During WWII, Germany, Japan and the United States all engaged in disseminating propaganda to the masses. In Nazi Germany, Hitler had Joseph Geobbels, head of the propaganda ministry, create messaging using broadcast radio, printed materials along with threats and violence to “soften up” and unite the populations in neighboring countries the Nazis wanted to annex. In Japan, the military used movies and animation to portray the Americans as the devil, harnessing the animation industry to turn out propaganda cartoons that played to the masses in theaters across Japan.

In the United States, the War Department and other government agencies also used film, animation as well as printed materials as propaganda to support the war effort. In Hollywood the First Motion Picture Unit, later known as the 18th AFF Base Unit, was headquartered at the Hal Roach Studios in Culver City. It was known as Fort Roach. They produced more that 400 propaganda and training films both as live action and animated productions.

In Burbank, The Walt Disney Studios turned out more than 200 live action and animated productions encompassing Public Service Announcements (PSA), training films and propaganda shorts, most notably Education for Death (1943), Der Fuehrer’s Face (1943), Reason and Emotion (1943) and Chicken Little (1943). The contracts that Disney received from the military and other government agencies during the war helped to keep the studio afloat financially and made up for the film revenue lost as the war raged in Europe.

Aside from film and animation productions, the Disney studios also created countless individual images used for print and other applications. Most notable of these were the military insignia, which I have written about in Hank Porter: Disney’s Go-To Artist for Insignia Designs during WWII. But there were other images created at the studio from Victory Garden signage to training manual illustrations and other print media that are less well known. These used unique cartoon images and some of the studios most popular characters like Donald Duck.

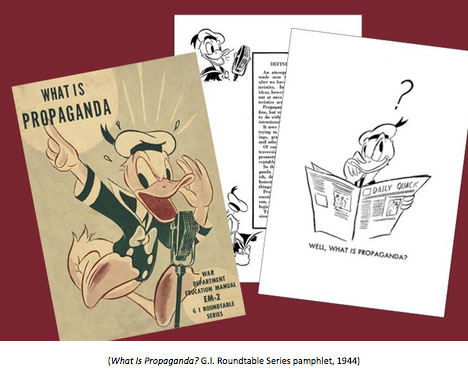

One pamphlet, What Is Propaganda?, was produced in 1944 by the War Department and written by Ralph D. Casey for The American Historical Association as part of a program of publications called the G.I. Roundtable Series. These were generally 40 to 50 page softbound booklets on various topics that included: What Shall Be Done with War Criminals?, Do You Want Your Wife to Work After the War?, Can We Prevent Future Wars? and many others. The pamphlets were created towards the end of the war and distributed to help in the transition to a postwar world. They also represented an effort by the U.S. Government at social control through the use of propaganda. Of all the booklets published, What Is Propaganda? is the only one that uses Donald Duck as a sort of spokesman for asking the question of what exactly is propaganda.

The pamphlet attempts to answer that question through written text accompanied by still cartoon drawings. The short answer in defining it is, “propaganda isn’t an easy thing to define, but most students agree that it has to do with any ideas or beliefs that are intentionally propagated.” It goes on to state, “it uses words or word substitutes in trying to reach a goal—pictures, drawings, graphs, exhibits, parades, songs and other devices. Of course propaganda is used in controversial matters, but it is also used in generally acceptable and noncontroversial.1”

In essence, anything that promotes a specific point of view or supports an ideology is propaganda. “So there are different kinds of propaganda. They run all the way from selfish, deceitful, and subversive effort to honest and aboveboard promotion of things that are good” We are bombarded daily by propaganda messages in advertising telling us, as the Rolling Stones sang, “When I’m watching my TV; And a man comes on and tells me, How white my shirts can be, Well he can’t be a man cause he doesn’t smoke, The same cigarettes as me.2”

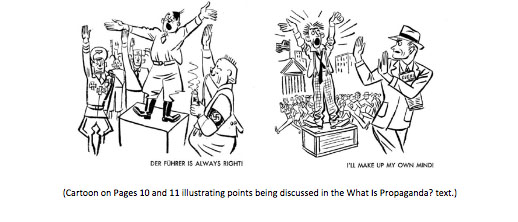

What Is Propaganda? is itself a propaganda publication as it was produced with the sole purpose of portraying the enemy in a bad light. The text opens with a scenario in the spring of 1940 in which the French allied armies are facing the Germans. “There is little action at the front, and a group of French soldiers find time to listen to an enemy broadcast. “Where are the English?” asks the radio voice. The broadcaster is speaking in French. The soldiers listen uneasily. “I’ll tell you where your English comrades are,” continues the voice. “They lounge in Paris and fill the night clubs. Have you seen a Tommy on the Maginot Line? Of course not. French soldiers, you will find the Tommies behind the lines—with your wives.3” The Nazis were using radio propaganda in an attempt to divide the Allies, create suspicion and doubt the reliability and faithfulness of the their commitment to the French. The pamphlet gives a number of other hypothetical scenarios to illustrate Nazi propaganda and the entire text is a fascinating and convincing read.

As he did throughout the war effort, Walt Disney gave away countless illustrations of his characters for various use. In this instance, Donald Duck is used on the cover illustration and inside of the front and back covers indicating that he is asking the question, What Is Propaganda? The illustrations are solidly on model with clear silhouetted poses that convey the desired action. I have not been able to discover exactly who did the drawings of Donald Duck or the cartoons spotted throughout the text for this publication. It is certainly possible that the small unit of Hank Porter, Roy Williams, George Goepper and Van Kaufman may have produced the artwork as they were dedicated to handling the insignia and other non-animation related requests that inundated the studio during the war years. I have no doubt that that there were many of these little projects that flew in and out of the studio quickly. These types of images of Donald Duck could have been drawn in an afternoon by nearly any capable artist at the studio before they moved onto their next assignment.

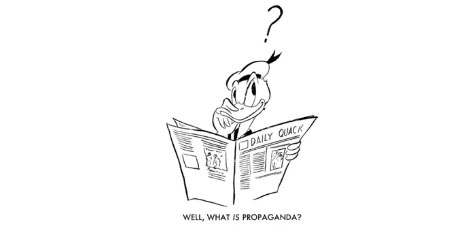

The last image at the end of the pamphlet is the rhetorical question, “well, What Is Propaganda?, which the reader should now be able to answer.

This little gem of a pamphlet is a timeless piece of history and is as relevant in today’s political climate as it was when it was first published. When I first got a copy of it, I was amazed at how well the text resonated with the type of rhetoric espoused by elected officials and candidates today, not just in America but in other countries as well. The tools of propaganda such as suggestion, hints, insinuations, indirect statements and advertising are all on display daily. The distribution channels for these messages have changed and expanded since WWII but the tools and techniques of propaganda certainly feel the same.

What Is Propaganda? reprints are available here.

Footnotes

1- What Is Propaganda? War Department Educational Manual, EM-2, G.I. Roundtable Series, 1944.

2- (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, Rolling Stones, genius.com/The-rolling-stones-i-cant-get-no-satisfaction-lyrics

3- What Is Propaganda? War Department Educational Manual, EM-2, G.I. Roundtable Series, 1944.

©David A. Bossert

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

The last image in this pamphlet with Donald reading a newspaper looks like a pose commonly used by Al Taliaferro in his newspaper strips, although the linework doesn’t look like his.

These pictures of Donald remind me of the first time I ever saw the word “propaganda”, in a joke in Boys’ Life magazine: “What is propaganda? A socially correct male duck.” I didn’t get it.

Wouldn’t that be a “propamallard”?

😀

More like a “propadrake”, but let’s not propagate any malapropisms.

I think that meant “a socially correct male goose” (propaganda = gander).

Please excuse the digression. This was an interesting post, and it sounds as though the booklet is worth reading. However, I’m put off by the $9.95 asking price. Not that it’s exorbitant, it’s just that I don’t like having to pay money for something the government used to give away for free.

Paul, you have to realize that the government gave these to the G.I.’s as part of ongoing education. It has been out of print since WWII ended, some 75 years ago. The ones available through the link above are reprints that cost money to make. It is a nominal amount for a reproduced historical pamphlet.- Dave

You’re right, of course publishers have to meet their costs like any business. Now that so many fascinating historical documents are accessible online, I suppose it’s easy to become spoiled. I’m glad you’ve written about this pamphlet for Cartoon Research readers like me who otherwise might never have learned of it. But for those of us living outside the US, unfavourable exchange rates, bank fees, and international shipping charges can make even a “nominal” price balloon to unreasonable proportions.