Tex Avery’s Southern wolf, in Three Little Pups, was once heard to comment disdainfully, “Heh. Television!” Little would Daws Butler, in providing the voice, realize how much future work the new medium would bring to him, upon his move to the thriving atmosphere of the new Hanna-Barbera studios. We thus move our survey of fire-related cartoons to the proverbial “small screen”, this week, in rather random order (as is my wont when researching the myriad of programs available in the golden days of kiddie TV), focusing on some of the earliest of such efforts to appear, and upon the continuing screen history of that veritable forest icon, Smokey the Bear, still taking time out from his busy PSA schedule in an attempt to provide “entertainment” to the best of his ability.

I confess I was not a great fan of “adventure” cartoon programming during the 60’s, 70‘s and onward, until the advent of the DC universe during the Warner Brothers’ renaissance. I thus imagine there may be a great many fire/rescue situations buried in such odds and ends series such as “Emergency +4″, “Lassie’s Rescue Rangers”, “Clutch Cargo”, more recently, “Fireman Sam”, and for all I know, maybe even “Jonny Quest”. I will not be belaboring these areas with which I profess no great familiarity, nor the many superhero shows that may also have dabbled in such scenarios. I will instead concentrate primarily on the comedic, as in the days of old previously covered by this series, for later variants on such ideas appearing in the TV era. Readers may again, if so inclined, augment these pages with their own takes on fire episodes from these other genres, as well as any more laugh-oriented episodes I may have missed. (Please remember in the latter regard that this review will not be in chronological order, so please try not to jump the gun on funny ones until the final installment.)

Fireman Huck (image courtesy of Don Yowp)

Among the earliest TV episode recalled by this author was Fireman Huck (Hanna-Barbera (H-B Enterprises), Huckleberry Hound, 12/8/58). A fireman cartoon with no flames? Well, it made sense, focusing on a fireman’s other prime occupation – rescue – in this case of a stranded pussy cat up a tree. The film is actually a remake/reworking of one of H-B’s earliest one-shots at MGM, produced between Tom and Jerry episodes, Officer Pooch (1941). The original featured a mutt officer who could be considered the prototype for Huckleberry Hound but who did not speak, attempting to rescue a kitten pestered by a spunky dog. The Huck remake merely changes his line of public service from the police force to fireman. It’s a bit odd that both films pit a humanized dog who walks on two feet against a natural dog who barks and goes about on all fours – Huck calling even more attention to it by uttering the line, “To handle dogs, you gotta be smarter than a dog.” Well, what is Huck? Maybe that’s why his efforts are doomed to failure – he can’t very well be smarter than his own species.

Huck runs a fire station in a community with very little action. He uses his fire hose for no greater purpose than to water the lawn outside the station. A call comes in on the phone, to which he responds in slow-motion, only after completing a humming chorus of “Clementine”. A cat owner (never seen) reports her cat up a tree, and Huck drives the hook and ladder engine out to the scene. There, a dog waits at the base of a tree, while a small kitten yowls, clinging to the uppermost limb of a tall oak, spruce, or whatever. The dog continues to bark, until Huck is forced to yell, “Quiet when I hollers QUIET!” Shaming the pup with reprimands of “Bad dog”, Huck order the pooch to “Get on home.” The dog whimpers and creeps away, but returns to aggressive demeanor the minute he is hidden behind the corner of his house.

Huck runs a fire station in a community with very little action. He uses his fire hose for no greater purpose than to water the lawn outside the station. A call comes in on the phone, to which he responds in slow-motion, only after completing a humming chorus of “Clementine”. A cat owner (never seen) reports her cat up a tree, and Huck drives the hook and ladder engine out to the scene. There, a dog waits at the base of a tree, while a small kitten yowls, clinging to the uppermost limb of a tall oak, spruce, or whatever. The dog continues to bark, until Huck is forced to yell, “Quiet when I hollers QUIET!” Shaming the pup with reprimands of “Bad dog”, Huck order the pooch to “Get on home.” The dog whimpers and creeps away, but returns to aggressive demeanor the minute he is hidden behind the corner of his house.

Meanwhile, Huck raises the engine ladder to the tree limb above. “Poor l’il ol’ frightened thing”, Huck says to the cat consolingly. But the cat hasn’t forgotten it’s a cat, and flails at Huck with its sharpest claws, knocking Huck off the ladder. He lands upside down with a crash, while the observing dog snickers. “Like I said, poor l’il ol’ frightened thing”, repeats Hick in typical underplay. Huck raises the ladder again, but this time armed with a saw. He uses it to cut the limb off the tree, cat and all, rather than get claw-mauled again, and descends holding the limb in one hand. He sets the cat loose, and thinks his work is done – until the dog launches himself forward with an “On your mark. Get set. Go!”, and chases the cat across the yard and up the side of another house. The dog, not possessed of sharp claws, slides on the house wall and slips back to the ground, where he is admonished and chased away by Huck again. Huck raises a ladder to the house roof, finding the kitty clinging to the roof shingles. He pulls and tugs at the cat until the shingles give way, causing both to fall from the roof. Hick tells the audience he is lucky that cats always land on their feet, expecting te cat to flip them right-side up. Instead, Huck painfully lands on his back, the cat still clutched in his hands. ‘Except this cat”, Huck adds.

Meanwhile, Huck raises the engine ladder to the tree limb above. “Poor l’il ol’ frightened thing”, Huck says to the cat consolingly. But the cat hasn’t forgotten it’s a cat, and flails at Huck with its sharpest claws, knocking Huck off the ladder. He lands upside down with a crash, while the observing dog snickers. “Like I said, poor l’il ol’ frightened thing”, repeats Hick in typical underplay. Huck raises the ladder again, but this time armed with a saw. He uses it to cut the limb off the tree, cat and all, rather than get claw-mauled again, and descends holding the limb in one hand. He sets the cat loose, and thinks his work is done – until the dog launches himself forward with an “On your mark. Get set. Go!”, and chases the cat across the yard and up the side of another house. The dog, not possessed of sharp claws, slides on the house wall and slips back to the ground, where he is admonished and chased away by Huck again. Huck raises a ladder to the house roof, finding the kitty clinging to the roof shingles. He pulls and tugs at the cat until the shingles give way, causing both to fall from the roof. Hick tells the audience he is lucky that cats always land on their feet, expecting te cat to flip them right-side up. Instead, Huck painfully lands on his back, the cat still clutched in his hands. ‘Except this cat”, Huck adds.

The dog darts in for another attack, as Huck tries to carry the kitten home. Up the side of the house wall goes the kitten again, with Huck clinging to its tail. Huck loses his grip, and lands on the back of the dog below. The dog is scolded again, and for the third time slithers away – but still won’t quit. As Huck returns to the roof, this time managing to loosen the kitty from the shingles safely, the dog appears with a surprise new round of barking out the chimney. Huck and the kitten slide off the roof, bounce off a flagpole extending from the side wall, and land in a trash can. “That did it, kitty. I got my dander up”, resolves Huck. He approaches the dog’s house with a rolled-up newspaper, determined to administer a little discipline. The dog, doesn’t take well to being bopped on the nose, and turns his aggressions upon Huck, chasing the fireman and nipping at his tail. The kitten knows his cue, and races to the roof again. This time, Huck follows him up the side of the wall, with the dog keeping them at bay from below. The cat begins to yowl again, while Huck comments, “Shuckins. Ain’t nobody gonna hear a poor little ol’ meow like that. You needs help.” Huck thus begins meowing himself, at the top of his lungs, and the two engage in unison catcalls to anyone who will hear, for the fade out.

The dog darts in for another attack, as Huck tries to carry the kitten home. Up the side of the house wall goes the kitten again, with Huck clinging to its tail. Huck loses his grip, and lands on the back of the dog below. The dog is scolded again, and for the third time slithers away – but still won’t quit. As Huck returns to the roof, this time managing to loosen the kitty from the shingles safely, the dog appears with a surprise new round of barking out the chimney. Huck and the kitten slide off the roof, bounce off a flagpole extending from the side wall, and land in a trash can. “That did it, kitty. I got my dander up”, resolves Huck. He approaches the dog’s house with a rolled-up newspaper, determined to administer a little discipline. The dog, doesn’t take well to being bopped on the nose, and turns his aggressions upon Huck, chasing the fireman and nipping at his tail. The kitten knows his cue, and races to the roof again. This time, Huck follows him up the side of the wall, with the dog keeping them at bay from below. The cat begins to yowl again, while Huck comments, “Shuckins. Ain’t nobody gonna hear a poor little ol’ meow like that. You needs help.” Huck thus begins meowing himself, at the top of his lungs, and the two engage in unison catcalls to anyone who will hear, for the fade out.

Despite the low-key appeal of Daws Butler’s voice reads, the remake plays second-fiddle to the MGM original, and the limited animation doesn’t help, nor the droning John Seely canned score when compared to the creative themes and variations of Scott Bradley at MGM. Yet, most people will no doubt remember the Huck over the MGM version, simply from receiving endlessly-more airplays on daily TV.

Another early memory came from “The Flintstones”, in the first-season episode, Arthur Quarry’s Dance Class (Hanna-Barbera, 1/13/61). A old school-chum of Wilma’s, Gussie Gravelpit, has married Into society, and remembered Wilma when an unexpected emergency caused her and her husband to be unable to use four tickets to Bedrock’s most swank social event, a charity dance at the Rockadero Tilton. Wilma receives the tickets in the mail free, saving the 100 clams per person admission fee. She and Betty figure the boys can’t complain with no charge, and will gladly take them to the event. To their dismay, both Fred and Barney refuse, saying they’ve “got their reasons”. The reasons are – two left feet. Both of them can’t dance a step. Feeling guilty about their refusal, Barney hits on the idea, what if they surprised the girls, and learned to dance? Self-instruction in the garage from a library book proves unfruitful, and the boys have little trouble convincingly covering-up their actions to the girls by converting their moves into wrestling holds. Formal instruction will be necessary, so the boys sign up for a one-week crash course at Arthur Quarry’s Dance Studio. Barney remembers on the way home the little problem of getting out of the house every night for class without tipping off the wives – but also recalls a sure-fire answer. Joe Rockhead (in his first series appearance) has recently organized a Bedrock Volunteer Fire Department in his backyard garage. Odd, because no one recalls there ever being a fire in Bedrock – as everything is made of stone, leaving nothing to burn. As Barney explains, and Joe later elucidates to Fred, the whole operation is a cover-up for the local boys to have their pick of evenings out. Every night at 7:30, Joe rings the fire bell. Everyone comes a-running, but it is always a false alarm. Everybody can go on home – or if they so choose, do whatever they please, as long as they are out. The rank and file membership choose the second alternative, engaging in poker, bowing, taking in ball games or the fights, etc. Fred and Barney see this as their perfect out to attend dancing class – though Fred sees possibilities in it long after classes are over, and vows never to turn in his new membership. Joe wonders if his great idea might just sweep the nation.

Another early memory came from “The Flintstones”, in the first-season episode, Arthur Quarry’s Dance Class (Hanna-Barbera, 1/13/61). A old school-chum of Wilma’s, Gussie Gravelpit, has married Into society, and remembered Wilma when an unexpected emergency caused her and her husband to be unable to use four tickets to Bedrock’s most swank social event, a charity dance at the Rockadero Tilton. Wilma receives the tickets in the mail free, saving the 100 clams per person admission fee. She and Betty figure the boys can’t complain with no charge, and will gladly take them to the event. To their dismay, both Fred and Barney refuse, saying they’ve “got their reasons”. The reasons are – two left feet. Both of them can’t dance a step. Feeling guilty about their refusal, Barney hits on the idea, what if they surprised the girls, and learned to dance? Self-instruction in the garage from a library book proves unfruitful, and the boys have little trouble convincingly covering-up their actions to the girls by converting their moves into wrestling holds. Formal instruction will be necessary, so the boys sign up for a one-week crash course at Arthur Quarry’s Dance Studio. Barney remembers on the way home the little problem of getting out of the house every night for class without tipping off the wives – but also recalls a sure-fire answer. Joe Rockhead (in his first series appearance) has recently organized a Bedrock Volunteer Fire Department in his backyard garage. Odd, because no one recalls there ever being a fire in Bedrock – as everything is made of stone, leaving nothing to burn. As Barney explains, and Joe later elucidates to Fred, the whole operation is a cover-up for the local boys to have their pick of evenings out. Every night at 7:30, Joe rings the fire bell. Everyone comes a-running, but it is always a false alarm. Everybody can go on home – or if they so choose, do whatever they please, as long as they are out. The rank and file membership choose the second alternative, engaging in poker, bowing, taking in ball games or the fights, etc. Fred and Barney see this as their perfect out to attend dancing class – though Fred sees possibilities in it long after classes are over, and vows never to turn in his new membership. Joe wonders if his great idea might just sweep the nation.

Fred appears home for dinner, dressed in his new fireman’s slicker and hat, announcing his signing up for duty as a “civic minded” citizen. Wilma can’t understand why he refuses to remove his hat at the dinner table, and watches the clock down to the last second, until the bell sounds from Joe’s garage promptly at 7:30. Fred charges out of the house, upsetting the dinner table and Wilma too. “How civic minded can you get?” she ponders. Barney is right behind Fred as they race down the street to answer the call, and Betty complains she almost got trampled in the rush. This goes on for a week, the boys dispersing for the dance studio as soon as Joe announces the daily “false alarm”. Fred and Barney are more than happy for Joe’s cover-up when they meet their shapely female instructors – something the wives would never understand, and even the boys can barely understand themselves. Everything seems too suspicious for the girls, and Joe Rockhead preserves his oath of silence about the boys’ activities by providing the girls with no information upon Betty’s interrogation, claiming all information is classified. Betty finally hits upon a way to outwit them – call in a fire alarm herself, and see just what happens as to their “boys in action”. Joe receives Betty’s call, unaware of her identity, and panics. A real fire? What are they supposed to do? Oh, yeah, ring the bell. Joe sounds the alarm, even though all his volunteers have already left the station for their nightly activities. The other volunteers come running from the ball park, pool hall, poker tables, etc. But Fred and Barney miss the call, hearing only their dancing music. The other firemen jump onto the back of a bright red dinosaur with a ladder strapped to its back and a bell and siren added for equipment (a sort of miniature version of the dino engine first seen in Max Fleischer’s Granite Hotel, which was also regularly seen passing through Bedrock as a part of the original opening credits animation of the series used in the first few seasons but replaced with “Meet the Flintstones” for many years of television syndication). Everyone but Fred and Barney arrive at the Rubbles’ house, and Joe has some explaining to do – especially since in their haste, the crew even forgot to bring along a fire hose). As Wilma and Betty level a threat to spill the beans on the operation to the other wives of Bedrock, Joe breaks his oath of silence, and lets slip that the boys are at the dance studio. The girls arrive there to spot Fred and Barney engrossed in their terpsichore (which looks more like a triple-speed stumble), while their dancing partners look exhausted and ragged. The wives cut in on the surprised boys, and, even though the story sounds fishy even to them, Fred and Barney tell the wives the truth. The wives are pleasantly surprised, embarrassed for mistrusting the husbands, and completely forgiving. All attend the big dance, and, while the boys continue to dance in the same step for every number like tippytoeing stumblebums, the girls remain quite happy at them for being “in there pitching”, and all dance the night away as the episode closes.

Fred appears home for dinner, dressed in his new fireman’s slicker and hat, announcing his signing up for duty as a “civic minded” citizen. Wilma can’t understand why he refuses to remove his hat at the dinner table, and watches the clock down to the last second, until the bell sounds from Joe’s garage promptly at 7:30. Fred charges out of the house, upsetting the dinner table and Wilma too. “How civic minded can you get?” she ponders. Barney is right behind Fred as they race down the street to answer the call, and Betty complains she almost got trampled in the rush. This goes on for a week, the boys dispersing for the dance studio as soon as Joe announces the daily “false alarm”. Fred and Barney are more than happy for Joe’s cover-up when they meet their shapely female instructors – something the wives would never understand, and even the boys can barely understand themselves. Everything seems too suspicious for the girls, and Joe Rockhead preserves his oath of silence about the boys’ activities by providing the girls with no information upon Betty’s interrogation, claiming all information is classified. Betty finally hits upon a way to outwit them – call in a fire alarm herself, and see just what happens as to their “boys in action”. Joe receives Betty’s call, unaware of her identity, and panics. A real fire? What are they supposed to do? Oh, yeah, ring the bell. Joe sounds the alarm, even though all his volunteers have already left the station for their nightly activities. The other volunteers come running from the ball park, pool hall, poker tables, etc. But Fred and Barney miss the call, hearing only their dancing music. The other firemen jump onto the back of a bright red dinosaur with a ladder strapped to its back and a bell and siren added for equipment (a sort of miniature version of the dino engine first seen in Max Fleischer’s Granite Hotel, which was also regularly seen passing through Bedrock as a part of the original opening credits animation of the series used in the first few seasons but replaced with “Meet the Flintstones” for many years of television syndication). Everyone but Fred and Barney arrive at the Rubbles’ house, and Joe has some explaining to do – especially since in their haste, the crew even forgot to bring along a fire hose). As Wilma and Betty level a threat to spill the beans on the operation to the other wives of Bedrock, Joe breaks his oath of silence, and lets slip that the boys are at the dance studio. The girls arrive there to spot Fred and Barney engrossed in their terpsichore (which looks more like a triple-speed stumble), while their dancing partners look exhausted and ragged. The wives cut in on the surprised boys, and, even though the story sounds fishy even to them, Fred and Barney tell the wives the truth. The wives are pleasantly surprised, embarrassed for mistrusting the husbands, and completely forgiving. All attend the big dance, and, while the boys continue to dance in the same step for every number like tippytoeing stumblebums, the girls remain quite happy at them for being “in there pitching”, and all dance the night away as the episode closes.

Here’s a clip (below), full episode click here.

Another early TV production for another studio, Popeye the Fireman (Jack Kinney/King Features, circa 1960 – Jack Kinney, dir.), is, for the most part, an exercise in ultra-cheap budget cutting and awkwardness. A tall high-rise hotel exhibits activity on the two topmost floors. Belching clouds of black smoke pour out a window on the second-to-last story, and directly above, the screams of a damsel in distress are heard from the topmost window. The damsel is, of course, Olive, shouting for anyone to rescue her. The only one within earshot is Wimpy on the pavement below, who reacts in slow-motion between taking bites from his latest hamburger. He finally decides he should report this to the proper authorities, but deliberates as to which way he should go. Finally stumbling upon a call box, he reads instructions: Break glass and pull lever down. “Seems rather wasteful”, he surmises. However, he finally does what the sign says, and a bell rings in the station where Popeye sleeps among a crew of other firemen. A complete continuity error has the location of the fire called out over a loudspeaker – yet Popeye spelling out the name of the hotel as if he is reading the name off some sort of display board that isn’t there. “That’s where me sweetie is stayin’.” Popeye’s sailor trousers wait in standing position at the bottom of the fire pole for Popeye to land, and his shirt and fire hat somehow sail down under their own power to meet Popeye on ground level, making him presentable for the rescue. Popeye assumes position as the wheel man on the tail end of the extension ladder. In stilted and crude animation, the engine proceeds down the street, with Popeye’s end of the engine swerving forward until it is parallel on the street with the driver’s cab.

Another early TV production for another studio, Popeye the Fireman (Jack Kinney/King Features, circa 1960 – Jack Kinney, dir.), is, for the most part, an exercise in ultra-cheap budget cutting and awkwardness. A tall high-rise hotel exhibits activity on the two topmost floors. Belching clouds of black smoke pour out a window on the second-to-last story, and directly above, the screams of a damsel in distress are heard from the topmost window. The damsel is, of course, Olive, shouting for anyone to rescue her. The only one within earshot is Wimpy on the pavement below, who reacts in slow-motion between taking bites from his latest hamburger. He finally decides he should report this to the proper authorities, but deliberates as to which way he should go. Finally stumbling upon a call box, he reads instructions: Break glass and pull lever down. “Seems rather wasteful”, he surmises. However, he finally does what the sign says, and a bell rings in the station where Popeye sleeps among a crew of other firemen. A complete continuity error has the location of the fire called out over a loudspeaker – yet Popeye spelling out the name of the hotel as if he is reading the name off some sort of display board that isn’t there. “That’s where me sweetie is stayin’.” Popeye’s sailor trousers wait in standing position at the bottom of the fire pole for Popeye to land, and his shirt and fire hat somehow sail down under their own power to meet Popeye on ground level, making him presentable for the rescue. Popeye assumes position as the wheel man on the tail end of the extension ladder. In stilted and crude animation, the engine proceeds down the street, with Popeye’s end of the engine swerving forward until it is parallel on the street with the driver’s cab.

“Who’s driving this heap, you or me?” asks the engine driver. Popeye swivels back to proper position as the engine arrives at the hotel. The engine brakes so suddenly, one section of ladder shoots backwards, breaking its rungs across Popeye’s chin. Popeye raises a tall sectional ladder, and discovers to his surprise that the source of the smoke is not a fire at all, but a large black cigar being smoked by Brutus in the window below. “Why that cigar puffin’ ruffian”, remarks Popeye. “Say Mister when ya speak to me, Buster”, responds Brutus, pushing Popeye’s ladder away from the building. Popeye resteadies the ladder, and tries to pivot it to Olive’s window. It’s top section dips in angle back to Brutus’s window. “Has the little il’ fireman lost his way?” chortles Brutus, socking Popeye, who clings desperately to the top ladder rung. Popeye tries again to line up with Olive’s window, but Brutus yanks the end of the ladder down to him again, shifting Popeye off balance, and causing the sailor to descend in a fall which splits the ladder rungs one by one to the ground. Just as Popeye attempts to re-collect his thoughts, somebody turns on the water pressure to the fire hose, sending the sailor flying helplessly through the air, while Brutus laughs uproariously. However, the bully doesn’t like it when he gets doused by the water – so he grabs hold of the flying hose, tying it in a knot. Popeye stands upon the inflating bubble building in the hose, and the canvas explodes, leaving Popeye briefly treading water on a geyser from the hydrant below, then falling with a crash as the water is shut off. “Where’s my spinach at?”, Popeye fumes, and the leafy secret weapon is once again ingested. On a new section of ladder, Popeye ascends, socks Brutus in the mush, then uses the ladder as a springboard to launch Brutus across town, where he lands in a billboard with his head protruding from the sign. The sign reads “Help Prevent Fires”, and Brutus, like a famous Times Square ad board featuring real puffs from a smoking man, breathes a series of black puffs into the air from the leftover cigar smoke in his lungs. Olive and Popeye finally embrace in her room, while Wimpy ascends to the window ledge upon the fire ladder, asking if he can gladly pay Tuesday for a hamburger today. “Not today”, says Popeye, pulling the windowshade shut so that he and Olive can smooch. “Don’t know till you try”, says Wimpy to the audience, for the fade out.

“Who’s driving this heap, you or me?” asks the engine driver. Popeye swivels back to proper position as the engine arrives at the hotel. The engine brakes so suddenly, one section of ladder shoots backwards, breaking its rungs across Popeye’s chin. Popeye raises a tall sectional ladder, and discovers to his surprise that the source of the smoke is not a fire at all, but a large black cigar being smoked by Brutus in the window below. “Why that cigar puffin’ ruffian”, remarks Popeye. “Say Mister when ya speak to me, Buster”, responds Brutus, pushing Popeye’s ladder away from the building. Popeye resteadies the ladder, and tries to pivot it to Olive’s window. It’s top section dips in angle back to Brutus’s window. “Has the little il’ fireman lost his way?” chortles Brutus, socking Popeye, who clings desperately to the top ladder rung. Popeye tries again to line up with Olive’s window, but Brutus yanks the end of the ladder down to him again, shifting Popeye off balance, and causing the sailor to descend in a fall which splits the ladder rungs one by one to the ground. Just as Popeye attempts to re-collect his thoughts, somebody turns on the water pressure to the fire hose, sending the sailor flying helplessly through the air, while Brutus laughs uproariously. However, the bully doesn’t like it when he gets doused by the water – so he grabs hold of the flying hose, tying it in a knot. Popeye stands upon the inflating bubble building in the hose, and the canvas explodes, leaving Popeye briefly treading water on a geyser from the hydrant below, then falling with a crash as the water is shut off. “Where’s my spinach at?”, Popeye fumes, and the leafy secret weapon is once again ingested. On a new section of ladder, Popeye ascends, socks Brutus in the mush, then uses the ladder as a springboard to launch Brutus across town, where he lands in a billboard with his head protruding from the sign. The sign reads “Help Prevent Fires”, and Brutus, like a famous Times Square ad board featuring real puffs from a smoking man, breathes a series of black puffs into the air from the leftover cigar smoke in his lungs. Olive and Popeye finally embrace in her room, while Wimpy ascends to the window ledge upon the fire ladder, asking if he can gladly pay Tuesday for a hamburger today. “Not today”, says Popeye, pulling the windowshade shut so that he and Olive can smooch. “Don’t know till you try”, says Wimpy to the audience, for the fade out.

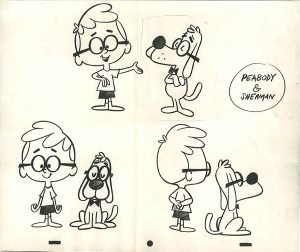

Nero (Jay Ward, Peabody’s Improbable History, 12/25/60) – The WABAC machine is all warmed up – to transport Mr. Peabody and Sherman to 64 A.D. to meet one of history’s most famous violinists. “Jack Benny?”, asks Sherman. “No, that would be 39 A.D.”, responds Peabody. Instead, they arrive at the palace of Nero in Rome. Billowing smoke emerges from the doorway, and Peabody and Sherman grab buckets to fill from a fountain to douse the blaze, It turns out this time, it wasn’t a fire at all, but a mere barbecue in progress – and our heroes have made the Emperor’s steak soggy. Nero complains that everyone blames fires upon him, though he isn’t responsible Even as he speaks, his throne erupts in flames. Our heroes again man the buckets, putting out the blaze, but discover Nero ignoring the fire-fighting, ad instead standing on a pedestal playing his violin. He refers to this as a “quirk” that overtakes him whenever a fire is present, and asks if they want to hear another selection. Peabody ponders as to the source of the mysterious fires, and for a motive. From Nero’s “quirk” and his poor fiddling style, Peabody concludes that the one most likely to profit from such activity would be someone offering music lessons – which Nero obviously needs, and they track down the only violin teacher in town a certain Odd Puss Rex. The creepy character, who talks like Boris Karloff, is in the process of fashioning a new violin for Nero, equipped with a special bow – actually, a giant matchstick. Peabody and Sherman burst in, and reveal that they are aware of Rex’s playing with fire, and advise him to desist or they will inform the Emperor. Rex declares he was about to abandon his ways and leave the city anyway, and that his overnight bags are packed I a back room. As soon as the door to the room is opened, Rex pushes our heroes in ad bolts the door, leaving them in a stone-walled cell room. A henchman of Rex, also imprisoned within, tips the boys off about the rigged violin, and fears they will all be trapped when the city erupts in flames. Peabody plots a break-out, handing Sherman another violin found within the room. “But I can’t play”, says Sherman. “I know that”, replies Peabody. Within five minutes, the wails of Sherman’s fiddle from within the barred cell windows attract an irate mob of citizens, who batter down the wall of the cell with a battering ram, just to get the tone-deaf Sherman out of earshot. Our heroes race to the Palace, where Nero is about to give a concert (providing an out-of-period topical reference to his first number being a Gerry Mulligan arrangement).

Nero (Jay Ward, Peabody’s Improbable History, 12/25/60) – The WABAC machine is all warmed up – to transport Mr. Peabody and Sherman to 64 A.D. to meet one of history’s most famous violinists. “Jack Benny?”, asks Sherman. “No, that would be 39 A.D.”, responds Peabody. Instead, they arrive at the palace of Nero in Rome. Billowing smoke emerges from the doorway, and Peabody and Sherman grab buckets to fill from a fountain to douse the blaze, It turns out this time, it wasn’t a fire at all, but a mere barbecue in progress – and our heroes have made the Emperor’s steak soggy. Nero complains that everyone blames fires upon him, though he isn’t responsible Even as he speaks, his throne erupts in flames. Our heroes again man the buckets, putting out the blaze, but discover Nero ignoring the fire-fighting, ad instead standing on a pedestal playing his violin. He refers to this as a “quirk” that overtakes him whenever a fire is present, and asks if they want to hear another selection. Peabody ponders as to the source of the mysterious fires, and for a motive. From Nero’s “quirk” and his poor fiddling style, Peabody concludes that the one most likely to profit from such activity would be someone offering music lessons – which Nero obviously needs, and they track down the only violin teacher in town a certain Odd Puss Rex. The creepy character, who talks like Boris Karloff, is in the process of fashioning a new violin for Nero, equipped with a special bow – actually, a giant matchstick. Peabody and Sherman burst in, and reveal that they are aware of Rex’s playing with fire, and advise him to desist or they will inform the Emperor. Rex declares he was about to abandon his ways and leave the city anyway, and that his overnight bags are packed I a back room. As soon as the door to the room is opened, Rex pushes our heroes in ad bolts the door, leaving them in a stone-walled cell room. A henchman of Rex, also imprisoned within, tips the boys off about the rigged violin, and fears they will all be trapped when the city erupts in flames. Peabody plots a break-out, handing Sherman another violin found within the room. “But I can’t play”, says Sherman. “I know that”, replies Peabody. Within five minutes, the wails of Sherman’s fiddle from within the barred cell windows attract an irate mob of citizens, who batter down the wall of the cell with a battering ram, just to get the tone-deaf Sherman out of earshot. Our heroes race to the Palace, where Nero is about to give a concert (providing an out-of-period topical reference to his first number being a Gerry Mulligan arrangement).

Peabody swings on a rope from a balcony seat to the stage, plucking away the matchstick bow from Nero. Odd Piss Rex, however, swings from the opposite balcony, replacing a duplicate bow into Nero’s hand. Nero strikes the G-string, and his fiddle erupts into a blaze. “I’m afraid it’s curtains”, says Sherman – giving Peabody an idea. Looking up at the stage curtains, Peabody spots the word he is looking for – asbestos. (Of course, such things would in reality not be invented yet for many a day.) Peabody loosens the knot on the supporting curtain rope, bringing the curtain down on Nero and his performance to smother the flames. In desperation to start a fire somewhere, Odd Puss Rex runs around in the audience, fiving everyone he can reach a hotfoot. Unfortunately, the last person he gives a hotfoot to is the Chief of Police, ending Rex’s plans. Nero congratulates the boys on saving the palace, but embarks in a chariot to host a public barbecue at the center of the city, which e promises will be “big, big, big!” Realizing this is no time to be in Rome, the boys plan a hasty departure, but find time to purchase a souvenir from another music shop – an odd-shaped string instrument constructed by a craftsman named Strada, who made various Instruments. His lips wincing in preparation for what he knows will be the expected closing bad pun, Sherman asks in obligatory fashion, “Is that why they call it a Strada-various?” “That’s why, Sherman”, responds Peabody, covering his eyes, barely able to carry through with the pun himself.

Peabody swings on a rope from a balcony seat to the stage, plucking away the matchstick bow from Nero. Odd Piss Rex, however, swings from the opposite balcony, replacing a duplicate bow into Nero’s hand. Nero strikes the G-string, and his fiddle erupts into a blaze. “I’m afraid it’s curtains”, says Sherman – giving Peabody an idea. Looking up at the stage curtains, Peabody spots the word he is looking for – asbestos. (Of course, such things would in reality not be invented yet for many a day.) Peabody loosens the knot on the supporting curtain rope, bringing the curtain down on Nero and his performance to smother the flames. In desperation to start a fire somewhere, Odd Puss Rex runs around in the audience, fiving everyone he can reach a hotfoot. Unfortunately, the last person he gives a hotfoot to is the Chief of Police, ending Rex’s plans. Nero congratulates the boys on saving the palace, but embarks in a chariot to host a public barbecue at the center of the city, which e promises will be “big, big, big!” Realizing this is no time to be in Rome, the boys plan a hasty departure, but find time to purchase a souvenir from another music shop – an odd-shaped string instrument constructed by a craftsman named Strada, who made various Instruments. His lips wincing in preparation for what he knows will be the expected closing bad pun, Sherman asks in obligatory fashion, “Is that why they call it a Strada-various?” “That’s why, Sherman”, responds Peabody, covering his eyes, barely able to carry through with the pun himself.

And now, to the continuing screen career of the bruin in dungarees and a ranger hat. Smoke Screams (Paramount/King Features, Snuffy Smith, circa 1964 – Seymour Kneitel, dir., Jim Tyer, anim., Howard Post, story) finds Snuffy Smith in a property dispute with a certain “Chief Seymour”, a renegade Indian. Odd how so many King Features cartoons directed by Kneitel feature Seymours – also including “Snuffy’s Song” reviewed last week, and a Beetle Bailey episode which features a rival gob named Seymour S. Seymour (any guesses what the middle initial stands for?). The Chief, who speaks like Hugh Herbert, observes a trail of smoke puffs coming from Snuffy’s pipe as he wanders though the hills, and mistakes them for smoke signals, criticizing them for “bad handwriting” and misspellings. When the chief investigates the source, Snuffy insists he was just smokin’, not signallin’. The chief declares him a trespasser upon his own “Happy Hunting Grounds”, and produces an envelope in which he claims is his deed to these lands. Snuffy tears it open, to revel more puffs of white smoke which rise from the envelope, the chief translating them as declaring him legal owner. “Well, I’ll be dad-burned. What’s the rest of it say”, asks Snuffy of the envelope’s last puffs. “It say-um Chief Seymour also own Brooklyn Bridge. Me get-um big bargain. Fellow needed beads.” Snuffy protests that this land was handed down to him from his great grandpappy, and insists the Chief is the one who must shoo. Battle lines are drawn as Snuffy trods upon the chief’s foot. Seymour reaches for his tomahawk, but Snuffy advises that he is holding it wrong. Snuffy lines the chief up in a pose as if giving him golf instruction for proper swing and follow-through – resulting in the chief’s swing conking himself out cold upon the head. “Aw, ya went and bent your arm”, chuckles Snuffy.

And now, to the continuing screen career of the bruin in dungarees and a ranger hat. Smoke Screams (Paramount/King Features, Snuffy Smith, circa 1964 – Seymour Kneitel, dir., Jim Tyer, anim., Howard Post, story) finds Snuffy Smith in a property dispute with a certain “Chief Seymour”, a renegade Indian. Odd how so many King Features cartoons directed by Kneitel feature Seymours – also including “Snuffy’s Song” reviewed last week, and a Beetle Bailey episode which features a rival gob named Seymour S. Seymour (any guesses what the middle initial stands for?). The Chief, who speaks like Hugh Herbert, observes a trail of smoke puffs coming from Snuffy’s pipe as he wanders though the hills, and mistakes them for smoke signals, criticizing them for “bad handwriting” and misspellings. When the chief investigates the source, Snuffy insists he was just smokin’, not signallin’. The chief declares him a trespasser upon his own “Happy Hunting Grounds”, and produces an envelope in which he claims is his deed to these lands. Snuffy tears it open, to revel more puffs of white smoke which rise from the envelope, the chief translating them as declaring him legal owner. “Well, I’ll be dad-burned. What’s the rest of it say”, asks Snuffy of the envelope’s last puffs. “It say-um Chief Seymour also own Brooklyn Bridge. Me get-um big bargain. Fellow needed beads.” Snuffy protests that this land was handed down to him from his great grandpappy, and insists the Chief is the one who must shoo. Battle lines are drawn as Snuffy trods upon the chief’s foot. Seymour reaches for his tomahawk, but Snuffy advises that he is holding it wrong. Snuffy lines the chief up in a pose as if giving him golf instruction for proper swing and follow-through – resulting in the chief’s swing conking himself out cold upon the head. “Aw, ya went and bent your arm”, chuckles Snuffy.

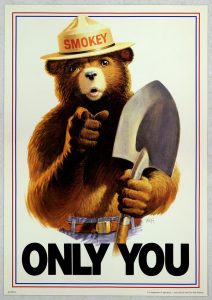

The Chief revives, and takes up a bow and arrow. Snuffy at first runs, but then suggests smoking sa peace pipe like civilized folk. He suggests the chief read this signal – as he blows a cloud of pipe smoke in the chief’s face, leaving him gasping for air, while Snuffy beats a retreat. “Oooh, you’re gonna get it”, declares the chief, deciding to fight smoke with flaming arrows. Before he is able to fire a shot, the chief and Snuffy are stopped in their tracks by a visitor – Smokey the Bear. (Smokey appears younger here than usual, shorter and more cub-loke in appearance, but has the usual deep voice and ranger’s garb. “Carelessness with fire ruins acres of fine timberland yearly. Help stomp our forest fires by making sure all fires are out before you leave.” “That’s right, Smokey”, says Snuffy, while Seymour observes, “Bear speak truth. Also have nice hat”, as the two stomp out the fiery arrow-point. Smokey saunters off on his patrol, giving a wink to the camera. But the property battle continues, as Snuffy is caught in a box canyon, and the chief declares it’s time for a little archery practice, launching four arrows at Snuffy at once. Holding his nose, Snuffy produces from nowhere a skink, holding it up in the path of the arrows. The arrow-tips take one whiff of the critter, and turn tail, sailing right back at the chief, who flees with the arrows in close pursuit. The final sequence however, has the chief getting mischievous revenge, determining if he can’t have the property, then Snuffy will have no peace. The chief sends up his own set of smoke signals to the local Indian community, reading “For sale cheap – Property of Snuffy Smith.” All at once, Indians from miles around show up on Snuffy’s doorstep, deluging him with offers of wampum belts, beads, magic bones, etc., one of them commenting “Here’s where we get even for Manhattan Island swindle.” Snuffy can hardly get a word in edgewise, shouting at the top of his lungs for the iris out, “It ain’t for sale, I tell ya. Keemo-savvy??”

The Chief revives, and takes up a bow and arrow. Snuffy at first runs, but then suggests smoking sa peace pipe like civilized folk. He suggests the chief read this signal – as he blows a cloud of pipe smoke in the chief’s face, leaving him gasping for air, while Snuffy beats a retreat. “Oooh, you’re gonna get it”, declares the chief, deciding to fight smoke with flaming arrows. Before he is able to fire a shot, the chief and Snuffy are stopped in their tracks by a visitor – Smokey the Bear. (Smokey appears younger here than usual, shorter and more cub-loke in appearance, but has the usual deep voice and ranger’s garb. “Carelessness with fire ruins acres of fine timberland yearly. Help stomp our forest fires by making sure all fires are out before you leave.” “That’s right, Smokey”, says Snuffy, while Seymour observes, “Bear speak truth. Also have nice hat”, as the two stomp out the fiery arrow-point. Smokey saunters off on his patrol, giving a wink to the camera. But the property battle continues, as Snuffy is caught in a box canyon, and the chief declares it’s time for a little archery practice, launching four arrows at Snuffy at once. Holding his nose, Snuffy produces from nowhere a skink, holding it up in the path of the arrows. The arrow-tips take one whiff of the critter, and turn tail, sailing right back at the chief, who flees with the arrows in close pursuit. The final sequence however, has the chief getting mischievous revenge, determining if he can’t have the property, then Snuffy will have no peace. The chief sends up his own set of smoke signals to the local Indian community, reading “For sale cheap – Property of Snuffy Smith.” All at once, Indians from miles around show up on Snuffy’s doorstep, deluging him with offers of wampum belts, beads, magic bones, etc., one of them commenting “Here’s where we get even for Manhattan Island swindle.” Snuffy can hardly get a word in edgewise, shouting at the top of his lungs for the iris out, “It ain’t for sale, I tell ya. Keemo-savvy??”

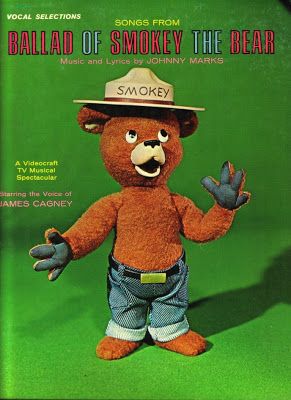

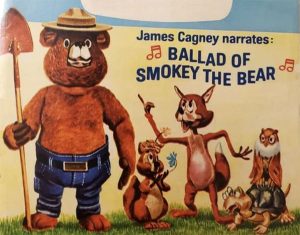

The Ballad of Smokey the Bear (Rankin-Bass, 11/24/66 – Larry Roemer, dir.) – A less-than-classic example of how difficult it can be to have lightning strike twice. Rankin-Bass, who had dabbled in television with 2-D projects like “Tales of the Wizard of Oz” and stop motion efforts such as “The New Adventures of Pinocchio” with only limited success, really put themselves on the map with the universal appeal and acclaim of their prime-time holiday perennial, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” in 1964. Obtaining a major sponsor, billing the show as the “General Electric Fantasy Theater”, the deer’s adventures secured a permanent berth for yearly rerun, as well as successful product tie-ins with promotions geared with the sale of appliances (free soundtrack records with purchase, of which I own two original copies), given the extra push with animated commercials by Santa’s elves. Two years later, the studio was ready to try it again – backed by the same sponsor, and reuniting much of the creative personnel of the original special, including songwriter Johnny Marks. And, following in the tradition of Rudolph, a name celebrity was chosen to narrate the tale – appearing in his only cartoon voice-over, the legendary James Cagney (cast as Smokey’s older brother). The results, however, fell far short of the stellar motif used in the General Electric sponsor opening. No hit songs were produced (though Columbia records tried a non-soundtrack single, and RCA Camden also featured the theme as a title cut on a children’s album). Although some attempts at mild humor were included in the script, the dialogue featured no take-away catch-lines or quotable gags, and in several portions of the show approached a more somber mood, with Smokey becoming for a time a loner and a recluse. Despite animation that was generally up to studio par, and a fairly accurate rendering of the recognizable bear in 3-D form, the show had no lasting effect nor staying power, and even with heavy advance promotion, failed so poorly to hold an audience, that it would receive no return network screening, and would take decades before receiving any occasional airing as a one-shot rerun on some small local station. (It once aired locally in Southern California on UHF station channel 56 from Orange County, as a noontime filler on a Saturday afternoon – which I only discovered by pure accidental tuning in on the last three minutes.) I was among those few who saw it through in its single network run as a child, and, though less than impressed with it, wondered if there would be another soundtrack album offered with GE appliances. There never was.

The Ballad of Smokey the Bear (Rankin-Bass, 11/24/66 – Larry Roemer, dir.) – A less-than-classic example of how difficult it can be to have lightning strike twice. Rankin-Bass, who had dabbled in television with 2-D projects like “Tales of the Wizard of Oz” and stop motion efforts such as “The New Adventures of Pinocchio” with only limited success, really put themselves on the map with the universal appeal and acclaim of their prime-time holiday perennial, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” in 1964. Obtaining a major sponsor, billing the show as the “General Electric Fantasy Theater”, the deer’s adventures secured a permanent berth for yearly rerun, as well as successful product tie-ins with promotions geared with the sale of appliances (free soundtrack records with purchase, of which I own two original copies), given the extra push with animated commercials by Santa’s elves. Two years later, the studio was ready to try it again – backed by the same sponsor, and reuniting much of the creative personnel of the original special, including songwriter Johnny Marks. And, following in the tradition of Rudolph, a name celebrity was chosen to narrate the tale – appearing in his only cartoon voice-over, the legendary James Cagney (cast as Smokey’s older brother). The results, however, fell far short of the stellar motif used in the General Electric sponsor opening. No hit songs were produced (though Columbia records tried a non-soundtrack single, and RCA Camden also featured the theme as a title cut on a children’s album). Although some attempts at mild humor were included in the script, the dialogue featured no take-away catch-lines or quotable gags, and in several portions of the show approached a more somber mood, with Smokey becoming for a time a loner and a recluse. Despite animation that was generally up to studio par, and a fairly accurate rendering of the recognizable bear in 3-D form, the show had no lasting effect nor staying power, and even with heavy advance promotion, failed so poorly to hold an audience, that it would receive no return network screening, and would take decades before receiving any occasional airing as a one-shot rerun on some small local station. (It once aired locally in Southern California on UHF station channel 56 from Orange County, as a noontime filler on a Saturday afternoon – which I only discovered by pure accidental tuning in on the last three minutes.) I was among those few who saw it through in its single network run as a child, and, though less than impressed with it, wondered if there would be another soundtrack album offered with GE appliances. There never was.

The film attempts to create a new origin story for our hero, largely failing to follow any of the reputed reality of a ranger allegedly rescuing the cub from a fire and giving him his name and identity. It takes quite a bit of time to get to the point, with dallies with him as a young cub, exploring his first honey tree and first dose of bee stings, flirting with a girl cub named Delilah, and accidentally battering a beaver dam at her persuasion. About fifteen minutes into the film, we finally see smoke, as Smokey is caught in a forest fire alone. He remembers his mother’s warnings that, when in danger, climb the tallest tree. The lesson saves his life, though he is mildly burnt and fur singed. But when his brother brings him down, he is not the same frivolous cub, bit traumatically frightened. On top of that, his mother, who also tried to search for him in the fire, is lost to the flames. (Mysteriously, Delilah also disappears at this point entirely from the script – potentially indicating that the original story may have intended to add the additional heartbreak of losing her to the fire too. It seems as though the network may have thought losing a Mom had precedent in stories such as Bambi, but losing a kid would be too much for younger viewers to “bear”.) The change of mood is at times a bit painful to watch, making the film more a drama than fit for a musical-comedy treatment. In fact, some numbers, although musically sound (the most notable being “Don’t Wait”, performed by a beaver couple), seem decidedly out of place for the story line. The plot gets even stranger as Smokey matures to young adulthood. As the forest is invaded by a destructive animal no one has ever heard of – a gorilla escaped from a zoo, who has acquired the human-like traits of residing in an abandoned hunter’s cabin, polluting the stream with debris, lighting fires in the fireplace of the cabin, and even carelessly – smoking! The animals all attempt to devise plans to trap and remove the gorilla from the forest. Only Smokey, who barely speaks to anyone but is brother, and remains afraid even to leave his cave, contributes no ideas. In fact, just the sight of smoke from the cabin chimney sends him clinging to a tree again. Embarrassed by mild ridicule of his cowardice, Smokey breaks off contact with his brother as well, and wanders the forest alone. He observes at a distance the plans and contraptions of the other animals each fail to bring down the gorilla, A turtle – the oldest animal in the woods – encounters Smokey observing the failed plans, and reminds Smokey that unless the gorilla’s carelessness with fire is thwarted, the whole forest might burn down again. He attempts to inspire Smokey to come up with a plan of his own, by asking him when in the woods tonight to listen to the voices of the only living things older than he in the forest – the trees. Smokey does just that, and imagines a chorus of voices calling, “Save us, Smokey.”

The film attempts to create a new origin story for our hero, largely failing to follow any of the reputed reality of a ranger allegedly rescuing the cub from a fire and giving him his name and identity. It takes quite a bit of time to get to the point, with dallies with him as a young cub, exploring his first honey tree and first dose of bee stings, flirting with a girl cub named Delilah, and accidentally battering a beaver dam at her persuasion. About fifteen minutes into the film, we finally see smoke, as Smokey is caught in a forest fire alone. He remembers his mother’s warnings that, when in danger, climb the tallest tree. The lesson saves his life, though he is mildly burnt and fur singed. But when his brother brings him down, he is not the same frivolous cub, bit traumatically frightened. On top of that, his mother, who also tried to search for him in the fire, is lost to the flames. (Mysteriously, Delilah also disappears at this point entirely from the script – potentially indicating that the original story may have intended to add the additional heartbreak of losing her to the fire too. It seems as though the network may have thought losing a Mom had precedent in stories such as Bambi, but losing a kid would be too much for younger viewers to “bear”.) The change of mood is at times a bit painful to watch, making the film more a drama than fit for a musical-comedy treatment. In fact, some numbers, although musically sound (the most notable being “Don’t Wait”, performed by a beaver couple), seem decidedly out of place for the story line. The plot gets even stranger as Smokey matures to young adulthood. As the forest is invaded by a destructive animal no one has ever heard of – a gorilla escaped from a zoo, who has acquired the human-like traits of residing in an abandoned hunter’s cabin, polluting the stream with debris, lighting fires in the fireplace of the cabin, and even carelessly – smoking! The animals all attempt to devise plans to trap and remove the gorilla from the forest. Only Smokey, who barely speaks to anyone but is brother, and remains afraid even to leave his cave, contributes no ideas. In fact, just the sight of smoke from the cabin chimney sends him clinging to a tree again. Embarrassed by mild ridicule of his cowardice, Smokey breaks off contact with his brother as well, and wanders the forest alone. He observes at a distance the plans and contraptions of the other animals each fail to bring down the gorilla, A turtle – the oldest animal in the woods – encounters Smokey observing the failed plans, and reminds Smokey that unless the gorilla’s carelessness with fire is thwarted, the whole forest might burn down again. He attempts to inspire Smokey to come up with a plan of his own, by asking him when in the woods tonight to listen to the voices of the only living things older than he in the forest – the trees. Smokey does just that, and imagines a chorus of voices calling, “Save us, Smokey.”

The next day, Smokey is spitted into direct action. He approaches the cabin directly, and with a shovel, undermines a corner of its support for the foundation. The log cabin collapses, with the gorilla inside. Unfortunately, the gorilla’s had the hearth fire burning again, and the logs become set on fire. Smokey grabs a pail, running to a nearby stream, and throwing a bucket of water upon the flame. But his single effort as little effect as surrounding logs continue to stoke the fire. Smokey finally breaks his silence to the other animals, adopting a take-charge mode to organize them to all join his efforts in forming a bucket brigade to keep the fire from spreading. The animals combine to battle the blaze, while Smokey discovers the ape pinned down beneath several of the logs, and heroically rescues him from the peril. Though unable to speak, the ape responds in body language approaching a handshake of thanks, and becomes pacified and a friend to Smokey, who leads the ape back to the zoo, while the other animals, having put out the flames, celebrate his bravery and courage. Smokey becomes the legend of the forest, and word spreads of his deed to the forest service, who send him his hat and spade as an honorary ranger. All ends happily, with Smokey and his brother observing a new generation of cubs about to encounter their own first honey tree, as the two elder bears conclude “Some things you just gotta learn for yourself.”

The next day, Smokey is spitted into direct action. He approaches the cabin directly, and with a shovel, undermines a corner of its support for the foundation. The log cabin collapses, with the gorilla inside. Unfortunately, the gorilla’s had the hearth fire burning again, and the logs become set on fire. Smokey grabs a pail, running to a nearby stream, and throwing a bucket of water upon the flame. But his single effort as little effect as surrounding logs continue to stoke the fire. Smokey finally breaks his silence to the other animals, adopting a take-charge mode to organize them to all join his efforts in forming a bucket brigade to keep the fire from spreading. The animals combine to battle the blaze, while Smokey discovers the ape pinned down beneath several of the logs, and heroically rescues him from the peril. Though unable to speak, the ape responds in body language approaching a handshake of thanks, and becomes pacified and a friend to Smokey, who leads the ape back to the zoo, while the other animals, having put out the flames, celebrate his bravery and courage. Smokey becomes the legend of the forest, and word spreads of his deed to the forest service, who send him his hat and spade as an honorary ranger. All ends happily, with Smokey and his brother observing a new generation of cubs about to encounter their own first honey tree, as the two elder bears conclude “Some things you just gotta learn for yourself.”

An odd coda, indicative of the lack of lasting appeal this special had on the viewing audience, was the inclusion of one of its brief songs, “Tell Your Secret To a Turtle”, in a later holiday special produced by an entirely different studio, The Tiny Tree (DePatie-Freleng, 1975) for which Johnny Marks again contributed a score. Marks apparently though no one would remember the Smokey special, and dug into his trunk of old sheet music to use the same song for filler once again. Rankin-Bass appears to have made no complaint, and probably wasn’t even paid a royalty. The latter special would prove just about as unmemorable, if not more so, than “Smokey”, qualifying the shared tune for nomination as an unofficial anthem for failure.

An odd coda, indicative of the lack of lasting appeal this special had on the viewing audience, was the inclusion of one of its brief songs, “Tell Your Secret To a Turtle”, in a later holiday special produced by an entirely different studio, The Tiny Tree (DePatie-Freleng, 1975) for which Johnny Marks again contributed a score. Marks apparently though no one would remember the Smokey special, and dug into his trunk of old sheet music to use the same song for filler once again. Rankin-Bass appears to have made no complaint, and probably wasn’t even paid a royalty. The latter special would prove just about as unmemorable, if not more so, than “Smokey”, qualifying the shared tune for nomination as an unofficial anthem for failure.

Not content with being defeated in battle, Rankin-Bass refused to give up on the name-recognition of Smokey, and would unleash on the Saturday morning audience in 1969 on ABC “The Smokey Bear Show”. Yes, it’s about as hopeless a concept as it sounds. Produced in 2-D animation (farmed out to Toei Animation in Japan), it relied for its plot material upon watered-down stories from a series of Dell comic books, placing Smokey among a community of “mischievous” animal characters, among whom is to be found not a single standout personality to bear the weight of a storyline. While Smokey himself is rendered fairly on model, remaining character animation is ho-hum at best, with no discernable amount of effort or distinctive style included in the presentation – and no genuine laughs. Smokey himself is played, as usual, as a dead-serious straight-man, usually somewhat aghast at his companions’ behavior, and ready to lecture at the drop of his ranger hat. It’s not exactly a 30-minute PSA, but might have had more purpose if it was. Each episode consisted of multiple short segments, one featuring junior adventures of Smokey as a cub. A scant 17 programs were produced, yet kept in rerun for two seasons, despite low ratings. I never watched it as a child, and after finally sitting through a representative sample, I am ready to write it off as a loss. The series might have proved much better if, instead of settling into a “funny animals: vein the studio couldn’t live up to, it had tried for serous action-adventure, with Smokey solving various situations of peril. But even then, the writers probably would have fallen flat – more likely to have copped out by having Smokey put out nothing but fires continually for 17 weeks. (Such a lack of creativity probably was the reason for settling on the “Gunny” format in the first place.) What might have been perhaps never should have.

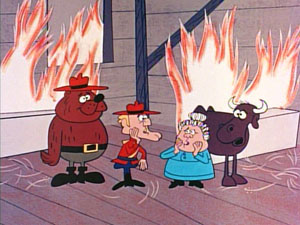

For am appropriate wrap-up to today’s installment, we present a controversial episode which got its producer in a bit of trouble. Without the cooperation of the U.S. Forest Service, renegade animation producer Jay Ward decided to pit Dudley Do-Right against an unexpected adversary – Stokey the Bear (8/4/62). The rich timber-lined forests of Canada are being depleted by a rash of unexplained fires. The cause? A “fire preventing bear” who has been hypnotized by villain Snidely Whiplash into becoming an arsonist! “Why are you doing this, Mr. Whiplash?” asks the narrator. “How else can you barbecue hot dogs?”. responds the foul fiend. Stokey’s wanton destruction of a lumber camp rouses Dudley Do-Right to pick up the trail of the perpetrator. A description of the culprit as “700 pounds, cinnamon color, wearing a mountie hat – and a bear” laves Dudley musing, “Not much to go on.” Nevertheless, Dudley and Horse pick up a trial – that is getting warmer al the time. The closer they get to their quarry, the closer the flames – until the two emerge from the latest inferno considerably blackened and charred. Their search leads to a fire station in Quebec, where Dudley insists that all evidence leads to Sttokey being somewhere “amongst them”. The fire chief assembles his men for inspection, and Dudley takes no more notice of the hulking bear in a fireman’s slicker amongst them except to comment “This fellow didn’t shave today.” A three-alarm signal for help sets the company into action, emerging from the station on an old pumper engine. Regrettably, the fire is in their own firehouse, set by Stokey. While the crew races back to battle the blaze, Stokey shirks his duty, as the only crew member toasting marshmallows. Observant Dudley finally catches on, and a chase results in the bear disappearing up the fire pole, while the blaze grows out of control, forcing the fire crew outside with the rest of the spectators. There, Dudley and the crowd observe on the roof Stokey, surrounded by flames. Mindless of the danger (or perhaps just mindless in general). Dudley races into the burning building, fights his way to the roof, and picks up the dazed bear, with intention to jump off the roof into a firemen’s net. Unfortunately, the crew below gets confused, and picks up a gula goop instead of a net, allowing Dudley and the bear to fall through. Stokey lands safely atop Dudley, who landed squarely on his head (of course, leaving no damage done). An aftermath reveals Inspector Fenwick informing the lumber camp boss that, while he himself was all in favor of locking Stokey in the pokey, Dudley thought that a change of scenery might rehabilitate the bear, and has brought him for a visit to friends of Didley’s in Chicago. The scene dissolves to another inferno, in the form of the historic Chicago fire. In the midst of the blazing buildings stand Didley, Stokey, and the friend which Dudley had brought the bear to visit – Mrs. O’Leary! Dudley mutters conspiratorially to O’Leary that, to protect Stokey’s reputation (and Dudley’s), “We’ll blame it all on the cow!”

For am appropriate wrap-up to today’s installment, we present a controversial episode which got its producer in a bit of trouble. Without the cooperation of the U.S. Forest Service, renegade animation producer Jay Ward decided to pit Dudley Do-Right against an unexpected adversary – Stokey the Bear (8/4/62). The rich timber-lined forests of Canada are being depleted by a rash of unexplained fires. The cause? A “fire preventing bear” who has been hypnotized by villain Snidely Whiplash into becoming an arsonist! “Why are you doing this, Mr. Whiplash?” asks the narrator. “How else can you barbecue hot dogs?”. responds the foul fiend. Stokey’s wanton destruction of a lumber camp rouses Dudley Do-Right to pick up the trail of the perpetrator. A description of the culprit as “700 pounds, cinnamon color, wearing a mountie hat – and a bear” laves Dudley musing, “Not much to go on.” Nevertheless, Dudley and Horse pick up a trial – that is getting warmer al the time. The closer they get to their quarry, the closer the flames – until the two emerge from the latest inferno considerably blackened and charred. Their search leads to a fire station in Quebec, where Dudley insists that all evidence leads to Sttokey being somewhere “amongst them”. The fire chief assembles his men for inspection, and Dudley takes no more notice of the hulking bear in a fireman’s slicker amongst them except to comment “This fellow didn’t shave today.” A three-alarm signal for help sets the company into action, emerging from the station on an old pumper engine. Regrettably, the fire is in their own firehouse, set by Stokey. While the crew races back to battle the blaze, Stokey shirks his duty, as the only crew member toasting marshmallows. Observant Dudley finally catches on, and a chase results in the bear disappearing up the fire pole, while the blaze grows out of control, forcing the fire crew outside with the rest of the spectators. There, Dudley and the crowd observe on the roof Stokey, surrounded by flames. Mindless of the danger (or perhaps just mindless in general). Dudley races into the burning building, fights his way to the roof, and picks up the dazed bear, with intention to jump off the roof into a firemen’s net. Unfortunately, the crew below gets confused, and picks up a gula goop instead of a net, allowing Dudley and the bear to fall through. Stokey lands safely atop Dudley, who landed squarely on his head (of course, leaving no damage done). An aftermath reveals Inspector Fenwick informing the lumber camp boss that, while he himself was all in favor of locking Stokey in the pokey, Dudley thought that a change of scenery might rehabilitate the bear, and has brought him for a visit to friends of Didley’s in Chicago. The scene dissolves to another inferno, in the form of the historic Chicago fire. In the midst of the blazing buildings stand Didley, Stokey, and the friend which Dudley had brought the bear to visit – Mrs. O’Leary! Dudley mutters conspiratorially to O’Leary that, to protect Stokey’s reputation (and Dudley’s), “We’ll blame it all on the cow!”

This episode did not go unnoticed by the Forest Service, who quickly communicated with Ward and the network that the disparagement of Smokey was harmful to his image and to their national campaign against fire carelessness. Out of such pressure (and perhaps the threat of legal retaliation?), the film was pulled from circulation after its initial run, never to be aired again, either on network or local syndication. Thankfully, kudos are in order to Classic Media, for quietly restoring and slipping into one of its complete season boxes of Rocky and Bullwinkle DVD’s this long-lost piece of wicked dark satire. It is also interesting to note that Ward likely only caved-in to demands for the banning of the cartoon because a government agency was involved – anything less, and he might have fought back. He was once reputedly quoted as stating in response to threatened lawsuit by Candid Camera co-host Durwood Kirby (who took umbrage at Ward’s use of the “Kirwood Derby” as a central plot point in a Rocky story arc), “Go ahead, sue me. I can use the publicity.”

This episode did not go unnoticed by the Forest Service, who quickly communicated with Ward and the network that the disparagement of Smokey was harmful to his image and to their national campaign against fire carelessness. Out of such pressure (and perhaps the threat of legal retaliation?), the film was pulled from circulation after its initial run, never to be aired again, either on network or local syndication. Thankfully, kudos are in order to Classic Media, for quietly restoring and slipping into one of its complete season boxes of Rocky and Bullwinkle DVD’s this long-lost piece of wicked dark satire. It is also interesting to note that Ward likely only caved-in to demands for the banning of the cartoon because a government agency was involved – anything less, and he might have fought back. He was once reputedly quoted as stating in response to threatened lawsuit by Candid Camera co-host Durwood Kirby (who took umbrage at Ward’s use of the “Kirwood Derby” as a central plot point in a Rocky story arc), “Go ahead, sue me. I can use the publicity.”

More hot programming from vintage TV, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

I still remember watching the Smokey the Bear Show on tv when I was five or six.

Regarding The Ballad of Smokey the Bear, was the gorilla the same model used for King Kong in R-B’s Mad Monster Party?

Will you be mentioning the fire sequences of Don Bluth’s An American Tail & All Dogs Go To Heaven?

I honestly haven’t followed Bluth’s work that closely, and, although I saw both pictures around the time of their first run, I have no recollection of sequences involving fire. I have never gone back to either picture, and do not own copies. I therefore relinquish any discussion of sequences from these films to your able assistance, should you choose to discuss them here.

Sorry, I’m afraid there are no fire brigades in “Jonny Quest”. Well, there was the memorable episode “Pursuit of the Po-Ho”, in which Dr. Quest and a colleague are taken captive by a primitive tribe whom Race Bannon describes as “savage devils” and “heathen monkeys”, to be sacrificed to their fire god. Race dyes his skin purple with berry juice to disguise himself as the natives’ water god and effect a rescue. But the fire never really gets going.

Carlo Vinci generally animated the dancing scenes in The Flintstones, as he had previously done at Terrytoons for many years.

Another continuity error in “Popeye the Fireman”: the loudspeaker identifies the burning building as the “Hotel Star”, but the sign out front reads “Hotel Ozmond”.

I don’t remember “The Smokey Bear Show” very well, but I remember it fondly. It aired early on Saturday morning and therefore heralded the start of five hours of cartoon fun, until the closing theme of the Bugs Bunny/Roadrunner Show (which to this day makes me feel sad) signaled that it was time to do chores. However, I find the show quite a chore to sit through today.

Speaking of escaped gorillas, are you going to cover “Huck and Ladder” next week? There’s no fire in that one either.

Another error in “Popeye the Fireman” – When the fire engine stops, the ladder should slide forward, not backward.

If memory serves, there was a public service spot where Bullwinkle read a poem about Smokey (represented by a non-cartoon poster) and fire prevention. Wondering if that was before or after Stokey.

the PSA that Jay Ward did for the forestry service was made years after Stokey the Bear was made, according to Keith Scott ‘s book “the Moose that Roared”