Traversing 1939 to early 1941, we encounter more interactive screen madness from Tex Avery, a classic behind-the-scenes mix of live-action and animation from Friz Freleng, a star-studded Disney Hollywood romp, and efforts to keep up with the Warners from Terrytoons and Screen Gems. Animation was getting sophisticated, and audiences were beginning to expect that cartoon characters might talk back and think outside the box – leading to the most creative of directors attempting to outdo themselves with more outlandish character interplay in each successive film.

Thugs With Dirty Mugs (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 5/6/39 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – Avery is at it again, playing with the conventions of theater-going in small houses, and breaking the fourth wall to not only have characters interact with audience, but audience interact with characters, here providing a key plot point toward the resolution of the story. The cartoon is a splendidly-on target send-up of Warner’s favorite live-action genre – the gangster picture, which had virtually put Warner dramas on the map with such mega-hits as “Little Caesar” and “The Public Enemy”, and spawned superstars of the medium including Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, and a then-budding Humphrey Bogart. The style of Warner feature credits is mimicked to introduce our cast of characters and the “actors” portraying them. A police chief is portrayed by F. H.A. (Sherlock) Homes (reference to a popular home financing program), portraying Flat-Foot Flanigan (with a floy floy) (reference to a current Slim Gaillard scat-singing song hit, “Flat Foot Floogee (with a floy floy)”). The gangster is portrayed by Ed. G. Robemsome, as Killer Diller. The scene abruptly cuts to newspaper Extra editions filling the screen, shouting headlines of the Killer robbing the First through 19th National Banks – with one exception, explained by another headline: “13th National Bank Skipped – Killer Superstitious”. The crooks have robbery down to a science, including drive-thru service, where they zoom their black limousine through the front door, and come out hauling the entire vault on wheels – which miraculously converts into the shape of a trailer. They pull up in front or bank, then reverse direction with such speed, they tirn the panels of their limousine inside-out. Another headline announces, “87 Banks Robbed Today.”

Thugs With Dirty Mugs (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 5/6/39 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – Avery is at it again, playing with the conventions of theater-going in small houses, and breaking the fourth wall to not only have characters interact with audience, but audience interact with characters, here providing a key plot point toward the resolution of the story. The cartoon is a splendidly-on target send-up of Warner’s favorite live-action genre – the gangster picture, which had virtually put Warner dramas on the map with such mega-hits as “Little Caesar” and “The Public Enemy”, and spawned superstars of the medium including Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, and a then-budding Humphrey Bogart. The style of Warner feature credits is mimicked to introduce our cast of characters and the “actors” portraying them. A police chief is portrayed by F. H.A. (Sherlock) Homes (reference to a popular home financing program), portraying Flat-Foot Flanigan (with a floy floy) (reference to a current Slim Gaillard scat-singing song hit, “Flat Foot Floogee (with a floy floy)”). The gangster is portrayed by Ed. G. Robemsome, as Killer Diller. The scene abruptly cuts to newspaper Extra editions filling the screen, shouting headlines of the Killer robbing the First through 19th National Banks – with one exception, explained by another headline: “13th National Bank Skipped – Killer Superstitious”. The crooks have robbery down to a science, including drive-thru service, where they zoom their black limousine through the front door, and come out hauling the entire vault on wheels – which miraculously converts into the shape of a trailer. They pull up in front or bank, then reverse direction with such speed, they tirn the panels of their limousine inside-out. Another headline announces, “87 Banks Robbed Today.”

We meet the Killer personally at the hideout, as he and the gang survey the day’s loot (although Killer cautions one of his boys to lay off breaking into then penny gum machines – there ain’t no money in ‘em.) Killer addresses the audience directly for the first time, observing that he sounds just like Eddie Robinson – then brags that he can also do an impression of Fred Allen too! He breaks into a monologue a la Allen on “Town Hall Tonight”, until one of Killer’s gang gets him back in focus, by asking him to “Quit showing off.” The Killer’s jobs continue, reaching the 112th National Bank, and the Worst National Bank (at which Killer erases the painted numbering of the bank’s assets on the window, reducing it to nothing). Just to vary things up, the Killer even holds up a pay telephone at gunpoint, forcing the operator to signal a jackpot payoff of coins from the coin slot.

We meet the Killer personally at the hideout, as he and the gang survey the day’s loot (although Killer cautions one of his boys to lay off breaking into then penny gum machines – there ain’t no money in ‘em.) Killer addresses the audience directly for the first time, observing that he sounds just like Eddie Robinson – then brags that he can also do an impression of Fred Allen too! He breaks into a monologue a la Allen on “Town Hall Tonight”, until one of Killer’s gang gets him back in focus, by asking him to “Quit showing off.” The Killer’s jobs continue, reaching the 112th National Bank, and the Worst National Bank (at which Killer erases the painted numbering of the bank’s assets on the window, reducing it to nothing). Just to vary things up, the Killer even holds up a pay telephone at gunpoint, forcing the operator to signal a jackpot payoff of coins from the coin slot.

The police remain baffled, while the gang plots their next heist. A scene inside the hideout reveals to the audience the gang’s plotting to break into the home of Mrs. Lottajewels to crack the safe. In the midst of the planning, the shadow of a theater patron rises into the frame from the middle right of the screen, dons his hat, and begins crossing the theater as if squeezing his way up the row with intent to exit the show. The Killer spots him, and pulls out a pistol, aiming it squarely at the shadow. “Where do ya think you’re going?”, Killer inquires. The meek-mannered shadow-man replies, “Well, Mr. Killer, this is where I came in” (in a day when theaters ran films continuously without clearing the theater, and it was possible to stay in your seat to see the same picture a second, and maybe even a third time if one desired). “Well, you sit right back down until this thing’s over, see!”, demands Killer. The timid patron quickly shimmies his way back across the theater, and disappears from our view into his seat. Killer whispers to one of his gang (though still remaining fully audible) that this guy might be trying to sneak out of the theater to squeal to the cops. The scene onscreen dissolves to the police chief nervously pacing the floor of his office, claiming he could trap the Killer, if he could only get a tipoff as to his next job. The shadow of the theater patron rises once again, calling out that he’s sat through this picture twice, and the Killer will be at Mrs. Lottajewels tonight. “Thanks”, responds the chief, racing for the door, but returning to address the patron face to face, as “You little tattletale.” (This strange tipoff raises the obvious question never answered by the film – without the tip, how did the police ever catch the Killer during the previous two screenings of the cartoon?) The gang infiltrates the Lottajewels mansion that night, leaving their looming shadows behind in the darkness to watch the door, and proceed to the safe, whose combination dial turns out merely to be a radio tuner, tuning in on a broadcast of The Lone Ranger. The police are already waiting in the darkness, surrounding the crooks as the lights are thrown on. Killer is arrested, and a final newspaper headline announces that the Killer has received a long sentence. We see a prison schoolroom, where the Killer, wearing a dunce cap to go with his prison stripes, is forced to stay after school, writing a hundred times on the blackboards the sentence “I’ve been a naughty boy.” The Killer turns to stick his tongue out at us like a school-age brat, as the scene irises out.

The police remain baffled, while the gang plots their next heist. A scene inside the hideout reveals to the audience the gang’s plotting to break into the home of Mrs. Lottajewels to crack the safe. In the midst of the planning, the shadow of a theater patron rises into the frame from the middle right of the screen, dons his hat, and begins crossing the theater as if squeezing his way up the row with intent to exit the show. The Killer spots him, and pulls out a pistol, aiming it squarely at the shadow. “Where do ya think you’re going?”, Killer inquires. The meek-mannered shadow-man replies, “Well, Mr. Killer, this is where I came in” (in a day when theaters ran films continuously without clearing the theater, and it was possible to stay in your seat to see the same picture a second, and maybe even a third time if one desired). “Well, you sit right back down until this thing’s over, see!”, demands Killer. The timid patron quickly shimmies his way back across the theater, and disappears from our view into his seat. Killer whispers to one of his gang (though still remaining fully audible) that this guy might be trying to sneak out of the theater to squeal to the cops. The scene onscreen dissolves to the police chief nervously pacing the floor of his office, claiming he could trap the Killer, if he could only get a tipoff as to his next job. The shadow of the theater patron rises once again, calling out that he’s sat through this picture twice, and the Killer will be at Mrs. Lottajewels tonight. “Thanks”, responds the chief, racing for the door, but returning to address the patron face to face, as “You little tattletale.” (This strange tipoff raises the obvious question never answered by the film – without the tip, how did the police ever catch the Killer during the previous two screenings of the cartoon?) The gang infiltrates the Lottajewels mansion that night, leaving their looming shadows behind in the darkness to watch the door, and proceed to the safe, whose combination dial turns out merely to be a radio tuner, tuning in on a broadcast of The Lone Ranger. The police are already waiting in the darkness, surrounding the crooks as the lights are thrown on. Killer is arrested, and a final newspaper headline announces that the Killer has received a long sentence. We see a prison schoolroom, where the Killer, wearing a dunce cap to go with his prison stripes, is forced to stay after school, writing a hundred times on the blackboards the sentence “I’ve been a naughty boy.” The Killer turns to stick his tongue out at us like a school-age brat, as the scene irises out.

Dangerous Dan McFoo (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 7/15/39 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – Avery’s first crack at lampooning “The Shooting of Dan McGrew” by Robert W. Service. This would also mark Avery’s first pairing with radio veteran Arthur Q. Bryan, then a regular on the “Fibber McGee and Molly” radio show as Doc Gamble in his street voice, but also developing his “W”-laden speech pattern that would become the recognizable voice of Elmer Fudd, used as the voice of Dan here. This version is comparatively milder than the better-known Droopy saga of the 1940’s. but features several curious signature Avery touches. When a fight commences beyween Dan and the woman-hungry stranger from out of the night, a streetcar periodically makes an entrance through the saloon swinging doors, for the sole purpose of sounding its bell to start and end the rounds of the fight. When Dan complains to a referee about something in his opponent’s glove, the ref produces from the suspect glove one, two, three, and four horseshoes, plus the horse. (This gag, with objects reworked to fall from the sky, was reused at MGM about a decade later in “Bad Luck Blackie”.) The camera freezes the action at intervals to show the audience the blows as they land, revealing a series of humorous fouls, and one slug that hits the bartender in the jaw instead of Dan. Finally, the narrator has had enough. “Hey, you mugs. You aren’t getting anywhere.” The narrator’s hands (drawn as cartoon instead of real-life) toss two dueling pistols into the frame, each landing at the feet of the respective combatants. “Here, take these. Let’s get this thing over with”, concludes the narrator. The lights go out. A woman screams (as the lady known as Sue lets out with a badly underplayed, “eek”), and two guns blaze in the dark. The lights come up to find Dan on the floor. Sue now turns on her overacting abilities, thinking Dan mortally wounded. “Speak to me. SPEAK TO ME”, she wails. Dan, apparently not hurt at all, casually raises his head, and calmly utters “Hewwo”, for the iris out.

Dangerous Dan McFoo (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 7/15/39 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – Avery’s first crack at lampooning “The Shooting of Dan McGrew” by Robert W. Service. This would also mark Avery’s first pairing with radio veteran Arthur Q. Bryan, then a regular on the “Fibber McGee and Molly” radio show as Doc Gamble in his street voice, but also developing his “W”-laden speech pattern that would become the recognizable voice of Elmer Fudd, used as the voice of Dan here. This version is comparatively milder than the better-known Droopy saga of the 1940’s. but features several curious signature Avery touches. When a fight commences beyween Dan and the woman-hungry stranger from out of the night, a streetcar periodically makes an entrance through the saloon swinging doors, for the sole purpose of sounding its bell to start and end the rounds of the fight. When Dan complains to a referee about something in his opponent’s glove, the ref produces from the suspect glove one, two, three, and four horseshoes, plus the horse. (This gag, with objects reworked to fall from the sky, was reused at MGM about a decade later in “Bad Luck Blackie”.) The camera freezes the action at intervals to show the audience the blows as they land, revealing a series of humorous fouls, and one slug that hits the bartender in the jaw instead of Dan. Finally, the narrator has had enough. “Hey, you mugs. You aren’t getting anywhere.” The narrator’s hands (drawn as cartoon instead of real-life) toss two dueling pistols into the frame, each landing at the feet of the respective combatants. “Here, take these. Let’s get this thing over with”, concludes the narrator. The lights go out. A woman screams (as the lady known as Sue lets out with a badly underplayed, “eek”), and two guns blaze in the dark. The lights come up to find Dan on the floor. Sue now turns on her overacting abilities, thinking Dan mortally wounded. “Speak to me. SPEAK TO ME”, she wails. Dan, apparently not hurt at all, casually raises his head, and calmly utters “Hewwo”, for the iris out.

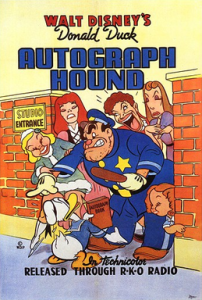

The Autograph Hound (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 9/1/39 – Jack King, dir.) – By 1939, Donald was well established as Disney’s new star on the block, launched into his own cartoon series in 1937, and beating out the Mouse in bookings and screen popularity. Recognition of this star status called for an “event” film intended to rival the stature of “Mickey’s Gala Premier”, in which the cartoon duck could self-consciously mingle into the celebrity world of Hollywood. However, another movie premiere would be too much like cheating. So Donald is cast in a position of lower aspiration – a mere movie fan, trying to get into a Hollywood studio to acquire an autograph collection. He is not exactly given the star treatment, as he is treated as riff raff by the studio guard, who begins the film by booting Donald out of the gate, leaving a visible footprint on Donald’s rear end. Donald predicts by over 20 years the moves of another lowly status-seeker (Hanna-Barbera’s Top Cat), by faking out the guard with the appearance that he is a guest in the limousine of Greta Garbo, actually riding on the rear fender of the car instead of inside the cab. Averting the guard’s billy club, he drops in on the sets of several illustrious stars of the day, including an extended visit to Mickey Rooney’s dressing room, where the two compete in showing off with magic tricks that leave egg on Donald’s face – literally. Donald flies into his usual temper-tantrum moves, and Rooney cleverly places a violin and bow into Donald’s hands, leaving the duck unwittingly providing musical accompaniment for Rooney’s Irish jigs!

The Autograph Hound (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 9/1/39 – Jack King, dir.) – By 1939, Donald was well established as Disney’s new star on the block, launched into his own cartoon series in 1937, and beating out the Mouse in bookings and screen popularity. Recognition of this star status called for an “event” film intended to rival the stature of “Mickey’s Gala Premier”, in which the cartoon duck could self-consciously mingle into the celebrity world of Hollywood. However, another movie premiere would be too much like cheating. So Donald is cast in a position of lower aspiration – a mere movie fan, trying to get into a Hollywood studio to acquire an autograph collection. He is not exactly given the star treatment, as he is treated as riff raff by the studio guard, who begins the film by booting Donald out of the gate, leaving a visible footprint on Donald’s rear end. Donald predicts by over 20 years the moves of another lowly status-seeker (Hanna-Barbera’s Top Cat), by faking out the guard with the appearance that he is a guest in the limousine of Greta Garbo, actually riding on the rear fender of the car instead of inside the cab. Averting the guard’s billy club, he drops in on the sets of several illustrious stars of the day, including an extended visit to Mickey Rooney’s dressing room, where the two compete in showing off with magic tricks that leave egg on Donald’s face – literally. Donald flies into his usual temper-tantrum moves, and Rooney cleverly places a violin and bow into Donald’s hands, leaving the duck unwittingly providing musical accompaniment for Rooney’s Irish jigs!

Donald further provides another gag that would be copied a year later by the Three Stooges in “An Ache In Every Stake”, as he acquires the autograph of skating star Sonja Henie, etched by skates into an ice block, only to have the whole thing melt down to an ice cube as Donald crosses a desert set while carrying the block with ice tongs. A run-in with the Ritz Brothers subjects Donald to the Ritz’s costume-changing random mayhem, and produces a group autograph penned upon Donald’s rear end. All the while, the studio cop remains in close pursuit. Donald finally arrives at a nautical set, where Shirley Temple, wearing a little sailor suit, is performing a staircase dance. Donald climbs the stairs and trips up her steps, causing both of them to tumble down to the dock. However, Shirley is the first to recognize Donald for who he is. “You’re Donald Duck!” (Is this a continuation of the myth that only kids watch cartoons?) She and Donald both produce their autograph books, and simultaneously ask for each other’s autograph. Donald obliges, and receives in return a choice specimen of Shirley’s penmanship, capped by an “i” dotted with a kiss. The happy duck whoops and jumps into the air – but is caught around the neck by the brawny arm of the cop protruding through a backdrop porthole. “Now I got ‘ya”, snarls the cop. “You leave him alone”, protests Shirley. “He’s Donald Duck.” “D-d-Donald Duck?”, stammers the cop in shock, releasing his grip on the duck’s neck as if he were a hot potato. As the name rings out, there is a general clamor throughout the studio, as all its celebrities repeat the duck’s hallowed name, reach Into their pockets, and produce autograph books of their own, all anxious to acquire the writing of their favorite cartoon star – an autograph which at least at that time would have been in fairly short supply.

Donald further provides another gag that would be copied a year later by the Three Stooges in “An Ache In Every Stake”, as he acquires the autograph of skating star Sonja Henie, etched by skates into an ice block, only to have the whole thing melt down to an ice cube as Donald crosses a desert set while carrying the block with ice tongs. A run-in with the Ritz Brothers subjects Donald to the Ritz’s costume-changing random mayhem, and produces a group autograph penned upon Donald’s rear end. All the while, the studio cop remains in close pursuit. Donald finally arrives at a nautical set, where Shirley Temple, wearing a little sailor suit, is performing a staircase dance. Donald climbs the stairs and trips up her steps, causing both of them to tumble down to the dock. However, Shirley is the first to recognize Donald for who he is. “You’re Donald Duck!” (Is this a continuation of the myth that only kids watch cartoons?) She and Donald both produce their autograph books, and simultaneously ask for each other’s autograph. Donald obliges, and receives in return a choice specimen of Shirley’s penmanship, capped by an “i” dotted with a kiss. The happy duck whoops and jumps into the air – but is caught around the neck by the brawny arm of the cop protruding through a backdrop porthole. “Now I got ‘ya”, snarls the cop. “You leave him alone”, protests Shirley. “He’s Donald Duck.” “D-d-Donald Duck?”, stammers the cop in shock, releasing his grip on the duck’s neck as if he were a hot potato. As the name rings out, there is a general clamor throughout the studio, as all its celebrities repeat the duck’s hallowed name, reach Into their pockets, and produce autograph books of their own, all anxious to acquire the writing of their favorite cartoon star – an autograph which at least at that time would have been in fairly short supply.

Greta Garbo (who never bothered to look at the unknown passenger previously riding on her limo), drops her leading man Clark Gable out of her arms and onto the floor, in her haste to scamper off the set with her book. A trio of harem girls (Wikipedia attributes them to be the Andrews Sisters, though this would appear unlikely as their film careers did not skyrocket until following years) desert sultan Charlie McCarthy, who remarks, “Ho hum, fickle women.”. Marauding soldiers taking a hill in a war picture race off the set, followed by the battle-wounded extras who rise from the “dead” off the field, to form a second wave of autograph seekers. The great horse Silver deserts the Lone Ranger with a loud whinny, throwing him into the sagebrush to reverse direction at the duck’s name. A montage of other celebrities join the stampede, including Stepin Fetchit, Roland Young, Joe E. Brown, Martha Raye, Hugh Herbert, Irvin S. Cobb, Edward Arnold, Katharine Hepburn, Eddie Cantor, Slim Summerville, Lionel Barrymore, Bette Davis, Groucho Marx, Harpo Marx, Mischa Auer, Joan Crawford, and Charles Boyer. Our hero finds himself nearly buried by an ever-rising pile of autograph books being flung to him for signature, at the top of the pile of which rises the form of the studio cop, who seems to be about to raise a billy club over the duck’s head, but unscrews a cap off it, to reveal that it is actually an oversized fountain pen. “Your autograph, sir?” meekly asks the cop. Donald, in a mood for vengeance, responds “Okay, Flatfoot”, taking the pen, but pulling a handle to cause it to jet ink all over the cop’s face and shirt. The remains of the ink puddle and settle upon the cop’s white shirt, forming a blobby version of the letters “DONALD DUCK”, as we hear Donald’s hearty offscreen laugh for the iris out.

Greta Garbo (who never bothered to look at the unknown passenger previously riding on her limo), drops her leading man Clark Gable out of her arms and onto the floor, in her haste to scamper off the set with her book. A trio of harem girls (Wikipedia attributes them to be the Andrews Sisters, though this would appear unlikely as their film careers did not skyrocket until following years) desert sultan Charlie McCarthy, who remarks, “Ho hum, fickle women.”. Marauding soldiers taking a hill in a war picture race off the set, followed by the battle-wounded extras who rise from the “dead” off the field, to form a second wave of autograph seekers. The great horse Silver deserts the Lone Ranger with a loud whinny, throwing him into the sagebrush to reverse direction at the duck’s name. A montage of other celebrities join the stampede, including Stepin Fetchit, Roland Young, Joe E. Brown, Martha Raye, Hugh Herbert, Irvin S. Cobb, Edward Arnold, Katharine Hepburn, Eddie Cantor, Slim Summerville, Lionel Barrymore, Bette Davis, Groucho Marx, Harpo Marx, Mischa Auer, Joan Crawford, and Charles Boyer. Our hero finds himself nearly buried by an ever-rising pile of autograph books being flung to him for signature, at the top of the pile of which rises the form of the studio cop, who seems to be about to raise a billy club over the duck’s head, but unscrews a cap off it, to reveal that it is actually an oversized fountain pen. “Your autograph, sir?” meekly asks the cop. Donald, in a mood for vengeance, responds “Okay, Flatfoot”, taking the pen, but pulling a handle to cause it to jet ink all over the cop’s face and shirt. The remains of the ink puddle and settle upon the cop’s white shirt, forming a blobby version of the letters “DONALD DUCK”, as we hear Donald’s hearty offscreen laugh for the iris out.

Mountain Ears (Screen Gems/Columba, Color Rhapsodies, 11/3/39 – Manny Gould, dir.) – Narrated by a Jack Benny sound-alike (Jack Lescoulie), this tale is basically a Tex Avery wanna-be spot gag reel on hillbilly life. The short is well-animated and enjoyable, but really gets nowhere as to establishing any sort of plotline – not even a feud. In viewing it, one almost feels this is the kind of padding material that might have been placed ahead of the footage of Avery’s A Feud There Was if the short had been expanded into a two-reeler.

Mountain Ears (Screen Gems/Columba, Color Rhapsodies, 11/3/39 – Manny Gould, dir.) – Narrated by a Jack Benny sound-alike (Jack Lescoulie), this tale is basically a Tex Avery wanna-be spot gag reel on hillbilly life. The short is well-animated and enjoyable, but really gets nowhere as to establishing any sort of plotline – not even a feud. In viewing it, one almost feels this is the kind of padding material that might have been placed ahead of the footage of Avery’s A Feud There Was if the short had been expanded into a two-reeler.

The main attraction of the short is a little buck-toothed boy with a rifle and a coonskin cap, who seems to be looking for trouble. The narrator first greets him with an attempt to speek mountain dialect. The kid starts to giggle half-way through it, and turns to a pet dog, remarking about the speaker, “He’s a fur-eigner.” The kid leaves the scene while consciously making eye contact with the narrator and the camera, ad sticks his tongue out at us just for fun. The boy shows up periodically through the cartoon, at one point sitting on a shelf at a distance from the dinner table at which about twenty hillbillies uncouthly chow down on dinner, and uses a rod and reel to cast a line to the table, retrieving an entire roast turkey for himself. As the film nears its end, the boy approaches the camera again, and the shot utilizes the Fleischer “Goonland” technique, bringing upwards the bottom edge of the picture frame with letter-boxing, so that the boy appears to lean on and over the bottom of the screen, attempting to flirt with a cute little blonde girl in the theater. As the boy begins to climb over the screen edge to enter the theater, the hand of the narrator enters the frame, picking the boy up by the suspenders of his trousers and lifting him back into the cartoon, cautioning him not to flirt, as he will embarrass the girl. “You’re tetched in the head”, remarks the kid to the narrator, and seems to disappear over a ridge in the road. “We’re rid of him”, concludes the narrator, only to have the kid pop his head out from behind a rock to remark, “Oh, is that so?” The kid takes off farther along the road, as the narrator vows, “I’ll fix you, you fresh kid.” The narrator’s hand grabs one corner of the background image, and flips it over, revealing another angle at some distance further down the road, with the kid running straight toward the camera and the narrator’s hand.

The kid reacts with a start at the dirty trick, and dodges right and left as the narrator’s hands grab for him. “Let go of me, ya big stiff”, yells the boy, as the narrator’s fingers again get a grip on the kid’s suspenders, but accidentally cause them to snap off. “Now see whatcha done?” complains the boy, with his pants falling down. “I’m sorry” apologizes the narrator, but the boy kicks the narrator’s fingers, and races offscreen, yelling for his mother. The boy dives into some tall grass, and the two hands pf the narrator attempt to sift through it, with no luck at revealing the child’s whereabouts. “This is like looking for a needle in a haystack”, he says. The hands produce a large fine-tooth comb, with which they begin combing through the grass in search of the boy. They finally get lucky, turning up the boy upon the comb. The boy sticks out his tongue again, runs to the end pf the comb (busting through several teeth of it with his feet), and dives into a pond. The narrator produces an eye-dropper, and sucks the boy out of the water. He begins chastising the boy at his bad behavior, and reminds him what the little girl in the theater must think of him now. But the boy produces a slingshot, and takes dead aim at the camera, letting the pebble fly, straight into the lens, turning the picture multiple shades of color as if we are seeing through the eyes of the dazed narrator. “Enough is enough. Good night, folks”, says the narrator, as his hand pulls in the frame of the Columbia logo, for the fade out.

The kid reacts with a start at the dirty trick, and dodges right and left as the narrator’s hands grab for him. “Let go of me, ya big stiff”, yells the boy, as the narrator’s fingers again get a grip on the kid’s suspenders, but accidentally cause them to snap off. “Now see whatcha done?” complains the boy, with his pants falling down. “I’m sorry” apologizes the narrator, but the boy kicks the narrator’s fingers, and races offscreen, yelling for his mother. The boy dives into some tall grass, and the two hands pf the narrator attempt to sift through it, with no luck at revealing the child’s whereabouts. “This is like looking for a needle in a haystack”, he says. The hands produce a large fine-tooth comb, with which they begin combing through the grass in search of the boy. They finally get lucky, turning up the boy upon the comb. The boy sticks out his tongue again, runs to the end pf the comb (busting through several teeth of it with his feet), and dives into a pond. The narrator produces an eye-dropper, and sucks the boy out of the water. He begins chastising the boy at his bad behavior, and reminds him what the little girl in the theater must think of him now. But the boy produces a slingshot, and takes dead aim at the camera, letting the pebble fly, straight into the lens, turning the picture multiple shades of color as if we are seeing through the eyes of the dazed narrator. “Enough is enough. Good night, folks”, says the narrator, as his hand pulls in the frame of the Columbia logo, for the fade out.

The Bear’s Tale (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 4/13/40 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – Another old fable, the Three Bears, gets the Avery treatment – with a little help from a cameo by Red Riding Hood and the wolf. Narration style mimics a popular recitation piece which had made the rounds on Broadway and on a good-selling Victor record by Tom McNaughton, entitled “The Three Trees”, in which a meaningless tale is related with numerous repeated references to characters or objects, each one represented by some identifying musical sting which plays over and over again throughout the piece. The bears all have their own identifying music lines: Papa (“What’s the Matter With Father?”). Mama (“That Wonderful Mother of Mine”), and Baby (“Rock-a-Bye Baby”). Things get crossed up when Goldilocks shows up by mistake at the home of Red Riding Hood’s gramdma, encountering the wolf. “Isn’t this where the Three Bears live?” asks Goldie. “That outfit lives two miles down the road”, snarls the disappointed wolf, ushering Goldie out the door before she louses up his appointment with Red Riding Hood. Goldie struts away in a feminine huff, remarking “What’s she got that I haven’t got?” The wolf slams the door, and laughs sarcastically at the nerve of Goldie’s remark – then realizes that her observation is all too true. Why not a Goldilocks lunch? Boning up on the details of the other fairy tale from a copy of the Goldilocks story resting in Grandma’s library, the wolf learns that Goldie is ultimately headed for Baby Bear’s bed. Rushing outside, the wolf hails a taxi from nowhere, promises to pay for any speeding tickets, and beats Goldie to the bears’ house, hiding in Baby Bear’s bed. Goldie eventually arrives, and is about to climb the stairs, when she hears the telephone ring in the living room. It is Red Riding Hood, calling from Grandma’s, having found an explanatory note from the wolf on Grandma’s bed, stating that he got tired of waiting, and has gone to the Three Bears to eat Goldilocks.

The Bear’s Tale (Warner, Merrie Melodies, 4/13/40 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – Another old fable, the Three Bears, gets the Avery treatment – with a little help from a cameo by Red Riding Hood and the wolf. Narration style mimics a popular recitation piece which had made the rounds on Broadway and on a good-selling Victor record by Tom McNaughton, entitled “The Three Trees”, in which a meaningless tale is related with numerous repeated references to characters or objects, each one represented by some identifying musical sting which plays over and over again throughout the piece. The bears all have their own identifying music lines: Papa (“What’s the Matter With Father?”). Mama (“That Wonderful Mother of Mine”), and Baby (“Rock-a-Bye Baby”). Things get crossed up when Goldilocks shows up by mistake at the home of Red Riding Hood’s gramdma, encountering the wolf. “Isn’t this where the Three Bears live?” asks Goldie. “That outfit lives two miles down the road”, snarls the disappointed wolf, ushering Goldie out the door before she louses up his appointment with Red Riding Hood. Goldie struts away in a feminine huff, remarking “What’s she got that I haven’t got?” The wolf slams the door, and laughs sarcastically at the nerve of Goldie’s remark – then realizes that her observation is all too true. Why not a Goldilocks lunch? Boning up on the details of the other fairy tale from a copy of the Goldilocks story resting in Grandma’s library, the wolf learns that Goldie is ultimately headed for Baby Bear’s bed. Rushing outside, the wolf hails a taxi from nowhere, promises to pay for any speeding tickets, and beats Goldie to the bears’ house, hiding in Baby Bear’s bed. Goldie eventually arrives, and is about to climb the stairs, when she hears the telephone ring in the living room. It is Red Riding Hood, calling from Grandma’s, having found an explanatory note from the wolf on Grandma’s bed, stating that he got tired of waiting, and has gone to the Three Bears to eat Goldilocks.

In a favorite oft-repeated Avery gag, a split-screen view showing both ends of the phone conversation merely serves to separate the characters by a few feet from one another with a dividing line down the screen’s middle, and the characters demonstrate awareness of their proximity by Red reaching around the dividing line to pass Goldie the Wolf’s note to read for herself. (A similar gag also appears in “Thugs With Dirty Mugs” referenced above.) Goldie ditches the whole affair upon Red’s warning, leaving the Three Beas to return home for their porridge without her. But a sneeze upstairs tells the bears someone else is present, and in unison, they react “Robbers!”, and hide under the breakfast table. Papa bravely volunteers to go upstairs and take care of the intruder. But Papa is again fully self-aware of his screen position and role-playing, as he begins heartily laughing to himself as he climbs the stairs (in Avery’s own deep-voiced guffaw often heard in the early Warner films). Papa can’t resist an aside to the audience. “I know there ain’t no robber up there. Just a little tiny girl named Goldilocks. I read this story last week in Reader’s Digest.” Reaching the bedroom, he pulls back the covers from Baby’s bed, lifting the occupant out from slumber – to find himself face to face with the wolf. Papa is so shocked, he can’t find one word to utter with clarity, blurting out random syllables. He shoots down the stairs like a comet, darts under the breakfast table, and drags along Mama and junior out the front door – which Papa does’t even pause to open. The three race off down the road into the sunset, with the Baby “bare behind” as his pants fall down while running.

In a favorite oft-repeated Avery gag, a split-screen view showing both ends of the phone conversation merely serves to separate the characters by a few feet from one another with a dividing line down the screen’s middle, and the characters demonstrate awareness of their proximity by Red reaching around the dividing line to pass Goldie the Wolf’s note to read for herself. (A similar gag also appears in “Thugs With Dirty Mugs” referenced above.) Goldie ditches the whole affair upon Red’s warning, leaving the Three Beas to return home for their porridge without her. But a sneeze upstairs tells the bears someone else is present, and in unison, they react “Robbers!”, and hide under the breakfast table. Papa bravely volunteers to go upstairs and take care of the intruder. But Papa is again fully self-aware of his screen position and role-playing, as he begins heartily laughing to himself as he climbs the stairs (in Avery’s own deep-voiced guffaw often heard in the early Warner films). Papa can’t resist an aside to the audience. “I know there ain’t no robber up there. Just a little tiny girl named Goldilocks. I read this story last week in Reader’s Digest.” Reaching the bedroom, he pulls back the covers from Baby’s bed, lifting the occupant out from slumber – to find himself face to face with the wolf. Papa is so shocked, he can’t find one word to utter with clarity, blurting out random syllables. He shoots down the stairs like a comet, darts under the breakfast table, and drags along Mama and junior out the front door – which Papa does’t even pause to open. The three race off down the road into the sunset, with the Baby “bare behind” as his pants fall down while running.

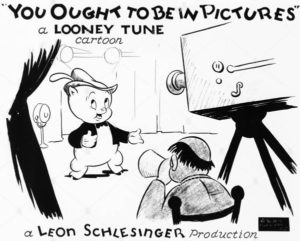

You Ought To Be In Pictures (Warner, Looney Tunes (Porky Pig), 4/27/40 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – An iconic mix of live action and animation, set at the Warner studio, for a behind-the-scenes look into the life of a cartoon star. At the Warner cartoon unit, an animator (Wikipedia identifies him as Fred Jones – any relation to Chuck?) draws in the outline of Porky on a drawing pad, until the clock signals time for “LUNCH!” A stampede of animators (said to include brief glimpses of Chuck Jones and Robert Clampett), exit the studio doors, leaving the animation room deserted. “Psst”, utters a voice from above the drawing of Porky. Above, on a framed wall picture, stands Daffy Duck, with an inquiry as to whether Porky wants a good job. Porky responds that he already has a good job. In cartoons?, questions Daffy. The real life is in features, where Daffy claims he knows of an opening to play Bette Davis’s leading man. Porky reacts that he is not good enough for that, and besides, he has a contract here. Daffy prods Porky to ask the boss to be released from his contract, as an opportunity like this doesn’t happen every day. Daffy leaps down from his picture frame, and escorts Porky off the drawing pad to Leon Schlesinger’s door. Porky knocks lightly, but Daffy adds some forcefulness to it with a few fist pounds. Schlesinger meets with Porky, who informs him of his desire to try feature films, “What’s Errol Flynn got that I haven’t got?” asks Porky. Schlesinger is gracious about it, not one to stand in Porky’s way, and agrees to tear up Porky’s contract, if Porky is truly sure he knows what he is doing. A torn contract falls into the wastebasket, and, in a classic moment, Porky and Leon shake hands in a parting farewell. However, as Porky exits the office, Leon confides to the audience, “He’ll be back.”

You Ought To Be In Pictures (Warner, Looney Tunes (Porky Pig), 4/27/40 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – An iconic mix of live action and animation, set at the Warner studio, for a behind-the-scenes look into the life of a cartoon star. At the Warner cartoon unit, an animator (Wikipedia identifies him as Fred Jones – any relation to Chuck?) draws in the outline of Porky on a drawing pad, until the clock signals time for “LUNCH!” A stampede of animators (said to include brief glimpses of Chuck Jones and Robert Clampett), exit the studio doors, leaving the animation room deserted. “Psst”, utters a voice from above the drawing of Porky. Above, on a framed wall picture, stands Daffy Duck, with an inquiry as to whether Porky wants a good job. Porky responds that he already has a good job. In cartoons?, questions Daffy. The real life is in features, where Daffy claims he knows of an opening to play Bette Davis’s leading man. Porky reacts that he is not good enough for that, and besides, he has a contract here. Daffy prods Porky to ask the boss to be released from his contract, as an opportunity like this doesn’t happen every day. Daffy leaps down from his picture frame, and escorts Porky off the drawing pad to Leon Schlesinger’s door. Porky knocks lightly, but Daffy adds some forcefulness to it with a few fist pounds. Schlesinger meets with Porky, who informs him of his desire to try feature films, “What’s Errol Flynn got that I haven’t got?” asks Porky. Schlesinger is gracious about it, not one to stand in Porky’s way, and agrees to tear up Porky’s contract, if Porky is truly sure he knows what he is doing. A torn contract falls into the wastebasket, and, in a classic moment, Porky and Leon shake hands in a parting farewell. However, as Porky exits the office, Leon confides to the audience, “He’ll be back.”

Porky gets into his car (a pig-sized Model T), as Daffy tells him to tell the studio heads that “I sent you”, and not to settle for less than six grand a week. Porky pulls away around a corner, and Daffy’s true colors (despite being in black and white) are revealed. “This is my big chance”, he says, darting inside to have his own heart-to-heart with Leon. The scene changes to the main Warner Brothers studio, where a guard (played by writer

Porky gets into his car (a pig-sized Model T), as Daffy tells him to tell the studio heads that “I sent you”, and not to settle for less than six grand a week. Porky pulls away around a corner, and Daffy’s true colors (despite being in black and white) are revealed. “This is my big chance”, he says, darting inside to have his own heart-to-heart with Leon. The scene changes to the main Warner Brothers studio, where a guard (played by writer Ted Pierce Michael Maltese) watches entries at the gate. (It should be noted that live-action was filmed with a silent camera, with all dialogie post-dubbed, sometimes considerably out of sync. Mel Blanc supplies voices for everyone except Leon, for whom the dubber is unknown.) Porky tries to drive right in, but his car is picked up bodily by the guard and tossed out. Porky only succeeds in re-entering the studio by wearing an Oliver Hardy costume. But the guard quickly realizes something was suspect about that Hardy, and sees through Porky’s disguise. Porky tries to hide inside a sound stage where the filming of a musical number is in progress, but sneezes, toppling over a pile of film cans, causing the shot to be ruined. The Director (Gerry Chiniquy) has Porky ejected from the set, and the studio cop resumes the pursuit. Porky drives his model T into the middle of a Western set, where a stagecoach race is just about to commence. He quickly reverses the car’s direction, and exits the town set just one jump ahead of being trampled by the horses’ hooves. He finally manages to turn off the trail to safety, and decides he doesn’t think he likes this feature business. He suddenly wonders if he can get his old job back, and turns the car to aim back to the cartoon studio.

The scene changes back to Leon’s office, where Daffy is attempting to wheel and deal, trying to convince Leon to take him in starring role to fill the position left by Porky’s broken contract. Daffy xlaims it was always him, not Porky, that did all the work, and breaks into an audition production number “I’d Be Famous On the Screen” (a new lyric to a pop tune of the day, “Concert In the Park”). While Daffy even attempts to sing grand opera, Schlesinger sits calmly reading the trade papers, dismissing Daffy’s proposal with a wave of his hand, and a half-hearted assurance that he’ll think it over. Porky dodges frantically through crosstown traffic in a process shot of driving point-of-view, and finally arrives at the studio door. Opening Leon’s door slightly, Porky whispers to Daffy, signaling him that he needs to see him. Porky leads the curious Daffy into a stock room, and suddenly, the sounds of a fight are heard from within, with all manner of papers, debris, and even a broken chair flying out the open doorway. Porky exits intact, dusting off his hands, but Daffy does not follow. Porky appears at Leon’s desk, fishing in the wastebasket for the halves of the torn contract. “I never really meant to break my contract. April fool”, says Porky, displaying the contract halves for Leon to take back. Leon pulls the surprise, reaching into another drawer, and producing the real Porky Pig contract, revealing that he never tore it up in the first place. “Now get back to work”, says Leon cheerily, and Porky gratefully respond, “Thanks”, and returns to his pose on the drawing pad. But again, there is a whisper from above him. Daffy has returned to the picture frame, bandaged from his injuries in the fight from head to toe. But he still is up to his old tricks. “I hope you didn’t sign up here again, ‘cause I know where there’s a pip of a job at 12 grand a week – playing opposite Greta…” His speech is rudely interrupted by a tomato thrown into his face by Porky. Daffy wipes away the runny mess, finishing his sentence in disgruntled fashion: “…Garbo.”

The scene changes back to Leon’s office, where Daffy is attempting to wheel and deal, trying to convince Leon to take him in starring role to fill the position left by Porky’s broken contract. Daffy xlaims it was always him, not Porky, that did all the work, and breaks into an audition production number “I’d Be Famous On the Screen” (a new lyric to a pop tune of the day, “Concert In the Park”). While Daffy even attempts to sing grand opera, Schlesinger sits calmly reading the trade papers, dismissing Daffy’s proposal with a wave of his hand, and a half-hearted assurance that he’ll think it over. Porky dodges frantically through crosstown traffic in a process shot of driving point-of-view, and finally arrives at the studio door. Opening Leon’s door slightly, Porky whispers to Daffy, signaling him that he needs to see him. Porky leads the curious Daffy into a stock room, and suddenly, the sounds of a fight are heard from within, with all manner of papers, debris, and even a broken chair flying out the open doorway. Porky exits intact, dusting off his hands, but Daffy does not follow. Porky appears at Leon’s desk, fishing in the wastebasket for the halves of the torn contract. “I never really meant to break my contract. April fool”, says Porky, displaying the contract halves for Leon to take back. Leon pulls the surprise, reaching into another drawer, and producing the real Porky Pig contract, revealing that he never tore it up in the first place. “Now get back to work”, says Leon cheerily, and Porky gratefully respond, “Thanks”, and returns to his pose on the drawing pad. But again, there is a whisper from above him. Daffy has returned to the picture frame, bandaged from his injuries in the fight from head to toe. But he still is up to his old tricks. “I hope you didn’t sign up here again, ‘cause I know where there’s a pip of a job at 12 grand a week – playing opposite Greta…” His speech is rudely interrupted by a tomato thrown into his face by Porky. Daffy wipes away the runny mess, finishing his sentence in disgruntled fashion: “…Garbo.”

As promised in a previous chapter of this trail, some blatant reuse of old Van Beuren gags forms the nucleus for Gandy Goose’s The Magic Pencil (Terrytoons/Fox, 11/15/40 – Volney White, dir.) Although White receives the director’s credit, one can bet that John Foster was looming in the background, both in story development and in consultation on the drawing of various scenes, and many parts of this film look like they were lifted from the very cels of Tom and Jerry’s “Pencil Mania”. Ten thousand box tops and one thin dime are the ticket to acquisition of a magic pencil, states a radio announcer of station WAK. Gandy just happens to possess such box tops, awaiting use m cabinets of his kitchen pantry. He lugs the box tops over to the large floor model radio in the living room, where the tops are abruptly sucked into the radio speaker as if by a vacuum. The box tops spit out of the announcer’s microphone at the other end of the line, and the announcer (not seeming to take any specific note as to whether the necessary dime is also included) inserts the magic pencil into the radio microphone. Back in Gandy’s living room, the speaker of the radio converts shape into a mouth, and spits out the pencil into Gandy’s hand.

As promised in a previous chapter of this trail, some blatant reuse of old Van Beuren gags forms the nucleus for Gandy Goose’s The Magic Pencil (Terrytoons/Fox, 11/15/40 – Volney White, dir.) Although White receives the director’s credit, one can bet that John Foster was looming in the background, both in story development and in consultation on the drawing of various scenes, and many parts of this film look like they were lifted from the very cels of Tom and Jerry’s “Pencil Mania”. Ten thousand box tops and one thin dime are the ticket to acquisition of a magic pencil, states a radio announcer of station WAK. Gandy just happens to possess such box tops, awaiting use m cabinets of his kitchen pantry. He lugs the box tops over to the large floor model radio in the living room, where the tops are abruptly sucked into the radio speaker as if by a vacuum. The box tops spit out of the announcer’s microphone at the other end of the line, and the announcer (not seeming to take any specific note as to whether the necessary dime is also included) inserts the magic pencil into the radio microphone. Back in Gandy’s living room, the speaker of the radio converts shape into a mouth, and spits out the pencil into Gandy’s hand.

Sourpuss thinks this magic pencil stuff is the bunk. But Gandy repeats the act of his Van Beuren predecessors, drawing an egg in mid-air. Sourpuss predictably looks underneath it, upon which the egg drops into his eye. Gandy next repeats Jerry’s trick of drawing a saxophone, then blowing visible music motes out of it, each of which converts into a goose, and swims away on the lake. Sourpuss picks up a board to try to knock some sense into Gandy’s head, but Gandy draws a coiled line above his own head, which becomes a real-life spring, bouncing the blow intended for Gandy back onto Sourpuss’s noggin. Gandy pacifies Sourpuss by drawing a stick-figure female cat, but with a pretty face. Sourpuss is smitten, and begin to dance with her, ignoring Gandy. Gandy decides to liven things up, by also drawing a stick-figure villain cat. (One might easily say this was the dress rehearsal for the revival of Oil Can Harry in feline form, years before his first appearance in a Mighty Mouse short.) The villain makes off with the girl, and Sourpuss demands that Gandy do something. Gandy repeats another of Jerry’s old gags, drawing wheels and fenders around a door on the side of a shed, converting the wheels and door into a two-dimensional car in which he and Sourpuss can pursue the villain.

Sourpuss thinks this magic pencil stuff is the bunk. But Gandy repeats the act of his Van Beuren predecessors, drawing an egg in mid-air. Sourpuss predictably looks underneath it, upon which the egg drops into his eye. Gandy next repeats Jerry’s trick of drawing a saxophone, then blowing visible music motes out of it, each of which converts into a goose, and swims away on the lake. Sourpuss picks up a board to try to knock some sense into Gandy’s head, but Gandy draws a coiled line above his own head, which becomes a real-life spring, bouncing the blow intended for Gandy back onto Sourpuss’s noggin. Gandy pacifies Sourpuss by drawing a stick-figure female cat, but with a pretty face. Sourpuss is smitten, and begin to dance with her, ignoring Gandy. Gandy decides to liven things up, by also drawing a stick-figure villain cat. (One might easily say this was the dress rehearsal for the revival of Oil Can Harry in feline form, years before his first appearance in a Mighty Mouse short.) The villain makes off with the girl, and Sourpuss demands that Gandy do something. Gandy repeats another of Jerry’s old gags, drawing wheels and fenders around a door on the side of a shed, converting the wheels and door into a two-dimensional car in which he and Sourpuss can pursue the villain.

The locale changes to a sawmill on a cliffside adjoining a river waterfall – a favorite type of hangout for Oil Can in the Fannie Zilch comedies of earlier years. There, the villain attempts to vie for the girl’s affections with a string of pearls, but a look at the strand under a jeweler’s glass raises contempt in the girl, who throws the phonies back at the villain. The villain points to the only other option – to be tied to a log heading for the buzzsaw. Gandy and Sourpuss meanwhile find themselves on the wrong road, staring at the waterfall towering above them from a vantage point across a wide chasm. Sourpuss again insists on Gandy’s help. Gandy takes the pencil up again, and draws a two-dimensional line resembling a flight of steps, up and up, which they scale to a position just above the waterwheel of the mill. They jump down, but are briefly stalled as they find themselves treading the paddles of the spinning mill wheel, unable to make any headway. The villain has by now tied the girl to the log and activated the saw, and waits for the machinery to do its dirty work. Our heroes finally leap off the mill wheel, taking a few bounces off the mill roof, which attracts the villain’s attention outside. He comes face to face with Sourpuss, and produces a sword, while Sourpuss attempts to defend himself in a duel with only a forked tree limb for a weapon. Just as the villain is about to score a fatal blow, Gandy turns the pencil around, using an eraser to rub him out of existence. “Quick, the girl”, shouts Sourpuss. The girl has kept herself from the sawblade by shimmying down the length of the log with her bonds little by little, and Gandy draws a brake handle into the floor next to the saw, pulling it to stop the machinery cold. Releasing the girl, Sourpuss declares, “She’s mine”, and embraces her with a kiss. Gandy, however, repeats Jerry’s action from Van Beuren, playfully swiching the pencil into reverse to suck away the entire outlines of the girl cat. “Gimme that pencil”, snarls the angry Sourpuss, and flings the pencil point-first into the ground. Like the mystery bottle of booze in Van Beuren’s “Magic Art”, the pencil suddenly takes off into the air like a skyrocket, and explodes in a fireworks display, revealing three black outlines that fall to the ground, and unfold into a stick-figure fife and drum corps of the “Spirit of ‘76″ variety. With no more pencil to worry about, Gandy and Sourpuss decide to just go with it, and join the parade down the street, as the film closes.

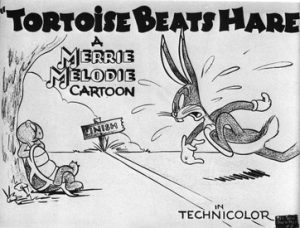

Tortoise Beats Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 3/15/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – The rise of Bugs Bunny’s screen career is sometimes a puzzling one in its chronology. As most afficionados of Looney Tunes know, Bugs went through several designs and a drastic voice change before becoming more than a recurring supporting player in the cartoons of others, having only one starring cartoon to his name before 1940. Under Avery’s direction, his character was redesigned, revoiced, and crystalized in “A Wild Hare”. However, it is notable that at the time, the studio was pushing Elmer Fudd, and likely viewed the cartoon as a starring vehicle for Elmer rather than the rabbit. Despite an Oscar nomination for the Avery film, the studio did not seem in any instantaneous hurry to rush into production “rabbit” films. Instead, they concentrated on Elmer, handing the slow-witted character to the slowest but best-draftsmanship director on the lot – Chuck Jones, for an entirely solo appearance in late 1940, “Good Night, Elmer”, and a re-pairing with the “wabbit” in early 1941, “Elmer’s Pet Rabbit” (in which Bugs was finally given an almost begrudging second-billing by name in the credits). Neither film was remarkably successful, and Jones’ idea of the rabbit resulted in yet another voice change for the character to a deeper resonance and significantly less manic pace. It should have been apparent to the executives at this point that Elmer had not been the selling point of “Wild Hare”’s success, and that he alone was not likely to provide the studio with its next meal ticket. Thus, the talents of Avety were finally recommissioned to provide a star-bill comeback for the rabbit character, without Elmer or even a hunter for support, as if to subject the character to the acid test of ability to engage an audience. The rabbit lived up to his potential, restored by Avery to his voice as displayed in Avery’s prior film, and placed in an unusual position of prominence in the audience’s eye – at a vantage point somewhere between the theater screen and the audience seats!

Tortoise Beats Hare (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 3/15/41 – Fred (Tex) Avery, dir.) – The rise of Bugs Bunny’s screen career is sometimes a puzzling one in its chronology. As most afficionados of Looney Tunes know, Bugs went through several designs and a drastic voice change before becoming more than a recurring supporting player in the cartoons of others, having only one starring cartoon to his name before 1940. Under Avery’s direction, his character was redesigned, revoiced, and crystalized in “A Wild Hare”. However, it is notable that at the time, the studio was pushing Elmer Fudd, and likely viewed the cartoon as a starring vehicle for Elmer rather than the rabbit. Despite an Oscar nomination for the Avery film, the studio did not seem in any instantaneous hurry to rush into production “rabbit” films. Instead, they concentrated on Elmer, handing the slow-witted character to the slowest but best-draftsmanship director on the lot – Chuck Jones, for an entirely solo appearance in late 1940, “Good Night, Elmer”, and a re-pairing with the “wabbit” in early 1941, “Elmer’s Pet Rabbit” (in which Bugs was finally given an almost begrudging second-billing by name in the credits). Neither film was remarkably successful, and Jones’ idea of the rabbit resulted in yet another voice change for the character to a deeper resonance and significantly less manic pace. It should have been apparent to the executives at this point that Elmer had not been the selling point of “Wild Hare”’s success, and that he alone was not likely to provide the studio with its next meal ticket. Thus, the talents of Avety were finally recommissioned to provide a star-bill comeback for the rabbit character, without Elmer or even a hunter for support, as if to subject the character to the acid test of ability to engage an audience. The rabbit lived up to his potential, restored by Avery to his voice as displayed in Avery’s prior film, and placed in an unusual position of prominence in the audience’s eye – at a vantage point somewhere between the theater screen and the audience seats!

The title card. “Tortoise Beats Hare”, appears on the screen in usual fashion. But in a first for the cartoon medium, Bugs Bunny saunters by, nonchalantly chewing a carrot, as if it is his habit to take periodic walks in front of a movie-house screen. He reacts in mild surprise to the presence of the title card, as if not expecting to find any image on the screen in the first place, and with passing curiosity begins to read aloud the printed details of the various name credits to the film’s creators. Wherever possible, Bugs engages in complete mispronunciation of the credited names or emphasis on the wrong syllables. Dave Monahan becomes “Mon-AH-han”, and the director becomes “Fred a very”. Finally, Bugs’s eyes rise to the film title high above him, reading aloud “Tortoise Beats Hare.” There is a slight delay in his uptake of the significance of the words – then Bugs reacts with a gagging spit-take, spewing bits of crunchy carrot everywhere. Turning to the audience, Bugs rants “Tortoise Beats Hare? Why, these screwy guys don’t know what they’re talking about. Why, the big bunch of jerks!” Then Bugs lowers his voice, sharing a personal secret with the audience: “And I ought to know. I work for ‘em.” (Then how come you never learned how to correctly pronounce their names?) Bugs turns back to the screen, tearing the title card apart and into flying shreds of drawing paper, as he marches into the screen and a forest background in search of the upstart tortoise who thinks he’s so good. We are introduced to Cecil Turtle, a slow-paced but level-headed opposing personality to Bugs’ emotionalism, who would prove a perfect foil for the rabbit in three theatrical appearances and several television returns to follow. Bugs and Cecil challenge each other to a race, with a stakes of $10 to the winner.

The title card. “Tortoise Beats Hare”, appears on the screen in usual fashion. But in a first for the cartoon medium, Bugs Bunny saunters by, nonchalantly chewing a carrot, as if it is his habit to take periodic walks in front of a movie-house screen. He reacts in mild surprise to the presence of the title card, as if not expecting to find any image on the screen in the first place, and with passing curiosity begins to read aloud the printed details of the various name credits to the film’s creators. Wherever possible, Bugs engages in complete mispronunciation of the credited names or emphasis on the wrong syllables. Dave Monahan becomes “Mon-AH-han”, and the director becomes “Fred a very”. Finally, Bugs’s eyes rise to the film title high above him, reading aloud “Tortoise Beats Hare.” There is a slight delay in his uptake of the significance of the words – then Bugs reacts with a gagging spit-take, spewing bits of crunchy carrot everywhere. Turning to the audience, Bugs rants “Tortoise Beats Hare? Why, these screwy guys don’t know what they’re talking about. Why, the big bunch of jerks!” Then Bugs lowers his voice, sharing a personal secret with the audience: “And I ought to know. I work for ‘em.” (Then how come you never learned how to correctly pronounce their names?) Bugs turns back to the screen, tearing the title card apart and into flying shreds of drawing paper, as he marches into the screen and a forest background in search of the upstart tortoise who thinks he’s so good. We are introduced to Cecil Turtle, a slow-paced but level-headed opposing personality to Bugs’ emotionalism, who would prove a perfect foil for the rabbit in three theatrical appearances and several television returns to follow. Bugs and Cecil challenge each other to a race, with a stakes of $10 to the winner.

Bugs thinks it’s in the bag, unaware that Cecil is placing phone calls to every look-alike relative in his family, instructing them to take positions along the race course tomorrow, to give the rabbit “the works”. Avery even uses the split-screen dividing line between two callers gag again, as Cecil gives one family member firsthand instructions by poking his head and finger around the barrier. The remainder of the film is a revisit to a favorite Avery theme, initiated in Porky Pig’s “The Blow-Out”, of a character seemingly keeping up with another no matter what obstacles are placed in his path. Bugs cuts rope bridges, lays barbed wire, digs trenches, and places rows of giant logs and boulders across the road, and engages in other means of diverting Cecil from his course. At one point, Bugs remarks. “That oughta slow the little screwball down some”, only to find a turtle directly behind him, remaking, “Yep, that’s a tough one.” The turtles even pause in mid-program to deliver what would become another favorite Avery line of self-awareness: “We do this kinda stuff to him all through the picture.” Eventually. Bugs crosses the finish line, seemingly alone, only to find the original Cecil lounging under a tree past the line, asking what kept him. Bugs is forced to hand over the ten bucks, adding as he does “And I hope ‘ya choke” and sticking out his tongue at Cecil. Bugs attempts to exit, stupefied over his loss, but suddenly ponders, “Hey. I wonder if I’ve been tricked?” Behind him, finally revealing themselves, appear all ten tortoises, each holding one of Bugs’ dollar bills, responding, “Umm, it’s a possibility.” All ten turtles plant a kiss on Bugs’s jaw, for the fade out. (In later years. Avery would not repeat the one possible mistake of this cartoon – revealing the hoax at the very outset. He would find it delivered more laughs to let the pursued character be befuddled by the repeated presence of his adversary without explanation to the audience, only revealing the multiple look-alikes to the camera at the same time as discovered by the character pursued, so we are as surprised as they.)

Bugs thinks it’s in the bag, unaware that Cecil is placing phone calls to every look-alike relative in his family, instructing them to take positions along the race course tomorrow, to give the rabbit “the works”. Avery even uses the split-screen dividing line between two callers gag again, as Cecil gives one family member firsthand instructions by poking his head and finger around the barrier. The remainder of the film is a revisit to a favorite Avery theme, initiated in Porky Pig’s “The Blow-Out”, of a character seemingly keeping up with another no matter what obstacles are placed in his path. Bugs cuts rope bridges, lays barbed wire, digs trenches, and places rows of giant logs and boulders across the road, and engages in other means of diverting Cecil from his course. At one point, Bugs remarks. “That oughta slow the little screwball down some”, only to find a turtle directly behind him, remaking, “Yep, that’s a tough one.” The turtles even pause in mid-program to deliver what would become another favorite Avery line of self-awareness: “We do this kinda stuff to him all through the picture.” Eventually. Bugs crosses the finish line, seemingly alone, only to find the original Cecil lounging under a tree past the line, asking what kept him. Bugs is forced to hand over the ten bucks, adding as he does “And I hope ‘ya choke” and sticking out his tongue at Cecil. Bugs attempts to exit, stupefied over his loss, but suddenly ponders, “Hey. I wonder if I’ve been tricked?” Behind him, finally revealing themselves, appear all ten tortoises, each holding one of Bugs’ dollar bills, responding, “Umm, it’s a possibility.” All ten turtles plant a kiss on Bugs’s jaw, for the fade out. (In later years. Avery would not repeat the one possible mistake of this cartoon – revealing the hoax at the very outset. He would find it delivered more laughs to let the pursued character be befuddled by the repeated presence of his adversary without explanation to the audience, only revealing the multiple look-alikes to the camera at the same time as discovered by the character pursued, so we are as surprised as they.)

Despite this creative cartoon, it is notable that the executives continued to vacillate over the course of the next couple of seasons between who to assign the choice projects of continuing the “wabbit”’s career. Bugs would make the rounds of nearly every director on the lot (Norman McCabe missing out, as he never graduated to color production status), with no particular concentration of projects in Avery’s direction. Avery would direct only two more Bugs films before being ejected from the studio. Whether this was by choice (Avery always having a preference for working on one-shots), or the result of studio politics that eventually led to Avery’s firing is unknown – perhaps Schlesinger classified it as some sort of punishment to deprive the man, who had given Bugs his voice and legs, of creative control over the character as his career progressed. Friz Freling and Robert Clampett would thus play a larger early role in shaping Bugs as we know him until the later 1940’s, when anybody who was anybody would have his hand at steering the rabbit in a variety of different directions and nuances.

More from 1941 and on, next week.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Wow! Four Avery cartoons in one week! And I know we haven’t seen the last of him by any means!

It’s funny that the girl who was known as Sue talks like Katharine Hepburn, but Dan McFoo’s rival sees her in his mind’s eye as Bette Davis (I guess because Davis was under contract to Warner Bros., and Hepburn wasn’t). When she tells him “My heart belongs to Daddy,” that’s a song from the Cole Porter musical “Leave It to Me!”, then in its initial Broadway run. It was sung by Mary Martin in her Broadway debut.

It’s also funny that the song “You Oughta Be in Pictures” plays when Bette Davis’s image appears onscreen, just as Daffy mentions Bette Davis as a prospective co-star for Porky in, what else, “You Ought to Be in Pictures”.

I’m sure those are meant to be the Andrews Sisters in “The Autograph Hound”. While their film career had not yet taken off, they were already major recording artists, not to mention pin-up girls, by 1939.

“Mountain Ears” is a new one to me, and not at all bad for a Columbia Color Rhapsody. When the narrator describes Maw as “a regular Prudence Penny,” Prudence Penny was a pseudonymous advice columnist in the Hearst papers. She promoted values of thrift and economy, and regularly published recipes geared towards households on a tight budget. She was the subject of several short films in the Pete Smith Specialties series, one of which, “Penny Wisdom”, won an Oscar in 1938; Smith narrated all of his films, which is why the narrator in the cartoon takes offence when Maw mentions Pete Smith’s name. A Prudence Penny cookbook was published in 1939, so Prudence Penny’s popularity was apparently at its peak in this period. (Pardon my plosives.)

I believe the security guard in “You Ought to Be in Pictures” was played by Michael Maltese, not Tedd Pierce, and animator Fred Jones was no relation to Chuck.

Shirley Temple was the biggest box-office star of her day, so I rather suspect that the encounter with Donald Duck was more underscoring the idea that it takes a big mega-star to recognize the greatness of another. Plus, I believe at the time there was lots of publicity regarding Shirley’s affection for the Disney characters.

As her popularity increased, her age kept changing. My mother told me that when she was very young, Shirley Temple was older than my mother was. A couple of years later, they were the same age. A couple of years after that, Shirley was younger. I’m sure if the studio could have devised a way to keep her perpetually under twelve, they would have done so. As it was, they kept her career going until she really did start to age out of her roles.

The studio guard in “You Ought To Be in Pictures” is played by Michael Maltese, not Ted Pierce.

Corrected.

Cartoon self-awareness comes riding in from the West in “The Lone Stranger and Porky” (Schlesinger/Looney Tunes, 7/1/39 — Robert Clampett, dir.). A verbose and intrusive narrator prattles on as the villain robs Porky Pig’s stagecoach, the Indian scout Pronto summons the Lone Stranger (via television and magic mirror), and the hero and his horse Silver come to the rescue. When the Lone Stranger arrives, the villain unholsters his guns and opens fire; but then the smoke clears away, and we see the masked man standing unharmed atop a pinnacle from which the surrounding rock has been blasted away. “Gosh, what a punk shot!” sneers the narrator. “Oh, yeah?” snarls the villain, drawing his gun and firing straight out from the screen. The narrator gasps “You got me!” and expires with a death rattle.

After a romantic encounter between Silver and the villain’s horse, we see the Lone Stranger and the villain slugging it out on the edge of a cliff, until a kick sends the hero hurtling down into the canyon. As he falls, an intertitle appears onscreen: “Will the Lone Stranger be SMASHED on the rocks below? What about it[,] Audience?” The audience responds with an enthusiastic “NOOOOO!!!!!” The Lone Stranger skids to a halt and says “Correct! Absolutely correct!” in a game show host’s voice. Thanks to the audience’s support, he runs up the side of the cliff and saves the day. In the end, Silver returns with her newborn foals — one of whom bears a sinister moustache juts like the villain’s.

Animation from “The Lone Stranger and Porky” was reused later that year in “The Film Fan” (Looney Tunes, 16/12/39 — Robert Clampett, dir.), in which Porky is running an errand for his mother but stops to take in a kiddie matinée. After a series of gags parodying newsreels and other short subjects, we see a trailer for a film starring the Western hero “the Masked Marvel” and his horse, “Sterling.” A black duck seated next to Porky, possibly a young Daffy, produces a slingshot and shoots it at the screen. The projectile strikes Sterling on the rump, whereupon he turns around, faces the audience and demands: “Who’s the wise guy? Who’s the wise guy?”

Things I’ve always noticed about Schlesinger’s voice in “You Ought To Be in Pictures:” it doesn’t have the dead acoustic quality of a recording booth, but that of a larger, hard-walled room; and while I wouldn’t call his “S” sound a full-fledged lisp, it is noticeably mushy. Finally, his delivery doesn’t come off as that of a trained actor or voice artist, but as a civilian who can do his lines competently.

I didn’t state it explicitly, but I really suspect it’s Schelsinger’s own voice, probably recorded live.

With regard to Fred (?) Jones; if you look at page 72 of the hardcover edition of “Chuck Amuck,” you’ll see a picture of Chuck Jones’ unit, circa 1940. Richard Kent Jones, a relation, is in the picture along with Chuck. There is another figure identified as ” (?) Jones (unrelated)” which looks like the figure in this shot.

Tortoise Beats Hare shows how green Tex was. He makes one critical miscalculation: He reveals how Bugs was tricked from the beginning. Prime Avery would never do such a thing.

In yet another Porky Pig cartoon from 1939, “Chicken Jitters” (1/4/39 — Robert Clampett, dir.), a duckling hatches out of an eggshell, examines his surroundings, notices the audience watching him, exclaims “People!”, then produces a camera and snaps a photo of us.

As the world’s biggest Friz and Tex fan, this is my favorite post of the year!

I find it amusing that most of the stars Donald pesters for an autographed were contracted to 20th Century Fox at the time! A rather ironic coincidence.

At any rate, the premise behind The Magic Pencil would later be carried over to another Terrytoons character, Gaston Le Crayon … and, for some reason, Hanna-Barbera would deploy such on Cattanooga Cats with Scoots being thus entrusted.

On that last one, perhaps the best example would have to be in a bumber where Country, the band’s lead, asks Scoots to “draw something with your Magic Crayon,” whereupon Scoots would do a pastoral-looking mountain scene, after which Scoots would change from a French-looking artists’ dress to a striped dive suit and fins, “jump in” to the picture and start diving in the stream thus ensuing.

Presumably, Hanna-Barbera came up with the Magic Crayon bit independently of Terrytoons’ influence–or did they?