Once The Walt Disney Studios project in Burbank, California, was completed and the artists had moved into their offices there was a period of adjustment to the new digs. The modern facility was at the opposite end of the spectrum in space and comfort to the old Hyperion Avenue studio in Silver Lake. Some of the artists complained that it was too sterile and that it lacked the ramshackle quality they were used to at Hyperion.

Weber designed Animation Desk, Lower UNIT No.1 with upper UNIT No.2; illustration ©MBP

Other employees felt marginalized and distant from the boss, Walt Disney. Animator Jack Bradbury recalled, “when we went to the new studio, we went from a room that we had worked in with several guys to rooms all by ourselves, with drapes on the windows, carpeting all over the floor, a nice easy chair to sit in…. It was cold, you didn’t know who the boss was….” This was clearly a reaction to the changes that were happening at the studio after the massive success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. It was also indicative of a growing enterprise and the unintended consequences that often accompany growth and great accomplishments.

Whether the move to the new studio exacerbated already simmering labor unrest at the studio is up for debate. But, just a few years into the new studio in May 1941 there was the pivotal animation strike that left Walt emotionally wounded and bitter towards certain individuals who he blamed for the walkout. The homey ramshackle environment of the Hyperion studio was gone forever and a new era dawned for the Disney empire.

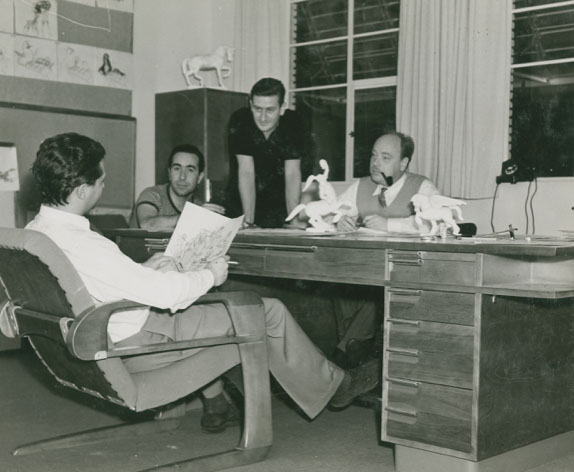

Joe Grant (seated in a fabric covered Air Line chair in the foreground) at a large director’s desk opposite Dick Huemer (with pipe) with character designer James Bodrero standing and Dunbar “Dun” Roman seated to the left looking at camera during production of Fantasia (1940). Note the drawer details and open cubby on the right side. Also, Grant is resting one foot on the ubiquitous chrome pipe footrest under the center of the desk.; circa 1940. Photo by Baskerville. ©UCSB

Walt Disney granted Kem Weber permission to bring a photographer named Baskerville into the newly completed studio complex to shoot photos of his designs, often while in use by the artists and other employees. It was typical of designers and architects to get beauty shots of their design handiwork to update portfolios with recent accomplishments to show perspective new clients. Weber also organized an exhibition of his drawings, paintings and photographs of the Disney Studio project at the then new University of Santa Barbara campus, where he would eventually leave his archives.

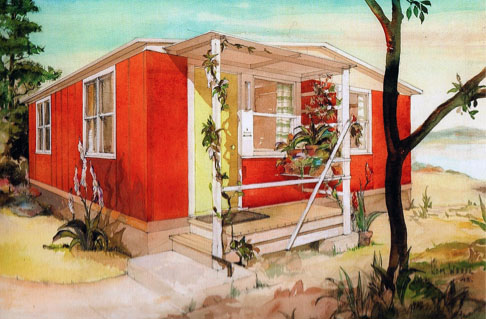

After Weber completed his work for Disney he went onto do a redesign of the Bismarck Hotel in Chicago where he continued to push forward his version of the Streamline modern aesthetic. He also worked on a design and prototype for a prefab house in association with the Douglas Fir Plywood Association in Tacoma, Washington, for the US Government. With the country gearing up for eventual entry into WWII, the Federal Housing Administration was looking for proposals on prefabricated homes to house workers near defense plants. Weber embraced the use of plywood for furniture and home construction. Once again showing that he was on the leading edge of new manufacturing methods and building techniques.

A perspective sketch of the Kem Weber System House, his prefabricated housing unit; pencil and watercolor on board by Kem Weber, 1942; ©UCSB

During the war years, Weber tried numerous times to get traction on his prefab home designs but was only met with empty promises, delays and frustration. It’s possible that his German heritage and accent may have hobbled his opportunities as he had experienced “fervent anti-Germanism during the First World War” when he first arrived in the United States in 1914. Regardless, Weber continued to design furnishings and structures after WWII ended and into the 1950s. He worked on homes, retail stores, hotels and gas station designs in Southern California and around the continental United States. But by 1957, Weber was looking to slow down. His children had grown and he spent more time with his grandchildren, sailing off the coast of Santa Barbara and painting in his studio. In 1959, Weber began displaying signs of Alzheimer’s disease that progress quickly. His family put him in a retirement home in the fall of 1962. Kem Weber passed away four months later on January 31, 1963 at the age of 73.

Although Weber was largely forgotten by the time of his death, he left a legacy of iconic designs that have, in the last decade or so, been rediscovered as well as his importance in the mid-century design period. His regular home furniture pieces are very collectable, as are his designs for the specialty animation furniture for the Disney studios, and command hefty prices.

Kem Weber, 1889-1960 ©UCSB

Looking back, Weber more than delivered on the studio plant that Walt Disney had envisioned for his burgeoning company in 1939. He created a showcase of the new design aesthetic that was emerging during the mid-Twentieth Century. Although architectural design has evolved, through often radical style changes, since then, the Disney studios in Burbank remains a prime example of not just California Streamline style but of International style as well. This is evident by the inspired designs seen in contemporary architecture today, including structure and furnishings at Disney resort properties around the world and commercial buildings at the Celebration community in Orlando, Florida and elsewhere. His timeless designs of the Air Line chair and the modular Disney animation furniture have galvanized Weber’s place in design history. It’s only in recent years that Weber’s legacy has taken root for the genius he was in innovative industrial and architectural designs that helped to defined mid-century modernism.

There are many more stories associated with the Disney animation furniture in my latest book, Kem Weber: Mid-Century Furniture Designs for the Disney Studios. Included are concept paintings of early designs, photos and interviews with some of the animation legends that worked on these desks.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

Leave a Reply