Suspended Animation #288

Previously I talked about The Disney Alice In Wonderland Never Made and promised that I would share the story about the Huxley version.

Aldous Huxley

The Disney Studio agreed to pay Huxley $7,500 to write the treatment for the film. They paid him $2,500 on October 18, 1945 with the balance to be paid on the delivery of the final treatment no later than January 15, 1946.

Huxley delivered his fourteen page treatment on November 23, 1945. The Disney Studio also took out an option for Huxley to do the final screenplay for $15,000 that would have included “all additions, changes and revisions.” The first draft of the script was delivered December 5, 1945.

Walt Disney had been seriously thinking of diversifying into live-action since World War II had shown him how vulnerable his business was. His solution was a film like Song of the South (1946) that featured a live action framework showcasing three animated segments. He also considered it for the film Treasure Island (1950) where pirate Long John Silver would tell Jim Hawkins three animated tales of Reynard the Fox to help him overcome challenges.

Here is a brief paraphrasing of Huxley’s synopsis for Alice and the Mysterious Mr. Carroll from November 1945.

The synopsis begins with a letter stating that the Queen wants to meet the author of Alice in Wonderland. She has been told he is an Oxford don and that she wishes the vice chancellor of the University, Langham, to discover his identity.

Lewis Carroll in 1863

Langham is not inclined to endorse Dodgson for the new job because he feels it is inappropriate for the good reverend to be interested in the theater and in photography. Langham’s assistant, Grove, who knows Dodgson quite well and just considers him a little eccentric tries to plead Dodgson’s case to no avail.

Grove is the weak-willed guardian of a little girl named Alice, whose parents are temporarily off in India. Grove has hired Miss Beale to take care of Alice. Miss Beale is a no-nonsense person who is very strict and dislikes Dodgson because he fills Alice’s mind with nonsense.

Dodgson has invited Alice to join him for a theatrical performance of Romeo and Juliet featuring one of his former students now grown up into an attractive and talented young actress, Ellen Terry. Miss Beale is outraged and orders Alice to write a letter to Dodgson informing him she can not attend because of her “religious principles”.

Mrs. Beale discovers that Alice has not posted the letter to Dodgson but hidden it so she could sneak out and attend the theater with him. Enraged, Beale locks Alice in the garden house.

Alice is terrified at being locked in the garden house and starts to imagine that a hanging rope is the caterpillar from the book and that a stuffed tiger’s head is the Cheshire Cat. Eventually, by remembering that in Wonderland there “is a garden at the bottom of every rabbit hole,” she finds a small shuttered window and is able to escape.

Alice is terrified at being locked in the garden house and starts to imagine that a hanging rope is the caterpillar from the book and that a stuffed tiger’s head is the Cheshire Cat. Eventually, by remembering that in Wonderland there “is a garden at the bottom of every rabbit hole,” she finds a small shuttered window and is able to escape.

Alice eventually finds her way to the theater and rushes tearfully to Ellen Terry and the surrounding performers who are taking a break on stage. She incoherently blurts out her tale. Terry sends for Dodgson and is indignant about the way Alice has been treated.

Ellen Terry eventually joined by the other actors, recounts the story of the Red Queen’s croquet game and the film transitions into animation. Dodgson arrives and joins in on the storytelling that transforms into another animated segment.

At the point in the animated story where the Red Queen yells “Off With Her Head!” it returns to live-action and the appearance of Miss Beale followed by Grove and two policemen. Grove is persuaded to dismiss the policemen and Terry eloquently convinces Beale of the need to be kinder to Alice.

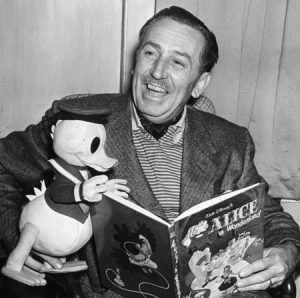

June 22nd 1951: Creator of Mickey Mouse Walt Disney (1901-1966) arrives in London to see the premiere of his latest film. He holds a model of his character Donald Duck whilst looking at a copy of the Walt Disney book of the new film ‘Alice In Wonderland’. (Photo by Edward G. Malindine/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

A disgusted and frustrated Grove proclaims that this is the final straw why Dodgson is unfit for the job of librarian and leaves to confront Langham with the news.

Langham has no time for Grove, because he has been informed that the Queen is arriving that very afternoon to meet the author of Alice in Wonderland and he fears what her reaction will be for his inability to find the author. Grove announces he can produce the author and returns to the theater.

Langham and the other dignitaries are paying their respects to the Queen and, just as Langham is about to admit he does not know who Carroll is, Grove arrives and shoves Dodgson forward. Alice is terrified the Queen will cut off his head, but the Queen is quite pleased. When she leaves, Dodgson finds himself lionized by those who had previously looked at him askance.

As all the new found flatterers cluster around Dodgson they all appear in Alice’s eyes to transform into the animated residents of Wonderland with only Dodgson himself remaining human. A brief epilogue shows a gothic doorway with the word “Librarian” painted on the door and Dodgson seated comfortably at a table, writing, and surrounded by walls of books.

There was a story meeting on December 7th, 1945 with Walt and Huxley as well as Dick Huemer, Joe Grant, D. Koch, Cap Palmer, Bill Cottrell, and Ham Luske.

(poster image via Matt Crandall)

For the final scene, Walt suggested, “Maybe in the last scene we see Mr. Carroll with all these little characters around him and all of a sudden he turns into the little character we want him to be. We can just make a tag ending. Everybody’s happy. Everybody can be happy while this is happening. It’s a natural place to bring everybody together.”

It has been stated that Walt rejected Huxley’s script because he felt it was too “literary” and he could only understand every third word. Reading Walt’s comments in the story meeting notes it is more likely that he just felt it didn’t capture what he wanted. However, Walt was actively excited about shaping the story into something workable.

Unfortunately, a massive fire in 1961 destroyed more than four thousand of Huxley’s annotated books and documents, including his involvement on the Alice project. Fortunately, the Disney Archives does have some of the story meeting notes, some memorandums, the fourteen page treatment and thirty-one pages of the script written by Huxley. When the Disney animated feature was released in 1951, it contained no elements from Huxley’s work.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

“Learn well your grammar,

And never stammer….

Drink tea, not coffee;

Never eat toffy.

Eat bread with butter.

Once more, don’t stutter.” — Lewis Carroll, “Rules and Regulations”

The myth that the dodo in “Alice in Wonderland” is somehow related to Dodgson stuttering his own surname is untrue. Dodgson, like most of his ten siblings, stuttered throughout his life; however, his stutter consisted not of repeating syllables, but of sudden, uncontrollable pauses where he was unable to speak at all. He called it his “hesitation” and was troubled by the effect it had on his clerical duties. According to biographer John Pudney (LEWIS CARROLL AND HIS WORLD, 1976), he never stuttered around children, only adults.

Such a speech impediment would not necessarily have been an obstacle to an academic career at Oxford. A generation later, a respected Oxford don named William Archibald Spooner lent his name to a habit of syllabic transposition, otherwise known as “spoonerism”. Spooner’s daughter, incidentally, married the art historian Campbell Dodgson, a cousin of Lewis Carroll.

Oxford University has a long connection with the dodo, having obtained one of the few stuffed specimens of the bird that reached Europe prior to its extinction in the 17th century. By the 1750s, that dodo was in such poor condition that the university ordered it destroyed, but one of the curators managed to salvage the head and one foot. Those remains are now the only soft tissue specimens of the dodo in existence. After the first scientific monograph on the dodo was published in 1848, the Oxford specimens took on greater significance; and this new scientific interest in the bird led to the discovery of large numbers of dodo bones in the Mare aux Songes on the island of Mauritius in the 1860s, just as Dodgson was writing his book. Finally, the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford contained not only those dodo specimens, but two fine 17th-century paintings of the dodo: one, a copy of a now-famous painting by the Dutch artist Roelandt Savery, who painted the dodo at least ten times (most likely using stuffed specimens as models); and another by Jan Savery, Roelandt’s nephew. Sir John Tenniel’s illustrations of the dodo were based largely on the original Roelandt Savery painting in the British Museum.

According to Errol Fuller’s DODO: FROM EXTINCTION TO ICON (2002), Dodgson used to take Alice Liddell to the Ashmolean Museum to see the dodo remains and the paintings. The dodo’s appearance in Wonderland would have arisen from their conversations during these excursions, and not from a manner of stuttering that, by all accounts, Dodgson did not possess.

In any case, by incorporating it into his story, Dodgson brought widespread attention to an extinct bird that was virtually unknown outside of academic circles. Had it not been for Alice, the dodo might be no better known today than the Steller’s sea cow, or the Tasmanian thylacine.

As for Huxley’s treatment, it sounds so mawkishly fictionalised that I think it would have done the books and their author a disservice. It’s unfortunate that the loss of Huxley’s papers has deprived us of the full script and other details of this remarkable story. But I’m glad that that film was never made, and that Disney instead gave the world the fully animated version we know and love today.

This is reminiscent of the early drafts for the 1939 “Wizard of Oz” which started out bearing almost no resemblance to the book and gradually grew closer to the original source material. It’s interesting that Disney would have considered Aldous Huxley as a writer, as his style is not like what one would expect from a Disney film.

Huxley’s treatment is more like a film for adults than a family-friendly undertaking. The undertones of sexual and religious immorality seem very unlike anything Disney had attempted up to that time.

Heretofore, I had only heard of the aborted Ginger Rogers version, which was apparently going to feature an adult woman (Ginger) as a live-action Alice in an animated world.

This is a fascinating glimpse into yet another forgotten piece of Disney history. Thanks very much!

Walt wanted Cary Grant to play Dodgson. Grant suggested Harold Lloyd.

You are always full of information I never knew. For decades I believed that the Dodo referenced Dodgson’s stuttering and I never knew all that material about the real dodo and Oxford and Dodgson’s connection to it all. Many thanks.

I might say the same of you, Jim. Many thanks!

I would still like to see the Huxley version someday. Thanks for the research on this, Sir James.

Paul Groh, thanks for your interesting comment. Perhaps Dodgson’s usage of the Dodo doesn’t specifically relate to his speech impediment, although in “The Annotated Alice” Martin Gardner writes “His stammer is said to have made him pronounce his name ‘Dodo-Dodgson’.” (Unhelpfully, Gardner does not offer any specific source for this.)

But the Dodo unquestionably is there to represent Dodgson. In Chapter 2 of “Alice”, Carroll/Dodgson writes: “It was high time to go, for the pool was getting quite crowded with the birds and animals that had fallen into it: there was a Duck and a Dodo, a Lory and an Eaglet, and several other curious creatures.” As Gardner points out, the animals named here correspond to the participants in a boating expedition Dodgson took in 1862: Reverend Robinson Duckworth (Duck), Lorina Liddell (Lory), Edith Liddell (Eaglet), and Alice Liddell (Alice, of course), which leaves Dodgson as the Dodo.

Indeed, when Dodgson presented a facsimile copy of “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” to Rev. Duckworth, he inscribed it “The Duck from the Dodo”.

It’s true that the Dodo is meant to represent Dodgson, and it’s also true that Dodgson spoke with a stammer of sorts. But somewhere along the line, somebody made a false inference connecting those two facts, giving rise to one of the many myths surrounding Wonderland and its creator.

Dodgson’s “hesitation”, as he called it, is amply documented by numerous witnesses, for example his young friend May Barber (Mrs. H. T. Stretton), who reminisced in 1958 (quoted in Morton N. Cohen, LEWIS CARROLL: A BIOGRAPHY, 1995, p. 290): “Those stammering bouts were rather terrifying. It wasn’t exactly a stammer, because there was no noise, he just opened his mouth. But there was a wait, a very nervous wait from everybody’s point of view: it was very curious. He didn’t always have it, but sometimes he did. When he was in the middle of telling a story he’d suddenly stop and you wondered if you’d done anything wrong. Then you looked at him and you knew that you hadn’t, it was all right. You got used to it after a bit. He fought it wonderfully.”

It’s worth noting that in the book, the Dodo does not stammer but, like Dodgson, hesitates before speaking: “This question the Dodo could not answer without a great deal of thought, and it sat for a long time with one finger pressed upon its forehead (the position in which you usually see Shakespeare, in the pictures of him), while the rest waited in silence. At last the Dodo said….”

Great quote. It must be much worse to have such a “hesitation” than a stutter, I would think.

Very perceptive analysis of the text, too! I think you’re right. But I wonder what picture(s) of Shakespeare Carroll was referring to here? A quick Google search doesn’t reveal anything like the pose described.

Is there a way to see the 24-page treatment?

Maybe this is the image? Shakespeare pressing fingers to the side of his head:

https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/illustration/william-shakespeare-royalty-free-illustration/163674000

Bingo! Glad I saw this, even a year later!