These past couple of weeks at Cartoons On Film headquarters have been hectic, to say the least. In bringing back a couple of out-of-print volumes in the Cartoon Roots series and introducing the new Cartoon Roots: Otto Messmer’s Feline Follies collection, it’s been an almost nonstop game of playing catch-up with orders and emails. Whew! As I promised, though, I would be back soon with even more exciting news…and that’s what we shall get into today.

Special thanks to Cartoon Researcher David Gerstein for assembling this fine promo video!

Without further ado, there it is above: a new Kickstarter campaign to raise funds for restoring and rereleasing more of Walter Lantz’s early Bray Studios-era shorts! You can read more about the campaign itself here, and while I hope most readers will support it, I’ll spend a bit of time going over this period of Lantz’s career in this post. We’ve worked on some of these films in the past for three of the Cartoon Roots projects, and they really are a delight. Considering just how prevalent Lantz had been throughout nearly the entire history of theatrical animated shorts, and certainly throughout the ‘Golden Age’ of animation, I’ve always found it rather ironic and depressing that his silent era films, which were incredibly creative and are still so entertaining, have been so obscured and incredibly rare over the decades. It’s not like they’ve mostly been entirely lost—they’d simply fallen through the cracks.

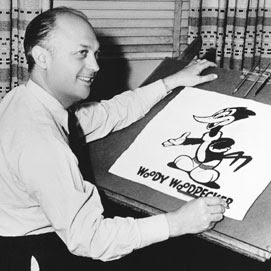

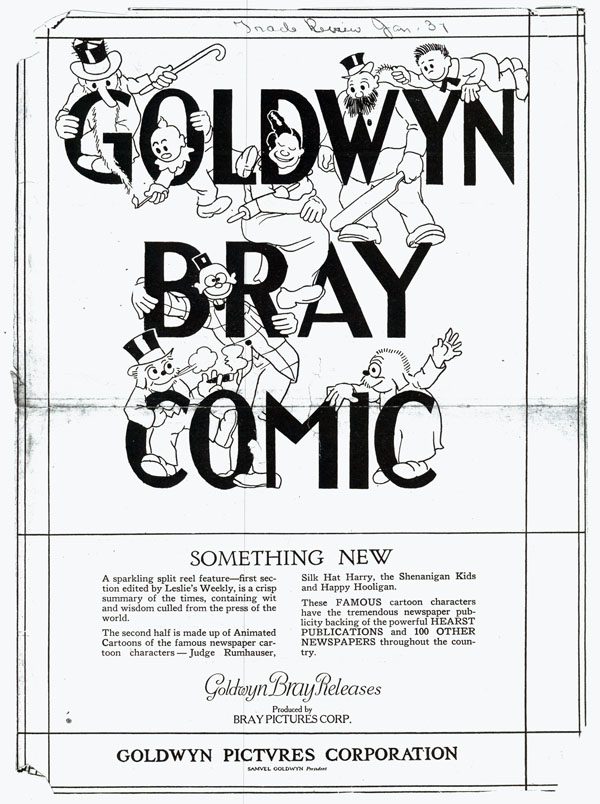

Walter Lantz (1899-1994) is synonymous with Woody Woodpecker, who first appeared on the screen in the early 1940s, among a variety of other characters who were offered to moviegoing (and later TV) audiences throughout the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s…and beyond. As a teenager in the late 1910s, Lantz started getting his feet wet in animation, working on several of the animated adaptations of famous comic strip characters that were owned by the Hearst syndicate—think things like Happy Hooligan, the Katzenjammer Kids, and the like. At that time, the Hearst animation entity was operating in a somewhat autonomous fashion, with distribution through Educational Pictures. However, the Bray Studios would soon take over this production line, in addition to its own pre-existing in-house series that were in regular release. Many of these series would soon be seen under the Goldwyn-Bray Pictograph moniker, and eventually through Bray’s states rights distribution endeavor known as the Bray Magazine by 1921 and 1922.

Walter Lantz (1899-1994) is synonymous with Woody Woodpecker, who first appeared on the screen in the early 1940s, among a variety of other characters who were offered to moviegoing (and later TV) audiences throughout the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s…and beyond. As a teenager in the late 1910s, Lantz started getting his feet wet in animation, working on several of the animated adaptations of famous comic strip characters that were owned by the Hearst syndicate—think things like Happy Hooligan, the Katzenjammer Kids, and the like. At that time, the Hearst animation entity was operating in a somewhat autonomous fashion, with distribution through Educational Pictures. However, the Bray Studios would soon take over this production line, in addition to its own pre-existing in-house series that were in regular release. Many of these series would soon be seen under the Goldwyn-Bray Pictograph moniker, and eventually through Bray’s states rights distribution endeavor known as the Bray Magazine by 1921 and 1922.

By 1922, however, Bray no longer had an affiliation with a major distributor like Goldwyn, as nearly all of his previous star directors like Wallace Carlson and most notably, Max Fleischer, had jumped ship by that point to go out on their own, or to seek more self-affirming ventures. Cartoon production at the studio would go on, but things had become a bit quieter, toned down a notch. Eventually, Bray would sign with Standard Cinema Corporation and Film Booking Offices of America for further distribution, yet there was a lull in this in-between period.

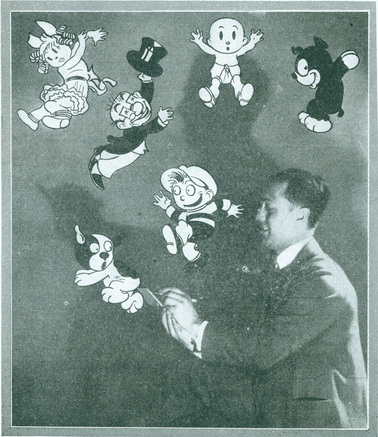

Walter Lantz was still quite a young man at this point, but a promising animator. In the absence of the more recent characters and series that were being produced there, Bray would revive his earliest cartoon star, Col. Heeza Liar, for a second incarnation. These films would be a combination of animation and live action footage, with techniques and aesthetics undoubtedly being borrowed from what was learned in producing and distributing Fleischer’s Out of the Inkwell films, just a couple of years prior. Walter Lantz was tasked with working on these new Col. Heeza Liar films, which were largely directed by Vernon Stallings, and the new incarnation ceased in 1924.

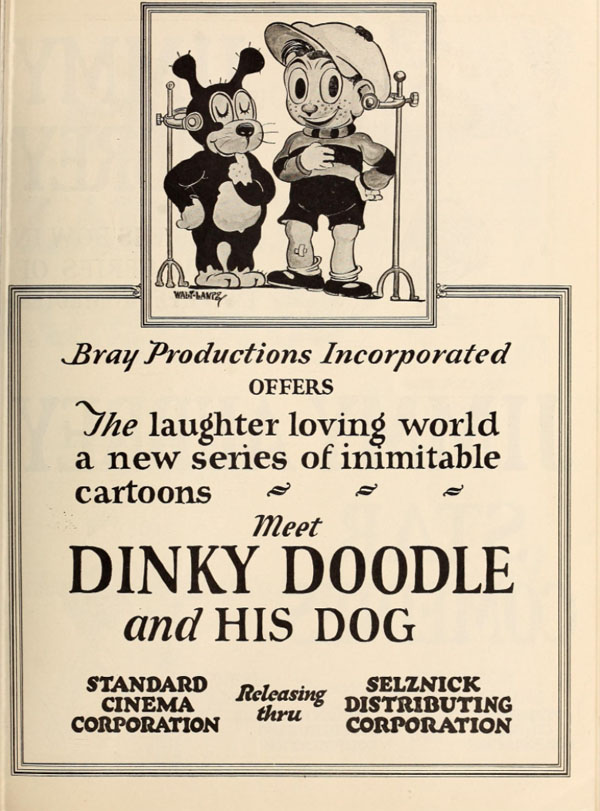

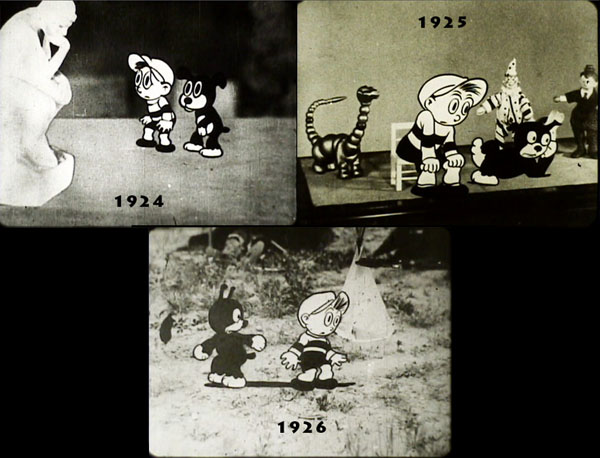

The end of the new Heeza Liar series left a considerable void of new animated cartoon product at Bray, and Lantz remained employed there—naturally, it would seem obvious that Lantz should be given a directorial role and the opportunity to create a new series of his own. And thus, Dinky Doodle, and his sidekick pup Weakheart, were born in The Magic Lamp (1924). It was something of a trope by this point, having a little boy and his dog as the main characters in an animated cartoon series, but Lantz introduced something fresh and new to this particular offering.

Up until this point, it had only been the Out of the Inkwell films, the second incarnation of Heeza Liar, and Disney’s budding new Alice in Cartoonland series that relied heavily on compositing live action footage with animation, and all of these offerings were quite esoteric in their own right. Lantz would give this treatment to a more predictable set of characters, but by doing so in this rather complicated and visually stunning format, the results were quite charming and enjoyable.

Here’s Dinky Doodle in The Pied Piper (1924) in a French print. Courtesy of the Stathes Collection:

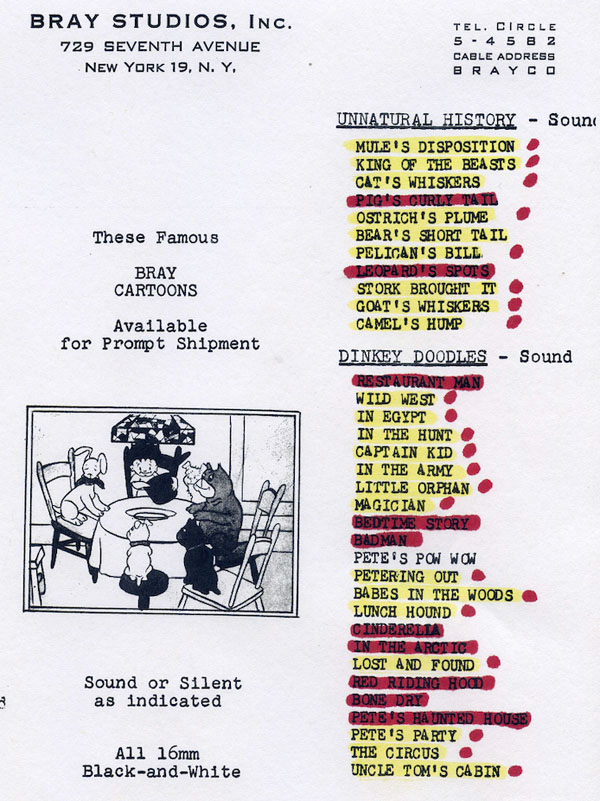

Lantz would soon add to the production schedule with a couple other hybrid animation and live action series. Soon came the Unnatural History cartoons, which were ridiculous explanations of how certain animals in nature came to have their most noteworthy physical traits.

Video: The Leopard’s Spots (1925)

Yet, the Unnatural History cartoons were all one-shots, with no recurring characters beyond Lantz himself appearing in the live action footage. I think these films are enjoyable, but I can only imagine that audiences did not find them incredibly memorable. Dinky Doodle was being produced through 1926, though it seemed to be time for a new concept. Sort of.

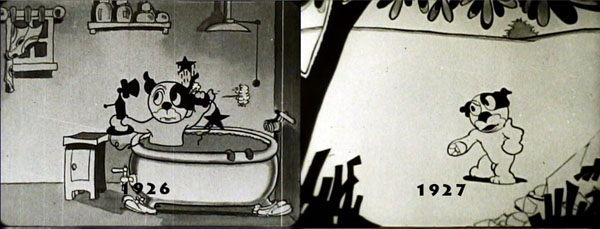

Lantz then introduced the Hot Dog series of cartoons, featuring Pete the Pup. No, not Pooch the Pup. Pete the Pup! Weakheart simply wasn’t enough, and Pete would prove to be a bit more of a dynamic and entertaining character. Yet, as I recall one or more colleagues saying years ago, Pete was basically Dinky in a dog costume. Still, these were a charming series of films.

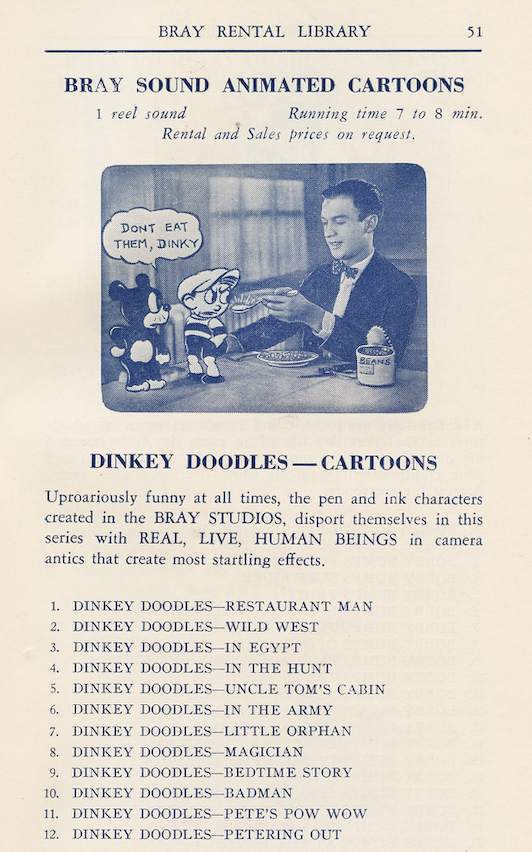

For a variety of reasons, Bray gave up on theatrical animated shorts by the end of 1927, and here Lantz’s career at Bray also ended. Lantz would go on to California and would eventually found his own studio, producing a later incarnation of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit first, before some of the properties that the general public is more aware of—such as Woody, mentioned earlier. The Bray Studios did not cease operations in totality until the 1980s, however—nor did Lantz’s films entirely disappear by the time sound films became the norm. There was a small, yet somewhat robust market for older, silent films in the nontheatrical 16mm film rental market, and Bray capitalized on this to some extent in the 1930s and 1940s. Bray, also, prepared a package of some of his studio’s animated films for television in the 1950s.

Over the years, I’ve keenly searched for many of these obscure old 16mm prints that have been lurking in all sorts of unspeakable places…as well as right under our noses, scattershot among the collections of some longtime film collectors. I’ve also been able to find a number of 35mm prints of the Dinky Doodle cartoons as well. While not all of the prints are complete or in good condition, I’ve come close to reuniting something like two thirds of Lantz’s Bray output, if not more. I would love to produce restorations and rereleases of as much of the material as possible, and this initial Cartoon Roots project is the first step in getting a big batch of them out there once more.

This time around, I’ll need your assistance through the Kickstarter campaign. And if anyone reading has leads on more prints of these films, do get in touch! My team and I are often reconstructing these cartoons from two, three, sometimes even four surviving prints to make the best possible final version. Even if I already have a print of something, another print may be helpful. You can contact me directly here.

While we do still need any and all support in pledge form before the campaign ends, the Kickstarter has done rather well since launching just under two weeks ago. I’m already planning to introduce a stretch goal, soon, and this would likely be for the creation of an entirely separate Cartoon Roots restoration project and home video release…on top of the Dinky Doodle collection. One thing I’ll tell you for now is that there are currently 5 Cartoon Roots collections on the markets. If time and funds were of no issue, I would ideally love to have something like 30 or 40 titles on the market, if not more.

Video: a walk through the archive

That being said, the Cartoons On Film archive here represents a cross-section of practically all aspects of silent animation, and some early sound animation as well—in film gauges ranging from 9.5mm to 16mm, 17.5mm, 38mm, and certainly 35mm. If you name a studio, series, or character from this early period, there’s a good chance there is some material held on that particular item. Maybe even a lot of material. I’m always trying to add more material, and the archive is ever-growing. I already have ideas of what should be covered in a separate project to be funded in a stretch goal, but what do you think? What are some early characters, series, or studios, *you* would like to see represented in the Cartoon Roots series? Let us know in the comments…and thanks for your support!

Tommy Stathes is an animation historian specializing in silent era cartoons. He resides in New York and frequently holds public screenings throughout the city. You can read more about his work, his collection and his research on his website:

Tommy Stathes is an animation historian specializing in silent era cartoons. He resides in New York and frequently holds public screenings throughout the city. You can read more about his work, his collection and his research on his website:

I’ve been enjoying the Feline Follies set, which arrived here on the opposite side of the world just nine days after I ordered it. I wish I got such prompt service from everybody! The Dinky Doodle collection sounds intriguing, and I look forward to seeing it when it comes out. Best of luck in this ambitious and worthwhile undertaking.

As for future Cartoon Roots, I’d love a collection of early Aesop’s Fables, if the video quality and music are up to the standard of the previous volumes. Hope you can get your hands on a good print of “Farmer Al Falfa’s Chemistry Lesson” — it’s a masterpiece!

Note to Paul Groh: “Chemistry Lesson” is a retitle of “Raisin and a Cake of Yeast.”

Commonwealth’s sound division liked to relabel what they got. For one thing, the copy of “Closer than a Brother” that’s on YouTube… that may likely be a retitle of “Scrambled Eggs!” The real “Closer than a Brother” seems to be about Henry being overly attached to Farmer Al Falfa than usual; Al Falfa gets upset to the point that he ties up Henry to a balloon provided by a Chaplin-esque figure, then shoots him down for a couple of fish to get eaten; only to survive and come out with more cats!

(The Van Beuren-era sound reissues of older Fables also did the same practice. For instance, “Custard Pies” is actually “Pie Man.” I cannot figure out what “The Jail Breakers” is supposed to be, but “House Cleaning Time” seems to be “House Cleaning.” I don’t know what would exactly be the first Fable to have been produced after Terry left, either.)

Meanwhile, the silent Commonwealth prints in comparison preserved the original labels.

“In a Bag” is labeled as “In a Bag” on Commonwealth’s silent release, whereas it was labeled as “The Picnic” for their sound release. Make sure to grab the silent Commonwealth ones whenever you can! They actually keep the intertitles and the moral.

When I made the short documentary film, “Walter, Woody and the World of Animation” (circa 1980) for Walter Lantz to use as part of the exhibit devoted to him at the Universal Studios Tour, I had the key to Walter’s film vault where he kept prints of all his films and cartoons. If my memory is correct after all these years, he had pristine 16mm prints of his “Dinky Doodles” cartoons. I don’t remember how many he had, but I watched a few of them, and I used a short clip from one of them for my film (which you can still see on Jerry Beck’s first DVD collection of Woody Woodpecker cartoons). You might try to track down where all those vault prints went after Walter’s death. It might save you some restoration effort. I do remember that his prints were excellent quality.

Thanks Paul!

Jackson: Right and right. The only problem is that some local TV stations physically cut the morals out of the prints, even if they were otherwise retained in the printing of the silent versions. I’m also about 45 years too late. In the mid-70s, Blackhawk came into possession of Commonwealth’s inventory, including hundreds and hundreds of ex-distribution prints that had been returned to them when contracts expired with various stations. They were selling these used prints for something like $5 a pop, many multiples of each title in the package (over 300 of the 450+ cartoons). Ironically, I’ve had trouble finding many of these prints, even though they were so numerous at one time. I’m hoping a big cache will come my way at some point.

As far as future silent animation releases on the Cartoon Roots label, I would love to see sets devoted to Jerry on the Job and Mutt and Jeff cartoons. It would also be nice to see a set of Disney Alice Comedies. Various DVD sets have collected some of them in varying quality, but it would be nice to see the Cartoons on Film treatment given to those early gems!

Note to Jackson: as for the Van Beuren-era sound reissues of silent Fables, here’s what my research has turned up, in part looking at copyright synopses and reused morals (which usually, if not always, stayed the same from silent to sound) to match them up:

DINNER TIME

Moral: There is a real need for a tonic for people whose heads are bald on the inside.

= Seems to reuse part of HUNGRY-HOUNDS, MP 3155, 1925, or at least to be inspired by it, but is at least partly original for sound. Moral seems to be new.

STAGE STRUCK

Moral: All the world is a stage, covered with banana peels.

= Originally ?? (Maybe all original for sound?)

PRESTO CHANGO

Moral: Go around with a chip on your shoulder, and somebody will knock your block off.

= Originally THE MAGICIAN, MP 3873, 1927. Waffles in the PRESTO copyright synopsis was called Thomas in the MAGICIAN synopsis, but otherwise the synopses are identical

SKATING HOUNDS

Moral: Many a man who is a boon to his mother is only a baboon to the rest of us

= Originally CRACKED ICE, MP 3812, 1927

FAITHFUL PUP

Moral: A dog is man’s best friend, unless he has fleas.

= Originally A DOG’S DAY, MP 4026, 1927

CUSTARD PIES

Moral: Never put off till tomorrow what you can put off till the day after tomorrow.

= Originally THE PIE MAN, MP 2885, 1925

WOOD CHOPPERS

Moral: A powdered nose is no guarantee of a clean neck.

= Originally LUMBER JACKS, MP 2754, 1924

CONCENTRATE

Moral: Be yourself.

= Originally HOLD THAT THOUGHT, MP 2858, 1925

THE JAIL BREAKERS

Moral: Never give up a sure thing for a possibility

= Originally BIGGER AND BETTER JAILS, MP 2833, 1925

HOUSE CLEANING TIME

Moral: When you get something for nothing, look out for the hook.

= Originally CLEAN UP WEEK, MP 2869, 1925

BUG HOUSE COLLEGE DAYS

Moral: Courtship is a man pursuing a woman, until she catches him.

= Originally BUGVILLE FIELD DAY, MP 3070, 1925

A STONE AGE ROMANCE

Moral: A real he-man can make his wife do anything she wants to.

= Originally WHEN MEN WERE MEN, MP 3043, 1925

And the characters’ names are Charley Caveman and Leolla Rodsybill.

THE BIG SCARE (Last Terry)

Moral: A man is known by the company he keeps.

= Originally ? (Likely THE END OF THE WORLD, MP 3034, 1924 – don’t have © synopsis)

After this, starting with THE FLY’S BRIDE, all the subsequent shorts appear to have been original for sound, with the singular 1932 exception of:

HAPPY POLO

(no moral in reissue)

= originally THE POLO MATCH, MP 206, 1929