As the 50’s continued, visions of aviation in animation remained relatively peaceful – even though we were just concluding our involvement in the Korean War. Such battle never captured the imaginations of the cartoon industry in the way WWII had, and virtually no coverage relating to its events appears to exist. Thus much of the appearance of aircraft behins to shift to commercial aviation, which was becoming increasingly popular, and probably significantly more affordable. Nevertheless, travel by air was still considered adventurous – and by many still considerably dangerous, with periodic reports still coming in from time to time of air disasters and lives lost. Trains and buses were still giving planes a run for their money in attracting the tourist trade, and many a conservative traveler still felt a bit safer knowing the wheels he or she traveled on were firmly settled on the ground. Occasionally, however, animation would remember that planes were still a part of nationwide defense, allowing appearances in the military mode. And the ever-faithful helicopter continued to bring up the rear for short hops into the painted azure blue. Amidst this atmosphere, one of animation’s most conservative fuddy-duddies and a newcomer to the scene wins his wings this week, in an Academy-Award winning excursion, though of course he never knows he’s left the ground – Quincy Magoo. And we’ll visit with Bugs, Daffy, Elmer, Tom, Jerry, and Woody, along with several one-shots from various studios.

As the 50’s continued, visions of aviation in animation remained relatively peaceful – even though we were just concluding our involvement in the Korean War. Such battle never captured the imaginations of the cartoon industry in the way WWII had, and virtually no coverage relating to its events appears to exist. Thus much of the appearance of aircraft behins to shift to commercial aviation, which was becoming increasingly popular, and probably significantly more affordable. Nevertheless, travel by air was still considered adventurous – and by many still considerably dangerous, with periodic reports still coming in from time to time of air disasters and lives lost. Trains and buses were still giving planes a run for their money in attracting the tourist trade, and many a conservative traveler still felt a bit safer knowing the wheels he or she traveled on were firmly settled on the ground. Occasionally, however, animation would remember that planes were still a part of nationwide defense, allowing appearances in the military mode. And the ever-faithful helicopter continued to bring up the rear for short hops into the painted azure blue. Amidst this atmosphere, one of animation’s most conservative fuddy-duddies and a newcomer to the scene wins his wings this week, in an Academy-Award winning excursion, though of course he never knows he’s left the ground – Quincy Magoo. And we’ll visit with Bugs, Daffy, Elmer, Tom, Jerry, and Woody, along with several one-shots from various studios.

Sparky the Firefly (Terrytoons/Fox, Aesop’s Fable, 6/13/53 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – Nighttime in a nearby garden brings out the fireflies to light the evening for the local bugs and frogs. They perform service as traffic signals, street lights, and even in traveling groups that rival scrolling light displays in Times Square reporting the headlines, by grouping into the shape of letters to spell out, “Yanks Win.” However, tragedy strikes on this night, as a small firefly named Sparky, responsible for holding up the period in the sentence, suddenly has his tail light burn out. A firefly without a light is considered useless by the community, and Sparky is ridiculed by his peers as a “dim-bulb.” Alone and friendless, Sparky wanders away, happening upon a local airport. In an interior office, he discovers a bookworm (with the sped-up dialect of a German scientist) “digesting” the information from encyclopedias and books on electronics and light. The firefly musters up enough courage to ask the educated worm if he knows of any solution to his tail-light problem. The worm ingests more information from the electronics book, but finds nothing useful – then hits upon an idea of his own. Crawling over to a human-sized flashlight, the worm unscrews the glass cover, then removes the small bulb from inside the device. He then approaches Sparky, unscrewing the rear end of Sparky’s torso, revealing inside a small light fixture socket – precisely the same diameter as the flashlight bulb. The worm screws in the bulb as a substitute, then braids the firefly’s antennae together to increase the bug’s ampage and voltage. The trick works, and the bulb lights brightly.

Sparky the Firefly (Terrytoons/Fox, Aesop’s Fable, 6/13/53 – Connie Rasinski, dir.) – Nighttime in a nearby garden brings out the fireflies to light the evening for the local bugs and frogs. They perform service as traffic signals, street lights, and even in traveling groups that rival scrolling light displays in Times Square reporting the headlines, by grouping into the shape of letters to spell out, “Yanks Win.” However, tragedy strikes on this night, as a small firefly named Sparky, responsible for holding up the period in the sentence, suddenly has his tail light burn out. A firefly without a light is considered useless by the community, and Sparky is ridiculed by his peers as a “dim-bulb.” Alone and friendless, Sparky wanders away, happening upon a local airport. In an interior office, he discovers a bookworm (with the sped-up dialect of a German scientist) “digesting” the information from encyclopedias and books on electronics and light. The firefly musters up enough courage to ask the educated worm if he knows of any solution to his tail-light problem. The worm ingests more information from the electronics book, but finds nothing useful – then hits upon an idea of his own. Crawling over to a human-sized flashlight, the worm unscrews the glass cover, then removes the small bulb from inside the device. He then approaches Sparky, unscrewing the rear end of Sparky’s torso, revealing inside a small light fixture socket – precisely the same diameter as the flashlight bulb. The worm screws in the bulb as a substitute, then braids the firefly’s antennae together to increase the bug’s ampage and voltage. The trick works, and the bulb lights brightly.

Sparky happily returns to his community. But, although lit again, Sparky finds that his new light source is too bright for the likes of a firefly, causing his neighbors to squint from the glare, and be woken from their slumber by the over-illumination beaming into their windows. They chase Sparky away, insisting he is not a firefly, but a “fake searchlight”. Sparky returns to the airport, as a rainstorm hits the area, hiding in a sheltered corner, and bemoaning that he is still just a nothing. Suddenly, he hears his name being called. It is the bookworm, who informs him that there has been a power outage at the airfield, and a plane flying through the storm is in trouble, as it can’t locate the field. “But what can I do?” asks Sparky. “Dumkoff”, responds the bookworm, reminding Sparky of his one of a kind light. The little firefly struggles to gain alutuide in the rising storm, but inch by inch rises to attempt to intercept the plane. Above, the plane’s windshield wipers work frantically to clear a view for the pilot and co-pilot to locate a place to land, but everything seems to be blackness, obscured by the driving rain and periodic lightning flashes. Suddenly, a small but strong light is observed. “We’re saved! There’s a beacon light. Follow it in”, shouts the captain. Flying ahead, Sparky leads the plane straight to the airfield, where a cheering ground crew rejoice and hail the praises of the insect who saved the day. A ticker tape parade occurs for the little hero (you guessed it – reusing one background from Heckle and Jeckle’s “The Rainmakers”), and Sparky receives a special position of honor. Atop the Empire State Building, a new beacon begins service to provide guidance to all aircraft. A close shot reveals it is Sparky, riding on a tiny tricycle around the perimeter rim of a circular mirror positioned on the tip of the building’s flagpole, his tail flashlight providing a rotating light to all the planes passing the vicinity. The bug happily smiles to the camera, for the fade out.

Sparky happily returns to his community. But, although lit again, Sparky finds that his new light source is too bright for the likes of a firefly, causing his neighbors to squint from the glare, and be woken from their slumber by the over-illumination beaming into their windows. They chase Sparky away, insisting he is not a firefly, but a “fake searchlight”. Sparky returns to the airport, as a rainstorm hits the area, hiding in a sheltered corner, and bemoaning that he is still just a nothing. Suddenly, he hears his name being called. It is the bookworm, who informs him that there has been a power outage at the airfield, and a plane flying through the storm is in trouble, as it can’t locate the field. “But what can I do?” asks Sparky. “Dumkoff”, responds the bookworm, reminding Sparky of his one of a kind light. The little firefly struggles to gain alutuide in the rising storm, but inch by inch rises to attempt to intercept the plane. Above, the plane’s windshield wipers work frantically to clear a view for the pilot and co-pilot to locate a place to land, but everything seems to be blackness, obscured by the driving rain and periodic lightning flashes. Suddenly, a small but strong light is observed. “We’re saved! There’s a beacon light. Follow it in”, shouts the captain. Flying ahead, Sparky leads the plane straight to the airfield, where a cheering ground crew rejoice and hail the praises of the insect who saved the day. A ticker tape parade occurs for the little hero (you guessed it – reusing one background from Heckle and Jeckle’s “The Rainmakers”), and Sparky receives a special position of honor. Atop the Empire State Building, a new beacon begins service to provide guidance to all aircraft. A close shot reveals it is Sparky, riding on a tiny tricycle around the perimeter rim of a circular mirror positioned on the tip of the building’s flagpole, his tail flashlight providing a rotating light to all the planes passing the vicinity. The bug happily smiles to the camera, for the fade out.

The Flying Turtle (Lantz/Universal, Foolish Fable, 6/28/53 – Paul J. Smith, dir.), has been visited twice in this column before. While a good deal of the cartoon deals with manual efforts of its title character to get off the ground, a few mechanical means are employed. One ingenious device which almost works has the turtle wearing a cap from which projects a vertical axle, upon which rests a spool of thread mounted to a propeller pointing upwards. Sort of a motorless version of the professor’s copter cap from Columbia’s “Goofy News Views”. The turtle ties the loose end of the thread to a tree, then takes a running start. As he runs, the thread makes the propeller spin (he must have that axle well lubricated), until enough speed is attained to make him airborne. It gets you up there – but how to stay there with no motor? The gadget runs out of momentum – with the expected result. Now we know why the U.S. Patent Office refuses to issue patents on perpetual motion machines. He also tries the old reliable slingshot from “Goofy’s Glider” – but doesn’t fasten down securely the wooden stick, which comes loose and belts the foolish turtle in the belly.

The Flying Turtle (Lantz/Universal, Foolish Fable, 6/28/53 – Paul J. Smith, dir.), has been visited twice in this column before. While a good deal of the cartoon deals with manual efforts of its title character to get off the ground, a few mechanical means are employed. One ingenious device which almost works has the turtle wearing a cap from which projects a vertical axle, upon which rests a spool of thread mounted to a propeller pointing upwards. Sort of a motorless version of the professor’s copter cap from Columbia’s “Goofy News Views”. The turtle ties the loose end of the thread to a tree, then takes a running start. As he runs, the thread makes the propeller spin (he must have that axle well lubricated), until enough speed is attained to make him airborne. It gets you up there – but how to stay there with no motor? The gadget runs out of momentum – with the expected result. Now we know why the U.S. Patent Office refuses to issue patents on perpetual motion machines. He also tries the old reliable slingshot from “Goofy’s Glider” – but doesn’t fasten down securely the wooden stick, which comes loose and belts the foolish turtle in the belly.

No Barking (Warner, 2/27/54 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.) – An utterly plotless day in the junkyard, with Claude Cat (looking unusually scruffy today – even with five o’clock shadow around his lips) constantly finding himself at cross-purposes with Frisky Puppy, who is out on a typical morning of over-enthusiastically doing nothing. (This sounds like a script idea Jerry Seinfield might have approved.) The film’s entire objective seems to be to find how many ways Claude can be driven to leap upward from Frisky’s surprise barks, usually landing with his claws clamped into a ceiling or other platform upside down, Even this goal for a running gag doesn’t successfully sustain the six minutes of footage, which deviates in the middle for no reason other than time-filling to meaningless sequences of Frisky barking at himself in a mirror reflection and scratching a flea – activities which don’t interact with or affect Claude at all. The two scrounge around for food (or sometimes in Claude’s case, revenge) for the allotted time, Frisky always barking at the slightest provocation. Michael Maltese (who actually dared to take writing credit for this slop) does manage to create a laugh or two with the leap gags. In one instance, Claude receives the barking jolt while following Frisky in an underground sewer. He springs upwards underneath a manhole cover, rising out of the ground clinging to its underside. Having no secure grip on the metal, Claude falls to earth first, the cover following. While Claude flips to land on his feet softly, the cover comes down squarely on top of him, to crush him flat like a Wile E. Coyote boulder. Another leap raises Claude through the gap in the ties of an elevated railway track – just in time to meet the 5:15 head on. In another sequence, Claude is about to climb a tree in search of breakfast from a bird’s nest, when Frisky’s inevitable bark is heard from directly behind him. The force of Claude’s upward leap strips the tree of all leaves into Winter mode, while the nest’s occupant (Tweety Pie in his only cameo in a Golden Age Chuck Jones cartoon), comments, “I taut I taw a putty tat!” Finally, using a stuffed stocking as a fake tail, Claude baits Frisky so that he can sneak up behind the dog and tie a gag around his jaws. Problem solved, Claude thinks – until an even louder set of barks greets him from bulldog Marc Anthony, also in an unexpected cameo. Claude leaps so high, he finds himself clinging to the underside of the wing of a passenger airline, disappearing over the horizon into the sunset. Tweety from his nest again looks up, and replies, “I did. I did taw a putty tat”, for the iris out. Definitely the weakest of all of Frisky’s screen appearances – and one of Jones’ weakest titles since leaving the 1940’s.

No Barking (Warner, 2/27/54 – Charles M. (Chuck) Jones, dir.) – An utterly plotless day in the junkyard, with Claude Cat (looking unusually scruffy today – even with five o’clock shadow around his lips) constantly finding himself at cross-purposes with Frisky Puppy, who is out on a typical morning of over-enthusiastically doing nothing. (This sounds like a script idea Jerry Seinfield might have approved.) The film’s entire objective seems to be to find how many ways Claude can be driven to leap upward from Frisky’s surprise barks, usually landing with his claws clamped into a ceiling or other platform upside down, Even this goal for a running gag doesn’t successfully sustain the six minutes of footage, which deviates in the middle for no reason other than time-filling to meaningless sequences of Frisky barking at himself in a mirror reflection and scratching a flea – activities which don’t interact with or affect Claude at all. The two scrounge around for food (or sometimes in Claude’s case, revenge) for the allotted time, Frisky always barking at the slightest provocation. Michael Maltese (who actually dared to take writing credit for this slop) does manage to create a laugh or two with the leap gags. In one instance, Claude receives the barking jolt while following Frisky in an underground sewer. He springs upwards underneath a manhole cover, rising out of the ground clinging to its underside. Having no secure grip on the metal, Claude falls to earth first, the cover following. While Claude flips to land on his feet softly, the cover comes down squarely on top of him, to crush him flat like a Wile E. Coyote boulder. Another leap raises Claude through the gap in the ties of an elevated railway track – just in time to meet the 5:15 head on. In another sequence, Claude is about to climb a tree in search of breakfast from a bird’s nest, when Frisky’s inevitable bark is heard from directly behind him. The force of Claude’s upward leap strips the tree of all leaves into Winter mode, while the nest’s occupant (Tweety Pie in his only cameo in a Golden Age Chuck Jones cartoon), comments, “I taut I taw a putty tat!” Finally, using a stuffed stocking as a fake tail, Claude baits Frisky so that he can sneak up behind the dog and tie a gag around his jaws. Problem solved, Claude thinks – until an even louder set of barks greets him from bulldog Marc Anthony, also in an unexpected cameo. Claude leaps so high, he finds himself clinging to the underside of the wing of a passenger airline, disappearing over the horizon into the sunset. Tweety from his nest again looks up, and replies, “I did. I did taw a putty tat”, for the iris out. Definitely the weakest of all of Frisky’s screen appearances – and one of Jones’ weakest titles since leaving the 1940’s.

Design For Leaving (Warner, Daffy Duck, 3/26/54 – Robert McKimson, dir.) -McKimson’s clever take on the “house of tomorrow” format previously approached by stablemate Chuck Jones. Terrytoons, and Tex Avery at MGM. However, instead of building from the ground up, salesman Daffy Duck prefers destroying existing structures from the ceiling down, with his line of gadgets from Acme Futuramic Push-Button Home of Tomorrow Household Appliance Company, Inc. Elmer Fudd is his target victim, and the installation process is taken care of by ensuring his extended absence from the home, through routing Fudd onto the wrong bus – one way to Deluth, non-stop. A dump truck quickly delivers all the equipment Daffy will need, so that Elmer will never recognize the place when he returns. The gadgets run the gamut of imagination – a massaging chair that wraps its owner up like a jelly roll, a tie-tier that specializes in hangman’s nooses (the “Alcatraz Ascot”), a knife sharpener that reduces the utensil to a one-inch blade, a wall cleaner that removes wallpaper and then drywall, and an overly sensitive robot fire extinguisher that douses Elmer with buckets of water at the slightest provocation. A master control panel (similar to the button-filled wall in Chuck Jones’ “House Hunting Mice”) controls the action – but Daffy cautions never to press a large, irresistible red button on the corner of the panel. After Daffy demonstrates the “elevator area”, which brings the upstairs downstairs without a staircase, but crushes everything on the first floor, Elmer has had enough, and places his own telephonic order to the Acme company – for their robot futuramic salesman ejector. However, Elmer can’t resist the temptation of pushing the red button once Daffy is gone. A small panel above it reveals the instruction “In case of Tidal Wave”. The entire house rises 200 feet into the air on a telescoping pole. Elmer looks out his front door to find nothing but panoramic view – followed by the sight of Daffy, hovering nearby in a helicopter. Holding out in his hand one additional item, Daffy says, “For a small price, I can install this little blue button to get you down.”

Design For Leaving (Warner, Daffy Duck, 3/26/54 – Robert McKimson, dir.) -McKimson’s clever take on the “house of tomorrow” format previously approached by stablemate Chuck Jones. Terrytoons, and Tex Avery at MGM. However, instead of building from the ground up, salesman Daffy Duck prefers destroying existing structures from the ceiling down, with his line of gadgets from Acme Futuramic Push-Button Home of Tomorrow Household Appliance Company, Inc. Elmer Fudd is his target victim, and the installation process is taken care of by ensuring his extended absence from the home, through routing Fudd onto the wrong bus – one way to Deluth, non-stop. A dump truck quickly delivers all the equipment Daffy will need, so that Elmer will never recognize the place when he returns. The gadgets run the gamut of imagination – a massaging chair that wraps its owner up like a jelly roll, a tie-tier that specializes in hangman’s nooses (the “Alcatraz Ascot”), a knife sharpener that reduces the utensil to a one-inch blade, a wall cleaner that removes wallpaper and then drywall, and an overly sensitive robot fire extinguisher that douses Elmer with buckets of water at the slightest provocation. A master control panel (similar to the button-filled wall in Chuck Jones’ “House Hunting Mice”) controls the action – but Daffy cautions never to press a large, irresistible red button on the corner of the panel. After Daffy demonstrates the “elevator area”, which brings the upstairs downstairs without a staircase, but crushes everything on the first floor, Elmer has had enough, and places his own telephonic order to the Acme company – for their robot futuramic salesman ejector. However, Elmer can’t resist the temptation of pushing the red button once Daffy is gone. A small panel above it reveals the instruction “In case of Tidal Wave”. The entire house rises 200 feet into the air on a telescoping pole. Elmer looks out his front door to find nothing but panoramic view – followed by the sight of Daffy, hovering nearby in a helicopter. Holding out in his hand one additional item, Daffy says, “For a small price, I can install this little blue button to get you down.”

Devil May Hare (Watner, Bugs Bunny, 6/19/54 – Robert McKimson, dir.), receives another honorable mention. The introduction to th screen of the Tasmanian Devil (Taz, for short). The whirlwind bundle of ferocity that eats any living creature in the book of species – and especially Rabbits. Bugs pulls a surprise climax to this first encounter – even he is proud of it. “Oh brother, what I got up my sleeve shouldn’t hap…..”, he asides to the audience, while phoning long distance the Tasmanian Post Dispatch. He places an Object Matrimony” want-ad from “Lonely Tasmanian Devil” in the publication. Within seconds, a twin engine plane from Tasmanian Air Lines makes a landing in a clearing in the woods, and down a passenger stairway whirs a female Tasmanian devil, dressed in bridal veil and carrying a bouquet. It is growl at first sight between the two beasts, who begin to snarl at each other like they’re already married, until Bugs breaks things up for a time out by blowing a football whistle. Bugs appears in the garb of a parson, and, grunting a few words to the couple in Devilese, hears their growling equivalents of “I do,” “I now pronounce you Devil and Devilish”, states Bugs. The happy (?) couple board the plane and fly off into the sunset, Bugs closing with the curtain line, “All the world loves a lover – but in this case, we’ll make an exception.”

Devil May Hare (Watner, Bugs Bunny, 6/19/54 – Robert McKimson, dir.), receives another honorable mention. The introduction to th screen of the Tasmanian Devil (Taz, for short). The whirlwind bundle of ferocity that eats any living creature in the book of species – and especially Rabbits. Bugs pulls a surprise climax to this first encounter – even he is proud of it. “Oh brother, what I got up my sleeve shouldn’t hap…..”, he asides to the audience, while phoning long distance the Tasmanian Post Dispatch. He places an Object Matrimony” want-ad from “Lonely Tasmanian Devil” in the publication. Within seconds, a twin engine plane from Tasmanian Air Lines makes a landing in a clearing in the woods, and down a passenger stairway whirs a female Tasmanian devil, dressed in bridal veil and carrying a bouquet. It is growl at first sight between the two beasts, who begin to snarl at each other like they’re already married, until Bugs breaks things up for a time out by blowing a football whistle. Bugs appears in the garb of a parson, and, grunting a few words to the couple in Devilese, hears their growling equivalents of “I do,” “I now pronounce you Devil and Devilish”, states Bugs. The happy (?) couple board the plane and fly off into the sunset, Bugs closing with the curtain line, “All the world loves a lover – but in this case, we’ll make an exception.”

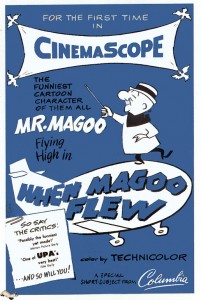

When Magoo Flew (UPA/Columbia, Mister Magoo, 1/6/55 – Pete Burness, dir.) – From the pens of Warner veteran Tedd Pierce and the comparatively unknown Barbara Hammer (not to be confused with film director of the same name) comes this effort that won Magoo his first Academy Award. Soon-to-be Hanna-Barbera mainstay Hoyt Curtin receives credit for the offbeat musical score. Credit sequence for the film is unique, Magoo flying in the credits in tow from an old biplane, rather than peering through the “O”s of his name as glasses as usual.

When Magoo Flew (UPA/Columbia, Mister Magoo, 1/6/55 – Pete Burness, dir.) – From the pens of Warner veteran Tedd Pierce and the comparatively unknown Barbara Hammer (not to be confused with film director of the same name) comes this effort that won Magoo his first Academy Award. Soon-to-be Hanna-Barbera mainstay Hoyt Curtin receives credit for the offbeat musical score. Credit sequence for the film is unique, Magoo flying in the credits in tow from an old biplane, rather than peering through the “O”s of his name as glasses as usual.

Magoo is off on his own for a routine night at the movies (which must be part of his regular regimen, as he doesn’t even know what’s playing). He seems to find the theatre easily enough, but passes right by it without recognizing it. The real item on the marquee is “The Tattle-Tale Heart” starring Theodora Parmalez, in Panoramic screen and Stereophonic sound – “No Glasses Needed”. (This was an in-joke at the studio, ribbing management’s decision to pull from 3-D release their production of James Mason’s “The Tell-Tale Heart”.) Still looking for the theater, Magoo makes the usual mistake of entering the busy terminal building of the local airport. Inside, Magoo somehow interprets a posted ad regarding flying to Hawaii as a lobby poster for a 3-D movie. He walks up to a “your weight and fortune” machine, looking in a mirror at himself, and assumes it is the ticket booth, inserting his cash to receive the fortune stub as his ticket. He joins a line of passengers preparing to board a plane, lining up behind the drummer of a band called “Spook Jones and his Gone Goons”. This allows for him to gain mistaken entry, when he announces to the stewardess “Orchestra, please”, and is permitted to go inside as one of the group.

Magoo settles down in a front row seat near the entrance doors to the passenger cabin. Beside him is a nervous looking moustached man carrying a briefcase, and Magoo attempts to strike up conversation with him. As the cabin lights dim, a sign over the door lights up, reading, ‘Fasten Seat Belts”. Conveniently (for the writers), Magoo is somehow able to read this, and comments, “Funny thing, great run of airplane pictures lately. Never fly myself – – My arms get tired.” He believes the 3-D effect is working, as he claims he can actually feel the plane taking off. On what Magoo presumes to be the “screen”, a trench-coated cop slips in, and converses with the stewardess about looking for “a man”. “Me too”, replies the stewardess, sharing similar life goal. The cop and stewardess describe Magoo’s seating partner to a T, and Magoo assumes the desired culprit to be a bank teller with a briefcase full of stolen Liberty bonds. Meanwhile, the seat next to Magoo is suddenly vacated, only the briefcase being left behind. While Magoo hates to miss any of the picture, he attempts to locate his missing friend, on the chance that the neglected briefcase might contain something important.

Magoo settles down in a front row seat near the entrance doors to the passenger cabin. Beside him is a nervous looking moustached man carrying a briefcase, and Magoo attempts to strike up conversation with him. As the cabin lights dim, a sign over the door lights up, reading, ‘Fasten Seat Belts”. Conveniently (for the writers), Magoo is somehow able to read this, and comments, “Funny thing, great run of airplane pictures lately. Never fly myself – – My arms get tired.” He believes the 3-D effect is working, as he claims he can actually feel the plane taking off. On what Magoo presumes to be the “screen”, a trench-coated cop slips in, and converses with the stewardess about looking for “a man”. “Me too”, replies the stewardess, sharing similar life goal. The cop and stewardess describe Magoo’s seating partner to a T, and Magoo assumes the desired culprit to be a bank teller with a briefcase full of stolen Liberty bonds. Meanwhile, the seat next to Magoo is suddenly vacated, only the briefcase being left behind. While Magoo hates to miss any of the picture, he attempts to locate his missing friend, on the chance that the neglected briefcase might contain something important.

Approaching the emergency exit door, Magoo opens it, believing it to be “elevator to Lobby”. Despite the likelihood of a pressurized cabin, Magoo is not swept outside by the air flow vacuum, but neatly steps into open air for his “elevator”, dropping about four feet onto the surface of the wing. “Watch those sudden stops”, he cautions an operator who isn’t there. Looking around outside, Magoo comments that the lobby is a “big place – and they’ve got their Christmas decorations up already”, looking at the starry night sky. He passes the engine pods, and complains that the theater’s AC is “blowing a gale”. The aileron of one wing pivots upward for a turn, and Magoo trips over it. Believing it to be a loose board, Magoo stomps the metal plate back to flat position, and mutters that someone better nail that down, or there’ll be a lawsuit that’ll close up the whole works. Failing to find his friend here, Magoo decides to try the smoking lounge. He turns toward the plane’s tail, walking along a narrow rim of metal on the side of the fuselage. He looks into one of the cabin windows, where a startled woman shrinks into her seat upon his view. “Oh no, no. Not television”, comments Magoo. “They’ll run it into the ground.” Reaching the tail, Magoo pulls upon the rudder, thinking he is opening the door to the lounge. The plane makes a sudden turn into a circular path, flying through a cloudbsnk, which Magoo mistakes for cigarette smoke. “I seem to be going in circles”, concludes Magoo, deciding to turn the briefcase in at the box office and get back to the picture. Believing himself on the fourth or fifth balcony, he takes a backwards look from the tail at the countryside below him, and comments, “Oh, that wide screen. And no glasses!”

Approaching the emergency exit door, Magoo opens it, believing it to be “elevator to Lobby”. Despite the likelihood of a pressurized cabin, Magoo is not swept outside by the air flow vacuum, but neatly steps into open air for his “elevator”, dropping about four feet onto the surface of the wing. “Watch those sudden stops”, he cautions an operator who isn’t there. Looking around outside, Magoo comments that the lobby is a “big place – and they’ve got their Christmas decorations up already”, looking at the starry night sky. He passes the engine pods, and complains that the theater’s AC is “blowing a gale”. The aileron of one wing pivots upward for a turn, and Magoo trips over it. Believing it to be a loose board, Magoo stomps the metal plate back to flat position, and mutters that someone better nail that down, or there’ll be a lawsuit that’ll close up the whole works. Failing to find his friend here, Magoo decides to try the smoking lounge. He turns toward the plane’s tail, walking along a narrow rim of metal on the side of the fuselage. He looks into one of the cabin windows, where a startled woman shrinks into her seat upon his view. “Oh no, no. Not television”, comments Magoo. “They’ll run it into the ground.” Reaching the tail, Magoo pulls upon the rudder, thinking he is opening the door to the lounge. The plane makes a sudden turn into a circular path, flying through a cloudbsnk, which Magoo mistakes for cigarette smoke. “I seem to be going in circles”, concludes Magoo, deciding to turn the briefcase in at the box office and get back to the picture. Believing himself on the fourth or fifth balcony, he takes a backwards look from the tail at the countryside below him, and comments, “Oh, that wide screen. And no glasses!”

Magoo trots along the top of the plane, headed for the nose. A pilot inside the cockpit, noting the plane’s irregularity in steering, tells his co-pilot, “I’m turning back, Jim. There’s something wrong with the controls.” At that instant, Magoo slides down the cockpit windshield, and hollers unheard complaints at the pilot through the window. The startled pilot takes emergency measures, extending a cargo ramp out from the underside of the plane’s nose to catch Magoo before he falls into oblivion. Inside again, Magoo somehow finds his way back into the passenger cabin, and finds his man, dropping the briefcase into his hands just as he is trying to explain to the cop that he never had a briefcase. Magoo returns to his seat, and watches what must comparatively be an uneventful “picture” for the rest of the flight. The final scene finds the plane back at the airport, with Magoo disembarking. He tells the stewardess, “Splendid program. I enjoyed every thrill-packed minute of it. Only one complaint – No cartoon.” As he walks away, he pauses for an afterthought to the stewardess, inquiring whether they ever show cartoons featuring that “ridiculous nearsighted old man”, then turns, headed in the direction of the boarding ramp of yet another plane, for the fade out.

Magoo trots along the top of the plane, headed for the nose. A pilot inside the cockpit, noting the plane’s irregularity in steering, tells his co-pilot, “I’m turning back, Jim. There’s something wrong with the controls.” At that instant, Magoo slides down the cockpit windshield, and hollers unheard complaints at the pilot through the window. The startled pilot takes emergency measures, extending a cargo ramp out from the underside of the plane’s nose to catch Magoo before he falls into oblivion. Inside again, Magoo somehow finds his way back into the passenger cabin, and finds his man, dropping the briefcase into his hands just as he is trying to explain to the cop that he never had a briefcase. Magoo returns to his seat, and watches what must comparatively be an uneventful “picture” for the rest of the flight. The final scene finds the plane back at the airport, with Magoo disembarking. He tells the stewardess, “Splendid program. I enjoyed every thrill-packed minute of it. Only one complaint – No cartoon.” As he walks away, he pauses for an afterthought to the stewardess, inquiring whether they ever show cartoons featuring that “ridiculous nearsighted old man”, then turns, headed in the direction of the boarding ramp of yet another plane, for the fade out.

Southbound Duckling (MGM, Tom and Jerry, 3/12/55 – William Hanna/Joseph Barbera, dir.) – Little Quacker has a notion in his head to join the migrating ducks on their long winter journey south – despite Jerry showing him a nature guide indicating that domestic ducks do not migrate. The book must be right, as Quacker is entirely out of shape to join up with the flock by physical means – so he turns to a number of artificial ways to soar through the skies. The old reliable Goofy slingshot appears again – but only propels the duck directly into the mouth of hobo cat Tom. A teeterboard and counterweight gets the duck up to the flock, but his limited wing power brings him right back down into Tom’s frying pan. A skyrocket is intercepted by Tom once again, who this time takes the rocket rather than the bird down the throat. A balloon and gondola almost works, until Tom emerges from a haystack with a rifle, in the manner of an anti-aircraft weapon, and shoots the balloon down in flames (or at least a trace of smoke from the duck’s singed tail feathers). Jerry keeps Tom from obtaining dinner by cutting away the bottom of the net Tom holds out to catch Quacker, and the mouse and duck head for the nearest refuge – an airport. They climb into the passenger section of an airliner about to take off. Tom is too late to reach the passenger door, but has no trouble finding one of the plane’s wheels, which bears down upon him on the runway. The plane is conveniently bound for sunny Florida, and, as it makes its approach for a landing, we find one occupant not on the passenger list – Tom, in the wheel well. (I hope his fur coat provided sufficient protection – considering that some people have been known to freeze to death inside a wheel well at high altitude.) Jerry and Quacker set up on the sands for some sunbathing, and wonder what became of the old pussy cat. Their question is answered, as Tom appears from inside a sand dune, slamming down a kiddie sand pail over the rodent and duck, and giving a sinister chuckle to the audience as he hides the scene of revenge behind a beach umbrella, for the fade out.

Southbound Duckling (MGM, Tom and Jerry, 3/12/55 – William Hanna/Joseph Barbera, dir.) – Little Quacker has a notion in his head to join the migrating ducks on their long winter journey south – despite Jerry showing him a nature guide indicating that domestic ducks do not migrate. The book must be right, as Quacker is entirely out of shape to join up with the flock by physical means – so he turns to a number of artificial ways to soar through the skies. The old reliable Goofy slingshot appears again – but only propels the duck directly into the mouth of hobo cat Tom. A teeterboard and counterweight gets the duck up to the flock, but his limited wing power brings him right back down into Tom’s frying pan. A skyrocket is intercepted by Tom once again, who this time takes the rocket rather than the bird down the throat. A balloon and gondola almost works, until Tom emerges from a haystack with a rifle, in the manner of an anti-aircraft weapon, and shoots the balloon down in flames (or at least a trace of smoke from the duck’s singed tail feathers). Jerry keeps Tom from obtaining dinner by cutting away the bottom of the net Tom holds out to catch Quacker, and the mouse and duck head for the nearest refuge – an airport. They climb into the passenger section of an airliner about to take off. Tom is too late to reach the passenger door, but has no trouble finding one of the plane’s wheels, which bears down upon him on the runway. The plane is conveniently bound for sunny Florida, and, as it makes its approach for a landing, we find one occupant not on the passenger list – Tom, in the wheel well. (I hope his fur coat provided sufficient protection – considering that some people have been known to freeze to death inside a wheel well at high altitude.) Jerry and Quacker set up on the sands for some sunbathing, and wonder what became of the old pussy cat. Their question is answered, as Tom appears from inside a sand dune, slamming down a kiddie sand pail over the rodent and duck, and giving a sinister chuckle to the audience as he hides the scene of revenge behind a beach umbrella, for the fade out.

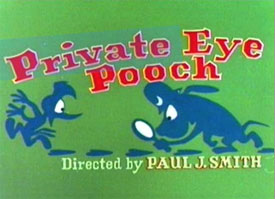

Private Eye Pooch (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 5/9/55 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) receives an honorable mention for one aerial gag – and for being a good cartoon. Paul Smith, a Lantz veteran, had recently been promoted to the director’s chair. Although his draftsmanship was not the best, and despite receiving much criticism for his fallow years during the 1960’s and 1970’s, Smith had a few years of moxie in him at the very beginning, and this is a typical example. Woody is an escapee from lock-up in Phil M. Upp’s School of Taxidermy, where he was intended as the center of study for the lesson of the day. The professor (who would later become better known under the name “Professor Dingledong”) calls out his jail security – a rubbery-featured bloodhound named Strongnose, whose sniff is so powerful, he can suck the feathers right off a photograph of Woody given to him for identification of his subject. Strongnose is ordered to bring in the woodpecker. Woody (who appears in most shots in an unusually round-eyed design Smith had instituted in “Witch Crafty” but would soon abandon) gives the bloodhound a run for his money, using his great inhaling strength against him (by getting him to suck up high voltage wires, bedspring coils that wind him up in spirals, angry alley cats, etc.) He also uses every corny chase gag in the book, including a fake-out in a railway tunnel a la the Road Runner, for a fast-moving chase loaded with quick gag sequences. Though not all qualifying as original, Smith packs in enough material for an average two cartoons from other studios. Strongnose is finally crossed up by pursuing Woody through the raw stock of the Acme Door Company, at the end of which he mistakenly enters the door of a neighboring Ice House. Woody inserts a quarter in the Ice House machine, and Strongnose is dispensed through the self-service doors, with his head encased in a block of ice.

Private Eye Pooch (Lantz/Universal, Woody Woodpecker, 5/9/55 – Paul J. Smith, dir.) receives an honorable mention for one aerial gag – and for being a good cartoon. Paul Smith, a Lantz veteran, had recently been promoted to the director’s chair. Although his draftsmanship was not the best, and despite receiving much criticism for his fallow years during the 1960’s and 1970’s, Smith had a few years of moxie in him at the very beginning, and this is a typical example. Woody is an escapee from lock-up in Phil M. Upp’s School of Taxidermy, where he was intended as the center of study for the lesson of the day. The professor (who would later become better known under the name “Professor Dingledong”) calls out his jail security – a rubbery-featured bloodhound named Strongnose, whose sniff is so powerful, he can suck the feathers right off a photograph of Woody given to him for identification of his subject. Strongnose is ordered to bring in the woodpecker. Woody (who appears in most shots in an unusually round-eyed design Smith had instituted in “Witch Crafty” but would soon abandon) gives the bloodhound a run for his money, using his great inhaling strength against him (by getting him to suck up high voltage wires, bedspring coils that wind him up in spirals, angry alley cats, etc.) He also uses every corny chase gag in the book, including a fake-out in a railway tunnel a la the Road Runner, for a fast-moving chase loaded with quick gag sequences. Though not all qualifying as original, Smith packs in enough material for an average two cartoons from other studios. Strongnose is finally crossed up by pursuing Woody through the raw stock of the Acme Door Company, at the end of which he mistakenly enters the door of a neighboring Ice House. Woody inserts a quarter in the Ice House machine, and Strongnose is dispensed through the self-service doors, with his head encased in a block of ice.

Breaking the cube off with an ice pick, Strongnose finds his schnozzola turning red, as he develops sneezes and a head cold, putting the brakes on his sniffing ability. Woody appears, wearing a fake black nose and two hot water bottles for drooping ears, posing as another bloodhound on the trail. As Strongnose signals the predicament of his dysfunctional sniffer, Woody volunteers to help him locate his prey. Naturally, every lead he gives is false – including flying Strongnose up in the air in a two-seater plane, and convincing him to jump with parachute, which turns out to be only a knapsack loaded with pots and pans. After blasting Strongnose out of a cannon to follow the woodpecker’s trail over a mountain, Strongnose is exhausted by the wily bird, and collapses in a heap. Upon returning to the Taxidermy school, the professor tells him that as a penalty for not catching the woodpecker, they will stuff him instead. “Why that big sew and sew”, replies Woody, listening in at the window, and leaps inside, placing himself in the jaws of Strongnose. “What do you mean, he didn’t catch me? Good dog”, says Woody in the professor’s presence. The professor orders Strongnose to place Woody back in lock-up, but Woody confides in the dog, “I saved your life. Now you save mine.” Strongnose agrees, and, his sniffing power restored, turns on the suction at the professor. The forceful inhale pulls all the clothes off the professor one by one (watch for a single frame where the professor appears butt naked), and he is pulled out of frame, followed by the sound of a cell door slamming, and Woody and Strongnose exiting the jail with the key. But classes must go on, and the students receive Woody as a substitute teacher, who attempts to demonstrate how a woodpecker really should be stuffed – producing a dinner of a roast turkey on a platter. But before he can dig in, the meat is entirely sucked off the turkey’s bones and out of frame. Strongnose has for once made practical use of his skills, and sits before the camera, munching away with an eyebrow raise to the audience, for the iris out.

Breaking the cube off with an ice pick, Strongnose finds his schnozzola turning red, as he develops sneezes and a head cold, putting the brakes on his sniffing ability. Woody appears, wearing a fake black nose and two hot water bottles for drooping ears, posing as another bloodhound on the trail. As Strongnose signals the predicament of his dysfunctional sniffer, Woody volunteers to help him locate his prey. Naturally, every lead he gives is false – including flying Strongnose up in the air in a two-seater plane, and convincing him to jump with parachute, which turns out to be only a knapsack loaded with pots and pans. After blasting Strongnose out of a cannon to follow the woodpecker’s trail over a mountain, Strongnose is exhausted by the wily bird, and collapses in a heap. Upon returning to the Taxidermy school, the professor tells him that as a penalty for not catching the woodpecker, they will stuff him instead. “Why that big sew and sew”, replies Woody, listening in at the window, and leaps inside, placing himself in the jaws of Strongnose. “What do you mean, he didn’t catch me? Good dog”, says Woody in the professor’s presence. The professor orders Strongnose to place Woody back in lock-up, but Woody confides in the dog, “I saved your life. Now you save mine.” Strongnose agrees, and, his sniffing power restored, turns on the suction at the professor. The forceful inhale pulls all the clothes off the professor one by one (watch for a single frame where the professor appears butt naked), and he is pulled out of frame, followed by the sound of a cell door slamming, and Woody and Strongnose exiting the jail with the key. But classes must go on, and the students receive Woody as a substitute teacher, who attempts to demonstrate how a woodpecker really should be stuffed – producing a dinner of a roast turkey on a platter. But before he can dig in, the meat is entirely sucked off the turkey’s bones and out of frame. Strongnose has for once made practical use of his skills, and sits before the camera, munching away with an eyebrow raise to the audience, for the iris out.

(I recall receiving a color sound home movie edition of this film as a Christmas gift during my teens. I was not disappointed.)

Like most of the Lantz cartons… you can only watch this one online by going over to B98.

We’ll take several short hops through the mid-1950’s, next time.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

I knew it was too good to be true. I just watched all three Warner Bros, cartoons on this post successively on Daily Motion — without a single ad! I thought I was dreaming! Usually you have to sit through the same 30-second ad twice before the cartoon even begins. I thought, just maybe, Daily Motion might be going ad-free at last. But no, as soon as I clicked on the Tom and Jerry cartoon, the ads were back — for Tasmanian tourism, of all things.

I happen to think “No Barking” is not only a very funny cartoon, with superb timing and character animation, but quite a profound one as well. Claude’s struggle to control his own destiny, while at the mercy of an instinctive reflex he cannot control, is an existential dilemma with which all living beings can sympathise.

In “Design for Leaving”, Elmer has a print of Picasso’s painting “Still Life with Jug, Candle, and Enamel Pan” on the wall of his house. (Whether Daffy put it there, or Elmer had it all along, is impossible to say.) The original painting is in the National Museum of Modern Art at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, but lithographs of it were pretty popular in the ’50s and ’60s. Presumably background artist Richard H. Thomas either had one or knew someone who did.

Hoyt Curtin really went overboard with the tuba in his score to “When Magoo Flew”, just as he grossly overused the contrabassoon in “Trouble Indemnity”. This is not typical of his later music for Hanna-Barbera; certainly he occasionally wrote solos for tuba, contrabassoon or contrabass saxophone, but they didn’t dominate the soundtrack for six minutes at a time. I wonder if there was some bigshot at UPA who thought that low bass instruments were inherently funny, and he might have exhorted Curtin continually to make use of them.