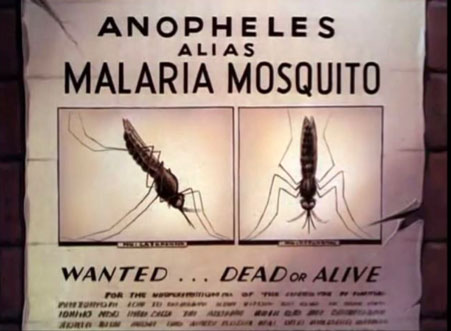

A strong graphic image of the Anopheles Mosquito from THE WINGED SCOURGE, “there is only one cause of malaria—the mosquito. Destroy the mosquito and you will wipe out the disease.” ©Disney

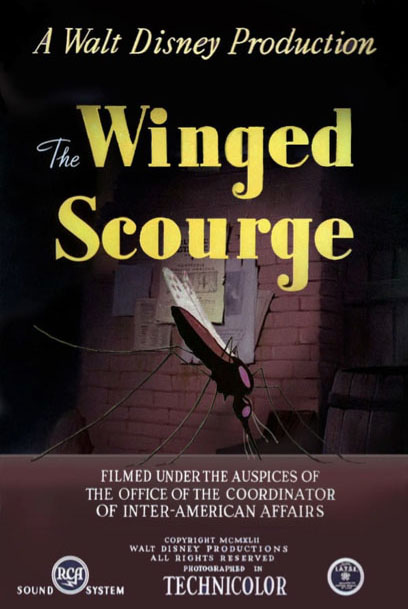

In 1943, the Walt Disney Studios under the auspices of The Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs was commissioned to produce a film originally titled The Mosquito and Malaria – which was later renamed and released as The Winged Scourge. It was designed as a public service educational film related to curbing the Anopheles mosquito and the spread of malaria. This was made as part of the good neighbor efforts by the U.S. government implemented to combat Axis influence in Latin America.

The Winged Scourge, directed by Bill Roberts, was the first health related film produced for The Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs (CIAA), which was created with an executive order signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to strengthen and foster better relationships between all the nations of North and South America—the Western Hemisphere. The U.S. was fearful of German influence in Latin America especially with German and Italian propaganda films being distributed widely and playing to large audiences in the region. The CIAA created a program to supply new and existing films, that fit within their guidelines, to the South American countries.

These films were then dubbed into Spanish and Portuguese with RCA waiving its sound processing royalties. Others followed suit by waiving fees and royalties on any of the films distributed by the U.S. Government. The use of existing films allowed the CIAA to get the program off the ground quickly as it started to commission new films that targeted specific topics like the spread of malaria.

The wanted poster from the opening of THE WINGED SCOURGE, 1942.

The Winged Scourge opens with a wanted poster declaring PUBLIC ENEMY NUMBER 1, Anopheles Alias Malaria Mosquito as the narrator proclaims, “Wanted for willful spreading of disease and theft of working hours. For bringing sickness and misery to untold millions in many parts of the world.” The wanted poster cuts to a stylized map of the world highlighting various regions afflicted with malaria. These images coupled with the serious narration that uses the metaphor of a wanted criminal is highly effective in grabbing the audience’s attention right from the beginning. It is especially convincing since this film was made not that long after the Great Depression when criminals like Bonnie and Clyde, John Dillinger, Pretty Boy Floyd and the formation of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)—G-men—was fresh in the public’s mind. The narrator even refers to the mosquito as, “…this tiny criminal is linked to the destinies of man in a cycle of disease transmission that could not exist without either man or mosquito. Each is solely dependent on the other for the existences of the dread malaria.”

The cycle of the malaria disease being spread by the mosquito in THE WINGED SCOURGE, 1943.

The film then describes the attributes of the Anopheles mosquito with a large profile image of the insect. The narrator disseminates how the Anopheles mosquito is easily distinguishable from other mosquitos because it “stands on its head at a forty-five-degree angle or more.” The newly hatched Anopheles does not contain malaria since it has not touched human blood of an infected individual. As this mosquito takes flight the camera pans along through a swamp landscape then trucks in on a shack as the narrator reinforces the criminal metaphor stating, “… like all thieves and killers she works best under cover of darkness.” Warning that locking and barring doors and windows will not keep this “prowler” out as it can get through the smallest of cracks. Once in the shack the mosquito will find “only a little blood” to steal from a man who is “racked with the chills and fever of malaria.” The animation is reuse of the large mosquito from earlier in the film, and flopped for visual variety, to show how the mosquito will become malaria infected from its victim. Using a profile cross section view, the mosquito penetrates the skin to extract the blood infected with the malaria parasites as the narrator exclaims, “…gorged with disease laden blood, she makes her way to some cool dark place where she will rest for several days and digest the blood.” Although the blood is digested the malaria parasites “multiply to great numbers” and the mosquito becomes a carrier of the disease.

The use of animation was once again the perfect medium to show the specific details of the subject matter which could not be achieved through live action. The Disney artists partnered with the Public Health Service and the Pan American Sanitary Bureau to discuss the subject matter and have a better understanding of how a disease like malaria is transmitted. Walt was a proponent of educating his staff not just with the regular drawing classes at the studio but with lectures on specific topics and also having a reference library in the building as well. It was a way of immersing oneself into the subject matter and that made the films more authentic and, with educational and training films, accurate. In the case of CIAA films, the studio worked with experts and had to get all storyboards approved in Washington D.C. before moving into animation production. This was a similar arrangement with other government agencies that Disney was receiving contracts from for training films, public service announcements, and educational films.

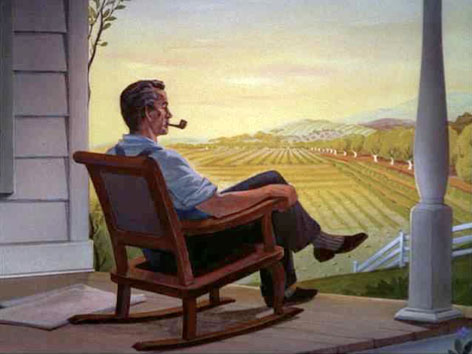

The film continues with the mosquito flying out of the basement of the shack as the narrator says, “… hungry again she flies out as evening falls in search of blood, this time she carries with her the malaria parasites in which she is infected.” As the camera pans across to a prosperous, well maintained farm where a man is sitting on his porch, “… enjoying the peace and plenty of the home he’s worked so hard to build, this man is healthy and happy. Little does he suspect he’s to be the victim of this blood-thirsty vampire.” A flopped version of the mosquito penetrating the skin on the man’s arm to extract blood is used again, but this time infecting the healthy man with the malaria parasites— “…she dines on healthy blood and in payment leaves the chills and fever of malaria.”

The prosperous farmer, the next victim of this blood-thirsty vampire: THE WINGED SCOURGE!

The scene dissolves from a ‘prosperous, well maintained farm’ to a dilapidated overcast property that is no longer flourishing as we hear the low groans of a cello in the musical underscore as the narrator say, “… in all likelihood this man will not die, but neither will he truly be alive for he will be continually in poor health unable to work and keep up his farm.” As the narration continues with the sorrowful musical bed, there is a montage of background paintings depicting the ruined farm as the crops “rot in the fields.” The filmmakers use a combination of camera moves—trucks and pans—to keep the artwork alive and drive the point home that malaria can destroy the productivity of an individual and inflict “untold misery for the victims.” The final image at the end of this sequence is a camera truck out on the rundown farmhouse with a giant mosquito dissolving on as the music climaxes into a crescendo and the narrator says, “… and all because of this tiny criminal which has assumed the proportions of a monster.”

The camera truck continues to pull out on the image of the farmhouse and giant mosquito revealing that it is on a movie screen in a theater. After showing the audience how the Anopheles mosquito can spread the malaria parasites, the narrator asks if there are “six or seven” people in the theater who can volunteer to “combat this evil.” And of course, the seven dwarfs appear. The narrator thanks them, then goes into the facts needed to know to eradicate this mosquito sighting that it must have water to lay her eggs in. The animation shows the larva or “wiggler” stage and then after seven to ten days turns into a pupa or “tumbler.” But once the mosquito emerges from the pupa as an adult, it becomes much more difficult to control. Once this is explained, the film goes into the entertaining instructional portion on how to “fight” this menace. There is a series of cheerful animation scenes beginning with Doc and Sneezy cutting weeds where the mosquito lays eggs. Happy is spraying oil on the water to kill the larva. Bashful is dusting with Paris Green, which is a highly toxic insecticide that has a greenish color and was commonly used at the turn of Twentieth Century and through WWII. It had been used to kill rats in Parisian sewers, hence the name Paris Green. We also see Dopey spraying it inside the house, in the chimney, under furniture, and in the closet. Watching this instructional film showing techniques that are no longer acceptable or safe to use makes the film all the more entertaining. All this while an instrumental version of composer Frank Churchill’s ‘Whistle (While Your Work)’ is used as the underscore.

Dopey spraying Paris Green insecticide around the inside of the cottage.

The entire first half of the film effectively uses camera moves on still paintings with a minimal amount drawn animation. The background paintings are high quality, full of detail and effective in creating atmosphere and mood, coupled with the camera moves, giving each scene enough visual interest to move the story along. The backgrounds and animation in this film are comparable to the studio feature work of the day. But that changed quickly as subsequent Disney produced films for the CIAA were much simpler with flatter, more graphic backgrounds and the use of limited animation to keep costs contained.

Unlike the first half of the film, the Dwarfs are done in full animation which is credited to Milt Kahl and Frank Thomas. Due to the specific action required to get the story points across, no reuse animation from the Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs feature film was possible. All the Dwarf animation was created from scratch and was as good or even better than what was created on the Snow White feature years earlier.

That animation proved to be too costly making The Winged Scourge the last CIAA film to use any established Disney characters. Walt also didn’t want the Dwarfs to distract from the educational points being made in the film saying, “the film is basically to tell people how to get rid of mosquitos. The only reason to bring in the Dwarfs is to add a little interest.” He explained that, “when you begin to get into the gags and impossible things, you’re not accomplishing the job we’re supposed to do—show in a simple way how to get rid of mosquitos.”

The Dwarf sequence ends with them in their mosquito-netting covered beds fast asleep as the narrator says, “…and so, we leave them to enjoy their well-earned rest; free from the annoyance of mosquitos; safe from the dread malaria,” as the camera pulls out on the Dwarf’s cottage in the woods. The scene dissolve to the rundown farm as the narrator continues, “…contrast their peace and happiness with the misery and sorrow of this unfortunate plague-ridden family, these people have lost everything simply because they failed to take a few easy precautions.” Once again, a giant mosquito fades-on large, looming over the dilapidated farmhouse as we hear in a stern tone, “…remember, there is only one cause of malaria—the mosquito. Destroy the mosquito and you will wipe out the disease.” The narrator’s voice then brightens as the rundown farmhouse cross-dissolves to a well-maintained version with blue skies and lush foliage as he exclaims, “…then in place of sickness and poverty, there will be health, safety and happiness.” Then the film concludes with a THE END card noting A WALT DISNEY PRODUCTION in a smaller font at the bottom of the field.

The narration contributes to the impact of the message in this film. Art Baker supplies a wide tonal range that adds to the dramatic effect, heightening the tension where needed to make the subject matter resonate with the audience. Baker was a prolific actor in film, television and radio from the 1920s through the early 1960s. His career began in radio on Tapestries of Life, a show from Forest Lawn Memorial Park and he went on to work on more than twenty-two radio shows per week. Baker also appeared in more than forty films and hosted numerous television programs. When you hear his narration, you know you have heard his unique voice on many other things from that time period. Baker also was one of the narrators in Victory Through Airpower for Disney.

The Winged Scourge proved to be so popular that prints were requested by the U.S. Armed Forces, Australia, and other allies affected by malaria. The film was also later dubbed into the Hindi, Tamil, Bengali, and Telugu languages for India.

Although some of the techniques are no longer valid in eradicating the mosquito, The Winged Scourge is a great example of an effective educational film. The public service, educational and training films created by Disney during WWII helped lay the foundation for what would eventually become Disney Educational Productions. In the decades after the war ended, Disney continued to produce educational films on their own and with commercial partners such as GM, Firestone, Kimberly-Clarke and others. But it all started out of necessity when the studio lost its European revenues at the outbreak of WWII and Walt had the foresight to see new business opportunities for animation.

This newly created movie poster for THE WINGED SCOURGE cleverly uses the title card art with the addition of the Anopheles mosquito.

You may watch The Winged Scourge here:

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

Thank you for posting this history.

I love the animation of the dwarves here. Dare I say, more than in their feature. Maybe the flatter basic opaquing is why the animation reads better for me. It does look like, to me anyway, that there are some subtle cartoony liberties they take with their designs. Perhaps a stronger Fred Moore influence.

I can imagine the thrill of the audience when thinking they are in for a lecture, the dwarves appear. The timing could not be better.

Contrast this with the Snafu toons on the same topic: Lots of gags with anthropomorphic skeeters, and even Snafu’s sickness is a sight gag.

Yes! We’ve got to kill EVERYONE in the house!

I teach undergraduate and graduate courses on the topic of insect pest management and insect ecology. I use this film to highlight how mosquitoes were control before the use of DDT. It is an excellent example of more sustainable, ecologically based pest management.

Do you have any record of who the entomologists were that provided technical support? Also, do you know if Fred Soper used this in his efforts to combat mosquitoes in Brazil? He was an American epidemiologist hired by the Brazilian government to eradicate Anopholese in port cities of Brazil. He later created the Global Malaria Eradication Program.

Thanks for the details of this fascinating film!