In April 1965, while the New York World’s Fair opened for its second year, NASA rocket scientist Wernher von Braun extended an invitation to Walt Disney and some of his Imagineers, including Claude Coats, to visit the space program. Braun famously had designed the V-2 rockets for Nazi Germany during World War II (WWII). As the war ended, “Braun and other German rocket experts surrendered to Allied forces and eventually emigrated from Germany to work for the U.S. Army.” Braun was part of a secret program known as Operation Paperclip designed to give the U.S. an advantage in the Space Race against the Soviet Union and 1,600 other German scientists, engineers, and technicians who were former members of the Nazi Party.

In September 1945, Braun was moved with his wife, children, and parents to Fort Bliss, a large Army installation north of El Paso, Texas, where he worked on advancing ballistic missiles. He and his team assisted in various rocket experiments, including the reassembly of V-2 rockets that had been confiscated and shipped from Germany. At the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico, they launch these refurbished V-2 rockets as part of the Hermes project, which was started as a response to Germany’s rocket attacks on Europe during WWII.

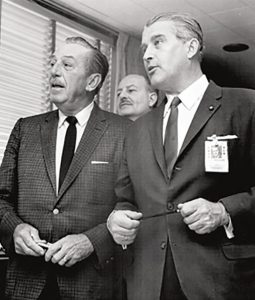

Walt Disney and Wernher von Braun with John Hench behind them at the Huntsville, Alabama NASA Facility also known as “Rocket City.” Courtesy of NASA.

Disney corresponded with Braun at Redstone Arsenal in 1954 to discuss his consulting on a television show about space and attractions at Disneyland. That resulted in Braun working with Disney as a technical consultant on three “science factual” television shows: Man in Space (1955), Man and the Moon (1955), and Mars and Beyond (1957). All three shows stoked the imagination of the American public’s postwar devotion to science fiction, which was a “form of cultural anticipation regarding the coming space age.”

In 1958, Braun led the team that successfully launched Explorer-1, America’s first orbiting satellite atop a modified Jupiter C rocket. By 1960, Braun became the director of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) new George C. Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Alabama, also known as “Rocket City,” where he and his team of scientists and engineers would develop the Saturn rockets that eventually launched men to the moon in 1969. He was a household name connected to the U.S. Space program and, by 1965, reached out to Disney in hopes “that the reunion might rekindle Disney’s enthusiasm for space exploration.” Frank Williams, director of Marshall’s Future Projects Office and a close associate of Braun, stated, “Out of this we would at least establish goodwill, and maybe (if we play our cards right) we could get something going that would be of tremendous benefit to MSFC, Apollo, NASA, and the entire space effort.” Braun wanted to enlist Disney to further man’s travel into space, which meant convincing scientists, industry, politicians, and in particular, the general public of its importance. Dr. Ernst Stuhlinger, a Braun colleague, said, “He fought on all fronts, each in its own language. That was his genius.”

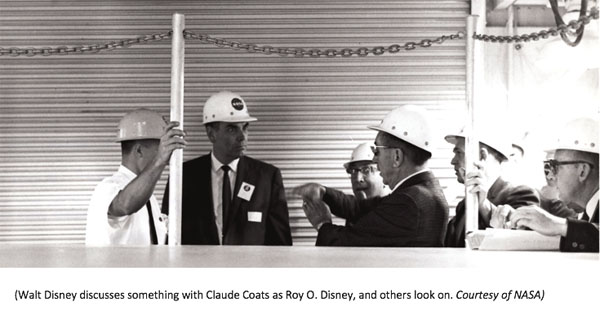

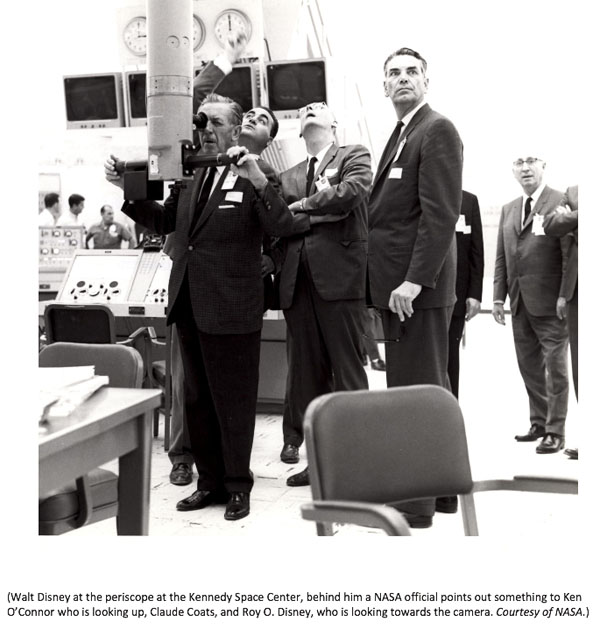

“Wernher von Braun was always grateful to Walt for doing the space pictures that I had done some backgrounds on,” Coats said, “and he wanted Walt to do another series of those space pictures to keep the space program alive.” On Saturday, April 10, 1965, Walt Disney, his brother Roy O., and WED Imagineers John Hench and Claude Coats, along with Ken O’Connor, and Bill Bosche, who worked on the Space television shows, and producer Ken Peterson, “took the company plane and we went to Huntsville for Wernher von Braun…”

“Wernher von Braun was always grateful to Walt for doing the space pictures that I had done some backgrounds on,” Coats said, “and he wanted Walt to do another series of those space pictures to keep the space program alive.” On Saturday, April 10, 1965, Walt Disney, his brother Roy O., and WED Imagineers John Hench and Claude Coats, along with Ken O’Connor, and Bill Bosche, who worked on the Space television shows, and producer Ken Peterson, “took the company plane and we went to Huntsville for Wernher von Braun…”

The trip, which originated in Burbank, first stopped in New Orleans where “Mrs. Walt Disney, Mrs. Roy O. Disney,” Walt’s daughter Sharon and her husband Bob Brown, and set designers Emile Kuri and Tania McKnight were dropped off for their own excursion. The entire entourage spent the night split between the Royal Orleans Hotel and the Roosevelt Hotel.

The following morning, Sunday, April 11, Walt, Roy O., Hench, Coats, O’Connor, Bosche, and Peterson flew to Houston to tour the NASA Manned Spacecraft Center, now known as the Johnson Space Center.

The next day at the Johnson Space Center, the team was able to view several space capsules and to try their hand flying one in a simulator. Walt was able to “fly” the Gemini simulator completing a successful space docking, and then navigated the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM) onto the “surface of the moon” in a simulation. At 6 feet 6 inches, Coats was too tall to do this himself and was relegated to watching Walt have some fun. According to NASA, the maximum height of an astronaut is 6 feet 2 inches. Coats was used to his height being an issue. Once on the studio lot, Walt Disney was showing off a Disneyland Stage Coach, and when Coats approached, Walt said, “No, Claude, you’re too tall. You’ll spoil the scale!”

From the NASA Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Walt, Roy, and the group traveled on Monday, April 12, to the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, to begin their facility tour and get an overview of the current NASA Space program. Coats was already working on several new attractions for Disneyland, including the development of Pirates of the Caribbean, which would not open for another two years, and the Monsanto-sponsored Adventure Thru Inner Space for Tomorrowland. Many of these attractions were planned for the next major expansion at Disneyland, which included an update of Tomorrowland.

On Tuesday, April 13, the Disney team traveled from Huntsville to the John F. Kennedy Space Center in Merritt Island and the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida, to tour the launch pads and associated facilities. The Mercury, Gemini, and early Apollo flights launched from the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. The new Launch Operations Center was built in 1967 adjacent to Cape Canaveral on Merritt Island to accommodate the more massive Saturn V rocket.

Both the Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station facilities work closely together, share resources, and manage and operate facilities on each other’s property. The group was transported around the Kennedy Space Center facilities in what can only be described as a nondescript school bus. They visited some of the operation and assembly buildings along with launch pads. They were all required to wear hard hats while touring several of the assembly and launch facilities. It is not hard to pick out Coats in the photos since he towers over everyone in the group. Coats is frequently seen close to Walt, who is often speaking directly to him, no doubt about some thoughts, an idea, or asking a question.

“If I can help through my TV shows… to wake people up to the fact that we’ve got to keep exploring, I’ll do it,” Disney said in an interview with the Huntsville Times on April 13, 1965. Before Disney and his team visited, Braun wrote to Bart Slattery, director of the public affairs office at the Marshall Space Flight Center, “the Disney tour may easily result in a Disney picture about manned space flight.”

The tour that Disney took with his brother and the group ultimately did not spark any new television or film projects. Whether that was because he had so many projects underway, including another expansion of Disneyland, the formation of CalArts, the planning of Epcot, and other ideas or because he had already covered that ground with the shows he did in the mid-1950s, can only be left to speculation.

Although the trip was not fruitful in the way Braun had hoped, it did inspire the Imagineers who were already working on revamping an outdated Tomorrowland. Such trips have a tremendous impact on artists and designers when researching projects, especially those working at Disney. In this case, the experience—visiting “Rocket City,” Mission Control in Houston, and the NASA launch facilities in Florida—influenced the WED team’s development vision for the Tomorrowland 1967 expansion. John Hench noted years later that Walt liked to travel, “Especially on those excursions to NASA and to these different industrial complexes he loved to visit so much… he wanted to expose us to what was going on. He wanted everybody to be as enthusiastic as he was; it did inspire.”

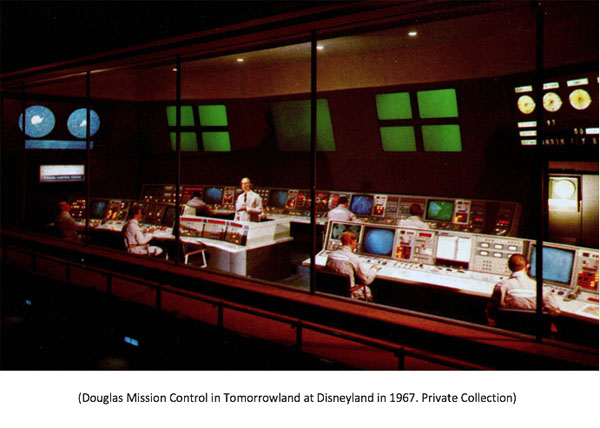

There is no doubt that the trip to NASA had some influence on the Douglas Flight to the Moon attraction. The updated Lunar Transport Theaters and the Mission Control pre-show, the so-called “nerve center of Disneyland’s Spaceport” created under the direction of Claude Coats, were realistic depictions based on what the WED team witnessed on their trip to the NASA facilities. The pre-show was a “breakthrough for its time and offered an accurate view of America’s emerging space technology.” That, coupled with the most advanced human-like Audio-Animatronic figures, “fit well with NASA’s latest scientific information.”

After returning to Burbank from the NASA trip on Sunday, April 18, aboard the Gulfstream, Coats had a more urgent assignment to redesign and install the Primeval World Diorama, which repurposed the dinosaurs from the Ford Magic Skyway attraction from the World’s Fair. It was just one more example of Coats, and many of his Imagineering colleagues, working on multiple projects at any given time.

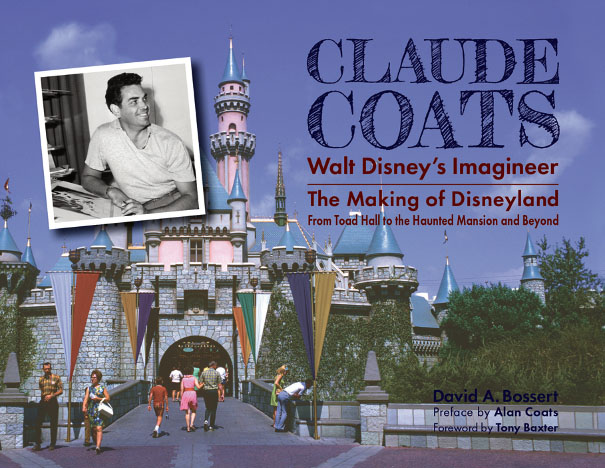

There are many more exciting and surprising stories about Claude Coats and his relationship with Walt Disney during the making of Disneyland in my latest book, Claude Coats: Walt Disney’s Imagineer — The Making of Disneyland. For more information or to order a signed copy of the book, visit www.theoldmillpress.com.

Portions of this article above have been extracted from the author’s book, Claude Coats: Walt Disney’s Imagineer — The Making of Disneyland: From Toad Hall to the Haunted Mansion and Beyond. All footnote attributions are noted in the book.

©2021 David A. Bossert

What they are saying about Dave’s Claude Coats book:

“From magic to engineering Claude Coats was Walt’s renaissance man. Enjoy an insightful look at the life and career of a remarkable Disney artist.”

–Floyd Norman, Animator, Writer, and Disney Legend.

“At a young age I became familiar with the work of the various stylists and background artists credited in the Disney animated features. My favorite was Claude Coats. At WED, I briefly worked with him and was awestruck by his down-to-earth and humble personality. This book is filled with unheard tales and never-before-seen photos tracing Coats’ earliest days at Disney on through to the golden era of Disneyland.”

–Tom K. Morris, Imagineer

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

David A. Bossert is an award-winning artist, filmmaker, and author. He received his B.A. from CalArts School of Film and Video with a major in Character Animation. As a 32-year veteran of The Walt Disney Company, he contributed his talents to The Black Cauldron (1985), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), The Lion King (1995), Fantasia/2000 (1999), and the Academy Award-nominated shorts Runaway Brain (1995), Dali/Disney Destino (2003), and Lorenzo (2004), among many others. Bossert is now an independent producer, creative director, and writer.

“Some have harsh words for this man of renown,

But some think our attitude

Should be one of gratitude,

Like the widows and cripples in old London Town,

Who owe their large pensions to Wernher von Braun.” — Tom Lehrer

Lehrer wrote that song early in 1965 for the satirical NBC comedy show “That Was the Week That Was”, and it would have aired around the time that Disney and his Imagineers were touring NASA at Braun’s behest (the show was cancelled that May). Those lines indicate that, despite his honours and awards, good press, and cozy relationship with Walt Disney, the “man whose allegiance is ruled by expedience” was still controversial in some quarters.

“In September 1945, Braun was moved with his wife, children and parents to Fort Bliss….” Not quite. Braun briefly returned to Germany in 1947 to marry his first cousin Maria (she was 18, he was 35), and it was only afterwards that she and Braun’s parents accompanied him back to the U.S. Their first child was born in the Army hospital at Fort Bliss, but their other two children were born in Huntsville.

I’m only a little shorter than Claude Coats and deeply sympathise with his disappointment at being denied a chance to try out the Gemini simulator. I once waited in line for over an hour at a science museum to try out the triple-axis trainer that the astronauts use, only to be told that I was too tall! They should have had a sign with a picture of a clown sticking his arm out, like at the amusement parks: “You must be NO MORE THAN THIS TALL to go on this ride!”