Certainly, the Walt Disney Company has been the target for many charges of plagiarism and with the many musical experts who contribute to this site, I am hoping they may provide some greater insight into this story.

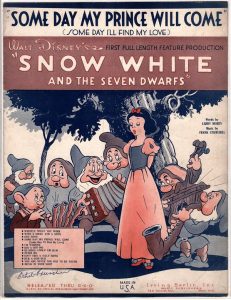

Some Day My Prince Will Come had lyrics by Larry Morey with music by Frank Churchill and was written for Disney’s legendary first animated feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

The concept for Some Day My Prince Will Come first appeared in a story conference on August 1934. It was originally going to be part of a dream sequence of Snow White and the Prince dancing in the clouds surrounded by animated stars doing antics similar to the Silly Symphonies series.

Thornton Allen, owner of the copyright to the song Old Eli claimed that Churchill lifted the chorus of that song and used it in Some Day My Prince Will Come. “Old Eli” was slang to refer to Yale University that was named after its first major benefactor, Elihu Yale. Allen further claimed nine musical similarities between the two works:

“Old Eli March” was written by Wadsworth Doster in 1909, while he was a student at Yale University. Doster never copyrighted the song himself, but assigned all his rights, title and interest in it, including the right to copyright the same, to Allen and his music publishing company.

Thornton Allen included Old Eli in a volume of musical compositions titled Intercollegiate Song Book, Eastern Edition, which was published and put out to the public for sale on October 6, 1936. The copyright registration was September 26, 1936. You can hear a recording of the music here:

Allen claimed that on November 25, 1932, he had sent a copy of the song to the Disney Studios in addition to orchestra leaders and others in an attempt to get them interested in the song.

In his final decision, New York District Judge Conger wrote:

“It may be that he did send this copy to Disney when he says he did. On the other hand, Mr. Allen had no record of any kind, either to refresh his recollection or to substantiate his statement. He did have from the Disney Studio an acknowledgment of his letter of November 26, 1932.

“Mr. Allen was unable to produce a copy of his letter, but the respondents eventually produced the original from the Hollywood office of the Disney Studio, and it there appeared that the letter was directed to the Disney New York office, and not to the Hollywood office. It further appeared that there was enclosed in the letter a list of musical compositions which Mr. Allen was sending to Disney.

“Mr. Allen was unable to produce a copy of his letter, but the respondents eventually produced the original from the Hollywood office of the Disney Studio, and it there appeared that the letter was directed to the Disney New York office, and not to the Hollywood office. It further appeared that there was enclosed in the letter a list of musical compositions which Mr. Allen was sending to Disney.

“The composition Old Eli was not specifically mentioned, but Mr. Allen claimed it was among those designated at the end of the list as ‘etc., etc.’ After all, the proof on this point is supported only by Mr. Allen’s recollection after these many years.

“Taking for granted, however, that he did send this copy of Old Eli to Disney in 1932, there is no proof that Mr. Churchill ever saw it. He has testified that he did not. It was not sent to him direct.

“If it was retained by Disney, it undoubtedly would have been in their library. Mr. Churchill testified that he used the library very little. That he composed by thinking of a tune in his mind, and then writing it down on a piece of paper. Weighing all the probabilities, I have come to the conclusion that the evidence is not sufficiently strong for me to hold that Churchill actually did see and have in possession, prior to or at the time he wrote his composition, a copy of Old Eli.”

According to the court testimony, Some Day My Prince Will Come was written by Frank Churchill, on or about November 1934, in connection with the movie production Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. The copyright on his song was obtained on January 25th, 1935, as an unpublished work, and requests for copyrights as a published work were made on December 14th, 1937. Some Day My Prince Will Come was published when the motion picture Snow White was first shown, which was around Christmas 1937.

The Disney Studios hired composer and music commentator Deems Taylor to testify on its behalf as an expert witness. Taylor appeared in Disney’s Fantasia (1940) and although his name is pretty much forgotten by modern audiences, he was quite popular and well known as a promoter of classical music including being an intermission commentator on radio for the New York Philharmonic. He served six years as president of ASCAP. Taylor was also a composer including orchestral works and operas and authored several books.

Since the main contention was the similarity of the notes in the first eight bars, Taylor testified that there was indeed a similarity in the first eight bars of each but with one significant difference. He discounted the importance of any minor similarity: “It is a very common harmonic progression. You find the elements of it in the exercises in harmony books.”

Since the main contention was the similarity of the notes in the first eight bars, Taylor testified that there was indeed a similarity in the first eight bars of each but with one significant difference. He discounted the importance of any minor similarity: “It is a very common harmonic progression. You find the elements of it in the exercises in harmony books.”

Later, when he dissected the measures, he made an analysis of the harmonies and found many substantial differences which he illustrated by charts and by use of the piano.

Allen’s primary claim was that out of a total of 30 notes in Old Eli, 27 are identical in Some Day My Prince Will Come.

Musical experts for Disney agreed that there was a similarity in the first four measures of each song, but that the rhythmic structure of each was entirely dissimilar, that the choruses in their entirety were substantially different; that the similarity would not impress someone as being any more similar than a number of other melodies that one might hear; that all popular music that is held down to a formula, more or less, is apt to be similar to other popular music that has been written at one time or another; that while the first eight bars were similar, there were more differences than similarities.

In addition to the Disney Studios, RKO Radio Pictures (that distributed the film) and Irving Berlin Inc. (because it published the song) were also respondents in the suit.

Judge Conger finally decided that he had “come to the conclusion that as far as this testimony is concerned, complainant has failed to convince the Court that the writer of the song Some Day My Prince Will Come copied the composition Old Eli to such an extent that it constituted piracy or plagiarism. In coming to this conclusion I have also used my own musical sense, such as it is, and I have arrived at the result that while there are similarities between the two compositions, there are a great many differences. I have heard the compositions played, and to my ear there is a similarity, but not such a similarity as would impress one. In other words, I would not take the one for the other.”

Judge Conger finally decided that he had “come to the conclusion that as far as this testimony is concerned, complainant has failed to convince the Court that the writer of the song Some Day My Prince Will Come copied the composition Old Eli to such an extent that it constituted piracy or plagiarism. In coming to this conclusion I have also used my own musical sense, such as it is, and I have arrived at the result that while there are similarities between the two compositions, there are a great many differences. I have heard the compositions played, and to my ear there is a similarity, but not such a similarity as would impress one. In other words, I would not take the one for the other.”

Conger also took in to account the reputation and works of the accused composer: “Mr. Churchill was a professional writer of undoubted ability. He composed music directly on paper and not by playing a piano. He apparently had real talent for composing. He had composed a great deal of music prior to this song, while working for Disney. He was given the words for Some Day My Prince Will Come and was told that a romantic melody was wanted in connection with it. The words or lyrics required the musical setting to be in waltz time.”

Conger also emphasized that there was no evidence that Churchill had direct access to Old Eli. Conger stated: “He denies that he ever heard it, and the evidence does not tend to contradict him.”

“…and they lived Happily Ever After”.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Years ago an attorney tried to engage me as a consultant in a breach of copyright lawsuit. His client claimed that his former record label had stolen one of his songs and released it with another artist. The attorney wanted me to write out the melody lines to both songs, one on top of the other, and indicate points of congruence between them. After listening to both songs, it was obvious to me that, although the two songs had similar titles, they were musically unrelated. When I pointed this out to the attorney, he asked me to write the music out anyway because — even though he admittedly had a tin ear and couldn’t read music — he was confident enough in his persuasive powers to make his case in court. At this point I refused to have anything further to do with him.

If I had been asked to do this in the case of Allen v. Disney, however, I’d have taken the job. As the plaintiff pointed out, there are numerous points of similarity between the two melodies in the first eight bars. But I don’t think that’s enough to prove breach of copyright, and it certainly strains credulity to consider that, when Churchill was asked to compose a yearning love song for Snow White, the first thing that popped into his mind was a college marching song. By all accounts Churchill’s success at Disney was based on his ability to come up with catchy tunes, of appropriate mood and character, right on the spot. I think justice prevailed in this case

I’ve long been fascinated by the techniques used by song parodists who need to come up with a melody that is recognisably similar to a copyrighted song, but not so similar as to make them legally liable. Steve and Julie Bernstein, who composed song parodies for “Animaniacs” and other cartoons, often simply invert it — having the tune rise where the original falls, and vice versa — while keeping the original rhythm and harmony. This is a legitimate compositional technique going back to the Renaissance, and legally it lets them off the hook, though I’m sure the attorneys for Michael Jackson and Andrew Lloyd Webber must have grumbled about it.

Unfortunately most breach of copyright suits are argued and decided people who have no knowledge of or appreciation for musical composition, and the case boils down to which side has the best legal representation. “The man that hath no music in himself, nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds,” wrote Shakespeare in Act V of The Merchant of Venice, “is fit for treasons, stratagems, and spoils.” In other words, tort law.

I had to laugh at your observation that Deems Taylor was better known in his own time than he is today. I have an old biographical dictionary of composers from 1940 in which the entry for Deems Taylor is over twice as long as the one for Tchaikovsky on the very next page. Who wrote the book? You guessed it: Deems Taylor!

Ridiculous lawsuit. Not until 1:06 in the above recording does anything resembling “Someday…” occur. Even if there was solid proof Churchill had listened to “Old Eli” immediately before writing his song, you couldn’t make a credible plagiarism case.

As a former member of the Yale Marching Band, during my time there I never played, much less heard of, “Old Eli March.” I wonder if it was somehow “tainted” by the lawsuit and dropped from the band’s repertoire afterward.

Similar, but I don’t think there’s enough to prove plagiarism, but what do I know.

I think I can say without fear of contradiction that Ed Norton is not the composer of “Swanee River.”

Except for two four-bar sequences with similar notes, I hear no resemblance between the two songs. The march is in 4/4 time, and “Prince” is in 3/4 time! But as long as money is at stake, these kinds of musical battles will take place. Reminds me of the fight between Allen Klein (manager of The Rolling Stones) and the band The Verve, over “Bittersweet Symphony.”

Interesting how the primary lines don’t rhyme. But it’s one of the loveliest, most deceptively simple songs ever written for a movie, or ever written. “Over the Rainbow” lyricist E.Y. “Yip” Harburg dismissed the “Snow White” songs as “jingles” that wouldn’t hold up symphonically. He was wrong.

It is impossible to write a song that won’t be very similar to something else, something older. Even 5 minutes older.

Browsing through back issues of Billboard magazine, I was surprised at how regularly this kind of lawsuit turned up in its pages. Seems like it was almost impossible for a published song to become a hit without somebody, somewhere, claiming it was stolen from a tune they wrote. It’s worth noting, though, that these lawsuits almost always failed, though there were exceptions. For example, Mack David, composer of numerous songs, including some for Disney, successfully sued Jerry Herman over Herman’s “Hello, Dolly!” because the first four bars of “Hello, Dolly!” are identical to those in the refrain of “Sunflower,” a pop song David had published in 1948.

Weird. Haven’t seen SW in a long time. Now I’ll be confused by it when I hear that song!

I don’t get it. it seems like this was a meritless copyright lawsuit that got defeated in court a long time ago, without making a compelling case or having any cultural impact. What was the point of this article?

I thought it was interesting. In fact, I’d like to read about other spurious lawsuits that may have been filed against Disney over the years. I’ll bet some of them were pretty hilarious.

I always tell myself never to read the comments here, ’cause they contain some of the worst takes imaginable. And yet, time and time again, I let myself down. And yup, sure as rain. A terrible take.