Animators, regardless of technique–whether it’s cel animation, stop-motion, or computer-generated—are the actors that create the performances that brings to life the characters on-screen to tell the story. Having a firm understanding of the fundamental principles of animation—timing, key movement techniques (such as squashing and stretching the characters), staging, follow through and overlapping action, arcs, secondary actions, etc.—are a prerequisite for any great animator. Extreme patience is another for those working in stop-motion. Stop-motion animators are a special breed in that there is a common thread that runs through many of them—most became fans of the techniques at an early age.

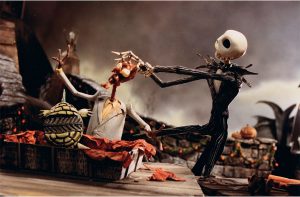

In preparing for this massive undertaking of The Nightmare Before Christmas, Henry Selick and animation supervisor Eric Leighton realized early on that the technical aspects of the animation would have to be superior to anything that had been done before. They knew that for audiences to sit through a seventy-five-minute stop-motion feature film, the normal “chattering” of images that had been associated with cheap and ineffective stop-motion animation in the past would have to be eliminated. And they were determined to make the character movements smoother than ever. The goal was also to devote the necessary time, talent, and resources to exceed even their own expectations and advance the art of stop-motion to unprecedented new standards of excellence.

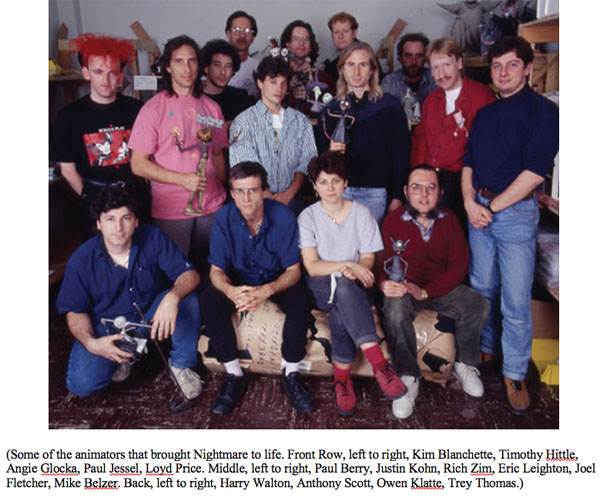

In all, fourteen animators were the core group that animated the entire film. There were five other animators who are credited with additional animation on the film; these were freelancers that were brought in to help with ancillary scenes. The core team of animators being supervised by Leighton were Trey Thomas, Tim Hittle, Michael Belzer, Anthony Scott, Owen Klatte, Angie Glocka, Justin Kohn, Paul Berry, Joel Fletcher, Kim Blanchette, Loyd Price, Richard Zimmerman, and Stephen “Buck” Buckley.

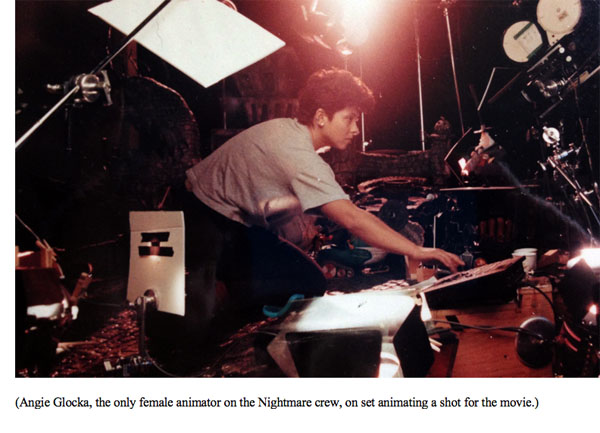

Angie Glocka was the only female animator on the Nightmare team. “There were no women doing what I was doing in stop-motion,” said Glocka. “There are a lot of reasons for that, partly because you have to be good in the shop.” Stop-motion animation requires the use of a lot of equipment, from cameras and lighting to building rigs necessary to achieve some animation. It requires an interest in construction. “We have to use a lot of nuts and bolts, screwdrivers, power tools; I built half the rigs that we used,” said Glocka. “I always did that kind of thing. I used to help my dad a lot, and I always liked that kind of thing.” Glocka was entering an area of animation that had been traditionally dominated by men, but that was changing culturally. “Luckily, the people in charge were interested in promoting women, but they couldn’t find anyone. Henry [Selick], of course, was always so fair-minded. I don’t think it would’ve crossed his mind to not hire someone because they were female.” No matter the gender, there was a great comradery among the entire production team.

The process of animating a stop-motion scene from start to finish requires numerous steps to get the final scene or shot on-screen. It starts with the scene being issued by the director, Selick, usually in editorial. Why editorial? It allows the animator to see the scene they will be animating as storyboard panels in continuity with the other scenes around it. This is viewed in the work reel, which is made up of scenes in various stages of the process from storyboard panels, to posed scenes, to the completed animation. This gives the animator an opportunity to ask questions and get a clear understanding of what the director wants the scene to look like, how the characters should be acting, and the context in which the scene fits into the sequence.

Every animator has their own way of working, but many will make notations on the exposure sheet (x-sheet), including doing some loose thumbnail drawings. Some animators like Leighton do extensive notes and drawings all over the x-sheet. In discussing his x-sheets for the Oogie Boogie sequence, Leighton said, “I’ve got all of the poses of Oogie Boogie dancing and spinning around and all that stuff. I mean, it’s exactly what’s in the movie.” Conversely, other animators approached it differently. “I don’t thumbnail much; sometimes I’d just ask Henry [Selick] for a drawing—what’s the pose you’re looking for—and he’d quickly draw me up a sketch and I’d have something to refer to,” said Scott. A common practice in animation is to use live-action reference, which was used in many early animated films, including Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937).

Because of the x-sheets, live action wasn’t utilized as much on Nightmare, though there were a few cases of it. “I videotaped myself with a VHS camera to show what the action is for Jack in the ‘Poor Jack’ song,” said Scott. But live-action reference was rare on Nightmare, as most of the animators did some degree of thumbnails and notes on the x-sheets. This included the dialogue breakdown by track reader Dan Mason and the puppet-head replacement guide for the animators.

The reason for doing such extensive notes and thumbnails is so that, when the stop-motion animation is being done, there is no room for mistakes. The goal is to not have any retakes in stop-motion because of the expense to redo a scene. The animator starts with frame one and goes to the next and the next, shooting each frame of the character once it has been adjusted or moved slightly. “Straight ahead all the way to the end of the scene,” said Leighton. “It’s called ‘straight-ahead’ animation. And it’s kind of a mind-numbing way to work.”

At the time that Nightmare was being made, the technology was such that the animator could only see three frames at a time: the frame that was being shot and the two preceding frames that had just been shot using the frame grabber, as discussed earlier. With contemporary stop-motion films, the animator can see much more, typically the entire scene, and if necessary can back up ten or fifteen frames if they have decided that they are starting to veer off on the wrong path. They can make the fix and correct it.

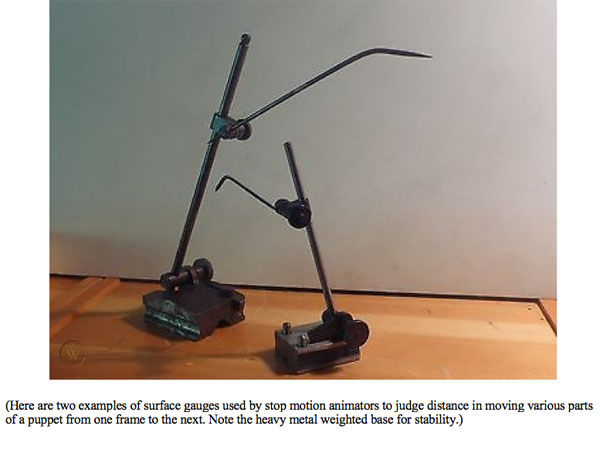

“Technology for the first time has gone through a major change in stop-motion animation with the advent of video assist,” said Leighton. “Now, an animator that’s doing high-end stop-motion work can have a running record of their entire scene as they go through their shot. So, they always know where they’re at, what they’ve done.” It is still straight-ahead animation, but the animator can do corrections, and they don’t have to keep everything in their head. The old way of doing stop-motion (the way that it was done from the inception of the art form, like the way it was done on the original King Kong) was that there was no video assist at all. The animator basically had to have everything in their mind, and they used what are called “surface gauges.” For Nightmare, animators used the frame grabber, but also found the surface gauges useful.

Surface gauges are essentially machinist’s gauges that allow the animator to have a point in space to use as a reference. The gauge itself is a big heavy weight that has a vertical pole sticking up that can be oriented, and on top of that there is another horizontal pole, which is also adjustable. With the surface gauges, the animator can pretty much find any point in 3-D space and know where the puppet is and where it needs to be moved to for the next frame. The surface gauge is used to reference where the puppet was so that the animator can set the pose for the next frame. If you bump the surface gauge, the shot is lost because you don’t know where you were. Think of the surface gauge as a marker showing where the various parts of the puppet pose are on a frame that was shot, and then the animator adjusts the puppet to create the next successive pose.

When animating straight-ahead, the animator is not just dealing with the center of gravity of the character. They are doing everything: moving the hips forward, easing a limb in, or easing it out—depending on whether they’re accelerating or decelerating at that point in the character’s action or stride; then should the hips move sideways, maybe twist them a little bit or rotate them down as they take the weight on that hip; then counter-animate the character all the way up the spine. There are so many things to keep track of on the stop-motion puppets that are being animated that it takes an immense amount of concentration and focus: hip, knee, ankle, toes, the shoulders, the arms, and the head. If there are replacement faces, take one off, put another back on. Imagine all those steps the animator must go through for each frame as they move the animation forward. “The biggest advance on this film,” said Leighton, “is the human effort. Even with the new technology and tools that we’re using here, it still comes down to the time and labor that the animators put into their work and the level of acting and technical smoothness that makes this film so special.”

Before the animators set out to do a complete scene, they did what are known as “pop-throughs” to make sure the scene was what the director wanted. A pop-through is the equivalent of a pose test in 2-D or 3-D animation, where the key poses of the character are shot on film to check the choreography of the action. It’s called a pop-through because the character is not fully animated but rather “pops” through the intended path action of the scene to make sure that the character is starting and ending within the length of the scene and that the action will hookup to the adjoining scenes. On Nightmare, each scene might have gone through several pop-through pose tests before approval was given by Selick for the scene to be fully animated. “The pop-through took one or two days, a very quick, basic version of the shot. The full animated shot could take a week or more, so you wanted to make sure that you got the performance worked out ahead of time,” said animator Joel Fletcher. “And then you’d review that with Henry [Selick], and if there are any major changes, you might do another pop-through, but generally he was fine with maybe the exception of a few changes that would be incorporated into the actual final shot or another pop-through.”

These pop-through rehearsals are usually done twice, depending on the complexity of the shot. The first one would be kind of a camera-blocking pass, where the character puppet was positioned on every twelfth frame. The animator would work with the camera operator to make sure that the camera angles, camera lens, and the lighting were correct. Once that first blocking pass, pop-through was shot, it was cut into the film in editorial and the animator would have a discussion with Selick about the performance, the lensing, the lighting, and how that related to the surrounding scenes in the reel. The animator then took those notes and did a second pop-through in a more detailed test that some of the animators referred to as a run-through.

Depending on the animator, the second test might be shot every two frames or four frames per second—or a mix based on what the animator needed to get the information needed to shoot the final scene with confidence. That second pose test was more fluid, and once it was shot would be cut into the reel to watch in continuity with Selick for the final notes. Then the animator would shoot the final scene. “It’s kind of like getting on a tightrope and walking across and not falling off,” said Scott.

“One of the hardest things to do in animation, in my opinion, is capture lightning in a bottle,” said Leighton. “That moment of energy of inspiration or passion or excitement that only comes in a moment, to take that and carry it through a whole process where you can tend to massage and massage and adjust; and by the end, you’ve lost it.” The preplanning for Leighton was an advantage for him as an animator. He could have days where he shot three hundred to four hundred frames of a scene, which was due to the proper preplanning. For Leighton, it is like doing a theatrical performance—once the curtain goes up you just had to shoot; once you start, you can’t stop. “You have to stay in the zone, and stay focused going through it. I think that not everybody had that. Everybody had their own way of working. So, this was just my own peculiar way of working.”

Thomas, an animator who had worked with Selick and Leighton on commercials, was an early addition to the animation ranks on Nightmare. He came on after the proof of concept was approved and the film was put into production. Thomas’s first shot was of the tiny little train in Christmas Town, with Jack riding on top of it as it goes around the mountain till he jumps off, sleds down, comes running over a hill in the foreground, then smacks into the Christmas Town sign, and falls backwards into the snow, sinking down until he disappears leaving only a silhouetted impression. “Epic, epic first shot. It was crazy. It was totally insane,” said Thomas. Although this first shot for him involved Jack, Thomas was primarily animating Sally on the film, though he also did some of Oogie Boogie and Lock, Shock, and Barrel in “Kidnap the Sandy Claws.”

It is typical in animation that characters are cast to the strengths of the animators. So, on most animated films, there are character leads—those animators that define a particular character. Although there were no leads credited on Nightmare, except for Leighton (who was the animation supervisor), various animators were known for certain characters: Thomas for his Sally animation; Leighton for his spectacular Oogie Boogie performance, along with Klatte, Belzer, and Berry; and Scott for the Jack animation during the “Poor Jack” song.

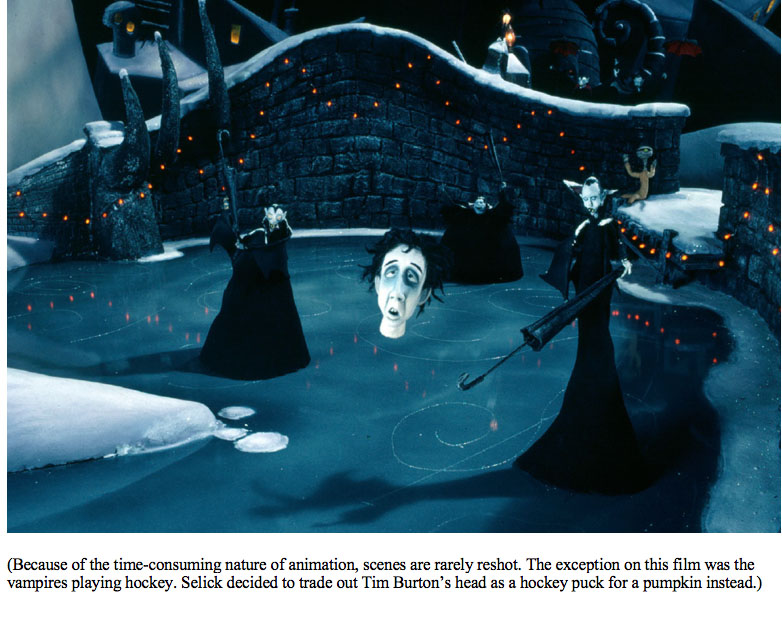

Despite all of the animators’ care in setting up—and their attention to the animation itself—they did have one scene that they ultimately reshot. When Christmas comes to Halloween Town, the vampires are playing hockey with a head as a puck. One of the vampires hits the head right into camera, revealing that it is Tim Burton’s head. When the shot was completed, Selick hesitated in showing it to Burton. “I said, ‘I don’t know. Tim [Burton] might [be] upset.’ So, that’s one of the reshoots,” said Selick. “And I never knew if [it did]. I wish I could’ve gotten him on the phone and asked, ‘Tim, is this a funny thing, or are you going to be pissed?’ I wish I could’ve done that because it would’ve been nice to know either way.” That was one of the few scenes reshot. Tim Burton confirmed—all these years later—that he did in fact know about the shot: “I wasn’t offended, because I understand animators’ aggression and pent-up anger.”

The animation staff, Selick, and the production management team would review dailies in the mornings. The dailies were screenings of the fresh animation shots that were just completed and back from the film lab. Each scene of animation would be looped and viewed repeatedly while being discussed and critiqued. “We tested everything at least once. There was always a camera test, lighting, a pop-through,” said Selick. The animators sat in the back two rows of the theater and Selick sat down in the middle. “Henry Selick has one of the most brilliant minds in stop-motion animation, very bright and articulate. So, he would always speak first, and he didn’t always know if you were in the theater or not because it was dark,” said Buckley.

The atmosphere was always very intense. Selick demanded greatness, and wanted each animator to deliver that “because when you did what he directed, he loved you; but let him down, go off-script, and do it your own way . . .” said Buckley. “For the animators, getting Selick’s approval was paramount. He wanted the best—and if the animators delivered they were golden in his eyes. It was all about producing great animation.”

Animation is a very solitary occupation. An animator is thinking about what the performance is that he is going to create regardless of the technique—2-D, CG, cut paper, whatever—it’s all about creating the animation. In stop-motion, it is that moment which is a combination of energy, inspiration, passion, and excitement that only comes in an instance after all the planning, thumbnails, pop-throughs and pose tests. And when the animator gets it right—it is like capturing lightning in a bottle.

Text ©2021 David Bossert

Portions of this article have been extracted from the author’s book, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas Visual Companion, (Disney Editions, June

2019,2020, 2021?). All footnote attributions are noted in the book.

“What a pleasure it is to be transported back in time by author Dave Bossert and given this fascinating, hands-on ride through the making of Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas. With meticulous attention to detail combined with an incredible amount of research, Bossert’s passion for our little movie shines brightly as he adroitly shares our creation story with the reader. It is a joy, and an honor, to see this beautifully-documented and insightful book, as it reveals the commitment of our close-knit crew to elevating the art of stop-motion and crafting the timeless story of Sally and Jack.”

—Eric Leighton, Animation Supervisor, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

As always, a cogent explanation of the technical aspects of animation production. Question: What exactly do you mean by “the normal ‘chattering’ of images” in stop-motion animation, and can you give some examples?

The “normal chattering of images” can be seen in early examples of stop motion animation like the original King Kong (1933) where the viewer can see uneven, “chattering” movement. Compare that to the smoothness of the animation in more contemporary stop motion films like Coraline (2009) or Kubo and the Two Strings. The advent of video assist, use of gauges, and newer frame capture software have allowed for much more refined animation movement, which gives the overall action more believability and draws the audience more fully into the film. Thank you for reading, -Dave

Just my usual uneducated assumptions, but I was thinking that what would be considered as “abnormal chattering” in stop motion would be that kind of static moveent that you see in 2-D animation in a classic Terrytoons cartoon where the characters’ heads or faces seem to be off model or slightly larger or the movement has a kind of “tick” instead of the movement being more fluid, the way a graceful person moves in simple action. Sometimes, that kind of static or “chatter” could be done on purpose to illustrate unearthly fear or an impending morphing of one character into something different. Tjhank you for this article. I never had the opportunity to actual see this film, but I enjoyed it on my own level when I saw it in a theater upon its official release.

(Kevin, that don’t make no sense. You never got to see the film but you did see it when it was released?)

I’m glad to see a detailed, if short, of how this sort of video assisted animation is done. I had my own notion of what it entailed, but this fills in some gaps. I’m still confused about the gauges. How do you keep a gauge in a spot where it can be useful without it being photographed?

The whole business of “chattering” simply means the visible effect of relying on your own intuition on how far you have to move a model from frame to frame, using guesswork rather that measuring things and without the ability to compare one pose to another. That’s why something like the old Rudolph TV specials comes off a bit jittery especially in more complicated movements such as characters walking. Not that this doesn’t have its own aesthetic. But I agree, for a whole feature you need to get a cleaner sort of movement to keep the viewer engaged.

Hi Peter, The gauges are used when moving the puppet to the next position. Then the gauges are removed and the frame exposed, the process then repeats. The gauge allows the animator to have a reference as to where the puppet or part of the puppet was and how much to move to the next frame. Some animators may use several gauges for positioning. I hope that helps to clarify the process a bit more. Thanks for reading, -Dave