Today, hot water in a home is commonplace across the country and in much of the developed world, so much so that we take it for granted. But in 1920, only 1% of U.S. homes had electricity and indoor plumbing. The idea of hot water on demand from the home faucet was still years away and was not conventional until the 1940s. That is when plumbing and electrical code standardization paved the way for widespread adaption of these conveniences inside the home.(1)

The Kelvinator company, named after Irish-Scottish physicist Lord Kelvin the discoverer of absolute zero, was founded in 1914 and became the dominant maker of home refrigerators.(2) By 1923, Kelvinator held 80% of the American market for electric refrigerators. The company grew and branched out from that foothold into electric ranges, home freezers, room air conditioners, kitchen cabinets, sinks, kitchen waste disposers, home laundry equipment, and water heaters.

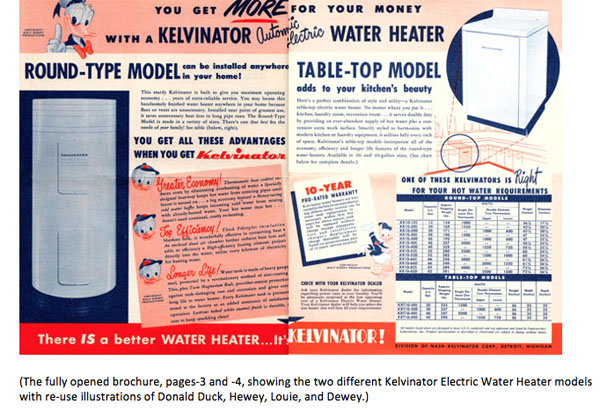

In 1947, Kelvinator advertised an electric water heater for homes using an illustrated brochure. By no means were they the first to sell an electric water heater, but Kelvinator offered two different models under its brand name, the round-type and the table-top models. And who better to help the company sell their water heaters to consumers in that brochure than Donald Duck and his nephews—Huey, Dewey, and Louie.(3) After all, it’s like a duck to water!

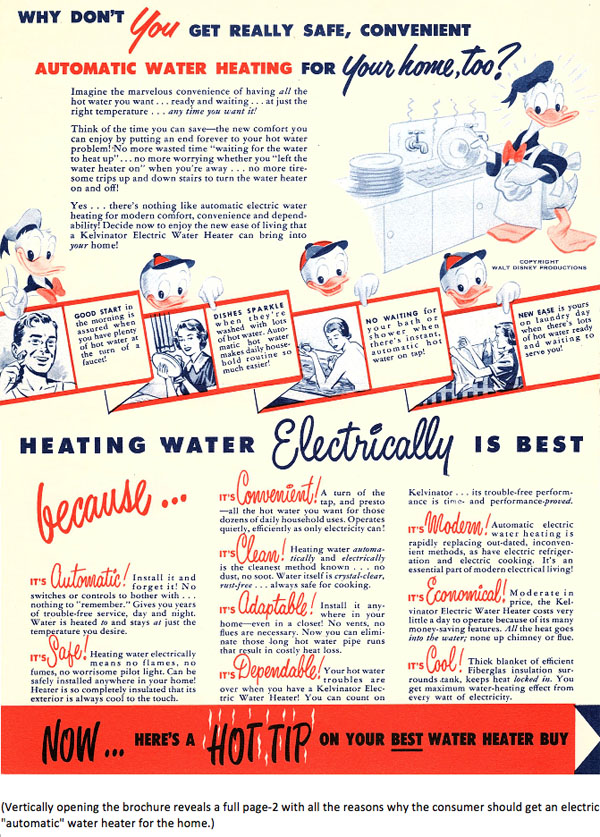

The brochure prominently features Donald Duck pointing to the words HOT WATER on the front cover with his nephews exclaiming, “all you want… when you… want it!” It is an eye-catching cover that would draw the attention of any consumer. The characters are well-drawn in reasonably dynamic poses, yet they could be more appealing, in my opinion. The cover image of Donald’s pointing hand emphasizing the word HOT, created with red squiggly lines, while the nephews are enjoying a shower in this initial illustration. I find the cover very readable from an image and text standpoint, but I think the character drawings on the inside of the brochure have a bit more eye appeal.(4)

Opening the brochure vertically first, I am immediately struck with the fact that the characters are pitching “automatic water heating” and four reasons why you should get it for “your home, too?”(5) The text gives more reasons than you ever need on why “heating water Electrically is best.”(6)

As mentioned, I find the character drawings on page two to be more appealing due to some subtle design choices. If you look at Donald’s eyes on the cover image, the eye further away on the right side of his head appears to be only slightly smaller, which flattens the image. Whereas the drawing of Donald on the left side of page two, with his finger up, has the right eye smaller adding perspective which in turn enhances dimensionality, roundness to Donald’s head. Also, the brow line pinches in closer to the eye, making it, again, more appealing. The same is true for the image of Donald washing dishes with hot water.(7)

These are very subtle choices, but collectively along with how the beak, neck, and other parts of the character are drawn, they make the difference in the overall eye appeal of the drawings. It makes me think that perhaps two different Disney artists worked on this advertisement. The brochure illustrations were likely done through the Walt Disney Studios Publicity Production Department, which had created a tremendous amount of ancillary character artwork before, during, and after the WWII period. These brochure illustrations are precisely the type of work that group did and could have been knocked out in a day or even an afternoon by seasoned artists in that department.

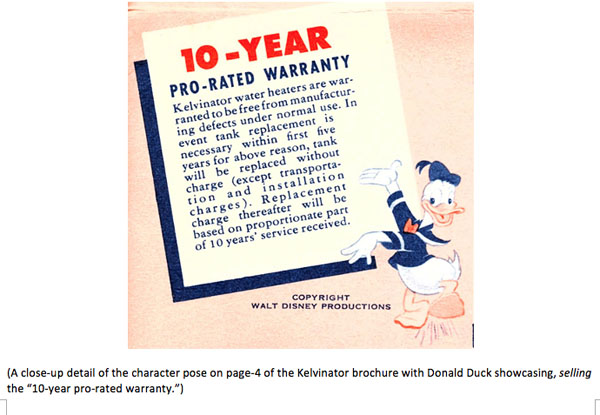

Once the brochure is fully unfolded, it is evident that images on page three of Donald pointing along with the heads of Huey, Dewey, and Louie are re-used from the previous page. The only new illustration is of Donald on page four emphasizing, pitching, if you will, the “10-YEAR PRO-RATED WARRANTY.” This pose of Donald has a solid silhouette, and the text is partially indented to tuck neatly between his splayed arms leading the viewer’s eye to the warranty information.(8)

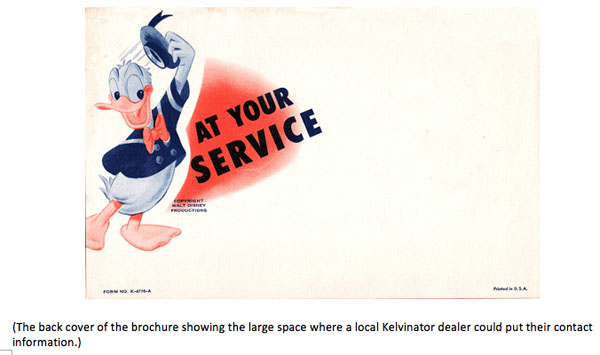

Finally, the back cover is designed for local Kalvinator dealers to print their contact information directly on the brochure. The illustration of Donald raising his cap next to the “At Your Service” text creates a visual link between the popular character, the Kelvinator brand, and the dealer, reinforcing a level of trust and likeability. That is the point of this type of advertising—to sell a product by instilling confidence so that consumers believe they are making a good choice. In this case, by co-branding well-known Disney characters with the Kelvinator brand and a specific dealer in their network to achieve that self-assurance.(9)

What struck me most during my research was how a company like Kelvinator, which at one time held 80% of the American market for electric refrigerators, disappeared from the consumer landscape so completely. At least in the United States. The Kelvinator brand is widely used for various appliances sold in Argentina, and Kelvinator refrigerators are still sold in the Philippines.(10) There are also some commercial refrigeration products bearing the Kelvinator name in the U.S. foodservice industry.(11) But as for a household name brand, it is no more.

If you asked a college-age person if they recognize the Kelvinator brand, the likely answer would be—no. Yet, this was a company that was part of the American household so entirely that they sold all the necessary appliances for the then-modern kitchen. During the mid-twentieth century, Kelvinator was embedded in the domestic consumer lexicon.

Kelvinator was a leader in its industry like Ford, General Electric, and Coke-Cola, who survived and thrived since they were all founded. Even with a solid foothold in the American home and the help of the Disney characters, Kelvinator still vanished into obscurity like other once iconic brand names like Howard Johnsons, Pan American Airways, F.W. Woolworths, among many now vanquished to distant memory. It is a case study in brand destruction versus solid brand management and continuous brand reinvention. The demise of Kelvinator shows how a venerable brand can erode over time, no matter how popular they once were.

©2021 David A. Bossert

Footnotes

1 – How Americans Got Into Hot Water, Sense, October 4, 2019.

2 – Hubbert, Christopher J. (2006). “The Kelvin Home: Cleveland Heights Leads the Way to: ‘a New and Better Way of Living'”. Cleveland Heights Historical Society.

3 – Kelvinator Electric Water Heater Brochure cover featuring Donald Duck, Huey, Dewey, and Louie.

4 – Ibid.

5 – Kelvinator Electric Water Heater Brochure featuring Donald Duck, Huey, Dewey, and Louie. Pg.2.

6 – Ibid.

7 – Ibid.

8 – Ibid, pg. 3 and 4.

9 – Kelvinator Electric Water Heater Brochure back cover featuring Donald Duck.

10 – Morales, Neil Jerome C. (16 March 2012). “Concepcion Industries eyes listing in 2 years”. The Philippine Star.

11 – “Kelvinator Commercial Products”. www.kelvinator.com. 2012.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

There were a few consumer appliance companies that were tied to automotive manufacturers. Nash-Kelvinator was one such example (it was part of the later American Motors until 1968), and there’s also GM-Frigidaire and Philco-Ford. Kelvinator’s issue was that they were tied to a second-tier firm (Nash, and later AMC), and when they were sold to White Consolidated, they were part of a portfolio of overlapping brand names, and they were the odd man out. All three of the automotive firms I mention above got out of the consumer appliance business, eventually. AB Electrolux, interestingly enough, owns both the Frigidaire and the Kelvinator brand names, and the Philco name outside of North America

As it happens, my water heater blew up a couple of months ago, and it was two days before I could get a replacement installed. So I have a new appreciation for what people had to endure in that dark pre-Kelvinator era.

You didn’t give a citation for your statement that “in 1920, only 1% of U.S. homes had electricity and indoor plumbing,” but that figure seems extremely low to me. According to THE U.S. ECONOMY IN THE 1920s (2004) by Professor Gene Smiley of Marquette University, 35% of American homes had electricity in 1920, rising to 68% in 1930. This is borne out by a map published by General Electric in 1921 showing household electrical coverage by state; by then a majority of the population had electricity in all of the states in the Northeast, the upper Midwest, and the West Coast. In Massachusetts, the figure was 97:8 percent. Smiley also points out that only 1% of American farms had electricity in 1920, and only 10% by 1930. After 1930 there were still large areas of the country where electricity was completely unavailable, leading President Roosevelt to establish the Rural Electrification Administration.

As for indoor plumbing, I cite THE ENDURING VISION: A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN PEOPLE (1990; 9th edition 2018) by Paul S. Boyer et al.: “By 1920, 80 percent of American houses, particularly in rural areas, still lacked indoor flush toilets.” Which means that 20% had them, and a somewhat larger percentage would have had running water in their sinks and bathtubs. I recall that in Sinclair Lewis’s novel MAIN STREET (1920), noted for its documentary realism, the residents of little Gopher Prairie, Minnesota, were very proud of all their modern amenities.

The Kelvinator brand is still marketed in Australia through the Electrolux company, and who can forget their old vacuum cleaner ads: “Nothing sucks like Electrolux!”

By the way, it was F. W. Woolworth, not J. W. There was still a Woolworth’s store in downtown Cincinnati, with the familiar yellow lettering on the bright red awning, when I was living there in the eighties. I guess that’s why Mark Twain said he wanted to be in Cincinnati when the end of the world came, because everything there happens ten years late.

Hi Paul,

It isn’t fun not having hot water. When my hot water heater went out, I replaced it with a tankless water heater.

As for the citation, it is indicated as “How Americans Got Into Hot Water, Sense, October 4, 2019.” I often wonder how accurate any of the statistics are for such things back then. I think these numbers are more speculative than anything else.

Regarding J.W. Woolworth, yes that is a typo, it should be F.W. Woolworth the ubiquitous 5 and dime store. Thanks for catching that! Best, -Dave

An example of synergy. In 1938, a year after the merger between Nash and Kelvinator, the Nash car became the first with a fresh-air heating system, which they called “Conditioned Air,” though it wasn’t air conditioning as we know it today. Prior to that, car heaters recirculated the air already inside the car. The following year, they introduced a thermostat, dubbing it the “Weather Eye.” It was the first thermostatically-controlled automotive climate control system.

Thank you for that additional insight.

Best, -Dave

FYI: The illustrations appear to be referencing the studio’s new DUCK HEAD CONSTRUCTION model sheet, coded 17-8064, which was issued shortly after Jack King had left the studio in 1946. This leaflet would make it one of the first of the promotional pieces to use Jack Hannah’s new look for the Duck.

Note that due to production scheduling, this exact head model wouldn’t appear in theatricals until the late 1948 entry THREE FOR BREAKFAST.

Correction: TEA FOR TWO HUNDRED (which was released one day before Christmas 1948), not THREE FOR BREAKFAST. Donald still uses his old models in THREE FOR BREAKFAST, although there are subtle intermediary changes with the timing, posing, and the beak.

(Side note: During this time, the animators are also struggling with how Chip and Dale should look; something which would be nearly finalized in OUT ON A LIMB, the first 1950 Donald Duck entry to actually be finalized and registered entirely in 1950.)

Kelvinator was a sponsor of the early weekly Disney television show and had a display of all its appliances in the theater that showed the 360 degree film CIRCARAMA at Disneyland in Tomorrowland.

One other note of interest: it’s true that Kelvinator at one point had 80% of the market for refrigerators, but this was in the early 1920s, when the industry was just starting and before the likes of General Electric, Westinghouse, and the GM-backed Frigidaire came into the market. It’s a case of Kelvinator being an innovator that was passed out by deeper-pocketed big boys.

I do agree that the 1% figure for electricity and indoor plumbing in 1920 seems low. Granted, during the 1920s there was a great push to electrify rural areas, even before the New Deal-era REA. I worked for a utility that was, in the 1990s, reconstructing lines built in rural Ulster County, NY in the 1920s using mule transportation. The Cato Institute has a paper I’ve seen with a 1% figure for toilets and central heating, but for 1900, not 1920. This same paper has a chart with no data for 1920, but for 1930, 50% of all homes had flush toilets, 5% had refrigerators, and 20% had clothes washers.

We had the table top Kelvinator water when I was a kid.

My parents sure were proud of it.

Look, Unca Donald, we’re naked!