Well, here we go again. Another round of “virtual” holidays, thanks to the present situation. The kids can’t even line up to sit on Santa’s lap in the department stores, but now have to schedule “Zoom” time for online chats. A recent greeting card depicts Santa finding a sign on a chimney to leave presents on roof, as the house observes social distancing. So strike all plans for communal caroling and big get togethers – we now know how the Grinch stole Christmas – he invented COVID.

It thus appears the only way to vent out frustrations in our unsatisfied need to party hardy is to once again live vicariously through our toons, and let them do the celebrating for us. I thus begin a series on the best of toon festivities through the years, in hopes of rousing your spirits in remembrance of when we too could sometimes cut loose as wildly as they can. (Yes, we know there’s a hidden Tasmanian Devil inside a lot of you out there.) To keep in a jolly mood, we’ll expand the category not just to seasonal parties of all kinds, but big get-togethers in general, including communal dances and those ever-present birthday parties, ensuring that out spirits remain high through the wintery weeks upcoming.

At least for starters, I will not strictly follow my normal chronological approach, as I wish to devote a portion of the first two articles to episodes themed to Christmas and New Years-style celebrations. Then we’ll backtrack in subsequent articles to other festivities we may have passed over. We’ll add a few general hoop-dee-doos together with the seasonal items along the way.

A good example of how early toons expressed their celebrating insyincts is presented by The Shindig (Disney/Columbia, Mickey Mouse, 7/11/30 – Burt Gillett, dir.). Most of the farmyard community is commuting via an outrageously long jitney to a barn dance, including Mickey and Minnie, blowing party horns between their kisses. This title marked the first play-up of the budding romance between series regulars Horace Horsecollar and Clarabelle Cow, with Horace graduating from the plowshare to his own means of transportation – a put-pitting motorcycle and sidecar (actually, a wheelbarrow strapped onto the side). Horace comes a-calling at the residence of Clarabelle, and pulls a “rope” extended out a hole to ring the doorbell. The rope is actually Claravelle’s tail, and the bell that is rung is the one around her neck. For one of the few times in the series excepting her anonymous cameo is “Steamboat Willie”, Clarabelle (excepting her cowbell) is stark naked inside her stall (pre-code udders and all), engrossed in leisure reading of a book titled “Three Weeks” (a 1907 erotic novel written by Elinor Glyn, which had been already filmed twice as a feature by te time of this cartoon’s release, including a Samuel Goldwyn version in 1924 starring Conrad Nagel; the book was considered a scandalous success, and was among works to be “banned in Boston”, making it the recurring subject of off-color jokes). Upon realizing that Horace is outside, Clarabelle quickly hides the book in the hay. (A rare example of adult-themed humor slipping into a Disney cartoon.) For possibly the first time (and one of the few times ever in the original series), Clarabelle receives a line of actual dialogie to speak – “I’ll be right out”, and dons her formal dress (a skirt which covers only her udders) and a flowered hat.

A good example of how early toons expressed their celebrating insyincts is presented by The Shindig (Disney/Columbia, Mickey Mouse, 7/11/30 – Burt Gillett, dir.). Most of the farmyard community is commuting via an outrageously long jitney to a barn dance, including Mickey and Minnie, blowing party horns between their kisses. This title marked the first play-up of the budding romance between series regulars Horace Horsecollar and Clarabelle Cow, with Horace graduating from the plowshare to his own means of transportation – a put-pitting motorcycle and sidecar (actually, a wheelbarrow strapped onto the side). Horace comes a-calling at the residence of Clarabelle, and pulls a “rope” extended out a hole to ring the doorbell. The rope is actually Claravelle’s tail, and the bell that is rung is the one around her neck. For one of the few times in the series excepting her anonymous cameo is “Steamboat Willie”, Clarabelle (excepting her cowbell) is stark naked inside her stall (pre-code udders and all), engrossed in leisure reading of a book titled “Three Weeks” (a 1907 erotic novel written by Elinor Glyn, which had been already filmed twice as a feature by te time of this cartoon’s release, including a Samuel Goldwyn version in 1924 starring Conrad Nagel; the book was considered a scandalous success, and was among works to be “banned in Boston”, making it the recurring subject of off-color jokes). Upon realizing that Horace is outside, Clarabelle quickly hides the book in the hay. (A rare example of adult-themed humor slipping into a Disney cartoon.) For possibly the first time (and one of the few times ever in the original series), Clarabelle receives a line of actual dialogie to speak – “I’ll be right out”, and dons her formal dress (a skirt which covers only her udders) and a flowered hat.

At the dance, a few more pre-code events occur. Mickey and Minnie provide the instrumental entertainment for the room full of dancers, with Minnie on upright piano and Mickey doubling on fiddle and “drums” (an old barrel and milking pail). As Mickey lets loose with a drum roll, he interrupts it with his own “vocal” impression of the same sound – resulting in a pre-coe raspberry. The mice’s rendition of “Turkey in the Straw” (their original signature number from Steamboat Willie) segues into a performance of “Pop Goes the Weasel”. While Clarabelle and Horace become the center of attention with their butt-bumping dancing moves in the center of the crowd, Mickey provides the “Pop” by blowing ip a paper bag and crushing it between his hands. Then mischievous Mickey begins to get overly personal with Minnie, while she remains ansorbed in her piano performance. Mickey grabs hold of her tail, playing it with his violin bow, then stretches it like an elastic band, releasing it to snap back and hit Minnie in her rear end for the second “Pop”. For the next effect, Mickey places Minnie in a position of even firther personal indignity, by grabbing hold of the elastic of Minnie’s panties, stretching them backwards until a good deal of Minnie’s bottom is visible, then releasing them to snap back upon their owner for “Pop” number three. By now, even the gracious Minnie is getting ticked off, and when Mickey tries the panties gag for a second time, she whirls around on her piano stool and gives Mickey a good slap for “Pop” number four, substituting in place of “goes the weasel” her own lyric – “Don’t’cha do that!”

Enough is enough with the “Pops”, as Mickey backs down with a sheepish grin. The musical program now shifts to a tap dancing harmonica rendition by Mickey of Stephen Foster’s “Swanee River”, which medleys into a spirited rendition of “Down Home Rag” (composed by Wilbur Sweatman in 1911). Forgetting her speaking voice, Clarabelle kicks things into high with a vigorous Charleston and side-stepping dance punctuated by loud abrasive “MOOO”s. Mickey joins her, using her tail as a Maypole banner to dance under. Then Mickey selects another dancing partner from the crowd – the adorable Mrs. Dachshund, whose mile-long torso requires Mickey to compress her into curling loops resembling toothpaste coming out of a tube, in a marvelously fluid piece of character animation. As if the last selection of a partner wasn’t a total mismatch, Mickey goes it one better by next choosing a roly-poly female pig over five times his size. When the pig rears back in her dance steps, Mickey is lifted entirely off the ground to rest upon her round belly. While Mickey shouts encouragements of “Whoopee”, the pig launches into what can only be described as the 1930’s equivalent of breakdancing – bouncing up and down on her back upon the old wooden floor of the barn, as if she were a rubber ball, the flooring creaking under her weight. Mickey decides to make the dance more risky, running from side to side underneath the pig between bounces. As the film closes, Mickey trips, falling directly under the pig’s shadow. The pig lands with a crash, and the crowd roars with laughter, as she stands up and turns around, to reveal a flattened grinning Mickey plastered to her back.

Enough is enough with the “Pops”, as Mickey backs down with a sheepish grin. The musical program now shifts to a tap dancing harmonica rendition by Mickey of Stephen Foster’s “Swanee River”, which medleys into a spirited rendition of “Down Home Rag” (composed by Wilbur Sweatman in 1911). Forgetting her speaking voice, Clarabelle kicks things into high with a vigorous Charleston and side-stepping dance punctuated by loud abrasive “MOOO”s. Mickey joins her, using her tail as a Maypole banner to dance under. Then Mickey selects another dancing partner from the crowd – the adorable Mrs. Dachshund, whose mile-long torso requires Mickey to compress her into curling loops resembling toothpaste coming out of a tube, in a marvelously fluid piece of character animation. As if the last selection of a partner wasn’t a total mismatch, Mickey goes it one better by next choosing a roly-poly female pig over five times his size. When the pig rears back in her dance steps, Mickey is lifted entirely off the ground to rest upon her round belly. While Mickey shouts encouragements of “Whoopee”, the pig launches into what can only be described as the 1930’s equivalent of breakdancing – bouncing up and down on her back upon the old wooden floor of the barn, as if she were a rubber ball, the flooring creaking under her weight. Mickey decides to make the dance more risky, running from side to side underneath the pig between bounces. As the film closes, Mickey trips, falling directly under the pig’s shadow. The pig lands with a crash, and the crowd roars with laughter, as she stands up and turns around, to reveal a flattened grinning Mickey plastered to her back.

A sad historical note upon the condition of this fine example of early personality animation is in order. All known prints of this film suffer from several visible artifacts of deterioration, indicating the substantial likelihood that original camera elements for the film have long since deteriorated or passed beyond condition of repair. Several scenes appear to be cobbled together from multiple copies, changing contrast and focus markedly within mid-shot. Some odd black patches appear in the lower corers of some of the scenes of the jitney and of Horace and Clarabelle in the motorcycle, which seem to be signs of the original camera mounting or cel-locator pins that the cameramen presumed would be out of frame when the film was processed (if only someone had informed the lab to do so). The most jarring problem, however, is indication in one introductory shot and throughout the last third of the cartoon that the original source material has shrunken considerably in size from nitrate deterioration. (A problem which I once witnessed firsthand at UCLA film archive, as a Moviola screening of an otherwise pristine nitrate print of Flip the Frog’s The Cuckoo Murder Case was barely able to make its rattling way through the gears of the machine because of the sprocket holes being slightly closer to one another than regulation.) The visual result is that frames of the film do not fill up the whole of the screen height, and the lower edge of the frame outline creeps gradually upwards into the shot, until the whole image has to be manually repositioned downwards one notch by the processing lab to prevent the picture from completely leaving the screen. This shifting-picture solution appears to have been employed right from the first reissue of the cartoon with the old “burlap-style” credits (which credits are currently replaced with an inaccurate “recreation” of the Columbia titles, incorrectly using a full-frame Mickey head before the title, a background in too light a grey-tone, and a fade-out of the background before allowing the title to disappear, when in the original the entire image faded at once – this information thanks to the extensive research of David Gerstein in his “Ramapith” website article, Mouse, Interrupted, and the original titling formerly available in such article still viewable as a still on Google images.) Despite “remastering” the film for the Walt Disney Treasures DVD release, all the old artifacts of the earlier preservation transfer still remain, and may apparently continue for the remaining shelf-life of the film, ranking it as one of the most poorly preserved in the Disney vault. We can only wonder if enough of the print from which David Gerstein rescued the original title remains transferrable so as to account for any of the shrunken scenes without the frame-creep problem. (Don’t hold your breath – even David was never able to offer any projected clips from this print, which also I believe was only in 16mm.)

A sad historical note upon the condition of this fine example of early personality animation is in order. All known prints of this film suffer from several visible artifacts of deterioration, indicating the substantial likelihood that original camera elements for the film have long since deteriorated or passed beyond condition of repair. Several scenes appear to be cobbled together from multiple copies, changing contrast and focus markedly within mid-shot. Some odd black patches appear in the lower corers of some of the scenes of the jitney and of Horace and Clarabelle in the motorcycle, which seem to be signs of the original camera mounting or cel-locator pins that the cameramen presumed would be out of frame when the film was processed (if only someone had informed the lab to do so). The most jarring problem, however, is indication in one introductory shot and throughout the last third of the cartoon that the original source material has shrunken considerably in size from nitrate deterioration. (A problem which I once witnessed firsthand at UCLA film archive, as a Moviola screening of an otherwise pristine nitrate print of Flip the Frog’s The Cuckoo Murder Case was barely able to make its rattling way through the gears of the machine because of the sprocket holes being slightly closer to one another than regulation.) The visual result is that frames of the film do not fill up the whole of the screen height, and the lower edge of the frame outline creeps gradually upwards into the shot, until the whole image has to be manually repositioned downwards one notch by the processing lab to prevent the picture from completely leaving the screen. This shifting-picture solution appears to have been employed right from the first reissue of the cartoon with the old “burlap-style” credits (which credits are currently replaced with an inaccurate “recreation” of the Columbia titles, incorrectly using a full-frame Mickey head before the title, a background in too light a grey-tone, and a fade-out of the background before allowing the title to disappear, when in the original the entire image faded at once – this information thanks to the extensive research of David Gerstein in his “Ramapith” website article, Mouse, Interrupted, and the original titling formerly available in such article still viewable as a still on Google images.) Despite “remastering” the film for the Walt Disney Treasures DVD release, all the old artifacts of the earlier preservation transfer still remain, and may apparently continue for the remaining shelf-life of the film, ranking it as one of the most poorly preserved in the Disney vault. We can only wonder if enough of the print from which David Gerstein rescued the original title remains transferrable so as to account for any of the shrunken scenes without the frame-creep problem. (Don’t hold your breath – even David was never able to offer any projected clips from this print, which also I believe was only in 16mm.)

An early (and comparatively rare) example of cartoon celebration from the opposite coast’s production is My Wife’s Gone to the Country (Fleischer/Paramount. Screen Song, (5/31/31 (credits lost)), based on a 1909 composition by George Whiting and Irving Berlin. True to the title, the opening scenes depict a hefty behemoth of a housewife packing her suitcases for the titular vacation trip (blushing as she hides her “unmentioables” from the view of the camera). A multitude of kids are also packing everything in sight into suitcases. One is seen taking individual goldfish from a bowl, wrapping them in fish market paper, and tossing them into a satchel. Another lifts an entire upright piano and compresses it into a larger suitcase. Papa encourages them all to hurry or they’ll miss their train. At the depot, Pop helps them all aboard, fondly kissing wifey goodbye, then pushing into the railroad car passenger door the abundance of suitcases (which a reverse camera angle reveals are merely falling out the passenger door on the opposite side of the car and tumbling onto the tracks). The train pulls away, and Papa continues waving until he is sure they’re out of hearing range – then starts whooping and shouting “Hooray” that Mom and the kids have left him free to do as he pleases. He begins his exercises in liberation by serenading himself on the piano at home with the title number – then takes his act on the road to a fancy night club, where he continues to perform his piano specialty on stage for the crowd, while a barrage of party balloons engulfs the screen. The title number , as well as a specialty lyric upon “Smile, Darn Ya, Smile” (performed as “Sing, Darn Ya, Sing” over the credits) feature vocal performance by novelty recording king Billy Murray. After the sing-along, we see Papa celebrating in the streets, shouting “Hot Times”, amidst flashing neon signs of Wine, Women, Song, and Kosher for Passover. We return to the night club, where the balloons are still floating, confetti is flying, drinks are being served, and Papa is getting more inebriated by the minute, and is now hob-nobbing with, of all people, showgirl Betty Boop. Pop hops onto the stage where a band and dancing girls are performing, and repeats his song to a radio microphone hookup. In the country, the “little” Missus sits on a porch, enjoying the radio broadcast on an old set equipped with large amplifying horn. Hearing her husband’s voice, and his demeaning lyrics regarding her and the kids, she responds, “Oh, yeah?”, and reaches her arms into the radio horn. Back in the night club, her hands emerge from the broadcast microphine, one grabbing hubby by the scruff of the neck, while the other produces a rolling pin and knocks the tar out of hubby’s cranium for a star-shaped blackout.

An early (and comparatively rare) example of cartoon celebration from the opposite coast’s production is My Wife’s Gone to the Country (Fleischer/Paramount. Screen Song, (5/31/31 (credits lost)), based on a 1909 composition by George Whiting and Irving Berlin. True to the title, the opening scenes depict a hefty behemoth of a housewife packing her suitcases for the titular vacation trip (blushing as she hides her “unmentioables” from the view of the camera). A multitude of kids are also packing everything in sight into suitcases. One is seen taking individual goldfish from a bowl, wrapping them in fish market paper, and tossing them into a satchel. Another lifts an entire upright piano and compresses it into a larger suitcase. Papa encourages them all to hurry or they’ll miss their train. At the depot, Pop helps them all aboard, fondly kissing wifey goodbye, then pushing into the railroad car passenger door the abundance of suitcases (which a reverse camera angle reveals are merely falling out the passenger door on the opposite side of the car and tumbling onto the tracks). The train pulls away, and Papa continues waving until he is sure they’re out of hearing range – then starts whooping and shouting “Hooray” that Mom and the kids have left him free to do as he pleases. He begins his exercises in liberation by serenading himself on the piano at home with the title number – then takes his act on the road to a fancy night club, where he continues to perform his piano specialty on stage for the crowd, while a barrage of party balloons engulfs the screen. The title number , as well as a specialty lyric upon “Smile, Darn Ya, Smile” (performed as “Sing, Darn Ya, Sing” over the credits) feature vocal performance by novelty recording king Billy Murray. After the sing-along, we see Papa celebrating in the streets, shouting “Hot Times”, amidst flashing neon signs of Wine, Women, Song, and Kosher for Passover. We return to the night club, where the balloons are still floating, confetti is flying, drinks are being served, and Papa is getting more inebriated by the minute, and is now hob-nobbing with, of all people, showgirl Betty Boop. Pop hops onto the stage where a band and dancing girls are performing, and repeats his song to a radio microphone hookup. In the country, the “little” Missus sits on a porch, enjoying the radio broadcast on an old set equipped with large amplifying horn. Hearing her husband’s voice, and his demeaning lyrics regarding her and the kids, she responds, “Oh, yeah?”, and reaches her arms into the radio horn. Back in the night club, her hands emerge from the broadcast microphine, one grabbing hubby by the scruff of the neck, while the other produces a rolling pin and knocks the tar out of hubby’s cranium for a star-shaped blackout.

The Birthday Party (Disney/Columbia, Mickey Mouse, 1/6/31, Burt Gillett, dir.) – Instead of Mickey throwing a bash, this time it’s his friends planning a bash for him – as a surprise at Minnie’s house. Horace Horsecollar and Clarabelle Cow (the latter of whom appears to be drawn in multiple times within the same shots – does she have twin siblings?), along with other anonymous barnyard residents, wait inside Minnie’s living room for Mickey to arrive for what he thinks is a routine date. As Mickey rings the doorbell, the guests do their best to hide behind the furniture – excepting a pig too big to hide, over whom Minnie tosses a tableclith and sets a vase of flowers on top, and a small kitten, who Minnie dumps hurriedly into a receptacle for canes and umbrellas. As the door opens, Mickey says hello, and asks Minnie “How are you?”. Minnie replies, “I’m fine, how are you?” The same response gets batted back and fourth between them about three times, until Mickey sums up by saying, “We’re both fine.” Then out pop the guests with “Surprise!” A pig chef pops out of the kitchen with a triple layer birthday came with two lighted candles (Mickey looks pretty mature for his tender age in years). The pig tells Mickey to give just one little blow to put out the candles. Mickey instead lets loose with a blow predicting the Big Bad Wolf, which blows apart and covers the chef in birthday cake, while leaving the candles still aglow. A large package is revealed, which Mickey opens to disclose an upright piano, only slightly smaller than Minnie’s. In the style of various duo-piano acts of the day (most notable of the time being Victor Arden and Phil Ohman on Victor records), Mickey and Minnie perform the current hit, “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love” with vocal duet, then shift to an instrumental performance of “The Darktown Strutters’ Ball”. The dancers dance in abandon, including two kittens who fall into a goldfish bowl, the goldfish replacing them as dancers atop the bowl’s rim. Look for a rare animation error at 3:24, as a background begins out of allignment in a shot of Mickey and Minne dancing – then has to be shifted halfway across the screen’s width for the panning action of the remaining shot to properly coordinate with the dimensions of the room. So who’s providing the piano music while they dance? The piano stools, of course. Horace ad Clarabelle perform a cakewalk, although Horace’s hat ends up in a spittoon. Mickey performs a xylophone solo (since this wasn’t shown as one of the presents, I guess Minnie just happens to keep one around.) He performs various tricks, including a move that flips all the xylophone bars on their side, then blows on them to knock them back into position like a row of dominoes. The xylophone develops a mind of its own, and begins to shift out of range of Mickey’s mallets, essentially playing itself, then doubling up with musical “laughter” when Mickey can’t catch it. Finally, the instrument takes on the characteristics of a bucking bronco, galloping Mickey all over the room, and throwing him to the ground, where a loose floorboard flips the goldfish bowl upside down atop Mickey’s head. Mickey, with his head submerged in the bowl’s water, gives the camera a sheepish grin for the iris out.

The Birthday Party (Disney/Columbia, Mickey Mouse, 1/6/31, Burt Gillett, dir.) – Instead of Mickey throwing a bash, this time it’s his friends planning a bash for him – as a surprise at Minnie’s house. Horace Horsecollar and Clarabelle Cow (the latter of whom appears to be drawn in multiple times within the same shots – does she have twin siblings?), along with other anonymous barnyard residents, wait inside Minnie’s living room for Mickey to arrive for what he thinks is a routine date. As Mickey rings the doorbell, the guests do their best to hide behind the furniture – excepting a pig too big to hide, over whom Minnie tosses a tableclith and sets a vase of flowers on top, and a small kitten, who Minnie dumps hurriedly into a receptacle for canes and umbrellas. As the door opens, Mickey says hello, and asks Minnie “How are you?”. Minnie replies, “I’m fine, how are you?” The same response gets batted back and fourth between them about three times, until Mickey sums up by saying, “We’re both fine.” Then out pop the guests with “Surprise!” A pig chef pops out of the kitchen with a triple layer birthday came with two lighted candles (Mickey looks pretty mature for his tender age in years). The pig tells Mickey to give just one little blow to put out the candles. Mickey instead lets loose with a blow predicting the Big Bad Wolf, which blows apart and covers the chef in birthday cake, while leaving the candles still aglow. A large package is revealed, which Mickey opens to disclose an upright piano, only slightly smaller than Minnie’s. In the style of various duo-piano acts of the day (most notable of the time being Victor Arden and Phil Ohman on Victor records), Mickey and Minnie perform the current hit, “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love” with vocal duet, then shift to an instrumental performance of “The Darktown Strutters’ Ball”. The dancers dance in abandon, including two kittens who fall into a goldfish bowl, the goldfish replacing them as dancers atop the bowl’s rim. Look for a rare animation error at 3:24, as a background begins out of allignment in a shot of Mickey and Minne dancing – then has to be shifted halfway across the screen’s width for the panning action of the remaining shot to properly coordinate with the dimensions of the room. So who’s providing the piano music while they dance? The piano stools, of course. Horace ad Clarabelle perform a cakewalk, although Horace’s hat ends up in a spittoon. Mickey performs a xylophone solo (since this wasn’t shown as one of the presents, I guess Minnie just happens to keep one around.) He performs various tricks, including a move that flips all the xylophone bars on their side, then blows on them to knock them back into position like a row of dominoes. The xylophone develops a mind of its own, and begins to shift out of range of Mickey’s mallets, essentially playing itself, then doubling up with musical “laughter” when Mickey can’t catch it. Finally, the instrument takes on the characteristics of a bucking bronco, galloping Mickey all over the room, and throwing him to the ground, where a loose floorboard flips the goldfish bowl upside down atop Mickey’s head. Mickey, with his head submerged in the bowl’s water, gives the camera a sheepish grin for the iris out.

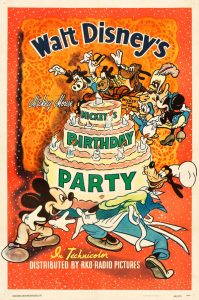

For interesting comparison, fast forward about a decade, to Mickey’s Birthday Party (Disney/RKO, 2/7/42 – Riley Thompson, dir.). This was the time when Disney began to produce a few Technicolor remakes or reworkings of black-and-white classics, such as the shot-for-shot redo of “The Orphan’s Benefit”, or the slightly more subtle reworking of “Mickey’s Pal Pluto” into “Lend a Paw”. Although I for one didn’t tend to think of this film as a remake, a closer examination reveals that at least the cartoon’s opening tracks the 1931 version pretty closely. The portly pig who’s too big too hide is replaced by Clara Cluck, who is concealed by a tablecloth, with the extra touch of Donald putting on a lampsgade and posing as a lamp atop her. Mickey’s entrance is updated from the “We’re both fine” routine to a slightly more aggressive effort to steal a kiss from Minnie, before the “Surprise” is popped. Instead of the twin pianos, Mickey is presented with an electric organ (a fairly new instrument at the time, the sound of which Disney had been experimenting with in his shorts for a couple of seasons since about 1940). Because only one of them can play at a time, Mickey substitutes for his musical performance a wild impromptu dance (a favorite sequence of the studio, frequently used in clip montages and in a repeating cycle for end titling on the old “The Mouse Factory” program. A portion of the dance seems to take a leaf from 1936’s “Thru the Mirror”, with Mickey converting his walking cane into a dancing partner, much in the same way as he utilized a matchstick in the earlier production. The principal differences in the film, however, result from an updating of the remaining musical program to interpolate new dance and rhythm crazes of the day, and replacement of the short appearance of the pig chef with a creative and extensive running gag for Goofy that largely provides the reason for being for this episode. (Voice crediting for the Goof is still not correctly indicated on IMDB, as this should have been the period during which Pinto Colvig was with Fleischer in Florida. Does anyone know whom the quite competent substitute “Goof” was who voiced this cartoon and “Goofy’s Glider”, “Baggage Buster”, and possibly “Tugboat Mickey” and/or “Billposters”? He always sounds just a tiny bit deeper in register than Pinto.)

For interesting comparison, fast forward about a decade, to Mickey’s Birthday Party (Disney/RKO, 2/7/42 – Riley Thompson, dir.). This was the time when Disney began to produce a few Technicolor remakes or reworkings of black-and-white classics, such as the shot-for-shot redo of “The Orphan’s Benefit”, or the slightly more subtle reworking of “Mickey’s Pal Pluto” into “Lend a Paw”. Although I for one didn’t tend to think of this film as a remake, a closer examination reveals that at least the cartoon’s opening tracks the 1931 version pretty closely. The portly pig who’s too big too hide is replaced by Clara Cluck, who is concealed by a tablecloth, with the extra touch of Donald putting on a lampsgade and posing as a lamp atop her. Mickey’s entrance is updated from the “We’re both fine” routine to a slightly more aggressive effort to steal a kiss from Minnie, before the “Surprise” is popped. Instead of the twin pianos, Mickey is presented with an electric organ (a fairly new instrument at the time, the sound of which Disney had been experimenting with in his shorts for a couple of seasons since about 1940). Because only one of them can play at a time, Mickey substitutes for his musical performance a wild impromptu dance (a favorite sequence of the studio, frequently used in clip montages and in a repeating cycle for end titling on the old “The Mouse Factory” program. A portion of the dance seems to take a leaf from 1936’s “Thru the Mirror”, with Mickey converting his walking cane into a dancing partner, much in the same way as he utilized a matchstick in the earlier production. The principal differences in the film, however, result from an updating of the remaining musical program to interpolate new dance and rhythm crazes of the day, and replacement of the short appearance of the pig chef with a creative and extensive running gag for Goofy that largely provides the reason for being for this episode. (Voice crediting for the Goof is still not correctly indicated on IMDB, as this should have been the period during which Pinto Colvig was with Fleischer in Florida. Does anyone know whom the quite competent substitute “Goof” was who voiced this cartoon and “Goofy’s Glider”, “Baggage Buster”, and possibly “Tugboat Mickey” and/or “Billposters”? He always sounds just a tiny bit deeper in register than Pinto.)

While Clara Cluck and Donald experiment in a medium far departing from their usual opera – contemporary Latin-America conga rhythms (a move predating Disney’s “good neighbor policy” features, though no doubt such projects were already in the works behind the scenes), Goofy sets himself the task of creating a cake worthy of the mouse. In the living room, Donald cavorts in sombrero and with a pair of maracas, while Clara vocally induces the gang into a conga line, and performs some violent dance steps that prove too much for Donald, who is tossed about all over the room. Goofy fills time in the kitchen by dancing with an old mop for a partner, then tests his multi-layer cake fresh out of the oven by poking into it to see if done. It deflates like a punctured ball into a pancake. Goofy mixes a new batter of “quick rise” variety, which sprouts extra layers automatically as it is heated inside the oven. The Goof attempts to tiptoe away from the stove so as not to disturb his creation, but instead trips and pratfalls onto the floor. The impact has the same effect as if the cake were a souffle – the bottom falls out, literally, making a visible dent in the bottom of the stove as it falls. Goofy attempts to retrieve the mess from the stove, but the weighty batter is so anxious to touch mother Earth that it bursts out the bottom of the cake pan, blasting a deep hole into the kitchen floor. Time is running out, so Goofy shifts gears into high, whipping up a third batter at lightning speed. Then, to accelerate the cooking process, Goofy turns the stove setting from Very Hot to Awful Hot to Volcano Heat. After counting off only a handful of seconds, Goofy looks into the stove. No false advertising on that heat meter – the cake is literally erupting from the pan! Everything else having failed, and the kitchen now looking like a war zone, Goof hits upon an idea, illustrated with a light bulb above his head (which he clicks off before leaving the house – a similar gag would later appear in a Jack Hannah Chip and Dale cartoon). Dashing out the door, Goof finally reappears, with a store-bought cake from the Jiffy Bakery. Minnie covers Mickey’s eyes, as the lights are dimmed, and Goofy carries the cake into the living room, through a pair of swinging doors. Of course, the doors swing closed upon Goofy’s back, jostling his grip on the cake tray. With a crash, and the return of the lights, we find Mickey, wearing his birthday cake instead of eating it, but still cheerfully happy at the wonderful time that he’s had.

While Clara Cluck and Donald experiment in a medium far departing from their usual opera – contemporary Latin-America conga rhythms (a move predating Disney’s “good neighbor policy” features, though no doubt such projects were already in the works behind the scenes), Goofy sets himself the task of creating a cake worthy of the mouse. In the living room, Donald cavorts in sombrero and with a pair of maracas, while Clara vocally induces the gang into a conga line, and performs some violent dance steps that prove too much for Donald, who is tossed about all over the room. Goofy fills time in the kitchen by dancing with an old mop for a partner, then tests his multi-layer cake fresh out of the oven by poking into it to see if done. It deflates like a punctured ball into a pancake. Goofy mixes a new batter of “quick rise” variety, which sprouts extra layers automatically as it is heated inside the oven. The Goof attempts to tiptoe away from the stove so as not to disturb his creation, but instead trips and pratfalls onto the floor. The impact has the same effect as if the cake were a souffle – the bottom falls out, literally, making a visible dent in the bottom of the stove as it falls. Goofy attempts to retrieve the mess from the stove, but the weighty batter is so anxious to touch mother Earth that it bursts out the bottom of the cake pan, blasting a deep hole into the kitchen floor. Time is running out, so Goofy shifts gears into high, whipping up a third batter at lightning speed. Then, to accelerate the cooking process, Goofy turns the stove setting from Very Hot to Awful Hot to Volcano Heat. After counting off only a handful of seconds, Goofy looks into the stove. No false advertising on that heat meter – the cake is literally erupting from the pan! Everything else having failed, and the kitchen now looking like a war zone, Goof hits upon an idea, illustrated with a light bulb above his head (which he clicks off before leaving the house – a similar gag would later appear in a Jack Hannah Chip and Dale cartoon). Dashing out the door, Goof finally reappears, with a store-bought cake from the Jiffy Bakery. Minnie covers Mickey’s eyes, as the lights are dimmed, and Goofy carries the cake into the living room, through a pair of swinging doors. Of course, the doors swing closed upon Goofy’s back, jostling his grip on the cake tray. With a crash, and the return of the lights, we find Mickey, wearing his birthday cake instead of eating it, but still cheerfully happy at the wonderful time that he’s had.

Scrappy’s Party (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Scrappy, 2/13/33 – Dick Huemer, dir.) provides the animators of the Charles Mintz studio a chance to really show off their talent for caricatures, featuring celebrity cameos from a veritable who’s who of real world personalities. (I believe the studio’s frst such outing was Krazy Kat’s 1932-33 season opener, Seeing Stars. After this episode, the studio got into a brief rut of parading the same personalities again and again in several episodes. Does anyone know the identity of the specific caricaturists who were behind this work for the Mintz studio?)

Scrappy’s Party (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Scrappy, 2/13/33 – Dick Huemer, dir.) provides the animators of the Charles Mintz studio a chance to really show off their talent for caricatures, featuring celebrity cameos from a veritable who’s who of real world personalities. (I believe the studio’s frst such outing was Krazy Kat’s 1932-33 season opener, Seeing Stars. After this episode, the studio got into a brief rut of parading the same personalities again and again in several episodes. Does anyone know the identity of the specific caricaturists who were behind this work for the Mintz studio?)

The film opens with Oopie decorating a large birthday cake for Scrappy, then awakening him for the big day. Scrappy instantly has the idea, “Let’s have a party”. For the next minute, various shots are seen of Scrappy hanging up streamers and balloons on the walls, and chopping up food for a banquet (including telling a turkey in the oven to flip over under its own power), while Oopie tap dances along a room-long banquet table distributing place settings, silverware and drinks. The cake is set in place, and Scrappy curiously blows out the candles before the guests have arrived (mainly to fill out the last five beats of the lively Joe De Nat musical score, and also tipping off by their number Scrappy’s presumed age). Now comes the matter of a guest list. Who needs lists? Just think of a famous person, and call hm up on the phone. (Scrappy’s so important himself, he is obviously of the opinion that no advance invitations are necessary, as everyone will drop hatever they’re doing and show up for him on a moment’s notice). Some do exactly that, such as Jimmy Durante, who happens to have Marie Dressler on his lap, and drops her like a ton of bricks upon recieving the invite. The four Marx Brothers are all caught in the shower together, and head for the party sharing one communal bath towel. Greta Garbo for once does not “want to be alone” and also accepts the invitation. Other invitees include big-mouth Joe E. Brown, whistling stutterer Lloyd Hamilton, Laurel and Hardy, George Bernard Shaw, a scientist (IMDB believes it is Auguste Piccard of stratospheric flight fame, but I believe it looks more like Albert Einstein, who was visiting the United States at the time and would ultimately stay permanently), Mahatma Gandhi, Benito Mussolini, King George V, deposed King Alphonso XII, an unidentified cowboy (Tom Mix?). Will Rogers and his lariat, Babe Ruth (who uses his “King of Swat” talents to bash balloons like they were piñatas), and John D. Rockefeller, who tosses coins everywhere. Only one person (who we didn’t even see Scrappy call, but who calls him instead) apologizes that he is unable to come – Al Capone in jail. A wild and festive bash is had be all, dancing in wild abandon to Scrappy’s piano rendition of “Tiger Rag”. The party breaks up at 3:00 a.m. (at the calling of a cuckoo-clock bird who curiously has the head of Uncle Sam). Scrappy and Oopie wave a fond farewell to an endless stream of guests clogging the roadways home, as the cartoon irises out.

And now for a seasonal trio. The Academy Award nominated Mickey’s Orphans (Disney/Columbia, Mickey Mouse, 12/9/31 – Burt Gillett, dir.) finds Mickey festive once again, but this time with more specific purposwe. A basket of baby kittens has been left on his doorstep by a mysterious hooded stranger, who spirits herself away after ringing the doorbell. Inside, Minnie pumps an old organ, playing and singing “Silent Night”, while Mickey deftly tosses Christmas tree ornaments two at a time into perfect position on the tree, then plays the fragile glass ornaments with candy canes as if playing a xylophone. Also present is Pluto, snoring by the fireplace. At the sound of the doorbell. Pluto charges to the door, but finds no one there except the basket, which he brings inside. Out from under the covering blanket pops a cute kitten in diapers. Mickey brings the kitten over to Minnie, who pays “coochi-coochi” with it, while all Mickey gets from trying to join in the game is a nip on the finger. Pluto is the only one who notices that the contents of the basket aren’t finished, and pulls away the blanket – to reveal the entire basket is filled to overflowing with additional kittens. (No wonder Mom couldn’t afford to keep them. Only a mouse with a movie-star budget could manage it.) The place is suddenly overrun with cats, in a manner that only the artists and budget of Disney could then afford to present. Kittens swing from a clock pendulum and land on the keys of a piano. (Told you Mickey was rich – how many households could afford both a grand piano and a pump organ?) Kittens engage in alternating pulls upon the ears of Pluto, using him as a teeter-totter. One kitten dispossess a polly parrot from his cage, to play on the parrot’s swing. Four more use the light globes of a ceiling chandelier to ride in like a rotating merry-go-round. (This same gag would be lifted by Terrytoons for the following year’s Toyland.) In a group shot, another kitten rides on a Victrola turntable, while one of his siblings turns the crank.

And now for a seasonal trio. The Academy Award nominated Mickey’s Orphans (Disney/Columbia, Mickey Mouse, 12/9/31 – Burt Gillett, dir.) finds Mickey festive once again, but this time with more specific purposwe. A basket of baby kittens has been left on his doorstep by a mysterious hooded stranger, who spirits herself away after ringing the doorbell. Inside, Minnie pumps an old organ, playing and singing “Silent Night”, while Mickey deftly tosses Christmas tree ornaments two at a time into perfect position on the tree, then plays the fragile glass ornaments with candy canes as if playing a xylophone. Also present is Pluto, snoring by the fireplace. At the sound of the doorbell. Pluto charges to the door, but finds no one there except the basket, which he brings inside. Out from under the covering blanket pops a cute kitten in diapers. Mickey brings the kitten over to Minnie, who pays “coochi-coochi” with it, while all Mickey gets from trying to join in the game is a nip on the finger. Pluto is the only one who notices that the contents of the basket aren’t finished, and pulls away the blanket – to reveal the entire basket is filled to overflowing with additional kittens. (No wonder Mom couldn’t afford to keep them. Only a mouse with a movie-star budget could manage it.) The place is suddenly overrun with cats, in a manner that only the artists and budget of Disney could then afford to present. Kittens swing from a clock pendulum and land on the keys of a piano. (Told you Mickey was rich – how many households could afford both a grand piano and a pump organ?) Kittens engage in alternating pulls upon the ears of Pluto, using him as a teeter-totter. One kitten dispossess a polly parrot from his cage, to play on the parrot’s swing. Four more use the light globes of a ceiling chandelier to ride in like a rotating merry-go-round. (This same gag would be lifted by Terrytoons for the following year’s Toyland.) In a group shot, another kitten rides on a Victrola turntable, while one of his siblings turns the crank.

Minnie whispers in Mickey’s ear, realizing that as it’s Christmas, someone should provide these waifs with an appropriate holiday. Mickey and Pluto agree, and tiptoe out the front door. However, before leaving, Mickey pulls down from the wall an old deer head and takes it with him. Minnie keeps the kittens busy, having one blow his nose, and attending to what at first appears to be the “gotta go” needs of another – we think she is escorting him to the restroom – but instead leads him to the curtain concealing the tree, and provides him with an advance candy cane – which the kitten uses like a walking stick, doing an impersonation of Charlie Chaplin’s walk. Suddenly, sleigh bells are heard outside, and Minnie provides a piano accompaniment of “Jingle Bells”, as the arrival of “Santa” is witnessed – Mickey in a fake Santa suit and beard, on an old rocking cair for a sled, pulled by Pluto wearing the deer head. Mickey has obtained a large sack of toys, which he places on the floor. The kids pile into the sack, draining it of contents as they re-emerge. One kitten stops and inquires, “Are you really Santa Claus?” Mickey nods yes, only to be jeered by a raspberry from the kitten, who pulls Mickey’s fake beard, snapping the elastic ear strap back upon Mickey’s face. The party commences, with the kids staging a parade with their toy instruments and the addition of most of Mickey’s kitchen potwear. Mickey’s toy bag seems to have included among other items an abundance of tools, including junior-sized hammers, saws, and drills, which the kittens go to work with on most of the fuurniiture, including making a wreck of the grand piano. A firing squad of pop-gunners make short work of various vases and fishbowls, also popping Mickey in the nose, while a toy cannon attacks from the “rear”. The cannon master also takes off after Pluto, who collides headfirst into the wall. The deer head pops off Pluto’s face, and lands instead on his tail. Realizing the antlers can provide a formidable weapon, Pluto shifts gears and runs backwards, forcing the artillery kitten into retreat.. Finally, the big moment arrives, and Minnie plays a fanfare on a toy trumpet before a curtain, as Mickey and Minnie open the curtain to reveal the lighted tree. The kitten swarm over the tree for the candy canes and hanging toys, completely covering it in a furry feline pyramid, and when the wave of youthful vigor recedes, Mickey and Minnie stare in bewilderment at the tree, denuded to its limbs and stems, for the fade out.

Minnie whispers in Mickey’s ear, realizing that as it’s Christmas, someone should provide these waifs with an appropriate holiday. Mickey and Pluto agree, and tiptoe out the front door. However, before leaving, Mickey pulls down from the wall an old deer head and takes it with him. Minnie keeps the kittens busy, having one blow his nose, and attending to what at first appears to be the “gotta go” needs of another – we think she is escorting him to the restroom – but instead leads him to the curtain concealing the tree, and provides him with an advance candy cane – which the kitten uses like a walking stick, doing an impersonation of Charlie Chaplin’s walk. Suddenly, sleigh bells are heard outside, and Minnie provides a piano accompaniment of “Jingle Bells”, as the arrival of “Santa” is witnessed – Mickey in a fake Santa suit and beard, on an old rocking cair for a sled, pulled by Pluto wearing the deer head. Mickey has obtained a large sack of toys, which he places on the floor. The kids pile into the sack, draining it of contents as they re-emerge. One kitten stops and inquires, “Are you really Santa Claus?” Mickey nods yes, only to be jeered by a raspberry from the kitten, who pulls Mickey’s fake beard, snapping the elastic ear strap back upon Mickey’s face. The party commences, with the kids staging a parade with their toy instruments and the addition of most of Mickey’s kitchen potwear. Mickey’s toy bag seems to have included among other items an abundance of tools, including junior-sized hammers, saws, and drills, which the kittens go to work with on most of the fuurniiture, including making a wreck of the grand piano. A firing squad of pop-gunners make short work of various vases and fishbowls, also popping Mickey in the nose, while a toy cannon attacks from the “rear”. The cannon master also takes off after Pluto, who collides headfirst into the wall. The deer head pops off Pluto’s face, and lands instead on his tail. Realizing the antlers can provide a formidable weapon, Pluto shifts gears and runs backwards, forcing the artillery kitten into retreat.. Finally, the big moment arrives, and Minnie plays a fanfare on a toy trumpet before a curtain, as Mickey and Minnie open the curtain to reveal the lighted tree. The kitten swarm over the tree for the candy canes and hanging toys, completely covering it in a furry feline pyramid, and when the wave of youthful vigor recedes, Mickey and Minnie stare in bewilderment at the tree, denuded to its limbs and stems, for the fade out.

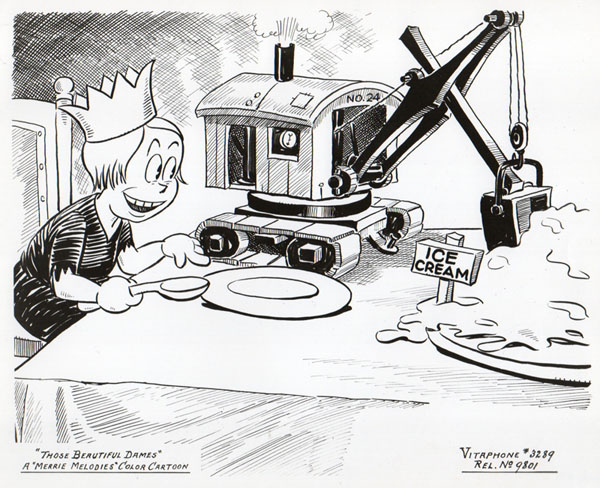

Those Beautiful Dames (Warner, Merrie Melodies (2 strip Technicolor), 11/10/34 – I. (Friz) Freleng, dir.), while never making specific reference to Christmas or Santa, is obviously themed as a vehicle In the Christmas tradition, chronicling the seemingly desolate winter existence of a recurring stereotype of depression-era cartoons – an orphan waif. While most cartoons of the day (as in the next reviewed below) tended to favor orphan boys, this is one of only two I know to feature an orphan girl (the other, coincidentally, being the also-holiday season short from Columbia, The Little Match Girl.) As commonly happens in these cartoons, she trudges through the snow, and passes the attractive window of a toy shop, eyeing its contents longingly. (A similar opening would appear as an orphan eyes kids celebrating around a Christmas tree in Harman-Ising’s The Shanty Where Santy Claus Lives (1933), and in Charles Mintz’s “Bon Bon Parade” (1935), substituting a candy store for the toy store.) Realizing she can’t possibly afford any of the store’s wares, she continues her weary way home to a small shanty, against the cold breezes of a wintery wind which periodically stops her in her tracks (again, a scene similar to “The Shanty Where Santy Claus Lives”, but with a pre-code twist – in “Shanty”, a snowdrift from a roof briefly buries the waif, while here, the icy breeze extends the elastic of the little girl’s panties just far enough to allow a patch of snow to fall off a roof right onto her bare rear end, causing her to leap with a reactive “Oooh!”

The girl enters her humble tumble-down shack, which, while including a pot-bellied stove, seems a bit short on wood to keep the home fires burning. In a nice touch, as the girl attempts to fan the flames inside by blowing on them, a group of icicles hanging from the upper ceiling of the stove chamber drips water on the fire, dousing the flame entirely. (Ice in a stove? That’s one awfully cold flame.) The girl is forced to huddle under a blanket on an old wooden chair, and falls asleep, braced for another miserably cold evening.

Without a word of explanation, nor even a camera segue (the action jump-cuts following a fade out on the girl, also with an audible music break – suggesting that something may have been removed in the film’s final edit for content or time), the toys from the toy store arrive outside on an errand of mercy. (We saw no signs before of them being alive, nor did any good fairy wave a wand, so the Termite Terrace gang expect us to believe in this metamorphosis on blind faith alone, as presumably deriving from “holiday magic”.) As the girl sleeps, the toys perform a massive makeover of her hovel. A toy fire engine sprays a new coat of paint on some of her walls, while others are wallpapered by a hobby horse using its brush tail to spread the paste, while a toy steamroller unrolls the wallpaper vertically up the walls. By the stroke of midnight, the toys awaken the girl to find a crown upon her head, and a warm and pleasant home with a new roaring fireplace and comfortable furnishings. (Who among these toys had access to a wholesale furniture warehouse?) A trio of mama dolls announce that the toys will put on a show for her, while a pair of Negro dolls (resembling the Gold Dust Twins) also announce they’ve prepared a chocolate cake for her. As the little girl applauds in appreciation, the celebration commences with a nicely animated dance number by a pair of clown dolls with bodies and legs built out of concertina bellows (animation here is exceptionally fluid, and augmented by shadow work as the characters perform in a spotlight). Meanwhile, a toy construction shovel bites a couple of healthy free samples off the rear of the girl’s chocolate cake, to the disapproval of one of the mama dolls. The gitl is presented with a Kiddy Phone record player, with disc that plays the title song of the film, as a perimeter of painted bears dances around the phonograph’s base as a chorus line in time to the music (even getting stuck on a step when the record needle gets caught on a skip). Finally, a couple of toy soldiers sound a trumpet fanfare (deflating themselves until they no longer fill the waistlines of their belts – this shot would be reused in “Toy Town Hall” in 1936), and a curtain opens to reveal a new wing built onto the hovel, in which is a massive banquet table big enough to seat all the toys and the little girl too, to feast upon chocolate cake and three flavors of ice cream with cherries on top. The girl takes her place at the head of the table, and on the count of “One, two, three, Go!”. everyone digs in, with the steam shovel serving portions of ice-cream with its clam-digger shovel. But the toys have an odd sense of humor. Instead of letting the girl gorge herself to satisfy the ravenous hunger of her past existence, they hide a jack in the box inside her ice cream sundae, popping out to displace the ice cream. Even the girl reacts curiously to the joke, only gradually changing between shocked startlement to building giggles. It’s an odd way to close, and you’d think the toys would at least have set out a bigger dish of ice cream for the girl to make up for their lame joke.

Without a word of explanation, nor even a camera segue (the action jump-cuts following a fade out on the girl, also with an audible music break – suggesting that something may have been removed in the film’s final edit for content or time), the toys from the toy store arrive outside on an errand of mercy. (We saw no signs before of them being alive, nor did any good fairy wave a wand, so the Termite Terrace gang expect us to believe in this metamorphosis on blind faith alone, as presumably deriving from “holiday magic”.) As the girl sleeps, the toys perform a massive makeover of her hovel. A toy fire engine sprays a new coat of paint on some of her walls, while others are wallpapered by a hobby horse using its brush tail to spread the paste, while a toy steamroller unrolls the wallpaper vertically up the walls. By the stroke of midnight, the toys awaken the girl to find a crown upon her head, and a warm and pleasant home with a new roaring fireplace and comfortable furnishings. (Who among these toys had access to a wholesale furniture warehouse?) A trio of mama dolls announce that the toys will put on a show for her, while a pair of Negro dolls (resembling the Gold Dust Twins) also announce they’ve prepared a chocolate cake for her. As the little girl applauds in appreciation, the celebration commences with a nicely animated dance number by a pair of clown dolls with bodies and legs built out of concertina bellows (animation here is exceptionally fluid, and augmented by shadow work as the characters perform in a spotlight). Meanwhile, a toy construction shovel bites a couple of healthy free samples off the rear of the girl’s chocolate cake, to the disapproval of one of the mama dolls. The gitl is presented with a Kiddy Phone record player, with disc that plays the title song of the film, as a perimeter of painted bears dances around the phonograph’s base as a chorus line in time to the music (even getting stuck on a step when the record needle gets caught on a skip). Finally, a couple of toy soldiers sound a trumpet fanfare (deflating themselves until they no longer fill the waistlines of their belts – this shot would be reused in “Toy Town Hall” in 1936), and a curtain opens to reveal a new wing built onto the hovel, in which is a massive banquet table big enough to seat all the toys and the little girl too, to feast upon chocolate cake and three flavors of ice cream with cherries on top. The girl takes her place at the head of the table, and on the count of “One, two, three, Go!”. everyone digs in, with the steam shovel serving portions of ice-cream with its clam-digger shovel. But the toys have an odd sense of humor. Instead of letting the girl gorge herself to satisfy the ravenous hunger of her past existence, they hide a jack in the box inside her ice cream sundae, popping out to displace the ice cream. Even the girl reacts curiously to the joke, only gradually changing between shocked startlement to building giggles. It’s an odd way to close, and you’d think the toys would at least have set out a bigger dish of ice cream for the girl to make up for their lame joke.

We’ll close this session with Gifts From the Air (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Color Rhapsodies, released slightly after the fact on 1/1/37 – Ben Harrison, dir.). While this title has appeared at least once before on a Christmas post, it merits repeating and fits well into the thread of this article. It should first be noted that cuurrent web posts of this cartoon truly do not do the film’s visuals justice. I own an IB Technicole 16mm of this film (with a few splices, but otherwise reasonably clean), and the colors are stunning (particularly one of the most intense and unique mahogany-browns I have ever seen reproduced by a film, from the paneling of the waif’s radio set surrounding the circular speaker from where Santa appears. Oh, how I wish someone could produce a high-def digital scan to preseve this work beyond its original medium.

The film open almost identically to the studio’s prior Bon Bon Parade referenced above, with waif (a boy) peering in a toy shop window on a snowy Christmas eve (this time we know it’s Christmas, as a quartet of carolers perform “Silent Night” off to one side. The boy is in fact the identical waif who visited Canfyland in the studio’s prior production – so I guess his previous wish to live forever among the candies didn’t end up as planned. Among the toys in the window are two wind-up toy soldiers, performing an energetic tap dance. At the conclusion of the number, the boy applauds, and one of the soldiers takes a particular liking to him. Pushing the second soldier out of his way, the friendly one doubles his efforts to give a “pull out all the stops” performance – but his mainspring winds down, causing his head to pop off attached to an extension of his inner spring workings. With great effort, the soldier winds his own key in his back, and resumes the dance again. But the strain on his construction is too much, and his segmented limbs begin to separate from his torso and from one another, while his head pops off again, and he slumps into a heap. The toy shop owner spots that the figure isn’t working, and removes him from the store window. A few seconds later, the boy observes the owner outside, tossing the used-up soldier into a trash can. Once the owner returns into the shop, the boy dashes to the trash can and retrieves the parts of the soldier. His head has come completely loose from his body, and the soldier’s head cries two tears, which become frozen upon the end of his nose, until the neckless head somehow manages by will power alone to shake from side to side, shaking loose the icicle, but also dislodging his nose from his face on another extension of spring. The boy pops the soldier’s head back into his body, then carries the figure home to his own version of a shanty hovel.

The film open almost identically to the studio’s prior Bon Bon Parade referenced above, with waif (a boy) peering in a toy shop window on a snowy Christmas eve (this time we know it’s Christmas, as a quartet of carolers perform “Silent Night” off to one side. The boy is in fact the identical waif who visited Canfyland in the studio’s prior production – so I guess his previous wish to live forever among the candies didn’t end up as planned. Among the toys in the window are two wind-up toy soldiers, performing an energetic tap dance. At the conclusion of the number, the boy applauds, and one of the soldiers takes a particular liking to him. Pushing the second soldier out of his way, the friendly one doubles his efforts to give a “pull out all the stops” performance – but his mainspring winds down, causing his head to pop off attached to an extension of his inner spring workings. With great effort, the soldier winds his own key in his back, and resumes the dance again. But the strain on his construction is too much, and his segmented limbs begin to separate from his torso and from one another, while his head pops off again, and he slumps into a heap. The toy shop owner spots that the figure isn’t working, and removes him from the store window. A few seconds later, the boy observes the owner outside, tossing the used-up soldier into a trash can. Once the owner returns into the shop, the boy dashes to the trash can and retrieves the parts of the soldier. His head has come completely loose from his body, and the soldier’s head cries two tears, which become frozen upon the end of his nose, until the neckless head somehow manages by will power alone to shake from side to side, shaking loose the icicle, but also dislodging his nose from his face on another extension of spring. The boy pops the soldier’s head back into his body, then carries the figure home to his own version of a shanty hovel.

The orphan’s shack is small and meagerly furnished, but not nearly as depressing as the little girl’s in “Dames” above. For one thing, the stove appears to work, and there is a gentle yellow glow. For another, the child, in spite of his meager means, possesses a radio set. Setting the soldier on a table aside the radio, the boy announces, “We’re going to have a real Christmas.” In a partially-lifted gag from Max Fleischer’s “Christmas Comes But Once a Year”, the child produces a tattered green umbrella, which he opens, mounting the handle in the top of a barrel, to serve as a Christmas tree. With a bowl of liquid soap and a toy bubble pipe, he blows a series of bubbles which attach themselves to the stems of the umbrella, as a last bubble partially pops on the umbrella shaft’s top point, miraculously transforming itself into the shape of a star. For electricity, the boy grabs his pet cat, stroking his fur the wrong way to build up a supply of static electricity, then “plugs” the cat’s tail into a knothole of the barrel, causing the bubbles to light up like electric bulbs. (If the child has no electric socket, how does he operate the radio? Must be an early battery-powered model.) For a final touch, he hangs one of his stockings near the stove on the wall for Santa to fill – but, realizing his socks have plenty of holes in them, the boy disconnects part of the stovepipe and shoves it into the bottom hole of the sock, closing the pipe’s vent so that no toys will spill out. (With no stovepipe, why doesn’t the stove fill the room with smoke?) With the stage now set for Christmas morning, the boy climbs into bed, and is soon fast asleep.

“Wanna Buy A Duck?”

As soon as the boy nods off, the toy soldier springs to life again, and turns on the boy’s radio set. In the manner of a “Radio Patrol” style police show, the soldier calls into the speaker of the set as if it were a broadcast microphone, “Calling all stars! Calling all stars!” The circle of the speaker mesh lights up, and we see a winter landscape with an image of Santa and his sleigh approaching from the distance. Santa pulls his team to a stop just inside the radio set, and leaps out of the speaker into the room with a full sack of toys. This sack evidently is not the one from which Santa distributes toys to the entire world – as its entire contents get emptied into the boy’s stocking. Then, Santa departs the way he came. When the boy awakes, it seems the toy store’s entire inventory – and then some – has been received to provide him with a merry day. Among the items received are various playthings bearing non-coincidental resemblance to famours radio, film, and recording stars. (IMDB credits celebrity impersonations on this cartoon to The Radio Rogues – a small troupe of quire competent impersonators who made periodic appearances in film as well as on air, including in the Paramount feature. “Every Night at Eight”, and in at least one of MGM’s Technicolor “all star” shorts of the 1930’s that has appeared as a bonus extra on a Warner DVD I do not presently recall.) A mechanical duck is ridden by Joe Penner, repeating his ever-present catch phrase, “Wanna buy a duck?” A two-faced roly-poly features on one side Paul Whiteman, and on the other side equally round Kate Smith. A wind-ip toy band is conducted and announced by Ben Bernie, referring to himself as “the old mousetrap” rather than “maestro”. A toy fire engine is driven by Texaco’s “Fire Chief” Ed Wynn. A dancing bead doll mimics Eddie Cantor, with a whiskered version of Greek-accented comedian “Parkyakarkas” playing Santa in a Jack in the box. In the oddest placement of any star in the film, Bing Crosby’s voice emanates from a wind-up goat, who croons his “Baaa”s in prescient prediction of Bing’s hit over a decade later with “The Whiffenpoof Song”. A final large package is in the bottom of the stocking, which unfolds to reveal what every party needs – eats, in the form of a dinner table and tablecloth, topped with a whole steaming roast turkey, chocolate cake, and a bottle of milk. Bowing to the late release of the cartoon, the writers cover both seasonal holidays at once, by having the toys perform a chorus of “Auld Lang Syne”. The boy hungrily yanks a drumstick from the turkey, and is about to chomp, when he notices the toy soldier eyeing it hungrily, too. Somehow realizing that the toy soldier brought him good fortune, the boy is willing to share, giving the soldier the first turkey leg, while he himself takes the second – and further shares by pouring his cat milk from the bottle. Everything ends happily, and the air is festooned with confetti and more soap bubbles, as the music reaches a crescendo for the final iris out.

I hope this little exercise in festivity has sparked a few warm nostalgic feelings and fond memories of when the holidays were indeed cause for celebration. Here’s hoping that someday, they may be again. In the meanwhile, have a very merry virtual Christmas, as wished from the definitely real flesh and blood Charles Gardner.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

I’m getting to the age where I don’t feel like going to a lot of parties anyway, and I’m actually quite glad that my neighbours aren’t having them now.

I don’t want to be a nudnik — okay, well maybe I do, a little — but the neon-lit Hebrew letters flashing in that in that Fleischer Screen Song simply spell out the word “kosher”, not “kosher l’pesach” (kosher for Passover). “Kosher” would have been the Hebrew word most familiar to New Yorkers at that time, being emblazoned on practically every deli in the city. Besides, another neon sign in that scene bears the word “popcorn”, which, as a non-matzoh grain product, is definitely NOT kosher for Passover, although I understand that some rabbinical authorities are allowing it now, along with other trayf like (gag) quinoa. Oh great, now I’ve got a hankering for charoses and macaroons….

You’re absolutely correct that the electric organ was a new instrument in 1942, having been introduced by the Hammond company in 1935. In 1941 the American Guild of Organists did a survey of its membership, asking what they thought of the new Hammond “organ” (they put the word in quotes), and the response was unanimously hostile. I found out about that while doing research for an article I wrote several years ago, and I now wish I had known about “Mickey’s Birthday Party” at that time; one advantage the electric organ has over the pipe organ is that the latter really doesn’t make a practical birthday gift!

I wish you and all Cartoon Research readers the most merry and festive holiday that can be had under the present circumstances. Next year in Jerusalem!

OMG!!!! A christmas toon i had never seen (“ Gifts”). Gorrrgeous! Thsnk YOO!!

Maybe a little outside this particular box, but the 1950 TV special “An Hour in Wonderland” is framed as a party hosted at the studio by Uncle Walt and sponsored by Coca Cola. Good stuff. It’s on the two-disc release of the animated “Alice in Wonderland”.

The images in that David Gerstein blogpost (broken when Gerstein’s old personal web space here on Cartoon Research got the axe) can still be seen via the Wayback Machine: http://web.archive.org/web/20170716152712/http://ramapithblog.blogspot.com/2012/06/mouse-interrupted.html (right click the images and open in a new tab/window to view them larger).

That YouTube embed of Gifts From the Air is actually from a 16mm IB Technicolor transfer by Steve Stanchfield. The Blu-ray copy I have looks a tad richer and overall very nice. But such prints can vary a little in color balance, and this one looks a little dark, so maybe yours is even better. I did see it stated once that video transfers don’t exactly do justice to the richness of projected IB Technicolor, however…

A favorite early party-themed cartoon not mentioned is the Fleischer Screen Song A Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight (1930), with Seymour Kneitel as the sole character animator and “de-facto director”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=caeOJILw990

And here’s an actually decent upload of that transfer of My Wife’s Gone To the Country: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kuDIcgn9HTU

Don’t forget “The Whoopee Party” (9/17/1932), the only time Mickey threw a party so wild that the cops showed up.

Thanks as always!!