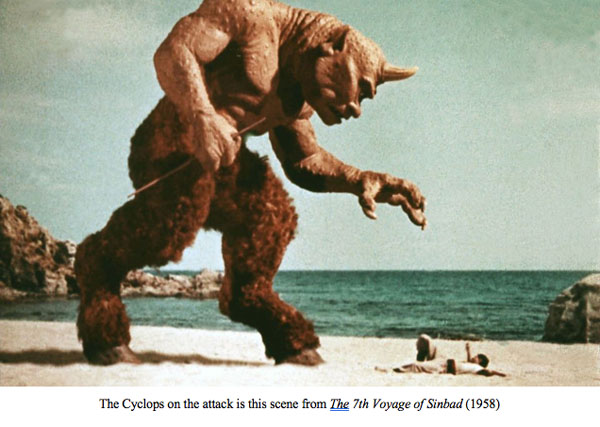

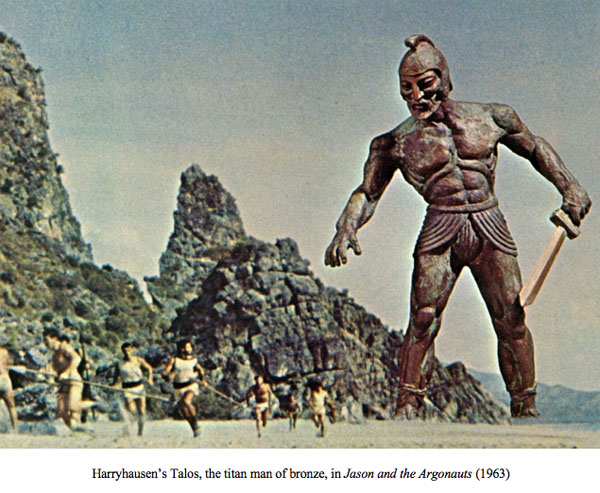

The commonality among most great film raconteurs is their early love of the movies. Those seminal moments in a dark movie theater where their imaginations were captivated by the screen images playing before their very eyes: the “gee-whiz, how’d they do that” moments when fantasy and reality blend, creating a sense of awe and wonder. For a young Tim Burton, and many of the artists who worked on The Nightmare Before Christmas, some of those key inspirational moments came from the American-British visual effects designer Ray Harryhausen and the stop-motion animation of fantastical creatures he created for special effects–oriented fantasy films like The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Jason and the Argonauts (1963). “Growing up with Ray Harryhausen, that kind of stop-motion was a very, very strong thing,” reminisced Burton during a conversation we had in Los Angeles in 2017. As an animation technique, the stop-motion genre includes anything that requires a physical inanimate object to be manipulated and photographed frame by frame to appear as though it has come to life when the frames are run consecutively on film. Harryhausen’s process typically called for him to develop miniatures that he would then shape for each frame, meticulously managing the illusion of movement. “Jason and the Argonauts was one of the first cinematic experiences I ever remember as a child,” Burton said. “When you have a certain time in a certain moment, it’s just like a perfect storm. It stays with you.”

Burton is not alone in attributing Harryhausen as an emotional and motivating influence. Trey Thomas, a stop-motion animator on Nightmare who continued his stop-motion work on James and the Giant Peach (1996), Corpse Bride (2005), and Coraline (2009), and eventually became the animation director on Burton’s Frankenweenie (2012), agreed completely. “I was a Ray Harryhausen fan from back in the day. I was a little kid, and it just made a huge impact on me.”

“You know, it’s just beautiful,” said Burton of Harryhausen’s work. “And it’s interesting because I showed it to my kids; I was curious to see how they feel about Ray Harryhausen, with today’s effects, but they still like it. It just looked good.”

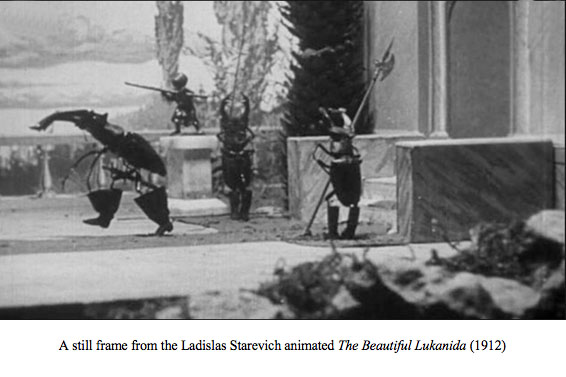

Appreciation for that timeless quality certainly contributed to the end result of Nightmare, as did the clay-animation techniques of the California-based Art Clokey, known for creating cherished children’s television shows featuring the simple-but-effective Gumby (who debuted in 1955 and ultimately turned into a global phenomenon) and later, in 1961, with the Davey and Goliath series. For broader influences worldwide, Nightmare filmmakers also cited exposure to the National Film Board of Canada shorts of the 1950s that used the pixilation technique, in which live actors served as stop-motion props. Burton himself even ascribes to the influence of the Czech stop-motion animation director Karel Zeman, who created a 1945 short that combined animated puppets and live-action footage, as well as the Russian/Polish/French stop-motion animator Ladislas Starevich, who created the first puppet-animated film, The Beautiful Lukanida, in 1912. “That’s why I did Vincent that way,” Burton said of his 1982 black-and-white short that used stop-motion 3-D models combined with hand-drawn animation. “It has a certain funky kind of handmade, crude charm.”

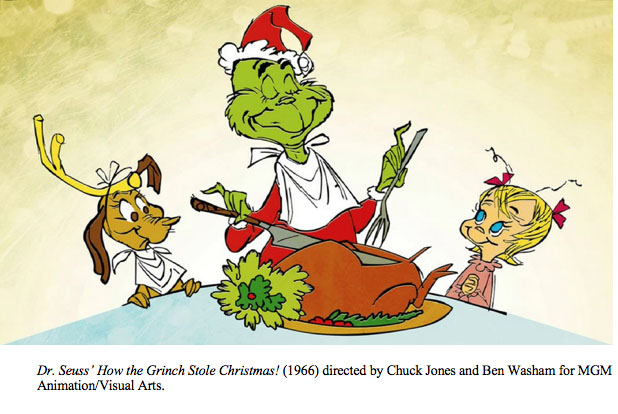

Of course, marrying stop-motion techniques with the spirit of the holidays was also influenced by Arthur Rankin, Jr. and Jules Bass—and their beloved television specials of the 1960s and 1970s. The Rankin/Bass stop-motion films like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964), Santa Claus Is Comin’ to Town (1970), and The Year Without a Santa Claus (1974), first broadcast while Burton was growing up in Burbank, California. Like Nightmare now does, they each had a fascinating and eternal appeal that Burton admired. He even sought inspiration from some traditionally hand-drawn animated holiday specials of the era, like Frosty the Snowman (1969) by Rankin/Bass and Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1966), which served a perfectly balanced medley of rhymes from Dr. Seuss, co-direction by legendary animators Chuck Jones and Ben Washam, and narration by horror film star Boris Karloff. “Those Christmas specials had a huge impact on me growing up,” Burton said. “I was of that generation where we watched them every year.” And, of course, his genius lies in marrying the nostalgia of those Christmas films with Burton’s other favorite holiday, Halloween.

As a child, Burton describes himself as an introvert. And a fan of horror films; he often went to the local movie theaters by himself or sometimes with neighborhood friends. “I went to see almost any monster movie, but it was the films of Vincent Price that spoke to me specifically for some reason,” Burton said.

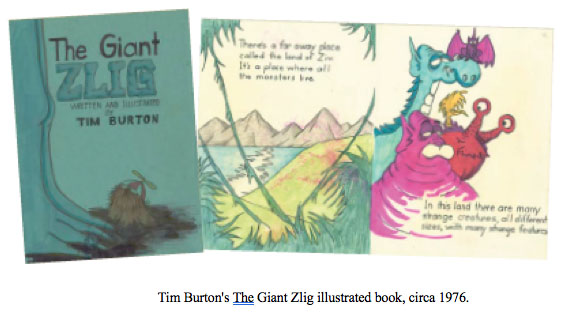

Throughout high school, Burton explored his artistic abilities, winning a contest to design an anti-littering poster that adorned the side of garbage trucks for several months for the city of Burbank. He made extra money during the holiday season painting related decorations on neighbor’s windows. By early 1976, Burton sent a rough layout copy of The Giant Zlig, an illustrated and rhyming text children’s book about an ill-tempered monster, to Walt Disney Productions for publishing consideration. While Disney passed on the publication, the February 19, 1976, letter from a Disney editor—now publicly on display as part of a traveling Tim Burton exhibit—praised the quality of his work.

The support spurred Burton on to keep honing his aptitude for art and pursue a scholarship to the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, California (better known as CalArts), which he received in 1976. At that time, the Disney studio set up a program to teach character animation. It was a way to start training the next generation of animation artists. At Disney, many of the animators that had been there for decades began to retire in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s; there was a need to bring in new, young talent to continue making the revered animated feature films the company had built its reputation on.

At CalArts, Burton met several animation artists, including Rick Heinrichs and Henry Selick. These classmates became friends and later collaborators who helped Burton realize his filmmaking visions. At the end of each school year at CalArts, the animation program has what is known as The Producer’s Show, where the student films are screened. At that time, they were being screened for a Disney review board; now it is for industry professionals from multiple studios. But, notably in the late 1970s, students who showed promise were plucked out of CalArts and given entry-level positions at what is now Walt Disney Animation Studios (then simply known as the Animation Department within Disney). The last film that Burton did at CalArts was called Stalk of the Celery Monster. “It was stupid, but I got picked. It was a lean year, and I was lucky, actually, because they [Disney] really wanted people,” Burton later said.

At Disney, Burton was initially hired as an in-betweener, filling in other people’s animation between key frames. He was assigned to train under now-legendary Disney animator Glen Keane. However, there was little creativity in it, since he was forced to mimic another person’s style. Burton recalled, “I was truly horrible.

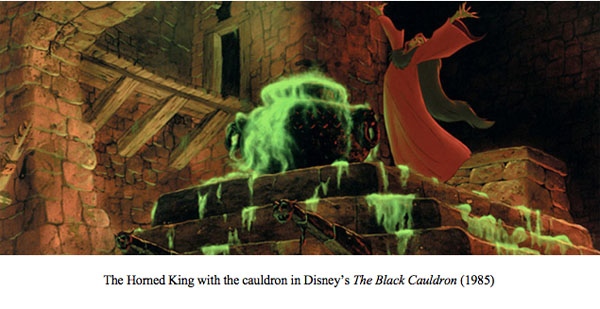

“Because I was terrible,” he continued, “people like Glen were very supportive and tried to help me through it all. But, I wasn’t good at it. Which was lucky, because then they liked my other drawings, so then they said, ‘Oh, why don’t you come do some concept work for The Black Cauldron (1985)?’” Burton happily moved into designing, even though there was no real department for that at the animation studio. “During that period of The Black Cauldron, it was a lot of ideas and concepts. It was a really great creative time to think up ideas and mutate those into other things,” Burton said.

“It was a real transitionary time. If you look at the live-action films that they were doing at the time, it was Tron (1982) or Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983), and Herbie Goes Bananas (1980). So, it was a weird time,” Burton said.

It was exactly during that “weird time” in 1982 that Disney studio development executives Tom Wilhite and Julie Hickson took notice of the work that Burton was doing and supported him. “I was working on a thing called Trick or Treat. And, I had written this little story, Vincent, thinking it was a storybook or children’s book. But then, because we were going to do stop-motion animation on this potential project Trick or Treat, they put a little money towards Vincent for what we could call research,” said Burton. The funding allowed Burton, with Heinrichs, to create a suspenseful short based on Burton’s poem. It featured a seven-year-old boy named Vincent Malloy, who would rather be Vincent Price. The film, which was narrated by Vincent Price himself, was released in New York City on October 1st, 1982.

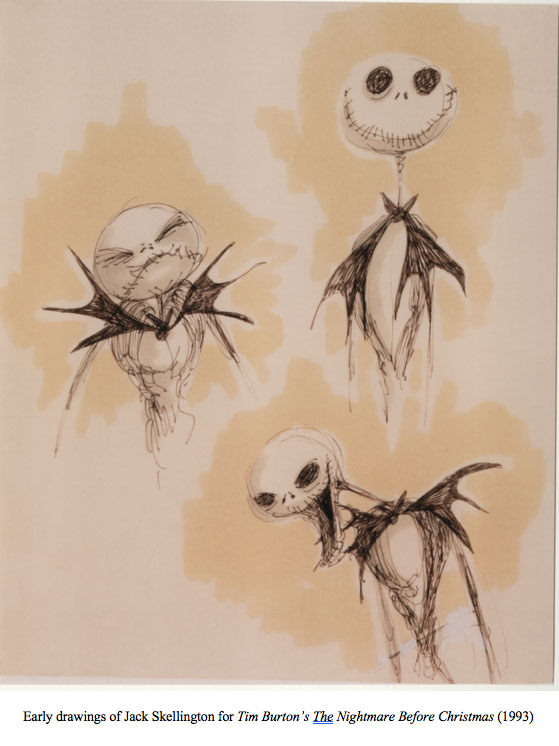

That same year, Burton also wrote the poem The Nightmare Before Christmas, which he saw as a children’s book. Burton shopped the Nightmare storybook around to various publishers; and he remembered getting positive feedback, though each one still turned down the project. “Then I looked at it and thought of it as a half-hour animated TV thing,” Burton said. He had some potential offers to create the special in hand-drawn cel animation; in particular, Disney was initially keen to have it done at a Canadian animation studio called Nelvana. “But, I just said no, it’s got to be stop-motion. That’s part of what it is: stop-motion,” recalled Burton. At that point, Nightmare wasn’t getting any traction, and the original storybook art by Burton was relegated to what was then referred to as the “Morgue” at Walt Disney Feature Animation (now known as the Animation Research Library)—the place where all of the division’s art ultimately goes for preservation, whether a project is shelved or completed.

Still at Disney, Burton went on to work on a live-action television special called Hansel and Gretel (1983) based on the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tale. The special featured an all-Asian cast and used some stop-motion animation to tell a stylized version of the story. It was designed and directed by Burton, playing off his fascination with Japanese culture. The special aired only once, on October 29, 1983, on a cable network called The Disney Channel that had just started broadcasting seven months prior. It was paired with Burton’s Vincent; in addition, it was introduced by Vincent Price as part of the Disney Studio Showcase.

From there, Burton directed a thirty-minute, black-and-white featurette called Frankenweenie that was released in Los Angles on December 14, 1984. This takeoff on the Mary Shelley classic Frankenstein from Burton centered on a young boy named Victor and his dog, Sparky. When Sparky is hit by a car and killed, a distraught Victor is inspired by a school lesson on electrical impulses to bring his dog back from the dead. This marked the coming-of-age for Burton as a director, but the studio, at that time, didn’t view it that way. Burton was let go from Disney when the film was completed.

Using Vincent and Frankenweenie as his calling cards, Burton was hired by Warner Bros. to direct Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985), starring actor/writer Paul Reubens. The film’s producers and Reubens were impressed with Burton’s work at Disney and gave him the opportunity to direct his first feature-length film. After the success of Pee-wee’s Big Adventure in 1985, Burton went on to direct the box office hit Beetlejuice (1988), which then prompted Warner Bros. executives to give Batman to Burton. Batman also went on to become a smash hit in the theaters, breaking box office records in 1989. The following year, Burton directed Edward Scissorhands, which further set the director apart stylistically with a unique vision and aesthetic. That film cemented Burton’s meteoric rise as Hollywood’s hottest new director at that time.

But Burton had not forgotten where he came from or his personal affinity towards animation and art. He still had a deep longing to do something with Nightmare. Jack Skellington was a character he had lived with for a long time and had never been able to think about; he had a deep affection for the Pumpkin King of Halloween Town—someone who was lost, bored with his otherwise-successful life, and seeking something new. In 1990, while in preproduction on Batman Returns (1992), Burton’s agent reached out to Disney to see if they still owned the Nightmare project. Of course, the studio still did and was now thrilled at the prospect of working with Burton.

Nightmare was resurrected from the “Morgue” at the Disney animation studio with the intention of letting Burton make the film and to re-establish the studio’s relationship with him. It was also an opportunity to expand the studio’s animation boundaries and explore other styles and techniques. The Walt Disney Company was in the early stages of a major transformation under a completely new management team than when Burton had previously worked at the company. Creating new animated films was front and center in feeding new properties into an insatiable, vertically integrated organization of consumer products, theme parks, music, games, live entertainment, and more. It became a mutually beneficial situation: Nightmare was a highly personal project that Burton wanted to complete in his own way, and with the Disney studio eager to oblige, he was now in the position to do just that.

Text ©2021 David Bossert

Portions of this article have been extracted from the author’s book, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas Visual Companion, (Disney Editions, June

2019,2020, 2021?, 2022??).

“Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas has become a cult-film favorite for fans of Tim Burton, Halloween, Santa, and Disney, and now Dave Bossert gives us the must-have bible about the history and making of this legendary animated classic.” —Don Hahn, Producer/Director

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

“By a route obscure and lonely,

Haunted by ill angels only,

Where an Eidolon, named NIGHT,

On a black throne reigns upright,

I have reached these lands but newly

From an ultimate dim Thule —

From a wild weird clime that lieth, sublime,

Out of SPACE — Out of TIME.” — Poe

Ray Harryhausen’s films of the late ’50s and early ’60s benefitted greatly from their exciting musical scores by Bernard Herrmann — for my money, some of the finest music ever composed for film.

Children’s literature often contains elements of the macabre and grotesque, and Dr. Seuss is no exception. Consider the Grinch, a hate-filled monster whose only pleasure lies in destroying the happiness of others. I’m sure I’m not the only one who has noted the similarities between the verse of Dr. Seuss and that of Edgar Allan Poe — not in subject matter, of course, but in the rhythm, flow and sheer musicality of the language. “Nightmare” makes this very apparent. (Harryhausen, incidentally, worked with Ted Geisel in the army’s animation department during the war.)

In many ways Burton’s background and early career is like one of those children’s stories about the weird little boy who never fit in anywhere, but who remained true to himself and ultimately triumphed — a real-life Edward Scissorhands. It accounts for the understanding he brought to what I regard as his greatest film, ED WOOD, in which Burton showed great respect for, empathy with, and insight into the subject.

Hi Paul, Yes, the Bernard Herrmann music is terrific and was a great influence on Danny Elfman who composed the score for Nightmare. When I interviewed Elfman at his studio, he spoke about Bernard Herrmann’s music and how much he liked it in those early films. Thanks for reading the piece. Best, -Dave