Though he stood over 6’ 6” tall, Claude D. Coats (aka “The Gentle Giant”) was never one of the most visible artists of Disney’s Golden Age; this was probably because he was not a director, animator or concept artist, but rather a background artist and color stylist of some repute, who spent the last part of his career at the Mouse House as an Imagineer.

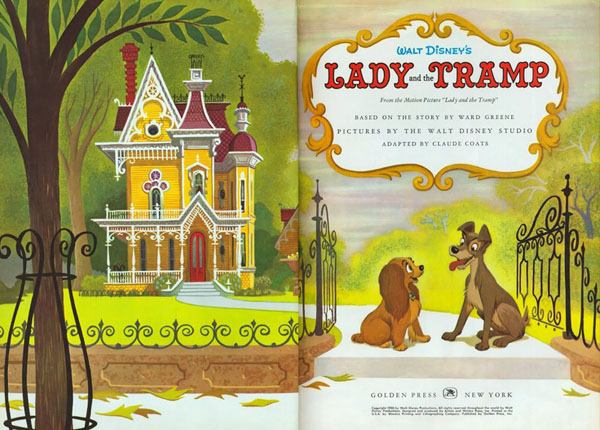

Born in San Francisco and raised in Los Angeles, he attended the University of Southern California on a track and field scholarship; he initially studied architecture but ended up with a B.A. in Fine Arts. Coats also studied watercolor painting at Chouinard and became a member of the California Water Color Society; fellow member Phil Dike suggested he apply for a job at Disney, who did hire him as an apprentice background painter in June 1935. His first assignments included Mickey’s Fire Brigade and Pluto’s Judgment Day. He subsequently worked on every Disney animated movie between Snow White and Lady and the Tramp, including Fantasia (the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” and “Pastoral Symphony” sequences), Dumbo, and The Three Caballeros.

Born in San Francisco and raised in Los Angeles, he attended the University of Southern California on a track and field scholarship; he initially studied architecture but ended up with a B.A. in Fine Arts. Coats also studied watercolor painting at Chouinard and became a member of the California Water Color Society; fellow member Phil Dike suggested he apply for a job at Disney, who did hire him as an apprentice background painter in June 1935. His first assignments included Mickey’s Fire Brigade and Pluto’s Judgment Day. He subsequently worked on every Disney animated movie between Snow White and Lady and the Tramp, including Fantasia (the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” and “Pastoral Symphony” sequences), Dumbo, and The Three Caballeros.

Coats also worked on such shorts as The Old Mill, Ferdinand the Bull and The Wind in the Willows. The Old Mill, which introduced Disney’s multiplane camera, was a key film for him, as it showcased the dramatic potential of scenic design. In his interview with Steve Hulett, he claimed it “was a good one for techniques and for the fact that the scenics were very strongly stressed, in that one particularly. Probably more so in proportion to animation than ever before. And I think it kind of opened the door for some scenes to be appreciated for just their scenic value, especially through Snow White, and that same idea went into Pinocchio too.”

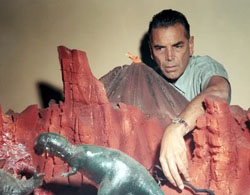

In 1955, Disney plucked Coats to join what was then WED Enterprises to work on Disneyland, which was then racing to completion. He recalled that, “I had a break in my background work where I wasn’t busy, so I got to do the model for the Mr. Toad attraction.” He subsequently worked as an art director and show designer for such attractions as Haunted Mansion, Pirates of the Caribbean and Alice in Wonderland. In addition to Disneyland, Coats also plied his skills at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom and EPCOT Center, Tokyo Disneyland and Disneyland Paris.

In his chat with Dan McLaughlin from the 1986 Golden Awards Banquet, Coats noted that this second career, though not filmmaking, was “still show biz,” in which he even occasionally used animation. He noted how they both careers actually “interweave. You find that a lot of the lessons we learned early on in story development and storyboards, quickie models, and things like that Walt taught us were, are still used. We still like to work that way, in a rough form, a rough storyboard, then refine it as [we] go along. … it lets you change things more quickly than if you get into a very precious model or huge painting and seem like you’re stuck with it.”

Claude Coats at Imagineering

There’s certainly no dearth of material out there on Coats, though one should probably start with the official ClaudeCoats.com site, which is maintained by his son Alan. Steve Hulett, son of Ralph Hulett, Coats’ colleague and friend, interviewed him for an article on Pinocchio, the transcript of which is posted on The Animation Guild’s blog here and here. Robin Allan’s interview for his book Walt Disney and Europe is published in Didier Ghez’s Walt’s People–Volume 6. For his theme park work, there is Jeff Kurti’s book, Walt Disney’s Imagineering Legends and the Genesis of the Disney Theme Park; for something online, there is “Claude Coats: The Art of Deception and the Deception of Art,” on the Long-Forgotten blog, which nominally focuses on Coats’ contributions to Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion and is (to say the least) heavily-illustrated.

Next week: Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas.

Harvey Deneroff is an independent film and animation historian based in Los Angeles specializing in labor history. The founder and past president of the Society for Animation Studies, he was also the first editor of Animation Magazine and AWN.com. Harvey also blogs at deneroff.com/blog.

Harvey Deneroff is an independent film and animation historian based in Los Angeles specializing in labor history. The founder and past president of the Society for Animation Studies, he was also the first editor of Animation Magazine and AWN.com. Harvey also blogs at deneroff.com/blog.

Yes! Some of the well known of the Nine Old Men for next week! Hooray!

“Some”? You mean THE most well-known of the Nine Old Men (that fabulous duo of The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation!)!

Very interesting post this week. My question is linked loosely with the topic here. I wondered how “story-boarding” for a live action movie differs for story-boarding for an animated cartoon. As far as I know, story boards for animated cartoons pretty much map out the gags and what they’re supposed to look like, but I’m also thinking that, in some cases, story-boarding was a tool in creating a live action film. Does that kind of story boarding cover the angles from which a scene is filmed, including quick cuts to this or that integral bit of action or focal point? Otherwise, backgrounds are as much an importance to a look of a cartoon as the characters moving at the forefront. In “stylized” animation of the 1960’s and beyond, I think it would look a bit awkward if the character is more detailed than the background, but then again, much can be said with nothing more than lights and shadows as representation of a background as with actual drawings of walls or doors. I wonder if Claude got involved with the way light show effects enhanced an exhibit at any of the theme parks. Those light effects can be amazing, in some cases making you feel as if you’re underwater.

Incredible career – Claude was my 3rd cousin

Claude is my grandfather! Thank you for sharing his love for his career at Disney. It never seemed like “work”. Although he’s been gone some 1991, I’m grateful for posts like this that bring him back. Can’t help but smile. Thanks!!