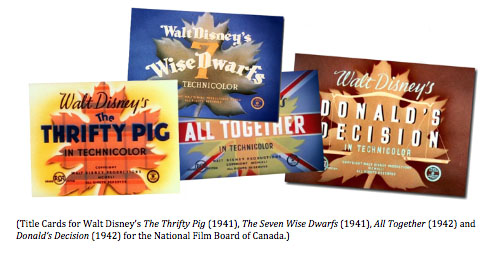

As the United States plunged into World War II (WWII) after the Japanese bombed the U.S. Pacific Fleet at the Peral Harbor Naval Base in Hawaii on December 7, 1941, Walt Disney Productions in Burbank, California, had already been creating educational films to support the war effort for Canada (1). The studio had completed and released The Thrifty Pig (11.19.1941) for the National Film Board of Canada and was in production on The Seven Wise Dwarfs (12.12.1941), Donald’s Decision (1.11.1942) and All Together (1.13.1942) (2) to help the Canadian government sell war bonds to their citizens to finance Canada’s efforts as part of Commonwealth of the United Kingdom (3), which had already entered the war in 1939. Walt Disney saw it as a necessity to produce a manual for the animation staff, especially after his studio was declared a “defense plant (4),” that documented some of the time and cost saving methods for producing animated and live action films quickly and efficiently.

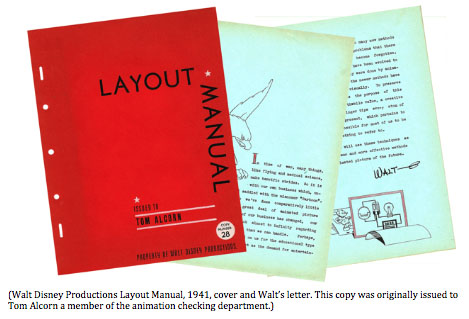

In what was called the LAYOUT MANUAL, Walt Disney added an introductory letter explaining his philosophy and purpose for the manual stating, “In time of war, many things, like flying and medical science, make terrific strides. So it is with our business which, unfortunately, is still saddled with the misnomer “Cartoon.” It is clear that Walt chaffed at the idea his studio was turning out mere cartoons, which implied a less important role in the film industry. He goes on to say, “In the last year or so we’ve done comparatively little “cartoon” work, but a great deal of animated picture work.” Walt is elevating the animation art form to a higher level by referring to it as “animated picture work” and hence instilling a moniker of respectability he feels their work deserves. He continues, “The Technique of our business has changed, our horizons have rolled back almost to infinity regarding the educational material that we can handle. Perhaps, in the future, the demand on us for the educational type of film will be as important as the demand for entertainment alone.” (5) This passage gives the sense of importance that Walt bestows on creating educational films using animated techniques as he brings them to the same level as the entertainment films the studio had produced up to that point.

Walt Disney was in Washington D.C. on January 7, 1942, a month after the U.S. entered WWII, meeting with Military personnel. Pictured (L to R) Colonel George J. B. Fisher, Colonel Maurice E. Barker and Walt.

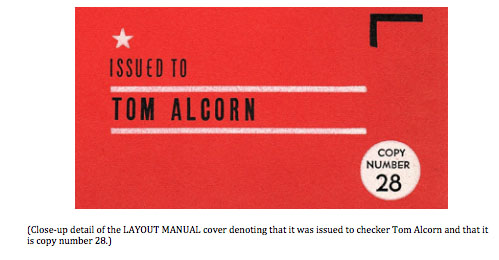

Many of the techniques and methods developed at Walt Disney Productions were proprietary to the studio, which dictated that the manuals be distributed numbered and with the artists name printed on the cover. The author has copy number 28, which was issued to Tom Alcorn, a checker at the studio. He was also a member of Walt Disney’s extended family on his wife’s side. Alcorn married into the Bound’s family and worked at the studio on and off for many years. By 1965, he was listed as being in the camera department.(7)

Walt then ends his message with, “Shrewd, creative men will use these techniques as foundations for newer and more effective methods of creating the animated picture of the future.” (8) Ever the optimist, Walt was always thinking ahead to the future and what it might bring in animation advancements. It is also worth pointing out the use of the term “creative men” a sign of the societal norms of that time period even though there is much documentation and recent research that shows many woman had taken on important roles at the studio during WWII.

Following Walt Disney’s message at the head of the LAYOUT MANUAL, there is a one page preface that goes into more detail regarding the contents and use of the manual. The preface begins, “The examples in this manual are given merely to illustrate certain uses of the facilities which we have at our command. With judgment, imagination, and ingenuity, these principles can be adapted to innumerable uses.” The meat of the page is the second paragraph that states, “In recording and illustrating them, it was not the intention to suggest that these are the only ways to get a particular effect; nor, even, in the event two versions are given, that one is better than the other. Either, or both, may be uneconomical, if not in the layout man’s time—then, perhaps in checking, ink and paint, or camera time—and ALL functions and their costs MUST be considered by the layout man.” Upon reading this, one might get a real sense that it was written by Walt’s brother Roy O. Disney, who handled the business side of the studio, since the emphasis is on being cost conscious. The preface continues, “Saving his own time laying out a scene that calls for a highly complicated and, consequently, costly shooting, is not economy. Nor is it good economy to put in large amounts of his own time in order to achieve a trick effect in an unimportant scene. Consider: Are ripples on the water necessary? Must those trees animate? Do they add to the PURPOSE of the scenes? Can a sliding cel take the place of animation? Will it be more economical in checking and shooting time to use the 11-Field camera in place of the Multiplane circular disc?” Although there is no signature on the preface, if not Roy O. Disney it was likely a production management or department head that wrote this message as a way of getting the artists to think strategically. Often times artists in one discipline are only focused on what they are doing and not necessarily thinking about how their work will impact other departments after them. Asking those questions was critical to maintaining the “good economy” that the studio was attempting to achieve on the tight budgets that were inherent in making the training films.

The preface ends with, “COST—PER—FOOT [CPF] is a horrid phrase but it’s got to be put up with, like hot spells and taxes. The suggestions in this manual should help keep old man CPF where he belongs—and still maintain the Disney quality which is our most vital asset.” Succinctly stated, the age-old battle between art and business—of maintaining the economic efficiency while still protecting the Disney Studios greatest asset, quality. It is a constant tug-of-war between artistry and budgets, even in today’s computer generated animated films. But, it was imperative that all aspects of the animation production process operate at the utmost financial efficiencies since in most cases the Disney Studios was being paid “without profit” to produce many of the war related, government funded films on small budgets.(9)

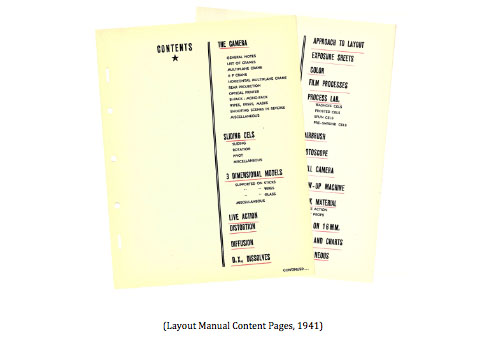

After the preface statement, there are two index pages which outline the contents of the LAYOUT MANUAL. The manual is really a guide to camera techniques, layout methods, live action/3-dimensional models and visual effects. It begins with THE CAMERA section indicating general notes, list of [camera] cranes, multiplane crane, II F crane, horizontal multiplane crane, rear projection, optical printer, Bi-Pack—Mono-Pack, wipes, irises, masks, shooting scenes in reverse and miscellaneous. The next section is SLIDING CELS which covers sliding, rotation, pivot and miscellaneous techniques. This is followed by 3 DIMENSIONAL MODELS covering supported on a stick, supported on wires, supported on glass and miscellaneous. There is a section each on LIVE ACTION, DISTORTION, DIFFUSION, D.X.[double-exposures], DISSOLVES, APPROACH TO LAYOUT, EXPOSURE SHEETS, COLOR, FILM PROCESSES, PROCESS LAB which covered wash-off cels, frosted cels, spun cels and pre-shrunk cels, AIRBRUSH, ROTOSCOPE, STILL CAMERA, BLOW-UP MACHINE, STOCK MATERIAL including live action and art props, NOTES ON 16 MM., TABLES AND CHARTS and finally MISCELLANEOUS.(10)

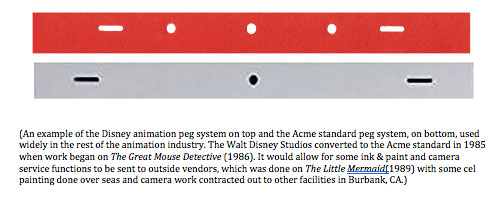

It is worth noting that the LAYOUT MANUAL is printed on punched animation paper, which is likely the result of saving costs. Each page in the manual has an oblong peg hole on either side of three round holes centered on the left vertical side of the paper. This peg hole configuration was the Disney Studios proprietary peg system and was used up until the mid-1980s before the studio switched over to the industry standard Acme peg system that consisted of one round peg hole with an oblong peg hole on either side. The manual appears to have had some updates added to it during the war years as evidenced by typed information on strips of paper taped on to specific pages within the manual. (11)

The next installment in this series of articles on the LAYOUT MANUAL will delve into the analysis of THE CAMERA section. Camera is one of the most important functions of the animation process because without it, how would audiences be able to view the films. The animated scenes that make up a film come together as the finished visuals in the camera department where the painted cels, backgrounds and special effects, both drawn and optical, all meld together into the final film.

©David Bossert 2019

FOOTNOTES

1 – Ian Westwell and Donald Sommerville, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of World Wars I & II An Authoritative Account

of Two Of The Deadliest Conflicts In Human History With Details Of Decisive Battles And Engagements; Hermes

House, an imprint of Anness Publishing Ltd, 2019, pg. 326.

2 – Shale, Richard Allen, Donald Duck Joins Up: The Walt Disney Studios During World War II, The University of

Michigan, Ph.D., 1976, Appendix B, page 287.

3 – W. David McIntyre, 1999, “The Commonwealth”; in Robin Winks (ed.), The Oxford History of the British Empire:

Volume V: Historiography, Oxford University Press, p. 558

4 – David Lesjak, Service with Character (Theme Park Press, 2014), pg. 7

5– Walt Disney’s opening letter, Layout Manual, Walt Disney Productions, 1943; authors copy.

6 – Walt Disney’s opening letter, Layout Manual, Walt Disney Productions, 1943; authors copy.

7– Individual job title listed and additional information courtesy Joe Campana, some sourced from Los Angeles County Voter Registration.

8 – Preface, Layout Manual, Walt Disney Productions, 1943; authors copy.

9 – Shale, Richard Allen, Donald Duck Joins Up: The Walt Disney Studios During World War II, The University of Michigan, Ph.D., 1976, p. 63.

10 – Contents index pages, Layout Manual, Walt Disney Productions, 1943; authors copy.

11 – Evidenced by the actual pages in the Layout Manual, Walt Disney Productions, 1943; authors copy.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

I think it’s wonderful that you have this reference today. A compendium of the technical aspects of animated filmmaking as they existed in 1943 must be of enormous interest to students of film history.

Out of curiosity, just how long is the Layout Manual — how many pages? And is each sheet of animation paper printed on both sides or, as in animation, is only one side used?

Hi Paul,

I am still scanning the manual and there are no page numbers. My guess is that there is about 90 to 100 pages. There are in fact all printed on one side of the punched animation bond paper. It is a wonderful reference and I am continuing to write about it.

Thanks for reading the piece,

-Dave

Great post, David.

Thank you!

I am guessing that, aside from the short films that showed up on the WALT DISNEY TREASURES collection volume dedicated to those films done for and around the war effort, there are still many such films that could be released or haven’t been seen since their production in the day? Are any of these films very hard to find, now, save for private collectors? I must echo; great post, Dave.

Hi Kevin,

Yes, there are plenty of films that were made by Disney that they do not have copies of in their film library. Some because they were classified and others that just were lost with time. I have been tracking down many and will continue to do so as I continue to write about them. At some point I will be posting them on my YouTube channel for those interested in seeing them.

Thank you for reading and glad you enjoyed it. More to come.

Best,

-Dave