To say that Willis Acton Pyle, who celebrated his 100th birthday in 2014, has had a long and productive career in animation and art is something of an understatement. The son of a Dust Bowl farmer, he was born outside of Lebanon, Kansas, though his family moved to Colorado when he was 2; Pyle went to Boulder Prep then majored in art at the University of Colorado Boulder. He became art editor of Colorado Dodo, the school’s satirical journal, and was an advertising illustrator for Gano-Downs, a Denver clothing store; while a senior, he answered a Disney ad for artists. His work wasn’t good enough to get a production job, but he was offered a job in the Traffic Department at $16.00 a week, if he was willing to attend art classes at the studio; so at 23 he dropped out of school and starting work at Disney in November 1937. Pyle’s schooling included classes with Rico Le Brun (“one of the great draughtsman of our age”), Donald Graham and Gene Fleury. He eventually became an inbetweener and then an assistant animator in Milt Kahl’s unit, working on Pinocchio, Fantasia and Bambi.

He joined the 1941 Disney walkout because, “All my friends were on strike, and I couldn’t pass them in the picket line,” though he had no personal beef with Disney (he was then making $40.00 a week). He then worked for Lantz on Woody Woodpecker cartoons for about 6 months. During this period, he went to night school to study celestial navigation and was set to take a job with American Airlines when he was drafted, eventually ending up at the animation unit of the Army Air Corps’ fabled First Motion Picture Unit run by Rudy Ising; there, working under Frank Thomas, he began animating and did the model sheets for the character of Trigger Joe. (For those interested, Don Yowp posted a syndicated newspaper column on the production of the series.)

He joined the 1941 Disney walkout because, “All my friends were on strike, and I couldn’t pass them in the picket line,” though he had no personal beef with Disney (he was then making $40.00 a week). He then worked for Lantz on Woody Woodpecker cartoons for about 6 months. During this period, he went to night school to study celestial navigation and was set to take a job with American Airlines when he was drafted, eventually ending up at the animation unit of the Army Air Corps’ fabled First Motion Picture Unit run by Rudy Ising; there, working under Frank Thomas, he began animating and did the model sheets for the character of Trigger Joe. (For those interested, Don Yowp posted a syndicated newspaper column on the production of the series.)

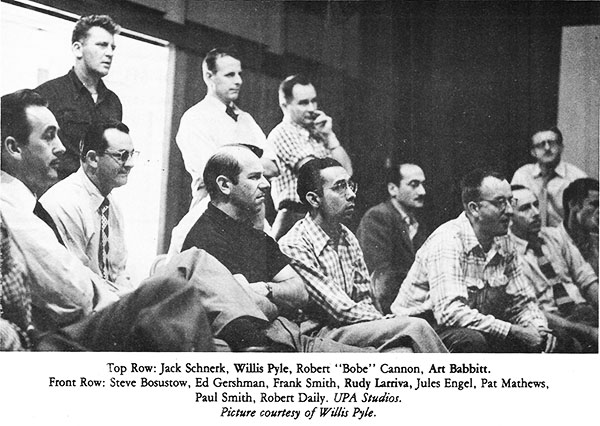

After the war, he wanted to branch out and got a gig as West Coast fashion artist for Vogue, but he would have needed to relocate to New York to do it full-time; so the newlywed Pyle joined fellow vets of the Disney strike and FMPU at UPA doing animation for such films as Ragtime Bear (the first Magoo cartoon, for which he helped develop the character designs) and Gerald McBoing Boing. After 4-5 years, he moved to New York and opened Willis Pyle Productions. Pyle mostly worked on commercials, including animation for several memorable spots for R.O. Blechman’s Ink Tank, including the acclaimed 1966 CBS Christmas Greetings; he also worked on Charlie Brown TV specials for Bill Melendez and Richard Williams’ Raggedy Ann and Andy. His studio was in the Abbey Victoria Hotel near Rockefeller Center, where he did all the animation himself. He told John Canemaker “I was offered [full-time studio] jobs, but I wanted to get up from my desk and go to the Museum of Modern Art at 3 o’clock in the afternoon if I wanted to,” presumably to go to MOMA’s afternoon screenings of classic films, “or go to Macy’s and buy a tie.”

At 68, he gave up animation for painting and exhibited for many years at Manhattan’s Montserrat Contemporary Art Gallery. During video chat, he noted he still took art classes at the Art Students League, the National Academy and the Brooklyn Academy.

Willis Pyle

There are a batch of good articles about Willis Pyle online. You might want to start with John Canemaker’s 2010 Print magazine piece. The University of Colorado Boulder has posted several similar but distinct articles on its Coloradan Magazine and Colorado Arts & Sciences Magazine sites. There is a somewhat oddball piece written for Steinway and Sons, which tells how, at 85, Pyle fulfilled his lifetime ambition to play the piano after buying an 1872 Steinway; however, it also provides a lot of interesting details about his career. Then there’s the 2009 CBS News Sunday Morning profile, which you can see a minute-at-a-time on the Internet Archive. Finally, I should note that Pyle donated his personal archives to Indiana University’s Lilly Library, in Bloomington, which is described here.

This is the last of my 1987 interviews. Next week, we will start posting video chats by the late Dan McLaughlin from the 1986 Golden Awards Banquet.

Next week: Martha Sigall.

Harvey Deneroff is an independent film and animation historian based in Los Angeles specializing in labor history. The founder and past president of the Society for Animation Studies, he was also the first editor of Animation Magazine and AWN.com. Harvey also blogs at deneroff.com/blog.

Harvey Deneroff is an independent film and animation historian based in Los Angeles specializing in labor history. The founder and past president of the Society for Animation Studies, he was also the first editor of Animation Magazine and AWN.com. Harvey also blogs at deneroff.com/blog.

Leave a Reply