Suspended Animation #277

Readers of this column know that I have a great fascination for animated films that were never made and why. I also love examining the process that kept changing a story approach until the final film.

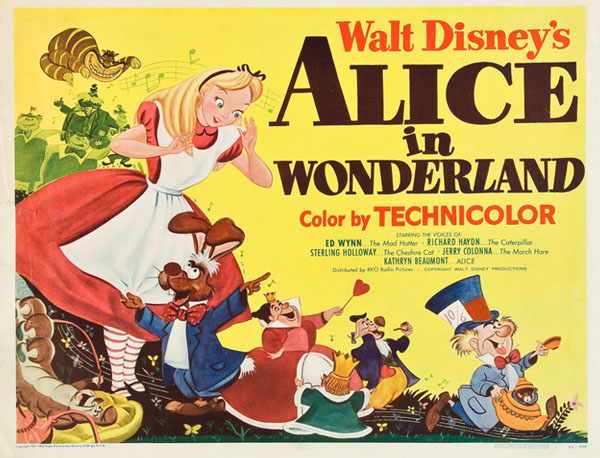

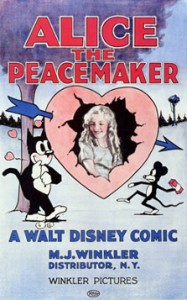

Prompted by the success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Walt purchased several projects for future animated features, including the rights to Alice in Wonderland in 1938 — in particular the rights to reproduce the original Tenniel drawings.

Walt told the New York Times Magazine (March 1938), “Alice in Wonderland should never have been done in the realistic medium of motion picture [referring to the 1933 Paramount film] but we regard it as a natural for our medium.”

Between December 1938 and April 1941, Walt held at least eleven documented meetings with various members of his staff to discuss the possibilities of making Alice in Wonderland.

“I’ll tell you what has been wrong with every one of these productions on Carroll,” said Walt Disney at a January 4th, 1939 story meeting. “They have depended on his dialogue to be funny. But if you can use some of Carroll’s phrases that are funny, use them. If they aren’t funny, throw them out. There is a spirit behind Carroll’s story. It’s fantasy, imagination, screwball logic…but it must be funny.

“I mean funny to an American audience. To hell with the English audiences or the people who love Carroll…I’d like to make it more or less a 1940 or 1945 version—right up to date. I wouldn’t put in any modern slang that wouldn’t fit, but the stuff can be modernized.

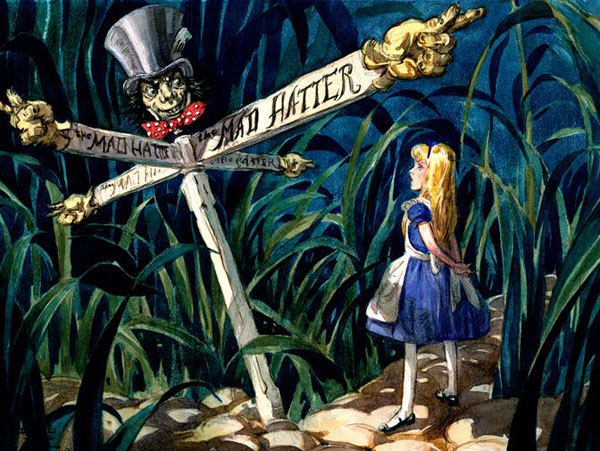

Alice by John Tenniel

Disney storyman Al Perkins researched Carroll and his work and produced a 161 page analysis of the book Alice in Wonderland that broke down the book chapter by chapter, pointing out the possibilities for animation.

Some of these suggestions were later used in the final animated feature, including the idea that the White Rabbit should wear glasses because Carroll once commented that he thought the White Rabbit should have spectacles, even though Tenniel never drew the character that way.

Perkins also felt that the Cheshire Cat should be expanded and appear in other scenes of the story and that the watch that the Mad Hatter and the March Hare fix should belong to the White Rabbit.

Beginning June 1939, British artist David Hall spent about three months to produce roughly four hundred paintings, drawings and sketches using the Perkins’ analysis as a guide. Hall had a background as a production artist in the film industry including DeMille’s The King of Kings (1927).

Story conferences at the time were not helpful to Hall because Walt felt that his story people didn’t understand the spirit of the story. For instance, they had suggested changing the croquet match into a football game. According to the story conference notes, Walt considered this approach at humor as “Donald Duck gags” and that “I think the book is funnier than the way you guys have got it. Get in and study characters and personalities, and that’s where the real humor will come from.”

A David Hall concept painting for Disney’s “Alice In Wonderland”

In November 1939, the Disney Studio filmed a Leica reel (a film of the concept drawings with a soundtrack to get an idea about the continuity and flow) using Hall’s artwork. The soundtrack included Cliff “Jiminy Cricket” Edwards doing the voice of the Talking Bottle (later changed in the final film to a talking doorknob).

“There are certain things in there that I like very much and there are other things in there that I think we ought to tear right out. I don’t think there would be any harm in letting this thing sit for a while. Everyone is stale now. You’ll look at it again and maybe have another idea on it. That’s the way it works for me. I still feel that we can stick close to Alice in Wonderland and make it look like it and feel like it, you know,” said Walt after viewing the reel that over the decades seems to have disappeared. David Hall left the Disney Studio January 1940.

Gloria Jean

“There’s a lot of story here with the girl, and trying to carry the story with a cartoon girl puts us in a hell of a spot. We might, in the whole picture, have, say a dozen complicated trick shots, but the rest of them would be close-ups and working around it. We can get some good characters and good music. There’s so much stuff in this business, we could work around the girl.”

At the meeting, it was suggested that actress Gloria Jean, who was 14 at the time and had just appeared as W.C. Fields’ niece in the film Never Give a Sucker An Even Break, should be considered as a live-action Alice.

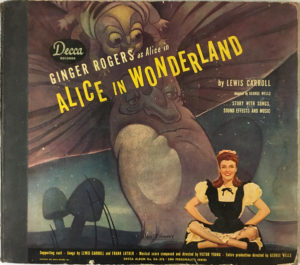

The outbreak of World War II prevented further work on that project. In 1944, the Disney Studios provided the cover artwork of a massive mushroom and the famous caterpillar for a record album based on Alice in Wonderland read by actress Ginger Rogers, who was 33 years old at the time.

The outbreak of World War II prevented further work on that project. In 1944, the Disney Studios provided the cover artwork of a massive mushroom and the famous caterpillar for a record album based on Alice in Wonderland read by actress Ginger Rogers, who was 33 years old at the time.

The album featured original music composed by Frank Luther and conducted by Victor Young. Initially on a set of three 78rpm records on the Decca label, catalogue number 5040 in 1944, it was re-released in 1950 in 7-inch 45 rpm format and as a 10-inch LP.

Besides Rogers, voices on the album included Lou Merrill, Bea Benaderet, Arthur Q. Bryan, Joe Kearns, Ferdy Munier and Martha Wentworth. Learn more about (and hear) this record album in Greg Ehrbar’s Animation Spin post here. Supposedly, Walt briefly flirted with the idea of doing the live-action/animated version of Alice with Rogers in the lead. However, he later decided he might use Luana Patten who he liked in Song of the South.

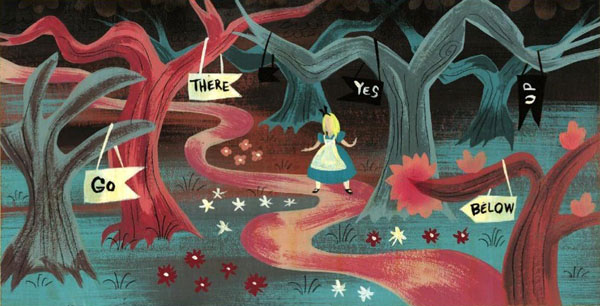

Mary Blair concept art

Coming up in a couple of weeks, I’ll tell you about what happened when Walt brought in author Aldous Huxley to write a live action screenplay for Alice in Wonderland with animation segments (like in Song of the South).

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Jim Korkis is an internationally respected animation historian who in recent years has devoted his attention to the many worlds of Disney. He was a columnist for a variety of animation magazines. With his former writing partner, John Cawley, he authored several animation related books including The Encyclopedia of Cartoon Superstars, How to Create Animation, Cartoon Confidential and Get Animated’s Animation Art Buyer’s Guide. He taught animation classes at the Disney Institute in Florida as well as instructing classes on acting and animation history for Disney Feature Animation: Florida.

Conventional wisdom says that if a film under-performs at the box office and is not a hit with critics, it means the film itself is not very good. Disney’s version of “Alice in Wonderland” has been criticized heavily, both in its departures from the original Lewis Carroll work and in its adherence to the original–because it follows the essential plot and structure (built on fantasy and dream) of the story, but also gives the story the Disney treatment. Walt himself later criticized the film, bowing to the judgment of audiences and critics. This seems to me an unfair assessment.

Taken on its own terms for what it is–a Disney-fied retelling of the classic book–it is certainly not a low point for Disney animation. On the contrary, there are touches of absurdity, visual and verbal, that at least equal or possibly even outshine anything Lewis Carroll wrote. The Tulgey Wood sequence is an excellent example. While virtually nothing in the sequence reflects actual material from either of the Alice books–save for the Tulgey Wood name which is derived from the poem “Jabberwocky” (and the name of the Mome Raths from the same source)–yet the animated auto horns and the umbrella birds, plus the numerous other visually startling creatures inhabiting that section of Wonderland, are if anything true to the spirit of the original yet in a modern way, which Walt was trying to achieve as referenced above.

The timing of the sequence is also impeccable–as the nonsense which Alice ordered in the first scene ramps up and becomes completely absurd and irrational, Alice, whose intolerance has been mounting almost from the moment she fell down the rabbit hole, finally reaches the point where she has had enough. This spurs the song “Very Good Advice” in which she breaks down in tears. In turn, at this juncture the bizarre creatures fade away and disappear. And instead of Cinderella’s fairy godmother appearing at this low ebb, her by now old friend the Cheshire Cat comes to the rescue and provides access to the Queen’s croquet grounds (and ultimately to the passage out, although there are still two major sequences to come before this occurs). Though not as kindly intentioned as a fairy godmother, the Cheshire Cat serves as a guide of sorts, employing mischief rather than magic to push events along to the inevitable conclusion of Alice’s wakening.

It is truly a shame that “Alice” did not receive more recognition in its day. But the film DID inspire not one but two attractions at Disneyland which are still highly popular today. And its reputation was resuscitated somewhat by its popularity among college students in the 1970’s. It is in fact now listed as one of the top-selling movies of its year. Not a bad track record for a film that was under-appreciated upon its first release.

Extremely well said. I 100% agree.

Lewis Carroll’s Alice books are my favorite literary fiction of all time. Yes, the Disney movie veers substantially from the text quite often, but it’s remarkably faithful to the spirit of the books. While I can’t argue that it’s one of Disney’s best, on its own terms it’s a fine film, with some truly memorable visuals and great vocal performances. As great a career as Sterling Holloway had, I think his Cheshire Cat might be my favorite of his characters.

It absolutely is one of Disney’s best. It is a bonafide classic.

People should really ignore most of the contemporary negative criticism of the Walt Disney era because it’s so obvious that most of the unfair criticisms came from intellectually dishonest left-wing “so-called” critics who were biased against Walt because of his support for the HUAC and the testimonies that he gave.

One such in particular was Bosley Crowther who had the following to say about Sleeping Beauty: “the princess looks so much like Snow White they could be a couple of Miss Rheingolds separated by three or four years. And she has the same magical rapport with the little creatures of the woods. The witch is the same slant-eyed Circe who worked her evil on Snow White. And the three good fairies could be maiden sisters of the misogynistic seven dwarfs.”

I mean this is completely and utterly tone-deaf in so many ways that one may wonder how people like this got jobs in the first place. After all, one has to be blind as to ever confuse Princess Aurora for Snow White.

Oh wait, I know, they were hired to propagandize.

The most fair reviews of the day you could find pertaining Walt Disney pictures would be Harrison’s Reports which was an independent publication. The rest you can take with a grain of salt , because most of them were either biased against Walt or were pompous.

I can’t help but pity Disney’s story men. First Walt tells them he wants a version of “Alice in Wonderland” that isn’t too British, that Americans — specifically those in the “Podunks” of the country — will find funny. Then, when they try to give him exactly that, Walt accuses them of making “Donald Duck gags” and tells them to stick close to the source material. It must have been a terribly frustrating experience for them.

If Gloria Jean had been cast as Alice, they’d have had to give her more songs. She had a beautiful voice. But I’m happy that they decided on an animated Alice, with Kathryn Beaumont providing the voice and live-action reference. “Alice in Wonderland” isn’t one of my top favourite Disney features, but I think Alice herself is one of the most appealing female characters in any of them.

Alice In Wonderland (1951) remains my favorite full length animated feature.

While it does not have the best ever animation (character of effects), it is the one title that I would be unable to edit a second

(and many have tried).

In addition to the 1951 Disney version, I have seen the 1933 live action, 1950 Bunin, 1966 British TV, 1972 musical, 1985 Irwin Allen, 1999 TV movie, 2010 Burton versions (as well as the 1975 Kristine De Bell and 1966 Hanna Barbera versions).

Character’s dialogue in the original book is designed to be read, and does not transform well to the spoken word (which I find apparent in many of the above adaptions).

However it is the eclectic group of wonderful characters that make the story appear to be so desirable to film makers.

So the best way to film appears to be to try and handle the characters with reverence, but with a degree of flexibility –

which does not include replacing the croquet match with a football match. That would be a travesty akin to the inclusion of the non English animal Gopher in Winnie The Pooh And The Honey Tree (1966).

I agree with Disney that animation works best with the material, in preference to animal costumes or CGI hybrids.

Live action people in an animated world works well for short sequences (Bedknobs And Broomsticks, Mary Poppins etc).

But for longer sequences of 20 minutes the differences of live action vs animation can become jarring, or seem to appear not quite right. This to me was the major defect of Hanna Barbera’s New Adventures Of Huckleberry Finn TV Series

David Hall’s art seems closer in style to the 2010 version – both of which makes Wonderland a dark and nightmarish place.

Not the sort of place I would desire to visit.

The card table green of Mary Blair, shadows and quirkiness enable Wonderland to tread between the beauty of the flower garden, and the lead up to the song Very Good Advice where the umbrella birds transform from comical to ominous, then to caring during the song.

And Alice’s entrance via the Cheshire Cat to the March Of The Cards (as for me I prefer the short cut) is straight out of the modus operandi of a dream.

Like Cinderella, there will be many more film versions of Alice In Wonderland in the future.

The imagination of Production Designers will interpret Wonderland in many different ways –

And the screenwriters will continue to be baffled regarding the execution of the material.

My own take is that no adaptation I’ve seen pays serious attention to the logic underlying all the madness, beyond a few throwaway lines. In Carroll that’s what keeps the whole thing from collapsing into random non-sequiturs. I for one keep waiting for Alice to either master it by playing the game or conquer it with real-world common sense.

The 1933 tries meekly here and there, but ultimately it’s a near-horrorshow where you wonder if the named celebrities really are under those scary masks. The Burton version goes for pure imagery, and ultimately plays out as a lavish video game that happens to use Carroll’s character names.

Disney makes a feint towards a story by having Alice idly wishing for a world of nonsense, getting it, and sort-of regretting it. But most of the time she’s a straight woman to whoever’s there, reacting sensibly and getting annoyed but little more. She’s not desperately trying to get home, like Dorothy. She’s not chasing a goal, fighting an enemy, or struggling to survive. She’s not making an effort to understand this place, which might have provided a narrative drive. She’s just a moderately engaged tourist, following paths that look picturesque and being inconvenienced here and there. Yes, you can say the same of the literary Alice. But a movie generally demands more than passive observation.

The trial at the end is the perfect occasion to her to embrace or defeat Wonderland’s rules, but it’s just more madness and the wake-up ending. It’s certainly a fun movie, attractive and entertaining, but it’s not a story that gets anywhere.

Did we watch the same movie?

Disney’s Alice ABSOLUTELY is trying to understand the place, hence the whole sequence with the Queen of Hearts where Alice protests to her nonsensical “rules” and doesn’t cater to her whims. Hence the whole Unbirthday scene where she questions the Mad Hatter and the March Hare how somebody could celebrate an “Unbirthday”. The scene with the Smoking Caterpillar and so on and so forth.

The movie perfectly captures the uncontrollable pacing of being in a dream that is found in the original books. That is what makes the whole film so engaging in the first place. It captures the feeling of a strange dream where the dream is constantly changing without you even realizing it and it does so in brilliant fashion.

No she doesn’t “sort-of regret” it. For most of the movies she’s swept by the absurdities of the Wonderland, she enjoys and even embraces it to some degree. It’s only near the end where it becomes too much for her and she gets lost that she breaks down and cries yearning to return home.

By sheer coincidence (and because the film celebrates the anniversary of its first release next Tuesday), I’m doing an Animation Spin about Disneyland Records’ Alice in Wonderland story records. A lot of what I have been preparing to write, also by coincidence, is wonderfully close to what has been in this comment section in favor of the film. Like Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, Walt’s 1951 Alice has gained a momentum no other version ever did without adding in an extraneous storyline. Carroll created a free-flowing non-narrative that defies translation into narrative media and no one translated it better than the Disney staff, even though they didn’t know it at the time. Plus the score (which took on a life of its own) resulted in Tutti Camarata and Darlene Gillespie recording The Greatest Album Ever Made. 🙂

To Jim and the rest of you commenting — Callooh! Callay!

It’s a shame the Lou Bunin version of ALICE was blocked as it really offered no competition to the Disney film. I had the 16mm one reel version in black and white for decades. Then I found the film on DVD in color (not so great color).

I used to rent ALICE from Disney, Toronto in 16mm in the 1970s until they withdrew it because folks were getting stoned to watch it. Loved it then, still love it. It was the first animated film I saw as a kid. The mad queen shouting, “Off with her head!” scared me silly. Full throttle murder all the way.

Neat post.

I’m sure folks in Podunk who read ALICE IN WONDERLAND enjoy it as much as folks do in New York.

Alice in Wonderland continues to be the Disney feature I watch the most. I don’t mind the episodic nature of the film as all the episodes are so much fun. Snow White and Cinderella are very dark compared to this with both lead characters suffering abuse. Sleeping Beauty is asleep for most of the film she stars in. Alice has none of those issues and for the early classics with female leads, this is the one I prefer to watch.

While it’s true that Aurora is asleep for most of the feature, the scenes with her are nonetheless a delight to watch.

There are still the characters of Flora, Fauna, Maryweather, Prince Philip and last but certainly not least the antagonist of the film Maleficent who carry the film.

Sleeping Beauty is easily one of the most rewatchable films Disney ever produced.

As for Snow White and Cinderella being darker than Alice, eh… I wouldn’t say so. It’s true that the Queen wants to kill Snow White and that Cinderella is mistreated on her own home by her stepmother and her stepsisters, but, I’d argue Alice is darker than them in a much more subtle way(and in fact I never really thought of Cinderella as an especially dark film beyond obviously sympathizing with her situation). Alice is like a dream gradually turning into your worst nightmare, and that is very relatable for most people out there.

The scene where Alice gets lost in the woods near the climax of the film and asks to return home and breaks down crying is quite dark, it especially resonated with me because I know how it feels to be lost when you’re a child.

While Snow White features a similar scene where Snow White runs away and gets lost in the woods, it’s in no way comparable to the climax scene in Alice where it gradually culminates into Alice getting lost and her realizing her mistakes and yearning to go back home.

The feeling of getting trapped in an unfamiliar location is far darker imo. Especially when you consider that that same unfamiliar location just moments ago, to your eyes, appeared to be a nice place where you can escape to. The whole monkey’s paw “Be careful what you wish for” motif of the film combined with the dream wonderland setting touches much more on the human psyche than the straightforward “Good vs Evil” narratives of Snow White and Cinderella, because on Alice… Alice herself is the cause of her own undoing.

Following that scene, we have the scene where Alice finally wakes up and is relieved to find out that it was just a dream which is relatable to any person out there. This feeling is something that Snow White or Cinderella with their “Happily Ever After” endings where the Prince and the Princess end up with each-other can never capture.

As such Alice is simultaneously one of the strangest, darkest, most unnerving and one of the most rewarding and soothing Disney films, because due to the nature of the source material it touches on a lot of universally relatable human concepts which most other Disney films don’t.