” Screwy pauses after another gag, attempting to remember what he is supposed to do next to the dog. “What is the next scene?” He reaches down to one corner of the background drawing, lifting it like the page of a book, revealing a moving image of himself underneath, standing in the entrance of a hollow tree carrying a club. “Oh yeah”, remarks Screwy, then moves on to just that scene. A later scene on board a beached ship at the waterfront allows Screwy to induce seasickness in Meathead by moving a painting of sea waves up and down outside a porthole. Screwy confides to us: “Imagine that stoop falling for the old seasick gag”, then turns the picture toward himself. “All I did was move it up and down like this.” Screwy suddenly gets woozy, turns green, and burps, then disappears from the shot, leaving an apologetic sign in his place, reading, “One moment please.” After Meathead endures yet another clobbering in a rolling barrel, the dog addresses the film’s producers directly. “I’ve had enough. Stop the picture. End the thing, will ya?” The iris slowly begins to close. “No no, wait a minute”, protests Screwy, stepping into the closing circle and pushing it back open again. Screwy declares he’s a sport, and challenges Meathead to a game of hide and seek, where “If you find me, you can have me.” Meathead closes his eyes and counts to 100 against a tree. Somehow, Screwy gets Meathead and the tree placed upon a railroad track. A train collides with them, carrying away Meathead on the cowcatcher. Meathead, unaware where he is, completes his count, then turns to step away, shouting, “Here I come, ready or not.” He steps out in front of the still-moving train, and the sounds of disastrous results are heard out of frame by ourselves and Screwy. “Well, that’s the end of him”, states Screwy to us, but adds, “You people want in on a little secret? You wanna know how I fooled him all through the picture?” The camera pulls back to reveal another identical Screwy. “We was twins all the time”, they both laugh. The camera suddenly pulls further back, revealing two Meatheads, who take hold of the squirrels. “So wuz we”, laugh the dogs. From nowhere, Sammy Squirrel appears between them at their feet. “My cartoon would have been cuter”, says Sammy. “Oh, brother, not that!”, chime both dogs and squirrels in unison, and all four gang up on Sammy for a final fight cloud, and the fade out.

A wide array of Avery violence ensues, with several instances of audience awareness and consciousness of the screen medium. A chase begins to freeze and repeat itself as the musical strains of the William Tell Overture catch and repeat a passage over and over. Screwy breaks out of the repeating cycle, shrugging his shoulders to the camera, and steps over to a record player just offscreen, adjusting the needle to skip past an obstruction in the record groove providing the music, then rejoins Meathead in the chase. In another sequence, Screwy waits, poised with a baseball bat at the end of a hollow log. Before entering the other end of the log, Meathead calls out to Screwy, “Ya ain’t gonna hit me again, are ya?” Screwy responds only by addressing the audience again, sarcastically laughing, “Now he oughta know better than that.” Screwy pauses after another gag, attempting to remember what he is supposed to do next to the dog. “What is the next scene?” He reaches down to one corner of the background drawing, lifting it like the page of a book, revealing a moving image of himself underneath, standing in the entrance of a hollow tree carrying a club. “Oh yeah”, remarks Screwy, then moves on to just that scene. A later scene on board a beached ship at the waterfront allows Screwy to induce seasickness in Meathead by moving a painting of sea waves up and down outside a porthole. Screwy confides to us: “Imagine that stoop falling for the old seasick gag”, then turns the picture toward himself. “All I did was move it up and down like this.” Screwy suddenly gets woozy, turns green, and burps, then disappears from the shot, leaving an apologetic sign in his place, reading, “One moment please.” After Meathead endures yet another clobbering in a rolling barrel, the dog addresses the film’s producers directly. “I’ve had enough. Stop the picture. End the thing, will ya?” The iris slowly begins to close. “No no, wait a minute”, protests Screwy, stepping into the closing circle and pushing it back open again. Screwy declares he’s a sport, and challenges Meathead to a game of hide and seek, where “If you find me, you can have me.” Meathead closes his eyes and counts to 100 against a tree. Somehow, Screwy gets Meathead and the tree placed upon a railroad track. A train collides with them, carrying away Meathead on the cowcatcher. Meathead, unaware where he is, completes his count, then turns to step away, shouting, “Here I come, ready or not.” He steps out in front of the still-moving train, and the sounds of disastrous results are heard out of frame by ourselves and Screwy. “Well, that’s the end of him”, states Screwy to us, but adds, “You people want in on a little secret? You wanna know how I fooled him all through the picture?” The camera pulls back to reveal another identical Screwy. “We was twins all the time”, they both laugh. The camera suddenly pulls further back, revealing two Meatheads, who take hold of the squirrels. “So wuz we”, laugh the dogs. From nowhere, Sammy Squirrel appears between them at their feet. “My cartoon would have been cuter”, says Sammy. “Oh, brother, not that!”, chime both dogs and squirrels in unison, and all four gang up on Sammy for a final fight cloud, and the fade out.

Batty Baseball (MGM, 4/22/44 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Perhaps the most unique gag of this film involves its opening sequence. A title card flashes on the screen, naming only the film title and Avery’s director credit, for about three seconds. Suddenly, we seem to be in the midst of the action, without even so much as a fade in. Batters are batting. Fielders are fielding. Players scramble like ants all over the field. Someone is out at the plate by way of the catcher bashing him over the head with a bat. A runner races for home, and begins to slide – but freezes in mid-action. He faces the camera, and addresses the narrator. “Hey, wait a minute. Didn’t ya forget somethin’? Who made this picture? How ‘bout the MGM title, the lion roar, and all that kinda stuff?” The narrator responds, “Oh, I guess I got too excited. I’m sorry, boys.” So, in fades the lion, and the missing animator’s credits!

Batty Baseball (MGM, 4/22/44 – Tex Avery, dir.) – Perhaps the most unique gag of this film involves its opening sequence. A title card flashes on the screen, naming only the film title and Avery’s director credit, for about three seconds. Suddenly, we seem to be in the midst of the action, without even so much as a fade in. Batters are batting. Fielders are fielding. Players scramble like ants all over the field. Someone is out at the plate by way of the catcher bashing him over the head with a bat. A runner races for home, and begins to slide – but freezes in mid-action. He faces the camera, and addresses the narrator. “Hey, wait a minute. Didn’t ya forget somethin’? Who made this picture? How ‘bout the MGM title, the lion roar, and all that kinda stuff?” The narrator responds, “Oh, I guess I got too excited. I’m sorry, boys.” So, in fades the lion, and the missing animator’s credits!

Another card fades in, stating “Any similarity between the title of this pucture and the story that follows is purely an accident.” Our scene fades in at a stadium named “W.C. Field”. A superimposed sign appears over the lower portion of the screen, informing us, “The guy who thought of this corny gag isn’t with us any more.” The game commences between the Yankee Doodlers and the Draft Dodgers – though it’s never quite clear which team is which. One team is down to two players – its putcher and catcher – due to the draft, all other positions on the field replaced by small signs reading “1A”. The pitcher, however, wears on the back of his uniform the number “4F”. Comparative to many Avery shorts, this one always feels like it is a little short on material, and ends when you think it’s just getting started. However, there are a few notable gags. A long clout hits a billboard on the fence, advertising toothpaste and a girl’s glamourous smile – knocking a tooth out of the girl in the ad picture. The pitcher retaliates with a bean ball, lined up for impact right between the eyes through a crosshair sight installed in one of the pitcher’s upraised shoes. A fan shouts the common jeering phrase, “Kill the umpire”, only to prompt the sound of a gunshot on the field, and everyone rising from their seats to provide a respectful moment of silence. The pitcher’s “beautiful curve” ball traces the outline of a shapely dame, prompting a unison wolf whistle from the spectators in the crowd. The pitcher substitutes a bowling ball, and rolls a strike to knock the batter, catcher, and umpire out of the plate area. Then an automatic pin setter lowers as in a bowling alley, to replace the players into their original positions like bowling pins. Another irate fan yells that the umpire is blind. The umpire turns to face him, wearing dark glasses and holding a white cane and a cup full of pencils to sell, replying, “Oh, I am not.” Finally, a running gag has the catcher repeatedly zipping ahead of the batter to catch the ball before it can reach the plate. On the third such instance, the batter still takes a powerful swing, and the sound of a smashing hit informs us that he made contact with something, but not the ball. The batter looks down in dismay, gritting his teeth at the disturbing sight, while the narrator announces, “We will now observe one minute of silence.” We actually don’t spend that long, as a small cloud floats upwards past a totally black screen, carrying the angel of the catcher, who holds a sign repeating the ending from “The Early Bird Dood it” reading “Sad ending, isn’t it?”

Another card fades in, stating “Any similarity between the title of this pucture and the story that follows is purely an accident.” Our scene fades in at a stadium named “W.C. Field”. A superimposed sign appears over the lower portion of the screen, informing us, “The guy who thought of this corny gag isn’t with us any more.” The game commences between the Yankee Doodlers and the Draft Dodgers – though it’s never quite clear which team is which. One team is down to two players – its putcher and catcher – due to the draft, all other positions on the field replaced by small signs reading “1A”. The pitcher, however, wears on the back of his uniform the number “4F”. Comparative to many Avery shorts, this one always feels like it is a little short on material, and ends when you think it’s just getting started. However, there are a few notable gags. A long clout hits a billboard on the fence, advertising toothpaste and a girl’s glamourous smile – knocking a tooth out of the girl in the ad picture. The pitcher retaliates with a bean ball, lined up for impact right between the eyes through a crosshair sight installed in one of the pitcher’s upraised shoes. A fan shouts the common jeering phrase, “Kill the umpire”, only to prompt the sound of a gunshot on the field, and everyone rising from their seats to provide a respectful moment of silence. The pitcher’s “beautiful curve” ball traces the outline of a shapely dame, prompting a unison wolf whistle from the spectators in the crowd. The pitcher substitutes a bowling ball, and rolls a strike to knock the batter, catcher, and umpire out of the plate area. Then an automatic pin setter lowers as in a bowling alley, to replace the players into their original positions like bowling pins. Another irate fan yells that the umpire is blind. The umpire turns to face him, wearing dark glasses and holding a white cane and a cup full of pencils to sell, replying, “Oh, I am not.” Finally, a running gag has the catcher repeatedly zipping ahead of the batter to catch the ball before it can reach the plate. On the third such instance, the batter still takes a powerful swing, and the sound of a smashing hit informs us that he made contact with something, but not the ball. The batter looks down in dismay, gritting his teeth at the disturbing sight, while the narrator announces, “We will now observe one minute of silence.” We actually don’t spend that long, as a small cloud floats upwards past a totally black screen, carrying the angel of the catcher, who holds a sign repeating the ending from “The Early Bird Dood it” reading “Sad ending, isn’t it?”

• Watch BATTY BASEBALL here.

Hare Ribbin’ (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 6/24/44 – Robert Clampett, dir.) receives an honorable mention, though perhaps not as self-referential as most. Most aware of the audience is a featured dog with a shock of red hair, who talks like Bert Gordon, “The Mad Russian” of the Eddie Cantor show, but whose hair might also suggest a cross with the frequently-used Russian dialogue routines of Danny Kaye. The dog appears in the first shot, introducing himself directly to the audience with Bert’s signature catchphrase, “How do you doooo….”, and explains he is hunting little gray rabbit, much as Elmer Fudd had done in the original “A Wild Hare”. His sniffing runs him right into the standing Bugs, and as he sniffs up Bugs’s side and into his armpit, the dog retracts, and confides again to the audience, “B. O.” (a catchphrase for Lifebuoy soap commercials, referring to body odor). Bugs again repeats a “Wild Hare” routine with the dog, but in more violent terms, providing an inquisitive description of the features of a rabbit, but physically demonstrating them with the dog in painful ways, pulling his ears, tail, etc., then tossing him bodily into a rabbit hole. The dog emerges from the hole while Bugs escapes, drumming his fingers upon the ground surface, and again confides in us as Elmer once did that “I think that was the rabbit.” The remainder of the film (about two thirds of its action) takes place underwater in a lake, which Bugs enters through a piece of repeated animation from “The Heckling Hare”, donning a bathing cap and water wings before leaping in Photography on this film must have been time-consuming for the cameraman, as the entire action of this last portion of the film is seen with cels placed under a panning surface layer of glass or celluloid to produce a rippling effect (said to often be achieved by coating the glass or cel with varying thicknesses of clear nail polish).

Hare Ribbin’ (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 6/24/44 – Robert Clampett, dir.) receives an honorable mention, though perhaps not as self-referential as most. Most aware of the audience is a featured dog with a shock of red hair, who talks like Bert Gordon, “The Mad Russian” of the Eddie Cantor show, but whose hair might also suggest a cross with the frequently-used Russian dialogue routines of Danny Kaye. The dog appears in the first shot, introducing himself directly to the audience with Bert’s signature catchphrase, “How do you doooo….”, and explains he is hunting little gray rabbit, much as Elmer Fudd had done in the original “A Wild Hare”. His sniffing runs him right into the standing Bugs, and as he sniffs up Bugs’s side and into his armpit, the dog retracts, and confides again to the audience, “B. O.” (a catchphrase for Lifebuoy soap commercials, referring to body odor). Bugs again repeats a “Wild Hare” routine with the dog, but in more violent terms, providing an inquisitive description of the features of a rabbit, but physically demonstrating them with the dog in painful ways, pulling his ears, tail, etc., then tossing him bodily into a rabbit hole. The dog emerges from the hole while Bugs escapes, drumming his fingers upon the ground surface, and again confides in us as Elmer once did that “I think that was the rabbit.” The remainder of the film (about two thirds of its action) takes place underwater in a lake, which Bugs enters through a piece of repeated animation from “The Heckling Hare”, donning a bathing cap and water wings before leaping in Photography on this film must have been time-consuming for the cameraman, as the entire action of this last portion of the film is seen with cels placed under a panning surface layer of glass or celluloid to produce a rippling effect (said to often be achieved by coating the glass or cel with varying thicknesses of clear nail polish).

Bugs engages in several costume changes, including a seductive mermaid (prompting a love-crazed reaction from the dog to the audience as he points to Bugs, “Mama! Baby! Dad!”), a restaurant maître d, and even an impersonation of Elmer Fudd in full hunting gear. The infuriated dog finally sees through all, and demands from Bugs a promised “rabbit sandwich”. Bugs follows through, producing two huge slices of bread on a patter for himself to lie between. Two versions of this film exist, one being a director’s cut that never made the screen after some final censorship. Clampett’s original unseen version provided no explanatory shot as to what Bugs is doing inside the sandwich, but the final version adds a scene where Bugs visually asides to the audience, showing us a view which the dog doesn’t see, of Bugs’ legs all scrunched up close to his body, leaving most of the bread without any meat within. The dog takes a hearty bite from the bread, and Bugs instantly screams, and fakes one of his trademark pathetic death scenes, also in the style of “A Wild Hare”. As Bugs appears to expire, the dog enters into a crying jag at what he has done, in Elmer Fudd fashion, but adds the wailing moan, “I wish I were dead.” Bugs instantly revives in his corner of the bread rinds, responding “Do you mean it?” The director’s cut and final version diverge widely here. In the final cut, Bugs hands the dog a pistol, and the dog raises it to his temple and seemingly blows his brains out. In the director’s cut, it is Bigs who raises the pistol, straight into the dog’s mouth, and pulls the trigger. Both cuts share in common the final shot, as Bugs places a lily on the chest of the fallen dog, then tiptoes away like the exit of a graceful ballerina, as the screen iris begins to close. The dog, however, is far from dead, and rises to clutch at the edges of the screen iris, pushing it back and holding it temporarily, long enough to remark to the audience, “This shouldn’t even happen to a dog.” Suddenly, the iris closes with added force, pushing back the dog’s paws, and briefly clamping upon his nose for a painful “Ow!” The Dog’s nose retracts back into the blackness, and a few underwater bubbles escape the closing circle, as the screen finally goes black.

Bugs engages in several costume changes, including a seductive mermaid (prompting a love-crazed reaction from the dog to the audience as he points to Bugs, “Mama! Baby! Dad!”), a restaurant maître d, and even an impersonation of Elmer Fudd in full hunting gear. The infuriated dog finally sees through all, and demands from Bugs a promised “rabbit sandwich”. Bugs follows through, producing two huge slices of bread on a patter for himself to lie between. Two versions of this film exist, one being a director’s cut that never made the screen after some final censorship. Clampett’s original unseen version provided no explanatory shot as to what Bugs is doing inside the sandwich, but the final version adds a scene where Bugs visually asides to the audience, showing us a view which the dog doesn’t see, of Bugs’ legs all scrunched up close to his body, leaving most of the bread without any meat within. The dog takes a hearty bite from the bread, and Bugs instantly screams, and fakes one of his trademark pathetic death scenes, also in the style of “A Wild Hare”. As Bugs appears to expire, the dog enters into a crying jag at what he has done, in Elmer Fudd fashion, but adds the wailing moan, “I wish I were dead.” Bugs instantly revives in his corner of the bread rinds, responding “Do you mean it?” The director’s cut and final version diverge widely here. In the final cut, Bugs hands the dog a pistol, and the dog raises it to his temple and seemingly blows his brains out. In the director’s cut, it is Bigs who raises the pistol, straight into the dog’s mouth, and pulls the trigger. Both cuts share in common the final shot, as Bugs places a lily on the chest of the fallen dog, then tiptoes away like the exit of a graceful ballerina, as the screen iris begins to close. The dog, however, is far from dead, and rises to clutch at the edges of the screen iris, pushing it back and holding it temporarily, long enough to remark to the audience, “This shouldn’t even happen to a dog.” Suddenly, the iris closes with added force, pushing back the dog’s paws, and briefly clamping upon his nose for a painful “Ow!” The Dog’s nose retracts back into the blackness, and a few underwater bubbles escape the closing circle, as the screen finally goes black.

NEXT WEEK: 1944 and ‘45, when we return.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

The closing line in “Who Killed Who” is actually “I dood it,” a catch phrase of comedian Red Skelton (who is alluded to in a gag in the short). I saw this cartoon years ago and “remembered” Skelton himself making a cameo and delivering the line–the Mandela effect! It wasn’t until I rewatched the short just now after reading the column that I learned I had misremembered it all this time.

Chicken Little and Who Killed Who are two of my favorite cartoons ever. The latter was probably the first modern gag cartoon.

Re “Okay, Smokey, roll ‘em!”: Bugs is referring to Henry Garner, aka “Smokey”, aka “Swamp Rabbit”, a cameraman at the Schlesinger studio in charge of filming and screening pencil tests. He was also an all-purpose handyman, handling everything from building camera stands to working on Leon Schlesinger’s car. The staff admired his ingenious solutions to mechanical problems and were charmed by his thick Ozark Mountain accent. Chuck Jones devoted several pages of CHUCK AMUCK to a character sketch of the man — amusing, but I can’t vouch for its accuracy.

According to Jones, Smokey was an alcoholic who spent his last years in an institution. I assume Smokey was a smoker . Maybe he rolled his own.

But doesn’t Red “Skeleton” appear in the cartoon?

We always thought it was "Mama buy me dat!"

The Blackie cartoons are interesting to watch because it seems like the staff at Famous were fighting to get this character to work, putting their weight into it with surprisingly good gags and solid personalities. It actually comes close to working, with the only drawback being a lack of good foils to play off the protagonist.

I have to wonder why Blackie was dropped after only a few shorts. My only guess is that Paramount didn’t want a “screwball” character because they felt it was against the company’s image? Or maybe audience reception at the time froze the poor sheep out in the cold?

A shame that Harvey Comics lost the opportunity to buy out those Blackie shorts to NNA. Blackie could have had greater potential as a Harvey character, at least as a “ringer” to provide back-end filler stories for other titles.

Isn’t it amazing that the “Chicken Little” cartoon downplays references to World War II, enough to pass as a regular Disney cartoon with a very sad ending. Even I enjoyed a different narration, like Frank Graham in the original, Jiminy Cricket in “Jiminy Cricket: Storyteller” and Ludwig von Drake in “Man is His Own Worst Enemy”.