I bet you’ve just been itching for more coverage of the checkered career of the common flea in animated film. Well, you can quit kicking – because that’s just what we’re serving up this week – starting with a Looney!

Perhaps the most well-known and favorably remembered flea cartoon of all time was Bob Clampett’s An Itch In Time (Warner, Merrie Melodies (Elmer Fudd), 12/4/43), a popular perrenial filled with wild Rod Scribner animation. Curiously, Clampett was obviously continuing to follow the work of his old studio arch-rival, Tex Avery, who had left at Schlesinger’s bidding for the greener pastures of MGM, as the first gag of the cartoon is nearly a direct lift from the the standard playbook of Avery “sign” gags. A small dot bounces across the living room of Elmer and his pet dog. A human hand attached to no one in particular holds out a pointing sign in front of the camera, to inform us, “It’s a flea, folks.” Them a second sign is brought into view – “Teeny, ain’t he?” (Avery had put such gags into regular use as early as his first cartoon for MGM, “The Early Bird dood It”, and would continue to use similar riffs in countless episodes.) Clampett also fall back on earlier MGM inspiration, designing his flea as something of a modification of the “hobo” concept from The Homeless Flea, except in a more “hillbilly” variety, with an oversized rural hat, buck teeth, and a small suitcase on a pole (identifying him as “A. Flea”) in place of the bindle stick. Color scheme of the character is in a solid royal blue with deeper blue nose, set off by a shaggy strip of bright red hair covering his eyes.

Flea produces from his suitcase a telescope four times too large to fit, and sets his sights on the visually emphasized rump of the sleeping canine, yelling, “T-BONE!!!” The flea breaks into a song of celebration which is an original composition punctuating his sequences throughout the film – “There’ll Be Food Around the Corner” (metered to roughly suggest the rural melody, “She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain”). Mounting the dog’s nose, the flea hides in the dog’s ear, and to keep him docile and pacified, whispers him a lullaby. Once the dog is fully in dreamland, Flea heads for the dog’s tender back, marks off a spot with splashes of mustard, catsup, and a dash of salt, and takes up a healthy helping of the dog’s skin between two slices of bread (not forgetting, of course, to tear off one meat rationing point off his wartime book of ration stamps). His bite causes the dog to use one of Clampett’s favorite catch-phrases: “Oh, agony! A-go-NY!!!” The dog engages in a fit of scratching and biting. Racing just one step ahead of the teeth within the dog’s fur, Flea stops the onslaught by holding up a chunk of the dog’s skin between himself and the teeth, causing the dog to chomp on himself. With his backside glowing red, the dog leaps whimpering (in the “crying jag” mode of Stan Laurel) into the arms of Elmer Fudd (who’s taken nearly four minutes to get into the action of his own cartoon). The choice of Elmer for this film is actually strange, as not only was Elmer not accustomed to solo starring roles since the inception of his career a few years prior, but all of his action could easily be imagined as standard repertoire for an appearance by Porky Pig. Was the storyboard originally written as a Porky project? Anyway, Elmer thinks he has the situation well in hand, by applying to the dog’s back a liberal dose of flea powder. But the stuff has no effect on flea, who casually ice-skates atop its white coating as if in a winter carnival. Elmer announces that if he sees the dog make with one more scratch, it’ll mean a bath. The dog sees nothing but unpleasant images of drowning in bubbles and scrub brushes, and, materializing an angel’s halo, crosses his heart in pledge that there’ll be no more scratching.

Flea produces from his suitcase a telescope four times too large to fit, and sets his sights on the visually emphasized rump of the sleeping canine, yelling, “T-BONE!!!” The flea breaks into a song of celebration which is an original composition punctuating his sequences throughout the film – “There’ll Be Food Around the Corner” (metered to roughly suggest the rural melody, “She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain”). Mounting the dog’s nose, the flea hides in the dog’s ear, and to keep him docile and pacified, whispers him a lullaby. Once the dog is fully in dreamland, Flea heads for the dog’s tender back, marks off a spot with splashes of mustard, catsup, and a dash of salt, and takes up a healthy helping of the dog’s skin between two slices of bread (not forgetting, of course, to tear off one meat rationing point off his wartime book of ration stamps). His bite causes the dog to use one of Clampett’s favorite catch-phrases: “Oh, agony! A-go-NY!!!” The dog engages in a fit of scratching and biting. Racing just one step ahead of the teeth within the dog’s fur, Flea stops the onslaught by holding up a chunk of the dog’s skin between himself and the teeth, causing the dog to chomp on himself. With his backside glowing red, the dog leaps whimpering (in the “crying jag” mode of Stan Laurel) into the arms of Elmer Fudd (who’s taken nearly four minutes to get into the action of his own cartoon). The choice of Elmer for this film is actually strange, as not only was Elmer not accustomed to solo starring roles since the inception of his career a few years prior, but all of his action could easily be imagined as standard repertoire for an appearance by Porky Pig. Was the storyboard originally written as a Porky project? Anyway, Elmer thinks he has the situation well in hand, by applying to the dog’s back a liberal dose of flea powder. But the stuff has no effect on flea, who casually ice-skates atop its white coating as if in a winter carnival. Elmer announces that if he sees the dog make with one more scratch, it’ll mean a bath. The dog sees nothing but unpleasant images of drowning in bubbles and scrub brushes, and, materializing an angel’s halo, crosses his heart in pledge that there’ll be no more scratching.

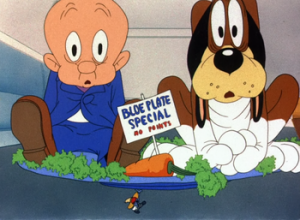

Now flea pulls out the heavy artillery. Armed with miniature shovels, pick axes, rakes, drills, and even a mechanical jack hammer, he studies a meat chart for canine butchers, and marks off with charcoal choice territory which he labels “Rump Roast”. He lets fly with a blow of the pick axe. The dog stiffens out, and is about to respond with his natural reflex – but the watchful eye of Elmer makes his paw stop dead in its tracks. The dog’s brow bristles with beads of perspiration, as he desperately attempts to hold back the urge despite the flea’s drilling and jack hammering. The dog even resorts to chicanery – kicking a second pet of the household – a cat – just so the cat will react with violent scratching to soothe the dog’s misery. But an icy stare from Elmer brings a cease to even this brief relief. After the dog turns nearly every color in the Technicolr pallette (including polka dot and plaid), ignition of a stockpile of high explosives by the flea (while he hides in the safety of a “Hair Raid Shelter”) finally brings the dog to the point he can stand it no longer. Racing around the living room dragging his rear end along the carpet (in the same manner as the dog in “The Homeless Flea”, but in more pronounced exaggeration of movement), the dog (as well as the orchestra) stop cold in their tracks, as the dog tells the audience in complete underplay, “Hey, I better cut this out. I may get to like it!” (Clampett once stated in an interview that this line was tossed in as a gag test of the censorship board, with the complete expectation that it would be ordered snipped out – yet miraculously passed unnoticed.) Elmer charges in and takes hold of the helpless mutt, dragging him (as he still clings to the remnants of a door which he has torn off its hinges) toward the bath bucket. Surprise! Elmer develops the itches, as Flea has changed targets. With roles now reversed, the dog happily ushers Elmer toward the wash basin, but slips on a bar of soap. Both characters fly through the air and land in the bucket, coming out adorned in suds that make them resemble Santa and a reindeer. However, the bucket is pulled out from under them, and replaced by flea with a large plate garnished with carrots and parsley – and a sign reading “Blue Plate Special (No Points)”. As flea carries both of them off for his feast, Clampett just has time for his inevitable suicide gag from the cat – “Well, now I’ve seen everything” – as he pulls out a pistol and blows his brains out.

Now flea pulls out the heavy artillery. Armed with miniature shovels, pick axes, rakes, drills, and even a mechanical jack hammer, he studies a meat chart for canine butchers, and marks off with charcoal choice territory which he labels “Rump Roast”. He lets fly with a blow of the pick axe. The dog stiffens out, and is about to respond with his natural reflex – but the watchful eye of Elmer makes his paw stop dead in its tracks. The dog’s brow bristles with beads of perspiration, as he desperately attempts to hold back the urge despite the flea’s drilling and jack hammering. The dog even resorts to chicanery – kicking a second pet of the household – a cat – just so the cat will react with violent scratching to soothe the dog’s misery. But an icy stare from Elmer brings a cease to even this brief relief. After the dog turns nearly every color in the Technicolr pallette (including polka dot and plaid), ignition of a stockpile of high explosives by the flea (while he hides in the safety of a “Hair Raid Shelter”) finally brings the dog to the point he can stand it no longer. Racing around the living room dragging his rear end along the carpet (in the same manner as the dog in “The Homeless Flea”, but in more pronounced exaggeration of movement), the dog (as well as the orchestra) stop cold in their tracks, as the dog tells the audience in complete underplay, “Hey, I better cut this out. I may get to like it!” (Clampett once stated in an interview that this line was tossed in as a gag test of the censorship board, with the complete expectation that it would be ordered snipped out – yet miraculously passed unnoticed.) Elmer charges in and takes hold of the helpless mutt, dragging him (as he still clings to the remnants of a door which he has torn off its hinges) toward the bath bucket. Surprise! Elmer develops the itches, as Flea has changed targets. With roles now reversed, the dog happily ushers Elmer toward the wash basin, but slips on a bar of soap. Both characters fly through the air and land in the bucket, coming out adorned in suds that make them resemble Santa and a reindeer. However, the bucket is pulled out from under them, and replaced by flea with a large plate garnished with carrots and parsley – and a sign reading “Blue Plate Special (No Points)”. As flea carries both of them off for his feast, Clampett just has time for his inevitable suicide gag from the cat – “Well, now I’ve seen everything” – as he pulls out a pistol and blows his brains out.

A Horse Fly Fleas (Warner, 12/13/47 – Robert McKimson, dir.), is a sort-of direct sequel to “An Itch In Time”. However, A. Flea has undergone some personality changes, as well as squaring off with the differing approach of a new director. Instead of a country bumpkin in a hillbilly hat, Flea now wears a miniature coonskin cap, and has transformed into a scouting pioneer – sort of an insect Daniel Boone. But his “wild frontier” to explore is still the residential neighborhood of an average community. The film opens with virtually the identical sign gag from the first film – only altered by a few words on the second sign, now reading, “Little guy, ain’t he”. Flea also maintains his signature theme song, but with slight lyric alteration to “Home Around the Corner” instead of “Food” – McKimson wasn’t going to dip to the crudeness of Clampett’s appetite-driven bottomless pit.

A Horse Fly Fleas (Warner, 12/13/47 – Robert McKimson, dir.), is a sort-of direct sequel to “An Itch In Time”. However, A. Flea has undergone some personality changes, as well as squaring off with the differing approach of a new director. Instead of a country bumpkin in a hillbilly hat, Flea now wears a miniature coonskin cap, and has transformed into a scouting pioneer – sort of an insect Daniel Boone. But his “wild frontier” to explore is still the residential neighborhood of an average community. The film opens with virtually the identical sign gag from the first film – only altered by a few words on the second sign, now reading, “Little guy, ain’t he”. Flea also maintains his signature theme song, but with slight lyric alteration to “Home Around the Corner” instead of “Food” – McKimson wasn’t going to dip to the crudeness of Clampett’s appetite-driven bottomless pit.

This time, A. Flea picks up a partner in the form of a horse fly (shaped like his host animal with wings) who has lost his horse (a milk wagon steed who was replaced by an auto). They team up to seek a new home in “yonder mountains” – the rising brown peaks of the same sleeping dog from the original film. Again exploring within the dog’s fur, they encounter a sign: “Indian Flea Territory. Pake face flea keep out.” Flea tells his steed, “You know, I bet I miss a lot of things by not being able to read.” (A notable character inconsistency – he didn’t have any trouble figuring out the ration point stamps or finding the “hair raid shelter” in film one – but who expected an audience to remember these little details after several years lapse.) Now copying from MGM’s “The Homeless Flea”, A. Flea chops down a clump of dog hairs (with the same sound of falling timber to rile the dog), and constructs a rustic log cabin. For a final touch, he begins to drill a deep well with a pick-axe, causing the dog to shriek.

This time, A. Flea picks up a partner in the form of a horse fly (shaped like his host animal with wings) who has lost his horse (a milk wagon steed who was replaced by an auto). They team up to seek a new home in “yonder mountains” – the rising brown peaks of the same sleeping dog from the original film. Again exploring within the dog’s fur, they encounter a sign: “Indian Flea Territory. Pake face flea keep out.” Flea tells his steed, “You know, I bet I miss a lot of things by not being able to read.” (A notable character inconsistency – he didn’t have any trouble figuring out the ration point stamps or finding the “hair raid shelter” in film one – but who expected an audience to remember these little details after several years lapse.) Now copying from MGM’s “The Homeless Flea”, A. Flea chops down a clump of dog hairs (with the same sound of falling timber to rile the dog), and constructs a rustic log cabin. For a final touch, he begins to drill a deep well with a pick-axe, causing the dog to shriek.

But before a formal house-warming, an Indian arrow strikes Flea’s cap. A lone scout alerts the chief of A. Flea’s presence, and smoke signals go up from the dog alerting the tribe. Flea mounts his trusty horsefly, and the remainder of the film is set to a lengthy Indian chase in the tradition of the vintage B-Western. Another gag is lifted from “An Itch In Time”, as the dog, finally wising up to the activities on his carcass, applies flea powder. A. Flea responds by hitching a sled to his “ol’ dobbin”, while the Indians speed through the hair forest on skis. Capturing the flea, the Indian flies toe him to a stake and light a bonfire below him. In a lift from both “The Homeless Flea” and “Itch In Time”, the dog screams from being set ablaze, and races in panic around the room. He exits the house and dips his rear end in an exterior fountain for soothing relief, and all the fleas briefly abandon him in war canoes. A brief passage of time is denoted by a fade out, with action resuming back in the living room, as a miniature procession of circus wagons crosses the living room, past a small sign in the carpet pointing to “Winter Quarters”. The entire string of wagons heads for and rolls straight up the tail of the dog. From the opposite direction, the flea, horsefly, and Indians remount the dog on his front paw. Glaring at us in frustration, the dog does nothing, seemingly having run out of ideas. Inside his fur, we see that the circus has set up a big top tent, advertising the appearance of a “Wild West Show”. A. Flea and his steed, closely pursued by the Indians, enter the main entrance. From above, the dog now views them with a magnifying glass, as a spectator equipped with popcorn, cotton candy, and balloons. “Oh boy”, he says to us, “I haven’t seen a circus since I was a little pup”. In the center ring, the Indians continue the chase of Flea round and round the tent. In the final shot, Flea tells the audience, “As long as they’re gonna chase me anyway, I might as well get paid for it!”

But before a formal house-warming, an Indian arrow strikes Flea’s cap. A lone scout alerts the chief of A. Flea’s presence, and smoke signals go up from the dog alerting the tribe. Flea mounts his trusty horsefly, and the remainder of the film is set to a lengthy Indian chase in the tradition of the vintage B-Western. Another gag is lifted from “An Itch In Time”, as the dog, finally wising up to the activities on his carcass, applies flea powder. A. Flea responds by hitching a sled to his “ol’ dobbin”, while the Indians speed through the hair forest on skis. Capturing the flea, the Indian flies toe him to a stake and light a bonfire below him. In a lift from both “The Homeless Flea” and “Itch In Time”, the dog screams from being set ablaze, and races in panic around the room. He exits the house and dips his rear end in an exterior fountain for soothing relief, and all the fleas briefly abandon him in war canoes. A brief passage of time is denoted by a fade out, with action resuming back in the living room, as a miniature procession of circus wagons crosses the living room, past a small sign in the carpet pointing to “Winter Quarters”. The entire string of wagons heads for and rolls straight up the tail of the dog. From the opposite direction, the flea, horsefly, and Indians remount the dog on his front paw. Glaring at us in frustration, the dog does nothing, seemingly having run out of ideas. Inside his fur, we see that the circus has set up a big top tent, advertising the appearance of a “Wild West Show”. A. Flea and his steed, closely pursued by the Indians, enter the main entrance. From above, the dog now views them with a magnifying glass, as a spectator equipped with popcorn, cotton candy, and balloons. “Oh boy”, he says to us, “I haven’t seen a circus since I was a little pup”. In the center ring, the Indians continue the chase of Flea round and round the tent. In the final shot, Flea tells the audience, “As long as they’re gonna chase me anyway, I might as well get paid for it!”

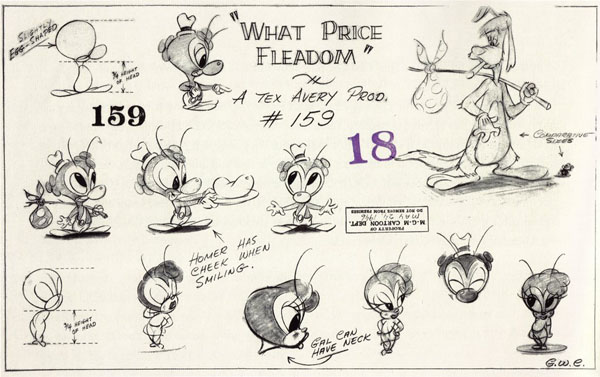

What Price Fleadom? (MGM, 3/20/48 – Tex Avery, dir.) is the direct descendant of MGM ‘s previous influential success, The Homeless Flea, repeating in close approximation the original design of our hobo flea, who now is assigned a name befitting his previous endless search for a place of residence – Homer. Of course, Avery was essentially at war with the old Disney-paced, “cutesy” style of the studio’s earlier efforts, at least ever since Screwball Squirrel beat up on cute Sammy Squirrel in the former’s premiere episode. So the old idea gets the new “Avery” treatment. But not without a little sentiment first to remind one of the studio’s old days. Under a bridge, in what amounts to an animal hobo jungle, a country bumpkin dog (credited on IMDB as Avery himself, doing his best impression of Pinto Colvig) warms a can of beans over an open fire, while on his back another small campfire warms the furry residence of Homer Flea (who has again hung up his “Home Sweet Home” sign left over from his original appearance. The dog calls that dinner’s ready, and presents Homer with a singe bean that is nearly too big for Homer’s miniature plate. He sits down to supper at a bottle cap that serves as a table, and he and the dog eat heartily. They both pick their teeth after dinner, and bed down for the night in their respective residences (Homer in the dog’s fur, the dog under the bridge), with the dog wishing Homer good night and blowing out both campfires. They are obviously leading an ideal life of friendship – – –

What Price Fleadom? (MGM, 3/20/48 – Tex Avery, dir.) is the direct descendant of MGM ‘s previous influential success, The Homeless Flea, repeating in close approximation the original design of our hobo flea, who now is assigned a name befitting his previous endless search for a place of residence – Homer. Of course, Avery was essentially at war with the old Disney-paced, “cutesy” style of the studio’s earlier efforts, at least ever since Screwball Squirrel beat up on cute Sammy Squirrel in the former’s premiere episode. So the old idea gets the new “Avery” treatment. But not without a little sentiment first to remind one of the studio’s old days. Under a bridge, in what amounts to an animal hobo jungle, a country bumpkin dog (credited on IMDB as Avery himself, doing his best impression of Pinto Colvig) warms a can of beans over an open fire, while on his back another small campfire warms the furry residence of Homer Flea (who has again hung up his “Home Sweet Home” sign left over from his original appearance. The dog calls that dinner’s ready, and presents Homer with a singe bean that is nearly too big for Homer’s miniature plate. He sits down to supper at a bottle cap that serves as a table, and he and the dog eat heartily. They both pick their teeth after dinner, and bed down for the night in their respective residences (Homer in the dog’s fur, the dog under the bridge), with the dog wishing Homer good night and blowing out both campfires. They are obviously leading an ideal life of friendship – – –

Until next morning. Homer awakes from his bed (a matchbox), and pulling a cord, opens the dog’s fur to let the sunlight in as if a windowshade. A new sight makes Homer sit up and take notice. A tough gray bulldog is passing by, and on his back rides a curvaceous female flea (resembling a little human pin-up girl), who buzzes a “Hello” and drops a handkerchief. Homer’s eyes “bug out” shaped like hearts, and with a few leaps, he is also on the bulldog. He and the girl engage in a merry lover’s chase through the gray fur forest, while the dog notices an unusual amount of activity in his nether regions. The dog starts nipping at his fur – and we soon discover he has false teeth, which come out and keep chomping of their own power without the assistance of their owner. The teeth chase Homer onto the sidewalk, then back onto the dog’s rear, taking a bote out of his tail in the process. But they’ve done their job, as Homer dangles again by his suspenders from a toothy point. The dig stomps on Homer and atempts to crush him underfoot – but the flattened Homer is completely revived by a mere farewell wave from the girl on the departing dog. Homer is back in a zip, and the dog knows he’s up against a tough customer. The dog disappears into the door of a local pet shop – and emerges carrying all variety of cleaning/bathing apparatus, not limited to a large container of DDT, and returns home. In the shower, he applies all manner of anti-insect products, including something marked “Sheep Dip”, and a bar of soap with brand name “Lice-Buoy”. Homer, however, is as impervious to such things as A. Flea, and stands in his underwear atop the dog’s head, enjoying bath time. The dog, with soap in his eyes, looks for a towel. Homer jumps onto the towel rack, and replaces the towel with a sheet of fly paper. We get a repeat of the old gag from “Screwball Squirrel” of the dog applying the “towel” to dry his face – and ripping all his facial features off onto the flypaper.

Meanwhile back at the bridge, the country dog calls Homer to come to breakfast, but receives no reply – except a small note which falls from his back, reading, “Dear Pal: Good bye forever. Homer.” The dog engages in a frantic search for his lifelong pal. He inspects the long white beard of a sleeping old man in the park. Out of the bead fly half a sozen small songbirds, and three ducks – followed by a shotgun self-emerging from the beard while the man continues to sleep, shooting skyward and felling one of the ducks. At another location, te country dog checks out a doghouse with the name “Otto”. Out the door emerges a mile-long Dachshund, which, to the larger dog’s surprise, turns out to have a head on both ends.

Back at the bulldog’s place, a frantic chase ensues, accompanied musically by a Scott Bradlley rendition of “Go In and Out the Window”. After hopping all over the living room, Homer jumps into a painting (followed by the dog), and disappears in perspective into the backgroud. In the next frame picture frame, in another perspective shot down the main street of an old Western towm the flea reappears hopping toward the camera, the dog still in pursuit, and both exit the picture. (This basic gag would be remembered by Hanna-Barbera years later for the opening of the Yogi Bear show, though it has also seen use in some Dick Lundy Woody Woodpecker variation such as Smoked Hams and Wet Blanket Policy, and earlier still in MGM’s own Art Gallery (1939).)

Ducking into the carpet, Homer crosses the living room again, only to be met at the other end of the rug by the bulldog and a double-barreled shotgun. Homer hops right into one gun barrel, then out the other, but the dog takes aim and fires, leading to an abrupt fade-out with the dog wearing a satisfied smile.

Ducking into the carpet, Homer crosses the living room again, only to be met at the other end of the rug by the bulldog and a double-barreled shotgun. Homer hops right into one gun barrel, then out the other, but the dog takes aim and fires, leading to an abrupt fade-out with the dog wearing a satisfied smile.

The final scene takes place nearby the hobo jungle, where the country dog stands at the edge of a cliff – and has decided to end it all. “Life ain’t worth livin’ without my Homer”, he states. Of course, anyone committing suicide in an Avery film is going to do it in the grand manner – meaning total overkill. The dog has a noose around his neck, with the other end tied to a tree. He holds a cocked pistol in each of his hands, each aimed point blank at his temples. And he stands atop a huge cartoon style black-ball bomb, with the fuse already lit. Before this quadruple tragedy can take place, Homer appears without explanation in the nick of time and snuffs out the fuse “Homer! Ya come back to me!”, says the happy dog, and offers his rear end for Homer to climb aboard. Homer whispers in his ear that there’s one proviso first, and, gesturing with his hands the shape of a girlish figure, presents his lady love, also rescued from the bulldog. The country dog smilingly approves the additional tenant. But wait – the provisos are not quite over, as the little lady whispers into Homer’s ear – ad the two march proudly up the dog’s tail, leading by the hand an endless row of baby fleas, all exact look-alikes to Homer, set to the Civil War tune, “Tramp, Tramp, Tramp the Boys are Marching”, for the iris out.

Pluto’s Purchase (Disney/RKO, Pluto, 7/9/48 – Charles Nichols, dir.) is a lively action-filled romp, with good expressive character animation a cut above typical late ‘40’s Pluto entries, both for the canine star and his arch-nemesis Butch the Bulldog. It also features a delightfully lively musical score from Oliver Wallace, coming up with a memorable low-register sax leitmotif for Butch’s sequences. Mickey (who cameos instead of starring) sends Pluto on an errand to the butcher shop to pick up a juicy sausage. Butch, living in a nearby junkyard, sees Pluto enter the shop, and hatches an idea to hijack Pluto’s bundle. He even goes so far as to signal the butcher through the window to select a larger sausage instead of a smaller one. As Pluto trots down the street, one of Butch’s ploys is to sift through his own fur and come up with a paw full of fleas (depicted rather realistically as hopping red dots). Hopping to the top of a fence, Butch “rolls” the fleas in his paw as if he were shooting dice, and tosses them onto Pluto. Pluto react in shock as the insects impact upon him, and goes into immediate conniption fits of scratching. Butch meanwhile substitutes a small girder in place of the sausage and makes off with the tasty treat, leaving Pluto to chomp down on cold steel. A well-timed battle of wits with several clever surprises ensues, climaxed by a wild chase through the streets (allowing Nichols to retread a few shots for the second time from Butch’s first appearance in Bone Trouble (1940)). Pluto arrives home a split second before Butch. Mickey is pleased at how fast a trip Pluto made, but announces that the sausage is a “birthday present for a friend of yours.” Trying to guess who, Pluto envisions the love of his life, Dinah the Dachshund. Mickey whistles for the intended recipient, and Pluto puckers up to greet “her” at the door – only to place a lip-smack on Butch, who smiles broadly with the sausage in his mouth. “Happy birthday, Butch!”, announces Mickey, as a distraught Pluto is left grumbling on the porch at all that trouble for nothing. (When originally telecast on the Mickey Mouse Club – one of the latest cartoons to be included in the package – Disney apparently had second thoughts about the gross angle of using the fleas as a weapon, and cut the flea sequence from the telecast – making the “fast trip” seem even faster!)

Pluto’s Purchase (Disney/RKO, Pluto, 7/9/48 – Charles Nichols, dir.) is a lively action-filled romp, with good expressive character animation a cut above typical late ‘40’s Pluto entries, both for the canine star and his arch-nemesis Butch the Bulldog. It also features a delightfully lively musical score from Oliver Wallace, coming up with a memorable low-register sax leitmotif for Butch’s sequences. Mickey (who cameos instead of starring) sends Pluto on an errand to the butcher shop to pick up a juicy sausage. Butch, living in a nearby junkyard, sees Pluto enter the shop, and hatches an idea to hijack Pluto’s bundle. He even goes so far as to signal the butcher through the window to select a larger sausage instead of a smaller one. As Pluto trots down the street, one of Butch’s ploys is to sift through his own fur and come up with a paw full of fleas (depicted rather realistically as hopping red dots). Hopping to the top of a fence, Butch “rolls” the fleas in his paw as if he were shooting dice, and tosses them onto Pluto. Pluto react in shock as the insects impact upon him, and goes into immediate conniption fits of scratching. Butch meanwhile substitutes a small girder in place of the sausage and makes off with the tasty treat, leaving Pluto to chomp down on cold steel. A well-timed battle of wits with several clever surprises ensues, climaxed by a wild chase through the streets (allowing Nichols to retread a few shots for the second time from Butch’s first appearance in Bone Trouble (1940)). Pluto arrives home a split second before Butch. Mickey is pleased at how fast a trip Pluto made, but announces that the sausage is a “birthday present for a friend of yours.” Trying to guess who, Pluto envisions the love of his life, Dinah the Dachshund. Mickey whistles for the intended recipient, and Pluto puckers up to greet “her” at the door – only to place a lip-smack on Butch, who smiles broadly with the sausage in his mouth. “Happy birthday, Butch!”, announces Mickey, as a distraught Pluto is left grumbling on the porch at all that trouble for nothing. (When originally telecast on the Mickey Mouse Club – one of the latest cartoons to be included in the package – Disney apparently had second thoughts about the gross angle of using the fleas as a weapon, and cut the flea sequence from the telecast – making the “fast trip” seem even faster!)

Barking Dogs Don’t Fite (Paramount/Famous, Popeye, 10/28/49, I. Sparber, dir.), a Technicolor reworking of Fleischer’s Protek the Weakerist (1937), involves Popeye’s embarrassment at being made by Olive to walk a small dog that Popeye considers a “sissy” – especially when rival Bluto comes by walking a ferocious bulldog, and the two bullies pick a fight just for the sheer fun of it. In the color remake, the dog is cast as “Frenchie”, a French poodle. A new gag us worked in on this theme, as Olive spritzes the pup from head to toe with perfume. Loud coughing is heard from within Frenchie’s fur, and a flea emerges gasping for air, says “Phooey”, packs a traveling suitcase and hits the road. The remake is a good one as Paramount remakes go, with several new gags, tighter timing, and a more exciting climax.

Original storyboard sketch of Frenchy and the flea from “Barking Dogs Don’t Fite” by Carl Meyer and Jack Mercer

from the Vince Cafarelli collection – via Michael Sporn’s Splog

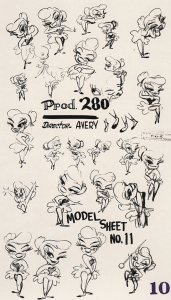

Tex Avery was not through with fleas by a long shot. Within a few short months of each other, he would give us a double-dose of buggy humor in 1954. The Flea Circus (MGM, 9/6/54 – Tex Avery, dir.), is for its time a unique take on the notion of performing insects, moving them up in the world from sideshow curiosity to legitimate theater. Pepito’s Cirque Des Fleas plays to sellout crouds at the Paree Theater, Pepito himself raking in the dough at the ticket booth while handing out magnifying glasses to the patrons. The program is not of standard circus acts, but all manner of other stage attractions. A microphone drops nearly to the stage floor to pick up the music of a 52 piece flea marching band. A team of flea acrobats pile atop each other’s sholders to form anything from a single-file tower to an outline in the shape of a sweet young lady. A tap dancer’s rendition of “Swanee River” is cut short when he falls through a crack in the floor. A sword swallower gulps down an entre human-sized sword which disappears from view – then hiccups. A concert pianist flea plays the “Unfinished Symphony” – which remains unfinished when he overshoots the end of the keyboard of a concert grand and falls into a spittoon. The only act that lays an egg is Francois the Clown (voiced by Bill Thompson), a flea who looks like a little big-headed human in full clown makeup and outfit, whose sour rendition of “Clementine” draws a unanimous reaction of disapproving eyebrow-drops as seem through the magnifying glasses of the observing patrons, who boo him off the stage. But now comes the most awaited act on the program, Fifi Le Flea. In her dressing room , a pampered female flea, who looks like a miniature human can-can dancer, primps herself befire a mirror in final preparation to go on stage. Observing her through another magniftung glass, Pepito calls her on stage, and compliments her at looking “gorgeous”. “You only tell Fifi this because it is so true”, she replies.

Tex Avery was not through with fleas by a long shot. Within a few short months of each other, he would give us a double-dose of buggy humor in 1954. The Flea Circus (MGM, 9/6/54 – Tex Avery, dir.), is for its time a unique take on the notion of performing insects, moving them up in the world from sideshow curiosity to legitimate theater. Pepito’s Cirque Des Fleas plays to sellout crouds at the Paree Theater, Pepito himself raking in the dough at the ticket booth while handing out magnifying glasses to the patrons. The program is not of standard circus acts, but all manner of other stage attractions. A microphone drops nearly to the stage floor to pick up the music of a 52 piece flea marching band. A team of flea acrobats pile atop each other’s sholders to form anything from a single-file tower to an outline in the shape of a sweet young lady. A tap dancer’s rendition of “Swanee River” is cut short when he falls through a crack in the floor. A sword swallower gulps down an entre human-sized sword which disappears from view – then hiccups. A concert pianist flea plays the “Unfinished Symphony” – which remains unfinished when he overshoots the end of the keyboard of a concert grand and falls into a spittoon. The only act that lays an egg is Francois the Clown (voiced by Bill Thompson), a flea who looks like a little big-headed human in full clown makeup and outfit, whose sour rendition of “Clementine” draws a unanimous reaction of disapproving eyebrow-drops as seem through the magnifying glasses of the observing patrons, who boo him off the stage. But now comes the most awaited act on the program, Fifi Le Flea. In her dressing room , a pampered female flea, who looks like a miniature human can-can dancer, primps herself befire a mirror in final preparation to go on stage. Observing her through another magniftung glass, Pepito calls her on stage, and compliments her at looking “gorgeous”. “You only tell Fifi this because it is so true”, she replies.

Francois appears, and is also gaga at the way Fifi looks. He lays down his coat to let her cross a few stray drops of water backstage – but this is not enough of a gesture to get her to accept his proposal of marriage, which Fifi refuses for the umpteenth time, “No, no NO!!” Fifi leads a massive troupe of nearly identical dancing girl fleas in a mammothly staged production number on an elaborate miniature set, “Applause, Applause” (The song, composed by Ira Gershwin, is borrowed from the obscure MGM musical, Give a Girl a Break, with Marge and Gower Champion – in fact, from audible comparison of the two films, I believe the rendition appearing in the cartoon is actually looped from a portion of the actual soundtrack of the feature as performed by the MGM chorus.) While the audiece’s eyes grow wide in appreciation through the magnifying glasses, no one seems to notice that the stage door has been left unattended, and a stray dog wanders into the theatre. The musical number cuts off abruptly, and the entire troupe gallops off stage, briefly forming into the letters, “Wow! A Dog!” The dog reacts in panic as the entire circus jumps onto his back – and resumes singing their song! He runs out the stage door into the night. Pepito stands in the stage doorway, pleading for them to come back, and facing ruination. But one flea has remained faithful – Francois. Francois promises to bring back more fleas to Pepito – somehow – and takes off in pursuit of the troupe. In a Parisian park, the dog finally finds a solution to his problem – a small lake, into which he jumps in. The soggy fleas all abandon ship – except for Fifi, who it seems can’t swim, and is about to go under with the dog’s tail. On the shore arrives Francois, who quickly dives into the water and drags Fifi to safety. Assuming it to be a meaningless gesture in Fifi’s eyes, Francois bids her a sad goodbye. Instead, she follows him on bended knees, and asks him to marry her. “Vive La France!”, Francois replies, and the scene endswith a heart-shaped iris out.

Francois appears, and is also gaga at the way Fifi looks. He lays down his coat to let her cross a few stray drops of water backstage – but this is not enough of a gesture to get her to accept his proposal of marriage, which Fifi refuses for the umpteenth time, “No, no NO!!” Fifi leads a massive troupe of nearly identical dancing girl fleas in a mammothly staged production number on an elaborate miniature set, “Applause, Applause” (The song, composed by Ira Gershwin, is borrowed from the obscure MGM musical, Give a Girl a Break, with Marge and Gower Champion – in fact, from audible comparison of the two films, I believe the rendition appearing in the cartoon is actually looped from a portion of the actual soundtrack of the feature as performed by the MGM chorus.) While the audiece’s eyes grow wide in appreciation through the magnifying glasses, no one seems to notice that the stage door has been left unattended, and a stray dog wanders into the theatre. The musical number cuts off abruptly, and the entire troupe gallops off stage, briefly forming into the letters, “Wow! A Dog!” The dog reacts in panic as the entire circus jumps onto his back – and resumes singing their song! He runs out the stage door into the night. Pepito stands in the stage doorway, pleading for them to come back, and facing ruination. But one flea has remained faithful – Francois. Francois promises to bring back more fleas to Pepito – somehow – and takes off in pursuit of the troupe. In a Parisian park, the dog finally finds a solution to his problem – a small lake, into which he jumps in. The soggy fleas all abandon ship – except for Fifi, who it seems can’t swim, and is about to go under with the dog’s tail. On the shore arrives Francois, who quickly dives into the water and drags Fifi to safety. Assuming it to be a meaningless gesture in Fifi’s eyes, Francois bids her a sad goodbye. Instead, she follows him on bended knees, and asks him to marry her. “Vive La France!”, Francois replies, and the scene endswith a heart-shaped iris out.

But that is far from the end of the story. A miniature wedding takes place at a full-sized church. Sometime later, Francois arrives home to find Fifi knitting a baby outfit with human-sized knitting needles Next comes the maternity ward, with Francois nervously pacing in the waiting room and puffing on full-sized cigarette butts left behind by other expectant fathers. A nurse brings in a basket of the new arrivals – a swarm of black dots that extend the width of the human-sized basket. (Someone was remembering Minnie Mouse’s maternity bed scene in Mickey’s Nightmare.) The happy family leave the hospital in a black swarm that covers the stairway. Arriving back at Pepito’s, they parade in in marching formation, ten times stronger in rank than the old marching band. The show goes on again, complete with the musical production number. As usual, the film ends with one additional Avery twist. At the conclusion of the performance, Francois goes into Fifi’s dressing room, and finds her working with the knitting needles again. “No, Fifi, No!”, says Francois. Fifi gently replies, in a voice signifying her acceptance that this may become a regular thing, “Francois, Vive La France.”

‘

Dixieland Droopy (MGM, Droopy, 12/4/54 – Tex Avery, dir.) is a slightly strange but still humorous outing for the mumbly little basset hound (often called a poodle), being Avery’s first venture into a new stylized and simplified design for his most famous creation. mirroring the flat style of competing studio UPA’s successes. Droopy is quite angular, shorter, and with more beady eyes than usual, with a jagged bolt of red hair.

He also receives an odd introduction, from a narrator who sounds like the standard-type announcer one would tend to hear on classical music stations, bent on inspiring the audience to the solemnity of music appreciation. Amidst stylized backgrounds of a city dump, Droopy is introduced as aspiring musical genius John Pettybone – with a single life’s aspiration – to conduct a Dixieland band in the Hollywood Bowl. But he has no orchestra – only a baton, and a raucous phonograph record of “Tiger Rag”. He finds a variety of persons who don’t appreciate Dixieland music – the first being the watchman of the junkyard, who boots him out, tossing his record after him. In search of a record player, Droopy visits various venues – the juke box of a posh eatery, an ice cream wagon using a record player to play its tune, an organ grinder (also fake with a record player inside), and a musical carousel. Every time he puts the record on, people and objects get the jitters. All end in the same result – Droopy is booted again, and just barely catches the flying record. Making a catch for the umpteenth time, Droopy sticks his tongue out at his latest pursuer – but trips over a rope, and smashes the record himself. But lo – there is still music playing. A nearby flea circus highlights its star attraction, Pee Wee Runt and his All Flea Dixieland Band. Pee Wee (a name nod to Capitol records artist Pee Wee Hunt, having recently charted with a Dixieland-flavored rendition of “O”), plays a spirited trumpet in red and white striped shirt and flat straw hat.

He also receives an odd introduction, from a narrator who sounds like the standard-type announcer one would tend to hear on classical music stations, bent on inspiring the audience to the solemnity of music appreciation. Amidst stylized backgrounds of a city dump, Droopy is introduced as aspiring musical genius John Pettybone – with a single life’s aspiration – to conduct a Dixieland band in the Hollywood Bowl. But he has no orchestra – only a baton, and a raucous phonograph record of “Tiger Rag”. He finds a variety of persons who don’t appreciate Dixieland music – the first being the watchman of the junkyard, who boots him out, tossing his record after him. In search of a record player, Droopy visits various venues – the juke box of a posh eatery, an ice cream wagon using a record player to play its tune, an organ grinder (also fake with a record player inside), and a musical carousel. Every time he puts the record on, people and objects get the jitters. All end in the same result – Droopy is booted again, and just barely catches the flying record. Making a catch for the umpteenth time, Droopy sticks his tongue out at his latest pursuer – but trips over a rope, and smashes the record himself. But lo – there is still music playing. A nearby flea circus highlights its star attraction, Pee Wee Runt and his All Flea Dixieland Band. Pee Wee (a name nod to Capitol records artist Pee Wee Hunt, having recently charted with a Dixieland-flavored rendition of “O”), plays a spirited trumpet in red and white striped shirt and flat straw hat.

The narrator plays an omniscient inspiration to Droopy, suggesting, “Fleas love dogs, you know. You could make beautiful music together. Droopy gallops into the tent, and hijacks the whole band. The second half of the film revolves around a wild vhase between Droopy and the flea circus owner, nicely punctuated by various changes of rhythm of the still-playing flea orchestra, interesting sound effect variations (playing inside of sewer pipes, in and out of revolving doors, etc.), and Droopy’s periodic giving the band the beat with “A one, and a two…” The chase takes an interesting pause when Droopy gets a brief chance to rest and tells the fleas, “Okay boys, take five.” The miniature insects hop off Droopy’s back and converge around some dropped cigarette butts, puffing on same and exchanging comments on their performance in speeded-up dialogue sounding like backstage chatter in the dressing rooms. The chase is on again, and finally ends when Droopy ducks into the door of a theatrical agent’s office – unfortunately including a sign reading, “No dog acts.” Seeing Droopy in his office in violation of his policy, the agent says, “I’ll give ya three to get outta here. A one…..A two….” The unseen fleas on Droopy’s back mistake this for their cue, and resume playing again. Seeing no performers, the agent jumps to the wrong conclusion. “A musical mutt! Dixieland without a band! Wow, what an act!” The final scene shows Droopy in all his glory, standing alone on the stage of the Hollywoof Bowl, vigorously waving his baton – and billed as “John Pettybone, Dog of Mystery”. The narrator states that no one will ever learn the secret of the music, and Pee Wee Runt will never tell. The camera zooms into extreme closeup in Droopy’s fur, panning to Pee Wee – who is in fact the narrator, concluding, “For you see, he, that flea, Pee Wee, is me, see?”

The narrator plays an omniscient inspiration to Droopy, suggesting, “Fleas love dogs, you know. You could make beautiful music together. Droopy gallops into the tent, and hijacks the whole band. The second half of the film revolves around a wild vhase between Droopy and the flea circus owner, nicely punctuated by various changes of rhythm of the still-playing flea orchestra, interesting sound effect variations (playing inside of sewer pipes, in and out of revolving doors, etc.), and Droopy’s periodic giving the band the beat with “A one, and a two…” The chase takes an interesting pause when Droopy gets a brief chance to rest and tells the fleas, “Okay boys, take five.” The miniature insects hop off Droopy’s back and converge around some dropped cigarette butts, puffing on same and exchanging comments on their performance in speeded-up dialogue sounding like backstage chatter in the dressing rooms. The chase is on again, and finally ends when Droopy ducks into the door of a theatrical agent’s office – unfortunately including a sign reading, “No dog acts.” Seeing Droopy in his office in violation of his policy, the agent says, “I’ll give ya three to get outta here. A one…..A two….” The unseen fleas on Droopy’s back mistake this for their cue, and resume playing again. Seeing no performers, the agent jumps to the wrong conclusion. “A musical mutt! Dixieland without a band! Wow, what an act!” The final scene shows Droopy in all his glory, standing alone on the stage of the Hollywoof Bowl, vigorously waving his baton – and billed as “John Pettybone, Dog of Mystery”. The narrator states that no one will ever learn the secret of the music, and Pee Wee Runt will never tell. The camera zooms into extreme closeup in Droopy’s fur, panning to Pee Wee – who is in fact the narrator, concluding, “For you see, he, that flea, Pee Wee, is me, see?”

A few production notes should also be mentioned concerning this film. Titles are presented on an actual spinning record, with a fake label on which the title is presented in stylized font directly resembling the real-life “Dixieland Jubilee” record company label. The film was also produced during a transitional period when MGM had not yet made the move to produce cartoons in widescreen Cinemascope. Instead, several Droopy titles appear to have been formatted to accommodate both standard 1:33 ratio and matted semi-widescreen projection in 1:85 ratio. Some sources say this cartoon was struck in prints intentionally formatted for both ratios – and it shows. If you watch the current 1:33 master print with 1:85 cropping, the framing is absolutely perfect for a widescreen presentation, and seems improved when seen this way. The other two titles which may have received the same treatment (the giveaway being a couple of vertical pans in the camerawork seemingly designed to keep key objects and characters within the center area of the screen) are Homesteader Droopy and Deputy Droopy – although cropping is a bit closer to the edges than comfortable in these other two outings, such that they seem a little crowded in the smaller screen area. So, although Avery left the studio before full widescreen production went into effect, and never received the opportunity for widescreen cartoons at Walter Lantz, this film represents the best opportunity to see what Avery could have done with the widescreen format had he chosen to remain in theatrical production just a little bit longer.

A few production notes should also be mentioned concerning this film. Titles are presented on an actual spinning record, with a fake label on which the title is presented in stylized font directly resembling the real-life “Dixieland Jubilee” record company label. The film was also produced during a transitional period when MGM had not yet made the move to produce cartoons in widescreen Cinemascope. Instead, several Droopy titles appear to have been formatted to accommodate both standard 1:33 ratio and matted semi-widescreen projection in 1:85 ratio. Some sources say this cartoon was struck in prints intentionally formatted for both ratios – and it shows. If you watch the current 1:33 master print with 1:85 cropping, the framing is absolutely perfect for a widescreen presentation, and seems improved when seen this way. The other two titles which may have received the same treatment (the giveaway being a couple of vertical pans in the camerawork seemingly designed to keep key objects and characters within the center area of the screen) are Homesteader Droopy and Deputy Droopy – although cropping is a bit closer to the edges than comfortable in these other two outings, such that they seem a little crowded in the smaller screen area. So, although Avery left the studio before full widescreen production went into effect, and never received the opportunity for widescreen cartoons at Walter Lantz, this film represents the best opportunity to see what Avery could have done with the widescreen format had he chosen to remain in theatrical production just a little bit longer.

Next Week: we begin to explore the strange and longstanding romance of writer Michael Maltese with nature’s little bloodsuckers.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Charles Gardner is an animation enthusiast who toils by day as a member of LA Law – but by nights and weekends indulges in classic jazz and ragtime as a performer; and studies classic Hollywood cartoons… maybe a little too much.

Those production notes on “Dixieland Droopy” are very interesting. I wouldn’t have noticed that on my own and am grateful to have it brought to my attention.

“Food Around the Corner” is very similar to the verse of the 19th-century song “Darling Nelly Gray”. The first phrase of the melody is identical, and the harmonic scheme matches it perfectly.

Avery’s “The Flea Circus” seems to have inspired the song “Fifi the Flea”, recorded in 1966 by the Hollies. In the song, however, Fifi’s romance with the clown has a tragic ending.

The narrator of “Dixieland Droopy” was John Brown, an actor perhaps best known for playing the friendly undertaker “Digger” O’Dell in the radio comedy “The Life of Riley”. As with the narration, he played the role with an exaggerated sense of solemnity for comic effect.

I’m a little surprised that you omitted “Yankee Doodle Donkey” (Famous/Paramount, Noveltoons, 27/11/44 — I. Sparber, dir.), Spunky’s first cartoon without his mother Hunky. Spunky longs to join the “WAGs”, the army’s canine corps; but in basic training, his braying and ability to walk past a fire hydrant without stopping tip the drill sergeant off that this long-eared recruit is no dog. Before the sergeant can throw him out, a message comes in: “Flea Army advancing.” Soon the tiny bloodsuckers, marching in military formation, besiege the WAGs’ base. The dogs take cover in a “flea raid shelter”, and Spunky takes the brunt of their charge; but when the fleas bite into his flesh, they recoil in disgust. “Ugh! Horse meat!” Spunky fends off their attacks with well-placed donkey kicks, and when he finds some barrels marked “Flea powder”, he kicks them into the enemy’s midst. The fleas flee, and Spunky earns his place as a valued member of the regiment.

“Yankee Doodle Donkey” illustrates a fact of nature that most of these cartoons get wrong. By and large fleas are host-specific parasites, subsisting on just one or a limited number of mammal or bird species. (A notable exception is the Oriental rat flea, the primary vector of bubonic plague, which can apparently afflict any terrestrial mammal.) While dog fleas may bite humans (or donkeys), they cannot subsist upon us. So Seneca’s dictum “Qui cum canibus concumbunt cum pulicibus surgent [He who lies down with dogs gets up with fleas]” is true only metaphorically.

Good catch! I’ve only watched “Yankee Doodle Donkey” a couple of times, and I forgot it had anything to do with dogs.

I believe “What Price Fleadom” was Avery’s only MGM cartoon to use a character from a previous director. Is anyone aware of any others?

Unless you count that little boy in UNCLE TOM’S CABANA as an update of Bosko – I’d say no.

Chaplin played with fleas a few times.

In 1919, he made a short film in which he traded his little tramp character for a ratty music hall performer, Professor Bosco. The professor checks into a flophouse with his flea circus:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UszTZfp_LMg

He revisited the basic gags in 1952 with “Limelight”, in which he played a faded old-school comedian:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mbtaCWTUm6A

The 1919 film was an unreleased experiment, and “Limelight” came too late to influence theatrical cartoon makers. But interesting.

In “Curtain Razor” (Warner Bros., Looney Tunes, 21/5/49 — I. Freleng, dir.), talent agent Porky Pig is auditioning a variety of performing acts. A shaggy sheepdog hands him a business card reading “Itch and Scratch Flea Circus”. When the dog blows a whistle, the fleas jump out of his fur and set up a tiny circus tent and carnival midway; when he blows the whistle again, they dismantle it — all to the tune of the Wackyland “Rubber Band” music from “Dough for the Do-Do”, released earlier that month.

Bob Clampett was fond of telling the story of how he fessed up to a woman he became serious about that he directed animated cartoons. She said, “My favorite song comes from an animated cartoon. It’s called ‘There’s Food Around The Corner.'” Bob said, “I wrote that song.” Sody said, “Then I am marrying you.” Love that story.

Some excellent cartoon research here, Charles, thanks for the post. One point of interest is that the song “Food Around the Corner” was composed by Clampett himself then turned into a workable song in close collaboration with Carl Stalling, and he was always proud of it. Somewhere in my storage I have a document showing that Bob copyrighted the little song (found when I was doing archival research in the WB Collection at USC back in 2004). I’ll try to dig it out.

A quick search on the ASCAP clearance repertory lists that song with a specific work ID besides Stalling’s score. Because Bob doesn’t have his ASCAP profile and “Food Around the Corner” doesn’t have an ISWC work code assigned unlike Stalling’s score, Stalling would be the only one getting his royalty payment from this song. The story doesn’t tell if Carl shared his revenue with Bob out of generosity.

I have been unable to find “Patriotic Pooches” (Terrytoons/Fox, Gandy Goose, 7/4/42 — Connie Rasinski, dir.) on the Internet, but according to the summary on IMDb: “Answering a call for dogs to contribute to the war effort and join the “W.O.O.F.S.”, a small white puppy falls in with the others at a training facility manned by Gandy and Sourpuss. To clean them up, Gandy removes their fleas with a vacuum cleaner labeled ‘Flea Internment Camp’.” So it seems this cartoon has a place on the “Toons Abhor a Vacuum” Animation Trail as well as this one.

Because my family had friends who had spent the war years at an internment camp for Japanese-Americans in the Arizona desert, this joke, like the “Concentration Camp” gag from “Cat Meets Mouse” (released in the same year), doesn’t exactly tickle my funny bone.