In the waning days of the golden era of theatrical cartoons, the luxury of storms and animation of weather extremes became a more seldom-seen sight. This seemed a natural progression in animation’s state of affairs, as budgets were becoming tighter (a subject which actually becomes a plot-point for a notable episode reviewed below), and visual spectacle had been gradually disappearing from all but the most elite studios’ product in favor of more economical “limited animation” and purely gag-oriented scripts. Thus, instead of covering a single season or less as in prior installments of this article series, today’s overview quantum-leaps across three years of production (1953-1955). Many one-shots are represented here, together with visits from Tom and Jerry, Bugs Bunny, Woody Woodpecker, Donald Duck and Chip ‘n’ Dale. Some of the last warming trends toward weather animation, before the beginning of a long cold spell.

How to Keep Cool (Terrytons/Fox, Dimwit, 10/1/53 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – For a small number of films, Terry attempted to cast Heckle and Jeckle’s nemesis Dimwit Dog in the role of Goofy, for his own series of “How To” shorts modeled after the Disney formula. It never quite worked, with Dimwit lacking the lovable winning personality of the Disney original, and spending most of his time reacting more like a frustrated Porky Pig taken to extremes instead of a good-natured fellow who rolls with the punches and still somehow comes up smiling. Here, cast under the “everyman” name of Sammy Sizzle, Dimwit faces an urban heat wave, on a day that the narrator refers to as “hot enough to melt a mother-in-law’s heart – and that, brother, is hot.” There are some original sight gags to speak of. An opening shot has skyscrapers drooping over like melted candles. Dimwit sits in his apartment between twin fans, simultaneously trying to sip six lemonades through straws. Looking at a wall thermometer, the glass ball at the base of the mercury tube develops a mouth, and begins rapidly panting like a perspiring dog. A glass vase holding a flower on the windowsill melts into a puddle as if hit by a glass-blower’s torch. Dimwit pulls the windowshade down to block out the sunlight – but the sun’s rays burn a hole in the center of the shade, disintegrating it to a crisp. A newspaper ad suggests the alternative of spending the day at Balmy Beach. To the film’s credit, it predicts a gag that would later be used by Goofy himself, as everyone else in the city gets the same idea, producing a nightmarish traffic jam extending as far as the eye can see (later used in Goofy’s “Aquamania”). His day at the beach is fraught with disruptions, including uncooperative surf (sort of “Hawaiian Holiday” revisited), and a swarm of flies who systematically devour his food. Sammy ultimately returns home, and, in an ending censored from television, finally enjoys some fine food and drink in a setting of comfort, sealed inside the interior of his refrigerator. (Daffy Duck was right: “What do yoi know? The little light – it stays on.”)

How to Keep Cool (Terrytons/Fox, Dimwit, 10/1/53 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – For a small number of films, Terry attempted to cast Heckle and Jeckle’s nemesis Dimwit Dog in the role of Goofy, for his own series of “How To” shorts modeled after the Disney formula. It never quite worked, with Dimwit lacking the lovable winning personality of the Disney original, and spending most of his time reacting more like a frustrated Porky Pig taken to extremes instead of a good-natured fellow who rolls with the punches and still somehow comes up smiling. Here, cast under the “everyman” name of Sammy Sizzle, Dimwit faces an urban heat wave, on a day that the narrator refers to as “hot enough to melt a mother-in-law’s heart – and that, brother, is hot.” There are some original sight gags to speak of. An opening shot has skyscrapers drooping over like melted candles. Dimwit sits in his apartment between twin fans, simultaneously trying to sip six lemonades through straws. Looking at a wall thermometer, the glass ball at the base of the mercury tube develops a mouth, and begins rapidly panting like a perspiring dog. A glass vase holding a flower on the windowsill melts into a puddle as if hit by a glass-blower’s torch. Dimwit pulls the windowshade down to block out the sunlight – but the sun’s rays burn a hole in the center of the shade, disintegrating it to a crisp. A newspaper ad suggests the alternative of spending the day at Balmy Beach. To the film’s credit, it predicts a gag that would later be used by Goofy himself, as everyone else in the city gets the same idea, producing a nightmarish traffic jam extending as far as the eye can see (later used in Goofy’s “Aquamania”). His day at the beach is fraught with disruptions, including uncooperative surf (sort of “Hawaiian Holiday” revisited), and a swarm of flies who systematically devour his food. Sammy ultimately returns home, and, in an ending censored from television, finally enjoys some fine food and drink in a setting of comfort, sealed inside the interior of his refrigerator. (Daffy Duck was right: “What do yoi know? The little light – it stays on.”)

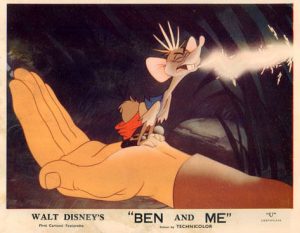

Ben and Me (Disney/RKO, 2 reel special, 11/10/53 – Hamilton Luske, dir.) has been previously discussed at length in my prior series, “A Revolutionary Article”. Only a portion of this odd tale, about a mouse whom only the rodent world realizes was single-handedly responsible for all the great achievements the human world attributes to Benjamin Franklin, will be dealt with for purposes of today’s survey – the famous incident of Ben’s kite flying in attempt to discover electricity. Amos Mouse, apprentice and assistant to Franklin, becomes Franklin’s hidden advisor, hiding inside Franklin’s hat to take notes and overhear all that goes on around him, as well as whisper suggestions for his speech and actions into his ear. Franklin’s habit of “tinkering”, however, gets carried too far, as he tricks Amos into a kite ride for a firsthand observation of Franklin’s secret experiment to channel electricity. While Amos thinks he is merely the first airborne reporter, as he rides in a small passenger compartment attached to the kite frame, lightning strikes, and in an elaborately-animated sequence, the kite and Amos are blasted out of the skies. Franklin lifts the battered Amos from the wreckage, and asks, “Was it electricity?” Amos replies, “WAS IT ELECTRICITY?????”, with current shooting out in bright sparks from his mouth. Amos quits on the spot, walking off in a huff amidst several puddles, each resulting in additional electric shocks which light Amos up as he departs. Of course, there is an ultimate reconciliation, with Amos returning with a written list of demands for change – which ultimately forms the preamble of the Declaration of Independence.

Ben and Me (Disney/RKO, 2 reel special, 11/10/53 – Hamilton Luske, dir.) has been previously discussed at length in my prior series, “A Revolutionary Article”. Only a portion of this odd tale, about a mouse whom only the rodent world realizes was single-handedly responsible for all the great achievements the human world attributes to Benjamin Franklin, will be dealt with for purposes of today’s survey – the famous incident of Ben’s kite flying in attempt to discover electricity. Amos Mouse, apprentice and assistant to Franklin, becomes Franklin’s hidden advisor, hiding inside Franklin’s hat to take notes and overhear all that goes on around him, as well as whisper suggestions for his speech and actions into his ear. Franklin’s habit of “tinkering”, however, gets carried too far, as he tricks Amos into a kite ride for a firsthand observation of Franklin’s secret experiment to channel electricity. While Amos thinks he is merely the first airborne reporter, as he rides in a small passenger compartment attached to the kite frame, lightning strikes, and in an elaborately-animated sequence, the kite and Amos are blasted out of the skies. Franklin lifts the battered Amos from the wreckage, and asks, “Was it electricity?” Amos replies, “WAS IT ELECTRICITY?????”, with current shooting out in bright sparks from his mouth. Amos quits on the spot, walking off in a huff amidst several puddles, each resulting in additional electric shocks which light Amos up as he departs. Of course, there is an ultimate reconciliation, with Amos returning with a written list of demands for change – which ultimately forms the preamble of the Declaration of Independence.

Puppy Tale (MGM, Tom and Jerry, 1/23/54 – William Hanna/Joseph Barbera, dir.) – a somewhat gentler, less frenetic T&J episode than usual – and consequently among the less-frequently shown. While setting out a miniature milk bottle for the milkman at night, Jerry spots a car tossing a sack with something moving inside off a bridge into the river. Jerry rescues the bundle, opening it to find six puppies inside. Five escape off into the night, but one remains behind, insistent upon making friends with Jerry, and licking the mouse in the face. Jerry tries to get rid of him by making him chase a stick – but only ends up performing another rescue when the dog nearly falls into the river once again. Deciding the pup is in no position to fend for itself, Jerry takes the little guy home. However, he’s not quite so little, as his head is too big for the mousehole – necessitating sneaking the pup in through the front door. The pup, however, becomes fixated upon Tom’s dish of milk, and, try as Jerry might to stop him, insists upon lapping it up, right under Tom’s nose. He also invades Tom’s bed, hogging the blanket. The expected chase begins, with several failed attempts by Tom to throw the pup out. A clever casting of a bar of soap into Jerry’s and the pup’s path leads to a slide straight out the door, and Tom finally bolts it to prevent their re-entry. Tom settles down to sleep, until the blast of a lightning bolt outside awakens him. Much as in their early success, “The Night Before Christmas”, Tom begins to have pangs of conscience about casting Jerry and the pup out into the forceful rainstorm developing outside, and envisions the two helplessly being swept down a river. Tom grabs an umbrella, and exits the house, looking everywhere and whistling for the dog. Jerry and the pup are in fact safer than expected, huddled together on the grass, using a newspaper as a blanket. They hear Tom as he crosses the same bridge over the river from where the sack was thrown. A sudden gust of wind lifts the umbrella and Tom into the air, causing them to splash down into the river. Now it is Tom that flounders helplessly against the current. Jerry and the pup to the rescue. Tom is dragged into the house and revived. Instead of reacting with anger at the trouble the pip has caused him, Tom begrudgingly produces a fresh bowl of milk, and a miniature hand-made bed for the dog. Rather than hog all this good fortune for himself, the pup barks a few times at the front door, summoning the other five pups – then all of them converge on the bowl of milk. Tom and Jerry can only exchange looks, then pause to admire how cute the puppies are, for the iris out.

Puppy Tale (MGM, Tom and Jerry, 1/23/54 – William Hanna/Joseph Barbera, dir.) – a somewhat gentler, less frenetic T&J episode than usual – and consequently among the less-frequently shown. While setting out a miniature milk bottle for the milkman at night, Jerry spots a car tossing a sack with something moving inside off a bridge into the river. Jerry rescues the bundle, opening it to find six puppies inside. Five escape off into the night, but one remains behind, insistent upon making friends with Jerry, and licking the mouse in the face. Jerry tries to get rid of him by making him chase a stick – but only ends up performing another rescue when the dog nearly falls into the river once again. Deciding the pup is in no position to fend for itself, Jerry takes the little guy home. However, he’s not quite so little, as his head is too big for the mousehole – necessitating sneaking the pup in through the front door. The pup, however, becomes fixated upon Tom’s dish of milk, and, try as Jerry might to stop him, insists upon lapping it up, right under Tom’s nose. He also invades Tom’s bed, hogging the blanket. The expected chase begins, with several failed attempts by Tom to throw the pup out. A clever casting of a bar of soap into Jerry’s and the pup’s path leads to a slide straight out the door, and Tom finally bolts it to prevent their re-entry. Tom settles down to sleep, until the blast of a lightning bolt outside awakens him. Much as in their early success, “The Night Before Christmas”, Tom begins to have pangs of conscience about casting Jerry and the pup out into the forceful rainstorm developing outside, and envisions the two helplessly being swept down a river. Tom grabs an umbrella, and exits the house, looking everywhere and whistling for the dog. Jerry and the pup are in fact safer than expected, huddled together on the grass, using a newspaper as a blanket. They hear Tom as he crosses the same bridge over the river from where the sack was thrown. A sudden gust of wind lifts the umbrella and Tom into the air, causing them to splash down into the river. Now it is Tom that flounders helplessly against the current. Jerry and the pup to the rescue. Tom is dragged into the house and revived. Instead of reacting with anger at the trouble the pip has caused him, Tom begrudgingly produces a fresh bowl of milk, and a miniature hand-made bed for the dog. Rather than hog all this good fortune for himself, the pup barks a few times at the front door, summoning the other five pups – then all of them converge on the bowl of milk. Tom and Jerry can only exchange looks, then pause to admire how cute the puppies are, for the iris out.

Watch the cartoon CLICK HERE.

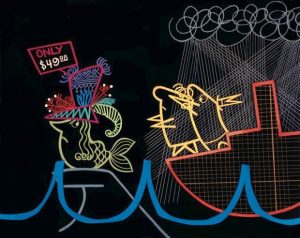

Fudget’s Budget (UPA/Columbia, 6/17/54 – Robert Cannon, dir.) – A visually-creative study in artistic simplicity, with characters drawn in outline form without color fill, who display their flatness as a single straight line when they turn, backgrounds consisting almost entirely of financial graph charts in photographic black and white reversal, and narrators periodically depicted as mere colored lines which twist to form the outline of a mouth and chin. Tedd Pierce and T. Hee take story credit, together with Cannon himself. A surprisingly sprightly piano score, reminiscent of silent-movie comedies, allows the film to pace itself brightly and briskly. The film is dedicated to those who manage to live within a family budget (a question mark appearing immediately following this dedication, as if to say, “Who?”) Mr. and Mrs. Fudget, and their small family, are fairly good on counting pennies and watching expenditures, residing in a home which is a graph chart bordered by outlines and a single green clinging vine. Good, that is, except for those times when temptation gets the better of Mrs. Fudget, who finds herself irresistibly compelled to purchase a new hat. Mr. Fudget complains that such frivolity must stop (as all good husbands are prone to do), and the two systematically cut corners on all other expenditures to stay within their means. Riding out this brief crisis, Mr. Fudget finally receives a raise. They expand the size of their home graph, install a picket fence and television antenna depicted in the shape of dollar signs, and spend a bit of dough on night clubs and sports cars to have a little fling.

Fudget’s Budget (UPA/Columbia, 6/17/54 – Robert Cannon, dir.) – A visually-creative study in artistic simplicity, with characters drawn in outline form without color fill, who display their flatness as a single straight line when they turn, backgrounds consisting almost entirely of financial graph charts in photographic black and white reversal, and narrators periodically depicted as mere colored lines which twist to form the outline of a mouth and chin. Tedd Pierce and T. Hee take story credit, together with Cannon himself. A surprisingly sprightly piano score, reminiscent of silent-movie comedies, allows the film to pace itself brightly and briskly. The film is dedicated to those who manage to live within a family budget (a question mark appearing immediately following this dedication, as if to say, “Who?”) Mr. and Mrs. Fudget, and their small family, are fairly good on counting pennies and watching expenditures, residing in a home which is a graph chart bordered by outlines and a single green clinging vine. Good, that is, except for those times when temptation gets the better of Mrs. Fudget, who finds herself irresistibly compelled to purchase a new hat. Mr. Fudget complains that such frivolity must stop (as all good husbands are prone to do), and the two systematically cut corners on all other expenditures to stay within their means. Riding out this brief crisis, Mr. Fudget finally receives a raise. They expand the size of their home graph, install a picket fence and television antenna depicted in the shape of dollar signs, and spend a bit of dough on night clubs and sports cars to have a little fling.

Then, one morning, their graph begins to bend and twist at weird angles, as their budget home begins to fall apart, Junior does an aggravating thing – he grew, requiring everything new. The plumbing springs leaks, as does the roof and water heater. The car’s transmission falls apart. The rains come down, and as the graph house briefly descends below the water, it surfaces again in the form of a small bobbing boat, trying to keep its head above the waves, while the loan sharks (depicted as the aquatic variety) close in. Obtaining a loan, in the form of dollar bills rolled into the shape of bailing pails, Mr. and Mrs. Fudget bail vigorously from both sides of the ship to keep the waves from swamping it. They turn down invitations to poker games and nights on the town by the neighbors, refuse to renew their subscription to Fortune Magazine, and Mr. Fudget shields the Missus’s eyes from yet another new hat. Finally, the sun breaks through, and the Fudgets find themselves high and dry. “How’d they do it?” inquires a Ned Sparks-like negative narrator. The more positive narrator responds, “Just stuck to it. Paid every bill” – but then admits that it didn’t hurt that a distant uncle remembered them in a will. The Fudgets are finally ready to join their neighbors for that night on the town they turned down – but find the neighbors bailing to save their own sinking ship, responding to the invite, “Aw, shut up.” The film ends with trouble about to brew again, as Mrs. Fudget appears wearing another expensive new hat, and the words, “The End” appear on screen followed by that same red question mark – which converts into the Ned Sparks narrator, who smiles for the first time in the film, and quips sarcastically, “Aha!” Overlooked for any awards, despite its daring and novel approach.

Then, one morning, their graph begins to bend and twist at weird angles, as their budget home begins to fall apart, Junior does an aggravating thing – he grew, requiring everything new. The plumbing springs leaks, as does the roof and water heater. The car’s transmission falls apart. The rains come down, and as the graph house briefly descends below the water, it surfaces again in the form of a small bobbing boat, trying to keep its head above the waves, while the loan sharks (depicted as the aquatic variety) close in. Obtaining a loan, in the form of dollar bills rolled into the shape of bailing pails, Mr. and Mrs. Fudget bail vigorously from both sides of the ship to keep the waves from swamping it. They turn down invitations to poker games and nights on the town by the neighbors, refuse to renew their subscription to Fortune Magazine, and Mr. Fudget shields the Missus’s eyes from yet another new hat. Finally, the sun breaks through, and the Fudgets find themselves high and dry. “How’d they do it?” inquires a Ned Sparks-like negative narrator. The more positive narrator responds, “Just stuck to it. Paid every bill” – but then admits that it didn’t hurt that a distant uncle remembered them in a will. The Fudgets are finally ready to join their neighbors for that night on the town they turned down – but find the neighbors bailing to save their own sinking ship, responding to the invite, “Aw, shut up.” The film ends with trouble about to brew again, as Mrs. Fudget appears wearing another expensive new hat, and the words, “The End” appear on screen followed by that same red question mark – which converts into the Ned Sparks narrator, who smiles for the first time in the film, and quips sarcastically, “Aha!” Overlooked for any awards, despite its daring and novel approach.

Casey Bats Again (Disney/RKO, 6/18/54 – Jack Kinney, dir.), makes interesting use of rain and sunshine to emphasize the emotional ups and downs of its protagonist character. When we last left the Mighty Casey (in Kinney’s Casey at the Bat segment from the feature “Make Mine Music”), he had just achieved his monumental strikeout, ending his baseball career amidst the thunder and lightning of a driving rainstorm which has cleared the playing field of everyone but him and the unhittable baseball. The current film picks right up from said moment, but brings to light a new aspect of Casey’s world – his marital life. While Casey had been originally portrayed in the first film as quite a favorite of and flirtatious with the ladies, it seems that he is in actuality secretly married (a fact which, had it been known, would have likely killed his appeal to feminine audiences). Oddly also, Mrs. Casey, a sweet young thing, seems to have no jealousy as to Casey’s public image of sex-appeal and the attention he gives other ladies – perhaps as it no longer matters anyway, given that his baseball career is washed-up. Instead, Mrs. Casey enters the scene with a whisper into her husband’s ear – of the expected arrival of a little one into the family home. Casey’s heart brightens, as he anticipates his offspring will be a strapping youth full of his talents, to carry on the family name into the Baseball Hall of Fame. At this revelation, the dark storm clouds above dissipate and depart, and a warm glow of sunshine beams down upon the Mr. and Mrs. at this fortunate turn of fate.

Casey Bats Again (Disney/RKO, 6/18/54 – Jack Kinney, dir.), makes interesting use of rain and sunshine to emphasize the emotional ups and downs of its protagonist character. When we last left the Mighty Casey (in Kinney’s Casey at the Bat segment from the feature “Make Mine Music”), he had just achieved his monumental strikeout, ending his baseball career amidst the thunder and lightning of a driving rainstorm which has cleared the playing field of everyone but him and the unhittable baseball. The current film picks right up from said moment, but brings to light a new aspect of Casey’s world – his marital life. While Casey had been originally portrayed in the first film as quite a favorite of and flirtatious with the ladies, it seems that he is in actuality secretly married (a fact which, had it been known, would have likely killed his appeal to feminine audiences). Oddly also, Mrs. Casey, a sweet young thing, seems to have no jealousy as to Casey’s public image of sex-appeal and the attention he gives other ladies – perhaps as it no longer matters anyway, given that his baseball career is washed-up. Instead, Mrs. Casey enters the scene with a whisper into her husband’s ear – of the expected arrival of a little one into the family home. Casey’s heart brightens, as he anticipates his offspring will be a strapping youth full of his talents, to carry on the family name into the Baseball Hall of Fame. At this revelation, the dark storm clouds above dissipate and depart, and a warm glow of sunshine beams down upon the Mr. and Mrs. at this fortunate turn of fate.

Months pass, and the expected big day arrives. Casey is so busy trying to contact the doctor on the phone, he fails to notice that the doctor has anticipated who is calling from the mere urgency of the phone’s ring, made his appearance at the Casey household, and already completed the delivery, as the doctor hands to Casey his bundled offspring while Casey is still on the phone. Casey wheels his pride and joy outside in a baby carriage, and is pleased and amazed when the kid tosses a rattle at him, with the precision of a skilled infielder. Casey substitutes baseball and glove for the rattle, and the kid puts on the glove and handles a catch of the ball as if covering the base for a quick out at first. The child then tosses the ball back to Casey with the speed of a fast-ball pitcher, causing a brief flame to ignite from Casey’s hand. A baseball natural! There’s just one small detail Casey has overlooked, and Mrs. Casey can’t seem to get a word in edgewise to explain it to him. Only when Casey first assists in a change of diapers does he discover that his miracle child is not exactly what he thought – but a girl! Immediately upon this revelation, another dark cloud appears from nowhere in the sky above the Casey house, and rain pours down upon Casey’s world again.

Months pass, and the expected big day arrives. Casey is so busy trying to contact the doctor on the phone, he fails to notice that the doctor has anticipated who is calling from the mere urgency of the phone’s ring, made his appearance at the Casey household, and already completed the delivery, as the doctor hands to Casey his bundled offspring while Casey is still on the phone. Casey wheels his pride and joy outside in a baby carriage, and is pleased and amazed when the kid tosses a rattle at him, with the precision of a skilled infielder. Casey substitutes baseball and glove for the rattle, and the kid puts on the glove and handles a catch of the ball as if covering the base for a quick out at first. The child then tosses the ball back to Casey with the speed of a fast-ball pitcher, causing a brief flame to ignite from Casey’s hand. A baseball natural! There’s just one small detail Casey has overlooked, and Mrs. Casey can’t seem to get a word in edgewise to explain it to him. Only when Casey first assists in a change of diapers does he discover that his miracle child is not exactly what he thought – but a girl! Immediately upon this revelation, another dark cloud appears from nowhere in the sky above the Casey house, and rain pours down upon Casey’s world again.

If at first you don’t succeed. Casey and the Mrs. get busy again (offscreen, of course), and soon another whisper, and another baby, are on the way. In fact, this time, triplets! But – – three girls. Above, three rain clouds appear to drown Casey’s sorrows. More time passes, and Casey’s batting average is depicted in the form of a scoreboard, between Boys vs. Girls. The tally for boys displays a no-hit shutout, while the girls’ chalk up a whopping score of nine. With a line of daughters of ascending to descending ages in tow, even Casey realizes, as the narrator observes, “There comes a time to quit.” The rain continues to fall over the Casey household, as Caset dries his tears in the only towel they possess marked “His” instead of “Hers”. But some of Casey’s old cronies down at a village tavern come to a surprising observation regarding the Casey family, and one of them hastens to Casey to suggest a proposition. He tells Casey to look in his own window and take note of what is going on right under his nose. Inside, the girls are busy with routine household chores, such as washing dishes and cleaning up the rooms. However, their moves as they pass plates, wash, dry, etc. are all in the style of baseball plays, assuming all roles of pitcher, catcher, batter, runner, and fielder. Nine daughters, all with such skills, equals – a ladies’ baseball team! The sun is out again, as Casey becomes the impetus to place Mudville into a brand-new baseball league, and the old stadium is renovated to become the home of the Caseyettes. Casey himself poses for a publicity photo with his newly-outfitted team, in a shirt reading “Manager – Coach – Father.” The Caseyettes seem unstoppable, and soon vie for the league championship. Casey, however, is so busy taking bows at the gate, that he finds himself outside the gates as the door closes upon a sold-out crowd.

If at first you don’t succeed. Casey and the Mrs. get busy again (offscreen, of course), and soon another whisper, and another baby, are on the way. In fact, this time, triplets! But – – three girls. Above, three rain clouds appear to drown Casey’s sorrows. More time passes, and Casey’s batting average is depicted in the form of a scoreboard, between Boys vs. Girls. The tally for boys displays a no-hit shutout, while the girls’ chalk up a whopping score of nine. With a line of daughters of ascending to descending ages in tow, even Casey realizes, as the narrator observes, “There comes a time to quit.” The rain continues to fall over the Casey household, as Caset dries his tears in the only towel they possess marked “His” instead of “Hers”. But some of Casey’s old cronies down at a village tavern come to a surprising observation regarding the Casey family, and one of them hastens to Casey to suggest a proposition. He tells Casey to look in his own window and take note of what is going on right under his nose. Inside, the girls are busy with routine household chores, such as washing dishes and cleaning up the rooms. However, their moves as they pass plates, wash, dry, etc. are all in the style of baseball plays, assuming all roles of pitcher, catcher, batter, runner, and fielder. Nine daughters, all with such skills, equals – a ladies’ baseball team! The sun is out again, as Casey becomes the impetus to place Mudville into a brand-new baseball league, and the old stadium is renovated to become the home of the Caseyettes. Casey himself poses for a publicity photo with his newly-outfitted team, in a shirt reading “Manager – Coach – Father.” The Caseyettes seem unstoppable, and soon vie for the league championship. Casey, however, is so busy taking bows at the gate, that he finds himself outside the gates as the door closes upon a sold-out crowd.

A comic sequence of rapid-fire gags follows as Casey attempts to break-in to his own game, finally tearing down a portion of the outfield fence in frantic action in order to join his team. The game has already progressed in his absence, and is in the final inning, with a similar situation and need for a clutch hit as in Casey’s final game of old. The Caseyettes’ power-hitter, Mighty Patsy, is advancing to the plate – but is suddenly pulled from the game. Nervous Casey, afraid that the pennant will be lost at this crucial moment, unwisely attempts to break the rules, by appearing himself as a pinch-hitter in dress and red wig. Casey fails to figure his own past ineptness into the equation, and two strikes are quickly recorded, one from his wig falling down over his eyes, the second from his dress slipping down to expose his male trousers underneath. The final pitch sails at him, and once again the air is shattered by the force of Casey’s blow – another swing through thin air, that misses the ball entirely. However, as Casey’s appearance was a violation of rule anyway, Patsy appears directly behind Casey, to legally address the third pitch, pounding it a resounding blow that launches it over the fence. For once, Mudville has reason to smile, and cheer. As a final touch to his last appearance on the playing field, although Patsy legally rounds the bags to achieve the final winning run. Great Casey, a few steps ahead of her, also runs the bases.

A comic sequence of rapid-fire gags follows as Casey attempts to break-in to his own game, finally tearing down a portion of the outfield fence in frantic action in order to join his team. The game has already progressed in his absence, and is in the final inning, with a similar situation and need for a clutch hit as in Casey’s final game of old. The Caseyettes’ power-hitter, Mighty Patsy, is advancing to the plate – but is suddenly pulled from the game. Nervous Casey, afraid that the pennant will be lost at this crucial moment, unwisely attempts to break the rules, by appearing himself as a pinch-hitter in dress and red wig. Casey fails to figure his own past ineptness into the equation, and two strikes are quickly recorded, one from his wig falling down over his eyes, the second from his dress slipping down to expose his male trousers underneath. The final pitch sails at him, and once again the air is shattered by the force of Casey’s blow – another swing through thin air, that misses the ball entirely. However, as Casey’s appearance was a violation of rule anyway, Patsy appears directly behind Casey, to legally address the third pitch, pounding it a resounding blow that launches it over the fence. For once, Mudville has reason to smile, and cheer. As a final touch to his last appearance on the playing field, although Patsy legally rounds the bags to achieve the final winning run. Great Casey, a few steps ahead of her, also runs the bases.

Yankee Doodle Bugs (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 8/28/54 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Another patriotic title, also previously featured in my “Revolutionary Article” series. Bugs attempts to privately-tutor his nephew Clyde upon American history in preparation for a big exam, touching upon spoofs of many key events of the Revolutionary days. Among these is another visit with Benjamin Franklin and his kite. Bugs is asked to take up the spool of wire and man the flight of Ben’s kite, allowing Ben to take a break to turn out the first edition of Ye Saturday Evening Post. The inevitable bolt of lightning hits the kite, and Bugs becomes lit up by the current as if a blinking light bulb. Ben reappears, carrying the supercharged Bugs into his shop, and shouting “I’ve discovered electricity!” “Heh. HE’S discovered electricity”, the blinking Bugs grumbles. Needless to say, after Bugs’ tutoring, Clyde returns home from his test with a looming scowl on his face. When Bugs asks how did the test go, Clyde produces a dunce cap and places it on his own head. “Does this answer your question?”

Yankee Doodle Bugs (Warner, Bugs Bunny, 8/28/54 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.) – Another patriotic title, also previously featured in my “Revolutionary Article” series. Bugs attempts to privately-tutor his nephew Clyde upon American history in preparation for a big exam, touching upon spoofs of many key events of the Revolutionary days. Among these is another visit with Benjamin Franklin and his kite. Bugs is asked to take up the spool of wire and man the flight of Ben’s kite, allowing Ben to take a break to turn out the first edition of Ye Saturday Evening Post. The inevitable bolt of lightning hits the kite, and Bugs becomes lit up by the current as if a blinking light bulb. Ben reappears, carrying the supercharged Bugs into his shop, and shouting “I’ve discovered electricity!” “Heh. HE’S discovered electricity”, the blinking Bugs grumbles. Needless to say, after Bugs’ tutoring, Clyde returns home from his test with a looming scowl on his face. When Bugs asks how did the test go, Clyde produces a dunce cap and places it on his own head. “Does this answer your question?”

Fido Beta Kappa (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon,10/29/54 – I Sparber, dir.) – A dog accompanies his master on a hunting trip. He is definitely not the brightest bulb on the electric line, as he has no idea what the meaning is of his master’s command, “retrieve” when the hunter downs a duck on the lake – and instead returns to him a fish. When the master encounters a grizzly bear face to face, the dog, instead of fetching the master’s rifle when commanded, brings him back a crooked stick, which snaps apart in the master’s hands. Both man and dog beat a hasty retreat home, “bearly” escaping with their lives. The angry master threatens to send the pooch to the dog pound. But the dog pleads for understanding, informing the master that he was brought up in the gutter, and never received any sort of education. “Your story has touched my heart” admits the master, who instead decides to send the dog to college – at Dog Gone U.

Fido Beta Kappa (Paramount/Famous, Noveltoon,10/29/54 – I Sparber, dir.) – A dog accompanies his master on a hunting trip. He is definitely not the brightest bulb on the electric line, as he has no idea what the meaning is of his master’s command, “retrieve” when the hunter downs a duck on the lake – and instead returns to him a fish. When the master encounters a grizzly bear face to face, the dog, instead of fetching the master’s rifle when commanded, brings him back a crooked stick, which snaps apart in the master’s hands. Both man and dog beat a hasty retreat home, “bearly” escaping with their lives. The angry master threatens to send the pooch to the dog pound. But the dog pleads for understanding, informing the master that he was brought up in the gutter, and never received any sort of education. “Your story has touched my heart” admits the master, who instead decides to send the dog to college – at Dog Gone U.

After passage of time, a knock at the door of the home reveals the dog, returned from college, wearing a graduation gown and mortarboard, and carrying a key and diploma, indicating his achievement of Fido Beta Kappa, and Summa Cum Laude (with highest honors). “I did not go to college to play football”, he adds. Skeptical, his master begins to test his knowledge with a simple task – retrieve a stick. “Your stick is obsolete”, says the dog, handing him instead a stick of modern and scientific design – a boomerang. The master throws it out the door, and orders the dog to retrieve it. The dog merely opens a window on the opposite side of the house, and allows the boomerang to return, making a direct hit on the master’s jaw, and lodging itself in his mouth as an upward-bent smile. “Your stick is retrieved”, says the dog. A second test sets the dog to guard a safe at night against burglars. “They do not call me Martin Kanine for nothing” (a play-on-words on the character name Martin Kane, from a popular detective show). The master steps into his bedroom, but cautiously peers out after a moment, seeing the dog apparently sound asleep, resting his head on the side of the safe. The master dons a burglar’s outfit to teach him a lesson, quietly tiptoes to the safe, and opens it. To his surprise, he finds a very-awake Martin inside the safe, dressed in the garb of a Sherlock Holmes detective, and pointing a pistol at him. “You were clever, Raffles” says Martin, pulling the trigger to release a spring-loaded boxing glove in his master’s face, then concluding his sentence as he walks over to his seemingly sleeping duplicate, to reveal that it is only a dummy in his college robes – “but nor clever enough for Scotland Yard.”

After passage of time, a knock at the door of the home reveals the dog, returned from college, wearing a graduation gown and mortarboard, and carrying a key and diploma, indicating his achievement of Fido Beta Kappa, and Summa Cum Laude (with highest honors). “I did not go to college to play football”, he adds. Skeptical, his master begins to test his knowledge with a simple task – retrieve a stick. “Your stick is obsolete”, says the dog, handing him instead a stick of modern and scientific design – a boomerang. The master throws it out the door, and orders the dog to retrieve it. The dog merely opens a window on the opposite side of the house, and allows the boomerang to return, making a direct hit on the master’s jaw, and lodging itself in his mouth as an upward-bent smile. “Your stick is retrieved”, says the dog. A second test sets the dog to guard a safe at night against burglars. “They do not call me Martin Kanine for nothing” (a play-on-words on the character name Martin Kane, from a popular detective show). The master steps into his bedroom, but cautiously peers out after a moment, seeing the dog apparently sound asleep, resting his head on the side of the safe. The master dons a burglar’s outfit to teach him a lesson, quietly tiptoes to the safe, and opens it. To his surprise, he finds a very-awake Martin inside the safe, dressed in the garb of a Sherlock Holmes detective, and pointing a pistol at him. “You were clever, Raffles” says Martin, pulling the trigger to release a spring-loaded boxing glove in his master’s face, then concluding his sentence as he walks over to his seemingly sleeping duplicate, to reveal that it is only a dummy in his college robes – “but nor clever enough for Scotland Yard.”

Now, Martin takes his master out for a lesson in scientific duck hunting. The marsh is covered in dense fog, and the master insists you can’t hunt ducks in such weather. Martin disagrees, producing a tuning fork that is designed to vibrate when the air is disturbed by the frequencies of flapping duck wings. Based upon its vibration rate, Martin can discern the presence of a flock of ducks when they are three miles away – and the precise moment when they are directly overhead. He tells his master to shoot now, and the rifle is fired once into the air. A pause, and nothing happens. Then, the entire flock of ducks tumbles down in a heap upon the master’s shoulders. However, this bountiful hunting is disturbed by a flash of lightning. Quoting statistics of how many people are killed by lightning strikes each year, Martin suggests, “We’d best hurry home, sir.” They race to get out of the woods, but are stopped cold when a tall tree just ahead of them is split in two by a direct hit from a thunderbolt. Martin shockingly jumps directly into the crotch of the split tree, and stands his ground. “Hey, wise guy. Trying to kill yourself?”, asks the master. “Lightning never strikes twice in the same place”, responds a confident Martin. Abruptly, the master tells him to beat it, knocking him away to one side, and takes Martin’s place atop the split tree. “He hasn’t been wrong yet”, he tells the audience – which is no sooner said than a second lightning bolt scores a direct hit on the master, also splitting him in two. Martin is astounded by this seemingly impossible phenomenon – nut rather than express any remorse at the loss of his master, he merely ponders in entirely academic fashion, “Hmm. I shall speak to my professor about that.”

Now, Martin takes his master out for a lesson in scientific duck hunting. The marsh is covered in dense fog, and the master insists you can’t hunt ducks in such weather. Martin disagrees, producing a tuning fork that is designed to vibrate when the air is disturbed by the frequencies of flapping duck wings. Based upon its vibration rate, Martin can discern the presence of a flock of ducks when they are three miles away – and the precise moment when they are directly overhead. He tells his master to shoot now, and the rifle is fired once into the air. A pause, and nothing happens. Then, the entire flock of ducks tumbles down in a heap upon the master’s shoulders. However, this bountiful hunting is disturbed by a flash of lightning. Quoting statistics of how many people are killed by lightning strikes each year, Martin suggests, “We’d best hurry home, sir.” They race to get out of the woods, but are stopped cold when a tall tree just ahead of them is split in two by a direct hit from a thunderbolt. Martin shockingly jumps directly into the crotch of the split tree, and stands his ground. “Hey, wise guy. Trying to kill yourself?”, asks the master. “Lightning never strikes twice in the same place”, responds a confident Martin. Abruptly, the master tells him to beat it, knocking him away to one side, and takes Martin’s place atop the split tree. “He hasn’t been wrong yet”, he tells the audience – which is no sooner said than a second lightning bolt scores a direct hit on the master, also splitting him in two. Martin is astounded by this seemingly impossible phenomenon – nut rather than express any remorse at the loss of his master, he merely ponders in entirely academic fashion, “Hmm. I shall speak to my professor about that.”

Helter Shelter (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 1/17/55 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – This one feels like Smith’s answer to Bugs Bunny’s “Hare Force”, with less style and laughs. Woody Woodpecker has just pecked out a new home in a tree. A troublemaking dog named “Happy” decides just for fun to set fire to the trunk, reducing the place to outlines. Woody finds a vacant birdhouse, pecking his name over the entrance. The dog saws off the pole on which the house is mounted, and tosses the whole thing over a cliff. As the first drops of a rainstorm begin to fall, the snickering dog is “happy” that he has a comfortable doghouse to go home to. But Woody retaliates, by pecking the thing apart. As the rain increases, there is nothing for either of them to do but impose upon the human owners of the property. Kindly Phoebe, an old woman, takes them both in, but her husband, a grumpy, burly fellow who oddly appears to be half of Phoebe’s age, is an animal hater, and remarks, “What is this? A zoo?” He grumbles his way off to bed, while Woody and the dog are left together for the evening. Of course, each would like nothing better than to cut each other’s throat. The same kind of battle to see who can throw who out of this happy home as seen in the Bugs cartoon ensues – punctuated with some interference by the grumpy man, who is a sleep-eater, and almost consumes the both of them, as he mistakes them for a roast turkey and a bottle of catsup. One gag predicts a similar one from Chick Jones, as Happy outfoxes Woody by knocking on the window from outside, then leaping on a loose porch floorboard as Woody approaches the window, catapulting Woody on the other end of the loose board up through the ceiling. Woody states he knows when he’s licked, but that the dog will need evidence to get him thrown out. Handing Happy a camera, Woody pecks apart one leg of the master’s bed, sliding the master out the window, while Happy snaps a photograph. The master re-enters the house drenched, as Happy emerges from a dark room with the photo. Unexplainedly, the photo shows no sign of Woody – instead altered to show Happy sawing the bedpost in two. Another mishap with some added complications by Woody causes Happy to swallow the saw, which begins popping up randomly inside his head and limbs, then everywhere at once, as he bounces his way helplessly down a country road. But the grumpy master throws Woody out too. Similar to “Hare Force”, the master reacts to Phoebe’s complaints “Either that woodpecker goes, or I go” – and himself gets thrown out onto the cold by Phoebe. The film ends without a capper punchline, as Woody is gently tucked into bed by Phoebe, and responds, “You’re a nice lady.”

Helter Shelter (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 1/17/55 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) – This one feels like Smith’s answer to Bugs Bunny’s “Hare Force”, with less style and laughs. Woody Woodpecker has just pecked out a new home in a tree. A troublemaking dog named “Happy” decides just for fun to set fire to the trunk, reducing the place to outlines. Woody finds a vacant birdhouse, pecking his name over the entrance. The dog saws off the pole on which the house is mounted, and tosses the whole thing over a cliff. As the first drops of a rainstorm begin to fall, the snickering dog is “happy” that he has a comfortable doghouse to go home to. But Woody retaliates, by pecking the thing apart. As the rain increases, there is nothing for either of them to do but impose upon the human owners of the property. Kindly Phoebe, an old woman, takes them both in, but her husband, a grumpy, burly fellow who oddly appears to be half of Phoebe’s age, is an animal hater, and remarks, “What is this? A zoo?” He grumbles his way off to bed, while Woody and the dog are left together for the evening. Of course, each would like nothing better than to cut each other’s throat. The same kind of battle to see who can throw who out of this happy home as seen in the Bugs cartoon ensues – punctuated with some interference by the grumpy man, who is a sleep-eater, and almost consumes the both of them, as he mistakes them for a roast turkey and a bottle of catsup. One gag predicts a similar one from Chick Jones, as Happy outfoxes Woody by knocking on the window from outside, then leaping on a loose porch floorboard as Woody approaches the window, catapulting Woody on the other end of the loose board up through the ceiling. Woody states he knows when he’s licked, but that the dog will need evidence to get him thrown out. Handing Happy a camera, Woody pecks apart one leg of the master’s bed, sliding the master out the window, while Happy snaps a photograph. The master re-enters the house drenched, as Happy emerges from a dark room with the photo. Unexplainedly, the photo shows no sign of Woody – instead altered to show Happy sawing the bedpost in two. Another mishap with some added complications by Woody causes Happy to swallow the saw, which begins popping up randomly inside his head and limbs, then everywhere at once, as he bounces his way helplessly down a country road. But the grumpy master throws Woody out too. Similar to “Hare Force”, the master reacts to Phoebe’s complaints “Either that woodpecker goes, or I go” – and himself gets thrown out onto the cold by Phoebe. The film ends without a capper punchline, as Woody is gently tucked into bed by Phoebe, and responds, “You’re a nice lady.”

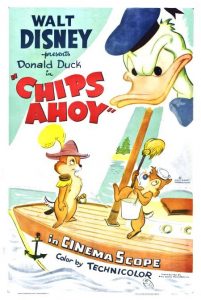

Honorable mention for Chips Ahoy (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 2/24/56 – Jack Kinney, dir.), a derivative yet reasonably memorable finale to the theatrical careers of Chip ‘n’ Dale, and their only appearance in Cinemascope. Following in the pattern of “Out of Scale” and “test Pilot Donald”, Chip and Dale again enter the world of miniaturized transportation, shifting from scale-model locomotives and planes to ships. Donald is as usual the scale-modeler whose masterpiece is hijacked off a shelf, with the chipmunks’ motivation being to reach an acorn-laden tree on an island in the center of a lake. Much of the plot is superfluous, as the most memorable aspects of the film seem to be how cute the chipmunks look in sailor’s hat and admiral’s uniform. For purposes of the present trail, Donald again gets to play scale “weatherman”, making things difficult for the chipmunks by staging a fake storm at sea. With the aid or a tomato can to pour water into the hold and splash same over the bow, an empty fuel can to kick for thunder sound effect, cigar smoke to substitute as fog, and some vigorous rocking of the ship as it is held high and dry above the water in Donald’s hands, the two chipmunks are forced to man the pumps, and Dale develops a bad case of mal-de-mer. As he races for the railing’s edge to relieve himself (we are not shown whether Dale actually throws up on Donald’s feet), Dale gets a view over the side, spotting Donald holding the ship up in the air. He reports back to skipper Chip, “Man overboard.” The chipmunks race into the ship’s cabin, shutting the hatch upon Donald’s finger. Donald produces a boatswain’s whistle, and calls out the command, “All hands on deck.” Gullible Dale follows orders, emerging from the cabin, to be grabbed up in Donald’s hand.

Honorable mention for Chips Ahoy (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 2/24/56 – Jack Kinney, dir.), a derivative yet reasonably memorable finale to the theatrical careers of Chip ‘n’ Dale, and their only appearance in Cinemascope. Following in the pattern of “Out of Scale” and “test Pilot Donald”, Chip and Dale again enter the world of miniaturized transportation, shifting from scale-model locomotives and planes to ships. Donald is as usual the scale-modeler whose masterpiece is hijacked off a shelf, with the chipmunks’ motivation being to reach an acorn-laden tree on an island in the center of a lake. Much of the plot is superfluous, as the most memorable aspects of the film seem to be how cute the chipmunks look in sailor’s hat and admiral’s uniform. For purposes of the present trail, Donald again gets to play scale “weatherman”, making things difficult for the chipmunks by staging a fake storm at sea. With the aid or a tomato can to pour water into the hold and splash same over the bow, an empty fuel can to kick for thunder sound effect, cigar smoke to substitute as fog, and some vigorous rocking of the ship as it is held high and dry above the water in Donald’s hands, the two chipmunks are forced to man the pumps, and Dale develops a bad case of mal-de-mer. As he races for the railing’s edge to relieve himself (we are not shown whether Dale actually throws up on Donald’s feet), Dale gets a view over the side, spotting Donald holding the ship up in the air. He reports back to skipper Chip, “Man overboard.” The chipmunks race into the ship’s cabin, shutting the hatch upon Donald’s finger. Donald produces a boatswain’s whistle, and calls out the command, “All hands on deck.” Gullible Dale follows orders, emerging from the cabin, to be grabbed up in Donald’s hand.

Chip retaliates, dropping the ship’s anchor on Donald’s foot. As Donald breaks into his standard temper tantrum, Dale tosses a loop of rope around him from the dock, causing Donald to temporarily tie himself in knots. The film’s finale, however, falls somewhat flat from its sheer improbability. Without any appropriate elapsing of time, Dale hails Chip for a quick pick-up to join Chip on the boat again – yet, in the passing of no more than a few seconds on screen, we are supposed to believe that Dale has managed miraculous sabotages of every other floating craft on the lake. Donald boards a full-sized sailboat to pursue the chips’ vessel. Dale shows no fear, lounging on the toy boat’s deck playing a ukelele. Why? Donald finds a huge hole cut through the canvas of his sail, courtesy of a scissor Dale has carried with him, within a secret compartment of his fur. Donald clambers into a canoe, but Dale, loaded with handy tools, has beat him to the punch again, by filling its hull with holes via a hand-drill. Donald tries out a rowboat for size, but Dale has pried the nails out of its boards, causing it to fall apart. Finally, Donald jumps into a motorboat, revving up the engine for a charge with a harpoon. Dale displays to Chip a convenient book of knots he has been studying. Donald’s vessel is firmly moored to the dock, and when it reaches rope’s end, stops cold, casting Donald through the air, past the chipmunks’ ship, and head-on into the acorn tree, Acorns fall everywhere, including into the hold and on deck of the chipmunks’ ship, where they pile high. “What a cargo”, celebrate the chipmunks. A last leap at them by Donald merely produces a wave that propels the chipmunks home. The final shot also seems to “fish” for an ending, leaving the eventual outcome enigmatic, as Donald succeeds with some rudimentary tools of his own in chopping down the acorn tree, and sets to work fashioning a new rowboat from its trunk, which the film suggest might possibly take forever. (Why, actually, couldn’t Donald just float home on the fallen log, without wasting the time on whittling?)

Chip retaliates, dropping the ship’s anchor on Donald’s foot. As Donald breaks into his standard temper tantrum, Dale tosses a loop of rope around him from the dock, causing Donald to temporarily tie himself in knots. The film’s finale, however, falls somewhat flat from its sheer improbability. Without any appropriate elapsing of time, Dale hails Chip for a quick pick-up to join Chip on the boat again – yet, in the passing of no more than a few seconds on screen, we are supposed to believe that Dale has managed miraculous sabotages of every other floating craft on the lake. Donald boards a full-sized sailboat to pursue the chips’ vessel. Dale shows no fear, lounging on the toy boat’s deck playing a ukelele. Why? Donald finds a huge hole cut through the canvas of his sail, courtesy of a scissor Dale has carried with him, within a secret compartment of his fur. Donald clambers into a canoe, but Dale, loaded with handy tools, has beat him to the punch again, by filling its hull with holes via a hand-drill. Donald tries out a rowboat for size, but Dale has pried the nails out of its boards, causing it to fall apart. Finally, Donald jumps into a motorboat, revving up the engine for a charge with a harpoon. Dale displays to Chip a convenient book of knots he has been studying. Donald’s vessel is firmly moored to the dock, and when it reaches rope’s end, stops cold, casting Donald through the air, past the chipmunks’ ship, and head-on into the acorn tree, Acorns fall everywhere, including into the hold and on deck of the chipmunks’ ship, where they pile high. “What a cargo”, celebrate the chipmunks. A last leap at them by Donald merely produces a wave that propels the chipmunks home. The final shot also seems to “fish” for an ending, leaving the eventual outcome enigmatic, as Donald succeeds with some rudimentary tools of his own in chopping down the acorn tree, and sets to work fashioning a new rowboat from its trunk, which the film suggest might possibly take forever. (Why, actually, couldn’t Donald just float home on the fallen log, without wasting the time on whittling?)

As with Out of Scale, this story was adapted into a long-selling Little Golden Book, “Donald Duck’s Toy Sailboat”, without the convoluted ending. It was the first book I ever learned to read, and memorized from cover to cover. When I finally saw the film, it was a disappointment to my expectations. The book quote that most sticks in my head was “The chipmunks worked with might and main, while Donald watched and laughed.”

More drips from the latter half of the decade, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

What we’re seeing here this week is a stark decline in the art of effects animation in general. “Fudget’s Budget” is ahead of the curve: we can only tell that the tangle of geometric cross-hatching is meant to be “rain” because the narrator tells us it is.

“Casey Bats Again” is rather bittersweet in that it represents the last work of animator Fred Moore, who was killed in an automobile accident a year and a half before the cartoon was released. At least his final project allowed him to animate a girls’ baseball team. No one else at Disney could have done it better.

“Chips Ahoy” seems to antedate the chocolate chip cookie brand of the same name by several years. Funny, because I can only keep the chipmunks straight by remembering that Chip has the dark nose, i.e.: “chocolate Chip”.

It gives me pause to reflect that the funniest cartoon this week is a Paul J. Smith Woody Woodpecker. But with a strong story by Michael Maltese to work with, he couldn’t go wrong.

I like Casey Bats Again the most here.

I should point out that the reason why “Helter Shelter” felt similar to “Hare Force” was because both were written by Micheal Maltese.

“Hare Force” was written by Tedd Pierce, not Mike Maltese.

I like “Casey Bats Again” because the girls in the ball team all look somewhat like Hilda Terry’s Teena, a comic strip character of yore whom I wish would get some sort of animation treatment, such as the holiday movie I have in mind fir her.

Thank you, Mr Gardner, for revealing the mystery ending of “How To Keep Cool”. I was always baffled by the non-ending I saw on television, and now I know. In fact I had the same reaction to an illogical jump cut in “Helter Shelter” when I first saw it on NBC in mid 70s, but in this case, syndication allowed me to see Woody and Happy commit the same forbidden act as did Dimwit.

In “The Tall Tale Teller” (Terrytoons, 1954 — Connie Rasinski, dir.), tall tale teller Phony Baloney recounts his discovery of the fountain of youth, much as he did the tale of his shipwreck in “Robinson Crusoe’s Broadcast” sixteen years earlier. While he is exploring in the Everglades, “Suddenly a storm broke,” with flashes of lightning and heavy rain, “but a kindly creature offered me shelter.” The “kindly creature” is a turtle that Phony forcibly evicts from its shell, taking its place within. “The rain soon stopped,” he goes on, “but my troubles continued….” At least he has pleasant weather to deal with for the remainder of the cartoon.

“Snegurochka [The Snow Maiden]” (Soyuzmultfilm, 2/2/52 — Ivan Ivanov-Vano, dir.) is an animated feature based on a traditional Russian folk tale, with music from Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera of the same name. The music and visuals are gorgeous, and most of the animation is rotoscoped, as was generally the case with Soyuzmultfilm productions of this period. Like Rimsky-Korsakov’s other fairy tale operas, however, the story is hard to follow for non-Russians who didn’t learn it as children. Be that as it may, there is quite a lot of snow in the beginning of the picture, as you’d expect from a Russian story about the changing of the seasons.