The storm clouds miss no one today – as every one of the major producing studios appears in today’s 1943-44 survey. An excerpt from another Disney feature is included, along with visits from Donald Duck, Popeye, Barney Bear, Private Snafu, and Mighty Mouse – and a Tex Avery classic.

Bah Wilderness (MGM, Barney Bear, 2/13/43 – Rudolf Ising, dir.) – Barney, although already a creature of the woods, tries his hand at “roughing it” outside of his cave in the expanse of the great outdoors. He makes camp with all the modern conveniences, including portable radio, flashlight, and, most important of all, a Snuggly-Wuggly inflatable air mattress. Barney experiences some embarrassing moments when he tries to change out of his pants into a nightshirt, but discovers seemingly every eye in the forest upon him from the shadows. Turning his flashlight toward the darkness, woodland creatures of every species are revealed eyeing the stranger. Barney tosses his flashlight at them, and believes he has scared them all away. But a remaining chipmunk steps on the flashlight switch, putting the spotlight on Barney at the most revealing time. A porcupine creeps under Barney’s blanket, and as the bear snuggles down, he acquires half the quills off the animal’s body into his rear end. Barney sets an array of traps ranging from bear traps (???) to mousetraps around his camp, bit is rudely awakened when another critter turns on his radio, just outside the trap ring. Barney rises in a hurry, and is ensnared in his own traps. As 1:00 a.m. is announced on the radio, the soothing tones of the “Lullaby Lady” finally lull the bear to sleep – but with the inflation tube of the air mattress sucked into his mouth. With every snore, he blows more air into the mattress, until he is several stories off the ground, and the mattress explodes. As a final insult, the skies open up in a rainstorm, lightning using the old gag of opening the clouds like a zipper to produce a flash flood, which submerges Barney, the campsite, and the forest under four feet of water. With Ising repeating the same ending from his partner’s earlier Bear cartoon, “A Rainy Day”, Barney resigns himself to turning over and sleeping underwater, as his radio sinks below the surface from above, gargling its last syllables as it submerges.

Bah Wilderness (MGM, Barney Bear, 2/13/43 – Rudolf Ising, dir.) – Barney, although already a creature of the woods, tries his hand at “roughing it” outside of his cave in the expanse of the great outdoors. He makes camp with all the modern conveniences, including portable radio, flashlight, and, most important of all, a Snuggly-Wuggly inflatable air mattress. Barney experiences some embarrassing moments when he tries to change out of his pants into a nightshirt, but discovers seemingly every eye in the forest upon him from the shadows. Turning his flashlight toward the darkness, woodland creatures of every species are revealed eyeing the stranger. Barney tosses his flashlight at them, and believes he has scared them all away. But a remaining chipmunk steps on the flashlight switch, putting the spotlight on Barney at the most revealing time. A porcupine creeps under Barney’s blanket, and as the bear snuggles down, he acquires half the quills off the animal’s body into his rear end. Barney sets an array of traps ranging from bear traps (???) to mousetraps around his camp, bit is rudely awakened when another critter turns on his radio, just outside the trap ring. Barney rises in a hurry, and is ensnared in his own traps. As 1:00 a.m. is announced on the radio, the soothing tones of the “Lullaby Lady” finally lull the bear to sleep – but with the inflation tube of the air mattress sucked into his mouth. With every snore, he blows more air into the mattress, until he is several stories off the ground, and the mattress explodes. As a final insult, the skies open up in a rainstorm, lightning using the old gag of opening the clouds like a zipper to produce a flash flood, which submerges Barney, the campsite, and the forest under four feet of water. With Ising repeating the same ending from his partner’s earlier Bear cartoon, “A Rainy Day”, Barney resigns himself to turning over and sleeping underwater, as his radio sinks below the surface from above, gargling its last syllables as it submerges.

Pedro (from “Saludos Amigos”) (Disney/RKO, 2/6/43 – Hamilton Luske, dir.) – Call it, if you will, the “pilot” for Disney’s feature, “Planes” – the original effort to inhabit a world almost entirely with living aircraft. Tex Avery would take a leaf from it several years later with “Little Johnny Jet.” It would also spawn such other Disney worlds of the inanimate as “Little Toot” and “Susie, the Little Blue Coupe”.

Pedro (from “Saludos Amigos”) (Disney/RKO, 2/6/43 – Hamilton Luske, dir.) – Call it, if you will, the “pilot” for Disney’s feature, “Planes” – the original effort to inhabit a world almost entirely with living aircraft. Tex Avery would take a leaf from it several years later with “Little Johnny Jet.” It would also spawn such other Disney worlds of the inanimate as “Little Toot” and “Susie, the Little Blue Coupe”.

Set in Santiago, Chile (to promote the wartime “Good Neighbor Policy”), a family of planes resides at an airfield for delivery of mail across the Andes mountains to Mendoza, Argentina. A papa plane who carries the mail, a mama plane, and little Pedro, who is still nursing from a gasoline pump shaped like a baby bottle. Pedro attends Ground School, learning the basics such as reading, skywriting, and arithmetic, plus one of his least favorite subjects – geography. One day, papa develops a cold in his cylinder head. Mama can’t fly the high-altitude flight over the Andes, as she has high oil pressure. So Pedro is chosen for his first solo mission, with warning to stay away from the forbidding peak of Aconcagua. The fledgling flier has difficulty attaining flight speed, and nearly knocks the control tower off its supporting poles. Pedro begins a long spiral ascent upwards to the entrance to a high mountain pass providing his flight route. He gets caught in a surprise downdraft at the pass’s entrance, but pulls out of it quickly like a veteran. His first trip through the pass is largely uneventful, although he gets a glimps of Aconcagua from a distance, and tiptoes past it, concealed inside a small cloud. Spiraling down to Mendoza, he receives a mail pouch, which he carries on one wing. Hearing encouraging compliments from the film’s narrator about being ahead of schedule, Pedro begins showing off with some aerial acrobatics – then comes face to face with a buzzard, who gives him a little razz, then turns tail on him. Pedro playfully gives chase after the bird into a dark canyon, forgetting his mission.

He suddenly finds himself staring into the face of the dreaded Aconcagua, and remembers the warnings of its violent downdrafts and sudden storms. He endures a frightening ordeal of lightning strikes, fierce winds, and blinding rain. The mail pouch slips from his wing, and while the narrator tells him to forget it and save himself, Pedro power dives in determination to catch the sack, finally retrieving it, but at a cost. He has used up most of his fuel, and now sputters and coughs in the desperate attempt to rise above the storm to safety. The scene fades as do our hopes for Pedro, as his engine begins stalling, Pedro being dragged back down, down, down into the clouds. At the airfield in Santiago, searchlights scan the skies for him, but find nothing, as Mama and Papa wait tearfully, believing their son lost. Just as the lights begin shutting down to give up the search, a small sputtering sound of an engine is heard. A light is turned back on, and follows the sound of multiple bounces upon the runway. Pedro is found, upside down on his back, but in one piece, and with the mail pouch safely brought in upon his wing. The camera closes in on the pouch’s contents, consisting of a single postcard, translating to “Having wonderful time. Wish you were here.” The narrator mutters, “Well, it might have been important…”, as Pedro happily wags his tail at completing his mission.

He suddenly finds himself staring into the face of the dreaded Aconcagua, and remembers the warnings of its violent downdrafts and sudden storms. He endures a frightening ordeal of lightning strikes, fierce winds, and blinding rain. The mail pouch slips from his wing, and while the narrator tells him to forget it and save himself, Pedro power dives in determination to catch the sack, finally retrieving it, but at a cost. He has used up most of his fuel, and now sputters and coughs in the desperate attempt to rise above the storm to safety. The scene fades as do our hopes for Pedro, as his engine begins stalling, Pedro being dragged back down, down, down into the clouds. At the airfield in Santiago, searchlights scan the skies for him, but find nothing, as Mama and Papa wait tearfully, believing their son lost. Just as the lights begin shutting down to give up the search, a small sputtering sound of an engine is heard. A light is turned back on, and follows the sound of multiple bounces upon the runway. Pedro is found, upside down on his back, but in one piece, and with the mail pouch safely brought in upon his wing. The camera closes in on the pouch’s contents, consisting of a single postcard, translating to “Having wonderful time. Wish you were here.” The narrator mutters, “Well, it might have been important…”, as Pedro happily wags his tail at completing his mission.

Fall Out, Fall In (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 4/23.43 – Jack King, dir.) – Perhaps one of the funniest, and most timeless, cartoons ever produced about army life, which feels like it still works flawlessly 80 years later. Donald Duck is an infantry man – that is, duck – assigned to the ever-dreaded task of a long-distance hike with his platoon. As the rooster crows at the crack of dawn, they are already on the march (to a splendid and catchy original marching score), with Donald bringing up his appropriate position in the rear. Donald begins the day chipper about the whole thing, beating out the march rhythm with his tail feathers on a tin pan strapped to hs pack, and noting the signposts indicating how many miles they’ve marched from camp, keeping a tally of their progress by drawing slash marks in pencil upon the backpack of the soldier in front of him. 5 miles already. Things start to look a little different when the mileage is doubled to 10. The smile has disappeared from Donald’s face, and one shoulder is beginning to fall out of joint under the weight of his rifle. Shifting the weapon to his other shoulder, Donald’s eyes start to rhythmically bounce with every repeated call of “left” and “right” from the Sergeant. Double the mileage again, as the troops pass a 20-mile road sign. Lightning strikes directly behind it, and a rainstorm begins. The road on which Donald marches quickly reverts to a muddy mess. The raindrops beat a staccato rhythm on Donald’s steel helmet.

Fall Out, Fall In (Disney/RKO, Donald Duck, 4/23.43 – Jack King, dir.) – Perhaps one of the funniest, and most timeless, cartoons ever produced about army life, which feels like it still works flawlessly 80 years later. Donald Duck is an infantry man – that is, duck – assigned to the ever-dreaded task of a long-distance hike with his platoon. As the rooster crows at the crack of dawn, they are already on the march (to a splendid and catchy original marching score), with Donald bringing up his appropriate position in the rear. Donald begins the day chipper about the whole thing, beating out the march rhythm with his tail feathers on a tin pan strapped to hs pack, and noting the signposts indicating how many miles they’ve marched from camp, keeping a tally of their progress by drawing slash marks in pencil upon the backpack of the soldier in front of him. 5 miles already. Things start to look a little different when the mileage is doubled to 10. The smile has disappeared from Donald’s face, and one shoulder is beginning to fall out of joint under the weight of his rifle. Shifting the weapon to his other shoulder, Donald’s eyes start to rhythmically bounce with every repeated call of “left” and “right” from the Sergeant. Double the mileage again, as the troops pass a 20-mile road sign. Lightning strikes directly behind it, and a rainstorm begins. The road on which Donald marches quickly reverts to a muddy mess. The raindrops beat a staccato rhythm on Donald’s steel helmet.

It gets on Donald’s nerves, and he finds a way to break up the rhythm, by using the bayonet on the tip of his rifle to snag the backpack of the soldier ahead of him, propping the pack up like a small roof over Donald’s head. However, the diverted rain merely pours over the upper side of the backpack, trickling down in the rear like a small waterfall onto Donald’s tail. Wringing out his tail feathers, Donald can only solve this side-effect by placing his helmet over his tail for protection. The miles keep piling up to 40, and suddenly Donald finds himself marching through snow-covered hills. Icicles hang from his tail, and each step that Donald takes raises from the ground a ring of snow clinging to his feet. Further progressive steps stick more and more snow rings to his feet, until he is walking upon two towers of them. Then, the snow gives way under his weight, and his feet penetrate through the rings – leaving him looking like he is marching in a white-lace ruffled petticoat. More miles, and Donald faces another weather extreme – a blazing-hot desert terrain. His feet are bright red as they drag across the brittle-dry ground, and even as they find a small watering hole to wade through, evaporating the water from the heat of his webbing. Donald’s head is also as red as we’re used to seeing from his temper tantrums. Steam begins to emerge from a small vent hole in his helmet, emitting the sound of calliope music – and Donald removes the red-hot hat with a stove-lid handle, causing a helmet-shaped accumulation of perspiration to fall out and drench him. As the sun begins to set, the troops have gained new footing along a dusty trail, and as the command to halt is heard, Donald becomes visible among the dust clouds, covered from head to foot in trail dirt. The pencil tally of miles on the back of the soldier ahead of him is now uncountable, extending over the soldier’s entire uniform from head to foot. “Fall out”, yells the sergeant – which Donald does, literally, collapsing backwards out of his dusty coating and plopping with his pack upon the ground.

Mess call is heard. Donald struggles with his pack to find his mess kit, tearing the pack apart to allow all of its contents to fall helter-skelter upon the ground (including the inevitable framed picture of Daisy). He runs in the direction of the aromas of food, but is stopped cold by the voice of the sergeant, who orders him to first pitch his tent. This task proves utterly daunting, as the tent poles and ropes take on the configuration of a quivering bow and arrow, launching Donald headfirst into a tree, and producing a lump which bulges right through his steel helmet. Night falls, and while the rest of the platoon has bedded down for the night, Donald, still without his dinner, struggles in vain to get his tent to stand. Oddly, he seems to be the only dogface in the army who has been issued a tent canvas which isn’t impervious to water, as he gets an idea, and throws a bucket of water upon his sagging tent, causing it to shrink to fit. However, it keeps right on shrinking, until it presses Donald flat to the ground, then splits down the middle in half. Even Donald’s blanket is similarly affected, shrunken to the size of a small dish towel. “Aw, fooey!”, shouts Donald, and decides to settle down to sleep right where he is (taking great pains to tuck the shrunken blanket around his feet, then pulling it up to his chin, exposing his feet entirely). Donald never gets the rest he desires, as soldiers from every division of his platoon keep him awake with signature snores (a bugler sounding like reveille call, a machine gunner sounding like a rat-a-tat-tat, and an artillery man letting off booms like an explosive cannon). Donald breaks into his classic “C’mon and fight” temper tantrum, but doesn’t have the strength to finish it, ultimately collapsing on the ground. Even unconsciousness won’t get him any relief, as a bugle call sounds for everyone to rise and shine. Donald’s half-open eyes note his fellow troopers lining up to the command of “Fall in.” With his backpack still in a state of disarray, Donald decides to waste no time trying to repack it, and simply tosses a large piece of canvas around its contents, then attempts to tie them all to his back with a rope. In his sleepy stupor, the rope he throws around the bundle overshoots its target, and winds around a huge tree directly behind Donald’s equipment. At the command of “Forward, March”, Donald tugs and strains at his load – and uproots the tree, which he carries along with his equipment. A marvelous final shot of Donald marching in perspective with a 40-foot tall tree strapped to his back closes this creative episode, leaving us to only wonder at the shape Donald will be in after another day of this torture.

Mess call is heard. Donald struggles with his pack to find his mess kit, tearing the pack apart to allow all of its contents to fall helter-skelter upon the ground (including the inevitable framed picture of Daisy). He runs in the direction of the aromas of food, but is stopped cold by the voice of the sergeant, who orders him to first pitch his tent. This task proves utterly daunting, as the tent poles and ropes take on the configuration of a quivering bow and arrow, launching Donald headfirst into a tree, and producing a lump which bulges right through his steel helmet. Night falls, and while the rest of the platoon has bedded down for the night, Donald, still without his dinner, struggles in vain to get his tent to stand. Oddly, he seems to be the only dogface in the army who has been issued a tent canvas which isn’t impervious to water, as he gets an idea, and throws a bucket of water upon his sagging tent, causing it to shrink to fit. However, it keeps right on shrinking, until it presses Donald flat to the ground, then splits down the middle in half. Even Donald’s blanket is similarly affected, shrunken to the size of a small dish towel. “Aw, fooey!”, shouts Donald, and decides to settle down to sleep right where he is (taking great pains to tuck the shrunken blanket around his feet, then pulling it up to his chin, exposing his feet entirely). Donald never gets the rest he desires, as soldiers from every division of his platoon keep him awake with signature snores (a bugler sounding like reveille call, a machine gunner sounding like a rat-a-tat-tat, and an artillery man letting off booms like an explosive cannon). Donald breaks into his classic “C’mon and fight” temper tantrum, but doesn’t have the strength to finish it, ultimately collapsing on the ground. Even unconsciousness won’t get him any relief, as a bugle call sounds for everyone to rise and shine. Donald’s half-open eyes note his fellow troopers lining up to the command of “Fall in.” With his backpack still in a state of disarray, Donald decides to waste no time trying to repack it, and simply tosses a large piece of canvas around its contents, then attempts to tie them all to his back with a rope. In his sleepy stupor, the rope he throws around the bundle overshoots its target, and winds around a huge tree directly behind Donald’s equipment. At the command of “Forward, March”, Donald tugs and strains at his load – and uproots the tree, which he carries along with his equipment. A marvelous final shot of Donald marching in perspective with a 40-foot tall tree strapped to his back closes this creative episode, leaving us to only wonder at the shape Donald will be in after another day of this torture.

Dizzy Newsreel (Columbia/Screen Gems, Phantasy, 4/27/43 – Alec Geiss, dir.) – Another spot gag newsreel spoof, but with a few decent gags. A fairly original opening depicts a screen split into four different mini-screens of moving images, with the surprise that a character in screen 1 finds himself in trouble, and jumps to screen 2, then avoids another peril by moving to screen 3, etc. Most of the film consists of gags on the world of sports, including a slow-motion prize fight replay that reveals the champ’s manager intervening to conk the challenger with a black jack, too fast for the referee’s eyes to see. Weather shows up in an item from Broken, Maine, where a groundhog attempts to make his annual weather prediction. Emerging from his weather bureau (a chest of drawers), he sees his shadow, and attempts to recite a prediction – but can’t remember how the jingle goes as to what seeing his shadow is supposed to mean. Asking advice from the narrator, he predicts 40 days of fair weather – and instantly gets rain. We may never know exactly how this cartoon ended, as the only circulating print breaks suddenly from an item on hog calling to the television Screen Gems logo. However, the oriental-sounding orchestration heard over the closing card gives us a pretty fair hint that some wartime gag was censored involving the Japanese. Anyone with information as to the “lost” ending is welcome to contribute.

Dizzy Newsreel (Columbia/Screen Gems, Phantasy, 4/27/43 – Alec Geiss, dir.) – Another spot gag newsreel spoof, but with a few decent gags. A fairly original opening depicts a screen split into four different mini-screens of moving images, with the surprise that a character in screen 1 finds himself in trouble, and jumps to screen 2, then avoids another peril by moving to screen 3, etc. Most of the film consists of gags on the world of sports, including a slow-motion prize fight replay that reveals the champ’s manager intervening to conk the challenger with a black jack, too fast for the referee’s eyes to see. Weather shows up in an item from Broken, Maine, where a groundhog attempts to make his annual weather prediction. Emerging from his weather bureau (a chest of drawers), he sees his shadow, and attempts to recite a prediction – but can’t remember how the jingle goes as to what seeing his shadow is supposed to mean. Asking advice from the narrator, he predicts 40 days of fair weather – and instantly gets rain. We may never know exactly how this cartoon ended, as the only circulating print breaks suddenly from an item on hog calling to the television Screen Gems logo. However, the oriental-sounding orchestration heard over the closing card gives us a pretty fair hint that some wartime gag was censored involving the Japanese. Anyone with information as to the “lost” ending is welcome to contribute.

Ration Fer the Duration (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 5/28/43 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) receives honorable mention for a brief but memorable throwaway gag involving weather. Popeye, just planting his own garden of spinach in every available square inch of his property, inspires his nephews into planting a victory garden, by telling them a bit of the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, enticing them with tell of the giant living in the clouds. They get busy, and Popeye takes a time out to doze beneath a tree. The scene moves into his dream cloud, where he imagines his nephews awakening him, to display a beanstalk of the fabled proportions sprouted up from their garden. The nephews tell Popeye to climb it, insisting “We want a giant.” Popeye insists there ain’t no giants – and just to prove it, agrees to climb the beanstalk and not bring a giant back. In fact, he uses a more modern means of transportation, producing from nowhere a motor scooter, and riding the maze of beanstalk vines like a cloverleaf freeway maze up to the top. He emerges from a manhole cover in one of the clouds, and sees upon the next-closest cloudbank a huge castle, with sign outside advertising a bed available for the swing shift. Suddenly, an unusual vehicle pulls up alongside the edge of Popeye’s cloud – a taxi, entirely made of puffy white cloud. “Hey! Taxi to the giant’s house?”, calls the voice of an unseen driver. Popeye climbs in – actually, through the wall of the white cloudy form, and is transported in a whisk to the edge of the giant’s cloud. Stepping out, Popeye asks the driver “Fare?” Misinterpreting the word as “Fair”, the driver responds. “Nope. Cloudy and rain”, as the entire taxi dissolves in a scattering of raindrops upon the world below.

Ration Fer the Duration (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 5/28/43 – Seymour Kneitel, dir.) receives honorable mention for a brief but memorable throwaway gag involving weather. Popeye, just planting his own garden of spinach in every available square inch of his property, inspires his nephews into planting a victory garden, by telling them a bit of the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, enticing them with tell of the giant living in the clouds. They get busy, and Popeye takes a time out to doze beneath a tree. The scene moves into his dream cloud, where he imagines his nephews awakening him, to display a beanstalk of the fabled proportions sprouted up from their garden. The nephews tell Popeye to climb it, insisting “We want a giant.” Popeye insists there ain’t no giants – and just to prove it, agrees to climb the beanstalk and not bring a giant back. In fact, he uses a more modern means of transportation, producing from nowhere a motor scooter, and riding the maze of beanstalk vines like a cloverleaf freeway maze up to the top. He emerges from a manhole cover in one of the clouds, and sees upon the next-closest cloudbank a huge castle, with sign outside advertising a bed available for the swing shift. Suddenly, an unusual vehicle pulls up alongside the edge of Popeye’s cloud – a taxi, entirely made of puffy white cloud. “Hey! Taxi to the giant’s house?”, calls the voice of an unseen driver. Popeye climbs in – actually, through the wall of the white cloudy form, and is transported in a whisk to the edge of the giant’s cloud. Stepping out, Popeye asks the driver “Fare?” Misinterpreting the word as “Fair”, the driver responds. “Nope. Cloudy and rain”, as the entire taxi dissolves in a scattering of raindrops upon the world below.

Popeye knocks on the giant’s door, which opens to reveal the told-of giant, so tall he doesn’t even see Popeye. The massive man carries a large club over his shoulder, in the same manner that a baseball player might carry a bat, and on his chest is written the words “N.Y. Giants”. After a pause to let the joke settle in, the giant looks down at his own shirt, and in self-effacing tones mirroring similar casual reads in Tex Avery cartoons, remarks to the audience, “I didn’t think it was funny, either”, and wipes the lettering from his chest. Just as Popeye is too small for the giant to see, the giant is at first too high above Popeye for the sailor to notice, and Popeye does not become aware of the giant’s presence until he finds himself transported by sitting upon one of the giant’s sandals, just in front of the huge toes. When Popeye finally looks up, he retreats to a cuckoo clock, from which he observes the giant counting his “treasures” – not the usual gold eggs and harp, but all manner of rationed priority goods, of which he is a hoarder (including first-class rubber tires laid by his magic hen instead of eggs). “Uncle Sam could use all that stuff” says Popeye. He engages in a game of cat and mouse with the giant, attempting to make off with a stack of tires, and is almost swallowed in a sandwich, just as he reaches for his spinach can. The giant’s mouth opens, revealing Popeye using the uvula of the giant’s throat as a punching bag (a gag Friz Freleng would remember for the later “I Taw a Putty Tat”). Getting the giant to sneeze with a nose full of pepper, Popeye rides a carpet bag full of the rationed goods out the door on the force of the sneeze, and falls over and over down toward earth. But his spinning is back in the real world, where the nephews are attempting to awaken him, to show off their real victory garden. Instead of beans, they have planted mutant plants that are their own solution to the rationing problem – each producing a rationed item right off the vine. POT-tatoes, CAN-taloupes, and Pine-NIPPLES are among the crops, together with “Squashes” (used tires), “Peaches” (brand new tires), and last of all, a “SHOE tree”, growing rubber-soled shoes by the dozens. Popeye laughs with pleasure at their patriotic breakthrough, as the film irises out.

Popeye knocks on the giant’s door, which opens to reveal the told-of giant, so tall he doesn’t even see Popeye. The massive man carries a large club over his shoulder, in the same manner that a baseball player might carry a bat, and on his chest is written the words “N.Y. Giants”. After a pause to let the joke settle in, the giant looks down at his own shirt, and in self-effacing tones mirroring similar casual reads in Tex Avery cartoons, remarks to the audience, “I didn’t think it was funny, either”, and wipes the lettering from his chest. Just as Popeye is too small for the giant to see, the giant is at first too high above Popeye for the sailor to notice, and Popeye does not become aware of the giant’s presence until he finds himself transported by sitting upon one of the giant’s sandals, just in front of the huge toes. When Popeye finally looks up, he retreats to a cuckoo clock, from which he observes the giant counting his “treasures” – not the usual gold eggs and harp, but all manner of rationed priority goods, of which he is a hoarder (including first-class rubber tires laid by his magic hen instead of eggs). “Uncle Sam could use all that stuff” says Popeye. He engages in a game of cat and mouse with the giant, attempting to make off with a stack of tires, and is almost swallowed in a sandwich, just as he reaches for his spinach can. The giant’s mouth opens, revealing Popeye using the uvula of the giant’s throat as a punching bag (a gag Friz Freleng would remember for the later “I Taw a Putty Tat”). Getting the giant to sneeze with a nose full of pepper, Popeye rides a carpet bag full of the rationed goods out the door on the force of the sneeze, and falls over and over down toward earth. But his spinning is back in the real world, where the nephews are attempting to awaken him, to show off their real victory garden. Instead of beans, they have planted mutant plants that are their own solution to the rationing problem – each producing a rationed item right off the vine. POT-tatoes, CAN-taloupes, and Pine-NIPPLES are among the crops, together with “Squashes” (used tires), “Peaches” (brand new tires), and last of all, a “SHOE tree”, growing rubber-soled shoes by the dozens. Popeye laughs with pleasure at their patriotic breakthrough, as the film irises out.

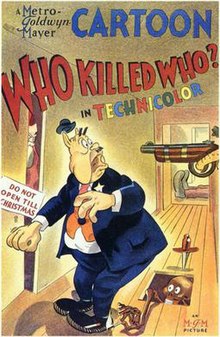

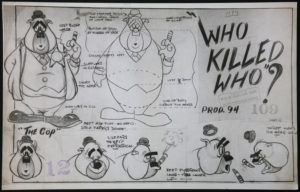

Who Killed Who? (MGM, 6/5/43 – Tex Avery, dir.) – An Avery masterpiece, which, in its alleged purpose to uphold the principles of law and order, breaks the legal limit for number of gags crammed into a one-reel cartoon. Opening in unusual fashion, the film begins in live-action, at the desk of an official-looking commentator, who announces that through the medium of the animated cartoon, a murder mystery condensed from authentic criminal records will be presented – the purpose, to demonstrate that “Crime Does Not Pay”. (This quote is undoubtedly intended to convince the audience that this is part of a series of live-action short mini-dramas depicting various vices and rackets which MGM produced under the same banner, “Crime Does Not Pay”, between 1935 and 1947.) The commentator is revealed by IMDB to be character-actor Robert Emmett O’Connor, whose primary career had been around the dawn of sound, usually playing types like police officers and detectives. Generally without screen credit, he had moved to a contract with MGM to play minor supporting roles, still often as a cop, including in such pictures as “A Night at the Opera”, “Best Foor Forward”, and “Whistling in Brooklyn”. Being somewhat unfamiliar with the run of the “Crime” shorts, I am uncertain if he also appeared in the actual shorts lampooned by this cartoon – but it would seem likely.

Who Killed Who? (MGM, 6/5/43 – Tex Avery, dir.) – An Avery masterpiece, which, in its alleged purpose to uphold the principles of law and order, breaks the legal limit for number of gags crammed into a one-reel cartoon. Opening in unusual fashion, the film begins in live-action, at the desk of an official-looking commentator, who announces that through the medium of the animated cartoon, a murder mystery condensed from authentic criminal records will be presented – the purpose, to demonstrate that “Crime Does Not Pay”. (This quote is undoubtedly intended to convince the audience that this is part of a series of live-action short mini-dramas depicting various vices and rackets which MGM produced under the same banner, “Crime Does Not Pay”, between 1935 and 1947.) The commentator is revealed by IMDB to be character-actor Robert Emmett O’Connor, whose primary career had been around the dawn of sound, usually playing types like police officers and detectives. Generally without screen credit, he had moved to a contract with MGM to play minor supporting roles, still often as a cop, including in such pictures as “A Night at the Opera”, “Best Foor Forward”, and “Whistling in Brooklyn”. Being somewhat unfamiliar with the run of the “Crime” shorts, I am uncertain if he also appeared in the actual shorts lampooned by this cartoon – but it would seem likely.

As the animation begins, a clever use of “a dark and stormy night” is made, not only for atmosphere, but to perform a camera feat that was impossible to accomplish with the limited focal range of a standard, non-multiplane animation camera. Beginning from a view from the base of a hill up a winding road, the camera closes in, ever so slowly, upon the creepy abode of Gruesome Gables, with all manners of shrieks, groans, and sinister laughs heard from the surrounding countryside, punctuated by the crash of repeated strikes of lightning from the darkened skies. Our eyes are so dazzled by the brilliance of the flashes of lightning, we fail to notice except upon close inspection that the cameraman is making substitutions of backgrounds following each flash, to a view depicting a closer angle on the scene before us, like a shot within a shot. In this manner, the camera operator is able to utilize the zoom features of the camera to close in upon each background to its optimum distance, then substitute the next background of a closer view while moving the camera’s zoom back to its most distant point, then closing in again with the zoom until the next background is substituted. The camera thus travels in what appears to be one continuous shot all the way from the lonely country road to a view which enters one of the small windows of the mansion before us – an accomplishment that would even baffle the best of live-action cinematographers. (Max Fleischer had tried for a similar trick of background-substitution zooming in the early Betty Boop short, “The Bum Bandit”, to depict a POV view of traveling down a train track for a few hundred yards until stopped by the bandit Bimbo standing with guns drawn on the rails – all without animating a single frame in 3-D perspective. The effect was interesting, but considerably more awkward in execution, due to lack of lightning to dazzle the eyes during background substitutions, and less-experienced camera work, which allowed the camera to zoom in too closely on some backgrounds, resulting in flashes of differing light exposure between one background and another.) Tex’s effect worked so well, the animation was repeated several years later as the opening to his short, “The Cuckoo Clock” (which, since it is a duplication, will be skipped over in subsequent articles in this series).

As the animation begins, a clever use of “a dark and stormy night” is made, not only for atmosphere, but to perform a camera feat that was impossible to accomplish with the limited focal range of a standard, non-multiplane animation camera. Beginning from a view from the base of a hill up a winding road, the camera closes in, ever so slowly, upon the creepy abode of Gruesome Gables, with all manners of shrieks, groans, and sinister laughs heard from the surrounding countryside, punctuated by the crash of repeated strikes of lightning from the darkened skies. Our eyes are so dazzled by the brilliance of the flashes of lightning, we fail to notice except upon close inspection that the cameraman is making substitutions of backgrounds following each flash, to a view depicting a closer angle on the scene before us, like a shot within a shot. In this manner, the camera operator is able to utilize the zoom features of the camera to close in upon each background to its optimum distance, then substitute the next background of a closer view while moving the camera’s zoom back to its most distant point, then closing in again with the zoom until the next background is substituted. The camera thus travels in what appears to be one continuous shot all the way from the lonely country road to a view which enters one of the small windows of the mansion before us – an accomplishment that would even baffle the best of live-action cinematographers. (Max Fleischer had tried for a similar trick of background-substitution zooming in the early Betty Boop short, “The Bum Bandit”, to depict a POV view of traveling down a train track for a few hundred yards until stopped by the bandit Bimbo standing with guns drawn on the rails – all without animating a single frame in 3-D perspective. The effect was interesting, but considerably more awkward in execution, due to lack of lightning to dazzle the eyes during background substitutions, and less-experienced camera work, which allowed the camera to zoom in too closely on some backgrounds, resulting in flashes of differing light exposure between one background and another.) Tex’s effect worked so well, the animation was repeated several years later as the opening to his short, “The Cuckoo Clock” (which, since it is a duplication, will be skipped over in subsequent articles in this series).

The remainder of the film, taking place in the interior of the mansion, is legendary for its zaniness, and would almost take a volume to fully describe in words. A signature Avery sign gag follows a tracking shot through the absolute silence inside the mansion, where a picture frame hanging on the wall reveals a sign reading, “Spooky, isn’t it?” A solitary old dog sits in the study, in an easy chair on the back of which flash the neon letters “The Victim”. He is reading the volume, “Who Killed Who?” (From the cartoon of the same name).” A dagger flies through the air into the wall in front of him, carrying a note reading “You will die at 11:30.” When the dog complains that he can’t die at 11:30, a second dagger and note announces, “OK. We’ll make it 12:00.” A cuckoo clock from the “Boooo-lova Watch Time” company (play on “Bulova Watch”, an oft-heard radio sponsor) announces 12 midnight “when you hear the sound of the gun”. Clock chimes play the funeral march, while gun shots ring out with the tones of the three chimes which have remained a signature for NBC. As the victim falls, a sheet magically pulls itself over his form, to indicate he is deceased – yet, when a detective arrives to photograph the body, he is alive enough to strike a photogenic pose. The detective (who is a caricature of another known character actor, Fred Kelsey – perhaps best remembered today as the detective in “The Laurel-Hardy Murder Case”) warns “Don’t nobody move!” – then conks a shadow of a theater patron shifting seats in the front row to follow his warning. Pressing a buzzer on a desk reading “Ring Bell For Suspects” the detective is greeted by a chauffeur, maid, and butler who instantly pop up on the other side of the desk. When he demands to know “Who done it?”, the suspects reply, “Aw, wouldn’t you like to know?” The detective states he’ll turn out the lights, and when he turns them on, wants to see the murder weapon resting on the desk. Instead, when the lights go on, the view is of an arsenal stacked to the ceiling. Demanding they cut out the clowning and try it again, the detective again switches off the light – and switches it back on to find the room entirely empty, stripped to the bare walls of all contents and furniture.

The remainder of the film, taking place in the interior of the mansion, is legendary for its zaniness, and would almost take a volume to fully describe in words. A signature Avery sign gag follows a tracking shot through the absolute silence inside the mansion, where a picture frame hanging on the wall reveals a sign reading, “Spooky, isn’t it?” A solitary old dog sits in the study, in an easy chair on the back of which flash the neon letters “The Victim”. He is reading the volume, “Who Killed Who?” (From the cartoon of the same name).” A dagger flies through the air into the wall in front of him, carrying a note reading “You will die at 11:30.” When the dog complains that he can’t die at 11:30, a second dagger and note announces, “OK. We’ll make it 12:00.” A cuckoo clock from the “Boooo-lova Watch Time” company (play on “Bulova Watch”, an oft-heard radio sponsor) announces 12 midnight “when you hear the sound of the gun”. Clock chimes play the funeral march, while gun shots ring out with the tones of the three chimes which have remained a signature for NBC. As the victim falls, a sheet magically pulls itself over his form, to indicate he is deceased – yet, when a detective arrives to photograph the body, he is alive enough to strike a photogenic pose. The detective (who is a caricature of another known character actor, Fred Kelsey – perhaps best remembered today as the detective in “The Laurel-Hardy Murder Case”) warns “Don’t nobody move!” – then conks a shadow of a theater patron shifting seats in the front row to follow his warning. Pressing a buzzer on a desk reading “Ring Bell For Suspects” the detective is greeted by a chauffeur, maid, and butler who instantly pop up on the other side of the desk. When he demands to know “Who done it?”, the suspects reply, “Aw, wouldn’t you like to know?” The detective states he’ll turn out the lights, and when he turns them on, wants to see the murder weapon resting on the desk. Instead, when the lights go on, the view is of an arsenal stacked to the ceiling. Demanding they cut out the clowning and try it again, the detective again switches off the light – and switches it back on to find the room entirely empty, stripped to the bare walls of all contents and furniture.

More madness ensues as the detective investigates through the mansion. Eyes peer through the sliding panel in a wooden door. Then, the panel closes, temporary trapping just the eyeballs on the outside looking in. The detective shines a flashlight into a room containing an art gallery, where one painting depicts a shapely, scantily-clothed beauty standing in a pose revealing herself from within a large fur coat. When the detective flashes the light back for a second look, the girl has covered herself in the fur. A door is opened, and a bound body falls out – then another, then another, then another, then another, in an endless repeating cycle – but one falling body pauses, speaking in the voice of Jerry Colonna – “Ah, yes! Quite a bunch of us, isn’t it?” A skeleton appears, followed by another one of unusual color shade, who announces himself as “Red Skeleton” (play on popular radio and MGM movie comedian Red Skelton). Santa Claus (voiced by Avery himself) appears behind a door reading “Do not open until Xmas.” A picture frame is turned over by the detective, revealing an inscription on the wall – “Well, what did you expect to find back here?” A trap door is found, and the detective drops a vase into the hole to see how deep it is – only to have the same vase somehow fall from the ceiling upon his own head. A hooded figure finally confronts the detective, getting the drop on him with a gun in his back, and commanding “Reach for the ceiling.” The detective follows orders, extending his arms to reach all the way to a high ceiling towering about four stories above him. But the hooded figure’s gun is empty (as indicated on a gasoline gauge installed in the pistol’s handle). The detective pursues the hooded man throughout the mansion, then gets the specter to pause before a curtain to oogle a pair of shapely feminine legs visible from behind it – which turn out ro belong to the detective. Bopping the hooded man with a mallet, the detective leaps forward to raise the hood to reveal “who done it.” Quickly shifting to a live-action close-ip, the reveal is of none other than out host O’Connor, who cries out, “I done it”, and ends the film weeping hysterically.

More madness ensues as the detective investigates through the mansion. Eyes peer through the sliding panel in a wooden door. Then, the panel closes, temporary trapping just the eyeballs on the outside looking in. The detective shines a flashlight into a room containing an art gallery, where one painting depicts a shapely, scantily-clothed beauty standing in a pose revealing herself from within a large fur coat. When the detective flashes the light back for a second look, the girl has covered herself in the fur. A door is opened, and a bound body falls out – then another, then another, then another, then another, in an endless repeating cycle – but one falling body pauses, speaking in the voice of Jerry Colonna – “Ah, yes! Quite a bunch of us, isn’t it?” A skeleton appears, followed by another one of unusual color shade, who announces himself as “Red Skeleton” (play on popular radio and MGM movie comedian Red Skelton). Santa Claus (voiced by Avery himself) appears behind a door reading “Do not open until Xmas.” A picture frame is turned over by the detective, revealing an inscription on the wall – “Well, what did you expect to find back here?” A trap door is found, and the detective drops a vase into the hole to see how deep it is – only to have the same vase somehow fall from the ceiling upon his own head. A hooded figure finally confronts the detective, getting the drop on him with a gun in his back, and commanding “Reach for the ceiling.” The detective follows orders, extending his arms to reach all the way to a high ceiling towering about four stories above him. But the hooded figure’s gun is empty (as indicated on a gasoline gauge installed in the pistol’s handle). The detective pursues the hooded man throughout the mansion, then gets the specter to pause before a curtain to oogle a pair of shapely feminine legs visible from behind it – which turn out ro belong to the detective. Bopping the hooded man with a mallet, the detective leaps forward to raise the hood to reveal “who done it.” Quickly shifting to a live-action close-ip, the reveal is of none other than out host O’Connor, who cries out, “I done it”, and ends the film weeping hysterically.

The Home Front (Warner, Private Snafu, 10/15/43 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) – We find Snafu at a remote post somewhere in nowhere, on a night when blizzard winds wail, and the temperature is “so cold it would freeze the nuts off a jeep.” Snafu is huddled inside a Quonset hut, seated atop a pot-bellied stove while wearing full winter parka, just to endure the temperature extreme, while he stares at a wall of his pin-up photo collection and listens to a phonograph (with icicles hanging from its tone arm) playing a record of “Home Sweet Home”. Frustrated, he smashes the record player, and grumbles about the folks at home, who “got it soft back there. They don’t even know there’s a war goin’ on.” He envisions his pop at his usual favorite haunt – the pool room, his mom endlessly jabbering at a daily bridge game, his grandpaw at a burlesque theater watching scantily-clothed women, and his girlfriend out of a date with a smooth-talking cad (who compliments her on her eyes, while oogling another part of her anatomy that comes in pairs). Technical Fairy First Class shows up (interrupting his introduction to note that it’s colder than a brass monkey), and gives Snafu a chance to really see what his folks are up to on a TV monitor. Instead of the pool room, pop is laboring with perspiring effort building tanks out of scrap iron at a defense plant. Mom has foregone the bridge game in favor of planting every square inch of their land as a victory garden, the family horse providing an ample supply of manure that makes crops grow instantly. Grandpaw sits in a rocking chair, but suspended from a cable in a shipyard, where he is on the riveting crew launching battleship after battleship, calling when all have left the drydock, “Set ‘em up in the next alley!” And instead of dating, Snafu’s girl has joined the WACs. They all salute Snafu on the screen, with a tuneful chorus of “We’re working like hell on the old home ground.” Snafu’s girl leans forward in the screen to offer Snafu a virtual kiss. Snafu kisses the screen, but the image dissolves to the Technical Fairy, who responds, “I didn’t know you cared. Woo Woo.”

The Home Front (Warner, Private Snafu, 10/15/43 – Frank Tashlin, dir.) – We find Snafu at a remote post somewhere in nowhere, on a night when blizzard winds wail, and the temperature is “so cold it would freeze the nuts off a jeep.” Snafu is huddled inside a Quonset hut, seated atop a pot-bellied stove while wearing full winter parka, just to endure the temperature extreme, while he stares at a wall of his pin-up photo collection and listens to a phonograph (with icicles hanging from its tone arm) playing a record of “Home Sweet Home”. Frustrated, he smashes the record player, and grumbles about the folks at home, who “got it soft back there. They don’t even know there’s a war goin’ on.” He envisions his pop at his usual favorite haunt – the pool room, his mom endlessly jabbering at a daily bridge game, his grandpaw at a burlesque theater watching scantily-clothed women, and his girlfriend out of a date with a smooth-talking cad (who compliments her on her eyes, while oogling another part of her anatomy that comes in pairs). Technical Fairy First Class shows up (interrupting his introduction to note that it’s colder than a brass monkey), and gives Snafu a chance to really see what his folks are up to on a TV monitor. Instead of the pool room, pop is laboring with perspiring effort building tanks out of scrap iron at a defense plant. Mom has foregone the bridge game in favor of planting every square inch of their land as a victory garden, the family horse providing an ample supply of manure that makes crops grow instantly. Grandpaw sits in a rocking chair, but suspended from a cable in a shipyard, where he is on the riveting crew launching battleship after battleship, calling when all have left the drydock, “Set ‘em up in the next alley!” And instead of dating, Snafu’s girl has joined the WACs. They all salute Snafu on the screen, with a tuneful chorus of “We’re working like hell on the old home ground.” Snafu’s girl leans forward in the screen to offer Snafu a virtual kiss. Snafu kisses the screen, but the image dissolves to the Technical Fairy, who responds, “I didn’t know you cared. Woo Woo.”

The Wreck of the Hesperus (Terrytoons/Fox, Mighty Mouse, 2/12/44 – Mannie Davis, dir.) – Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poetry provides an adventure setting for Mighty Mouse. The super rodent was now going under his ultimate name, but still in transition as to his wardrobe, still wearing the blue tights and the red pants and cape of Superman. Current color prints of the film are edited, though I recall the uncut version circulating in 16mm prints for years on local Los Angeles television back in the 70’s, The main trouble was a series of close-ups on the Captain’s fair daughter, accompanied by lines from the poem, “Blue were her eyes like the fairy flax, her cheeks like the dawn of day, and her bosom white as the hawthorne buds that open the month of May.” The latter phrase had the girl modestly covering her front, but still depicted in a provocative way, which seemed a little odd for me even as a younger viewer. Another brief cut or two are made purely to save time in the current CBS print, shortening up a shark fight to remove the narration line “What a storm. WHAT A MOUSE!”, and also briefly clipping Mighty’s transporting of the ship to New York City, allowing for a cut in the music track to move up the music originally heard over the end title, permitting the orchestration to conclude at the fade out of the animated scenes instead. The unedited version of the film can be seen on Youtube from a black and white 16mm issued back in the home movie days by Castle Films, also including the complete opening and closing music cues.

The Wreck of the Hesperus (Terrytoons/Fox, Mighty Mouse, 2/12/44 – Mannie Davis, dir.) – Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poetry provides an adventure setting for Mighty Mouse. The super rodent was now going under his ultimate name, but still in transition as to his wardrobe, still wearing the blue tights and the red pants and cape of Superman. Current color prints of the film are edited, though I recall the uncut version circulating in 16mm prints for years on local Los Angeles television back in the 70’s, The main trouble was a series of close-ups on the Captain’s fair daughter, accompanied by lines from the poem, “Blue were her eyes like the fairy flax, her cheeks like the dawn of day, and her bosom white as the hawthorne buds that open the month of May.” The latter phrase had the girl modestly covering her front, but still depicted in a provocative way, which seemed a little odd for me even as a younger viewer. Another brief cut or two are made purely to save time in the current CBS print, shortening up a shark fight to remove the narration line “What a storm. WHAT A MOUSE!”, and also briefly clipping Mighty’s transporting of the ship to New York City, allowing for a cut in the music track to move up the music originally heard over the end title, permitting the orchestration to conclude at the fade out of the animated scenes instead. The unedited version of the film can be seen on Youtube from a black and white 16mm issued back in the home movie days by Castle Films, also including the complete opening and closing music cues.

Following the text of the original poem closely, the film follows the schooner Hesperus. putting out to sea on an icy winter day. The skipper is a traditional old salt type (human, not mouse), wearing weatherproof slicker and puffing a corn-cob pipe. His daughter, well bundled in fur coat and abundant petticoats, is along for the journey. A single crewman accompanies them on lookout in the crow’s nest, but makes a quick trip down the mast by means of his nest descending like an elevator, then scoots along upon a wheel mounted in his wooden leg to warn the Captain of sightings in the heavens that tell the mariner that a hurricane is imminent. The skipper scoffs with laughter, and fails to heed warning to put into port. Suddenly, several clouds amass together, forming into the shape of a white-haired and moustached cloud-god, who peers down at the ocean, and begins blowing from his mouth with gale force. The ship endures a choppy ride, rising on the crest of waves four times its height, hesitating at the top, then riding down the backside of the wave like a roller coaster, into the upward curl of the next wave following. For safety sake, the skipper grabs his daughter and a length of fallen rope, and lashes her to the mast so that she will not be swept overboard. The skipper steers the vessel on a jagged course between even more jagged icebergs. The ship’s figurehead takes a bracing beating from the waves in her path, and comes to life to reach into the ship’s porthole for a fur overcoat. Lightning stabs down, knocking loose the ship’s wheel from its mounting. The skipper tries to pursue the rotating wheel across the deck, but is swept back by a wave across the bow, which propels him up the mizzen mast like the lead weight of a carnival high-striker, his head colliding with the ship’s bell.

Following the text of the original poem closely, the film follows the schooner Hesperus. putting out to sea on an icy winter day. The skipper is a traditional old salt type (human, not mouse), wearing weatherproof slicker and puffing a corn-cob pipe. His daughter, well bundled in fur coat and abundant petticoats, is along for the journey. A single crewman accompanies them on lookout in the crow’s nest, but makes a quick trip down the mast by means of his nest descending like an elevator, then scoots along upon a wheel mounted in his wooden leg to warn the Captain of sightings in the heavens that tell the mariner that a hurricane is imminent. The skipper scoffs with laughter, and fails to heed warning to put into port. Suddenly, several clouds amass together, forming into the shape of a white-haired and moustached cloud-god, who peers down at the ocean, and begins blowing from his mouth with gale force. The ship endures a choppy ride, rising on the crest of waves four times its height, hesitating at the top, then riding down the backside of the wave like a roller coaster, into the upward curl of the next wave following. For safety sake, the skipper grabs his daughter and a length of fallen rope, and lashes her to the mast so that she will not be swept overboard. The skipper steers the vessel on a jagged course between even more jagged icebergs. The ship’s figurehead takes a bracing beating from the waves in her path, and comes to life to reach into the ship’s porthole for a fur overcoat. Lightning stabs down, knocking loose the ship’s wheel from its mounting. The skipper tries to pursue the rotating wheel across the deck, but is swept back by a wave across the bow, which propels him up the mizzen mast like the lead weight of a carnival high-striker, his head colliding with the ship’s bell.

In the sea below, an octopus laughs at the plight of the ship above, and sensing the ship’s doom is imminent, sets a dinner table with plates and cutlery, as a fit dining location for a school of sharks which also gathers in wait. The sharks swim to the surface to obtain their main course, following closely behind the ship, which now proceeds aimlessly with tattered sail. In an old, overused gag, mice desert the sinking ship, using doughnuts from the galley as life preservers. On the deck above, the skipper now finds himself swimming amidst water waist deep swamping the deck, with a circle of the sharks already on board pursuing him. Proceeding with the reading of the poem, all action briefly ceases, so that the skipper may pause to answer a meaningless question from his daughter – then the chase and the storm resume their action.

In the sea below, an octopus laughs at the plight of the ship above, and sensing the ship’s doom is imminent, sets a dinner table with plates and cutlery, as a fit dining location for a school of sharks which also gathers in wait. The sharks swim to the surface to obtain their main course, following closely behind the ship, which now proceeds aimlessly with tattered sail. In an old, overused gag, mice desert the sinking ship, using doughnuts from the galley as life preservers. On the deck above, the skipper now finds himself swimming amidst water waist deep swamping the deck, with a circle of the sharks already on board pursuing him. Proceeding with the reading of the poem, all action briefly ceases, so that the skipper may pause to answer a meaningless question from his daughter – then the chase and the storm resume their action.

The floating mice are washed ashore at the base of a large lighthouse. A mouse keeper of the light emerges from a hole in the structure’s side, carrying a lantern, whose light rays behave oddly from the force of the storm’s driving winds, not emerging straight out from the lamp’s sides, but bent backwards around the mouse in curves! He sees the exhausted mice resting on the rocks, and deduces that something is wrong at sea. Re-entering the lighthouse, a light visible through the structure’s side denotes his ascent to the top via an internal elevator. He activates the massive light at the top, whose beam faces a similar problem to the lantern with the wind, the force of the blow momentarily bending the light beam back upon itself, before it finally straightens out, and reveals a view to the keeper that spells danger. The ship has grounded on a reef, and the captain and his daughter cling to the mast, with the sharks jumping up to nip at their heels like dogs attempting to reach a prey they’ve treed. Finally deviating from the text of the poem, the narrator shouts, “This looks like a job for Mighty Mouse!” (A side note of interest: The Castle Films silent edition of this film, which showed dialogue lines by means of intertitles in the manner of a silent movie, performs a rare feat with this line, animating the lettering mechanically, so that all words but the name “Mighty Mouse” remain at normal size at the top of the screen, but the letters of the name perform a vertical stretch, growing from about one-sixth of the screen’s height to fill three-quarters of the screen! Impressive.)

Without the continued need to ingest any food from the Super Market, the lighthouse mouse goes into a spin, emerging from the whirlwind in costume and ready for action. (This feat is a little unusual in this episode, as the animators have forgetfully animated the lighthouse mouse with brown fur – yet, after the transformation, Mighty appears in his traditional fur coat of black!) He zooms off toward the wreck, performing a flight pattern he would often repeat in later episodes, cutting straight through the tops of the sea’s choppy waves. He arrives just in time to sock one of the sharks in the jaw before it can chomp off the daughter’s toes, then engages in battle with the entire school of sharks. Using his red flight contrail as if a fishing line, Mighty flies through the mouth of each shark, snagging them with the contrail as if caught on a hook, then zooms up into the sky, carrying the struggling sharks upwards in a single-file upon the line. Mighty then performs a circular swoop that “cracks the whip” of the line much like a line of skaters on an ice pond, scattering the sharks to the winds. He then soars down to the ship, tying his contrail in a knot around the capstan on the ship’s forward deck, and reverses course to haul the contrail upwards again. The ship is lifted from the rocks, and flies into the heavens, following Mighty. The skipper, his daughter, and the old mariner (where did he disappear to throughout all this action?) cheer Mighty from the bow, and even the ship’s figurehead celebrates the moment, by holding aloft in one hand an American flag. Mighty tows the ship into the harbor of New York City, where all are greeted by a ticker tape parade. They ride down Broadway in an open limousine (everyone including the figurehead), with Mighty highest atop the rear seat, a parade of cheering mice following behind him, for the fade out.

Without the continued need to ingest any food from the Super Market, the lighthouse mouse goes into a spin, emerging from the whirlwind in costume and ready for action. (This feat is a little unusual in this episode, as the animators have forgetfully animated the lighthouse mouse with brown fur – yet, after the transformation, Mighty appears in his traditional fur coat of black!) He zooms off toward the wreck, performing a flight pattern he would often repeat in later episodes, cutting straight through the tops of the sea’s choppy waves. He arrives just in time to sock one of the sharks in the jaw before it can chomp off the daughter’s toes, then engages in battle with the entire school of sharks. Using his red flight contrail as if a fishing line, Mighty flies through the mouth of each shark, snagging them with the contrail as if caught on a hook, then zooms up into the sky, carrying the struggling sharks upwards in a single-file upon the line. Mighty then performs a circular swoop that “cracks the whip” of the line much like a line of skaters on an ice pond, scattering the sharks to the winds. He then soars down to the ship, tying his contrail in a knot around the capstan on the ship’s forward deck, and reverses course to haul the contrail upwards again. The ship is lifted from the rocks, and flies into the heavens, following Mighty. The skipper, his daughter, and the old mariner (where did he disappear to throughout all this action?) cheer Mighty from the bow, and even the ship’s figurehead celebrates the moment, by holding aloft in one hand an American flag. Mighty tows the ship into the harbor of New York City, where all are greeted by a ticker tape parade. They ride down Broadway in an open limousine (everyone including the figurehead), with Mighty highest atop the rear seat, a parade of cheering mice following behind him, for the fade out.

‘44 brings more and more, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

I was amused by the French language dub of “Fall Out, Fall In”. Oh well, as they used to say during the war, fifty million French ducks can’t be wrong.

Thanks for the tip about the uncut black-and-white version of “The Wreck of the Hesperus” on YouTube. I hope an uncut print of “Swiss Cheese Family Robinson” surfaces someday; considering what was left in the TV prints, I can’t imagine what must have been removed.

Speaking of Mighty Mouse, “Pandora’s Box” (1943), covered in an earlier column, is relevant here. Pandora opens her box and unleashes evil upon the world in the form of three bat-winged black cats, who fly up into the clouds to create a thunderstorm, making rain with hand pumps and lightning by throwing a switch. The lightning strikes an old mill in which the mice have sought shelter from the rain, setting it afire, and it’s up to Mighty Mouse to save the day.

Though an uncut print of “Swiss Cheese Family Robinson” hasn’t surfaced on Youtube, I have had access to one courtesy of Jerry Beck, and summarized the missing scenes in my previous post, “Toons Trip Out (Part 7)”. You may wish to review such post for the detail you seek. Surprisingly, the cut scenes weren’t all that offensive as opposed to the ones left on the air, though the best gag pushed the envelope a bit – where a native with a nose ring uses it for the added purpose of hanging his car keys on it. I am also pretty sure that an uncut print turned up on Super 8 from a European source. I recently acquired a copy on ebay, bit have not yet screened it to determine completeness of content – though it is definitely of running length much longer than the conventional CBS print.

Paul

The edited scene from Swiss Cheese Family Robinson has an existence on YouTube, from a Spanish-dubbed TV print

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ZgYTlvXClk&t=112s

Muchas gracias, amigo!

Re: “Dizzy Newsreel” — (from ‘Doing Their Bit: Wartime American Animated Short Cartoons’)

The final sequence is datelined: “Wattarat, Japan: Captured Pictures Show Launching of New Giant Vulture,” apparently referring to a failed Japanese wartime invention.

I don’t remember where we found this information, possibly Office of War Information files or a contemporary review. I am pretty sure we did not see an uncut print (it’s been more than 30 years, I just don’t recall).

The old dog at the start of WHO KILLED WHO is Richard Haydn (imitated,at least).

VERY good cartoon,btw.

Steve J.Carras

The “buzzard” on Pedro is actually a condor. Incidentally, Chile wasn’t too impressed with this segment of Saludos Amigos, so one cartoonist decided to rectify that by creating a purely Chilean cartoon character based on the national bird. The result was Condorito, still one of the most popular characters to come out of Latin America.

“Aladdin’s Lamp” (Terrytoons, Gandy Goose and Sourpuss, 22/10/43 — Eddie Donnelly, dir.), the third of four Terrytoons with that title, begins on a dark and stormy night at an army air base. Gandy is reading a book titled “Tales of China”, but Sourpuss, annoyed by a leaking roof, tells him to get to sleep. In a dream sequence, Gandy and Sourpuss are in the open cockpit of a fighter plane as it flies through the terrible storm. Gandy opens an umbrella, but a bolt of lightning reduces it to a burnt matchstick. The cockpit fills with rainwater, and Gandy tries to bail it out with his helmet, but the wind keeps blowing the water into Sourpuss’s face. Then the engine sputters and dies, forcing them to abandon the plane; but as soon as they make the leap with their parachutes, the plane veers around to reclaim them. Now too low to parachute safely, they make an emergency landing in a lake, where they are rescued by the fishing boat of Aladdin, shown here as a white Pekin duck with a cymbal-shaped hat. For the rest of the cartoon, Aladdin uses his magic lamp to entertain his guests with the delights of the Orient. By this time, of course, the weather has taken a decided turn for the better.

“The Fly in the Ointment” (Columbia Phantasies, 23/7/43 — Paul Sommer, dir.) pokes fun at a cliche we have seen time and again in this series. It begins with an establishing shot of a spooky castle in a thunderstorm. Up in the belfry, a couple of bats comment: “Oh dear, do all spook pictures have to start this way?” “I’m afraid so!” “Oh, no no no no no no!”