A Message From Steve: “It’s a little less Thunderbean this week and a lot more Cartoons on Film! I’ll be back next week, but this week Tommy Stathes steps in while I work on getting a film to final cleanup tonight!

A new a pre-order is available at the Thunderbean Shop.

It’s Harman/Ising Rarities – a Blu-ray set we’ve been working on already for a little while.

Have a good week all! Tommy, take it away…”

– Steve Stanchfield

Dear Cartoon Researchers: Your regularly scheduled dose of Thunderbean Thursdays is being postponed until next week! A little bird has told me Steve Stanchfield is very busy working on a special rush project (see box above) this week. Therefore, he’s turning today’s slot over to Cartoons On Film.

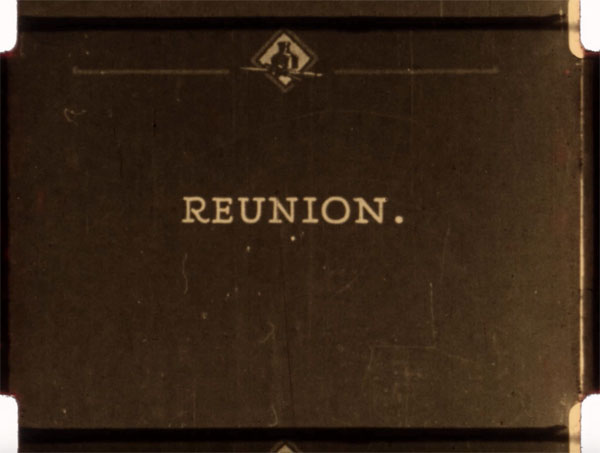

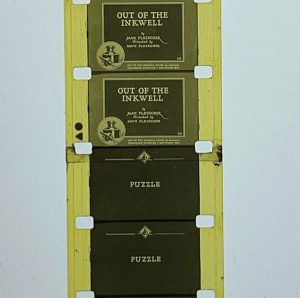

In keeping with the usual Thunderbean Thursdays spirit, I’d like to give you a behind-the-scenes look at one of the films that I currently have in the restoration pipeline. Earlier this year, some readers may recall that I had been crowdfunding two new Cartoon Roots Blu-ray/DVD releases — featuring Walter Lantz’s silent-era Bray cartoons such as Dinky Doodle, as well as some of Fleischer’s early Out of the Inkwell shorts [LINK]. What I’ll share here today is the curious story of one of the Inkwell shorts: Reunion (1922).

If one thing is true of most silent era cartoons, it’s that many of them are quite rare. Many hundreds of them are still considered lost! By ‘lost,’ film historians and archivists usually wish to imply that there are no copies of a particular film known to exist among most institutional archives, or among most well-known private collections. However, the situation happens to be a bit more optimistic than that, in my view. Copies of previously rare, and even ‘lost’ films do turn up from time to time—whether they be chance finds at flea markets or in innumerous basements and attics and barns throughout the world, or even simply as previously-misidentified or unidentified prints that already exist in dedicated film collections.

A lot of my work relies on coming across more and more of these prints. What’s more, my restoration work often relies on using multiple prints of the same film—whenever possible. It’s a difficult, but necessary task to use multiple prints, as so many of these early films had been edited or physically damaged over the years. That brings us back to Reunion (1922).

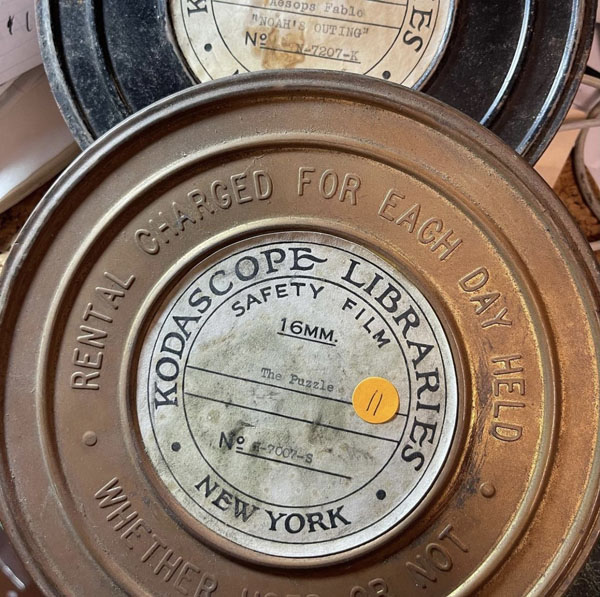

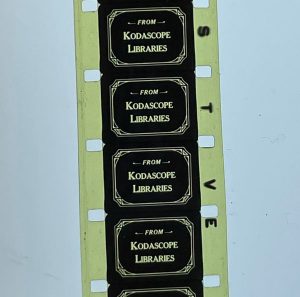

Sadly, 35mm elements no longer exist for many of these cartoons. The main element I’ve had to work with for this particular restoration, so far, has been my own tinted 16mm Kodascope print, which was struck in 1927. This Kodascope print, while visually charming, has a few physical splices in the print which obliterate the flow of some shots. In a situation like this, I’d normally seek out another print of similar vintage and provenance. Sadly, I’ve had difficulties accessing another one.

Before I go any further, I’ll share a bit about the story behind Kodascope prints. Back in the 1920s, the 16mm film gauge was growing in popularity—it was far more portable and inexpensive to use, in comparison with 35mm film, and this made it an ideal format for average consumers. Finally, filmmaking was becoming more accessible to the masses!

By 1924 or so, and in response to this new trend, the Eastman Kodak company founded a rental library called Kodascope Libraries. Kodascope aimed to provide consumers with licensed prints of famous theatrical films, and educational shorts—all of which could now be shown in someone’s home. This was true, so long as prospective borrowers had the space and money to either buy or rent a 16mm film projector, and the wherewithal to rent prints for showing at home. Schools, churches, libraries, and other organizations would also partake in these rentals. Simple put, 35mm projection was more cumbersome, more expensive, and often dangerous, if nitrate film was being used for presentations. The answer to this problem was 16mm film.

The incredible thing about the Kodascope Libraries prints is that they were printed from 35mm negatives. The resulting quality was stunningly sharp. Quite a few silent era cartoons were given this Kodascope treatment, and that includes a handful of the Inkwell shorts. These prints are somewhat rare, and sometimes they are quite worn when they turn up. They’re now almost a hundred years old. That’s why my print has a few problems.

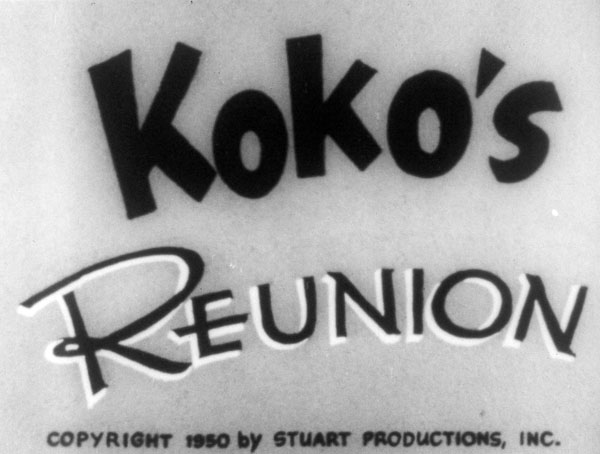

Thankfully, I do have a secondary element to work with in this Reunion restoration project. Beginning in 1950, a firm called Stuart Productions optioned some of the old Out of the Inkwell films for television distribution. After all, television was a fairly new medium and not a lot of new programming was available for syndication at the time. Old cartoon material like this was suitable for use in hosted kiddie shows. One such example was “Uncle Fred” Sayles’ Junior Frolics, which was seen by countless thousands of children here in the New York City area from about 1948 to the early or mid 1950s. Or, sometimes these kinds of old cartoons were used as generic time slot fillers. We owe a lot to the distributors who wound up repackaging these old films for television, as sometimes these 1950s versions are now the only surviving prints of otherwise lost early silent cartoons.

What’s the problem, then? Stuart Productions completely replaced all of the original main and end titles, as you can see above. What’s more, all of the intertitles were also excised for these new TV printings. That leaves us with versions of these films that only contain the original cartoon or live action footage, sans all of the on-screen explanations or written dialogue. That’s okay, though—I already had those elements in the old Kodascope print! Problem solved. Or so I thought.

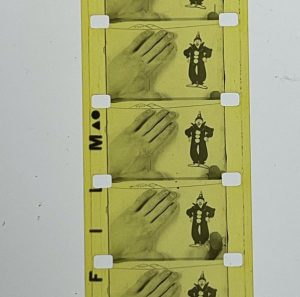

Some readers might have surmised by now that compositing both prints together would be a simple and straightforward task. Not so much the case, as my trusty editor David Grauman soon discovered. Dave recently started to compare both prints in digital post-production, and he then began cutting together a new composited version for me to review before cleanup could begin. Since the Kodascope had a few physical splices in the print, all I thought was needed would be little bits of replacement footage from the secondary print, in order to fill in whatever was lost to the physical splices in my original Kodascope print. Below, you’ll see an example of one of the physical splices in question. Watch for the splice in the close-up shot of Max Fleischer handling a toy car, and you’ll see a very noticeable skip in the action.

Here’s where it gets even more interesting. During the editing process, Dave found that many of the shots in the Kodascope negative were actually shorter than they should have been. Quite a few frames were missing at the beginnings and ends of some shots, and sometimes in the middle of certain shots. These cuts were seamless in the resulting release print. I suspect what happened was that Kodascope’s 35mm dupe negative was simply cut differently from another master element. Or, Kodascope’s negative may simply have become shortened over time, in a more organic way, from simple wear and tear. The cuts don’t appear in the picture area of the resulting print because these would have been very discreet, and very well made lab splices.

In any case, the TV version seems to have been prepared from a superior, and more complete master element that may have even predated Kodascope’s own circa 1924 35mm negative. Perhaps the original camera negative, or a master positive was used. This means the TV version wound up having more frames from many shots, and that was a complete surprise to me. I had no clue some of this footage was even missing! The only downside here is that the TV print is a bit soft, giving an overall look that isn’t as sharp or as generally superior as the Kodascope happens to be. This is the sort of conundrum I’m coming up against constantly, in my restoration work.

In any case, the TV version seems to have been prepared from a superior, and more complete master element that may have even predated Kodascope’s own circa 1924 35mm negative. Perhaps the original camera negative, or a master positive was used. This means the TV version wound up having more frames from many shots, and that was a complete surprise to me. I had no clue some of this footage was even missing! The only downside here is that the TV print is a bit soft, giving an overall look that isn’t as sharp or as generally superior as the Kodascope happens to be. This is the sort of conundrum I’m coming up against constantly, in my restoration work.

I do happen to know of another very good condition Kodascope print of Reunion in a private collection. Sadly, the other Kodascope print remains inaccessible because of the owner’s rather difficult nature. If I’d been able to access that alternate Kodascope print, it could have made this particular restoration just a little bit easier and more uniform—we would have been able to ‘borrow’ less footage from the TV print, for one thing.

Have a look at some of the composited footage, in our new rough cut. The amber tinted footage is the 1927 Kodascope print, and the more pleasing ‘master’ element in this project. The softer, flatter looking black and white frames are the new bits that have been taken from the TV version, and inserted back into our new edit. A great big thanks goes out to David Grauman again, for his fine work on this.

Now that this new final edit of Reunion has been made, the softer TV print footage will be digitally tweaked in post production, in order to more closely match its overall look with the better-looking Kodascope footage. Then, all of the footage will be steadied and cleaned up. Whew. While the restoration work is still underway, a new musical score has just now been recorded for this film by a very esteemed silent film accompanist. That’s all I’m at liberty to say about this and other projects, for today!

As a final note, I do want to mention that I’m currently doing a bit of fundraising for my 16mm Cartoon Carnival series. We were finally able to resume screenings here in New York City this summer, safe and socially distanced in a Brooklyn backyard space. However, more than a year’s worth of event income had been lost because of necessary lockdowns. The proceeds from these shows directly cover the cost of maintaining my film print archive in off-site storage, and losing that income turned out to be a terrible financial burden for me, and subsequently a great risk to the films in storage. Some friends and colleagues have asked how they could help get this itinerant film screening series back and track, which would also help cover the cost of archival storage. As a result, I’ve set up a GoFundMe campaign for this purpose. I’m grateful to everyone who has chipped in so far, and a thanks in advance to any readers who might be able to chip in!

In any case, stay tuned for more news about my various ongoing silent cartoon restoration projects…and in the meantime, let’s enjoy the return of Thunderbean Thursdays, next week.

Tommy Stathes is an animation historian specializing in silent era cartoons. He resides in New York and frequently holds public screenings throughout the city. You can read more about his work, his collection and his research on his website:

Tommy Stathes is an animation historian specializing in silent era cartoons. He resides in New York and frequently holds public screenings throughout the city. You can read more about his work, his collection and his research on his website:

These clips prove that little details can make a huge difference. Without those few frames of film showing Koko stepping back from the hole in the wall, there’s no sense of flow between the two scenes. Thanks for this glimpse into what’s involved in restoring a century-old cartoon. I’m proud to have your Cartoon Roots sets in my collection, and I look forward to getting the ones I’ve pre-ordered, but by all means take your time and do it right!

I found some online reminiscences of “Uncle Fred Sayles’s Junior Frolics”. It aired on Channel 13 out of Newark, New Jersey, from 1949 to 1958, and then under a different title until 1960. Uncle Fred had a library of some 300 cartoons, which took about six or seven weeks to go all the way through. The silent ones, which including not only Koko but also Farmer Al Falfa and Bobby Bumps, he narrated in the manner of a Japanese benshi. Many former viewers have vivid memories of “The Sunshine Makers”, which seems to have been shown very frequently. Perhaps Borden’s sponsored the show?

Thanks, Paul! I appreciate your kind words. Re: Junior Frolics, I think it’s safe to say that wasn’t a Borden’s sponsored show. By this point, that film was simply being reprinted and reused as generic cartoon filler…

It’s my understand that many silent live-action features were edited for length in the Kodascope library. Is it possible that cartoons were also trimmed to bring them to a uniform length?

Good point! While that was certainly done with the features, generally speaking, that wasn’t really the case with the cartoons. Kodascope seems to have left the <1-reel subjects alone in that regard. One exception is the fact that Kodak did cut some of these shorts down tomuch shorter uniform lengths (i.e. from 200-300ft down to 100ft), and sold them outright on the home movie market under the "Kodak Cinegraph" label. The 'cutdown' version issue, with regard to the cartoons, is different from the problem I was describing with the Kodascope negative.

Thanks for your post, Tommy. I love this kind of stuff!

I’ve got a question about silent films that has always perplexed me. I’ve heard that many silent films (if not most, or all of them) were filmed at 16 frames per second. Is this true? Is that why Charlie Chaplin’s silent films look so sped up? (Though I have to say, most of the time the sped up action helps rather than hurts.) I’ve noticed when some animated characters run in silent cartoons that the scene doesn’t look quite right. I first figured it was because the animators hadn’t quite figured out how to draw a figure running. But maybe it doesn’t look right because the film is going too fast?

Is there a difference between the two prints of the above cartoon because the early one was printed when film speeds were 16 fps, and the later one was printed after films speeds had changed to 24 fps? And did the latter have to add frames for the 30 fps of TV?

On a similar note… when 24 fps of films is converted to the 30 fps of TV you have to double every fourth frame, right? However, I’ve noticed when I click frame-by-frame on some animation DVD/Blu-rays that there is no doubling of every fourth frame. How do they get away with that? Can DVD/Blu-ray players play a 24 fps film correctly, without having to add the 6 doubled frames per second?

This might be better explained by someone (either you, or Steve, or Jerry, or whoever) in a separate post, but this question has been bedeviling me for a long time, and I would be eternally grateful if I could get an answer!

Anyway… thanks for all your hard work, Tommy! Can’t wait to see the fruits of your labors!

I may not be the best person to answer this, so if someone else chimes in and corrects me, believe them instead. But since no one else has chimed in yet and I know enough to be slightly dangerous …

(1) The frame speed of film wasn’t standardized until sound came along and required it. It was up to the camera operator what speed he wanted to film it, and up to the projectionist what speed he wanted to project it. If there was fast wacky action happening, it was fairly common practice to undercrank the camera (ie slow down the frame speed) so the fast wacky action would be even faster and wackier when it was projected.

(2) No. With a few rare exceptions, films intended for TV use ran at 24 fps, just like all the other sound film out there. And that includes the sound versions of the Koko cartoons. It was up to the broadcast equipment to get 30 fps (or 29.97 fps for color) out of the film. In the early days of film chains (basically just a projector beaming a projector into a modified TV camera), the film frames ended up just kind of blurred together. Since you couldn’t freeze frame TV back then, nobody noticed or cared. It was good enough.

The syndicators weren’t all that concerned about whether 24 fps was the correct projection speed when they added sound to silent films. They just wanted something they could sell. The missing frames are missing from the Kodascope print because somebody snipped them out at some point.

(3) Oh it’s WAY more complicated than that. Standard definition broadcast video wasn’t JUST 29.97 FPS, but each frame consisted of two fields – the odd lines and the even lines. With a proper 3-2 pulldown, the frame changes often happened on the fields, so it was (usually) 3 fields and 2 fields, not 4 frames and 1 frame, which would have been a lot jerkier. If you accidentally run interlaced video as uninterlaced, you wind up with frequent frames that have combing – a zig-zaggy pattern – because the even lines are from one frame of the film, and the odd lines are from another. If you’re running interlaced video on a non-interlaced screen (which is all of them nowadays), there’s a computer chip in the TV that smooths out the jaggies, a process called deinterlacing. Now, understand that we’re talking standard definition here. Film scans haven’t been done as interlaced in years.

Your DVDs and BluRays are most likely encoded with actual 24 fps digital video that matches the film, which is why you don’t see repeated frames. There aren’t any. Aside from making cleaner frames and smoother motion, it also saves room on the discs. Some monitors can play 24 fps, others will convert it in the monitor to whatever frame rate the screen wants. (The DVD or BluRay player may be converting the frame rate for you as well. Consult your owner’s manuals for more confusion.) There are some elderly DVDs that *do* have interlaced 29.97 fps video made from a 24 fps film, and you will see repeated, and probably interlaced, frames on those if you go frame by frame. (But some players will even deinterlace the still frames!)

Thanks as always for your kindness, support, and friendship, Dan! I really appreciate it. And a big thanks to Herr Graf for clearing up some of the mystery behind frame rates and video fields.

In short, the discrepancy with regard to lengths is an issue that really relates only to physically cutting footage, as opposed to the question of frame rates and whatever speeds the printers might have been running at. Since film prints themselves rely on a frame-by-frame sequencing of images, the issue of printing or projection speeds doesn’t really factor into how complete or incomplete a film may be. It’s really only the physical cutting of frames or footage that makes such a dent…

Tommy:

Great work! You’re carrying on the tradition of film restoration of silent films from the likes of the late David Shepard to guys like Steve Stanchfield. It’s so easy for younger audiences to say, “Awww, who cares?” – regarding vintage silent films, let alone silent cartoons. I’m glad you do!

Several years ago, I got to see PETER PAN played at CINEVENT at the Ohio State University’s theater with a small four – piece orchestra. The film was wonderful – particularly because the film had recently been restored and was scored as close as possible to what audiences might have seen and heard in c. 1924! that’s what you guys are trying to do, and I don’t think enough people appreciate the effort!

Thanks a bunch, Leonard! There really is nothing like seeing these films on the big screen. While I’m more than thrilled to be producing these restorations and putting out new Blu-rays with them, it would be so wonderful to get us all together inside one humongous palace theater and enjoy the new restorations on a gargantuan silver screen. We can dream, can’t we?

In any case, I’ll continue doing what I can to further all this…and I really appreciate your support. Much appreciated.

No new Thunderbean Thursday for the first day of Autumn, 2021. I need my fix!

Hi Tommy! Wonderful work! One of these days I hope we can get you to Los Angeles for a big screen show!