Today’s video interviews by Dan McLaughlin from the 1986 Golden Awards Banquet feature Harold Ambro and Lee Everett Blair, two more Disney veterans who ended up taking rather different career paths. Ambro became a master animator, while Blair ended up becoming a producer and running one of the most important New York studios of the post-World War II era.

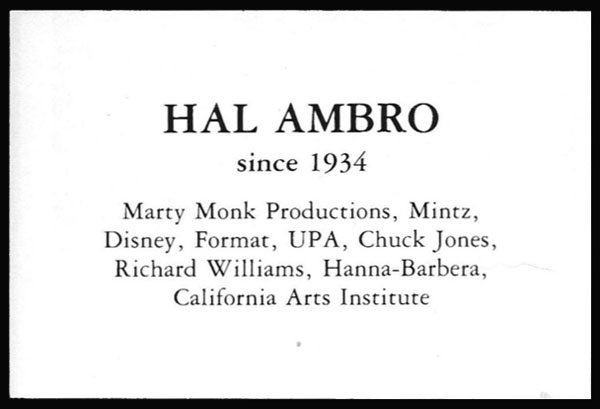

Ambro was born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri, and came to Los Angeles to study art in 1932, braking into animation in 1934 as an animator at Marty Monk Productions (aka Romer Grey Studios, the company run by famed author Zane Grey’s son). Interestingly, he notes that he and other animation newbies there, including Ken Harris, paid the studio “five bucks a week to go there. And they’d put this picture together and go down to Mexico and sell it. We didn’t know that at that time, obviously. Once we found that out, why we decided they ought to pay us about a dollar a foot!” Eventually, he, Bob Bemiller and several others found work at Charles Mintz Studios.

After the war, he was hired by Disney, first as an assistant and then as an animator. Andreas Deja noted that, “Even though he never reached the status of supervising animator there, his animation can often be found in sequences that were [led] by such animators like Ollie Johnston (the opening section of Johnny Appleseed) and Milt Kahl (Ambro animated almost half of the footage of The Fairy Godmother in Cinderella).” He left in 1966 because, as he told John Canemaker, “there is only so much room at the top of the ladder at Disney.”

He then went on to animate, among others, for Chuck Jones and Richard Williams. “I liked the stuff that Chuck was doing,” he said, “because it was a cross between Disney animation and Saturday morning shows. He tried to do as good as job as you could, make it look like full animation. And like a lot of the other commercial operators, he was interested in how few cels he could get by with, which is par for the course.” For Jones he worked on such TV specials as A Very Merry Cricket, Rikki-Tikki-Tavi and The White Seal. For Williams, he animated on A Christmas Carol and Raggedy Ann & Andy. Ambro then ended up, like many others at Hanna-Barbera — animating on such features as Heidi’s Song and Rock Odyssey — before eventually, teaching animation at CalArts.

Blair’s career in animation has largely been overshadowed by that of his wife, Mary, and his brother, Preston, though his own accomplishments were nothing to be ashamed of. He studied art at Chouinard, where he met his wife and won a gold medal in the art division of the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. Blair was hired by Iwerks in 1934, where he was an inbetweener. He apparently was so good at it that “they didn’t want to let me be an assistant, so I quit and went over to Harman-Ising, and worked on Bosko.”

However, when hired by Disney after MGM set up their own cartoon unit, he recalled “they weren’t interested in my animation, which I had worked years to become; they were only interested in the color I had been directing at Harman-Ising on their shorts. So, I went to Disney’s as a color director on Pinocchio and did little sketches on for the key sequences.” On Fantasia, he did storyboards for “The Dance of the Hours” and “The Pastoral Symphony” sequences. During the Disney strike (which Preston joined), he and Mary became part of Walt Disney’s good will trip to South America, which led to him help create Jose Carioca for Saludos Amigos.

During the war, he was drafted into the Navy, helping “direct the Animation Department at the Photo Sciences Lab with Paul Fennell, at the Naval Air Station at Anacostia.” He subsequently opened New York-based TV-Film Graphics with Bernie Rubin. The studio started out doing industrial films, such as The ABC of the Automotive Engine for General Motors, but ended up focusing on TV commercials. Despite the company’s apparent success—“we had four directors and a whole bunch of assistants, [and] cutting rooms that wouldn’t quit”—it started losing money and had to be shut down. Blair moved to Soquel, California, where he painted and sold watercolors, which was his “first love.” He also taught painting at Cabrillo College and animation at the University of California Santa Cruz.

There is precious little on the animation careers of both men, though Robin Allan’s interview with Blair appears in volume 3 of Didier Ghez’s Walt’s People. There are several online articles regarding Blair’s work as a watercolorist, including Parker Lau’s piece for the Sullivan Goss gallery (which also covers his animation career somewhat less accurately).

Next week: Morey Zukor and Al Bertino.

Harvey Deneroff is an independent film and animation historian based in Los Angeles specializing in labor history. The founder and past president of the Society for Animation Studies, he was also the first editor of Animation Magazine and AWN.com. Harvey also blogs at deneroff.com/blog.

Harvey Deneroff is an independent film and animation historian based in Los Angeles specializing in labor history. The founder and past president of the Society for Animation Studies, he was also the first editor of Animation Magazine and AWN.com. Harvey also blogs at deneroff.com/blog.

I wonder which BOSKO cartoons Lee Blair worked on.

“and won a gold medal in the art division of the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics”

Since we’re in an Olympic year this summer, it might be interesting to learn more about these art-related medals they once awarded at the Games. I’ve noticed them mentioned in a few of Harvey’s posts now.

I’m impressed such a division existed in the Oympics at all.

It seems like Hal Ambro was a little mixed-up on Marty Monk. Marty was Boyd LeVero’s creation, not Romer Grey’s. Romer did Binko the Cub. Maybe Hal worked on both characters?

Some Romer Grey Studio animation from the Binko cartoon HOT-TOE MOLLIE is reused in Boyd LaVero’s Marty cartoon MEXICALI LILY—an oddity I’d always presumed came from animator Cal Dalton moving from Grey to LaVero (he is credited on the original titles for LaVero’s JUNGLE HOLIDAY).

Given Ambro’s story, it seems more than one animator worked on both studios and with both characters. Maybe Grey’s studio, in some capacity, actually evolved into LaVero’s? (Though it seems peculiar that if it did, no more effort would have been made to sell or complete the remaining two Grey-era cartoons.)

Wow! Thanks for posting this. It’s good to hear Lee Blair’s voice again!