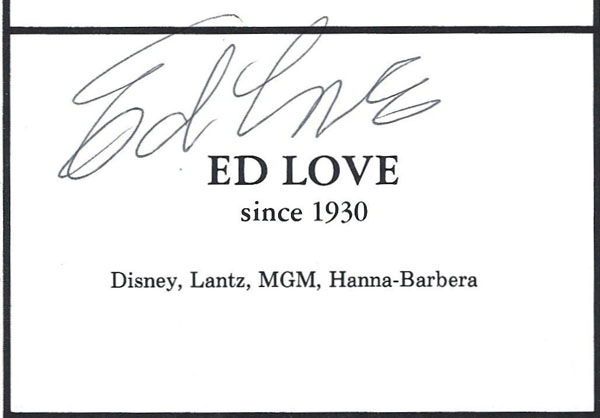

Edward H. Love was one of the most admired animators of cartoon shorts during Hollywood’s Golden Age, a reputation that continued on through his work in television at Hanna-Barbera. For instance, Michael Barrier points out he was one of Tex Avery’s “strongest animators” at MGM while John Kricfalusi greatly admires his work on The Flintsones and other H-B shows (check out his blog post on Love here). While my 1984 Golden Awards Banquet interview below is not really that informative, it does reflect his affection for his work and his son, animation producer-director Tony Love, for whom he both worked with and for.

Love started in animation in 1930 as an inbetweener at Disney, after he famously traded the use of his car for animation lessons. The lessons seemed to not only get him a job, it may have also had something to do with his being made an animator after only two months. Except for a stint with Ub Iwerks, he stayed at Disney through 1941, working on such films as Flowers and Trees (1932) and Lonesome Ghosts (1937), and apparently specializing in dance sequences; his one feature credit there was “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” section of Fantasia, which actually began as an extended Silly Symphony.

In an interview with Joe Adamson, Love claimed credit for inadvertently starting the “cleanup system” at Disney. Though the studio liked his animation, his lack of drawing skills hampered his ability to do his own cleanups. “So they took Marvin [Woodward] and told him, ‘You clean up that stuff of his.’ He cleaned up a couple of scenes and he got mad as hell. ‘What’s this getting me? I’m an animator.’ They didn’t know what to do. So they took Roy Williams who was very crude, and they made him my assistant. He was taking my drawings and cleaning them up. Now the others animators, said, ‘Jesus, there is this guy who has only been here a couple of months and he does not have to clean up his own drawings! If he can have one…’ And this started the assistants business. Until then the animators cleaned up their own drawings and all they left were in-betweens.”

In 1941, Love was one of the few animators to join the Disney strike, a decision he later said was “stupid.” In any case, he was one of the casualties of the large layoffs that followed the end of the walkout; the Screen Cartoonists Guild actually knew the layoffs were coming and it was one of the issues in the strike in terms of how they were to be done. (Incidentally, a Guild list of people on the picket line indicates Love was making $81.00 a week, though with bonuses his actual pay would have been more.)

Love then went over to MGM, where he joined Avery’s unit, becoming a key animator on such classics as Blitz Wolf (1942), Red Hot Riding Hood (1943), and Screwball Squirrel (1944). He left in 1947 and animated for Bob Clampett on his last theatrical cartoon, It’s a Grand Old Nag, a pilot film for Republic Pictures showcasing their Trucolor process. Love then briefly went to Walter Lantz, where he worked under Dick Lundy on cartoons like Playful Pelican (1948), starring Andy Panda. Then, like a number of colleagues at the time, he opened his own studio, Love, Hutton, & Love, with his son Tony and Bill Hutten, of which little seems known. However, Don Yowp noted that in 1957, E.H. Love Sales was “providing TV cartoons to Swift-Chaplin Productions.”

He then moved over to Hanna-Barbera, where he animated on many of the studio’s iconic shows, including the original incarnations of The Flintstones (1960) and The Jetsons (1962), as well as on various commercials. It was his work there that seemed to inspire a new generation of animation artists, including John K., who praised the stylized way he moved his characters.

For more on Ed Love, check out Denis Gifford’s obit for The Independent, which Don Yowp reprinted with additional information here. A list of Mike Kazalah’s Cartoon Research posts on commercials animated by Love is found here. For more detailed insight into Love’s work, there’s a volume 11 of Didier Ghez’s invaluable series, Walt’s People: Talking Disney with the Artists Who Knew Him (Xlibris, 2011), which includes a lecture Love did at CalArts in 1978, from which I took his tale of creating the assistants program at Disney.

Next week: Jack Kinney.

Harvey Deneroff is an independent film and animation historian based in Los Angeles specializing in labor history. The founder and past president of the Society for Animation Studies, he was also the first editor of Animation Magazine and AWN.com. Harvey also blogs at deneroff.com/blog.

Harvey Deneroff is an independent film and animation historian based in Los Angeles specializing in labor history. The founder and past president of the Society for Animation Studies, he was also the first editor of Animation Magazine and AWN.com. Harvey also blogs at deneroff.com/blog.

Just to put things in perspective, $81.00 per week works out to a yearly salary of about $68,000.00 adjusted for inflation.

During the 1970 and 1980’s Love, Hutton and Love was an office space in the Studio City area where animators could pick up free-lance animation work for Hanna-Barbera shows.

This was paid per foot of animation on each scene worked on. Unfortunately a non-union outfit.

Many CalArts animation students picked up work from them for extra cash during the school year or during summer breaks.

http://www.patcartoons.blogspot.com/

Also see Ed Love chatting on-camera in the 1988 Tex Avery documentary, along with fellow Avery/MGM guys Mike Lah and Heck Allen (plus Mark Kausler & Joe Adamson).

How’ve I never heard that comment before: “I went from Walt Lantz… to freelance.” As always, thanks for the interview and setting the context, Harvey.

It’s worth noting that the most successful features to come out of Love’s freelance studio was the Chucklewood Critters series and holiday specials.

Chucklewood Critters – ‘Twas The Day Before Christmas:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=_gZIhx7ob5s

Buttons & Rusty – A Chucklewood Easter:

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=p1YgurJNBl8

This channel has the entire series (albeit in a not-so-convenient format, which I apologize for in advance):

https://m.youtube.com/channel/UCLq6lXBEeQ9sFebM0J5_W_g

Ed Love lived two houses down from my (Tom Fennell’s) house in Sherman Oaks and I used to play with his son Tony who was a really great guy and was very successful in the industry as well. Mr Love had the most beautiful insect collection with possibly 12-14 large polished wooden display cases with scores of meticulousley labeled insects and butterflies. Stunning work. His multi tiered back yard was full of georgeous plants and flowers to attract the insects.